Introduction

The Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (P.L. 93-288, hereinafter the Stafford Act) authorizes the President to issue a major disaster declaration in response to natural or man-made incidents that overwhelm state, local, or tribal capacities. The declaration makes a wide range of federal activities available to support state and local efforts to respond and recover from the incident. Major disaster declarations also authorize the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to provide grant assistance to state, local, and tribal governments, residences, and certain private nonprofit (PNP) facilities that provide critical services.1

Businesses that suffer uninsured loss as a result of a major disaster declaration are not eligible for FEMA grant assistance, and grant assistance from other federal sources is limited. On some occasions, Congress has provided assistance to businesses through the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program.2 The CDBG program provides loans and grants to eligible businesses to help them recover from disasters as well as grants intended to attract new businesses to the disaster-stricken area. In a few cases, CDBG has also been used to compensate businesses and workers for lost wages or revenues.3 CDBG assistance, however, is not available for all major disasters. Rather, it is used by Congress on a case-by-case basis in response to large-scale disasters. The United States Department of Agriculture and the Department of Commerce are also authorized to provide assistance to certain types of businesses such as agricultural producers or fisheries.4 While these programs are important sources of assistance following a disaster, they are generally limited in scope (available for only certain types of businesses) or provide limited grant amounts. Most businesses will need to apply for a Small Business Administration (SBA) disaster loan if they want assistance from the federal government for uninsured loss resulting from a disaster.5

SBA is authorized to provide grants to SBA resource partners, including Small Business Development Centers, Women's Business Centers, and SCORE (formerly the Service Corps of Retired Executives), to provide training and other technical assistance to small businesses affected by a disaster,6 but is not authorized to provide direct grant assistance to businesses.7

Overview of SBA Business Disaster Loans

As indicated above, federal assistance to businesses that suffer uninsured loss as a result of a disaster is mainly limited to SBA disaster loans. Disaster loans address certain types of loss and fall into two categories: (1) Business Physical Disaster Loans, and (2) Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDL).

If Congress were to replace SBA business disaster loans with a grant program, it might consider providing grants for similar types of loss. Alternatively, Congress might implement a small business disaster grant program and continue to provide loan assistance through the SBA. If that is the case, it might consider how the small business disaster grant program would complement the existing loan program. The following sections describe SBA business disaster loans in more detail.8

Business Physical Disaster Loans

Business Physical Disaster Loans are available to almost any business located in a declared disaster area.9 Business Physical Disaster Loans provide businesses up to $2 million to repair or replace damaged physical property including machinery, equipment, fixtures, inventory, and leasehold improvements that are not covered by insurance.10 Damaged vehicles normally used for recreational purposes may be repaired or replaced with SBA loan proceeds if the borrower can submit evidence that the vehicles were used for business purposes.

Businesses may also apply up to 20% of the verified loss amount for mitigation measures (e.g., grading or contouring of land, relocating or elevating utilities or mechanical equipment, building retaining walls, safe rooms or similar structures designed to protect occupants from natural disasters, or installing sewer backflow valves) in an effort to prevent loss should a similar disaster occur in the future.

Interest rates for Business Physical Disaster Loans cannot exceed 8% per annum or 4% per annum if the business cannot obtain credit elsewhere.11 Borrowers generally pay equal monthly installments of principal and interest starting five months from the date of the loan. Business Physical Disaster Loans can have maturities up to 30 years.

Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDLs)

EIDLs are available to businesses located in a declared disaster area, that have suffered substantial economic injury, are unable to obtain credit elsewhere, and are defined as small by SBA size regulations.12 Size standards vary according to many factors including industry type, average firm size, and start-up costs and entry barriers.13 Small agricultural cooperatives and most private and nonprofit organizations that have suffered substantial economic injury as the result of a declared disaster are also eligible for EIDLs.

Businesses can secure both an EIDL and a Business Physical Disaster loan to rebuild, repair, and recover from economic loss. The combined loan amount cannot exceed $2 million. Interest rate ceilings are statutorily set at 4% per annum or less and loans can have maturities up to 30 years.

Arguments for and Against Small Business Disaster Grants

The following sections outline some of the arguments for and against implementing a business disaster grant program including the rationale for keeping the current federal business disaster policy the same.

Arguments for a Small Business Disaster Grant Program

Throughout the years, Congress has expressed interest and concern for businesses recovering from disasters. More recently, Congress has contemplated whether grants should be made available to small businesses after major disasters. Advocates of a small business disaster grant program might argue that providing grants would address three areas of congressional concern: (1) equity, (2) small business vulnerability to disasters, and (3) protecting the economy.

Equity Concerns

Over the years some have questioned why residences, nonprofit groups, and state and local governments are eligible for disaster grants but not small businesses. Some view the policy as being unfair to businesses. Providing disaster grants to businesses, they argue, would remove this disparity and make federal disaster policy more equitable and uniform across all sectors.

Opponents of providing small business disaster grants might object to the equity argument by pointing out that businesses benefit indirectly from grants provided to state, local, and tribal governments. For instance, repairing and replacing damaged roads and bridges, debris removal, and utility restoration are commonly needed for successful business operations. It is notable too that FEMA reimburses state and local governments for debris removal—even on commercial property.

Vulnerability Concerns

Small business disaster grant advocates could also argue that studies suggest that small businesses are particularly vulnerable to disasters and many fail to fully recover.14 While reports vary on the number of small businesses that fail after a disaster, even the low estimates could be considered significant. According to FEMA, "roughly 40-60% of small businesses fail to reopen following a disaster."15 The Institute for Business and Home Safety found that 25% of businesses that close following a disaster never reopen.16 Businesses that do recover often take a long time to resume operations. A study on businesses in New Orleans recovering from Hurricane Katrina found that 12% of businesses remained closed 26 months after the storm.17 The same study indicated that smaller businesses had lower reopening probabilities than larger ones.18 And while SBA provides low-interest disaster loans with loan maturities up to 30 years for uninsured loss, some see a 30-year loan as an additional burden to full recovery. Finally, proponents argue that the need to recover and reopen quickly is not only important to small businesses—it is also important to local governments because they rely on these businesses for tax revenue. Congress could use small business disaster grants to help vulnerable businesses recover and rebuild following a disaster.

Protecting the Economy

Advocates could also argue that grant assistance could help counteract negative economic outcomes associated with disasters by helping businesses keep people employed and recover from economic loss. When major disasters take place, they not only cause immense damage to public infrastructure, they also severely damage the stock of private capital and disrupt economic activity.19 The typical economic pattern following large-scale disasters consists of large immediate losses of output, income, and employment.20 Small businesses play a significant role in the national economy. For example, in 2013, small businesses employed 56.8 million people (48% of the private workforce) in the United States.21 These small firms accounted for 33.6% of the nation's total known export value22 and produced roughly 46% of the nation's nonfarm gross domestic product (GDP).23

Opponents of a small business disaster grant program could point out, however, that studies suggest that market mechanisms may restore economic order without grant assistance. According to these studies, the long-term economic benefits of rebuilding from a major disaster can offset their initial economic disruption.24 For example, research on Hurricane Sandy recovery found that the storm initially resulted in net negative effects on state GDP, employment, income, and tax revenues. According to the study, spending on large-scale cleanup and repair efforts not only offset, but exceeded the initial economic negative effects.25

Arguments Against Small Business Disaster Grants

Opponents would argue there are three main reasons why disaster grants should not be provided to small businesses: (1) it might encourage businesses to become underinsured for disasters, (2) it would be costly, and (3) the Stafford Act is an inappropriate means to provide disaster grants to businesses.

