Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement

Changes from April 8, 2019 to November 20, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement

Contents

- Introduction

- Provisions of USMCA

- Expansion of Market Access Provisions

- Improved Agricultural Trading Regime

- U.S. Agricultural Trade with Canada and Mexico

- U.S. Agricultural Exports to Canada and Mexico

- U.S. Imports from Canada and Mexico

- Economic Effects of NAFTA versus USMCA

- U.S. Agricultural Stakeholders on USMCA

- Outlook for Proposed USMCA

Tables

- Table 1. Chronology of North American Agricultural Market Liberalization

- Table 2. Proposed Canadian Market Access for U.S. Agricultural Products Under USMCA

- Table 3. Major U.S. Agriculture Exports to Canada

- Table 4. Major U.S. Agriculture Exports to Mexico

- Table 5. Major U.S. Agriculture Imports from Canada and Mexico

Summary

On September 30, 2018, the Trump Administration announced the conclusion of the renegotiations of the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the proposed United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). If approved by Congress and ratified by Canada and Mexico, USMCA would modify and possibly replace NAFTA, which entered into force January 1, 1994. NAFTA provisions are structured as three separate bilateral agreements: one between Canada and the United States, a second between Mexico and the United States, and a third between Canada and Mexico.

Under NAFTA, bilateral agricultural trade between the United States and Mexico was liberalized over a transition period of 14 years beginning in 1994. NAFTA provisions on agricultural trade between Canada and the United States are based on commitments under the Canada-U.S. Trade Agreement (CUSTA), which granted full market access for most agricultural products with the exception of certain products. The agricultural exceptions under NAFTA include Canadian imports from the United States of dairy products, poultry, eggs, and margarine and U.S. imports from Canada of dairy products, peanuts, peanut butter, cotton, sugar, and sugar-containing products.

The proposed USMCA would expand market access for U.S. exports of dairy, poultry, and eggs to Canada and enhance NAFTA's Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) provisions. It would also include new provisions for trade in agricultural biotechnology products, add provisions governing Geographical Indications (GIs), addAgricultural Provisions of the

November 20, 2020

U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement

Anita Regmi

The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), a comprehensive trade agreement

Specialist in Agricultural

among the three countries, entered into force on July 1, 2020. USMCA replaced the North

Policy

American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which had been in effect since 1994. NAFTA

contributed to notable increases in trade in agricultural products within North America. Under NAFTA, Mexico eliminated all tariffs and quotas that formerly governed agricultural imports

from the United States over a period of 14 years beginning in 1994. Canada and the United States

granted each other’s agricultural exports full market access, save for specific exceptions. The agricultural exceptions under NAFTA included Canadian imports of U.S. dairy products, poultry, eggs, and margarine a nd U.S. imports of Canadian dairy products, peanuts, peanut butter, cotton, sugar, and sugar-containing products. Under NAFTA, Canada has been the United

States’ top agricultural export market since 2002, and Mexico has in most years ranked second.

USMCA provides for no further market access changes for bilateral agricultural trade between the United States and Mexico. USMCA expands market access for U.S. exports of dairy, most poultry products, and eggs to Canada. It is likely to lead to lower U.S. access for chicken meat relative to projected access under NAFTA provisions. Likewise, USMCA expands access for Canadian dairy, peanuts, peanut butter, cotton, sugar, and sugar-containing exports to the United States.

USMCA includes new provisions to govern trade in agricultural biotechnology products; limits the use of Geographical Indications (GIs) to block exports of products labeled in certain ways; adds confidentiality protection for proprietary food formulas, and requirerequires USMCA countries to apply the same regulatory treatment to imported alcoholic beverages and wheat as those that govern their domestic products. Some of these provisions could serve as models for U.S. proposals in other future trade negotiations.

Canada and Mexico, the leading suppliers of and destinations for U.S. agricultural products, jointly accounted for 29% of all U.S. agricultural exports and 40% of total imports in 2019. Consumer-oriented foods, such as meats, dairy, fruit, vegetables, and prepared and packaged foods, have increasingly gained share of trade in the region. Since the implementation of NAFTA, U.S. bilateral trade with Canada and Mexico has substantially increased, and according to several estimates, will likely grow under USMCA. Studies indicate modest gains in regional trade under USMCA, with the greatest potential for gains from provisions to modernize and integrate customs procedures to reduce trade costs and border inefficiencies. A study indicates gains to be greater for Canada than for the other two countries, while another indicates possible losses for small fruit and vegetable producers in the State of Georgia.

As it oversees the implementation of USMCA, Congress may monitor Canada’s actions to expand market access for U.S. dairy, poultry meat, and eggs. Congress may also examine progress in implementing the various nontariff provisions that the three countries agreed to under the USMCA, particularly efforts to harmonize sanitary and phytosanitary rules and to establish a regulatory framework to govern trade in products created with agricultural biotechnology.

USMCA has expanded access to the U.S. market for Canadian dairy, sugar, and products containing sugar, and Congress may examine how this improved access to the U.S. market affects these sectors and the U.S. rural economy. It may also evaluate the effects of supply-chain disruptions due to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and any impacts on efforts toward greater integration of the North American market for agricultural products.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 4 link to page 4 link to page 6 link to page 6 link to page 6 link to page 10 link to page 12 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 18 link to page 21 link to page 22 link to page 9 link to page 15 link to page 17 link to page 20 link to page 5 link to page 8 link to page 11 link to page 16 link to page 18 link to page 19 link to page 21 link to page 23 Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement

Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Agricultural Trade Liberalization in North America .............................................................. 1 Provisions of USMCA ..................................................................................................... 3

Expansion of Market Access Provisions ........................................................................ 3

Expanded Access for U.S. Imports to Canada ........................................................... 3 Expanded Access for Canadian Imports to the United States ....................................... 7

Modifications to Agricultural Trading Regime ............................................................... 9

U.S. Agricultural Trade with Canada and Mexico ............................................................... 11

U.S. Agricultural Exports to Canada and Mexico .......................................................... 12

U.S. Imports from Canada and Mexico ....................................................................... 15

USMCA’s Potential Trade Effects Beyond NAFTA ............................................................ 18 Issues for Congress ....................................................................................................... 19

Figures

Figure 1. U.S. Chicken Meat Access To Canada Under NAFTA, USMCA and CPTPP............... 6 Figure 2. U.S. Agricultural Trade With Canada and Mexico ................................................. 12 Figure 3. U.S. Dairy and Poultry Product Exports To Canada ............................................... 14 Figure 4. U.S. Imports of Canadian Dairy, Sugar, and Sugar-Containing Products ................... 17

Tables Table 1. Chronology of North American Agricultural Market Liberalization ............................. 2 Table 2. Canadian Market Access for U.S. Agricultural Imports Under USMCA ....................... 5 Table 3. U.S. Market Access for Canadian Agricultural Products Under USMCA...................... 8 Table 4. Major U.S. Agricultural Exports to Canada ........................................................... 13 Table 5. Major U.S. Agricultural Exports to Mexico ........................................................... 15 Table 6. Major U.S. Agricultural Imports from Canada ....................................................... 16 Table 7. Major U.S. Agricultural Imports from Mexico ....................................................... 18

Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 20

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement

Introduction The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), a comprehensive trade agreement among the three countries, entered into force on July 1, 2020.1 USMCA replaced the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which had been in effect since 1994 (P.L. 103-182). USMCA continues the liberalization of agricultural trade within North America, which has been under way for more than three decades. It also addresses a number of trade-related issues that

NAFTA did not consider. This report provides a brief history of agricultural trade agreements within North America, explores the changes made in the USMCA, and considers how the new

agreement is likely to affect the flow of trade in agricultural commodities and food products.

