The International Emergency Economic Powers Act: Origins, Evolution, and Use

Changes from March 20, 2019 to August 1, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

The International Emergency Economic Powers Act: Origins, Evolution, and Use

Contents

- Introduction

- Origins

- The First World War and the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA)

- The Expansion of TWEA

- Pushing Back Against Executive Discretion

- Enactment of the National Emergencies Act and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act

- IEEPA's Statute, its Use, and Judicial Interpretation

- IEEPA's Statute

- Amendments to IEEPA

- The

Berman Amendment and Informational MaterialsInformational Materials Amendments to IEEPA

- USA PATRIOT Act Amendments to IEEPA

- IEEPA Trends

- Presidential Emergency Use

- Congressional Nonemergency Use and Retroactive Approval

- Current Uses of IEEPA

- Use of Assets Frozen under IEEPA

- Presidential Use of Foreign Assets Frozen under IEEPA

- Congressionally Mandated Use of Frozen Foreign Assets and Proceeds of Sanctions

- Judicial Interpretation of IEEPA

- Dames & Moore v. Regan

- Separation of Powers—Non-Delegation Doctrine

- Separation of Powers—Legislative Veto

- Fifth Amendment "Takings" Clause

- Fifth Amendment "Due Process" Clause

- First Amendment Challenges

- Use of IEEPA to Continue Enforcing the Export Administration Act (EAA)

- Issues and Options for Congress

- Delegation of Authority under IEEPA

- Definition of "National Emergency" and "Unusual and Extraordinary Threat"

- Scope of the Authority

- Terminating National Emergencies or IEEPA Authorities

- The Status Quo

- The Export Control Reform Act of 2018

Figures

Tables

Appendixes

Summary

The International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) provides the President broad authority to regulate a variety of economic transactions following a declaration of national emergency. IEEPA, like the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA) from which it branched, sits at the center of the modern U.S. sanctions regime. Changes in the use of IEEPA powers since the act's enactment in 1977 have caused some to question whether the statute's oversight provisions are robust enough given the sweeping economic powers it confers upon the President upon declaration of a state of emergency.

Over the course of the twentieth century, Congress delegated increasing amounts of emergency power to the President by statute. The Trading with the Enemy Act was one such statute. Congress passed TWEA in 1917 to regulate international transactions with enemy powers following the U.S. entry into the First World War. Congress expanded the act during the 1930s to allow the President to declare a national emergency in times of peace and assume sweeping powers over both domestic and international transactions. Between 1945 and the early 1970s, TWEA became a critically importantthe central means to impose sanctions as part of U.S. Cold War strategy. Presidents used TWEA to block international financial transactions, seize U.S.-based assets held by foreign nationals, restrict exports, modify regulations to deter the hoarding of gold, limit foreign direct investment in U.S. companies, and impose tariffs on all imports into the United States.

Following committee investigations that discovered that the United States had been in a state of emergency for more than 40 years, Congress passed the National Emergencies Act (NEA) in 1976 and IEEPA in 1977. The pair of statutes placed new limits on presidential emergency powers. Both included reporting requirements to increase transparency and track costs, and the NEA required the President to annually assess and extend, if appropriate, thean emergency. However, some experts argue that the renewal process has become pro forma. The NEA also afforded Congress the means to terminate a national emergency by adopting a concurrent resolution in each chamber. A decision by the Supreme Court, in a landmark immigration case, however, found the use of concurrent resolutions to terminate an executive action unconstitutional. Congress amended the statute to require a joint resolution, significantly increasing the difficulty of terminating an emergency.

Like TWEA, IEEPA has become an important means to impose economic-based sanctions since its enactment; like TWEA, Presidents have frequently used IEEPA to restrict a variety of international transactions; and like TWEA, the subjects of the restrictions, the frequency of use, and the duration of emergencies have expanded over time. Initially, Presidents targeted foreign states or their governments. Over the years, however, presidential administrations have increasingly used IEEPA to target individuals, groups, and non-state actorsnon-state individuals and groups, such as terrorists and persons who engage in malicious cyber-enabled activities.

As of MarchAugust 1, 2019, Presidents had declared 5456 national emergencies invoking IEEPA, 2931 of which are still ongoing. Typically, national emergencies invoking IEEPA last nearly a decade, although some have lasted significantly longer---the first state of emergency declared under the NEA and IEEPA, which was declared in response to the taking of U.S. embassy staff as hostages by Iran in 1979, may soon enter its fifth decade.

IEEPA grants sweeping powers to the President to control economic transactions. Despite these broad powers, Congress has never attempted to terminate a national emergency invoking IEEPA. Instead, Congress has directed the President on numerous occasions to use IEEPA authorities to impose sanctions. Congress may want to consider whether IEEPA appropriately balances the need for swift action in a time of crisis with Congress' duty to oversee executive action. Congress may also want to consider IEEPA's role in implementing its influence in U.S. foreign policy and national security decision-making.

Introduction

The issue of executive discretion has been at the center of constitutional debates in liberal democracies throughout the twentieth century. HowSpecifically, the question of how to balance a commitment to the rule of law with the exigencies of modern political and economic crises has engagedbeen a consistent concern of legislators and scholars in the United States and around the world.1

The United States Constitution is silent on questionsthe question of emergency power. As such, over the past two centuries, Congress and the President have answered those questionsthat question in varied and often ad hoc ways. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the answer was often for the President to act without congressional approval in a time of crisis, knowingly risking impeachment and personal civil liability.2 Congress claimed primacy over emergency action and would decide subsequently to either ratify the President's actions through legislation or indemnify the President for any civil liability.3

By the twentieth century, a new pattern had begun to emerge. Instead of retroactively judging an executive's extraordinary actions in a time of emergency, Congress created statutory bases permitting the President to declare a state of emergency and make use of extraordinary delegated powers.4 The expanding delegation of emergency powers to the executive and the increase of governing via emergency power by the executive has beenwas a common trajectory among twentieth-century liberal democracies.5 As innovation has quickened the pace of social change and global crises, some legislatures have felt compelled to delegate to the executivetheir executives, who traditional political theorists assumed could operate with greater "dispatch" than deliberate,the more deliberate and future-oriented legislatures.6 Whether such actions subvert the rule of law or are a standard feature of healthy modern constitutional orders has been a subject of extensive debate.7

The International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) is one such example of a twentieth-century delegation of emergency authority.8 One of 123 emergency statutes under the umbrella of the National Emergencies Act (NEA),9 IEEPA grants the President extensive power to regulate a variety of economic transactions during a state of national emergency. Congress enacted IEEPA in 1977 to rein in the expansive emergency economic powers that it had been delegated to the President under the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA). Nevertheless, some scholars argue that judicial and legislative actions subsequent to IEEPA's enactment have made it, like TWEA, a source of expansive and unchecked executive authority in the economic realm.10 Others, however, argue that Presidents often use IEEPA toIEEPA is a useful tool for Presidents to quickly implement the will of Congress either as directed by law or as encouraged by congressional activity.11

Until recently, there has been little congressional discussion of modifying either IEEPA or its umbrella statute, the NEA. Recent presidential actions, however, have drawn attention to presidential emergency powers under the NEA of which IEEPA is the most frequently used. Should Congress consider changing IEEPA, there are two issues that Congress may wish to address. The first pertains to how Congress has delegated its authority under IEEPA and its umbrella statute, the NEA. The second pertains to choices made in the Export Control Reform Act of 2018.

