Introduction

Each year, the House and Senate armed services committees take up national defense authorization bills. The House of Representatives passed its version of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 (NDAA; H.R. 2500) on July 12, 2019. The Senate passed its version of the NDAA (S. 1790) on June 27, 2019. These bills contain numerous provisions that affect military personnel, retirees, and their family members. Provisions in one version sometimes are not included in the other, are treated differently, or are identical in both versions. Following passage of each chamber's bill, a conference committee typically convenes to resolve the differences between the respective chambers' versions of the bill. A conference report is to be issued and considered by each chamber. Upon passage in both chambers, the final bill would be transmitted to the President.

This report highlights selected personnel-related issues that may generate high levels of congressional and constituent interest. CRS will update this report to reflect enacted legislation. Related CRS products are identified in each section to provide more detailed background information and analysis of the issues. For each issue, a CRS analyst is identified.

Some issues discussed in this report were previously addressed in the FY2019 NDAA (P.L. 115-232) and discussed in CRS Report R45343, FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act: Selected Military Personnel Issues, by Bryce H. P. Mendez et al., or other reports. Issues that were considered previously are designated with an asterisk in the relevant section titles of this report.

*Active Component End-Strength

Background: The authorized active duty end-strengths for FY2001, enacted in the year prior to the September 11 terrorist attacks, were as follows: Army (480,000), Navy (372,642), Marine Corps (172,600), and Air Force (357,000). 1 Over the next decade, in response to the demands of wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, Congress substantially increased the authorized personnel strength of the Army and Marine Corps. Congress began reversing those increases in light of the withdrawal of most U.S. forces from Iraq in 2011, the drawdown of U.S. forces in Afghanistan beginning in 2012, and budgetary constraints. Congress halted further reductions in Army and Marine Corps end-strength in FY2017, providing slight end-strength increases for both Services that year. In FY2018 and FY2019, Congress again provided slight end-strength increases for the Marine Corps, while providing a more substantial increase for the Army. However, the Army did not reach its authorized end-strength of 483,500 in FY2018 or its authorized end-strength of 487,500 in FY2019, primarily due to missing enlisted recruiting goals. End-strength for the Air Force generally declined from 2004 to 2015, but increased from 2016 to 2019. End-strength for the Navy declined from 2002 to 2012, increased in 2013 and remained essentially stable through 2017; it increased again in 2018 and 2019.

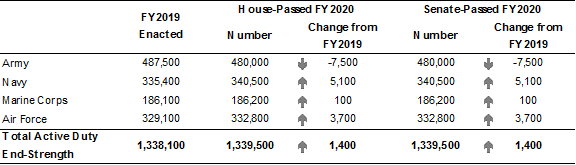

Authorized end-strengths for FY2019 and the end-strengths that would be authorized for FY2020 under H.R. 2500 and S. 1790 are shown in Figure 1.

|

House-Passed H.R. 2500 |

Senate-Passed S. 1790 |

|

Sec. 401 would authorize a total FY2020 active duty end-strength of 1,339,500 including 480,000 for the Army |

Sec. 401 would authorize a total FY2020 active duty end-strength of 1,339,500 including 480,000 for the Army |

Discussion: Both the House and Senate bills would authorize active duty end-strength levels identical to the Administration's request. In comparison to FY2019 authorized end-strengths, the Administration's FY2020 budget proposed a decrease for the Army (-7,500) and increases for the Navy (+5,100), Marine Corps (+100) and Air Force (+3,700). The proposed decrease for the Army reflects the challenges the Army is facing in recruiting a sufficient number of new enlisted personnel to expand its force. As stated in the Army's military personnel budget justification document, "Given the FY 2018 end strength outcome and a challenging labor market for military recruiting, the Army Active Component has decided to pursue a new end strength growth ramp. The Army has shifted to a more modest end strength growth ramp of 2,000 Soldiers per year, with end strength targets of 478,000 in FY 2019 and 480,000 in FY 2020. Beyond FY 2019, the steady 2,000 Solider per year growth increases Active Army end strength while maintaining existing high quality standards."2

|

Figure 1. Comparison of FY2019 Enacted Active Duty End-Strength with Potential FY2020 End-Strength in H.R. 2500 and S. 1790 |

|

|

Note: Up arrows indicate potential increases from the FY2019 authorization. |

References: Previously discussed in CRS Report R45343, FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act: Selected Military Personnel Issues, by Bryce H. P. Mendez et al. and similar reports from earlier years. Enacted figures found in P.L. 115-232.

CRS Point of Contact: Lawrence Kapp.

*Selected Reserve End-Strength

Background: The authorized Selected Reserve3 end-strengths for FY2001, enacted the year prior to the September 11 terrorist attacks, were: Army National Guard (350,526), Army Reserve (205,300), Navy Reserve (88,900), Marine Corps Reserve (39,558), Air National Guard (108,022), Air Force Reserve (74,358), and Coast Guard Reserve (8,000).4 The overall authorized end-strength of the Selected Reserves has declined by about 6% over the past 18 years (874,664 in FY2001 versus 824,700 in FY2019). During this period, the overall decline is mostly attributed to reductions in Navy Reserve strength (-29,800). There were also smaller reductions in the authorized strength for the Army National Guard (-7,026), Army Reserve (-5,800), Marine Corps Reserve (-1,058), Air National Guard (-922), Air Force Reserve (-4,358), and Coast Guard Reserve (-1,000).

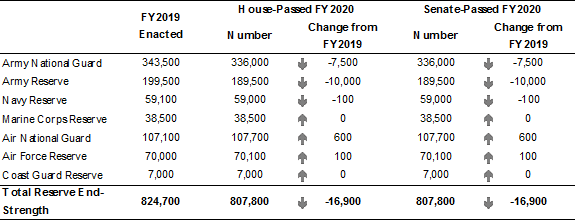

Authorized end-strengths for FY2019 and the end-strengths that would be authorized by H.R. 2500 and S. 1790 for FY2020 are shown in Figure 2.

|

House-Passed H.R. 2500 |

Senate-Passed S. 1790 |

|

Sec. 411 would authorize a total FY2020 Selected Reserve end- strength of 807,800 including: Army National Guard: 336,000 |

Sec. 411 would authorize a total FY2020 Selected Reserve end- strength of 807,800 including: Army National Guard: 336,000 |

Discussion: Both the House and Senate bills would authorize Selected Reserve end-strength levels identical to the Administration's request. Relative to FY2019 authorized end-strengths, the Administration's FY2020 budget proposed decreases in the Army National Guard (-7,500), Army Reserve (-10,000), and Navy Reserve (-100), increases for the Air National Guard (+600) and Air Force Reserve (+100), and no change for the Marine Corps Reserve and Coast Guard Reserve. The Administration's proposed decrease for the Army National Guard and the Army Reserve reflected the challenges those reserve components have had in meeting their authorized strength. According to the Army National Guard (ARNG) FY2020 military personnel budget justification document:

The ARNG fell short of the FY 2018 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) Congressionally authorized End Strength 343,500 by 8,296 Soldiers due to recruiting challenges, too few accessions, and to cover increased attrition losses in FY2018…The ARNG began addressing these issues and challenges in FY 2018 by ramping up the recruiting force, incentives programs, bonuses, and marketing efforts. While these efforts are expected to result in additional accessions in FY 2019, they will not be enough to meet the FY 2019 NDAA authorized End Strength of 343,500. The newly hired force will reach full production levels by end of the FY 2019 in order to meet the required accessions mission and a projected end strength of 336,000 in FY 2020 and continue the projected ramp to an end strength of 338,000 by the end of FY 2024.5

Similarly, the Army Reserve FY2020 Military Personnel budget justification document stated:

In FY 2018, the Army Reserve fell short of its end strength objective by 10,689 Soldiers due to a challenging recruiting and retention environment…Prior to the FY 2020 President's Budget request, the Army Reserve recognized it would not meet its FY 2019 end strength goal of 199,500 and subsequently reduced its goal to a more achievable end strength of 189,250. The Army Reserve continues to set conditions for a successful and productive recruiting and retention environment in support of achieving an end strength of 189,250 by the end of FY 2019 and sustaining that level through FY 2020.6

|

Figure 2. Comparison of FY2019 Enacted Selected Reserve End-Strength with FY2020 End-Strength in H.R. 2500 and S. 1790 |

|

|

Note: Up arrows indicate increases from the FY2019 authorization. |

References: Previously discussed in CRS Report R45343, FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act: Selected Military Personnel Issues, by Bryce H. P. Mendez et al. and similar reports from earlier years. For more on the Reserve Component see CRS Report RL30802, Reserve Component Personnel Issues: Questions and Answers, by Lawrence Kapp and Barbara Salazar Torreon, and CRS In Focus IF10540, Defense Primer: Reserve Forces, by Lawrence Kapp.

