Introduction

Consumer finance encompasses the financial lives of individuals and households. Americans aspire for economic advancement and wealth building, a central part of the American dream. Safe and affordable financial services are an important tool for most American households to avoid financial hardship, build assets, and achieve financial security over the course of their lives. Households use three types of financial products regularly: credit, insurance, and financial investments. This report will focus on the first category—credit and deposit-taking financial products for personal, family, or household purposes.

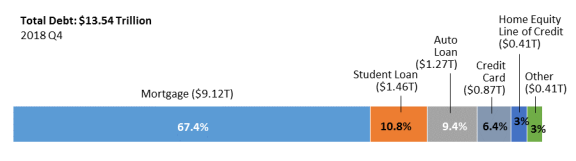

Most households rely on credit to finance some expenses because they do not have enough assets saved to pay for them. Mortgage debt is by far the largest type of household debt. According to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, as shown in Figure 1, mortgages account for approximately 67% of household debt. Student loans are the second-largest type of household debt, followed by auto loans and credit cards.

These and other major consumer finance markets are discussed in more detail in this report under "Overview of Major Consumer Finance Markets," which provides a brief overview of each financial product, recent market developments, and related policy issues. Major consumer finance markets examined in this report include mortgage lending, student loans, automobile loans, credit cards and payments, payday loans and other credit alternative financial products, and checking accounts and substitutes. In general, this report will focus on the consumer and household perspective, and consumer protection policy issues in each market.

|

|

Source: Center for Microeconomic Data, Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2018, https://www.newyorkfed.org/microeconomics/databank.html. |

This report also discusses two important market structures that allow these consumer financial products to be offered: (1) the consumer credit reporting system and (2) the debt collection market. These aspects of the consumer credit system are important because they facilitate the pricing of credit offers and the resolution of delinquent consumer credit products for most consumer credit markets.

The report begins with an overview of U.S. household finances, consumer finance markets, and common policy issues in these markets.

Consumer Finance Policy Issues and Regulation

Consumer finance refers to the saving, borrowing, and investment choices that households make over time. These financial decisions can be complex and can affect households' financial well-being both now and in the future. Understanding why and how consumers make financial decisions is important when considering policy issues in consumer financial markets.

This section provides an introduction to U.S. households' finances, including a breakdown of a household balance sheet and its components. It then provides background on how consumer financial markets operate and general issues in these markets. The section also describes common policy interventions and considerations when using these policy tools. Lastly, this section provides an overview of the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (CFPB)—the main regulator responsible for consumer compliance of financial products and services.

Household Balance Sheet Background

A household's balance sheet1 is similar to a firm's in that it presents a full financial picture, including the following components of a household's financial position:

- Assets—A point-in-time value of what a household owns; can include liquid wealth, such as a savings account or other financial assets from which the household can easily access funds, and illiquid wealth, such as a car or home that the household owns.

- Debts—A point-in-time value of what a household owes; can include a home mortgage, a student loan, or other types of consumer loans.

- Net Worth—Equal to assets minus debts, measures the wealth of a household, including home equity.

- Income—Wages earned from a job or financial investment returns over a period of time (e.g., a year).

- Consumption—Household spending over a period of time, such as rent, food, clothing, and entertainment.

- Savings—The difference between income and consumption over a period of time. When a household's income is greater than its consumption, it can save or invest this unconsumed income, increasing the household's assets or paying off debt owed, reducing the household's total debts.

- Borrowing—New debts taken out over a period of time. When a household's consumption is greater than its income, it can either spend assets it owns or borrow money, increasing the household's debts.

In general, research on household finance suggests that all of the components of a household balance sheet—assets, debts, net worth, income, consumption, savings, and borrowing—are important to understanding a household's financial experience over time. For example, in the event of a financial shock—an unexpected expense such as a car or home repair, a medical expense, or a pay cut—households with a lower income or little liquid savings are much more likely to experience difficulty making ends meet.2 As this example suggests, all of the balance sheet's components need to be accounted for when considering consumer decisionmaking.

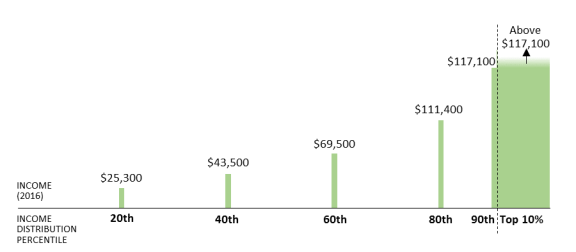

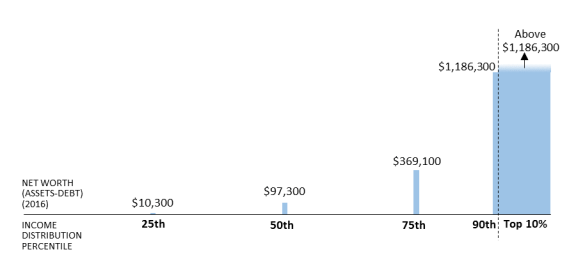

As demonstrated in Figures 2 and 3, household income and net worth in the United States are both distributed unevenly. According to the Federal Reserve Board's (Fed's) Survey of Consumer Finances, the bottom 20% of U.S. households ranked by income have an income below $25,300, whereas the top 10% have an income above $177,100.3 Likewise, the bottom 25% of U.S. households ranked by net worth have a net worth below $10,300, whereas the top 10% have a net worth above $1,186,300. These distributions reflect the variation of household balance sheets within the United States and are due to many factors, such as age, size of household, and household decisions about jobs, homeownership, and other factors.

|

|

Source: Jesse Bricker et al., Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2013 to 2016: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Reserve Bulletin vol. 103, no. 3, September 2017, p. 37, https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/scf17.pdf. Notes: This report uses the income classifier from the Survey of Consumer Finances respondent-reported measure of usual income, which captures household income with transitory fluctuations smoothed away to approximate the economic concept of permanent income. |

|

|

Source: Jesse Bricker et al., Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2013 to 2016: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Reserve Bulletin, vol. 103, no. 3, September 2017, p. 37, https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/scf17.pdf. |

Consumer Finance Markets and Policy Considerations

This report examines household borrowing, with a particular focus on consumer financial products, such as mortgages, credit cards, and auto loans, which allow a household to borrow and make payments. As described in the previous section, consumer behavior in these markets may be driven by other parts of the balance sheet, such as the need to build assets or withstand a financial shock. Three common reasons households use credit are as follows:

- Asset Building—Using credit to make investments can allow a household to build wealth over time. For example, a household can use a mortgage to pay for an asset, such as a house, that may appreciate over time. A household also can use student loans to fund education expenses to make a higher income in the future. In both cases, households are using credit to fund household investments that may lead to greater wealth in the future.

