U.S. International Food Assistance: An Overview

Changes from December 6, 2018 to February 23, 2021

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

U.S. International Food Assistance:

An Overview

Contents

- Introduction

- International Food Assistance Programs

- Food for Peace Title II

- Farmer-to-Farmer (Food for Peace Title V)

- McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition

- Bill Emerson Humanitarian Trust

- Food for Progress

- Emergency Food Security Program

- Food Assistance Funding

- Common Features and Requirements

- Agricultural Cargo Preference

- U.S. Sourcing of Commodities

- Publicity and Labeling of Commodities

- Bellmon Analysis

- Bumpers Amendment

- Food for Peace Title II Requirements

- Issues for Congress

- In-Kind vs. Cash-Based Food Assistance

- Agricultural Cargo Preference

- Administrative Proposals and Legislation

- Administrative Proposals

- FY2018 Budget Request

- FY2019 Budget Request

- Legislation in the 115th Congress

- The House and Senate 2018 Farm Bills (H.R. 2)

- The Global Food Security Reauthorization Act of 2017

- The Food for Peace Modernization Act (S. 2551/H.R. 5276)

Tables

Summary

The United States has played a leading role in global efforts to alleviate hunger and improve food security. U.S. international food assistance programs provide support through two distinct methods: (1) in-kind aid, which ships U.S. commodities to regions in need, and (2) cash-based assistance, which provides recipients with vouchers, direct cash transfers, or locally procured foods.

U.S. International Food Assistance:

February 23, 2021

An Overview

Alyssa R. Casey

The United States is one of the foremost donors of food, or the means to purchase food,

Analyst in Agricultural

to people around the world at risk of hunger. The goal of U.S. international food

Policy

assistance programs is to provide emergency relief to populations impacted by crises,

such as conflicts or natural disasters, and nonemergency assistance to address chronic

Emily M. Morgenstern

food insecurity and help populations build resilience to potential threats to food supplies. Analyst in Foreign The current suite of international food assistance programs began with the Food for

Assistance and Foreign

Peace Act (P.L. 83-480), commonly referred to as "“P.L. 480," which established the Food for Peace program (FFP). Congress authorizes most food assistance programs in periodic farm bills. However, Congress authorized the Emergency Food Security Program (EFSP)—a newer, cash-based food assistance program—in” which established the

Policy

Food for Peace programs. Congress has since authorized additional programs through

agriculture legislation and reauthorized these programs through periodic farm bil s.

Congress also has established international food assistance programs in foreign affairs legislation and subsequent reauthorizations, such as the Global Food Security Act of 2016 (P.L. 114-195). Congress funds international food assistance programs through annual agriculture appropriations and state and foreign operations (SFOPS) appropriations bills. Since 2007, annual international food assistance outlays averaged $2.6 billion. In FY2016, FFP Title II and EFSP accounted for 87% of total international food assistance outlaysP.L. 114-195) and its 2018 reauthorization (P.L. 115-266).

Jurisdiction for international food assistance programs is split across the House and Senate Agriculture Committees and the House Foreign Affairs and Senate Foreign Relations Committees. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) administer U.S. international food assistance programs.

Historically, the United States providedCongress funds international food assistance exclusively through in-kind aid. Since the mid-1980s, FFP Title II, which provides in-kind donations, has been the dominant U.S. food aid program. (The name "FFP Title II" refers to Title II of the Food for Peace Act, in which Congress first authorized the program.) In the late 2000s, U.S. international food assistance began to shift toward a combination of in-kind and cash-based assistance. This is largely due to the Obama Administration creating the cash-based EFSP in 2010 to complement FFP Title II emergency aid. EFSP is used in conditions when in-kind aid cannot arrive soon enough or could potentially disrupt local markets or when it is unsafe to operate in conflict zones.

Despite the growth in cash-based assistance, U.S. international food assistance still relies predominantlyprograms through annual Agriculture appropriations and State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriations acts.

Annual outlays for U.S. international food assistance averaged $3.3 bil ion between FY2010 and FY2020. Outlays during this period varied, declining to a low of $2.29 bil ion in FY2013 and increasing to a high of $5.06 bil ion in FY2020.

U.S. international food assistance programs provide support through two distinct methods: (1) in-kind aid, which ships U.S. commodities to regions in need, and (2) market-based assistance, which provides recipients with

vouchers, direct cash transfers, or local y and regional y procured food. Historical y, the United States provided international food assistance exclusively through in-kind aid. In 2010, the Obama Administration established, and Congress later codified through legislation, the Emergency Food Security Program (EFSP), which provides largely market-based assistance. Since the establishment of EFSP, U.S. provision of market-based food assistance has increased. Market-based assistance now accounts for approximately 59% of total international food assistance, while in-kind aid comprises roughly 41%.

Despite the growth in market-based assistance, U.S. international food assistance stil relies on in-kind aid. Many other countries with international food assistance programs have converted primarily to cashto primarily market-based assistance. U.S. reliance on in-kind aid has becomeis controversial due to its potential to disrupt international and local markets and cost more than procuring food locallybecause it typical y costs more than market-based assistance. At the same time, lack of reliable suppliers and poor

infrastructure in recipient countries may limit the efficacy and efficiency of cash-based assistance. Also, in poorly controlled settings, cash transfers or food vouchers could be stolen or used by recipients to purchase nonfood items. Agricultural cargo preference (ACP)of market-based assistance. Cargo preference—the requirement that 50% of all al in-kind aid be shipped on U.S.-flag ships—has also becomealso is controversial due to findings that it can lead to higher transportation costs and longer delivery times. Higher costs may be partiallypartial y due to higher wages and better working conditions on U.S.-flag vessels compared to foreign-flag vessels. ACP may also contribute to maintaining a U.S.-flag merchant marine to provide sealift capacity during wartime or national emergencies.

The Trump AdministrationCargo preference also may contribute to military readiness, though some studies suggest there is little evidence to support this assertion.

Prior Administrations and certain Members of Congress have proposed changes to the structure and intent of

international food assistance programs. The 2018 farm bil (P.L. 115-334) and the Global Food Security Reauthorization Act of 2017 (P.L. 115-266) both wil expire at the end of FY2023. Congress may consider changes to international food assistance programs in the next farm bil or Global Food Security Act reauthorization, or in stand-alone legislation.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 4 link to page 4 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 10 link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 12 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 19 link to page 21 link to page 5 link to page 13 link to page 16 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 24 U.S. International Food Assistance:

An Overview

Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Jurisdiction .................................................................................................................... 1 International Food Assistance Programs ............................................................................. 3

Food for Peace Title II .......................................................................................... 4 Farmer-to-Farmer (Food for Peace Title V) .............................................................. 5 McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition ......................... 6

Local and Regional Food Aid Procurement Program .................................................. 6 Food for Progress ................................................................................................. 7 Bill Emerson Humanitarian Trust............................................................................ 7 Emergency Food Security Program ......................................................................... 8 Community Development Fund .............................................................................. 8

Food Assistance Funding.................................................................................................. 9 Recent Administration Proposals ..................................................................................... 10

Proposed Food Aid Reform Under the Obama Administration ........................................ 10 Proposed Funding Cuts and Account Consolidation Under the Trump Administration ........ 12

Issues for Congress ....................................................................................................... 13

In-Kind and Market-Based Food Assistance................................................................. 13

Cargo Preference ..................................................................................................... 16

Looking Ahead ............................................................................................................. 18

Figures Figure 1. U.S. International Food Assistance Jurisdiction ...................................................... 2 Figure 2. U.S. International Food Assistance Outlays, FY2010-FY2020 ................................ 10 Figure 3. U.S. In-Kind and Market-Based Food Assistance Outlays, FY2010 and FY2020 ....... 13

Tables

Table A-1. U.S. International Food Assistance ................................................................... 19

Appendixes Appendix. U.S. International Food Assistance Programs ..................................................... 19

Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 21

Congressional Research Service

link to page 6 U.S. International Food Assistance:

An Overview

Introduction The United States is one of the foremost donors of food, or the means to purchase food, to people around the world at risk of hunger. The goal of U.S. international food assistance programs is to

provide emergency relief to populations impacted by crises, such as conflicts or natural disasters, and nonemergency assistance to address chronic food insecurity and help populations build

resilience to potential threats to food supplies.

international food assistance programs. Some Members of Congress proposed changes in the House and Senate 2018 farm bills (H.R. 2). These proposed changes include amending requirements for some international food assistance programs and expanding flexibility to use cash-based assistance. Other proposed legislation would address ACP, expand flexibility to use cash-based assistance, and consolidate and alter funding for most international food assistance programs.

