Tax Incentives for Opportunity Zones

Changes from June 28, 2019 to December 7, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Tax Incentives for Opportunity Zones: In Brief

Contents

Figures

FigureTax Incentives for Opportunity Zones December 7, 2020 The 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97) temporarily authorized Opportunity Zone (OZ) tax incentives, which are intended to encourage private investment in economically distressed Sean Lowry communities. OZ tax incentives are allowed for investments held by Qualified Opportunity Analyst in Public Finance Funds (QOFs) in qualified OZs. In 2018, the Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund in the Treasury Department designated qualified census tracts that are eligible for OZ tax incentives after receiving recommendations from head executives (e.g., govern ors) at the Donald J. Marples state level. Qualified OZ designations for census tracts are in effect through the end of 2026. Specialist in Public Finance OZ tax incentives include (1) a temporary tax deferral for capital gains reinvested in a QOF, (2) a step-up in basis for any investment in a QOF held for at least five years (10% basis increase) or seven years (15% basis increase), and (3) a permanent exclusion of capital gains from the sale or exchange of an investment in a QOF held for at least 10 years. This report discusses (1) which census tracts have been designated as an OZ, (2) what types of entities are eligible as QOFs, (3) the tax benefits of investments in QOFs, (4) a summary of IRS/Treasury regulations implementing OZs, (5) what economic effects can be expected from OZ tax incentives, and (6) what policy issues Congress has raised with respect to OZs. This report also discusses several issues for Congress regarding the implementation of OZ tax incentives. First, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has determined that the list of census tracts designated as qualified OZs cannot be altered absent enactment of new legislation. Second, given that Treasury and IRS have promulgated final regulations regarding tax-related issues pertaining to OZ transactions, state and local governments are likely to play a larger role in the types of projects that will be funded in OZs. Some states have enacted their own OZ tax incentives to further encourage investment in their jurisdictions. Additionally, local government entities will be in charge of approving and permitting individual projects within an OZ. Third, although state and local governments will likely now have a more direct role in individual OZ transactions, the federal government may still be involved. For example, President Trump issued an execut ive order requiring executive agencies to determine how they can prioritize or focus federal programs in economically distressed communities, including OZs. Agencies were charged with reducing regulatory and administrative costs that could discourage public and private investment in such areas. Fourth, Congress could consider extending deadlines for specific OZ tax benefits. Under current law, an investor would have needed to roll over a capital gain by the end of 2019 in order to get seven years credit for holding their investment in a QOF, for the purposes of the 15% basis adjustment. While an investor can still get a 10% basis adjustment under current law, Congress could amend the law to provide for a larger incentive for post-2019 investment. OZs have also been subject to a number of congressional oversight concerns. Based on the requests of individual Members of Congress, the Treasury Inspector General and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) have conducted or are currently conducting investigations regarding the qualified OZ designation process and potential effectiveness of OZs to spur investment in low-income areas, respectively. Additionally, there has been a broader concern, from both Members of Congress and commentators, on the lack of information and transparency regarding QOFs, their investments, and their investors required under current law. More QOF disclosure on tax forms could aid the IRS in administering OZ tax incentives as well as providing data that could be used to evaluate these p rovisions. Although current law would likely limit the IRS’s ability to disclose detailed taxpayer-provided data to the public without taxpayer consent, it could release aggregated data, such as amounts of OZ investments organized at state or local levels or the tax benefits claimed by income level. This information could provide the public with a better idea of how the direct benefits of OZ tax incentives are distributed. However, additional disclosure could increase compliance costs and could dissuade some investors from investing in OZs. Congressional Research Service link to page 4 link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 10 link to page 10 link to page 11 link to page 12 link to page 12 link to page 12 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 19 link to page 19 link to page 17 link to page 19 link to page 19 link to page 21 Tax Incentives for Opportunity Zones Contents Opportunity Zone Designations ......................................................................................... 1 Qualified Opportunity Funds ............................................................................................ 2 Tax Benefits for Qualified OZ Investments ......................................................................... 3 Implementing Regulations .......................................................................................... 6 Expected Economic Effects of OZs .................................................................................... 7 Effects on Employment .............................................................................................. 7 Effects on Investment ................................................................................................. 7 Revenue Effects .............................................................................................................. 8 Issues for Congress ......................................................................................................... 9 Changing Designation of Qualified Opportunity Zones.................................................... 9 Roles of Federal and Subnational Governments.............................................................. 9 Coordination of Federal Economic Development Programs with Opportunity Zones.......... 10 Timeline of Tax Benefits........................................................................................... 10 Congressional Oversight ........................................................................................... 11 Designation of Qualified Opportunity Zones........................................................... 11 Efficacy of OZs to Improve Economic Conditions of Low-Income Areas.................... 11 Data and Reporting Requirements on Beneficial Investors and Projects ...................... 12 Figures Figure A-1. CDFI Fund Mapping Tool Showing Designated Opportunity Zones (OZs) in the Southeast ............................................................................................................. 15 Tables Table 1. Il ustration of Opportunity Zone (OZ) Tax Benefits for a Hypothetical Investment of $100,000 in Reinvested Capital Gains Made in 2019...................................... 4 Table 21. CDFI Fund Mapping Tool Showing Designated Opportunity Zones (OZs)

Tables

Table 1. Maximum Number of Census Tracts Eligible for Opportunity Zone Designation, by State or Territory, 2018 ........................................................................................... 16 Appendixes Appendix A. Il ustration of CDFI OZ Mapping Tool........................................................... 14 Appendix B. Number of Census Tracts Eligible in Each State for Qualified OZ Designation ............................................................................................................... 16 Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 18 Congressional Research Service Tax Incentives for Opportunity Zonesby State or Territory- Table 2. Illustration of Opportunity Zone (OZ) Tax Benefits for a Hypothetical Investment of $100,000 in Reinvested Capital Gains Made in 2019

The 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97) temporarily authorized Opportunity Zone (OZ) tax incentives for investments held by Qualified Opportunity Funds (QOFs) in qualified OZs.1 The Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund (hereinafter, the "Fund"), organized under the Department of the Treasury,incentives, which are intended to encourage private investment in economical y distressed

T communities.1 In 2018, the Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund

in the Treasury Department designated qualified census tracts that are eligible for OZ tax incentives after receiving recommendations from the head executives at the state level. Qualified OZ designations are in effect through 2026. The tax benefits for these a state’s chief executive officer (CEO),

general y the governor. Qualified OZ designations are in effect through the end of 2026.

Investments eligible for OZ tax incentives must be channeled through a qualified opportunity fund (QOF). The tax benefits for these QOF investments include (1) a temporary tax deferral for

capital gains reinvested in a QOF, (2) a step-up in basis for any investment in a QOF held for at least five years (10% basis increase) or seven years (15% basis increase), and (3) a permanent exclusion of capital gains from the sale or exchange of an investment in a QOF held for at least 10 years.

This report briefly These incentives effectively increase the after-tax rate of return of QOF investments to

their investors.

This report describes what census tracts have been designated as an OZ, what types of entities can are eligible are eligible as QOFs, the tax benefits of investments in QOFs, and what economic effects can be expected from OZ tax incentives.

, and several issues for Congress regarding the implementation and

oversight of OZ tax incentives.

For further reading on the CDFI Fund’Fund's other programs and analysis of related policy issues, see CRS Report R42770, Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund: Programs

and Policy Issues, by Sean Lowry. (Throughout this report, the CDFI Fund is referred to simply as “the Fund”.) For updated guidance regarding OZ tax incentives, including any IRSInternal Revenue Service (IRS) notices and proposed regulations, see websites created by the Fund and IRS.2

Opportunity Zone Designations

To become a qualified OZ, the CEO (e.g., governor) of the state must have

IRS.2

Opportunity Zone Designations Opportunity zones were nominated by states’ CEOs (e.g., governors) in early 2018. Specifical y,

states’ CEOs nominated, in writing, a limited number of census tracts to the Secretary of the Treasury.3Treasury to be designated eligible for OZ tax incentives.3 These nominations were due by March 21, 2018.4 A nominated tract must have been either (1) a qualified low-income community (LIC), using the same criteria as eligibility under the New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC),45 or (2) a census tract that was contiguous with a nominated LIC if the median family income of the tract doesdid not

exceed 125% of that contiguous, nominated LIC.6 In principle, these requirements appear to have

1 T hese provisions amend the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) as Sections 1400Z-1 and 1400Z-2. 2 CDFI Fund, “Opportunity Zone Resources,” at https://www.cdfifund.gov/Pages/Opportunity-Zones.aspx; and IRS, “Opportunity Zones Frequently Asked Questions,” at https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/opportunity-zones-frequently-asked-questions.

