Federal Disaster Assistance After Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, Wilma, Gustav, and Ike

This report provides information on federal financial assistance provided to the Gulf States after major disasters were declared in Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas in response to the widespread destruction that resulted from Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma in 2005 and Hurricanes Gustav and Ike in 2008.

Though the storms happened over a decade ago, Congress has remained interested in the types and amounts of federal assistance that were provided to the Gulf Coast for several reasons. This includes how the money has been spent, what resources have been provided to the region, and whether the money has reached the intended people and entities. The financial information is also useful for congressional oversight of the federal programs provided in response to the storms. It gives Congress a general idea of the federal assets that are needed and can be brought to bear when catastrophic disasters take place in the United States. Finally, the financial information from the storms can help frame the congressional debate concerning federal assistance for current and future disasters.

The financial information for the 2005 and 2008 Gulf Coast storms is provided in two sections of this report:

Table 1 of Section I summarizes disaster assistance supplemental appropriations enacted into public law primarily for the needs associated with the five hurricanes, with the information categorized by federal department and agency; and

Section II contains information on the federal assistance provided to the five Gulf Coast states through the most significant federal programs, or categories of programs.

The financial findings in this report include the following:

Congress has appropriated roughly $121.7 billion in hurricane relief for the 2005 and 2008 hurricanes in 10 supplemental appropriations statutes.

The appropriated funds have been distributed among 11 departments, 3 independent agencies/entities, numerous subentities, and the federal judiciary.

Congress appropriated almost half of the funds ($53.8 billion, or 44% of the total) to the Department of Homeland Security, most of which went to the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

Congress targeted roughly 22% of the total appropriations (almost $27 billion) to the Department of Housing and Urban Development for community development and housing programs.

Approximately 20% ($25 billion) was appropriated to Department of Defense entities: $15.6 billion for civil construction and engineering activities undertaken by the Army Corps of Engineers and $9.2 billion for military personnel, operations, and construction costs.

FEMA has reported that roughly $5.9 billion has been obligated from the DRF after Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma to save lives and property through mission assignments made to over 50 federal entities and the American Red Cross (see Table 17), $160.4 million after Hurricane Gustav through 32 federal entities (see Table 18), and $441 million after Hurricane Ike through 30 federal entities (see Table 19). In total, federal agencies obligated roughly $6.5 billion for mission assignments after the five hurricanes.

The Small Business Administration approved almost 177,000 applications in the region for business, home, and economic injury loans, with a total loan value of almost $12 billion (Table 28 and Table 29).

The Department of Education obligated roughly $1.8 billion to the five states for elementary, secondary, and higher education assistance (Table 11).

This report also includes a brief summary of each hurricane and a discussion concerning federal to state cost-shares. Federal assistance to states is triggered when the President issues a major disaster declaration. In general, once declared the federal share for disaster recovery is 75% while the state pays for 25% of recovery costs. However, in some cases the federal share can be adjusted upward when a sufficient amount of damage has occurred, or when altered by Congress (or both). In addition, how much federal assistance is provided to states for major disasters is influenced not only by the declaration, but also by the percentage the federal government pays for the assistance. This report includes a cost-share discussion because some of these incidents received adjusted cost-shares in certain areas.

Federal Disaster Assistance After Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, Wilma, Gustav, and Ike

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- Hurricane Katrina

- Hurricanes Rita and Wilma

- Hurricanes Gustav and Ike

- Information Categories and Data Collection Methods

- Caveats and Limitations

- Section I: Summary of Gulf Coast Disaster Supplemental Appropriations

- Section II. Agency-Specific Information on Gulf Coast Hurricane Federal Assistance

- Department of Agriculture

- Agricultural Research Service

- Farm Service Agency

- Food and Nutrition Service

- Natural Resources Conservation Service

- Forest Service

- Rural Housing Service

- Rural Utilities Service

- Department of Commerce

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- Economic Development Administration Economic Adjustment Assistance Program

- Department of Defense (Civil)

- Army Corps of Engineers

- Department of Defense (Military)

- Military Personnel

- Operations and Maintenance

- Procurement

- Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation

- Military Construction (MILCON) and Family Housing

- Management Funds

- Other Department of Defense Programs

- Department of Education

- Elementary and Secondary Education

- Higher Education

- Department of Health and Human Services

- Administration for Children and Families

- Public Health and Medical Assistance

- Administrative Waivers

- Public Health Emergency Fund

- Department of Homeland Security

- Federal Emergency Management Agency

- FEMA Mission Assignments by Federal Entity

- Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

- Community Development Block Grants

- Rental Assistance/Section 8 Vouchers

- Supportive Housing

- Public Housing Repair

- Inspector General

- Department of Justice

- Legal Activities

- United States Marshals Service

- Federal Bureau of Investigation

- Drug Enforcement Administration

- Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives

- Federal Prison System (Bureau of Prisons)

- Office of Justice Programs

- Department of Labor

- Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) Dislocated Worker Activities

- Department of Transportation

- Federal Highway Administration: Emergency Relief Program (ER)

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)

- Federal Transit Administration (FTA)

- Department of Veterans Affairs

- Medical Center in New Orleans

- Armed Forces Retirement Homes

- Corporation for National and Community Service

- Environmental Protection Agency

- Hurricane Emergency Response Authorities

- EPA Hurricane Response

- Funding Narrative

- EPA Regular Appropriations

- The Federal Judiciary

- Small Business Administration

- Disaster Assistance Program

- Cost-Shares and Programmatic Considerations: Hurricanes Katrina, Wilma, Dennis, and Rita

- Administrative and Congressional Waivers of Cost-Shares

- Concluding Observations and Policy Questions

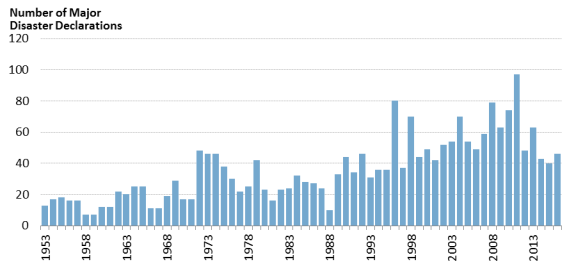

- Potential Methods for Controlling Costs Associated with Major Disasters

- Rationale for Keeping the Disaster Assistance the Same

- Limiting the Number of Major Disaster Declarations Being Issued

- The Use of State Capacity Indicators

- Expert Panels

- Emergency Loans

- Changes to the Stafford Act

- Reducing the Amount of Assistance Provided Through Declarations

- Policy Questions

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Estimated Gulf Coast Supplemental Appropriations for Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, Wilma, Gustav, and Ike

- Table 2. Disaster Relief Funding by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for 2005 Gulf Coast Hurricanes

- Table 3. 2005 Hurricane Disaster Relief Payments for Crops and Livestock by State

- Table 4. 2008 Agricultural Disaster Relief Program Payments by State

- Table 5. Disaster Relief Funding Through the Emergency Watershed Protection Program

- Table 6. Forest Service Programs Used to Grant Assistance after Hurricanes in 2005 and 2008

- Table 7. Forest Service 2005 and 2008 Hurricane Recovery Funding

- Table 8. Disaster Relief Funding for Commercial Fisheries

- Table 9. Disaster Relief Funding Appropriations for the Army Corps of Engineers

- Table 10. Disaster Relief Funding by the Department of Defense (Military)

- Table 11. Disaster Relief Funding Administered by the Department of Education Provided in Response to Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, Gustav, and Ike

- Table 12. Disaster Relief Funding for Programs at the HHS Administration for Children and Families

- Table 13. Disaster Relief Funding for Crisis Counseling, Mental Health, and Substance Abuse Services

- Table 14. Disaster Relief Funding for Health Care Costs and Infrastructure

- Table 15. Disaster Relief Funding for Communications Equipment and Mosquito Abatement

- Table 16. Disaster Relief Funding by the Federal Emergency Management Agency for Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, Wilma, Gustav, and Ike

- Table 17. Mission Assignment Funding by Agency: Hurricanes Katrina, Wilma, and Rita

- Table 18. Mission Assignments by Agency: Hurricane Gustav

- Table 19. Mission Assignments by Agency: Hurricane Ike

- Table 20. Distribution of CDBG Disaster Recovery Funds for Selected States, by Disaster Declaration

- Table 21. Disaster Relief Funding by the Department of Housing and Urban Development

- Table 22. Disaster Relief Funding for the Department of Justice

- Table 23. Disaster Relief Funding by the Department of Labor

- Table 24. Emergency Relief Obligations for Gulf Coast Hurricanes

- Table 25. Disaster Relief Funding by Modal Administration/Program

- TTable 26. Disaster Relief Supplemental Appropriations for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA): P.L. 109-148 and P.L. 109-234

- Table 27. Disaster Relief Funding by the Federal Judiciary

- Table 28. Small Business Administration: Number of Approved Disaster Assistance Loans For the Five Hurricanes

- Table 29. Small Business Administration: Approved Disaster Loan Applications by Amount

- Table 30. Disaster Relief Fund Annual Appropriations FY2007-FY2016

- Table A-1. Contributing Authors

Appendixes

Summary

This report provides information on federal financial assistance provided to the Gulf States after major disasters were declared in Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas in response to the widespread destruction that resulted from Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma in 2005 and Hurricanes Gustav and Ike in 2008.

