Introduction

The 116th Congress may consider a variety of housing-related issues. These may involve assisted housing programs, such as those administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and issues related to housing finance, among other things. Specific topics of interest may include ongoing issues such as interest in reforming the nation's housing finance system, how to prioritize appropriations for federal housing programs in a limited funding environment, oversight of the implementation of changes to certain housing programs that were enacted in prior Congresses, and the possibility of extending certain temporary housing-related tax provisions. Additional issues may emerge as the Congress progresses.

This report provides a high-level overview of the most prominent housing-related issues that may be of interest during the 116th. It is meant to provide a broad overview of major issues and is not intended to provide detailed information or analysis. However, it includes references to more in-depth CRS reports on these issues where possible.

Housing and Mortgage Market Conditions

This section provides background on housing and mortgage market conditions to provide context for the housing policy issues discussed in the remainder of the report. This discussion of market conditions is at the national level. However, it is important to be aware that local housing market conditions can vary dramatically, and national housing market trends may not reflect the conditions in a specific area. Nevertheless, national housing market indicators can provide an overall sense of general trends in housing.

In general, rising home prices, relatively low interest rates, and rising rental costs have been prominent features of housing and mortgage markets in recent years. Although interest rates have remained low, rising house prices and rental costs that in many cases have outpaced income growth have led to increased concerns about housing affordability for both prospective homebuyers and renters.

Owner-Occupied Housing Markets and the Mortgage Market

Most homebuyers take out a mortgage to purchase a home. Therefore, owner-occupied housing markets and the mortgage market are closely linked, although they are not the same. The ability of prospective homebuyers to obtain mortgages, and the costs of those mortgages, impact housing demand and affordability. The following subsections show current trends in selected owner-occupied housing and mortgage market indicators.

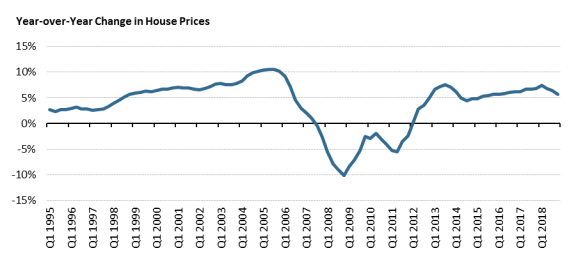

House Prices

As shown in Figure 1, nationally, nominal house prices have been increasing on a year-over-year basis in each quarter since the beginning of 2012, with year-over-year increases exceeding 5% for much of that time period and exceeding 6% for most quarters since mid-2016. These increases follow almost five years of house price declines in the years during and surrounding the economic recession of 2007-2009 and associated housing market turmoil. House price increases slowed somewhat during 2018, but year-over-year house prices still increased by nearly 6% during the fourth quarter of 2018.

House prices, and changes in house prices, vary greatly across local housing markets. Some areas of the country are experiencing rapid increases in house prices, while other areas are experiencing slower or stagnating house price growth. Similarly, prices have fully regained or even exceeded their pre-recession levels in nominal terms in many parts of the country, but in other areas prices remain below those levels.1

House price increases affect participants in the housing market differently. Rising prices reduce affordability for prospective homebuyers, but they are generally beneficial for current homeowners due to the increased home equity that accompanies them (although rising house prices also have the potential to negatively impact affordability for current homeowners through increased property taxes).

Interest Rates

For several years, mortgage interest rates have been low by historical standards. Lower interest rates increase mortgage affordability and make it easier for some households to purchase homes or refinance their existing mortgages.

As shown in Figure 2, average mortgage interest rates have been consistently below 5% since May 2010 and have been below 4% for several stretches during that time. After starting to increase somewhat in late 2017 and much of 2018, mortgage interest rates showed declines at the end of 2018 into early 2019. The average mortgage interest rate for February 2019 was 4.37%, compared to 4.46% in the previous month and 4.33% a year earlier.

|

Figure 2. Mortgage Interest Rates January 1995–February 2019 |

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS based on data from Freddie Mac's Primary Mortgage Market Survey, 30-Year Fixed Rate Historic Tables, available athttp://www.freddiemac.com/pmms/. Notes: Freddie Mac surveys lenders on the interest rates they are charging for certain types of mortgage products. The actual interest rate paid by any given borrower will depend on a number of factors. |

Homeownership Affordability

House prices have been rising for several years on a national basis, and mortgage interest rates, while still low by historical standards, have also risen for certain stretches. While incomes have also been rising in recent years, helping to mitigate some affordability pressures, on the whole house price increases have outpaced income increases.2 These trends have led to increased concerns about the affordability of owner-occupied housing.

Despite rising house prices, many metrics of housing affordability suggest that owner-occupied housing is currently relatively affordable.3 These metrics generally measure the share of income that a median-income family would need to qualify for a mortgage to purchase a median-priced home, subject to certain assumptions. Therefore, rising incomes and, especially, interest rates that are still low by historical standards contribute to monthly mortgage payments being considered affordable under these measures despite recent house price increases.

However, some factors that affect housing affordability may not be captured by these metrics. For example, several of the metrics are based on certain assumptions (such as a borrower making a 20% down payment) that may not apply to many households. Furthermore, because they typically measure the affordability of monthly mortgage payments, they often do not take into account other affordability challenges that homebuyers may face, such as affording a down payment and other upfront costs of purchasing a home (costs that generally increase as home prices rise). Other factors—such as the ability to qualify for a mortgage, the availability of homes on the market, and regional differences in house prices and income—may also make homeownership less attainable for some households.4 Some of these factors may have a bigger impact on affordability for specific demographic groups, as income trends and housing preferences are not uniform across all segments of the population.5

Given that house price increases are showing some signs of slowing and interest rates have remained low, the affordability of owner-occupied homes may hold steady or improve. Such trends could potentially impact housing market activity, including home sales.

