Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

Changes from April 30, 2020 to March 23, 2023

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- Sales and Security Assistance/Cooperation Programs

- Security Assistance/Security Cooperation Programs

- Sales and Exports of U.S. Defense Articles in Statute, Administration Policy, and Regulation

- The Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 and the Arms Export Control Act of 1976

- National Security Presidential Memorandum Regarding U.S. Conventional Arms Transfer Policy: NSPM-10

- Title 22, Code of Federal Regulations, Foreign Relations

- DOD's Security Assistance Management Manual

- Sales and Exports of U.S. Defense Articles in International Agreements

- Missile Technology Control Regime

- The Wassenaar Arrangement

- Foreign Military Sales Process

- Letters of Request (LOR) Start the Process

- Letters of Offer and Acceptance (LOA) Set Terms

- Reports to Congress

- Case Executions Deliver Articles

- Customs Clearance

- Direct Commercial Sales Process

- DOS Role in DCS

- DOD Role in DCS

- Excess Defense Articles

- Interagency Relationships in Arms Sales

- State Department Policy Prerogatives

- DOD Policy and Implementation Role

- End-Use Monitoring (EUM)

- State Department's Blue Lantern Program (DCS)

- DOD's Golden Sentry Program (FMS)

- Enhanced EUM—Golden Sentry

- Questions for Congressional Consideration

- Do Current Levels of Arms Sales and Exports Fulfill Statutory and Policy Objectives?

- Are Current Methods of Conducting Sales of Defense Articles and Services Consistent with the Intent and Objectives of the AECA?

- Are End Use Monitoring Programs Resourced Adequately?

Figures

Tables

Summary

TheTransfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and

March 23, 2023

Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

Christina L. Arabia,

An extensive set of laws, regulations, policies, and procedures govern the sale and export of

Coordinator

sale and export of U.S.-origin weapons to foreign countries ("“defense articles and defense services," officially) are governed by an extensive set of laws, regulations, policies, and procedures. Congress has authorized such sales under two laws:

- ” officially). Analyst in Security Congress has authorized such sales under two laws: Assistance, Security Cooperation and the The Foreign Assistance Act (FAA) of 1961, 22 U.S.C. §2151, et seq.

- Global Arms Trade The Arms Export Control Act (AECA) of 1976, 22 U.S.C. §2751, et seq.

Nathan J. Lucas Section Research Manager

The FAA and AECA govern all transfers of U.S.-origin defense articles and services, whether

they are commercial sales, government-to-government sales, or security assistance/security cooperation grants (or building partnership capacity programs provided by U.S. military personnel). These measures can be provided by provided with U.S.-appropriated funds through security assistance/security cooperation programs. These transfers can occur under

Michael J. Vassalotti

Title 22 (Foreign Relations) or Title 10 (Armed Services) authorities. Arms sold or transferred

Section Research Manager

under these authorities are regulated by the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) and

the U.S. Munitions List (USML), which are located in Title 22, Parts 120-130 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR).

The two main methods for the sale and export of U.S.-made weapons under these authorities are the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) program and Direct Commercial Sales (DCS) licenses. Some other arms sales occur from current Department of Defense (DOD) stocks through Excess Defense Articles (EDA) provisions.

-

For FMS, the U.S. government procures defense articles as an intermediary for

foreigninternational partners'’ acquisition of defense articles and defense services, whichensures that the articles have the same benefits and protections that apply to the U.S. military's acquisition of its own articles and services. - allows partners to benefit from U.S. DOD technical and operational expertise, procurement infrastructure, and purchasing practices.

For DCS, registered U.S. firms may sell defense articles directly to

foreign partners though licenses and agreements received from the Department of State. Firms are still required to obtain State Department approval, and for major sales DOD review and congressional notification is requiredinternational partners. The U.S. government is not party to the arms agreement, but defense firms must still apply for an export license from the State Department. In some cases where U.S. firms have entered into international partnerships to produce some major weapons systems, comprehensive export regulations under 22 CFR 126.14 are intended to allow exports and technical data for those systems without having to go through the licensing process.

The State Department maintains responsibility for notifying Congress of proposed FMS cases and DCS export licenses, as required by the AECA.

Congress has amended the FAA and AECA to restrict arms sales to foreign entities for a variety of reasons. . These include restrictions on transfers to countries that violate human rights and states that support terrorism, as well as limitations on specific countries at certain times, such as any Middle East countries whose import of U.S. arms would adversely affect Israel'Israel’s qualitative military edge. Arms transfers to Taiwan are governed under the Taiwan Relations Act of 1979, P.L. 96-8, , 22 U.S.C. § 3301 et seq. Under the AECA, Congress can also overturn individual notified arms sales via a joint resolution. During the 116th116th Congress, such joint resolutions were introduced in opposition to planned arms sales to Saudi Arabia, but did not pass.

.

All U.S. defense articles and defense services sold, leased, or exported under the AECA are subject to end-use monitoring (to provide reasonable assurance that the recipient is complying with the requirements imposed by the U.S. government with respect to use, transfers, and security of the articles and services) to be conducted by the President (Section 40A of the AECA) to ensure compliance with U.S. arms export rules and policies. FMS transfers are monitored under DOD'’s Golden Sentry program and DCS transfers are monitored under the State Department'’s Blue Lantern program.

Introduction

The sale of U.S-origin armaments and other "defense articles1" has been a part of

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 10 link to page 11 link to page 12 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 17 link to page 18 link to page 19 link to page 19 link to page 21 link to page 22 link to page 23 link to page 24 link to page 24 link to page 25 link to page 26 link to page 26 link to page 27 link to page 27 link to page 28 link to page 28 link to page 28 link to page 28 link to page 29 link to page 29 link to page 15 link to page 21 Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

Contents

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1

Sales and Security Assistance/Cooperation Programs .............................................................. 2 Security Assistance/Security Cooperation Programs ................................................................ 3

Sales and Exports of U.S. Defense Articles in Statute, Administration Policy, and

Regulation .................................................................................................................................... 4

The Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 and the Arms Export Control Act of 1976 ................ 4 The Conventional Arms Transfer (CAT) Policy ................................................................. 6 Title 22, Code of Federal Regulations, Foreign Relations .................................................. 7 DOD’s Security Assistance Management Manual .............................................................. 8

Sales and Exports of U.S. Defense Articles in International Agreements ....................................... 9

Missile Technology Control Regime .................................................................................. 9 The Wassenaar Arrangement............................................................................................... 9

Foreign Military Sales Process ...................................................................................................... 10

Letters of Request (LOR) Start the Process ....................................................................... 11 Letters of Offer and Acceptance (LOA) Set Terms ........................................................... 12 Reports to Congress .......................................................................................................... 12 Case Executions Deliver Articles ...................................................................................... 13 Customs Clearance............................................................................................................ 14

Direct Commercial Sales Process .................................................................................................. 15

DOS Role in DCS ............................................................................................................. 15 DOD Role in DCS ............................................................................................................ 17

Excess Defense Articles ................................................................................................................ 18 Presidential Drawdown Authority ................................................................................................. 19 Interagency Relationships in Arms Sales ...................................................................................... 20

State Department Policy Prerogatives ..................................................................................... 20 DOD Policy and Implementation Role ................................................................................... 21

End-Use Monitoring (EUM) ......................................................................................................... 22

State Department’s Blue Lantern Program (DCS) .................................................................. 22 DOD’s Golden Sentry Program (FMS) ................................................................................... 23 Enhanced EUM—Golden Sentry ............................................................................................ 23

Select Questions Facing Congress ................................................................................................. 24

Are the Required Congressional Notifications and Reports Sufficient for

Congressional Oversight? .............................................................................................. 24