3 For the purposes of OZ tax incentives, a “state” includes the District of Columbia and any U.S. possession. 4 IRS Rev. Proc. 2018-16, p. 3, at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-18-16.pdf. 5 See IRC Section 45D(e). Qualifying LICs, under the NMT C, include census tracts that have at least one of the following criteria: (1) a poverty rate of at least 20%; (2) a median family income below 80% of the greater of the statewide or metropolitan area median family income if the LIC is located in a metropolitan area; or (3) a median family income below 80% of the median statewide family income if the LIC is located outside a metropolitan area. In addition, designated targeted populations may be treated as LICs. For more information, see CRS Report RL34402, New Markets Tax Credit: An Introduction, by Donald J. Marples and Sean Lowry.

6 See IRS Rev. Proc. 2018-16, p. 2, at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-18-16.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

1

Tax Incentives for Opportunity Zones: In Brief

been intended to provide governors with the ability to identify LICs, or low - to moderate-income

areas adjacent to LICs, in which to direct OZ tax benefits.7

P.L. 115-97 explicitlyexceed 125% of that contiguous, nominated LIC.5 Nominations were due to the Fund by March 21, 2018.6

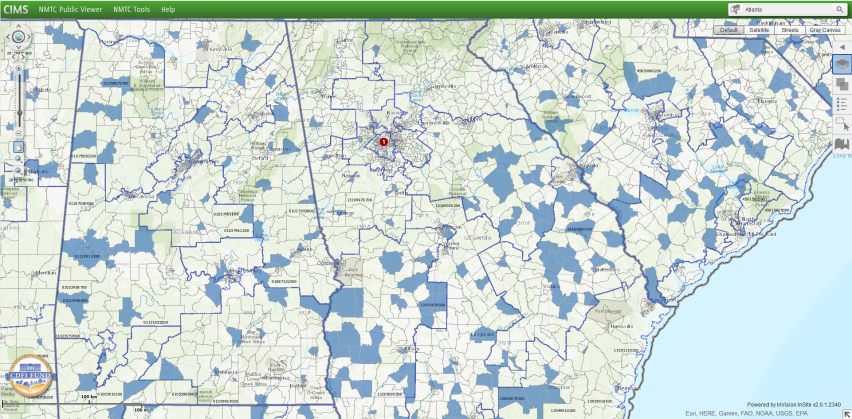

Figure 1 provides a screenshot of the Fund's online mapping tool, which displays census tracts that have been designated as a qualified OZ by the state or territory's CEO and approved by the Fund. A complete list of qualified OZs has been published as an IRS Internal Revenue Bulletin and is available on the Fund's "Opportunity Zone" website.7

|

|

|

Source: CRS screenshot of CDFI Fund, CIMS mapping tool, accessed November 11, 2018, at https://www.cims.cdfifund.gov/preparation/?config=config_nmtc.xml. Notes: Designated OZs are shown in blue. Congressional district borders have been enabled in the above screenshot. |

P.L. 115-97 limits the number of census tracts within a state that can be designated as limits the number of census tracts within a state that can be designated as

qualified OZs based on the following criteria:

- If the number of LICs in a state is less than 100, then a total of 25 census tracts may be designated as qualified OZs.

-

If the number of LICs in a state is 100 or more, then the maximum number of

census tracts that may be designated as qualified OZs is equal to 25% of the total number of LICs.

-

Not more than 5% of the census tracts designated as qualified OZs in a state can

be non-LIC tracts that are contiguous to nominated LICs. This effectively limits the number of census tracts that are not economical y distressed or low income from receiving the OZ designation.

The official list of designated Opportunity Zones was published in IRS Notice 2018-488 and IRS

Notice 2019-42.9

Qualified Opportunity Funds P.L. 115-97 defined a QOF as any investment vehicle organized as a corporation or partnership for the purpose of investing in a qualified opportunity zone property (other than another QOF) and which holds at least 90% of its assets in qualified OZ property. A qualified OZ property can be a stock or partnership interest in a business located within a qualified OZ or tangible business property located in a qualified OZ. Examples of potential QOF investments in qualified OZ property include purchasing a building located in a qualified OZ, purchasing stock in a business

located in a qualified OZ, or purchasing machinery used by a business located in a qualified OZ.

A qualified OZ property must have been acquired by the QOF after December 31, 2017. For each

month that a QOF fails to meet the 90% requirement it must general y pay a penalty. The penalty is calculated based on the monthly shortage multiplied by an underpayment rate (short-term

federal interest rate plus three percentage points).

The IRS instructs a corporation or partnership seeking to become a QOF to self-certify its status by fil ing out Form 8996 as part of its annual income tax filings.10 (This self-certification process differs from the NMTC, in which the Fund takes prospective action to certify “community

development entities” (CDEs) before they can receive an NMTC al ocation.)

7 See Senator T im Scott, “Op-ed: Opportunity Zones Are Really Working,” Washington Examiner, October 18, 2019, at https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/op -eds/sen-tim-scott-opportunity-zones-are-really-working. In his op-ed, Senator Scott, who co-sponsored the original, standalone bill proposing OZs, says that “ …instead of taking a top-down approach to addressing poverty, Opportunity Zones empower our community leaders, mayors, and governors to come together to decide for themselves which of their neighborhoods should be designated to pa rticipate.” T hat standalone bill in the 115th Congress was the Investing in Opportunity Act (H.R. 828; S. 293). 8 Internal Revenue Service, Internal Revenue Bulletin, Bulletin No. 2018-28, Washington, DC, July 9, 2018, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-18-48.pdf.

9 Internal Revenue Service, Internal Revenue Bulletin, Bulletin No. 2019-29, Washington, DC, July 15, 2019, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-19-42.pdf.

10 For more information, see IRS, “Opportunity Zones Frequently Asked Questions,” at https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/opportunity -zones-frequently-asked-questions.

Congressional Research Service

2

link to page 7 link to page 7 Tax Incentives for Opportunity Zones: In Brief

Tax Benefits for Qualified OZ Investments P.L. 115-97 provides three main tax incentives to encourage investment in qualified OZs. These benefits are briefly summarized, followed by an il ustrative example showing how the three

benefits reduce the amount of capital gains subject to taxation for OZ investors:

1. Temporary deferral of capital gains that are reinvested in qualified OZ

property:

be non-LIC tracts that are contiguous to nominated LICs.

Table 1 displays the maximum number of census tracts in each state or territory that were eligible for OZ designation under each of the two nomination criteria. These data, current as of February 27, 2018, were posted on the Fund's website before the qualified OZ recommendations issued by state or territory CEOs were certified.

