Counting Regulations: An Overview of Rulemaking, Types of Federal Regulations, and Pages in the Federal Register

Federal rulemaking is an important mechanism through which the federal government implements policy. Federal agencies issue regulations pursuant to statutory authority granted by Congress. Therefore, Congress may have an interest in performing oversight of those regulations, and measuring federal regulatory activity can be one way for Congress to conduct that oversight. The number of federal rules issued annually and the total number of pages in the Federal Register are often referred to as measures of the total federal regulatory burden.

Certain methods of quantifying regulatory activity, however, may provide an imperfect portrayal of the total federal rulemaking burden. For example, the number of final rules published each year is generally in the range of 3,000-4,500, according to the Office of the Federal Register. Some of those rules have a large effect on the economy, and others have a significant legal and/or policy effect, even if the direct economic effects of the regulation are minimal. On the other hand, many federal rules are routine in nature and impose minimal regulatory burden, if any. In addition, rules that are deregulatory in nature and those that repeal existing rules are still defined as “rules” under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA, 5 U.S.C. §§551 et seq.) and are therefore generally included in counts of total regulatory activity, even though they do not impose a new net regulatory burden.

The Federal Register provides documentation of the government’s regulatory and other actions, and some scholars, commentators, and public officials have used the total number of Federal Register pages and documents each year as a measure for the total amount of regulatory activity. Because the Federal Register has been in print since the 1930s, these measures can be useful for cross-time comparisons. However, the total number of Federal Register pages may not be an accurate way to measure regulatory activity for several reasons. In addition to publishing proposed and final rules in the Federal Register, agencies publish other items that may be related to regulations, such as notices of public meetings and extensions of comment periods. The Federal Register also contains many other items related to non-regulatory activities, including presidential documents, notices, and corrections. In 2018, approximately 25% of the total pages in the Federal Register were in the “Rules and Regulations” section—the section in which final rules are published—although many of these pages are agencies’ responses to comments received and discussion of the basis for each regulation rather than actual regulatory text to be codified in the Code of Federal Regulations. Additionally, while the number of pages in the Federal Register has generally increased over time, the number of final rule documents published has generally decreased, indicating that there may be other factors involved that these metrics do not capture.

This report serves to inform Congress’s understanding of federal rulemaking by analyzing different ways to measure and assess trends in federal rulemaking activity. The report provides data on and analysis of the total number of rules issued each year, as well as information on other types of rules, such as “major” rules, “significant” rules, and “economically significant” rules. These categories have been created by various statutes and executive orders containing requirements that may be triggered if a regulation falls into one of the categories. When available, data are provided on each type of rule. Finally, the report provides data on the number of pages and documents in the Federal Register each year and analyzes the content of the Federal Register.

Counting Regulations: An Overview of Rulemaking, Types of Federal Regulations, and Pages in the Federal Register

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Brief Overview of Federal Rulemaking

- Statutory Requirements

- Executive Branch Requirements and Guidance

- Deregulatory Efforts in the Trump Administration

- Number of Final Rules Published in Recent Years

- "Major" Rules

- OIRA Review of "Significant" Rules

- OIRA Review of "Economically Significant" Rules

- Timelines for OIRA Review

- Rules Issued Without Notice and Comment Under "Good Cause"

- "Interim Final" Rules

- "Direct Final" Rules

- Number of Pages and Documents in the Federal Register

- The Federal Register Act

- Content of the Federal Register

Figures

- Figure 1. Number of Final Rule Documents Published in the Federal Register, 1976-2018

- Figure 2. Number of "Major" Final Rules, 1997-2018

- Figure 3. Total Number of "Economically Significant" and Non-"Economically Significant" Reviews at OIRA, 1994-2018

- Figure 4. Average Number of Days for OIRA Reviews, 1994-2018

- Figure 5. Total Pages Published Annually in the Federal Register, 1936-2018

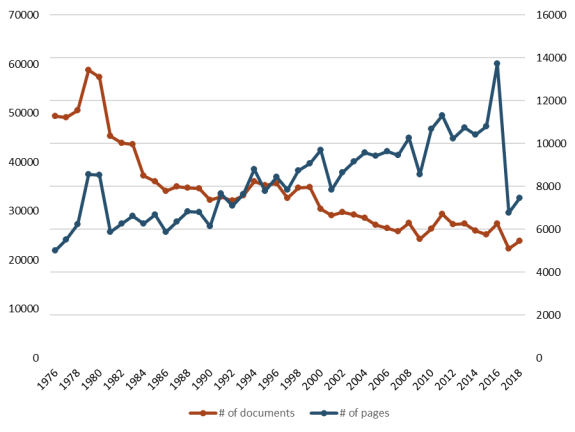

- Figure 6. Number of Pages and Documents of Proposed and Final Rules Published Annually in the Federal Register, 1976-2018

Tables

- Table 1. Total Number of Reviews at OIRA, 1994-2018

- Table A-1. Final Rule Documents Published in the Federal Register, 1976-2018

- Table A-2. Number of "Major" Final Rules Published, 1997-2018

- Table A-3. Total Number of "Economically Significant" and Non-"Economically Significant" Reviews at OIRA, 1994-2018

- Table A-4. Average Number of Days for "Economically Significant" and Non-"Economically Significant" Reviews, 1994-2018

- Table A-5. Total Number of Pages Published Annually in the Federal Register, 1936-2018

- Table A-6. Annual Content of the Federal Register: Number of Pages and Number of Proposed and Final Rule Documents, 1976-2018

Appendixes

Summary

Federal rulemaking is an important mechanism through which the federal government implements policy. Federal agencies issue regulations pursuant to statutory authority granted by Congress. Therefore, Congress may have an interest in performing oversight of those regulations, and measuring federal regulatory activity can be one way for Congress to conduct that oversight. The number of federal rules issued annually and the total number of pages in the Federal Register are often referred to as measures of the total federal regulatory burden.

Certain methods of quantifying regulatory activity, however, may provide an imperfect portrayal of the total federal rulemaking burden. For example, the number of final rules published each year is generally in the range of 3,000-4,500, according to the Office of the Federal Register. Some of those rules have a large effect on the economy, and others have a significant legal and/or policy effect, even if the direct economic effects of the regulation are minimal. On the other hand, many federal rules are routine in nature and impose minimal regulatory burden, if any. In addition, rules that are deregulatory in nature and those that repeal existing rules are still defined as "rules" under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA, 5 U.S.C. §§551 et seq.) and are therefore generally included in counts of total regulatory activity, even though they do not impose a new net regulatory burden.

The Federal Register provides documentation of the government's regulatory and other actions, and some scholars, commentators, and public officials have used the total number of Federal Register pages and documents each year as a measure for the total amount of regulatory activity. Because the Federal Register has been in print since the 1930s, these measures can be useful for cross-time comparisons. However, the total number of Federal Register pages may not be an accurate way to measure regulatory activity for several reasons. In addition to publishing proposed and final rules in the Federal Register, agencies publish other items that may be related to regulations, such as notices of public meetings and extensions of comment periods. The Federal Register also contains many other items related to non-regulatory activities, including presidential documents, notices, and corrections. In 2018, approximately 25% of the total pages in the Federal Register were in the "Rules and Regulations" section—the section in which final rules are published—although many of these pages are agencies' responses to comments received and discussion of the basis for each regulation rather than actual regulatory text to be codified in the Code of Federal Regulations. Additionally, while the number of pages in the Federal Register has generally increased over time, the number of final rule documents published has generally decreased, indicating that there may be other factors involved that these metrics do not capture.

This report serves to inform Congress's understanding of federal rulemaking by analyzing different ways to measure and assess trends in federal rulemaking activity. The report provides data on and analysis of the total number of rules issued each year, as well as information on other types of rules, such as "major" rules, "significant" rules, and "economically significant" rules. These categories have been created by various statutes and executive orders containing requirements that may be triggered if a regulation falls into one of the categories. When available, data are provided on each type of rule. Finally, the report provides data on the number of pages and documents in the Federal Register each year and analyzes the content of the Federal Register.

Introduction

Federal rulemaking is an important mechanism through which the federal government implements policy. Federal agencies issue regulations pursuant to statutory authority granted by Congress.1 Therefore, Congress may have an interest in performing oversight of those regulations, and measuring federal regulatory activity can be one way for Congress to conduct that oversight. The number of federal rules issued annually and the total number of pages in the Federal Register are often referred to as measures of the total federal regulatory burden.