Underinsured Businesses

Opponents could argue that small businesses are responsible for obtaining adequate insurance coverage to recover from a disaster. To them, providing grants to small businesses could create an incentive for them to be underinsured (or not obtain insurance) to cut costs. Advocates for small business disaster grants might counter argue that other sectors are also responsible for insurance coverage yet are still eligible for grant assistance.

Fiscal Implications

Opponents could also argue that providing disaster grants to small businesses could be very expensive. SBA disaster loans are designed to be repaid, and though the interest rates are relatively low and some of these loans are not repaid due to defaults, the cost to the federal government for providing loans is much less than the cost of providing grants. Grants are not repaid to the federal government.

The Stafford Act

As discussed later in this report, opponents might consider the Stafford Act to be an inappropriate vehicle for providing disaster assistance to businesses. To support this argument, they would point out that Section 101(b) of the Stafford Act states that it "is the intent of the Congress, by this Act, to provide an orderly and continuing means of assistance by the federal government to state and local governments in carrying out their responsibilities to alleviate the suffering and damage which result from such disasters...."26 They may therefore conclude that if the federal government were to provide disaster grants to businesses, those grants should be provided under the Small Business Act or some other authorization statute.

Elements of the arguments for and against small business disaster grants outlined above will be explored in greater detail in "Policy Considerations and Options for Congress."

Historical Developments

Some question why the federal government provides grant assistance to individuals and households, state, local, and tribal governments, and nonprofit organizations, among others, but not to businesses. A review of congressional hearings, bill reports, agency reports, academic journals, and other authoritative sources did not identify specific language explaining why Congress distinguishes between the types of disaster assistance that should be provided to businesses while not applying the same restrictions to other sectors.

It appears that current federal policy on business disaster assistance first emerged in the 1930s. At that time, the United States had no overarching federal disaster policy or permanent program in place to respond to major disasters. Response, repair, and recovery activities were generally organized and carried out under local auspices and financial assistance was typically provided by states, municipalities, churches, and other nonprofit organizations such as the American Red Cross and the Salvation Army.27 When Congress did provide financial assistance, it was generally on an ad hoc basis.28 Further, Congress wanted the measures limited to relieving "human distress and for such things as food, clothing, shelter, medicine and hospitalization" rather the reconstruction of buildings, businesses, or anything else.29

The Great Depression also heightened concerns about federal costs. Thus, Congress sought to keep federal costs to a minimum by limiting assistance to individuals and households, and, to the extent possible, returning the federal expenditures back to the Treasury.30

For example, in 1933, Congress debated whether to provide funding to the American Red Cross (the main source of disaster assistance at that time) in response to an earthquake in Long Beach California. The Red Cross sought the funding because it could not meet assistance needs through its traditional fundraising efforts. Businesses, which were already struggling because of the Great Depression, suffered a great deal of damage as a result of the incident. While sympathetic to struggling businesses, Congress was resolute that federal assistance for the earthquake be limited to immediate needs such as food and clothing. During a hearing before the Subcommittee of House Committee on Appropriations, the Vice Chairman in charge of Domestic Operations for the American Red Cross clarified that Red Cross did not have a role in business recovery:

There will always arise the question as to business rehabilitation, businesses and factories that have been affected. Then, there is the question of the solvency or insolvency of public corporations, schools, school boards, and so forth, and the replacement of their losses. For that reason I made the statement at the outset delimiting the scope of Red Cross work to family problems as against those of business and government.31

Congress decided that it would make disaster loans available to nonprofit organizations with loan maturities not to exceed 10 years through the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC).32 The restriction that limited loans to nonprofit organizations was removed in 1936, and RFC was "authorized to make disaster loans to corporations, partnerships, individuals, and municipalities or other political subdivisions of states and territories."33 The RFC continued to make disaster loans available until Congress dissolved the RFC and transferred its disaster loan authority to SBA in 1953 (P.L. 83-163).

Around the same time, Congress passed the Federal Disaster Relief Act of 1950 (P.L. 81-875). The Disaster Relief Act established a permanent authority that committed the federal government to provide specific types of assistance to states and localities (but not businesses) following a major disaster declaration. It appears that the creation of a separate authority to provide assistance to states and localities may have placed them on a separate policy trajectory from businesses. Though interlaced to a degree, assistance to businesses remained in the form of loans, while the scope and nature of federal assistance to other entities expanded as the Disaster Relief Act was amended in the 1960s, 1970s, and replaced in the 1980s by the Stafford Act.34

Selected Examples of Business Disaster Grants Proposals

The long-standing policy of providing disaster loans for businesses instead of grants has been reexamined by Congress in the last decade. In recent Congresses, legislation has been introduced that would establish business disaster grant programs. These legislative attempts include: (1) the Small Business Owner Disaster Relief Act of 2008 (H.R. 6641) in the 110th Congress, and (2) the Hurricane Harvey Small Business Recovery Grants Act (H.R. 3930) in the 115th Congress.

The Small Business Owner Disaster Relief Act of 2008

H.R. 6641 would have amended Section 406(a)35 of the Stafford Act to allow businesses with 25 or fewer employees to receive grants to repair, restore, or replace damaged facilities. The assistance was limited to $28,000—the maximum amount of assistance a family could receive at that time under Section 408 of the Stafford Act (FEMA's Individuals and Households program).36

H.R. 6641 was referred to the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, Subcommittee on Economic Development, Public Buildings and Emergency Management on July 30, 2008. A hearing on H.R. 6641 provided an opportunity for some to voice their concern over the perceived disparity in disaster assistance. For example, in his testimony before the Subcommittee, Representative Steve King of Iowa stated that "we have structured ... federal government relief in grant form for every sector of our economy ... except for private enterprise, and the ones that are the most vulnerable are small businesses."37 Later in the hearing, Chairwoman Eleanor Holmes Norton of Washington, DC, asked: "how are we to convince for the first time since the Stafford Act was passed ... [that] Congress faced with an extraordinary deficit that this is the time to start giving what amounts to money to private enterprises?"38 To which Representative King stated: "we have justified providing relief for not-for-profits, even some churches who qualify ... and every political subdivision—city, county, state, and of course federal."39 In addition to voicing concerns about the equity of disaster assistance, the hearing also highlighted some of the challenges businesses face when recovering from a disaster, including a lack of capital, revenue gaps, and a weakened ability to generate revenue.

It is possible that some of the programmatic concerns would have been addressed had the bill continued to advance in the legislative process, but the measure saw no further legislative action.

Hurricane Harvey Small Business Recovery Grants Act

H.R. 3930 in the 115th Congress would have established a temporary "Office of Hurricane Harvey Small Business Grants" in the SBA to provide grants to businesses that suffered substantial economic injury as a result of Hurricane Harvey.40 H.R. 3930 would have authorized grants up to $100,000; the SBA Administrator, however, could increase that amount to $250,000 if deemed appropriate. Businesses could use the grants for a wide-range of recovery activities including uninsured property loss, damages or destruction of physical infrastructure, overhead costs, employee wages for unperformed work, temporary relocation, and debris removal. The grants could also be used for insurance deductibles, but not to repay government loans.