CRS Point of Contact: Lawrence Kapp.

Access to Reproductive Health Services

Background: In general, the Department of Defense (DOD) offers certain reproductive health services in DOD-operated hospitals and clinics—known as military treatment facilities (MTFs)—or through civilian health care providers participating in TRICARE.7 Reproductive health services typically include counseling, therapy, or treatment for male or female conditions affecting "fertility, overall health, and a person's ability to enjoy a sexual relationship."8

With regard to contraceptive services, DOD policy requires that all eligible beneficiaries have access to "comprehensive contraceptive counseling and the full range of contraceptive methods."9 The policy also requires that contraceptive services be provided when "feasible and medically appropriate," such as during:

- a health care visit before or during deployment;

- enlisted or officer training;

- annual well woman exams and reproductive health screenings;

- physical exams; or

- when referred after a periodic health assessment.10

With regard to fertility services, DOD offers:

- diagnostic services (e.g., hormone evaluation and semen analysis);

- diagnosis and treatment of illness or injury to the male or female reproductive system;

- care for physically caused erectile dysfunction;11

- genetic testing;12

- certain prescription fertility drugs;13 and

- certain assisted reproductive services for "seriously or severely ill/injured" active duty servicemembers.14

Active duty military personnel generally incur no out-of-pocket costs for DOD health care services.15 If a servicemember receives reproductive health services that are not directly provided, referred by a DOD or TRICARE provider, or otherwise covered by DOD, then they may be required to pay for those services.16 Other DOD beneficiaries may be subject to cost-sharing based on their TRICARE health plan, beneficiary category, and type of medical service received.17

|

House-Passed H.R. 2500 |

Senate-Passed S. 1790 |

|

Sec. 701 would amend 10 U.S.C. §1074d to mandate TRICARE coverage of "all methods of contraception approved by the Food and Drug Administration" (FDA) for female servicemembers and retirees. Beneficiaries enrolled in TRICARE Prime or TRICARE Select would have no cost-sharing requirements. |

Sec. 701 is a similar provision to House Sec. 701. Coverage requirements would take effect on January 1, 2020. |

|

Sec. 5701 would revise Section 701 of the bill, providing TRICARE program coverage of "all methods of contraception approved by the [FDA]," to instead take effect on January 1, 2030. |

|

|

Sec. 702 would require DOD to provide written and oral information on "all methods of emergency contraception approved by the [FDA]" to all sexual assault survivors presenting at a military treatment facility. DOD would also be required to provide emergency contraception, upon request of a sexual assault survivor. |

No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 709 would allow DOD to offer assisted reproductive services to active duty servicemembers or their spouses with no cost share. |

No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 722 would direct the Secretary of Defense to conduct a pilot program that allows for cryopreservation and storage of sperm and eggs of active duty servicemembers deploying to a combat zone. |

No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 728 would require DOD to conduct a study on infertility among active duty servicemembers. |

No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 734 would require DOD, in consultation with the Department of Homeland Security (with respect to the U.S. Coast Guard), to establish a standardized family planning education program for servicemembers during the first year of service and at other times deemed appropriate. |

No similar provision. |

Discussion: Provisions considered in the House and Senate bills would expand TRICARE coverage of specific reproductive health services to certain eligible beneficiaries. Currently, DOD offers comprehensive contraceptive counseling and a range of contraceptive methods. However, non-active duty beneficiaries may be subject to certain cost-sharing requirements depending on the type of contraceptive service rendered, accompanying procedures or follow-up evaluations that may be clinically necessary, or if the health care provider does not participate in the TRICARE network. Other reproductive health services, such as cryopreservation of human gametes (i.e., sperm or eggs), are generally not offered or covered by TRICARE unless meeting narrow criteria for eligibility.18

Section 701 of the House and Senate bills would codify (in 10 U.S.C. §1074d) DOD's current practice of making available all FDA-approved methods of contraception (and counseling on such methods) to all beneficiaries. These sections would also remove any cost-sharing requirements for contraceptive services, regardless of beneficiary category, enrollment status, or where the services are received (i.e., network vs. non-network provider). The House bill would require contraception coverage upon enactment, while the Senate bill would take effect on January 1, 2030.

Section 702 of the House bill would require DOD to provide written and oral information on all FDA-approved methods of emergency contraception to sexual assault victims presenting for care at an MTF. DOD policy currently lists a similar requirement for MTF health care providers to consult with sexual assault victims, once clinically stable, on the "risk of pregnancy, options for emergency contraception, and any follow-up care and referral services to the extent authorized by law."19

Generally, DOD does not offer family planning education as a standard training requirement for new military recruits. Rather, servicemembers must request the service from MTF staff, TRICARE providers, or military medical personnel embedded in certain units. Section 734 of the House bill would require DOD, in consultation with the Department of Homeland Security (with regard to the U.S. Coast Guard), to establish a standardized family planning curriculum and education programs for all members of the Armed Forces. All servicemembers would be required to receive family planning education during their first year of military service and when indicated by a respective Secretary of a military department.

Sections 709, 722, and 728 of the House bill would allow DOD to provide and study certain services (also referred to as assisted reproductive technologies or ART) to treat infertility among servicemembers.20 In general, DOD considers these services as "elective in nature" and excludes ART from TRICARE coverage.21 Section 709 would authorize, but not require, the Secretary of Defense to offer ART, ART counseling, reversal of surgical sterilization (i.e., tubal ligation or vasectomy), and cryopreservation of human gametes to servicemembers or their spouses. The provision would also prohibit any cost sharing for such services.

Section 722 would require DOD to conduct a pilot program that allows active duty servicemembers deploying to a combat zone to cryopreserve and store their gametes. The program would allow a servicemember to store their gametes up to one year after retiring or separating from military service, and at no cost to the participant. Section 728 would require a DOD report to Congress on the incidence of infertility among servicemembers, including a comparison to the general U.S. population, access to infertility services, and the potentiality of service-connected infertility.

References: CRS In Focus IF11109, Defense Health Primer: Contraceptive Services, by Bryce H. P. Mendez.

CRS Point of Contact: Bryce H.P. Mendez.

*Administration of the Military Health System

Background: DOD operates a health care delivery system that serves approximately 9.5 million beneficiaries.22 The Military Health System (MHS) administers the TRICARE program, which offers health care services at military treatment facilities (MTFs) or through participating civilian health care providers.23 Historically, the military services have administered the MTFs, while the Defense Health Agency (DHA) administered the private sector care program of TRICARE. DHA is a combat support agency that enables the Army, Navy, and Air Force medical services to provide a medically ready force and ready medical force to combatant commands in both peacetime and wartime.24

In 2016, Congress found that the organizational structure of the MHS could be streamlined to sustain the "medical readiness of the Armed Forces, improve beneficiaries' access to care and the experience of care, improve health outcomes, and lower the total management cost."25 Section 702 of the FY2017 NDAA (P.L. 114-328) directed significant reform to the MHS and administration of MTFs by October 1, 2018. Reforms include:

- transfer of administration and management of MTFs from each respective service surgeon general to the DHA Director;

- reorganization of DHA's internal structure; and

- redesignation of the service surgeons general as principal advisors for their respective military service, and as service chief medical advisor to the DHA.

