Venezuela: Issues for Congress, 2013-2016

Although historically the United States had close relations with Venezuela, a major oil supplier, friction in bilateral relations increased under the leftist, populist government of President Hugo Chávez (1999-2013), who died in 2013 after battling cancer. After Chávez’s death, Venezuela held presidential elections in which acting President Nicolás Maduro narrowly defeated Henrique Capriles of the opposition Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD), with the opposition alleging significant irregularities. In 2014, the Maduro government violently suppressed protests and imprisoned a major opposition figure, Leopoldo López, along with others.

In December 2015, the MUD initially won a two-thirds supermajority in National Assembly elections, a major defeat for the ruling United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). The Maduro government subsequently thwarted the legislature’s power by preventing three MUD representatives from taking office (denying the opposition a supermajority) and using the Supreme Court to block bills approved by the legislature.

For much of 2016, opposition efforts were focused on recalling President Maduro through a national referendum, but the government slowed down the referendum process and suspended it indefinitely in October. After an appeal by Pope Francis, the government and most of the opposition (with the exception of Leopoldo López’s Popular Will party) agreed to talks mediated by the Vatican along with the former presidents of the Dominican Republic, Spain, and Panama and the head of the Union of South American Nations. The two sides issued a declaration in November expressing firm commitment to a peaceful, respectful, and constructive coexistence. They also issued a statement that included an agreement to improve the supply of food and medicine and to resolve the situation of the three National Assembly representatives. Some opposition activists strongly criticized the dialogue as a way for the government to avoid taking any real actions, such as releasing all political prisoners. The next round of talks was scheduled for December but was suspended until January 2017, and many observers are skeptical that the dialogue will resume.

The rapid decline in the price of oil since 2014 hit Venezuela hard, with a contracting economy (projected -10% in 2016), high inflation (projected 720% at the end of 2016), declining international reserves, and increasing poverty—all exacerbated by the government’s economic mismanagement. The situation has increased poverty, with severe shortages of food and medicines and high crime rates.

U.S. Policy

U.S. policymakers and Members of Congress have had concerns for more than a decade about the deterioration of human rights and democratic conditions in Venezuela and the government’s lack of cooperation on antidrug and counterterrorism efforts. After a 2014 government-opposition dialogue failed, the Administration imposed visa restrictions and asset-blocking sanctions on Venezuelan officials involved in human rights abuses.

The Obama Administration continued to speak out about the democratic setback and poor human rights situation, called repeatedly for the release of political prisoners, expressed deep concern about the humanitarian situation, and strongly supported dialogue. The Administration also supported the efforts Organization of American States Secretary General Luis Almagro to focus attention on Venezuela’s democratic setback.

Congressional Action

Congress enacted legislation in 2014—the Venezuela Defense of Human Rights and Civil Society Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-278)—to impose targeted sanctions on those responsible for certain human rights abuses (with a termination date of December 2016 for the requirement to impose sanctions). In July 2016, Congress enacted legislation (P.L. 114-194) extending the termination date of the requirement to impose sanctions set forth in P.L. 113-278 through 2019.

In September 2016, the House approved H.Res. 851 (Wasserman Schulz), which expressed profound concern about the humanitarian situation, urged the release of political prisoners, and called for the Venezuelan government to hold the recall referendum this year. In the Senate, a similar but not identical resolution, S.Res. 537 (Cardin), was reported, amended, by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in December 2016.

For more than a decade, Congress has appropriated funding for democracy and human rights programs in Venezuela. An estimated $6.5 million is being provided in FY2016, and the Administration requested $5.5 million for FY2017. The House version of the FY2017 foreign operations appropriations bill (H.R. 5912, H.Rept. 114-693) would have provided $8 million, whereas the Senate version (S. 3117, S.Rept. 114-290) would have fully funded the request. The 114th Congress did not complete action on FY2017 appropriations, although it approved a continuing resolution in December 2016 (P.L. 114-254) appropriating foreign aid funding through April 28, 2017, at the FY2016 level, minus an across-the board reduction of almost 0.2%.

Note: This report provides background on political and economic developments in Venezuela, U.S. policy, and U.S. legislative action and initiatives from 2013 to 2016 covering the 113th and 114th Congresses. It will not be updated. For additional information, see CRS In Focus IF10230, Venezuela: Political Situation and U.S. Policy Overview.

Venezuela: Issues for Congress, 2013-2016

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction and Recent Developments

- Political Background

- Background: Chávez's Rule, 1999-2013

- The Post-Chávez Era, 2013-2014

- April 2013 Presidential Election

- December 2013 Municipal Elections

- Protests and Failed Dialogue in 2014

- Political and Economic Environment in 2015-2016

- December 2015 Legislative Elections and Aftermath

- Efforts to Recall President Maduro

- OAS Efforts on Venezuela

- Vatican Prompts Renewed Efforts at Dialogue

- Economic and Social Conditions

- Venezuela's Foreign Policy Orientation

- U.S. Relations and Policy

- Obama Administration Policy

- Responding to Venezuela's Repression of Dissent in 2014 and 2015

- Pressing for Respect for Human Rights, Democracy, and Dialogue in 2016

- Democracy and Human Rights Concerns

- Energy Issues

- Counternarcotics Issues

- Terrorism Issues

- Outlook

Figures

Summary

Although historically the United States had close relations with Venezuela, a major oil supplier, friction in bilateral relations increased under the leftist, populist government of President Hugo Chávez (1999-2013), who died in 2013 after battling cancer. After Chávez's death, Venezuela held presidential elections in which acting President Nicolás Maduro narrowly defeated Henrique Capriles of the opposition Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD), with the opposition alleging significant irregularities. In 2014, the Maduro government violently suppressed protests and imprisoned a major opposition figure, Leopoldo López, along with others.