Though the storms happened over a decade ago, Congress has remained interested in the types and amounts of federal assistance that were provided to the Gulf Coast for several reasons. This includes how the money has been spent, what resources have been provided to the region, and whether the money has reached the intended people and entities. The financial information is also useful for congressional oversight of the federal programs provided in response to the storms. It gives Congress a general idea of the federal assets that are needed and can be brought to bear when catastrophic disasters take place in the United States. Finally, the financial information from the storms can help frame the congressional debate concerning federal assistance for current and future disasters.

The financial information for the 2005 and 2008 Gulf Coast storms is provided in two sections of this report:

- 1. Table 1 of Section I summarizes disaster assistance supplemental appropriations enacted into public law primarily for the needs associated with the five hurricanes, with the information categorized by federal department and agency; and

- 2. Section II contains information on the federal assistance provided to the five Gulf Coast states through the most significant federal programs, or categories of programs.

The financial findings in this report include the following:

- Congress has appropriated roughly $121.7 billion in hurricane relief for the 2005 and 2008 hurricanes in 10 supplemental appropriations statutes.

- The appropriated funds have been distributed among 11 departments, 3 independent agencies/entities, numerous subentities, and the federal judiciary.

- Congress appropriated almost half of the funds ($53.8 billion, or 44% of the total) to the Department of Homeland Security, most of which went to the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

- Congress targeted roughly 22% of the total appropriations (almost $27 billion) to the Department of Housing and Urban Development for community development and housing programs.

- Approximately 20% ($25 billion) was appropriated to Department of Defense entities: $15.6 billion for civil construction and engineering activities undertaken by the Army Corps of Engineers and $9.2 billion for military personnel, operations, and construction costs.

- FEMA has reported that roughly $5.9 billion has been obligated from the DRF after Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma to save lives and property through mission assignments made to over 50 federal entities and the American Red Cross (see Table 17), $160.4 million after Hurricane Gustav through 32 federal entities (see Table 18), and $441 million after Hurricane Ike through 30 federal entities (see Table 19). In total, federal agencies obligated roughly $6.5 billion for mission assignments after the five hurricanes.

- The Small Business Administration approved almost 177,000 applications in the region for business, home, and economic injury loans, with a total loan value of almost $12 billion (Table 28 and Table 29).

- The Department of Education obligated roughly $1.8 billion to the five states for elementary, secondary, and higher education assistance (Table 11).

This report also includes a brief summary of each hurricane and a discussion concerning federal to state cost-shares. Federal assistance to states is triggered when the President issues a major disaster declaration. In general, once declared the federal share for disaster recovery is 75% while the state pays for 25% of recovery costs. However, in some cases the federal share can be adjusted upward when a sufficient amount of damage has occurred, or when altered by Congress (or both). In addition, how much federal assistance is provided to states for major disasters is influenced not only by the declaration, but also by the percentage the federal government pays for the assistance. This report includes a cost-share discussion because some of these incidents received adjusted cost-shares in certain areas.

Introduction

This report provides a comprehensive summary of the federal financial assistance provided to the Gulf Coast states of Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas in response to the widespread destruction that resulted from Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma in 2005 and Hurricanes Gustav and Ike in 2008.

The damages caused by the hurricanes are some of the worst in the history of the United States in terms of lives lost and property damaged and destroyed. The federal government played a significant role in the response to the hurricanes and Congress appropriated funds for a wide range of activities and efforts to help the Gulf Coast states recover and rebuild from the storms. In addition, Congress appropriated a significant amount of funds for mitigation activities and projects to reduce or eliminate the impacts of future storms.

Though the storms happened over a decade ago, Congress remains interested in the types and amounts of federal assistance that were provided to the Gulf Coast for several reasons. For one, Congress continues to be interested in how the money has been spent, what resources have been provided to the region, and whether the money has reached the people and entities intended to receive the funds. The financial information is also useful for congressional oversight and evaluation of the federal entities that were responsible for response and recovery operations. Similarly, it gives Congress a general idea of the federal assets that are needed and can be brought to bear when catastrophic disasters take place in the United States. As such, the financial information from the storms can help frame the congressional debate concerning federal assistance for current and future disasters.

The financial information provided in this report includes a summary of appropriations provided to the Gulf Coast states by Congress in response to the 2005 and 2008 hurricanes. In addition, when available, hurricane-specific and state-specific funding information is provided by federal entity.

Background1

The 2005 hurricane season was a record-breaking season for hurricanes and storms. There were 13 hurricanes in 2005, breaking the old record of 12 hurricanes set in 1969.2 The 2005 season also set a record for the number of category 5 storms (three) in a season.3 Most of the damaging effects caused by the hurricanes were experienced in the Gulf Coast states of Louisiana, Arkansas, Florida, Mississippi, and Texas. The 2008 hurricane season was also an active hurricane season that caused additional damage in the Gulf Coast.

Hurricane Katrina

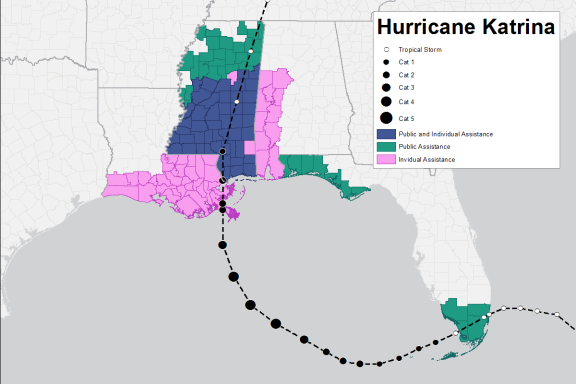

On August 23, 2005, Hurricane Katrina began about 200 miles southeast of Nassau in the Bahamas as a tropical depression. It became a tropical storm the following day. On August 24-25, 2005, the storm moved through the northwestern Bahamas and then turned westward toward southern Florida. Katrina became a hurricane just before making landfall near the Miami-Dade/Broward county line during the evening of August 25, 2005. The hurricane moved southwestward across southern Florida into the eastern Gulf of Mexico on August 26, 2005. Katrina then strengthened significantly, reaching category 5 intensity on August 28. On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina made landfall in southern Plaquemines Parish, LA. The storm affected a broad geographic area—stretching from Alabama, across coastal Mississippi, to southeast Louisiana. Hurricane Katrina was reported as a category 4 storm when it initially made landfall in Louisiana, but was later downgraded to a category 3 storm. Even as a category 3 storm, Hurricane Katrina was one of the strongest storms to impact the U.S. Gulf Coast. The force of the storm was significant. The winds to the east of the storm's center were estimated to be nearly 125 mph (see Figure 1).4

|

|

Source: Assistance information obtained from Federal Emergency Management Agency, Disasters, available at https://www.fema.gov/disasters; storm path information obtained from National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, Historical Hurricane Tracks, available at https://coast.noaa.gov/hurricanes/. Notes: Public Assistance covers the repairs or replacement of infrastructure (roads, bridges, public buildings, etc.) but also includes debris removal and emergency protective measures which may cover additional costs for local public safety groups incurred by their actions in responding to the disaster. Individual Assistance includes various forms of help for families and individuals following a disaster event. The assistance authorized by the Stafford Act can include housing assistance, disaster unemployment assistance, crisis counseling, and other programs intended to address the needs of people. |