H.R. 3930 was introduced in the House of Representatives, but saw no further legislative action.

Policy Considerations and Options for Congress

Implementing a small business disaster grant program may address congressional concerns about disaster relief equity, protecting the economy and vulnerable businesses. A business grant program, however, could have some unintended policy consequences. Some of the considerations Congress may contemplate for a potential small business disaster grant program include: (1) preventing the duplication of administrative functions and benefits; (2) the selection of the authorization statute; (3) whether (and what type of) declarations and designations will put the disaster grant program into effect; (4) what size businesses should be eligible for disaster grant assistance; and (5) the types of activities eligible for grant assistance.

In addition, Congress could explore alternative options to a small business disaster grant program that could also address business disaster recovery concerns including (1) loan forgiveness; (2) reduced interest rates; and (3) measures that could help small (and large) businesses develop continuity and disaster recovery plans to help them prepare for and recover from disasters.

Preventing Duplication of Administrative Functions and Benefits

Preventing duplication of administrative functions and benefits would likely be of concern if Congress authorized a small business disaster grant program. Duplication of administrative functions occurs when an office or staff at two or more federal entities performs the same types of operations. This type of duplication might be addressed through program consolidation. In the context of disaster assistance, duplication of benefits occurs when compensation from multiple sources exceeds the need for a particular recovery purpose.41

Preventing Duplication of Administrative Functions

To prevent duplication of administrative functions Congress could opt to authorize the implementation of a new small business disaster grant program by either SBA or FEMA, but not both. The selection and authorization debate could, to some extent, resemble policy discussions Congress had during FEMA's formation. In 1978, President Jimmy Carter signed Executive Order 12127 which merged many disaster-related responsibilities of separate federal agencies into FEMA. Congress determined that SBA would continue to provide disaster loans through the Disaster Loan Program rather than transfer that function to FEMA. At the 1978 hearing before a subcommittee of the Committee on Government Operations, Chairman Jack Brooks questioned the rationale for keeping the loan program outside of FEMA. According to James T. McIntyre, Director, Office of Management and Budget (OMB), the rationale was as follows:

[O]ne of the fundamental principles underlying this proposal is that whenever possible emergency responsibilities should be an extension of the regular missions of federal agencies. I believe the Congress also subscribed to this principle in considering disaster legislation in the past. The Disaster Relief Act of 1974 provides for the direction and coordination, in disaster situations, of agencies which have programs which can be applied to meeting disaster needs. It does not provide that the coordinating agency should exercise direct operational control.... [I]f the programs ... were incorporated in the new agency we would be required to create duplicate sets of skills and resources.... [S]ince the Small Business Administration administers loan programs other than those just for disaster victims, both the SBA and the new agency [FEMA] would have to maintain separate staffs of loan officers and portfolio managers if the disaster loan function were transferred to the new Agency.... [O]ne of our basic purposes for reorganization ... would be thwarted if we were to have to maintain a duplicate staff function in two or more agencies.42

Similarly, Congress may consider whether issuing small business disaster grants either through FEMA or SBA would duplicate skills and resources in one or the other agency. Congress could examine existing administrative functions at each agency and determine which most closely aligns with a potential small business disaster grant program.

Preventing Duplication of Benefits

In addition to duplication of administrative functions, duplication of benefits is more likely to occur as more recovery resources become available. The range of resources can include insurance payouts, state and local government assistance, charitable donations from private institutions and individuals, as well as certain forms of federal assistance. While SBA disaster loans must be repaid, they are still considered a benefit. Duplication of benefits sometimes happens at the individual and household level wherein a range of resources become available to assist in the response, recovery, and rebuilding process. It could be inferred that providing businesses with disaster loans and grants could lead to the same outcome.

Instances of duplication could increase if businesses become eligible for loans and grants. Section 312 of the Stafford Act requires that disaster assistance is distinct and not duplicative. Under Section 312

The President, in consultation with the head of each Federal agency administering any program providing financial assistance to persons, business concerns, or other entities suffering losses as a result of a major disaster or emergency, shall assure that no such person, business concern, or other entity will receive such assistance with respect to any part of such loss as to which he has received financial assistance under any other program or from insurance or any other source.43

FEMA and SBA use a computer matching agreement (CMA) in the application process to share real-time disaster assistance to prevent duplication of benefits.44 Despite the use of such mechanisms, duplication can still occur. Under 44 C.F.R. §206.191, a federal agency providing disaster assistance is responsible for identifying and rectifying instances of duplicative assistance. If identified, the recipient is required to repay the duplicated assistance.

In some cases the federal government does not identify instances of duplication, and the improper payments are never recovered. In others cases, it may take a prolonged period of time to identify the duplication and the repayment notification may come as a surprise to disaster victims who did not realize they have to repay their assistance if that assistance is found to be duplicative. The payment may be an additional financial and emotional burden if the grantee has spent all of their assistance proceeds on recovery needs.

If Congress authorizes a small business disaster grant program, it may consider conducting investigations and holding hearings to help determine which authorization statute would be best at reducing duplication of administrative functions and benefits.

Authorization Statute

Congress would need to identify an authorizing statute should it create a disaster grant program for businesses. Congress could decide to authorize a small business disaster grant program under the Stafford Act (as was proposed by H.R. 6641), the Small Business Act, or other statute.

Authorization Under the Stafford Act

FEMA would most likely be solely responsible for administering a small business disaster grant program if it were authorized under the Stafford Act. Having FEMA administer the program may have a number benefits. First, FEMA already has grant processing operations in place. It might be relatively easier to expand the operations to include small businesses disaster grants rather than establishing new grant-making operations within SBA. Second, having FEMA administer the small business disaster grant program may help limit duplication of administrative functions between FEMA and SBA. Third, FEMA has an existing account called the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) that receives annual and supplemental appropriations to fund its disaster assistance programs. DRF appropriations could be increased to pay for small business disaster grants. In contrast, Congress would likely need to make statutory changes to SBA's existing disaster loan account, or authorize a new account, if a small business disaster grant program was administered by SBA.

Authorization Under the Small Business Act

SBA would probably administer a small business disaster grant program if it were authorized under the Small Business Act. As mentioned previously, SBA currently has authority under the Small Business Act to provide grants to SBA resource partners to provide training and other technical assistance to small businesses affected by a disaster, but it does not have specific authority to provide disaster grants to businesses or individuals.

Congress could decide to have SBA administer the program because it already has a framework in place to evaluate business disaster needs and disaster loan eligibility. Congress may need to make statutory changes to SBA's disaster loan account or authorize a new account to receive appropriations for disaster grants. Another legislative approach Congress could consider is allowing SBA to draw funds from FEMA's DRF to pay for small business disaster grants. Some may question this funding approach because it would allow SBA to draw funds from another agency's account. The funding arrangement could also be problematic if DRF became low on funds and there are competing priorities for scarce resources.