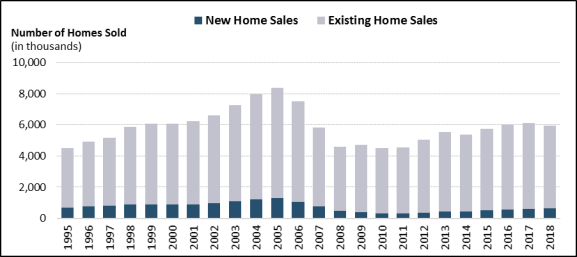

Home Sales

In general, annual home sales have been increasing since 2014 and have improved from their levels during the housing market turmoil of the late 2000s, although in 2018 the overall number of home sales declined from the previous year. While home sales have been improving somewhat in recent years (prior to falling in 2018), the supply of homes on the market has generally not been keeping pace with the demand for homes, thereby limiting home sales activity and contributing to house price increases.

Home sales include sales of both existing and newly built homes. Existing home sales generally number in the millions each year, while new home sales are usually in the hundreds of thousands. Figure 3 shows the annual number of existing and new home sales for each year from 1995 through 2018. Existing home sales numbered about 5.3 million in 2018, a decline from 5.5 million in 2017 (existing home sales in 2017 were the highest level since 2006). New home sales numbered about 622,000 in 2018, an increase from 614,000 in 2017 and the highest level since 2007. However, the number of new home sales remains appreciably lower than in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when they tended to be between 800,000 and 1 million per year.

|

Figure 3. New and Existing Home Sales Annual, 1995–2018 |

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS using data from HUD's U.S. Housing Market Conditions reports, available at https://www.huduser.gov/portal/ushmc/home.html, which use data from the National Association of Realtors for existing home sales and the U.S. Census Bureau for new home sales. |

Housing Inventory and Housing Starts

The number and types of homes on the market affect home sales and home prices. On a national basis, the supply of homes on the market has been relatively low in recent years,6 and in general new construction has not been creating enough new homes to meet demand.7 However, as noted previously, national housing market indicators are not necessarily indicative of local conditions. While many areas of the country are experiencing low levels of housing inventory that contribute to higher home prices, other areas, particularly those experiencing population declines, face a different set of housing challenges, including surplus housing inventory and higher levels of vacant homes.8

On a national basis, the inventory of homes on the market has been below historical averages in recent years, though the inventory, of new homes in particular, has begun to increase somewhat of late.9 Homes come onto the market through the construction of new homes and when current homeowners decide to sell their existing homes. Existing homeowners' decisions to sell their homes can be influenced by expectations about housing inventory and affordability. For example, current homeowners may choose not to sell if they are uncertain about finding new homes that meet their needs, or if their interest rates on new mortgages would be substantially higher than the interest rates on their current mortgages. New construction activity is influenced by a variety of factors including labor, materials, and other costs as well as the expected demand for new homes.

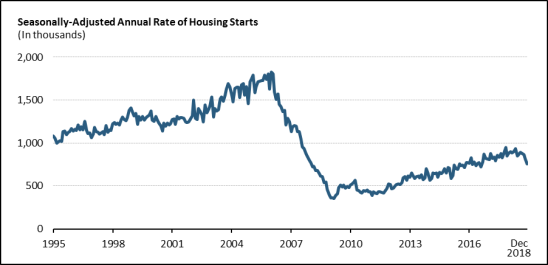

One measure of the amount of new construction is housing starts. Housing starts are the number of new housing units on which construction is started in a given period and are typically reported monthly as a "seasonally adjusted annual rate." This means that the number of housing starts reported for a given month (1) has been adjusted to account for seasonal factors and (2) has been multiplied by 12 to reflect what the annual number of housing starts would be if the current month's pace continued for an entire year.10

Figure 4 shows the seasonally adjusted rate of starts on one-unit homes for each month from January 1995 through December 2018.11 Housing starts for single-family homes fell during the housing market turmoil, reflecting decreased home purchase demand. In recent years, levels of new construction have remained relatively low by historical standards, reflecting a variety of considerations including labor shortages and the cost of building.12 Housing starts have generally been increasing since about 2012, but remain well below their levels from the late 1990s through the mid-2000s. For 2018, the seasonally adjusted annual rate of housing starts averaged about 868,000. In comparison, the seasonally adjusted annual rate of housing starts exceeded 1 million from the late 1990s through the mid-2000s.

|

By month; seasonally adjusted annual rate |

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS using data from the U.S. Census Bureau, New Residential Construction Historical Data, http://www.census.gov/construction/nrc/historical_data/. Data are through December 2018. Notes: Figure reflects starts in one-unit structures only, some of which may be built for rent rather than sale. The seasonally adjusted annual rate is the number of housing starts that would be expected if the number of homes started in that month (on a seasonally adjusted basis) were extrapolated over an entire year. |

Furthermore, high housing construction costs have led to a greater share of new housing being built at the more expensive end of the market. To the extent that new homes are concentrated at higher price points, supply and price pressures may be exacerbated for lower-priced homes.13

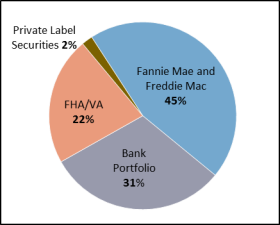

Mortgage Market Composition

When a lender originates a mortgage, it can choose to hold that mortgage in its own portfolio, sell it to a private company, or sell it to Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, two congressionally chartered government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs). Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac bundle mortgages into securities and guarantee investors' payments on those securities. Furthermore, a mortgage might be insured by a federal government agency, such as the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) or the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Most FHA-insured or VA-guaranteed mortgages are included in mortgage-backed securities that are guaranteed by Ginnie Mae, another government agency.14 The shares of mortgages that are provided through each of these channels may be relevant to policymakers because of their implications for mortgage access and affordability as well as the federal government's exposure to risk.