Certain methods of quantifying regulatory activity, however, may provide an imperfect portrayal of the total federal rulemaking burden. For example, the number of final rules published each year is generally in the range of 3,000-4,500, according to the Office of the Federal Register. While some of those rules may have substantial economic, legal, or policy effects, many of them are routine in nature and impose minimal regulatory burden, if any.

This report serves to inform Congress's understanding of federal rulemaking by analyzing different ways to measure federal rulemaking activity. The report begins with a brief overview of how agencies issue rules, identifying the most significant statutory requirements, executive orders, and guidance documents that comprise the rulemaking process and briefly discussing recent deregulatory efforts. The report then provides data on and analysis of the total number of rules issued each year, as well as information on other types of rules, such as "major" rules, "significant" rules, and "economically significant" rules.2 These categories have been created by various statutes and executive orders containing requirements that may be triggered if a regulation falls into one of the categories. For example, if a rule is designated "economically significant" under Executive Order (E.O.) 12866, the issuing agency is generally required to perform a cost-benefit analysis and submit the rule for review to the Office of Management and Budget's (OMB's) Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA).3 When available, data are provided on each type of rule. When data in the report are presented in a graph, a corresponding table containing the same data can be found in the Appendix. Finally, the report presents data on the number of pages and documents in the Federal Register each year and analyzes the content of the Federal Register.

Brief Overview of Federal Rulemaking

When Congress enacts legislation, it frequently delegates rulemaking authority to federal agencies. Regulations issued by agencies are often the means through which specific requirements are then established. Regulations must be issued pursuant to statutory authority, and the process under which agencies issue regulations is governed by numerous statutory requirements and executive orders.4 In addition, OMB has issued guidance to agencies detailing how some of those requirements should be met.5 This section of the report briefly describes the significant statutory and executive requirements and guidance documents that comprise the rulemaking process.

Statutory Requirements

The most significant statute governing the rulemaking process is the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946 (APA).6 The APA established standards for the issuance of rules using formal rulemaking and informal rulemaking procedures.7 Informal rulemaking, also known as "notice and comment" rulemaking or "Section 553" rulemaking, is the most common type of rulemaking.

The APA defines a rule as "the whole or part of an agency statement of general or particular applicability and future effect designed to implement, interpret, or prescribe law or policy."8 The APA defines rulemaking as "the agency process for formulating, amending, or repealing a rule," which means that agencies must undertake a regulatory action whenever they are issuing a new rule, changing an existing rule, or eliminating a rule.9

When issuing rules under the APA, agencies are generally required to publish a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) in the Federal Register, take comments on the NPRM, publish a final rule in the Federal Register, and provide for at least a 30-day waiting period before the rule can become effective.10 The APA specifically authorizes any federal agency to dispense with its requirements for notice and comment if the agency for good cause finds that the use of traditional procedures would be "impracticable, unnecessary, or contrary to the public interest."11 The APA also provides a good cause exception for the 30-day waiting period between the publication of a final rule and its effective date.12

While the APA's notice and comment procedures comprise the general structure of the rulemaking process, a number of other statutory requirements have been added to the APA's requirements in the decades since enactment of the APA.

- The Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA), originally enacted in 1980, established a process under which agencies have to consider the paperwork burden associated with regulatory and other actions.13 Under the PRA, agencies generally must receive approval from OIRA for information collections from 10 or more nonfederal "persons."14

- The Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA), also originally enacted in 1980, requires regulatory flexibility analyses for proposed and final rules that will have a "significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities" (SEISNSE).15 Other provisions of the RFA require that certain agencies convene advocacy review panels for rules that may have a SEISNSE to solicit feedback from affected entities and that agencies reexamine rules with a SEISNSE to determine whether any changes to or repeal of the rules may be necessary.16

- Title II of the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act (UMRA) of 1995 added requirements for agencies (other than independent regulatory agencies) to analyze costs resulting from regulations containing federal mandates upon state, local, and tribal governments and the private sector.17 The analysis requirement in UMRA is triggered when a rule "may result in the expenditure by State, local, and tribal governments, in the aggregate, or by the private sector, of $100,000,000 or more (adjusted annually for inflation) in any 1 year."18

- The Congressional Review Act (CRA), enacted in 1996, established a mechanism through which Congress could overturn federal regulations by enacting of a joint resolution of disapproval.19 The CRA also requires that "major" rules (e.g., those that have a $100 million effect on the economy) have a delayed effective date of at least 60 days, and that agencies submit their rules to both houses of Congress and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) before the rules can take effect. Since it was enacted, the CRA has been used 17 times to overturn a rule: once during the George W. Bush Administration and 16 times during the Trump Administration in the 115th Congress.20

When issuing a rule, agencies generally address the rule's compliance with these statutory requirements in the preamble of the final rule, which generally constitutes a significant portion of the pages in each rulemaking document published in the Federal Register.

Executive Branch Requirements and Guidance

In addition to the statutory requirements Congress has enacted, Presidents have also issued executive orders and OMB has issued guidance regarding additional procedures that agencies must generally follow:

- E.O. 12866, issued by President William Clinton in 1993, calls for OIRA to review "significant" regulatory actions at both the proposed and final rule stage.21 The order also requires agencies to assess potential costs and benefits for "significant" rules, and, for those deemed as "economically significant" regulatory actions, agencies are required to perform a cost-benefit analysis and assess the costs and benefits of "reasonably feasible alternatives" to the planned rule.22 Furthermore, under E.O. 12866, agencies generally must "propose or adopt a regulation only upon a reasoned determination that the benefits" of the rule "justify its costs."23 E.O. 12866's requirements for OIRA review and cost-benefit analysis do not apply to independent regulatory agencies.

- To provide guidance to agencies on what to include and consider in their cost-benefit analyses of rules, OMB issued OMB Circular A-4, a document that describes "best practices" for agencies' regulatory impact analyses.24

- President Barack Obama issued several executive orders on rulemaking, and his Administration issued a number of guidance documents for agencies on how best to issue rules. Most significantly, E.O. 13563 reaffirmed many of the principles of E.O. 12866 and instructed agencies to conduct a retrospective review of their regulations in order to identify and take action to modify or repeal rules that they deem to be "outmoded, ineffective, insufficient, or excessively burdensome."25 Following the issuance of E.O. 13563, President Obama issued E.O. 13579, requesting that independent regulatory agencies also participate in the retrospective reviews.26

Deregulatory Efforts in the Trump Administration

President Donald Trump emphasized, during his campaign and while in office, that removing existing regulations and limiting new regulations would be a priority in his Administration. On January 30, 2017—10 days after he was sworn into office—President Trump issued E.O. 13771.27 This executive order established a "one in, two out" policy requiring that for new "incremental costs" resulting from new regulations, equivalent costs associated with two existing regulations must be repealed.28 In guidance explaining its plan for implementation of the order, OMB specified that this policy would apply only to newly added regulatory actions—including regulations and guidance documents—defined as significant under E.O. 12866.29 Furthermore, deregulatory actions could include the repeal or revision of a wide range of agency actions, regulations, guidance documents, recordkeeping and reporting requirements, and others.30

E.O. 13771 also established a "regulatory cost allowance," to be determined by the director of OMB, that places a cap on the total incremental costs of regulations allowed for a given fiscal year.31 For the remainder of FY2017, FY2018, and FY2019, OMB instructed agencies to meet a net-zero or reduction in regulatory costs.32

Difficulties in Quantifying Deregulation

Scholars and commentators have discussed various accounting methods for counting deregulatory actions.33 However, because agencies must adhere to normal notice and comment rulemaking procedures for deregulatory actions in addition to regulatory actions, isolating deregulatory actions from overall regulatory activity presents challenges.34 After FY2017 and FY2018, OIRA published statements detailing its completed regulatory and deregulatory actions. The Administration stated that in FY2017 agencies issued 67 deregulatory actions and three regulatory actions. In FY2018, it stated that agencies issued 176 and 14, respectively.35

Additionally, OIRA publishes the biannual Unified Agenda of Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions and annual Regulatory Plan, which provide an overview of current and planned regulatory actions in all federal regulatory agencies and include a searchable database of agency actions.36 Beginning in 2017, the Trump Administration added to the Unified Agenda a separate searchable data element to identify deregulatory actions, providing a more concrete means by which to potentially measure deregulation. Therefore, the Unified Agenda may present another approximate measure of regulatory trends during the Trump Administration.

