Syria: Transition and U.S. Policy

Changes from March 25, 2019 to February 12, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Background

- Issues for Congress

- Syria

-Related Legislation in the 116th Congress - Recent Developments

- Military

- Islamic State Loses Last Territorial Stronghold

- Idlib: The Final Opposition Stronghold

- Turkish Operations in Northern Syria

- Israeli Strikes in Syria

- FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 116-92)

- Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-94)

- Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-93)

- Syria-Related Legislation in the 116th Congress

- Special Immigrant Status for U.S. Partner Forces

- Military Developments

- Turkish Incursion into Northern Syria

- Islamic State: Ongoing Threats

- Idlib: The Final Opposition Stronghold

- Political Negotiations

- The Geneva Process

- The Astana Process

- Humanitarian Situation

- Cross-Border Aid Endangered

- U.S. Policy

- Trump Administration Statements on Syria Policy

- U.S. Assistance to Vetted Syrian Groups U.S. Military Operations;

- Political Negotiations

- The Geneva Process

- The Astana Process

- Kurdish Outreach to Asad Government

- Humanitarian Situation

- U.S. Humanitarian Funding

- International Humanitarian Funding

- U.S. Policy

- Trump Administration Syria Policy Evolves in 2018

- 2018: President Trump Announces Withdrawal of U.S. Forces

- 2019: Some U.S. Troops to Remain in Syria

- President Trump Recognizes Israeli Claim to Golan Heights

- Presidential Authority to Strike Syria under U.S. Law

- U.S. Assistance

U.S. Military Operations in Syria and U.S.Train, Advise, Assist, and Equip Efforts- U.S. Military Presence in Syria

- U.S. Repositions Forces in 2019

Syria Train and Equip Program- FY2019 Legislation

FY2020FY2021 Defense Funding Request- U.S. Nonlethal and Stabilization Assistance

- FY2019 Legislation and the FY2020 Request

- Overview: Syria Chemical Weapons and Disarmament

- Chemical Weapons Use

- 2018 Chemical Attack (Douma) and U.S. Response

- 2017 Chemical Attack (Khan Sheikhoun) and U.S. Response

- 2013 Chemical Weapons Attack (Ghouta)

- Syria and the CWC: Disarmament Verification

- International Investigations of CW Use

- Outlook

- Consolidating Gains Against the Islamic State

- Conflict in Northwestern Syria

- The Future of Displaced Syrians

- Reconstruction

- Addressing Syria-based Threats to Neighboring Countries

- Syria's Political Future

- Implications for Congress

- Author Contact Information

- Consolidating Gains against the Islamic State

- Preserving Relationships with Partner Forces

- Countering Iran

- Addressing Humanitarian Challenges in Extremist-Held Areas

- Assisting Displaced Syrians

- Preventing Involuntary Refugee Returns

- Managing Reconstruction Aid

- Supporting a Political Settlement to the Conflict

Figures

Summary

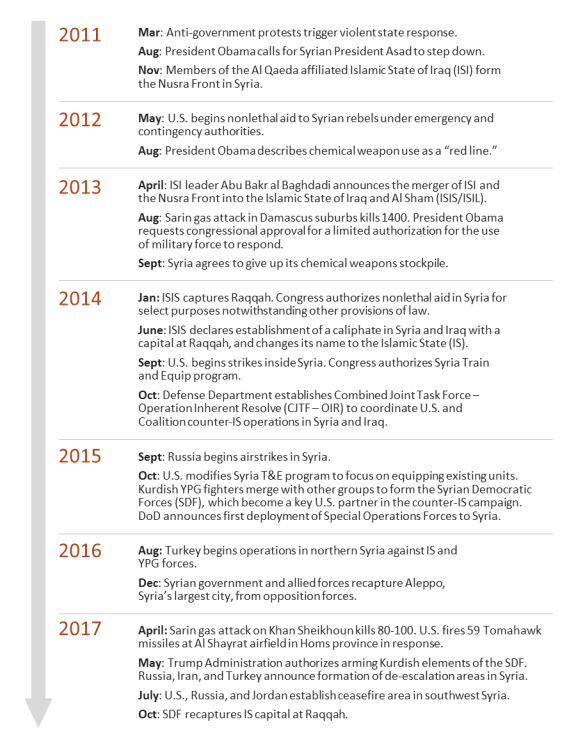

Since its start in 2011, the Syria conflict has presented significant policy challenges for the United States. (For a brief conflict summary, see Figure 2). U.S. policy toward Syria since 2014 has prioritized counterterrorism operations against the Islamic State (IS, also known as ISIL/ISIS), but also has included nonlethal assistance to Syrian opposition groups, diplomatic efforts to reach a political settlement to the civil war, and humanitarian aid to Syria and regional countries affected by refugee outflows.which sought to direct external attacks from areas under the group's control in northeast Syria. Since 2015, U.S. forces deployed to Syria have trained, equipped, and advised local partners under special authorization from Congress and have worked primarily "by, with, and through" those local partners to retake nearly all areas formerly held by the Islamic State.

In addition to counterterrorism operations against the Islamic State, the United States also has responded to Syria's ongoing civil conflict by providing nonlethal assistance to Syrian opposition and civil society groups, encouraging diplomatic efforts to reach a political settlement to the civil war, and serving as the largest single donor of humanitarian aid to Syria and regional countries affected by refugee outflows. Following an internal policy review, Administration officials in late 2018 had described U.S. policy toward As of 2020, about 600 U.S. troops remain in Syria.

President Trump's December 2018 announcement that U.S. forces had defeated the Islamic State and would leave Syria appeared to signal the start of a new U.S. approach. However, in February 2019, the White House stated that several hundred U.S. troops would remain in Syria, and the President is requesting $300 million in FY2020 defense funding to continue to equip and sustain Syrian partner forces. The FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 115-232) required the Administration to clarify its Syria strategy and report on current programs in order to obligate FY2019 defense funds for train and equip purposes in Syria.

Enduring defeat of ISIS. U.S.-backed partner forces re-captured the Islamic State's final territorial strongholds in Syria in March 2019. However, U.S. military officials in late 2019 assessed that the group remains cohesive, retains an intact command structure, and maintains an insurgent presence in much of rural Syria. The Defense Department has not disaggregated the costs of military operations in Syria from the overall cost of the counter-IS campaign in Syria and Iraq (known as Operation Inherent Resolve, OIR), which had reached $40.5 billion by December 2019.

Political settlement to the conflict. The United States continues to advocate for a negotiated settlement between the government of Syrian President Bashar al Asad and Syrian opposition forces in accordance with U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254 (which calls for the drafting of a new constitution and U.N.-supervised elections). However, the Asad government's use of force to retake most opposition-held areas of Syria has reduced pressure on Damascus to negotiate, and U.S. intelligence officials in 2019 assessed that Asad has little incentive to make significant concessions to the opposition. U.S. officials have stated that the United States will not contribute aid to reconstruction in Asad-held areas unless a political solution is reached.

The United States has directed more than $9.1 billion toward Syria-related humanitarian assistance, and Congress has appropriated billions more for security and stabilization initiatives in Syria and neighboring countries. The Defense Department has not disaggregated the costs of military operations in Syria from the overall cost of the counter-IS campaign in Syria and Iraq (known as Operation Inherent Resolve, OIR), which had reached $28.5 billion by September 2018.

External Players. A range of foreign states have intervened in Syria in support of the Asad government or Syrian opposition forces, as well in pursuit of domestic security goals. Pro-Asad forces operating in Syria include Lebanese Hezbollah, Iran, and Russia. The United States and a range of regional and European states have at times backed select portions of the Syrian opposition, while also expressing concern about reported ties between some armed opposition groups and extremist elements. Israel has acknowledged conducting over 200 military strikes in Syria, mostly targeting Hezbollah and/or Iranian targets. In addition, Turkey maintains military forces in northern Syria as part of a broader campaign targeting Kurdish fighters. Humanitarian Situation. As of 2020, roughly half of Syria's pre-war population remains internally displaced (6.2 million) or registered as refugees in neighboring states (5.6 million). The United States has directed nearly $10.5 billion toward Syria-related humanitarian assistance since FY2012, and Congress has appropriated billions more for security and stabilization initiatives in Syria and neighboring countries. The 115th Congress considered proposals to authorize or restrict the use of force against the Islamic State and in response to Syrian government chemical weapons attacks, but did not enact any Syria-specific use of force authorizations. The 116th Congress may seek

Background

In March 2011, antigovernment protests broke out in Syria, which has been ruled by the Asad family for more than four decades. The protests spread, violence escalated (primarily but not exclusively by Syrian government forces), and numerous political and armed opposition groups emerged. In August 2011, President Barack Obama called on Syrian President Bashar al Asad to step down. Over time, the rising death toll from the conflict, and the use of chemical weapons by the Asad government, intensified pressure for the United States and others to assist the opposition. In 2013, Congress debated lethal and nonlethal assistance to vetted Syrian opposition groups, and authorized the latter. Congress also debated, but did not authorize, the use of force in response to an August 2013 chemical weapons attack.