Introduction

The United States has played a leading role in global efforts to alleviate hunger and improve food security. Current food assistance programs originated in 1954 with the passage of what is now named the Food for Peace Act (FFPA, P.L. 83-480).11 This legislation, commonly referred to as "“P.L. 480," established the” established Food for Peace program (FFP). Originally, FFPprograms. Original y, Food for Peace had multiple aims: (1) to provide food to undernourished people abroad, (2) to reduce U.S. stocks of surplus grains that had accumulated under U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) commodity support programs, and

(3) to expand potential markets for U.S. food commodities. Since the end of the Cold War, U.S. food assistance goals have shifted away from the latter two aims and more toward emergency

response and supporting recipient countrylocal agriculture markets in recipient countries.

For most of its existence, U.S. international

What Is Global Food Security?

food assistance provided exclusively in-kind

In the 1990 farm bil , Congress defined international food

aid—commodities sourced in the United

security as “access by any person at any time to food

States and shipped to recipient countries. U.S.

and nutrition that is sufficient for a healthy and

law requires some international food

productive life.”

assistance programs to provide primarily in-

In 1992, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) issued a policy determination defining food

kind aid.2 However, in recent decades, U.S.

security as “when al people at al times have both

international food assistance has shifted from

physical and economic access to sufficient food to meet

exclusively in-kind to a combination of in-

their dietary needs for a productive and healthy life.”

kind and market-based assistance—such as

This definition took elements from the 1990 definition,

local y or regional y procured food, cash

as wel as from food security definitions put forward by the World Bank and the U.N. Food and Agriculture

transfers, or vouchers.

Organization.

This report provides an overview of U.S. international food assistance programs, including congressional jurisdiction, historical funding trends, and issues for congressional consideration. This report focuses on international food

assistance programs that currently receive funding from Congress.3

Jurisdiction Congressional jurisdiction over international food assistance programs is split between two authorizing committees and two appropriations subcommittees. Jurisdiction general y aligns with the major pieces of legislation that historical y provided statutory authority for agriculture markets.

|

Food Assistance Terminology As the understanding of hunger and its causes has evolved over time, so have the terms used to discuss hunger and food assistance. In this report, terms are defined as follows: Food aid refers to in-kind food transfers, whether used directly or monetized. Food assistance refers to both in-kind food transfers and cash-based programs that provide the means to acquire food. Food security encompasses food assistance but includes agricultural and rural economic development projects, nutritional well-being projects, and other activities that enhance food access and nutrition at the household, village, and country levels. |

For example, in 2018 the United States provided food assistance to food-insecure people in Ethiopia. This food assistance targeted those affected by flooding in spring 2018 as well as refugees who had fled to Ethiopia from neighboring countries, such as South Sudan.2

For most of its existence, U.S. international food assistance programs: the FFPA and the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (FAA, P.L. 87-195).

Administration of international food assistance programs also is split across two federal agencies: the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Agency for International Development

1 T his law was originally titled the Agricultural T rade Development and Assistance Act when passed in 1954. In 2008, Congress renamed it the Food for Peace Act.

2 For example, statute requires all aid provided through the Food for Peace T itle II program to be in-kind commodities, with limited exceptions (7 U.S.C. §1732(2)). For further detail, see “ International Food Assistance Programs.” 3 For information on historical and inactive food assistance programs, see CRS Report R41072, U.S. International Food Aid Program s: Background and Issues, by Randy Schnepf.

Congressional Research Service

1

link to page 5 link to page 22

U.S. International Food Assistance:

An Overview

(USAID). Figure 1 shows the congressional jurisdiction and implementing agency for each U.S.

international food assistance program discussed in this report.

Figure 1. U.S. International Food Assistance Jurisdiction

Source: CRS Notes: Feed the Future Development refers to agricultural development assistance provided under the Feed the Future initiative. The Feed the Future initiative is a government-wide initiative that includes al programs in this matrix, as wel as other assistance provided outside USDA and USAID. Thus, this matrix does not include al programs that comprise the Feed the Future initiative. The programs highlighted in this graphic are the programs discussed in this report. SFOPS = Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs; USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture; USAID = U.S. Agency for International Development.

The House and Senate Agriculture Committees have jurisdiction over programs authorized in the

FFPA and other agriculture legislation. The House and Senate Agriculture Appropriations subcommittees have jurisdiction over funding for these programs. The FFPA contains statutory authority for four international food assistance programs, two of which are currently active—Food for Peace (FFP) Title II and the Farmer-to-Farmer Program.4 Outside of the FFPA, Congress has authorized additional international food assistance programs in subsequent agriculture legislation, including the Bil Emerson Humanitarian Trust, the Food for Progress Program, and

the McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition Program.5 Congress has amended these programs in periodic farm bil s, most recently the 2018 farm bil (Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, P.L. 115-334). The programs under the Agriculture Committees’

jurisdiction are based primarily on in-kind aid.

4 Food for Peace (FFP) program names refer to the titles in the Food for Peace Act (FFPA, P.L. 83-480) that originally authorized the programs. FFP T itle II and FFP T itle V (commonly known as the Farmer -to-Farmer program) remain active today. T itles I and III of the FFPA authorize curren tly inactive programs. T itle IV includes general authorities and program requirements. 5 For more information on the authorizing statut e for each program, see Appendix.

Congressional Research Service

2

U.S. International Food Assistance:

An Overview

The House Foreign Affairs and Senate Foreign Relations Committees have jurisdiction over programs with statutory authority in the FAA. Congress enacted the FAA in 1961 and has amended it through periodic legislation. Theassistance provided exclusively in-kind aid—commodities sourced in the United States and shipped to recipient countries. In recent decades, U.S. food assistance programs have shifted from exclusively in-kind to a combination of in-kind and cash-based assistance, such as locally procured food, cash transfers, or vouchers. More recently, Feed the Future (FTF), a government-wide initiative that coordinates U.S. agriculture and food assistance, has increasingly aligned non-emergency food assistance with other food-security-related programs such as agricultural development and global health programs.

U.S. law requires federal international food assistance to be provided primarily through in-kind aid.3 Opinions among policymakers and interested parties differ over whether such requirements make food assistance programs less efficient or whether they have substantive benefits, such as lowering the risk of recipients using assistance for unintended purposes and preserving the coalition of nonprofit organizations, farmers, and shippers who support these programs.