- Consumption Smoothing—Using credit to move income across time periods allows a household to consume future income now. For example, recent college graduates might use credit cards to pay for expenses before their new jobs begin. This money is more valuable to graduates now, before they have wages, than in the future, when they have enough income to meet living expenses.

- Financial Shocks or Emergencies—Using credit to pay for unexpected expenses allows a household to compensate for an emergency, such as a car or home repair, a medical expense, or a pay cut. For example, a consumer might take out a payday loan to repair a car and continue to go to work. This money is more valuable to the consumer during the financial emergency than in the future.

Each consumer financial market is unique and governed by various distinct laws and regulations. However, consumer financial markets generally share similar market dynamics. In all of these markets, consumers often act in similar ways when making financial decisions, and firms tend to act in comparable ways across markets to attract consumers and make profits.4 Therefore, the government tends to consider similar policy interventions and factors when regulating these markets.

Mainstream economic theory asserts that competitive free markets generally lead to efficient distributions of goods and services to maximize value for society.5 Under this theory, each market moves toward an efficient price, at which the supply of goods produced by firms and the amount of goods demanded by consumers equal one another. If consumers demand credit products, then banks or other lenders should want to provide these products to consumers if they can make a profit. Without major barriers for new lenders to enter the market, more lenders should start providing credit to consumers, until the price is no longer excessively profitable to lenders. At this point, the market is at equilibrium, its efficient outcome for society. If these conditions hold, policy interventions cannot improve on the financial decisions that consumers make based on their unique situations and preferences. For this reason, some policymakers are hesitant to disrupt free markets, on the theory that prices determined by market forces lead to efficient outcomes without intervention.

The life-cycle model is a prevalent economic hypothesis that assumes households usually want to keep consumption levels and their lifestyles stable over time.6 For example, severely reducing a household's consumption one month may be more painful for a household than the pleasure of a much higher household consumption level in another month. Therefore, households save and invest during their careers in order to afford a stable income across their lives, including retirement. This model suggests that wealth increases as households age, which generally fits household data in the United States.7 However, income and wealth inequality continues to exist after controlling for household age, suggesting that age is not the only important factor.8

There are also circumstances where the life-cycle model fails to correspond to household behavior in the United States. A recent National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) working paper on behavioral household finance identifies three facts about U.S. household balance sheets.9 First, income and consumption move together very closely, unlike the stable consumption that the life-cycle model would predict. Second, U.S. households on average tend to have low levels of liquid wealth, such as money in a savings account, and a high incidence of credit card borrowing. Third, most U.S. households have much of their wealth in illiquid assets, such as home equity. These patterns might fit the life-cycle model if borrowing money is inexpensive and illiquid assets have higher returns than liquid assets. However, these assumptions might not apply to all households and other explanations might fit these patterns better.10 Generally, these three facts are important background to better understand consumer behavior in financial markets. These facts suggest why many U.S. households depend on access to affordable credit and robust consumer financial markets, both for short-term needs and for building wealth over time.

In these theoretical frameworks, market failures occur when a free market is inefficient due to departures from the standard economic framework, which includes assumptions about perfect information and perfect competition. Market failures can reduce economic efficiency and consumer welfare. In these cases, government policy can potentially correct market failures to bring the market to a more efficient outcome, maximizing social welfare. Yet, policymakers often find it challenging to determine whether a policy intervention will help or harm a particular market's efficiency.

The following sections discuss two specific departures from the conditions associated with economic efficiency—imperfect information and behavioral biases. These market failures are important to understanding consumer credit markets.

Imperfect Information

Imperfect information, or information asymmetry, is when one party in a transaction (e.g., a firm) has more accurate or more detailed information than the other party (e.g., a consumer). This imbalance can result in inefficient outcomes.11 For example, ideally consumers in a mortgage market will shop around among lenders for the best interest rate, fees, and other terms for their own personal situations. Yet, acquiring information (e.g., contacting a variety of different lenders to compare loan terms) can be time consuming. Consumers might also be willing to spend more to save time or to have a better experience closing their mortgage. However, if information asymmetry exists—for example, if interest and fee costs are hidden, confusing, or difficult to obtain—some consumers might choose a mortgage loan that is not optimal based on the criteria they deem to be important. In this case, the mortgage market will not lead to efficient societal outcomes, possibly costing some consumers more for a loan than is necessary and dissuading some consumers who otherwise would from entering the market. Information asymmetries occur in the opposite way as well. Often, lenders might not have accurate or detailed information about a consumer, making it hard for them to estimate a consumer's likelihood of default on a loan. The credit reporting industry developed to give lenders more information about a consumer and make the markets for consumer credit more efficient. For more information on the credit reporting industry, see the section of this report titled "Credit Reporting, Credit Bureaus, and Credit Scoring."

Behavioral Biases in Consumer Decisionmaking

Behavioral research suggests that humans tend to have biases in rather predictable patterns.12 This research suggests that the human brain has evolved to quickly make judgments in bounded, rational ways, using heuristics—or mental shortcuts—to make decisions. These heuristics generally help people make appropriate decisions quickly and easily, but sometimes, they can result in choices that make the decisionmaker worse off financially. Within consumer finance markets, a few of these biases tend to be particularly important:

- Choice Architecture—Research suggests that how financial decisions are framed can affect consumer decisionmaking in many ways. For example, people can be anchored by an initial number, even if it is different from their next choice.13 In one illustration of this concept, researchers had subjects spin a wheel of fortune with numbers between zero and 100, then asked them the percentage of African countries in the United Nations. The random number generated in the first stage subconsciously affected subjects' guesses in the second stage, even though they were not related. Another example of a decisionmaking bias is defaults.14 For example, employees are more likely to be enrolled in a 401(K) plan by employer defaults than if they actively need to make a choice.15 A third example of a framing bias is loss aversion, the idea that people tend to respond more strongly to potential losses than gains.16 Therefore, when choices are framed as a potential loss, such as "an opportunity you don't want to miss," consumers respond more strongly than they do to potential benefits.

- Present Bias and Scarcity—When people tend to put more value on having something now, rather than in the future, even when there is a large benefit for waiting, this behavior is called present bias.17 In addition, even when people decide they should do something difficult, such as saving for the future or choosing a retirement plan, self-control and procrastination may prevent them from following through on their intentions.18 These human biases might lead consumers to make financial decisions that are not optimal.19 Furthermore, a scarcity mindset can make optimal decisionmaking more difficult.20 Difficult decisions, such as managing finances, require cognitive bandwidth. When under extreme stress, such as living in poverty, people may tunnel their vision, focusing on immediate needs (e.g., paying current bills), rather than prioritizing based on the big picture (e.g., increasing future income). Self-control might also be a limited resource for humans, where the more self-control a person needs to exert over a day, the harder it is to maintain.21 These limitations to human cognitive functioning can sometimes lead consumers to make flawed financial decisions.