The Gulf Coast has had a history of devastating hurricanes, but Hurricane Katrina was singular in many respects. Approximately 1.2 million people evacuated from the New Orleans metropolitan area.5 While the evacuation helped to save lives, over 1,800 people died in the storm.6 In addition, Hurricane Katrina destroyed or made uninhabitable an estimated 300,000 homes7 and displaced over 400,000 citizens.8 Economic losses from the storm were estimated to be between $125 billion and $150 billion.9

Hurricanes Rita and Wilma

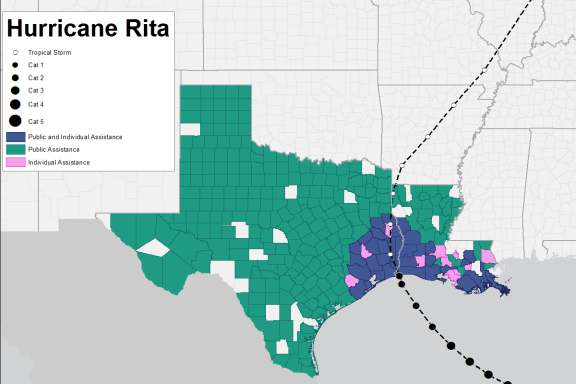

Two other hurricanes made landfall in the Gulf Coast shortly after Hurricane Katrina that added to recovery costs and impeded recovery efforts. On September 24, 2005, Hurricane Rita made landfall on the Texas and Louisiana border as a category 3 storm. Rita also hit parts of Arkansas and Florida. Hurricane Rita caused widespread property damage to the Gulf Coast; however, there were few deaths or injuries reported.10 Rita produced rainfalls of 5 to 9 inches over large portions of Louisiana, Mississippi, and eastern Texas, with isolated amounts of 10 to 15 inches.11 In addition, storm surge flooding and wind damage occurred in southwestern Louisiana and southeastern Texas, with some surge damage occurring in the Florida Keys (see Figure 2).12

|

|

Source: Assistance information obtained from Federal Emergency Management Agency, Disasters, available at https://www.fema.gov/disasters; storm path information obtained from National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, Historical Hurricane Tracks, available at https://coast.noaa.gov/hurricanes/. Notes: Public Assistance covers the repairs or replacement of infrastructure (roads, bridges, public buildings, etc.) but also includes debris removal and emergency protective measures which may cover additional costs for local public safety groups incurred by their actions in responding to the disaster. Individual Assistance includes various forms of help for families and individuals following a disaster event. The assistance authorized by the Stafford Act can include housing assistance, disaster unemployment assistance, crisis counseling, and other programs intended to address the needs of people. |

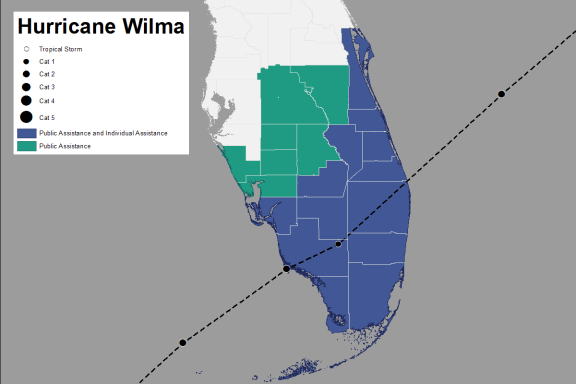

On October 24, 2005, Hurricane Wilma made landfall as a category 3 hurricane in Cape Romano, FL. The eye of Hurricane Wilma crossed the Florida Peninsula and then moved into the Atlantic Ocean north of Palm Beach (see Figure 3).13 Hurricane Wilma killed five people in Florida and caused widespread property damage in the Gulf Coast region.

|

|

Source: Assistance information obtained from Federal Emergency Management Agency, Disasters, available at https://www.fema.gov/disasters; storm path information obtained from National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, Historical Hurricane Tracks, available at https://coast.noaa.gov/hurricanes/. Notes: Public Assistance covers the repairs or replacement of infrastructure (roads, bridges, public buildings, etc.) but also includes debris removal and emergency protective measures which may cover additional costs for local public safety groups incurred by their actions in responding to the disaster. Individual Assistance includes various forms of help for families and individuals following a disaster event. The assistance authorized by the Stafford Act can include housing assistance, disaster unemployment assistance, crisis counseling, and other programs intended to address the needs of people. |

Hurricanes Gustav and Ike

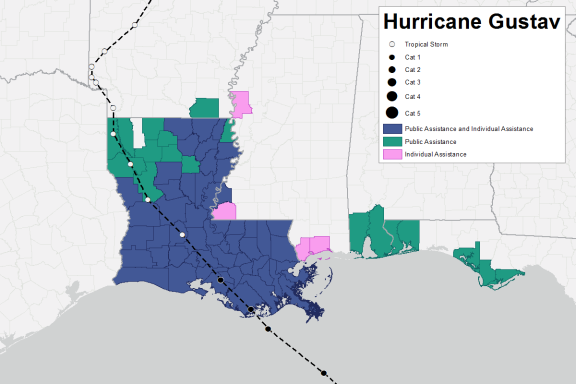

In 2008, the Gulf Coast was once again affected by storms that caused billions of dollars in additional damage. On September 1, 2008, Hurricane Gustav made landfall near Cocodrie, LA, as a category 2 storm, then swept across the region causing damages in Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, and Texas (see Figure 4). Gustav produced rains over Louisiana and Arkansas that caused moderate flooding along many rivers, and is known to have produced 41 tornadoes: 21 in Mississippi, 11 in Louisiana, 6 in Florida, 2 in Arkansas, and 1 in Alabama.14

|

|

Source: Assistance information obtained from Federal Emergency Management Agency, Disasters, available at https://www.fema.gov/disasters; storm path information obtained from National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, Historical Hurricane Tracks, available at https://coast.noaa.gov/hurricanes/. Notes: Public Assistance covers the repairs or replacement of infrastructure (roads, bridges, public buildings, etc.) but also includes debris removal and emergency protective measures which may cover additional costs for local public safety groups incurred by their actions in responding to the disaster. Individual Assistance includes various forms of help for families and individuals following a disaster event. The assistance authorized by the Stafford Act can include housing assistance, disaster unemployment assistance, crisis counseling, and other programs intended to address the needs of people. |

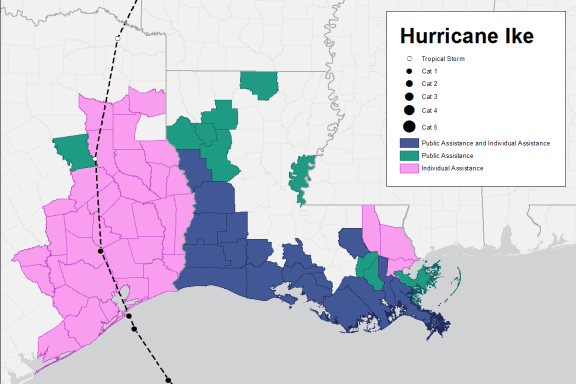

Hurricane Ike made landfall as a category 2 storm near Galveston, Texas, on September 13, 2008, with maximum sustained winds of 110 mph. The hurricane weakened as it moved inland across eastern Texas and Arkansas. Hurricane Ike's storm surge devastated the Bolivar Peninsula of Texas, and surge, winds, and flooding from heavy rains caused widespread damage in other portions of southeastern Texas, western Louisiana, and Arkansas and killed 20 people in these areas (see Figure 5).15 Additionally, as an extratropical system over the Ohio Valley, Ike was directly or indirectly responsible for 28 deaths and more than $1 billion in property damage in areas outside of the Gulf Coast.16

|

|

Source: Assistance information obtained from Federal Emergency Management Agency, Disasters, available at https://www.fema.gov/disasters; storm path information obtained from National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, Historical Hurricane Tracks, available at https://coast.noaa.gov/hurricanes/. Notes: Public Assistance covers the repairs or replacement of infrastructure (roads, bridges, public buildings, etc.) but also includes debris removal and emergency protective measures which may cover additional costs for local public safety groups incurred by their actions in responding to the disaster. Individual Assistance includes various forms of help for families and individuals following a disaster event. The assistance authorized by the Stafford Act can include housing assistance, disaster unemployment assistance, crisis counseling, and other programs intended to address the needs of people. |

Information Categories and Data Collection Methods

The following two sections provide funding data and narratives describing the assistance that was provided to the Gulf Coast in response to the 2005 and 2008 hurricane seasons. Section I presents funding provided to the five Gulf Coast states (Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas) after Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, Wilma, Gustav, and Ike. Funding amounts were compiled by CRS analysts who reviewed legislative texts of supplemental appropriations. The amounts are disaggregated by federal entity and subentity, insofar as possible and applicable. The data are based on the analysts' interpretations of disaster assistance. Some data were excluded from Section I because CRS analysts found that the data either were too ambiguous or covered disasters not limited to the Gulf Coast. Certain amounts pertaining to a range of disasters were included, however, because CRS analysts determined that most of the funds went to the Gulf Coast states.