Declarations and Designations

Under current laws, FEMA grants and SBA disaster loans are triggered by a "declaration" under the Stafford Act, an SBA declaration, or both. The type (or category) of declaration determines what types of federal assistance are made available. Declarations are a necessary, but not sufficient condition for federal disaster assistance to businesses. The types of assistance made available are further influenced by the "designations" contained within the declaration. Declarations and designations may have a similar influence on a small business disaster grant program. The following describes the nexus between federal disaster assistance and declarations in more detail.

Stafford Act Declarations

If the current declaration framework were applied to a small business disaster grant program, relatively fewer businesses may be eligible for grant assistance if authorized under the Stafford Act compared to the Small Business Act. This is because the thresholds and criteria used to make Stafford Act declaration determinations are relatively higher than the ones used to provide disaster assistance under the Small Business Act.

The Stafford Act authorizes the President to issue major disaster declarations that provide states, tribes, and localities with a range of federal assistance in response to natural and human-caused incidents.45 Each presidential major disaster declaration includes a designation. The designation determines what FEMA grants are available for the incident. It also designates which counties are eligible for the grants.46 The potential types of FEMA grant assistance include (1) Public Assistance (PA) for infrastructure repair; (2) Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) grants to lessen the effects of future disaster incidents; and (3) Individual Assistance (IA) for aid to individuals and households.47 Under FEMA regulations:

The Assistant Administrator for the Disaster Assistance Directorate has been delegated authority to determine and designate the types of assistance to be made available. The initial designations will usually be announced in the declaration. Determinations by the Assistant Administrator for the Disaster Assistance Directorate of the types and extent of FEMA disaster assistance to be provided are based upon findings whether the damage involved and its effects are of such severity and magnitude as to be beyond the response capabilities of the state, the affected local governments, and other potential recipients of supplementary federal assistance. The Assistant Administrator for the Disaster Assistance Directorate may authorize all, or only particular types of, supplementary federal assistance requested by the governor.48

The "findings" referenced above are known as "factors" that are used by FEMA to evaluate a governor's or chief executive's request for a major disaster declaration and make IA and PA recommendations to the President (a full description of the factors can be located in the Appendix). While all major disaster declarations have HMGP designations, not all declarations designate IA and PA. In rare cases, only IA and HMGP are designated. More commonly, PA and HMGP are designated (these are sometimes referred to as "PA-only" major disaster declarations).49 This is because major disasters often cause greater damage to public infrastructure relative to damaged households.

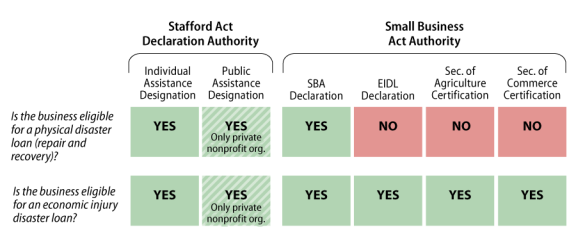

Stafford Act declarations also trigger the SBA Disaster Loan Program and the types of loans are determined by the designation. If IA is designated, then all SBA disaster loans types are made available to eligible businesses. If PA is designated, then only private nonprofit organizations are eligible for disaster loans (see Figure 1). In other words, most private businesses would not be able to obtain a disaster loan under a PA-only major disaster declaration.

If the existing declaration framework is applied to a small business disaster grant program, then small businesses would generally be eligible for disaster grants for Stafford Act major disaster declarations that included an IA designation. By comparison, disaster loans would likely only be made available to private nonprofit organizations under a PA-only declaration.

Some might be concerned that too few businesses would be eligible for disaster grants if the existing declaration and designation framework were applied to a small business disaster grant program. They may also question the relevance of the IA designation because the factors used to determine IA do not evaluate business damages or economic loss. For example, it is conceivable that an incident could cause significant damage to public infrastructure and businesses but not to households. Consequently, businesses could be denied assistance because it was determined that damages to residences did not warrant assistance to individuals and households.

There are, however, at least four reasons why some might argue that the existing declaration and designation framework should be applied to a small business disaster grant program:

- 1. It could help ensure that small business disaster grants were only provided for large-scale incidents.

- 2. It could help limit grant costs because not all declarations would trigger small business disaster grants.

- 3. Applying the declaration and designation framework uniformly to the grant and loan programs would align the two programs and reduce the potential for administrative confusion or duplication.

- 4. Conversely, using different designations could create a perceived disparity between the loan and grant programs because some business owners may question why grants are available for some major disasters (because they are designated IA and PA), but not others (because they have PA-only designations).

If Congress authorized a small business disaster grant program under the Stafford Act, it could consider using the existing declaration and IA designation framework used to trigger eligibility for the SBA Disaster Loan Program. This would align the implementation of the two programs and potentially smooth administrative processes and potentially limit costs.

An alternative policy option Congress might consider is a "business designation" rather than existing designations to determine whether the incident warrants a grant, a loan, or both. The business designation could use a separate set of factors or criteria similar to the ones FEMA currently uses to evaluate declaration requests and make IA and PA recommendations. This could align the designation with damages that are specific to small businesses.

SBA Declarations

Congress could consider using SBA declarations to provide disaster grants to small businesses rather than Stafford Act declarations. The following describes how SBA declarations are used to make disaster loans available and examines the potential policy implications of using the same structure to provide disaster grants to small businesses.

The SBA Administrator has authority under the Small Business Act to make two types of disaster declarations: (1) a physical disaster declaration (commonly referred to as an "SBA declaration"), and (2) an Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) declaration (see Figure 1). Each declaration could make certain forms of assistance available if SBA disaster declarations were to be applied to a small business disaster grant program:

- 1. The SBA Administrator may issue a physical disaster declaration in response to a gubernatorial request for assistance. This type of declaration is often made for relatively smaller incidents. The criterion used to determine whether to issue this type of declaration is generally the presence of at least 25 homes or businesses (or some combination of the two) that have sustained uninsured losses of 40% or more in any county or other smaller political subdivision of a state or U.S. possession.50

When the SBA Administrator issues a physical disaster declaration, both SBA disaster loan types become available to eligible homeowners, renters, businesses of all sizes, and nonprofit organizations within the disaster area or contiguous counties and other political subdivisions (see Figure 1).

If SBA physical disaster declarations were to be applied to a small business disaster grant program, the grants could be made available to small businesses for incidents that do not meet the damage threshold of a major disaster declaration under the Stafford Act. - 2. The SBA Administrator may make an EIDL declaration when SBA receives a certification from a state governor that at least five small businesses have suffered substantial economic injury as a result of a disaster. Alternatively, the SBA Administrator may issue an EIDL declaration based on the determination of a natural disaster by the Secretary of Agriculture.51 The SBA Administrator may also issue an EIDL declaration based on the determination of the Secretary of Commerce that a fishery resource disaster or commercial fishery failure has occurred. Only EIDLs are available under this type of declaration (see Figure 1).

EIDL assistance helps businesses meet financial obligations and operating expenses that could have been met had the disaster not occurred. Loan proceeds can only be used for working capital necessary to enable the business or organization to alleviate the specific economic injury and to resume normal operations. The assistance is designed to help businesses that did not suffer direct damages, but rather businesses that have suffered economic loss as a result of an incident. For example, disasters such as hurricanes can disrupt tourism. In such cases, there may have been some businesses that did not suffer direct damages, but still lost tourism revenue as a result of the hurricane.