- Budgeting Biases (Mental accounting)—Often, households use mental accounts, amounts of money mentally allocated in advance for different purposes, to make consumption decisions.22 For example, a household may have a monthly budget for food, clothing, and entertainment. Even though money is fungible, many households act as if spending in one category does not affect spending in another category.23 This categorization is an intuitive and simple way of thinking about a budget. Although this thinking reduces cognitive effort, it can also lead to predictable biases. For example, research suggests that people have trouble forecasting unusual or infrequent expenses.24 For this reason, these expenses are generally not fully accounted for in the mental budget, leading to overspending.

Although consumers might not be aware of these biases when making financial decisions, they are important because firms can take advantage of them to attract consumers. For example, choice architecture biases might influence how marketing materials are developed, emphasizing certain terms to make a financial product seem more desirable to consumers. In addition, product features may be developed to take advantage of people's present bias, scarcity mindset, or mental accounting mistakes.

Common Policy Interventions and Considerations

In response to market failures, such as information asymmetry and behavioral biases, the government uses policy interventions intended to bring consumer markets to a more efficient market outcome. Three types of policy interventions are common in consumer finance:

- Standardized Consumer Disclosures—Financial products can be complex and difficult for consumers to fully understand. Mandated consumer disclosures are a common policy intervention in consumer financial markets, generally intended to give consumers more information about the costs and terms before they take out a new financial product, thus reducing asymmetric information market failures. Standardized disclosures can also help consumers shop for the best terms, because all financial product terms are required to be disclosed in the same way. Furthermore, because disclosure structure and formatting are often standardized, mandated consumer disclosures can also account for choice architecture biases. Laws that mandate consumer disclosures in financial markets include the Truth in Lending Act (TILA),25 which requires standardized disclosures for certain consumer credit products, and the Truth in Savings Act,26 which requires standardized disclosures for certain bank accounts.

- Unfair, Deceptive, or Abusive Practices or Acts—Consumers seeking loans or financial services could be vulnerable because some consumers may lack financial knowledge or be susceptible to biases described in the above section. For this reason, certain consumer protection laws prohibit unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts or practices in consumer financial markets.27 These acts and practices can include both individual firm conduct and product features.28

- Fair Lending—Fair lending laws prohibit discrimination in credit transactions based upon certain borrower characteristics, such as sex, race, religion, and age. These laws historically have been interpreted to prohibit both intentional discrimination and disparate impact discrimination, in which a facially neutral business decision has a discriminatory effect on a protected class.29 Federal fair lending laws in consumer financial markets include the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA),30 the Fair Housing Act (FHA),31 and the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA).32

Policy Considerations

The market effects of new laws or regulations are important considerations. Does the policy on average lead the market closer to or farther from its efficient outcome? In consumer financial markets, both households and firms may react to new policy. If all of a policy's potential impacts are not considered, it can have unintended effects and perhaps fail to reach policymakers' objectives.

From a consumer perspective, new policy formulations should consider the policy's effect on consumer decisionmaking, the impact on household well-being over time, and whether these effects might vary across the population. For example, a new disclosure policy might improve consumer comprehension, but not consumer decisionmaking, thus failing to affect the market as intended. In other cases, a subset of consumers may be susceptible to a deceptive practice. If a new policy eliminates that deceptive practice in the market, the policy may only affect that subset of consumers who were susceptible, rather than the whole consumer population.

From a firm's perspective, new policy formulation should consider both the cost for firms to implement the policy as well as its impact on the market's competitiveness, both within and outside of the regulated market. Another important consideration is the policy's impact on consumer prices and financial product availability. For example, complying with a new regulation might require a firm to bear costs. This might force lenders to raise prices, or lenders who cannot bear the additional costs may leave the market. Higher prices and less choice may result in consumers seeking other credit products outside of the market, or reduce consumers' ability to access credit.

Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

Most experts agree that an important factor in the 2008 financial crisis was a housing bubble that led lenders to relax their underwriting standards (or the process by which a lender determines whether a borrower is creditworthy), which in some cases led to consumer protection abuses.33 In response, the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) established the CFPB to implement and enforce federal consumer financial law while ensuring consumers can access financial products and services.34 The CFPB's statutory purpose is to enable markets for consumer financial services and products to be fair, transparent, and competitive.35 Dodd-Frank consolidated certain consumer finance-related responsibilities previously held by other regulators in the CFPB and created new authorities unique to the CFPB.36 The act also directed the CFPB to develop and implement financial education initiatives, collect consumer complaints, and conduct consumer finance research.

The CFPB generally has regulatory authority over providers of an array of consumer financial products and services, including deposit taking, mortgages, credit cards and other extensions of credit, loan servicing, consumer reporting data collection, and debt collection associated with consumer financial products. The CFPB's authorities and the breadth of products, services, and entities that fall within its jurisdiction are considerable, but Dodd-Frank imposes some important exceptions to and limitations on those powers.37 The CFPB's authorities fall into three broad categories: rulemaking, writing regulations to implement laws under its jurisdiction; supervision, the power to examine and impose reporting requirements on financial institutions; and enforcement of various consumer protection laws and regulations.

The CFPB is authorized to prescribe regulations to implement 19 federal consumer protection laws that largely predated Dodd-Frank.38 These enumerated consumer laws govern a broad and diverse set of consumer financial services and generally apply to any entity offering those services. Dodd-Frank also provided CFPB new power to issue rules declaring certain acts or practices associated with consumer financial products and services to be unlawful because they are unfair, deceptive, or abusive. Other aspects of the CFPB's regulatory power—particularly the scope of its supervisory and enforcement authority—vary depending on a number of factors, including an institution's size and whether it holds a bank charter.

The CFPB is headed by a director appointed by the President with the consent of the Senate for a five-year term. It is located within the Federal Reserve System (Fed), although the Fed does not influence the CFPB's budget or personnel decisions. The Fed also cannot veto a rule issued by the CFPB, but the Financial Stability Oversight Council can overturn a CFPB rule with the vote of two-thirds of its members.39 The CFPB is funded through the Fed's earnings, rather than through the typical appropriations process. The CFPB requests monetary transfers from the Fed, with a cap on the amount of these transfers based on a formula set in statute. For FY2018, the CFPB's funding cap was $663 million, and the agency's net operating costs were $553 million.40

Overview of Major Consumer Finance Markets

The following sections examine specific issues within major consumer debt markets: mortgage lending, student loans, automobile loans, credit cards and payments, payday loans and other credit alternative financial products, and checking accounts and substitutes. The markets discussed are under the CFPB's jurisdiction, and sometimes that of other regulators as well. Each section briefly describes the financial product, recent market developments, and selected policy issues that may lead each market away from its efficient price or outcomes. These sections focus on the consumer and household perspective as well as consumer protection policy issues in each market.