Origins

The First World War and the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA)

The First World War (1914-19181919) saw an unprecedented degree of economic mobilization. The executive departments of European governments began to regulate their economies with or without the support of their legislatures. The United States, in contrast, was in a privileged position relative to its allies in Europe. Separated by an ocean from Germany and Austria-Hungary, the United States was never under substantial threat of invasion. Rather than relying on the inherent powers of the presidency, or acting unconstitutionally and waiting for congressional ratification, President Wilson sought explicit pre-authorization for expansive new powers to meet the global crisis.12 Between 1916 and the end of 1917, Congress passed 22 statutes empowering the President to take control of private property for public use during the war. These statutes gave the President broad authority to control railroads, shipyards, cars, telegraph and telephone systems, water systems, and many other sectors of the American economy.13

TWEA was one of those 22 statutes.14 It granted to the executive an extraordinary degree of control over international trade, investment, migration, and communications between the United States and its enemies. TWEA defined "enemy" broadly and included "any individual, partnership, or other body of individuals [including corporations], of any nationality, resident within the territory ... of any nation with which the United States is at war, or resident outside of the United States and doing business within such a territory ...."15 The first four sections of the act granted the President extensive powers to limit trading or communication with, or transporting enemies (or their allies) of the United States.16 These sections also empowered the President to censor foreign communications and place extensive restrictions on enemy insurance or reinsurance companies.17

It was Section 5(b) of TWEA, however, that would form one of the central bases of presidential emergency economic power in the twentieth century. Section 5(b), as originally enacted, states:

That the President may investigate, regulate, or prohibit, under such rules and regulations as he may prescribe, by means of licenses or otherwise, any transactions in foreign exchange, export or earmarkings of gold or silver coin or bullion or currency, transfers of credit in any form (other than credits relating solely to transactions to be executed wholly within the United States), and transfers of evidences of indebtedness or of the ownership of property between the United States and any foreign country, whether enemy, ally of enemy or otherwise, or between residents of one or more foreign countries, by any person within the United States; and he may require any such person engaged in any such transaction to furnish, under oath, complete information relative thereto, including the production of any books of account, contracts, letters or other papers, in connection therewith in the custody or control of such person, either before or after such transaction is completed.18

The statute gave the President exceptional control over private international economic transactions in times of war.19 While Congress terminated many of the war powers in 1921, TWEA was specifically exempted because the U.S. Government had yet to dispose of a large amount of alien property in its custody.20

The Expansion of TWEA

The Great Depression, a massive global economic downturn that began in 1929, presented a challenge to liberal democracies in Europe and the Americas. To deal with the complexities presented by the crisis, nearly all such democracies began delegating discretionary authority to their executives to a degree that had only previously been done in times of war.21 The U.S. Congress responded, in part, by dramatically expanding the scope of TWEA, delegating to the President the power to declare states of emergency in peacetime and assume expansive domestic economic powers.

Such a delegation was made possible by analogizing economic crises to war. In public speeches about the crisis, President Franklin D. Roosevelt asserted that the Depression was to be "attacked," "fought against," "mobilized for," and "combatted" by "great arm[ies] of people."22 The economic mobilization of the First World War had blurred the lines between the executive's military and economic powers. As the Depression was likened to "armed strife"23 and declared to be "an emergency more serious than war"24 by a Justice of the Supreme Court, it became routine to use emergency economic legislation enacted in wartime as the basis for extraordinary economic authority in peacetime.25

As the Depression entered its third year, the newly-elected President Roosevelt sought from Congressasked Congress for "broad Executive power to wage a war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe."26 In his first act as President, Roosevelt proclaimed a bank holiday, suspending all transactions at all banking institutions located in the United States and its territories for four days.27 In his proclamation, Roosevelt claimed to have authority to declare the holiday under Section 5(b) of TWEA.28 However, because the United States was not in a state of war and the suspended transactions were primarily domestic, the President's authority to issue such an order was dubious.29

Despite the tenuous legality, Congress ratified Roosevelt's actions by passing the Emergency Banking Relief Act three days after his proclamation.30 The act amended Section 5(b) of TWEA to read:

During time of war or during any other period of national emergency declared by the President, the President may, through any agency that he may designate, or otherwise, investigate, regulate, or prohibit....31

This amendment gave the President the authority to declare that a national emergency existed and assume extensive controls over the national economy previously only available in times of war. By 1934, Roosevelt had used these extensive new powers to regulate "Every transaction in foreign exchange, transfer of credit between any banking institution within the United States and any banking institution outside of the United States."32

With America's entry into the Second World War in 1941, Congress again amended TWEA to grant the President extensive powers over the disposition of private property, adding the so-called "vesting" power, which authorized the permanent seizure of property. Now in its most expansive form, TWEA authorized the President to declare a national emergency and, in so doing, to regulate foreign exchange, domestic banking, possession of precious metals, and property in which any foreign country or foreign national had an interest.33

The Second World War ended in 1945. Following the conflict, the allied powers constructed institutions and signed agreements designed to keep the peace and to liberalize world trade. However, the United States did not immediately resume a peacetime posture with respect to emergency powers. Instead, the onset of the Cold War rationalized the continued use of TWEA and other emergency powers outside the context of a declared war.34 Over the next several decades, Presidents declared four national emergencies under Section 5(b) of TWEA and assumed expansive authority over economic transactions in the postwar period.35

During the Cold War, economic sanctions became an increasingly popular foreign policy and national security tool, and TWEA was a prominent source of presidential authority to use the tool. In 1950, President Harry S. Truman declared a national emergency, citing TWEA, to impose economic sanctions on North Korea and China.3536 Subsequent Presidents referenced that national emergency as authority for imposing sanctions on Vietnam, Cuba, and Cambodia.3637 Truman likewise used Section 5(b) of TWEA to maintain regulations on foreign exchange, transfers of credit, and the export of coin and currency that had been in place since the early 1930s.3738 Presidents Richard M. Nixon and Gerald R. Ford invoked TWEA to continue export controls established under the Export Administration Act when the act expired.38

TWEA was also a prominent instrument of postwar presidential monetary policy. Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy used TWEA and the national emergency declared by President Roosevelt in 1933 to maintain and modify regulations controlling the hoarding and export of gold.3940 In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson explicitly used Truman's 1950 declaration of emergency under Section 5(b) of TWEA to limit direct foreign investment by U.S. companies in an effort to strengthen the balance of payments position of the United States after the devaluation of the pound sterling by the United Kingdom.4041 In 1971, after President Nixon endedsuspended the convertibility of the U.S. dollar to gold, effectively ending the postwar monetary order, he made use of Section 5(b) of TWEA to declare a state of emergency and place a 10% ad valorem supplemental duty on all dutiable goods entering the United States.4142

The reliance by the executive on the powers granted by Section 5(b) of TWEA meant that postwar sanctions regimes and significant parts of U.S. international monetary policy relied on continued states of emergency for their operation.

Pushing Back Against Executive Discretion

By the mid-1970s, in the wake offollowing U.S. military involvement in Vietnam, revelations of domestic spying, assassinations of foreign political leaders, the Watergate break-in, and other related abuses of power, Congress increasingly focused on checking the executive branch. The Senate formed a bipartisan special committee chaired by Senators Frank Church and Charles Mathias to reevaluate the expansive delegations of emergency authority to the President.4243 The special committee issued a report surveying the President's emergency powers in which it asserted that the United States had technically "been in a state of national emergency since March 9, 1933" and that there were four distinct declarations of national emergency in effect.4344 The report also noted that the United States had "on the books at least 470 significant emergency statutes without time limitations delegating to the Executive extensive discretionary powers, ordinarily exercised by the Legislature, which affect the lives of American citizens in a host of all-encompassing ways."4445

In the course of itsthe Committee's investigations, Senator Mathias, a committee co-chair, noted, "A majority of the people of the United States have lived all of their lives under emergency government." Senator Church, the other co-chair, said the central question before the committee was "whether it [was] possible for a democratic government such as ours to exist under its present Constitution and system of three separate branches equal in power under a continued state of emergency."4546

Among the more controversial statutes highlighted by the committee was TWEA. In 1977, during the House markup of a bill revising TWEA, Representative Jonathan Bingham, Chairperson of the House International Relations Committee's Subcommittee on Economic Policy, described TWEA as conferring "on the President what could have been dictatorial powers that he could have used without any restraint by Congress."4647 According to the Department of Justice, TWEA granted the President four major groups of powers in a time of war or other national emergency:

(a) Regulatory powers with respect to foreign exchange, banking transfers, coin, bullion, currency, and securities;

(b) Regulatory powers with respect to "any property in which any foreign country or a national thereof has any interest";

(c) The power to vest "any property or interest of any foreign country or national thereof"; and

(d) The powers to hold, use, administer, liquidate, sell, or otherwise deal with "such interest or property" in the interest of and for the benefit of the United States.47

The House report on the reform legislation called TWEA "essentially an unlimited grant of authority for the President to exercise, at his discretion, broad powers in both the domestic and international economic arena, without congressional review."4849 The criticisms of TWEA centered on the following:

(a) It required no consultation or reports to Congress with regard to the use of powers or the declaration of a national emergency.