As shown in Figure 5, during the first three quarters of 2018, about two-thirds of the total dollar volume of mortgages originated was either backed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac (45%) or guaranteed by a federal agency such as FHA or VA (22%). Nearly one-third of the dollar volume of mortgages originated was held in bank portfolios, while close to 2% was included in a private-label security without government backing.

The shares of mortgage originations backed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and held in bank portfolios are roughly similar to their respective shares in the early 2000s. The share of private-label securitization has been, and continues to be, very small since the housing market turmoil of the late 2000s, while the FHA/VA share is higher than it was in the early and mid-2000s.15 The share of mortgages insured by FHA or guaranteed by VA was low by historical standards during that time period as many households opted for other types of mortgages, including subprime mortgages.

Rental Housing Markets

As has been the case in owner-occupied housing markets, affordability has been a prominent concern in rental markets in recent years. In the years since the housing market turmoil of the late 2000s, the number and share of renter households has increased, leading to lower rental vacancy rates and higher rents in many markets.

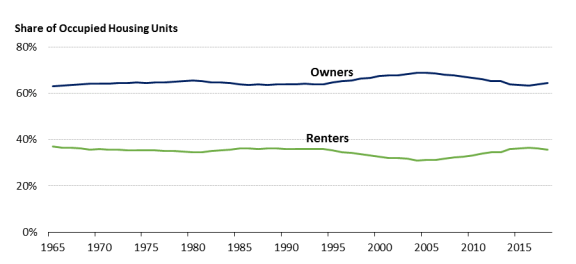

Share of Renters

The housing and mortgage market turmoil of the late 2000s led to a substantial decrease in the homeownership rate and a corresponding increase in the share of households who rent their homes. As shown in Figure 6, the share of renters increased from about 31% in 2005 and 2006 to a high of about 36.6% in 2016, before decreasing slightly to 36.1% in 2017 and continuing to decline to 35.6% in 2018. The homeownership rate correspondingly fell from a high of 69% in the mid-2000s to 63.4% in 2016, before rising to 63.9% in 2017 and continuing to rise to 64.4% in 2018.16

The overall number of occupied housing units also increased over this time period, from nearly 110 million in 2006 to 121 million in 2018; most of this increase has been in renter-occupied units.17 The number of renter-occupied units increased from about 34 million in 2006 to about 43 million in 2018. The number of owner-occupied housing units fell from about 75 million units in 2006 to about 74 million in 2014, but has since increased to about 78 million units in 2018.

Rental Vacancy Rates

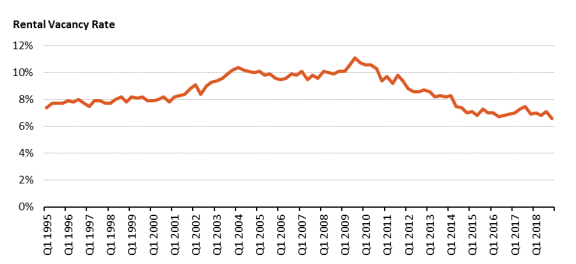

The higher number and share of renter households has had implications for rental vacancy rates and rental housing costs. More renter households increases competition for rental housing, which may in turn drive up rents if there is not enough new rental housing created (whether through new construction or conversion of owner-occupied units to rental units) to meet the increased demand.

As shown in Figure 7, the rental vacancy rate has generally declined in recent years and was under 7% at the end of 2018.

|

Figure 7. Rental Vacancy Rates Q1 1995–Q4 2018 |

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS based on data from U.S. Census Bureau, Housing Vacancies and Homeownership Historical Tables, Table 1, "Quarterly Rental Vacancy Rates: 1956 to Present," http://www.census.gov/housing/hvs/data/histtabs.html. |

Rental Housing Affordability

Rental housing affordability is impacted by a variety of factors, including the supply of rental housing units available, the characteristics of those units (e.g., age and amenities), and the demand for available units. New housing units have been added to the rental stock in recent years through both construction of new rental units and conversions of existing owner-occupied units to rental housing. However, the supply of rental housing has not necessarily kept pace with the demand, particularly among lower-cost rental units, and low vacancy rates have been especially pronounced in less-expensive units.18

The increased demand for rental housing, as well as the concentration of new rental construction in higher-cost units, has led to increases in rents in recent years. Median renter incomes have also been increasing for the last several years, at times outpacing increases in rents. However, over the longer term, median rents have increased faster than renter incomes, reducing rental affordability.19

Rising rental costs and renter incomes that are not keeping up with rent increases over the long term can contribute to housing affordability problems, particularly for households with lower incomes. Under one common definition, housing is considered to be affordable if a household is paying no more than 30% of its income in housing costs. Under this definition, households that pay more than 30% are considered to be cost-burdened, and those that pay more than 50% are considered to be severely cost-burdened.

The overall number of cost-burdened renter households has increased from 14.8 million in 2001 to 20.5 million in 2017, although the 20.5 million in 2017 represented a decrease from 20.8 million in 2016 and over 21 million in 2014 and 2015.20 (Over this time period, the overall number of renter households has increased as well.) While housing cost burdens can affect households of all income levels, they are most prevalent among the lowest-income households. In 2017, 83% of renter households with incomes below $15,000 experienced housing cost burdens, and 72% experienced severe cost burdens.21 A shortage of lower-cost rental units that are both available and affordable to extremely low-income renter households (households that earn no more than 30% of area median income), in particular, contributes to these cost burdens.22

Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

A variety of housing-related issues may be of interest to the 116th Congress, including housing finance, housing assistance programs, and housing-related tax provisions, among other things. Many of these are ongoing or perennial housing-related issues, though additional issues may emerge as the Congress progresses.