Table 1. Maximum Number of Census Tracts Eligible for Opportunity Zone Designation, by State or Territory

|

A |

B |

C |

|

|

State/Territory |

Total Number of Low-Income Community (LIC) Tracts in State |

Maximum Number of Tracts That Can Be Nominated (the Greater of 25% of All LICs or 25 If State Has Fewer Than 100 LICs) |

Maximum Number of Eligible Non-LIC Contiguous Tracts That Can Be Nominated (5% of Column B) |

|

Alabama |

629 |

158 |

8 |

|

Alaska |

55 |

25 |

2 |

|

American Samoa |

16 |

25 |

See Notes |

|

Arizona |

671 |

168 |

9 |

|

Arkansas |

340 |

85 |

5 |

|

California |

3,516 |

879 |

44 |

|

Colorado |

501 |

126 |

7 |

|

Connecticut |

286 |

72 |

4 |

|

Delaware |

80 |

25 |

2 |

|

District of Columbia |

97 |

25 |

2 |

|

Florida |

1,706 |

427 |

22 |

|

Georgia |

1,039 |

260 |

13 |

|

Guam |

31 |

25 |

2 |

|

Hawaii |

99 |

25 |

2 |

|

Idaho |

109 |

28 |

2 |

|

Illinois |

1,305 |

327 |

17 |

|

Indiana |

621 |

156 |

8 |

|

Iowa |

247 |

62 |

4 |

|

Kansas |

295 |

74 |

4 |

|

Kentucky |

573 |

144 |

8 |

|

Louisiana |

597 |

150 |

8 |

|

Maine |

128 |

32 |

2 |

|

Maryland |

593 |

149 |

8 |

|

Massachusetts |

550 |

138 |

7 |

|

Michigan |

1,152 |

288 |

15 |

|

Minnesota |

509 |

128 |

7 |

|

Mississippi |

399 |

100 |

5 |

|

Missouri |

641 |

161 |

9 |

|

Montana |

90 |

25 |

2 |

|

Nebraska |

176 |

44 |

3 |

|

Nevada |

243 |

61 |

4 |

|

New Hampshire |

105 |

27 |

2 |

|

New Jersey |

676 |

169 |

9 |

|

New Mexico |

249 |

63 |

4 |

|

New York |

2,055 |

514 |

26 |

|

North Carolina |

1,007 |

252 |

13 |

|

North Dakota |

50 |

25 |

2 |

|

Northern Mariana Islands |

20 |

25 |

See Notes |

|

Ohio |

1,280 |

320 |

16 |

|

Oklahoma |

465 |

117 |

6 |

|

Oregon |

342 |

86 |

5 |

|

Pennsylvania |

1,197 |

300 |

15 |

|

Puerto Rico |

835 |

See Notes |

See Notes |

|

Rhode Island |

78 |

25 |

2 |

|

South Carolina |

538 |

135 |

7 |

|

South Dakota |

69 |

25 |

2 |

|

Tennessee |

702 |

176 |

9 |

|

Texas |

2,510 |

628 |

32 |

|

Utah |

181 |

46 |

3 |

|

Vermont |

48 |

25 |

2 |

|

Virgin Islands |

13 |

25 |

See Notes |

|

Virginia |

847 |

212 |

11 |

|

Washington |

555 |

139 |

7 |

|

West Virginia |

220 |

55 |

3 |

|

Wisconsin |

479 |

120 |

6 |

|

Wyoming |

33 |

25 |

2 |

Source: CDFI Fund, "Opportunity Zones Information Resources," February 27, 2018, at https://www.cdfifund.gov/Pages/Opportunity-Zones.aspx.

Notes: These data are still available on the website, above, as of the publication date of this report.

Puerto Rico: The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123) deemed each population census tract in Puerto Rico that is a low-income community to be certified and designated as a qualified OZ. As of the time these data were being posted, the maximum number of tracts that can be nominated by Puerto Rico as well as the maximum number of Eligible Non-LIC Contiguous Tracts that could have been included in that nomination was being determined by the Fund.

USVI: The U.S. Virgin Islands could nominate Eligible Non-LIC Contiguous Tracts, provided that the nominated non-LIC tracts do not exceed 5% of all nominated tracts (both low-income communities and nominated contiguous tracts). Thus the USVI could nominate no more than one of its Eligible Non-LIC Contiguous Tracts.

Northern Mariana Islands and American Samoa: Neither the Northern Mariana Islands nor American Samoa had any Eligible Non-LIC Contiguous Tracts.

What Is a Qualified Opportunity Fund?

P.L. 115-97 defined a QOF as any investment vehicle which is organized as a corporation or partnership for the purpose of investing in qualified opportunity zone property (other than another QOF) that holds at least 90% of its assets in qualified OZ property. Qualified OZ property can be stock or partnership interest in a business located within a qualified OZ or tangible business property located in a qualified OZ. Qualified OZ property must have been acquired by the QOF after December 31, 2017. For each month that a QOF fails to meet the 90% requirement it must pay a penalty equal to the excess of the amount equal to 90% of its aggregate assets divided by the aggregate amount of qualified OZ property held by a QOF multiplied by an underpayment rate (short-term federal interest rate plus three percentage points). There is an exception from this general penalty for reasonable cause.

The IRS instructs corporations or partnerships seeking to become a QOF to self-certify this status by filling out Form 8996 as part of their annual income tax filings.8 This self-certification process differs from the NMTC, in which the Fund takes prospective action to certify "community development entities" (CDE) before that CDE can receive an NMTC allocation.

What Are the Tax Benefits for Qualified Investments?

P.L. 115-97 provides for three main tax incentives to encourage investment in qualified OZs:

1. Temporary deferral of capital gains that are reinvested in qualified OZ property:Taxpayers can defer capital gains tax due upon sale or disposition of a (presumably non-OZ) asset if the capital gain portion of that asset is reinvested within 180 days in a QOF.911 Under current law, the deferral of gain is available on qualified investments up until the earlier of:(a) the date on which the investment in the QOF is sold or exchanged, or (b) December 31, 2026.102.12 In other words, this deferral is only in effect until December 31, 2026. Any reinvested capital gains in a QOF made before this date must be realized on December 31, 2026. Thus, investors would realize the deferred gain in their 2026 income filings, even if they do not sel or dispose of their investment in a QOF. Any reinvested capital gains in a QOF after this date are not eligible for deferral. 2. Step-up in basis for investments held in QOFs: If the investment in the QOF is held by the taxpayer for at least five years, the basis on the original gain is increased by 10% of the original gain. Basis is general y the value of capital gain when the investment is sold, before it is reinvested in a QOF.13 (An increase in basis, al else unchanged, reduces the amount of the investment subject to taxation and hence reduces tax liability.)increased by 10% of the original gain.If the OZ asset or investment is held by the taxpayer for at least seven years, the basis on the original gain is increased by an additional3. Exclusion3. Exclusion of capital gains tax on qualified OZ investmentreturnsreturns held for atleast10least 10 years: The basis of investments maintained (a) for at least 10 years and (b) until at least December 31, 2026,willwil be eligible

Table 2 illustrates

Table 1 il ustrates the tax benefits toof a hypothetical investment of $100,000 in a QOF made in 2019. This investment could be $100,000 in capital gains earned from the sale or disposition of another asset (e.g., real property) from outside of an OZ that is reinvested into a QOF within 180 days from the date of that sale or disposition. Taxes on these capital gains are deferred while the

investment is held in a QOF.

Column A shows the investment'’s value over time, assuming a 7% annuallyannual y compounded rate of return. This hypothetical investment is simplified to assume that an initial investment is made in a QOF investment in a QOF is

11 For more background on capital gains taxation, see CRS Report 96-769, Capital Gains Taxes: An Overview, by Jane G. Gravelle; and p. 391 in CRS Committee Print CP10003, Tax Expenditures: Com pendium of Background Material on Individual Provisions — A Com m ittee Print Prepared for the Senate Com m ittee on the Budget, 2018 , by Jane G. Gravelle et al.

12 IRC Section 1400Z-2(b)(1). 13 For example, an investor buys a piece of commercial real estate for $500,000 and then sells it two years later for $600,000. Although the investor realized $100,000 in capital gain on the sale of the real estate, the gain would not be recognized (subject to tax) upon sale if reinvested within 180 days in a QOF. T he “ basis adjustments” would affect the $100,000 reinvested capital gains. T his calculation is illustrated in Table 1.

Congressional Research Service

3

link to page 8 Tax Incentives for Opportunity Zones: In Brief

made in year one and the QOF constantly reinvests any returns to that initial investment (i.e., the

in year one and the QOF constantly reinvests any returns to that initial investment (i.e., the QOF does not pay out periodic dividends to the investor during the life of the investment).

Column B shows the increase in adjusted basis earned from holding that investment in a QOF

over time: 10% of the original capital gain of $100,000 after the investment is held in a QOF for at least five years (10% of $100,000 = $10,000), and 15% after the capital gain is held for at least

seven years.

(15% of $100,000=$15,000).

