Section 232 Investigations: Overview and Issues for Congress

Changes from August 31, 2018 to September 6, 2018

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Section 232 Investigations: Overview and Issues for Congress

Contents

- Introduction

- Overview of Section 232

- Key Provisions and Process

- Section 232 Investigations to Date

- Relationship to WTO

- Recent Section 232 Actions on Steel and Aluminum

- Commerce Findings and Recommendations

- Presidential Actions

- Country Exemptions

- Product Exclusions

- Tariffs Collected to Date

- U.S. Steel and Aluminum Industries and International Trade

- Domestic Steel and Aluminum Manufacturing and Employment

- Global Production Trends

- Policy and Economic Issues

- Retaliation

- WTO Implications

- International Efforts to Address Overcapacity

- Potential Economic Impact

- Economic Dynamics of the Tariff Increase

- Assessing the Overall Economic Impact

- Section 232 Auto Investigation

- Issues for Congress

- Appropriate Delegation of Constitutional Authority

- Interpreting National Security

- Establishing New International Rules

- Effects on Trade Liberalization Efforts

- Impact on the Multilateral Trading System

- Impact on Broader International Relationships

Figures

Tables

Summary

Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 (19 U.S.C. §1862) provides the President with the ability to impose restrictions on certain imports based on an affirmative determination by the Department of Commerce (Commerce) that the product under investigation "is being imported into the United States in such quantities or under such circumstances as to threaten to impair the national security." Section 232 actions are of interest to Congress because they are a delegation of Congress's constitutional authority "to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations." They also have important potential economic and policy implications for the United States.

Global overcapacity in steel and aluminum production, mainly driven by China, has been an ongoing concern of Congress. The George W. Bush, Obama, and Trump Administrations each engaged in multilateral discussions to address global steel capacity reduction through the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). While the United States has extensive antidumping and countervailing duties on Chinese steel imports to counter China's unfair trade practices, steel industry and other experts argue that the magnitude of Chinese production acts to depress prices globally.

Based on concerns about global overcapacity and certain trade practices, in April 2017 the Trump Administration initiated Section 232 investigations on U.S. steel and aluminum imports. Effective March 23, 2018, President Trump applied 25% and 10% tariffs, respectively, on certain steel and aluminum imports. The President temporarily exempted several countries from the tariffs pending negotiations on potential alternative measures. Permanent tariff exemptions in exchange for quantitative limitations on U.S. imports were eventually announced covering steel for Brazil and South Korea, and both steel and aluminum for Argentina. Australia was exempted from both tariffs with no quantitative restrictions. Commerce is also managing a process for potential product exclusions to limit potential negative domestic effects the tariff may have on U.S. businesses and consumers. To date, over 30,000 applications have been received.

U.S. trading partners are challenging the tariffs under World Trade Organization (WTO) rules and have threatened or enacted retaliation, risking potential escalation of retaliatory tariffs. Some analysts view the U.S. unilateral actions as potentially undermining WTO rules, which generally allow parties to act to protect "national security."

Congress enacted Section 232 during the Cold War when national security issues were at the forefront of national debate. The Trade Expansion Act sets clear steps and timelines for Section 232 investigations and actions, but allows the President to make a final determination over the appropriate action to take following an affirmative finding by Commerce that the relevant imports threaten to impair national security. Prior to the Trump Administration, there have been 26 Section 232 investigations resulting in nine affirmative findings by Commerce. In six of those cases the President imposed a trade action.

On May 23, 2018, the Trump Administration initiated an additional Section 232 investigation on U.S. automobile and automobile part imports, and on July 18, launched a Section 232 investigation into uranium ore and product imports. These investigations as well as the Administration's decision to apply the steel and aluminum tariffs on imports from Canada, Mexico, and the EU—all major suppliers of the affected imports—have prompted further questions by some Members of Congress and trade policy analysts on the appropriate use of the trade statute and the proper interpretation of threats to national security on which Section 232 investigations are based. These actions have also intensified debate over potential legislation to constrain the President's authority with respect to Section 232.

The steel and aluminum tariffs are affecting various stakeholders in the U.S. economy, prompting reactions from several Members of Congress, some in support and others voicing concerns. In general, the tariffs are expected to benefit the domestic steel and aluminum industries, leading to potentially higher steel and aluminum prices and expansion in production in those sectors, while potentially negatively affecting consumers and downstream domestic industries (e.g., manufacturing and construction) through higher costs. To date, Congress has conducted oversight of the Section 232 investigations and examined the potential economic and broader policy effects of the tariffs. Congress may consider legislation to override the tariffs that have already been imposed or to revoke or further limit the authority it previously delegated to the President going forward in future investigations.

Introduction

On March 8, 2018, President Trump issued two proclamations imposing duties on U.S. imports of certain steel and aluminum products, using presidential powers granted under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962.1 Section 232 authorizes the President to impose restrictions on certain imports based on an affirmative determination by the Department of Commerce (Commerce) that the targeted products are being imported into the United States "in such quantities or under such circumstances as to threaten to impair the national security." Section 232 investigations and actions are important for Congress, as the Constitution gives it primary authority over international trade matters. In the case of Section 232, Congress has delegated the President broad authority to impose limits on imports in the interest of U.S. national security. The statute does not require congressional approval of any presidential actions that fall within its scope. In the Crude Oil Windfall Profit Tax Act of 1980, however, Congress amended Section 232 by creating a joint disapproval resolution provision under which Congress could override presidential actions in the case of adjustments to petroleum or petroleum product imports.2

Section 232 is one of several tools the United States has at its disposal to address trade barriers and other foreign practices. These include investigations and actions to address import surges that are a "substantial cause of serious injury" or threat thereof to a U.S. industry (Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974), those that address violations or denial of U.S. benefits under trade agreements (Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974), and antidumping and countervailing duty laws (Title VII of the Tariff Act of 1930).

Trade is an important component of the U.S. economy, and Members often hear from constituents if factories and other businesses are hurt by competing imports, or if exporters face trade restrictions and other market access barriers overseas. Section 232 actions may affect industries, workers, and consumers in congressional districts and states (both positively and negatively). Following the steel and aluminum Section 232 actions, Commerce initiated Section 232 investigations into imports of automobiles and automobile parts in May 2018 and into uranium ore and product imports in July 2018. The current investigations have raised a number of economic and broader policy issues for Congress.

This report provides an overview of Section 232, analyzes the Trump Administration's Section 232 investigations and actions, and considers potential policy and economic implications and issues for Congress. To provide context for the current debate, the report also includes a discussion of previous Section 232 investigations and a brief legislative history of the statute.

Overview of Section 232

Congress created Section 232 during the Cold War when national security issues were at the forefront. It has been used periodically in response to industry petitions as well as through self-initiation by the executive branch. The Trade Expansion Act establishes a clear process and sets timelines for a Section 232 investigation, but the executive branch's interpretation of "national security" and the potential scope of any investigation can be quite expansive.

Key Provisions and Process

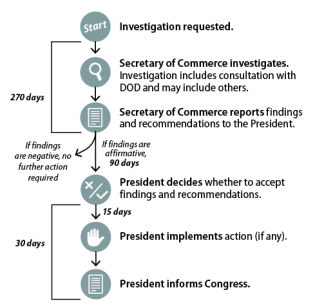

Upon request by the head of any U.S. department or agency, by application by an interested party, or by self-initiation, the Secretary of Commerce must commence a Section 232 investigation. The Secretary of Commerce conducts the investigation in consultation with the Secretary of Defense and other U.S. officials, as appropriate, to determine the effects of the specified imports on national security. Public hearings and consultations may also be held in the course of the investigation. Commerce has 270 days from the initiation date to prepare a report advising the President whether or not the targeted product is being imported "in such quantities or under such circumstances as to threaten to impair" U.S. national security, and to provide recommendations for action or inaction based on the findings. Any portion of the report that does not contain classified or proprietary information must be published in the Federal Register. See Figure 1 for the Section 232 process and timeline.