In 2014, the Obama Administration requested authority and funding from Congress to provide lethal support to vetted Syrians for select purposes. The original request sought authority to support vetted Syrians in "defending the Syrian people from attacks by the Syrian regime," but the subsequent advance of the Islamic State organization from Syria across Iraq refocused executive and legislative deliberations onto counterterrorism. Congress authorized a Department of Defense-led train and equip program to combat terrorist groups active in Syria, defend the United States and its partners from Syria-based terrorist threats, and "promote the conditions for a negotiated settlement to end the conflict in Syria."

In September 2014, the United States began air strikes in Syria, with the stated goal of preventing the Islamic State from using Syria as a base for its operations in neighboring Iraq. In October 2014, the Defense Department established Combined Joint Task Force-Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF-OIR) to "formalize ongoing military actions against the rising threat posed by ISIS in Iraq and Syria." CJTF-OIR came to encompass more than 70 countries, and has bolstered the efforts of local Syrian partner forces against the Islamic State. The United States also gradually increased the number of U.S. personnel in Syria from 50 in late 2015 to roughly 2,000 by late 2017. President Trump in early 2018 called for an expedited withdrawal of U.S. forces from Syria,1 but senior Administration officials later stated that U.S. personnel would remain in Syria to ensure the enduring defeat of the Islamic State. Then-National Security Advisor John Bolton also stated that U.S. forces would remain in Syria until the withdrawal of Iranian-led forces.2 In December 2018, President Trump ordered the withdrawal of all U.S. forces from Syria, contributing to the subsequent decision by Defense Secretary James Mattis to resign, and drawing criticism from several Members of Congress. In early 2019, the White House announced that several hundred U.S. troops would remain in Syria.

The collapse of IS and oppositionAs the Islamic State and armed opposition groups have relinquished territorial control inover most of Syria since 2015 has been matched by, the Syrian government and its foreign partners have made significant military and territorial gains by the Syrian government. The U.S. intelligence community's 2018 Worldwide Threat Assessment stated in February 2018 that, "The conflict has the conflict had by that point "decisively shifted in the Syrian regime's favor, enabling Russia and Iran to further entrench themselves inside the country."3 At the same time, ongoing conflict between the coalition's Syrian Kurdish partners and Turkey has continued to challenge U.S. policymakers, as has the entrenchment of Al Qaeda-affiliated groups among the opposition and the ongoing humanitarian crisis. As of 2019, 5.7 million Syrians are registered as refugees in nearby countries, with 6.2 million more internally displaced.

The U.N. has sponsored peace talks in Geneva since 2012, but it is unclear when (or whether) the parties might reach a political settlement that couldCoalition and U.S. gains against the Islamic State came largely through the assistance of Syrian Kurdish partner forces, but neighboring Turkey's concerns about those Kurdish forces emerged as a persistent challenge for U.S. policymakers. In 2019, Turkey launched a cross border military operation attempting to expel Syrian Kurdish U.S. partner forces from areas adjacent to the Turkish border. In conjunction with the operation, President Trump ordered the withdrawal of some U.S. forces from Syria and the repositioning of others in areas of eastern Syria once held by the Islamic State group.

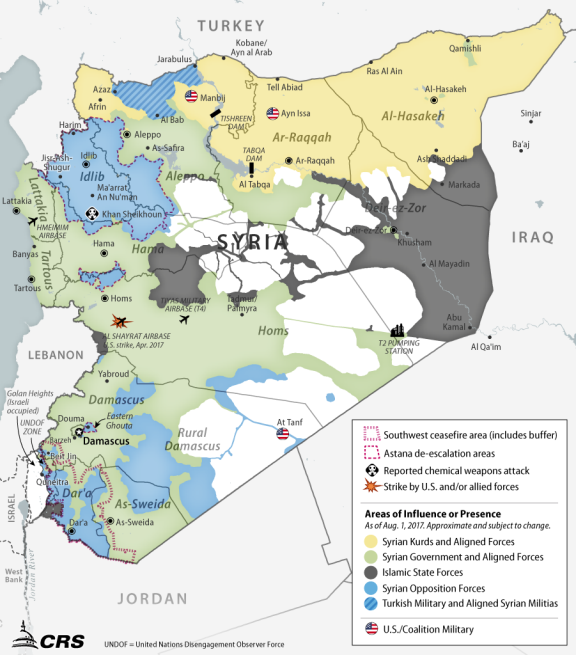

Territorial gains by the Syrian government have pushed remaining opposition forces (including Al Qaeda affiliates) into a progressively shrinking geographic space that is also occupied by roughly 3 million Syrian civilians. (Figure 3 and Figure 4 show how territory held by Syrian opposition forces was significantly reduced between 2017 and 2020.) The remaining opposition-held areas of Idlib province in northwestern Syria have faced intensified and ongoing Syrian government attacks since 2019.

The U.N. has sponsored peace talks in Geneva since 2012, but it appears unlikely that the parties will reach a political settlement that would result in a transition away from Asad. With many armed opposition groups weakened, defeated, or geographically isolated, military pressure on the Syrian government to make concessions to the opposition has been reduced. U.S. officials have stated that the United States will not fund reconstruction in Asad-held areas unless a political solution is reached in accordance with U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254.4

|

|

Geography |

Size: 185,180 sq km (slightly larger than 1.5 times the size of Pennsylvania) |

|

General Demographics |

Population: 19.5 million (July 2018 est.) Religions: Muslim 87% (Sunni 74% and Alawi, Ismaili, and Shia 13%), Christian 10%, Druze 3% Ethnic Groups: Arab 90.3%, Kurdish, Armenian, and other 9.7% |

|

Indicators of Humanitarian Need |

People in need of humanitarian assistance: 13 million Internally displaced persons: 5.7 million Syrian refugees: 5.6 million Unemployment rate: 50% (2017 est.) Population living in extreme poverty: 69% (2018 est., UNOCHA) Sources: CRS using data from U.S. State Department; Esri; CIA, The World Factbook; and the United Nations. Note: On March 25, 2019, President Trump recognized the Golan Heights as part of the state of Israel. |

| 2019 |

|

|

Note: For more information, see CRS In Focus IF11080, Syria Conflict Overview: 2011-2018, by Carla E. Humud. |

Issues for Congress

Congress has considered the following key issues since the outbreak of the Syria conflict in 2011:

- What are the core U.S. national interests in Syria? What objectives derive from those interests? How should U.S. goals in Syria be prioritized?

What financial, military, and personnel resources are required to implement U.S. objectives in Syria? What measures or metrics can be used to gauge progress?- Should the U.S. military continue to operate in Syria? For what purposes and on what authority? For how long?

- How are developments in Syria affecting other countries in the region, including U.S. partners?

- What potential consequences of U.S. action or inaction should be considered? How might other outside actors respond to U.S. choices?

Amid significant territorial losses by the Islamic State and Syrian opposition groups since 2015 and parallel military gains by the Syrian government and coalition partner forces, U.S. policymakers face a number of questions and potential decision points related to the following factors:

Counter-IS operations and the presence of U.S. military personnel in Syria

The announcement by President Trump in December 2018 that U.S. forces would withdraw from Syria was welcomed by the Syrian government and its Russian and Iranian partners, along with observers who questioned the necessity, utility, and legality of continued U.S. operations. The decision also drew domestic and international criticism from those who argued it could enable the reemergence of the Islamic State and embolden Russia and Iran in Syria (see "2018: President Trump Announces Withdrawal"). Some Members of Congress called upon President Trump to reconsider his decision to withdraw U.S. forces, stating that the move was premature and "threatens the safety and security of the United States."5 Others embraced the decision, citing concerns about the lack of specific authorization for the U.S. campaign and the effectiveness of U.S. efforts.6 In February 2019, the White House reversed its December announcement, stating that roughly 400 U.S. troops would remain in Syria.