(b) It set no time limits on a state of emergency, no mechanism for congressional review, and no way for Congress to terminate it.

(c) It stated no limits on the scope of TWEA's economic powers and the circumstances under which such authority could be used.

(d) The actions taken under the authority of TWEA were rarely related to the circumstances in which the national emergency was declared.49

In testimony before the House Committee on International Relations, Professor Harold G. Maier, a noted legal scholar, summed up the development and the main criticisms of TWEA:

Section 5(b)'s effect is no longer confined to "emergency situations" in the sense of existing imminent danger. The continuing retroactive approval, either explicit or implicit, by Congress of broad executive interpretations of the scope of powers which it confers has converted the section into a general grant of legislative authority to the President…"50

Enactment of the National Emergencies Act and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act

Congress's reforms to emergency powers under TWEA came in two acts. First, Congress enacted the National Emergencies Act (NEA) in 1976.5152 The NEA provided for the termination of all existing emergencies in 1978, except those making use of Section 5(b) of TWEA, and placed new restrictions on the manner of declaring and the duration of new states of emergency, including:

- Requiring the President to immediately transmit to Congress a notification of the declaration of national emergency.

- Requiring a biannual review whereby "each House of Congress shall meet to consider a vote on a concurrent [now joint, see below] resolution to determine whether that emergency shall be terminated."

- Authorizing Congress to terminate the national emergency through a privileged concurrent [now joint] resolution.

5253

Second, Congress tackled the thornier question of TWEA. Because the authorities granted by TWEA were heavily entwined with postwar international monetary policy and the use of sanctions in U.S. foreign policy, unwinding it was a difficult undertaking.5354 The exclusion of Section 5(b) reflected congressional interest in preserving existing regulations regarding foreign assets, foreign funds, and exports of strategic goods.5455 Similarly, establishing a means to continue existing uses of TWEA reflected congressional interest in "improving future use rather than remedying past abuses."55

The subcommittee charged with reforming TWEA spent more than a year preparing reports, including the first complete legislative history of TWEA, a tome that ran nearly 700 pages.5657 In the resulting legislation, Congress did three things. First, Congress amended TWEA so that it was, as originally intended, only applicable "during a time of war."5758 Second, Congress expanded the Export Administration Act to include powers that previously were authorized by reference to Section 5(b) of TWEA.5859 Finally, Congress wrote the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to confer "upon the President a new set of authorities for use in time of national emergency which are both more limited in scope than those of section 5(b) and subject to procedural limitations, including those of the [NEA]."59

The Report of the House Committee on International Relations summed up the nature of an "emergency" in their "new approach" to international emergency economic powers:

[G]iven the breadth of the authorities, and their availability at the President's discretion upon a declaration of a national emergency, their exercise should be subject to various substantive restrictions. The main one stems from a recognition that emergencies are by their nature rare and brief, and are not to be equated with normal ongoing problems. A national emergency should be declared and emergency authorities employed only with respect to a specific set of circumstances which constitute a real emergency, and for no other purpose. The emergency should be terminated in a timely manner when the factual state of emergency is over and not continued in effect for use in other circumstances. A state of national emergency should not be a normal state of affairs.60

IEEPA's Statute, its Use, and Judicial Interpretation

IEEPA's Statute

IEEPA, as currently amended, empowers the president to:

(A) investigate, regulate, or prohibit:

(i) any transactions in foreign exchange,

(ii) transfers of credit or payments between, by, through, or to any banking institution, to the extent that such transfers or payments involve any interest of any foreign country or national thereof,

(iii) the importing or exporting of currencies or securities; and

(B) investigate, block during the pendency of an investigation, regulate, direct and compel, nullify, void, prevent or prohibit, any acquisition, holding, withholding, use, transfer, withdrawal, transportation, importation or exportation of, or dealing in, or exercising any right, power, or privilege with respect to, or transactions involving, any property in which any foreign country or a national thereof has any interest by any person, or with respect to any property, subject to the jurisdiction of the United States.

(C) when the United States is engaged in armed hostilities or has been attacked by a foreign country or foreign nationals, confiscate any property, subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, of any foreign person, foreign organization, or foreign country that he determines has planned, authorized, aided, or engaged in such hostilities or attacks against the United States; and all right, title, and interest in any property so confiscated shall vest, when, as, and upon the terms directed by the President, in such agency or person as the President may designate from time to time, and upon such terms and conditions as the President may prescribe, such interest or property shall be held, used, administered, liquidated, sold, or otherwise dealt with in the interest of and for the benefit of the United States, and such designated agency or person may perform any and all acts incident to the accomplishment or furtherance of these purposes.61

These powers may be exercised "to deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States, to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States, if the President declares a national emergency with respect to such threat."6263 Presidents may invoke IEEPA under the procedures set forth in the NEA. When declaring a national emergency, the NEA requires that the President "immediately" transmit the proclamation declaring the emergency to Congress and publish it in the Federal Register.6364 The President must also specify the provisions of law that he or she intends to use.6465

In addition to the requirements of the NEA, IEEPA provides several further restrictions. Preliminarily, IEEPA requires that the President consult with Congress "in every possible instance" before exercising any of the authorities granted under IEEPA.6566 Once the President declares a national emergency invoking IEEPA, he or she must immediately transmit a report to Congress specifying:

(1) the circumstances which necessitate such exercise of authority;

(2) why the President believes those circumstances constitute an unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States, to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States;

(3) the authorities to be exercised and the actions to be taken in the exercise of those authorities to deal with those circumstances;

(4) why the President believes such actions are necessary to deal with those circumstances; and

(5) any foreign countries with respect to which such actions are to be taken and why such actions are to be taken with respect to those countries.66

The President subsequently is to report on the actions taken under the IEEPA at least once in every succeeding six-month interval that the authorities are exercised.6768 As per the NEA, the emergency may be terminated by the President, by a privileged joint resolution of Congress, or automatically if the President does not publish in the Federal Register and transmit to Congress a notice stating that such emergency is to continue in effect after such anniversary.68

Amendments to IEEPA

Congress has amended IEEPA eight times (Table 1). Five of the eight amendments have altered civil and criminal penalties for violations of orders issued under the statute. Other amendments excluded certain informational materials and expanded IEEPA's scope following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Congress also amended the NEA in response to a ruling by the Supreme Court to require a joint rather than a concurrent resolution to terminate a national emergency.