Mortgage Lending Market

A mortgage loan is a loan collateralized by a house and its land.41 Generally, consumers use these loans to purchase a new home or refinance an existing one. These types of mortgages are often called first liens, because if a consumer defaults on the loan, the lender is typically the first in line to be compensated through the proceeds of a home foreclosure. First-lien mortgage loans are usually installment loans, in which the consumer pays off the loan in monthly installments over 15 years or 30 years. Most mortgage loans in the United States have a fixed interest rate and fixed installment amount over the course of the loan, affected by the consumer's credit score and market conditions.42

Households buying a new home and taking out a mortgage loan to purchase it generally cannot borrow for the house's full value. To limit the risk to the lender, borrowers are typically required to make a down payment, the difference between the house's value and the mortgage loan. If the down payment is less than 20% of the home's value, the borrower is often required to pay for additional insurance.

In addition to first-lien purchase mortgages, a consumer may choose to take out a home equity line of credit (often referred to as HELOC) or a smaller installment mortgage loan, which often is a second lien. A second lien means that the lender is second in line, after the first lien holder, to be compensated if the consumer defaults and the home is foreclosed upon. These loans are underwritten using the home's value, but can be used for a variety of different purposes either related to the home or not. For example, second mortgages can be used to renovate the home, pay for college, or consolidate credit card debts.

Mortgage loans are by far the largest consumer credit market in the United States, and homes are a large part of most households' wealth. According to the Fed, more than $9 trillion of mortgage debt is currently outstanding,43 and more than $15.5 trillion in real estate equity is owned by households.44 As of the first quarter of 2019, 64.2% of U.S. households owned their home.45 Many people view homeownership as an important way to build wealth over time, through both price appreciation and home equity gained by paying down their mortgages. Nevertheless, because home prices can fluctuate over time, this investment can be risky, especially if the homeowner only stays in the home for a short time. Although homeownership has certain benefits, such as tax benefits like the mortgage interest tax deduction,46 it also imposes costs on the household, such as mortgage loan closing costs and home maintenance.

As noted above, most experts believe that a housing price bubble was a central cause of the 2008 financial crisis. In response, Dodd-Frank reformed the mortgage market by attempting to strengthen mortgage underwriting standards, to reduce the risk that consumers default on their mortgages even if house prices fluctuate in the future. Dodd-Frank also directed the CFPB to update federal mortgage disclosure forms (called the combined TILA/RESPA form)47 and improve standards for mortgage servicing (a company who manages mortgage loans after the loan is originated).48

During and after the financial crisis, mortgage lenders tightened underwriting standards, making it harder for consumers to qualify for a loan. Although most borrowers with good credit scores continued to qualify for mortgage credit, other borrowers in weaker financial positions found it more difficult to obtain a mortgage.49 As the economy has recovered, concerns exist about whether new consumer compliance regulation in the mortgage market has struck the right balance between prudent mortgage underwriting and access to credit for potential borrowers to build wealth. Certain features of mortgages during the mortgage boom that were considered to be particularly risky, such as teaser interest rates and loans with little or no income verification, are now uncommon in the mortgage market.50 However, research suggests that regulating underwriting standards may have caused lenders to prefer certain borrowers, such as those with lower debt-to-income ratios.51

Mortgage shopping is another policy issue in this market. Consumers do not tend to shop among lenders for more advantageous mortgage interest rates, even though large price differences exist in the market. According to the CFPB, nearly half of all borrowers only seriously consider one lender or broker before taking out a mortgage.52 Given the range of interest rates available to a consumer at any given time, the CFPB estimates that a consumer could save thousands of dollars on a mortgage by shopping for the best interest rates.53

House price affordability has been another policy issue in recent years.54 In high-cost, large metropolitan areas, house prices rose quickly in the past decade, making it harder for consumers to buy a home in these cities.55 Likewise, the national homeownership rate has declined by almost 5 percentage points since 2005, from 69.1% to 64.2%.56 Given that homeownership can help a family build wealth over time, this trend concerns some policymakers.

Student Loans

Student loans allow students and their families to pay for postsecondary education expenses while they are enrolled in school.57 Education is an investment intended to allow students to earn higher incomes after they complete school and throughout the rest of their careers. In general, student loans are paid back in installments—for example, a fixed payment every month for 10 years. Student loan debt has more than doubled in the past decade.58 Since 2010, student loan debt has been the second-largest category of consumer debt, after mortgage debt.59 In academic year 2016-2017, the average amount of student loan debt for a bachelor's degree recipient who borrowed funds to complete the degree was $28,500.60

Unlike other consumer financial markets, most student loans are originated and owned by the federal government.61 In general, these federal loans are accessible to large portions of the postsecondary student population and their families with limited underwriting of their creditworthiness, estimated future income, or other estimates of their ability to repay the loan. The Department of Education (ED) manages most of the federal student loan programs.62 Congress sets interest rates and other loan terms and conditions in statute each year. ED contracts out student loan servicing, sets servicing standards in these contracts, and enforces these servicing standards. The CFPB is the primary regulator for private student loan lending and servicing and has also asserted a role in ensuring compliance with consumer protection laws related to federal student loan servicing.63

From a regulatory perspective, policymakers continue to debate what role the CFPB should play in the federal student loan industry. Consumer groups advocate for more active CFPB enforcement of consumer protection standards in federal student loan servicing. However, because ED already assumes a significant role in how its contractors service federal student loans—and taxpayers are responsible for additional servicing costs and default risk for nonpayment—some have questioned the need for the CFPB to regulate in the same space.

A major concern in the student loan market is whether students are able to manage their debt after graduation. Moreover, unlike other consumer debts, student loans are generally not dischargeable during a bankruptcy proceeding except in limited circumstances.64 These concerns have led to efforts to make loan repayment terms more flexible. For example, some federal student loan borrowers now have the option to choose income-driven repayment plans, under which a borrower's monthly loan payments are based on a percentage of the borrower's discretionary income. Loan forgiveness programs have also been developed and expanded in recent years, especially for borrowers in public service occupations. ED manages several of the student loan forgiveness and repayment loan programs.65 Reports from the CFPB student loan ombudsman have uncovered issues in these programs' implementation—such as with payment processing, billing, customer service, and borrower communication—that make it difficult for borrowers to know their options, understand the process, and qualify for forgiveness or repayment loan programs.66

Questions have also arisen regarding student loan availability and whether loans should be limited to certain types of educational programs that enable their students to gain quality employment and successfully pay back their loans.67 Many students make school choice and curriculum decisions at a young age, when they might not have much experience making financial decisions.68 In addition, information on program quality and student employment outcomes after graduation is limited. These information asymmetry problems can make it difficult for students to make good financial decisions for their future careers.69 Questions also exist about the extent to which student loan access causes tuition prices to rise.70 For example, if access to student loans makes it easier for schools to raise tuition, then it might lead to some students being worse off.71 Some question whether the availability of student loans might harm the larger economy. For example, researchers debate student loan debt's effects on future macroeconomic performance, including effects on career choice, family formation, home ownership, and retirement savings.72

Automobile Loans

An automobile (auto) loan allows a consumer to finance the cost of a new or used car.73 Auto loans are usually structured as installment loans, in which a consumer pays a fixed amount of money each month for a predetermined time period, frequently three to seven years. Lenders often require consumers to make a down payment to obtain the loan. Auto loans are secured by the automobile, so if a consumer cannot pay the loan, the lender can repossess the car to recoup the loan's cost.