In December 2015, the MUD initially won a two-thirds supermajority in National Assembly elections, a major defeat for the ruling United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). The Maduro government subsequently thwarted the legislature's power by preventing three MUD representatives from taking office (denying the opposition a supermajority) and using the Supreme Court to block bills approved by the legislature.

For much of 2016, opposition efforts were focused on recalling President Maduro through a national referendum, but the government slowed down the referendum process and suspended it indefinitely in October. After an appeal by Pope Francis, the government and most of the opposition (with the exception of Leopoldo López's Popular Will party) agreed to talks mediated by the Vatican along with the former presidents of the Dominican Republic, Spain, and Panama and the head of the Union of South American Nations. The two sides issued a declaration in November expressing firm commitment to a peaceful, respectful, and constructive coexistence. They also issued a statement that included an agreement to improve the supply of food and medicine and to resolve the situation of the three National Assembly representatives. Some opposition activists strongly criticized the dialogue as a way for the government to avoid taking any real actions, such as releasing all political prisoners. The next round of talks was scheduled for December but was suspended until January 2017, and many observers are skeptical that the dialogue will resume.

The rapid decline in the price of oil since 2014 hit Venezuela hard, with a contracting economy (projected -10% in 2016), high inflation (projected 720% at the end of 2016), declining international reserves, and increasing poverty—all exacerbated by the government's economic mismanagement. The situation has increased poverty, with severe shortages of food and medicines and high crime rates.

U.S. Policy

U.S. policymakers and Members of Congress have had concerns for more than a decade about the deterioration of human rights and democratic conditions in Venezuela and the government's lack of cooperation on antidrug and counterterrorism efforts. After a 2014 government-opposition dialogue failed, the Administration imposed visa restrictions and asset-blocking sanctions on Venezuelan officials involved in human rights abuses.

The Obama Administration continued to speak out about the democratic setback and poor human rights situation, called repeatedly for the release of political prisoners, expressed deep concern about the humanitarian situation, and strongly supported dialogue. The Administration also supported the efforts Organization of American States Secretary General Luis Almagro to focus attention on Venezuela's democratic setback.

Congressional Action

Congress enacted legislation in 2014—the Venezuela Defense of Human Rights and Civil Society Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-278)—to impose targeted sanctions on those responsible for certain human rights abuses (with a termination date of December 2016 for the requirement to impose sanctions). In July 2016, Congress enacted legislation (P.L. 114-194) extending the termination date of the requirement to impose sanctions set forth in P.L. 113-278 through 2019.

In September 2016, the House approved H.Res. 851 (Wasserman Schulz), which expressed profound concern about the humanitarian situation, urged the release of political prisoners, and called for the Venezuelan government to hold the recall referendum this year. In the Senate, a similar but not identical resolution, S.Res. 537 (Cardin), was reported, amended, by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in December 2016.

For more than a decade, Congress has appropriated funding for democracy and human rights programs in Venezuela. An estimated $6.5 million is being provided in FY2016, and the Administration requested $5.5 million for FY2017. The House version of the FY2017 foreign operations appropriations bill (H.R. 5912, H.Rept. 114-693) would have provided $8 million, whereas the Senate version (S. 3117, S.Rept. 114-290) would have fully funded the request. The 114th Congress did not complete action on FY2017 appropriations, although it approved a continuing resolution in December 2016 (P.L. 114-254) appropriating foreign aid funding through April 28, 2017, at the FY2016 level, minus an across-the board reduction of almost 0.2%.

Note: This report provides background on political and economic developments in Venezuela, U.S. policy, and U.S. legislative action and initiatives from 2013 to 2016 covering the 113th and 114th Congresses. It will not be updated. For additional information, see CRS In Focus IF10230, Venezuela: Political Situation and U.S. Policy Overview.

Introduction and Recent Developments

This report, divided into three main sections, examines the political and economic situation in Venezuela and U.S.-Venezuelan relations. The first section surveys the political transformation of Venezuela under the populist rule of President Hugo Chávez (1999-2013) and the first two years of the government of President Nicolás Maduro, including the government's severe crackdown on opposition protests in 2014. The second section analyzes Venezuela's political and economic environment in 2015 and 2016, including the opposition's December 2015 legislative victory and the Maduro government's attempts to thwart the powers of the legislature; efforts to remove President Maduro through a recall referendum; deteriorating economic and social conditions in the country; and the government's foreign policy orientation. The third section examines U.S. relations with Venezuela, including the imposition of sanctions on Venezuelan officials, and selected issues in U.S. relations—democracy and human rights, energy, counternarcotics, and terrorism concerns. Appendix A provides information on legislative initiatives in the 113th and 114th Congresses, and Appendix B provides links to selected U.S. government reports on Venezuela.