|

Date |

Action |

|

December 28, 1977 |

IEEPA Enacted (P.L. 95-223; 91 Stat. 1625) |

|

August 16, 1985* |

Following the Supreme Court's holding in INS v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919 (1983) finding so-called legislative vetoes unconstitutional, Congress amends the NEA to change "concurrent" resolution to "joint" resolution. (P.L. 99-93; 99 Stat. 407, 448 (1985)). * While not technically an amendment to IEEPA, IEEPA is tied to the NEA's provisions relating to the declaration and termination of national emergencies. |

|

August 23, 1988 |

IEEPA amended to exclude informational materials (Berman Amendment, see elaboration below). (Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988; P.L. 100-418; 102 Stat. 1107, 1371) |

|

October 6, 1992 |

Section 206 of IEEPA amended to increase civil and criminal penalties under the act. (Treasury, Postal Service, and General Government Appropriations Act, 1993; P.L. 102-393; 106 Stat. 1729) |

|

October 6, 1992 |

Section 206 of IEEPA amended to decrease civil and criminal penalties under the act. (Department of Defense Appropriations Act, 1993; P.L. 102-396; 106 Stat. 1876) |

|

April 30, 1994 |

IEEPA amended to update the definition of informational materials. (Foreign Relations Authorization Act for Fiscal Years 1994 and 1995; P.L. 103-236; 108 Stat. 382) |

|

September 23, 1996 |

IEEPA amended to penalize attempted violations of licenses, orders, regulations or prohibitions issued under the authority of IEEPA. (National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1997; P.L. 104-201; 110 Stat. 2725) |

|

October 26, 2001 |

USA PATRIOT Act Amendments, see elaboration below. (Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism (USA PATRIOT) Act of 2001; P.L. 107-56; 115 Stat. 272) |

|

March 9, 2006 |

Section 206 of IEEPA amended to increase civil and criminal penalties under the act. (USA PATRIOT Improvement and Reauthorization Act of 2005; P.L. 109-177; 120 Stat. 192) |

|

October 16, 2007 |

The International Emergency Economic Powers Enhancement Act amended Section 206 of IEEPA to increase civil and criminal penalties and added conspiracy to violate licenses, orders, regulations or prohibitions issued under the authority of IEEPA. Civil penalties are capped at $250,000 or twice the amount of the transaction found to have violated the law. Criminal penalties now include a fine of up to $1,000,000 and imprisonment of up to 20 years. (International Emergency Economic Powers Enhancement Act; P.L. 110-96; 121 Stat. 1011) |

Source: Congressional Research Service, based on United States Code, annotated.

The Berman Amendment and Informational Materials

Informational Materials Amendments to IEEPA

As originally enacted, IEEPA protected the rights of U.S. persons to participate in the exchange of "any postal, telegraphic, telephonic, or other personal communication, which does not involve a transfer of anything of value" with a foreign person otherwise subject to sanctions. Amendments in 1988 and 1994 updated this list of protected rights to include the exchange of published information in a variety of formats.69 The70 As amended, the act currently protects the exchange of "information or informational materials, including but not limited to, publications, films, posters, phonograph records, photographs, microfilms, microfiche, tapes, compact disks, CD ROMs, artworks, and news wire feeds," provided such exchange is not otherwise controlled for national security or foreign policy reasons related to weapons proliferation or international terrorism.71

USA PATRIOT Act Amendments to IEEPA

Unlike the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA), IEEPA did not allow the President to vest assets as originally acted.7072 In 2001, at the request of George W. Bush Administration, Congress amended IEEPA as part of the USA PATRIOT Act7173 to return to the President the authority to vest frozen assets, but only under certain circumstances:

... the President may ... when the United States is engaged in armed hostilities or has been attacked by a foreign country or foreign nationals, confiscate any property, subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, of any foreign person, foreign organization, or foreign country that [the President] determines has planned, authorized, aided, or engaged in such hostilities or attacks against the United States; and all right, title, and interest in any property so confiscated shall vest, when, as, and upon the terms directed by the President, in such agency or person as the President may designate from time to time, and upon such terms and conditions as the President may prescribe, such interest or property shall be held, used, administered, liquidated, sold, or otherwise dealt with in the interest of and for the benefit of the United States, and such designated agency or person may perform any and all acts incident to the accomplishment or furtherance of these purposes.72

Speaking about the efforts of intelligence and law enforcement agencies to identify and disrupt the flow of terrorist finances, Attorney General John Ashcroft told Congress:

At present the President's powers are limited to freezing assets and blocking transactions with terrorist organizations. We need the capacity for more than a freeze. We must be able to seize. Doing business with terrorist organization must be a losing proposition. Terrorist financiers must pay a price for their support of terrorism, which kills innocent Americans.

Consistent with the President's [issuance of E.O. 132247375] and his statements [of September 24, 2001], our proposal gives law enforcement the ability to seize the terrorists' assets. Further, criminal liability is imposed on those who knowingly engage in financial transactions, money-laundering involving the proceeds of terrorist acts.74

The House Judiciary Committee report explaining the amendments described its purpose as follows:

Section 203 of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (50 U.S.C. § 1702) grants to the President the power to exercise certain authorities relating to commerce with foreign nations upon his determination that there exists an unusual and extraordinary threat to the United States. Under this authority, the President may, among other things, freeze certain foreign assets within the jurisdiction of the United States. A separate law, the Trading With the Enemy Act, authorizes the President to take title to enemy assets when Congress has declared war.

Section 159 of this bill amends section 203 of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act to provide the President with authority similar to what he currently has under the Trading With the Enemy Act in circumstances where there has been an armed attack on the United States, or where Congress has enacted a law authorizing the President to use armed force against a foreign country, foreign organization, or foreign national. The proceeds of any foreign assets to which the President takes title under this authority must be placed in a segregated account can only be used in accordance with a statute authorizing the expenditure of such proceeds.

Section 159 also makes a number of clarifying and technical changes to section 203 of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, most of which will not change the way that provision currently is implemented.75

The government has apparently never employed the vesting power to seize Al Qaeda assets within the United States. Instead, the government has sought to confiscate them through forfeiture procedures.76

The first, and to date, apparently only, use of this power under IEEPA occurred on March 20, 2003. On that date, in Executive Order 13290, President George W. Bush ordered the blocked "property of the Government of Iraq and its agencies, instrumentalities, or controlled entities" to be vested "in the Department of the Treasury.... [to] be used to assist the Iraqi people and to assist in the reconstruction of Iraq."7779 However, the President's order excluded from confiscation Iraq's diplomatic and consular property, as well as assets that had, prior to March 20, 2003, been ordered attached in satisfaction of judgments against Iraq rendered pursuant to the terrorist suit provision of the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act and § 201 of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act7880 (which reportedly totaled about $300 million)7981.

A subsequent executive order blocked the property of former Iraqi officials and their families, vesting title of such blocked funds in the Department of the Treasury for transfer to the Development Fund for Iraq (DFI) to be "used to meet the humanitarian needs of the Iraqi people, for the economic reconstruction and repair of Iraq's infrastructure, for the continued disarmament of Iraq, for the cost of Iraqi civilian administration, and for other purposes benefitting of the Iraqi people."8082 The DFI was established by UN Security Council Resolution 1483, which required member states to freeze all assets of the former Iraqi government and of Saddam Hussein, senior officials of his regime and their family members, and transfer such assets to the DFI, which was then administered by the United States. Most of the vested assets were used by the Coalition Provision Authority (CPA) for reconstruction projects and ministry operations.81

The USA PATRIOT Act made three other amendments to Section 203 of IEEPA.8284 After the power to investigate, it added the power to block assets during the pendency of an investigation.8385 It clarified that the type of interest in property subject to IEEPA is an "interest by any person, or with respect to any property, subject to the jurisdiction of the United States."8486 It also added subsection (c), which provides:

In any judicial review of a determination made under this section, if the determination was based on classified information (as defined in section 1(a) of the Classified Information Procedures Act) such information may be submitted to the reviewing court ex parte and in camera. This subsection does not confer or imply any right to judicial review.85