The Trump Administration has also pursued rescission of regulations through the CRA. The 115th Congress overturned a total of 16 rules using the CRA. Prior to the 115th Congress, the CRA had not been used to overturn a rule since 2001.37

Number of Final Rules Published in Recent Years

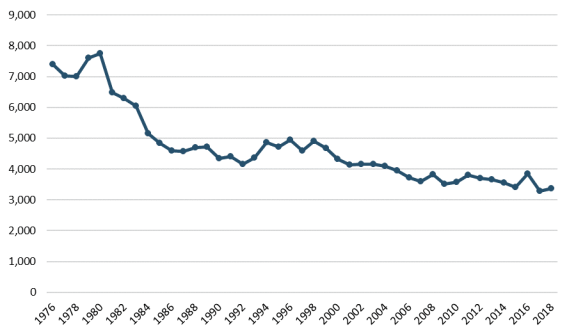

Figure 1 presents the approximate number of rules by year since 1976, the first year for which the Office of the Federal Register has data available. The number provided in the table for each year is the number of documents published in the final rules section of the Federal Register. Corresponding data for Figure 1 can be found in Table A-1 in the Appendix.

|

Figure 1. Number of Final Rule Documents Published in the Federal Register, 1976-2018 |

|

|

Source: Office of the Federal Register, Federal Register Documents Published 1976-2018, https://www.federalregister.gov/uploads/2019/04/stats2018Fedreg.pdf#page=4. |

Some context for understanding these numbers may be helpful, as the number of final rule documents is not a precise measurement of the total number of regulations or the total amount of federal regulatory activity.

Although the number of regulations issued each year is generally in the thousands, many of those regulations deal with routine matters. For example, a rule issued on May 23, 2019, by the U.S. Coast Guard provided notice that it would "enforce the annual safety zone for the PUSH Beaver County Fireworks, to provide for the safety of persons, vessels, and the marine environment on the navigable waters of the Ohio River during this event" from "8 p.m. to 10:30 p.m. on June 22, 2019."38 Because the change was considered a rule but only had a temporary effect, it did not make any changes to the Code of Federal Regulations (C.F.R.), which is the comprehensive codification of permanent rules and regulations. Captured under the definition of a rulemaking in the APA, such items are published in the "Rules and Regulations" section of the Federal Register.

Occasionally, a document will be published in the final rules section of the Federal Register that is not a rule itself but relates to one or more final rules. For example, on April 19, 2018, the Mine Safety and Health Administration published an announcement of public meetings in the final rules section of the Federal Register. That particular document was not a final rule, though it related to a previously issued rule. This rule would thus be counted twice in the numbers reflected in Figure 1, even though the document announcing the meeting did not constitute separate regulatory activity from the rule it related to, which had been published as a separate document.39 For this reason, the total count of the number of final rule documents likely includes some amount of double counting.

The number of regulations issued each year included deregulatory actions and minor amendments that agencies made to existing rules. As discussed earlier in this report, the APA defines rulemaking as "the agency process for formulating, amending, or repealing a rule." Therefore, agencies must undertake a rulemaking process when they seek to modify or eliminate a rule.40 Therefore, not all of the regulations counted in Figure 1 were necessarily new regulatory actions issued by agencies. Some of them could have been minor amendments, including technical corrections without substantive change, such as a 2018 Department of the Interior final rule that the agency stated repealed an amendment that had never been implemented and restored the original regulatory language.41 Alternatively, rule documents could include regulatory actions in which agencies removed regulations or attempted to make regulations less burdensome on the public. A December 14, 2018, final rule from the Department of Housing and Urban Development, classified as a significant regulatory action under E.O. 12866, "streamline[d] the inspection requirements for FHA single-family mortgage insurance by removing the regulations for the FHA Inspector Roster" in order to eliminate what the agency considered to be duplicative processes.42

"Major" Rules

As mentioned above, the CRA was enacted in 1996 and established procedures for congressional review of agency regulations. Under the CRA, each federal agency is required to send its covered final rules to GAO and to both houses of Congress before the rules can take effect.43 Section 804(2) of the CRA created a category of rules called "major" rules, which are those that the OIRA administrator determines has resulted in or is likely to result in

(A) an annual effect on the economy of $100,000,000 or more;

(B) a major increase in costs or prices for consumers, individual industries, Federal, State, or local government agencies, or geographic regions; or

(C) significant adverse effects on competition, employment, investment, productivity, innovation, or on the ability of United States-based enterprises to compete with foreign-based enterprises in domestic and export markets. The term does not include any rule promulgated under the Telecommunications Act of 1996 and the amendments made by that Act.44

The CRA contains two requirements for major rules. First, agencies are generally required to delay the effective dates of "major" rules until 60 days after the rule is submitted to Congress or published in the Federal Register, whichever is later.45 Second, the Comptroller General must provide a report on each major rule to the appropriate congressional committees of jurisdiction within 15 days of when a rule is submitted or published.46 The report must include a summary of the agency's compliance with various rulemaking requirements (such as regulatory impact analyses that agencies may be required to perform while undergoing a rulemaking action). These reports are posted on GAO's website.47

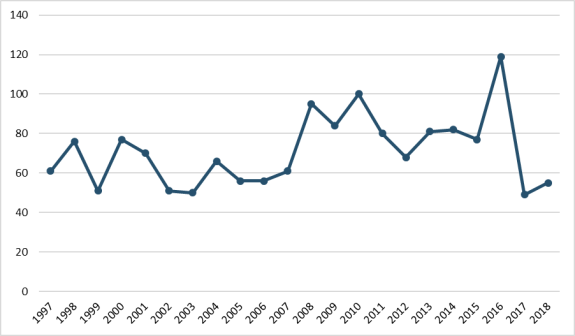

Figure 2 presents the total number of major rules published during each calendar year since 1997, as reported by GAO.48 Rules in the GAO database are those that have been submitted to GAO under the CRA (5 U.S.C. §801(a)(1)(A)(i)). Data begin in 1997 because the CRA was enacted in 1996, making 1997 the first full year for which data are available. Corresponding data for Figure 2 can be found in Table A-2 in the Appendix.

|

|

Source: Government Accountability Office's Database of Rules, https://www.gao.gov/legal/other-legal-work/congressional-review-act#database, accessed on July 1, 2019. Data provided are the numbers of major rules published each year in the Federal Register and submitted to GAO under Section 801 of the Congressional Review Act, which requires that agencies submit their rules to GAO and to both houses of Congress before they can take effect (5 U.S.C. §801(a)(1)(A)). |

One advantage of measuring the number of major rules each year, rather than measuring the total number of rules, is that this counting approach does not include rules that are relatively minor in effect, unlike the total number of rule documents presented above in Figure 1. In addition, this counting approach measures only rules and not other types of documents that are related to rules, such as notices of public meetings related to a rule.

A previous CRS report examined the 100 major rules published in 2010 and concluded that rules are determined to be "major" for a variety of reasons, not just due to compliance costs.49 For example, rules have been classified as major because they involved transfers of funds from one party to another, most commonly the transfer of federal funds through programs such as grants, Medicare or Medicaid funds, special pay for members of the military, and crop subsidy payments; because they prompted consumer spending or because they established fees for the reimbursement of particular federal functions (e.g., issuance of passports and oversight of the nuclear power industry); or because the rules result in cost savings for consumers and taxpayers.

The number of major rules, however, is only a partial portrayal of overall regulatory activity, as it captures only the small number of rules issued each year that have the greatest economic impact. It does not capture rules that are of lesser economic impact but still potentially have some significant legal or policy effects, nor does it capture the large number of administrative and routine rules that federal agencies issue each year.