Agricultural Trade Liberalization in North America The Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (CUSTA), which went into effect on January 1, 1989, began the process of agricultural trade liberalization within North America. The agreement

provided for the elimination of almost al tariffs on agricultural products traded between the two countries over a 10-year period, although each country retained the right to impose temporary duties on certain fresh fruits and vegetables to protect against import surges from the other country. The agreement also exempted full liberalization of meat trade between the two countries, and did not include provisions to prevent Canada from using discriminatory marketing and

pricing measures for U.S. wine and distil ed spirits. It barred the United States from imposing import restrictions on Canadian products containing less than 10% sugar by weight and provided for the elimination of certain Canadian grain transportation subsidies. Most U.S. and Canadian nontariff barriers and agricultural support policies were unchanged by the agreement.2

NAFTA was structured as three separate agreements, one between Canada and the United States, one between the United States and Mexico, and the third between Mexico and Canada. The U.S.-Canada portion of NAFTA incorporated the agricultural provisions of CUSTA. NAFTA continued to exempt certain products from market liberalization, includingas those that govern their domestic products.

Since 2002, Canada has been the United States' top agricultural export market, and Mexico was the second-largest export market until 2010, when it became the third-largest market as China became the second-largest agricultural export market for the United States. U.S. agricultural exporters are thus keen to keep and grow the existing export market in North America. If the United States were to potentially withdraw from NAFTA, as mentioned several times by President Trump, U.S. agricultural exporters could potentially lose at least a portion of their market share in Canada and Mexico if the proposed USMCA does not enter into force. If the United States withdraws from NAFTA, U.S. agricultural exports to Canada and Mexico would likely face World Trade Organization (WTO) most-favored-nation tariffs—the highest rate a country applies to WTO member countries. These tariffs are much higher than the zero tariffs that U.S. exporters currently enjoy under NAFTA for most agricultural exports to Canada and Mexico.

The proposed USMCA would need to be approved by the U.S. Congress and ratified by Canada and Mexico before it could enter into force. Some Members of Congress have voiced concerns about issues such as labor provisions and intellectual property rights protection of pharmaceuticals. Other Members have indicated that an anticipated assessment by the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) will be key to their decisions on whether to support the agreement. Canada, Mexico, and some Members of Congress have expressed concern about other ongoing trade issues with Canada and Mexico, such as antidumping issues related to seasonal produce imports and the recent U.S. imposition of a 25% duty on all steel imports and a 10% duty on all aluminum imports. Both the Canadian and the Mexican governments have stated that USMCA ratification hinges in large part upon the Trump Administration lifting the Section 232 tariffs on imported steel and aluminum. Similarly, some Members of Congress have stated that the Administration should lift tariffs on steel and aluminum imports in order to secure the elimination of retaliatory tariffs on agricultural products before Congress would consider legislation to implement USMCA.

Introduction

Since 2002, Canada has been the United States' top agricultural export market. Mexico was the second-largest export market until 2010, when China displaced Mexico as the second-leading market with Mexico becoming the third-largest U.S. agricultural export market. In FY2018, U.S. agricultural exports totaled $143 billion, of which Canada and Mexico jointly accounted for about 27%. USDA's Economic Research Service estimates that in 2017 each dollar of U.S. agricultural exports stimulated an additional $1.30 in business activity in the United States. That same year, U.S. agricultural exports generated an estimated 1,161,000 full-time civilian jobs, including 795,000 jobs outside the farm sector.1 U.S. agricultural exports to Canada and Mexico are an important part of the U.S. economy, and the growth of these markets is partly the result of the North American market liberalization under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).2

On September 30, 2018, the Trump Administration announced an agreement with Canada and Mexico for a U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) that would possibly replace NAFTA. NAFTA entered into force on January 1, 1994, following the passage of the implementing legislation by Congress (P.L. 103-182).3 NAFTA was structured as three separate bilateral agreements: one between Canada and the United States, a second between Mexico and the United States, and a third between Canada and Mexico.4

Provisions of the Canada-U.S. Trade Agreement (CUSTA), which went into effect on January 1, 1989, continued to apply under NAFTA (see Table 1). CUSTA opened up a 10-year period for tariff elimination and agricultural market integration between the two countries. The agricultural provisions agreed upon for CUSTA remained in force as provisions of the new NAFTA agreement. While tariffs were phased out for almost all agricultural products, NAFTA (in accordance with the original CUSTA provisions) exempted certain products from market liberalization. These exemptions included U.S. imports from Canada of U.S. imports from Canada of

dairy products, peanuts, peanut butter, cotton, sugar, and sugar-containing products and Canadian imports from the United States of dairy products, poultry, eggs, and margarine. Canada’s imports of these products were limited by tariff-rate quotas (TRQs), which provided for a volume of

imports to enter with no tariff but assessed high tariffs on imports beyond the quota amount.

The United States and Mexico agreement under NAFTA did not exclude any agricultural products from trade liberalization. Numerous restrictions on bilateral agricultural trade were eliminated immediately upon NAFTA’s implementation, while others were phased out over a 14-year period. Remaining trade restrictions on the last handful of agricultural commodities (such as U.S. exports

to Mexico of corn, dry edible beans, and nonfat dry milk and Mexican exports to the United States of sugar, cucumbers, orange juice, and sprouting broccoli) were removed upon the completion of the transition period in 2008.3 Table 1 provides a chronology of measures to

liberalize agricultural trade within North America.

1 For more information, see CRS Report R44981, The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), by M. Angeles Villarreal and Ian F. Fergusson.

2 CRS Report 88-506, The Effect of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement on U.S. Industries, by Arlene Wilson and Carl E. Behrens, July 22, 1988. T his document is available to congressional clients upon request. 3 Sugar trade between the United States and Mexico is governed by antidumping duty and countervailing duty suspension agreements that imposed several limitations on this trade beginning in December 2014 and subsequently

Congressional Research Service

1

Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement

Table 1. Chronology of North American Agricultural Market Liberalization

January 1989

Canada-United States Trade Agreement imports from the United States of dairy products, poultry, eggs, and margarine. Canada liberalized its agricultural sector under NAFTA, but liberalization did not include its dairy, poultry, and egg product sectors, which continued to be governed by domestic supply management policies and are protected from imports by high over-quota tariffs.

Quotas that once governed bilateral trade in these commodities were redefined, under NAFTA, as tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) to comply with the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture (URAA), which took effect on January 1, 1995.5 A TRQ is a quota for a volume of imports at a favorable tariff rate, which was set at zero under NAFTA. Imports beyond the quota volume face higher over-quota tariff rates.

|

January 1989 |

Canada-United States Trade Agreement implemented. |

|

January 1994 |

implemented.

January 1994

NAFTA enters force, tariffs eliminated |

U.S. tariffs on Mexican corn, sorghum, | |

Mexican tariffs on U.S. sorghum, | |

|

January 1998 |

Completion of 10-year transition period between Canada and the United States. |

Remaining Canadian tariffs on U.S. products eliminated, | |

Remaining U.S. tariffs on Canadian products removed, | |

U.S. tariffs eliminated | |

Among others, Mexican tariffs eliminated on imports | |

|

January 2003 |

|

completed.

Among others, U.S. tariffs eliminated | |

Among others, Mexican tariffs eliminated on imports | |

|

January 2008 |

Completion of 14-year transition period under NAFTA between Mexico and the United States. In 2008, the remaining |

U.S. tariffs eliminated | |

Mexican tariffs eliminated | |

|

May 2017 |

May 2017

Trump Administration |

|

August 2017 |

Renegotiation talks begin. |

|

September 30, 2018 |

30, 2018

Trump Administration |

|

November 30, 2018 |

President Trump and presidents of Canada and Mexico sign the proposed USMCA.

|

April | 2019

U.S. International Trade Commission submits report assessing |

Source: For NAFTA, S. Zahniser and J. Link, Effects of North American Free Trade Agreement on Agriculture .

January 29, 2020

USMCA implementing legislation becomes law (P.L. 116-113).

July 1, 2020

USMCA enters into force.

Source: Steven Zahniser and John Link, Effects of North American Free Trade Agreement on Agriculture and the Rural Economy, WRS-02-1, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Economic Research Service (ERS), July 2002; Henrich Brunke and Daniel A. Sumner, “Economy, Economic Research Service, WRS-02-1, July 2002; H. Brunke and D. A. Sumner, "Role of NAFTA in California Agriculture: A Brief Review," University of California, AIC Issues Brief# 21, February 2003; S. Zahniser and Z. Review,” AIC Issues Brief, no. 21, University of California, February 2003; Steven Zahniser and Zachary Crago, NAFTA at 15: Building on Free Trade, USDA Report WRS-09-03WRS-09-03, USDA, ERS, March 2009; and CRS Report R44981, NAFTA Renegotiation and the ProposedThe United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement Agreement (USMCA), by M. Angeles Villarreal Vil arreal and Ian F. Fergusson.

revised in June 2017. See CRS In Focus IF10693, Am ended Sugar Agreem ents Recast U.S.-Mexico Trade, by Mark A. McMinimy.