As described in the House Judiciary Committee report, these provisions were meant to clarify and codify existing practices.86

|

|

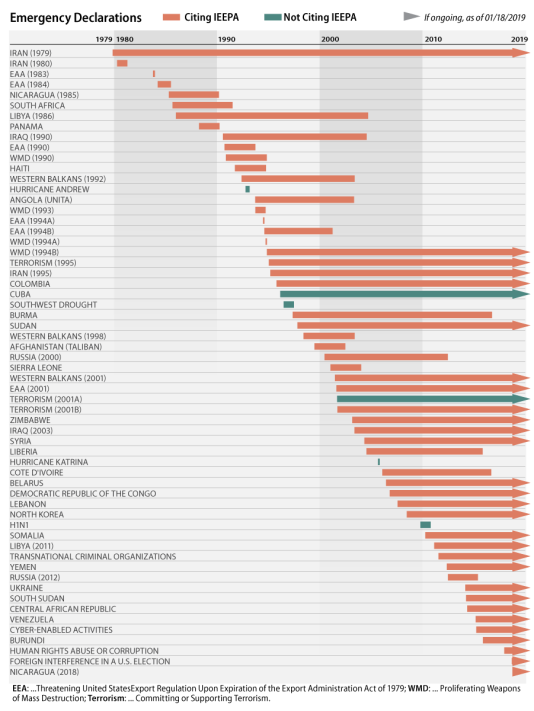

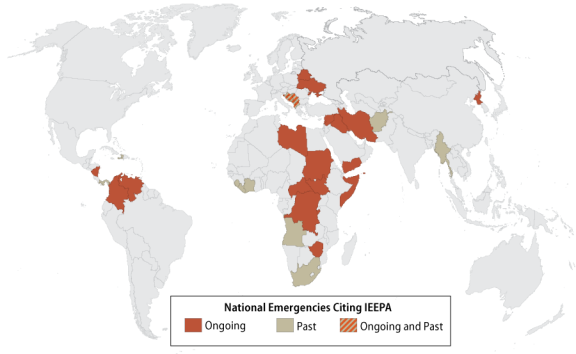

Source: CRS. Notes: Emergencies not citing IEEPA invoke one of the other |

IEEPA Trends

Like TWEA prior to its amendment in 1977, the President and Congress together have often turned to IEEPA to impose economic sanctions in furtherance of U.S. foreign policy and national security objectives. While initially enacted to rein in presidential emergency authority,8789 presidential emergency use of IEEPA has expanded in scale, scope, and frequency since the statute's enactment. The House report on IEEPA stated, "emergencies are by their nature rare and brief, and are not to be equated with normal, ongoing problems."8890 National emergencies invoking IEEPA, however, have increased in frequency and length since its enactment.

Since 1977, Presidents have invoked IEEPA in 5456 declarations of national emergency. On average, these emergencies last nearly a decade. Most emergencies have been geographically specific, targeting a specific country or government. However, since 1990, Presidents have declared non-geographically-specific emergencies in response to issues like weapons proliferation, global terrorism, and malicious cyber-enabled activities. The erosion of geographic limitations has been accompanied by an expansion in the nature of the targets of sanctions issued under IEEPA authority. Originally, IEEPA was used to target foreign governments; however, Presidents have increasingly targeted groups and individuals.8991 While Presidents usually make use of IEEPA as an emergency power, Congress has also directed the use of IEEPA or expressed its approval of presidential emergency use in several statutes.9092

Presidential Emergency Use91

93

IEEPA is the most frequently cited emergency authority when the President invokes NEA authorities to declare a national emergency. (Figure 1). Rather than referencing the same set of emergencies, as had been the case with TWEA, IEEPA has required the President to declare a national emergency for each independent use. As a result, the number of national emergencies declared under the terms of the NEA has proliferated over the past four decades. Presidents declared only four national emergencies under the auspices of TWEA in the four decades prior to IEEPA's enactment. In contrast, Presidents have invoked IEEPA in 5456 of the 6163 declarations of national emergency issued under the National Emergencies Act.92 As of MarchEmergencies Act.94 As of August 1, 2019, there were 3234 ongoing national emergencies; all but three involved IEEPA.9395

|

|

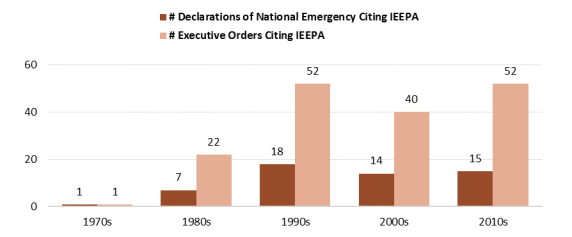

Source: CRS, 2010s current to Notes: Executive orders include declarations of national emergency that cite IEEPA that were made by executive order and any subsequent modifications or amendments to an emergency or such an order. |

Each year since 1990, Presidents have issued roughly 4.5 executive orders citing IEEPA and declared 1.5 new national emergencies citing IEEPA.9496 (Figure 2).

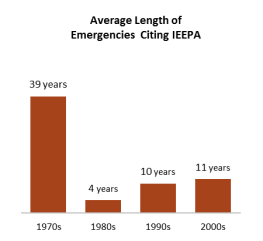

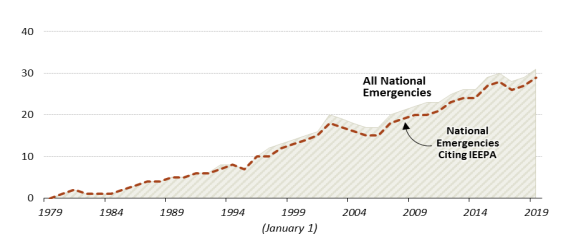

On average, emergencies invoking IEEPA last nearly a decade.9597 The longest emergency was also the first. President Jimmy Carter, in response to the Iranian hostage crisis of 1979, declared the first national emergency under the provisions of the National Emergencies Act and invoked IEEPA.9698 Six successive Presidents have renewed that emergency annually for nearly forty years. As of MarchAugust 1, 2019, that emergency is still in effect, largely to provide a legal basis for resolving matters of ownership of the Shah's disputed assets.9799 That initial emergency aside, the length of emergencies invoking IEEPA has increased each decade. The average length of an emergency invoking IEEPA declared in the 1980s was four years. That average extended to 10 years for emergencies declared in the 1990s and 1112 years for emergencies declared in the 2000s (Figure 3).98100 As such, the number of ongoing national emergencies has grown nearly continuously since the enactment of IEEPA and the NEA (Figure 4). Between January 1, 1979, and JanuaryAugust 1, 2019, there were on average 14 ongoing national emergencies each year, 13 of which invoked IEEPA.

|

|

Source: CRS. Current as of August 1, 2019.Notes: A single emergency was declared in the 1970s (Iran) and that has lasted |

In most cases, the declared emergencies citing IEEPA have been geographically specific (Figure 5). For example, in the first use of IEEPA, President Jimmy Carter issued an executive order that both declared a national emergency with respect to the "situation in Iran" and "blocked all property and interests in property of the Government of Iran [...]."99101 Five months later, President Carter issued a second order dramatically expanding the scope of the first EO and effectively blocked the transfer of all goods, money, or credit destined for Iran by anyone subject to the jurisdiction of the United States.100102 A further order expanded the coverage to block imports to the United States from Iran.101103 Together, these orders touched upon virtually all economic contacts between any place or legal person subject to the jurisdiction of the United States and the territory and government of Iran.102104