In June 2018, DOD submitted its implementation plan to Congress. The implementation plan details how DOD is to reform the MHS to a "streamlined organizational model that standardizes the delivery of care across the MHS with less overhead, more timely policymaking, and a transparent process for oversight and measurement of performance."26 Congress later revised the MHS reform mandate by further clarifying certain tasks relating to the transfer of MTFs, the roles and responsibilities of the DHA and the service surgeons general, and by extending the deadline for implementing reform efforts to September 30, 2021. DOD later revised its plan to accelerate certain tasks.

On October 1, 2019, the military services transferred the administration and management of their U.S.-based MTFs to the DHA. The military services are to continue to administer their overseas MTFs until transfer to the DHA in 2020–2021.

|

House-Passed H.R. 2500 |

Senate-Passed S. 1790 |

|

Organizational Management No similar provision |

Organizational Management Sec. 711 would amend 10 U.S.C. §1073c by inserting additional responsibilities for the DHA Director in administering the MTFs, revising the qualifications for the DHA Assistant Director for Health Care Administration, clarifying the responsibilities for certain DHA Deputy Assistant Directors, and further defining an MTF. |

|

No similar provision. |

Sec. 712 would amend Section 712 of the FY2019 NDAA (P.L. 115-232) to further clarify the role of the service surgeons general in supporting medical requirements of combatant commands and the role of the Military Departments in maintaining administrative control of military personnel assigned to MTFs. |

|

No similar provision. |

Sec. 713 would establish a four-year minimum requirement for the tour of duty as an MTF commander or director. |

|

No similar provision. |

Sec. 715 would require DOD to establish up to four "regional medical hubs" to support combatant command operational medical requirements. |

|

No similar provision. |

Sec. 5703 would require the Secretary of Defense to preserve the resources assigned to the Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, notwithstanding its administrative and mission realignments to the Army Futures Command and the Defense Health Agency. |

|

Military Medical Workforce Sec. 718 would limit certain changes to military medical end-strength. |

Military Medical Workforce No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 749 would require the Secretary of Defense to provide a report to Congress on operational medical and dental personnel requirements. |

No similar provision. |

|

Civilian Partnerships Sec. 726 would require DOD to study the use of "military-civilian integrated health delivery systems" and provide a report to Congress no later than 180 days after enactment. |

Civilian Partnerships No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 751 would require DOD to partner with academic health centers and establish a "University Affiliated Research Center" that would focus on care for wounded servicemembers. |

No similar provision. |

|

No similar provision. |

Sec. 727 would allow DOD to conduct a pilot program using military-civilian partnerships to enhance interoperability and medical surge capabilities of the National Disaster Medical System. |

Discussion: The House and Senate bills include a number of provisions that would clarify certain responsibilities for DHA and other medical entities with service-specific responsibilities, such as administering and managing MTFs, providing health service support to combatant commanders, performing medical research, and recruiting and retaining medical personnel.

Organizational Management. Section 711 of the Senate bill would amend 10 U.S.C. §1073c to clarify the qualifications of the DHA assistant director and would add the following to DHA's roles and responsibilities:

- provision of health care;

- clinical privileging and quality of care programs;27

- MTF capacities to support clinical currency and readiness standards;28 and

- coordination with the military services for joint staffing.

Section 712 of the Senate bill clarifies the roles and responsibilities of the service surgeons general, including:

- support to combatant commanders for operational and deployment requirements;

- support to DHA by assigning military medical personnel to MTFs;

- development of combat medical capabilities; and

- medical readiness of the Armed Forces.

Generally, there is no statutory minimum or maximum length for the tour of duty as an MTF commander or director. Historically, a service surgeon general selected an MTF commander to serve a two- or three-year tour of duty. Since the enactment of recent MHS reforms, the service surgeons general nominate and recommend candidates to the DHA for MTF commander or director positions.29 DHA selects individuals and determines the length for the tour of duty. Section 713 of the Senate bill would require DOD to establish a minimum length for the tour of duty for MTF commanders or directors, which must be no shorter than four years.

Section 715 would require DOD to designate no more than four MTFs as regional referral centers for specialized care or "regional medical hubs" by October 1, 2020. A general or flag officer would lead each regional medical hub and would be responsible for providing specialty care to patients referred from other MTFs, TRICARE providers, or VA medical facilities.

In 2018, Congress directed DOD to consolidate most of its medical research programs under the DHA.30 While the military services are to retain certain medical research responsibilities, the DHA is to be responsible for coordinating all research, development, test, and evaluation (RDT&E) funds appropriated to the defense health program (DHP), including the congressionally directed medical research programs (CDMRP).31 The U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (USAMRMC) administers the CDMRP and executes a variety of RDT&E funds appropriated to the Department of the Army, DHP, and other DOD-wide operation and maintenance accounts. USAMRMC executes most of the annual DHP RDT&E. In FY2017, USAMRMC executed approximately 76% ($377.5 million) of the total DHP RDT&E funds.32 As of June 1, 2019, USAMRMC restructured and realigned its responsibilities under two separate DOD entities: the DHA and Army Futures Command.33 Depending on the research mission (DHP requirements vs. service-specific requirements), USAMRMC resources were also reallocated accordingly.34 Section 5703 would direct the Secretary of Defense to retain certain manpower and funding resources with USAMRMC.

Military Medical Personnel. DOD's budget request for FY2020 includes a proposal to reduce its active duty medical force by 13% (14,707 personnel) in order to maintain a workforce that is "appropriately sized and shaped to meet the National Defense Strategy requirements and allow the MHS to optimize operational training and beneficiary care delivery."35 Compared to FY2019 levels, the Army would have the largest reduction in medical forces (-16%), followed by the Air Force (-15%), and the Navy (-7%).36 DOD's initial plan to implement these reductions include: (1) transferring positions (also known as billets) from the MHS to new health service support positions in deployable or warfighting units, military service headquarters, or combatant commands; (2) transferring billets from the MHS to the military departments for repurposing as nonmedical assets; and (3) converting certain military billets to civilian billets.37

Section 718 of the House bill would limit DOD actions to reduce or realign its active duty medical force until certain internal reviews, analyses, measurements, and outreach actions are completed within 180 days of enactment, and at least 90 days after a report to Congress on such actions have been provided. The provision does allow DOD to reduce or realign certain positions (also referred to as billets) that have been unfilled since at least October 1, 2018. Section 749 would require a DOD report to Congress on how military medical and dental personnel requirements are identified, including joint planning assumptions and additional factors considered in the analysis.38

Civilian Partnerships. The MHS states that its "success depends on building strong partnerships with the civilian health care sector."39 As a high-priority initiative, the MHS maintains numerous partnerships with civilian health care organizations, academic institutions, and research entities to enhance or supplement military medical readiness and deliver the health entitlements authorized in chapter 55 of Title 10, U.S. Code.40 Both bills include provisions that would direct DOD to use its authority to partner with civilian entities to enrich certain medical care capabilities. Section 751 of the House bill would require DOD partnerships with academic health centers to focus on biomedical research for wounded servicemembers. Section 727 of the Senate bill would authorize DOD to conduct a pilot program to improve medical surge capabilities of the National Disaster Medical System and interoperability with certain civilian health care organizations and other federal agencies.41

References: Previously discussed in CRS Report R45343, FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act: Selected Military Personnel Issues, by Bryce H. P. Mendez et al.; CRS In Focus IF11273, Military Health System Reform, by Bryce H. P. Mendez; CRS Report WPD00010, Military Health System Reform, by Bryce H. P. Mendez; CRS Insight IN11115, DOD's Proposal to Reduce Military Medical End Strength, by Bryce H. P. Mendez; and CRS Report R45399, Military Medical Care: Frequently Asked Questions, by Bryce H. P. Mendez.