Significant recent developments include the following:

- On January 4, 2017, President Maduro appointed former Interior Minister and Governor of Aragua state Tareck El Aissami as vice president, replacing Aristóbulo Istúriz, who served in the position for one year. The action was significant since El Aissami would serve out the remainder of President Maduro's term if the President were recalled or stepped down from office.

- On December 7, 2016, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee reported S.Res. 537 (Cardin), amended, expressing profound concern about the ongoing political, economic, social, and humanitarian crisis in Venezuela; urging the release of political prisoners; and calling for respect of constitutional and democratic processes, including free and fair elections.

- On November 18, 2016, a U.S. federal court in New York convicted two nephews of Venezuelan First Lady Cilia Flores for conspiring to transport cocaine into the United States. (See "Counternarcotics Issues," below.)

- On November 16, 2016, the Organization of American States (OAS) Permanent Council adopted a declaration supporting the national dialogue in Venezuela, encouraging the government and the 10-party opposition coalition known as the Democratic Unity Roundtable (Mesa de la Unidad Democrática, or MUD) "to achieve concrete results within a reasonable timeframe," and asserting the need for the constitutional authorities and all political and social actors to act with prudence and avoid any action of violence or threats to the ongoing process." (See "OAS Efforts on Venezuela," below.)

- On November 12, 2016, the Venezuelan government and opposition completed a second round of talks and issued a declaration expressing firm commitment to a peaceful, respectful, and constructive coexistence. They also issued a statement that included agreement to improve the supply of food and medicine, to resolve the situation of three National Assembly representatives who the Maduro government blocked from taking office, and to work together in naming two National Electoral Council (CNE) members whose terms expire in December. Some opposition activists have strongly criticized the dialogue as a way for the government to avoid taking any real actions, such as releasing all political prisoners. (See "Vatican Prompts Renewed Efforts at Dialogue," below.)

- From October 31, 2016, to November 2, 2016, Under Secretary of State Thomas Shannon traveled to Venezuela to demonstrate support for the Vatican-facilitated dialogue. (See "Pressing for Respect for Human Rights, Democracy, and Dialogue in 2016," below).

- On October 30, 2016, the government and representatives of most of the opposition (with the exception of Leopoldo López's Popular Will party) held talks mediated by the Vatican along with the former presidents of the Dominican Republic, Spain, and Panama and the head of the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR.) (See "Vatican Prompts Renewed Efforts at Dialogue," below.)

- On October 20, 2016, Venezuela's CNE indefinitely suspended the recall referendum process after five state-level courts issued rulings alleging fraud in a signature collection drive held in June. (See "Efforts to Recall President Maduro," below.)

- On September 27, 2016, the House approved H.Res. 851(Wasserman Schultz) expressing profound concern about the humanitarian situation, urging the release of political prisoners, and calling for the Venezuelan government to hold the recall referendum this year. (See "Pressing for Respect for Human Rights, Democracy, and Dialogue in 2016" and Appendix A, below.)

- On September 21, 2016, Venezuela's CNE announced that the signature drive for the recall referendum process would be held over a three-day period from October 26, 2016, to October 28, 2016. The CNE also said that that if a recall referendum were held, it likely would take place in the middle of the first quarter of 2017. (See "Efforts to Recall President Maduro," below.)

- On September 12, 2016, President Obama determined for the 12th consecutive year that Venezuela is not adhering to its international antidrug obligations. (See "Counternarcotics Issues," below.)

- On August 11, 2016, the United States joined 14 other members of the Organization of American States (OAS), in issuing a joint statement urging the Venezuelan government and opposition "to hold as soon as possible a frank and effective dialogue" and calling on Venezuelan authorities to realize the remaining steps of the presidential recall referendum "without delay." Previously, the 15 countries had issued a statement on June 15, 2016, that, among other measures, expressed support for a "timely, national, inclusive, and effective political dialogue" and for "the fair and timely implementation of constitutional mechanisms." (See "OAS Efforts on Venezuela," below.)

- On August 1, 2016, the U.S. Federal Court for the Eastern District of New York unsealed a 2015 indictment against two Venezuelan military officials for cocaine trafficking to the United States. One of those indicted, General Néstor Luis Reverol Torres, had been the former head of Venezuela's National Anti-Narcotics Office. President Maduro responded by appointing General Reverol as Minister of Interior and Justice in charge of the country's police forces. (See "Counternarcotics Issues," below.)