Many of the executive orders invoking IEEPA have followed this pattern of limiting the scope to a specific territory, government, or its nationals. Executive Order 12513, for example, prohibited "imports into the United States of goods and services of Nicaraguan origin" and "exports from the United States of goods to or destined for Nicaragua." The order likewise prohibited Nicaraguan air carriers and vessels of Nicaraguan registry from entering U.S. ports.103105 Executive Order 12532 prohibited various transactions with the "Government of South Africa or to entities owned or controlled by that Government."104

|

Figure 4. Cumulative Number of Ongoing National Emergencies by Year |

|

|

Source: CRS. Current as of August 1, 2019. |

While the majority (3839) of national emergencies invoking IEEPA have been geographically specific, ten11 have lacked explicit geographic limitations.105107 President George H.W. Bush declared the first geographically nonspecific emergency in response to the threat posed by the proliferation of chemical and biological weapons.106108 Similarly, President George W. Bush declared a national emergency in response to the threat posed by "persons who commit, threaten to commit, or support terrorism."107109 President Barack Obama declared emergencies to respond to the threats of "transnational criminal organizations" and "persons engaging in malicious cyber-enabled activities." President Donald Trump declared an emergency to respond to "foreign adversaries" who were "creating and exploiting vulnerabilities in information and communications technologies and services."110 Without explicit geographic limitations, these orders have included provisions that are global in scope. These geographically nonspecific emergencies invoking IEEPA have increased in frequency over the past 40 years—threefive of the ten11 have been declared since 2015.108111

|

|

Source: CRS. Current as of August 1, 2019. |

|

Examples of Actions Taken in Non-Geographic Emergencies Citing IEEPA

|

In addition to the erosion of geographic limitations, the stated motivations for declaring national emergencies have expanded in scope as well. Initially, stated rationales for declarations of national emergency citing IEEPA were short and often referenced either a specific geography or the specific actions of a government. Presidents found that circumstances like "the situation in Iran,"109112 or the "policies and actions of the Government of Nicaragua,"110113 constituted "unusual and extraordinary threat[s] to the national security and foreign policy of the United States" and would therefore declare a national emergency.111114

The stated rationales have, however, expanded over time in both the length and subject matter. Presidents have increasingly declared national emergencies, in part, to respond to human and civil rights abuses,112115 slavery,113116 denial of religious freedom,114117 political repression,115118 public corruption,116119 and the undermining of democratic processes.117120 While the first reference to human rights violations as a rationale for a declaration of national emergency came in 1985,118121 most of such references have come in the past twenty years. Table A-2.

Presidents have also expanded the nature of the targets of IEEPA sanctions. Originally, the targets of sanctions issued under IEEPA were foreign governments. The first use of IEEPA targeted "Iranian Government Property."119122 Use of IEEPA quickly expanded to target geographically defined regions.120123 Nevertheless, Presidents have also increasingly targeted groups, such as political parties, corporations, or terrorist organizations, and individuals, such as supporters of terrorism or suspected narcotics traffickers.121124

The first instances of orders directed at groups or persons were limited to foreign groups or persons. For example, in Executive Order 12978, President Bill Clinton targeted specific "foreign persons" and "persons determined [...] to be owned or controlled by, or to act for or on behalf of" such foreign persons.122125 An excerpt is included below:

Except to the extent provided in section 203(b) of IEEPA (50 U.S.C. 1702(b)) and in regulations, orders, directives, or licenses that may be issued pursuant to this order, and notwithstanding any contract entered into or any license or permit granted prior to the effective date, I hereby order blocked all property and interests in property that are or hereafter come within the United States, or that are or hereafter come within the possession or control of United States persons, of:

(a) the foreign persons listed in the Annex to this order;

(b) foreign persons determined by the Secretary of the Treasury, in consultation with the Attorney General and the Secretary of State:

(i) to play a significant role in international narcotics trafficking centered in Colombia; or

(ii) materially to assist in, or provide financial or technological support for or goods or services in support of, the narcotics trafficking activities of persons designated in or pursuant to this order; and

(c) persons determined by the Secretary of the Treasury, in consultation with the Attorney General and the Secretary of State, to be owned or controlled by, or to act for or on behalf of, persons designated in or pursuant to this order.123

However, in 2001, President George W. Bush issued Executive Order 13219 to target "persons who threaten international stabilization efforts in the Western Balkans." While the order was similar to that of Executive Order 12978, it removed the qualifier "foreign." As such, persons in the United States, including U.S. citizens, could be targets of the order.124127 The following is an excerpt of the order:

Except to the extent provided in section 203(b)(1), (3), and (4) of IEEPA (50 U.S.C. 1702(b)(1), (3), and (4)), the Trade Sanctions Reform and Export Enhancement Act of 2000 (title IX, P.L. 106-387), and in regulations, orders, directives, or licenses that may hereafter be issued pursuant to this order, and notwithstanding any contract entered into or any license or permit granted prior to the effective date, all property and interests in property of:

(i) the persons listed in the Annex to this order; and

(ii) persons designated by the Secretary of the Treasury, in consultation with the Secretary of State, because they are found:

(A) to have committed, or to pose a significant risk of committing, acts of violence...125

Several subsequent invocations of IEEPA have similarly not been limited to foreign targets.126

In sum, presidential emergency use of IEEPA was directed at foreign states initially, with targets that were delimited by geography or nationality. Since the 1990s, however, Presidents have expanded the scope of their declarations to include individual persons and groups, regardless of nationality or geographic location, who are engaged in specific activities.

Congressional Nonemergency Use and Retroactive Approval

While IEEPA is often categorized as an emergency statute, Congress has used IEEPA outside of the context of national emergencies. When Congress legislates sanctions, it often authorizes or directs the President to use IEEPA authorities to impose those sanctions.

In the Nicaragua Human Rights and Anticorruption Act of 2018, the most recentfor example, Congress directed the President to exercise "all powers granted to the President [by IEEPA] to the extent necessary to block and prohibit [certain transactions]."127130 Penalties for violations by a person of a measure imposed by the President under the Act would be, likewise, determined by reference to IEEPA.128131

TheThis trend has been long-term. Congress first directed the President to make use of IEEPA authorities in 1986 as part of an effort to assist Haiti in the recovery of assets illegally diverted by its former government. That statute provided:

The President shall exercise the authorities granted by section 203 of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act [50 USC 1702] to assist the Government of Haiti in its efforts to recover, through legal proceedings, assets which the Government of Haiti alleges were stolen by former president-for-life Jean Claude Duvalier and other individuals associated with the Duvalier regime. This subsection shall be deemed to satisfy the requirements of section 202 of that Act. [50 USC 1701]129

In directing the President to use IEEPA, Congress waived the requirement that he declare a national emergency (and none was declared).133

Subsequent legislation has followed this general pattern, with slight variations in language and specificity.130134 The following is an example of current legislative language that has appeared in several recent statutes:

(a) IN GENERAL.—The President shall impose the sanctions described in subsection (b) with respect to—

...

(b) SANCTIONS DESCRIBED.—

(1) IN GENERAL.—The sanctions described in this subsection are the following:

(A) ASSET BLOCKING.—The exercise of all powers granted to the President by the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (50 U.S.C. 1701 et seq.) to the extent necessary to block and prohibit all transactions in all property and interests in property of a person determined by the President to be subject to subsection (a) if such property and interests in property are in the United States, come within the United States, or are or come within the possession or control of a United States person.

...

(2) PENALTIES.—A person that violates, attempts to violate, conspires to violate, or causes a violation of paragraph (1)(A) or any regulation, license, or order issued to carry out paragraph (1)(A) shall be subject to the penalties set forth in subsections (b) and (c) of section 206 of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (50 U.S.C. 1705) to the same extent as a person that commits an unlawful act described in subsection (a) of that section.131

Congress has also expressed, retroactively, its approval of unilateral presidential invocations of IEEPA in the context of a national emergency. In the Countering Iran's Destabilizing Activities Act of 2017, for example, Congress declared, "It is the sense of Congress that the Secretary of the Treasury and the Secretary of State should continue to implement Executive Order No. 13382."132

Presidents, however, have also used IEEPA to preempt or modify parallel congressional activity. On September 9, 1985, President Reagan, finding "that the policies and actions of the Government of South Africa constitute an unusual and extraordinary threat to the foreign policy and economy of the United States," declared a national emergency and limited transactions with South Africa.133137 The President declared the emergency despite the fact that legislation limiting transactions with South Africa was quickly making its way through Congress.134138 In remarks about the declaration, President Reagan stated that he had been opposed to the bill contemplated by Congress because unspecified provisions "would have harmed the very people [the U.S. was] trying to help."135139 Nevertheless, members of the press at the time136140 (and at least one scholar since)137141 noted that the limitations imposed by the Executive Orderexecutive order and the provisions in legislation then winding its way through Congress were "substantially similar."138

Current Uses of IEEPA

In general, IEEPA has served as an integral part of the postwar international sanctions regime.139143 The President, either through a declaration of emergency or via statutory direction, has used IEEPA to limit economic transactions in support of administrative and congressional national security and foreign policy goals. Much of the action taken pursuant to IEEPA has involved blocking transactions and freezing assets.