Are End Use Monitoring Programs Resourced Adequately? ............................................ 24 Are Current Methods of Conducting Sales of Defense Articles and Services

Consistent with the Intent and Objectives of the AECA? .............................................. 25

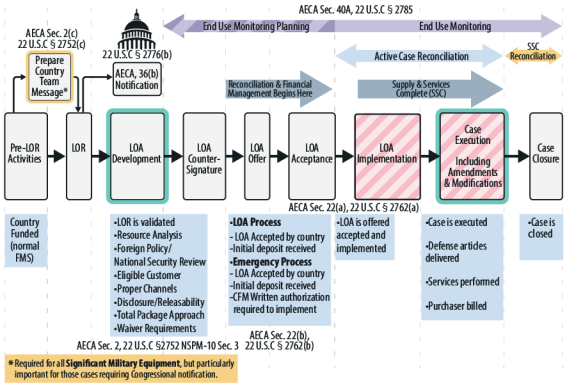

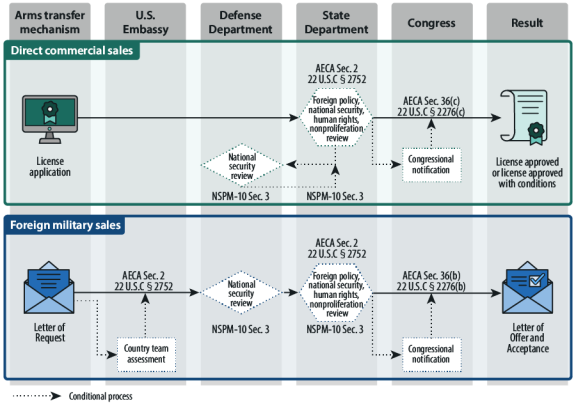

Figures Figure 1. Foreign Military Sales (FMS) Process ............................................................................ 11 Figure 2. Direct Commercial Sales (DCS) Licensing Process in Comparison with FMS ............. 17

Congressional Research Service

link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 30 link to page 32 Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

Tables Table 1. Foreign Military Sales (FMS) Totals, FY2018 to FY2022 ................................................ 3 Table 2. Value of Direct Commercial Sales (DCS) Licenses Issued, FY2018 to FY2022 .............. 3

Appendixes Appendix. Selected Legislative Restrictions on Sales and Export of U.S. Defense Articles ........ 26

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 28

Congressional Research Service

Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

Introduction The sale of U.S-origin armaments and other “defense articles1” to international partners has been a part of U.S. national security policy since at least the Lend-Lease programs in the lead-up to U.S. involvement in World War II.2 Historically, Presidents have used sales of defense articles and services to international partnersservices to foreign governments and organizations to further broad foreign policy goals, ranging from sales to countries that the U.S. government deemed to be strategically important countries during the Cold War, to buildingsales intended to help build global counterterrorism capacity following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

The sale of U.S. defense articles to foreign countries is governed by a broad set of statutes, public laws, federal regulations, and executive branch policies, along with international agreements. An interconnected body of legislative provisions, authorizations, and reporting requirements related to the transfer of U.S. defense articles appears in both the National Defense Authorization Acts (NDAA) and in the State Department, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) Appropriations Acts.23 These laws reflectspecify the roles thatof both the Department of State (DOS) and the Department of Defense (DOD) take in the administration of the sale, export, and funding of defense articles to foreign countries, which can be found in both Title 22 (Foreign Relations) and Title 10 (Armed Services) of the United States Code.

Congress enacted the current statutory framework for the sale and export of defense articles to other countries mainly through two laws—The Foreign Assistance Act of 1961(FAA), 22 U.S.C §2151, et seq., and the Arms Export Control Act of 1976 (AECA), 22 U.S.C. §2751, et seq.3 4 Among other provisions, the FAA established broad policy guidelines for the overall transfer of defense articles and services from the United States to foreign entities (foreign countries, firms, and/or individuals)international partners to include both sales and grant transfers, while the AECA also governs the sales of defense articles and services to those entities.

This report describes the major statutory provisions governing the sale and export of defense articles—Foreign Military Sales (FMS) and Direct Commercial Sales (DCS)—and outlines the process through which those sales and exports are made. FMS is the program through which the U.S. government, through interaction with purchasers, acts as a broker to procure defense articles for sales to eligible international partners.5 In DCS, the U.S. government does not act as a broker

1 “Defense Article” is defined by Section 644 of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, 22 U.S.C. §2403, as

(1) any weapon, weapons system, munition, aircraft, vessel, boat or other implement of war;

(2) any property, installation, commodity, material, equipment, supply, or goods used for the purposes of furnishing military assistance;

(3) any machinery, facility, tool, material supply, or other item necessary for the manufacture, production, processing repair, servicing, storage, construction, transportation, operation, or use of any article listed in this subsection; or

(4) any component or part of any article listed in this subsection; but shall not include merchant vessels or, as defined by the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, as amended (42 U.S.C. §2011), source material (except uranium depleted in the isotope 235 which is incorporated in defense articles solely to take advantage of high density or pyrophoric characteristics unrelated to radioactivity), by-product material, special nuclear material, production facilities, utilization facilities, or atomic weapons or articles involving Restricted Data.

2 International partners refers broadly to U.S. allied and partner foreign governments as well as international organizations, such as NATO.

3 See CRS Report R44602, DOD Security Cooperation: An Overview of Authorities and Issues, by Bolko J. Skorupski and Nina M. Serafino.

4 The AECA superseded the Foreign Military Sales Act of 1968, P.L. 90-629. 5 For information on criteria for FMS eligibility, see Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA), Security

Congressional Research Service

1

link to page 30 link to page 7 link to page 7 Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

for sales to certain foreign countries and organizations, also called eligible purchasers. In DCS, the U.S. government does not act as a broker for the sale, but still must license it, unless export of the item is exempt from licensing according to regulations in the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), contained in Subchapter M, 22 CFR 120-130, described below. The President designates what items are deemed to be defense articles or defense services, and thus subject to DCS licensing, via the U.S. Munitions List (USML). All persons (other than U.S. government personnel performing official duties) engaging in manufacturing, acting as a broker, exporting, or importing defense articles and services must register with the State Department according to ITAR procedures.4

6 The State Department is required under the AECA to notify Congress 15 to 30 days prior to all planned FMS and DCS cases over a certain value threshold. Congress can, pursuant to the AECA, hold or restrict such sales via a joint resolution.

The report also provides a select list of specific legislative limitations on arms sales and end use monitoring requirements found in the Arms Export Control Act. Future updates will consider policy implications and issues for Congress.

Since the enactment of the FAA in 1961, Congress has amended both the FAA and the AECA, as well as Title 10 U.S.C. in order to limit the sale and export of U.S. defense articles to certain international partners. Congress has successfully included provisions in annual authorization and appropriations bills that have directed executive action regarding the sale and transfer of U.S.-origin defense articles. For example, through such provisions Congress has required the executive to prioritize certain regions or countries when making decisions about arms sales, sought to restrict sales based on human rights or other considerations, mandated additional reporting requirements on arms sales, and determined the amount of Foreign Military Financing intended to be made available to certain countries for purchasing U.S. arms (see the Appendix for examples of legislation aimed to increase or preserve congressional oversight of the U.S. arms sales process).

Sales and Security Assistance/Cooperation Programs In FY2022, the latest year for which Sales and Security Assistance/Cooperation Programs

In FY2018, the latest year complete agency data is available, the value of authorized U.S. arms sales to foreign governments and export licenses issued totaled about $184.3197 billion. Foreign entities purchased $47.7143.07 billion in FMS cases and the value of privately contracted DCS authorizations licensed by the State Department (distinct from actual deliveries of licensed articles and services) totaled $136.6153.7 billion (Table 1 andand Table 2).7

Assistance Management Manual (SAMM), C4.1. - Who May Purchase Using the FMS Program.