Auto loans are the third-largest consumer credit market. At the end of 2018, 113 million consumers—roughly 45% American adults—had an auto loan, and auto loan debt outstanding totaled almost $1.3 trillion.74 According to the CFPB, auto loan terms have increased recently. In 2009, 26% of auto loans originated were for six or more years, whereas in 2017, these loans constituted 42% of originations.75 This trend may be due in part to rising vehicle costs76 and consumers keeping their cars longer.77

Reportedly, most auto loans are arranged at the auto dealership where the car is purchased, referred to as the indirect auto financing market.78 Indirect auto financing involves the auto dealer forwarding information about the prospective borrower to one or more lenders to solicit potential financing offers.79 The dealer is often compensated for originating the loan through a discretionary markup, which is the difference between the lender's interest rate and the rate a consumer is charged. The lender may cap the possible size of the dealer markup (e.g., 2.5%) to limit the loan from becoming too susceptible to default. Auto dealers and consumers can negotiate the loan's interest rate within this range, and therefore indirectly determine how much to compensate the auto dealer for the convenience of arranging the loan.80

Alternatively, consumers can go directly to a bank, credit union, or other lender for an auto loan before making their purchases, avoiding the dealer markup cost.81 Consumers may prefer arranging auto financing through an auto dealer or directly through a lender, depending on their preferences regarding convenience, cost, and other factors. In either case, the lender usually owns the loan and can service it itself or through a third-party company.82

In the indirect auto financing market, the dealer markup arrangement can incentivize the auto dealer to negotiate—and profit from—a higher interest rate with the consumer. The auto dealer may also choose the lender who compensates it the most—for example, the lender that allows the largest markup, rather than the lender offering the best terms for the consumer. Although other consumer credit markets include markups, it is less common for bank or credit union lenders to allow an outside broker in the transaction discretion as to the amount of the markup. For example, although the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act83 restricts such practices in the mortgage market, after reports of mortgage brokers steering customers to more expensive loans due to "kickbacks"—unearned fees for a referral—in the lead-up to the financial crisis, Congress in 2010 took actions to further restrict these practices.84

The information asymmetry in the indirect auto finance market sometimes can lead to higher prices for consumers. Consumers are not always aware that they can negotiate on loan terms when obtaining dealer-arranged financing.85 For this reason, many consumers do not shop for auto loans.86 Consumers' lack of awareness—combined with auto dealers' discretion on markups—may leave them vulnerable to bad actors, making the auto loan market uncompetitive.

The CFPB oversees consumer protection compliance for auto lenders, but not for auto dealers' typical activities. Dodd-Frank states that "the Bureau may not exercise any [authority] over a motor vehicle dealer that is predominantly engaged in the sale and servicing of motor vehicles, the leasing and servicing of motor vehicles, or both."87 The scope of this exclusion continues to be debated, given the key role auto dealers play in the auto lending market.

In 2013, the CFPB issued a controversial bulletin providing guidance to indirect auto lenders on how to comply with the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA).88 This guidance generally stated that indirect auto lenders should impose controls on or revise and monitor dealer markups to ensure they do not result in disparate impact based on race or other protected classes. From 2013 to 2016, the CFPB, in coordination with the Department of Justice, issued consent orders to settle enforcement actions against American Honda Finance Corporation, Toyota Motor Credit Corporation, Fifth Third Bank, and Ally Financial & Ally Bank for ECOA violations in indirect auto lending markets.89 The CFPB generally alleged that these institutions violated ECOA by permitting their dealers to charge markups that resulted in disparate impacts on the basis of race and ethnicity. Auto lenders generally do not collect information on the race or ethnicity of borrowers. In the absence of direct evidence, the CFPB used a new proxy methodology, a statistical method developed for estimating race and ethnicity using geography and surname-based information.90 Although this method may not be able to flawlessly identify race or ethnicity for an individual, aggregate, company-wide estimates of disparate impacts are much more precise. In general, these institutions did not admit or deny the allegations as part of the consent orders but, among other things, paid monetary penalties and agreed to limit their markups to reduce these alleged disparities.

The CFPB's indirect auto lender guidance and the resulting enforcement actions were the subject of significant attention and debate. For example, some expressed the view that the guidance went beyond what ECOA and the Dodd-Frank Act require of auto lenders, while others considered it an important step toward addressing discrimination.91 In 2018, Congress rescinded the guidance pursuant to the Congressional Review Act.92 Nevertheless, some observers argue that discrimination in auto lending markups continues to be an area of concern.93

Credit Cards and Payments

Retail payment services allow consumers to pay merchants for goods and services without cash, sometimes called a payment transaction.94 Consumers can use these services to pay bills, make person-to-person payments, or withdraw cash. These services can be found in many consumer financial products, including credit, debit, and prepaid cards and checking accounts. Given the rise of internet shopping, retail payment services have become especially critical for consumers to be able to make daily purchases. The most common methods of payment are debit cards, cash, and credit cards, respectively.95 Debit and prepaid cards generally are associated with a funded account from which the consumer draws money to pay for transactions. In contrast, credit cards allow a consumer to pay for transactions using credit.