OIRA Review of "Significant" Rules

The definition of a "significant" rule, found in E.O. 12866, is a rule that is likely to

(1) Have an annual effect on the economy of $100 million or more or adversely affect in a material way the economy, a sector of the economy, productivity, competition, jobs, the environment, public health or safety, or State, local, or tribal governments or communities;

(2) Create a serious inconsistency or otherwise interfere with an action taken or planned by another agency;

(3) Materially alter the budgetary impact of entitlements, grants, user fees, or loan programs or the rights and obligations of recipients thereof; or

(4) Raise novel legal or policy issues arising out of legal mandates, the President's priorities, or the principles set forth in this Executive order.50

Under E.O. 12866, most agencies are required to submit rules that OIRA determines to be "significant" to OIRA for centralized review.51 Upon submission, the agency must provide specific information to OIRA, including the text of the action; a detailed description of the need for the action; an explanation of how the action will meet that need; an assessment of the potential costs and benefits of the regulatory action; and an assessment of how the regulation "promotes the President's priorities and avoids undue interference with State, local, and tribal governments."52

While the number of major rules is accessible on GAO's Database of Rules, the number of significant rules issued each year is not readily available. No requirement currently exists for agencies or other entities to keep track of how many significant rules are issued each year. However, data are available for the number of reviews at OIRA each year, because OIRA logs on its website each rule it received for review under E.O. 12866.53 Notably, the number of "significant" rules reviewed each year would not be the same as the number of "significant" rules issued each year: For example, a rule could be reviewed at OIRA late in one calendar year but not actually issued (i.e., published in the Federal Register) until the next calendar year. In addition, because OIRA reviews proposed and final rules, the total number of reviews is much higher than final rules issued each year. However, the number of reviews at OIRA each year can still give some idea of annual regulatory activity.54

Table 1 lists the total number of reviews at OIRA annually from 1994 to 2018 by category, including prerules, proposed rules, interim final rules, final rules, and notices.55 The table refers to reviews, not just rules, because OIRA also reviews some agency guidance documents (which are generally included under "prerule" or "notice" categories). It should be noted that a single rule may be counted more than once in the table if it was reviewed at multiple stages during the same calendar year. Data begin in calendar year 1994 because E.O. 12866 was issued near the end of 1993.

|

Calendar Year |

Prerule Reviews |

Proposed Rule Reviews |

Interim Final Rule Reviews |

Final Rule Reviews |

Notice Reviews |

Total Reviews |

|

1994 |

16 |

317 |

68 |

302 |

128 |

831 |

|

1995 |

8 |

225 |

64 |

270 |

53 |

620 |

|

1996 |

28 |

160 |

56 |

232 |

31 |

507 |

|

1997 |

20 |

196 |

64 |

174 |

51 |

505 |

|

1998 |

15 |

192 |

58 |

182 |

40 |

487 |

|

1999 |

19 |

247 |

71 |

214 |

36 |

587 |

|

2000 |

13 |

210 |

66 |

253 |

40 |

582 |

|

2001 |

9 |

274 |

95 |

285 |

37 |

700 |

|

2002 |

23 |

261 |

81 |

249 |

55 |

669 |

|

2003 |

23 |

232 |

92 |

309 |

59 |

715 |

|

2004 |

26 |

237 |

64 |

241 |

58 |

626 |

|

2005 |

18 |

221 |

66 |

247 |

59 |

611 |

|

2006 |

12 |

229 |

43 |

270 |

46 |

600 |

|

2007 |

22 |

248 |

44 |

250 |

25 |

589 |

|

2008 |

17 |

276 |

39 |

313 |

28 |

673 |

|

2009 |

28 |

214 |

67 |

237 |

49 |

595 |

|

2010 |

36 |

261 |

84 |

232 |

77 |

690 |

|

2011 |

24 |

317 |

76 |

262 |

61 |

740 |

|

2012 |

12 |

144 |

33 |

195 |

40 |

424 |

|

2013 |

11 |

177 |

33 |

160 |

37 |

418 |

|

2014 |

17 |

201 |

43 |

145 |

46 |

452 |

|

2015 |

8 |

178 |

29 |

165 |

35 |

415 |

|

2016 |

14 |

231 |

28 |

305 |

45 |

623 |

|

2017 |

13 |

84 |

12 |

104 |

24 |

237 |

|

2018 |

25 |

168 |

11 |

124 |

32 |

360 |

Source: Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs' website, https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eoCountsSearchInit?action=init; data were retrieved on July 1, 2019.

Note: The number of "significant" rules reviewed by OIRA in each year is not the same as the number of "significant" rules issued in each year. Significant rules are reviewed at OIRA pursuant to E.O. 12866, issued by President Clinton in September 1993. During the review process, OIRA examines the content of the rule; the cost-benefit analysis conducted by the agency, if any; and whether the rule is consistent with the President's priorities.

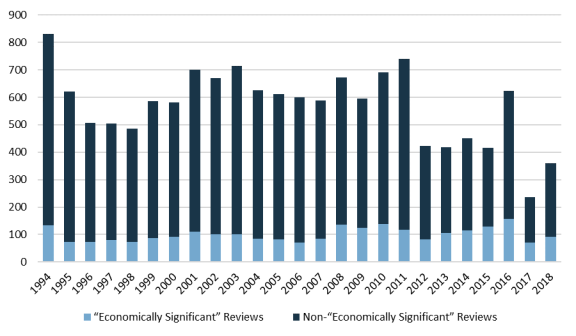

Data from the last column in this table can also be viewed in Figure 3 below, which groups the data into "economically significant" reviews and non-"economically significant" reviews.

OIRA Review of "Economically Significant" Rules

"Economically significant" rules are those rules that fall into category (1) of "significant" rules—that is, those rules that may

(1) Have an annual effect on the economy of $100 million or more or adversely affect in a material way the economy, a sector of the economy, productivity, competition, jobs, the environment, public health or safety, or State, local, or tribal governments or communities.

For rules that are considered "economically significant," agencies are required to complete a detailed cost-benefit analysis under Section 6(a)(3)(C) of E.O. 12866.56

Although the definition of economically significant rule is similar to the definition of major rule, OMB has suggested that the definition of major rule is a bit broader. Both definitions have a similar $100 million threshold, but the definition of major rule also includes other categories (see section entitled ""Major" Rules" above). As stated in OMB's guidance on implementing the Congressional Review Act,

the main difference is that some additional rules may be captured by the CRA definition that are not considered "economically significant" under E.O. 12866, notably those rules that would have a significant adverse effect on the ability of United States-based enterprises to compete with foreign-based enterprises in domestic and export markets.57

Despite these differences, however, the number of economically significant rules and major rules each year is likely almost identical. As was mentioned above for significant rules, however, no authoritative count exists for the number of economically significant rules issued each year. Rather, the data available are the counts of economically significant rules reviewed at OIRA.

Figure 3 lists the total number of economically significant reviews and non-economically-significant reviews by OIRA each calendar year from 1994 to 2018.58 Note that the totals portrayed in Figure 3 correspond to the final column above in Table 1. Corresponding data for Figure 3 can be found in Table A-3 in the Appendix.

|

Figure 3. Total Number of "Economically Significant" and Non-"Economically Significant" Reviews at OIRA, 1994-2018 |

|

|

Source: Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs' website, https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eoCountsSearchInit?action=init; data were retrieved on July 1, 2019. Note: The number of "economically significant" rules reviewed by OIRA in each year is not the same as the number of "economically significant" rules issued in each year. Rules are reviewed at OIRA pursuant to E.O. 12866, which was issued by President Clinton in September 1993. During the review process, OIRA examines the content of the rule; the cost-benefit analysis conducted by the agency, if any; and whether the rule is consistent with the President's priorities. |

As was noted above for the data in Table 1, in some cases, agencies may submit a single rule to OIRA for review more than one time in a year. Thus, a single rule could be counted more than once by appearing in different categories.

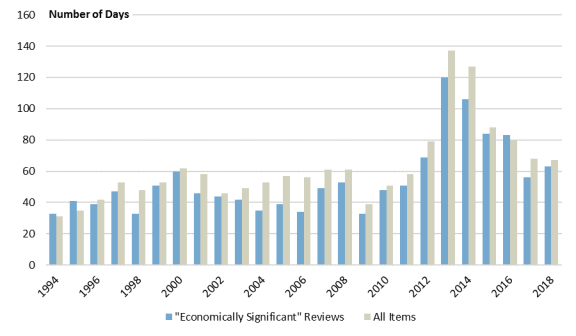

Timelines for OIRA Review

Under E.O. 12866, OIRA must meet certain timelines for its review of regulatory actions. For notices of inquiry, advanced notices of proposed rulemaking, or other "preliminary" regulatory actions (generally referred to in the database as "prerules"), OIRA must respond to the agency within 10 working days.59 For other regulatory actions such as proposed and final rules, OIRA has up to 90 calendar days for review.60 The order establishes a possible extension of the review process: Upon the written approval of the director of OMB, review can be extended by 30 days, or, alternatively, the agency head can request to extend the review process for an unspecified length of time.61 However, there are no consequences in the order if OIRA fails to meet the deadline for review.