If EIDL declarations were to be applied to a small business disaster grant program, the grants could be used to provide similar economic assistance to businesses suffering from economic loss as a result of a disaster.

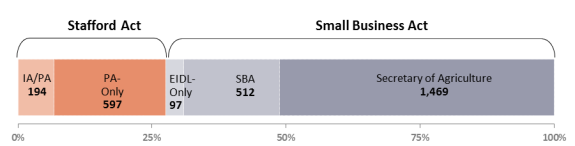

A comparison of Stafford Act declarations (including designations) and SBA declarations from 2008 to 2017 provides context to the SBA declarations outlined above. As shown in Figure 2 and Table 1, during this period, 2,869 declarations were issued under the Stafford Act and the Small Business Act. A total of 791 declarations were issued under the Stafford Act. Of these, 194 (6.8% of total declarations) included IA and PA assistance, while 597 (20.8% of total declarations) were PA-only.

In contrast, during the same period, a total of 2,078 (72.4%) declarations were issued under the Small Business Act. Of these, 512 (17.8% of total declarations) were SBA physical disaster declarations, 97 (3.4%) were EIDL declarations, and 1,469 (51.2%) were EIDL declarations based on the determination of a natural disaster by the Secretary of Agriculture. There were no declarations issued during the 10-year period based on the determination of the Secretary of Commerce that a fishery resource disaster or commercial fishery failure had occurred.52

|

Stafford Act |

Small Business Act |

||||||

|

IA/PA |

PA-Only |

Secretary of Commerce |

EIDL-Only |

SBA |

Secretary of Agriculture |

Total |

|

|

Total |

194 |

597 |

0 |

97 |

512 |

1,469 |

2,869 |

|

FY2008 |

37 |

53 |

0 |

7 |

55 |

0 |

152 |

|

FY2009 |

25 |

57 |

0 |

15 |

40 |

149 |

286 |

|

FY2010 |

17 |

80 |

0 |

15 |

51 |

133 |

296 |

|

FY2011 |

36 |

95 |

0 |

9 |

60 |

134 |

334 |

|

FY2012 |

14 |

64 |

0 |

5 |

51 |

232 |

366 |

|

FY2013 |

11 |

64 |

0 |

13 |

57 |

185 |

330 |

|

FY2014 |

7 |

46 |

0 |

9 |

39 |

157 |

258 |

|

FY2015 |

11 |

42 |

0 |

3 |

42 |

156 |

254 |

|

FY2016 |

13 |

42 |

0 |

12 |

64 |

157 |

288 |

|

FY2017 |

23 |

54 |

0 |

9 |

53 |

166 |

305 |

Source: Data provided by SBA. Figure created by CRS.

The following applies various types of declarations and designations to a potential small business disaster grant program to the above data to draw some inferences on how many businesses might get grants in certain situations.

- If the small business disaster grant program is only triggered by Stafford Act declarations that designate IA and PA, then roughly 6.8% of the declarations (194) issued in Figure 2 and Table 1 would have made disaster grants available to small businesses. That could be a concern for those who want to provide small business grants for incidents that are too small to qualify for assistance under the Stafford Act. As mentioned previously, SBA declarations often provide assistance to incidents that impact a locality or a region but do not cause enough state-wide damage to warrant a major disaster declaration under the Stafford Act.

- If the small business disaster grant program is triggered by the SBA Administrator issuing a physical disaster declaration, then roughly 17% of the declarations (512) issued in Figure 2 and Table 1 would have made disaster grants available to small businesses. This type of declaration could arguably make more incidents eligible for grant assistance because the 512 incidents in Figure 2 and Table 1 were presumably issued for incidents that did not meet the per capita threshold for a major disaster declaration under the Stafford Act. It should be noted, however, that the number of grants made available under an SBA Administrator physical disaster declaration would likely depend on whether the grants would only provide assistance for repairing and rebuilding damaged structure or if they would also provide assistance for economic loss.

- Policymakers could consider making the grants available through either an SBA Administrator physical declaration or an EIDL declaration so that the grants could be used for repairs and rebuilding or for economic loss. If so, then 2,078 declarations during the time period could have made the small business disaster grants available.

- It could be argued that the greatest number of businesses would benefit from small business disaster grants by applying the existing declaration framework under the combined authorities and making the grants available for either physical damages or economic loss. In other words, the same conditions under which SBA disaster loans are made available. Doing so would make small business disaster grants available in all of the declarations in Figure 2 and Table 1 with the exception of the PA-only Stafford Act declarations, under which only private nonprofit organizations are eligible (see Figure 1).

While some may favor making small business disaster grants available for a wide-range of incidents others may want to limit their use. For example, those concerned about the cost implications of a small business disaster grant program may prefer Stafford Act declarations over SBA declarations. As mentioned previously, the thresholds used to determine SBA declarations are lower and generally based on (1) at least 25 homes or businesses (or some combination of the two) sustaining uninsured losses of 40% or more in any county or other smaller political subdivision of a state or U.S. possession; or (2) at least three businesses in the disaster area sustaining uninsured losses of 40% or more of the estimated fair replacement value of the damaged property (whichever is lower). The lower thresholds help provide disaster loans for incidents that are locally damaging, but do not cause enough widespread damage to warrant a major disaster declaration.

In contrast, the threshold used by FEMA under the Stafford Act to a recommend major disaster declaration is significantly higher. In general, public infrastructure damages must meet or exceed $1.43 per capita (based on the most recent census figures) to be recommended for major disaster assistance.53 Applying the per capita threshold to a small business disaster grant program could help ensure that grants are only provided in cases of large-scale disasters.

SBA declaration thresholds might be lower than FEMA thresholds because federal costs associated with loans (which are supposed to be repaid) are less than grants. If costs are a concern, policymakers might consider using criteria similar to FEMA's per capita threshold used for major disaster declarations to issue small business disaster grants.

Finally, another factor to consider is whether the declaration is properly aligned with the agency administering the small business disaster grant program. For example, it could be problematic if small business disaster grants are triggered by SBA declarations but administered by FEMA. SBA would essentially be putting another agency's program into effect. Consequently, it could be argued that a small business disaster grant program should be administered by FEMA if Stafford Act declarations are used to trigger the program, or administered by SBA if SBA declarations are used to put the program into effect.

Eligible Recovery Activities

The small business disaster grant program proposed by H.R. 6641 would have provided grants to "private business damaged or destroyed by a major disaster for the repair, restoration, reconstruction, or replacement of the facility and for the associated expenses incurred by the person." Congress could consider similar legislative language if it authorized a small business disaster grant program, or it may wish to develop a detailed list of what damage types and economic loss amounts would be eligible for grant assistance. Similarly, Congress could also consider whether grants could be used for economic loss and/or mitigation measures.

Grants for Economic Loss

As mentioned previously, in some cases a disaster can disrupt services and create economic hardship for businesses without causing structural damages. SBA EIDL provides businesses with up to $2 million in loans to help meet financial obligations and operating expenses that could have been met had the disaster not occurred. These loan proceeds can only be used for working capital necessary to enable the business or organization to alleviate the specific economic injury and to resume normal operations. Loan amounts for EIDLs are based on actual economic injury and financial needs, regardless of whether the business suffered any property damage.

