Job Creation in the Manufacturing Revival

The health of the U.S. manufacturing sector is of ongoing interest to Congress. Numerous bills aimed at promoting manufacturing are introduced in each Congress, often with the stated goal of creating jobs. Implicit in many of these bills is the assumption that the manufacturing sector is uniquely able to provide well-paid employment for workers who have not pursued education beyond high school.

Definitional issues have made it more challenging to assess the state of the manufacturing sector. Lines between manufacturing and other economic sectors are increasingly blurred. Many workers in fields such as industrial design and information technology perform work closely related to manufacturing, but are usually counted as employees in other sectors unless their workplace is within a manufacturing facility. Temporary workers in factories typically are employed by third parties and not treated as manufacturing workers in government data. Further, technology, apparel, and footwear firms that design and market manufactured goods but contract out production to separately owned factories are not considered to be manufacturers, even though many of their activities may be identical to those performed within manufacturing firms.

This report addresses the outlook for employment in the manufacturing sector. Its main conclusions are the following:

U.S. manufacturing output has risen approximately 24% since the most recent low point in 2009. However, most of that expansion occurred prior to the end of 2014. Manufacturing output was relatively flat in 2015 and 2016, and after rising modestly in 2017 and 2018 has again flattened out. Manufacturers have added approximately half a million jobs since the start of 2017, but manufacturing employment continues to decline as a share of total employment.

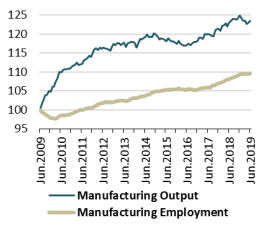

Wages for production and nonsupervisory workers in manufacturing, on average, have declined relative to wages of nonsupervisory workers in other industries. Although workers in some manufacturing industries earn relatively high wages, the assertion that manufacturing as a whole provides better-paid jobs than the rest of the economy is increasingly difficult to support.

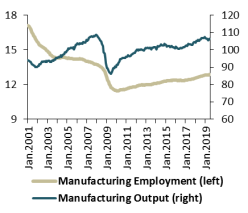

Employment in millions, output indexed 2012=100

/

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current

Employment Survey, and Federal Reserve Board,

Industrial Production Index. Seasonally adjusted.

Manufacturers spend more per work-hour for employee benefits than private employers in other industries, but the manufacturing benefit premium has diminished significantly in recent years.

A declining proportion of manufacturing workers is involved in physical production processes, while larger shares perform managerial and professional tasks. Many routine manufacturing tasks are now performed by contract workers, whose wages are lower than those of manufacturing firms’ employees in similar occupations. These changes are reflected in increasing skill requirements at manufacturing firms and diminished opportunities for workers without education beyond high school.

The average number of new manufacturing establishments opened each year since the end of the last recession remains much lower than in the period between 1977 and 2009. Unlike in the service sector, few jobs in manufacturing are provided by new establishments. Conversely, plant closings are responsible for only a small share of jobs lost. Change in manufacturing employment overwhelmingly occurs through hiring or job reductions at existing facilities.

Job Creation in the Manufacturing Revival

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Employment in the Manufacturing Sector

- The Changing Character of Manufacturing Work

- The Shrinking Wage Premium

- Manufacturing-Related Work in Other Sectors

- Embedded Services and Information Products

- Bundled Services and Information Products

- Factoryless Goods Production/Contract Manufacturing

- Employment Services Firms

- The Decline of the Large Factory

- Start-Ups and Shutdowns

- Policy Implications for Congress

Figures

- Figure 1. Employment and Output in Manufacturing

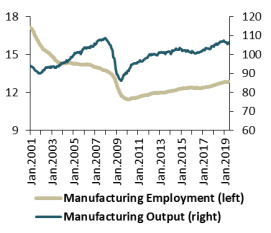

- Figure 2. Growth in Employment and Output Since Cyclical Trough

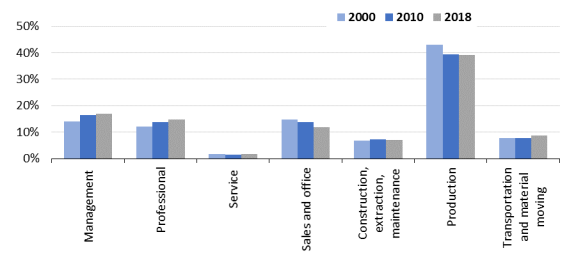

- Figure 3. Manufacturing Employment by Occupation

- Figure 4. Manufacturing Employment by Worker Education

- Figure 5. Manufacturing Employment by Gender

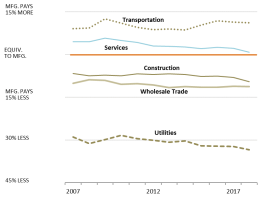

- Figure 6. Wages for Nonsupervisory Workers in Selected Industries

- Figure 7. Wages for All Workers in Selected Industries

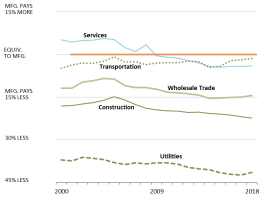

- Figure 8. Jobs Created by Establishment Openings

- Figure 9. Jobs Lost Due to Establishment Closings

Summary

The health of the U.S. manufacturing sector is of ongoing interest to Congress. Numerous bills aimed at promoting manufacturing are introduced in each Congress, often with the stated goal of creating jobs. Implicit in many of these bills is the assumption that the manufacturing sector is uniquely able to provide well-paid employment for workers who have not pursued education beyond high school.

Definitional issues have made it more challenging to assess the state of the manufacturing sector. Lines between manufacturing and other economic sectors are increasingly blurred. Many workers in fields such as industrial design and information technology perform work closely related to manufacturing, but are usually counted as employees in other sectors unless their workplace is within a manufacturing facility. Temporary workers in factories typically are employed by third parties and not treated as manufacturing workers in government data. Further, technology, apparel, and footwear firms that design and market manufactured goods but contract out production to separately owned factories are not considered to be manufacturers, even though many of their activities may be identical to those performed within manufacturing firms.

This report addresses the outlook for employment in the manufacturing sector. Its main conclusions are the following:

|

|

|||

|

||||

Introduction

U.S. manufacturing output has stalled since late 2018 after expanding at an annual rate exceeding 2% over the previous two years. Although industrial production is up 23% from its most recent cyclical low in June 2009, most of that growth occurred between 2009 and 2014. Employment in the manufacturing sector continues to increase at a slow pace, but accounts for a declining share of employment in the United States. Forecasts that forces such as higher labor costs in the emerging economies of Asia and heightened concern about supply-chain disruptions would bring a surge of factory production and manufacturing jobs in the United States have not been fulfilled.1

Changes in technology, business organization, and employment practices make it increasingly difficult to evaluate the state of the manufacturing sector. Government statistics attribute a growing share of manufacturing-related jobs and output to other sectors of the economy, notably information, professional and business services, and wholesale trade. Many workers in these sectors appear to be engaged in factory production, even as a large number of workers employed in the manufacturing sector perform tasks far removed from factory production. The total extent of output and employment related to manufacturing is therefore difficult to quantify. However, evidence suggests that even strong growth in manufacturing is likely to have a modest impact on overall job creation, particularly for workers with lower levels of education.