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS). |

Political Background

Background: Chávez's Rule, 1999-20131

For 14 years, Venezuela experienced enormous political and economic changes under the leftist populist rule of President Hugo Chávez. Under Chávez, Venezuela adopted a new constitution and a new unicameral legislature and even a new name for the country, the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, named after the 19th century South American liberator Simon Bolivar, whom Chávez often invoked. Buoyed by windfall profits from increases in the price of oil, the Chávez government expanded the state's role in the economy by asserting majority state control over foreign investments in the oil sector and nationalizing numerous enterprises. The government also funded numerous social programs with oil proceeds that helped reduce poverty. At the same time, democratic institutions deteriorated, threats to freedom of expression increased, and political polarization in the country also grew between Chávez supporters and opponents. Relations with the United States also deteriorated considerably as the Chávez government often resorted to strong anti-American rhetoric.

In his first election as president in December 1998, Chávez received 56% of the vote (16% more than his closest rival), an illustration of Venezuelans' rejection of the country's two traditional parties, Democratic Action (AD) and the Social Christian party (COPEI), which had dominated Venezuelan politics for much of the previous 40 years. Elected to a five-year term, Chávez was the candidate of the Patriotic Pole, a left-leaning coalition of 15 parties, with Chávez's own Fifth Republic Movement (MVR) the main party in the coalition. Most observers attribute Chávez's rise to power to Venezuelans' disillusionment with politicians whom they judge to have squandered the country's oil wealth through poor management and endemic corruption. A central theme of his campaign was constitutional reform; Chávez asserted that the system in place allowed a small elite class to dominate Congress and that revenues from the state-run oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PdVSA), had been wasted.

Although Venezuela had one of the most stable political systems in Latin America from 1958 until 1989, after that period numerous economic and political challenges plagued the country and the power of the two traditional parties began to erode. Former President Carlos Andres Perez, inaugurated to a five-year term in February 1989, initiated an austerity program that fueled riots and street violence in which several hundred people were killed. In 1992, two attempted military coups threatened the Perez presidency, one led by Chávez himself, who at the time was a lieutenant colonel railing against corruption and poverty. Ultimately the legislature dismissed President Perez from office in May 1993 on charges of misusing public funds, although some observers assert that the president's unpopular economic reform program was the real reason for his ouster. The election of elder statesman and former President Rafael Caldera as president in December 1993 brought a measure of political stability to the country, but the Caldera government soon faced a severe banking crisis that cost the government more than $10 billion. While the economy began to improve in 1997, a rapid decline in the price of oil brought about a deep recession beginning in 1998, which contributed to Chávez's landslide election.

In the first several years of President Chávez's rule, Venezuela underwent huge political changes. In 1999, Venezuelans went to the polls on three occasions—to establish a constituent assembly that would draft a new constitution, to elect the membership of the 165-member constituent assembly, and to approve the new constitution—and each time delivered victory to President Chávez. The new constitution revamped political institutions, including the elimination of the Senate and establishment of a unicameral National Assembly, and expanded the presidential term of office from five to six years, with the possibility of immediate reelection for a second term. Under the new constitution, voters once again went to the polls in July 2000 for a so-called mega-election, in which the president, national legislators, and state and municipal officials were selected. President Chávez easily won election to a new six-year term, capturing about 60% of the vote. Chávez's Patriotic Pole coalition also captured 14 of 23 governorships and a majority of seats in the National Assembly.

Temporary Ouster in 2002. Although President Chávez remained widely popular until mid-2001, his standing eroded after that amid growing concerns by some sectors that he was imposing a leftist agenda on the country and that his government was ineffective in improving living conditions in Venezuela. In April 2002, massive opposition protests and pressure by the military led to the ouster of Chávez from power for less than three days. He ultimately was restored to power by the military after an interim president alienated the military and public by taking hardline measures, including the suspension of the constitution.

In the aftermath of Chávez's brief ouster from power, the political opposition continued to press for his removal from office, first through a general strike that resulted in an economic downturn in 2002 and 2003, and then through a recall referendum that ultimately was held in August 2004 and which Chávez won by a substantial margin. In 2004, the Chávez government moved to purge and pack the Supreme Court with its own supporters in a move that dealt a blow to judicial independence. The political opposition boycotted legislative elections in December 2005, which led to domination of the National Assembly by Chávez supporters.

Reelection in 2006. A rise in world oil prices that began in 2004 fueled the rebound of the Venezuelan economy and helped President Chávez establish an array of social programs and services known as "missions" that helped reduce poverty by some 20%.2 In large part because of the economic rebound and attention to social programs, Chávez was reelected to another six-year term in December 2006 in a landslide, with almost 63% of the vote compared to almost 37% for opposition candidate Manuel Rosales.3 The election was characterized as free and fair by international observers with some irregularities.

After he was reelected in 2006, however, even many Chávez supporters became concerned that the government was becoming too radicalized. Chávez's May 2007 closure of a popular Venezuelan television station that was critical of the government, Radio Caracas Television (RCTV), sparked significant protests and worldwide condemnation. Chávez also proposed a far-reaching constitutional amendment package that would have moved Venezuela toward a new model of development known as "21st century socialism," but this was defeated by a close margin in a December 2007 national referendum. University students took the lead in demonstrations against the closure of RCTV and also played a major role in defeating the constitutional reform.