While there is no specific definition of national security in the statute, it states that the investigation must consider certain factors: domestic production needed for projected national defense requirements; domestic capacity; the availability of human resources and supplies essential to the national defense; and potential unemployment, loss of skills or investment, or decline in government revenues resulting from displacement of any domestic products by excessive imports.3

Once the President receives the report, he has 90 days to decide whether or not he concurs with the Commerce Department's findings and recommendations, and to determine the nature and duration of the action he views as necessary to adjust the imports so they no longer threaten to impair the national security (generally, imposition of some trade-restrictive measure). The President may implement the recommendations suggested in the Commerce report, take other actions, or not act. After making a decision, the President has 15 days to implement the action and 30 days to submit a written statement to Congress explaining the action or inaction; he must also publish his findings in the Federal Register.

|

|

Source: CRS graphic based on 19 U.S.C. §1862. |

Section 232 Investigations to Date

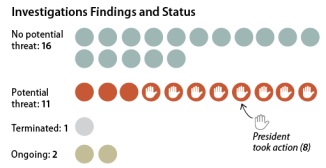

The Commerce Department (or the Department of the Treasury before it) conducted a total of 30 Section 232 investigations between 1962 and 2018, and two additional cases remain ongoing (see Table B-1). In 16 of these cases, Commerce determined that the targeted imports did not threaten to impair national security. In 11 cases, Commerce determined that the targeted imports threatened to impair national security and made recommendations to the President. The President took action eight times. In one case, the investigation was terminated at the petitioner's request before Commerce completed its investigation. Prior to the Trump Administration, 10 Section 232 investigations had been self-initiated by the Administration. (For a full list of cases to date, see Appendix B.)

In eight investigations dealing with crude oil and petroleum products, Commerce decided that the subject imports threatened to impair national security. The President took action in five of these cases. In the first three cases on petroleum imports (1973-1978), the President imposed licensing fees and additional supplemental fees on imports, which are no longer in effect, rather than adjusting tariffs or instituting quotas. In two cases, the President imposed oil embargoes, once in 1979 (Iran) and once in 1982 (Libya). Both were superseded by broader economic sanctions in the following years.4

In the three most recent crude oil and petroleum investigations (from 1987 to 1999), Commerce determined that the imports threatened to impair national security but did not recommend that the President use his authority to adjust imports. In the first of these reports (1987), Commerce recommended a series of steps to increase domestic energy production and ensure adequate oil supplies rather than imposing quotas, fees, or tariffs because any such actions would not be "cost beneficial and, in the long run, impair rather than enhance national security."5 In the latter two investigations (1994 and 1999), Commerce found that existing government programs and activities related to energy security would be more appropriate and cost effective than import adjustments. By not acting, the President in effect followed Commerce's recommendation.

Prior to the Trump Administration, a President arguably last acted under Section 232 in 1986. In that case, Commerce determined that imports of metal-cutting and metal-forming machine tools threatened to impair national security. In this case, the President sought voluntary export restraint agreements with leading foreign exporters, and developed domestic programs to revitalize the U.S. industry.6 These agreements predate the founding of the World Trade Organization (WTO), which established multilateral rules prohibiting voluntary export restraints (see "WTO Implications").

On May 23, 2018, after consultations with President Trump, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross announced the initiation of a Section 232 investigation to determine whether imports of automobiles, including SUVs, vans and light trucks, and automotive parts threaten to impair national security.7 Commerce held a public hearing and requested public comments to inform the ongoing auto investigation.8 In January 2018, two U.S. mining companies petitioned for the investigation into uranium imports.9 On July 18, Commerce announced the initiation of a Section 232 investigation and informed the Secretary of Defense.10

|

|

Source: CRS Graphic based on BIS data (https://www.bis.doc.gov/). Note: For a detailed list of cases, see Appendix B. |

Relationship to WTO

While unilateral trade restrictions may appear to be counter to U.S. trade liberalization commitments under the WTO agreements, Article XXI of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which predates and was one of the foundational agreements of the WTO, allows WTO members to take measures to protect "essential security interests." The WTO has not yet specifically defined the term "security interests," and WTO members, including the United States, have asserted broad authority to interpret this provision. Broad national security exceptions are also included in international trade obligations at the bilateral and regional levels, and could potentially limit the ability of countries to challenge such actions by trade partners. Historically, exceptions for national security have been rarely invoked and multiple trading partners have challenged recent U.S. actions under WTO rules (see "WTO Implications").

Recent Section 232 Actions on Steel and Aluminum

In April 2017, two presidential memoranda instructed Commerce to give priority to two self-initiated investigations into the national security threats posed by imports of steel and aluminum.11 In conducting its investigation, Commerce held public hearings and solicited public comments via the Federal Register and consulted with the Secretary of Defense, as required by the statute.12 In addition to the hearings, stakeholders submitted approximately 300 comments regarding the Section 232 investigation and potential actions. Some parties (mostly steel and aluminum producers) supported broad actions to limit steel and aluminum imports, while others (mostly users and consuming industries) opposed any additional tariffs or quotas on imports. Some stakeholders sought a middle ground, endorsing limited actions to target the underlying issues of overcapacity and unfair trade practices. Still others focused on the process, voicing caution in the use of Section 232 authority and warning against an overly broad definition of "national security" for protectionist purposes.13

The Commerce investigations analyzed the importance of certain steel and aluminum products to national security, using a relatively broad definition of "national security," defining it to include "the general security and welfare of certain industries, beyond those necessary to satisfy national defense requirements, which are critical for minimum operations of the economy and government."14 The broad scope of the investigations extended to current and future requirements for national defense and to 16 specific critical infrastructure sectors, such as electric transmission, transportation systems, food and agriculture, and critical manufacturing, including domestic production of machinery and electrical equipment. The reports also examined domestic production capacity and utilization, industry requirements, current quantities and circumstances of imports, international markets, and global overcapacity. Commerce based its definition of national security on a 2001 investigation on iron ore and semi-finished steel.15 Section 232 investigations prior to 2001 generally used a narrower definition considering U.S. national defense needs or overreliance on foreign suppliers.

Commerce Findings and Recommendations

The final reports, submitted to the President on January 11 and January 22, 2018, respectively, concluded that imports of certain steel mill products16 and of certain types of wrought and unwrought aluminum17 "threaten to impair the national security" of the United States. The Secretary of Commerce asserted that "the only effective means of removing the threat of impairment is to reduce imports to a level that should ... enable U.S. steel mills to operate at 80 percent or more of their rated production capacity" (the minimum rate the report found necessary for the long-term viability of the U.S steel industry and, separately, for the aluminum industry). The Secretary further recommended the President "take immediate action to adjust the level of these imports through quotas or tariffs" and identified three potential courses of action for both steel and aluminum imports, including tariffs or quotas on all or some steel imports from specific countries.

The Secretary of Defense, while concurring with Commerce's "conclusion that imports of foreign steel and aluminum based on unfair trading practices impair the national security," recommended targeted tariffs and "an inter-agency group further refine the targeted tariffs, so as to create incentives for trade partners to work with the U.S. on addressing the underlying issue of Chinese transshipment" in which Chinese producers ship goods to another country to reexport.18

Presidential Actions

On March 8, 2018, President Trump issued two proclamations imposing duties on U.S. imports of certain steel and aluminum products, based on the Secretary of Commerce's findings.19 The proclamations outline the President's decisions to impose tariffs of 25% on steel and 10% on aluminum imports effective March 23, 2018, but provided for flexibility in regard to country and product applicability of the tariffs (see below). The new tariffs are to be imposed in addition to any duties already in place.