Section II presents funding by federal agency. The amounts reported may reflect expenditures, obligations, allocations, or appropriations. The data in this section are not based solely on those in Section I. Rather, the data in Section II were derived from a variety of authoritative sources, including agency websites, CRS experts who received information directly from agencies, and governmental reports. Section II presents funding information by federal entity and includes a narrative summarizing each agency's disaster assistance efforts. The sections also provide the authorities that authorized the activities that were provided. When possible, funding data are provided in tabular form.

It should be noted that the data on appropriations in Section I, Table 1, are not directly comparable to funding data in Section II. The former were drawn solely from the public laws cited in the source note to Table 1. The data in Section II were obtained, as cited in each subsection, from a range of published and unpublished sources, and include various fiscal years.

Caveats and Limitations

Funding data on federal (and nonfederal) assistance are not systematically collected. Given the absence of comprehensive federal information on disaster assistance, the data provided in this report should only be considered as an approximation, and should not be viewed as definitive.

In addition to the above, the following caveats apply to this report:

- It is difficult to identify all of the federal entities that provide disaster relief because many federal entities provide aid through a wide range of programs, not necessarily through those designated specifically as "disaster assistance" programs.17

- Because data on federal (and nonfederal) assistance are not systematically collected, funding data were drawn from a wide range of sources including published and unpublished data that have been collected at different times and under inconsistent reporting methods.

- Following the exodus of thousands of residents from the Gulf Coast states after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, many other states received federal assistance to cope with the influx of those seeking aid. The aid provided to the states outside the Gulf Coast is not discussed in this report.

- The appropriations language reviewed for Section I usually designates funds to a federal entity for a range of disasters without identifying how much funding is to be disbursed to each incident. For example, P.L. 110-329, signed into law on September 30, 2008, provided funds for several disasters that occurred in 2008, including Hurricanes Gustav and Ike, wildfires in California, and the Midwest floods. Determining the funding amounts directed toward each individual disaster is difficult, if not impossible, unless the legislative text specifies these amounts. An additional difficulty occurs in tracking funding at the agency level because appropriations might be made, not to specific entities, but to budget accounts, and then allocated for specified purposes.

- The degree of transparency in reporting funding levels for disaster relief varies tremendously among federal entities. As an example, Congress requires the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to submit monthly status reports on the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF).18 The DRF is FEMA's disaster assistance account. The DRF is used to fund existing recovery projects (including reimbursements to other federal agencies for their work) and provide funding for future emergencies and disasters as needed. The DRF reports must detail obligations, allocations, and expenditures for Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma. This requirement has not been extended to other agencies, and scant data exist, particularly on a state-by-state basis, on other federal funding for emergencies and major disasters.

- Appropriations may be subject to transfers or rescissions after enactment of appropriations statutes. It is possible that such emendations to the initial appropriations have not been identified in this research.

In addition to the above caveats, it should also be noted that there may have been funding changes since this report was originally published in 2013 that are not represented in this updated version. In some cases, additional obligations may have been provided and in other cases some funding may have been recouped or otherwise transferred. The funding information in this report should therefore be interpreted as illustrative as opposed to definitive, and used with appropriate caution.

Section I: Summary of Gulf Coast Disaster Supplemental Appropriations

Table 1 presents data on the appropriations enacted after Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, Wilma, Gustav, and Ike from FY2005 to FY2009, by federal entity and subentity, when possible and applicable. As mentioned earlier, in many cases funding for disaster relief is appropriated for multiple incidents. Therefore, Table 1 may include data on appropriations that also provided funding for non-Gulf Coast incidents. Some appropriations designated for a range of disasters were excluded, however, in an attempt to avoid artificially inflating the amount of funding directed to the Gulf Coast for hurricane relief.

Since FY2005, at least 10 appropriations bills have been enacted to address widespread destruction caused by the 2005 and 2008 Gulf Coast hurricanes. These appropriations consisted of eight emergency supplemental appropriations acts, one reconciliation act, and one continuing appropriations resolution.19 In addition to these statutes that specifically identify the hurricanes or the Gulf Coast states, it is likely that regular appropriations legislation also provided assistance to the Gulf Coast. Because these statutes did not specify that they were providing such assistance, regular appropriations are not included in Table 1.

Table 1. Estimated Gulf Coast Supplemental Appropriations for Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, Wilma, Gustav, and Ike

(Disaster-Related Supplemental Appropriations by Department/Agency; Nominal Dollars in Millions)