Congressional Research Service

2

link to page 8 Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement

In addition to directly improving market access, NAFTA addressed other issues related to the integration of the North American agricultural market. These included provisions on rules of origin to exclude products original y shipped from other countries from benefiting from NAFTA preferential treatment; the development, adoption, and enforcement of sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) regulations in the region; and a commitment by the United States and Mexico that when either country applies marketing, grade, or quality standards to a domestic product destined for

processing, it wil provide no less favorable treatment for like products imported for processing. 4

Provisions of USMCA USMCA expands upon the agricultural provisions of NAFTA by further reducing market access

barriers and strengthening provisions to facilitate trade in North America.

Expansion of Market Access Provisions Al food and agricultural products that had zero tariffs under NAFTA remain at zero under USMCA. Regarding U.S.-Mexico trade in agricultural products, under NAFTA, the two countries

eliminated al the tariffs and quotas that formerly governed agricultural imports, and USMCA

provides for no further market access changes for agricultural trade between the two countries.

Regarding trade between the United States and Canada, the two countries are providing greater

access to most products that faced restrictions under NAFTA. This includes Canada expanding its access to imports of U.S. dairy products, poultry, eggs, and margarine and the United States granting access to imports of Canadian dairy products, peanuts, peanut butter, cotton, sugar, and

sugar-containing products.

Expanded Access for U.S. Imports to Canada

Canada has historical y employed a supply management regime that included TRQs on imports of dairy and poultry. Canada’s TRQs under NAFTA appear to have restricted imports of some dairy, poultry, and egg products, as the imported volumes for some of these products regularly equaled or exceeded their set quota limits.5 Under USMCA, Canada is changing its TRQs to expand access for U.S. products. Table 2 summarizes the changes in the market access regime for U.S.

agricultural exports to Canada.

U.S. Dairy Market Access Under USMCA

Canada’s import restrictions on U.S. dairy products were a high-profile issue for the United States in the USMCA negotiations, so it is noteworthy that under USMCA, Canada agreed to reduce certain barriers to U.S. dairy exports. For one, Canada has agreed to make changes to its milk

pricing system, which has been accused of setting low prices for Canadian skim milk solids and thereby undercutting U.S. exports. Effective January 1, 2021, Canada has agreed to eliminate its 4 For more information, see CRS Report R44875, The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and U.S. Agriculture, by Renée Johnson.

5 Richard Barichello, “A Review of T ariff Rate Quota Administration in Canadian Agriculture,” Agricultural and Resource Econom ics Review, vol. 29, no. 1 (April 2000), pp. 103 -114; personal communication with Richard Barichello, March 18, 2019; World T rade Organization (WT O), T ariff-Rate Quota notification by Canada, G/AG/N/CAN/128, March 7, 2019; Anastasie Hacault, “T he Impact of Market Access Reforms on the Canadian Dairy Industry,” thesis submitted to the University of Manitoba, 2011, at http://www.cdc-ccl.gc.ca/CDC/userfiles/file/Hacault%20T hesis.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

3

link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 8 Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement

Class 7 milk price (which includes skim milk solids and is designated as Class 6 in Ontario) and wil henceforth set its price for skim milk solids based on a formula that takes into account the U.S. nonfat dry milk price.6 In the future, the United States and Canada have agreed to notify each other if either introduces a new milk class price or changes an existing price for a class of

milk products.

Canada has also converted its dairy TRQs under NAFTA, which were available to al World Trade Organization (WTO) members, to U.S.-specific quotas. Under USMCA, Canada has agreed to maintain its dairy supply management system, but the TRQs are to be increased each year for

U.S. exports of milk, cheese, cream, skim milk powder, condensed milk, yogurt, and several other dairy categories (see Table 2). U.S. dairy exports to Canada is to continue to face zero in-quota tariffs, as under NAFTA. Exports over set quota limits are to continue to face tariffs as high as 200% to 300%.7 While WTO TRQs are to remain available to U.S. dairy product exporters, the

16F

new TRQs under USMCA are to provide additional access to U.S. dairy products into Canada.

USMCA includes provisions on transparency for the implementation of TRQs. These include requirements to provide advance notice of changes to the quotas and to make public the details of quota utilization rates so that exporters are able to monitor the extent to which the quotas are

fil ed. USMCA also includes a requirement that the United States and Canada meet five years after the implementation of the agreement—and every two years after that—to determine whether

to modify the dairy provisions of the agreement.

U.S. Poultry Market Access Under USMCA

Canada replaced its NAFTA market access commitments for U.S. poultry and eggs with new

USMCA TRQs. Imports of U.S. poultry products over set quota limits may face tariffs as high as almost 400%.8 Under USMCA, Canada’s TRQ for imports of U.S. eggs is to be phased over six

F

equal instal ments, reaching 10 mil ion dozen by 2025 and then increasing by 1% per year for the following 10 years. The annual TRQs for turkey and broiler hatching eggs and chicks are set by

formulas based on Canadian production (see Table 2).

For chicken meat, the duty-free quota under USMCA starts at 47,000 metric tons per year and

expands to 57,000 metric tons in 2025. It then is to continue to increase by 1% per year for the next 10 years (Table 2). The United States also has access to Canada’s WTO chicken meat quota

of 39,844 metric tons that is available to imports from al origins. 9

17F

6 U.S. exports are for nonfat dry milk, defined by U.S. standards and regulations, while skim milk powder is defined by the Codex Alim entarius, an international agreement on food standards. Nonfat dry milk has protein content requirements and does not include food additives. T he Codex standard allows skim milk powder to have a lower protein content than that required by the U.S. standard and can contain food additives. All U.S. nonfat dry milk meet the Codex skim milk powder requirement but all skim milk powder may not meet the U.S. nonfat dry milk standard. See Phil T ong, “Nonfat Dried Milk and Skim Milk Powder –All T he Same or Different?” ADPI Intelligence, vol. 5, issue 1, American Dairy Products Institute, 2017. 7 WT O, “Canada T rade Policy Review: Report by T he Secretariat,” T able 3.5, WT /T PR/S/314/Rev.1, September 30, 2015, at https://docsonline.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/WT /T PR/S314R1.pdf&Open=True; and USDA, FAS, “Canada: Dairy and Products,” Annual GAIN Report Number: CA18057 , October 25, 2018. 8 For poultry over-quota tariff rates, see WT O, “Canada T rade Policy Review: Report by T he Secretariat,” T able 3.6, WT /T PR/S/314/Rev.1, September 30, 2015, at https://docsonline.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/WT /T PR/S314R1.pdf&Open=True. 9 Office of the U.S. T rade Representative (UST R), Agreement Between the United States of America, the United Mexican States, and Canada T ext, Signed November 30, 2018 , https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/united-states-mexico-canada-agreement/agreement-between.