6 Manufacturers must register, even if they are not currently exporting defense items. 7 Defense Security Cooperation Agency, “FY22 Security Cooperation Figures Announcement,” January 25, 2023; “Fiscal Year 2021 Security Cooperation Figures,” December 22, 2021; “FY2020 Security Cooperation Numbers,” December 4, 2020; “Fiscal Year 2019 Arms Sales Total of $55.4 Billion Shows Continued Strong Sales,” October 15, 2019; “Fiscal Year 2018 Sales Total $55.56 Billion,” October 9, 2018. State Department, “Fiscal Year 2022 U.S. Arms Transfers and Defense Trade,” January 25, 2023; “Fiscal Year 2021 U.S. Arms Transfers and Defense Trade,” December 22, 2021; “U.S. Arms Transfers Increased by 2.8 Percent in FY 2020 to $175.08 Billion,” January 20, 2021; “U.S. Arms Transfers Rise 13 Percent in 2018, Highlighting Administration’s Success Strengthening Security Partners While Growing American Jobs,” May 21, 2019. See also, Defense Department, “DOS and DOD Officials Brief Reporters on Fiscal 2020 Arms Transfer Figures,” December 4, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

2

Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

Table 1. Foreign Military Sales (FMS) Totals, FY2018 to FY2022

U.S.-Funded

U.S.-Funded

Partner-Nation

Title 22

Title 10

Fiscal Year

Funded

Authorizations

Authorizations

Total

FY2022

$43.07 bil ion

$6.65 bil ion

$2.21 bil ion

$51.92 bil ion

FY2021

$28.67 bil ion

$3.80 bil ion

$2.34 bil ion

$34.81 bil ion

FY2020

$44.79 bil ion

$3.30 bil ion

$2.69 bil ion

$50.78 bil ion

FY2019

$48.25 bil ion

$3.67 bil ion

$3.47 bil ion

$55.4 bil ion

FY2018

$47.71 bil ion

$3.52 bil ion

$4.42 bil ion

$55.66 bil ion

Source: Defense Security Cooperation Agency; “FY22 Security Cooperation Figures Announcement,” January 25, 2023; “Fiscal Year 2021 Security Cooperation Figures,” December 22, 2021; “FY2020 Security Cooperation Numbers,” December 4, 2020; “Fiscal Year 2019 Arms Sales Total of $55.4 Bil ion Shows Continued Strong Sales,” October 15, 2019; “Fiscal Year 2018 Sales Total $55.56 Bil ion,” October 9, 2018.

Table 2. Value of Direct Commercial Sales (DCS) Licenses Issued,

FY2018 to FY2022

Fiscal Year

Value of DCS Licenses

FY2022

$153.7 bil ion

FY2021

$103.4 bil ion

FY2020

$124.3 bil ion

FY2019

$114.7 bil ion

FY2018

$136.6 bil ion

Source: U.S. State Department; “Fiscal Year 2022 U.S. Arms Transfers and Defense Trade,” January 25, 2023; “Fiscal Year 2021 U.S. Arms Transfers and Defense Trade,” December 22, 2021; “U.S. Arms Transfers Increased by 2.8 Percent in FY 2020 to $175.08 Bil ion,” January 20, 2021; “U.S. Arms Transfers Rise 13 Percent in 2018, Highlighting Administration’s Success Strengthening Security Partners While Growing American Jobs,” May 21, 2019.

Security Assistance/Security Cooperation Programs Table 2).5 That same year, the State Department requested $7.09 billion (base and OCO) for all of its Title 22 security assistance authorities in its International Security Assistance account, while DOD executed $4.42 billion for Title 10 security cooperation authorities,6 totaling $11.51 billion, or 24.1% of what foreign entities spent on FMS and 8.4% of the amount of DCS approved licenses.

|

Fiscal Year |

Partner Nation Funded |

|

|

Total |

|

FY2018 |

$47.71 billion |

$3.52 billion |

$4.42 billion |

$55.66 billion |

|

FY2017 |

$32.02 billion |

$6.04 billion |

$3.87 billion |

$41.93 billion |

|

FY2016 |

$25.7 billion |

$2.9 billion |

$5.0 billion |

$33.6 billion |

Source: Defense Security Cooperation Agency, see footnote 5.

|

Fiscal Year |

Value of DCS Licenses |

|

FY2018 |

$136.6 billion |

|

FY2017 |

$128.1 billion |

|

FY2016 |

$117.9 billion |

Source: U.S. State Department, see footnote 5.

Security Assistance/Security Cooperation Programs

While most arms sales and exports are paid for by the recipient government or entity, transfers funded by U.S. security assistance or security cooperation grants to foreign security forces comprise a relatively small portion of arms exports, but they are beyond the scope of this report. These transfers are generally considered foreign assistance, and are authorized pursuant to the FAA, annual National Defense Authorization Acts, and other authorities codified in Title 22 and Title 10 of the U.S. Code. With the exception of Title 10 authorities, the FAA and AECA also govern all of the transfers of U.S.-origin defense articles and services, whether they are commercial sales, government-to-government sales, or security assistance/security cooperation.

Major Title 22 grant-based security assistance authorities pertaining to defense articles are

- Foreign Military Financing (FMF),

- Nonproliferation, Anti-Terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs (NADR),

-

Congressional Research Service

3

Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

Peacekeeping Operations (PKO).

7

8 Major Title 10 grant-based security cooperation authorities are

-

§333: Authority to Build the Capacity of Foreign Security Forces

("333 authority"), - Defense Institution Reform Initiative (DIRI),

- Ministry of Defense Advisors (MDOA) program, and

- Southeast Asia Maritime Security Initiative (MSI).8

DOD, , §331: Support to Conduct of Operations, §321: Training with Friendly Foreign Countries.9

DOD, primarily through its Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA), executes most security assistance and security cooperation programs. FMF, IMET, EDA, and equipment lease cases involving the transfer of U.S.-origin arms are treated as FMS cases and reported as such by DSCA. Cases executed pursuant to Title 10 authorities are also treated as FMS cases, but are referred to by practitioners as "“pseudo-FMS"” cases because they often involve a focus on training of foreign forces as well as on the transfer of arms.

Sales and Exports of U.S. Defense Articles in Statute, Administration Policy, and Regulation

The broad set of statutes, public laws, federal regulations, executive branch policies, and international agreements governing the sale of U.S. defense articles to foreign countries include the following.

international partners include the following. The Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 and the Arms Export Control Act of 1976

As noted above, the primary statutes covering the sale and export of U.S. defense articles to foreign countriesinternational partners are the FAA (P.L. 87-195, as amended) and AECA (P.L. 90-629, as amended). . The FAA expresses, as U.S. policy, that

the efforts of the United States and other friendly countries to promote peace and security continue to require measures of support based upon the principle of effective self-help and mutual aid, [and that its purpose is] to authorize measures in the common defense against internal and external aggression, including the furnishing of military assistance, upon internal and external aggression, including the furnishing of military assistance, upon request, to friendly countries and international organizations.9

10 The AECA states that

it is the sense of Congress that all such sales be approved only when they are consistent with the foreign policy of the United States, the purposes of the foreign assistance program of the United States as embodied in the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended, the extent and character of the military requirement and the economic and financial capability of the recipient country, with particular regard being given, where appropriate, to proper

8 “Major” authorities are those with their own budget line in the Department of State, FY2023 Congressional Budget Justification—Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs, accessed June 8, 2022. International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) and International Military Education and Training (IMET) security assistance programs do not transfer military arms. See also CRS Report R44602, DOD Security Cooperation: An Overview of Authorities and Issues, by Bolko J. Skorupski and Nina M. Serafino.