Members of the 116th Congress may seek clarification on the Administration's strategy to ensure the enduring defeat of the Islamic State. A Lead Inspector General report on Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) released in February 2019 states that, "absent sustained [counterterrorism] pressure, ISIS could likely resurge in Syria within six to twelve months and regain limited territory in the [Middle Euphrates River Valley (MERV)]."7

The future of the Syria Train and Equip program

The Islamic State has lost the territory it once held in Syria, and much of that territory is now controlled by local forces that have received U.S. training and assistance since 2014. (See Figure 3 and Figure 4.) In 2017 and 2018, significant reductions in IS territorial control prompted some reevaluation of the Syria Train and Equip (T&E) program, whose primary purpose had been to support offensive campaigns against Islamic State forces. The Trump Administration requested $300 million in FY2019 Counter-ISIS Train and Equip Fund (CTEF) monies for Syria programs, largely intended to shift toward training local partners as a hold force. The Department of Defense Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-245) provided $1.35 billion for the CTEF account, slightly less than the Administration's requested amount for the overall account ($1.4 billion) based on congressional concerns about some Syria-related funds.

The FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) extended the Syria T&E program's authority through the end of 2018, but the FY2018 NDAA did not extend it further, asking instead for the Trump Administration to submit a report on its proposed strategy for Syria by February 2018. The FY2019 NDAA (P.L. 115-232) prohibited the obligation of FY2019 defense funds for the program until the strategy required by the FY2018 NDAA and an additional update report on train and equip efforts was submitted to Congress. The FY2019 act extended the Syria T&E authority through December 2019 but did not adjust the program's authorized scope or purposes.

The Administration's FY2020 defense funding request seeks an additional $300 million to equip and sustain vetted Syrian opposition (VSO) forces.

The future of U.S. relations with the Asad government

Strained U.S.-Syria ties prior to the start of the conflict, including Syria's designation as a State Sponsor of Terrorism, are reflected in a series of U.S. sanctions and legal restrictions that remain in place today. U.S. policy toward Syria since August 2011 has been predicated on a stated desire to see Bashar al Asad leave office, preferably through a negotiated political settlement. However, the Asad government—backed by Russia and Iran—has reasserted control over much of western Syria since 2015, and appears poised to claim victory in the conflict. In an acknowledgement of the conflict's trajectory, U.S. calls for Asad's departure have largely faded. In late 2018, senior Administration officials stated that while "America will never have good relations with Bashar al Asad," the Syrian people ultimately "get to decide who will lead them and what kind of a government they will have. We are not committed to any kind of regime change."8 Nevertheless, the Trump Administration has stated its intent to refrain from supporting reconstruction efforts in Syria until a political solution is reached in accordance with UNSCR 2254, which calls for constitutional reform and U.N.-supervised elections.

The future of U.S. assistance and stabilization programs in Asad-led Syria

In the short term, policy discussions may focus on whether or how the Syrian government's reassertion of de facto control should affect U.S. military and assistance policy. The Trump Administration has directed a reorientation in U.S. assistance programs in Syria and has sought and arranged for new foreign contributions to support the stabilization of areas liberated from Islamic State control. The practical effect of this approach to date has been the drawdown of some assistance programs in opposition-held areas of northwestern Syria and the reprogramming of some U.S. funds appropriated by Congress for stabilization programs in Syria to other priorities. The future of U.S.-administered stabilization and other assistance programs in formerly opposition-held areas of Syria and areas currently held by U.S. partner forces is in question, in light of both the Asad government's reassertion of control in many areas, the planned reduction of U.S. military forces, and the December 2018 withdrawal of State Department and USAID personnel from northern Syria.

As noted above, the Administration has stated its intention to end U.S. nonhumanitarian assistance to Asad-controlled areas of the country until the Syrian government fulfills the terms of UNSCR 2254. The Administration also has stated its intent to use U.S. diplomatic influence to discourage other international assistance to government-controlled Syria in the absence of a credible political process.9

Then-U.N. Special Envoy for Syria Staffan de Mistura said in 2017 that Syria reconstruction will cost at least $250 billion,10 and a group of U.N.-convened experts estimated in August 2018 that the cost of conflict damage could exceed $388 billion.11 Congress may debate how the United States might best assist Syrian civilians in need, most of whom live in areas under Syrian government control, without inadvertently strengthening the Asad government or its Russian and Iranian patrons.

Syria-Related Legislation in the 116th Congress

Strengthening America's Security in the Middle East Act of 2019 (S. 1)

Introduced on January 3 by Senator Rubio and three cosponsors, the bill incorporates the Senate version of the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act of 2018 considered during the 115th Congress and passed by the House in a different version. Title III would require the Secretary of the Treasury to make a determination within 180 days of enactment on whether the Central Bank of Syria is a financial institution of primary money laundering concern. If so, the bill would require the Secretary to impose one or more of the special measures described in Section 5318A(b) of Title 31, United States Code. The bill also would expand the scope of secondary sanctions on Syria to include foreign persons who knowingly provide support to Russian or Iranian entities operating on behalf of the Syrian government. It would also make eligible for sanctions foreign persons who knowingly sell or provide military aircraft and energy sector goods or services, or who knowingly provide significant construction or engineering services to the government of Syria. The bill does include several suspension and waiver authorities for the President. Its provisions would expire five years after the date of enactment.

Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act of 2019 (H.R. 31, S. 52)

In January, the House passed the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act of 2019, introduced by Representative Engel (H.R. 31). A version of the bill was also introduced in the Senate by Senators Risch, Menendez, and Rubio (S. 52). An earlier version of the bill was considered during the 115th Congress. H.R. 31 would eliminate Sections 103 to 303 of S. 52 (primarily amendments to the Syria Human Rights Accountability Act of 2012). The House bill retains all of the provisions found in Title III of S. 1 (see above).

No Assistance for Assad Act (H.R. 1706)

Introduced in March by Representative Engel, the bill would state that it is the policy of the United States that U.S. foreign assistance made available for reconstruction or stabilization in Syria should only be used in a democratic Syria or in areas of Syria not controlled by the Asad government or aligned forces. Reconstruction and stabilization aid appropriated or otherwise available from FY2020 through FY2024 could not be provided "directly or indirectly" to areas under Syrian government control—as determined by the Secretary of State—unless the President certifies to Congress that the government of Syria has met a number of conditions. These include ceasing air strikes against civilians, releasing all political prisoners, allowing regular access to humanitarian assistance, fulfilling obligations under the Chemical Weapons Convention, permitting the safe and voluntary return of displaced persons, taking steps to establishing meaningful accountability for perpetrators of war crimes, and halting the development and deployment of ballistic and cruise missiles. The House passed an earlier version of the bill during the 115th Congress.

By noting restrictions on U.S. aid provided "directly or indirectly," the bill also would limit U.S. funds that could flow into Syria via multilateral institutions and international organizations, including the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank. The bill would permit exceptions to the above restrictions on aid to government-held areas for humanitarian projects, "projects to be administered by local organizations that reflect the aims, needs, and priorities of local communities," and projects that meet basic human needs including drought relief; assistance to refugees, IDPs, and conflict victims; the distribution of food and medicine; and the provision of health services.

The bill would also state that it is the sense of Congress that the United States should not fund projects in which any Syrian government official or immediate family member has a financial or material interest, or is affiliated with the implementing partner.