Congressional Research Service

4

link to page 9 Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement

Table 2. Canadian Market Access for U.S. Agricultural Imports Under USMCA

Tariff Rate Quotas

(TRQs)

Tariff Rate, %

NAFTA commitments continue: Tariffs eliminated for

0

almost al agricultural products under NAFTA

NAFTA liberalization exemption: Dairy and poultry

TRQs opened under

0 in-quota; WTO

imports into Canada

WTO commitments

MFN over-quota

Dairy, U.S.-specific USMCA TRQs, in addition to TRQs under WTO

Fluid milk TRQ begins at 8,333 MT and increases by 1% each

50,000 MT by August

0 in-quota; WTO

year for 13 years after year 6

2024, 56,905 MT by

MFN over-quota

August 2036

Skim milk powder TRQ begins at 1,250 MT and increases by

7,500 MT by August

0 in-quota; WTO

1% each year for 13 years after year 6

2024

MFN over-quota

Cheese TRQ (50% is for industrial use) begins at 2,084 MT

12,500 MT by January

0 in-quota; WTO

and increases by 1% each year for 13 years after year 6

2025

MFN over-quota

Cream TRQ begins at 1,750 MT and increases by 1% each

10,500 MT by August

0 in-quota; WTO

year for 13 years after year 6

2024

MFN over-quota

Whey TRQ begins at 689 MT and increases by 1% each year

4,135 MT by August

0 after year August

after year 6, until year 10

2024

2028

Other dairy products (butter and cream powder,

15,365 MT by August

0 in-quota; WTO

concentrated and condensed milk, yogurt and buttermilk,

2024 for butter and

MFN over quota

powdered buttermilk, ice cream, natural milk constituents,

cream powder, and

Margarine, 0 starting

other dairy and margarine) begins at 2,561 MT and increases

January 2025 for the rest

January 2025

by 1% each year for 13 years after year 6

Poultry products, new USMCA TRQs

Chicken meat, to increase by 1% each year for 10 years after

47,000 MT in year one,

0 in-quota; WTO

year 6

reaching 57,000 MT by

MFN over-quota

January 2025

Turkey meat, after 2029, Canada may restrict TRQ size if it

≥ 3.5% of Canada’s

0 in-quota; WTO

exceeds 3.5% of that year’s production level by 1,000 MT

previous year’s domestic

MFN over-quota

production

Eggs and products (eggs and egg-equivalent), to increase by

1.67 mil ion dozen in year

0 in-quota; WTO

1% for 10 years after year 6

one, reaching 10 mil ion

MFN over-quota

dozen by January 2025

Broiler hatching eggs and chick products

≥ 21.1% of Canada’s

0 in-quota, WTO

domestic production for

MFN over-quota

that year

Source: Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR), “Agreement Between the United States of America, the United Mexican States, and Canada 7/1/20 Text,” accessed November 2020, at https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/united-states-mexico-canada-agreement/agreement-between; and USDA GAIN Report Number:CA0125, 2000, at https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gainfiles/200008/30677853.pdf. Notes: The TRQs for turkey meat and broiler hatching eggs and chicks are based on anticipated current-year production or World Trade Organization (WTO) commitment volume, whichever is greater. MT = metric tons, MFN = Most Favored Nation. MFN tariffs are levied in a nondiscriminatory manner by WTO member countries on al imports excepting imports from countries with a preferential trade agreement when a lower rate of tariff may be applied.

The sum of the USMCA and WTO quotas is lower than the total quota that was available to U.S. chicken meat under NAFTA (Figure 1), which was set at 7.5% of Canada’s estimated production

Congressional Research Service

5

Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement

level in the previous year. For example, the USMCA full-year quota for 2020 would have been 88,300 metric tons10 compared with an estimated quota of 99,630 metric tons under NAFTA. 11

18F

T

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to a reduction in Canada’s production of chicken meat in 2020. This would have led to a reduction in the NAFTA quota for 2021 (estimated at 96,750 metric tons), but it does not affect the USMCA quota of 88,800 metric

tons.12

Figure 1. U.S. Chicken Meat Access To Canada Under NAFTA, USMCA and CPTPP

After Ful Implementation (Sixth Year) of USMCA in 2025

Thousand Metric Tons

Estimated U.S. Access under

140

NAFTA provisions

120

CPTPP-global TRQ

24.0

26.5

U.S. not a CPTPP member

100

80

USMCA

57.0

63.0 U.S.-specific

60

U.S. accessunder USMCA

40

WTO-global

20

39.8

0

2025

2026

2027

2028

2029

2030

2031

2032

2033

2034

2035

Source: Canada’s Commitments under World Trade Organization (WTO), North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). NAFTA’s estimated quota is CRS calculation as a 7.5% of Canada’s previous year’s chicken meat production, which was projected with an equation estimated using Canada’s chicken meat production from 2007 to 2019 from USDA’s Production, Supply, and Demand database, at https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/app/index.html#/app/advQuery. Note: TRQ = Tariff-rate quota.

Canada has also al ocated a global TRQ for chicken meat under the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which entered into force for Canada on

December 30, 2018.13 Given the geographic disadvantage of most CPTPP member countries,14

10 Note that from January-June 2020, Canada’s NAFT A T RQ was effective and USMCA T RQs became effective only for July-December 2020. Given the two different import regimes, total T RQ available for U.S. chicken meat exports to Canada in 2020 was 91,900 metric tons—less than the 99,630 metric tons estimated for NAFT A. See, USDA, FAS, “Canada: Poultry and Products Annual,” GAIN Report Number: CA2020-0078, August 26, 2020. 11 T he 2020 quota is calculated as 7.5% of the 1,328,900 metric tons of chicken meat Canada produced in 2019. USDA, FAS, “Canada: Poultry and Products Annual,” GAIN Report Number: CA2020-0078, August 26, 2020. 12 Ibid. 13 Government of Canada, “ About the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for T rans-Pacific Partnership,” accessed October 2020, at https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/cptpp-ptpgp/backgrounder-document_information.aspx?lang=eng#:~:text=T he%20CPT PP%20entered%20into%20force,Vietnam%20on%20January%2014%2C%202019.

14 As of October 2020, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for T rans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) has been ratified by Australia, Canada, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, and Vietnam. Other signatories to the CPT PP include Brunei, Chile, Malaysia, Peru, and Singapore. Mexico and Peru are net importers of poultry products.

Congressional Research Service

6

link to page 9 link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 11 Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement

these countries are unlikely to fil Canada’s CPTPP quota for chicken meat. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) attaché in Canada reports that Chile could ship chicken meat to Canada under the CPTPP TRQ, but Chile has not yet ratified the agreement and no trade has occurred under this TRQ.15 If the CPTPP TRQ is added to the USMCA TRQ, market access for U.S. chicken meat into Canada could possibly exceed the volume that would have been permitted

under NAFTA (Figure 1.)

Expanded Access for Canadian Imports to the United States

The United States, in turn, agreed to improve access for Canadian dairy products, sugar, peanuts, peanut butter, and cotton. The United States agreed to increase TRQs for Canadian dairy, sugar, and sugar-containing products (Table 3). The United States is phasing out the tariffs on cotton, peanut, and peanut butter imports from Canada, and agreed to eliminate these tariffs on January 1,

2025.16

Canadian Dairy Product Access Under USMCA

Under USMCA, the United States is providing Canada-specific TRQs for dairy products (Table 3). In addition to these quotas, Canada may also have access to other existing dairy quotas that the United States provides to al foreign suppliers under its WTO commitments.17 Canada-

specific access includes a set volume of imports that increase up to 2025, and then increase 1% each year for 13 more years. The United States has expanded access for Canadian ice cream, other creams, milk beverages, skim milk powder, butter, cream powder, cheese, whole milk powder, dried yogurt, whey, other milk components, concentrated milk, and various other dairy products (Table 3). Imports of Canadian dairy products within the quotas face zero duties, while

imports over the set quota volumes are to be levied duties that can exceed 100% for some

products.18

Canadian Sugar and Sugar-Containing Product Market Access Under USMCA

Under USMCA, the United States is providing access each year to 9,600 MT of refined sugar processed wholly from Canadian sugar beets under a new Canada-specific TRQ. If the Secretary

of Agriculture makes a determination to increase the refined sugar TRQ under U.S. WTO commitments, 20% of the additional WTO quota volume wil be reserved for Canadian sugar.19 The in-quota tariff for al sugar imports is zero, and the over-quota tariff can be close to 90% for

some products.20

15 USDA, FAS, “Canada: Poultry and Products Annual,” GAIN Report Number: CA2020-0078, August 26, 2020. 16 UST R, Agreement Between the United States of America, the United Mexican States, and Canada 7/1/20 T ext , National T reatment and Market Access For Goods, T ariff Schedule of the United States, General Notes, Chapter 2, Annex 2-B-6, accessed October 2020, at https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/united-states-mexico-canada-agreement/agreement -between. 17 Ibid., Appendix 2, T ariff Schedule of the United States – T ariff Rate Quotas. 18 World Integrated T rade Solution (WIT S), T RAINS Ad Valorem Equivalent data for 2018, accessed November 2020. 19 UST R, Agreement Between the United States of America, the United Mexican States, and Canada 7/1/20 T ext , Chapter 2, National T reatment and Market Access For Goods, T ariff Schedule of the United States, T ariff Rate Quotas, T RQ-US9: Sugar, accessed October 2020, at https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/united-states-mexico-canada-agreement/agreement -between. 20 WIT S, T RAINS Ad Valorem Equivalent data for 2018, accessed November 2020.