|

Department/Agency/Program |

Estimated Appropriation |

|

DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE |

|

|

Emergency Forestry Conservation Reserve Program |

$82 |

|

Agricultural Research Service |

$39 |

|

Emergency Conservation Program |

$73 |

|

Farm Service Agency |

$242 |

|

Executive Operations |

$60 |

|

Food and Nutrition Service Commodity Assistance |

$10 |

|

Forest Service |

$77 |

|

Inspector General |

* |

|

Natural Resources Conservation Service |

$351 |

|

Other Emergency Appropriations |

* |

|

Rural Housing Service |

$90 |

|

Rural Utility Service |

$53 |

|

Subtotal |

$1,077 |

|

DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE |

|

|

Department of Commerce (nonspecified) |

$400 |

|

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

$85 |

|

Marine Fishery Emergency Assistance Program |

$260 |

|

Subtotal |

$745 |

|

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE (MILITARY) |

|

|

Military Personnel |

$540 |

|

Operations and Maintenance |

$3,684 |

|

Procurement |

$2,850 |

|

Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation |

$54 |

|

Military Construction and Family Housing |

$1,785 |

|

Management Funds |

$66 |

|

Other Defense |

$236 |

|

Subtotal |

$9,215a |

|

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE (CIVIL) |

|

|

Army Corps of Engineers Construction |

$4,951 |

|

Flood Control and Coastal Emergencies |

$9,926 |

|

Flood Damage Construction for FEMA |

* |

|

Mississippi River and Tributaries |

$154 |

|

General Expenses |

$3 |

|

Investigations |

$43 |

|

Operations and Maintenance |

$516 |

|

Subtotal |

$15,593 |

|

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION |

|

|

Office of Elementary and Secondary Education |

$1,689 |

|

Office of Postsecondary Education |

$292 |

|

Subtotal |

$1,981 |

|

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES |

|

|

Health Resources and Services Administration |

$4 |

|

Administration for Children and Families |

$1,240 |

|

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

$8 |

|

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services |

$2,000 |

|

Subtotal |

$3,252 |

|

DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY |

|

|

Department of Homeland Security (nonspecified) |

$9,157 |

|

Customs and Border Protection |

$52 |

|

Federal Emergency Management Agency |

$44,083b |

|

Immigration and Customs Enforcement |

$13 |

|

Office of Domestic Preparedness |

$10 |

|

Office of Inspector General |

$2 |

|

United States Coast Guard |

$487 |

|

United States Secret Service |

$4 |

|

Subtotal |

$53,808 |

|

DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT |

|

|

Community Development Block Grants |

$26,200 |

|

Rental Assistance/Section 8 Vouchers |

$555 |

|

Supportive Housing |

$73 |

|

Public Housing Repair |

$15 |

|

Office of Inspector General |

$7 |

|

Subtotal |

$26,850 |

|

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR |

|

|

Department of the Interior |

$210 |

|

Bureau of Reclamation |

$9 |

|

Mineral Management Service |

$31 |

|

National Park Service |

$117 |

|

National Park Service Historical Preservation Fund |

* |

|

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |

$162 |

|

U.S. Geological Survey |

$16 |

|

Subtotal |

$545 |

|

DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE |

|

|

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives |

$20 |

|

Drug Enforcement Administration |

$10 |

|

Federal Bureau of Investigation |

$45 |

|

Federal Prison System |

$11 |

|

Legal Activities |

$18 |

|

Office of Justice Programs |

$175 |

|

U.S. Marshals Service |

$9 |

|

Subtotal |

$288 |

|

DEPARTMENT OF LABOR |

|

|

Job Corps |

$16 |

|

Employment and Training Administration |

$125 |

|

Subtotal |

$141 |

|

DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION |

|

|

Department of Transportation (nonspecified) |

$722 |

|

Federal Aviation Administration |

$41 |

|

Federal Highway Administration |

$2,751 |

|

Federal Transportation Administration Grants |

* |

|

Maritime Administration |

$8 |

|

Subtotal |

$3,522 |

|

DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS |

|

|

Department Administration |

$62 |

|

Veterans Health Administration |

$198 |

|

Major Construction—Medical Facilities |

$918 |

|

Subtotal |

$1,178 |

|

ARMED FORCES RETIREMENT HOME |

|

|

Armed Forces Retirement Home |

$242 |

|

Subtotal |

$242 |

|

ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY |

|

|

Environmental Protection Agency (nonspecified) |

$21 |

|

Subtotal |

$21 |

|

GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION |

|

|

General Services Administration (nonspecified) |

$75 |

|

Subtotal |

$75 |

|

SMALL BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION |

|

|

Small Business Administration (nonspecified) |

$2,279 |

|

Disaster Loans Program Account |

$441 |

|

Inspector General |

$5 |

|

Subtotal |

$2,725 |

|

THE JUDICIARY |

|

|

The Federal Judiciary (nonspecified) |

$18 |

|

Subtotal |

$18 |

|

NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION |

|

|

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (nonspecified) |

$385 |

|

Exploration Capabilities as a Consequence of Katrina |

* |

|

Subtotal |

$385 |

|

CORPORATION FOR NATIONAL AND COMMUNITY SERVICE |

|

|

Corporation for National and Community Service |

$10 |

|

Subtotal |

$10 |

|

Grand Total |

$121,661 |

Source: Data derived from CRS database of appropriations. Statutes include P.L. 109-61, P.L. 109-62, P.L. 109-148, P.L. 109-171, P.L. 109-234, P.L. 110-28, P.L. 110-116, P.L. 110-252, P.L. 110-329, and P.L. 111-32. This table may not reflect rescissions applied after Congress appropriated these funds.

Notes: * Signifies appropriation of less than $1 million. Cells marked as "nonspecified" indicate appropriations funded to a department generally.

a. This figure represents the amount appropriated after rescission of funds; it does not reflect that $1.5 billion of these funds expired in FY2006 or were transferred for other purposes.

b. P.L. 109-62 (119 Stat. 1991) appropriated $50 billion for the Disaster Relief Fund. P.L. 109-148 (119 Stat. 2790) rescinded $23.4 billion of those funds.

Section II. Agency-Specific Information on Gulf Coast Hurricane Federal Assistance

In the course of this research, CRS identified 11 federal departments, 4 federal agencies (or other entities), and numerous subentities, programs, and activities that supplied roughly $121.7 billion in federal assistance to the Gulf Coast states after the major hurricanes of 2005 (Katrina, Rita, and Wilma) and 2008 (Gustav and Ike). Section II provides information on the most significant programs, or categories of programs, through which the aid was provided. Each narrative contains a summary of activities of each federal entity providing disaster relief. When possible, the information is presented in tabular form and is disaster and state specific. Unless otherwise specified, all figures are stated in nominal dollars.

As mentioned earlier, the data in Section II may not correspond to the emergency funds appropriated by Congress for hurricane relief purposes specified in Section I. Reasons for the difference include the following:

- the tables in Section II present information from a variety of funding measures, including obligations, allocations, and expenditures;20

- some funds made available may have been reallocated or deobligated from other purposes; and

- money from accounts that did not terminate at the end of a fiscal year (known as no-year accounts) may have been allocated to the Gulf Coast states.

Department of Agriculture21

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) provides a variety of disaster assistance for hurricanes and other natural disasters. For the hurricanes covered in this report, the bulk of the department's funding has been disaster payments to producers who suffered production losses and funding for land rehabilitation programs for cleanup and restoration projects, primarily under P.L. 109-234 and through other authorities.22 The total USDA budget authority was over $1.0 billion for disaster relief following Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma (Table 2). For these three hurricanes, USDA also paid an additional $112 million in farm disaster benefits to farmers in the Gulf States under various Farm Service Agency indemnity and grant programs, using funds allocated from USDA's "Section 32" Program (see "Farm Service Agency" section below).23

Hurricane-related support by individual agency for the 2005 and 2008 hurricanes is described in separate sections below. State-specific data are provided where available and are current as of the dates cited.

Table 2. Disaster Relief Funding by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for 2005 Gulf Coast Hurricanes

(Dollars in Thousands)

|

Department of Agriculture |

Budget Authority |

Obligations |

Outlays |

|

Agricultural Research Service |

$39,000 |

$38,000 |

$37,000 |

|

Farm Service Agency |

|||

|

Disaster payments-crop/livestock losses (excludes Section 32) |

$132,300 |

$132,300 |

$132,300 |

|

Emergency Forestry Conservation Reserve Program (EFCRP) |

$81,800 |

$81,800 |

$68,600 |

|

Emergency Conservation Program (ECP) |

$84,700 |

$73,400 |

$44,800 |

|

Food and Nutrition Service |

$10,000 |

$10,000 |

$9,000 |

|

Forest Service |

$77,000 |

$77,000 |

$77,000 |

|

Office of Inspector General |

$445 |

$445 |

$445 |

|

Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) |

$351,000 |

$300,000 |

$287,000 |

|

Rural Housing Service |

$128,000 |

$101,000 |

$63,000 |

|

Rural Utilities Service |

$53,000 |

$34,000 |

$14,000 |

|

Working Capital Fund |

$60,000 |

$59,000 |

$59,000 |

|

Total |

$1,017,245 |

$906,945 |

$792,145 |

Source: Budget Data Request No. 11-31 requested June 27, 2011, and provided July 20, 2011. Submission by Office of Budget and Program Analysis, U.S. Department of Agriculture, to Office of Management and Budget.

Notes: Figures are for Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma in support of Gulf Coast recovery efforts and include disaster payments made under P.L. 109-234. Excludes disaster payments made under Section 32 (see Table 3) and disaster payments made under the Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-246, 2008 farm bill, see Table 4).

Agricultural Research Service

The Agricultural Research Service (ARS) is USDA's chief scientific research agency. Under P.L. 109-234, USDA received funding for cleanup and salvage efforts at the ARS facility in Poplarville, MS, and the Southern Regional Research Center in New Orleans, LA. Total budget authority was $39 million for the 2005 hurricanes provided under P.L. 109-234 and through reallocations from existing funds.

Farm Service Agency

The mission of the Farm Service Agency (FSA) is to serve farmers, ranchers, and agricultural partners through the delivery of agricultural support programs. Besides administering general farm commodity programs, FSA administers disaster payments for crop and livestock farmers who suffer losses from natural disasters. Following the 2005 hurricanes, producer benefits were provided under five new programs created by USDA for tropical fruit, citrus, sugarcane, nursery crops, fruits and vegetables, livestock death, feed losses, and dairy production and spoilage losses. These USDA-created programs were the Hurricane Indemnity Program (HIP), Livestock Indemnity Program (LIP), Feed Indemnity Program (FIP), and an Aquaculture Grant Program (AGP). Payments under the previously established Tree Indemnity Program (TIP) were provided to eligible owners of commercially grown fruit trees, nut trees, bushes, and vines producing annual crops that were lost or damaged.24

Total outlays for 2005 hurricanes to the Gulf States under the aforementioned five programs were $132 million under P.L. 109-234 (see Table 2) and $112 million for four programs under "Section 32" (see Table 3 for Section 32 data). Section 32 is a permanent appropriation (originating from P.L. 74-320) that supports a variety of USDA activities, including disaster relief, federal child nutrition programs, and surplus commodity purchases.25

Table 3. 2005 Hurricane Disaster Relief Payments for Crops and Livestock by State

(Dollars in Thousands)

|

Alabama |

Florida |

Louisiana |

Mississippi |

North Carolina |

Texas |

Total |

|

|

Hurricane Indemnity Program (HIP) |

$3,002 |

$31,164 |

$3,049 |

$2,061 |

— |

$282 |

$39,558 |

|

Tree Indemnity Program (TIP) |

$604 |

$18,144 |

$376 |

$833 |

— |

$28 |

$19,985 |

|

Feed Indemnity Program (FIP) |

$902 |

$1,719 |

$1,050 |

$1,156 |

— |

$27 |

$4,854 |

|

Livestock Indemnity Program (LIP) |

$265 |

$709 |

$19,238 |

$2,148 |

— |

$701 |

$23,061 |

|

Aquaculture Grant Program (AGP) |

$5,038 |

$3,663 |

$4,513 |

$10,738 |

$313 |

$661 |

$24,690 |

|

Total |

$9,811 |

$55,399 |

$28,226 |

$16,936 |

$313 |

$1,699 |

$112,384 |

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Farm Service Agency, November 6, 2017.