The Venezuelan government also moved forward with nationalizations in key industries, including food companies, cement companies, and the country's largest steel maker; these followed the previous nationalization of electricity companies and the country's largest telecommunications company and the conversion of operating agreements and strategic associations with foreign companies in the oil sector to majority Venezuelan government control.

2008 State and Municipal Elections. State and local elections held in November 2008 revealed a mixed picture of support for the government and the opposition. Earlier in the year, President Chávez united his supporters into a single political party—the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). In the elections, pro-Chávez candidates won 17 of the 22 governors' races, while opposition parties4 won five governorships, including in three of the country's most populous states, Zulia, Miranda, and Carabobo. At the municipal level, pro-Chávez candidates won over 80% of the more than 300 mayoral races, with the opposition winning the balance, including Caracas and the country's second-largest city, Maracaibo. One of the major problems for the opposition was that the Venezuelan government's comptroller general disqualified almost 300 individuals from running for office, including several high-profile opposition candidates, purportedly for cases involving the misuse of government funds.5

2009 Lifting of Term Limits. In 2009, President Chávez moved ahead with plans for a constitutional change that would lift the two-term limit for the office of the presidency and allow him to run for reelection in 2012 and beyond. In a February 2009 referendum, Venezuelans approved the constitutional change with almost 55% support.6 President Chávez proclaimed that the vote was a victory for the Bolivarian Revolution, and virtually promised that he would run for reelection.7 Chávez had campaigned vigorously for the amendment and spent hours on state-run television in support of it. The president's support among many poor Venezuelans who had benefited from increased social spending and programs was an important factor in the vote.

2010 Legislative Elections. In Venezuela's September 2010 elections for the 165-member National Assembly, pro-Chávez supporters won 98 seats, including 94 for the PSUV, while opposition parties won 67 seats, including 65 for the MUD. Even though pro-Chávez supporters won a majority of seats, the result was viewed as a significant defeat for the president because it denied his government the three-fifths majority (99 seats) needed to enact enabling laws granting him decree powers. It also denied the government the two-thirds majority (110 seats) needed for a variety of actions to ensure the enactment of its agenda, such as introducing or amending organic laws, approving constitutional reforms, and making certain government appointments.8

In December 2010, Venezuela's outgoing National Assembly approved several laws that were criticized by the United States and human rights organizations as threats to free speech, civil society, and democratic governance. The laws were approved ahead of the inauguration of Venezuela's new National Assembly to a five-year term in early January 2011, in which opposition deputies would have had enough representation to deny the government the two-thirds and three-fifths needed for certain actions. Most significantly, the outgoing Assembly approved an "enabling law" that provided President Chávez with far-reaching decree powers for 18 months. Until its expiration in June 2012, the enabling law was used by President Chávez more than 50 times, including decrees to change labor laws and the criminal code, along with a nationalization of the gold industry.9

2012 Presidential Election. With a record turnout of 80.7% of voters, President Chávez won his fourth presidential race (and his third six-year term) in the October 7, 2012, presidential election, capturing about 55% of the vote, compared to 44% for opposition candidate Henrique Capriles.10 Chávez won all but 2 of Venezuela's 23 states (with the exception of Táchira and Mérida states), including a narrow win in Miranda, Capriles's home state. Unlike the last presidential election in 2006, Venezuela did not host international observer missions. Instead, two domestic Venezuelan observer groups monitored the vote. Most reports indicate that election day was peaceful with only minor irregularities.

Venezuela's opposition had held a unified primary in February 2012, under the banner of the opposition MUD, and chose Capriles in a landslide with about 62% of the vote in a five-candidate race. A member of the Justice First (Primero Justicia, PJ) party, Capriles had been governor of Miranda, Venezuela's second-most populous state, since 2008. During the primary election, Capriles promoted reconciliation and national unity. He pledged not to dismantle Chávez's social programs, but rather to improve them.11 Capriles ran an energetic campaign traveling throughout the country with multiple campaign rallies each day, while the Chávez campaign reportedly was somewhat disorganized and limited in terms of campaign rallies because of Chávez's health. Capriles's campaign also increased the strength of a unified opposition. The opposition received about 2.2 million more votes than in the last presidential election in 2006, and its share of the vote grew from almost 37% in 2006 to 44%.

Nevertheless, Chávez had several distinct advantages in the election. The Venezuelan economy was growing strongly in 2012 (over 5%), fueled by government spending made possible by high oil prices. Numerous social programs or "missions" of the government helped forge an emotional loyalty among Chávez supporters. This included a well-publicized public housing program. In another significant advantage, the Chávez campaign used state resources and state-controlled media for campaign purposes. This included the use of broadcast networks, which were required to air the president's frequent and lengthy political speeches. Observers maintain that the government's predominance in television media was overwhelming.12 There were several areas of vulnerability for Chávez, including high crime rates (including murder and kidnapping) and an economic situation characterized by high inflation and economic mismanagement that had led to periodic shortages of some food and consumer products and electricity outages. Earlier in 2012, a wildcard in the presidential race was Chávez's health, but in July 2012 Chávez claimed to have bounced back from his second bout of an undisclosed form of cancer since mid-2011.