Once the President declares that a national emergency exists, he may use the authority in Section 203 of IEEPA (Grants of Authorities; 50 U.S.C. § 1702) to investigate, regulate, or prohibit foreign exchange transactions, transfers of credit, transfers of securities, payments, and may take specified actions relating to property in which a foreign country or person has interest—freezing assets, blocking property and interests in property, prohibiting U.S. persons from entering into transactions related to frozen assets and blocked property, and in some instances denying entry into the United States.

Pursuant to Section 203, Presidents have

- prohibited transactions with and blocked property of those designated as engaging in malicious cyber-enabled activities, including "interfering with or undermining election processes or institutions" [Executive Order 13694 of April 1, 2015, as amended; 50 U.S.C. § 1701 note. See also Executive Order 13848 of September 12, 2018; 83 F.R. 46843.];

- prohibited transactions with and blocked property of those designated as illicit narcotics traffickers including foreign drug kingpins;

- prohibited transactions with and blocked property of those designated as engaging in human rights abuses or significant corruption;

- prohibited transactions related to illicit trade in rough diamonds;

- prohibited transactions with and blocked property of those designated as Transnational Criminal Organizations;

- prohibited transactions with "those who disrupt the Middle East peace process;"

- prohibited transactions related to overflights with certain nations;

- instituted and maintained maritime restrictions;

- prohibited transactions related to weapons of mass destruction, in coordination with export controls authorized by the Arms Export Control Act and the Export Administration Act of 1979,

140144 and in furtherance of efforts to deter the weapons programs of specific countries (i.e., Iran, North Korea); - prohibited transactions with those designated as "persons who commit, threaten to commit, or support terrorism;"

- maintained the dual-use export control system at times when its then-underlying authority, the Export Administration Act authority had lapsed;

- blocked property of, and prohibited

andtransactions with, those designated as engaged in cyber activities that compromise critical infrastructures including election processes or the private sector's trade secrets; - blocked property of, and prohibited transactions with, those designated as responsible for serious human rights abuse or engaged in corruption;

- blocked certain property of, and prohibited

andtransactions with, foreign nationals of specific countries and those designated as engaged in activities that constitute an extraordinary threat.

;

141145 In addition, no President has used IEEPA to enact a policy that was primarily domestic in effect. Some scholars argue, however, that the interconnectedness of the global economy means it would probably be permissible to use IEEPA to take an action that was primarily domestic in effect.142

|

IEEPA vs Section 232 for Imposing Tariffs in Response to a While a President could likely use IEEPA to impose additional tariffs on imported goods as President Nixon did under TWEA, no President has done so. Instead, Presidents have turned to Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 in cases of purported emergency. However, IEEPA is not subject to the same procedural restraints as Section 232. As no investigation is required, IEEPA authorities can be invoked at any time in response to a national emergency based on an "unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States." As such, IEEPA may be a source of authority for the President to quickly impose a tariff. On May 30, 2019, President Trump announced his intention to use IEEPA to impose on and gradually increase a five percent tariff on all goods imported from Mexico until "the illegal migration crisis is alleviated through effective actions taken by Mexico."150 The tariffs were scheduled to be implemented on June 10, 2019, with five percent increases to take effect at the beginning of each subsequent month. On June 7, 2019, President Trump announced that that "The Tariffs scheduled to be implemented by the U.S. [on June 10], against Mexico, are hereby indefinitely suspended."151 |

Use of Assets Frozen under IEEPA

The ultimate disposition of assets frozen under IEEPA may serve as an important part of the leverage economic sanctions provide to influence the behavior of foreign actors. The President and Congress have each at times determined the fate of blocked assets to further foreign policy goals.

Presidential Use of Foreign Assets Frozen under IEEPA

Presidents have used frozen assets as a bargaining tool during foreign policy crises and to bring a resolution to such crises, at times by unfreezing the assets, returning them to the sanctioned entity or channeling them to a follow-on government. The following are some examples of how Presidents have made use of blocked assets to resolve foreign policy issues.

President Carter invoked authority under IEEPA to impose trade sanctions against Iran, freezing Iranian assets in the United States, in response to the hostage crisis in 1979.146152 On January 19, 1981, the United States and Iran entered into a series of executive agreements brokered by Algeria under which the hostages were freed,147153 a portion of the blocked assets ($5.1 billion) was used to repay outstanding U.S. bank loans to Iran, another part ($2.8 billion) was returned directly to Iran, another $1 billion was transferred into a security account in the Hague to pay other U.S. claims against Iran as arbitrated by the Iran-U.S. Claims Tribunal (IUSCT), and an additional $2 billion remained blocked pending further agreement with Iran or decision of the Tribunal. The United States also undertook to freeze the assets of the former Shah's estate along with those of the Shah's close relatives pending litigation in U.S. courts to ascertain Iran's right to their return. Iran's litigation was unsuccessful, and none of the contested assets were returned to Iran.148

Presidents have also been able to channel frozen assets to opposition governments in cases where the United States continued to recognize a previous government that had been removed by coup d'état or otherwise replaced as the legitimate government of a country. For example, after Panamanian President Eric Arturo Delvalle tried to dismiss de facto military ruler General Manuel Noriega from his post as head of the Panamanian Defense Forces, which resulted in Delvalle's own dismissal by the Panamanian Legislative Assembly, President Reagan recognized Delvalle as the legitimate head of government and instituted economic sanctions against the Noriega regime.149155 The Department of State advised U.S. banks not to disburse funds to the Noriega regime, and Delvalle was able to obtain court orders permitting him access to the funds.150156 President Reagan issued Executive Order 12635, which blocked all property and interests in payments of the government of Panama,151157 and the Department of the Treasury issued regulations requiring companies who owed money to Panama to pay those funds into an escrow account established at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, which also held payments owed by the United States for the operation of the Panama Canal Commission.152158 Some of the funds in the escrow account were used to pay the operating expenses of the Delvalle government.153159 After the U.S. invasion of Panama, President George H.W. Bush lifted economic sanctions154160 and used some of the frozen funds to repay debts owed by Panama to foreign creditors, with remaining funds returned to the successor government.155

In a similar more recent case, the Trump Administration's recognition of Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaidó as Venezuela's interim president156162 permitted Guaidó access to Venezuelan government assets held at the United States Federal Reserve and other insured United States financial institutions.157163 President Barrack Obama initially froze Venezuelan government assets in 2015, pursuant to IEEPA and the Venezuela Defense of Human Rights and Civil Society Act of 2014.158164 After official recognition of Guaidó, the Trump Administration imposed new sanctions under IEEPA to freeze the assets of the main Venezuelan state-owned oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela (Pdvsa),159165 which could both significantly reduce funds available to the regime of Nicolas Maduro and channel them to Guaidó.160

There is also precedent for using frozen foreign assets for purposes authorized by the U.N. Security Council. After the first war with Iraq, President George H.W. Bush ordered the transfer of frozen Iraqi assets derived from the sale of Iraqi petroleum held by U.S. banks to be transferred to a holding account in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to fulfill "the rights and obligations of the United States under U.N. Security Council Resolution No. 778."161167 The President cited a section of the United Nations Participation Act (UNPA),162168 as well as IEEPA, as authority to take the action.163169 The transferred funds were used to provide humanitarian relief and to finance the United Nations Compensation Commission,164170 which was established to adjudicate claims against Iraq arising from the invasion.165171 Other Iraqi assets remained frozen and accumulated interest until they were vested in 2003 (see below).