Some may suggest that small business disaster grants should be limited to small businesses that need assistance to repair and rebuild their business. Others may think that grants should also be provided for economic loss. For example, as mentioned previously H.R. 3930 authorized grants for business interruption, overhead costs, and employee wages as well as for rebuilding and repairs. If Congress were to authorize a small business disaster grant program, it may also consider whether the grants should be available for economic loss or limit them to specific types of damage.

Mitigation

Businesses obtaining an SBA physical disaster loan may use up to 20% of the verified loss amount for mitigation measures (e.g., grading or contouring of land; relocating or elevating utilities or mechanical equipment; building retaining walls, safe rooms, or similar structures designed to protect occupants from natural disasters; or installing sewer backflow valves) in an effort to prevent loss should a similar disaster occur in the future.

If Congress decided to allow small businesses that receive a disaster grant to use the funds for mitigation purposes, it could limit those expenditures to a percentage of the total grant amount, or it could allow the entire grant to be used for mitigation measures.

In addition, if Congress decided to allow disaster grants to be used for mitigation, Congress could consider whether to provide the grant prior to a disaster or without a declaration. For example, Congress could model small business mitigation grants on the Pre-Disaster Mitigation pilot program. P.L. 106-2454 amended Section 7(b)(1) of the Small Business Act to include a Pre-Disaster Mitigation pilot program administered by SBA during fiscal years 2000 through 2004. The program allowed SBA to make low-interest (4% or less) fixed-rate loans of no more than $50,000 per year to small businesses to implement mitigation measures (such as relocating utilities, grading, and building retaining or sea walls) designed to protect the small business from future disaster-related damage.

Business Size Considerations

Congress may consider business size as a criterion for receiving small business disaster grants as a means to target the assistance to businesses of specific sizes. One option could be using SBA's size standards.

The SBA uses two measures to determine if a business qualifies as small for its loan guaranty and venture capital programs: industry specific size standards or a combination of the business's net worth and net income. For example, the SBA's Small Business Investment Company (SBIC) program allows businesses to qualify as small if they meet the SBA's size standard for the industry in which the applicant is primarily engaged, or a maximum tangible net worth of not more than $19.5 million and average after-tax net income for the preceding two years of not more than $6.5 million.55 All of the company's subsidiaries, parent companies, and affiliates are considered in determining if it meets the size standard.56 For contracting purposes, firms are considered small if they meet the SBA's industry specific size standards.57 Overall, the SBA currently classifies about 97% of all employer firms as small. These firms represent about 30% of industry receipts.

The SBA's industry size standards vary by industry, and are based on one of the following four measures: the firm's (1) average annual receipts in the previous three years, (2) number of employees, (3) asset size, or (4) for refineries, a combination of number of employees and barrel per day refining capacity. Historically, the SBA has used the number of employees (ranging from 50 or fewer to no more than 1,500 employees) to determine if manufacturing and mining companies are small and average annual receipts (ranging from no more than $5.5 million per year to no more than $38.5 million per year) for most other industries.

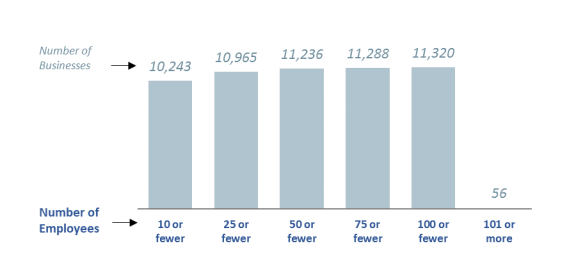

Congress, however, may want to limit disaster grant assistance to small businesses that have fewer employees that are particularly vulnerable to disaster. For example, it could consider providing grants only to businesses of 10 or fewer employees to target "mom and pop shops." As mentioned previously, H.R. 6641 (the Small Business Owner Disaster Relief Act of 2008) would have allowed businesses with 25 or fewer employees to receive grants to repair, restore, or replace damage facilities. Based on data compiled by SBA on business disaster loan applications from FY2013 to FY2017, Figure 3 provides a rough estimate of how many businesses over a five-year period could potentially receive a small business disaster grant under several different size standards.

|

Figure 3. SBA Disaster Assistance Business Loan Applications, by Employee Number FY2013-FY2017 |

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS using data from SBA. |

Based on the FY2013 through FY2017 SBA data, if small business disaster grants were limited to businesses of 10 employees or fewer, roughly 10,000 businesses over a five-year period could be eligible for a small business disaster grant. Over that same time period, nearly 11,000 small businesses could be eligible if the cap were 25 employees or fewer employees. That number would not change substantially if the cap were 50, 75, or 100 or fewer employees (see Figure 3).

Finally, SBA applications for disaster loans currently rely on self-reporting of their number of employees. Congress may consider whether this data should be verified by SBA, or if doing so might inappropriately delay the receipt of the grant.

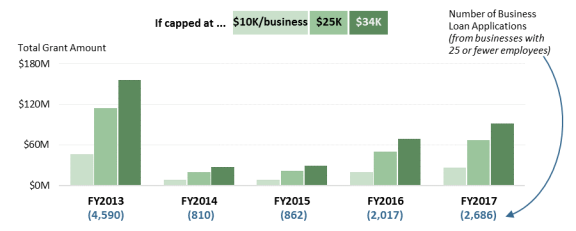

Grant Amounts

H.R. 6641 would have capped small business disaster grants at the maximum amount of assistance a family could receive from FEMA's Individuals and Households program (currently $34,900). Error! Reference source not found. and Table 2 provide cost estimates based on businesses of 25 or fewer employees that applied for disaster loans from FY2013 to FY2017. Based on the data, if disaster grants were capped at $35,000, and all of the businesses that received a loan received a grant instead, the grants would have totaled roughly $384 million. If capped at $25,000, the grants would have totaled roughly $274 million. Finally, if capped at $10,000, the grants would have totaled roughly $110 million.

|

Figure 4. SBA Disaster Assistance Business Loan Applications, by Employee Number FY2013-FY2017 |

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS using data from SBA. |

|

Year |

Numb. of Business Loan Applications From businesses with 25 or fewer employees |

Disaster Grant Amount $10k |

Disaster Grant Amount $25k |

Disaster Grant Amount $35k |

|

FY2013 |

4,590 |

$45,900,000 |

$114,750,000 |

$160,650,000 |

|

FY2014 |

810 |

$8,100,000 |

$20,250,000 |

$28,350,000 |

|

FY2015 |

862 |

$8,620,000 |

$21,550,000 |

$30,170,000 |

|

FY2016 |

2,017 |

$20,170,000 |

$50,425,000 |

$70,595,000 |

|

FY2017 |

2,686 |

$26,860,000 |

$67,150,000 |

$94,010,000 |

|

Total |

10,965 |

$109,650,000 |

$274,125,000 |

$383,775,000 |

Source: Data provided by SBA.

If Congress authorizes a small business disaster grant program, it could consider capping the amount based on Section 408 of the Stafford Act, or some other amount. Congress may also decide to examine business recovery costs to ensure grant amounts are appropriate for business recovery needs.

Business Disaster Grant Pilot Program

One potential approach Congress could consider is creating a pilot program which could be used to evaluate the program's effectiveness and costs. This information could be used to help determine if the program should be made permanent.