In the proclamations, the President established a bifurcated approach, instructing Commerce to establish a process for parties to request individual product exclusions and a U.S. Trade Representative (USTR)-led process to discuss "alternative ways" through negotiations to address the threat with countries having a "security relationship" with the United States.

The President officially notified Congress of his actions in a letter dated April 6, 2018, though several Members have been actively engaged in voicing their views since the investigations were launched.20

Country Exemptions

Initially, the President temporarily excluded imports of steel and aluminum products from Mexico and Canada from the new tariffs, and the Administration has implicitly and explicitly linked a successful outcome of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) renegotiation to maintaining the exemptions. As part of those negotiations, the United States, Canada, and Mexico have reportedly agreed to add steel and aluminum to the tracing list used to calculate domestic content under NAFTA's Rules of Origin.21 With regard to other countries, the President expressed a willingness to be flexible, stating that countries with which the United States has a "security relationship" may discuss "alternative ways" to address the national security threat and gain an exemption from the tariffs. The President charged the USTR with negotiating bilaterally with trading partners on potential exemptions.

On March 22, after discussions with multiple countries, the President issued proclamations temporarily excluding Australia, Argentina, Brazil, South Korea, and the European Union (EU), as well as Canada and Mexico, from the Section 232 tariffs.22 The President gave a deadline of May 1, 2018, by which each trading partner had to negotiate "a satisfactory alternative means to remove the threatened impairment to the national security by imports" for steel and aluminum in order to maintain the exemption. On April 30, 2018, the White House extended negotiations and tariff exemptions with Canada, Mexico, and the EU for an additional 30 days, until June 1, 2018, and exempted Argentina, Australia, and Brazil from the tariffs indefinitely pending final agreements.23 South Korea, which pursued a resolution over the tariffs in the context of discussions to modify the U.S.-South Korea (KORUS) FTA, agreed to an absolute annual quota for 54 separate subcategories of steel and was permanently exempted from the steel tariffs.24 South Korea did not negotiate an agreement on aluminum and has been subject to the aluminum tariffs since May 1.

On May 31, the President proclaimed Argentina and Brazil, in addition to South Korea, permanently exempt from the steel tariffs, having reached final quota agreements with the United States on steel imports.25 Brazil, like South Korea, did not negotiate an agreement on aluminum and is now subject to the aluminum tariffs. The Administration also proclaimed aluminum imports from Argentina permanently exempt from the aluminum tariffs subject to an absolute quota.26 The Administration proclaimed U.S. imports of steel and aluminum from Australia permanently exempt from the tariffs as well, but did not set any quantitative restrictions on Australian imports.

As of June 1, U.S. imports of steel and aluminum from Canada, Mexico, and the European Union are subject to the Section 232 tariffs. These countries are among the largest suppliers of U.S. imports of the targeted goods, accounting for nearly 50% by value in 2017 (see Appendix C). The imposition of tariffs on these major trading partners increases the economic significance of the tariffs and has prompted criticism from several Members of Congress, including the chairs of the House Ways and Means and Senate Finance Committees.27

The Trump Administration states that discussions with Canada, Mexico, and the EU remain ongoing and that it remains open to discussions with other countries.28 NAFTA negotiations with Canada and Mexico remain ongoing. On July 27, 2018, after meeting with EU President Juncker, President Trump announced plans for "high-level trade negotiations" to eliminate all tariffs, including those on steel and aluminum, among other objectives. The two sides agreed to not impose further tariffs on each other's trade products while negotiations are active.29 It is unclear what those negotiations may seek in terms of alternative measures, but some type of quantitative restriction seems likely given the agreements the Administration has negotiated to date with most exempted countries.30 In addition to seeking quantitative restrictions, the Trump Administration may also pursue increasing traceability and reporting requirements, which may help limit transshipments of steel or aluminum originating from nonexempt countries.

|

Tariff Increase on U.S. Imports from Turkey On August 10, 2018, President Trump proclaimed a doubling of steel tariffs on Turkey to 50%. The President justified the action by stating "imports have not declined as much as anticipated and capacity utilization has not increased to [the] target level."31 In 2017 Turkey was the ninth-largest supplier of U.S. steel imports covered by the tariffs, accounting for $1.2 billion of U.S. imports (approximately 4% of relevant U.S. steel imports). The value of the Turkish lira relative to the U.S. dollar has declined by roughly 40% since the Section 232 tariffs went into effect.32 A depreciated lira makes U.S. imports from Turkey less costly to U.S. consumers, thereby counteracting the effect of the tariffs. The President noted the exchange rate volatility in his informal announcement of the tariff increase, but some observers contend that the action may be in response to ongoing foreign policy issues unrelated to trade.33 |

Product Exclusions

To limit potential negative domestic impacts of the tariffs on U.S. consumers and consuming industries, Commerce published an interim final rule for how parties located in the United States may request exclusions for items that are not "produced in the United States in a sufficient and reasonably available amount or of a satisfactory quality."34 Requests for exclusions and objections to requests have been and will continue to be posted on regulations.gov.35 The rule went into effect the same day as publication to allow for immediate submissions.

Exclusion determinations are to be based upon national security considerations. To minimize the impact of any exclusion, the interim rule allows only "individuals or organizations using steel articles ... in business activities ... in the United States to submit exclusion requests," eliminating the ability of larger umbrella groups or trade associations to submit petitions on behalf of member companies.36 Any approved product exclusion will be limited to the individual or organization that submitted the specific exclusion request. Parties may also submit objections to any exclusion within 30 days after the exclusion request is posted. The review of exclusion requests and objections will not exceed 90 days, creating a period of uncertainty for petitioners. Exclusions will generally last for one year. As of August 27, 2018, CommerceAt a September 6, 2018 hearing, Commerce testified that the agency had received over 3039,000 petitions, denying 1,458 and approving 2,101 and posted over 4,000 decisions.37

Companies have complained about the intensive, time-consuming process to submit exclusion requests; the lengthy waiting period to hear back from Commerce; what some view as an arbitrary nature of acceptances and denials; and that all exclusion requests to date have been rejected when a U.S. steel or aluminum producer has objected to it.38 Alcoa, the largest U.S. aluminum maker, has requested an exemption for all aluminum imported from Canada, where the firm has three smelting plants. While the company benefits from higher aluminum prices as a result of the tariffs, it is also seeing increased costs in its own supply chain.39

Some Members of Congress have raised concerns about the exclusion process. For example, in a letter to Commerce Secretary Ross, and at a recent hearing, Senate Finance Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch and Ranking Member Ron Wyden urged improvements to the product exclusion procedures on the basis that the detailed data required placed an undue burden on petitioners and objectors. They also suggested that the process appeared to bar small businesses from relying on trade associations to consolidate data and make submissions on behalf of multiple businesses. The letter further stated that Commerce had not instituted a clear process for protecting business proprietary information.40 A bipartisan group of House Members raised concerns about the speed of the review process and the significant burden it places on manufacturers, especially small businesses.41 The Members included specific recommendations such as allowing for broader product ranges to be included in a single request, allowing trade associations to petition, grandfathering in existing contracts to avoid disruptions, and regularly reviewing the tariffs' effects and sunsetting them if they have a "significant negative impact."42

Some Members have questioned the Administration's processes and ability to pick winners and losers through granting or denying exclusion requests. On August 9, 2018, Senator Ron Johnson requested that Commerce provide specific statistics and information on the exclusion requests and process and provide a briefing to the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. Senator Warren requested that the Commerce Inspector General investigate the implementation of the exclusion process, including a review of the processes and procedures Commerce has established; how they are being followed; and if exclusion decisions are made on a transparent, individual basis, free from political interference. She also requested evidence that the exclusions granted meet Commerce's stated goal of "protecting national security while also minimizing undue impact on downstream American industries," and that the exclusions granted to date strengthen the national security of the United States.43

On September 6, 2018, Commerce announced a new rule to allow companies to rebut objections to petitions.44Tariffs Collected to Date

As of July 16, 2018, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Authority collected $1.1 billion and $344.2 million from the Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum, respectively. The tariffs collected are put in the general fund of the U.S. Treasury and are not allocated to a specific fund. Based on 2017 U.S. import values, annual tariff revenue from the Section 232 tariffs could be as high as $5.8 billion and $1.7 billion for steel and aluminum, respectively, but such estimates do not account for dynamic effects.

