Venezuela: Background and U.S. Relations

Changes from June 27, 2018 to January 21, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Recent Developments

- Introduction

- Political Situation

- Legacy of Hugo Chávez (1999-2013)

- Maduro

Administration - Canceled Recall Referendum and Failed Dialogue Efforts in 2016

- Repression of Dissent and Human Rights Violations

- Despite Opposition, Constituent Assembly Elected

- Maduro's Efforts to Consolidate Power Before the May 2018 Elections

- May 2018 Elections and Aftermath

- Foreign Relations and Responses to the Maduro Government

- Economic Crisis

- Developments in Venezuela's Energy Sector

- Debt and Default

- Humanitarian Situation

- Overview

- Population Displacement and Humanitarian Needs in the Border Regions

- International Appeals for Assistance

- Repression of Dissent, Establishment of a Constituent Assembly in 2017

- Efforts to Consolidate Power Before the May 2018 Elections

- May 2018 Elections

- Lead-Up to Maduro's January 2019 Inauguration and Aftermath

- Human Rights

- Economic Crisis

- Developments in 2018

- Prospects for 2019

- Energy Sector Challenges

- Humanitarian Situation

- Regional Migration Crisis

- Foreign Relations

- Latin America and the Lima Group

- China and Russia

- U.S. Policy

- U.S. Democracy Assistance

- U.S. Humanitarian and Related Assistance

- Targeted Sanctions Related to Antidemocratic Actions, Human Rights Violations, and Corruption

- Sanctions Restricting Venezuela's Access to U.S. Financial Markets

- Organized Crime-Related Issues

- Counternarcotics

- Money Laundering

- Illegal Mining

- Colombian Illegally Armed Groups Operating in Venezuela

Terrorism- Energy Sector Concerns and Potential U.S. Sanctions

- U.S. Support for Organization of American States

(OAS)Efforts on Venezuela - Outlook

Figures

Summary

Venezuela remains in a deep political crisis under the authoritarian rule of President Nicolás Maduro of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). On May 20, 2018, Maduro defeated Henri Falcón, a former governor, in a presidential election boycotted by the Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD) of opposition parties and dismissed by the United States, the European Union, and 18 Western Hemisphere countries as illegitimate. Maduro, who was narrowly elected in 2013 after the death of President Hugo Chávez (1999-2013), is unpopular. Nevertheless, he has used the courts, security forces, and electoral council to repress the opposition.

On January 10, 2019, Maduro began a second term after winning reelection on May 20, 2018, in an unfair contest deemed illegitimate by the opposition-controlled National Assembly and most of the international community. The United States, the European Union, the Group of Seven, and most Western Hemisphere countries do not recognize the legitimacy of his mandate. They view the National Assembly as Venezuela's only democratic institution. Maduro's reelection capped off his efforts since 2017 to consolidate power. From March to July 2017, protesters called for President Maduro to release political prisoners and respect the MUDMaduro, narrowly elected in 2013 after the death of Hugo Chávez (1999-2013), is unpopular. Nevertheless, he has used the courts, security forces, and electoral council to repress the opposition.

to rewrite the constitution; the; this assembly then assumed legislative functions. The PSUV dominated gubernatorial and municipal elections held in 2017, although fraud likely occurred in those contests. Maduro has arrested dissident military officers and others, but he also has released some political prisoners, including U.S. citizen Joshua Holt, since the May electionhas usurped most legislative functions. During 2018, Maduro's government arrested dissident military officers and others suspected of plotting against him. Efforts to silence dissent may increase, as the National Assembly (under its new president, Juan Guaidó), the United States, and the international community push for a transition to a new government.

Venezuela also is experiencing a serious economic crisis, marked byand rapid contraction of the economy, hyperinflation, and severe shortages of food and medicine have created a humanitarian crisis. President Maduro has blamed U.S. sanctions and corruption for these problems, while conditioning receipt of food assistance on support for his government and increasing military control over the economy. He maintains that Venezuela will seek to restructure its debts, although that appears unlikely. The government and state oil company Petróleos de Venezuela, S. A. (PdVSA) defaulted on bond payments in 2017. Lawsuits over nonpayment and seizures of PdVSA assets are likely.

U.S. Policy

The United States historically had close relations with Venezuela, a major U.S. oil supplier, but relations have deteriorated under the Chávez and Maduro governments. U.S. policymakers have expressed concerns about the deterioration of human rights and democracy in Venezuela and the country's lack of lack of bilateral cooperation on counternarcotics and counterterrorism efforts. U.S. democracy and human rights funding, which totaledtotaling $15 million forin FY2018 (P.L. 115-141), has bolstered civil society in Venezuelaaimed to support civil society.

The Trump Administration has employed targeted sanctions against Venezuelan officials responsible for human rights violations, undermining democracy, and corruption. In August 2017, President Trump imposed economic sanctions that restrict the ability of the government and PdVSA to access U.S. financial markets; he imposed new sanctions following the May 2018 election prohibiting U.S. purchases of Venezuelan debt. Additional sanctions on Venezuela's oil sector are possible but could hurt the Venezuelan people. The Trump Administration has announced the provision of $39.5 million in assistance for Venezuelans who have fled to other countries.

Congressional Action

Congressional Action The 116th Congress likely will fund foreign assistance to Venezuela and neighboring countries sheltering Venezuelans. Congress may consider additional steps to influence the Venezuelan government's behavior in promoting a return to democracy and to relieve the humanitarian crisis.The 115th Congress has taken, as well as on individuals and entities engaged in drug trafficking. Since 2017, the Administration has imposed a series of broader sanctions restricting Venezuelan government access to U.S. financial markets and prohibiting transactions involving the Venezuelan government's issuance of digital currency and Venezuelan debt. The Administration provided almost $97 million in humanitarian assistance to neighboring countries sheltering more than 3 million Venezuelans.

supportssupported targeted sanctions. In December 2017, the House passed H.R. 2658 (Engel), which would authorizehave authorized humanitarian assistance for Venezuela (a similar Senate bill, S. 1018 [Cardin], has been introduced), and H.Res. 259 (DeSantis), which urges the urged the Venezuelan government to accept humanitarian aid. For FY2019, the Administration requested $9 million in democracy and human rights funds for Venezuela. The 115th Congress did not complete action on the FY2019 foreign assistance appropriations measure. The House version of the FY2019 foreign aid appropriations bill, H.R. 6385, would have provided $15 million for programs in Venezuela; the Senate version, S. 3108, would have provided $20 million.

government to accept humanitarian aid. Some Members of Congress have called for an adjustment to permanent resident status for certain Venezuelans in the United States (H.R. 2161 [Curbelo]). S.Res. 363 (Nelson), introduced in December 2017, would express concern about the humanitarian crisis. S.Res. 414 (Durbin), introduced in February 2018, would condemn the undemocratic practices of the government. The Administration requested $9 million in democracy assistance for Venezuela in FY2019. The House Appropriation Committee's version of the State Foreign Operations measure would provide $15 million; the Senate Appropriations Committee's version (S. 3108) would provide $20 million.

See CRS In Focus IF10230, Venezuela: Political and Economic Crisis and U.S. Policy; CRS In Focus IF10715, Venezuela: Overview of U.S. Sanctions; and CRS In Focus IF10857, Venezuela's Petroleum Sector and U.S. Sanctions; and CRS Report R45072, Venezuela's Economic Crisis: Issues for CongressIF11029, The Venezuela Regional Migration Crisis.

Recent Developments

On June 25, 2018, the European Union (EU) announced targeted sanctions against 11 Venezuelan officials, including Vice President Delcy Rodríguez. (See "Sanctions by Canada and the European Union, Criticism by U.N. Officials," below.)