According to the CFPB, in 2017, just under 170 million consumers, roughly 70% of the U.S. adult population, had a credit card.96 Credit cards provide consumers with unsecured revolving credit, meaning the loan is not secured with any collateral if the consumer defaults (and thus, the lender has no recourse to seize any property connected to the loan in case of consumer default). In some cases, credit cards are used for payment transaction convenience and paid in full each month without incurring interest. These types of users are sometimes called transactors. In other cases, credit card users borrow money up to a credit limit and make only a minimum payment (generally a small portion of the outstanding balance) on the debt each month, incurring interest on the unpaid balance. These types of credit card users are called revolvers. In 2016, average interest rates for general purpose credit cards were just over 17%.97 Although a consumer can move between transacting and revolving, consumers tend to show persistent payment behavior.98 According to a Fed survey, roughly half of consumers transact and half revolve.99

Credit cards are valuable to consumers in part because they are flexible—both the amount borrowed and the amount paid can vary each month according to the consumer's needs. For example, if a household experiences a financial shock, such as unemployment or a car or house repair, the household can use credit cards to borrow money quickly and easily, which the household can then pay back when it is able. Credit cards can also be used to smooth consumption over time, which may be particularly valuable to households with tight budgets.100

However, credit cards also are structured in a way that can take advantage of many consumer decisionmaking biases, which can result in households incurring debt. For example, mental accounting biases can lead to overspending, and credit cards allow households to overspend easily, perhaps without even realizing it until their monthly bill is due. Research suggests that the half of credit card holders who are persistently in credit card debt are likely to be present biased and have little liquid savings.101

The type of information disclosed in a typical credit card statement may play an important role in how revolving consumers repay credit card debt. Research suggests that many people are anchored by the minimum payment amounts included in each statement, which bias their decisions about how much to pay each month.102 Specifically, the research suggests these consumers are either paying the minimum payment or employing heuristics to pay near the minimum (e.g., twice the minimum or $20 above the minimum).103 This cue may unconsciously influence consumers to make a lower payment than they otherwise would.

For these reasons, the Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure Act of 2009 (CARD Act) established new disclosure requirements for credit cards.104 The CARD Act changed the periodic disclosure credit card companies are required to make to consumers to include information on how long it will take to pay off a consumer's debt if the consumer makes only the minimum payment. The disclosure also now includes the amount a consumer would have to pay to repay the debt in three years and how much interest the consumer would save by paying the debt off in three years compared with the minimum payment. These changes in the disclosure requirements were intended to nudge consumers to pay more on their credit cards each month, but research suggests that they did not have as big of an effect on consumer payment behavior as intended, in part because online portals—which have become a popular method of credit card payment—are not required to contain these disclosures.105

Payday and Other Credit Alternative Financial Products106

When consumers face financial shocks, such as unemployment or a car repair, sometimes they need credit to manage the unforeseen event. One option a consumer may access is a short-term, small-dollar loan, which tends to be outstanding for a short period of time and for a small amount of money, generally less than $1,000. Banks and credit unions sometimes provide these types of loans through cash advances or checking account overdraft programs. Many consumers, often those with a low credit score or no credit history, also turn to alternative financial products from a nonbank institution to provide credit when needed. Alternative financial products include payday loans, pawn shop loans, auto title loans, and other types of products from nonbank providers. According to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), in 2017, 19.7% of American households did not have access to mainstream credit107 and 6.9% used a credit alternative financial service.108 Households that rely on credit alternative financial services are more likely to be lower-income, younger, and a racial or ethnic minority compared to the general U.S. population.109

Perhaps the best known of these products are payday loans, which have been the subject of significant regulatory, congressional, and media attention. Payday loans are structured as short-term advances that allow consumers to access cash before they receive a paycheck. These loans are designed to be paid back on a consumer's next payday. Payday loans are offered through storefront locations or online for a set fee. The underwriting of these loans is minimal, with consumers required to provide little more than a paystub and checking account information to take out a loan. Rather than paying off the loan entirely when it is due, many consumers roll over or renew these loans.110 Sequences of continuous rollovers may result in consumers being in debt for an extended period. Because consumers generally pay a fee for each new loan, payday loans can become expensive.

In 2010, the Dodd-Frank Act authorized the CFPB to oversee payday lenders for the first time at the federal level,111 but prohibited the CFPB from imposing an interest rate limit on any type of credit, including payday loans.112 As of February 2019, 17 states and the District of Columbia either ban or limit the interest rates on these loans.113

In the payday market, policy disagreements tend to center on balancing access to credit with consumer protection. The academic research is mixed in terms of payday loans' effect on consumer well-being.114 When consumers have emergencies, short-term, small-dollar credit can help them make ends meet. Payday loans' product features, such as the option to roll over, can allow consumers to pay back their loan flexibly, but also can play into cognitive biases, including present biases and scarcity tunnel vision. Some consumers pay off payday loans quickly, but a sizable minority are in debt for a long period of time—a CFPB study found 36% of new payday loan sequences were repaid fully without rollovers, while 15% of sequences extended for 10 or more loans.115

In October 2017, during the leadership of then-Director Richard Cordray,116 the CFPB finalized a rule covering payday and other small-dollar, short-term loans that has not yet gone into effect.117 The 2017 rule asserts that it is "an unfair and abusive practice" for a lender to make certain types of short-term, small-dollar loans "without reasonably determining that consumers have the ability to repay the loans." The rule would mandate underwriting provisions for short-term, small-dollar loans unless made with certain features. In February 2019, the CFPB under Trump-appointed Director Kathy Kraninger issued a proposed rule that would rescind the mandatory underwriting provisions before the 2017 final rule goes into effect.118 The 2019 proposed rule would leave unchanged other parts of the 2017 rule, such as other payment provisions relating to protections for consumers paying back these loans.

Given the concerns about consumer harm from payday and other small-dollar, short-term loans, some financial institutions are interested in exploring other loan models that try to give consumers access to credit for short-term needs at a lower cost and with an easier repayment process. For this reason, prudential regulators, such as the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and the FDIC, are exploring ways to encourage banks to offer small-dollar credit products to consumers.119 However, it is unclear whether these different types of products can improve outcomes for consumers compared to payday loans, given that the population of consumers these products would target and those consumers' biases concerning money management are likely similar.120

Checking Accounts and Substitutes

Checking accounts allow consumers to deposit money and make payments, for example, using bill pay and paper checks. Frequently, a checking account includes access to a debit card, to increase a consumer's ability to make payment transactions through the account. Checking accounts are generally provided by a bank or credit union, and consumers' deposits are government insured (up to a certain amount) against the institution's failure.121

In recent years, the availability of free or low-cost checking accounts has reportedly diminished, and fees associated with checking accounts have grown.122 The most common fees that checking account consumers incur are overdraft and nonsufficient fund fees.123 Consumers can incur an overdraft when they transact below their account balance, and the bank or credit union covers the negative balance for the consumer for a fee. In general, negative balance episodes are short in duration. According to the CFPB, half of all episodes last three or fewer days, and more than three-quarters last a week or less.124

Overdraft services can help consumers pay bills on time. However, overdraft fees can be costly, particularly for consumers who are inattentive or tend to overspend due to tight budgets and mental accounting biases. CFPB research suggests that a small number of checking account holders incur most overdraft fees, with 8.3% of consumers overdrafting more than 10 times per year and accounting for 73.7% of overdraft fees.125 According to the CFPB, these frequent overdrafters tend to be more credit constrained, have lower credit scores, and are less likely to have a general-purpose credit card than the general U.S. population.126