For example, Congress established a Pre-Disaster Mitigation pilot program to be administered by SBA during fiscal years 2000 through 2004 (P.L. 106-24).58 The program authorized SBA to issue low-interest (4% or less) fixed-rate loans of no more than $50,000 per year to small businesses to implement mitigation measures (such as relocating utilities, grading, and building retaining or sea walls) designed to protect the small business from future disaster-related damage. Congress could consider implementing a similar pilot program that would provide disaster grants to small businesses over a specified period of time.

To some, a pilot program would be a more cautious approach to implementing a small business disaster grant program. If Congress determined that the grant program was too costly or ineffective, it could decide not to reauthorize the program.

Alternatives to a Disaster Grant Program

Some may suggest that rather than providing small businesses with disaster grants, Congress could explore alternative methods for helping small businesses recover from a disaster. Some alternative methods include loan forgiveness, decreased disaster loan interest rates, and providing assistance to help businesses develop continuity and disaster response plans.

Loan Forgiveness and Decreased Interest Rates

Congress could consider authorizing loan forgiveness to businesses under certain circumstances. Loan forgiveness is rare, but has been used in the past to help businesses that were having difficulty repaying their loans. For example, loan forgiveness was granted after Hurricane Betsy, when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Southeast Hurricane Disaster Relief Act of 1965.59 Section 3 of the act authorized the SBA Administrator to grant disaster loan forgiveness or issue waivers for property lost or damaged in Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi as a result of the hurricane. The act stated that

to the extent such loss or damage is not compensated for by insurance or otherwise, (1) shall at the borrower's option on that part of any loan in excess of $500, (A) cancel up to $1,800 of the loan, or (B) waive interest due on the loan in a total amount of not more than $1,800 over a period not to exceed three years; and (2) may lend to a privately owned school, college, or university without regard to whether the required financial assistance is otherwise available from private sources, and may waive interest payments and defer principal payments on such a loan for the first three years of the term of the loan.60

Congress could also consider reducing interest rates for businesses under specific circumstances or for specific types of disasters. Interest rate ceilings for business physical disaster loans are statutorily set at 8% per annum or 4% per annum if the applicant is unable to obtain credit elsewhere.61 The interest rate ceiling for EIDL is 4% per annum.62 Interest floors have not been established in statute.

Providing relief to businesses through the use of reduced interest rates or loan forgiveness as opposed to grants may have the following advantages: (1) they could provide Congress with a flexible method to provide assistance to struggling businesses that can be applied on a case-by-case basis; (2) they would likely be less expensive than grants; and (3) they may reduce the possibility of duplication of benefits between grants and loans.

On the other hand, it could be argued that providing relief to businesses through reduced interest rates or loan forgiveness as opposed to grants may not provide timely assistance because providing relief on a case-by-case basis would require Congress to debate and pass legislation before the relief could be provided. There may also be concern this approach could be applied too arbitrarily.

Grants for Continuity and Disaster Response Plans

Research indicates that many businesses do not have contingency or disaster recovery plans. For example, a survey of Certified Public Accounting (CPA) firms located on Staten Island, NY, indicated that only 7% of the respondents had a formal continuity or disaster recovery plan in place prior to Hurricane Sandy and nearly 42% of those firms that had a formal continuity or disaster recovery plan admitted that they never tested their plan. Approximately 40% had an informal plan that had been discussed but not documented. More than half of the responding firms did not have a contingency or disaster recovery plan. Of those that did not have any type of a plan, 60% thought the plans were unnecessary and 20% said that establishing a plan was too time-consuming.63

Congress could investigate methods that would incentivize businesses to develop contingency and disaster recovery plans. This could be done through new programs or through existing ones such as FEMA's Ready Business Program which is designed to help businesses plan and prepare for disasters by providing businesses various online toolkits that can help them identify their risks and develop a plan to address those risks.64 Congress could also investigate the extent to which the Ready Business Program is collaborating with SBA's efforts to help businesses with emergency preparedness.65

Similarly, Congress could consider the pros and cons of providing grants to businesses to help them plan and prepare for disasters. For example, providing grants for this purpose could be more expensive than mitigation loans, but cost less than a small business disaster grant program designed to assist businesses following a disaster. Advocates for mitigation grants could further argue that providing grants for mitigation rewards businesses that take the initiative to plan ahead for potential disasters and could reduce, as least to some extent, future costs. Opponents, on the other hand, might believe that existing mitigation programs are sufficient.

Concluding Observations

Congress has contemplated how to help businesses rebuild and recover from disasters for nearly a century. Historically, the federal policy for providing disaster assistance to businesses has primarily been limited to low-interest loans. While disaster loans have been instrumental in helping business recover from incidents, over the years Congress has considered whether grant assistance might be needed in addition to, or instead of business disaster loans.

Changing the federal government's disaster policy approach to businesses could be complex and require careful decisionmaking. Steps would need to be taken to avoid and remedy potential grant and loan duplication. Congress would also have to determine under what circumstances and situations the grant program would be put into effect. Eligibility requirements would need to be developed to determine under what situations and circumstances grants would be provided as well as what types of business should be eligible to receive grants. Similarly, Congress might consider whether grants could be used for rebuilding, mitigation, or economic loss, in addition to other recovery activities. In addition to these concerns and others, Congress may want to investigate the potential cost implications of a small business disaster grant program.

Alternatively, Congress could leave the current policy in place. Those advocating no change are generally supportive of the view that federal disaster assistance should be supplemental in nature and that private insurance and access to low-interest loans should remain the primary means of helping small businesses recover after a disaster.

Appendix. Public Assistance and Individual Assistance Factors

Public Assistance Factors

Estimated Cost of the Assistance

Estimated cost of assistance is perhaps the most important factor FEMA considers when evaluating whether a governor's or chief executive's request warrants PA because it is a strong indicator of whether 'the situation is of such severity and magnitude that an effective response is beyond the capacities of the State and affected local governments."66 FEMA generally relies on two thresholds to evaluate whether to recommend PA. The first threshold is $1 million in public infrastructure damages. This threshold is set "in the belief that even the lowest population states can cover this level of public assistance damages."

The second threshold used by FEMA is determined by multiplying the state's population (according to the most recent census) by a specified statewide per capita impact indicator—currently $1.43.67 In general, FEMA will recommend a major disaster declaration that includes PA if public infrastructure damages exceed $1 million and meet or exceed $1.43 per capita. The underlying rationale for using a per capita threshold is that tax revenues that support a state's disaster response capacity should be sufficient if damages and costs fall under the per capita amount.

Localized Impacts

FEMA also considers impacts to localities (e.g., counties, parishes, boroughs). While capacity to respond to, and recover from, an incident are evaluated on the state level, PA and IA are provided only to the specific counties designated in a declaration. As specified in FEMA regulations

The Assistant Administrator for the Disaster Assistance Directorate also has been delegated authority to designate the affected areas eligible for supplementary federal assistance under the Stafford Act. These designations shall be published in the Federal Register. An affected area designated by the Assistant Administrator for the Disaster Assistance Directorate includes all local government jurisdictions within its boundaries.68

To this end, FEMA uses a countywide per capita impact indicator of $3.61 per capita in infrastructure damage to assess localized impacts.69 In general, it is expected that a locality that meets or exceeds the $3.61 per capita threshold will be designated by FEMA for PA funding.