Column C shows the mandatory recognition of reinvested capital gains at the end of 2026.1114 Even if the investor retains their investment in the QOF beyond 2026, they must still recognize $85,000 in capital gains under this hypothetical.12

Column D shows the basis for capital gains taxstil recognize or pay capital gains tax on $85,000 in capital gains under this hypothetical example. This adjustment amount is calculated as $100,000 in capital gains initial y rolled over into the QOF in 2019 (i.e., tax deferred) minus the $15,000 in basis adjustment for holding their investment in the QOF for

seven years.

Column D shows the amount of capital gains subject to taxation if the investment in a QOF is sold or disposed in any of the 10 years shown in the table. Of note, if the investment was sold

after being held for 10 years, then any capital gains earned on the initial y reinvested $100,000 would be completely excluded from tax. In the hypothetical example, the investor earned an additional $96,715 from their initial investment of $100,000. Therefore, if they held that QOF investment for 10 years and then sold it, they would not pay tax on the $96,715 in gains as wel as not paying tax on $15,000 worth of the original investment. (They would have realized $85,000

in capital gains in 2026, and paid capital gains tax on that amount.) In other words, for their investment valued at $196,715 in 2029, the investor would have paid tax on $85,000 of this amount in 2026, with the remainder being tax-free. This calculation il ustrates that a major economic incentive to investing in a QOF is the permanent exclusion of capital gains earned after

the acquisition of the QOF investment.15

Table 1. Illustration of Opportunity Zone (OZ) Tax Benefits

sold or disposed in any of the 10 years shown. One of the three major economic incentives to investing in a QOF is the permanent exclusion of capital gains earned after the acquisition of the QOF investment.13 This is shown in the last year of the table where no additional capital gains would be due if the investment was sold—as $85,000 was previously recognized at the end of 2026 (as shown in Column C).

Table 2. Illustration of Opportunity Zone (OZ) Tax Benefits

for a Hypothetical Investment of $100,000 in Reinvested Capital Gains Made in 2019

(Assuming an annual rate of return of 7%)

A

B

C

D

Mandatory

Recognition of

Reinvested Capital

Taxable Capital

Year

Investment Valuea

Basis Adjustment

Gain

Gains if Sold

2019

$100,000

$0

-

$100,000

2020

$107,000

$0

-

$107,000

14 Ibid. 15 After P.L. 115-97 was enacted, some commentators raised concerns that legislative text created an ambiguity as to whether taxpayers could actually claim the exclusion of qualified OZ investment return gains after 10 years. T his was because the capital gains tax exclusion on OZ investment returns provision requires the QOF to hold investments in an OZ for 10 years. T he OZ designations were authorized by P.L. 115-97 through 2026. Thus, unless Congress extended OZ designations in subsequent legislation, it would have only been possible for QOFs to hold investments in qualified OZs for a maximum of nine years (i.e., 2018 through 2026). However, the Department of the Treasury released proposed regulations on October 19, 2018, clarifying that the benefit available in year 10 would still be available even if the designations expire at the end of 2026. T he proposed regulations state that the benefit will be available until December 31, 2027. T reasury claims that this interpretation is consistent with the legislative intent of P.L. 115-97. See Department of the T reasury, “Treasury, IRS Issue Proposed Regulations on New Opportunity Zone T ax Incentive,” press release, October 19, 2018, at https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/treasury-irs-issue-proposed-regulations-on-new-opportunity-zone-tax-incentive. The related passage is on p. 16 of the proposed regulation.

Congressional Research Service

4

link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 7 link to page 7 Tax Incentives for Opportunity Zones: In Brief

A

B

C

D

Mandatory

Recognition of

Reinvested Capital

Taxable Capital

Year

Investment Valuea

Basis Adjustment

Gain

Gains if Sold

2021

$114,490

$0

-

$114,490

2022

$122,504

$0

-

$122,504

2023

$131,080

$0

-

$131,080

2024

$140,255

$10,000

-

$130,255

2025

$150,073

$10,000

-

$140,073

2026

$160,578

$15,000

$85,000

$60,578

2027

$171,819

-

-

$71,819

2028

$183,846

-

-

$83,846

2029

$196,715

-

-

$0b

Source: CRS calculations. Notes: a. This hypothetical calculates OZ tax benefits from (Assuming an annual rate of return of 7%)

|

A |

B |

C |

D |

|

|

Year |

|

Basis Adjustment |

Mandatory Recognition of Reinvested Capital Gain |

Taxable Capital Gains if Sold |

|

2019 |

$100,000 |

$0 |

- |

$100,000 |

|

2020 |

$107,000 |

$0 |

- |

$107,000 |

|

2021 |

$114,490 |

$0 |

- |

$114,490 |

|

2022 |

$122,504 |

$0 |

- |

$122,504 |

|

2023 |

$131,080 |

$0 |

- |

$131,080 |

|

2024 |

$140,255 |

$10,000 |

- |

$130,255 |

|

2025 |

$150,073 |

$10,000 |

- |

$140,073 |

|

2026 |

$160,578 |

$15,000 |

$85,000 |

$60,578 |

|

2027 |

$171,819 |

- |

- |

$71,819 |

|

2028 |

$183,846 |

- |

- |

$83,846 |

|

2029 |

$196,715 |

- |

- |

|

Source: CRS calculations.

Notes:

a. This hypothetical calculates OZ tax benefits from an initial investment of $100,000 in capital gains earned an initial investment of $100,000 in capital gains earned

from outside of an OZ (e.g., sale of appreciated real property) that is rolled overrol ed over (i.e., not taxed) into a qualified opportunity fund (QOF), assuming constant reinvestment over the life of the OZ investment (i.e., no periodic dividends issued from the qualified opportunity fund to the investor).

b.

b. Investments maintained (a) for at least 10 years and (b) until at least December 31, 2026 , wil , will be eligible for

permanent exclusion of capital gains tax on any gains from the qualified OZ portion of theirthe investment when sold or disposed. In this hypothetical, the $196,715 in earnings over the 10 years that the investment is held in a QOF would be excluded from capital gains tax, and tax would be due on the initial $100,000 in outside capital gains rolled outsid e capital gains rol ed over into the QOF after applying the OZ adjusted basis increase benefit of 15% (i.e., tax due on $85,000 in capital gains).

Note that

Note that Table 2 1 only shows the tax-related benefits of investing in a QOF. It does not include the economic benefits of temporarily deferring capital gains tax on the initial $100,000 investment, which would depend on the time value of money, which is the economic concept that an amount of money available at the present time is general y worth more than the same amount in the future. Accordingly, investors would prefer to defer paying tax because the money they

would use to otherwise pay the tax could be put to some other use with a higher rate of return (e.g., investing in other assets) while their tax bil is deferred. From an income tax collection . From an income tax perspective, though, deferral of capital gains tax just delays a tax liability from one period to

another.

Actual QOF investment structures could differ from the arrangement inin Table 2. As seen in1. With a similar tax benefit, the New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC), investors have developed financial structures that increase the amount of other funding from either private or public sources that are used with the NMTC (i.e., increasing leverage on the NMTC investment).1416 Additional layers of financing structures could increase the

complexity of investment arrangements and costs attributed to fees and transactional costs instead of development.15

16 Under the NMT C, the investor receives a credit equal to 5% of the total amount paid for the stock or capital interest at the time of purchase. For the final four years, the value of the credit is 6% annually. Investors must retain t heir interest in a qualified equity investment throughout the seven -year period. T he NMT C value is 39% of the cost of the qualified equity investment and is claimed over a seven-year credit allowance period. For more information, see CRS Report RL34402, New Markets Tax Credit: An Introduction, by Donald J. Marples and Sean Lowry. Congressional Research Service 5 Tax Incentives for Opportunity Zones: In Brief of development, which could ultimately reduce investment in development projects, al else being equal.17 OZ tax incentives are in effect from the enactment of P.L. 115-97 on December 22, 2017, through December 31, 2026. There is no gain or deferral available with respect to any sale or exchange made after December 31, 2026, and there is no exclusion available for investments in qualified OZs made after December 31, 2026.