Generally, higher import prices resulting from the tariffs should cause import demand and therefore tariff revenue to decline over time if U.S. production increases and sufficient domestic alternatives become available. Tariff revenue is also likely to decline as the Commerce Department grants additional product exclusions.

According to the President's proclamations implementing the Section 232 tariffs, one of the objectives of the tariffs is to "reduce imports to a level that the Secretary assessed would enable domestic steel (aluminum) producers to use approximately 80 percent of existing domestic production capacity and thereby achieve long-term economic viability through increased production."44

U.S. Steel and Aluminum Industries and International Trade

The United States competes for domestic and global market share with other major steel and aluminum producers. The most direct competition comes from China, the world's largest raw steel and primary aluminum producing country. China's capacity to make both metals influences the world market most directly by lowering steel and aluminum prices and thereby the profitability of domestic U.S. producers. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) began monitoring global steel production in the 1960s and tracks new capacity additions as well as plant and capacity closures. It notes that steel demand is weak globally but production continues to increase, driven by new investments around the world.4546 So far, no similar effort is underway to monitor or address aluminum overcapacity globally.

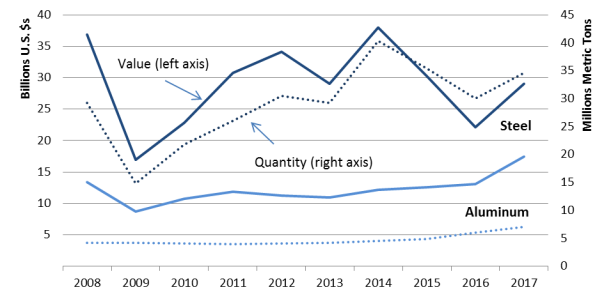

In 2017, U.S. imports of steel and aluminum products covered by the Section 232 tariffs totaled $29.0 billion and $17.4 billion, respectively (see Figure 3). Over the past decade, steel imports have fluctuated significantly, by value and quantity, while imports of aluminum have increased steadily. The expiration of temporary exclusions from the tariffs for Canada, Mexico, and the EU are economically significant for U.S. trade in both products. In 2017, these trading partners were the top three suppliers of U.S. steel imports facing the import tariff, together accounting for 47% of relevant U.S. steel imports.4647 Canada alone accounted for 41% of relevant U.S. aluminum imports in 2017, followed by China (11%) and Russia (9%). The countries with permanent exclusions from the tariff accounted for 20% of U.S. steel imports in 2017 and less than 5% of U.S. aluminum imports (see Appendix C).

|

Figure 3. U.S. Steel and Aluminum Imports Subject to Section 232 Tariffs |

|

|

Source: Created by CRS using data from Census Bureau on HTS products included in the Section 232 proclamations. |

Domestic Steel and Aluminum Manufacturing and Employment

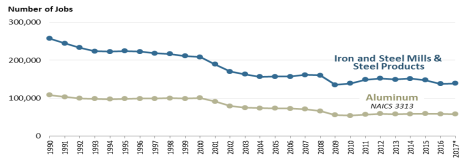

In 2017, U.S. steelmakers employed 139,900 workers (Figure 4), accounting for 1.1% of the nation's 12.4 million factory jobs. Employment in the steel industry has been declining for many years as new technology, particularly the increased use of electric furnaces to make steel, has reduced the demand for workers. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, labor productivity in steelmaking has nearly tripled since 1987 and has risen 15% over the past decade.4748 Hence, even a significant increase in domestic steel production is likely to result in a relatively small number of additional jobs.

Aluminum manufacturers employed 58,100 workers in 2017, a figure that has changed little since the 2007-2009 recession. Domestic smelting of aluminum from bauxite ore, which requires large amounts of electricity, has been in long-term decline, and secondary (recycled) aluminum now accounts for the majority of domestic aluminum production. Secondary unwrought aluminum is not covered by the Section 232 aluminum trade action.4849

|

|

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Employment Survey for North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) 3311 (iron and steel mills), 3312 (steel products), and NAICS 3313 (aluminum). Notes: * 2017 figures are estimated. |

Steelmaking and aluminum smelting are both extremely capital intensive. As a result, even small changes in output can have major effects on producers' profitability. Domestic steel producers have operated at 78% or less of production capacity in recent years.4950 Aluminum smelters in the United States operated at about 43% of production capacity in 2017.5051 A stated aim of the metals tariffs is to enable U.S. producers in both sectors to use an average of 80% of their production capacity, which the Section 232 reports deem necessary to sustain adequate profitability and continued capital investment.5152

Global Production Trends

The OECD Global Forum on Steel Excess Capacity estimates global steel overcapacity to be at more than 700 million metric tons, with more than half (425 million metric tons) accounted for by China.5253 Relatively little Chinese steel and aluminum enter the U.S. market directly, due to extensive U.S. dumping and subsidy determinations, but the large amount of Chinese production acts to depress prices globally. China has indicated that it plans to reduce its crude steelmaking capacity by 100-150 million metric tons over the five-year period from 2016 to 2020.53

Metals imports should be put in the context of U.S. production. In 2017, the United States produced more than twice the amount of steel it imported. According to Commerce's International Trade Administration, import penetration—the share of U.S. demand met by steel imports—reached 33% in 2016, compared to 23% in 2006.5455 Some segments of the domestic steel industry, such as slab converters, import a sizable share of their semi-finished feedstock from foreign suppliers, totaling nearly 8 million tons in 2017.5556 In the primary aluminum market, U.S. net import reliance rose to 61% in 2017 from 21% in 2013, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.5657 Most U.S. foreign trade in steel and aluminum is with Canada (see Appendix C).

Policy and Economic Issues

The Section 232 tariffs raise a number of issues for Congress. The economic repercussions of U.S. and foreign actions may be felt not only by domestic steel and aluminum producers, but by downstream manufacturers or other industries targeted for retaliation, or consumers. The response by other countries can have implications for the U.S. economy and multilateral world trading system. Also, other countries may be hesitant in the future to cooperate with the United States to address global issues, including steel and aluminum overcapacity, if their exports are subject to U.S. tariffs.

How U.S. trading partners respond to the Section 232 actions has varied based on the country's relationship with the United States. Some countries are pursuing direct negotiations, while keeping other countermeasures in reserve, and raising actions at the WTO (see below). Others have proposed or pursued retaliation with their own tariffs. Some companies have pursued litigation, and may also seek alternative markets for their products.