On June 22, 2018, the U.N. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNOCHR) issued a report stating, "human rights violations committed during demonstrations form part of a wider pattern of repression against political dissidents and anyone perceived as ... posing a threat" to the Maduro government. It referred the report to the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC). (See "Repression of Dissent and Human Rights Violations," below.)

On June 20, 2018, the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) issued a report citing significant increases in new cases of malaria, measles, diphtheria, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis in Venezuela. The report says that the Venezuelan health system is "under stress" and that some 33% of doctors have emigrated since 2014. (See "Humanitarian Situation," below.)

On June 14, 2018, President Nicolas Maduro announced several Cabinet changes, including his selection of Delcy Rodríguez, president of the National Constituent Assembly (ANC), to serve as vice president. (See "May 2018 Elections and Aftermath," below.)

One June 13, 2018, Rodríguez announced the release of 45 people who had been arrested for taking part in protests; the opposition maintains that only 11 of those individuals were political prisoners. This announcement followed prisoner releases in early June. (See "Repression of Dissent and Human Rights Violations," below.)

On June 4, 2018, Venezuela's oil minister told reporters at an Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) meeting that he hoped to recover lost production by the end of 2018 but that it would be "a challenge." (See "Developments in Venezuela's Energy Sector," below.)

On May 29, 2018, a panel of jurists issued a report confirming that evidence gathered by the General Secretariat of the Organization of American States (OAS) documenting possible crimes against humanity committed by the Venezuelan government merits a referral to the ICC. (See "Appendix B" for OAS action on Venezuela, below.)

On May 26, 2018, the Venezuelan government released Joshua Holt, a U.S. citizen who had been imprisoned for nearly two years, after high-level negotiations. (See "U.S. Policy," below.)

On May 22, 2018, the Maduro government denounced new U.S. sanctions and expelled the top two U.S. diplomats in Caracas; the U.S. State Department responded reciprocally on May 23, 2018. (See "U.S. Policy," below.)

On May 21, 2018, President Trump signed Executive Order (E.O.) 13835 tightening existing sanctions prohibiting U.S. purchases of Venezuelan debt. The State Department called the elections "unfree and unfair." (See "Sanctions Restricting Venezuela's Access to U.S. Financial Markets," below.)

On January 21, 2019, Venezuelan military authorities announced the arrest of 27 members of the National Guard who allegedly stole weapons (since recovered) as they tried to incite an uprising against the government. (See "Lead-Up to Maduro's January 2019 Inauguration and Aftermath," below.) On January 15, 2019, Venezuela's National Assembly declared that President Maduro had usurped the presidency. The legislature also established a framework for the formation of a transitional government led by Juan Guaidó of the Popular Will (VP) party, the president of the National Assembly who was elected on January 5, 2019, to serve until presidential elections can be held (per Article 233 of the constitution). In addition, the legislature approved amnesty from prosecution for public officials who facilitate the transition. (See "Lead-Up to Maduro's January 2019 Inauguration and Aftermath," below.) On January 13, 2019, Venezuela's intelligence service detained, and then released, Juan Guaidó. Two days prior, Guaidó had said he would be willing to assume the presidency on an interim basis until new elections could be held; he also called for national protests to occur on January 23, 2019. (See "Lead-Up to Maduro's January 2019 Inauguration and Aftermath," below.) On January 10, 2019, the U.S. Department of State issued a statement condemning Maduro's "illegitimate usurpation of power" and vowing to "work with the National Assembly ... in accordance with your constitution on a peaceful return to democracy." (See "U.S. Policy," below.) On January 10, 2019, the Organization of American States (OAS) passed a resolution rejecting the legitimacy of Nicolas Maduro's new term. (See Appendix B, below.) On January 10, 2019, President Nicolas Maduro began a second term after a May 2018 election that has been deemed illegitimate by the democratically elected, opposition-controlled National Assembly and much of the international community. (See "Foreign Relations," below.) On January 8, 2019, the U.S. Department of the Treasury imposed sanctions on seven individuals and 23 companies involved in a scheme that stole $2.4 billion through manipulation of Venezuela's currency exchange system under authority provided in Executive Order (E.O.) 13850. (See "Targeted Sanctions Related to Antidemocratic Actions, Human Rights Violations, and Corruption," below.) On December 17, 2018, a group of investors demanded the Venezuelan government pay off the interest and principal of a defaulted $1.5 billion bond, the first step in a potential legal process by creditors to recover their assets. (See "Prospects for 2019," below.) On December 14, 2018, El Nacional, Venezuela's last independent newspaper with national circulation, stopped publishing its print edition after 75 years. The move ame after numerous advertising restrictions, lawsuits, and threats from the Venezuelan government. (See "Human Rights," below.)On May 20, 2018, Venezuela held presidential elections that were boycotted by the Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD) coalition of opposition parties. According to the official results, President Nicolás Maduro of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) won reelection for a second six-year term with 67.7% of the vote amid relatively high abstention, as 46% of voters participated. (See "May 2018 Elections and AftermathJanuary 21, 2019, Venezuela's government-aligned Supreme Court issued a ruling declaring the National Assembly illegitimate and its rulings unconstitutional. (See "Lead-Up to Maduro's January 2019 Inauguration and Aftermath," below.)

Introduction

Venezuela, long one of the most prosperous countries in South America with the world's largest proven oil reserves, continues to be in the throes of a deep political, economic, and humanitarian crisis. Whereas populist President Hugo Chávez (1998-2013) governed during a period of generally high oil prices, his successor, Nicolás Maduro of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), has exacerbated an economic downturn caused by low global oil prices withthrough mismanagement and corruption. According to Freedom House, Venezuela has fallen from "partly free" under Chávez to "not free" under Maduro, an unpopular leader who has violently quashed dissent and illegally replaced the legislature with a National Constituent Assembly (ANC) elected under controversial circumstances in July 2017.1 President Maduro won reelection in early elections held on May 20, 2018,in May 2018 that were dismissed as illegitimate by the United States, the European Union (EU), the G-7, and a majority of countries in the Western Hemisphere.2

|

Venezuela at a Glance Population Area: 912,050 square kilometers (slightly more than twice the size of California) GDP: $ GDP Growth GDP Per Capita: $ Key Trading Partners: Exports—U.S.: Unemployment: Life Expectancy: 74. Literacy: Legislature: National Assembly (unicameral), with 167 members ; National Constituent Assembly, with 545 members (United States does not recognized)Sources: Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU); International Monetary Fund (IMF); United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). |

U.S. relations with Venezuela, a major oil supplier, deteriorated during the 14 years of Chávez's rule, which undermined human rights, the separation of powers, and freedom of expression in the country. U.S. and regional concerns have deepened as the Maduro government has manipulated democratic institutions; cracked down on the opposition, media, and civil society; engaged in drug trafficking and corruption; and refused most humanitarian aid. Regional effortsEfforts to hasten a return to democracy in Venezuela have failed thus far failed. President Maduro's convening of the ANC and, most recently, early presidential elections, have triggered international criticism and led to new sanctions by Canada, the EU, Panama, Switzerland, the United States, and potentially others.

This report provides an overview of the overlapping political, economic, and humanitarian crises in Venezuela, followed by an overview of U.S. policy toward Venezuela.