Employment in the Manufacturing Sector

Under current statistical practices, whether an activity is classified as manufacturing depends largely on where it is conducted. Government statistical agencies track most types of economic activity at the level of the establishment—that is, a single facility or business location—rather than at the level of a firm that may own multiple establishments or an enterprise that may own many firms. As a general rule, if an establishment is "primarily engaged" in transforming or assembling goods, then all output from that establishment is considered output of the manufacturing sector, and all workers (except those employed by outside contractors) are considered manufacturing workers.

At the start of the 21st century, 17.1 million Americans worked in manufacturing as defined in this way. This number declined during the recession that began in March 2001, in line with the historical pattern. In a departure from past patterns, however, manufacturing employment failed to recover after that recession ended in November 2001 (see Figure 1). By the time the most recent recession began, in December 2007, the number of manufacturing jobs in the United States had fallen to 13.7 million. Currently, 12.9 million workers are employed in the manufacturing sector.

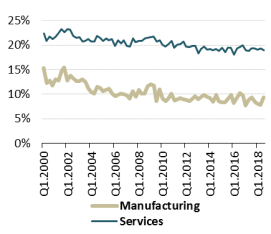

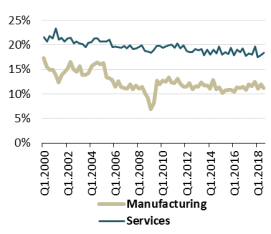

The output of U.S. manufacturers hit a cyclical bottom in June 2009. Since that time, a 24% increase in manufacturing output has been accompanied by only a 10% increase in manufacturing employment (see Figure 2). The low point in manufacturing employment was reached in February 2010. Since that time the manufacturing job count has risen 12%.2

There is no single cause of the long-term decline of manufacturing employment. A sharp increase in the bilateral U.S. trade deficit with China following that country's accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001 contributed importantly to manufacturing job loss in the first half of the last decade, but changes in the bilateral balance in goods trade since 2006 are not associated with changes in employment of factory workers in the United States.3 Cyclical forces aside, several distinct factors limit the prospects for job creation in the manufacturing sector, even if domestic production gains market share from imports.

- Some manufacturing industries, notably apparel and footwear, are tied to labor-intensive production methods that have proven difficult to automate. With labor costs accounting for a high share of value added in these industries, declining import barriers allowed imports from low-wage countries, particularly in East Asia, to displace domestic production. From 1.3 million workers in 1980, U.S. employment in apparel manufacturing has fallen to 108,000. While several efforts to automate production of t-shirts and athletic shoes are under way, these seem unlikely to significantly affect U.S. output and employment over the next few years.

- In other industries, technological improvements have enabled manufacturers to expand output without adding workers.4 Steelmaking offers such an example: the 82,800 people working in the industry in 2018 produced 14% more steel than nearly 399,000 workers did in 1980.5

- Secular shifts in demand have dimmed employment prospects in some industries, such as paper and tobacco manufacturing. Paper consumption, for example, was once closely associated with economic growth, but no longer; paper output has stabilized at a level about 20% lower than in the late 1990s, contributing to a 40% drop in industry employment over the same period.

- Ongoing technological change is likely to alter the manufacturing processes for certain products, with adverse consequences for factory employment. More widespread adoption of electric vehicles could reduce employment needs in the motor vehicle parts industry, because electric vehicles require significantly fewer parts than vehicles with internal combustion engines.6 The functionality of some types of electronic devices may be less dependent on content physically built into the devices, potentially changing the labor requirements for manufacturing.7

These changes are resulting in significant shifts in the composition of manufacturing employment. Food manufacturing, which two decades ago accounted for 1 in 11 manufacturing jobs, now accounts for 1 in 8; it is one of the few manufacturing sectors in which employment has grown since the start of the 21st century. Transportation equipment, fabricated metal products, food manufacturing, and plastics and rubber manufacturing have added workers since 2010, and account for larger shares of manufacturing employment. Apparel, textiles, printing, and computers and electronic products now account for substantially smaller shares of manufacturing employment than was formerly the case (see Table 1).

|

Industry |

2001 Share |

2010 Share |

2019 Share |

|

Transportation Equipment |

11.64% |

11.50% |

13.53% |

|

Food |

9.08% |

12.64% |

12.72% |

|

Fabricated Metal Products |

10.28% |

10.99% |

11.58% |

|

Machinery |

8.49% |

8.50% |

8.89% |

|

Computers and Electronic Products |

10.93% |

9.55% |

8.36% |

|

Chemicals |

5.71% |

6.92% |

6.63% |

|

Plastics and Rubber |

5.45% |

5.37% |

5.74% |

|

Misc. Durables Manufacturing |

4.25% |

4.95% |

4.79% |

|

Printing |

4.66% |

4.32% |

3.31% |

|

Nonmetallic Mineral Products |

3.25% |

3.25% |

3.27% |

|

Electrical Equipment |

3.41% |

3.09% |

3.15% |

|

Furniture |

3.96% |

3.14% |

3.08% |

|

Primary Metals |

3.55% |

3.04% |

2.99% |

|

Paper |

3.70% |

3.46% |

2.88% |

|

Apparel |

2.67% |

1.05% |

0.87% |

|

Textiles |

2.13% |

1.40% |

0.86% |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Employment Statistics for January of respective year.

Note: Not all manufacturing industries are included.

The Changing Character of Manufacturing Work

In the public mind, the word "factory" is associated with the concept of mass production, in which large numbers of workers perform repetitive tasks. While mass production is still an important aspect of manufacturing, routine production functions, from welding joints in truck bodies to removing plastic parts from a molding machine, have proven susceptible to automation. This has had important consequences for the nature of work in manufacturing establishments and for the skill requirements of manufacturing workers.