This report provides an overview of U.S. international food assistance programs, including authorizing legislation, historical funding trends, and common program features and requirements. It also discusses issues for congressional consideration and recent legislative proposals. This report focuses on international food assistance programs that currently receive funding from Congress.4

International Food Assistance Programs5

Two main legislative tracks authorize international food assistance programs, each with different authorizing histories and congressional committees responsible for funding. First, the FFPA authorizes traditional food assistance programs based primarily on in-kind aid. These programs (explained later in this section) include FFP Title II, FFP Title V,6 the McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition Program, the Bill Emerson Humanitarian Trust, and Food for Progress. Congress has reauthorized the FFPA through periodic farm bills, most recently the 2014 farm bill (P.L. 113-79). These programs are under the jurisdiction of the House and Senate Agriculture Committees. Second, Congress permanently authorized the Emergency Food Security Program (EFSP) as part of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (FAA, P.L. 87-195) in the Global Food Security Act of 2016 (GFSA, P.L. 114-195). EFSP is under the jurisdiction of the House Foreign Affairs and Senate Foreign Relations Committees. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) implement international food assistance programs. USDA procures commodities for all food assistance programs, regardless of which agency implements the program. Table 1 lists each active food assistance program along with its primary delivery method, statutory authority, source of funding, and implementing agency.

|

Program |

Delivery Method |

Statutory Authority |

Funding Source |

Agency |

|

Food for Peace Title II |

In-kind |

FFPA |

Agriculture appropriations bills |

USAID |

|

Farmer-to-Farmer (Food for Peace Title V) |

|

FFPA |

Agriculture appropriations bills |

USAID |

|

McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition |

In-kind |

FFPA |

Agriculture appropriations bills |

USDA |

|

Bill Emerson Humanitarian Trust |

In-kind |

FFPA |

|

USDA |

|

Food for Progress |

In-kind |

FFPA |

|

USDA |

|

Emergency Food Security Program |

Cash-based |

FAA |

SFOPS appropriations bills |

USAID |

Source: Compiled by CRS. FFPA = Food for Peace Act of 1954, as amended; FAA = Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended; SFOPS = State and Foreign Operations.

Notes:

a. The Farmer-to-Farmer program does not provide in-kind or cash-based assistance but is included here because it is part of the suite of programs the FFPA authorizes, and its annual funding is tied to total funding for Food for Peace programs.

b. The authorizing legislation established mandatory funding, financed through the USDA Commodity Credit Corporation's borrowing authority.

Other key participants in delivering international food assistance are:

- Nongovernmental or intergovernmental organizations (NGOs or IOs): An NGO is a private organization that provides services or advocates on public policy issues, such as an organization that works to solve development problems at the local level. An IO is a multilateral institution such as the U.N. World Food Program. NGOs and IOs implement food assistance projects in countries of need, with oversight and program funding from USAID or USDA.

TheP.L. 114-195) amended Section 491 of the FAA to create the Emergency Food Security Program (EFSP). The program is authorized to provide emergency food assistance “including in the form of funds, transfers, vouchers, and agricultural commodities” to address emergency food needs as a result of natural, human-induced, and complex emergencies. The Global Food Security Reauthorization Act of 2017 (P.L. 115-266) reauthorized EFSP through FY2023. The Community Development Fund (CDF) also derives its authority from the FAA, though the act does not specifical y authorize CDF. Rather, CDF is designated as a portion of the Development Assistance (DA) account within the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriation. As such, it is subject to DA’s FAA authorities.6 International Food Assistance Programs USDA and USAID administer seven different international food assistance programs. The programs are implemented through partner organizations with oversight and program funding from USAID or USDA. These partner organizations typical y are nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) or international organizations, though foreign country governments and private-sector companies are eligible to participate in some programs.7 USDA’s Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) procures commodities for al food assistance programs, regardless of which agency implements the program.8 Typical y, funding for an international food assistance program supports multiple projects in a given fiscal year. For example, in FY2019, FFP Title II funding supported over 100 projects in more than 30 countries.9 International food assistance programs may differ from one another in a number of ways, including in their delivery method, sometimes referred to as a modality. Programs provide assistance through two distinct methods: 1. In-kind contributions are commodities produced in the United States and shipped to the target region. In addition to standard in-kind contributions, in-kind assistance also may be provided through the following methods: a. Prepositioning is a form of in-kind aid where shelf-stable (i.e., not easily spoiled) U.S. commodities are prepositioned in storage facilities in the United States and abroad to enable quicker response to emergencies. 6 T hese include Sections 103, 104, 106, 214, 251-255 and Chapter 10 of Part I of P.L. 87-195. 7 A nongovernmental organization (NGO) typically is a voluntary group or institution with a social mission, which operates independently from government. Partner NGOs may be based in the United States or in another country. An international organization may include an intergovernmental organization or a multilat eral institution such as the United Nations World Food Program. 8 T he Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC)Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC): The CCCis a government-owned financial institution, overseen byUSDA,the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which procures commodities, processes financial transactions, and finances domestic and international programs to support U.S. agriculture.7

The U.S. government provides food assistance through two distinct methods:

- 1. In-kind contributions are commodities produced in the United States and shipped to the target region. Some shelf-stable (i.e., not easily spoiled) U.S. commodities can be prepositioned in storage facilities in the United States and abroad to enable quicker response to emergencies.

Monetizationis a form of in-kind aid in which the entity sellsT he CCC procures U.S.-produced commodities for international food assistance programs on the open market. For more information on the CCC, see CRS Report R44606, The Com m odity Credit Corporation (CCC), by Megan Stubbs. 9 U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), USAID International Food Assistance Report to Congress for Fiscal Year 2019. Congressional Research Service 3 U.S. International Food Assistance: An Overview b. Monetization is a form of in-kind aid in which the partner organization sel s U.S. commodities on local markets in developing countries and uses the proceeds to fund development projects.82.Cash10 2. Market-based assistance provides direct cash transfersor, food vouchersto beneficiaries, or locally and regional y procured food to populations in need (also cal ed beneficiaries). Under local and regional procurement (LRP),NGOs or IOspartner organizations purchase food in the country or region where it is to be distributedto beneficiariesrather than in the United States.

The Obama Administration created Feed the Future (FTF) in 2010. FTF is a government-wide initiative that aims to improve U.S. international food security efforts by uniting all food-security related programs 11

International food assistance programs may provide emergency assistance, nonemergency assistance, or both. Emergency projects seek to distribute immediate, life-saving food and nutrition assistance to populations in crisis due to conflict or natural disaster. Nonemergency projects address the root causes of food insecurity and seek to build resilience among vulnerable

populations. Nonemergency projects often provide a combination of food distribution and nonfood assistance including education programs, technical assistance, and broader community

development initiatives.

International Food Assistance and the Feed the Future Initiative

Feed the Future is a government-wide initiative that aims to improve U.S. international food security efforts by strengthening coordination and uniting al food-security-related programs under common goals and evaluation criteria. Because FTF Feed the Future coordinates nonemergency food assistance programs with other food security efforts, such as global health and agricultural development programs. Because Feed the Future focuses on long-term food security, it does not coordinateinclude emergency food assistance activities. However, non-emergency food assistance activities—such as McGovern-Dole, Food for Progress, Farmer-to-Farmer, and non-emergency However, nonemergency food assistance—including the McGovern-Dole, Food for Progress, and Farmer-to-Farmer programs; nonemergency assistance provided under Food for Peace Title II; and Community Development Fund programming—are part of Feed the Future. USDA and USAID submit data on nonemergency food assistance programs to col aborative Feed the Future evaluations.12

provided under FFP Title II—are part of FTF. Under FTF, non-emergency food assistance programs coordinate activities with other food security efforts, such as global health and agricultural development programs. Non-emergency food assistance programs also submit data to collaborative FTF evaluations.9

Food for Peace Title II

Food for Peace Title II

Under FFP Title II, the federal government donates U.S.-sourced commodities to a qualifying IOinternational organization or NGO to be distributed directly to beneficiaries or monetized to fund developmentfood-insecure populations.13

10 Monetization is a process by which implementing partners sell in-kind commodities in local markets to fund nonemergency projects. Monetization used to be required for some FFP T itle II assistance by the farm bill; the most recent farm bill (P.L. 115-334) eliminated the monetization requirement, instead replacing it with a permissive authority. Analysts have found that in practice, monetization loses 20 -25 cents on the dollar (see, for example, Erin C. Lentz, Stephanie Mercier, and Christopher B. Barrett, “ International Food Aid and Food Assistance Programs and the Next Farm Bill,” American Enterprise Institute, October 2017, p. 8, at http://www.aei.org/publication/international-food-aid-and-food-assistance-programs-and-the-next-farm-bill/).