Proposed Regulations

Implementing Regulations The Department of the Treasury hasand IRS have issued multiple sets of proposed regulations related to investments in a QOF (under Section 1400Z-2). The most recent notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) wasNotices of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) were published in the Federal Register on October 29, 2018, and May 1, 2019.18 The final

regulation was published in the Federal Register on January 13, 2020.19 These regulations inform investors, QOFs, and other parties that have invested in or are considering investing in projects located within qualified OZs. A comprehensive analysis of the lengthy, final regulation is outside

the scope of this report.20

With that said, commentators have noted that the final regulation provides guidance on a range of transactional matters, such as what types of capital gains may be invested, what qualifies as qualified OZ business property, when QOF transactions trigger or do not trigger recognition of capital gain, when capital gains qualify for the purposes of the 10-year exclusion, and other exit

considerations for investors.21 Some of these positions are consistent with those established in the regulations proposed in 2018 and 2019, whereas other positions in the final regulation represent a

change from the previous regulations.

The final regulation became official y effective on March 13, 2020, but commentators and practitioners have noted that it appears to have mixed guidance for retroactive application. The preamble of the final regulation notes that taxpayers may choose to either rely on the final regulation or the proposed regulations, as long as they pick one or the other consistently.22

17 For more discussion, see Government Accountability Office (GAO), New Markets Tax Credit - Better Controls and Data Are Needed to Ensure Effectiveness, GAO-14-500, July 2014, pp. 5-20, at https://www.gao.gov/assets/670/664717.pdf. 18 Internal Revenue Service (IRS), Department of the Treasury, “Investing in Qualified Opport unity Funds,” 83 Federal Register 54279-54296, October 29, 2018; and 84 Federal Register 18652-18693, May 1, 2019. The regulatory docket (including public comments) on the May proposed rule is available at https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=IRS-2019-0022-0001.

19 IRS, Department of the Treasury, “Investing in Qualified Opportunity Funds,” 85 Federal Register 1866-2001, January 13, 2020.

20 T he final regulation is 136 pages long in the triple-column version printed in the Federal Register, above, and is 544 pages long in the preliminary version posted on the IRS website at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/td-9889.pdf. 21 For shorter summaries of the final regulation, see Marie Sapirie, “Do You Hear the People Sing? A Guide to the Final O-Zone Regs,” Tax Notes Federal, January 6, 2020; and John Sciarretti and Michael Novogradac, Final OZ Regulations - Quick Take, Novogradac, December 19, 2019, https://www.novoco.com/notes-from-novogradac/final-oz-regulations-quick-take. For more detailed summaries of the final regulation, see Lisa M. Zarlenga, John Cobb, and Caitlin R. T harp, Final Opportunity Zone Regulations Provide Som e Much -Needed Clarity, Steptoe & Johnson LLP, December 27, 2019, at https://www.steptoe.com/en/news-publications/final-opportunity-zone-regulations-provide-some-much-needed-clarity.html; and Lisa M. Brill et al., Opportunity Zones: Final Regulations Provide Additional Flexibility, Shearman & Sterling, January 14, 2020, at https://www.shearman.com/perspectives/2020/01/opportunity-zones-final-regulations-provide-additional-flexibility. 22 Some commentators have noted that this choice in applicable regulations could increase short -term complexity and decisions for taxpayers. Stephanie Cumings, “O-Zone Rules Applicability Date Raises Dilemma for Investors,” Tax

Congressional Research Service

6

Tax Incentives for Opportunity Zones: In Brief

Individual sections of the final regulation, though, appear to al ow a taxpayer to apply either the final or a proposed version of the regulations on a section-by-section basis.23 IRS and Treasury

could clarify this issue in subsequent communications.

Expected Economic Effects of OZs Because OZs are a relatively new tax benefit, there are limited data that can be used to assess their specific impacts on economic development. Nonetheless, economic theory and examination

of several other geographical y targeted federal programs and incentives for economic development may provide insights on the expected economic effects of OZs. Examples of similar economic development incentives that are administered through the tax code include the NMTC,24 the low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC),25 and the tax credit for the rehabilitation of

historic structures.26 Below is a brief discussion of potential economic effects of OZs.

Effects on Employment Current place-based economic development tax polices tend to be structured to directly benefit

owners of capital who invest in particular communities or in particular types of projects and to indirectly benefit the residents of low-income communities. The OZ tax incentives follow this structure by delivering a direct benefit to the owners of capital through capital gains tax relief. Benefits delivered in this manner effectively reduce the cost of investment (i.e., the cost of capital). Economic theory would predict that tax subsidies for capital would not directly benefit

workers (e.g., in the form of higher wages).27 While it is too soon for detailed analysis of the OZ

tax incentives, research on the NMTCs has shown limited effects on employment.28

Effects on Investment Studies find that place-based economic development incentives tend to shift investment from one area to another, rather than result in a net increase in aggregate economic activity.29 Previous analysis of economic development tax incentives suggests that any one of these tax incentives on its own might be insufficient to generate a positive investment return from an otherwise

unprofitable development project. However, developers may be able to “stack” the benefits of

Notes Federal, January 15, 2020.

23 For example, see Stephanie Cumings, “Confusion Looms About Which Set of O-Zone Regs to Apply,” Tax Notes Today Federal, January 29, 2020.

24 See CRS Report RL34402, New Markets Tax Credit: An Introduction, by Donald J. Marples and Sean Lowry. 25 See CRS Report RS22389, An Introduction to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, by Mark P. Keightley. 26 See National Park Service, “T ax Incentives for Preserving Historic Properties,” at https://www.nps.gov/tps/tax-incentives.htm.

27 Economic theory suggests that the substitution effect (the use of more capital, relative to labor) could offset the benefits of the output effect (the use of more labor, due to more investment and expanded economic activity). The net effect of these tax subsidies will depend on which effect is larger. For more discussion on the effects of economic development policies targeting capital versus labor, see CRS Report R42770, Com m unity Developm ent Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund: Program s and Policy Issues, by Sean Lowry.

28 Harger, K., A. Ross, and H. Stephens, “What matters the most for economic development? Evidence from the Community Development Financial Institutions Fund,” Papers in Regional Science 98, no. 2, pp. 883 -904, 2019. 29 For a discussion of the economic literature on geographically targeted development policies, see CRS Report R42770, Com m unity Developm ent Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund: Program s and Policy Issues, by Sean Lowry.

Congressional Research Service

7

Tax Incentives for Opportunity Zones: In Brief

multiple federal tax incentives (as wel as any state and local incentives). The sum of these

benefits could make a project located in one area more profitable than alternatives.

OZs and New Markets Tax Credit (NMTCs)

With limited information currently available on the economic effects of OZs, policymakers may compare them to another economic development tax incentive—the NMTC. The NMTC is a nonrefundable tax credit intended to encourage private capital investment in eligible, impoverished, low-income communities. NMTCs are al ocated by the CDFI under a competitive application process. Investors who make qualified equity investments reduce their federal income tax liability by claiming the credit. While both the NMTC and OZs are geographical y targeted and provide tax incentives to investors, several differences between OZs and NMTC discussed below may lessen the applicability of any findings on the NMTC to OZs. One key difference is that OZ tax benefits are available to most investment in OZs, whereas NMTC tax benefits are available to a more limited set of approved investments. This fol ows from the NMTC being limited to a set amount per year ($3.5 bil ion most recently) while the OZ benefits are uncapped. A second difference is that there are no statutory requirements for outcome-based reporting of OZ tax benefits, whereas NMTC tax benefits are subject to such reporting. A Government Accountability Office (GAO) report found a lack of statutory authority for OZ data col ection.30 In contrast, NMTC investments are subject to more statutory restrictions and structural layers of accountability to low-income populations and communities than OZs. For example, the Fund evaluates NMTC applications based on a set of factors. One factor is the potential impact that the investments supported wil have on “community outcomes,” including benefits to low-income persons and jobs directly induced by the investments.31 Investments made by QOFs are eligible to benefit a broad range of potential projects, regardless of their potential “community outcomes.”32 A final difference concerns community focus (investment vehicles for OZs are not required to have a community focus, whereas those for NMTCs are required to have a primary mission of serving or providing investment capital to low-income communities). As a result of these differences between NMTCs and OZs, research findings from the NMTC may not be applicable to OZs. In addition, studying OZs is further complicated because they could direct more investment to low-income communities than the NMTC (as a result of being uncapped), but the investment may be less focused to achieve community outcomes.