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS). |

Political Situation

Legacy of Hugo Chávez (1999-2013)3

2

In December 1998, Hugo Chávez, a leftist populist representing a coalition of small parties, received 56% of the presidential vote (16% more than his closest rival). Chávez's commanding victory illustrated Venezuelans' rejection of the country's two traditional parties, Democratic Action (AD) and the Social Christian party (COPEI), which had dominated Venezuelan politics for the previous 40 years. Most observers attribute Chávez's rise to power to popular disillusionment with politicians whom they then judged to have squandered the country's oil wealth through poor management and corruption. Chavez's campaign promised constitutional reform; he asserted that the system in place allowed a small elite class to dominate Congress and waste revenues from the state oil company, PdVSAPetróleos de Venezuela, S. A. (PdVSA).

Venezuela had one of the most stable political systems in Latin America from 1958 until 1989. After that period, however, numerous economic and political challenges plagued the country. In 1989, then-President Carlos Andres PerezPérez (AD) initiated an austerity program that fueled riots and street violence in which several hundred people were killed. In 1992, two attempted military coups threatened the PerezPérez presidency, one led by Chávez himself, who at the time was a lieutenant colonel railing against corruption and poverty. Chávez served two years in prison for that failed coup attempt. UltimatelyIn May 1993, the legislature dismissed President PerezPérez from office in May 1993 for misusing public funds. The election of elder statesman and former President Rafael Caldera (1969-1974) as president in December 1993 brought a measure of political stability, but the government faced a severe banking crisis. A rapid decline in the price of oil then caused a recession beginning in 1998, which contributed to Chávez's landslide election.

Under Chávez, Venezuela adopted a new constitution (ratified by a plebiscite in 1999), a new unicameral legislature, and even a new name for the country—the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, named after the 19th century South American liberator Simón Bolívar. Buoyed by windfall profits from increases in the price of oil, the Chávez government expanded the state's role in the economy by asserting majority state control over foreign investments in the oil sector and nationalizing numerous private enterprises. Chávez's charisma, his use of oil revenue to supportfund domestic social programs and provide subsidized oil to Cuba and other Central American and Caribbean countries through a program known as PetroCaribe, and his , and willingness to oppose the United States and other global powers captured internationalcaptured global attention.43

After Chávez's death, his legacy has been debated. President Chávez established an array of social programs and services known as missions that helped to reduce poverty by some 20% and improve literacy and access to health care.54 Some maintain that Chávez also empowered the poor by involving them in community councils and workers' cooperatives.65 Nevertheless, his presidency was "characterized by a dramatic concentration of power and open disregard for basic human rights guarantees," especially after his brief ouster from power in 2002.76 Declining oil production, combined with massive debt and high inflation, have shown the costs involved in Chávez's failure to save or invest past oil profits, tendency to take on debt and print money, and decision to fire thousands of PdVSA technocrats after an oil workers' strike in 2002-2003.87

Venezuela's 1999 constitution, amended in 2009, centralized power in the presidency and established five branches of government rather than the traditional three branches.98 Those branches include the presidency, a unicameral National Assembly, a Supreme Court, a National Electoral Council (CNE), and a "Citizen Power" branch (three entities that ensure that government officials at all levels adhere to the rule of law and that can investigate administrative corruption). The president is elected for six-year terms and can be reelected indefinitely; however, he or she also may be made subject to a recall referendum (a process that Chávez submitted to in 2004 and survived but Maduro cancelled in 2016). Throughout his presidency, Chávez exerted influence over all the government branches, particularly after an outgoing legislature dominated by chavistas appointed pro-Chávez justices to dominate the Supreme Court in 2004 (a move that Maduro's allies would repeat in 2015).

In addition to voters having the power to remove a president through a recall referendum process, the National Assembly has the constitutional authority to act as a check on presidential power, even when the courts have failedfail to do so. The National Assembly consists of a unicameral Chamber of Deputies with 167 seats whose members serve for five years and may be reelected once. With a simple majority, the legislature can approve or reject the budget and the issuing of debt, remove ministers and the vice president from office, overturn enabling laws that give the president decree powers, and appoint the 5 members of the CNE (for 7-year terms) and the 32 members of the Supreme Court (for one 12-year term). With a two-thirds majority, the assembly can remove judges, submit laws directly to a popular referendum, and convene a constitutional assembly to revise the constitution.10

Maduro Administration11

Government10

|

Nicolás Maduro A former trade unionist who served in Venezuela's legislature from 1998 until 2006, Nicolás Maduro held the position of National Assembly president from 2005 to 2006, when he was selected by President Chávez to serve as foreign minister. Maduro retained that position until mid-January 2013, concurrently serving as vice president beginning in October 2012, when President Chávez tapped him to serve in that position following his reelection. Maduro often was described as a staunch Chávez loyalist. Maduro's partner since 1992 is well-known Chávez supporter Cilia Flores, who served as the president of the National Assembly from 2006 to 2011; the two were married in July 2013. |

After the death of President Hugo Chávez in March 2013, Venezuela held presidential elections the following month in which acting President Nicolás Maduro defeated Henrique Capriles of the MUD by 1.5%. The opposition alleged significant irregularities and protested the outcome.

Given his razor-thin victory and the rise of the opposition, Maduro sought to consolidate his authority. Security forces and allied civilian groups violently suppressed protests and restricted freedom of speech and assembly. In 2014, 43 people died and 800 were injured in clashes between progovernmentpro-government forces and student-led protesters concerned about rising crime and violence. President Maduro imprisoned opposition figures, including Leopoldo López, head of the Popular Will (VP) party, who was sentenced to more than 13 years in prison for allegedly inciting violence.12 The Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) initiated a government-opposition dialogue in April 2014, but talks quickly broke down.1311 In February 2015, the Maduro government again cracked down on the opposition.

In the December 2015 legislative elections, the MUD captured a two-thirds majority in Venezuela's National Assembly—a major setback for Maduro. Nevertheless, theThe Maduro government took actions aimed at thwarting the power of the legislatureto thwart the legislature's power. The PSUV-aligned Supreme Court blocked three MUD representativesdeputies from taking office, which deprived the opposition of the two-thirds majority needed to submit bills directly to referendum and remove Supreme Court justices. From January 2016 through August 2017 (when the National Constituent Assembly voted to give itself legislative powers), the Supreme Court blocked numerous laws approved by the legislature and assumed many of its functions.14

Canceled Recall Referendum and Failed Dialogue Efforts in 2016

and assumed many of the legislature's functions.12

In 2016, opposition efforts focused on attempts to recall President Maduro in a national referendum. The government used delaying tactics to slow the process considerably. On October 20, 2016, Venezuela's CNE suspended the recall effort after five state-level courts issued rulings alleging fraud in a signature collection drive that had amassed millions of signatures.

In October 2016, after an appeal by Pope Francis, most of the opposition (with the exception of the Popular Will party) and the Venezuelan government agreed to talks mediated by the Vatican, along with the former leaders of the Dominican Republic, Spain, and Panama and the head of UNASUR. By December 2016, the opposition had left the talks due to what it viewed as a lack of progress on the part of the government in meeting its commitments. Those commitments included (1) releasing political prisoners; (2) announcing an electoral calendar; (3) respecting the National Assembly's decisions; and (4) addressing humanitarian needs.

Repression of Dissent and Human Rights Violations

13

Repression of Dissent, Establishment of a Constituent Assembly in 2017

Far from meeting the commitments it made during the Vatican-led talks, the Maduro government continued to harass and arbitrarily detain opponents (see "Human Rights," below). In addition, President Maduro appointed a hard-linehardline vice president, Tareck el Aissami, former governor of the state of Aragua and a sanctioned U.S. drug kingpin, in January 2017.