Retaliation

Several major U.S. trading partners have proposed or are currently imposing retaliatory tariffs in in response to the U.S. actions (see Table 1 below). The process of retaliation is complex given multiple layers of relevant international rules and the potential for unilateral action, which may or may not adhere to those existing rules. Both through agreements at the WTO and in bilateral and regional free trade agreements (FTAs), the United States and its trading partners have agreed to maintain certain tariff levels. Those same agreements include rules on potential responses, including formal dispute settlement procedures and in some cases commensurate tariffs, when one party increases its tariffs above agreed-upon limits.5758 Other exceptions, such as antidumping tariffs, countervailing duties, and safeguards, are addressed in WTO agreements.58

Most of the retaliatory actions of U.S. trading partners to date have been notified to the WTO pursuant to the Agreement on Safeguards. These retaliatory notifications listed below (see Table 1) are in addition to requests for consultations that are the first step in WTO dispute settlement proceedings (see "WTO Implications"). In addition, Japan submitted a notification to the WTO, but has yet to announce a list of specific products. Notifications by other countries may follow.

|

Trading Partner |

Estimated Value of Targeted U.S. Exports |

Effective Date |

Example Products Targeted |

|

China |

$3.0 billion |

April 2, 2018 |

fruits, vegetables, wine, meats, steel products, aluminum waste, and other items |

|

Turkey |

$1.8 billion |

June 21, 2018, initially, and an additional raise in tariffs rates was announced on August 14, 2018a |

foodstuffs, paper, plastic, structural steel, machinery, vehicles, and other items |

|

European Union (EU) 1st Set |

$3.2 billion |

June 20, 2018 |

steel and aluminum products, bourbon whiskey, motorcycles, tobacco products, pleasure boats, and other items |

|

EU 2nd Set |

$4.2 billion |

2021 |

cranberries, denim jeans, footwear, washing machines, and other items |

|

Canada |

$12.7 billion |

July 1, 2018 |

steel, aluminum, coffee, ketchup, orange juice, paper products, and other consumer goods |

|

Mexico |

$3.7 billion |

June 5, 2018, for the majority of products, with remaining effective July 5, 2018b |

pork, apples, potatoes, bourbon, cheeses, and other items |

|

Russia 1st Set |

$0.35 billion |

Announced on July 6, 2018c |

road construction equipment, oil and gas equipment, tools and other items |

|

Russia 2nd Set |

TBD |

2021 |

TBD |

|

India |

$1.4 billion |

September 18, 2018 |

nuts, apples, steel products, motorcycles, and other items |

Source: Global Trade Atlas, compiled from partner countries' 2017 import data for U.S. products; products targeted by retaliatory tariffs were identified in countries' World Trade Organization notifications (China (G/L/1218, March 29, 2018); India (G/L/1237/Rev 1, June 13, 2018); EU (G/L/1237; May 18, 2018); Turkey (G/L/1242, May 21, 2018); Russia (G/L/1241, May 22, 2018), and in the notices published by Canada, Mexico, Russia, and Turkey on their own government websites. Canada: Department of Finance (Canada), "Countermeasures in Response to Unjustified Tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum products," June 29, 2018, https://www.fin.gc.ca/access/tt-it/cacsap-cmpcaa-1-eng.asp; Mexico: Ministry of Finance (Mexico), Diario Oficial de la Federacion, June 5, 2018, http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5525036&fecha=05/06/2018; Russia: Russian Federation, "Approval of rates of import duties in respect to certain goods from the United States," Decision no. 788. July 6, 2018, http://www.pravo.fso.gov.ru/laws/acts/53/555656.html; Turkey: Government of Turkey, "American merchandise subject to additional import tariffs," Decision no. 21, Official Gazette of Turkey, August 14, 2018, http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2018/08/20180815-6.pdf.

Notes: Under WTO rules on safeguards, countries facing new safeguard tariffs may impose their own retaliatory tariffs that would result in an equivalent amount of tariff collection. These retaliatory tariffs (which the WTO refers to as the suspension of trade concessions) must be delayed three years if the safeguard tariffs were a result of an absolute increase in imports. The EU retaliation list split into two lists is an example.

a. Turkey announced on August 18, 2018, an increase in its retaliatory tariff rates, in response to the Trump Administration's decision to increase the U.S. tariffs on Turkish steel to 50%. It is unclear from the notice when these additional tariff rates went fully into effect.

b. One commodity code listed on Mexico's notice is newly established and does not have any reported data for 2017; to estimate the amount of trade, CRS used the higher-level 6-digit version of the code (160100).

c. A Russian government notice states retaliation will target $87.6 million in duty collection initially, with an additional $450 million in duty collection in 2021. (Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation, "Russia introduced compensatory measures in connection with the application of the US additional import duties on steel and aluminum," July 7, 2018, available [in Russian] at http://economy.gov.ru/minec/press/news/201806072, and "Russia Hits Back at U.S. Trade Tariffs by Increasing Import Duties on American Goods," Independent, July 6, 2018.)

d. Russia published its list of retaliatory tariffs rates and products on July 6, 2018. The tariffs appear to go into effect within 30 days of the publication.

FTA partner countries may also claim that the increase in U.S. tariff rates violates U.S. FTA commitments and seek recourse through those agreements. For example, Canada and Mexico, U.S. partners in NAFTA, claimed that the U.S. actions violate commitments in both NAFTA and the WTO agreements. Canada is launching a dispute under the FTA's dispute settlement provisions in addition to actions at the WTO, and began imposing tariffs on up to $12.7 billion of U.S. exports of steel, aluminum, and other products in July.5960 Mexico also published its list of retaliatory tariffs on agricultural and other products that affect approximately $3.75 billion in U.S. exports.60

The prospect of escalating tariffs by U.S. trading partners in retaliation to the Section 232 tariff actions by the Trump Administration magnifies the potential effects of the Section 232 tariffs. From an economic perspective, retaliation increases the scope of industries affected by the tariffs. U.S. farmers, for example, have consistently voiced concern that agriculture exports are being targeted for retaliation and fear losing market share abroad if they are displaced by suppliers from other countries.6162 Some economic models also estimate that retaliation could significantly increase the potential drag on economic growth, while some show minimal impact.

Retaliatory actions may also heighten concerns over the potential strain the Section 232 tariffs place on the international trading system. Many U.S. trading partners view the Section 232 actions as protectionist and in violation of U.S. commitments at the WTO and in U.S. FTAs, while the Trump Administration views the actions within its rights under those same commitments.6263 If the dispute settlement process in those agreements cannot satisfactorily resolve this conflict, it could lead to further unilateral actions and a tit-for-tat process of increasing retaliation.

WTO Implications

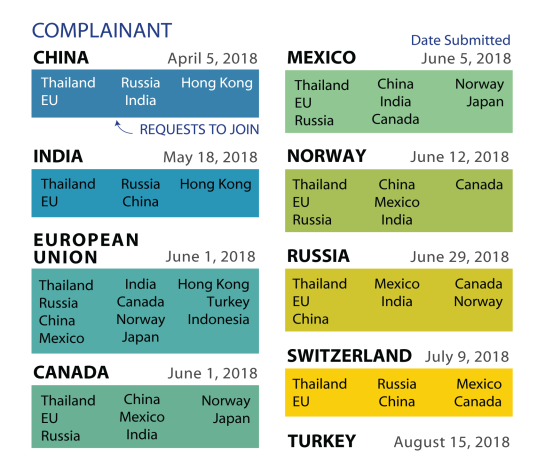

The President's imposition of tariffs on certain imports of steel and aluminum products,6364 as well as Commerce's exemption of certain WTO members' products from such tariffs, may have implications for the United States under WTO agreements. On April 9, 2018, China took the first step in challenging the executive branch's actions as violating U.S. obligations under the WTO agreements (particularly the Agreement on Safeguards) by requesting consultations with the United States.6465 Under WTO dispute settlement rules, members must first attempt to settle their disputes through consultations. If these fail, the member initiating a dispute may request the establishment of a dispute settlement panel composed of trade experts to determine whether a country has violated WTO rules.6566 In addition to China, other WTO members have requested consultations with the United States, or joined existing requests (see Figure 5).