For President Chávez, the election affirmed his long-standing popular support, as well as support for his government's array of social programs that have helped raise living standards for many Venezuelans. In his victory speech, President Chávez congratulated the opposition for their participation and civic spirit and pledged to work with them. At the same time, however, the president vowed that Venezuela would "continue its march toward the democratic socialism of the 21st century."13

December 2012 State Elections. Voters delivered a resounding victory to President Chávez and the PSUV in Venezuela's December 16, 2012, state elections by winning 20 out of 23 governorships that were at stake. Prior to the elections, the PSUV had held 15 state governorships with the balance held by opposition parties or former Chávez supporters. The state elections took place with political uncertainty at the national level as President Chávez was in Cuba recuperating from his fourth cancer surgery (see below). The opposition won just three states: Amazonas; Lara; and Miranda, where former MUD presidential candidate Henrique Capriles Radonski was reelected, defeating former Vice President Eliás Jaua. While the opposition suffered a significant defeat, Capriles's win solidified his status as the country's major opposition figure.

Chávez's Declining Health and Death. Dating back to mid-2011, President Chávez's precarious health raised questions about Venezuela's political future. Chávez had been battling an undisclosed form of cancer since June 2011, when he underwent emergency surgery in Cuba for a "pelvic abscess" followed by a second operation to remove a cancerous tumor. After several rounds of chemotherapy, Chávez declared in October 2011 that he had beaten cancer. In February 2012, however, Chávez traveled to Cuba for surgery to treat a new lesion and confirmed in early March that his cancer had returned. After multiple rounds of radiation treatment, Chávez once again announced in July 2012 that he was "cancer free." After winning reelection to another six-year term in October 2012, Chávez returned to Cuba the following month for medical treatment. Once back in Venezuela, Chávez announced on December 8, 2012, that his cancer had returned and that he would undergo a fourth cancer surgery in Cuba.

Most significantly, Chávez announced at the same time his support for Vice President Nicolás Maduro if anything were to happen to him. Maduro had been sworn into office on October 13, 2012. Under Venezuela's Constitution, the president has the power to appoint and remove the vice president; it is not an elected position. According to Chávez: "If something happens that sidelines me, which under the Constitution requires a new presidential election, you should elect Nicolás Maduro."14 Chávez faced complications during and after his December 11, 2012, surgery, and while there were some indications of improvement by Christmas 2012, the president faced new respiratory complications by year's end.

After considerable public speculation about the presidential inauguration scheduled for January 10, 2013, Vice President Maduro announced on January 8 that Chávez would not be sworn in on that day. Instead, the vice president invoked Article 231 of the Constitution, maintaining that the provision allows the president to take the oath of office before the Supreme Court at a later date.15 A day later, Venezuela's Supreme Court upheld this interpretation of the Constitution, maintaining that Chávez did not need to take the oath of office to remain president. According to the court's president, Chávez could take the oath of office before the Supreme Court at a later date, when his health improved.16 Some opposition leaders, as well as some Venezuelan legal scholars, had argued that the January 10 inauguration date was fixed by Article 231 and that, since Chávez could not be sworn in on that date, then the president of the National Assembly, Diosdado Cabello, should have been sworn in as interim or caretaker president until either a new election was held or Chávez recovered pursuant to Article 234 of the Constitution.17

President Chávez ultimately returned to Venezuela from Cuba on February 18, 2013, but was never seen publicly because of his poor health. A Venezuelan government official announced on March 4 that the president had taken a turn for the worse as he was battling a new lung infection. He died the following day.

The political empowerment of the poor under President Chávez will likely be an enduring aspect of his legacy in Venezuelan politics for years to come. Any future successful presidential candidate will likely need to take into account how his or her policies would affect working class and poor Venezuelans. On the other hand, President Chávez also left a large negative legacy, including the deterioration of democratic institutions and practices, threats to freedom of expression, high rates of crime and murder (the highest in South America), and an economic situation characterized by high inflation, crumbling infrastructure, and shortages of consumer goods. Ironically, while Chávez championed the poor, his government's economic mismanagement wasted billions that potentially could have established a more sustainable social welfare system benefiting poor Venezuelans.

The Post-Chávez Era, 2013-2014

When the gravity of President Chávez's health status became apparent in early 2013, many analysts had posed the question as to whether the leftist populism of "Chavismo" would endure without Chávez. In the aftermath of the April 2013 presidential election won by acting president Nicolás Maduro and the December 2013 municipal elections, it appeared that "Chavismo" would survive, at least in the medium term. Chávez supporters not only control the presidency and a majority of municipalities, but also control the Supreme Court, the National Assembly, the military leadership, and the state oil company—PdVSA. Moreover, in November 2013, President Maduro secured a needed vote of three-fifths of the National Assembly to approve an enabling law giving him decree powers over the next year. Chávez had been granted such powers for several extended periods and used them to enact far-reaching laws without the approval of Congress.