11 Historically, this modality has been referred to as local and regional procurement (LRP). More recently, USAID has recognized that in rare cases food must be procured outside the country or region of need for reasons of cost, timeliness, or appropriateness. T hus, USAID began referring to this modality as local, regional, and international procurem ent (LRIP). See Office of Food for Peace, Inform ation Bulletin 19-03, August 8, 2019, at https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00T VW5.pdf. T his report uses local and regional procurem ent to maintain consistency when discussing past studies and data on LRP.

12 For more information on Feed the Future, see CRS Report R44216, The Obama Administration’s Feed the Future Initiative, by Marian L. Lawson, Randy Schnepf, and Nicolas Cook . For more information on collaborative monitoring of international food assistance programs and Feed the Future, see USAID and USDA, “ U.S. International Food Assistance Report to Congress,” various years beginning in FY2012. 13 Partner organizations also may monetize commodities. However, since the 2018 farm bill eliminated the monetization requirement, use of monetization in FFP T itle II has decreased significantly. According to 7 U.S.C. §1723(c), monetization proceeds may “be used to implement income-generating, community development, health,

Congressional Research Service

4

U.S. International Food Assistance:

An Overview

USAID administers FFP Title II. The program funds both emergency and nonemergency projects. USAID determines how much program funding to al ocate to emergency and nonemergency projects each year, within statutory requirements. The majority of FFP Title II funds support emergency assistance. In FY2019, 84% of FFP Title II funds supported emergency assistance and

the remaining 16% supported nonemergency assistance.14

FFP Title II has statutory authority in the FFPA, and Congress provides funding for the program in annual Agriculture appropriations bil s. The FFPA contains a number of requirements that

dictate how USAID must implement FFP Title II. These requirements include the following:

Al commodities must be U.S.-sourced commodities, with limited exceptions.15 At least 75% of nonemergency commodities must be in the form of processed,

fortified, or bagged commodities (value-added commodities), and at least 50% of bagged, whole-grain commodities must be bagged in the United States.16

FFP Title II must distribute a minimum of 2.5 mil ion metric tons of commodities

per year, of which 1.875 mil ion metric tons must be distributed as nonemergency assistance.17

USAID must al ocate a minimum of $365 mil ion and a maximum of 30% of

total FFP Title II funding to nonemergency assistance each year.18

Farmer-to-Farmer (Food for Peace Title V)

The John Ogonowski and Doug Bereuter Farmer-to-Farmer program finances short-term (typical y projects.10 Congress provides funding for Title II annually through agriculture appropriations bills. The majority of Title II funds are used for emergency assistance, such as responding to conflicts or natural disasters. In FY2017, 76% of Title II funds supported emergency assistance, and the remaining 24% supported non-emergency assistance.11

USAID administers FFP Title II. NGOs and IOs apply to USAID to implement a project under FFP Title II. Once USAID approves a Title II project, the implementing organization requests commodities. USDA procures U.S.-produced commodities on the open market. The implementing organization works with USAID to arrange shipment of commodities by ocean freight in accordance with agricultural cargo preference laws discussed in the "Common Features and Requirements" section.12

Farmer-to-Farmer (Food for Peace Title V)

Congress established the John Ogonowski and Doug Bereuter Farmer-to-Farmer program13 in the 1966 FFPA reauthorization (P.L. 89-808). Congress first funded the program in 1985, when it established minimum required funding in the 1985 farm bill (P.L. 99-198). This minimum funding was 0.1% of the annual funds appropriated for Food for Peace programs. The Farmer-to-Farmer program's funding is discretionary and tied to annual total funding for Food for Peace programs. Congress has periodically updated minimum required funding levels in the farm bill. The 2014 farm bill (P.L. 113-79) authorized minimum funding of the greater of $15 million or 0.6% of the funds appropriated for Food for Peace programs. From FY2014 to FY2017, Congress provided $15 million per year in funding for the program.

USAID administers the Farmer-to-Farmer program, which finances short-term (typically two- to four-week) volunteer placements in developing countries to provide technical assistance to farmers.19 Volunteers are U.S. citizens drawn from farming, agribusiness, universities, and nonprofit organizations. USAID, which administers the program, selects eligible

NGOs to coordinate volunteer placements. Potential volunteers apply directly to the coordinating NGOs and are selected based on the needs of the individual or organization in the developing country. The Farmer-to-Farmer program does not provide in-kind or cash-based food assistancefinance food distribution. It is included in this discussion because it is part of the suite of programs the FFPA authorizes and it receives funding through

through annual appropriations for Food for Peace programs.

McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition

Congress established the McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition Program in the 2002 farm bill (P.L. 107-171). USDA administers the McGovern-Dole program, and Congress funds the program through annual agriculture appropriations bills. The McGovern-Dole program aims to advance food security, nutrition, and education for children—especially girls—by providing school meals. The program also focuses on improving children'

nutrition, cooperative development, agricultural, and other developmental activities.” It also states that proceeds may be used for transportation, storage, distribution, or enhancing the use of FFP T itle II commodities, or they may be invested, with any earned interest used for the purposes of the food assistance project under which the monetization occurs.

14 USAID, International Food Assistance Report to Congress for Fiscal Year 2019, April 2020. 15 7 U.S.C. §1723(2). 16 7 U.S.C. §1724(b). T he USAID administrator may waive this requirement if he or she determines the program goals would not be best met by enforcing it. In FY2019, 18% of non emergency commodities were value-added and 23% of whole-grain, bagged commodities were bagged in the United States. 17 7 U.S.C. §1724(a). T he USAID administrator has discretion to waive the minimum tonnage requirement to meet emergency needs or if such quantities cannot be used effectively as nonemergency assistance. T he administrator has waived this requirement every year in recent decades. In FY2017, T itle II assistance totaled 1.5 million metric tons of commodities, 243,180 metric tons of which were nonemergency assistance.

18 7 U.S.C. §1736f(e). Statute also states that funds appropriated for the Farmer-to-Farmer Program and for Community Development Funds that are used for implementing income-generating, community development, health, nutrition, cooperative development, agricultural, and other developmental activities may be counted toward the minimum FFP T itle II nonemergency requirement. 19 Congress established the program as the Farmer-to-Farmer Program and later renamed it after John Ogonowski, one of the pilots killed in the September 11, 2001, attacks and Representative Doug Bereuter, who was an initial sponsor of and advocate for the program.

Congressional Research Service

5

U.S. International Food Assistance:

An Overview

Congress established the Farmer-to-Farmer program in the 1966 FFPA reauthorization (P.L. 89-808). Congress did not fund the program until the 1985 farm bil (P.L. 99-198) established minimum required funding of 0.1% of the annual funds appropriated for Food for Peace programs. Congress has periodical y updated minimum required funding levels in the farm bil . The 2018 farm bil (P.L. 115-334) reauthorized minimum funding of the greater of $15 mil ion or

0.6% of the funds appropriated annual y for Food for Peace programs.

McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition

The McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition Program aims to advance food security, nutrition, and education for children—especial y girls—by providing in-kind aid to be distributed in school meals in priority countries. The program, administered by USDA, also focuses on improving children’s health before they enter school by providing food to

s health before they enter school by providing food to pregnant and nursing mothers, infants, and children under school age. In addition to providing food, the program encourages governments in recipient countries to establish national school feeding programs and provides technical assistance to help them do so.

USDA chooses priority countries for McGovern-Dole projects each year based on criteria including per- capita income,

literacy, and malnutrition rates

Congress established McGovern-Dole in the 2002 farm bil (P.L. 107-171). The 2018 farm bil (P.L. 115-334) reauthorized the program, including discretionary funding of “such sums as necessary.” P.L. 115-334 also amended the program to authorize USDA to use up to 10% of

annual McGovern-Dole funding for LRP.20 (This is separate from funding set aside for USDA’s LRP Program in annual appropriations for McGovern-Dole; see next section.) The 2018 farm bil conference report directed USDA to incorporate LRP assistance, particularly in the final years of McGovern-Dole projects “to support the transition to full local ownership and implementation.”