Figure 4 lists the average review times for economically significant rules compared to the average for all its reviews from 1994 to 2018.62 Corresponding data for Figure 4 can be found in Table A-4 in the Appendix.

In general, since 1996, with the exception of 2016, the average time to review economically significant rules has been shorter than the average for all of its reviews. One possible explanation for this trend is that economically significant rules might generally be of higher salience and/or political importance, therefore warranting higher priority from OIRA. Another potential reason is that OIRA frequently engages in informal reviews, collaborating with the regulatory agency in advance of the official receipt of the rule. As a result, much of the work that goes into reviewing economically significant rules may take place in advance.63

|

Figure 4. Average Number of Days for OIRA Reviews, 1994-2018 |

|

|

Source: Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs' website; https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eoCountsSearchInit?action=init; data were retrieved on July 1, 2019. |

Rules Issued Without Notice and Comment Under "Good Cause"

As described above, under the APA, agencies are generally required to undergo certain procedures when issuing a rule. Those steps include the publication of a proposed rule in the Federal Register; the opportunity for interested persons to submit comments on the proposed rule; publication of a final rule that includes a "concise general statement" of the "basis and purpose" of the rule; and at least a 30-day waiting period before the rule can take effect.64

The APA allows for an exception to two of these requirements in limited circumstances if an agency has "good cause": the agency can issue a rule without notice and comment,65 or it can waive the 30-day waiting period before the rule can take effect.66 Proper use of the good cause exception must reflect that following the typical notice-and-comment procedures is "impracticable, unnecessary, or contrary to the public interest." The agency must give supporting reasons for invoking the good cause exception, and its invocation of good cause is subject to judicial review.67

As a matter of practice, agencies have developed two types of rulemaking that, while invoking the good cause exception, still allow for public input. Those two types of rules are discussed below.

"Interim Final" Rules

One use of the good cause exception allows agencies to issue "interim final" rules.68 When issuing an interim final rule, an agency invokes good cause, issues a rule, and then holds a post-promulgation comment period. If the agency is persuaded by any of the comments and so chooses, the rule can be amended in light of those comments.

This category of rule is also sometimes referred to as "interim rule" or "final rule, request for comment" in the Federal Register or by other similar terms. For example, the Fish and Wildlife Service published an "interim rule" on April 3, 2019, citing "unforeseen time constraints" as the rationale for invoking the good cause exception. The rule, which established regulations governing migratory bird subsistence harvest regulations in Alaska for the 2019 season, became effective the same day it was issued, but the service accepted comments until May 3, 2019.69

Available sources of data on rulemaking cited throughout this report do not contain a means for tracking agencies' use of good cause. This lack of data and inconsistent terminology makes it difficult, if not impossible, to track the use of interim final rules over time.

"Direct Final" Rules

Another potential use of the good cause exception allows agencies to engage in "direct final" rulemaking.70 "Direct final" rulemaking is used when an agency deems a rule to be routine or noncontroversial but still allows for the public to comment on a rule. Under "direct final" rulemaking, an agency will issue a final rule without prior notice and comment and then generally establish a time period during which the agency is open to receiving comments. The rule may take effect unless at least one adverse comment is received by the agency, in which case the agency will withdraw the rule and proceed with the normal notice and comment procedures. If no adverse comments are received, the rule will become effective. For example, a January 26, 2018, direct final rule issued by the Food and Drug Administration that revised regulations relating to time and duties of inspection requirements received "significant adverse comment" and was withdrawn on May 7, 2018. It was reissued as a final rule on April 2, 2019, including discussion of comments received, and became effective May 2, 2019.71

Number of Pages and Documents in the Federal Register

Since the enactment of the APA in 1946, agencies have been required to publish their proposed and final rules in the Federal Register.72 Agencies also publish other items related to regulations in the Federal Register, such as notices of meetings and the extension of comment periods, as well as many other items related to non-regulatory governmental activities. Because the Federal Register provides documentation of the government's regulatory and other actions, some scholars, commentators, and public officials have used the total number of Federal Register pages each year, which has increased substantially since its creation, as an approximate measure for the total amount of regulatory activity.73 The number of pages in the Federal Register, however, may not be an accurate measure for regulatory activity or regulatory burden for several reasons. This section discusses the history and content of the Federal Register and why it may not provide an accurate measure of regulatory activity.

The Federal Register Act

The Federal Register Act created the Federal Register in 1935 in response to the increasing number of administrative actions, laws, and regulations associated with the New Deal.74 During the New Deal, the role of federal agencies changed substantially—as one scholar noted, the federal government was entering new realms of public policy as a result of laws passed under the New Deal, such as agriculture, assistance for the aged and disadvantaged, housing and home ownership, and banking and securities.75 Many statutes that Congress passed granted rulemaking and other authorities to these new federal agencies. To create a centralized mechanism for documenting the increasing number of rules and administrative actions, and to provide a means for public access to government information more generally, Congress created the Federal Register. Since the 1930s, the Federal Register has been the vehicle for notifying the public of the federal government's actions.

Content of the Federal Register

As noted above, the number of pages in the Federal Register may be only a rough approximation of regulatory activity each year for several reasons. First, the section of the Federal Register devoted to publishing final rules is relatively small, because the Federal Register documents other non-regulatory activities as well. For example, in 2018, approximately 25% of the total pages were in the "Rules and Regulations" section, which is where final rules are published. The other portions of the Federal Register are used for such items as presidential documents, proposed rules, notices, and corrections. Other than the proposed rules, documents published in these additional sections may have little to do with federal regulations. Over 1,000 pages each year are blank pages or skips, which are designed to leave room for other materials and to maintain the integrity of the individual sections.76

Second, while the Federal Register provides a compilation of governmental activity that occurs each year, including new regulations, many of the final rules are amending rules that have been previously issued and therefore may not accurately be considered to be new rules. Similarly, as mentioned above, if an agency eliminates an already existing rule, this is considered a "rulemaking" action under the APA and would be published in the rules and regulations section of the Federal Register, even if it is a deregulatory action.

Third, when agencies publish proposed and final rules in the Federal Register, they include a preamble along with the text of the rule. The preamble often includes such information as statements of the statutory authority for the rule; information and history which the agency deems to be relevant; a discussion of the comments received during the comment period; an explanation of the agency's final decision; and in some cases, information about certain analyses that may have been required during the rulemaking process. It is possible, therefore, that the actual regulatory text provided in a rule could be relatively small compared to the size of the entire rulemaking document in the Federal Register. For example, a rule issued on April 16, 2018, by the Department of Health and Human Services pursuant to the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act and the 21st Century Cures Act, which modified Medicare Part C and D regulations, was 318 pages in total.77 Of the 318 pages, 282 pages comprised the preamble and 36 pages actually amended the Code of Federal Regulations. Much of the preamble discussed the comments received following the NPRM, as well as estimates of costs and benefits, associated data, and justifications of the agency's decisions while crafting the rule.

The number of pages in the Federal Register may also not be an accurate reflection of the amount of regulatory burden that stems from a rule. For example, a short rule could impose a large burden on a large number of regulated entities. On the other hand, a lengthy rule could contain less burdensome requirements but greater detail and only apply to a small number of entities. Because the preamble to the rule contains detailed information about the rule itself and the agency's response to the comments it received, the number of pages of a particular rule in the Federal Register could be related to other factors such as a large number of comments received or an in-depth cost-benefit analysis completed by an agency.