In 2014, deteriorating economic conditions, high rates of crime, and street protests that were met with violence by the Venezuelan state posed enormous challenges to the Maduro government. Human rights abuses increased as the government violently suppressed the opposition. Efforts toward dialogue at the Organization of American States were thwarted by Venezuela, and a dialogue facilitated by the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) ultimately was unsuccessful. During the second half of the year, the rapid decline in the price of oil exacerbated Venezuela's already poor economic conditions.

April 2013 Presidential Election

|

Nicolás Maduro A former trade unionist who served in Venezuela's legislature from 1998 until 2006, Nicolás Maduro held the position of National Assembly president in 2005-2006 until he was selected by President Chávez to serve as foreign minister. He retained that position until mid-January 2013, concurrently serving as vice president beginning in October 2012 when President Chávez tapped him to serve in that position following his re-election. He has often been described as a staunch Chávez loyalist. Maduro's partner since 1992 is well-known Chávez supporter Cilia Flores, who served as the president of the National Assembly from 2006 to 2011; the two were married in July 2013. |

In the aftermath of President Chávez's death, Vice President Maduro became interim or acting president and took the oath of office on March 8, 2013. A new presidential election, required by Venezuela's Constitution (Article 233), was held on April 14 in which Maduro, the PSUV candidate, narrowly defeated opposition candidate Henrique Capriles by 1.49% of the vote. In the lead-up to the elections, polling consistently showed Maduro to be a strong favorite to win the election by a significant margin, so the close race took many observers by surprise.

Before the election campaign began, many observers had stressed the importance of leveling the playing field in terms of fairness. However, just as in the 2012 presidential race between Chávez and Capriles, the 2013 presidential election was characterized by the PSUV's abundant use of state resources and state-controlled media. In particular, the mandate for broadcast networks to cover the president's speeches was a boon to Maduro.

In the aftermath of the election, polarization increased with street violence (nine people were killed in riots), and there were calls for an audit of the results. The National Electoral Council (CNE) announced that they would conduct an audit of the remaining 46% of ballot boxes that had not been audited on election day, while the opposition called for a complete recount and for reviewing the electoral registry. In June, the CNE announced that it had completed its audit of the remaining 46% of votes and maintained that it found no evidence of fraud and that audited votes were 99.98% accurate compared with the original registered totals. Maduro received 50.61% of the vote to 49.12% of the vote for Capriles—just 223,599 votes separated the two candidates out of almost 15 million votes.18

There were six domestic Venezuelan observer groups in the April election.19 This included the Venezuelan Electoral Observatory (OVE), which issued an extensive report in May 2013 that, among other issues, expressed concern over the incumbent president's advantages in the use of public funds and resources. The OVE also made recommendations for improving future elections, which included changing the composition of the CNE to guarantee and demonstrate neutrality and making improvements in legal norms related to incumbency advantage and the use of public resources, among other measures.20

Venezuela does not allow official international electoral monitoring groups, but the CNE invited several international groups to provide "accompaniment" to the electoral process. These included delegations from the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR); the Institute for Higher European Studies (IAEE, Instituto de Altos Estudios Europeos), a Spanish nongovernmental organization; and the Carter Center. The UNASUR electoral mission supported the CNE's decision to conduct a full audit, and UNASUR heads of state subsequently met on April 19 to voice their support for Maduro's election. The IAEE report issued a critical report in June 2013 calling for the elections to be voided.21

The Carter Center issued a preliminary report on the election in July 2013, and maintained that the close election results caused an electoral and political conflict not seen since Venezuela's 2004 recall election. The group also concluded that confidence in the electoral system diminished in the election, with concerns about voting conditions, including inequities in access to financial resources and the media.22 In May 2014, the Carter Center issued its final report on the 2013 election, which included recommendations to improve the process. These included more effective enforcement of rules regulating the use of state resources for political purposes and the participation of public officials and civil servants in campaign activities; campaign equity with regard to free and equal access to public and private media; curbs on the use of obligatory radio and television broadcasts and the inauguration of public works during the election period; and limitations on the participation of public officials of members of his or her own party or coalition.23

In May 2013, the opposition filed two legal challenges before the Supreme Court, alleging irregularities in the elections, including the intimidation of voters by government officials and problems with the electoral registry being inflated because it had not been purged of deceased people. The first challenge, filed May 2 by Henrique Capriles, called for nullifying the entire election, while the second challenge, filed May 7 by the MUD, requested nullification of certain election tables and tally sheets. The Supreme Court rejected the opposition challenges on August 7 and criticized them for being "insulting" and "disrespectful" of the court and other institutions.24 While the Supreme Court action was not unexpected, it contributed to increased political tensions in the country in the lead-up to the December 2013 municipal elections.