In 2009, a provision of the CARD Act required consumers to affirmatively opt in for overdraft coverage of ATM withdrawals and nonrecurring debit card transactions.127 Since this requirement was implemented, opt-in rates have tended to vary by bank, from single-digit percentages to more than 40% within particular institutions.128 Frequent overdrafters who opt in to overdraft services seem to have similar characteristics to those who do not opt in, but tend to pay more in fees.129 Given this research, consumer advocates have raised concerns about whether overdraft programs are sufficiently transparent and whether consumers receive sufficient disclosures regarding these programs. Advocates have also questioned how financial institution practices influence the opt-in decision.130

Overdrafts may be caused by the lapse of time between payment authorization, account settlement, and when funds are available to the consumer.131 Because of these time lapses in the payments system, some consumers may not realize no funds are available when they overdraft their account.132 For this reason, some argue that a faster payment system or other financial planning products may help consumers keep better track of their balances, preventing overdrafts.133

Overdraft fees may lead to involuntary checking account closures, leaving some households without access to a bank account. According to the FDIC, in 2017, 6.5% of households were unbanked, meaning that no one in the household had a checking or savings account from an insured institution.134 Unbanked households tend to be younger and are more likely to be racial or ethnic minorities than the general U.S. population.135 The main reasons households cite for not having a bank account include insufficient account funds, not trusting banks, and high account fees.136 Moreover, in 2017, an additional 18.7% of households were underbanked, meaning that the household obtained financial products or services outside of the banking system, products sometimes called alternative financial services.137 Certain observers contend that financial outcomes for the unbanked and underbanked would be improved if banks—which may be a more stable source of relatively inexpensive financial services relative to certain alternatives—were more active in serving these customers. For this reason, policymakers and observers will likely continue to explore ways to make banking more accessible to a greater portion of the population.138 However, it may be expensive for banks to serve these customers—for example, they might have low-balance accounts. At least some of these consumers may be served better by alternative financial providers if their products are less expensive or if they provide more customer service than banks.

General-purpose prepaid cards may be considered an alternative to a traditional checking account, and they can be obtained through a bank, at retail stores, or online. These cards can be used in payment networks, such as Visa or MasterCard. It is also possible to direct deposit payroll checks onto these cards. But unlike checking accounts, funds on prepaid cards are not always federally insured against an institution's failure.139 According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, almost half of all unbanked households use a general-purpose prepaid card.140

Overview of Consumer Finance Market Support Systems

Although each consumer credit market is unique, certain common aspects of the consumer credit system facilitate the pricing of credit offers and the resolution of delinquencies and defaults for most consumer credit markets. This section discusses two of what this report will refer to as market support systems: the consumer credit reporting system (which helps lenders price consumer loans) and the debt collection market (which helps lenders to collect upon consumer default). Notably, in both these market support systems, consumers do not have the ability to choose the financial institution or entity with whom they engage, and therefore are unable to take their business elsewhere if issues arise. For this reason, when consumer abuses occur in these markets, consumer protection laws and regulations may be particularly important. According to the CFPB, credit reporting and debt collection are the consumer finance markets with by far the most complaints, together accounting for 63% of the total complaints the agency received in 2018 (38% and 25%, respectively).141

Credit Reporting, Credit Bureaus, and Credit Scoring

The consumer data industry collects information on consumers, such as financial payment history data, to predict their future financial product performance.142 This industry includes financial firms who report on consumers' payment behaviors, credit bureaus who collect and store this information, and credit scoring companies that use this data to develop algorithms to predict consumers' future payment behaviors. The three largest credit bureaus—Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion—provide credit reports nationwide.143 The consumer data industry is important because it significantly affects consumer access to financial products or opportunities. For example, negative or derogatory information on a credit report, such as information stating that a consumer has paid late or defaulted on a loan, may influence a lender to deny a consumer access to credit.144

The main statue regulating the credit reporting industry is the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA),145 enacted in 1970. The FCRA requires "that consumer reporting agencies adopt reasonable procedures for meeting the needs of commerce for consumer credit ... in a manner which is fair and equitable to the consumer, with regard to the confidentiality, accuracy, relevancy, and proper utilization of such information."146 Among other things, the FCRA establishes permissible uses of credit reports and imposes certain responsibilities on those who collect, furnish, and use the information contained in consumers' credit reports.

The FCRA also includes consumer protection provisions. Under the FCRA, a lender must advise a consumer when the lender has used their information from a credit reporting agency (CRA) in taking an adverse action (generally a denial of credit) against the consumer.147 That information must be disclosed free of charge. Consumers have a right to one free credit report every year (from each of the three largest nationwide credit reporting providers) even in the absence of an adverse action (e.g., credit denial). Consumers also have the right to dispute inaccurate or incomplete information in their reports. After a consumer alerts a CRA of such a discrepancy, the CRA must investigate and correct errors, usually within 30 days. The FCRA also limits the length of time negative information may remain on credit reports. Negative debt collection information typically stays on credit reports for 7 years, even if the consumer pays in full for the item in collection; information about a personal bankruptcy stays on a credit report for a maximum of 10 years.148

The CFPB has rulemaking and enforcement authorities over all CRAs in connection with certain consumer protection laws, including the FCRA; it also has supervisory authority, or the authority to conduct examinations, over the larger CRAs. In July 2012, the CFPB announced that it would supervise CRAs with $7 million or more in annual receipts, which included 30 firms representing approximately 94% of the market.149

Inaccurate or disputed consumer data within the credit bureaus' reports is an ongoing concern in this market. Inaccurate information in a credit report may limit a consumer's access to credit in some cases or increase the costs to the consumer of obtaining credit in others. In response to this concern, the CFPB has recently encouraged credit bureaus and financial institutions to improve data accuracy in credit reporting. In 2017, the CFPB released a report of its supervisory work in the credit reporting system.150 The report discusses the CFPB's efforts to work with credit bureaus and financial institutions to improve credit reporting in three specific areas: data accuracy, dispute handling and resolution, and furnisher reporting. As the report describes, credit bureaus and financial firms have worked with the CFPB to develop data governance and quality control programs to monitor data accuracy. In addition, the CFPB has encouraged credit bureaus to improve their dispute and resolution processes, including making them easier and more informative for consumers.151

When credit reporting disputes arise, consumers sometimes find it difficult to advocate for themselves because they are not aware of their rights and how to exercise them. According to a CFPB report, some consumers are confused about what credit reports and scores are, find it challenging to obtain credit reports and scores, and struggle to understand the contents of their credit reports.152 The CFPB provides financial education resources on its website to help educate consumers about their rights regarding consumer reporting. The credit bureaus' websites also provide information about how to dispute inaccurate information, and consumers can contact the credit bureaus by phone or mail. However, debates continue regarding whether these efforts are enough to ensure that consumers can effectively advocate for themselves.