Congress funds the McGovern-Dole program through annual Agriculture appropriations bil s.

Local and Regional Food Aid Procurement Program

The LRP Program finances the provision of local y and regional y procured foods to beneficiaries, usual y in nonemergency situations. USDA provides funding to partner organizations, which then procure eligible commodities in the country or region in which the commodities wil be distributed. Al procured commodities must meet certain nutritional, quality,

and labeling standards determined by USDA. USDA typical y has used the LRP Program to supplement in-kind assistance in McGovern-Dole projects.21 In FY2019, USDA financed three LRP Program projects in Burkina Faso, Cambodia, and Nicaragua. Al three projects provided

commodities to schools to supplement McGovern-Dole projects.22

Congress established the LRP Program as a pilot program in the 2008 farm bil (P.L. 110-246). The provision authorized pilot projects to provide local y and regional y procured food to beneficiaries, and directed USDA to have an independent third party conduct an evaluation of al pilot projects. The provision provided $60 mil ion in mandatory funding over four years to

finance the pilot projects and evaluation. The 2014 farm bil (P.L. 113-79) permanently authorized the program and authorized discretionary funding of $80 mil ion annual y for FY2014-FY2018.

20 P.L. 115-334, §3309. 21 Statute authorizes USDA to give preference for LRP Program awards to eligible entities “that have, or are working toward, projects under” the McGovern-Dole program (7 U.S.C. §1726c(e)(2)). 22 For further detail, see USDA, Local and Regional Food Aid Procurement Program FY2019 Report to Congress, June 2020, at https://www.fas.usda.gov/newsroom/local-and-regional-food-aid-procurement -program-fy-2019-report -congress.

Congressional Research Service

6

U.S. International Food Assistance:

An Overview

The 2018 farm bil (P.L. 115-334) reauthorized this level of funding through FY2023. Since FY2016, Congress has appropriated funding for the program as a set-aside within funding for the McGovern-Dole Program. In FY2021, Congress set aside $23 mil ion of McGovern-Dole funding

for the LRP Program.

literacy, and malnutrition rates. The program primarily uses in-kind aid, but in recent years it was authorized to use LRP.14 In FY2016 and FY2017, Congress authorized that up to $5 million of the funds appropriated to the McGovern-Dole program may be used for LRP activities within existing McGovern-Dole projects. In FY2018, Congress authorized that up to $10 million of the funds appropriated to the McGovern-Dole program may be used for LRP activities.

Bill Emerson Humanitarian Trust

Congress first authorized the Bill Emerson Humanitarian Trust (BEHT) in its current form in the Africa: Seeds of Hope Act of 1998 (P.L. 105-385).15 USDA administers the BEHT. It is a reserve of U.S. commodities or funds held by the CCC. These commodities or funds can supplement FFP Title II, especially when FFP Title II funds alone cannot meet emergency food needs in developing countries. Congress reimburses the CCC for the value of any commodities released from the BEHT through either FFPA appropriations or direct appropriations to the CCC. The CCC may either use these reimbursement funds to replenish the released commodities or hold the funds for BEHT against future need to purchase U.S. commodities for emergency assistance. In 2008 USDA sold the BEHT's remaining commodities—about 915,000 metric tons (mt) of wheat—and currently the BEHT holds only funds. BEHT funds were used in FY2014 to purchase 189,970 mt of U.S. agricultural commodities to supply FFP Title II projects in South Sudan.16

Food for Progress

Food for Progress

Under the Food for Progress program, USDA donates U.S. agricultural commodities to partner IOsinternational organizations, NGOs, foreign governments, or private entities, which then monetize the commodities by selling them locally can then distribute the commodities to beneficiaries or monetize the commodities by sel ing them local y to raise funds for development projects.23 Food for Progress projects focus on improving agricultural productivity and expanding agricultural trade. Statute directs USDA, when awarding projects, to consider a country’s commitments to promote economic freedom and expand efficient

domestic commodity markets.24 In FY2020, USDA funded five Food for Progress projects in

seven countries.25

agricultural productivity through agricultural, economic, or infrastructure development. Recipient country governments must make commitments to introduce or expand free enterprise elements in their agricultural economies. In FY2017, USDA funded seven Food for Progress projects in nine different countries.17

Congress first authorized the Food for Progress program in the 1985 farm bill (bil (P.L. 99-198). It may receive funding through either Food for Peace Title I appropriations or CCC financing. Congress has not appropriated funding for new Title I programs Title I program funds since FY2006. Food for Progress now relies entirely on CCC financing. Statute requires that the program provide a minimum of 400,000 mtmetric tons of commodities each fiscal year.1826 However, this minimum has not been met in recent years, with actual totals averaging 253,269 metric tons per year between FY2010 and FY2019.27 Statute

authorizes the program to pay no more than $40 mil ion annual y for freight costs,28 which limits the amount of shipped commodities, particularly in years with high shipping costs. The 2018 farm bil authorized a new pilot program to finance Food for Progress projects directly rather than through monetization.29 The act authorized appropriations of $10 mil ion per year for FY2019-FY2023 for pilot agreements. Congress has not provided funding for these pilot agreements to

date.

Bill Emerson Humanitarian Trust

The Bil Emerson Humanitarian Trust (BEHT) is a reserve authorized to hold funds or commodities for use in rapidly responding to emergency food needs in humanitarian contexts. USDA and USAID jointly administer the BEHT, and the CCC holds al BEHT funds. These

commodities or funds can supplement FFP Title II when international food assistance programs cannot meet emergency food needs in a given fiscal year. The BEHT al ows USDA and USAID the option to provide additional food assistance quickly, without having to rely on supplemental appropriations from Congress. BEHT funds or commodities are subject to many of the same

requirements as FFP Title II, including the requirement to provide in-kind aid.

23 Statute authorizes USDA to provide commodities to partner entities for distribution or monetization. In practice, the majority of Food for Progress projects have monetized all commodities.

24 7 U.S.C. §1736o(c)-(d). 25 USDA, “Food for Progress Funding—FY2020,” at https://www.fas.usda.gov/programs/food-progress/food-progress-funding-fy-2020.

26 7 U.S.C. §1736o(g). 27 USDA and USAID, U.S. International Food Assistance Report, for years FY2010 through FY2019. 28 7 U.S.C. §1736o(f)(3). 29 P.L. 115-334, §3302.

Congressional Research Service

7

U.S. International Food Assistance:

An Overview

Congress authorized the BEHT in its current form in the Africa: Seeds of Hope Act of 1998 (P.L. 105-385).30 Congress authorized the BEHT to hold funds or certain commodities (wheat, rice, corn, and sorghum), but, since 2008, the BEHT has held only funds.31 Congress may appropriate funds to reimburse the CCC for any commodities or funds released from the BEHT. The CCC may either hold these funds in the BEHT or use the funds to replenish commodities to the BEHT. BEHT funds were last used in FY2014 to purchase 189,970 metric tons of U.S. agricultural

commodities to supply FFP Title II projects in South Sudan.32 Currently, the BEHT holds

approximately $280 mil ion in funds.33

Emergency Food Security Program

EFSP is considered a market-based assistance program, providing assistance in the form of food vouchers, cash transfers, or the local or regional procurement of commodities (LRP).34 USAID

has asserted that it uses EFSP assistancewith actual totals averaging 255,418 mt per year between FY2007 and FY2016 and ranging from as little as 160,120 mt in FY2013 to as much as 341,820 mt in FY2015.19 Statute limits the program to pay no more than $40 million annually for freight costs,20 which limits the amount of shipped commodities, particularly in years with high shipping costs.