Notes: Latest payment data available from USDA for 2005 hurricanes, as of November 6, 2017; the above programs were administered by FSA with funding allocated from USDA's "Section 32" Program.

Following Hurricanes Gustav and Ike in 2008, payments were provided to qualifying producers under five nationwide agricultural disaster programs authorized in the Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-246, 2008 farm bill). Under the largest disaster program, Supplemental Revenue Assistance Payments Program (SURE),26 the combined payments for Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas totaled $285 million in 2008 for a variety of natural disaster losses, including hurricane damage (Table 4). Payments for these states under the other four programs (three livestock-related programs and the Tree Assistance Program (TAP)) were approximately $66 million.27

|

Alabama |

Florida |

Louisiana |

Mississippi |

Texas |

Total |

|

|

Supplemental Revenue Assistance Payments Program (SURE) |

$5,005 |

$12,932 |

$13,068 |

$4,993 |

$249,002 |

$285,000 |

|

Livestock Forage Program (LFP) |

$9,002 |

$2,688 |

— |

— |

$40,182 |

$51,872 |

|

Livestock Indemnity Program (LIP) |

$34 |

$64 |

$1,301 |

$91 |

$6,359 |

$7,849 |

|

Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honeybees and Farm-Raised Fish Program (ELAP) |

$81 |

$2,918 |

$776 |

$10 |

$659 |

$4,443 |

|

Tree Assistance Program (TAP) |

— |

$1,802 |

< $1 |

— |

$146 |

$1,948 |

|

Total |

$14,122 |

$20,404 |

$15,145 |

$5,094 |

$296,348 |

$351,112 |

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Farm Service Agency, November 6, 2017.

Notes: Programs were authorized under the Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-246, 2008 farm bill). Payments as of November 6, 2017, and made for a variety of natural disaster losses that included more than just hurricane damage.

FSA also administered two land rehabilitation disaster programs: (1) the Emergency Forestry Conservation Reserve Program (EFCRP),28 which compensated private, nonindustrial forest landowners who experienced losses from hurricanes in calendar year 2005, for temporarily retiring their land; and (2) the Emergency Conservation Program (ECP),29 which provides emergency funding and technical assistance for farmers and ranchers to rehabilitate farmland damaged by natural disasters.

For the 2005 hurricanes, Congress provided $82 million in budget authority for EFCRP and $84.7 million in budget authority for ECP. Of the $84.7 million in budget authority for ECP, FSA obligated over $70 million. Previously unobligated funds from 2005 hurricane recovery efforts were reprogrammed in 2009 under P.L. 111-32 to be used for then current disasters, including hurricanes. On July 14, 2009, USDA announced $71 million in ECP funding, which included the 2005 reprogrammed funds, for repairing farmland damaged by natural disasters, including the hurricanes that occurred in 2008. Of the five hurricane-affected states, Texas received the largest allocation ($11 million) to address 2008 hurricane restoration efforts.

Food and Nutrition Service30

The Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) administers several programs that are crucial in hurricane relief efforts.31 These include the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as the Food Stamp Program (FSP)), child nutrition programs (e.g., school meals programs), and federally donated food commodities delivered through relief organizations. Existing laws authorize USDA to change eligibility and benefit rules to facilitate emergency aid. Disaster FSP benefits provided approximately $1 billion worth of support directly due to Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, Wilma, Gustav, and Ike.32 Assistance provided by FSP (now, SNAP) and the child nutrition programs required no additional appropriations because the benefits are treated as entitlements.

Other than a small one-time increase in appropriations, in P.L. 109-148, to replenish some commodity stocks used for hurricane-relief purposes, no significant action was taken for hurricane relief or to pay for commodity distribution costs. This is because funding and federally provided food commodities were generally available without a need for a large appropriation.

Natural Resources Conservation Service

The Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) assists private land owners with conserving soil, water, and other natural resources. Following natural disasters, NRCS works with FEMA, state and federal agencies, and local units of government to conduct postdisaster cleanup and restoration projects. NRCS administers the Emergency Watershed Protection (EWP) Program,33 which assists landowners and operators in implementing emergency recovery measures for slowing runoff and preventing erosion to relieve imminent hazards to life and property created by a natural disaster that causes a sudden impairment of a watershed. In the wake of 2005 and 2008 hurricane events, NRCS staff also assessed the demand and requirements for the disposal of animal carcasses, through authority delegated by FEMA. As of November 29, 2012, NRCS had obligated approximately $300 million for disaster relief stemming from these hurricanes. State EWP data for the 2005 and 2008 hurricanes are provided in Table 5 below.

Table 5. Disaster Relief Funding Through the Emergency Watershed Protection Program

(Dollars in Thousands)

|

Hurricane |

Alabama |

Florida |

Louisiana |

Mississippi |

Tennessee |

Texas |

Total |

|

Katrina |

$21,300 |

$7,200 |

$44,900 |

$114,200 |

$400 |

— |

$188,000 |

|

Rita |

— |

— |

$43,800 |

$2,400 |

— |

$12,700 |

$58,900 |

|

Wilma |

— |

$12,840 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

$12,840 |

|

Gustav |

$600 |

$600 |

$12,600 |

$600 |

— |

— |

$14,400 |

|

Ike |

— |

— |

$12,000 |

— |

— |

$12,800 |

$24,800 |

|

Total |

$21,900 |

$20,640 |

$113,300 |

$117,200 |

$400 |

$25,500 |

$298,940 |

Source: USDA, NRCS, November 29, 2012.

Forest Service34

The Forest Service (FS) administers programs for protecting and managing the natural resources of the National Forest System (NFS, primarily national forests and national grasslands) and for assisting states and nonindustrial private forestland owners in protecting and managing the natural resources of nonfederal forestlands. Through its State and Private Forestry (SPF) program, the FS provides financial and technical assistance, typically through state forestry agencies, to nonfederal landowners to restore forests damaged by hurricanes (and other disasters). The state agencies are authorized to use such funds in numerous ways, such as assisting landowners to clear damaged trees and to plant new stands on cleared sites. While emergency and supplemental funding is sometimes enacted for natural disasters (e.g., hurricanes), the funding often is expended through ongoing, existing programs, and commonly cannot be distinguished from regular appropriations for these purposes (i.e., protecting and managing NFS lands and resources and assisting nonfederal landowners in protecting and managing their forests).

Funding for the FS to conduct work after a natural disaster can be categorized generally as response efforts and recovery efforts. Response tasks are identified through the National Response Framework (NRF), administered by FEMA, which grants the FS certain responsibilities (e.g., firefighting) to coordinate during a presidentially declared emergency or major disaster.35 The FS reports it spent approximately $77 million for Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma, respectively, on response efforts in FS region 8 (state-level data were not available).36 The FS estimates it spent a total of $2.5 million on response efforts for Hurricane Gustav ($1.4 million in Alabama, $0.9 million in Louisiana, $0.1 million in Mississippi, and $0.1 million in Texas).37 The FS reports it spent a total of $2.1 million on response efforts for Hurricane Ike (all funding spent in Texas).