Goods production is no longer the principal occupation of workers in the manufacturing sector. Only two in five manufacturing employees are directly involved in making things. That proportion has fallen nearly 4 percentage points since 2000. Employment in other occupations within the manufacturing sector, notably office clerical work, has also declined (see Figure 3). As of 2018, 32% of all manufacturing workers held management and professional jobs.8 "Blue collar" occupations, such as production, transportation and material moving, maintenance and repair, construction, cleaning, food service, and protective service, account for two-thirds of employment in manufacturing firms but only about half the total wage bill.9

|

Figure 3. Manufacturing Employment by Occupation Percentage of manufacturing workforce |

|

|

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey, Table 17, http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat17.htm. |

In many industries within the manufacturing sector, the share of jobs with higher skill requirements is even more pronounced. Total employment in the U.S. computer and electronic product manufacturing industries has declined due to automation, sharp falls in demand for certain products once produced in the United States (notably television tubes and audio equipment), and changed scale economies that cause manufacturers to concentrate worldwide production in a small number of locations. Of the 1.04 million people employed in this industry in 2018, 29% were engaged in production occupations, for which a high school education may be sufficient and for which workers received median annual pay of $36,240. Some 21% of the industry's workers were in architecture and engineering occupations paying a median annual wage of $86,960, and another 13% were in computer and mathematical occupations with a median annual wage of $106,930; the latter two occupational categories require much higher education levels than production work. Similarly, some 32% of the workers in the pharmaceutical manufacturing industry are involved with production. Many of the rest have scientific skills associated with higher education levels.

The increasing demand for skills in manufacturing is most visible in the diminished use of "team assemblers"—essentially, line workers in factories and warehouses. In May 2018, employment in this occupation, which typically requires little training and no academic qualifications, was 1.3 million, down 15% since 2000. Some 997,580 team assemblers were counted as working in manufacturing in 2018, representing roughly 8% of manufacturing jobs. This type of job was once the core of manufacturing. Now, 23% of all team assemblers work for employment agencies, which furnish workers to other companies on an as-needed basis. Team assemblers working for employment agencies earned a median wage of $12.36 per hour, some 23% less than those employed directly by manufacturing companies.10

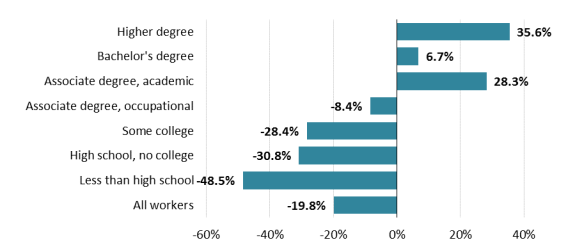

The changing occupational mix within the manufacturing sector is mirrored by changing educational requirements. In 2000, 53% of all workers in manufacturing had no education beyond high school. Between 2000 and 2018, that share dropped by 11 percentage points, even as the proportion with bachelor's or graduate degrees rose by 9 percentage points, to 31%. Despite the significant loss of manufacturing jobs between 2000 and 2018, the number of manufacturing workers with graduate degrees increased by approximately 357,000, or 36%. Employment of workers with associate degrees in academic fields rose 28%, or 183,000 jobs, over that period, while workers with associate degrees in occupational fields, which prepare students for immediate vocational entry, declined by 67,000 (Figure 4).11 Given that college-educated workers generally command significantly higher pay than high-school dropouts and high-school graduates, it is unlikely that manufacturers would willingly hire more-educated workers unless there were a payoff in terms of greater productivity.

|

Figure 4. Manufacturing Employment by Worker Education Percentage Change, 2000-2018 |

|

|

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey. |

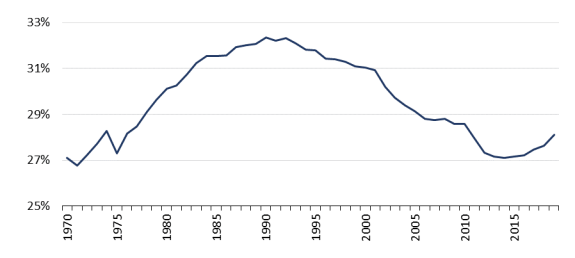

The female share of the manufacturing workforce has increased since reaching a low of 27.11% in 2014. Since then, manufacturers have added 331,000 female workers along with 423,000 male workers. The proportion of manufacturing workers who are female has fallen from 32% as recently as 1993 to 28% currently, having risen slightly since 2014 (see Figure 5). Women have long accounted for a large share of employment in some of the industries that have experienced the steepest drops in employment, notably apparel, textiles, and electrical manufacturing. The female workforce was significantly less educated than the male workforce in manufacturing: in 2000, only 41% of female manufacturing workers had any education beyond high school, compared with 61% of their male counterparts.

This gender gap in education has closed since 2000, due largely to the departure of less educated women from the manufacturing workforce. The number of female manufacturing workers with no education beyond high school fell 50% from 2000 to 2018. As a result, the number of years of schooling of female manufacturing workers is now similar to that of males in manufacturing. Some 32% of women workers in manufacturing in 2018 held four-year college degrees or higher degrees, almost identical to the proportion for men. Some 10% of female manufacturing workers had not completed high school; the corresponding share of male workers in manufacturing was around three percentage points less.

|

Figure 5. Manufacturing Employment by Gender Percentage of manufacturing workforce that is female |

|

|

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Employment Statistics. Note: Data are for January of each year and are not seasonally adjusted. |

The Shrinking Wage Premium

Policymakers traditionally have attached special importance to manufacturing because manufacturers appear to pay a wage premium, compared to employers in other industries. Based on pay, a 2012 U.S. Department of Commerce publication asserted, "manufacturing jobs are good jobs." According to that source, manufacturing jobs offered average hourly pay of $29.75 in 2010, compared to $27.47 for nonmanufacturing jobs. Including employer-provided benefits, the Commerce Department reported, manufacturing workers earned 17% more per hour than workers in other industries.12

Such comparisons, however, are not as straightforward as they may appear. At least some of the purported manufacturing wage premium exists because manufacturers employ far fewer young workers than industries with lower pay. In the lowest-paid sectors of the economy, a large share of the workforce—15% in leisure and hospitality, 7% in retailing—is under age 20, compared with only 1% of manufacturing workers.13 Also, large numbers of workers in those two lower-paying industries are employed part time; the average work week is around 26 hours in leisure and hospitality and 31 hours in retailing, versus 41 hours in manufacturing.14 Full-time workers in any industry are more likely to receive benefits than part-time workers.