9 “Major” authorities are those with their own budget line in the Office of the Secretary of Defense Security Cooperation Budget, Fiscal Year (FY) 2023 President’s Budget: Justification for Security Cooperation Program and Activity Funding, April 2022, accessed June 6, 2022. Since FY2021, the Defense Security Cooperation Agency has used the International Security Cooperation Programs (ISCP) Account to fund activities under 10 U.S.C. §332, §333, and P.L. 114-92 Section 1263 (Indo-Pacific Maritime Security Initiative).

10 22 U.S.C. §2301.

Congressional Research Service

4

Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

of the recipient country, with particular regard being given, where appropriate, to proper balance among such sales, grant military assistance, and economic assistance as well as to the impact of the sales on programs of social and economic development and on existing or incipient arms races.10

11

The FAA also establishes the U.S. policy for how recipient countriesinternational partners are to utilize defense articles sold or otherwise transferred. Section 502 states that

defense articles and defense services to any country shall be furnished solely for internal security (including for antiterrorism and nonproliferation purposes), for legitimate self-security (including for antiterrorism and nonproliferation purposes), for legitimate self-defense, to permit the recipient country to participate in regional or collective arrangements or measures consistent with the Charter of the United Nations, or otherwise to permit the recipient country to participate in collective measures requested by the United Nations for the purpose of assisting foreign military forces in less developed friendly countries (or the voluntary efforts of personnel of the Armed Forces of the United States in such countries) to construct public works or to engage in other activities helpful to the economic and social development of such friendly countries.11

12

Section 22 of the AECA, provides the statutory basis for the U.S. Foreign Military Sales program and allows the U.S. government to interact with the purchaser as a broker to procure defense articles for sales to certain foreign countries and organizations, also called eligible purchasers. Under this provision, the U.S. government may procure defense articles and services for sale to an international partner if the partner indicates a firm commitment, also referred to as a “dependable undertaking,” to pay the full amount of aUnder this provision, the President may, without requirement for charge to any appropriation or contract authorization, enter into contracts to sell defense articles or defense services to a foreign country or international organization if it provides the U.S. government with a dependable undertaking to pay the full amount of the contract.12

contract.13 The Taiwan Relations Act of 1979

An exception to the general arms transfer framework is Taiwan, to which the sale of defense articles and defense services are not subject to the FAA or AECA. Rather, the applicable statute governing FMS-like and DCS-like transfers to Taiwan is the Taiwan Relations Act of 1979, P.L. 96-8, 22 U.S.C. § ”14 In addition, the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act, P.L. 115-91, Section 1259A, requires congressional notification of all requests for transfers of defense articles or defense services to Taiwan no later than 120 days after the Secretary of Defense receives a Letter of Request. The act also states that the sense of Congress is |

”

Section 38 of the AECA furthermore provides the statutory basis for the U.S. Direct Commercial Sales of defense articles and services. Under this provision, the U.S. government does not act as a broker for the sale, but still must license it, unless specifically provided for in regulations in the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), contained in Subchapter M, 22 CFR 120-130, described below. The President designates what items are deemed to be defense articles or defense services, and thus subject to DCS licensing, via the U.S. Munitions List. All (USML). All

11 22 U.S.C. §2751. 12 22 U.S.C. §2302. 13 22 U.S.C. §2762(a). See also, Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA), Security Assistance Management Manual (SAMM), C9.8.3. Dependable Undertaking Status.

14 P.L. 96-8, §3, 22 U.S.C. §3302 (a) and (b).

Congressional Research Service

5

Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

persons (other than U.S. government personnel performing official duties) engaging in manufacturing, acting as a broker, exporting, or importing defense articles and services must register with the State Department according to ITAR procedures.14 15 The provision also requires the President to review the items on the USML and to notify the House Foreign Affairs Committee, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and the Senate Banking Committee if any items no longer warrant export controls, pursuant to the ITAR.

Title 10 United States Code, Armed Forces

U.S.-origin defense articles sold to foreign entities may be used by the recipient country fol owing: (1) Counterterrorism operations. (2) Counter-weapons of mass destruction operations. (3) Counter- (4) Counter-transnational organized crime operations. (5) Maritime and border security operations. (6) Military intelligence operations.

|

National Security Presidential Memorandum Regarding U.S. Conventional Arms Transfer Policy: NSPM-10

In April 2018, the Trump Administration, citing the AECA, issued a National Security Presidential Memorandum, NSPM-10, outlining its policy concerning the transfer of conventional arms. The memorandum reflects many of the policy statements of the FAA and AECA in aiming to "bolster the security of the United States and our allies and partners," while preventing proliferation by exercising restraint and continuing to participate in multilateral nonproliferation arrangements such as the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) and Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies. It explicitly commits the U.S. government to continue to meet the requirements of all applicable statues, including the AECA, the FAA, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, and the annual NDAAs. NSPM-10 also prioritizes efforts to "increase trade opportunities for United States companies, including by supporting United States industry with appropriate advocacy and trade promotion activities and by simplifying the United States regulatory environment."17

In addition, NSPM-10 directs the executive branch to consider the following in making arms transfer decisions:

- the national security of the United States, including the transfer's effect on the technological advantage of the United States;

- the economic security of the United States and innovation;

- relationships with allies and partners;

- human rights and international humanitarian law; and

- nonproliferation implications.18

Title 22, Code of Federal Regulations, Foreign Relations

The AECA, Section 38, also authorizes the President to issue regulations on the import and export of defense articles. As noted above, the catalog of defense articles subject to these regulations is called the United States Munitions List. The USML is found in federal regulations at 22 CFR 121. The series of federal regulations for importing and exporting of defense articles—the International Traffic in Arms Regulations—is contained in Subchapter M, 22 CFR 120-130. The USML lists defense articles by category and identifies which of those articles are "significant military equipment" further restricted by provisions in the AECA.19

The President has delegated authority for administering the USML and associated regulations to the Secretary of State, who in turn has delegated this authority to the Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Defense Trade Controls in the Bureau of Political-Military Affairs (PM).20 The Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC) is responsible for ensuring that commercial exports of defense articles and defense services advance U.S. national security objectives. DDTC also administers a public web portal for U.S. firms seeking assistance with exporting defense articles and services.21

Global Comprehensive Export Authorizations: The F-35 In cases where U.S. defense manufacturers are involved in international partnerships with NATO countries, Australia, Japan, and/or Sweden for major defense article programs, 22 CFR 126.14 allows DDTC to provide a comprehensive An example is the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, manufactured though a partnership between the United States and eight partner countries (as well as through FMS agreements with three other countries). The global comprehensive export authorization for the F-35 allows approved U.S. manufacturers to export items or technical data involved in the research and development, testing and evaluation, and procurement of the system to firms in partner countries without going through the formal DDTC licensing process.24 The Global Project Authorization is one of three special comprehensive export authorizations allowed in 22 CFR 126.14. The other two, Major Project Authorization and Major Program Authorization, are based on the principal registered U.S. exporter/prime contractor or a single registered U.S. exporter that identifies a large-scale cooperative project or program with a NATO member, Australia, Japan, or Sweden. |

Title 22, Code of Federal Regulations, Foreign Relations

The AECA, Section 38, also authorizes the President to issue regulations on the import and export of defense articles. As noted above, the catalog of defense articles subject to these regulations is

21 Department of State, Directorate of Defense Trade Controls News & Events, “U.S. Conventional Arms Transfer Policy,” February 23, 2023.

22 As compared with prior CAT policies, the Biden Administration’s policy appears to strengthen restrictions on arms sales that could contribute to serious violations of international humanitarian or human rights law. The policy in part provides that “no arms transfer will be authorized where the United States assesses that it is more likely than not” that the arms will be used in connection with genocide, crimes against humanity, grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949, or other serious violations of international humanitarian or human rights law.