Although the FS does not have the authority for specific programs to grant recovery assistance to states, the FS can use its regular program authorities to assist state and private landowners broadly following a disaster. For example, after a hurricane, the FS may receive supplemental funding under the state and private forestry (SPF) programs appropriation to conduct recovery work via a SPF program. Eight existing FS programs were used to assist the states following Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, Wilma, Gustav, and Ike (see Table 6).38 The FS may also grant funding for the FSA Emergency Forest Restoration Program.39 FS recovery funding amounts by state for the 2005 hurricanes (Katrina, Rita, and Wilma) and 2008 hurricanes (Gustav and Ike) are provided in Table 7.

|

Program |

Purpose |

Authority |

|

Cooperative Forest Health Protection |

Provides federal financial and technical assistance to states to facilitate their survey and monitoring of forest health conditions and for the protection of forests and trees on state and private lands from insects, disease causing agents, and invasive plants. |

16 U.S.C. §2104 |

|

Economic Action Program |

Assists communities and their leaders in improving the efficiency and marketing of natural resource-based industries and in diversifying rural community economic bases. |

7 U.S.C. §§6611-6617 |

|

Emergency Forestry Conservation Reserve Program (temporary) |

Provides assistance to nonindustrial private forest landowners who experienced a loss of 35% or more in merchantable timber from the 2005 hurricanes (Hurricane Katrina et al.). |

P.L. 109-148 Section 107 |

|

Forest Stewardship |

Improves timber production and environmental protection on nonfederal forest lands. |

16 U.S.C. §2103a |

|

Hazard Fuel Mitigation |

Assists communities in reducing threats from wildfires. |

16 U.S.C. §2106 |

|

State Fire Assistance |

Provides technical and financial assistance to state cooperators. |

16 U.S.C. §2106 |

|

Urban and Community Forestry |

Expands knowledge and awareness of the value of urban trees and encourages the maintenance and expansion of urban tree cover. |

16 U.S.C. §2105 |

|

Volunteer Fire Assistance |

Provides federal financial, technical, and other assistance to state foresters and other appropriate officials to organize, train, and equip fire departments in rural areas and rural communities to prevent and suppress fires. |

16 U.S.C. §2106 |

Source: Compiled by CRS.

|

Hurricane Year |

State |

Program |

FS Obligations |

|

2005 |

Alabama |

Forest Stewardship |

$474 |

|

2005 |

Alabama |

Cooperative Forest Health Protection |

$90 |

|

2005 |

Alabama |

Economic Action/Rural Development |

$45 |

|

2005 |

Alabama |

State Fire Assistance |

$369 |

|

2005 |

Alabama |

Urban and Community Forestry |

$255 |

|

2005 |

Alabama |

Volunteer Fire Assistance |

$50 |

|

|

Totals |

$1,282 |

|

|

2005 |

Florida |

Urban and Community Forestry |

$615 |

|

2005 |

Louisiana |

Urban and Community Forestry/ State Fire Assistance/ Forest Stewardship/ Cooperative Forest Health Protectiona |

$7,971 |

|

2005 |

Louisiana |

Volunteer Fire Assistance |

$517 |

|

|

Totals |

$8,489 |

|

|

2005 |

Mississippi |

Economic Action/Rural Development |

$160 |

|

2005 |

Mississippi |

Urban and Community Forestry/ State Fire Assistance/ Forest Stewardship/ Cooperative Forest Health Protectiona |

$11,519 |

|

2005 |

Mississippi |

Volunteer Fire Assistance |

$553 |

|

|

Totals |

$12,232 |

|

|

2005 |

Texas |

Economic Action/Rural Development |

$83 |

|

2005 |

Texas |

Urban and Community Forestry/ State Fire Assistance/ Forest Stewardship/ Cooperative Forest Health Protectiona |

$4,679 |

|

|

Totals |

$4,763 |

|

|

2008 |

Texas |

State Fire Assistance |

$4,089 |

|

2008 |

Texas |

Urban and Community Forestry (Carryover) |

$50 |

|

|

Totals |

$4,139 |

Rural Housing Service

The Rural Housing Service (RHS) provides loan and grant assistance for single-family and multifamily housing. RHS also administers the Community Facilities loan and grant program to provide assistance to communities for health facilities, fire and police stations, and other essential community facilities. Following the hurricanes, RHS provided housing relief to residents of the affected areas through payment moratoriums of six months, a three-month moratorium on initiating foreclosures under the single family guaranteed homeownership loans, loan forgiveness, loan reamortization, and refinancing. In addition, RHS provided temporary rental assistance to displaced family farm labor housing tenants. Assistance was provided for single-family homeowners (e.g., Section 502 loans), multifamily housing owners (e.g., Section 504 loans), and rental housing assistance (Section 521). Under P.L. 109-234, total budget authority for RHS programs for the 2005 hurricanes was $128 million.

The Disaster Relief and Recovery Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-329) provided funding for activities under the Rural Development Mission Area for relief and recovery from natural disasters (including hurricanes) during 2008. The act specifically provided $38 million for activities of the Rural Housing Service for areas affected by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita.

Rural Utilities Service

The Rural Utilities Service (RUS) is responsible for administering electric, telecommunications, and water assistance programs that help finance the infrastructure necessary to improve the quality of life and promote economic development in rural areas. Hurricane relief included grants for rebuilding, repairing, or otherwise improving water and waste disposal systems in designated disaster areas. Increased technical assistance under the Circuit Rider program was also provided to rural water districts. With the approval of lenders, RUS also suspended preauthorized debit payments for water and waste disposal loan guarantees for six months. Under permanent authority of P.L. 92-419, total budget authority for RUS programs for the 2005 hurricanes was $53 million.

Department of Commerce

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration40

The federal government may provide disaster relief to the fishing industry when there is a commercial fishery failure. A commercial fishery failure occurs when fishermen endure hardships resulting from fish population declines or other disruptions to the fishery. Two statutes, the Interjurisdictional Fisheries Act (16 U.S.C. §4107) and the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (16 U.S.C. §1864a and §1864), provide the authority and requirements for fishery disaster assistance. Under both statutes, a request for a fishery disaster determination is generally made by the governor of a state, or by a fishing community, although the Secretary of Commerce may also initiate a review at his or her own discretion. If the Secretary determines that a fishery disaster has occurred, Congress may appropriate funds for disaster assistance, which are administered by the Secretary. Funding is usually distributed as grants to states or regional marine fisheries commissions by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) of the Department of Commerce.

Since 2005, Congress has appropriated almost $260 million of hurricane disaster relief to the Gulf of Mexico fishing industry (see Table 8). Of this total, $213 million was appropriated for damages and disruptions caused by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita (P.L. 109-234 and P.L. 110-28). Assistance provided for the direct needs of fishermen and related businesses, and supported related fisheries programs such as oyster bed and fishery habitat restoration, cooperative research, product marketing, fishing gear studies, and seafood testing. Many of these activities such as habitat restoration are ongoing management priorities for these fisheries. For damage caused by Hurricanes Gustav and Ike, $47 million was appropriated to restore damaged oyster reefs, remove storm debris, and rebuild fishing infrastructure in Texas and Louisiana (P.L. 110-329). In addition, $85 million was provided to NOAA for scanning, mapping, and removing marine debris; repairing and reconstructing the NOAA Science Center; procuring a replacement emergency response aircraft and sensor package; and other activities (P.L. 109-234 and P.L. 110-28).

Table 8. Disaster Relief Funding for Commercial Fisheries

(Obligations as of October 2017; Dollars in Thousands)

|

Commercial Fishery Disaster Assistance |

Alabama |

Florida |

Louisiana |

Mississippi |

Texas |

Total |

|

Total |

$44,633 |

$6,233 |

$134,190 |

$62,042 |

$11,375 |

$258,473 |

Source: NOAA Budget Office, personal communication, November 1, 2017. Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission, Emergency Disaster Recovery Program, available at http://www.gsmfc.org/fdrp.php.

Notes: According to NOAA, all funds have been expended except for approximately $79,000. The total does not add to $260 million because $1,527 thousand was allocated for program administration. The table does not include funding for NOAA programs.