Status of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

Two major players in the U.S. housing finance system are Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) that were created by Congress to provide liquidity to the mortgage market. By law, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac cannot make mortgages; rather, they are restricted to purchasing mortgages that meet certain requirements from lenders. Once the GSEs purchase a mortgage, they either package it with others into a mortgage-backed security (MBS), which they guarantee and sell to institutional investors (which can be the mortgage originator),23 or retain it as a portfolio investment. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are involved in both single-family and multifamily housing, though their single-family businesses are much larger.

In 2008, in the midst of housing and mortgage market turmoil, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac experienced financial trouble and entered voluntary conservatorship overseen by their regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA). As part of the legal arrangements of this conservatorship, the Department of the Treasury contracted to purchase a maximum of $200 billion of new senior preferred stock from each of the GSEs; in return for this support, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac pay dividends on this stock to Treasury.24 These funds become general revenues.

Several issues related to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac could be of interest to the 116th Congress. These include the potential for legislative housing finance reform, new leadership at FHFA and the potential for administrative changes to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and certain issues that could affect Fannie Mae's and Freddie Mac's finances and mortgage standards, respectively.

For more information on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, see CRS Report R44525, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in Conservatorship: Frequently Asked Questions.

Potential for Legislative Housing Finance Reform

Since Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac entered conservatorship in 2008, policymakers have largely agreed on the need for comprehensive housing finance reform legislation that would resolve the conservatorships of these GSEs and address the underlying issues that are perceived to have led to their financial trouble and conservatorships. Such legislation could eliminate Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, possibly replacing them with other entities; retain the companies but transform their role in the housing finance system; or return them to their previous status with certain changes. In addition to addressing the role of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, housing finance reform legislation could potentially involve changes to the Federal Housing Administration (FHA)25 or other federal programs that support the mortgage market.

While there is generally broad agreement on certain principles of housing finance reform—such as increasing the private sector's role in the mortgage market, reducing government risk, and maintaining access to affordable mortgages for creditworthy households—there is disagreement over how best to achieve these objectives and over the technical details of how a restructured housing finance system should operate. Since 2008, a variety of housing finance reform proposals have been put forward by Members of Congress, think tanks, and industry groups.26 Proposals differ on structural questions as well as on specific implementation issues, such as whether, and how, certain affordable housing requirements that currently apply to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac would be included in a new system.

Previous Congresses have considered housing finance reform legislation in varying degrees. In the 113th Congress, the House Committee on Financial Services and Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs considered different versions of comprehensive housing finance reform legislation, but none were ultimately enacted.27 The 114th Congress considered a number of more-targeted reforms to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, but did not actively consider comprehensive housing finance reform legislation.28 At the end of the 115th Congress, the House Committee on Financial Services held a hearing on a draft housing finance reform bill released by then-Chairman Jeb Hensarling and then-Representative John Delaney, but no further action was taken on it.29

In the 116th Congress, Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Chairman Mike Crapo has released an outline for potential housing finance reform legislation.30 The committee held hearings on March 26 and March 27, 2019 on the outline.31

New FHFA Director and Possible Administrative Changes to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

FHFA, an independent agency, is the regulator for Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Home Loan Bank System as well as the conservator for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The director of FHFA is appointed by the President, subject to Senate confirmation, for a five-year term. The term of FHFA Director Mel Watt expired in January 2019. President Trump nominated Mark Calabria to be the next FHFA director. The Senate confirmed the nomination on April 4, 2019, and Dr. Calabria was sworn in on April 15, 2019.

FHFA has relatively wide latitude to make many changes to Fannie Mae's and Freddie Mac's operations without congressional approval, though it is subject to certain statutory constraints. In recent years, for example, FHFA has directed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to engage in risk-sharing transactions, develop a common securitization platform for issuing mortgage-backed securities, and undertake certain pilot programs.32 The prospect of new leadership at FHFA led many to speculate about possible administrative changes that FHFA could make to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac going forward.33 Any such changes could potentially lead to congressional interest and oversight.

FHFA could make many changes to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, including changes to the pricing of mortgages they purchase, to their underwriting standards, or to certain product offerings. It could also make changes to pilot programs, start laying the groundwork for a post-conservatorship housing finance system, or take a different implementation approach to certain affordable housing initiatives required by statute, such as Duty to Serve requirements.34 Because the new FHFA director has been critical of certain aspects of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in the past, some have expressed concerns that the new leadership could result in the agency taking steps to reduce Fannie Mae's and Freddie Mac's role in the mortgage market.35

In March 2019, nearly 30 industry groups sent a letter to Acting Director Otting urging that FHFA proceed cautiously with any administrative changes to ensure that they do not disrupt the mortgage market.36 That same month, President Trump issued a memorandum directing the Secretary of the Treasury to work with other executive branch agencies to develop a plan to end the GSEs' conservatorship, among other goals.

Other Issues Related to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

Certain other issues related to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac may be of interest during the 116th Congress. A new accounting standard (current expected credit loss, or CECL) that could require the GSEs to increase their loan loss reserves goes into effect in 2020.37 CECL could result in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac needing to draw on their support agreements with Treasury.