23 The White House, “Memorandum on United States Conventional Arms Transfer Policy,” February 23, 2023. 24 Government Accountability Office, Joint Strike Fighter: Management of the Technology Transfer Process, GAO-06-364, March 2006.

Congressional Research Service

7

Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

called the United States Munitions List (USML). The USML is found in federal regulations at 22 CFR 121. The series of federal regulations for importing and exporting of defense articles—the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR)—is contained in Subchapter M, 22 CFR 120-130. The USML lists defense articles by category and identifies which of those articles are “significant military equipment” further restricted by provisions in the AECA.25

The President has delegated authority for administering the USML and associated regulations to the Secretary of State, who in turn has delegated this authority to the Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Defense Trade Controls in the Political-Military Affairs (PM) Bureau of the Department of State, which reports to the Under Secretary of State for International Security and Arms Control.26 The Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC) is responsible for ensuring that commercial exports of defense articles and defense services advance U.S. national security objectives. DDTC also administers a public web portal for U.S. firms seeking assistance with exporting defense articles and services.27

Canadian Exemptions in Federal Regulations

In some cases, Canadian purchasers are exempt from export license requirements for defense articles and services. According to 22 CFR 126.5, ”28 Canadian purchasers must |

DOD'’s Security Assistance Management Manual

The Department of Defense has a substantial role in the sale of defense articles to foreign countries through FMS, which DOD administers in coordination with the Department of State mainly through the Defense Security Cooperation Agency. DSCA provides procedures for FMS and certain other transfers of defense articles and defense services to foreign entities in its Security Assistance Management Manual (SAMM). The SAMM is used mainly by the military services, the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Special Operations Command (SOCOM), the regional combatant commanders, and country teams in U.S. embassies overseas, and it may also be consulted by foreign countries and U.S. defense contractors. The SAMM also provides the timelines and methods for coordinating FMS, cases with the State Department.24

Sales and Exports of U.S. Defense Articles in International Agreements25

The United States participates in two international agreements that broadly affect the transfer of U.S. defense articles: The Missile Technology Control Regime and the Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies. Other international agreements, such as the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), the Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material, the Chemical Weapons Convention, and the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention, may limit exports of defense-related material, but only material linked to the development of nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons.26

Missile Technology Control Regime

The Missile Technology Control Regime, while not a treaty, is an informal and voluntary association of countries seeking to reduce the number of systems capable of delivering weapons of mass destruction (other than manned aircraft), and seeking to coordinate national export licensing efforts aimed at preventing their proliferation. The MTCR was originally established in 1987 by Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States. Since then, participation has grown to 35 countries.27

Member nations, by consensus, agree on common export guidelines (the MCTR Guidelines) on transfer of systems capable of delivering weapons of mass destruction, as well as an integral common list of controlled items (the MTCR Equipment, Software and Technology Annex). The annex is a list of controlled items – both military and dual-use – including virtually all key equipment, materials, software, and technology needed for the development, production, and operation of systems capable of delivering nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons. The annex is divided into "Category I" and "Category II" items.28 Partner countries exercise restraint when considering transfers of items contained in the annex, and such transfers are considered by each partner country on a case-by-case basis.29

The State Department, Directorate of Defense Trade Controls,

The Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA), on behalf of the Secretary of Defense and the Undersecretary of Defense for Policy, is responsible for directing, administering, and implementing many security assistance/security cooperation and arms transfer programs, as well as developing policy, procedures, and DOD-wide guidance on such programs. DSCA issues and regularly updates the Security Assistance Management Manual (SAMM), which includes policy and guidance for the administration and implementation of security assistance and arms transfer programs in compliance with the FAA, AECA, and other related statutes and directives.29 DSCA

25 22 C.F.R. §121. 26 22 C.F.R. §120.1. 27 U.S. Department of State, “Directorate of Defense Trade Controls.” 28 22 CFR §126.5, Canadian Exemptions. 29 Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA), “Security Assistance Management Manual (SAMM),” available at http://www.samm.dsca.mil/. The procedures found in the SAMM apply to sales and exports of defense articles, as well as to the defense articles provided as grant assistance to foreign countries. When DOD is involved in the transfer of defense articles or services funded by appropriations under either DOD (Title 10) or DOS (Title 22) authorities, DSCA manages the transfer through the same infrastructure as it does for Foreign Military Sales (FMS) cases, and reports the transfers in its yearly total of sales of defense articles and services.

Congressional Research Service

8

Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

regularly posts policy memoranda to denote policy changes that have been incorporated into the SAMM or include additional policy or implementation guidance.30

Sales and Exports of U.S. Defense Articles in International Agreements31 The United States participates in two international agreements that affect the transfer of U.S. defense articles: the Missile Technology Control Regime and the Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies.32

Missile Technology Control Regime

The Missile Technology Control Regime is a 35-member voluntary export control regime whose participating governments adhere to common export policy guidelines applied to lists of controlled items. The MTCR guidelines call on each partner country to exercise restraint when considering transfers of equipment or technology, as well as “intangible” transfers, that would provide, or help a recipient country build, a missile capable of delivering a 500 kilogram warhead to a range of 300 kilometers or more. 33 The MTCR annex contains two categories of controlled items. Category I items are the most sensitive. There is “a strong presumption to deny” such transfers, according to the MTCR guidelines. Regime partners have greater flexibility with respect to exports of Category II items. The State Department’s Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC) administers the U.S. implementation of the MTCR and incorporates the MTCR guidelines and annex into the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) and the U.S. Munitions List (USML).34

The Wassenaar Arrangement

The 42-memberMunitions List.30

The Wassenaar Arrangement

In 1996, 33 countries, including the United States, agreed to the Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies. The arrangement aims " aims “to contribute to regional and international security and stability, by promoting transparency and greater responsibility in transfers of conventional arms and dual-use goods and technologies, thus preventing destabilising accumulations."31 It maintains”35 The participating governments maintain two control lists. One is aThe first list ofcontains weapons, including small arms, tanks, aircraft, and unmanned aerial systems. The second is a list ofincludes dual-use technologies including material processing, electronics, computers, information security, and navigation/avionics. Dual-use, in this context, means items and technologies that can be used in both civilian and military applications.

DDTC incorporates the Wassennar Arrangement into the ITAR and USML.32 Under the Export Control Act of 2018 (Subtitle B, Part 1, P.L. 115-232), the Department of Commerce is to "establish and maintain a list" of controlled items, foreign persons, and end-uses determined to be a threat to U.S. national security and foreign policy. The legislation also directs the Commerce Department to require export licenses; "prohibit unauthorized exports, re-exports, and in-country transfers of controlled items"; and "monitor shipments and other means of transfer."33

30 DSCA, “DSCA’s Policy Memoranda,” available at https://samm.dsca.mil/policy-memoranda-listing/policy-memoranda.

31 This section was authored by CRS Specialist in Nonproliferation Paul K. Kerr. In addition to the agreements discussed in this section, the United Nations Register of Conventional Arms and the Arms Trade Treaty have implications for U.S. policy regarding arms sales. They are, however, beyond the scope of this report, as they are not specifically mentioned in NSPM-10.

32 For a detailed discussion of the MTCR and agreements limiting the export of materials related to nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons, see CRS Report RL31559, Proliferation Control Regimes: Background and Status, coordinated by Mary Beth D. Nikitin.

33 The Missile Technology Control Regime, Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) Equipment, Software, and Technology Annex, October 12, 2019.

34 Department of State, “The International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR).” The AECA mandates inclusion of the MCTR Annex on the USML.