Revenue Effects The Joint Committee on Taxation initial y estimated that the OZ tax incentives would result in a revenue loss to the federal government of $1.6 bil ion over 10 years.33 Subsequent tax expenditure estimates were higher: a revenue loss of $8.2 bil ion over 5 years.34 The revenue loss

within the initial 10-year and most recent 5-year budget windows is due to the relatively smal

30 U.S. Government Accountability Office, OPPORTUNITY ZONES: Improved Oversight Needed to Evaluate Tax Expenditure Perform ance, GAO-21-20, October 8, 2020, https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-21-30#summary.

31 For examples of such criteria, see the “Community Outcomes” section of CDFI Fund, NMTC Program —Allocation Application Frequently Asked Questions, June 7, 2018, at https://www.cdfifund.gov/Documents/Updated%202018%20NMT C%20Application%20FAQs%20Document%20-For%20Posting%20MAST ER.pdf. 32 QOF investments made in the following categories are not eligible as investments in “qualified OZ business property”: any private or commercial golf course, country club, massage parlor, hot tub facility, suntan facility, racetrack or other facility used for gambling, or any store the principal business of which is the sale of alcoholic beverages for consumption off premises. See IRC 1400Z-2 and IRC Section 144(c)(6)(B). Further, any capital gains earned from investments from the above types of projects are not be eligible for OZ tax benefits.

33 Joint Committee on T axation, Estimated Revenue Effects of the Conference Agreement for H.R. 1, The “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” JCX-67-17, December 18, 2017, p. 6, at https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5053 . 34 U.S. Congress, Joint Committee on T axation, Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2020-2024, committee print, 116th Cong., October 5, 2020, JCX-23-20, at https://www.jct.gov/publications/2020/jcx-23-20/.

Congressional Research Service

8

link to page 13 link to page 13 Tax Incentives for Opportunity Zones: In Brief

revenue losses associated with the deferral of capital gains tax and the OZ basis adjustments in years 5 and 7. The largest tax benefit associated with OZ tax incentives, the exclusion of capital gains tax on qualified OZ investment returns in year 10, would fal outside of the 10-year budget

window. Those revenue losses would not be expected until 2028 (i.e., FY2028-FY2029).

Issues for Congress

Changing Designation of Qualified Opportunity Zones Some Members of Congress have inquired whether Treasury or IRS have the authority to change designation of qualified OZs from one eligible census tract to another. One potential reason to change an OZ designation could be to support investment in an area that has more viable development projects for investors. However, IRS has stated that such requests cannot be

accommodated, and that IRC Section 1400Z-1 authorized only one determination and designation period for Treasury and IRS to certify and designate census tracts as qualified OZs.35 Under this reasoning, new legislation would need to be enacted to change the amount of qualified OZs, open a new round of OZ designations (e.g., using the most recent economic data), or change criteria for

qualified OZs.

Roles of Federal and Subnational Governments The federal government played an active role in establishing the rules for OZs and continues to

administer the tax benefits to QOFs that engage in OZ-eligible activities. Congress enacted OZs as part of the 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97). The Fund formal y designated census tracts as QOFs that were eligible under the statutory criteria and nominated by state governors. Treasury and the IRS then promulgated regulations on qualified OZ designations and issued additional transactional guidance. As discussed more in “Coordination of Federal Economic Development

Programs with Opportunity Zones,” other agencies could assume a larger role in providing

financial incentives for investment in qualified OZs.

Absent further congressional legislation, subnational governments wil likely play a larger role in

the types of individual projects and activities that wil be supported by OZ investment. For example, governors and state legislatures could seek to promote OZs within their jurisdictions as attractive options for investment, or enact state-level incentives to enhance potential private-sector returns in OZs.36 Like state officials, local government entities can also provide further incentives to attract OZ investments. Local zoning agencies and mayoral offices have the most

direct effect on what projects can proceed within specific OZs. These officials can approve or deny building permits, or grant approval of permits based on the projects meeting certain conditions (e.g., building height variances, promotion of certain goals about population density,

mixed-income housing units).

35 Letter 2019-0025 from William A. Jackson, Chief, Branch 5, IRS Office of Associate Chief Counsel, to Honorable Donald Norcross, Member, U.S. House of Representatives, September 27, 2019, at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-wd/19-0025.pdf.

36 For example, see J. Brian Charles, “States, Cities Add Sweeteners to Attract 'Opportunity Zone' Investors,” Governing, April 17, 2019, at https://www.governing.com/topics/finance/gov -opportunity-zones-extra-incentives.html; and Novogradac, “State Opportunity Zones Legislation,” at https://www.novoco.com/resource-centers/opportunity-zones-resource-center/state-opportunity-zones-legislation.

Congressional Research Service

9

Tax Incentives for Opportunity Zones: In Brief

Coordination of Federal Economic Development Programs with Opportunity Zones In 2018, President Trump issued an executive order that developed the interagency White House Opportunity and Revitalization Council, whose goal was to “encourage public and private investment in urban and economical y distressed areas, including qualified opportunity zones [sic].”37 This council, chaired by the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban

Development, was tasked with assessing actions that each federal agency could take under its existing authority to prioritize or focus federal programs in economical y distressed communities, including qualified OZs, and reduce regulatory and administrative costs that could discourage such public and private investment. Pursuant to the President’s executive order, some agencies have promulgated regulations or issued press releases explaining how they are working toward

these goals.38

Proponents of such activities could argue that federal coordination of benefits could enhance the incentive effects of OZs. Examinations of past federal economic development incentives, such as

the NMTC, have indicated that one federal incentive, alone, might not be sufficient to drive private-sector investment in distressed communities.39 By “stacking” multiple government benefits in qualified OZs, though, economic development assistance could be more successful in driving private and public investment in qualified OZs. Critics of this approach, though, could argue that such coordination could undermine assessments of the OZ tax incentives, and could make the OZ tax incentives appear to be more effective in increasing economic outcomes than

they would otherwise if measured in isolation.

Timeline of Tax Benefits In order to benefit from the 15% step-up in basis for capital gains rolled over into a QOF and held for seven years, investors would have needed to roll over their capital gains into a QOF by the end of calendar year 2019. By doing so, investors would be able to obtain a full seven years holding period needed for the 15% basis adjustment. (Investments made after 2019 can stil

benefit from a 10% step-up in basis.)

Congress could decide that two calendar years (2018 and 2019) were not sufficient time for QOFs to form and raise money from investors, who might have waited to participate in OZ investments

until they conducted more research or reviewed developing regulations. To al ow for more investments to qualify for the 15% step-up in basis, the mandatory recognition of deferred capital gains in IRC 1400Z-2 could be delayed (e.g., to December 31, 2027). Critics of such a proposal, however, could oppose such a policy, citing a concern that the OZ tax incentives largely benefit

investors, rather than low-income communities and their current residents.

37 Executive Order 13853, “Establishing the White House Opportunity and Revitalization Council,” 83 Federal Register 65071, December 18, 2018, at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/12/18/2018 -27515/establishing-the-white-house-opportunity-and-revitalization-council.

38 For example, see U.S. Department of Commerce, “Review of DOC Policy in Opportunity Zones,” 84 Federal Register 45946-45949, September 3, 2019. 39 For example, see p. 34 in U.S. Government Accountability Office, Tax Policy: New Markets Tax Credit Appears to Increase Investm ent by Investors in Low-Incom e Com m unities, but Opportunities Exist to Better Monitor Com pliance , GAO-07-296, January 2007, https://www.gao.gov/new.items/d07296.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

10

Tax Incentives for Opportunity Zones: In Brief

Congressional Oversight Congressional oversight of OZs has focused on how they are designated, their efficacy as a means

to increase investment in low-income areas, and their reporting requirements. Each issue is

discussed below.