Contrary to the popular perception, production and nonsupervisory workers in manufacturing, on average, earn significantly less per hour than nonsupervisory workers in industries that do not employ large numbers of teenagers, that have average workweeks of similar length, and that have similar levels of worker education. For example, nonsupervisory workers in manufacturing earned an average hourly wage of $21.54 in 2018, compared with $27.74 for nonsupervisory construction workers and $36.77 for nonsupervisory workers in the electric utility industry. Moreover, average wages for production and nonsupervisory workers in manufacturing have declined over time, compared to those in other industries, with the exceptions of retailing and transportation (see Figure 6). In 2000, for example, nonsupervisory workers in manufacturing earned 5.1% more, on an hourly basis, than nonsupervisory workers in the services sector; in 2017, they earned 2.4% less than services workers, on average.15

One criticism of this analysis is that the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) considers a smaller proportion of employees to be production and nonsupervisory workers in manufacturing than in other sectors of the economy, so that comparing the wages of this subset of workers may lead to misleading conclusions about relative pay in manufacturing.16 One alternative is to look at relative earnings of all workers rather than just nonsupervisory workers. These data, which are available only since 2007, show more modest relative declines in manufacturing wages than appear in the figures for production and nonsupervisory workers (see Figure 7). However, the wages of highly paid workers, including managers and executives, are included in these data, so the averages may not be reflective of the relative pay of factory-floor workers.

|

|

|

A recent econometric analysis17 draws on data from a different BLS survey to estimate that workers without college educations earn average hourly wages 7.8% higher in manufacturing than elsewhere in the private sector. It concludes that "there remains a manufacturing wage premium, but that it has substantially fallen since the 1980s."18 The study adjusts the data for gender, experience, education, race, ethnicity, and region of the country, so it provides an answer to the question, "Is an individual who works in manufacturing likely to earn a higher hourly wage than an individual with similar characteristics who works in another private-sector industry?" However, adjusting for individual characteristics may obscure broader trends in relative wages of manufacturing workers. For example, the share of manufacturing workers identifying themselves as "Black or African American" and "Hispanic or Latino" has been increasing. On average across all industries, black and Hispanic workers earn less than non-Hispanic white workers. Hence, it is arithmetically possible that a growing proportion of manufacturing workers earn a wage premium relative to what those individuals could earn in other industries, even as the wage premium for manufacturing workers overall has disappeared.19

Whether manufacturing pays higher wages than other sectors of the economy depends in part on the location and type of industry. In 2010, according to BLS, the average hourly wage for all workers in manufacturing was higher than the average for all private-sector workers in 29 of the 46 states for which data were available. By 2018, the average manufacturing wage exceeded the private-sector average in 23 of 46 states.20 The national average hourly wage for production workers in durable-goods manufacturing, including such industries as transportation equipment and computers and electronic products, $22.51 in 2018, is well above the $19.96 average in non-durables manufacturing, which includes such low-paying industries as food, textiles, and apparel.

Traditionally, manufacturing employers have tended to offer more generous employee benefits than those in other industries. This was due mainly to the comparatively large union presence in the manufacturing sector; in 2000, for example, employers of blue-collar union workers in manufacturing spent nearly twice as much per hour worked on benefits as employers of blue-collar non-union workers in manufacturing.21 The number of manufacturing workers represented by labor unions has fallen by more than half since 2000.22 While manufacturing employers, on average, still spend more on benefits than private-sector employers in general, the differential has diminished in recent years, according to BLS data (see Table 2).23

|

Year |

Manufacturing |

All Private Sector |

Manufacturing Premium |

|

2005 |

$10.44 |

$8.34 |

25.2% |

|

2010 |

$11.12 |

$9.75 |

14.1% |

|

2015 |

$13.06 |

$11.93 |

9.5% |

|

2018 |

$13.80 |

$12.72 |

8.5% |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employer Costs for Employee Compensation.

Note: Benefits include paid leave, supplemental pay, insurance, retirement and savings benefits, and legally required benefits. Data pertain to the first quarter of each calendar year.

On balance, modest job creation in manufacturing has not been accompanied by an improvement in the average position of manufacturing workers, relative to those in other sectors. Some manufacturing workers appear to have done well: the average hourly wage of workers in petroleum refining rose 47% between 2008 and 2018. On the other hand, average hourly wages in transportation equipment rose only 10% over that decade, and production workers in auto parts manufacturing had a lower average hourly wage in 2018 ($20.88) than in 2008 ($20.99).24 Although workers in some manufacturing industries earn relatively high wages, the assertion that the manufacturing sector as a whole provides better wages and benefits than the rest of the economy is increasingly difficult to defend. However, a considerable share of manufacturing-related work is performed in other sectors of the economy, some of which have much higher average wages than the manufacturing sector itself.

Manufacturing-Related Work in Other Sectors

Under current statistical practices, whether an activity is classified as manufacturing depends largely on where it is conducted. Government statistical agencies track most types of economic activity at the level of the establishment—that is, a single facility or business location—rather than at the level of a firm that may own multiple establishments or an enterprise that may own many firms. As a general rule, if an establishment is "primarily engaged" in transforming or assembling goods, then all output from that establishment is considered output of the manufacturing sector, and all workers (except those employed by outside contractors) are considered manufacturing workers.

Thus, if a firm locates its product design employees at a U.S. facility that is primarily engaged in producing goods, those designers will likely be counted as working in a manufacturing establishment, and their work will add to the total value added created in U.S. manufacturing. If, however, the product designers work at a separately located design center, they will probably be considered to work in an industrial design establishment, not a manufacturing establishment. In that case, they will be counted as industrial design workers, and their value added will be attributed to the professional, scientific, and technical services sector, not to the manufacturing sector.25 The same will be true if the product designers physically located at a manufacturing establishment are employed by a separate firm rather than by the manufacturer.

One might identify four separate groups of U.S. workers whose jobs are related to manufacturing:

- Production employees of manufacturing establishments: approximately 9.0 million workers in early 2019.

- Nonproduction employees of manufacturing establishments: approximately 3.8 million workers.

- Workers producing manufactured goods but employed by nonmanufacturing establishments: number unknown.

- Workers producing services and software used in manufacturing but employed by nonmanufacturing establishments: number unknown.

Data related to the first two groups are generally captured by government statistics depicting the manufacturing sector. Data related to the roles of workers in the last two groups are far more tenuous.

Embedded Services and Information Products

Historically, the value of a manufactured product has been presumed to come principally from physical transformation, involving such activities as stamping, rolling, molding, sewing, or distilling. More recently, however, a study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) stated,

Because of the growing servicification with manufacturing companies producing services and bundling them with goods, the lines between manufacturing and service sectors are becoming increasingly blurred.26

Drawing on employment as well as trade data, economists at OECD estimate that approximately 53% of the value of U.S. exports of manufactured goods in 2011 comprised services.27A recent study by McKinsey & Company, a consulting firm, estimated that software alone accounted for 10% of the content of a large car in 2018, and would reach 30% in 2030.28 It is likely that the value of software embedded in other types of manufactured goods, from factory machinery to consumer electronics, now accounts for a significant share of the products' value.

Available data make it difficult to trace the employment effects of this shift to incorporating greater services content into manufactured goods. For example, while 15% of all manufacturing wages are paid to computer or engineering workers,29 the number of software industry workers who do not work in manufacturing firms but who write code that is incorporated in manufactured goods cannot readily be determined. Similarly, the value of manufactured goods delivered from U.S. factories to customers, whether domestic or foreign, includes significant freight transportation costs, but the number of nonmanufacturing work-hours devoted to providing transportation services to manufacturers cannot easily be calculated.