Emergency Food Security Program

Unlike FFP Title II, EFSP is a cash-based program. It can complement Title II when significant barriers exist to providing in-kind aid—for example, when in-kind food would not arrive soon enough or could potentially disrupt local markets or when it is unsafe to operate in conflict zones. Once the agency has determined an EFSP intervention is needed, it uses four criteria to decide which market-based intervention is best suited to the recipient country context: market appropriateness, feasibility, project objectives, and

cost.35 In FY2019, the most recent year for which comprehensive data are available, USAID administered EFSP assistance in 50 countries. LRP was used most often, accounting for 45% of

EFSP assistance, with food vouchers and cash transfers following at 27% and 23%, respectively.36

USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistancewhen it is unsafe to operate in zones of civil conflict. For example, from FY2013 to FY2015, more than half of EFSP outlays were used to respond to the conflict in Syria.21 This includes assistance provided to internally displaced persons and refugees who fled to neighboring countries such as Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey.

USAID administers EFSP. USAID first employed EFSP in FY2010 based on authority in the FAA to provide disaster assistance. In 2016, Congress permanently authorized EFSP in the GFSA. Congress funds EFSP through the International

Disaster Assistance (IDA) account within the SFOPS appropriations bil .

Community Development Fund

CDF is used to fund—either solely or in conjunction with FFP Title II nonemergency funds—USAID’s Resilience Food Security Activities (RFSAs) in countries targeted by the Feed the Future food security initiative.37 RFSAs typical y are five-year programs aimed at addressing the 30 T he Bill Emerson Humanitarian T rust (BEHT ) replaced the Food Security Commodity Reserve established in 1996 and its predecessor, the Food Security Wheat Reserve, originally authorized in 1980.

31 In 2008, USDA sold the BEHT ’s remaining commodities—about 915,000 metric tons of wheat—and currently the BEHT holds only funds.

32 USAID, U.S. International Food Assistance Report: Fiscal Year 2014 , May 2016. 33 Author communication with USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, January 11, 2021. 34 For definitions of each market -based modality, see Appendix A in USAID, Emergency Food Security Program Fiscal Year 2019 Report to Congress, April 13, 2020, at https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1867/USAID_FY2019_EmergencyFoodSecurityProgramReport.pdf . 35 USAID, Emergency Food Security Program Fiscal Year 2019 Report to Congress, April 13, 2020. 36 USAID, Emergency Food Security Program Fiscal Year 2019 Report to Congress, April 13, 2020. USAID reports that the remaining 5% was used for “ complementary investments and other related activities.”

37 Resilience Food Security Activities formerly were referred to as Development Food Security Activities. Food for Peace Act T itle II nonemergency funds are authorized by the Food for Peace Act and provided for in the Agriculture appropriation. As such, they are subject to specific requirements that are different from the Community Development Fund. For more on nonemergency programs, see CRS Report R45879, International Food Assistance: Food for Peace Nonem ergency Program s, by Emily M. Morgenstern. T he Feed the Future initiative was launched by the Obama Administration and continues today. Current Feed the Future initiat ive target countries include Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guatemala, Honduras, Kenya, Mali, Nepal,

Congressional Research Service

8

link to page 13 link to page 16 U.S. International Food Assistance:

An Overview

root causes of food insecurity. Although the composition of each project depends on the local context, RFSAs may include in-kind food distributions, seed and livestock distribution, water supply and sanitation activities, trainings for smal holder farmers, and the organization of microenterprise groups. USAID considers the RFSAs as a means to support the transition from short-term emergency food assistance programs to longer-term food security assistance, such as agricultural development and nutrition assistance programs. As such, they share a close

relationship with USAID’s emergency food security activities and broader Feed the Future

initiative programming.

USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance administers CDF with input from USAID’s Bureau for Resilience and Food Security. USAID first employed CDF to reduce the agency’s reliance on monetization in its FFP Title II nonemergency projects and increase the funds available for a broader range of activities. Even as Congress has loosened the monetization requirement and made FFP Title II nonemergency funds more flexible, CDF remains in use today. Congress designates a level of funding each year for CDF within the DA account of the SFOPS

appropriation. The designation typical y is included in report language or in the joint explanatory

statement accompanying the final appropriation.

Food Assistance Funding U.S. international food assistance outlays have fluctuated over the past 11 years (Figure 2). Total outlays declined from FY2010 to FY2013. Outlays have increased since FY2013,Disaster Assistance (IDA) account within State and Foreign Operations appropriations bills.

Food Assistance Funding

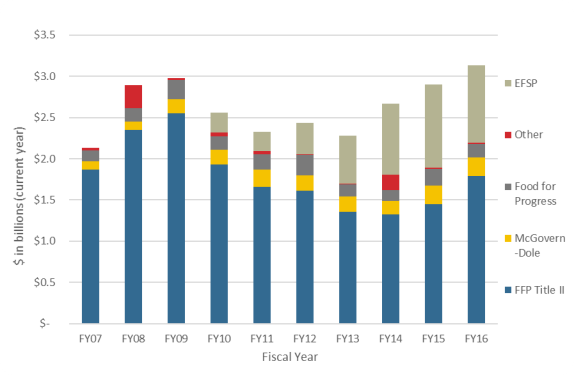

U.S. international food assistance outlays for these and other related programs have fluctuated over the past 10 years, rising in FY2008 and FY2009 partly in response to the global food price crisis of 2007-200822 and subsequently declining in the years following FY2009 (Figure 1). Outlays increased again between FY2013 and FY2016 partly in response to conflicts in Syria and Yemen and the Ebola epidemic in West Africa. While FFP Title II has comprised the bulk of food assistance outlays since the mid-1980s, cash-based partly in

response to the Ebola epidemic in West Africa between 2014 and 2016 and ongoing conflicts in South Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. For example, in FY2019, the U.S. al ocated over $1 bil ion of its emergency food assistance to needs arising from just the three conflicts in South Sudan, Syria, and Yemen.38 Extreme weather shocks also have increased international food assistance needs. For example, the United States provided emergency food assistance in response to multiple severe droughts in the Horn of Africa between 2014 and 2020 and Tropical Cyclones Kenneth

and Idai in southern Africa in 2019.

FFP Title II comprised the bulk of international food assistance outlays between the mid-1980s

and the mid-2010s. However, since FY2010 (the first year of EFSP), EFSP assistance has grown from approximately 10% of total international food assistance in FY2010 to 30% in FY2016outlays to 57% in FY2020. During that same period, the share of Title II food assistance outlays decreased from 75% to 57%.

|

|

Notes: "Other" includes Farmer-to-Farmer, BEHT, the LRP pilot program, and the inactive program Section 416(b). Data for FY2017 are not available. |

Common Features and Requirements

U.S. international food assistance programs share a number of common features and requirements, including agricultural cargo preference restrictions, commodity sourcing requirements, and labeling of commodity donations. Statutory requirements also mandate analyses to ensure that adequate storage facilities are available in recipient countries, assistance does not disrupt local markets in recipient countries, and assistance does not compete with U.S. agricultural exports. FFP Title II assistance also has specific requirements in addition to the requirements that apply to all international food assistance programs that it asserted would al ow the United States to reach an additional 2-4 mil ion more people each year.39 The proposal included shifting funds from FFP Title II to SFOPS appropriations accounts—mainly IDA and DA. For emergency food assistance, funds would be shifted from FFP Title II to IDA to al ow for the increased use of market-based approaches in

emergency contexts. Further, the Administration advocated for a new Emergency Food Assistance Contingency Fund. For nonemergency contexts, the Administration proposed a Community Development and Resilience Fund within DA. The Administration asserted that these changes

39 Department of State, FY2014 Congressional Budget Justification for Foreign Op erations Volume 2, May 17, 2013, p. 57.

Congressional Research Service

10

U.S. International Food Assistance:

An Overview

would “make food aid more timely and cost-effective” and “al ow the use of the right tool at the right time for responding to emergencies and chronic food insecurity.”40 The Administration claimed it did not seek to eliminate the use of U.S. in-kind food aid but rather to al ow USAID to choose the contexts in which U.S. in-kind food aid was most appropriate. In an effort to address concerns from the Maritime Administration and its stakeholders about shipping contracts decreasing with in-kind aid levels, the Administration included $25 mil ion for the Maritime

Administration “for additional targeted operating subsidies for militarily-useful vessels and incentives to facilitate the retention of mariners.”41 Final y, the Administration estimated these reforms would be cost-effective for the U.S. taxpayer, reducing the deficit by an estimated $500

mil ion over 10 years.