Data protection and security are important issues in consumer data reporting, particularly following the announcement, on September 7, 2017, of the Equifax cybersecurity breach that potentially revealed sensitive consumer data information for 143 million U.S. consumers.153 CRAs are subject to the data protection requirements of Section 501(b) of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA).154 Section 501(b) requires the federal financial institution regulators to

establish appropriate standards for the financial institutions subject to their jurisdiction relating to administrative, technical, and physical safeguard—(1) to insure the security and confidentiality of consumer records and information; (2) to protect against any anticipated threats or hazards to the security or integrity of such records; and (3) to protect against unauthorized access or use of such records or information which could result in substantial harm or inconvenience to any customer.155

The FTC has the authority to enforce Section 501(b) against CRAs,156 and it has promulgated rules implementing the GLBA requirement.157 However, because the FTC has little upfront supervisory or enforcement authority, the agency typically only exercises its enforcement authority after an incident has occurred.

Debt Collection and Bankruptcy

When a consumer defaults on a debt, her debt obligations are often collected not by the lender to whom she originally owed the debt, but rather by a third-party debt collector (hereinafter referred to as a debt collector) that by contract receives a share of the amount collected on behalf of the original lender or buys the debt obligation in full.158 In general, a robust debt collection market allows lenders to recoup their losses to the maximum extent possible after a consumer defaults on a loan, leading to lower initial loan costs and more access to credit for consumers.

Many Americans experience debt collection. According to a CFPB survey, about one-third of consumers with a credit bureau file reported being contacted in the last year by at least one creditor or collector trying to collect on one or more debts.159 Consumers with lower incomes and nonprime credit scores were more likely to report experience with debt collection than consumers with higher incomes and prime credit scores.160 In 2018, debt from unpaid loans or other financial services accounted for approximately 40% of debt collection revenue.161 The other 60% of debt collection revenue includes medical,162 telecom, and other retail debt.

The Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA), enacted in 1977, is the primary federal statue regulating the debt collection market and aims "to eliminate abusive debt collection practices by debt collectors."163 Among other things, it prohibits debt collectors from engaging in certain types of conduct (such as misrepresentation or harassment) when seeking to collect debts from consumers, requires that debt collectors disclose certain information to consumers, and grants consumers the right to dispute an alleged debt.164

The Dodd-Frank Act granted the CFPB authority to write regulations to implement the FDCPA, both regarding debt collectors as defined in the FDCPA and those who collect debt related to a consumer financial product service as defined in the Dodd-Frank Act. The CFPB also has enforcement authorities over the debt collection market and supervisory authority, or the authority to conduct examinations, over nonbank firms with more than $10 million in annual receipts from consumer debt collection activities.165

The FDCPA requires that, after a debt collector initially contacts a consumer, the collector must send the consumer a validation notice (generally, a notice disclosing certain information about the debt to the consumer). Thereafter, a debt collector can call, send letters, and use other methods to contact the consumer to collect an alleged debt.166 In general, debt collectors expect that they will collect only a fraction of the face value of any particular debt, knowing that some consumers will never pay back their debt in full. Therefore, when a third-party debt collector contacts a consumer, both parties can negotiate the amount and payment schedule of the debt.167 Although debt collectors are not required to furnish information about the debt to credit bureaus, they may do so. According to the CFPB, debt collectors generally choose not to furnish data to credit bureaus due to the cost and potential legal liability, though most debt collectors furnish data occasionally.168

If a consumer does not settle a debt, the debt owner often has several options, such as seizing the collateral for secured loans (e.g., car, home)169 or garnishing a consumer's wages after obtaining a court order. According to CFPB research, "the cost of filing a claim plays a large role in litigation decisions and varies significantly across jurisdictions based on differences in factors such as filing fees and what types of collections claims can be brought in small claims court."170 More than half of filed suits lead to default judgments in favor of the debt owner, often because consumers fail to appear in court.171

Consumers who cannot pay their debts may seek relief through the federal bankruptcy process, which is generally governed by the Bankruptcy Code.172 In general, the bankruptcy process allows a consumer to enter a court-administered proceeding by which the consumer can discharge certain debts and thus obtain a fresh start. However, consumers may face negative repercussions by choosing bankruptcy, for example, a lower credit score and reduced access to credit for several years afterward. In 2005, Congress enacted the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act (BAPCPA), in response to what some perceived as a high number of consumer bankruptcy filings.173 While BAPCPA made a number of amendments to the Bankruptcy Code, for the purposes of this report, its most notable change was to impose a "means test" to determine whether consumers are eligible for certain relief under the Bankruptcy Code.174 In addition to the federal bankruptcy process, many states limit the length of time consumers are legally obligated to pay a debt.175

Ongoing concerns relating to debt collection include debts incorrectly attributed to consumers or for incorrect amounts; consumers' inability to advocate for themselves through the process; and consumers' inability to avoid abusive practices from debt collectors. According to a CFPB survey, more than half of consumers who had been contacted about a debt in collection reported that there was an error as to at least one such debt, and over a quarter disputed the debt with the debt collector.176 People with higher incomes and older people were more likely than lower-income and younger people to report disputing a debt, although reported errors did not vary significantly based on demographics.177 These verification issues may exist because debt collectors are not required to obtain a debt's full files from the original lender.178 Sometimes, the original lender conveys only basic information to the debt collector unless a consumer disputes the debt, reducing costs for debt collectors.179 In addition, the minimum amount of information that must be included in debt validation notices under FCRA might not be sufficient for some consumers to recognize their debts, according to the CFPB.180

Recent consumer complaints to the CFPB find similar verification issues. In 2018, the most common debt collection complaints to the CFPB asserted that debt collectors had attempted to collect a debt the consumer did not owe (44%); a consumer received insufficient written notification about a debt, such as not enough information to verify the debt or not learning about a debt until it was on a credit report (24%); and general complaints about a debt collector's communications tactics, such as frequent or repeated calls (12%).181 To address some of these concerns, the CFPB recently issued a proposed rule that would clarify what information debt collectors should disclose to consumers and how they should communicate with consumers under FCRA.182

Conclusion

For all of the consumer financial markets described in this report, the societal goal is that each market will create a transparent and competitive price that leads to an efficient market outcome. As described earlier in the report, government policy can potentially correct market failures, such as information asymmetries or behavioral biases, to bring the market to a more efficient outcome, maximizing social welfare. Yet, government policy can lead to unintended consequences as well. Policy changes will typically impose costs and benefits, but these effects can be difficult to calculate in advance of a new law or regulation. It is often challenging to determine whether a policy intervention will help or harm market efficiency.