CRS Point of Contact: Bryce H.P. Mendez.

Boards of Correction of Military Records & Discharge Review Board Matters

Background: The characterization of a servicemember's discharge, as well as certain awards, and amount of time on active duty, may affect eligibility for certain veteran benefits. If a servicemember believes that information in his or her military records is incorrect or alleges an injustice, two statutorily established mechanisms exist for correcting these records: a board of correction of military records (BCMR) and a discharge review board (DRB). A BCMR provides an administrative process for military personnel to request record corrections and payment of monetary claims associated with a record correction.42 An applicant must request a record correction within three years of discovering an alleged error or injustice.43

A DRB provides an administrative process for former servicemembers to request changes to the character of discharge or reason for discharge, but any monetary claim associated with a discharge change must be presented to a BCMR. An application for review must be made within 15 years of the applicant's discharge or dismissal.44 A subsequent change in policy has no effect on a preceding discharge unless the new policy is retroactive or materially different in a way that would substantially enhance a servicemember's rights and likely invalidate the discharge.

Statute requires a DRB to give liberal consideration to an application in which post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD), traumatic brain injury (TBI), or mental health conditions typically associated with combat operations may have been a factor in the discharge decision.45 The liberal consideration requirement equally applies to discharge reviews in which sexual assault or harassment caused PTSD, TBI, or mental health conditions may have been a factor in the basis for the discharge decision.46

|

House-Passed H.R. 2500 |

Senate-Passed S. 1790 |

|

Oversight and Operations Sec. 521 would require a DOD discharge appeals board to consider appeals of DRB denials and an annual appeals data report to be published online. |

Oversight and Operations No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 522 would extend the restriction on reducing personnel assigned to a service review agency, remove the option to unilaterally reduce service review agency personnel under certain conditions, and require a report by each Service Secretary on a plan to reduce application backlogs and maintain resources at the Services' review agency. |

No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 523 would establish a four-year defense advisory committee to oversee BCMR and DRB activities and publish an annual observations and recommendations report. |

No similar provision. |

|

No similar provision. |

Sec. 546 would repeal the requirement to apply for a discharge review within 15 years of a discharge or dismissal. |

|

No similar provision. |

Sec. 547 would reduce the minimum number of members required for a DRB from five to three. |

|

PTSD, TBI, or Other Trauma Mental Health Conditions No similar provision. |

PTSD, TBI, or Other Trauma Mental Health Conditions Sec. 548 would require a BCMR or DRB to consider previously issued opinions by a social worker (with training on PTSD, TBI, or other trauma mental health conditions for cases that are related to combat or sexual trauma, intimate partner violence, or spousal abuse). |

|

No similar provision. |

Sec. 549 would expand BCMR and DRB subject matter jurisdiction to include sexual trauma, intimate partner violence, or spousal abuse that serves as all or part of the justification for an application based on PTSD, TBI, or other trauma mental health conditions; and would repeal the term "military sexual trauma." |

|

Sec. 530D would require a BCMR or DRB reviewing a case based on PTSD, TBI, or other trauma, to seek advice and counsel from a psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker with training on mental health issues associated with these conditions, as well as other related experts. |

Sec. 550 is a similar provision to House Sec. 530D. |

|

Sec. 530E would require the training curriculum for BCMR and DRB members include topics on sexual trauma, intimate partner violence, spousal abuse, and the various responses of individuals to trauma. |

Sec. 551 is a similar provision to House Sec. 530E. |

|

No similar provision. |

Sec. 552 would require the diagnosis assigned to a separating servicemember who has a mental condition as a result of being a victim of a sex-related, intimate partner violence-related, or spousal abuse-related offense, be corroborated by a competent mental health care professional at or above the level of the healthcare professional rendering the diagnosis and endorsed by the respective service surgeon general. The provision would also prohibit DOD from using the term "disability" as a reason for discharge or in a discharge narrative. |

|

No similar provision. |

Sec. 553 would require a BCMR and DRB to review, "with liberal consideration," all evidence and information submitted relating to PTSD, TBI, or other trauma, or a case based on sexual trauma, intimate partner violence, or spousal abuse, (including information produced by the VA or a civilian healthcare provider). |

|

Separations for Homosexual Conduct Sec. 530H would require a DRB, when requested by a former servicemember, or other designated individuals, to review a discharge and separation based on sexual orientation, and upgrade the discharge to honorable, or remove any reference to sexual orientation on a DD-214 if the discharge was honorable, if the DRB finds such action is appropriate. |

Separations for Homosexual Conduct No similar provision. |

|

Nullification Provisions No similar provision. |

Nullification Provisions Sec. 5546 would nullify sections 546–553 and declare these sections as having "no force or effect." |

Oversight and Operations. House Sections 521 and 523 have a common purpose—increased oversight of BCMRs and DRBs. Section 521 would create a new capacity and entity for discharge review appeals and reporting requirements for discharge review appeals data. While DOD has a complaint process for DRB denial decisions, there is no adjudicatory and independent appeals process for discharge reviews.47 Section 523 would create a defense advisory committee for a term of four years to oversee BCMR and DRB structure, practice, and procedure. The committee would publish an annual report for the Secretary of Defense and congressional defense committees with observations and recommendations regarding board operations and efficacy, among other things.

House Section 522 would amend 10 U.S.C. §1559 to extend previously authorized restrictions on reducing personnel levels at service review agencies until December 31, 2025. The provision would require each Service Secretary to report to Congress his or her plan to reduce application backlogs and maintain resources at the Services' review agencies. This section would also repeal the authority of the Secretary of Defense to reduce personnel at service review agencies.

Senate Section 546 would eliminate the time limits to file a discharge review application. Under 10 U.S.C.§1553(a), a servicemember, deceased servicemember's next of kin, or legal representative of either, are allowed to submit an application to a DRB up to 15 years after the discharge or dismissal. Removing the 15-year limit would create a perpetual capacity for these individuals to apply for a discharge review.

Senate Section 547 would reduce the number of required DRB members from five to three. If overall service review agency personnel requirements remain unchanged, reducing the number of DRB members and reallocating the previously required fourth and fifth members to new DRBs could presumably increase the number of DRBs available.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), or Other Trauma Mental Health Conditions. Senate Sections 548 through 553 are a series of provisions that have a common purpose with regard to military discharges and military records—addressing the effects of PTSD, TBI, or other trauma mental health conditions related to combat or sexual trauma, intimate partner violence, or spousal abuse. Consistent with this purpose, Section 549 affects all other sections in this series because it would repeal the term "military sexual trauma" where it appears in the laws that authorize a BCMR and DRB by replacing it with the terms "sexual trauma, intimate partner violence, or spousal abuse." Additionally, Section 551 would amend current statutorily mandated training for BCMR and DRB members to include curricula on sexual trauma, intimate partner violence, and spousal abuse, and the various responses to these events. House Section 530E is a similar requirement.