Figure 5 documents the change in the number of pages in the Federal Register over time. Corresponding data for Figure 5 can be found in Table A-5 in the Appendix. As the data show, the number of pages has increased since publication of the Federal Register began. After a decades-long increasing trend, the number of pages reached a peak in 1980 at 87,012 pages; decreased to 47,418 pages in 1986; then began to increase again. After being approximately between 65,000 and 85,000 pages for the past two decades, the number of pages reached an all-time high of 97,069 in 2016 before falling in 2017—the first year of the Trump Administration—to 61,950.

|

Figure 5. Total Pages Published Annually in the Federal Register, 1936-2018 |

|

|

Source: Office of the Federal Register, Federal Register Statistics, "Federal Register Pages Published 1936-2018," at https://www.federalregister.gov/uploads/2019/04/stats2018Fedreg.pdf. |

Figure 6 provides a more rulemaking-specific examination of the total page count provided in Figure 5 by providing the number of pages in the two rulemaking sections in the Federal Register. In addition, Figure 6 provides data on the number of proposed and final rulemaking documents in the Federal Register. Corresponding data for Figure 6 can be found in Table A-6. Data for Figure 6 begin in 1976 because the Office of the Federal Register's statistics resources begin counting documents by section in 1976.78

The number of documents published in the proposed rule and final rule sections of the Federal Register can be useful for cross-year comparisons. However, as mentioned above, not all of the documents in each of these sections are rules, so these data may not provide a precise indication of how many rules are issued each year or of the total regulatory burden each year. In addition, other types of documents may be included in the proposed and final rules sections of the Federal Register, as mentioned above. For example, on May 18, 2018, in the final rules section, the Transportation Security Administration issued a two-page notice that it was "reopening the comment period for the interim final rule … that established the Alien Flight Student Program."79 Because this action was related to a regulation, the document was published in the final rules section, but the document itself is not a regulation. Finally, as previously mentioned in this report, under the APA's definition of rulemaking, an amendment or repeal of a rule is considered a rule.80 Therefore, some of the pages and documents counted below could be reducing the burden associated with a previously issued rule by amending or repealing the rule.

|

Figure 6. Number of Pages and Documents of Proposed and Final Rules Published Annually in the Federal Register, 1976-2018 |

|

|

Source: Office of the Federal Register, Federal Register Statistics, "Federal Register Pages Published 1936-2018," https://www.federalregister.gov/uploads/2019/04/stats2018Fedreg.pdf. |

The general trends for the number of pages and the number of documents appear to be divergent during much of the time for which data are available: The number of pages has generally gone up, while the number of rulemaking documents has gone down, with some exceptions.81 That these two methods of measuring regulatory content in the Federal Register appear to be contradicting one another arguably reflects the fact that such measures are best viewed with caution and not necessarily as an accurate measure of overall regulatory activity.

Appendix. Data and Tables

|

Year |

Final Rule Documents Published in the Federal Register |

|

1976 |

7,401 |

|

1977 |

7,031 |

|

1978 |

7,001 |

|

1979 |

7,611 |

|

1980 |

7,745 |

|

1981 |

6,481 |

|

1982 |

6,288 |

|

1983 |

6,049 |

|

1984 |

5,154 |

|

1985 |

4,843 |

|

1986 |

4,589 |

|

1987 |

4,581 |

|

1988 |

4,697 |

|

1989 |

4,714 |

|

1990 |

4,334 |

|

1991 |

4,416 |

|

1992 |

4,155 |

|

1993 |

4,369 |

|

1994 |

4,867 |

|

1995 |

4,713 |

|

1996 |

4,937 |

|

1997 |

4,584 |

|

1998 |

4,899 |

|

1999 |

4,684 |

|

2000 |

4,313 |

|

2001 |

4,132 |

|

2002 |

4,167 |

|

2003 |

4,148 |

|

2004 |

4,101 |

|

2005 |

3,943 |

|

2006 |

3,718 |

|

2007 |

3,595 |

|

2008 |

3,830 |

|

2009 |

3,503 |

|

2010 |

3,573 |

|

2011 |

3,807 |

|

2012 |

3,708 |

|

2013 |

3,659 |

|

2014 |

3,554 |

|

2015 |

3,410 |

|

2016 |

3,853 |

|

2017 |

3,281 |

|

2018 |

3,368 |

Source: Office of the Federal Register, Federal Register Documents Published 1976-2018, https://www.federalregister.gov/uploads/2019/04/stats2018Fedreg.pdf#page=4.

|

Year |

Number of "Major" Final Rules |

|

1997 |

61 |

|

1998 |

76 |

|

1999 |

51 |

|

2000 |

77 |

|

2001 |

70 |

|

2002 |

51 |

|

2003 |

50 |

|

2004 |

66 |

|

2005 |

56 |

|

2006 |

56 |

|

2007 |

61 |

|

2008 |

95 |

|

2009 |

84 |

|

2010 |

100 |

|

2011 |

80 |

|

2012 |

68 |

|

2013 |

81 |

|

2014 |

82 |

|

2015 |

77 |

|

2016 |

119 |

|

2017 |

49 |

|

2018 |

55 |

Source: Government Accountability Office's Database of Rules, https://www.gao.gov/legal/other-legal-work/congressional-review-act#database, accessed on July 1, 2019. Data provided are the numbers of major rules published each year in the Federal Register and submitted to GAO under Section 801 of the Congressional Review Act, which requires that agencies submit their rules to GAO and to both houses of Congress before they can take effect (5 U.S.C. §§801-808).

Table A-3. Total Number of "Economically Significant" and Non-"Economically Significant" Reviews at OIRA, 1994-2018

|

Year |

"Economically Significant" Reviews |

Non-"Economically Significant" Reviews |

Total Reviews |

|

1994 |

134 |

697 |

831 |

|

1995 |

74 |

546 |

620 |

|

1996 |

74 |

433 |

507 |

|

1997 |

81 |

424 |

505 |

|

1998 |

73 |

414 |

487 |

|

1999 |

86 |

501 |

587 |

|

2000 |

92 |

490 |

582 |

|

2001 |

111 |

589 |

700 |

|

2002 |

100 |

569 |

669 |

|

2003 |

101 |

614 |

715 |

|

2004 |

85 |

541 |

626 |

|

2005 |

82 |

529 |

611 |

|

2006 |

71 |

529 |

600 |

|

2007 |

85 |

504 |

589 |

|

2008 |

135 |

538 |

673 |

|

2009 |

125 |

470 |

595 |

|

2010 |

138 |

552 |

690 |

|

2011 |

117 |

623 |

740 |

|

2012 |

83 |

341 |

424 |

|

2013 |

105 |

313 |

418 |

|

2014 |

114 |

338 |

452 |

|

2015 |

130 |

285 |

415 |

|

2016 |

156 |

467 |

623 |

|

2017 |

70 |

167 |

237 |

|

2018 |

91 |

269 |

360 |

Source: Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs' website, https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eoCountsSearchInit?action=init; data were retrieved on July 1, 2019.

Notes: The number of economically significant rules reviewed by OIRA in each year is not the same as the number of economically significant rules issued in each year. Rules are reviewed at OIRA pursuant to E.O. 12866, issued by President Clinton in September 1993. During the review process, OIRA examines the content of the rule, the cost-benefit analysis conducted by the agency, and whether the rule is consistent with the President's priorities.

Table A-4. Average Number of Days for "Economically Significant" and Non-"Economically Significant" Reviews, 1994-2018

|

Year |

Average Number of Days for "Economically Significant" Reviews |

Average Number of Days for Non-"Economically Significant" Reviews |

Average Number of Days for Review of All Items |

|

1994 |

33 |

30 |

31 |

|

1995 |

41 |

35 |

35 |

|

1996 |

39 |

42 |

42 |

|

1997 |

47 |

54 |

53 |

|

1998 |

33 |

50 |

48 |

|

1999 |

51 |

53 |

53 |

|

2000 |

60 |

62 |

62 |

|

2001 |

46 |

60 |

58 |

|

2002 |

44 |

46 |

46 |

|

2003 |

42 |

50 |

49 |

|

2004 |

35 |

55 |

53 |

|

2005 |

39 |

59 |

57 |

|

2006 |

34 |

59 |

56 |

|

2007 |

49 |

64 |

61 |

|

2008 |

53 |

63 |

61 |

|

2009 |

33 |

40 |

39 |

|

2010 |

48 |

51 |

51 |

|

2011 |

51 |

60 |

58 |

|

2012 |

69 |

81 |

79 |

|

2013 |

120 |

143 |

137 |

|

2014 |

106 |

134 |

127 |

|

2015 |

84 |

90 |

88 |

|

2016 |

83 |

79 |

80 |

|

2017 |

56 |

74 |

68 |

|

2018 |

63 |

68 |

67 |

Source: Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs' website, https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eoCountsSearchInit?action=init; data were retrieved on July 1, 2019.