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 111-203) requires mortgage lenders to document and verify a borrower's ability to repay (ATR). If a mortgage lacks certain risky features and a lender complies with the ATR regulations, the mortgage is considered to be a qualified mortgage (QM), which provides the lender certain protections against lawsuits claiming that the ATR requirements were not met. Mortgages purchased by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac currently have an exemption (known as the QM Patch) from the debt-to-income ratio ATR rule. This exemption expires in early 2021 (or earlier if Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac exit conservatorship before that date).38

Housing Assistance

Appropriations for Housing Programs

For several years, concern in Congress about federal budget deficits has led to increased interest in reducing the amount of discretionary funding provided each year through the annual appropriations process. This interest manifested most prominently in the enactment of the Budget Control Act of 2011(P.L. 112-25), which set enforceable limits for both mandatory and discretionary spending.39 The limits on discretionary spending, which have been amended and adjusted since they were first enacted,40 have implications for HUD's budget, the largest source of funding for direct housing assistance, because it is made up almost entirely of discretionary appropriations.41 In FY2020, the discretionary spending limits are slated to decrease, after having been increased in FY2018 and FY2019 by the Bipartisan Budget Act of FY2018 (BBA; P.L. 115-123). The nondefense discretionary cap (the one relevant for housing programs and activities) will decline by more than 9% in FY2020, absent any additional legislative changes.42

More than three-quarters of HUD's appropriations are devoted to three rental assistance programs serving more than 4 million families: the Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program, Section 8 project-based rental assistance, and the public housing program. Funding for the HCV program and project-based rental assistance has been increasing in recent years, largely because of the increased costs of maintaining assistance for households that are currently served by the programs.43 Public housing has, arguably, been underfunded (based on studies undertaken by HUD of what it should cost to operate and maintain it) for many years.44 Despite the large share of total HUD funding these rental assistance programs command, their combined funding levels only permit them to serve an estimated one in four eligible families, which creates long waiting lists for assistance in most communities.45 A similar dynamic plays out in the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Rural Housing Service budget. Demand for housing assistance exceeds the supply of subsidies, yet the vast majority of the RHS budget is devoted to maintaining assistance for current residents.46

In a budget environment with limits on discretionary spending, the pressure to provide increased funding to maintain current services for existing rental assistance programs must be balanced against the pressure from states, localities, and advocates to maintain or increase funding for other popular programs, such as HUD's Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program, grants for homelessness assistance, and funding for Native American housing.

FY2020 Budget

The Trump Administration's budget request for FY2020 proposes an 18% decrease in funding for HUD's programs and activities as compared to the prior year.47 It proposes to eliminate funding for several programs, including multiple HUD grant programs (CDBG, the HOME Investment Partnerships Program, and the Self-Help and Assisted Homeownership Opportunity Program (SHOP)), and to decrease funding for most other HUD programs. In proposing to eliminate the grant programs, the Administration cites budget constraints and proposes that state and local governments take on more of a role in the housing and community development activities funded by these programs. Additionally, the budget references policy changes designed to reduce the cost of federal rental assistance programs, including the Making Affordable Housing Work Act of 2018 (MAHWA) legislative proposal, released by HUD in April 2018.48 If enacted, the proposal would make a number of changes to the way tenant rents are calculated in HUD rental assistance programs, resulting in rent increases for assisted housing recipients, and corresponding decreases in the cost of federal subsidies. Further, it would permit local program administrators or property owners to institute work requirements for recipients. In announcing the proposal, HUD described it as setting the programs on "a more fiscally sustainable path," creating administrative efficiency, and promoting self-sufficiency.49 Low-income housing advocates have been critical of it, particularly the effect increased rent payments may have on families.50

Beyond HUD, the Administration's FY2020 budget request for USDA's Rural Housing Service would eliminate funding for most rural housing programs, except for several loan guarantee programs. It would continue to provide funding to renew existing rental assistance, but also proposes a new minimum rent policy for tenants designed to help reduce federal subsidy costs.

For more on HUD appropriations trends in general, see CRS Report R42542, Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD): Funding Trends Since FY2002. For more on the FY2020 budget environment, including discretionary spending caps, see CRS Report R44874, The Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions.

Implementation of Housing Assistance Legislation

Several pieces of assisted housing legislation that were enacted in prior Congresses are expected to be implemented during the 116th Congress.

Moving to Work (MTW) Expansion

In the FY2016 HUD appropriations law, Congress mandated that HUD expand the Moving to Work (MTW) demonstration by 100 public housing authorities (PHAs).51 MTW is a waiver program that allows a limited number of participating PHAs to receive exceptions from HUD for most of the rules and regulations governing the public housing and voucher programs. MTW has been controversial for many years, with PHAs supporting the flexibility it provides (e.g., allowing PHAs to move funding between programs), and low-income housing advocates criticizing some of the policies being adopted by PHAs (e.g., work requirements and time limits). Most recently, GAO issued a report raising concerns about HUD's oversight of MTW, including the lack of monitoring of the effects of policy changes under MTW on tenants.52

HUD was required to phase in the FY2016 expansion and evaluate any new policies adopted by participating PHAs. Following a series of listening sessions and advisory committee meetings, and several solicitations for comment, HUD issued a solicitation of interest for the first two expansion cohorts in December 2018. As of the date of this report, no selections had yet been made for those cohorts.53

Rental Assistance Demonstration Expansion

The Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) was an Obama Administration initiative initially designed to test the feasibility of addressing the estimated $25.6 billion backlog in unmet capital needs in the public housing program54 by allowing local PHAs to convert their public housing properties to either Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers or Section 8 project-based rental assistance.55 PHAs are limited in their ability to mortgage, and thus raise private capital for, their public housing properties because of a federal deed restriction placed on the properties as a condition of federal assistance. When public housing properties are converted under RAD, that deed restriction is removed.56 As currently authorized, RAD conversions must be cost-neutral, meaning that the Section 8 rents the converted properties may receive must not result in higher subsidies than would have been received under the public housing program. Given this restriction, and without additional subsidy, not all public housing properties can use a conversion to raise private capital, potentially limiting the usefulness of a conversion for some properties.57 While RAD conversions have been popular with PHAs,58 and HUD's initial evaluations of the program have been favorable,59 a recent GAO study has raised questions about HUD's oversight of RAD, and about how much private funding is actually being raised for public housing through the conversions.60

RAD, as first authorized by Congress in the FY2012 HUD appropriations law, was originally limited to 60,000 units of public housing (out of roughly 1 million units).61 However, Congress has since expanded the demonstration. Most recently, in FY2018, Congress raised the cap so that up to 455,000 units of public housing will be permitted to convert to Section 8 under RAD, and it further expanded the program so that Section 202 Housing for the Elderly units can also convert. Not only is HUD currently implementing the FY2018 expansion, but the President's FY2020 budget request to Congress requests that the cap on public housing RAD conversions be eliminated completely.62