In early 2017, the opposition in Venezuela was divided and disillusioned. MUD leaders faced an environment in which popularPopular protests, which were frequent between 2014 and fallautumn 2016, had dissipated. In addition to restricting freedom of assembly, the government had cracked down on media outlets and journalists, including foreign media.1514

Despite these obstacles, the MUD became reenergized in response to the Supreme Court's March 2017 rulings to dissolve the legislature and assume all legislative functions. After domestic protests, a rebuke by then-Attorney General Luisa Ortega (a Chávez appointee), and an outcry from the international community, President Maduro urged the court to revise those rulings, and it complied. In April 2017, the government banned opposition leader and two-time presidential candidate Henrique Capriles from seeking office for 15 years, which fueled more protests.

From March to July 2017, the opposition conducted large and, sustained protests against the government, calling for President Maduro to release political prisoners, respect the separation of powers, and hold an early presidential election (instead of waiting until the end of 2018). Clashes between security forces (backed by armed civilian militias) and protesters left more than 130 dead and hundreds injured.

Former Attorney General Luisa Ortega has presented a dossier of evidence to the International Criminal Court (ICC) that the police and military may have committed more than 1,800 extrajudicial killings as of June 2017. In the dossier, Ortega urged the ICC to charge Maduro and several top officials in his Cabinet with serious human rights abuses.16 An exiled judge appointed by the National Assembly to serve on the "parallel" supreme court of justice also accused senior Maduro officials of systemic human rights abuses before the ICC.17 Ortega's report corroborates much of the evidence published in recent reports on the human rights situation in Venezuela:

- The Venezuelan human rights group Foro Penal and Human Rights Watch maintain that more than 5,300 Venezuelans were detained during the protests. Together, the organizations documented inhumane treatment of more than 300 detainees that occurred between April and September 2017.18

- Amnesty International published a report describing how security forces conducted illegal nighttime raids on private homes to intimidate the population.19

- In addition to these violations, the State Department's Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 2017 found that "human rights deteriorated dramatically" in 2017 as the government tried hundreds of civilians in military courts and arrested 12 opposition mayors for their "alleged failure to control protests."20

- In August 2017, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNOCHR) issued a report on human rights violations perpetrated by the Venezuela security forces against the protestors.21 According to the report, credible and consistent accounts indicated that "security forces systematically used excessive force to deter demonstrations, crush dissent, and instill fear." The U.N. report maintained that many of those detained were subject to cruel, degrading treatment and that in several cases, the ill treatment amounted to torture. UNOCHR called for an international investigation of those abuses. On June 18, 2018, the High Commissioner for Human Rights urged the U.N. Human Rights Council to launch a Commission of Inquiry to investigate those reports.22

- In December 2017, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) released its third report on the situation of human rights in Venezuela.23 The report highlighted the violation of the separation of powers that occurred as President Maduro and the judiciary interfered in the work of the legislature and then replaced it with a constituent assembly. It then criticized state limits on social protests and freedom of expression and said that the government "must curtail the use of force against demonstrators."

- In May 2018, an independent panel of human rights experts added a legal assessment to a report containing information and witness testimonies gathered by the OAS recommending that the ICC should investigate reports that the Venezuelan government committed crimes against humanity.24

These reports published by international human rights organizations, the U.S. government, U.N. entities, and the OAS/IACHR reiterate the findings of PROVEA, one of Venezuela's leading human rights organizations. In its report covering 2017 (published in June 2018), PROVEA asserts that 2017 was the worst year on record for human rights in Venezuela since the report was first published in 1989. In addition to violating political and civil rights, PROVEA denounces the Maduro government's failure to address the country's humanitarian crisis, citing its "official indolence" as causing increasing deaths and massive emigration.25

Despite Opposition, Constituent Assembly Elected

. Clashes between security forces (backed by armed civilian militias) and protesters left more than 130 dead and hundreds injured. In May 2017, President Maduro announced that he would convene a constituent assembly to revise the constitution and scheduled July 30 elections to select delegates to that assembly. The Supreme Court ruled that Maduro could convoke the assembly without first holding a popular referendum (as the constitution required). The opposition boycotted, arguing that the elections were unconstitutional; a position shared by then-Attorney General Luisa Ortega and international observers (including the United States, Canada, the EU, and many Latin American countries). In an unofficial plebiscite convened on July 16 by the MUD, 98% of some 7.6 million Venezuelans cast votes rejecting the creation of a constituent assembly; the government ignored that vote.

Despite an opposition boycott and protests, the government orchestrated the July 30, 2017, election of a 545-member National Constituent Assembly (ANC) to draft a new constitution. Venezuela's CNE reported that almost 8.1 million people voted, but a company involved in setting up the voting system alleged that the tally was inflated by at least 1 million votes.26 Credible reports also allege that the government coerced government workers to vote.2715

Many observers viewviewed the establishment of the ANC as an attempt by the ruling PSUV to ensure its continued control of the government even though many countries have refused to recognize its legitimacy. The ANC dismissed Attorney General Ortega, who had been strongly critical of the government;, voted to approve its own mandate for two years; and passed a measure declaring, and declared itself superior to other branches of government. Ortega fled Venezuela in August 2017 and is speakinghas spoken out against the abuses of the Maduro government.2816 The ANC also approved a decree allowing it to pass legislation, essentially replacing the roleunconstitutionally assuming the powers of the National Assembly.

Maduro's Efforts to Consolidate Power Before the May 2018 Elections

From mid-2017 to May 2018, President Maduro strengthened his control over the PSUV and gained the upper hand over the MUD despite international condemnation of his actions.29 On17 In October 152017, the PSUV won 18 of 23 gubernatorial elections; although. Although fraud likely took place given the significant discrepancies between preelection opinion polls and the election results, the opposition could not prove that fraud occurred on a large scale.30was widespread.18 There is evidence that the PSUV linked receipt of future government food assistance to votes for its candidates by placing food assistance card registration centers next to polling stations, a practice that has been repeatedalso used in subsequent elections.3119 The MUD coalition initially rejected the election results, but four victorious MUD governors subsequently took their oaths of office in front of the ANC (rather than the National Assembly), a decision that fractured the coalition.

With the opposition in disarray, President Maduro and the ANC moved to consolidate power and blamed U.S. sanctions, which were opposed by some 60% of Venezuelans surveyed by Datanalisis (a Venezuelan polling firm) in December 2017, for the country's economic problems. Maduro fired and arrested the head of PdVSA and the oil minister, who were close to Rafael Ramirez (former head of PdVSA and a potential rival to Maduro within the PSUV), for the country's economic problems. Maduro fired and arrested the head of PdVSA and the oil minister for corruption. for corruption.32 He appointed a general with no experience in the energy sector as oil minister and head of the company, further consolidating military control over the economy. Maduro then ousted Ramirez from his position as Venezuela's U.N. ambassador.33 The ANC approved a "hate crimes" The ANC approved a law to further restrict freedom of expression and assembly.34

Although most opposition parties did not participate in municipal elections held onin December 10, 2017, a few, including A New Time (UNT), led by Manuel Rosales, and Progressive Advance (AP), led by Henri Falcón, former governor of the state of Lara, fielded candidates. The PSUV won more than 300 of 335 mayoralties and the governorship of Zulia. The Maduro government then. The CNE required parties that did not participate in the municipalthose elections to re-register in order to run in the 2018 presidential contest, a requirement that many of them subsequently rejected.