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 11 Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement

Table 3. U.S. Market Access for Canadianand Ian F. Fergusson.

The United States and Mexico agreement under NAFTA did not exclude any agricultural products from trade liberalization. Numerous restrictions on bilateral agricultural trade were eliminated immediately upon NAFTA's implementation, while others were phased out over a 14-year period. Remaining trade restrictions on the last handful of agricultural commodities (such as U.S. exports to Mexico of corn, dry edible beans, and nonfat dry milk and Mexican exports to the United States of sugar, cucumbers, orange juice, and sprouting broccoli) were removed upon the completion of the transition period in 2008.6 Under NAFTA, Mexico eliminated all the tariffs and quotas that formerly governed agricultural imports from the United States.

In addition to directly improving market access, NAFTA set guidance and standards on other policies and regulations that facilitated the integration of the North American agricultural market. For example, NAFTA included provisions for rules of origin, intellectual property rights, foreign investment, and dispute resolution. NAFTA's sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) provisions made a significant contribution toward the expansion of agricultural trade by harmonizing regulations and facilitating trade.7 Because NAFTA entered into force before URAA, NAFTA's SPS agreement is considered to have provided the blueprint for URAA's SPS agreement.

Regarding trade in agricultural products, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USITC) asserts that USMCA would build upon NAFTA to make "important improvements in the agreement to enable food and agriculture to trade more fairly, and to expand exports of American agricultural products."8

For USMCA to enter into force, Congress would need to ratify the agreement. It must also be ratified by Canada and Mexico. The timeline for congressional approval of USMCA would likely occur under the Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) timeline established under the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-26).9 At various times, President Trump has stated that he intends to withdraw from NAFTA.10 Some observers have suggested that delays in congressional action on USMCA could make it harder for Canada to consider USMCA approval this year because of upcoming parliamentary elections in October 2019.11

Provisions of USMCA

USMCA seeks to expand upon the agricultural provisions of NAFTA by further reducing market access barriers and strengthening provisions to facilitate trade in North America. An important change in USMCA compared to NAFTA is that the United States agreement with Canada would expand TRQs for imports of U.S. agricultural products into Canada. Other important changes from NAFTA include the agreement between the three countries—Canada, Mexico, and the United States—to further harmonize trade in products of agricultural biotechnology and apply the same health, safety, and marketing standards to agricultural and food imports from USMCA partners as for domestic products.

Expansion of Market Access Provisions

As agreed upon by the leaders of the United States, Canada, and Mexico, all food and agricultural products that have zero tariffs under NAFTA would remain at zero under USMCA. Under USMCA, agricultural products exempted from tariff elimination under the agreement signed between the United States and Canada would be phased out for further market liberalization. Canada currently employs a supply management regime that includes TRQs on imports of dairy and poultry under its NAFTA and World Trade Organization (WTO) market access commitments. Under NAFTA, U.S. dairy has access into the Canadian market under Canada's WTO commitment provisions. For poultry, NAFTA TRQs were established in accordance with the original CUSTA provisions as a percentage of Canada's domestic production.12 When Canada joined the WTO in 1995, it committed to provide poultry market access at the level that is the greater of its commitment under the WTO or under NAFTA.13 For chicken meat, the NAFTA TRQ, set at 7.5% of the previous year's domestic production, is higher than the WTO TRQ set at 39,844 metric tons.14 Canada's chicken meat NAFTA TRQ was 90,100 metric tons in 2018, and the estimate is 95,000 metric tons for 2019.15

Both the poultry and dairy TRQs under NAFTA are global rather than specific to U.S. imports. The WTO dairy TRQs often have specific allocations for individual countries. For example, the bulk of Canada's WTO cheese quota is allocated to the European Union (EU), and the entire WTO powdered buttermilk TRQ is allocated to New Zealand.16 Overall, Canada's TRQs appear to have restricted imports of dairy, poultry, and egg products, as the imported volumes for these products have regularly equaled or exceeded their set quota limits.17

Under USMCA, Canada agreed to increase market access specifically to U.S. exporters of dairy products via new TRQs that are separate from Canada's existing WTO commitments. These additional TRQs apply only to the United States. For chicken meat and eggs, the USMCA replaces the NAFTA commitment with U.S.-specific TRQs. For turkey and broiler hatching eggs and chicks, Canada's NAFTA commitment would be replaced with a minimum access commitment under USMCA, which is not specific to U.S. imports but applies to imports from all origins. While USMCA would expand TRQs for U.S. exports, U.S. over-quota exports would still face the steep tariffs that currently exist under Canada's WTO commitment.18

The United States, in turn, agreed to improve access to Canadian dairy products, sugar, peanuts, and cotton. The United States would increase TRQs for Canadian dairy, sugar, and sweetened products. Tariffs on cotton and peanut imports into the United States from Canada would be phased out and eliminated five years after the agreement would take effect.

As for U.S.-Mexico trade in agricultural products, under NAFTA, Mexico eliminated all the tariffs and quotas that formerly governed agricultural imports from the United States, and the proposed USMCA provides for no further market access changes for imports by Mexico of U.S. agricultural products.

The proposed changes in the market access regime for U.S. agricultural exports to Canada under USMCA are summarized in Table 2. Canada's import restrictions on U.S. dairy products was a high-profile issue for the United States in the USMCA negotiations, so it is noteworthy that under USMCA, Canada agreed to reduce certain barriers to U.S. dairy exports, a key demand of U.S. dairy groups. For one, Canada would make changes to its milk pricing system that sets low prices for Canadian skim milk solids, which is believed to have undercut U.S. exports. Six months after USMCA goes into effect, Canada would eliminate its Class 7 milk price (which includes skim milk solids and is designated as Class 6 in Ontario) and would set its price for skim milk solids based on a formula that takes into account the U.S. nonfat dry milk price. In the future, the United States and Canada would notify each other if either introduces a new milk class price or changes an existing price for a class of milk products.

Under USMCA, Canada would maintain its dairy supply management system, but the TRQs would be increased each year for U.S. exports of milk, cheese, cream, skim milk powder, condensed milk, yogurt, and several other dairy categories. While existing in-quota tariffs for U.S. dairy exports to Canada are mostly zero, the over-quota rates can be as high as 200%-300%.19 USMCA includes provisions on transparency for the implementation of TRQs, such as providing advance notice of changes to the quotas and making public the details of quota utilization rates so that exporters could monitor the extent to which the quotas are filled.

While WTO TRQs are available to U.S. dairy product exporters under the current NAFTA provisions, the new TRQs proposed by Canada under USMCA would expand the access that U.S. dairy products would have into Canada. Large portions of Canada's WTO TRQs are allocated to other countries, such as cheese to the EU and powdered buttermilk to New Zealand. Thus, USMCA TRQs would open additional market opportunities for U.S. dairy exports to Canada. For example, the 64,500 metric ton fluid milk TRQ currently provided under NAFTA is available only for cross-border shoppers, but USMCA would allow up to 85% of the proposed new fluid milk TRQ, which would reach 50,000 metric tons by year 6, to U.S. commercial dairy processors. In response to another concern raised by the U.S. dairy industry, Canada agreed to cap its global exports of skim milk powder and milk protein concentrates and to provide information regarding these volumes to the United States. USMCA includes a requirement that the United States and Canada meet five years after the implementation of the agreement—and every two years after that—to determine whether to modify the dairy provisions of the agreement.

|

Tariff Rate Quotas (TRQs) |

Tariff Rate, % |

|

Agricultural Products Under USMCA

Tariff Rate Quotas

(TRQs)

Tariff Rate, %

NAFTA commitments continue |

0 |

|

|

NAFTA liberalization exemption: Dairy and poultry imports into Canada |

TRQs opened under WTO commitments |

0 in-quota; WTO MFN over-quota tariffs |

|

Dairy, U.S.-specific TRQs, in addition to TRQs under WTO, proposed by Canada |

||

|

50,000 MT by year 6, 56,905 MT by year 19 |

0 in-quota; WTO MFN over-quota >200% |

|

Skim milk powder TRQ begins at 1,250 MT and increases by 1% each year for 13 years after year 6 |