Bundled Services and Information Products

Unlike embedded services and information products, bundled products may be offered for sale separately from the manufactured goods to which they relate. Anecdotal evidence suggests that a growing proportion of manufactured goods are sold in conjunction with after-sale services. For example, Boeing Corp., an aircraft manufacturer, recently set a goal of $50 billion of annual revenue from services such as supplying spare parts, modifying and repairing aircraft, training pilots, and monitoring aircraft systems during flights.30 Manufacturers may also offer customers information technology products, such as data concerning a customer's use of the product. Many manufacturers are reshaping themselves to be service and information providers, attracted by the prospect of continuing revenue streams from customers rather than one-time payments.31

It is possible that a manufacturer might demand a different price for a good sold as a stand-alone product than for the same good when bundled with a service or information contract. In such a case, the amount of the product's value to attribute to the manufacturing sector rather than the "other services" sector, which includes machinery and equipment repair and maintenance, may be arbitrary.32 Government data collectors may not be able to capture the value of the good separately from the value of the bundled services, and may not be able to distinguish the workers involved in the original production process from those providing related services.

Factoryless Goods Production/Contract Manufacturing

Factoryless goods producers are firms that design products to be manufactured and own the finished goods but do not engage directly in physical transformation. The transformation or assembly of the goods they sell is done by external suppliers, known as contract manufacturers, in the United States or abroad, although the factoryless goods producer may be closely involved in its contract manufacturers' operations. Examples might include a U.S.-based footwear company that engages other firms to produce the shoes it designs and markets,33 and a "fabless" semiconductor company that contracts with an unrelated "foundry" to manufacture its chips.

It is impossible to identify factoryless goods producers with certainty; responses to related questions on government surveys are confidential, and companies' annual reports filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission may not provide sufficient detail to determine whether they own manufacturing establishments.

Alphabet Inc., parent of Google Inc., appears to meet the definition. Alphabet generated 88% of its revenue in 2018 from delivering online advertising. The company also sells computers, telephones, and security systems to consumers; designs and oversees production of computer servers used in its data centers; and designs semiconductors used in computers and smartphones.34 In 2012 a company official referred to Google as "probably ... one of the largest hardware manufacturers in the world." However, according to Alphabet's 2018 annual financial report, "We rely on third parties to manufacture many of our assemblies and finished products," leaving the question of whether Alphabet owns and operates its own manufacturing facilities unanswered.35 It is unclear whether any Alphabet employees are categorized as manufacturing workers and whether any of the company's sales are registered as manufacturing output.

Similarly, Amazon.com, a retailer and provider of computer-related services, states in its annual financial report for 2018 that "we also manufacture and sell electronic devices." However, Amazon apparently does not operate manufacturing facilities, explaining that it "use[s] several contract manufacturers to provide manufacturing services for our products."36 Amazon stated in 2018 that it had begun making central processing units for its own servers, but it appears that the physical production of these chips is performed by a contract manufacturer, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., which is based in Taiwan but is listed on the New York Stock Exchange.37 Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. owns semiconductor manufacturing facilities in Camas, WA, as well as in other countries; the location where Amazon's CPUs are produced has not been disclosed.

According to a Census Bureau survey, at least 54,000 nonmanufacturing firms employing 3.4 million workers purchased contract manufacturing services in 2012.38 An analysis of the survey results in conjunction with information from the 2012 Economic Census revealed that factoryless manufacturers tended to have a large proportion of their workers employed in professional, scientific, and technical services, suggesting that factoryless manufacturers focus heavily on research and design activities. They reported spending more on research and development and owning more intellectual property, such as patents and copyrights, than other service firms.39 As this survey has been discontinued, more recent data are not available.

The definitional questions associated with factoryless goods producers have proven controversial. In 2010, U.S. statistical agencies proposed to categorize factoryless goods producers as manufacturers starting in 2017.40 This change would have increased both the number of individuals counted as manufacturing workers and the reported value added of the manufacturing sector.41 The proposal met with strong objections. In 2014, the Office of Management and Budget ordered the change postponed, citing the poor quality of statistical data about factoryless producers.42 As a result, a significant amount of manufacturing-like work and value added is not attributed to manufacturing in government statistics.

Employment Services Firms

Manufacturers make significant use of workers employed by temporary help agencies and other employment services firms in addition to their own employees. The overwhelming majority of employment service firms' employees who work in manufacturing are engaged on a temporary basis. According to estimates based on Bureau of Labor Statistics data, 916,847 people in typical manufacturing production occupations worked for employment services firms in May 2018. They typically earn $2-$4 less per hour than workers in the same occupation who are employed directly by manufacturers (Table 3).43 These workers are classified as employed in the professional and business services sector, not the manufacturing sector, in government data. If their pay were used in calculating average wages in manufacturing, manufacturing workers would earn less, relative to workers in other sectors, than indicated by BLS data.

It is likely that many nonproduction workers in manufacturing establishments are employed by employment services as well. This includes workers in office, maintenance, and food service occupations. The lack of comparable data makes it difficult to ascertain how the number of people working within manufacturing establishments as employees of employment services has changed over time. One recent study finds that the number of temporary-help workers in manufacturing came to 9.7% of the number of workers employed directly by manufacturers in 2015, up from 6.9% in 2005.44

|

Occupation |

Number of Workers |

Hourly Mean Wage |

Corresponding Mean Wage of Manufacturing Workers |

|

First-line supervisors of production and operating workers |

4,352 |

$28.60 |

$30.88 |

|

Assemblers and fabricators |

213,121 |

$14.08 |

$17.78 |

|

Food processing workers |

19,338 |

$12.75 |

$14.48 |

|

Metal and plastic workers |

80,818 |

$16.83 |

$19.72 |

|

Printing workers |

5,202 |

$14.89 |

$18.28 |

|

Textile, apparel, and furnishing workers |

9,877 |

$11.99 |

$14.28 |

|

Woodworkers |

4,148 |

$14.41 |

$16.02 |

|

Plant and system operators |

1,216 |

$27.33 |

$30.87 |

|

Other production occupations |

273,692 |

$14.29 |

$18.40 |

|

Hand laborers and material movers |

305,085 |

$13.02 |

$15.67 |

|

Total |

916,847 |

Source: CRS calculations based on Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment Statistics Query System, http://data.bls.gov/oes.