Economic Development Administration Economic Adjustment Assistance Program41

The Economic Development Administration (EDA) was created with the passage of the Public Works and Economic Development Act of 1965 (PWEDA), P.L. 89-136, (42 U.S.C. §3121, et. al) to provide assistance to communities experiencing long-term economic distress or sudden economic dislocation. Among the programs administered by EDA is the Economic Adjustment Assistance (EAA) program. The PWEDA (42 U.S.C. §3149(c)(2)) authorizes EDA to provide EAA funds for

disasters or emergencies, in areas with respect to which a major disaster or emergency has been declared under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act for post-disaster economic recovery.42

In addition to funding disaster-recovery efforts using Emergency Assistance Act (EAA) funds available under its regular appropriation, 42 U.S.C. §3233 authorizes the appropriation of such sums as are necessary to fund EAA disaster recovery activities authorized under 42 U.S.C. §3149(c)(2). Funds appropriated under 42 U.S.C. §3233 may be used to cover up to 100% of the cost of a project or activity authorized under 42 U.S.C. §3149(c)(2). Funds appropriated under a regular appropriations act may be used to cover only 50% of the cost of disaster recovery activities. However, the authorizing statute also grants EDA the authority to increase the federal share of a project's cost to 100%.

Disaster Assistance Grants

Presidentially declared disasters or emergencies are one of five specific qualifying events eligible for EAA funding assistance.43 EAA grants are competitively awarded and may be used to help finance public facilities; public services (including job training and counseling) business development (including funding a revolving loan fund (RLF); planning; and technical assistance that support the creation or retention of private sector jobs. Regions submitting an application for EAA disaster assistance must demonstrate a clear connection between the proposed project and disaster recovery efforts. EAA disaster grants can cover 100% of a project's cost.

In order to qualify for assistance, the Secretary of Commerce must find that a proposed project or activity will help the area respond to a severe increase in unemployment, or economic adjustment problems resulting from severe changes in economic conditions. EAA regulations also require an area seeking such assistance to prepare or have in place a Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) outlining the nature and level of economic distress in the region, and proposed activities that could be undertaken to support private-sector job creation or retention efforts in the area.

Funding Narrative

Congress did not provide EAA supplemental appropriations for disaster recovery activities related to Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, or Wilma. However, EDA allocated $24.2 million from its regular appropriations in response to the hurricanes of 2005. In response to Hurricanes Gustav and Ike and other disasters occurring in 2008, Congress appropriated $400 million in EAA disaster supplemental funding when it approved P.L. 110-329. It also appropriated an additional $100 million in supplemental EAA disaster assistance without limiting it to disasters occurring in a specific year when it passed the Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2008, P.L. 110-252.

Of the $500 million appropriated for EAA disaster grants in 2008, EDA allocated, based on its 2010 annual report to Congress, the latest data available, a total of $63.8 million to 33 recipients in five of the six states identified in this report.

Department of Defense (Civil)44

Army Corps of Engineers

Civil Works Program

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) is a unique federal agency in the Department of Defense, with military and civilian responsibilities. Under its civil works program, the Corps plans, builds, operates, and maintains a wide range of water resources facilities, including hurricane protection and flood damage reduction projects, and performs emergency actions for flood and coastal emergencies.

Table 9 shows, for each Gulf Coast state, the direct appropriations that the Corps received for its water resources work related to the five hurricanes. According to data the Corps provided to CRS, of the total $15.6 billion appropriated, more than $11.2 billion has been obligated.

Table 9. Disaster Relief Funding Appropriations for the Army Corps of Engineers

(Dollars in Thousands)

|

Army Corps of Engineers |

Alabama |

Florida |

Louisiana |

Mississippi |

Texas |

Total |

|

Civil Works Appropriations |

$3,000 |

$57,000 |

$14,768,000 |

$558,000 |

$207,000 |

$15,593,000 |

Source: CRS correspondence with Army Corps of Engineers Budget Office, 2012.

Department of Defense (Military) 45

Military Personnel

The Military Personnel accounts fund military pay and allowances, permanent change of station travel, retirement and health benefit accruals, uniforms, and other personnel costs. For the hurricane response efforts, funds have been used primarily to pay per diem to DOD personnel evacuated from affected areas, for the pay and allowances of activated Guard and Reserve personnel supporting the hurricane relief effort, and for increased housing allowances to compensate for housing rate increases in hurricane-affected areas. Military personnel funds obligated by the Alabama, Florida, Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi National Guard are detailed in Table 10. Data on the obligation of other Military Personnel funds, by state, were not readily available.

Operations and Maintenance

The Operations and Maintenance (O&M) accounts fund training and operation costs, pay for civilians, maintenance service contracts, fuel, supplies, repair parts, and other expenses. For the hurricane response efforts, funds have been used primarily to repair facilities, establish alternate operating sites for displaced military organizations, repair and replace equipment, remove debris, clean up hazardous waste, repair utilities, evacuate DOD personnel from affected areas, and support the operations of activated Army and Air National Guard units. O&M funds obligated by the Alabama, Florida, Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi National Guard are detailed in Table 10. Data on the obligation of other O&M funds, by state, were not readily available.

Procurement

The Procurement accounts generally fund the acquisition of aircraft, ships, combat vehicles, satellites, weapons, ammunition, and other capital equipment. For the hurricane response efforts, $2.85 billion was appropriated, of which $2.5 billion was used primarily to pay for extraordinary shipbuilding and ship repair costs, including not only damage to ships under construction and replacement of equipment and materials, but also additional overhead and labor costs resulting from schedule delays due to the hurricane damage to shipyards, primarily Avondale in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Ingalls in Pascagoula, Mississippi.46 These funds also included $140 million to improve the infrastructure at damaged shipyards.47 Budget authority, obligations, and outlays for procurement, allocated by state for Alabama, Florida, Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi are detailed in Table 10.

Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation

The Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E) accounts fund modernization efforts by way of basic and applied research, creation of technology-demonstration devices, developing prototypes, and other related costs. For the hurricane response efforts, funds have been used to replace damaged test equipment and repair damaged test facilities. Data allocating RDT&E funds by state were not readily available.

Military Construction (MILCON) and Family Housing

The MILCON accounts fund the acquisition, construction, installation, and equipment of temporary or permanent public works, military installations, facilities, and real property. The Family Housing Construction accounts fund costs associated with the construction of military family housing (including acquisition, replacement, addition, expansion, extension, and alteration), while the Family Housing O&M accounts fund expenses such as debt payment, leasing, minor construction, principal and interest charges, and insurance premiums on military family housing. For the hurricane response efforts, $1.4 billion was appropriated to finance the planning, design, and construction of military facilities and infrastructure that were damaged or destroyed by hurricane winds and water. Of this, $918 million was dedicated to military operations and training facilities, while an additional $460 million was appropriated for family housing construction and family housing O&M to rebuild destroyed, damaged, or new housing units and a housing office. Budget authority for MILCON and family housing construction allocated to the states of Alabama, Florida, Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi is detailed in Table 10. Of the $1.4 billion appropriated, $1.2 billion could be allocated to the five specified states, while $167 million was devoted to planning and design activities not associated with specific locations.

Management Funds

This category includes the Defense Working Capital Fund, the National Defense Sealift Fund, and a commissary fund. For the hurricane response efforts, these funds have been used primarily to rebuild and repair damaged commissaries, replace commissary inventories, and cover transportation and contingency costs of the Defense Logistics Agency. Data allocating these funds by state were not readily available.

Other Department of Defense Programs

This category includes the Defense Health Program (DHP) and the Office of the Inspector General (OIG). The DHP title funds medical and dental care to current and retired members of the Armed Forces, their family members, and other eligible beneficiaries. For the hurricane response efforts, these funds have been used primarily to pay for costs associated with displaced beneficiaries seeking care from private-sector providers rather than at military health care facilities, to pay the health care costs of activated Guard and Reserve personnel, and to replace medical supplies and equipment. Data allocating DHP funds by state were not readily available. Of the $589,000 appropriated for the OIG, $263,000 was provided to replace and repair damaged equipment in the Inspector General's office in Slidell, LA, and to cover relocation costs.

|

Name of Program |

Alabama |

Florida |

Louisiana |

Mississippi |

Texas |

Total |

|

Military Personnel (National Guard only)a |

$7,192 |

$4,091 |

$126,982 |

$27,123 |

$15,974 |

$181,361 |

|

Operations and Maintenance (National Guard only)b |

$1,407 |

$1,759 |

$89,538 |

$112,721 |

$12,440 |

$217,866 |

|

Procurement: Budget Authorityc |

$60,048 |

— |

$770,647 |

$1,698,581 |

— |

$2,529,277 |

|

Obligations |

$60,007 |

— |

$770,546 |

$1,698,193 |

— |

$2,528,746 |

|

Outlays |

$54,996 |

— |

$697,584 |

$1,567,619 |