Recent Developments

Military

Islamic State Loses Last Territorial Stronghold

On March 23, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) announced that the Islamic State had lost its final stronghold in the eastern Syrian town of Baghouz.12 President Trump initially announced the group's defeat in December 2018, although Coalition and SDF operations against the group continued in 2019.13 In early March CENTCOM Commander General Joseph Votel stated that the territory held by the Islamic State had been reduced down to a single square mile near Baghouz, along the Euphrates River (Figure 3). However, Votel also noted,

we should be clear that what we are seeing now is not the surrender of ISIS as an organization, but a calculated decision to preserve the safety of their families and preservation of their capabilities by taking their chances in camps for internally displaced persons and going to ground and remote areas and waiting for the right time to resurge.14

Votel also noted that, "ISIS population being evacuated from the remaining vestiges of caliphate largely remain unrepentant, unbroken, and radicalized. We will need to maintain a vigilant offensive against this now widely dispersed and disaggregated organization."15 Coalition officials previously have stated that they do not intend to operate in Syrian-government controlled territory,16 despite reports that IS militants remain present in those areas.17

Continued attacks by the Islamic State in 2019 have raised concerns about the group's resiliency and potential to regenerate, particularly given plans to withdraw most U.S. military forces from Syria. On January 16, a suicide bombing claimed by the Islamic State killed 4 Americans and 15 others in the northern city of Manbij, in Aleppo province. One week later, a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device targeted a joint American-SDF patrol in the town of Ash Shaddadi in Hasakah province. Both cities were liberated from the Islamic State in 2016. The most recent Lead Inspector General report on Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) states that, "absent sustained [counterterrorism] pressure, ISIS could likely resurge in Syria within six to twelve months and regain limited territory in the [Middle Euphrates River Valley (MERV)]."18

Prior to the Administration's withdrawal announcement in December 2018, U.S. officials had stated that once the conventional fight against the Islamic State was completed, the coalition would shift to a "new phase" focused on stabilization, including the training of local forces to hold liberated areas.19 These plans were reflected in the Defense Department and State Department requests for appropriations for FY2019. Following the Administration's February announcement that several hundred U.S. troops would remain in Syria, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Joseph Dunford stated,

[...] this is about campaign continuity. So we had a campaign that was designed to clear ISIS from the ground that they had held, and we always had planned to transition into a stabilization phase where we train local forces to provide security and prevent the regeneration of ISIS. So there is -- there is no change in the basic campaign, the resourcing is being adjusted because the threat has been changed.

While military officials have emphasized the continuity of the U.S. military campaign, it is not clear whether the threat posed by the Islamic State is similarly unchanged, particularly as the group shifts from controlling territory to operating as what General Votel has described as a "clandestine insurgency."20 U.S. officials in 2018 stated that the Islamic State had "atomized," becoming more dispersed in its command and control, and posing a more decentralized threat.21 Former U.S. Special Envoy Brett McGurk, who resigned in December 2018, had stated that the "defeat of the physical space is not the defeat of ISIS," noting that the group is less vulnerable to conventional military operations once it no longer holds large areas of territory.22

|

Islamic State Detainees in Syria U.S. officials have reported that over 700 detainees from about 40 different countries are currently in SDF custody, and that the State Department is engaged in ongoing discussions to secure the repatriation of detainees to their home countries.23 U.S. officials have stated that both the ongoing detention and the eventual repatriation of these individuals must be handled with care, noting that the early leaders of Islamic State were former detainees (from the 2003-2011 U.S. war in Iraq). Neither their home countries nor the SDF wish to assume long-term responsibility for the detainees, which are viewed as a security risk.24 |

Idlib: The Final Opposition Stronghold

Idlib province has been under rebel control since 2015, hindering the Asad government's ability to transit directly from government-held areas in the south to Syria's largest city of Aleppo, in the north. While a range of opposition groups operate in Idlib, U.S. officials have described the province as a safe haven for Al Qaeda, while also highlighting the significant civilian presence. U.S. initiatives in Idlib aimed at countering violent extremism (CVE) were halted in May 2018 as part of a broader withdrawal of U.S. assistance to northwest Syria.25

De-escalation Area & Demilitarized Zone. In May 2017, an agreement between Russia, Iran, and Turkey established the Idlib de-escalation area (encompassing all of Idlib province as well as portions of neighboring Lattakia, Aleppo, and Hama provinces).26 The agreement was designed to reduce violence between regime and opposition forces. However, regime forces continued to pursue military operations in the area, recapturing about half of the de-escalation area by mid-2018. Both regime and armed opposition forces expressed determination to control the remaining portions of Idlib, raising fears that a large-scale offensive pitting Syrian government forces against a mix of armed opposition and jihadist forces could trigger a humanitarian crisis for civilians in the area. In October 2018, Russia and Turkey created a demilitarized zone in parts of Idlib province to separate the two sides.

2019 Jihadist Advance. In January 2019, the Al Qaeda-linked group Haya't Tahrir al Sham (HTS) seized large areas of Idlib province from rival armed groups, forcing them to accept an HTS-run civil administration. HTS was established in 2017 as a successor to the Nusra Front (Al Qaeda's formal affiliate in Syria). U.S. officials have stated that "The core of HTS is Nusra,"27 and amended the FTO designation of the Nusra Front in May 2018 to include HTS as an alias.

Al Qaeda in Idlib

U.S. officials in mid-2017 described Idlib province as "the largest Al Qaeda safe haven since 9/11."28 Beginning in 2014, the United States conducted a series of air strikes, largely in Idlib province, against Al Qaeda targets. These strikes fell outside the framework of Operation Inherent Resolve (which focuses on the Islamic State), and U.S. officials stated that they were conducted on the basis of the 2001 AUMF.29 At least a dozen foreign Al Qaeda leaders have been killed in Syria since 2014, mostly in Idlib. A February 2017 U.S. drone strike in Idlib killed the deputy leader of Al Qaeda, and a U.S. strike on an Al Qaeda training camp in Idlib the previous month killed more than 100 Al Qaeda fighters.30

In addition to HTS, the intelligence community's 2019 worldwide threat assessment also referenced another Al Qaeda-linked group in Syria known as Hurras al Din ("Guardians of Religion"). While HTS and Hurras al Din have occasionally clashed in Idlib, some analysts have assessed that the two groups "serve different functions that equally serve al-Qa`ida's established objectives: one appeals to hardened jihadis with an uncompromising doctrine focused on jihad beyond Syria and one appeals to those focused on the Syrian war."31 In February 2019, the two groups signed an accord pledging broader cooperation.32

Risk of Escalation

The 2019 expansion of jihadist groups in Idlib has raised concern about the potential for renewed Syrian and/or Russian operations in the area. In March 2019, Syrian and Russian strikes in Idlib reportedly intensified to their highest level in months.33 U.N. officials have described Idlib as a "dumping ground" for fighters and civilians—including an estimated 1 million children—evacuated or displaced from formerly opposition-held areas in other parts of the country. U.N. officials have warned that a mass assault on Idlib could result in "the biggest humanitarian catastrophe we've seen for decades."34

Turkish Operations in Northern Syria35

Turkey has maintained a military presence in northern Syria since 2016, and currently has forces deployed in Aleppo and Idlib provinces. Turkish forces partner with local Arab militias and have conducted border operations against the Islamic State and other jihadist fighters, while also targeting Syrian Kurdish forces.

President Trump has stated that Turkey could play a larger role in countering the Islamic State in Syria,36 although it is unclear to what extent U.S. and Turkish objectives overlap. Turkish officials have openly stated that their objectives are not limited to IS militants, and that they also intend to expand military operations against Kurdish forces—including those that have been allied with the United States as part of the counter-IS campaign.37 It is unclear to what extent Ankara is prepared to launch counter-IS operations in parts of Syria not adjacent to Turkey's border. U.S. military officials have noted that Turkey has not participated in ground operations against the Islamic State in Syria since 2017, and that Turkish forces have not participated in the fight against the Islamic State in the Middle Euphrates River Valley (MERV), which is roughly 230 miles away from the Turkish border.38 Turkish officials have requested U.S. air and logistical support for their potential operations, despite the two countries' different stances on the YPG.39

In January 2019, President Trump proposed the creation of a 20-mile deep "safe zone" on the Syria side of the border.40 Secretary of State Mike Pompeo later said that the U.S. "twin aims" are to make sure that those who helped take down the IS caliphate have security, and to prevent terrorists from attacking Turkey out of Syria.41 It is unclear who would enforce such a zone. Some sources suggest that U.S. officials favor having a Western coalition patrol any kind of buffer zone inside the Syrian border, with some U.S. support, while Turkey wants its forces together with allied Syrian opposition partners to take that role.42 Kurdish representatives have said that a safe zone must be guaranteed by international forces.43

Israeli Strikes in Syria

In September 2018, Israeli Intelligence Minister Israel Katz said, "in the last two years Israel has taken military action more than 200 times within Syria itself."44 Israeli strikes in Syria have mostly targeted locations and convoys near the Lebanese border associated with weapons shipments to Lebanese Hezbollah.45 However, in 2018, strikes widely attributed to Israel for the first time directly targeted Iranian facilities and personnel in Syria.46

In September 2018, Israel struck military targets in Syria's coastal province of Lattakia. A Syrian antiaircraft battery responding to the Israeli strikes downed a Russian military plane, killing 15 Russian personnel.47 An IDF spokesperson stated that Israeli jets were targeting "a facility of the Syrian Armed Forces from which systems to manufacture accurate and lethal weapons were about to be transferred on behalf of Iran to Hezbollah in Lebanon."48 The spokesperson added that the IDF and the Russian military maintain a deconfliction system in Syria, stating that the Russian plane was not in the area of operation during the Lattakia strike and blaming "extensive and inaccurate" Syrian antiaircraft fire for the incident. In response to the downing of their plane, Russian defense officials announced plans to provide an S-300 air defense system to Syria.