The Decline of the Large Factory

The stereotypical U.S. manufacturing plant has thousands of employees filling a cavernous factory hall. This stereotype is outdated. Of more than 291,000 manufacturing establishments45 counted by the Census Bureau in March 2016, only 886 employed more than 1,000 workers (see Table 4). This is up from the modern low of 795 in 2010, but remains far below the level of the 1990s. Those very large factories, the ones most prominent in public discussion of manufacturing, collectively employ 1.8 million workers, 16% of the manufacturing workforce and slightly more than 1% of the U.S. labor force.46

As the number of factories in all size classes declined, mean employment in U.S. manufacturing establishments fell from 46.3 workers in 1998 to 36.2 in 2010. Since then, the number of factories in all size classes above 100 employees has edged higher, and mean employment size has risen to 39.6 workers.

|

99 or fewer |

100-249 |

250-499 |

500-999 |

1,000 or more |

|

|

1998 |

330,956 |

22,499 |

7,968 |

3,322 |

1,504 |

|

2004 |

309,909 |

19,227 |

6,349 |

2,486 |

1,112 |

|

2010 |

277,148 |

15,428 |

4,764 |

1,847 |

795 |

|

2016 |

266,745 |

16,421 |

5,397 |

2,094 |

886 |

|

Change, 1998-2016 |

-19% |

-27% |

-32% |

-37% |

-41% |

Source: Census Bureau, County Business Patterns by Employment Size Class, various years.

The decline in the number of large factories was widespread across the manufacturing sector, with the exception of the food processing industry. Four industries—chemicals, computers and electronic products, machinery, and transportation equipment—accounted for more than half the decline in the number of factories with more than 1,000 workers between 1998 and 2010. More recently, however, the number of such large factories has increased in several industries, notably food, chemicals, and transportation equipment manufacturing,47 suggesting that existing plants have added workers as business conditions have improved. This is reflected in an increase in the proportion of manufacturing workers who are employed in large establishments since 2012, following many years of decline.

Start-Ups and Shutdowns

The employment dynamics of the factory sector differ importantly from those in the rest of the economy. In other economic sectors, notably services, business start-ups and shutdowns account for nearly one-fifth of job creation and job destruction. In manufacturing, by contrast, employment change appears to be driven largely by the expansion and contraction of existing firms, with entrepreneurship and failure playing lesser roles. This may be due to obvious financial factors: the large amounts of capital needed for manufacturing equipment may serve as an obstacle to opening a factory, and the highly specialized nature of manufacturing capital may make it difficult for owners to recover their investment if an establishment shuts down entirely rather than reducing the scope of its production activities.

The dynamics of employment change in manufacturing can be seen in two different government databases. The Bureau of Labor Statistics' Business Employment Dynamics database, which is based on firms' unemployment insurance filings, offers a quarterly estimate of gross employment gains attributable to the opening of new establishments and to the expansion of existing ones, and of the gross job losses attributable to the contraction or closure of establishments.48 In manufacturing, BLS finds, around 9% of gross job creation in recent years is attributable to new establishments, and more than 90% to the expansion of existing establishments. This is quite a different picture from that offered by the service sector, in which openings routinely account for about 19% of all new jobs (see Figure 8).

|

|

|

Similarly, while plant closings are frequently in the headlines, closings are responsible for 11% of the manufacturing jobs lost over the past decade. This represents a change from the early years of the 21st century, when plant closings routinely accounted for 15% or 16% of lost manufacturing jobs. Closure is far less likely to be the cause of job loss in the manufacturing sector than in the service sector, where 19% of job losses are due to establishments closing (see Figure 9).49

The other source of data on the connection between new factories and manufacturing job creation is the longitudinal business database maintained by the Census Bureau's Center for Economic Studies. This database covers some establishments (notably certain public sector employers) not included in the BLS database and links individual firms' records from year to year in an attempt to filter out spurious firm openings and closings.50 The Census database has different figures than the BLS database, but identifies similar trends, in particular that establishments open and close at far lower rates in the manufacturing sector than in other sectors of the economy.

The Census Bureau data make clear that the rate at which new business establishments of all sorts were created fell significantly during the 2007-2009 recession.51 As of 2016, the business creation rate had not recovered to prerecession levels. The data also show that 17,337 manufacturing establishments employing 245,019 workers opened their doors in the year to March 2016. This was the largest number of new plants since 2012, but half the level of the 1980s and early 1990s. The average manufacturing establishment that opened in the year to March 2016 provided 14 jobs during its first months. The number of jobs created in newly opened plants remained well below the number lost in the closure of existing plants.52

Policy Implications for Congress

In recent years, Congress has considered a large amount of legislation intended to strengthen the manufacturing sector. Bills introduced in the 116th Congress take diverse approaches, ranging from directing the Secretary of Energy to support initiatives that integrate digital technologies into production, energy efficiency improvement, and supply chains (S. 715/H.R. 1633, Smart Manufacturing Leadership Act) to providing financial and technical assistance to designated manufacturing communities (H.R. 2631, Make It In America Manufacturing Communities Act), to directing the President to appoint a Chief Manufacturing Officer (H.R. 2900, Chief Manufacturing Officer Act) to bills and amendments seeking to increase the use of U.S.-made steel or manufactured products in federally funded infrastructure projects.53

These proposals, and many others, are typically advanced with the stated goal of job creation, and often with the subsidiary goals of improving employment opportunities for less educated workers or reversing employment decline in communities particularly affected by the loss of manufacturing jobs. The available data suggest, however, that these goals may be difficult to achieve. In particular

• Increases in manufacturing activity are likely to translate into relatively modest gains in manufacturing employment due to firms' preference to use U.S. facilities for highly capital-intensive production. With the average manufacturing worker making use of $325,000 of fixed assets, even large investments are likely to lead to relatively little manufacturing employment, although they may create demand for workers in other sectors, such as construction or information services.

• The decline in energy costs due to the development of shale gas, strongly encouraged by federal policy, is having relatively modest effects on U.S. manufacturing employment. The three sectors that jointly account for about 65% of natural gas consumption in manufacturing—chemicals, petroleum refining, and primary metals—are the most capital-intensive industries within U.S. manufacturing. The chemical industry has added approximately 60,000 employees over the past five years, but employment has changed little in refining and has declined in primary metals over that period. To the extent that expansion in these industries creates jobs, these are more likely to be in supplier industries, such as construction, than in their own facilities.

• Changes in methods, products, and materials may transform some manufacturing industries over the next few years. Some of these potential changes, ranging from increased used of nanotechnology in textile fibers to new types of semiconductors, have been supported in various ways by the federal government. Such improvements may lead to greater manufacturing output, but technological advances in manufacturing are likely to further reduce the need for factory production workers.

• Increases in manufacturing employment are unlikely to result in significant employment opportunities for workers who have not continued their educations beyond high school, as the sorts of tasks performed by manufacturing workers increasingly require higher levels of education and training.