35 The Wassenaar Arrangement, “About Us,” https://www.wassenaar.org/about-us/.

Congressional Research Service

9

Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

navigation/avionics. Dual-use goods are commodities, software, or technologies that have both civilian and military applications. DDTC incorporates the Wassenaar Arrangement into the ITAR and USML.36 The Department of Commerce implements controls on the export of dual-use items.

Foreign Military Sales Process Foreign Military Sales Process

The FMS program is the U.S. government-brokered method for delivering U.S. arms to eligible foreign purchasers, normally friendly nations, partner countries, and allies.34allies and partner nations.37 The program is authorized through the AECA, with related authorities delegated by the President, under Executive Order 13637, to the Secretaries of State, Defense, and Commerce.

The State Department (DOS)

DOS is responsible for the export (and temporary import) of defense articles and services governed by the AECA, and reviews and submits to Congress an annual Congressional Budget Justification (CBJ) for security assistance. This also includes an annual estimate of the total amount of sales and licensed commercial exports expected to be made to each foreign nation as required by 22 U.S.C §2765(a)(2)).35

38

DOD generally implements the FMS program as a military-to-military program and serves as intermediary for foreign partners'’ acquisition of U.S. defense articles and services. Using what is commonly called the Total Package Approach, U.S. security assistance organizations must offer, in addition to specific defense articles, a sustainment package to help the buyer maintain and operate the article(s) effectively and in accordDOD uses what it refers to as a Total Package Approach (TPA) to help ensure that FMS customers can operate and maintain their purchased items in the future and in a manner consistent with U.S. intent.3639 DOD follows the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS), except where deviations are authorized.3740 Acquisition on behalf of eligible FMS purchasers must be in accordance with DOD regulations and other applicable U.S. government procedures. This arrangement affords the foreign purchaser the same benefits and protections that apply to DOD procurement, and it is one of the principal reasons why foreign governments and international organizations might choose to procure defense articles through FMS. FMS requirements may be consolidated with U.S. requirements or placed on separate contracts, whichever is more expedient and cost-effective.38

Purchasers must agree to pay in U.S. dollars, by converting their own national currency or, under limited circumstances, though reciprocal arrangements.3943 When the purchase cannot be financed by other means, credit financing or credit guarantees can be extended if allowed by U.S. law. FMS cases can also be directly funded by DOS using Foreign Military Financing appropriations.40

44 Letters of Request (LOR) Start the Process

When an eligible foreign purchaser (government or otherwise) decides to purchase or otherwise obtain a U.S. defense article or service, it begins the process by making the official request in the form of a letter of request (LOR) (See Figure 1 for an illustration of the process from receipt to case closure.) The letter may take nearly any form, from a handwritten request to a formal letter, but it must be in writing. The purchaser submits the LOR to a U.S. security cooperation organization (SCO),4145 normally an Office of Defense Cooperation (ODC) nested within the U.S.

43 DSCA, SAMM, C9.3.2. Payment in U.S. Dollars. See also, 22 U.S.C. §2761 and 22 U.S.C. §2762. 44 DSCA, SAMM, C9.7. Methods of Financing. 45 DSCA, SAMM, Glossary, Security Cooperation Organization. SCO is a generic term for those DOD organizations permanently located in a foreign country and assigned responsibilities for carrying out security cooperation management functions under Title 22 U.S.C. §2321i. The actual names given to such DOD components may include military assistance advisory groups, military missions and groups, offices of defense or military cooperation, and liaison groups. The term SCO does not include units, formations, or other ad hoc organizations that conduct security cooperation activities such as mobile training teams, mobile education teams, or operational units conducting security

Congressional Research Service

11

Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

Embassy in the country, or directly to DSCA or an implementing agency (IA).46nested within the U.S. Embassy in the country, or directly to DSCA or an implementing agency (IA). The IA is usually a military department or DOD agency (e.g., Army Security Assistance Command, Navy International Programs Office, Air Force International Affairs). The LOR can be submitted in-country or through the country'’s military and diplomatic personnel stationed in the United States.

DOD policy guidance states thatUnited States. Unless an item has been designated as "FMS Only," DOD is generally neutral as to whether a country an international partner purchases U.S.-origin defense articles/services through FMS or DCS (discussed below).42.47 The AECA gives the President discretion to designate which military end-itemsdefense articles must be sold exclusively through FMS channels.4348 This discretion is delegated to the Secretary of State under Executive Order 13637 and, as a matter of policy, this discretion is generally exercised upon the recommendation of DOD.

. As such, DOS maintains responsibility for reviewing whether a sale should be “FMS Only.” DOD, through the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA), can provide recommendations and rationales to DOS for adding or removing the “FMS Only” designation.49

Once the U.S. SCO receives the LOR, it transmits the request to the relevant agencies (e.g., DSCA, IA) for consideration and export licensing. U.S. government responses to LORs include price and availability (P&A) data, letters of offer and acceptance (LOAs), and other appropriate actions that respond to purchasers'’ requests. If the IA recommends disapproval, it notifies DSCA, which coordinates the disapproval with DOS, as required, and formally notifies the customer of the disapproval.44

50 Letters of Offer and Acceptance (LOA) Set Terms

After approving the transfer of a defense article, the United States responds with a letter of offer and acceptance (LOA). The LOA is the legal instrument used by the USG to sell defense articles, defense services including training, and design and construction services to an eligible purchaser. The LOA itemizes the defense articles and services offered and when implemented becomes an official tender by the USG. Signed LOAs and their subsequent amendments and modifications are also referred to as "“FMS cases."” The time required to prepare LOAs varies with the complexity of the sale.45

51

Reports to Congress

Congress52

Within 60 days after the end of a quarter, the State Department, on behalf of the President, sendsis required by law to send to the Speaker of the House, HFAC, and the chairmanchair of the SFRC a report of, inter alia,

- LOAs offering major defense equipment valued at $1 million or more;

- all LOAs accepted and the total value;

- the dollar amount of all credit agreements with each eligible purchaser; and

- all licenses and approvals for exports sold for $1 million or more.

46

Congressional Notification Requirements for FMS47 53

cooperation activities.

46 For a list of IAs, see DSCA, SAMM, Table C5.T2. IAs Authorized to Receive Letters of Request. 47 DSCA, SAMM, C4.3.4. Neutrality. For a list of “FMS Only” items, see DSCA, SAMM, C4.3.5.2. 48 The U.S. Munitions List is prescribed in 22 U.S.C. §2778(a)(1). 49 DSCA, SAMM, C4.3.5. FMS-Only Determinations. For a list of criteria used by DOS to determine “FMS Only” designations, see DSCA, SAMM, C4.3.5.3.

50 DSCA, SAMM, C5.2.2. Negative Responses to LORs. 51 DSCA, SAMM, C5.4.2. LOA Document Preparation Timeframe. 52 For a list of required reports, see DOD, SAMM, A5.1. - DSCA Reporting Requirements (Congressional). 53 22 U.S.C. §2776 .