Senate Section 552 would require DOD to take certain actions prior to separating a servicemember based on a mental health condition that is not classified as a disability and if the member was a victim of a sex-related offense, an intimate partner violence-related offense, or a spousal-abuse offense. First, a mental health care professional at a peer or higher level to the diagnosing health care professional must corroborate the condition. Second, the service surgeon general must endorse the diagnosis and corroboration. This section further requires that any separation for a mental health condition that is not classified as a disability will use the term "condition," not the term "disability," as the narrative reason for the separation on the member's certificate of release or discharge from active duty (also known as the DD-214). In addition, it would prohibit the term "Secretarial authority" from being used as the narrative reason for separation.48

When reviewing an application in which mental health conditions related to combat or sexual trauma, intimate partner violence, or spousal abuse are in part, or in whole, a basis for the correction or discharge, Senate Section 548 would require a BCMR or DRB to also consider any opinion issued by a social worker with training on PTSD, TBI, or other trauma. A BCMR or DRB would be required to consider an issued opinion that is (1) already included in a service record as part of a diagnosis of an applicant while serving in the Armed Forces, and (2) provided or submitted by the applicant.

Senate Section 550 would require that when a BCMR or DRB obtains a medical opinion on two types of cases it must include opinions from specified healthcare professionals. First, for cases based in whole or in part on PTSD or TBI related to combat, a BCMR or DRB would be required to seek advice and counsel from a psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker with post-traumatic stress disorder or traumatic brain injury or other trauma training. Second, for cases based in whole or in part on PTSD or TBI related to sexual trauma, intimate partner violence, or spousal abuse, a DRB would be required to seek advice and counsel from a psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker with post-traumatic stress disorder or traumatic brain injury or other trauma training for these types of cases and a BCMR would be required to seek advice and counsel from an expert in trauma specific to sexual assault, intimate partner violence, or spousal abuse, for these types of cases. House Section 503D would impose a similar requirement.

Senate Section 553 would require a BCMR or DRB to review all evidence and information provided by an applicant, including lay evidence or medical evidence provided by the VA or civilian health care providers. This provision would also require liberal consideration when reviewing evidence for a record correction or discharge review based in whole or in part on PTSD or TBI- related to combat or sexual trauma, intimate partner violence, or spousal abuse.

Separations for Homosexual Conduct. If a discharge was based on sexual orientation, House Section 530H would remove the DRB presumption of administrative regularity that a discharge was correct and proper. Eliminating this presumption relieves the applicant of the burden to show by substantial evidence that a discharge was not correct and proper. This provision would allow a DRB to review and change, upon request and if found appropriate, the discharge characterization of a servicemember originally discharged based on sexual orientation. If an application for review of a discharge based on sexual orientation is denied, the provision would establish a discretionary appeal process consistent with existing DRB procedures by the applicant.49

S. 1790 Nullification Amendment. Senate Section 5546 is an amendment to the bill that reads "Part III of subtitle D of Title V, and the amendments made by the part, shall have no force or effect." This section would nullify Senate sections 546 through 553.

References: CRS Report R43928, Veterans' Benefits: The Impact of Military Discharges on Basic Eligibility, by Sidath Viranga Panangala.

CRS Point of Contact: Alan Ott.

*Defense Commissary System

Background: Over the past several decades, Congress has been concerned with improving the Defense Commissary Agency (DeCA) system, mandating 12 reports or studies between 1989 and 2015 that considered the idea of consolidating the three military exchanges and the commissary agency.50 Recent reform proposals have sought to reduce DeCA's reliance on appropriated funds without compromising patrons' commissary benefits or reducing the revenue generated by DOD's military exchanges, which are nonappropriated fund (NAF) entities that fund morale, welfare, and recreation (MWR) facilities on military installations. However, 10 U.S.C. §2482 prohibits the Defense Department from undertaking consolidation without new legislation. Section 627 of the FY2019 NDAA (P.L. 115-232) required the Secretary of Defense to conduct a study to determine the feasibility of consolidating commissaries and military exchange entities into a single defense resale system. The study, The Department of Defense Report on the Development of a Single Defense Resale System, April 29, 2019, concluded that the benefits of consolidating DeCA and the military exchanges into one defense resale entity far outweighed the costs. This DOD study "projected net savings of approximately $700M–$1.3B of combined appropriated and nonappropriated funding over a five-year span, and recurring annual savings between $400M-$700M thereafter."51 Opponents of consolidation maintain that DOD is moving forward without considering the risk that consolidation could cost more than anticipated and fail to result in projected savings in operational costs.52 This could result in higher prices for patrons and curtail support for MWR programs. In the FY2019 NDAA, Congress authorized $1.3 billion for DeCA to operate 236 commissary stores on military installations worldwide, employing a workforce of over 12,500 civilian full-time equivalents (FTE).53

|

House-Passed H.R. 2500 |

Senate-Passed S.1790 |

|

Sec. 631 would require a Government Accountability Office (GAO) review of the defense resale optimization study. |

No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 632 would require the Secretary of Defense to submit a report to Congress on the management of commissaries and exchanges. |

No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 634 would require an extension of certain morale, welfare, and recreation privileges to Foreign Service officers on mandatory home leave. |

No similar provision. |

|

No similar provision. |

Sec. 641 would authorize a single Defense Resale System and would require the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness to coordinate with the DOD Chief Management Officer to maintain oversight of business transformation efforts and other matters. |

|

No similar provision. |

Sec. 642 would require treatment of fees on services provided as supplemental funds for commissary operations. |

|

No similar provision. |

Sec. 643 would require procurement by commissary stores of certain locally sourced products. |

Discussion: The House bill includes three sections relating to the DeCA. Section 631 of the House bill would require the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to review DOD's business case analysis (pricing, sales, measuring customer savings, timetable for consolidation, etc.) before merging the various resale entities into a single entity. Elements of the GAO report would include data on the financial viability of a single defense resale entity and the ability of commissaries and exchanges to support MWR programs after consolidation.

Section 632 would require a report to Congress by the Defense Secretary regarding the management practices of military commissaries and exchanges no later than 180 days after enactment. The report would include "a cost-benefit analysis with the goals of reducing the costs of operating military commissaries and exchanges by $2,000,000,000 during fiscal years 2020 through 2024" while not raising costs for patrons.

Section 634 would amend section 1065 of Title 10, U.S. Code, to extend MWR privileges to Foreign Service Officers on mandatory home leave effective January 1, 2020.

The Senate bill also includes three sections relating to DeCA; however, they differ from the House provisions. Section 641 would provide approval for a single Defense Resale System. This section would require the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness (USD [P&R]) to coordinate with the DOD Chief Management Officer to maintain oversight of the business transformation efforts to ensure: "(1) the development of a business strategy that maximizes efficiencies and results in a viable defense resale system in the future; (2) Preservation of patron savings and satisfaction from and in the defense commissary system and exchange stores system; and (3) Sustainment of financial support of the defense commissary and exchange systems for MWR services." This provision would also allow the merger to commence with no further GAO study.

Section 642 would require treatment of fees on services provided as supplemental funds for commissary operations. This would amend section 2483(c) of Title 10, U.S. Code, to authorize retention of fees collected by DeCA on services provided to secondary patron groups, such as DOD contractors living overseas, to offset commissary operating costs.

Section 643 would require commissary stores to procure locally sourced products such as dairy products, fruits, and vegetables as available.

References: CRS Report R45343, FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act: Selected Military Personnel Issues, section on "Defense Commissary System" and similar reports from earlier years; and CRS In Focus IF11089, Defense Primer: Military Commissaries and Exchanges, by Kristy N. Kamarck and Barbara Salazar Torreon.

CRS Point of Contact: Barbara Salazar Torreon.