In its request, China alleged that the U.S. tariff measures and exemptions are contrary to U.S. obligations under several provisions of the GATT, the foundational WTO agreement that sets forth binding international rules on international trade in goods.6667 In particular, China alleged that the measure violates GATT Article II, which generally prohibits members from imposing duties on imported goods in excess of upper limits to which they agreed in their Schedules of Concessions and Commitments.6768 It further alleged that Commerce's granting of exemptions from the import tariffs to some WTO member countries, but not to China, violates GATT Article I, which obligates the United States to treat China's goods no less favorably than the goods of other WTO members (i.e., most-favored-nation treatment).6869 China also maintained that the Section 232 tariff measures are "in substance" a safeguards measure intended to alleviate injury to a domestic industry from increased quantities of imported steel that competes with domestic steel, but that the United States did not make the proper findings and follow the proper procedures for imposing such a measure as required by the GATT and WTO Safeguards Agreement.6970

|

Figure 5. WTO Cases Related to the U.S. Section 232 Actions As of August 20, 2018 |

|

|

Source: CRS based on WTO filings. |

The United States has invoked the so-called national security exception in GATT Article XXI in defense of the steel and aluminum tariffs. GATT Article XXI states, in relevant part, that the GATT7071 will not

be construed . . . to prevent any [member country] from taking any action which it considers necessary for the protection of its essential security interests

. . .

(ii) relating to the traffic in arms, ammunition and implements of war and to such traffic in other goods and materials as is carried on directly or indirectly for the purpose of supplying a military establishment; [or]

(iii) taken in time of war or other emergency in international relations. . .

Historically, the United States has taken the position that this exception is self-judging—or, in other words, once a WTO member has invoked the exception to justify a measure potentially inconsistent with its WTO obligations, a WTO panel may not proceed to the merits of the dispute and cannot evaluate whether the WTO member's use of the exception is proper.7172 Though this exception has been invoked several times throughout the history of the WTO and its predecessor agreement, the GATT 1947, it has yet to be interpreted by a WTO dispute settlement panel.7273 Accordingly, there is little guidance as to (1) whether a WTO panel would decide, as a threshold matter, that it had the authority to evaluate whether the United States' invocation of the exception was proper; and (2) how a panel might apply the national security exception, if invoked, in any dispute before the WTO involving the new steel and aluminum tariffs. In the past, however, WTO members have expressed concern that overuse of the exception will undermine the world trading system because countries might enact a multitude of protectionist measures under the guise of national security.73

If the dispute over steel and aluminum tariffs proceeds to a WTO panel, and the panel renders an adverse decision against the United States, the United States would be expected to remove the tariffs, generally within a reasonable period of time, or face the possibility of paying compensation to the complaining member or being subject to sanctions.7475 Such sanctions might include the complaining member imposing higher duties on imports of selected products from the United States.7576 However, China has already begun imposing its own duties on selected U.S. exports without awaiting the outcome of a dispute settlement proceeding,7677 perhaps because it often takes years before the WTO's Dispute Settlement Body authorizes a prevailing WTO member to retaliate.7778 In turn, the United States has argued that China's unilateral imposition of tariffs in response to the U.S. Section 232 measures cannot be justified under WTO rules.78

International Efforts to Address Overcapacity

OECD analysis has found that ongoing global steel overcapacity and excess production have been largely caused by government intervention, subsidization, and other market-distorting practices, although these are not the only factors.7980 Other reasons for excess capacity include cyclical market downturns. The situation is similar in the aluminum industry, where government financial support for large aluminum stockpiles has delayed the response to lower demand.

Past Administrations have worked to address the issue of steel overcapacity. President George W. Bush, for example, initiated international discussions on global capacity reduction and improved trade discipline in the steel industry as part of his general steel announcement of 2001.8081 Other governments agreed to join the Bush Administration in discussing overcapacity and trade issues at the OECD in a process that started in mid-2001. The industrial, steel-producing members of the OECD were joined by major non-OECD steel producers, such as India, Russia, and, during later stages of the talks, China. Negotiations were suspended indefinitely in 2004, and by 2005, the OECD had abandoned its efforts to negotiate an agreement among all major steel-producing countries to ban domestic subsidies for steel mills.

The Obama Administration also participated in international efforts to curb steel imports, including the launch of the G-20 Global Forum on Steel Excess Capacity in 2016, another venue that sought to address the challenges of excess capacity in steel worldwide.8182 In December 2016, the G-20 convened its first meeting of more than 30 economies—all G-20 members plus interested OECD members—as a global platform to discuss steel issues among the world's major producers.8283 The same year, as part of the U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue (SE&D) established in 2009, the Obama Administration agreed to address excess steel production and also to communicate and exchange information on surplus production in the aluminum sector.8384

In November 2017, the OECD Forum published a report with policy recommendations to address excess capacity. The recommendations include enhancing markets by fostering a level playing field, refraining from market-distorting subsidies and support measures, encouraging adjustment and capacity reduction, and sharing data on policies and trends. At a March 2018 Forum meeting, members discussed increasing transparency of domestic production and other policies, but did not agree on specific actions. Without specific actions, however, it is unclear if the Forum can achieve its goal of reducing overcapacity.

The Trump Administration's Section 232 actions have led multiple U.S. trading partners such as the EU and Canada to initiate their own safeguard investigations to prevent dumping of steel and aluminum exports and protect domestic industries. Unlike the OECD efforts, the individual country safeguard actions are uncoordinated.

In addition to the Section 232 action, the Trump Administration is pursuing joint action on industrial overcapacity. The United States Trade Representative, Ambassador Lighthizer, met with his EU and Japanese counterparts in Paris in May 2018, and the three countries agreed to concrete steps to address "nonmarket-oriented policies and practices that lead to severe overcapacity, create unfair competitive conditions for our workers and businesses, hinder the development and use of innovative technologies, and undermine the proper functioning of international trade."8485 The ministers agreed to work toward negotiation of new international rules on subsidies and state-owned enterprises and improved compliance with WTO transparency commitments.8586 The parties also agreed to cooperate on their concerns with third parties' technology transfer policies and practices8687 and issued a joint statement containing a list of factors that identify if market conditions for competition exist.8788 U.S. unilateral actions, however, may limit other countries' willingness to participate in multilateral forums.88

Potential Economic Impact

The Section 232 tariffs have begun to affect various stakeholders in the U.S. economy, prompting reactions from several Members of Congress, some in support and others voicing concern. Congress has also held a number of hearings to examine the issue. The House Ways and Means Committee held hearings examining the potential economic implications of the tariffs and the product exclusion process, and its Trade Subcommittee held a hearing on the effects on U.S. agriculture producers. The Senate Finance Committee also held a hearing with Commerce Secretary Ross to discuss the Administration's Section 232 investigations.8990 In general, the tariffs are expected to benefit the domestic steel and aluminum producers, leading to potential higher steel and aluminum prices and expansion in production in those sectors, while potentially negatively affecting consumers and downstream domestic industries (e.g., manufacturing and construction) due to higher costs of input materials. In addition, retaliatory tariffs by other countries may impact U.S. exports, magnifying the negative impact of the Section 232 tariffs as noted earlier.

Economic Dynamics of the Tariff Increase

Changes in tariffs affect economic activity directly by influencing the price of imported goods and indirectly through changes in exchange rates and real incomes. The extent of the price change and its impact on trade flows, employment, and production in the United States and abroad depend on resource constraints and how various economic actors (foreign producers of the goods subject to the tariffs, producers of domestic substitutes, producers in downstream industries, and consumers) respond as the effects of the increased tariffs reverberate throughout the economy. The following outcomes are generally expected at the level of individual firms and consumers:

- The price of the imported steel and aluminum products is likely to increase. The magnitude of the price increase will depend on a number of factors. The extent of country exemptions and product exclusions will determine the scope of imports affected. Meanwhile, the ability of foreign producers to lower their own prices and absorb a portion of the tariff increase will determine the extent the tariffs are "passed through" to downstream industries and consumers.