7,500 MT by year 6 |

0 in-quota; WTO MFN over-quota >200% |

|

Cheese TRQ begins at 2,084 MT and increases by 1% each year for 13 years after year 6 |

12,500 MT by year 6 |

0 in-quota; WTO MFN over-quota >200% |

|

Cream TRQ begins at 1,750 MT and increases by 1% each year for 13 years after year 6 |

10,500 MT by year 6 |

0 in-quota; WTO MFN over-quota >200% |

|

Whey TRQ begins at 689 MT and increases by 1% each year after year 6, until year 10 |

4, 135 MT by year 6 |

0 after year 10 |

|

Other dairy products (butter and cream powder, concentrated and condensed milk, yogurt and buttermilk, powdered buttermilk, ice cream, other dairy and margarine) begins at 2,561 MT and increases by 1% each year for 13 years after year 6 |

15,365 MT by year 6 |

0 in-quota; WTO MFN over quota >200% Margarine, 0 after year 5 |

|

Poultry Products, New TRQs proposed by Canada |

||

|

Chicken meat, to increase by 1% each year for 10 years after year 6 |

47,000 MT in year one, reaching 57,000 MT by year 6 |

0 in-quota; WTO MFN over-quota >200% |

|

≥ 3.5% of Canada's previous year's domestic production |

years after year 6

January 2025

MFN over-quota

Sugar and sugar-containing product TRQs under USMCA

Refined sugar TRQ, Canada-specific, new under USMCA

9,600 MT

0 in-quota, WTO MFN over-quota.

Refined sugar TRQ, al ocation of WTO quota

At least 10,300 MT

0 in-quota; WTO

|

|

Eggs and products (eggs and egg-equivalent), to increase by 1% for 10 years after year 6 |

1.67 million dozen in year one, reaching 10 million dozen in year 6 |

MFN over-quota

Sugar-containing product TRQ, al ocation of WTO quota

At least 59,250 MT

0 in-quota; WTO

|

|

Broiler hatching eggs and chick products |

≥ 21.1% of Canada's domestic production for that year |

0 in-quota, >200% over quota |

Source: Agreement MFN over-quota

Source: Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR), “Agreement between the United States of America, the United Mexican States, and Canada 7/1/20 Text,” accessed October 2020, at https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/united-states-mexico-canada-agreement/agreement-between. Notes: MT = metric tons, WTO = World Trade Organization, MFN = Most Favored Nation. MFN tariffs are levied in a nondiscriminatory manner by WTO member countries on al imports excepting imports from countries with a preferential trade agreement when a lower rate of tariff may be applied.

The United States is further guaranteeing market access to Canadian sugar and sugar-containing products by al ocating Canada-specific quotas within the TRQs the United States established per its WTO commitments (see Table 3). The country-specific quotas thus al ocated to Canada are

Congressional Research Service

8

Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement

10,300 MT of refined sugar and 59,250 MT of sugar-containing products.21 Canada is to continue to have access to the U.S. market beyond the set quota levels for sugar and products containing sugar, as applicable under the WTO rights and commitments of the two countries. If in a given year the U.S. WTO sugar quota is unfil ed, the Secretary of Agriculture may al ow additional sugar from Canada to enter duty-free. Canadian sugar and sugar-containing product imports over

the set quota volume wil be levied the higher tariff rates paid by other WTO members.

Modifications tothe United Mexican States, and Canada Text, Signed November 30, 2018; Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement, https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/assets/pdfs/agreements-accords/cusfta-e.pdf; USDA GAIN Report CA0125, 2000, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gainfiles/200008/30677853.pdf. Poultry over-quota tariff rates are as stated under Canada's WTO tariff schedule, WT/TPR/S/112 - WTO Documents Online.

Notes: The TRQs for turkey meat and for broiler hatching eggs and chicks are USMCA minimum global commitment level of anticipated current year's production or the WTO commitment volume, whichever is greater. MT denotes metric tons.

Under USMCA, Canada has proposed to replace its NAFTA commitments for poultry and eggs with new TRQs. Under USMCA, the duty-free quota for chicken meat would start at 47,000 metric tons on the agreement's entry into force and would expand to 57,000 metric tons in year six. It would then continue to increase by 1% per year for the next 10 years (Table 2). The United States would also have access to Canada's WTO chicken quota available to imports from all origins of 39,844 metric tons.20

Under USMCA, Canada's TRQ for imports of U.S. eggs would be phased in over six equal installments, reaching 10 million dozen by year six and then increasing by 1% per year for the next 10 years. The annual TRQ for turkey and broiler hatching eggs and chicks would be set by formulas based on Canadian production (see Table 2). The TRQs for turkey and broiler-hatching eggs and chicks are USMCA minimum global access commitments based on the greater of Canada's anticipated current year production or its WTO commitment volume.

Improved Agricultural Trading Regime

Agricultural Trading Regime Under USMCA, several key provisions would wil further expand the Canadian and Mexican market access to U.S. agricultural producers.2122 With the exception of the wheat grading provision between Canada and Mexico, the following provisions, which aim to improve the trading regime, apply to all three countries:

- agreed

19F

between Canada and the United States, the following provisions apply to al three countries:

Wheat. Canada and the United States

have agreed that they shall accord "treatment no less favorable than it accords to likeagreed to accord the same treatment to “like wheat of domestic origin with respect to the assignment of quality grades."22”23 Currently, U.S. wheat exports to Canada are graded as feed wheat, whichgenerallygeneral y commands a lower price. Under USMCA, U.S. wheat exports to Canadawouldwil receive the same treatment and price as equivalent Canadian wheat if there is a predetermination that the U.S. wheat variety is similar to a Canadian variety. Canada maintains a list of registered wheat varieties, but the United States does not have a similar list. U.S. wheat exporterswouldfirst need to have U.S. varieties approved and registered in Canada before they would be able to benefit from this equivalency provision. According to some stakeholders, this process can be onerous and take several years.23 - 24

Cotton. The addition of a specific textile and apparel chapter to the proposed

USMCAUSMCA may support U.S. cotton production. The chapter promotes greater use of North American–-origin textile products such as sewing thread, pocketing, narrow elastics, and coated fabrics for certain end items. -

Spirits, wine, beer, and other alcoholic beverages. Each country must treat the

distribution of another USMCA country

'’s spirits, wine, beer, and other alcoholic beverages as itwouldwil its own products. The agreementalsoestablishes new rules governing the listing requirements for a product to be sold in a given country with specific limits on cost markups of alcoholic beverages imported fromUSMCA countries. SPS provisions.USMCA's SPS chapter callsUSMCA countries. SPS provisions. USMCA’s SPS chapter cal s for greater transparency in SPS rules and regulatory alignment among the three countries. Itwouldis to establish a new mechanism for technical consultations to resolve SPS issues. SPS provisions provide for increasing transparency in the development and implementation of SPS measures; advancing science-baseddecisionmakingdecision-making; improving processes for certification, regionalization and equivalency determinations; conducting 21 Ibid, Agreement on Agriculture, Chapter 3, Annex 3-A, Agricultural T rade Between Canada and the United States, Article 3.A.5. Sugar and Sugar Containing Products. 22 UST R, Agreement Between the United States of America, the United Mexican States, and Canada 7/1/20 T ext , accessed October 2020, at https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/united-states-mexico-canada-agreement/agreement -between. 23 Ibid. 24 William W. Wilson, “Canada-U.S. Wheat and Barley T rade,” Agriculture and Agri-food Canada, March 30, 2012. Congressional Research Service 9 Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreementfor certification, regionalization and equivalency determinations; conductingsystems-based audits; improving transparency for import checks; and promoting greater cooperation to enhance compatibility of regulatory measures.- Geographical

indicationsindications (GIs)..25 The United States, Canada, and Mexico agreed to provide procedural safeguards for recognition of new GIs, which are place names used to identify products that come from certain regions or locations. USMCAwould protect theprovisions include guidelines to determine whether a term is a common name or a protected GI, grounds for opposition and cancel ation of a GI, and treatment of GIs under third-party agreements. USMCA protects GIs for food products that Canada and Mexico have already agreed to in trade negotiations with the EUand would layand lays out transparency and notification requirements for any new GIs that a country proposes to recognize.The agreement also details a process for determining whether a food name is common or is eligible to be protected as a GI. -