The expanding presence of Iranian and Iranian-backed personnel in Syria remains a consistent point of tension between Israel and Iran. In a rare acknowledgement, Israeli military officials in January 2019 confirmed strikes on Iranian military targets in Syria.49 Israel has accused Hezbollah of establishing a cell in Syrian-held areas of the Golan Heights, with the eventual goal of launching attacks into Israel.50

For additional information, see CRS In Focus IF10858, Iran and Israel: Tension Over Syria, by Carla E. Humud, Kenneth Katzman, and Jim Zanotti.

Political Negotiations

The Geneva Process

During 2020, Congress may further consider what, if any, revised defense and foreign assistance needs may be appropriate in connection with revised U.S. plans and any forthcoming changes to U.S. military deployments in Syria or in neighboring Iraq. Similarly, Members may consider how, if at all, Congress should increase, decrease, or reallocate defense, humanitarian, and stabilization resources for FY2021 and what, if any, new or revised oversight mechanisms ought to be employed. Specific issues for congressional consideration could include the following. U.S. forces have operated inside Syria since 2015 pursuant to the 2001 and 2002 Authorizations for Use of Military Force (AUMF),4 despite ongoing debate about the applicability of these authorizations to current operations in Syria.5 In December 2018, President Trump declared the Islamic State "defeated," raising questions about the authorities underlying a continued U.S. military presence in Syria. Defense and State Department officials continue to highlight the ongoing threat posed by the Islamic State, including to the U.S. homeland.6 Islamic State attacks continue in areas of eastern Syria, and oversight reporting suggests that Administration officials believe the group could resurge if military pressure on its remnants lessens.7 Nevertheless, some observers have argued that some U.S. military outposts in Syria (such as the U.S. garrison at At Tanf) appear primarily designed to stem the flow of Iranian-backed militias into Syria.8 Following the October 2019 Turkish incursion into northern Syria, the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) sought protection from the Asad government. U.S. Special Representative for Syria Engagement and the Special Envoy to the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS Ambassador James Jeffrey stated that the SDF and the Asad government reached "an agreement in some areas to coordinate."9 In December 2019, senior U.S. military officials acknowledged "dialogue" between the SDF and the Syrian military, but testified that U.S. forces continue to conduct combined operations with the SDF.10 U.S. officials have not publicly elaborated on the scale of coordination and/or dialogue between the Syrian military and the SDF, or on how this may impact U.S. interactions with, or funding for, the group. Who are the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)? Since 2014, U.S. armed forces have partnered with a Kurdish militia known as the People's Protection Units (YPG) to counter the Islamic State in Syria. In 2015, the YPG joined with other Syrian groups to form the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), comprising the SDF's leading component. Turkey considers the YPG to be the Syrian branch of the PKK (Kurdistan Workers' Party), a U.S.-designated terror group that has waged a decades-long insurgency in Turkey. Ankara has strongly objected to U.S. cooperation with the SDF. U.S. officials have acknowledged YPG-PKK ties, but generally consider the two groups distinct.11 The Syrian Arab Coalition. Roughly 50 percent of the SDF is composed of ethnic Arab forces, according to U.S. officials;12 this component sometimes is referred to as the Syrian Arab Coalition (SAC). In 2018, the U.S. military assessed that the SAC probably is unable to conduct counter-IS operations on its own without the support of the SDF's primary component, the YPG.13 In 2020, the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) described the SAC as "a patchwork of Arab tribal militias, military councils, and former opposition groups recruited by the YPG initially as a 'symbolic' move to help attract western support and training."14 Syrian government forces, with the support of Russia, have expanded their operations and presence in some areas of eastern Syria evacuated by U.S., Coalition, and SDF forces in 2019. The expanded presence of Syrian government forces in these areas may increase the potential for interactions between remaining U.S. personnel and Syrian or Russian forces, with uncertain implications for force protection and potential conflict. The Syrian government continues to refer to U.S. forces as occupiers and has warned that "resistance" forces might target U.S. personnel.15 Syrian officials have specifically called for the United States to end what they describe as the "illegal" presence of U.S. forces at Syrian oilfields.16 The Defense Department has stated that U.S. forces in Syria maintain "the inherent right to self-defense against any threat, includ[ing] while securing the oil fields."17 President Trump has stated that, "we may have to fight for the oil. It's okay. Maybe somebody else wants the oil, in which case they have a hell of a fight."18 Vice President Pence has stated that U.S. troops in troops in Syria will "secure the oil fields so that they don't fall into the hands of either ISIS or Iran or the Syrian regime."19 In February 2020, pro-regime forces manning a checkpoint in Qamishli opened fire on Coalition forces conducting a patrol; no Coalition injuries were reported.20 In early 2020, media reports highlighted increasingly frequent "standoffs" between U.S. and Russian personnel along highways in northeast Syria.21 U.S. officials have described these incidents as occurring along a road that is shared by U.S., Russian, and Syrian forces operating in adjacent areas of the northeast, particularly around Qamishli.22 Ambassador Jeffrey has stated that, on a limited number of occasions, Russian personnel have "tried to come deep into the area where [the United States] and the SDF are patrolling, well inside the basic lines that we have sketched, not right along the borders. Those are the ones that worry me."23 CJTF-OIR has reported that "although established de-confliction procedures exist, both Russia and the United States have limited options for enforcement if a party violates protocols, which could lead to increased risk to force protection and the potential for unintended escalation or miscalculation."24 The FY2020 NDAA (P.L. 116-92) extends the Syria Train and Equip program's authority until the end of 2020, and modifies the program's purposes. Changes under Section 1222 of the act include Section 1224 of the act requires the president to identify or designate a senior-level coordinator responsible for the long-term disposition of IS members currently in SDF custody. The congressionally mandated Syria Study Group highlighted the lack of such a coordinator in its September 2019 final report. The FY2020 NDAA also incorporates the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act of 2019 (Title LXXIV). Section 7411 of the act requires the Secretary of the Treasury to make a determination within 180 days of enactment on whether the Central Bank of Syria is a financial institution of primary money laundering concern. If so, the Secretary would be required to impose one or more of the special measures described in Section 5318A(b) of title 31, United States Code, with respect to the Central Bank of Syria. Section 7412 directs the President to impose sanctions on any foreign person who the President determines is knowingly providing significant financial, material, or technological support to the government of Syria or to a foreign person operating in a military capacity inside Syria on behalf of the governments of Syria, Russia, or Iran. It also makes eligible for sanctions foreign persons who knowingly sell or provide (1) goods, services, technology, or information that significantly facilitates the maintenance or expansion of the government of Syria's domestic production of natural gas, petroleum, or petroleum products; (2) aircraft or spare aircraft parts that are used for military purposes in Syria in areas controlled by the Syrian government or associated forces;( 3) significant construction or engineering services to the government of Syria. Section 7413 requires the President to determine the areas of Syria controlled by the governments of Syria, Iran, and Russia, and to submit a strategy to deter foreign persons from entering into contracts related to reconstruction in those areas. The bill includes several suspension and waiver authorities for the President, including for nongovernmental