U.S. firms have begun paying increased prices for steel and aluminum purchased from abroad. For example, CP Industries, a maker of steel cylinders based in McKeesport, PA, has begun paying tariffs on imports of certain Chinese steel pipes it asserts cannot be produced in sufficient quantity in the United States to meet its demands.9091 The company claims this raises the costs of its production by roughly 10%. The higher input costs potentially give foreign competitors an advantage in the U.S. market and abroad. - Demand for the imported goods facing the tariffs is likely to decrease, while demand for those goods produced domestically or imported from countries excluded from the tariff is likely to increase. Consumers and downstream firms' sensitivity to the price increase (their price elasticity of demand) will depend in large part on the degree to which the steel and aluminum products produced domestically, or imported from exempted countries, are sufficient substitutes for the products facing the tariffs.

- The price and output of steel and aluminum produced domestically or imported from countries exempted from the tariffs are likely to increase. As consumers of the products facing the tariffs shift their demand to lower- or zero-tariff substitutes, domestic producers are likely to respond with a combination of increased output and prices.

9192 Resource constraints that may limit or slow an expansion of output could cause prices to increase more rapidly. The low U.S. unemployment rate suggests such constraints may include frictions in shifting labor from other domestic industries into steel and aluminum production.9293 In addition to reacting to higher-cost production and supply constraints, domestic steel and aluminum producers may also increase prices simply as a strategic response to the higher prices charged by their foreign competitors subject to the tariffs.9394

In an anticipation of higher domestic demand and the ability to charge higher prices on U.S. steel and aluminum, some producers have announced investment and production increases. For example, U.S. Steel Corporation has announced plans to reopen two blast furnaces in Granite City, IL, and Century Aluminum has stated its intent to increase production at a facility in Kentucky.9495 Additional shifts in U.S. production are likely once the effects of the tariffs on U.S. market conditions become clear. - Input costs for downstream domestic producers are likely to increase. As prices likely rise in the United States for the goods subject to the tariffs, domestic industries that use steel and aluminum in their products ("downstream" industries, such as auto manufacturers and oil producers) will face higher input costs. Higher input costs for downstream domestic producers are likely to lead to some combination of lower profits for producers and higher prices for consumers, which in turn, could dampen demand for downstream products and result in a reduction of output in these sectors, and possibly employment declines. For example, press reports state that Mid Continent Nail Corporation of Missouri, a manufacturer reliant on imported steel wire, could be forced to shut down operations, including 500 manufacturing jobs, as a result of the tariffs.

9596

- Industries unrelated to steel and aluminum could face negative consequences due to retaliation by the countries facing the Section 232 tariffs as well as a general slowdown in trade volumes. Canada, China, Mexico, and the EU, the four largest U.S. export markets, have now imposed retaliatory tariffs on U.S. exports, including many U.S. agricultural goods. The retaliatory tariffs would be expected to decrease demand for U.S. exports and would give U.S. exporters an incentive to manufacture abroad to avoid the tariffs. For example, Harley Davidson has announced its intent to shift some of its production out of the United States in order to remain competitive in the EU market.

96

97Workers and firms involved in the shipping and transportation industries could also face downward pressure on demand if trade slows. For example, the Northwest Seaport Alliance (NWSA) representing the ports of Tacoma and Seattle estimates that approximately $8 billion in annual trade through their ports will be affected by U.S. Section 232 tariffs and corresponding foreign retaliatory tariffs.9798 If the tariffs reduce trade volumes, as economic models would generally suggest, this could reduce employment in the shipping and transportation industries.

Aggregating these microeconomic effects, tariffs also have the potential to affect macroeconomic variables, although these impacts may be limited in the case of the Section 232 tariffs, given their focus on two specific commodities with potential exemptions, relative to the size of the U.S. economy. With regard to the value of the U.S. dollar, as demand for foreign goods potentially falls in response to the tariffs, U.S. demand for foreign currency may also fall, putting upward pressure on the relative exchange value of the dollar. Tariffs may also affect national consumption patterns, depending on how the shift to higher-cost domestic substitutes affects consumers' discretionary income and therefore aggregate demand. Finally, given their ad hoc nature, these tariffs, in particular, are also likely to increase uncertainty in the U.S. business environment, potentially placing a drag on investment.

Assessing the Overall Economic Impact

From a global standpoint, tariff increases on steel and aluminum are likely to result in an unambiguous welfare loss due to what most economists consider is a misallocation of resources caused by shifting production from lower-cost to higher-cost producers. On the other hand, some see the Administration's trade actions as addressing long-standing issues of fairness that are intended to provide U.S. producers with a more level playing field. Looking solely at the domestic economy, the net welfare effect is unclear, but also likely negative. Generally, economic models would suggest the negative impact of higher prices on consumers and industries using the imported goods is likely to outweigh the benefit of higher profits and expanded production in the import-competing industry and the additional government revenue generated by the tariff. It is theoretically plausible to generate an overall positive welfare effect for the domestic economy if the foreign producers absorb a large enough portion of the tariff increase. Given the current excess capacity and intense price competition in the global steel and aluminum industries, however, this level of tariff absorption by foreign firms seems unlikely. Moreover, retaliation by foreign governments would erode this welfare gain.

The direct economic effects of the Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum may be limited due to the relatively small share of economic activity directly affected. The recent extension of the steel and aluminum tariffs to U.S. imports from Canada, Mexico, and the EU is economically significant, as these trading partners accounted for nearly 50% of U.S. imports of both products by value in 2017. However, these products still represent a relatively small share of total U.S. imports: in 2017 U.S. steel and aluminum imports were $29 billion and $17 billion, respectively, roughly 2% of all U.S. imports. Various stakeholder groups have prepared quantitative estimates of the costs and benefits across the economy. Specific estimates from these studies should be interpreted with caution given their sensitivity to modeling assumptions and techniques, but generally they suggest a small negative overall effect on U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) from the tariffs with employment shifts into the domestic steel and aluminum industries and away from other sectors in the economy.98

Ultimately the economic significance of the tariffs will largely depend on variables that remain in flux: the range of product exclusions, further negotiations on country exemptions, and the degree to which other countries retaliate. A range of U.S. stakeholders have objected to the Administration extending the tariffs to Canada, Mexico, and the EU, and the Administration states that negotiations remain ongoing, suggesting the possibility of future adjustments to the tariff coverage. Meanwhile, more than 27,000 product exclusions have been filed, which if granted would limit the economic impact of the trade measures. Finally, retaliation has an immediate negative economic impact on the industries subject to retaliatory tariffs, and could set off a tit-for-tat process of increasing global protectionism, reducing trade and causing significant growth declines. For example, analysis by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas estimates that an extreme scenario of prohibitively high retaliatory tariffs affecting all U.S.-China and U.S.-EU goods trade could result in a reduction of U.S. GDP by 3.5%.99

Section 232 Auto Investigation

As mentioned, subsequent to the steel and aluminum investigations, the Trump Administration initiated a third Section 232 investigation into the imports of automobiles, including SUVs, vans and light trucks, and automotive parts. The Commerce Department requested comments from stakeholders on the impact of these imports on national security, identifying a broad set of factors related to national defense and the national economy for consideration.100101 As many foreign auto manufacturers have established facilities in the United States, Commerce specifically requested information on how the impact may differ when accounting for "U.S. production by majority U.S.-owned firms is considered separately from U.S. production by majority foreign-owned firms."