May 2018 Elections

The Venezuelan constitution establishedMay 2018 Elections and Aftermath35

The Venezuelan constitution does not establish strict electoral timetables, but it does establish that the country's presidential elections were to be held by December 2018. Although many prominent opposition politicians had been imprisoned (Leopoldo López, under house arrest), barred from seeking office (Henrique Capriles), or in exile (Antonio Ledezma)3620) by late 2017, some MUD leaders still sought to unseat Maduro through elections. Those leaders negotiated with the PSUV to try to obtain guarantees, such as a reconstituted CNE and international observers, to improve conditions for the 2018 elections. The CNE ignored those negotiations and thehelp ensure the elections would be as free and fair as possible. In January 2018, the ANC ignored those negotiations and called for elections to be moved up from December to May 2018, violating a constitutional requirement that elections be called with at least six months anticipation.21 The MUD declared an election boycott, but Henri Falcón (AP) broke with the coalition to run. During the campaign, Falcón promisedFalcón, former governor of Lara, pledged to accept humanitarian aidassistance, dollarize the economy, and foster national reconciliation.

Venezuela's presidential election proved to be minimally competitive and took place within a climate of state repression. President Maduro and the PSUV's control over the CNE, courts, and constituent assembly weakened Falcón's ability to campaign. State media promoted government propaganda. There were no internationally accredited election monitors. The government coerced its workers to vote and placed food assistance card distribution centers next to polling stations. In addition, the elections took place within a climate of state repression. Security forces and allied armed civilian militias have violently repressed protesters and imprisoned government critics.

The CNE reports

The CNE reported that Maduro received 67.7% of the votes, followed by Falcón (21%) and Javier Bertucci, a little-known evangelical minister (10.8%).3722 Voter turnout was much lower in 2018 (46%) than in 2013 (80%), perhaps due to the MUD's boycott. IndependentAfter independent monitors reported even lower figures,widespread fraud, and progovernment stands offering "prizes" to voters near polling stations.38 Falcón and Bertucci refused to accept the results and called for new elections.39 Nevertheless, the ANC inaugurated President Maduro to a second term on May 26, 2018, some eight months ahead of schedule.

Since the , Falcón and Bertucci called for new elections to be held.23

Lead-Up to Maduro's January 2019 Inauguration and Aftermath

Since the May 2018 election, President Maduro has faced mounting economic problems (discussed in "Economic Crisis," below) as oil production has plummeted, as well as increasing international isolation (see "Foreign Relations and Responses to the Maduro Government," below). He has reshuffled his Cabinet, purportedly in an attempt to boost the economy. Maduro selected Delcy Rodriguez, a former foreign minister and head of the ANC, as his vice president. He then announced that Vice President El Aissami will serve as the economic vice president and head of a new "national industry and production ministry."40 Rodriguez has been replaced as head of the ANC by Diosdado Cabello.

In addition to changes in his Cabinet, Maduro released U.S. hostage Joshua Holt and more than 120 prisoners. Although some of those prisoners—including former Mayor Daniel Ceballos and three opposition legislators, Gilber Caro, Renzo Prieto, and Wilmer Azuaje—have been identified by the opposition and Foro Penal as political prisoners, others were likely common criminals.41 Foro Penal estimates that some 280 political prisoners remained as of mid-June 2018.42 At the same time, the government has continued to harass opposition leaders such as Maria Corina Machado.43 As a result, few observers predict that Maduro's gestures will convince the opposition to dialogue with him.

Foreign Relations and Responses to the Maduro Government

The Maduro government has maintained Venezuela's foreign policy alliance with Cuba and other leftist governments from the Chávez era, but the country's ailing economy has diminished its formerly activist foreign policy, which depended on its ability to provide subsidized oil. Unlike during the Chávez era, an increasing number of countries have criticized authoritarian actions taken by the Maduro government and implemented targeted sanctions against its officials.44

Sanctions by Canada and the European Union, Criticism by U.N. Officials

Venezuela's foreign relations have become more tenuous as additional countries have sanctioned its officials and called upon the U.N. to investigate the country's human rights record. In September 2017, Canada implemented targeted sanctions against 40 Venezuelan officials deemed to be corrupt; it added another 14 individuals, including President Maduro's wife, following the May elections.45 In November 2017, the EU established a legal framework for targeted sanctions and adopted an arms embargo against Venezuela to include related material that could be used for internal repression. These actions paved the way for targeted EU sanctions on seven Venezuelan officials in January 2018.46 On June 25, 2018, the Council of the EU sanctioned 11 additional individuals for human rights violations and undermining democracy and called for new presidential elections to be held.47 In September 2017, several countries urged the U.N. Human Rights Council to support the High Commissioner's call for an international investigation into the abuses described in the U.N.'s August report on Venezuela.48

Growing Concerns in Latin America

Ties between Venezuela and a majority of South American countries have frayed with the rise of conservative governments in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Peru and with Maduro's increasingly authoritarian actions. In December 2016, the South American Common Market (Mercosur) trade bloc suspended Venezuela over concerns that the Maduro government had violated the requirement that Mercosur's members have "fully functioning democratic institutions."49 Six UNASUR members—Uruguay, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Paraguay—issued a joint statement opposing the Venezuelan Supreme Court's attempted power grab in March 2017.

Concerned about potential spillover effects from turmoil in Venezuela, Colombia has supported OAS actions, provided humanitarian assistance to Venezuelan economic migrants and asylum seekers, and closely monitored the situation on the Venezuelan-Colombian border. In February 2018, both Colombia and Brazil moved additional security forces to their borders with Venezuela.50 Many analysts predict that Colombia's president-elect, conservative Ivan Duque, a protégé of former president Álvaro Uribe, may adopt a more antagonistic position toward the Maduro government than Juan Manuel Santos has had. Tensions remain high along the border with Guyana after the U.N. proved unable to resolve a long-standing border-territory dispute between the countries and referred the case to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in January 2018. Guyana is asking the ICJ to rule even though Venezuela has opted out of the process.51

Mexico abandoned its traditional noninterventionist stance in 2017 to take a lead in OAS efforts to resolve the crisis in Venezuela. The Mexican government has explored the possibility of replacing Venezuela as a source of oil for Cuba and PetroCaribe countries. It has thus far coordinated its diplomatic efforts in the Caribbean with the United States and Canada.52 Some observers predict that it is unlikely that the frontrunner in Mexico's July 1, 2018, presidential elections, leftist Andrés Manuel López Obrador, would take a strong stance toward Venezuela.53

On August 8, 2017, 12 Western Hemisphere countries signed the Lima Accord, a document rejecting the rupture of democracy and systemic human rights violations in Venezuela, refusing to recognize the ANC, and criticizing the government's refusal to accept humanitarian aid.54 The signatory countries are Mexico; Canada; four Central American countries (Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, and Panama); and six South American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Paraguay, and Peru). Although the Lima Group countries support targeted U.S. economic sanctions, they reject any discussion of military intervention and most are not in favor of restrictions on U.S. petroleum trade with Venezuela.55

On February 13, 2018, Guyana and St. Lucia joined the Lima Group as it issued a statement calling for the Maduro government to negotiate a new electoral calendar that is agreed upon with the opposition and to accept humanitarian aid.56 These nations also backed Peru's decision to disinvite President Maduro to the Summit of the Americas meeting of Western Hemisphere heads of state held on April 13-14, 2018. The Lima Group did not recognize the results of the May 20, 2018, Venezuelan elections.57 Its members were among the 19 countries that voted in favor of an OAS resolution on Venezuela approved on June 5, 2018.58 The resolution said that the electoral process in Venezuela "lacks legitimacy" and authorized countries to take "the measures deemed appropriate," including sanctions, to assist in hastening a return to democracy in Venezuela. (See Appendix B for OAS efforts on Venezuela).