The Obama Administration’s reform proposal met with polarized reactions. Within the implementing partner community, proponents of the plan agreed with the Administration’s criticism of in-kind food, saying the approach was “outdated” and that with FFP Title II, “for every dol ar that is spent on feeding the hungry, only 47 cents reaches a person in need.”42 The

reform proposal was celebrated for its “right tool right time” approach and overal increased flexibility. However, other implementing partners expressed concern that removing U.S. food from U.S. international food assistance would undermine the program’s congressional support and ultimately result in a decrease in funding for al U.S. international food assistance in the long

run.43

In the U.S. agricultural community, the reactions to the reform proposal also were mixed. Some larger agribusinesses, including Cargil , and organizations such as the National Farmers Union voiced their support for the proposed changes.44 However, commodity groups such as USA Rice

joined with other organizations to write a letter to the President urging the continuation of U.S.

food aid programs in the current form.45

Perhaps the most vocal constituency against the Administration’s reform proposal was the shipping industry, with one union organization noting the proposal was “bad for the American farmer, bad for the American ports, bad for the taxpayer, and bad for our workers.”46 Others suggested the reform would harm the U.S.-flag fleet and ultimately would reduce U.S. military readiness.47 However, in a letter to House Foreign Affairs Committee leadership, the Department

40 Department of State, FY2014 Congressional Budget Justification for Foreign Operations Volume 2, May 17, 2013, p. 57.

41 Department of State, FY2014 Congressional Budget Justification for Foreign Operations Volume 2, May 17, 2013, p. 57.

42 CARE, CARE Supports President Obama’s Food Aid Reforms, April 10, 2013, at https://www.care.org/news-and-stories/press-releases/care-supports-president -obamas-food-aid-reforms/. 43 Ron Nixon, “Obama Administration Seeks to Overhaul International Food Aid,” New York Times, April 4, 2013, at nytimes.com/2013/04/05/us/politics/white-house-seeks-to-change-international-food-aid.html.

44 “Cargill Lends Support to Food Aid Reform,” AgriPulse, May 23, 2013, at https://www.agri-pulse.com/articles/2878-cargill-lends-support -to-food-aid-reform; Roger Johnson, “ Op-Ed: NFU Calls for More Flexibility on Food Aid,” AgriPulse, May 21, 2013, at https://www.agri-pulse.com/articles/2868-op-ed-nfu-calls-for-more-flexibility-on-food-aid. 45 Letter to the President from advocacy groups in support of current food aid programs, February 21, 2013. 46 Letter from Robert McEllrath, President of the International Longshore & Warehouse Union, June 12, 2013, at https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/814081-international-longshoreand-warehouse-union-letter.html.

47 Letter from Edward Wytkind, President of the T ransportation Trades Department, June 18, 2013, at https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/814076-afl-transportation-trades-department-letter.html.

Congressional Research Service

11

U.S. International Food Assistance:

An Overview

of Defense noted the reform proposal would not affect U.S. maritime readiness, national security,

or the “Department’s ability to crew the surge fleet and deploy forces and sustainment cargo.”48

Although some Members of Congress introduced legislation that would have enacted the

Administration’s proposal, ultimately the reform in its entirety was not enacted. The 2014 farm bil and GFSA reflected some of the proposed changes, but the broader U.S. international food

assistance structure remained intact during the Obama Administration.

Proposed Funding Cuts and Account Consolidation Under the Trump Administration Citing a desire to cut costs and find programmatic efficiencies, in its first two budget requests, the

Trump Administration proposed eliminating funding for the McGovern-Dole and FFP Title II programs and funding al international food assistance through IDA within the SFOPS appropriation. However, in both instances, the requests also included significant cuts to IDA from

the prior fiscal year: a 39% cut for FY2018 and a 17% cut for FY2019.

In its FY2020 and FY2021 budget requests, the Trump Administration again proposed eliminating the McGovern-Dole program, but instead of eliminating FFP Title II in favor of IDA, the Administration proposed a consolidated International Humanitarian Assistance (IHA) appropriations account that would combine funding from four humanitarian accounts: FFP Title

II, IDA, Migration and Refugee Assistance, and Emergency Refugee and Migration Assistance.49 According to budget documents, if enacted, IHA would have been managed by USAID under the policy authority of the Department of State. Notably, the proposed levels for IHA would have represented 37% and 38% decreases, respectively, from the prior year’s appropriations for the

component accounts.

The Trump Administration’s proposals to reduce and consolidate U.S. funding for international food assistance largely were unsupported by stakeholders, including food assistance implementing partners, commodity groups, and the shipping industry.50 The proposals were

similarly received in Congress, with existing programs continuing to receive bipartisan support in both chambers. As such, in the Administration’s later years, U.S. international food assistance program stakeholders saw the budget requests as a routine exercise that had little effect on congressional action. For example, in a statement following the release of the President’s FY2021 budget request, USA Rice’s vice president of government affairs stated, “While it is discouraging

to hear that the Administration is proposing to balance the budget on the backs of American farmers and those in need, we know that this budget wil not be wel received by Congress and is

essential y dead on arrival.”51

48 Letter from Frank Kendall, Under Secretary of Defense, to Chairman Edward Royce and Ranking Member Eliot Engel, House Foreign Affairs Committee, June 18, 2013, at https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/814075-pentagon-letter-on-food-aid-reform.html. 49 T he Migration and Refugee Assistance and Emergency Migration an d Refugee Assistance accounts both are in the State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs appropriation and are managed by the Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration.

50 See, for example, American Maritime Officers, “ Administration Seeks to Eliminate Food for Peace T itle II, Roll Back MSP Funding in FY2018 Budget,” Am erican Maritim e Officer, June 2017 at https://www.amo-union.org/news/2017/201706/201706.pdf; U.S. Global Leadership Coalition, “ Analysis of the Administration’s FY19 International Affairs Budget Request,” February 12, 2018, at https://www.usglc.org/the-budget/analysis-administrations-fy19-international-affairs-budget-request. 51 USA Rice, “ President’s FY2021 Budget Proposal,” February 10, 2020, at https://www.usarice.com/news-and-events/

Congressional Research Service

12

link to page 16

U.S. International Food Assistance:

An Overview

Issues for Congress

In-Kind and Marketfood assistance programs. These features and requirements are detailed below.

Agricultural Cargo Preference

In accordance with the Cargo Preference Act of 1954 (P.L. 83-644) and Section 901 of the Merchant Marine Act of 1936 (P.L. 74-835), both as amended, at least 50% of the gross tonnage of U.S. agricultural commodities provided under U.S. food aid programs must ship via U.S.-flag commercial vessels.23 This requirement is known as "agricultural cargo preference" (ACP). ACP is part of broader cargo preference requirements that apply to other government cargo, such as Department of Defense cargo. According to the Department of Transportation's Maritime Administration (MARAD), the main purpose of cargo preference laws is to sustain a privately owned, U.S.-flag merchant marine to provide sealift capability in wartime and national emergencies and to protect U.S. ocean commerce from foreign control.24 Under ACP, qualifying U.S.-flag ships must be privately owned and employ a crew consisting of at least 75% U.S. citizens. ACP applies to all in-kind aid provided under international food aid programs. It does not apply to LRP or other cash-based assistance.