Designation of Qualified Opportunity Zones

Some Members of Congress have expressed concern that certain individuals with ties to the Administration could have had an unfair or improper influence on the geographical designation of

certain census tracts as qualified OZs. These reports have been published in various media outlets.40 While engagement and lobbying with state and federal officials on tax incentives are not unusual activities, some Members have raised concern that the qualified OZ designation process could have been conducted in a way “to enrich political supporters or personal friends of senior administration officials.”41 For example, Representative Bil Pascrel wrote a separate letter to

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin requesting a response to the media reports and questions related to meetings held by the Secretary and his staff with certain types of potential stakeholders in OZ investments. Senator Cory Booker, Representative Emmanuel Cleaver, and Representative Ron Kind sent a letter to Acting Treasury Inspector General (IG) Richard Delmar asking that the designation process be investigated.42 The Treasury IG has reportedly accepted that request,

although the exact scope of the investigation has not been publicly disclosed.43

Efficacy of OZs to Improve Economic Conditions of Low -Income Areas

House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Richard E. Neal, Senate Finance Committee Ranking Member Ron Wyden, Former Ways and Means Oversight Subcommittee Chairman John Lewis, and Senator Cory Booker wrote a letter to GAO requesting it to “study the program to

review its effectiveness in spurring investment in low-income areas compared to other federal incentives, zone designations and program compliance.”44 Among several research questions, the request asks GAO to compare OZ tax incentives to other economic development tax incentives, such as the NMTC and the low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC), and analyze the characteristics of census tracts that were eligible but not designated to those that were designated. GAO issued its final report in October 2020 and found that OZs have fewer limits on permissible 40 For example, see Jeff Ernsthausen and Justin Elliott, “One T rump Tax Cut Was Meant to Help the Poor. A Billionaire Ended Up Winning Big,” ProPublica, June 19, 2019, at https://www.propublica.org/article/trump-inc-podcast -one-trump-tax-cut-meant-to-help-the-poor-a-billionaire-ended-up-winning-big; Eric Lipton and Jesse Drucker,

“Symbol of ’80s Greed Stands to Profit From T rump T ax Break for Poor Areas,” NY Times, October 26, 2019, at https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/26/business/michael-milken-trump-opportunity-zones.html; and Jeff Ernsthausen and Justin Elliott, “How a T ax Break to Help the Poor Went to NBA Owner Dan Gilbert,” ProPublica, October 24, 2019, at https://www.propublica.org/article/how-a-tax-break-to-help-the-poor-went -to-nba-owner-dan-gilbert.

41 Senator Cory Booker, “Following Allegations of Misconduct, Booker, Cleaver, Kind Urge T reasury Inspector General for “Complete Review” of T reasury’s Implementation of Opportunity Zones,” press release, October 31, 2019, at https://www.booker.senate.gov/?p=press_release&id=1005 . See also Representative Bill Pascrell, “ Pascrell Assails Mnuchin T reasury Corruption,” press release, October 29, 2019, at https://pascrell.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=4051 . 42 See Letter from Sen. Booker et al. (October 31, 2019). 43 Justine Coleman, “T reasury Watchdog to Investigate T rump Opportunity Zone Program ,” The Hill, January 15, 2020, at https://thehill.com/policy/finance/478521-treasury-watchdog-to-investigate-trump-opportunity-zone-program.

44 House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Richard Neal, “Neal, Wyden, Lewis, Booker Request GAO Study on Opportunity Zone Program,” press release, November 6, 2019, at https://waysandmeans.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/neal-wyden-lewis-booker-request -gao-study-opportunity-zone-program.

Congressional Research Service

11

Tax Incentives for Opportunity Zones: In Brief

project types and controls to limit revenue losses. GAO also found that insufficient data were being collected to evaluate OZ performance. GAO found that addressing the latter concern may

require congressional action.

Related to this issue, the Urban Institute previously published in the Federal Register on May 1, 2019 (hereinafter referred to as the "May 2019 NPRM").16 The May 2019 NPRM provides details about the requirements under Section 1400Z-2 that could be imposed on OZ-related transactions. These proposed requirements could also shape some of the development effects of OZs. Public comments are due by July 1, 2019, and a public hearing is scheduled for July 9, 2019.17

The May 2019 NPRM calls for defining "substantially all" differently in two subsections of the statute. First, under Section 1400Z-2(d)(3)(A)(i)(III), a qualified OZ business is defined, in part, as a trade or business "in which substantially all of the tangible property owned or leased by the taxpayer is qualified opportunity zone business property."18 The May 2019 NPRM says that a trade or business would satisfy the "substantially all" test if at least 70% of the tangible property owned or leased by the trade or business is qualified OZ business property (discussed in more detail, below). Treasury and IRS arrived at the 70% threshold after balancing competing interests: a lower threshold would allow more businesses to benefit from qualifying investments in QOFs while too low of a threshold could dilute the focus of the investments in the communities that OZs were intended to benefit. Second, three different provisions in 1400Z-2(d)(2) require that "during substantially all of the [QOF's] holding period" of any qualified OZ-stock, partnership interest, or business property must be in a qualified OZ. The proposed regulations say that "substantially all" in the holding period context would be defined as 90%.19 The May 2019 NPRM claims that the use of a higher threshold in this context is justified because taxpayers are more easily able to control and time their investments in property, and a lower threshold would, again, reduce the amount of investment in the communities that OZs were intended to benefit.

The May 2019 NPRM also defines the phrase "original use" for the purposes of qualified OZ business property. Under Section 1400Z-2(d)(3)(A)(i)(II), qualified OZ business property is defined in part as tangible trade or business property in which "the original use of such property in the qualified opportunity zone commences with the qualified opportunity fund or the qualified opportunity fund substantially improves the property." The May 2019 NPRM would define "original use" as tangible property that has (1) not been previously placed into service for the purposes of depreciation or amortization, or (2) has not been used in a manner that would allow depreciation or amortization if that person were the property's owner.20

In sum, the proposed rule encourages investments in new tangible property, as opposed to property that a business might have used elsewhere and then moved to business operations within an OZ. The second interpretation, though, allows businesses that lease tangible property to qualify as investments in qualified OZ business property. The May 2019 NPRM notes that some parties were concerned that the original use requirement would not benefit investment in abandoned structures.21 In response, the May 2019 NPRM considers the adoption of a rule that would allow buildings or structures that have been vacant for at least five years prior to being purchased by a QOF or qualified OZ business as satisfying the original use requirement.

The May 2019 NPRM also addresses a number of other questions that could be important to a broad range of OZ transactions, such as

- Investments in unimproved land not used in a trade or business would generally not be considered OZ property.22 This interpretation is intended to prevent QOFs from speculative land buying. Land that is used in a trade or business by a QOF or a qualified OZ business can qualify for OZ tax incentives, though, as long as the land is "substantially improved."23

- Leased tangible property used in a trade or business within an OZ would count towards the requirement that "substantially all" (i.e., 70%) of the tangible property owned or leased by for the purposes of a qualified OZ business.24 This interpretation is intended to increase parity between businesses that choose to purchase tangible property versus lease it.

- A trade or business located on real property straddling (partly inside and outside) a qualified OZ could be eligible as a qualified OZ business if it meets certain criteria. Treasury proposes that if the amount of real property (based on square footage) located within the qualified OZ is substantial as compared to the amount of real property outside of the OZ, and the real property outside of the OZ is contiguous to part or all of the real property within the OZ, then all the property will be deemed to be located within the OZ.25 A similar rule was applied to Empowerment Zones tax incentives.

- There are three safe harbor provisions (plus an ability to demonstrate eligibility based on the particular facts and circumstances) for determining whether a business has derived at least 50% of its total gross income "from the active conduct of such business" within an OZ, for the purposes of being a qualified OZ business. Those criteria are: (1) the hours performed by its employees and independent contractors; (2) the amounts paid by the trade or business for services performed in the qualified OZ by its employees and contractors; or (3) tangible property of the business and the management or operational functions performed for the business.26 Hypotheticals in the May 2019 NPRM illustrate how these criteria apply to a business. These safe harbors could affect the scope of businesses that could benefit from OZ tax incentives.