Selected Administrative Actions Related to Affordable Housing

HUD Noncitizen Eligibility and Documentation Proposed Rule

On May 10, 2019, HUD released a proposed rule to end eligibility for "mixed status" families in its major rental assistance programs (public housing, Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers, Section 8 project-based rental assistance).63 Mixed status families comprise both citizens (or eligible noncitizens) and ineligible noncitizens. Under current HUD regulations, mixed status families are eligible to receive prorated assistance, meaning that the household can receive federal housing assistance but their benefit must be reduced proportionally to avoid assisting ineligible noncitizens (generally, nonimmigrants such as those in the country illegally as well as those with temporary status, such as tourists and students). Additionally, the proposed rule would establish new requirements that citizens provide documentation of their citizenship status.64 (For more information, see CRS Insight IN11121, HUD's Proposal to End Assistance to Mixed Status Families.)

Low-income housing advocates65 and stakeholder groups representing program administrators66 have publicly opposed the proposed rule change, citing its potential disruptive effect on the roughly 25,000 currently assisted mixed status families, as well as the increases in both subsidy costs (estimated at $200 million per year by HUD) and administrative costs it would cause. Legislative language to block implementation of the rule was included in the House-passed FY2020 HUD appropriations bill (Section 234 of Division E of H.R. 3055); H.R. 2763, as ordered reported by the House Financial Services Committee; and S. 1904, as introduced in the Senate.

Equal Access to Housing

In the spring of 2019, as part of the Unified Agenda of Federal Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions published by OMB, HUD announced that it would release a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) in the fall of 2019 that would make changes to its Equal Access to Housing rule.67 HUD initially published an Equal Access to Housing rule in 2012, stating that housing provided through HUD programs must be made available regardless of a person's sexual orientation, gender identity, or marital status.68 Another Equal Access to Housing rule—specifically targeted to HUD Community Planning and Development (CPD) programs, where funding can be used to fund shelters for people experiencing homelessness—was published in 2016.69 The 2016 Equal Access to Housing rule requires that placement in facilities with shared sleeping and/or bath accommodations occur in conformance with a person's gender identity.

HUD states that the forthcoming NPRM would allow CPD program grant recipients and shelter operators to determine how people experiencing homelessness are admitted to sex-segregated shelters. Among the factors that could be considered are "privacy, safety, practical concerns, religious beliefs, any relevant considerations under civil rights and nondiscrimination authorities, the individual's sex as reflected in official government documents, as well as the gender which a person identifies with."

Legislation to prohibit HUD from implementing a rule based on the proposal published in the Unified Agenda passed the House Financial Services Committee on June 11, 2019. (See the Ensuring Equal Access to Shelter Act of 2019, H.R. 3018.) In addition, the FY2020 House-passed HUD appropriations bill (Section 236 of Division E of H.R. 3055) would prevent HUD from making changes to either the 2012 or 2016 Equal Access to Housing rules.

For more information about the Equal Access to Housing rules, see CRS Report R44557, The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities.

Regulatory Barriers Council

On June 25, 2019, President Trump signed an Executive Order establishing a White House Council on Eliminating Regulatory Barriers to Affordable Housing.70 The council is to be chaired by the HUD Secretary, but will include members from eight federal agencies. The council is charged with assessing federal, state, and local regulations and the effect they are having on developing new affordable housing; taking action to reduce federal regulatory barriers; and supporting state and local efforts to reduce regulatory barriers.

Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing

The Fair Housing Act requires HUD to administer its programs in a way that affirmatively furthers fair housing.71 In addition, statutes or regulations governing specific HUD programs require that funding recipients affirmatively further fair housing (AFFH). On July 16, 2015, HUD published a final rule (AFFH rule) that more specifically defined what it means to affirmatively further fair housing, and required that local communities and Public Housing Authorities receiving HUD funding assess the needs of their communities and ways in which they could improve access to housing.

After the AFFH rule began to be implemented, on May 23, 2018, HUD effectively suspended its implementation. Several months later, on August 13, 2018, HUD announced an Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking stating that it "has determined that a new approach towards AFFH is required" and requesting public comments on potential changes to the AFFH regulations.72 HUD has not yet released a proposed rule.

For more information about the AFFH rule, see CRS Report R44557, The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities.

Housing and Disaster Response

Several major disasters that have recently affected the United States have led to congressional activity related to disaster response and recovery programs.73 When such incidents occur, the President may authorize an emergency or major disaster declaration74 under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (Stafford Act; P.L. 93-288, as amended),75 making various housing assistance programs, including programs provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), available to disaster survivors. FEMA-provided housing assistance may include short-term, emergency sheltering accommodations under Section 403—Essential Assistance—of the Stafford Act (e.g., the Transitional Sheltering Assistance (TSA) program, which is intended to provide short-term hotel/motel accommodations).76 Interim housing needs may be met through the Individuals and Households Program (IHP) under Section 408—Federal Assistance to Individuals and Households—of the Stafford Act. IHP assistance may include financial (e.g., assistance to rent alternate housing accommodations) and/or direct assistance (e.g., multifamily lease and repair, Transportable Temporary Housing Units, or direct lease) to eligible individuals and households who, as a result of an emergency or disaster, have uninsured or under-insured necessary expenses and serious needs that cannot be met through other means or forms of assistance.77 IHP assistance is intended to be temporary and is generally limited to a period of 18 months following the date of the declaration, but it may be extended by FEMA.78

Additionally, following a disaster, Congress may appropriate funds through HUD's Community Development Block Grant for disaster recovery (CDBG-DR) to assist communities in long-term rebuilding.