In a side letter accompanying the agreement, Mexico confirmed a list of 33 terms for cheese that

wouldis to remain available USMCA provisions wouldUSMCA provisions are to protect certain U.S., Canadian, and Mexican spirits as distinctive products. Under the proposed agreement, products labeled as Bourbon Whiskey and Tennessee Whiskey must originate in the United States. Similarprotections would existprotections are to exist in the United States and Mexico for Canadian Whiskey, while Tequila and Mezcalwouldwil have to be produced in Mexico. In a side letter accompanying the agreement, the United States and Mexico further agree to protect American Rye Whiskey, Charanda, Sotol, and Bacanora.-

Protections for proprietary food formulas. USMCA signatories

agreeagreed totoprotect the confidentiality of proprietary formula information in the same manner for domestic and imported products. The agreementwould alsoalso is to limit such information requirements to what is necessary to achieve legitimate objectives. -

Biotechnology. The agricultural chapter of USMCA lays out provisions for trade

in products created using agricultural biotechnology, an issue that was not covered under NAFTA. USMCA provisions for biotechnology cover crops produced with

allal biotechnology methods, including recombinant DNA and gene editing. USMCAwouldis to establish a Working Group for Cooperation on Agricultural Biotechnology to facilitate information exchange on policy and trade-related matters associated with the products of agricultural biotechnology. The agreement also outlines procedures to improve transparency in approving and bringing to market agricultural biotech products. It further outlines procedures for handling shipments containing a low-level presence of unapproved products.

While USMCA addresses a number of issues that restrict U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico and Canada, it does not include all al of the changes sought by U.S. agricultural groups. For instance, the agreement example, it does not include changes to trade remedy laws to address imports of seasonal produce as

requested by Southeastern U.S. produce growers. It also does not address nontariff barriers to market access for U.S. fresh potatoes in Mexico24Mexico26 and Canada. Canada's Standard Container Law (part of the Fresh Fruits and Vegetable Regulations of the Canadian Agricultural Products Act) prohibits the importation of U.S. fresh potatoes to Canada in bulk quantities (over 50 kilograms).25 Finally, the agreement does not address the removal of retaliatory tariffs on U.S. agricultural exports imposed by Canada and Mexico in response to U.S. Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum. Some U.S. agriculture stakeholders have expressed concern that the potential benefits of implementing USMCA would be outweighed by the retaliatory tariffs imposed on U.S. agricultural exports by Canada and Mexico.26

’s Standard Container Law

22F

25 UST R, “Agreement Between the United States of America, the United Mexican States, and Canada” Legal T ext, Intellectual Property Rights, Chapter 20, accessed October 2020, at ttps://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/agreements/FT A/USMCA/T ext/20%20Intellectual%20Property%20Rights.pdf.

26 For more information, see CRS Report R44875, The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and U.S. Agriculture, by Renée Johnson.

Congressional Research Service

10

link to page 15 link to page 15 Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement

(part of the Fresh Fruits and Vegetable Regulations of the Canadian Agricultural Products Act) prohibits the imports of U.S. fresh potatoes in quantities over 50 kilograms.27 USMCA also does

23F

not include provisions concerning trade in organic foods.28

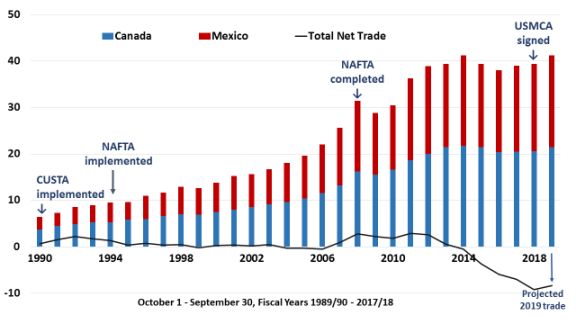

U.S. Agricultural Trade with Canada and Mexico Agricultural trade within North America has increased substantial y since the implementation of CUSTA and NAFTA and in the wake of Mexico’s market-oriented agricultural reforms, which

started in the 1980s (Figure 2). U.S. imports from Canada and Mexico jointly increased in nominal values from $6 bil ion at the start of CUSTA in 1990 to $8 bil ion at the start of NAFTA

in 1994, reaching $52 bil ion in 2019.

Likewise, the nominal value of total U.S. agricultural exports to Canada and Mexico rose from $7 bil ion at the start of CUSTA in 1990 to $10 bil ion at the start of NAFTA in 1994. ItU.S. Agricultural Trade with Canada and Mexico

Since 2002, Canada and Mexico have been two of the top three export markets for U.S. agricultural products (competing with Japan until 2009, when China moved into the top three). In recent years, the two countries have jointly accounted for about 40% of the total value of U.S. agricultural exports. Intraregional trade in North America has increased substantially since the implementation of CUSTA and NAFTA and in the wake of Mexico's market-oriented agricultural reforms, which started in the 1980s (Figure 1). The value of total U.S. agricultural product exports to Canada and Mexico rose from under $7 billion at the start of CUSTA in FY1990 to almost $10 billion at the start of NAFTA in FY1994 and peaked at $41 bil ion in 2014 and was $40 bil ion in 2019$41 billion in FY2014. The lower levelvalue of exports since FY20142014 is partly due to a drought-related decline in livestock production in parts of the United States; increased Canadian production of corn, rapeseed, and soybeans; increased use of U.S. corn as ethanol

feedstock; growth in U.S. export markets outside of NAFTA; and increased competition from

countries outside of NAFTA.29

From July 2018 to May 2019, U.S. exports of certain products to Canada and Mexico declined

due to retaliatory tariffs imposed by these countriesoutside of NAFTA.27 Since mid-2018, U.S. exports of certain products have been adversely affected by the imposition of retaliatory tariffs by Canada and Mexico in response to the Trump Administration's ’s application of a 25% tariff on all U.S. steel imports and a 10% tariff on all U.S. aluminum imports under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962.28

Similar to the growth in U.S. agricultural exports, U.S. imports of agriculture and related products from Canada and Mexico grew from about $6 billion in FY1990 to $8 billion in FY1994, and U.S. agricultural exports continued to increase after NAFTA came into force on January 1, 1994, reaching $48 billion in FY2018. For FY2019, USDA projects that total U.S. agricultural exports to Canada and Mexico will to decline to $41.2 billion, while U.S. imports from those countries are projected at $49.6 billion.29

Billions U.S. dollars |

|

Source: U.S. Census Bureau Trade Data, BICO-HS10, from fas.usda.gov/gats, accessed March 5, 2019. Notes: Net trade = U.S. exports of agricultural products to Canada and Mexico minus U.S. imports |

U.S. Agricultural Exports to Canada and Mexico Geographic proximity provides the United States with a competitive advantage in supplying fresh fruit, vegetables, and prepared food to Canada. Consumer-oriented food products, such as meats, dairy, fruit, vegetables and ready-to-eat products, therefore make up about 80% of al U.S.

agricultural exports to Canada (Table 4).

Although U.S. exports to Canada have not grown in total value over the 2015-2019 period, Canada remains the United States’ largest export market for many agricultural products (Table 4). Canada accounted for 24% of the value of total U.S. consumer-oriented food exports to al

destinations in 2019.33 The same year, Canada accounted for 74% of the total value of U.S. fresh 33 CRS calculation based on U.S. Census T rade Statistics, accessed November 2020, at https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/default.aspx.

Congressional Research Service

12

link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 17 Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement

vegetable exports to al destinations, 51% of snack foods, and 34% of fresh fruit exports to al U.S. Agricultural Exports to Canada and Mexico

Table 3 presents U.S. agricultural exports to Canada for selected years since 1990, the year after the implementation of CUSTA. The other years in the table include 1995 (the year following the start of NAFTA), 2009 (the year following the full implementation of NAFTA), and the last three years with complete fiscal year data: 2016, 2017, and 2018.