Diversity and Inclusion

Background: Throughout the history of the Armed Forces, Congress has used its constitutional authority to establish criteria and standards for individuals to be recruited, advance through promotion, and be separated or retired from military service. Congress has established some of these criteria based on demographic characteristics such as race, sex, and sexual orientation. In the past few decades there have been rapid changes to certain laws and policies regarding diversity, inclusion, and equal opportunity – in particular authorizing women to serve in combat arms occupational specialties and the inclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals. Some of these changes remain contentious and face continuing legal challenges.

|

House-Passed H.R. 2500 |

Senate-Passed S. 1790 |

|

Sec. 526 would require the Secretary of Defense to update and implement the DOD Diversity and Inclusion Strategic Plan. |

No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 594 would require certain surveys to ask respondents about whether they have ever experienced supremacist activity, extremist activity, or racism. |

No similar provision. |

|

Section 530B would direct that eligibility requirements for entering military service account only for the ability of an individual to meet gender-neutral occupational standards without regard race, color, national origin, religion, and sex (including gender identity and sexual orientation). |

No similar provision. |

|

Section 597 would require DOD to submit a report on the number of waivers denied on the basis of a transgender-related condition. |

No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 561 would prohibit gender-segregated Marine Corps recruit training. |

No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 1099I would require each component to share lessons learned and best practices on progress of gender integration implementation. |

No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 1099J would require the military departments to examine strategies to recruit and retain women. |

No similar provision. |

Discussion: In the FY2009 NDAA (P.L. 110-417), Congress authorized the creation of the Military Leadership Diversity Commission (MLDC).54 Following that effort, in 2012 DOD developed and issued a five-year Diversity and Inclusion Strategic Plan.55 In 2013, as part of the FY2013 NDAA (P.L. 112-239), Congress required DOD to develop and implement a plan regarding diversity in military leadership.56 The House bill includes several provisions that would address diversity and inclusion, while the Senate bill has none. Section 526 of the current House bill would require DOD to design and implement a five-year strategic plan that is consistent with the 2018 National Military Strategy beginning on January 1, 2020.57

Existing law requires DOD to conduct surveys on racial and gender issues.58 Section 594 of the House bill would require that workplace and equal opportunity, command climate, and workplace and gender relations (WGR) surveys ask respondents whether they have ever experienced supremacist activity, extremist activity, racism, or anti-Semitism. DOD policy prohibits members from individually advocating for, or participating in, organizations that advocate for "supremacist, extremist, or criminal gang doctrine, ideology, or causes, including those that advance, encourage, or advocate illegal discrimination based on race, creed, color, sex, religion, ethnicity, or national origin or those that advance, encourage, or advocate the use of force, violence, or criminal activity or otherwise advance efforts to deprive individuals of their civil rights."59

Entry into the Armed Forces by enlistment or appointment (officers) requires applicants to meet certain physical, medical, mental, and moral standards. While some of these standards are specified in law (e.g., 10 U.S.C. §504), DOD and the Services generally establish these standards through policy and regulation. The Services may require additional qualification standards for entry into certain military occupational specialties (e.g., pilots, special operations forces). By law, qualification standards for military career designators are required to be gender-neutral.60 Section 530B would require that service entry standards account only for the ability of an individual to meet gender-neutral occupational standards and could not include any criteria relating to the "race, color, national origin, religion, or sex (including gender identity or sexual orientation) of an individual."61

DOD has recently initiated a number of shifts in policy with regard to individuals who identify as transgender. Current policy, which went into effect on April 12, 2019, disqualifies any individual from appointment, enlistment, or induction into the service if they have a history of cross-sex hormone therapy or sex reassignment or genital reconstruction surgery.62 The policy also disqualifies individuals with a history of gender dysphoria unless they were stable in their biological sex for 36 consecutive months prior to applying for admission into the Armed Forces.63 However, the policy allows for transgender persons to "seek waivers or exceptions to these or any other standards, requirements, or policies on the same terms as any other person."64 Those individuals in the service who initially seek military medical care after the effective date of the policy may receive counseling for gender dysphoria and may be retained without a waiver if (1) a military medical provider has determined that gender transition is not medically necessary to protect the health of the individual; and (2) the member is willing and able to adhere to all applicable standards associated with his or her biological sex. Section 597 of the House bill would require DOD to submit a report on the number of waivers denied on the basis of a transgender-related condition.

Women were historically prohibited from serving in certain combat roles by law and policy until December 3, 2015, when the Secretary of Defense opened all combat roles to women who can meet gender-neutral standards.65 Entry level and occupational-specific training has been gender integrated across the military services, with the exception of Marine Corps basic training (boot camp). In 2019, the Marines graduated the first gender-integrated boot camp class at Marine Recruit Depot Parris Island in South Carolina. In a statement to Congress, Lieutenant General David Berger noted that there were no significant variations in the performance of gender-integrated units relative to gender-segregated units.66 Section 561 of the House bill would prohibit gender segregated Marine Corps recruit training. In addition, section 1099I would require the Armed Forces components to share lessons learned and best practices on the progress of their gender integration implementation plans as recommended by the Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services (DACOWITS).67 Finally, section 1099J would require the military departments to examine successful strategies for recruitment and retention of women in foreign militaries, as recommended by DACOWITS.

References: CRS Report R44321, Diversity, Inclusion, and Equal Opportunity in the Armed Services: Background and Issues for Congress, by Kristy N. Kamarck, and CRS Insight IN11086, Military Personnel and Extremism: Law, Policy, and Considerations for Congress, by Kristy N. Kamarck. CRS In Focus IF11147, Defense Primer: Active Duty Enlisted Recruiting, by Lawrence Kapp.

CRS Points of Contact: Kristy N. Kamarck and Lawrence Kapp.

*Domestic Violence and Child Abuse

Background: The Family Advocacy Program (FAP) is the congressionally-mandated program within DOD devoted to "clinical assessment, supportive services, and treatment in response to domestic abuse and child abuse and neglect in military families."68 As required by law, the FAP provides an annual report to Congress on child abuse and neglect and domestic abuse in military families.69 Approximately half of military servicemembers are married and there are approximately 1.6 million dependent children across the active and reserve components.70 According to DOD statistics, in FY2018, the rate of reported child abuse or neglect in military homes was 13.9 per 1,000 children, an increase from the previous year's rate of 13.7 per 1,000 children.71 There were 26 child abuse-related fatalities, relative to 17 fatalities in FY2017. The rate of reported spousal abuse in FY2018 was 24.3 per 1,000 military couples, a decrease from the FY2017 rate of 24.5 per 1,000 couples – with 13 spouse abuse fatalities recorded.72 Since FY2006, DOD has been collecting data on unmarried intimate partner abuse. In FY2018, there were 1,024 incidents of intimate partner abuse that met criteria involving 822 victims and 2 fatalities.73

|

House-Passed H.R. 2500 |

Senate-Passed S. 1790 |

|

Sec. 542 would expand Special Victim Counsel (SVC) services for victims of domestic violence, establish minimum SVC staffing levels, would create a position for SVC paralegals, and would require a report to Congress on SVC staffing. |

Sec. 541 would allow the service secretaries to extend SVC services to certain military and military-affiliated civilian personnel who are alleged victims of domestic violence or a sex-related offense. |

|

Sec. 621 would remove delays in the commencement of transitional compensation for certain eligible military dependents. H. Report 116-120 Directs DOD to provide a comprehensive review and assessment of the transitional compensation program (p. 153). |

Sec. 601 is a similar provision to House Sec. 621. |

|

No similar provision. |

Sec. 581 would require a briefing to the Armed Services committees on ways the Family Advocacy Program (FAP) could be used/enhanced to prevent and respond to domestic violence. |

|

Sec. 543 would require notification of civilian authorities, and receiving units (in the case of a personnel transfer) when a member with a military protective order (MPO) against them is transferred to that unit, and would require annual reports to Congress on the number of MPOs reported to civilian authorities. |

No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 544 would require Secretary of Defense to enact policies and procedures to register civilian protection orders on military bases. |

Sec. 556 is an identical provision to House section 544. |

|

Sec. 550F would require reports to National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) for servicemembers who are prohibited from purchasing firearms and would require a study on the feasibility of creating a database for tracking domestic violence MPOs and reporting to NICS. |