Congressional Research Service

12

Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

Congressional Notification Requirements for FMS54

The AECA, Section 36(b) (22 U.S.C. §2776(b)), requires State Department reporting to Congress as

Section 36(b)(5)(a) of the AECA contains a reporting requirement for defense articles or equipment items whose technology or capability has, prior to delivery, been Section 36(i) of the AECA also requires the President to notify the Foreign Relations/Foreign Affairs Committees 30 calendar days prior to the shipment of FMS items requiring Congressional notification under Section 36(b) if the chairman or ranking member of either committee request such notification. Congress reviews formal notifications pursuant to procedures in the AECA and has the authority to block a sale. |

Case Executions Deliver Articles

The IA takes action to implement a case once the purchaser has signed the LOA and necessary documentation and provided any required initial deposit. The standard types of FMS cases are defined order, blanket order, and cooperative logistics supply support arrangement (CLSSA). A CLSSA usually accompanies sales of major defense articles, providing an arrangement for supplying repair parts and other services over a specified period after delivery of the articles.48 55 Defined order cases or lines are commonly used for the sale of items that require item-by-item security control throughout the sales process or that require separate reporting; blanket order cases or lines are used to provide categories of items or services (normally to support one or more end items) with no definitive listing of items or quantities. Defined order and blanket order cases are routinely used to provide hardware or services to support commercial end items, obsolete end items (including end items that have undergone system support buyouts), and selected non-U.S. origin military equipment.4956 The case must be implemented in all applicable data systems (e.g., Defense Security Assistance Management System [DSAMS], Defense Integrated Financial System [DIFS], DSCA 1200 System, and Military Department [MILDEP] systems) before case execution occurs. The IA issues implementing instructions to activities that are involved in executing the FMS case.50

57

Case execution is the longest phase of the FMS case life cycle. Case execution includes acquisition, logistics, transportation, maintenance, training, financial management, oversight, coordination, documentation, case amendment or modification, case reconciliation, and case reporting. Case managers, normally assigned to the IAs, track FMS delivery status in

54 CRS Report RL31675, Arms Sales: Congressional Review Process, by Paul K. Kerr. 55 DSCA, SAMM, C5.4.3.3. Cooperative Logistics Supply Support Arrangements (CLSSAs). 56 DSCA, SAMM, C5.4.3. Types of FMS Cases. For Taiwan case documents, all milestones are entered in DSAMS and the IA is responsible for transferring signature dates and information onto the cover memorandum to the American Institute in Taiwan.

57 DSCA, SAMM, C6.1.1. Routine Case Implementation.

Congressional Research Service

13

Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

coordination with SCOs.58coordination with SCOs.51 FMS records, such as case directives, production or repair schedules, international logistics supply delivery plans, requisitions, shipping documents, bills of lading, contract documents, billing and accounting documents, and work sheets, are normally unclassified. All case transactions, financial and logistical, must be recorded as part of the official case file. Cost statements and large accounting spreadsheets must be supported by source documents.52

59

LOA requirements are fulfilled through existing U.S. military logistics systems. With the exception of excess defense articles (EDA) or obsolete equipment, items are furnished only when DOD plans to ensure logistics support for the expected item service life. This includes follow-on spare parts support. If an item will not be supported through its remaining service life, including EDA and obsolete defense articles, an explanation should be included in the LOA.53

60

FMS cases may be amended or modified to accommodate certain changes. An amendment is necessary when a change requires purchaser acceptance. The scope of the case is a key issue for the IA to consider in deciding whether to prepare an amendment, modification, or new LOA. In defined order cases, scope is limited to the quantity of items or described services, including specific performance periods listed on the LOA. In blanket order cases, scope is limited to the specified item or service categories and the case or line dollar value. In CLSSAs, scope is limited by the LOA description of end items to be supported and dollar values of the cases. A scope change takes place when the original purpose of a case line or note changes. U.S. government unilateral changes to an FMS case are made by a modification and do not require acceptance by the purchaser.61

“Pseudo-LOAs” For Title 10 Security Cooperation

DSCA uses the FMS infrastructure to implement grant-based security cooperation programs authorized under Title 10, also known as a Building Partner Capacity (BPC) cases. Similar to an FMS LOR, a BPC case starts with a Memorandum of Request (MOR), which wil identify the required defense services, equipment, and legal authority.62 During case development, the IA and the SCO or Combatant Command coordinate to document the requirements and costs of BPC MOR on a “pseudo-Letter of Offer and Acceptance (LOA).”63 DSCA then conducts a quality assurance review, prepares the final version of the LOA, and coordinates review and approval by DSCA and the U.S. Department of State.64

the purchaser.54

|

"Pseudo LOAs" For Title 10 Authorizations DSCA (along with DOS and DOD elements) use the FMS infrastructure to manage some programs that are not actual FMS cases. These occur when the U.S. government provides defense articles and defense services aimed at Building Partner Capacity, or BPC. Authorized under Title 10 (the most common is 10 U.S.C.§333), and often associated with train and equip programs, cases are coordinated and processed through established security assistance automated systems designed to handle FMS. When these occur, practitioners refer to the process as a "pseudo LOA" to distinguish the cases from FMS.55 |

Customs Clearance

Customs Clearance

In all FMS cases, the firms then ship the defense articles to the foreign partner via a third-party freight forwarding company. The security cooperation organization, part of the U.S. embassy country team, may receive the item and hand it over to the purchaser, or the purchaser may receive it directly. The U.S. government and the purchaser'’s advanced planning for transportation 58 DSCA, SAMM, C.6.2. Case Execution - General Information. 59 DSCA, SAMM, C6.2.5. Execution Records. 60 DSCA, SAMM, C6.4. Case Execution - Logistics. 61 DSCA, SAMM, C6.7.1. Amendments. 62 MORs have a specific format, which includes an Excel spreadsheet, PowerPoint “Quad Charts,” and Country Team Assessment. For more information, see DOD, Defense Security Cooperation Agency, Security Assistance Management Manual (SAMM), Chapter 15 (C15) Table 4 (T4), “MOR Information.”

63 DSCA, SAMM, C15.3.2. Initiating a Pseudo LOA and Table C15.T5. Instructions for Preparing Pseudo LOAs. 64 Defense Security Cooperation University’s (DSCU) Security Cooperation Management “Greenbook,” Edition 42, p. 6-5 (Fiscal Year 2022). See also CRS Report R44313, What Is “Building Partner Capacity?” Issues for Congress, coordinated by Kathleen J. McInnis.

Congressional Research Service

14

link to page 21 Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

s advanced planning for transportation of materiel is critical for case development and execution. DOD policy requires that the purchaser is responsible for transportation and delivery of its purchased materiel. Purchasers can use DOD distribution capabilities on a reimbursable basis at DOD reimbursable rates via the Defense Transportation System (DTS). Alternatively, purchasers may employ an agent, known as a Foreign Military Sales freight forwarder, to manage transportation and delivery from the point of origin (typically the continental United States) to the purchaser'’s desired destination.56 65 Ultimately, the purchaser is responsible for obtaining overseas customs clearances and for all actions and costs associated with customs clearances for deliveries of FMS materiel, including any intermediate stops or transfer points.57

66

Generally, title to FMS materiel is transferred to the purchaser upon release from its point of origin, normally a DOD supply activity, unless otherwise specified in the LOA. However, U.S. government security responsibility does not cease until the recipient'’s designated government representative assumes control of the consignment. 58

67 Direct Commercial Sales Process

DOS Role in DCS

While an export license is not required for the FMS transfers,5968 registered U.S. firms may sell defense articles directly to foreign partners via licenses receivedwhen they receive licenses to do so from the State Department. In this case, the request for defense articles and/or defense services may originate as a result of interaction between the U.S. firm and a foreign government, may be initiated through the country team in U.S. embassies overseas, or may be generated by foreign diplomatic or defense personnel stationed in the United States. A significant difference between DCS licenses and FMS cases is that in DCS, the U.S government does not participate in the sale or broker the defense articles or services for transfer by the U.S. government to the foreign country.

While DCS originates between registered U.S. firms and foreign customers, an application for an export license goes through a review process similar to FMS (Figure 2, below). DOS and DOD have agency review processes that assess proposed DCS transfers for foreign policy, national security, human rights, and nonproliferation concerns. In order for a U.S. firm to export defense articles or services on the U.S. Munitions List (USML), it must first register with the State Department, Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC). It must then obtain export licenses for all defense articles and follow the International Traffic in Arms Regulations.60 (ITAR).69 Once granted, an export license is valid for four years, after which a new application and license are required.70

65 DSCA, SAMM, C7.5. FMS Freight Forwarders. 66 DSCA, SAMM, C3.3.3.2. Overseas Customs Clearance Requirements for DoD-Sponsored Shipments and C3.3.3.4.3. Overseas Customs Clearance Requirements for Purchaser-Sponsored Shipments.