U.S. agricultural exports to Canada averaged over $20 billion between FY2016 and FY2018 period (Table 3) and accounted for 14% of the total value of U.S. agriculture exports in FY2018. While the overall value of U.S. agricultural exports to Canada has increased under NAFTA, U.S. exports of consumer-ready food products registered the greatest increase, accounting for almost 80% of the value of all U.S. agricultural exports to Canada in FY2018. Canada accounted for 24% of the value of total U.S. consumer-ready food product exports to all destinations in FY2018.

In FY2018, Canada accounted for 72% of the total value of U.S. fresh vegetable exports to all destinations, 54% of nonalcoholic beverage exports to all destinations, 51% of snack food exports to all destinations, 33% of total exports of fresh fruit, 33% of live animal exports, and 26% of total U.S. wine and beer exports to all destinations. Canada is also an important market for bulk agricultural commodities, and Canadian imports of U.S. corn, soybeans, rice, pulses, and wheat have increased since the implementation of NAFTA.

Table 3. Major U.S. Agricultureincreased significantly over the 2015-

2019 period (Table 4).

Table 4. Major U.S. Agricultural Exports to Canada

In Mil ions of U.S. Dol ars, 2015-2019

2015-2019

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

change

Total agriculture

20,989

20,307

20,608

20,867

20,886

0%

Total consumer-oriented

16,865

16,222

16,370

16,216

16,300

-3%

Prepared food

1,909

1,889

1,908

1,931

2,048

7%

Fresh vegetables

1,871

1,807

1,878

1,884

1,986

6%

Fresh fruit

1,649

1,633

1,608

1,533

1,485

-10%

Snack foods

1,332

1,315

1,355

1,407

1,393

5%

Pork & products

778

798

793

765

802

3%

Pet food

602

597

640

645

751

25%

Chocolate & cocoa products

725

749

748

713

713

-2%

Tree nuts

686

598

643

696

697

2%

Dairy products

554

630

637

641

667

20%

Beef & products

900

758

791

745

654

-27%

Poultry meat, excluding eggs

594

510

459

406

354

-40%

Eggs & products

184

98

102

121

99

-46%

Live animals

118

126

251

263

315

167%

Corn

212

146

131

309

349

65%

Rice

160

148

148

175

194

21%

Soybeans

80

106

145

269

181

126%

Pulses

54

101

130

62

105

94%

Wheat

14

18

17

21

37

164%

Source: U.S. Census Bureau Trade Data, BICO-10 groupings, accessed via FAS. USDA, October 2020, at https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/ExpressQuery1.aspx. Notes: Data are not adjusted for inflation. As defined by USDA, consumer-oriented products includes meats, fruit, vegetables, processed food products, beverages, and pet food. Selected groupings presented; entries do not sum to total.

U.S. dairy exports to Canada increased 20% from 2015 to 2019, but the exports of U.S. poultry

meat and eggs declined over 40% during this period (Table 4).

In the first calendar quarter after USMCA entered into force in July 2020, U.S. poultry meat exports to Canada were 8% higher than during the same quarter of 2019 and 3% higher than the same quarter of 2018 (Figure 3). U.S. dairy exports to Canada in the third quarter of 2020 were 10% higher than in the year-earlier quarter and 9% above the corresponding quarter of 2018. Although USMCA has expanded access for U.S. eggs and egg products, U.S. exports of these

products to Canada have not increased compared to the previous two years.

Congressional Research Service

13

link to page 18 Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement

Figure 3. U.S. Dairy and Poultry Product Exports To Canada

In Mil ions of Dol ars, First 3 Quarters Of 2018-2020

180

160

20182019

140

2020

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

Qtr. 1 Qtr. 2 Qtr. 3

Qtr. 1 Qtr. 2 Qtr. 3

Qtr. 1 Qtr. 2 Qtr. 3

Dairy products

Poultry meat

Eggs and products

Source: U.S. Census Bureau Trade Data, BICO-10 groupings, accessed via FAS. USDA, November 2020, at https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/ExpressQuery1.aspx. Note: Qtr. = quarter.

Mexico has accounted for about 13%-14% of the total value of U.S. agricultural exports since 2015. Geographic proximity, growing population, and an expanding economy have increased Mexico’s import demand for consumer-oriented food products like dairy, meats, prepared foods, fruit, vegetables, and other ready-to-eat food products as wel as for pet food. An expanding

domestic livestock sector has also increased Mexico’s import demand for U.S. feed grains, soybeans, and other feed and fodders. U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico have thus increased during 2015-2019 period for both bulk commodities and for consumer-oriented high-value

products (Table 5.)

Consumer-oriented products as a group account for a significant share of U.S. exports to Mexico, and 13% of the total value of exports of this category to al destinations in 2019. This includes

26% of dairy exports, 25% of poultry exports, and 18% of pork exports to al foreign markets.34

During the first three quarters of 2020 (January-August), U.S. exports to Mexico were down 8% in value ($12.96 bil ion), year-on-year, compared to 2019 ($14.08 bil ion). A market analysis report points out that Mexico faced difficulties in transportation and logistics with the outbreak of

COVID-19, particularly with regard to a shortage of refrigerated containers,35 which would have

affected trade in perishable consumer-oriented food products.

34 Ibid. 35 T ridge, COVID-19 Market Report: Impact of the Coronavirus on Global Agricultural Trade, March 31, 2020, at https://cdn.tridge.com/reports/covid19-market-report-v2.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

14

link to page 19 Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement

Table 5. Major U.S. Agricultural Exports to Mexico

In Mil ions of U.S. Dol ars, 2015-2019

2015-2019

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

change

Total agriculture

17,695

17,827

18,598

19,090

19,179

8%

Total consumer-oriented

8,378

8,051

8,341

8,590

8,962

7%

Dairy products

1,280

1,218

1,312

1,398

1,546

21%

Pork & products

1,268

1,360

1,514

1,311

1,278

1%

Beef & products

1,092

977

979

1,058

1,107

1%

Poultry meat, excluding eggs

1,029

931

933

956

1,077

5%

Prepared food

705

710

678

743

777

10%

Fresh fruit

560

501

570

619

610

9%

Tree nuts

269

253

256

371

343

28%

Condiments & sauces

218

221

214

215

243

11%

Snack foods

293

296

283

320

342

17%

Fresh vegetables

123

101

134

141

193

57%

Processed fruit

119

112

120

126

135

13%

Nonalcoholic beverages

137

116

139

123

149

9%

Pet food

67

77

85

90

103

54%

Corn

2,302

2,550

2,645

3,061

2,730

19%

Soybeans

1,432

1,462

1,574

1,818

1,878

31%

Wheat

651

612

852

662

812

25%

Feeds & fodders

146

154

158

184

229

57%

Coarse grains, excluding corn

78

132

79

39

132

69%

Source: U.S. Census Bureau Trade Data, BICO-10 groupings, accessed via FAS. USDA, October 2020, at https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/ExpressQuery1.aspx. Notes: Data are not adjusted for inflation. As defined by USDA, consumer-oriented products includes meats, fruit, vegetables, processed food products, beverages, and pet food. Selected groupings presented; entries do not sum to total.

U.S. Imports from Canada and Mexico Canada and Mexico are the top two sources of U.S. agricultural imports, and jointly provided

40% of the $131 bil ion of U.S. agricultural imports from al sources in 2019.36

U.S. Imports from Canada

Since 2016, Canada has been the second-largest supplier of agricultural products to the United States, accounting for around 18% of the total value of U.S. imports of these products. About

two-thirds of al agricultural imports from Canada are consumer-oriented products (Table 6).

36 U.S. Census Bureau T rade Data, BICO-6 groupings, accessed via FAS. USDA, October 2020, at https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/ExpressQuery1.aspx.

Congressional Research Service

15

Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement

Table 6. Major U.S. Agricultural Imports from Canada

In Mil ions of U.S. Dol ars, 2015-2019

2015-2019

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

change

Total agriculture

21,821

21,526

22,309

23,035

23,612

8%

Total consumer-oriented

13,023

13,390

14,115

14,881

15,669

20%

Snack foods

3,733

4,015

4,192

4,541

4,815

29%

Red meats, fresh/frozen/chilled

2,253

2,217

2,273