Cuba, PetroCaribe, and the Bolivarian Alliance of the Americas (ALBA)

In 2000, Venezuela signed an agreement with Cuba to provide the island nation with at least 90,000 barrels of oil per day (b/d). In exchange, Cuba has provided extensive services to Venezuela. Estimates of the number of Cuban personnel in Venezuela vary, but a 2014 Brookings study reported that "by most accounts there are 40,000 Cuban professionals in Venezuela," 75% of whom are health care workers.59 At that time, the number of Cuban military and intelligence advisors in Venezuela may have ranged from hundreds to thousands, coordinated by Cuba's military attaché in Venezuela.60 It is unclear whether those professionals have stayed as the situation in Venezuela has deteriorated.

In recent years, Cuba has become increasingly concerned about the future of Venezuelan oil supplies (see "Developments in Venezuela's Energy Sector").61 Cuba's oil imports from Venezuela reportedly declined from 100,000 b/d in 2012 to roughly 55,000 b/d in 2016.62 Although Cuba has imported more oil from Russia and Algeria to make up for dwindling Venezuelan supplies since 2017, the Maduro government remains committed to providing what it can.63 In May 2018, press reports revealed that Venezuela had purchased almost $440 million in foreign oil that it then provided to Cuba, often at a loss.64

Since 2005, Venezuela has provided oil and other energy-related products to 17 other Caribbean Basin nations with preferential financing terms in a program known as PetroCaribe. Most Caribbean nations are members of PetroCaribe, with the exception of Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago, as are several Central American countries.65 Shipments have been declining dramatically in recent years, with an estimated 54% reduction in deliveries from 2015 to 2017.66 According to S&P Global Platts, Venezuela has indefinitely suspended a combined total of 38,000 b/d in shipments to eight PetroCaribe countries: Antigua and Barbuda, Belize, Dominica, El Salvador, Haiti, Nicaragua, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and St. Kitts and Nevis.

Until recently, the Maduro government has continued to count on political support from Cuba, Bolivia, and Nicaragua, which, together with Venezuela, are key members of the Bolivarian Alliance of the Americas (ALBA), a group launched by President Chávez in 2004. Caribbean members of ALBA—Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, St. Kitts and Nevis, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines—had been reluctant to take action that could be viewed as interfering in Venezuela's domestic affairs. Since Lenín Moreno took office in May 2017, the Ecuadorian government (another ALBA member) has been critical of the Maduro government. Most of these governments abstained from the June 5, 2018, OAS vote on Venezuela, with only Bolivia, Dominica, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines voting with Venezuela and against the measure.

China and Russia

As Venezuela's economic situation has deteriorated, maintaining close relations with China and Russia, the country's largest sources of financing and investment, has become a top priority.67 From 2007 through 2016, China provided some $62.2 billion in financing to Venezuela.68 The money typically has been for funding infrastructure and other economic development projects, but has also included some lending for military equipment.69 It is being repaid through oil deliveries. Although the Chinese government has been patient when Venezuela has fallen behind on its oil deliveries, it reportedly stopped providing new loans to Venezuela in fall 2016.70

Some observers have criticized China for its continued support to the Venezuelan government and questioned whether a new Venezuelan government might refuse to honor the obligations incurred under Maduro.71 China refrained from any negative commentary after Venezuela's Constituent Assembly elections. It maintained that the Venezuelan government and people have the ability to properly handle their internal affairs through dialogue.72 China responded to U.S. sanctions by stating that "the experience of history shows that outside interference or unilateral sanctions will make the situation even more complicated."73 It has expressed confidence that Venezuela can "appropriately handle their affairs, including the debt issue."74 The Chinese government did not congratulate President Maduro on his reelection but maintained that it would not intervene in the country's domestic affairs.75

Russia has remained a strong ally of the Maduro government. It has called for the political crisis in Venezuela to be resolved peacefully, with dialogue, and without outside interference.76 Russia's trade relations with Venezuela currently are not significant, with $336 million in total trade in 2016, with almost all of that, $334 million, consisting of Russian exports to Venezuela.77 However, Venezuela had been a major market for Russian arms sales between 2001 and 2013, with over $11 billion in sales. Press reports in May 2017 asserted that Venezuela had more than 5,000 Russian-made surface-to-air missiles, raising concern by some about the potential for them being stolen or sold to criminal or terrorist groups.78 Russia's recent decision to allow Venezuela to restructure $3.15 billion in debt provided some much-needed financial relief to the Maduro government.79 Russian state oil companies Rosneft and Gazprom have large investments in Venezuela. Both are seeking to expand investments in Venezuela's oil and gas markets80 (see "Energy Sector Concerns" below). Russia congratulated President Maduro on his reelection.81

Iran

There is some debate about the extent and significance of Iran's relations with Venezuela. The personal relationship between Hugo Chávez and Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005-2013) drove the strengthening of bilateral ties over that period. Since Ahmadinejad left office and Chávez passed away in 2013, many analysts contend that Iranian relations with the region have diminished. Current Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, who took office in August 2013, has not prioritized relations with Latin America. Nevertheless, there are two Iranian companies operating in Venezuela that are subject to U.S. sanctions.82

Economic Crisis83

For decades, Venezuela was one of South America's most prosperous countries. Venezuela has the world's largest proven reserves of oil, and its economy is built on oil.84 Oil accounts for more than 90% of Venezuelan exports, and oil sales fund the government budget. Venezuela benefited from the boom in oil prices during the 2000s. President Chávez used the oil windfall to spend heavily on social programs and expand subsidies for food and energy, and government debt more than doubled as a share of GDP between 2000 and 2012.85 Additionally, Chávez used oil to expand influence abroad through PetroCaribe, a program described above that allowed Caribbean countries to purchase oil at below-market prices.

Although substantial government outlays on social programs helped Chávez curry political favor and reduce poverty, economic mismanagement had long-term consequences. Chávez moved the economy in a less market-oriented direction, with widespread expropriations and nationalizations, as well as currency and price controls. These policies discouraged foreign investment and created market distortions. Government spending was not directed toward investment to increase economic productivity or diversify the economy from its reliance on oil. Corruption proliferated.

When Nicolás Maduro was elected president in April 2013, he inherited economic policies reliant on proceeds from oil exports. When oil prices crashed by nearly 50% in 2014, the Maduro government was ill-equipped to soften the blow. Venezuela's economy contracted by nearly 35% between 2012 and 2017.86 The fall in oil prices strained public finances, and instead of adjusting fiscal policies through tax increases and spending cuts, the Maduro government tried to address its growing budget deficit by printing money, which led to hyperinflation. The government has tried to curb inflation through price controls, although these controls have been largely ineffective in restricting prices, as supplies have dried up and transactions have moved to the black market.87

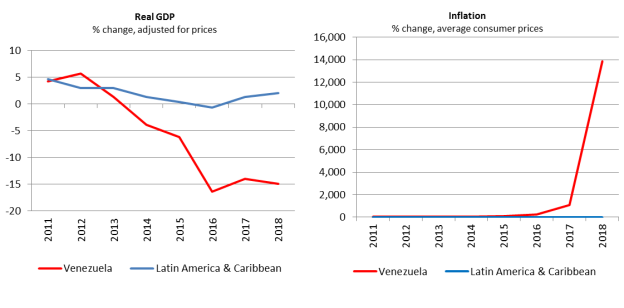

Thus far in 2018, economic conditions have deteriorated rapidly, driven by a collapse in oil production and consumer spending, as well as by a continuing rapid expansion of the money supply.88 In April 2018, the IMF forecast that Venezuela's economy will contract by another 15% in 2018 and that inflation will exceed 13,000% (Figure 2).89 During the presidential campaign, economic issues loomed large. Maduro vowed to "make big economic changes" but lacked concrete proposals to address the myriad of problems that emerged in his first term: hyperinflation, food shortages, the return of once-controlled diseases, and mass emigration.90 The main challenger, Falcón, proposed to dollarize the economy, reverse botched nationalizations, and open Venezuela to immediate emergency foreign aid.91

|

|

|

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, April 2018. Note: Includes estimated and forecasted data. |