67 DSCA, SAMM, C7.3. Title Transfer. A supply activity can be either a DOD storage depot or a commercial vendor that furnishes materiel under a DOD-administered contract.

68 DSCA, SAMM, C3.3. Export License and Customs Clearance. 69 Firms may do so through DDTC’s website: https://www.pmddtc.state.gov//ddtc_public. 70 22 CFR §123.21.

Congressional Research Service

15

Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

required.61

Congressional Notification Requirements for DCS71

The AECA, Section 36(b) (22 U.S.C. §2776(c)), specifies reporting to Congress on the

Congress reviews formal notifications pursuant to procedures in the AECA and has the authority to block a sale. |

To export a defense article through DCS, a U.S. defense firm must comply with ITAR requirements. Within DDTC, the offices of Defense Trade Controls Policy (DTCP), Defense Trade Controls Licensing (DTCL), and Defense Trade Controls Compliance (DTCC) are responsible for publishing policy, issuing licenses, and enforcingrequirements. The three Directorates of the State Department's Bureau of Political-Military Affairs publish policy, issue licenses, and enforce compliance in accord with the ITAR in order to ensure commercial exports of defense articles and defense services advance U.S. national security and foreign policy objectives.6372 If marketing efforts involve the disclosure of technical data or the temporary export of defense articles, the defense firm must also obtain the appropriate export license from DDTC.64

DOD'73

DOD’s Defense Technology Security Administration (DTSA) serves as a reviewing agency for the export licensing of dual-use commodities and munitions items and provides technical and policy assessments of export license applications. Specifically, it identifies and mitigates national security risks associated with the international transfer of critical information and advanced technology in order to maintain the U.S. military'’s technological edge and to support U.S. national security objectives.65

74

The ITAR includes many exemptions from the licensing requirements. Some are self-executing by the exporting firm who is to use them and normally are based on prior authorizations. Other exemptions (for example, the exemption in 22 CFR 125.4(b)(1) regarding technical data) may be requested or directed by the supporting military department or DOD agency. 66

DOD Role in DCS

In contrast to FMS, DOD does not directly administer sales or facilitate transportation of items purchased under DCS, although, unless the host countryinternational partner requests that purchase be made through FMS, DOD tries to accommodate a U.S. defense firm'’s preference for DCS, if articulated. In addition, DOD does not normally provide price quotes for comparison of FMS to DCS.76 DCS.67 If a company or countryinternational partner prefers that a sale be made commercially rather than via FMS, and when a company receives a request for proposal from a countryan international partner and prefers DCS, the company may request that DSCA issue a DCS preference for that particular sale. The particulars of each recipient countryinternational partner, U.S. firm, and sale determine whether FMS or DCS is preferred.

77

Before approving DCS preference for a specific transaction, DSCA considers the following:68

- 78

76 DSCA, SAMM, C2.1.8.6. Direct Commercial Sales (DCS) Versus FMS Sales. 77 Defense Security Cooperation University’s (DSCU) Security Cooperation Management “Greenbook,” Edition 42, pages 15-5 through 15-13 (Fiscal Year 2022).

78 DSCA, SAMM, C4.3.6. Direct Commercial Sales (DCS) Preference. See also, DSCU, “Greenbook,” p. 15-3 and 15-13 through 15-17.

Congressional Research Service

17

Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

Items provided through blanket order and those required in conjunction with a

system sale do not normally qualify for DCS preference.

-

FMS procedures may be required in sales to certain countries and for sales

financed with Military Assistance Program (MAP) funds or, in most cases, with FMF funds.

- The DSCA Director may also recommend to the DOS that it mandate FMS for a specific sale.

-

DCS preferences are valid for one year; therefore, during this time, if the IA

receives from the purchaser a request for pricing and availability (P&A) or an LOA for the same item, it should notify the purchaser of the DCS preference.

69

79

U.S. firms may request defense articles and services from DOD to support a DCS to a foreign country or international organization.70an international partner.80 Defense articles must be provided pursuant to applicable statutory authority, including 22 U.S.C. §2770, which authorizes the sale of defense articles or defense services to U.S. companies at not less than their estimated replacement cost (or actual cost in the case of services).

SCO chiefs often interact with visiting U.S. defense industry representatives and respond to case of services).

The SCO chief and other relevant members of the country team normally meet with visiting U.S. defense industry representatives regarding their experiences in country. The SCO chief responds to follow-up inquiries from industry representatives with respect to any reactions from host country officials or subsequent marketing efforts by foreign competitors. The SCO chief alerts embassy staff to observe reactions of the host country officials on U.S. defense industry marketing efforts. As appropriate, the SCO chief can pass these reactions to the U.S. industry representatives. However, the SCOinternational partner officials. However, SCOs may not work on behalf of any specific U.S. firm; its only preference can be for purchasers to "“buy American."” If the SCO chief believes that a firm's ’s marketing efforts do not coincide with overall U.S. defense interests or have potential for damaging U.S. credibility and relations with the countryinternational partner, the SCO chief relays these concerns, along with a request for guidance, throughout the country team and to the Combatant Command, Military Department, and DSCA.71

up the chain to DSCA.81 Excess Defense Articles

If aan international partner is unable to purchase, or wishes to avoid purchasing, a newly-manufactured U.S. defense article, itthey may request transfer of Excess Defense Articles from DOD to its designated recipient.72(EDA) from DOD.82 EDA refers to DOD and United States Coast Guard (USCG)-owned defense articles that are no longer needed and, as a result, have been declared excess by the U.S. Armed Forces. This excess equipment is offered at reduced or no cost to eligible foreign recipients on an "as international partners on an “as is, where is"” basis.7383 As such, EDA is a hybrid between sales and grant transfer programs. DOD states that the EDA program works best in assisting friends and allies to augment current inventories of like items with a support structure already in place.7484 All FMS eligible countries can request EDA. An EDA grant transfer to a country must be justified to Congress for the fiscal year in which the transfer is proposed as part of the annual congressional justification documents

79 DSCA, SAMM, Ibid. 80 DSCA, SAMM, C4.3.13. Department of Defense Support to Direct Commercial Sales. 81 DSCA, SAMM, C2.1.8. SCO Support to Industry. 82 22 U.S.C. §2761, 22 U.S.C. §2321j, and 22 U.S.C. §2314 authorize sales and grants from DOD stocks. DSCA maintains a database of EDA at https://www.dsca.mil//programs//excess-defense-articles-eda, last updated June 15, 2020.

83 DSCA, SAMM, C11.3.1. Definition and Purpose. In practice, this means that international partners must pay all refurbishment costs and transportation costs. In some cases, international partners may use FMF to open a transportation case that enables them to receive the EDA. The cost of refurbishment is often a deterrent to seeking EDA transfer.

84 Ibid.

Congressional Research Service

18

Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities

for military assistance programs.85for military assistance programs.75 There is no guarantee that any EDA offer will be made on a grant basis; each EDA transfer is considered on a case-by-case basis.7686 EDA grants or sales that contain significant military equipment or with an original acquisition cost of $7 million or more require a 30-calendar day congressional notification.77

87

Title to EDA items transfers at the point of origin, except for items located in Germany; those EDA items transfer title at the nearest point of debarkation outside of Germany. All purchasers or grant recipients must agree that they will not transfer title or possession of any defense article or related training or other defense services to any other country without prior consent from DOS pursuant to 22 U.S.C. §2753 and 22 U.S.C. §2314.