Insurance Coverage

Insurance coverage is considered in PA determinations when reviewing a governor's or tribal chief executive's request for major disaster assistance. As part of the assessment of disaster related damage, FEMA subtracts the amount of insurance coverage that is in force or that should have been in force as required by law and regulation at the time of the disaster from the total estimated eligible cost of PA for units of government and certain private nonprofit organizations.

Hazard Mitigation

FEMA encourages hazard mitigation efforts by considering how previous measures may have decreased the overall damages and costs following an incident. This could include rewarding states that have a statewide building code.70 If the requesting state can prove, by way of cost-benefit analyses or other related estimates, that its per capita amount of infrastructure damage falls short of the statewide per capita impact threshold due to mitigation efforts, FEMA will consider that favorably in its recommendation to the President. In these instances, FEMA may also consider whether the mitigation work has been principally financed with previous FEMA disaster assistance funding through the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP), through the Pre-Disaster Mitigation (PDM) program, or by state or local resources.71

Recent Multiple Disasters

If a state or tribal nation has suffered multiple disasters—whether declared or not—in the previous 12 months, FEMA considers the financial and human toll of those recent incidents in its consideration of whether to recommend PA. For example, if a state has responded on its own to a series of tornadoes, FEMA may consider a request for a declaration more favorably than they would have otherwise.

Programs of Other Federal Assistance

FEMA also considers whether other federal disaster assistance is available when reviewing a major disaster request. In some cases, other federal programs are arguably more suitable for addressing the types of damage caused by an incident. For example, damage to federal-aid roads and bridges are eligible for assistance under the Emergency Relief Program of the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA).72 Other federal programs may have more specific authority to respond to certain types of disasters, such as damage to agricultural areas. Assistance may also be provided under authorities separate from the Stafford Act with or without a Stafford Act declaration. For example, assistance for droughts is frequently provided through authorities of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) can provide assistance to states in response to a public health threat without the President's involvement via Stafford Act authorities.73

Concentration of Damages

According to FEMA regulations, highly concentrated damages "generally indicate a greater need for federal assistance than widespread and scattered damages throughout a state."74 The assumption that underlies this regulation is that the local support networks available to recover from an incident are increasingly undermined as more members of those local support networks become survivors of the incident.75 The dispersion of damage, however, is not necessarily an indication of total individual and household needs. Rural incidents, in particular, can be more difficult to assess because damages tend to be geographically less concentrated. As mentioned under the factors considered for PA, Congress has sought to address the challenges posed by rural incidents in receiving major disaster declarations and assistance packages.

Trauma

FEMA regulations cite three conditions that indicate a high degree of trauma to a community: (1) large numbers of injuries and deaths; (2) large-scale disruption of normal community functions and services; and (3) emergency needs such as extended or widespread loss of power or water.76

FEMA considers the trauma caused by injuries and loss of life in determining whether IA, or specific programs under IA, is warranted in an affected area. For IA-eligible medical and funeral expenses under Section 408 of the Stafford Act, this factor can carry some weight in making a determination.77

Large-scale disruption of normal community functions and emergency needs such as extended or widespread loss of power or water are also indicative of trauma and are considered when evaluating a governor's or chief executive's request. Assessing these indicators can be problematic because they are not currently defined in law or regulation. Consequently, discretionary judgments are significant aspects of the evaluation of IA needs for large-scale disruptions of normal community functions and extended or widespread emergency needs.

Special Populations

FEMA considers the unique needs of certain demographic groups within an affected area when evaluating an IA request. These "special populations" include low-income and elderly populations, and American Indian and Alaskan Native tribal populations. Although special populations are a distinct factor in the consideration of a governor's or chief executive's request, special populations may also contribute to the overall number of IA-eligible households in an affected area.

As with PA, FEMA considers whether state, local, or tribal governments "can meet the needs of disaster victims" prior to offering supplemental assistance through IA.78 Additionally for IA, FEMA considers the extent to which voluntary agency assistance can meet those needs.

Similar to insurance coverage of public and certain private, nonprofit facilities for PA, insurance coverage of private residences is an important consideration for IA. Per FEMA regulation, "by law, federal disaster assistance cannot duplicate insurance coverage."79 Therefore, the calculation of IA-eligible losses must deduct those losses covered by insurance.

FEMA assumes owner-occupied homes with a mortgage are insured against many natural disasters under their homeowner insurance policies. Under that assumption, FEMA uses census data to determine homeowner insurance penetration.80 Further, if the home is located in a flood-prone area then purchasing insurance for those disasters is often a legal requirement if the owner has a federally-backed mortgage. FEMA administers the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) which allows officials to more directly determine the status of flood insurance in communities and the number of policies in place in an affected area.

Average Amount of Individual Assistance by State

FEMA compares the total IA cost estimate from the Preliminary Damage Assessment (PDA) to the average amount of individual assistance by state. More specifically, regulations published in 1999 include a table of the average amount of IA per disaster, by state population, from July 1994 to July 1999 (reproduced as Table A-1). FEMA stresses that these averages are not to be used as thresholds but rather as a guide that "may prove useful to states and voluntary agencies as they develop plans and programs to meet the needs of disaster victims."81 It should be noted that some have questioned the relevance of this factor given the amounts have not been updated since 1999 and are based on 1990 census data.

|

Small States |

Medium States |

Large States |

|

|

Average Population (1990 census data) |

1,000,057 |

4,713,548 |

15,522,791 |

|

Number of Disaster Housing Applications Approved |

1,507 |

2,747 |

4,679 |

|

Number of Homes Estimated Major Damage/Destroyed |

173 |

582 |

801 |

|

Dollar Amount of Housing Assistance |

$2.8 million |

$4.6 million |

$9.5 million |

|

Number of Individual and Family Grant Applications Approved |

495 |

1,377 |

2,071 |

|

Dollar Amount of Individual and Family Grant Assistance |

$1.1 million |

$2.9 million |

$4.6 million |

|

Disaster Housing/IFG Combined Assistance |

$3.9 million |

$7.5 million |

$14.1 million |

|

Small Size States (under 2 million population, according to 1990 census data). Alaska, Delaware, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Nevada, North Dakota, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, West U.S. Virgin Islands and all Pacific Island dependencies, and Wyoming. |

|||

|

Medium Size States (2-10 million population, according to 1990 census data). Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, New Jersey, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Oregon, Puerto Rico, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin. |

|||

|

Large Size States (over 10 million population, according to 1990 census data). California, Florida, Illinois, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas. |

|||

Source: Table reproduced from 44 C.F.R. §206.48. Information is displayed as it appears in the Code of Federal Regulations.

Notes: The high 3 and low 3 disasters, based on Disaster Housing Applications, are not considered in the averages. Number of Damaged/Destroyed Homes is estimated based on the number of owner-occupants who qualify for Eligible Emergency Rental Resources. Data source is FEMA's National Processing Service Centers. Data are only available from July 1994 to July 1999. Given the congressional mandate in Section 320 of the Stafford Act which prohibits the use of formulas or sliding scales to determine declarations, the information in Table A-1 cannot be the basis of an arithmetic formula that solely determines whether IA is recommended.