Implementation of Housing-Related Provisions of the Disaster Recovery Reform Act (DRRA)

The Disaster Recovery Reform Act of 2018 (DRRA, Division D of P.L. 115-254), which became law on October 5, 2018, is the most comprehensive reform of FEMA's disaster assistance programs since the passage of the Sandy Recovery Improvement Act of 2013 (SRIA, Division B of P.L. 113-2) and, prior to that, the Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act of 2006 (PKEMRA, P.L. 109-295). The DRRA legislation focuses on improving pre-disaster planning and mitigation, response, and recovery, and increasing FEMA accountability. As such, it amends many sections of the Stafford Act. In addition to those amendments, DRRA includes new standalone authorities and requires reports to Congress,79 rulemaking, and other actions.

The 116th Congress has expressed interest in the oversight of DRRA's implementation, including sections that amend FEMA's temporary housing assistance programs under the Stafford Act. These sections include the following:

- DRRA Section 1211—State Administration of Assistance for Direct Temporary Housing and Permanent Housing Construction—amends Stafford Act Section 408(f)—Federal Assistance to Individuals and Households, State Role—to allow state, territorial, or tribal governments to administer Direct Temporary Housing Assistance and Permanent Housing Construction, in addition to Other Needs Assistance (ONA).80 It also provides a mechanism for state and local units of government to be reimbursed for locally implemented housing solutions.81 This provision may allow states to customize disaster housing solutions and expedite disaster recovery, and FEMA is in the process of developing guidance for state, territorial, or tribal governments seeking to administer these programs.82

- DRRA Section 1212—Assistance to Individuals and Households—amends Stafford Act Section 408(h)—Federal Assistance to Individuals and Households, Maximum Amount of Assistance—to separate the cap on the maximum amount of financial assistance eligible individuals and households may receive for housing assistance and ONA.83 The provision also removes financial assistance to rent alternate housing accommodations from the cap, and creates an exception for accessibility-related costs.84 This may better enable FEMA's disaster assistance programs to meet the recovery-related needs of individuals, including those with disabilities and others with access and functional needs, and households who experience significant damage to their primary residence and personal property as a result of an emergency or major disaster. However, there is also the potential that this change may disincentivize sufficient insurance coverage because of the new ability for eligible individuals and households to receive separate and increased housing and ONA awards that more comprehensively cover disaster-related real and personal property losses.

- DRRA Section 1213—Multifamily Lease and Repair Assistance—amends Stafford Act Section 408(c)(1)(B)—Federal Assistance to Individuals and Households, Direct Assistance—to expand the eligible areas for multifamily lease and repair, and remove the requirement that the value of the improvements or repairs not exceed the value of the lease agreement.85 This may increase housing options for disaster survivors. The Inspector General of the Department of Homeland Security must assess the use of FEMA's direct assistance authority to justify this alternative to other temporary housing options, and submit a report to Congress.86

For more information on DRRA, see CRS Insight IN11055, The Disaster Recovery Reform Act: Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress. Additionally, tables of deadlines associated with the implementation actions and requirements of DRRA are available upon request.

Community Development Block Grants-Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR)

HUD's CDBG-DR program provides grants to states and localities to assist their recovery efforts following a presidentially declared disaster. Generally, grantees must use at least half of these funds for activities that principally benefit low- and moderate-income persons or areas. The program is designed to help communities and neighborhoods that otherwise might not recover due to limited resources.87 CDBG-DR is not available for all major disasters because it is generally subject to Congress passing CDBG supplemental appropriations.

In the 116th Congress, CDBG-DR has been provided $2.4 billion to aid disaster-affected communities with long-term recovery, including the restoration of housing, infrastructure, and economic activity.88 This follows the provision of $37 billion for CDBG-DR in the 115th Congress.89

While CDBG-DR has had a significant role in funding recovery efforts from past disasters, and continues to play a major role in the recovery from the 2017 hurricanes, the program is not formally authorized, meaning the rules that govern the funding use and oversight vary with HUD guidance accompanying each allocation. Some Members of Congress have expressed interest in formally authorizing the CDBG-DR program, in part in response to concerns about HUD's oversight of CDBG-DR funding. In July 2019, the House Financial Services Committee ordered to be reported H.R. 3702, the Reforming Disaster Recovery Act of 2019. The bill would authorize the CDBG-DR program and included a number of provisions to codify financial controls over program funds.

Native American Housing Programs

Native Americans living in tribal areas experience a variety of housing challenges. Housing conditions in tribal areas are generally worse than those for the United States as a whole, and factors such as the legal status of trust lands present additional complications for housing.90 In light of these challenges, and the federal government's long-standing trust relationship with tribes, certain federal housing programs provide funding specifically for housing in tribal areas.

Tribal HUD-VASH

The Tribal HUD-Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (Tribal HUD-VASH) program provides rental assistance and supportive services to Native American veterans who are homeless or at risk of homelessness. Tribal HUD-VASH is modeled on the broader HUD-Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH) program, which provides rental assistance and supportive services for homeless veterans. Tribal HUD-VASH was initially created and funded through the FY2015 HUD appropriations act (P.L. 113-235), and funds to renew rental assistance have been provided in subsequent appropriations acts. However, no separate authorizing legislation for Tribal HUD-VASH currently exists.

In the 116th Congress, a bill to codify the Tribal HUD-VASH program (S. 257) was ordered to be reported favorably by the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs in February 2019. A substantively identical bill passed the Senate during the 115th Congress (S. 1333), but the House ultimately did not consider it.

For more information on HUD-VASH and Tribal HUD-VASH, see CRS Report RL34024, Veterans and Homelessness.