It is important to note that increased manufacturing activity may lead to job creation in economic sectors other than manufacturing. For example, the professional services, information, and finance industries provide about 8% of all inputs into manufacturing, and the transportation and warehousing industry furnishes about 5%, so expansion of manufacturing is likely to stimulate employment in those sectors.54

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

See, for example, Harold L. Sirkin, Michael Zinser, and Douglas Hohner, "Made in America, Again: Why Manufacturing Will Return to the U.S.," Boston Consulting Group, August 2011. |

| 2. |

Manufacturing output, as discussed in this section, is derived from the Federal Reserve Board Industrial Production Indexes, seasonally adjusted, http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm. Employment figures in this section are from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Current Employment Statistics database, http://www.bls.gov/ces/, and are seasonally adjusted. |

| 3. |

On the impact of China on manufacturing employment, see Justin R. Pierce and Peter K. Schott, "The Surprisingly Swift Decline of U.S. Manufacturing Employment," American Economic Review, vol. 106 (2016), pp. 1632-1662, and David H. Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson, "The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States," American Economic Review, vol. 103 (2013), pp. 2121-2168. |

| 4. |

Kerwin Kofi Charles, Erik Hurst, and Mariel Schwartz point out that since 2000, the capital intensity of the U.S. manufacturing sector has increased much more rapidly than the capital intensity of the nonfarm business sector; see "The Transformation of Manufacturing and the Decline in U.S. Employment," Working Paper 24468, National Bureau of Economic Research, March 2018, pp. 16, 18. |

| 5. |

In 1980, an average of 398,829 employees produced 83.9 million tons of steel; see American Iron and Steel Institute, Annual Statistical Report 1980 (Washington, DC, 1981), pp. 8, 21. U.S. steel shipments in 2018 were 95.3 million tons, according to the Institute; see https://www.steel.org/news/2019/02/december-steel-shipments-up-6-point-5-percent-from-december-2017. BLS gives average industry employment in 2018 as 82,800. |

| 6. |

CRS In Focus IF11101, Electrification May Disrupt the Automotive Supply Chain, by Bill Canis. |

| 7. |

Kathrin Hille, "Foxconn: why the world's tech factory faces its biggest tests," Financial Times, June 11, 2019. |

| 8. |

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey for 2017 and previous years, Table 17. For the most recent data, see http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat17.pdf. |

| 9. |

Calculated by CRS from Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment Statistics for May 2018. |

| 10. |

Data from Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational Employment Statistics database, http://data.bls.gov/oes/. |

| 11. |

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey, "Employed Persons by Intermediate Industry, education, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity (25 years and over)," 2018 and prior years. It is unclear whether the higher demand for workers with academic associate degrees reflects higher skill levels among those workers or is a result of individuals with greater ability enrolling in the academic rather than occupational programs at community colleges. |

| 12. |

David Langdon and Rebecca Lehrman, "The Benefits of Manufacturing Jobs," U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, Issue Brief #01-12, May 2012, p. 1. |

| 13. |

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey, Table 18b, http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat18b.htm. |

| 14. |

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Employment Statistics, http://www.bls.gov/ces/. |

| 15. |

Ibid. |

| 16. |

Jessica R. Nicholson and Regina Powers, "The Pay Premium for Manufacturing Workers as Measured by Federal Statistics," U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, Issue Brief #05-15, October 2, 2015, p. 12. There are differences among federal statistical agencies in identification of production and nonsupervisory workers. For example, BLS estimates that 79.5% of workers in motor vehicle manufacturing in 2016 were production and nonsupervisory workers, whereas Census Bureau surveys put the figure at 86.4%. |

| 17. |

The analysis was produced by the Economic Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank concerned with the needs of low- and middle-income workers and closely associated with organized labor. |

| 18. |

Lawrence Mishel, "Yes, manufacturing still provides a pay advantage, but staffing firm outsourcing is eroding it," Economic Policy Institute, March 12, 2018, p. 11, https://www.epi.org/publication/manufacturing-still-provides-a-pay-advantage-but-outsourcing-is-eroding-it/. |

| 19. |

For another example of why a regression analysis using worker-specific variables does not fully answer the question about whether manufacturing pays higher wages than other industries, consider a hypothetical factory in Massachusetts that paid its workers the state manufacturing average of $33.92 per hour in February 2019. This was 1% less than the average private-sector wage in Massachusetts, which was $33.99. Now, assume that the factory relocated to Mississippi, where it paid $22.35 per hour, that state's average wage in manufacturing. This was 9% above the average private-sector wage in Mississippi. Regression analysis using a geographic variable would show that the Mississippi workers receive a manufacturing wage premium, while the former workers in Massachusetts, who received no wage premium despite earning a much higher wage, have disappeared from the data on manufacturing workers. |

| 20. |

Bureau of Labor Statistics, State and Metro Area Employment, Hours, & Earnings, https://www.bls.gov/sae/. |

| 21. |

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employer Costs for Employee Compensation, https://www.bls.gov/ncs. |

| 22. |

Bureau of Labor Statistics, "Union affiliation data from the Current Population Survey," https://www.bls.gov/cps/data.htm. |

| 23. |

Using a definition of benefits that excludes paid leave and supplemental pay, Lawrence Mishel finds that the manufacturing premium in benefits has not declined; see "Yes, manufacturing still provides a pay advantage, but staffing firm outsourcing is eroding it," p. 13. |

| 24. |

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Employment Statistics, http://www.bls.gov/ces/. The wages figures presented here have not been adjusted for inflation. |

| 25. |

Manufacturing activities fall within North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS) sectors 31-33, whereas professional, scientific, and technical services of all sorts fall within NAICS sector 54. |

| 26. |

Andrea Andrenelli et al., Multinational production and trade in services, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD Trade Policy Papers No. 212, March 19, 2018, p. 6. |

| 27. |

Sébastien Miroudot and Charles Cadestin, Services In Global Value Chains, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD Trade Policy Papers No. 197, March 15, 2017, p. 20. |

| 28. |

Ondrej Burkacky et al., "Rethinking car software and electronics architecture," February 2018, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/rethinking-car-software-and-electronics-architecture. |

| 29. |

Calculated by CRS from Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment Statistics for May 2018. |

| 30. |

Dominic Gates, "Boeing goes outside for new Commercial Airplanes CEO," Seattletimes.com, November 21, 2016. |

| 31. |

As an example, United Technologies Corp., which manufactures elevators, aircraft engines, and many other products, reported that "product sales" accounted for 68% of its $66.5 billion of sales in its FY2018, and "service sales" accounted for 32%. Its competitor, General Electric Co., reported that 62% of the $30.6 billion of the FY2018 sales of its aviation segment were services rather than equipment, up from 57% two years earlier. See United Technologies, "Management's Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations," Form 10-K for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2018, p. 33, and General Electric Co., Form 10-K for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2018, p. 21. It is unclear how either of these companies classifies employees and establishments in its responses to government statistical surveys. |