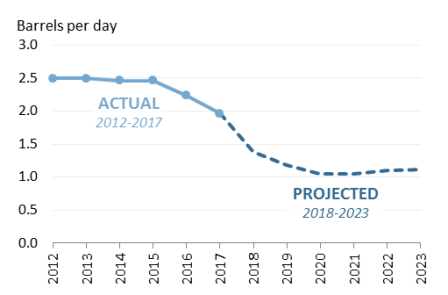

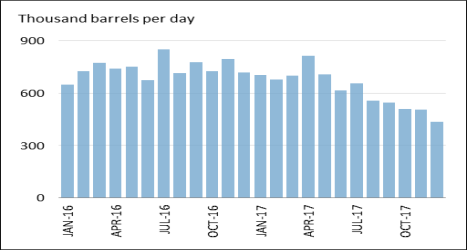

Developments in Venezuela's Energy Sector92

Although Venezuela had 301 billion barrels of proven oil reserves in 2017,93 crude oil production in the country declined from an average of roughly 2.9 million barrels per day (b/d) in 2000 to an average of 1.9 million b/d in 2017,94 according to OPEC.95 Monthly oil production continued to decline in 2018, with production levels averaging 1.4 million b/d in May 2018.96 In March 2018, the International Energy Agency projected that Venezuela's crude oil production would continue to drop to just over 1 million b/d (See Figure 3 below).97

|

|

|

Source: International Energy Agency, Oil 2018, March 2018. |

PdVSA's performance has been hurt by a number of factors. Since August 2017, the Maduro government arrested many executives for alleged corruption, which dissidents within the company assert has been a false pretense for replacing technocrats with military officers.98 Workers at all levels reportedly are abandoning the company by the thousands.99 Production has been challenged by aging infrastructure, bottlenecks created by PdVSA's inability to pay service companies and producers, and shortages of inputs (such as light crudes for blending) used to process its heavy crude oil.100 Massive debt (estimated at some $25 billion),101 combined with U.S. sanctions limiting the willingness of banks to issue credit to PdVSA and the fact that most of its production does not generate revenue, have added to the company's woes (see "Debt and Default" below).102 Since Conoco has sought to seize PdVSA storage and loading facilities in the Caribbean over nonpayment of past debts, tankers with crude oil have begun backing up and the company has said that it will not be able to satisfy all of its June deliveries.103

Corruption remains a major drain on the company's revenues and an impediment to performance. In 2016, a report by the Venezuelan National Assembly estimated that some $11 billion disappeared at PdVSA from 2004 to 2014.104 In February 2018, U.S. prosecutors unsealed an indictment against five former executives in Venezuela's energy ministry and PdVSA accused of offering priority contracts in exchange for millions of dollars in bribes.105 Corruption and dysfunction reportedly have continued since a military general with no experience in the energy sector took control of the company in November 2017, with looting of essential equipment by criminals and former employees now commonplace.106

Declining production by PdVSA-controlled assets has, until recently, contrasted to the performance of joint ventures that PdVSA has with Chevron, CNPC, Gazprom, Repsol, and others. From 2010 to 2015, production declined by 27.5% in fields solely operated by PdVSA, whereas production in fields operated by joint ventures increased by 42.3%.107 The future of these ventures is uncertain, however, as Maduro's government arrested executives from Chevron in April 2018 after they reportedly refused to sign an agreement under unfair terms. Although they were released in June, Chevron and other companies are scaling back their operations.108

Debt and Default

A significant challenge facing Venezuela is the government's sizeable debt. It is estimated that the Venezuelan government owes about $64 billion to bondholders, $20 billion to China and Russia, $5 billion to multilateral lenders (such as the Inter-American Development Bank), and tens of billions to importers and service companies in the oil industry.109 As fiscal conditions tightened, the government initially took a number of steps to continue repaying its debt, even though debt repayments diverted needed resources from the Venezuelan people. To make debt payments, the Maduro government cut imports, leading to shortages of food and medicine, and secured loans from China and Russia in exchange for future oil exports ("oil-for-loan" deals). The government was reluctant to default, fearing legal challenges from creditors and the seizure of Venezuela's overseas assets, including PdVSA subsidiary CITGO, oil shipments, and cash payments for oil exports. In August 2017, the government's precarious fiscal situation was exacerbated by new sanctions imposed by the Trump Administration (discussed in greater detail below), which restricted Venezuela's ability to access U.S. financial markets.

After months of speculation about if and when Venezuela would default, on November 2, 2017, Maduro announced in a televised address that the country would seek to restructure and refinance its debt. The announcement signaled a significant shift in policy, but came with few details about how the restructuring would proceed. The government and PdVSA in November 2017 subsequently missed key bond payments, leading credit-rating agencies to issue a slew of default notices. In April 2018, news reports revealed that the government had actually largely stopped paying bondholders in September 2017, but that bondholders, hoping for repayment, had not yet initiated legal actions against the government.110

Any comprehensive restructuring of Venezuelan debt is expected to be a long and complex process, and there has been little headway to date. U.S. sanctions prevent U.S. investors from participating in any debt restructuring, and Maduro has blamed U.S. sanctions for the delay in restructuring with private bondholders.111 Bondholders are in the early stages of organizing for possible future restructuring negotiations, but recent events may cause them to accelerate legal efforts for compensation.112 In May 2018, a court on the Dutch island of Curacao authorized the local subsidiary of U.S. oil company ConocoPhillips to seize PdVSA assets on the island in compensation for a decade-old expropriation dispute. Additionally in May 2018, the first lawsuit against PdVSA for nonpayment was filed in New York (where many of Venezuela's bonds were issued).113 Given that Venezuela's overseas assets are insufficient to fully compensate all foreign investors, investors may fear being last in line among those seeking compensation.114 In terms of debt owed to other governments, Russia agreed to restructure Venezuela's debt in November 2017, but China appears to be taking a stronger position on repayment.115

Meanwhile, the government continues to grapple with significant fiscal problems, with foreign reserves at their lowest level in two decades and remittances into the country on the rise.116 In February 2018, the cash-strapped government launched a new digital currency, the "petro," which is backed by oil and other commodities and runs on blockchain technology.117 The primary motivation for the petro is to provide a fresh source of funds to the government, particularly in light of U.S. sanctions that restrict its ability to issue new debt. The government reported that it raised $735 million in the first day of the petro presale.118 Venezuelans are prohibited from buying petros with bolívars, but the government claimed to draw investors from Turkey, Qatar, and Europe.119 Many analysts are skeptical about the viability of the petro, which sold at a deep discount from the face value. In March 2018, the Trump Administration issued Executive Order 13827, which bans U.S. individuals and entities from purchasing or transacting in any digital currency issued by the Venezuelan government.

As the government continues to run down reserves and the humanitarian situation worsens, the economic outlook for Venezuela is dire. The country faces a complex set of economic challenges embedded in a volatile political context: collapsed output, hyperinflation, and unsustainable budget deficits and debt. The government's policy responses to the crisis—including price and import controls, vague restructuring plans, and deficit spending financed by expanding the money supply (printing money)—have been widely criticized as inadequate and as exacerbating the economic situation. Normally, countries facing such a serious economic crisis would turn to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for financial and policy assistance. However, Venezuela has not allowed the IMF to conduct routine surveillance of its economy since 2004, and the IMF has found the government in violation of its commitments as an IMF member. Although the crisis has been building for a number of years, it is not clear whether there is a clear or quick resolution on the horizon, particularly given the concurrent political crisis.