organizations providing humanitarian assistance. Its provisions would expire five years after the date of enactment. The FY2020 State and Foreign Operations Appropriation Act (Division G of the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020, P.L. 116-94) contains several Syria-related provisions: The Department of Defense Appropriations Act, 2020 (Division A of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020, P.L. 116-93 ) makes $1.195 billion in the Counter ISIS Train and Equip Fund (CTEF) available to counter the Islamic State globally, including to provide training, equipment, logistics support, infrastructure repair, and sustainment to countries or irregular forces engaged in counter-IS activities. No specific amount is designated for Syria in the act, but the accompanying explanatory statement allocates $200 million for Syria programs, $100 million less than the Administration's request. Section 9019 states that no funds made available by the act may be used for the "introduction of United States armed or military forces into hostilities in Syria, into situations in Syria where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances, or into Syrian territory, airspace, or waters while equipped for combat." The October 2019 Turkish military incursion into northern Syria targeted Syrian Kurdish forces that had worked closely with the United States to secure the territorial defeat of ISIS. The same month, three bills were introduced that would each establish a special immigrant visa (SIV) program for certain Syrians27 who had worked with U.S. military forces or the U.S. government. These programs would provide a new avenue under the U.S. immigration system for eligible individuals to be considered for admission to the United States. Upon admission, these individuals would become U.S. lawful permanent residents. Although the particular criteria in the three proposed SIV programs differ, all three would require applicants to obtain a favorable recommendation regarding their work with the U.S. government and be determined to be admissible to United States, which requires clearance of background checks and security screening, among other screening. All three programs would be subject to annual numerical limits, which would apply to the principal applicants but not to their accompanying spouses or children. Syrian Allies Protection Act (S. 2625). Introduced by Senator Warner, the bill would authorize the Secretary of Homeland Security to provide special immigrant status to a Syrian national who had worked directly with U.S. military forces as a translator or in another role deemed "vital to the success of the United States military mission in Syria," as determined by the Secretary of Defense, for a period of at least six months between September 2014 and October 2019. Applicants would need to obtain a written recommendation from a general or flag officer. The SIV program would be capped at 250 principal applicants per fiscal year. Syrian Partner Protection Act (H.R. 4873). Introduced by Representative Crow, the bill would authorize the Secretary of Homeland Security to provide special immigrant status to a Syrian national or stateless person habitually residing in Syria who worked for or with the U.S. government in Syria "as an interpreter, translator, intelligence analyst, or in another sensitive and trusted capacity" for an aggregate period of not less than one year after January 2014. The individual's "service to United States efforts against the Islamic State" would need to be documented in a positive recommendation or evaluation. The SIV program, which would be temporary, would be capped at 4,000 principal applicants per year for five fiscal years. Promoting American National Security and Preventing the Resurgence of ISIS Act of 2019 (S. 2641). Section 203 of S. 2641, as reported by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, would authorize the Secretary of Homeland Security to provide special immigrant status to a Syrian or stateless Kurd habitually residing in Syria who is or was employed by or on behalf of the U.S. government "in a role that was vital to the success of the United States' Counter ISIS mission in Syria," as determined by the Secretary of State in consultation with the Secretary of Defense. The individual must have been so employed for a period of at least one year after January 2014 and must obtain a favorable written recommendation from a senior supervisor. In addition, the applicant must have experienced or must be "experiencing an ongoing serious threat as a consequence of the alien's employment by the United States Government." The SIV program would be capped at 400 principal applicants per fiscal year. The Syrian SIV programs proposed by these bills are generally modeled on the existing temporary SIV programs for Iraqis and Afghans who have worked for or on behalf of the U.S. government, although there are some key differences. For example, under both the Iraqi and Afghan SIV programs, the recommendation or evaluation (attesting to valuable service) that an applicant is required to submit must be accompanied by approval from the appropriate Chief of Mission. The Syrian SIV bills would not require applicants to obtain Chief of Mission approval, although S. 2641 would require an applicant's recommendation to be approved by a senior foreign service officer designated by the Secretary of State. S. 2641 is also the only one of the three bills to require an applicant to show that he or she has experienced or is experiencing a serious threat as a result of employment by the U.S. government; this is a requirement under both the Iraqi and Afghan SIV programs. In addition, all three Syrian SIV bills include provisions that do not have counterparts under the Iraqi and Afghan programs that would provide for the protection or relocation of applicants who are in imminent danger or whose lives or safety are at risk. Introduced in March 2019 by Representative Engel, the bill would state that it is the policy of the United States that U.S. foreign assistance made available for reconstruction or stabilization in Syria should only be used in a democratic Syria or in areas of Syria not controlled by the Asad government or aligned forces. Reconstruction and stabilization aid appropriated or otherwise available from FY2020 through FY2024 could not be provided "directly or indirectly" to areas under Syrian government control—as determined by the Secretary of State—unless the President certifies to Congress that the government of Syria has met a number of conditions. These include ceasing air strikes against civilians, releasing all political prisoners, allowing regular access to humanitarian assistance, fulfilling obligations under the Chemical Weapons Convention, permitting the safe and voluntary return of displaced persons, taking steps to establishing meaningful accountability for perpetrators of war crimes, and halting the development and deployment of ballistic and cruise missiles. The House passed an earlier version of the bill during the 115th Congress. By noting restrictions on U.S. aid provided "directly or indirectly," the bill also would limit U.S. funds that could flow into Syria via multilateral institutions and international organizations, including the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank. The bill would permit exceptions to the above restrictions on aid to government-held areas for humanitarian projects, "projects to be administered by local organizations that reflect the aims, needs, and priorities of local communities," and projects that meet basic human needs including drought relief; assistance to refugees, IDPs, and conflict victims; the distribution of food and medicine; and the provision of health services. On October 9, 2019, Turkey's military (and allied Syrian opposition groups) entered northeastern Syria in a military operation targeting Kurdish People's Protection Unit (YPG) forces. Known as Operation Peace Spring (OPS), the Turkish operation followed a call between President Trump and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. After the phone call, President Trump ordered a pullback of U.S. forces from the area of the anticipated Turkish incursion. (28 Special Forces Green Berets located along Turkey's initial "axis of advance" were withdrawn prior to the Turkish operation.)28 This drew accusations among many, including some Members of Congress, that the Administration had offered a tacit "green light," to the Turkish operation, a charge strongly denied by Administration officials who described the U.S. decision to withdraw forces as a matter of personnel safety.29 President Trump said in a statement, "The United States does not endorse this attack and has made it clear to Turkey that this operation is a bad idea."30