In some cases, the United States has ended sanctions and returned frozen assets to successor governments. In the case of the former Yugoslavia, for example, in 2003, $237.6 million in frozen funds belonging to the Central Bank of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia were transferred to the central banks of the successor states.166172 In the case of Afghanistan, $217 million in frozen funds belonging to the Taliban were released to the Afghan Interim Authority in January 2002.167

Congressionally Mandated Use of Frozen Foreign Assets and Proceeds of Sanctions

The executive branch has traditionally resisted congressional efforts to vest foreign assets to pay U.S. claimants without first obtaining a settlement agreement with the country in question.168174 Congress has overcome such resistance in the case of foreign governments that have been designated as "State Supporters of Terrorism."169175 U.S. nationals who are victims of state-supported terrorism involving designated states have been able to sue those countries for damages under an exception to the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA) since 1996.170176

To facilitate the payment of judgments under the exception, Congress passed Section 117 of the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act, 1999,171177 which further amended the FSIA by allowing attachment and execution against state property with respect to which financial transactions are prohibited or regulated under Section 5(b) TWEA, Section 620(a) of the Foreign Assistance Act (authorizing the trade embargo against Cuba), or Sections 202 and 203 of IEEPA, or any orders, licenses or other authority issued under these statutes. Because of the Clinton Administration's continuing objections, however, Section 117 also gave the President authority to "waive the requirements of this section in the interest of national security," an authority President Clinton promptly exercised in signing the statute into law.172178

The Section 117 waiver authority protecting blocked foreign government assets from attachment to satisfy terrorism judgments has continued in effect ever since, prompting Congress to take other actions to make frozen assets available to judgment holders. Congress enacted §2002 of the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000 (VTVPA)173179 to mandate the payment from frozen Cuban assets of compensatory damages awarded against Cuba under the FSIA terrorism exception on or prior to July 20, 2000.

The Department of the Treasury subsequently vested $96.7 million in funds generated from long-distance telephone services between the United States and Cuba in order to compensate claimants in Alejandre v. Republic of Cuba, the lawsuit based on the1996 downing of two unarmed U.S. civilian airplanes by the Cuban air force.174180 Another payment of more than $7 million was made using vested Cuban assets to a Florida woman who had won a lawsuit against Cuba based on her marriage to a Cuban spy.175181

As unpaid judgments against designated state sponsors of terrorism continued to mount, Congress enacted the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA).176182 Section 201 of TRIA overrode long-standing objections by the executive branch to make the frozen assets of terrorist states available to satisfy judgments for compensatory damages against such states (and organizations and persons) as follows:

Notwithstanding any other provision of law, and except as provided in subsection (b), in every case in which a person has obtained a judgment against a terrorist party on a claim based upon an act of terrorism, or for which a terrorist party is not immune under section 1605(a)(7) of title 28, United States Code, the blocked assets of that terrorist party (including the blocked assets of any agency or instrumentality of that terrorist party) shall be subject to execution or attachment in aid of execution in order to satisfy such judgment to the extent of any compensatory damages for which such terrorist party has been adjudged liable.177

Subsection (b) of Section 201 provided waiver authority "in the national security interest," but only with respect to frozen foreign government "property subject to the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations or the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations." When Congress amended the FSIA in 2008178184 to revamp the terrorism exception, it provided that judgments entered under the new exception could be satisfied out of the property of a foreign state notwithstanding the fact that the property in question is regulated by the United States government pursuant to TWEA or IEEPA.179

Congress has also directed that the proceeds from certain sanctions violations be paid into a fund for providing compensation to the former hostages of Iran and terrorist state judgment creditors.180186 To fund the program, Congress designated that certain real property and bank accounts owned by Iran and forfeited to the United States could go into the United States Victims of State Sponsored Terrorism Fund, along with the sum of $1,025,000,000, representing the amount paid to the United States pursuant to the June 27, 2014, plea agreement and settlement between the United States and BNP Paribas for sanctions violations.181187 The fund is replenished through criminal penalties and forfeitures for violations of IEEPA or TWEA-based regulations, or any related civil or criminal conspiracy, scheme, or other federal offense related to doing business or acting on behalf of a state sponsor of terrorism.182188 Half of all civil penalties and forfeitures relating to the same offenses are also deposited into the fund.183

Judicial Interpretation of IEEPA

A number of lawsuits seeking to overturn actions taken pursuant to IEEPA have made their way through the judicial system, including challenges to the breadth of congressionally delegated authority and assertions of violations of constitutional rights. As demonstrated below, most of these challenges have failed. The few challenges that succeeded did not seriously undermine the overarching statutory scheme for sanctions.

Dames & Moore v. Regan

The breadth of presidential power under IEEPA is illustrated by the Supreme Court's 1981 opinion in Dames & Moore v. Regan.184190 In Dames & Moore, petitioners had challenged President Carter's executive order establishing regulations to further compliance with the terms of the Algiers Accords, which the President had entered into to end the hostage crisis with Iran.185191 Under these agreements, the United States was obligated (1) to terminate all legal proceedings in U.S. courts involving claims of U.S. nationals against Iran, (2) to nullify all attachments and judgments, and (3) to resolve outstanding claims exclusively through binding arbitration in the Iran-U.S. Claims Tribunal (IUSCT). The President, through executive orders, revoked all licenses that permitted the exercise of "any right, power, or privilege" with regard to Iranian funds, nullified all non-Iranian interests in assets acquired after a previous blocking order, and required banks holding Iranian assets to transfer them to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to be held or transferred as directed by the Secretary of the Treasury.186

Dames and Moore had sued Iran for breach of contract to recover compensation for work performed.187193 The district court had entered summary judgment in favor of Dames and Moore and issued an order attaching certain Iranian assets for satisfaction of any judgment that might result,188194 but stayed the case pending appeal.189195 The executive orders and regulations implementing the Algiers Accords resulted in the nullification of this prejudgment attachment and the dismissal of the case against Iran, directing that it be filed at the IUSCT.

In response, Dames and Moore sued the government. The plaintiffs claimed that the President and the Secretary of the Treasury exceeded their statutory and constitutional powers to the extent they adversely affected Dames and Moore's judgment against Iran, the execution of that judgment, the prejudgment attachments, and the plaintiff's ability to continue to litigate against the Iranian banks.190

The government defended its actions, relying largely on IEEPA, which provided explicit support for most of the measures taken—nullification of the prejudgment attachment and transfer of the property to Iran—but could not be read to authorize actions affecting the suspension of claims in U.S. courts. Justice Rehnquist wrote for the majority:

Although we have declined to conclude that the IEEPA…directly authorizes the President's suspension of claims for the reasons noted, we cannot ignore the general tenor of Congress' legislation in this area in trying to determine whether the President is acting alone or at least with the acceptance of Congress. As we have noted, Congress cannot anticipate and legislate with regard to every possible action the President may find it necessary to take or every possible situation in which he might act. Such failure of Congress specifically to delegate authority does not, "especially . . . in the areas of foreign policy and national security," imply "congressional disapproval" of action taken by the Executive. On the contrary, the enactment of legislation closely related to the question of the President's authority in a particular case which evinces legislative intent to accord the President broad discretion may be considered to "invite" "measures on independent presidential responsibility." At least this is so where there is no contrary indication of legislative intent and when, as here, there is a history of congressional acquiescence in conduct of the sort engaged in by the President.191

The Court remarked that Congress's implicit approval of the long-standing presidential practice of settling international claims by executive agreement was critical to its holding that the challenged actions were not in conflict with acts of Congress.192198 For support, the Court cited to Justice Frankfurter's concurrence in Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co. v. Sawyer193199 stating that "a systematic, unbroken, executive practice, long pursued to the knowledge of the Congress and never before questioned … may be treated as a gloss on 'Executive Power' vested in the President by § 1 of Art. II."194200 Consequently, it may be argued that Congress's exclusion of certain express powers in IEEPA do not necessarily preclude the President from exercising them, at least where a court finds sufficient precedent exists.

Lower courts have examined IEEPA under a number of other constitutional doctrines.

Separation of Powers—Non-Delegation Doctrine