No similar provision. |

Discussion: A special victim counsel (SVC) is a judge advocate or civilian attorney who satisfies special training requirements and provides legal assistance to victims of sexual assault throughout the military justice process.74 Section 542 of the House bill and Section 541 of the Senate bill would expand SVC staffing and authorize SVC services for military-connected victims of domestic violence. The Administration has opposed this measure, stating that it would "decrease access for sexual assault victims to Special Victims' Counsels (SVCs)/Victims' Legal Counsels (VLCs), exacerbate already high caseloads for SVC/VLCs, and impose an unfunded mandate."75

Transitional compensation is a monetary benefit authorized under 10 U.S.C. §1059 for dependent family members of servicemembers or of former servicemembers who are separated from the military due to dependent-abuse offenses. One of the motivating arguments for establishing the transitional compensation benefit is that it provides a measure of financial security to spouses or former spouses. Eligible recipients receive monthly payments for no less than 12 months and no more than 36 months at the same rate as dependency and indemnity compensation (DIC).76 While in receipt of transitional compensation, dependents are also entitled to military commissary and exchange benefits, and may receive dental and medical care, including mental health services, through military facilities as TRICARE beneficiaries.77 Section 621 of the House bill and Section 601 of the Senate bill are similar provisions that would expand the authority of the Secretary concerned to grant exceptional transitional compensation in an expedited fashion. This would allow dependents who are victims of abuse to start receiving compensation while the offending servicemember is still on active duty and as early as the date that an administrative separation is initiated by a commander. In addition, the House Report directs DOD to provide a comprehensive review and assessment of the transitional compensation program.78

When a servicemember has allegedly committed an act of domestic violence, a commander can issue a military protective order (MPO)79 to a servicemember that prohibits contact between the alleged offender and the domestic violence victim.80 A servicemember must obey an MPO at all times, whether inside or outside a military installation, or may be subject to court martial or other punitive measures. By law, a military installation commander is required to notify civilian authorities when an MPO is issued, changed, and terminated with respect to individuals who live outside of the installation.81 House Section 543 would amend 10 U.S.C. §1567a to require notification of civilian authorities no later than seven days after issuing an order, regardless of whether the member resides on the installation. The provision would also require commanders to notify the receiving command in the case of a transfer of an individual who has been issued an MPO. DOD would also be required to track and report the number of orders reported to civilian authorities annually. While MPOs are typically not enforceable by civilian authorities, a civil protection order (CPO), by law, has full force and effect on military installations.82 House Section 544 and Senate section 556 would require DOD to establish policies and procedures for registering CPOs with military installation authorities.

House Section 550F would codify an existing DOD policy to report to the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) servicemembers who are prohibited from purchasing firearms due to a domestic violence conviction in a military court.83 This section would also require DOD to study the feasibility of creating a database of military protective orders issued in response to domestic violence and the feasibility for reporting such MPOs to NICS.

References: For information on Special Victims' Counsel and Military Protective Orders, see CRS Report R44944, Military Sexual Assault: A Framework for Congressional Oversight, by Kristy N. Kamarck and Barbara Salazar Torreon.84

CRS Point of Contact: Kristy N. Kamarck and Alan Ott.

*Medal of Honor

Background: The Medal of Honor (MoH) is the highest award for valor "above and beyond the call of duty" that may be bestowed on a U.S. servicemember.85 In recent years, the MoH review process has been criticized by some as being lengthy and bureaucratic, which may have led to some records being lost and conclusions drawn based on competing eyewitness and forensic evidence.86 Reluctance on the part of reviewing officials to award the MoH retroactively or to upgrade other awards is generally based on concern for maintaining the integrity of the award and the awards process. This reluctance has led many observers to believe that the system of awarding the MoH is overly restrictive and that certain individuals are denied earned medals. As a result, DOD periodically reviews inquiries by Members of Congress and reevaluates its historical records. Systematic reviews began in the 1990s for World War II records when African-American units remained segregated and whose valorous unit and individuals' actions, along with others, may have been overlooked. That effort resulted in more than 100 soldiers receiving the MoH, the majority of which were posthumously awarded. On January 6, 2016, DOD announced the results of its year-long review of military awards and decorations.87 This included review of the timeliness of the MoH process and review by all the military departments of the Distinguished Service Cross, Navy Cross, Air Force Cross, and Silver Star Medal recommendations since September 11, 2001, for actions in Iraq and Afghanistan. Subsequently, the MoH was awarded to the first living recipient from the Iraq War, Army Staff Sgt. David Bellavia, on June 25, 2019.88

|

House-Passed H.R. 2500 |

Senate-Passed S. 1790 |

|

Sec. 583 would require a review of World War I valor medals. |

No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 584 would authorize the President of the United States to award the Medal of Honor (MoH) to Alwyn Cashe for acts of valor during Operation Iraqi Freedom. |

No similar provision |

|

Sec. 1099L would authorize the last surviving MoH recipient of Second World War, upon their death, to lay in state in the U.S. Capitol rotunda. |

No similar provision. |

|

No similar provision. |

Sec. 585 would authorize the President of the United States to award the MoH to John J. Duffy for acts of valor in Vietnam. |

Discussion: Section 583 of the House bill would require DOD to review the service records of certain servicemembers who fought in World War I (WWI) to determine whether they should be posthumously awarded the MoH. Specifically, the provision would require record reviews of certain African-American, Asian-American, Hispanic-American, Jewish-American, and Native-American veterans who were recommended for the MoH or who were the recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross, Navy Cross, or French Croix de Guerre with Palm. Four soldiers, one Hispanic-American (Private David Barkley Cantu) and three Jewish-American veterans (First Sergeant Sydney Gumpertz, First Sergeant Benjamin Kaufman, and Sergeant William Sawelson), were awarded Medals of Honor at the conclusion of WWI.

In 1991, President George H.W. Bush awarded the MoH posthumously to Corporal Freddie Stowers, who became the first African-American recipient from WWI after the Army's review of his military records. Later, the FY2015 NDAA (P.L. 113-291) authorized posthumous award of the MoH to Private Henry Johnson, an African-American veteran, and Sgt. William Shemin, a Jewish-American veteran, for valor during WWI.89 Proponents of the Pentagon review in Section 583 point to similar reviews for minority groups who served in other conflicts from World War II to the present. Some were later awarded the MoH, the majority of which were posthumously awarded. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), "a remote possibility exists" that one of the veterans honored under Section 583 could have a surviving widow who could potentially receive expanded health benefits or increased survivor benefits.90

Section 584 would waive the time limitation and authorize the posthumous award of the MoH to Army Sergeant First Class (SFC) Alwyn Cashe for acts of valor in Samarra, Iraq, during Operation Iraqi Freedom. SFC Cashe led recovery efforts and refused medical treatment until his men were evacuated to safety after an improvised explosive device struck their vehicle and caught fire. Cashe's actions saved the lives of six of his soldiers. He later succumbed to his wounds.

Section 1099L would allow the nation to honor the last surviving MoH recipient of WWII by permitting the individual to lie in honor in the Capitol rotunda upon death.

Section 585 of the Senate bill would waive the time limitation and authorize the award of the MoH to Army Major John J. Duffy for acts of valor in Vietnam on April 14 and 15, 1972, for which he was previously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

References: Previously discussed in the "Medal of Honor" section of CRS Report R44577, FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act: Selected Military Personnel Issues, by Kristy N. Kamarck et al. and similar reports from earlier years; CRS Report 95-519, Medal of Honor: History and Issues, by Barbara Salazar Torreon; and the Congressional Budget Office, Cost Estimates for H.R. 2500, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, June 19, 2019.

CRS Point of Contact: Barbara Salazar Torreon.