|

Year |

Number of Pages |

|

1936 |

2,620 |

|

1937 |

3,450 |

|

1938 |

3,194 |

|

1939 |

5,007 |

|

1940 |

5,307 |

|

1941 |

6,877 |

|

1942 |

11,134 |

|

1943 |

17,553 |

|

1944 |

15,194 |

|

1945 |

15,508 |

|

1946 |

14,736 |

|

1947 |

8,902 |

|

1948 |

9,608 |

|

1949 |

7,952 |

|

1950 |

9,562 |

|

1951 |

13,175 |

|

1952 |

11,896 |

|

1953 |

8,912 |

|

1954 |

9,910 |

|

1955 |

10,196 |

|

1956 |

10,528 |

|

1957 |

11,156 |

|

1958 |

10,579 |

|

1959 |

11,116 |

|

1960 |

14,479 |

|

1961 |

12,792 |

|

1962 |

13,226 |

|

1963 |

14,842 |

|

1964 |

19,304 |

|

1965 |

17,206 |

|

1966 |

16,850 |

|

1967 |

21,088 |

|

1968 |

20,072 |

|

1969 |

20,466 |

|

1970 |

20,036 |

|

1971 |

25,447 |

|

1972 |

28,924 |

|

1973 |

35,592 |

|

1974 |

45,422 |

|

1975 |

60,221 |

|

1976 |

57,072 |

|

1977 |

65,603 |

|

1978 |

61,261 |

|

1979 |

77,498 |

|

1980 |

87,012 |

|

1981 |

63,554 |

|

1982 |

58,494 |

|

1983 |

57,704 |

|

1984 |

50,998 |

|

1985 |

53,480 |

|

1986 |

47,418 |

|

1987 |

49,654 |

|

1988 |

53,376 |

|

1989 |

53,842 |

|

1990 |

53,620 |

|

1991 |

67,716 |

|

1992 |

62,928 |

|

1993 |

69,688 |

|

1994 |

68,108 |

|

1995 |

67,518 |

|

1996 |

69,368 |

|

1997 |

68,530 |

|

1998 |

72,356 |

|

1999 |

73,880 |

|

2000 |

83,294 |

|

2001 |

67,702 |

|

2002 |

80,332 |

|

2003 |

75,798 |

|

2004 |

78,852 |

|

2005 |

77,777 |

|

2006 |

78,724 |

|

2007 |

74,408 |

|

2008 |

80,700 |

|

2009 |

69,643 |

|

2010 |

82,480 |

|

2011 |

82,415 |

|

2012 |

80,050 |

|

2013 |

80,462 |

|

2014 |

78,796 |

|

2015 |

81,402 |

|

2016 |

97,069 |

|

2017 |

61,950 |

|

2018 |

64,582 |

Source: Office of the Federal Register, Federal Register Statistics, "Federal Register Pages Published 1936-2018," https://www.federalregister.gov/uploads/2019/04/stats2018Fedreg.pdf.

Table A-6. Annual Content of the Federal Register: Number of Pages and Number of Proposed and Final Rule Documents, 1976-2018

|

Number of Pages Published in the Federal Register |

Number of Documents Published in the Federal Register |

|||

|

Year |

Proposed Rules |

Final Rules |

Proposed Rules |

Final Rules |

|

1976 |

9,325 |

12,589 |

3,875 |

7,401 |

|

1977 |

9,620 |

14,572 |

4,188 |

7,031 |

|

1978 |

11,885 |

15,452 |

4,550 |

7,001 |

|

1979 |

18,091 |

19,366 |

5,824 |

7,611 |

|

1980 |

16,276 |

21,092 |

5,347 |

7,745 |

|

1981 |

10,433 |

15,300 |

3,862 |

6,481 |

|

1982 |

12,130 |

15,222 |

3,729 |

6,288 |

|

1983 |

12,772 |

16,196 |

3,907 |

6,049 |

|

1984 |

11,972 |

15,473 |

3,350 |

5,154 |

|

1985 |

13,772 |

15,460 |

3,381 |

4,843 |

|

1986 |

11,816 |

13,904 |

3,185 |

4,589 |

|

1987 |

14,181 |

13,625 |

3,423 |

4,581 |

|

1988 |

13,883 |

16,042 |

3,240 |

4,697 |

|

1989 |

13,220 |

16,489 |

3,194 |

4,714 |

|

1990 |

12,692 |

14,179 |

3,041 |

4,334 |

|

1991 |

16,761 |

16,792 |

3,099 |

4,416 |

|

1992 |

15,156 |

15,921 |

3,170 |

4,155 |

|

1993 |

15,410 |

18,016 |

3,207 |

4,369 |

|

1994 |

18,183 |

20,385 |

3,372 |

4,867 |

|

1995 |

15,982 |

18,047 |

3,339 |

4,713 |

|

1996 |

15,369 |

21,622 |

3,208 |

4,937 |

|

1997 |

15,309 |

18,984 |

2,881 |

4,584 |

|

1998 |

18,256 |

20,029 |

3,042 |

4,899 |

|

1999 |

19,447 |

20,201 |

3,281 |

4,684 |

|

2000 |

17,943 |

24,482 |

2,636 |

4,313 |

|

2001 |

14,666 |

19,643 |

2,512 |

4,132 |

|

2002 |

18,640 |

19,233 |

2,638 |

4,167 |

|

2003 |

17,357 |

22,670 |

2,538 |

4,148 |

|

2004 |

19,332 |

22,546 |

2,430 |

4,101 |

|

2005 |

18,260 |

23,041 |

2,257 |

3,943 |

|

2006 |

19,794 |

22,347 |

2,346 |

3,718 |

|

2007 |

18,611 |

22,771 |

2,308 |

3,595 |

|

2008 |

18,648 |

26,320 |

2,475 |

3,830 |

|

2009 |

16,681 |

20,782 |

2,044 |

3,503 |

|

2010 |

21,844 |

24,914 |

2,439 |

3,573 |

|

2011 |

23,193 |

26,274 |

2,898 |

3,807 |

|

2012 |

20,096 |

24,690 |

2,517 |

3,708 |

|

2013 |

20,619 |

26,417 |

2,594 |

3,659 |

|

2014 |

20,731 |

24,861 |

2,383 |

3,554 |

|

2015 |

22,588 |

24,694 |

2,342 |

3,410 |

|

2016 |

21,457 |

38,652 |

2,419 |

3,853 |

|

2017 |

10,892 |

18,727 |

1,834 |

3,281 |

|

2018 |

16,207 |

16,378 |

2,098 |

3,368 |

Source: Office of the Federal Register, Federal Register Statistics, "Federal Register Pages Published 1936-2018," https://www.federalregister.gov/uploads/2019/04/stats2018Fedreg.pdf.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Kiersten Rhodes, Research Intern, provided substantial assistance with an update of this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