NAHASDA Reauthorization

The main federal program that provides housing assistance to Native American tribes and Alaska Native villages is the Native American Housing Block Grant (NAHBG), which was authorized by the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act of 1996 (NAHASDA, P.L. 104-330). NAHASDA reorganized the federal system of housing assistance for tribes while recognizing the rights of tribal self-governance and self-determination. The NAHBG provides formula funding to tribes that can be used for a range of affordable housing activities that benefit primarily low-income Native Americans or Alaska Natives living in tribal areas. A separate block grant program authorized by NAHASDA, the Native Hawaiian Housing Block Grant (NHHBG), provides funding for affordable housing activities that benefit Native Hawaiians eligible to reside on the Hawaiian Home Lands.91 NAHASDA also authorizes a loan guarantee program, the Title VI Loan Guarantee, for tribes to carry out eligible affordable housing activities.

The most recent authorization for most NAHASDA programs expired at the end of FY2013, although NAHASDA programs have generally continued to be funded in annual appropriations laws. (The NHHBG has not been reauthorized since its original authorization expired in FY2005, though it has continued to receive funding in most years.92) NAHASDA reauthorization legislation has been considered in varying degrees in the 113th, 114th, and 115th Congresses but none was ultimately enacted.93

The 116th Congress may again consider legislation to reauthorize NAHASDA. In general, tribes and Congress have been supportive of NAHASDA, though there has been some disagreement over specific provisions or policy proposals that have been included in reauthorization bills. Some of these disagreements involve debates over specific program changes that have been proposed. Others involve debate over broader issues, such as the appropriateness of providing federal funding for programs specifically for Native Hawaiians and whether such funding could be construed to provide benefits based on race.94

For more information on NAHASDA, see CRS Report R43307, The Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act of 1996 (NAHASDA): Background and Funding.

Department of Veterans Affairs Loan Guaranty and Maximum Loan Amounts

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) insures home loans to veterans as part of the VA Loan Guaranty program. To date, the maximum amount a veteran can borrow has been limited by the Freddie Mac conforming loan limit.95 While veterans can enter into loans that exceed the conforming loan limit, they cannot do so without making a down payment. The fact that VA loans do not ordinarily require a down payment is a popular feature of the program—in FY2018, nearly 80% of loans did not have a down payment.96

Congress removed the conforming loan limit for VA loans entered into on or after January 1, 2020, as part of the Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans Act of 2019 (P.L. 116-23). After the change takes effect, most veterans will be able to enter into loans of any amount, subject to eligibility, without the need for a down payment. An exception exists for veterans who have outstanding VA loans; they will still be subject to Freddie Mac conforming loan limits.

Housing-Related Tax Extenders

In the past, Congress has regularly extended a number of temporary tax provisions that address a variety of policy issues, including certain provisions related to housing. This set of temporary provisions is commonly referred to as "tax extenders." Two housing-related provisions that have been included in tax extenders packages recently are (1) the exclusion for canceled mortgage debt, and (2) the deduction for mortgage insurance premiums, each of which is discussed further below.

The most recently enacted tax extenders legislation was the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123) in the 115th Congress. That law extended the exclusion for canceled mortgage debt and the ability to deduct mortgage insurance premiums through the end of 2017 (each had previously expired at the end of 2016). As of the date of this report, these provisions had not been extended beyond 2017.

In the 116th Congress, S. 617, the Tax Extender and Disaster Relief Act of 2019, would extend each of these provisions through calendar year 2019.

For more information on tax extenders in general, see CRS Report R45347, Tax Provisions That Expired in 2017 ("Tax Extenders").

Exclusion for Canceled Mortgage Debt

Historically, when all or part of a taxpayer's mortgage debt has been forgiven, the forgiven amount has been included in the taxpayer's gross income for tax purposes.97 This income is typically referred to as canceled mortgage debt income.

During the housing market turmoil of the late 2000s, some efforts to help troubled borrowers avoid foreclosure resulted in canceled mortgage debt.98 The Mortgage Forgiveness Debt Relief Act of 2007 (P.L. 110-142), signed into law in December 2007, temporarily excluded qualified canceled mortgage debt income associated with a primary residence from taxation. The provision was originally effective for debt discharged before January 1, 2010, and was subsequently extended several times.

Rationales put forth when the provision was originally enacted included minimizing hardship for distressed households, lessening the risk that nontax homeownership retention efforts would be thwarted by tax policy, and assisting in the recoveries of the housing market and overall economy. Arguments against the exclusion at the time included concerns that it makes debt forgiveness more attractive for homeowners, which could encourage homeowners to be less responsible about fulfilling debt obligations, and concerns about fairness given that the ability to realize the benefits depends on a variety of factors.99 More recently, because the economy, housing market, and foreclosure rates have improved significantly since the height of the housing and mortgage market turmoil, the exclusion may no longer be warranted.

For more information on the exclusion for canceled mortgage debt, see CRS Report RL34212, Analysis of the Tax Exclusion for Canceled Mortgage Debt Income.

Deductibility of Mortgage Insurance Premiums

Traditionally, homeowners have been able to deduct the interest paid on their mortgage, as well as property taxes they pay, as long as they itemize their tax deductions.100 Beginning in 2007, homeowners could also deduct qualifying mortgage insurance premiums as a result of the Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006 (P.L. 109-432).101 Specifically, homeowners could effectively treat qualifying mortgage insurance premiums as mortgage interest, thus making the premiums deductible if homeowners itemized and their adjusted gross incomes were below a specified threshold ($55,000 for single, $110,000 for married filing jointly). Originally, the deduction was to be available only for 2007, but it was subsequently extended several times.

Two possible rationales for allowing the deduction of mortgage insurance premiums are that it assisted in the recovery of the housing market, and that it promotes homeownership. The housing market, however, has largely recovered from the market turmoil of the late 2000s, and it is not clear that the deduction has an effect on the homeownership rate. Furthermore, to the degree that owner-occupied housing is over subsidized, extending the deduction could lead to a greater misallocation of the resources that are directed toward the housing industry.