As of January 13, 2020 Source: CRS, using areas of influence data from IHS Conflict Monitor. Note: This map does not depict precisely or comprehensively all U.S. bases or operating locations in Syria. According to U.S. military sources, the Turkish operation "set in motion a series of actions that affected the Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) mission against the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS); the U.S. relationship with the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), the United States' most reliable partner in Syria; and the control of territory in northeastern Syria."31 Similarly, Ambassador Jeffrey testified that the Turkish incursion was launched despite U.S. objections, "undermining the D-ISIS campaign, risking endangering and displacing civilians, destroying critical civilian infrastructure, and threatening the security of the area. Turkey's military actions have precipitated a humanitarian crisis and set conditions for possible war crimes."32 Ultimate Turkish and YPG objectives regarding the areas in question remain unclear. Since late October, Turkish-led fighters have periodically skirmished against YPG or Syrian government forces in places outside the areas under nominal Turkish control.33 Turkish officials also have blamed Kurdish forces for car bomb and land mine attacks in Turkish-held areas, some of which have caused civilian casualties.34 As a result of the Turkish operation, SDF operations against the Islamic State were temporarily paused, as was U.S. training for the SDF in areas affected by the Turkish incursion.35 U.S. forces withdrew from outposts in northern Syria (including Manbij and Ayn Issa); Syrian and Russian forces moved in "to fill the void created by departing U.S. forces."36 The State Department also moved its Syria Transition Assistance Team personnel inside Syria (START-Forward) out of the country. In the same period, the SDF redoubled its dialogue with the Asad government and reached an agreement to coordinate in some areas. As of December 2019, U.S. military officials testified that, "[ ... ] we continue combined operations with the Syrian Democratic Forces in order to complete the enduring defeat of ISIS and prevent their reemergence."37 In March 2019, the Islamic State lost its final territorial stronghold in Syria, as a result of Coalition operations in partnership with the SDF. Since then, U.S. military officials have warned that the group is defeated but not eliminated, and that it continues to pose a significant threat to local and regional stability. A U.S. airstrike in October 2019 killed IS leader Abu Bakr al Baghdadi in Syria's northwest province of Idlib. Abu Ibrahim al-Hashemi al-Qurayshi was named as Baghdadi's successor; little is publicly known about him. CENTCOM Commander Gen. Kenneth McKenzie stated that while Baghdadi's death may cause a slight disruption to the Islamic State's activities, "ISIS is first and last an ideology, so we are under no illusions that it's going to go away just because we killed Baghdadi."38 President Trump's announcement in October 2019 that all U.S. forces would withdraw from northern Syria, triggered warnings about the potential for an IS resurgence. In January 2020, U.S. officials estimated that the Islamic State retained about 14,000-18,000 IS fighters active between Syria and Iraq—similar to estimates provided in mid-2019.39 The October 2019 OIG Inspector General Report on Operation Inherent Resolve stated that, "With SDF and Coalition operations against ISIS in Syria diminished, U.S. military, intelligence, and diplomatic agencies warned that ISIS was likely to exploit the reduction in counterterrorism pressure to reconstitute its operations in Syria."40 According to the report, the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) assessed that a reduction in counterterrorism pressure "will provide the group with time and space to expand its ability to conduct transnational attacks targeting the West."41 The withdrawal announcement has since been modified to allow for the continued deployment of roughly 600 U.S. forces to Syria. Prior to the Turkish incursion, U.S. and Coalition forces had been training and equipping the SDF and other partner forces to enable them to hold territory and conduct counterinsurgency operations against the Islamic State in northeast Syria. CJTF-OIR reported that as of the end of fourth quarter of FY2019, the SDF remained in need of additional personnel, training, and equipment to conduct counterinsurgency operations against the Islamic State. As noted above, in December 2019, Congress modified existing authorities for train and equip activities in Syria and appropriated an additional $200 million for related Syria programs. The capture of the final Islamic State stronghold in Syria in March 2019 led to the surrender of thousands of IS fighters, as well as their spouses and children. Since then, the SDF has retained custody of roughly 10,000 IS militants (including approximately 2,000 foreign fighters) at several makeshift prisons in northern Syria. Wives and children of IS fighters (some of whom also may be radicalized) are held at separate IDP camps. The largest of these is Al Hol, which houses about 66,000 individuals, 96% of whom are women or children.42 Media reports suggest that the Islamic State continues to operate and recruit within the camp.43 The SDF has stated that it is unable to assume long-term responsibility for IS detainees and their families, and the United States has urged countries to repatriate their citizens. To date, many countries have been reluctant to do so, citing concerns about their inability to prosecute or successfully monitor individuals who may have been radicalized. Some countries also have stripped IS fighters and/or family members of their citizenship. The security of facilities housing IS fighters and family members continues to be a significant concern. The Islamic State has urged its followers to free IS detainees, and U.S. military assessments have noted that the SDF is unable to provide more than "minimal security" at Al Hol.44 At the same time, humanitarian conditions within detention facilities such as Al Hol are dire. According to the Kurdish Red Crescent, at least 517 people, mostly children, died inside the Al Hol camp in 2019, due to malnutrition, inadequate healthcare for newborns, and hypothermia.45 The ongoing military offensive in Idlib has generated what U.N. officials have described as a "humanitarian catastrophe,"48 with over half a million people having fled their homes between 1 December 2019 and 2 February 2020 as a result of ongoing hostilities.49 An estimated 400,000 people previously had been displaced from southern Idlib and northern Hama between April and August 2019.50 The U.N. has estimated that 80 percent of those recently displaced are women and children.51 In February 2019, the two groups signed an accord pledging broader cooperation.56 In June and August of 2019, CENTCOM announced two U.S. strikes against "al-Qaida in Syria (AQ-S) leadership" in Aleppo and Idlib provinces, respectively.57 The second strike targeted AQ-S leaders responsible for attacks threatening U.S. citizens, our partners, and innocent civilians. [ ... ] Northwest Syria remains a safe haven where AQ-S leaders actively coordinate terrorist activities throughout the region and in the West.58 In September 2019, the U.S. government named Hurras al Din as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist entity pursuant to Executive Order 13224, as amended by Executive Order 13886. In October 2019, Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al Baghdadi was killed in a U.S. strike in the village of Barisha in northern Idlib province. Baghdadi appears to have sought protection from the AQ-affiliated Hurras al Din—dominant in that area of Idlib—despite the fact that other senior IS and AQ leaders have been rivals and their forces have, at times, been adversaries.59 Prior to the Islamic State's territorial defeat in March 2019, some IS members had requested safe passage to Idlib from SDF and coalition forces in exchange for the return of captured SDF personnel.60 Since 2012, the Syrian government and opposition have participated in U.N.-brokered negotiations under the framework of the Geneva Communiqué. Endorsed by both the United States and Russia, the Geneva Communiqué calls for the establishment of a transitional governing body with full executive powers. According to the document, such a government "could include members of the present government and the opposition and other groups and shall be formed on the basis of mutual consent."61 The document does not discuss the future of Asad. Since 2012, the Syrian government and opposition have participated in U.N.-brokered negotiations under the framework of the Geneva Communiqué. Endorsed by both the United States and Russia, the Geneva Communiqué calls for the establishment of a transitional governing body with full executive powers. According to the document, such a government "could include members of the present government and the opposition and other groups and shall be formed on the basis of mutual consent."51

Issues for Congress

Prior to the 2019 Turkish military incursion and U.S. withdrawal decisions, the 116th Congress had been considering the Administration's FY2020 requests for defense and foreign aid appropriations, which presumed continued counterterrorism, train and equip, and humanitarian operations in Syria. Members debated legislative proposals that would have extended and amended related authorities and made additional funding available to continue U.S. efforts, including stabilization programs. Following President Trump's withdrawal and redeployment decisions, Congress enacted revisions to the underlying authority for U.S. military train and equip efforts in Syria and appropriated additional funds to continue related operations.

U.S. military operations and authorities

Future of U.S.-SDF Partnership

Security of U.S. Forces in Syria

The Syria Civilian Protection Act of 2019

Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-93)

No Assistance for Assad Act (H.R. 1706)

Islamic State Detainees

Al Qaeda in Idlib

U.S. officials in 2017 described Idlib as "the largest Al Qaeda safe haven since 9/11,"52 and Administration officials continue to describe the province as "a major terrorist concern."53 U.S. initiatives in Idlib aimed at countering violent extremism (CVE) were halted in May 2018 as part of a broader withdrawal of U.S. assistance to northwest Syria.54 In January 2019, the Al Qaeda-linked group Haya't Tahrir al Sham (HTS) seized large areas of Idlib province from rival armed groups. In early 2019, the U.S. intelligence community also highlighted another Al Qaeda-linked group in Syria known as Hurras al Din ("Guardians of Religion", HD). While HTS and HD have occasionally clashed in Idlib, some analysts have assessed that the two groups "serve different functions that equally serve al-Qa`ida's established objectives: one [HD] appeals to hardened jihadis with an uncompromising doctrine focused on jihad beyond Syria and one [HTS] appeals to those focused on the Syrian war."55

Al Qaeda-Islamic State Links in Idlib

The document does not discuss the future of Asad.

Subsequent negotiations have made little progress, as both sides have adopted differing interpretations of the agreement. The opposition has said that any transitional government must exclude Asad. The Syrian government maintains that Asad was reelected (by referendum) in 2014,52 and notes that the Geneva Communiqué does not explicitly require him to step down. In the Syrian government's view, a transitional government can be achieved by simply expanding the existing government to include members of the opposition. Asad has also stated that a political transition cannot occur until "terrorism" has been defeated, continues to state that a comprehensive solution to the current conflict must begin by "striking at terrorism" (which his government defines broadly to include all armedmost opposition groups.

As part of the Geneva Process, U.N. Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 2254, adopted in 2015, endorsed a "road map" for a political settlement in Syria, including the drafting of a new constitution and the administration of U.N.-supervised elections. U.S. officials continue to stress that a political solution to the conflict must be based on the principles of UNSCR 2254.