Military Family Issues

Background: Approximately 2.1 million members of the Armed Forces across the active and reserve components have an additional 2.7 million "dependent" family members (spouses and/or children).91 Slightly over 40% of servicemembers have children and approximately 50% are married.92 The military provides a number of quality of life programs and services for military families as part of a servicemember's total compensation and benefit package. These include family life, career, and financial counseling, childcare services and support, and other MWR activities. The general motivation for providing these benefits is to improve the recruitment, retention, and readiness of military servicemembers.

|

House-Passed H.R. 2500 |

Senate-Passed S. 1790 |

|

Spouse Employment and Education Sec. 628 would increase the maximum reimbursement to spouses for relicensing costs associated with a relocation. |

Spouse Employment and Education Sec. 576 would extend the authority to reimburse some relicensing costs associated with a military relocation. |

|

Sec. 624 would seek to improve portability of licenses for military spouses by allowing DOD to provide support for development of interstate compacts. |

Sec. 577 would require the Secretary of Defense to enter into a cooperative agreement with the Council of State Governments to assist with the funding and development of interstate compacts on licensed occupations. |

|

Sec. 623 would allow continued eligibility for the My Career Advancement Account Scholarship Program (MyCAA) program following the promotion of the sponsor. |

No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 580B would expand the types of associate degrees and certifications covered by MyCAA. |

No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 580C would expand MyCAA eligibility to Coast Guard spouses and spouses of enlisted servicemembers of all grades. |

No similar provision. |

|

Parents and Children Sec. 625 would amend 10 U.S.C. §1798 to authorize fee assistance for civilian childcare providers for survivors of members of the Armed Forces who die on active duty. |

Parents and Children No similar provision. |

|

No similar provision. |

Sec. 579 would clarify direct hiring authority for DOD child development centers. |

|

Sec. 629 would require an assessment of childcare costs, capacity, and website accessibility, enhance portability of provider background investigations, and expand direct hiring authority for childcare providers. |

No similar provision. |

Discussion: Spouse Employment and Education. Section 1784 of Title 10, U.S. Code, requires the President to order such measures as necessary to increase employment opportunities for military spouses. Active duty servicemembers conduct frequent moves to military installations across the globe. For working spouses, this sometimes requires them to establish employment in a new state that has different occupational licensing requirements than their previous state. The FY2018 NDAA (P.L. 115-91 §556) authorized the reimbursement of certain relicensing costs up to $500 for military spouses following a permanent change of station from one state to another with an end date of December 31, 2022.93 Section 628 of the House bill would raise the maximum reimbursement to $1,000 and would require the Secretary of Defense to perform an analysis of whether that amount is sufficient to cover average costs. Section 576 of the Senate bill would not raise the maximum reimbursement amount; however it would extend the authority to December 31, 2024. Both bills also have similar provisions (House Section 524 and Senate Section 577) that would seek to improve interstate license portability through DOD funding support for the development of interstate compacts. Both bills cap funding support for each compact at $1 million, while the Senate bill caps the total program funding at $4 million.

DOD's My Career Advancement Account Scholarship Program (MyCAA), launched in 2007, currently provides eligible military spouses up to $4,000 in financial assistance to pursue a license, certification, or associate's degree in a portable career field.94 Eligible spouses are those married to military servicemembers on active duty in pay grades E-1 to E-5, W-1 to W-2 and O-1 to O-2. Section 623 of the House bill would allow continued eligibility for spouses when the member is promoted above those pay grades after the spouse has begun a course of instruction. Section 580B would expand the qualifying degrees and certifications to include non-portable career fields and occupations. Finally, Section 580C would expand the eligible population to all enlisted spouses and would also provide eligibility for Coast Guard spouses to participate in the DOD program. During the pilot phase of the program, the benefit was offered to all spouses and funds were also available for a broader range of degrees and certifications, including bachelor's and advanced degrees. However, due to concerns about rising costs and enrollment requests, DOD has since reduced the maximum benefit amount (from $6,000 to $4000), limited eligibility to spouses of junior servicemembers, and restricted the types of degrees and career fields that were eligible for funding.95

Parents and Children. DOD operates the largest employer-sponsored childcare program in the United States, serving approximately 200,000 children of uniformed servicemembers and DOD civilians, and employing over 23,000 childcare workers.96 DOD offers subsidized programs on and off military installations for children from birth through 12 years, including care on a full-day, part-day, short-term, or intermittent basis. Title 10 U.S.C. §1798 authorizes fee assistance for civilian childcare services. Section 625 of the House bill would specifically authorize fee assistance for survivors of members of the Armed Forces who die "in line of duty while on active duty, active duty for training, or inactive duty for training.'' DOD policy currently authorizes childcare for "surviving spouses of military members who died from a combat related incident."97

Section 629 of the House bill and Section 578 of the Senate bill would expand and clarify hiring authorities for military childcare workers. The House provision would also require an assessment and report from DOD on the adequacy of the maximum fee assistance subsidy, the accessibility of childcare and spouse employment websites, and the capacity needs of installation-based childcare facilities. Finally, the same section would seek to improve portability of background checks for childcare workers. It is common for military spouses to be employed as childcare workers, and frequent moves may require them to reapply and resubmit background check material at a new facility.

References: CRS Report R45288, Military Child Development Program: Background and Issues, by Kristy N. Kamarck.

CRS Points of Contact: Kristy N. Kamarck.

Military Medical Malpractice

Background: DOD employs physicians and other medical personnel to deliver health care services to servicemembers in military treatment facilities (MTFs). Occasionally, however, patient safety events do occur and providers commit medical malpractice by rendering health care in a negligent fashion, resulting in the servicemember's injury or death.98 In the civilian health care market, a victim of medical malpractice may potentially obtain recourse by pursuing litigation against the negligent provider and/or his employer. A servicemember injured as a result of malpractice committed by an MTF health care provider, however, may encounter significant obstacles if attempting to sue the United States.

In general, the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA) permits private parties to pursue certain tort claims (e.g., medical malpractice) against the United States.99 However, in 1950, the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of Feres v. United States recognized an implicit exception to the FTCA–that the federal government is immunized from liability "for injuries to servicemen where the injuries arise out of or are in the course of activity incident to service."100 This exception to tort liability is known as the Feres doctrine. Many lower federal courts have concluded that Feres generally prohibits military servicemembers from asserting malpractice claims against the United States based on the negligent actions of health care providers employed by the military.

|

House-Passed H.R. 2500 |

Senate-Passed S. 1790 |

|

Sec. 729 would amend the Federal Tort Claims Act (28 U.S.C. §2681) to allow certain claims against the United States for negligent, wrongful, or omitted health care services at a military treatment facility that resulted in personal injury or death of a servicemember. |

No similar provision. |

|

Sec. 744 would require the Secretary of Defense to report to Congress the number of medical providers who "lost medical malpractice insurance coverage" prior to their employment with DOD. |

No similar provision. |

Discussion: Over the past decade, Congress has held multiple hearings to assess whether to modify the Feres doctrine to allow servicemembers to pursue medical malpractice litigation against the United States.101 Congress has also considered several proposals to amend the FTCA to allow these tort claims.102 Section 729 of the House bill would amend the FTCA to allow servicemembers to pursue tort claims against the United States for medical malpractice committed by an MTF provider. The provision would also institute a three-year statute of limitations for a servicemember to file a claim, based on the date the malpractice was discovered and would clarify that any malpractice claims filed would not impact certain monetary compensation provided through the Servicemembers' Group Life Insurance.103

References: CRS In Focus IF11102, Military Medical Malpractice and the Feres Doctrine, by Bryce H. P. Mendez and Kevin M. Lewis; and CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10305, The Feres Doctrine: Congress, the Courts, and Military Servicemember Lawsuits Against the United States, by Kevin M. Lewis.

CRS Point of Contact: Bryce H.P. Mendez.

*Military Pay Raise