- QOFs have a one-year grace period to sell assets and reinvest the proceedings into another qualified OZ investment for the purposes of meeting the 90% asset requirement for QOFs.27 This provision would clarify the statutory language in Section 1400Z-2(e)(4)(B) allowing a QOF "a reasonable period of time to reinvest the turn of capital from investments." On the one hand, a longer grace period could provide QOFs with more flexibility to identify and deploy capital to projects with higher returns. On the other hand, a longer grace period could allow QOFs (and their investors) to hold their assets with the goal of earning the basis adjustments or exclusion of gain without actively investing money into OZ communities.

- For investors, the May 2019 NPRM provides details on what events could trigger the inclusion of capital gains under Section 1400Z-2(b)(1). This provision is the benefit of deferring capital gains tax liability on the initial capital gain that was reinvested within 180 days into a QOF. Under the statute, that deferral ends the earlier of: (1) the date on which the qualifying investment is sold or exchanged, or (2) December 31, 2026. In short, any transaction that reduces the taxpayer's direct equity interest in a QOF could trigger a sale or exchange requiring the taxpayer to include their deferred capital gains liability for their personal income tax purposes.28

Other details are provided in the proposed regulations that could be useful for structuring specific OZ-related transactions. A full summary of these provisions is beyond the scope of this report. Treasury also published a request for information in the Federal Register on suggestions for OZ data collection and tracking.29 More regulations could be issued on related issues, but, as of the publication date of this report, no specific timeline has been announced by Treasury or the IRS.

What Economic Effects Can Be Expected?

OZs are an addition to the array of geographically targeted, federal programs and incentives for economic development. Examples of economic development incentives that are administered through the tax code include the NMTC,30 the low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC),31 and the tax credit for the rehabilitation of historic structures.32

Although any one of these tax incentives might not be sufficient to generate a positive investment return from an otherwise unprofitable development project, developers may be able to "stack" the benefits of multiple federal tax incentives (as well as any state and local incentives). The sum of the benefits could make a project located in one area more profitable than alternatives. Studies find that place-based economic development incentives tend to shift investment from one area to another, rather than result in a net increase in aggregate economic activity.33

Comparisons may be made between the NMTC and OZ tax incentives. The OZ tax incentives provide relief from capital gains taxation, thereby directly benefiting owners of capital rather than low-income populations that live in OZs.34 Although the NMTC is an investment credit, it, like the OZ tax incentives, also directly benefits capital owners. The NMTC can be distinguished from the OZ tax incentives in several ways, though. First, Congress has capped the amount of NMTC allocations that the Fund may issue per year ($3.5 billion), thereby making these applications competitive because the demand for NMTC allocations exceeds the supply provided by Congress. In contrast, the maximum amount of tax benefits conferred by the OZ tax incentives are uncapped, much like many tax provisions—if a taxpayer qualifies for the special tax treatment, then they may claim it.

Second, the Fund evaluates NMTC applications based on a set of factors. One factor is the potential impact that the investments supported will have on "community outcomes," including benefits to low-income persons and jobs directly induced by the investments.35 Investments made by QOFs are eligible to benefit a broad range of potential projects, regardless of their potential "community outcomes."36

Third, NMTC recipients are required to adhere to a set of outcome-based reporting and compliance requirements.37 These metrics track the location and type of projects funded by NMTC allocations.38 No such outcome-based requirements are needed for OZ tax incentives.

Fourth, to become eligible for a NMTC allocation, a certified CDE must, among other criteria, have a primary mission of serving or providing investment capital to low-income communities. A governing or advisory board is supposed to hold the CDE accountable to that mission. QOFs are not required to be mission-oriented for the primary purposes of serving low-income communities.

The Urban Institute analyzed the census tracts designated by the CEOs of the states and the District of Columbia, "scoring"“scoring” each against measures of the investment flows they are receiving and the socioeconomic changes they have already experienced.3945 Tracts that were selected by the state'’s respective CEO and designated as QOZs were compared with eligible, nondesignated tracts not selected by the CEO. CEOs in Montana,

DC, Alaska, and Georgia selected areas with the lowest levels of preexisting investment.40 46 Conversely, CEOs in HawaiiHawai , Vermont, Nebraska, and West Virginia selected areas with the

highest levels of preexisting investment. Additionally

Designated tracksAdditional y the researchers found

Designated [OZ] tracks [sic] do have lower incomes, higher poverty rates, and higher unemployment rates than eligible nondesignated tracts (and the US overall average, which is as expected given eligibility criteria). Housing conditions trend in similar ways, with lower home values, rents, and homeownership rates. The designated tracts are also notably less white and more Hispanic and black than eligible nondesignated tracts. Age less white and more Hispanic and black than eligible no ndesignated tracts. Age compositions are comparable. Education levels are somewhat lower among designated tracts than eligible nondesignated tracts.... In terms of this program, there appears to be no targeting on the basis of urbanization.47

Some Members of Congress have also introduced bil s that are intended to limit the benefits of OZ tax incentives. For example, H.R. 5042 would modify the eligibility criteria for qualified OZs and replace existing OZs that do not conform to those criteria with new designations. H.R. 5042

also retroactively prohibits (effective as if enacted as part of P.L. 115-97) qualified OZ investments in self-storage property, stadiums, and residential rental property unless 50% or more of the residential units of such property are both rent-restricted and occupied by individuals

whose income is 50% or less of area median income.

Data and Reporting Requirements on Beneficial Investors and Projects

Testimony before some committees has reinforced suggestions that Congress lacks adequate information for oversight of OZ tax benefits and that further data-reporting requirements are needed.48 QOFs are not required by statute to provide periodic public reports on the locations of their investments or economic impacts of those investments on low -income communities. The ability of the IRS and Treasury to disclose such information is currently limited by general

provisions protecting taxpayer confidentiality absent the taxpayer’s consent.49 However, Treasury or Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) economists could conduct an in-house study measuring the effects of the tax provision without publicly disclosing confidential taxpayer data, and Congress

could amend taxpayer confidentiality rules to permit disclosure.

45 Brett T heodos, Brady Meixell, and Carl Hedman, Did States Maximize Their Opportunity Zone Selections? Urban Institute, May 21, 2018, at https://www.urban.org/research/publication/did-states-maximize-their-opportunity-zone-selections. State-by-state comparisons are available in a spreadsheet on the linked page.

46 Ibid., at 4. 47 Ibid., at 8. 48 For example, see U.S. Congress, House Committee on Small Business, Subcommittee on Economic Growth, T ax, and Capital Access, Can Opportunity Zones Address Concerns in the Sm all Business Econom y? 116th Cong., October 17, 2019, at https://smallbusiness.house.gov/calendar/eventsingle.aspx?Ev entID=2901. All of the witnesses in that hearing recommended additional data collection.

49 See IRC Section 6103.

Congressional Research Service

12

Tax Incentives for Opportunity Zones: In Brief

Under its existing authority, the IRS has sought public input on ways to modify the Form 8996, which is filed annual y by taxpayers that have self-elected QOF status, to increase the amount of data collected on OZ investments.50 Starting with the 2019 tax year (2020 tax filing season), the IRS now asks for more data on the value and location of qualified OZ property owned or leased

by the QOF, as wel as any qualified OZ stock or partnership interests.51

Currently, data and metrics on investment in OZs are provided by nongovernmental, private industry sources. For example, Novogradac, an accounting and consulting firm that focuses on economic development tax incentives, reported that a total of 580 QOFs nationwide had raised

$12.05 bil ion in equity as of September 1, 2020.52 The names, contact information, and investment focus area of QOFs that elected to provide such information are also listed on Novogradac’s website, as wel as other third-party sites.53 Some of these third-party data sources

also indicate the minimum investment required for an investor to participate in a particular QOF.

Several bil s introduced in the 116th Congress are intended to promote oversight and transparency of OZs. For example, S. 1344/H.R. 2593 would require the Department of the Treasury to collect data and report to Congress on investments held by QOFs. These bil s would also require the Treasury to make certain information regarding these investments publicly available.