The last formal round of Geneva talks, facilitated by then-U.N. Special Envoy for Syria Staffan de Mistura, closed in late January 2018. While the United States continues to call for a political settlement to the conflict, the U.S. intelligence community since 2018 has assessed that Asad is "unlikely to negotiate himself from power"5364 or make meaningful concession to the opposition:

The regime's momentum, combined with continued support from Russia and Iran, almost certainly has given Syrian President Bashar al-Asad little incentive to make anything more than token concessions to the opposition or to adhere to UN resolutions on constitutional changes that Asad perceives would hurt his regime.5465

In October 2019, Ambassador Jeffrey testified that the United States continues to support U.N.-led political negotiations in Geneva pursuant to UNSCR 2254.66 State Department officials have identified three points of leverage that the United States and its foreign partners could use to encourage the Asad regime to accept a political settlement: the withholding of reconstruction assistance, barring Syria's re-entry into the Arab League, and refusing to restore diplomatic relations with Damascus.67

The United States has repeatedly expressed its view that Geneva should be the sole forum for a political settlement to the Syria conflict, possibly reflecting concern regarding the Russia-led Astana Process (see below). However, the United States supported de Mistura's efforts throughout 2018efforts by the U.N. Special Envoy for Syria to stand up a Syrian Constitutional Committee, an initiative originally stemming from the Russian-led Sochi conference in January 2018 (see below).55 De Mistura resigned in December 2018, and was succeeded by veteran Norwegian diplomat Geir Pederson. As of early 2019, Pederson has continued De Mistura's efforts to convene a constitutional committee.68 In December 2018, Norwegian diplomat Geir Pederson succeeded Staffan de Mistura as U.N. Special Envoy for Syria. In September 2019, Pederson announced the successful formation of the Syrian Constitutional Committee. Pederson stated that the committee would be facilitated by the United Nations in Geneva (see "Constitutional Committee," below).69

The Astana Process

Since January 2017, peace talks hosted by Russia, Iran, and Turkey have convened in the Kazakh capital of Astana. These talks were the forum through which three "de-escalation areas" were established—two of which have since been retaken by Syrian military forces. The United States is not a party to the Astana talks but has attended as an observer delegation.

Russia has played a leading role in the Astana process, which some have described as an alternate track to the Geneva process. The United States has strongly opposed the prospect of Astana superseding Geneva. Following the release of the Joint Statement by President Trump and Russian President Putin on November 11, 2017 (in which the two presidents confirmed that a political solution to the conflict must be forged through the Geneva process pursuant to UNSCR 2254), U.S. officials stated that

We have started to see signs that the Russians and the regime wanted to draw the political process away from Geneva to a format that might be easier for the regime to manipulate. Today makes clear and the [Joint Statement] makes clear that 2254 and Geneva remains the exclusive platform for the political process.56

In January 2018, Russia hosted a "Syrian People's Congress" in Sochi, in which participants agreed to form a constitutional committee comprising delegates from the Syrian government and the opposition "for drafting of a constitutional reform," in accordance with UNSCR 2254.71 The conference was boycotted by most Syrian opposition groups and included mainly delegates friendly to the Asad government.72 The statement noted that final agreement regarding the mandate, rules of procedure, and selection criteria for delegates would be reached under the framework of the Geneva process.

Constitutional Committee. The committee, whose formation took nearly two years, consists of 150 delegates—50 each representing the Syrian government and the Syrian opposition, as well as a "middle third" list comprising 50 Syrian-national delegates selected by the U.N. from among the country's legal experts, civil society members, political independents, and tribal leaders. The committee includes a limited number of Kurds but does not include representatives from the YPG, the SDF or the SDF's political wing—the Syrian Democratic Council, SDC—which administer large areas of northern Syria.73 The committee met for the first time in Geneva in October 2019, where it formed a smaller 45-member Constitution-drafting group. The current Syrian constitution was approved in a February 2012 referendum, replacing the constitution that had been in place since 1973.

Humanitarian Situation As of early 2020, more than 11.1 million people in Syria are in need of humanitarian assistance, 6.2 million Syrians are internally displaced, and an additional 5.6 million Syrians are registered with the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) as refugees in nearby countries.74 The U.N. Secretary-General regularly reports to the Security Council on humanitarian issues and challenges in and related to Syria pursuant to Resolutions 2139 (2014), 2165 (2014), 2191 (2014), 2258 (2015), 2332 (2016), 2393 (2017), 2401 (2018), and 2449 (2018).75 Cross-Border Aid EndangeredThe Syrian government has long opposed the provision of humanitarian assistance across Syria's border and across internal lines of conflict outside of channels under Syrian government control. Successive U.N. Security Council resolutions have nevertheless authorized the provision of such assistance. UNSCR 2449 authorized cross-border and cross-line humanitarian assistance until January 10, 2020. Russia and China abstained in the December 2018 vote that approved the resolution, and the Russian representative argued at the time that "new realities ... demand that [the mandate] be rejiggered with the ultimate goal of being gradually but inevitably removed."76

On December 20, 2019, Russia and China vetoed a U.N. Security Council resolution that would have renewed the authorization enabling U.N. agencies to deliver aid into Syria from two points in Turkey and one in Iraq for another 12 months. U.N. officials warned that without cross-border operations, "we would see an immediate end of aid supporting millions of civilians."77 On January 10, the Security Council approved Resolution 2504, re-authorizing cross border aid into Syria via two of the four existing border crossings—Bab al Salam and Bab al Hawa, both in Turkey—for a period of six months (rather than one year). The continued use of border crossings at Ramtha (Jordan) and Al Yarubiyah (Iraq) was not authorized.78

U.S. Humanitarian FundingThe United States is the largest donor of humanitarian assistance to the Syria crisis, drawing from existing funding from global humanitarian accounts and some reprogrammed funding.79 As of December 2019, total U.S. humanitarian assistance for the Syria crisis since 2011 had reached nearly $10.5 billion.80 These funds have gone towards meeting humanitarian needs inside Syria, as well as towards support for communities in Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey, Iraq, and Egypt that host Syrian refugees.81

The 11th round of Astana talks was held in November 2018. In February 2019, the presidents of Russia, Iran, and Turkey held a trilateral summit at the Russian Black Sea resort of Sochi to discuss the future of Idlib, anticipated changes to the U.S. military presence in Syria, and how to move forward on the formation of a constitutional committee.57

Constitutional Committee. Despite the November 2017 agreement, Russia persisted in its attempts to host, alongside Iran and Turkey, a "Syrian People's Congress" in Sochi, intended to bring together Syrian government and various opposition forces to negotiate a postwar settlement. The conference, held in January 2018, was boycotted by most Syrian opposition groups and included mainly delegates friendly to the Asad government.58 Participants agreed to form a constitutional committee comprising delegates from the Syrian government and the opposition "for drafting of a constitutional reform," in accordance with UNSCR 2254.59 The statement noted that final agreement regarding the mandate, rules of procedure, and selection criteria for delegates would be reached under the framework of the Geneva process. The United States supports the formation of the committee under U.N. auspices, but has emphasized that "the United Nations must be given a free hand to determine the composition of the committee, its scope of work, and schedule."60

Following the 2018 Sochi Conference, de Mistura sought to reach consensus among the parties regarding delegates for the constitutional committee. The committee's membership is to be divided in equal thirds between delegates from the Syrian government, Syrian opposition, and delegates selected by the U.N. comprising Syrian experts, civil society, independents, tribal leaders, and women. The sticking point remains this latter, U.N.-selected group, known as the "middle third list."61 The Syrian government has objected to the U.N.'s role in naming delegates to the list, describing the constitution as "a highly sensitive matter of national sovereignty."62

Kurdish Outreach to Asad Government

In July 2018, the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC), the political wing of the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), opened formal discussions with the Syrian government.63 The Kurdish-held areas in northern Syria, comprising about a quarter of the country, are the largest remaining areas outside of Syrian government control. Asad has stated that his government intends to recover these areas, whether by negotiations or military force.64 In early 2019, the U.S. intelligence community also assessed that the Asad government was "likely to focus on reasserting control over Kurdish-held areas."65