U.S. Sourcing of Commodities

Statute requires all agricultural commodities distributed under food assistance programs authorized in the FFPA to be produced in the United States.25 However, there are some exceptions to this requirement. The requirement does not apply to food assistance provided under the LRP program authorized in the FFPA.26 It also does not apply to EFSP or other food assistance provided through authority in the FAA. Lastly, FFPA Section 202(e) allows a portion of FFP Title II funds to be used for storage, transportation, and administrative costs. The 2014 farm bill expanded eligible uses of these funds—referred to as 202(e) funds—to include "enhancing" FFP Title II projects, including through the use of cash-based assistance. Since 2014, 202(e) funds can be used to fund cash-based assistance that enhances existing FFP Title II in-kind assistance.27

Publicity and Labeling of Commodities

The FFPA requires foreign governments, NGOs, or IOs receiving U.S. commodities to widely publicize, to the extent possible, "that such commodities are being provided through the friendship of the American people as food for peace."28 In particular, governments and organizations must label FFP Title II commodities, "in the language of the locality in which such commodities are distributed, as being furnished by the people of the United States of America."29

Bellmon Analysis

Through the International Development and Food Assistance Act of 1977 (P.L. 95-88), Congress amended the FFPA to prohibit use of U.S. commodities for international food assistance if (1) the recipient country lacks adequate storage facilities to prevent spoilage or waste of commodities or (2) distribution of U.S. commodities in the recipient country would result in substantial disincentive to, or interference with, domestic production or marketing of agricultural commodities in that country. Cooperating organizations providing international food assistance must now conduct a "Bellmon analysis"—named for Senator Henry Bellmon, who sponsored the amendment to the FFPA. The analysis assesses whether the recipient country has adequate storage facilities and whether assistance would interfere with the recipient country's agricultural economy.30

Bumpers Amendment

An amendment to the Urgent Supplemental Appropriations Act, 1986 (P.L. 99-349, §209), offered by Senator Dale Bumpers, prohibited the use of U.S. foreign assistance funds for any activities that would encourage the export of agricultural commodities from developing countries that might compete with U.S. agricultural products on international markets.31 Exceptions to the Bumpers amendment include food-security-related activities, research activities that directly benefit U.S. producers, and activities in a country that the President determines is recovering from a widespread conflict, humanitarian crisis, or complex emergency.

Food for Peace Title II Requirements

In addition to the requirements listed above, FFP Title II assistance has specific requirements identified in Table 2.

|

Requirement |

U.S. Code Section |

Detail |

|

Minimum Tonnage (Total and Non-Emergency) |

7 U.S.C §1724(a) |

|

|

Minimum Allocation for Non-Emergency Aid |

7 U.S.C §1736f(e) |

Not less than 20% nor more than 30% of Title II funds shall be used for non-emergency assistance, with a minimum of at least $350 million programmed for non-emergency assistance each fiscal year. |

|

Value-Added Requirement |

7 U.S.C §1724(b) |

|

|

Monetization Requirement |

7 U.S.C §1723(b) |

Not less than 15% of all Title II non-emergency commodities must be monetized (sold on local markets to generate proceeds for development projects). Proceeds can be used to fund development projects or transportation, storage, and distribution of Title II commodities. |

Source: Compiled by CRS

Notes:

a. The USAID administrator has discretion to waive the minimum tonnage requirement in order to meet emergency needs or if such quantities cannot be used effectively as non-emergency assistance. The administrator has waived this requirement every year in recent decades. In FY2017, Title II assistance totaled 1.5 million mt of commodities, 279,400 mt of which were non-emergency assistance.

b. The USAID administrator may waive this requirement if he/she determines that the program goals will not be best met by enforcing it. In FY2017, 24.2% of non-emergency commodities were value-added, and 100% of whole-grain, bagged commodities were bagged in the United States.

Issues for Congress

In-Kind vs. Cash-Based Food Assistance

Historically-Based Food Assistance Historical y, the United States provided international food aid exclusively via in-kind commodities. The United States remains one of the few major donor countries that relies primarily oncontinues the provision of large quantities of in-kind aid. Many other donors—such as Canada, the European

Union, and the United Kingdom—have switched to primarily cashmarket-based assistance.3252 U.S. use of marketof cash-based assistance has increased significantly in recent years under EFSP and to support the use of LRP in the McGovern-Dole program.

Proponents of in-kind aid emphasize that, CDF, and the LRP Program—to the point where EFSP is now the largest among al U.S. international food assistance programs in terms of total annual outlays. In FY2010, in-kind aid comprised roughly 89% of U.S. international food assistance, with market-based assistance making up the remaining

11%. In FY2020, in-kind aid accounted for roughly 41% of assistance and market-based assistance comprised approximately 59% (Figure 3). During this same period, total international

food assistance outlays grew over 97%, from approximately $2.6 bil ion to $5.1 bil ion.

Figure 3. U.S. In-Kind and Market-Based Food Assistance Outlays, FY2010 and

FY2020

Source: CRS, using data from U.S. International Food Assistance Report to Congress, FY2010, and USDA and USAID preliminary food assistance outlays for FY2020.

publications/usa-rice-daily/article/usa-rice-daily/2020/02/10/president -s-fy-2021-budget-proposal. 52 U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), Local and Regional Procurement Can Enhance the Efficiency of U.S. Food Aid, But Challenges May Constrain Its Im plem entation, GAO-09-570, May 2009.

Congressional Research Service

13

U.S. International Food Assistance:

An Overview

Notes: In-kind and market-based breakdowns are CRS approximations, based on available data from USDA and USAID. FY2020 outlays are preliminary data. BEHT, which is used in years where USAID determines other international food assistance programs cannot meet emergency needs, was not used in FY202 0. Data does not include the Farmer-to-Farmer Program, because the program does not provide food assistance. FFP = Food for Peace; MGD = McGovern-Dole; FFPR = Food for Progress; BEHT = Bil Emerson Humanitarian Trust; EFSP = Emergency Food Security Program; LRP = Local and Regional Food Aid Procurement Program; CDF = Community Development Fund.

Proponents of in-kind aid contend it supports American jobs. Providing U.S.-grown commodities supports the agricultural sector, and shipping those commodities on U.S.-flag ships supports the transportation sector. In-kind aid also supports American companies that produce ready-to-use therapeutic and supplementary foods, foods that are speciallyspecial y formulated to address malnutrition. Proponents also maintain that the visibility of in-kind food with U.S labels fosters good will between goodwil between

the United States and recipient countries.33

In53

U.S. in-kind aid may be especially appropriate when local food availability is scarce. For example, in 2012 , during a severe drought in the Sahel region of Africa, USAID provided in-kind aid to recipients

during the "“lean season",” when markets were not well wel stocked. According to USAID, in-kind aid allowedal owed local farmers to plant and tend to crops instead of having to migrate in search of food.34 54 However, in these instances, LRP also may be appropriate and may support regional markets. Prepositioning food at warehouses in the United States and abroad allowsal ows aid to reach recipients sooner than traditional in-kind aid in emergency situations. In 2014, the U.S. Government

Accountability Office (GAO) found that prepositioning shortened delivery time frames for in-

kind aid by one to two months compared towith standard delivery methods.35

55

Critics of in-kind aid emphasize that it takes longer to reach recipients than cash-based assistancemarket-based assistance and can be more costly, as transporting food aid requires food-safety measures such as regular fumigation to prevent contamination from pests, mold, or other forms of rot. Although prepositioning in-kind aid shortens delivery times, GAO found that it can involve additional costs due to storage costs and additional shipping coststo increased storage and shipping expenses. Prepositioned commodities can alsoalso can cost more than traditional in-kind commodities, due to a limited supply of commodities available for domestic prepositioning.36

prepositioning.56

In 2011, GAO found that in-kind aid may not provide adequate nutrition to recipients during