Humanitarian Situation120

Overview

Growing numbers of people continue to leave Venezuela for urgent reasons, including insecurity and violence; lack of food, medicine, or access to essential social services; and loss of income. According to the 2017 national survey on living conditions, the percentage of Venezuelans living in poverty increased from 48.4% in 2014 to 87% in 2017.121 Poverty has been exacerbated by shortages in basic consumer goods, as well as by bottlenecks and corruption in the military-run food importation and distribution system.122 Basic food items that do exist are largely out of reach for the majority of the population due to rampant inflation. Between 2014 and 2016, Venezuela recorded the greatest increase in malnourishment in Latin America and the Caribbean, a region in which only eight countries recorded increases in hunger.123 According to Caritas Venezuela (an organization affiliated with the Catholic Church), 15% of children surveyed in August 2017 suffered from moderate to severe malnutrition and 30% showed stunted growth.124

Venezuela's health system has been affected severely by budget cuts, with shortages of medicines and basic supplies, as well as doctors, nurses, and lab technicians. Some hospitals face critical shortages of antibiotics, intravenous solutions, and even food, and 50% of operating rooms in public hospitals are not in use.125 According to Médicos por la Salud, a Venezuelan nongovernmental health organization, only 38% of drugs listed as essential by the WHO are available in the country, and only 30% of drugs for basic infectious diseases are available in public hospitals.126 According to a June 2018 WHO/PAHO report, some 22,000 doctors (33% of the total doctors that were present in 2014) and at least 3,000 nurses have emigrated.127

In February 2017, Venezuela captured international attention following the unexpected publication of data from the country's Ministry of Health (the country had not been regularly releasing such data since 2015). The report revealed significant spikes in infant and maternal mortality rates.128 PAHO's recent report documents the spread of previously eradicated infectious diseases like diphtheria (detected in July 2016) and measles (detected in July 2017).129 Malaria, once under control, is also spreading rapidly, with 406,289 cases recorded in 2017 (a 198% increase over 2015).130 People are also reportedly dying at a faster rate from HIV/AIDS in Venezuela than in many African countries due to the collapse of the country's once well-regarded HIV treatment program and the scarcity of drugs needed to treat the disease.131 HIV advocates have pushed for the Global Fund, a public-private entity that focuses on HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria, to do more to address the situation in Venezuela.132 Observers are concerned that the widespread lack of access to reliable contraception may hasten the spread of sexually transmitted diseases, unwanted pregnancies, and dangerous clandestine abortions.133

During the Vatican-mediated talks in November 2016, the Maduro government reportedly agreed to improve the processes for importing food and medicines and promote monitoring of distribution chains. Discussions reportedly also broached the idea of establishing a channel for allowing humanitarian aid to reach Venezuela, possibly through Caritas Venezuela. The WHO is reportedly helping the government purchase and deliver millions of vaccines against measles, mumps, and rubella.134 Nevertheless, a group of doctors and health associations protested outside the WHO's office in Caracas in September 2017 to urge the entity to provide more assistance and exert more pressure on the government to address the health crisis.135 In December 2017, President Maduro rejected the need for international assistance, and government-MUD dialogue efforts in the Dominican Republic failed to agree upon how to open a channel to get food and medical assistance into the country.

According to the Colombian government, as of early 2018, roughly 1.6 million Venezuelans had registered for a Border Mobility Card (no longer being issued), which allows a person to enter Colombia temporarily to access basic goods and services.136 According to the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the Colombian government is reporting increasing numbers of arrivals, both those seeking temporary assistance and those seeking permanent relocation, with less means and more humanitarian needs than those who arrived in 2017.137 Tensions have been reported in some Colombian border communities that are straining to absorb new arrivals.138 As the socioeconomic and political conditions in Venezuela continue to deteriorate, the humanitarian situation inside Venezuela is getting worse. The root causes in Venezuela are leading many people to make the difficult decision to leave, which is creating challenges for the countries receiving them.

Population Displacement and Humanitarian Needs in the Border Regions

Thousands of Venezuelans in areas bordering Brazil and Colombia who in the past entered those countries on a temporary basis to obtain food and medicine have chosen to remain outside Venezuela for the time being. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the percentage increase in the number of Venezuelans arriving in Chile, Colombia, and Peru from 2015 to 2017 exceeded 1,000%.139 As the situation in Venezuela has deteriorated, the pace of the arrivals has quickened, with some neighboring countries straining to absorb them. Secondary impacts, such as increased public health issues and the spread of disease, are also of increasing concern in the region.140

Based on conservative government figures, more than 1.5-1.6 million Venezuelan nationals have left the country since 2014. As of May 2018, UNHCR reported that there were an estimated 600,000 Venezuelans living in Colombia, 93,000 in Ecuador, 100,000 in Peru, 60,000 in the Southern Caribbean (particularly in Trinidad and Tobago), and 40,000 in Brazil.141 Although not all may be refugees, it is evident that a significant number are in need of international protection. An estimated 60% of Venezuelans remain in an irregular situation, without documentation, including those not able to apply for asylum or another legal status because of bureaucratic obstacles, long waiting periods, or high application fees. Host countries (including Colombia, Brazil, Ecuador, Peru, Panama and the southern Caribbean) have become increasingly strained, and more than half of all Venezuelans in these countries have no regular status and are more vulnerable to protection risks.

Some of those who have left Venezuela have sought asylum in countries in the region and beyond. Since 2014, UNHCR reports that more than 170,000 Venezuelans have filed claims globally. The major destination countries for recent Venezuelan asylum seekers have included the United States (58,800), Brazil (22,300), Peru (20,850), and Spain (12,300).142 An estimated 500,000 have accessed alternative legal forms of stay in Latin America.

Humanitarian organizations and governments are responding to the needs of displaced Venezuelans in the region. Protection and assistance needs are significant for arrivals and host communities. Services provided vary by country but include support for reception centers and options for shelter; emergency relief items, such as emergency food assistance, safe drinking water, and hygiene supplies; legal assistance with asylum applications and other matters; protection from violence and exploitation; and the creation of temporary work programs and education opportunities.

Countries in the region are under pressure to examine migration and asylum policies and to consider strategies for addressing the legal status of Venezuelans who have fled their country. This is a significant displacement crisis for the Western Hemisphere, which has in place some of the highest international and regional protection standards for displaced and vulnerable persons. The 1984 Cartagena Declaration on Refugees, along with more recent consultative processes and declarations, has an expanded definition of refugee, which goes beyond the 1951 U.N. Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol and incorporates a new framework for regional action in the protection of vulnerable groups and individuals. It provides a broader scope for addressing the risks to refugees, including indirect effects such as poverty, economic decline, inflation, violence, disease, food insecurity, malnourishment, and displacement.

International Appeals for Assistance

U.N. agencies and other international organizations have launched appeals for additional international assistance, and the U.S. government is providing humanitarian assistance and helping to coordinate regional response efforts (see "U.S. Humanitarian and Related Assistance," below).

In mid-March 2018, UNHCR launched a revised appeal, which requests a total of $46.1 million for funding to support vulnerable Venezuelans throughout the Latin America and Caribbean region. As of June 13, 2018, donors had funded 44% of the appeal. On April 10, 2018, IOM launched a regional action plan requesting $32.3 million in funding to provide assistance to Venezuelans in the region. IOM plans to expand its Displacement Tracking Matrix to all countries receiving Venezuelans and to assist governments and relief organizations responding to arrivals.143 Other appeals are being drafted to respond to the increasing needs in the region. There are also appeals launched by organizations outside the U.N. system.

U.S. Policy