The terms rule and regulation are used interchangeably in this report. |

| 2. |

Although there are various categories of federal rules discussed in this report, the categories are not mutually exclusive. A particular regulation could fit into more than one of the categories, or in some cases a regulation may not fit into any of the categories discussed here. |

| 3. |

E.O. 12866, "Regulatory Planning and Review," 58 Federal Register 51735, October 4, 1993. To view a copy of this order, see https://www.archives.gov/files/federal-register/executive-orders/pdf/12866.pdf. "Independent regulatory agencies" are excepted from this requirement; see discussion later in this report in section on "economically significant" rules. |

| 4. |

For an overview of the rulemaking process, see CRS Report RL32240, The Federal Rulemaking Process: An Overview, coordinated by Maeve P. Carey; and CRS In Focus IF10003, An Overview of Federal Regulations and the Rulemaking Process, by Maeve P. Carey. |

| 5. |

Many of these OMB guidance documents are discussed in CRS Report R41974, Cost-Benefit and Other Analysis Requirements in the Rulemaking Process, coordinated by Maeve P. Carey. |

| 6. |

P.L. 79-404; 5 U.S.C. §§551 et seq. |

| 7. |

When agencies engage in formal rulemaking, the agency must hold a trial-like hearing. Presently, formal rulemaking is a rarely used process, and its requirements are only triggered when Congress explicitly states that the rulemaking proceed "on the record." 5 U.S.C. §553(c); United States v. Florida East Coast Railway, 410 U.S. 224 (1973). |

| 8. |

5 U.S.C. §551(4). |

| 9. |

5 U.S.C. §551(5). |

| 10. |

5 U.S.C. §553. Certain rules are exempted from the requirements of Section 553, including rules involving "(1) a military or foreign affairs function of the United States; or (2) a matter relating to agency management or personnel or to public property, loans, grants, benefits, or contracts" (5 U.S.C. §553(a)). In addition, certain other rules are exempted from the notice and comment requirements, but are still required to publish a final rule in the Federal Register, including "interpretative rules, general statements of policy, or rules of agency organization, procedure, or practice" (5 U.S.C. §553(b)(3)(A)). |

| 11. |

5 U.S.C. §553(b)(B). A December 2012 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report found that agencies did not publish an NPRM in about 35% of "major" rules (those with the biggest economic effect) and about 44% of non-"major" rules published from 2003 through 2010. The most common reason agencies cited was the APA's "good cause" exception. Agencies also published rules without an NPRM for other reasons, such as cases in which the statute instructed issuance of a final rule without a prior NPRM. |

| 12. |

5 U.S.C. §553(d)(3). For further information on the APA's good cause exception, see CRS Report R44356, The Good Cause Exception to Notice and Comment Rulemaking: Judicial Review of Agency Action, by Jared P. Cole. |

| 13. |

44 U.S.C. §§3501-3520. |

| 14. |

Person, as defined in the PRA, includes individuals, partnerships, associations, corporations, groups, and any element of a state or local government. |

| 15. |

5 U.S.C. §§601-612. The RFA does not apply to rules issued without an NPRM. For more information about requirements under the RFA, see CRS Report RL34355, The Regulatory Flexibility Act: Implementation Issues and Proposed Reforms, coordinated by Maeve P. Carey. |

| 16. |

5 U.S.C. §§609-610. |

| 17. |

2 U.S.C. §§1532-1538. Like the RFA, UMRA does not require an analysis for rules issued without an NPRM. For more information about UMRA, see CRS Report R40957, Unfunded Mandates Reform Act: History, Impact, and Issues, by Robert Jay Dilger. |

| 18. |

2 U.S.C. §1532(a). |

| 19. |

5 U.S.C. §§801-808. The CRA provides for expedited consideration of such a resolution in the Senate. For an overview of the CRA, see CRS Report R43992, The Congressional Review Act (CRA): Frequently Asked Questions, by Maeve P. Carey and Christopher M. Davis; and CRS In Focus IF10023, The Congressional Review Act (CRA), by Maeve P. Carey and Christopher M. Davis. |

| 20. |

For a list of the rules that have been overturned using the CRA, see https://www.gao.gov/legal/other-legal-work/congressional-review-act#faqs. |

| 21. |

E.O. 12866, "Regulatory Planning and Review," 58 Federal Register 51735, October 4, 1993. The executive order defines "significant" regulatory actions as those rules that may "(1) Have an annual effect on the economy of $100 million or more or adversely affect in a material way the economy, a sector of the economy, productivity, competition, jobs, the environment, public health or safety, or State, local, or tribal governments or communities; (2) Create a serious inconsistency or otherwise interfere with an action taken or planned by another agency; (3) Materially alter the budgetary impact of entitlements, grants, user fees, or loan programs or the rights and obligations of recipients thereof; or (4) Raise novel legal or policy issues arising out of legal mandates, the President's priorities, or the principles set forth in this Executive order" (§3(f)). Rules that fall into the first of these four categories are "economically significant" rules (§3(f)(1)). |

| 22. |

Section 6(a) of E.O. 12866. |

| 23. |

Section 1(b)(6) of E.O. 12866. E.O. 12866, like its predecessor orders that were issued by President Ronald Reagan (E.O. 12291 and E.O. 12498), does not apply the cost-benefit analysis or OIRA review to independent regulatory agencies such as the Federal Reserve Board and Securities and Exchange Commission. A complete list of the independent regulatory agencies that are exempted from the order is in the Paperwork Reduction Act at 44 U.S.C. §3502(5). |

| 24. |

The most recent version of OMB Circular A-4 was issued in September 2003 and can be found on the White House's website at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/circulars/A4/a-4.pdf. Circular A-4 has been used by OMB and agencies since it was issued in 2003. |

| 25. |

Section 6(a) of E.O. 13563, "Improving Regulation and Regulatory Review," 76 Federal Register 3821, January 18, 2011. For more information on additional Obama Administration regulatory reform initiatives, see https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/omb/international_regulatory_cooperation. |

| 26. |

For more information on the retrospective review process, see Joseph Aldy, Learning from Experience: An Assessment of the Retrospective Reviews of Agency Rules and the Evidence for Improving the Design and Implementation of Regulatory Policy, report written for the Administrative Conference of the United States, November 18, 2014, https://www.acus.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Aldy%2520Retro%2520Review%2520Draft%252011-17-2014.pdf. |

| 27. |

E.O. 13771, "Reducing Regulation and Controlling Regulatory Costs," 82 Federal Register 9339, January 30, 2017. |

| 28. |

Section 2(a) of E.O. 13771, "Reducing Regulation and Controlling Regulatory Costs," 82 Federal Register 9339, January 30, 2017. |

| 29. |

Memorandum M-17-21 from Dominic J. Mancini, Acting Administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs to Regulatory Policy Officers at Executive Departments and Agencies and Managing and Executive Directors of Certain Agencies and Commissions, "Guidance Implementing E.O. 13771, Titled 'Reducing Regulation and Controlling Regulatory Costs,'" April 5, 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/memoranda/2017/M-17-21.pdf. |

| 30. |

Mancini, "Guidance Implementing E.O. 13771," p. 4. |

| 31. |

E.O. 13771, "Reducing Regulation and Controlling Regulatory Costs," §3(d), 82 Federal Register 9339, January 30, 2017. |

| 32. |

E.O. 13771, §3(d). See also OMB's report on "FY2018 Regulatory Cost Allowances" at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/memoranda/2017/FY%202018%20Regulatory%20Cost%20Allowances.pdf; and "Regulatory Reform: Regulatory Budget for Fiscal Year 2019" at https://www.reginfo.gov/public/pdf/eo13771/EO_13771_Regulatory_Budget_for_Fiscal_Year_2019.pdf. |

| 33. |

For a discussion of some of the methodological challenges in measuring deregulation, see Bridget C. E. Dooling, "Trump Administration Picks up the Regulatory Pace in its Second Year," Regulatory Studies Center, August 1, 2018, pp. 3-6, https://regulatorystudies.columbian.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs1866/f/downloads/Dooling_Trump%27sFirst18Months.pdf. |

| 34. |

In addition, measuring the effects of these deregulatory actions is also highly challenging. Some scholars, commentators, and critics have argued that the deregulatory policies of the Trump Administration have led primarily to slowing the flow of new regulations, citing that many rescinded regulations were recently issued and thus may not have had a significant impact on the economy or administrative operations; that many rescinded regulations were not economically significant; that the decrease in added regulations can be attributed to freezing rules in the pipeline, not rescinding rules that had been in effect already; or that President Trump has tended to follow trends of previous Administrations by halting the production of their predecessors' regulations. See, for example, Connor Raso, "How Has Trump's Deregulatory Order Worked in Practice?," Brookings Institution, September 6, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/research/how-has-trumps-deregulatory-order-worked-in-practice/; and Cary Coglianese, "Let's Be Real About Trump's First Year in Regulation," The Regulatory Review, January 29, 2018, https://www.theregreview.org/2018/01/29/lets-be-real-trumps-first-year-regulation/. |

| 35. |

See OIRA, "Regulatory Reform: Completed Actions Fiscal Year 2017," https://www.reginfo.gov/public/pdf/eo13771/FINAL_BU_20171207.pdf; and OIRA, "Regulatory Reform Report: Completed Actions for Fiscal Year 2018," https://www.reginfo.gov/public/pdf/eo13771/EO_13771_Completed_Actions_for_Fiscal_Year_2018.pdf. |

| 36. |