The value of U.S. imports potentially covered under the new investigation is significantly greater than that of steel and aluminum imports. With a complex global supply chain, industry dynamics such as the existence of foreign-owned auto manufacturing facilities in the United States, and the potential for further retaliation by trading partners if tariffs are imposed as a result of the investigation, the economic consequences could be substantial.101102 According to Ford Motor Co.'s executive vice president and president of global operations, Joe Hinrichs, "the auto industry is a global business. The benefits of scale and global reach are important ... The big companies that we compete against—Toyota, Volkswagen, General Motors, Nissan, Hyundai, Kia—are all global in nature because we realize the benefits of sharing the engineering, the platforms and the scale and our supply base."102

Some Members and auto industry representatives have spoken out in opposition to the new Section 232 investigation. The National Association of Manufacturers, for example, raised concerns of potential "unintended consequences for U.S. manufacturing workers that will limit the chance for Americans to win,"103104 while others have opined that the investigation is a tactical move by the Administration to pressure trade negotiating partners.104105 Three groups have voiced support for at least limited measures to address auto imports: United Automobile Workers, the United Steelworkers, and the Forging Industry Association.105

Issues for Congress

As Congress debates the Administration's Section 232 actions it may consider the following issues, many of which include potential legislative responses.

Appropriate Delegation of Constitutional Authority

In establishing Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, Congress delegated aspects of its authority to regulate international commerce to the Administration. Use of the statute to restrict imports does not require any formal approval by Congress or an affirmative finding by an independent agency, such as the U.S. International Trade Commission, granting the President broad discretion in applying this authority. Should Congress disapprove of the President's use of the statute, its current recourse is limited to passing new legislation or using informal tools to pressure the Administration (e.g., putting holds on presidential nominee confirmations). Some Members and observers have suggested that Congress should require additional steps in the Section 232 process, such as requiring an economic impact study by the U.S. International Trade Commission, congressional consultation or approval of any new tariffs (see, for example, S. 3013), or allowing for a resolution of disapproval as exists in the case of petroleum. In addition, some Members and observers have suggested that Congress should revisit the delegation of its constitutional authority more broadly, such as by requiring congressional review of executive branch trade actions generally (see, for example, H.R. 5760 and S. 177).

Interpreting National Security

Congress created the Section 232 process to ensure that U.S. imports do not cause undue harm to U.S. national security. Some observers have raised concerns that restrictions on U.S. imports under Section 232, however, may harm U.S. allies, which could also have negative implications for U.S. national security. For example, Canada is considered part of the U.S. defense industrial base according to U.S. law and is also a top source of U.S. imports of steel and aluminum.106107

National security is not clearly defined in the statute, allowing for ambiguity and alternative interpretations by an Administration. International trade commitments both at the multilateral and FTA level generally include broad exceptions on the basis of national security. The Trump Administration argues its Section 232 actions are permissible under these exceptions, while many U.S. trading partners claim the actions are unrelated to national security. If the United States invokes the national security exemption in what may be perceived to be an arbitrary way, it could similarly encourage other countries to use national security as a rationale to enact protectionist measures and limit the scope of potential U.S. responses to such actions.

Congress may consider amending Section 232 to address these concerns. For example, Congress could more explicitly define "national security" and the factors to be considered in a Section 232 investigation. Alternatively, Congress could consider an amendment to Section 232 similar to the option for congressional disapproval for Section 232 actions related to oil or petroleum.

Establishing New International Rules

Addressing the specific market-distorting practices that are the root causes of steel and aluminum overcapacity (e.g., government intervention, subsidization) may require updating or amending existing agreements. Negotiations for new multilateral rules, which attempt to address some of these issues, have stalled.107108 Recent U.S. FTA negotiations, including the negotiations on revisions to NAFTA, have included related disciplines (e.g., by establishing rules on state-owned enterprises or anticorruption), but the United States is not currently engaged in an FTA negotiation with China or other key countries driving overcapacity. To address these issues, Congress could consider establishing specific or enhanced new negotiating objectives for trade agreement negotiations, potentially through new or modified Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) legislation. Congress could also consider directing the executive branch to prioritize engagement in such negotiations, by, for example, endorsing the current trilateral negotiations announced by USTR with the EU and Japan to address nonmarket practices, including subsidies, state-owned enterprises, and technology transfer requirements, mostly aimed at China.

Effects on Trade Liberalization Efforts

Some argue that the U.S. unilateral tariff actions could limit other countries' interest in engaging in negotiations to reduce international barriers—efforts historically championed by the United States. Such concerns are amplified given the proliferation of trade liberalization agreements outside the context of the WTO and therefore with the potential for discriminatory effects on countries not participating, including the United States.108109 To address this concern, Congress could investigate, or ask the U.S. International Trade Commission to investigate, the potential strategic and economic value to the United States of engaging in negotiations to join existing or establish new trade agreements.

Impact on the Multilateral Trading System

Some analysts argue that the United States risks undermining the international system it helped create when it invokes unilateral trade actions that may violate core commitments and with regard to broad use of national security exemptions. These observers fear that disagreements at the WTO on these issues may be difficult to resolve through the existing dispute settlement procedures given the concerns over national sovereignty that would likely be raised if a WTO dispute settlement panel issued a ruling relating to national security. Furthermore, actions by the United States that do not make use of the multilateral system's dispute settlement process may open the United States to criticism and could impede U.S. efforts to use the multilateral system for its own enforcement purposes. For example, China recently called on other parties such as the EU to join it in opposition to the U.S. actions on Section 232, while simultaneously promoting domestic policies often seen as undermining WTO rules.109110 Congress could potentially address these concerns by conducting increasing oversight of the Trump Administration's actions by inviting testimony from multiple parties and also, considering legislation to establish more stringent criteria, or requiring congressional approval of any use of Section 232, among other possible actions.

Impact on Broader International Relationships

The U.S. unilateral actions under Section 232 have raised the level of tension with U.S. trading partners and could pose risks to broader international economic cooperation. For example, trade tensions between the United States and its traditional allies contributed to the lack of consensus at the conclusion of the recent G-7 summit in June 2018.110111 The strain on international trading relationships also could have broader policy implications, including for cooperation between the United States and allies on foreign policy issues.

Appendix A. Amendments to and Past Uses of Section 232 (19 U.S.C. §1862)

Concern over national security, trade, and domestic industry was first raised by the Trade Agreements Extension Act of 1954 (P.L. 83-464 §2). The 1954 act prohibited the President from decreasing duties on any article if the President determined that such a reduction might threaten domestic production needed for national defense.111112 In 1955, the provision was amended to also allow the President to increase trade restrictions, in cases where national security may be threatened.112

The Trade Agreements Extension Act of 1958 (P.L. 85-686 §8) expanded the 1955 provisions, by outlining specific factors to be considered during an investigation, allowing the private sector to petition for relief, and requiring the President to publish a report on each petition.113114 The factors to be considered during an investigation included (1) the domestic production capacity needed for U.S. national security requirements, (2) the effect of imports on domestic production needed for national security requirements, and (3) "the impact of foreign competition on the economic welfare of individual domestic industries."

Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 (P.L. 87-794) continued the provisions of the 1958 Act. Section 232 has been amended multiple times over the years, including (1) to change the time limits for investigations and actions; (2) to change the advisory responsibility from the Secretary of the Treasury to the Secretary of Commerce; and (3) to limit presidential authority to adjust petroleum imports.114

In 1980, Congress amended Section 232 to create a joint disapproval resolution provision under which Congress could override presidential actions to adjust petroleum or petroleum product imports.115116 The bill was signed into law on April 2, 1980, the same day that President Carter proclaimed a license fee on crude oil and gasoline pursuant to Section 232 in Proclamation 4744.116