| 32. |

"Other Services (except Public Administration)" fall within NAICS sector 81. |

| 33. |

Nike Inc., based in Oregon, describes its business as "the design, development and worldwide marketing and selling of athletic footwear, apparel, equipment, accessories, and services." It states, "Virtually all of our products are manufactured by independent contractors. Nearly all footwear and apparel products are produced outside the United States, while equipment products are produced both in the United States and abroad." The company was supplied by 124 footwear factories in 13 countries, mainly in Vietnam, China, and Indonesia, and by 328 apparel factories in 37 countries. Its subsidiary Air Manufacturing Innovation manufactures cushioning components and "small amounts of various other plastic products" in the United States. Nike does not disclose U.S. employment, but reported that its Oregon headquarters was occupied by approximately 11,200 employees. Nike Inc., Form 10-K for the fiscal year ended May 31, 2018, pp. 1, 3, 15. |

| 34. |

Cade Metz, "Google Makes Its Special A.I. Chips Available to Others," New York Times, February 12, 2018. |

| 35. |

Cade Metz, "Where in the World Is Google Building Servers?," Wired, July 6, 2012; Alphabet Inc., Form 10-K for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2018, pp. 14, 56. |

| 36. |

Amazon.com, Inc., Form 10-K for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2018, pp. 18, 45. |

| 37. |

Tom Simonite, "New at Amazon: Its Own Chips for Cloud Computing," wired.com, November 27, 2018. |

| 38. |

U.S. Census Bureau, "Enterprise Statistics: 2012 Enterprise Tables," https://www.census.gov/econ/esp/, Table 8. In this survey, which collected data from "enterprises" rather than establishments, each enterprise was assigned to the economic sector with the largest share of the enterprise's payroll (measured in dollars). Most large enterprises would thus be expected to control establishments in more than one economic sector. Some 1.9 million enterprises with a collective $7.7 trillion of sales did not respond to the survey, so the actual number of nonmanufacturing firms purchasing contract manufacturing services may be considerably larger than indicated by the survey. |

| 39. |

Fariha Kamal, "A Portrait of U.S. Factoryless Goods Producers," National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 25193, October 2018. |

| 40. |

U.S. Census Bureau, "Economic Classification Policy Committee (ECPC) Recommendation for Classification of Outsourcing in North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) Revisions for 2012," http://www.census.gov/eos/www/naics/fr2010/ECPC_Recommendation_for_Classification_of_Outsourcing.pdf. |

| 41. |

The data are difficult to interpret. The Census Bureau assigned enterprises to economic sectors based on establishment-level data about employment. So, for example, an enterprise would likely have been assigned to the retail trade sector if the largest group of its employees worked in retail establishments, even if it owned establishments in other sectors as well. In March 2012, 643 enterprises classified as being in the retail trade sector, with a total of 75,470 employees, reported that 100% of their operating revenue and net sales came from providing contract manufacturing services. It is not apparent why such enterprises would have been classified as retail enterprises. For data, see U.S. Census Bureau, "Enterprise Statistics: 2012 Enterprise Tables," Table 7. For definitions, see U.S. Census Bureau, "Definitions for the Enterprise Statistics Program," https://www.census.gov/econ/esp/definitions.html. The Enterprise Statistics Program operated from 1954 to 1992 and again from 2007 to October 2016, when it was again discontinued. |

| 42. |

For background on factoryless manufacturing, see Susan Houseman and Michael Mandel, eds., Measuring Globalization: Better Trade Statistics for Better Policy, vol. 2 (Kalamazoo, MI: Upjohn Institute, 2015). Some of the objections to the change are laid out in Robert E. Scott, "What Is Manufacturing and Where Does It Happen?," Economic Policy Institute, July 21, 2014, http://www.epi.org/publication/what-is-manufacturing-and-where-does-it-happen/. The postponement order appeared as Office of Management and Budget, "2017 North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) Revision," Federal Register, vol. 79, no. 153, August 8, 2014, p. 46558. |

| 43. |

According to the BLS Occupational Employment Statistics, 740,410 workers in production occupations and 709,110 hand laborers and material movers worked for employment services firms in May 2017. Following Matthew Dey, Susan Houseman, and Anne Polivka, Manufacturers' Outsourcing to Temporary Help Services: A Research Update, BLS working paper 493, January 2017, the figures given here and in Table 3 assume that 85% of employment service workers in production occupations and 50% of those in hand labor and material moving are engaged in manufacturing. The analysis by Dey et al. assigns some temporary workers in office and administrative support occupations to manufacturing, whereas the analysis here does not. For details, see Matthew Dey, Susan N. Houseman, and Anne E. Polivka, "Manufacturers' Outsourcing to Staffing Services," Industrial & Labor Relations Review, vol. 65 (2012), p. 549. |

| 44. |

Dey et al., "Manufacturers' Outsourcing to Temporary Help Services," p. 6. |

| 45. |

An establishment is defined as "a single physical location where business is conducted or where services or industrial operations are performed." In the manufacturing sector, an establishment is analogous to a factory, and the terms are used interchangeably in this section. |

| 46. |

U.S. Census Bureau, Geography Area Series: County Business Patterns by Employment Size Class, Table CB1400A13. The number of manufacturing establishments with more than 1,000 employees was 1,504 in 1998, and declined until 2013. Due to definitional changes, data for 1998 and subsequent years are not compatible with those for earlier years. |

| 47. |

Census Bureau, County Business Patterns, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cbp.html. |

| 48. |

"Gross" job gains and losses refer to the number of positions created and eliminated, respectively; the net change in employment can be calculated by subtracting gross job losses from gross job gains. For technical details on this database, see http://www.bls.gov/news.release/cewbd.tn.htm. |

| 49. |

See http://www.bls.gov/web/cewbd/table1_5.txt and http://www.bls.gov/web/cewbd/table1_6.txt. |

| 50. |

For information about this database, see https://www.census.gov/ces/dataproducts/bds/data.html. |

| 51. |

John Haltiwanger, Ron Jarmin, and Javier Miranda, Historically Large Decline in Job Creation from Startup and Existing Firms in the 2008-09 Recession, March 2011, http://www.ces.census.gov/docs/bds/plugin-BDS%20March%202011%20single_0322_FINAL.pdf. |

| 52. |

U.S. Census Bureau, Business Dynamics Statistics, Establishment Characteristics Data Tables, September 2017, https://www.census.gov/ces/dataproducts/bds/data_estab.html. |

| 53. |

CRS Report R44266, Effects of Buy America on Transportation Infrastructure and U.S. Manufacturing, by Michaela D. Platzer and William J. Mallett. |

| 54. |

Estimates taken from Bureau of Economic Analysis, "Use of Commodities by Industries before Redefinitions," 2013, http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_industry.cfm. |