December 2013 Municipal Elections

Venezuela's December 8, 2013, municipal elections were slated to be an important test of support for the ruling PSUV and the opposition MUD, but ultimately the results of the elections were mixed and reflect a polarized country. Some 335 mayoral offices and hundreds of other local legislative councilor seats were at stake in the elections. The PSUV and its allies won 242 municipalities, compared to 75 for the MUD, and 18 won by independents. The opposition won 18 more municipalities than in the previous 2008 elections; nine state capitals, including the large cites of Maracaibo and Valencia and the capital of Barinas state (Hugo Chávez's home state); and four out of the five municipalities that make up Caracas. On the other hand, the total vote breakdown was 49% for the PSUV and its allies compared to about 42% for the MUD, not as close as the presidential election in April.25 Some observers emphasize that the PSUV did as well as it did because of President Maduro's orders to cut prices for consumer goods in the lead-up to the elections. For many observers, the elections reflect the continuing polarization in the country and a rural/urban divide, with the MUD receiving the majority of its support from urban areas and the PSUV and its allies receiving more support from rural areas.

Protests and Failed Dialogue in 2014

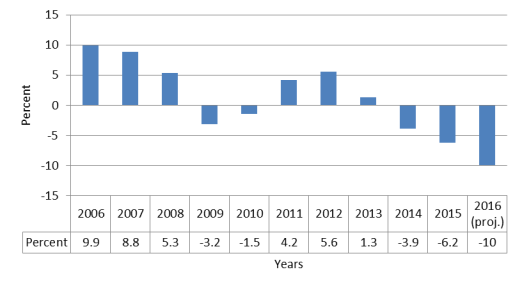

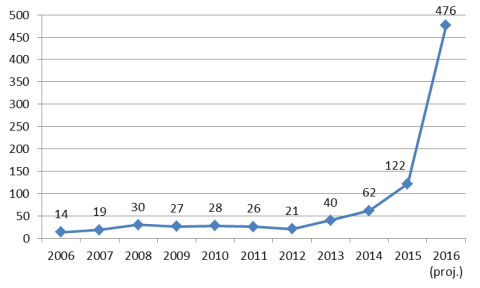

In 2014, the Maduro government faced significant challenges, including high rates of crime and violence and deteriorating economic conditions, with high inflation, shortages of consumer goods, and in the second half of the year, a rapid decline in oil prices. In February, student-led street protests erupted into violence with protestors harshly suppressed by Venezuelan security forces and militant pro-government civilian groups. While the protests largely had dissipated by June, at least 43 people were killed on both sides of the conflict, more than 800 were injured, and more than 3,000 were arrested. The government imprisoned a major opposition figure, Leopoldo López, in February, and two opposition mayors in March. Diplomatic efforts to deal with the crisis at the Organization of American States were frustrated in March. In April, an initiative by the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR)—led by the foreign ministers of Brazil, Colombia, and Ecuador—was successful in getting the government and a segment of the opposition to begin talks, but the dialogue broke down in May because of a lack of progress. With the significant drop in oil prices, the oil-dependent Venezuelan economy contracted by an estimated 3.9% by the end of the year, and inflation had risen to 62%, the highest in Latin America. (See Figure 2 and Figure 3, below.)

Protests Challenge the Government in 2014

Concern about crime prompted student demonstrations during the first week of February 2014 in western Venezuela in the city of San Cristóbal, the capital of Táchira state. Students were protesting the attempted rape and robbery of a student, but the harsh police response to the student protests led to follow-up demonstrations that expanded to other cities and intensified with the participation of non-students. There also was a broadening of the protests to include overall concerns about crime and the deteriorating economy.

On February 12, 2014, students planned a large rally in Caracas that ultimately erupted into violence when protestors were reportedly attacked by Venezuelan security forces and militant pro-government groups known as "colectivos." Three people were killed in the violence—two student demonstrators and a well-known leader of a colectivo. The protests were openly supported by opposition leaders Leopoldo López of the Popular Will party (part of the opposition alliance known as the MUD) and Maria Corina Machado, an opposition member of the National Assembly. President Maduro accused the protestors of wanting "to topple the government through violence" and to recreate the situation that occurred in 2002 when Chávez was briefly ousted from power.

Within Venezuela's political opposition, there were two contrasting views of the movement's appropriate political strategy vis-à-vis the government. Leopoldo López and María Corina Machado advocated a tactic of occupying the streets that they dubbed "la salida" (exit or solution). This conjured up the image of Maduro being forced from power. In explaining what is meant by the term, a spokesman for López's Popular Will party maintained that Maduro had many means to resolve the crisis, such as opening a real dialogue with the opposition and making policy changes, or resigning and letting new elections occur.26 (Under Venezuela's Constitution [Article 233], if Maduro were to resign, then elections would be held within 30 consecutive days.) In contrast to the strategy of street protests, former MUD presidential candidate Henrique Capriles, who serves as governor of Miranda state, advocated a strategy of building up support for the opposition, working within the existing system, and focusing on efforts to resolve the nation's problems. He did not see the message of pressing for Maduro's resignation appealing to low-income or poor Venezuelans.

Protests continued in Venezuela in Caracas and other cities around the country, although by June 2014 they had largely dissipated because of the government's harsh efforts of suppression and perhaps to some extent because of protest fatigue. Protestors had resorted to building roadblocks or barricades in order to counter government security and armed colectivos. Overall, at least 43 people on both sides of the conflict were killed (including protestors, government supporters, members of the security forces, and civilians not participating in the protests), more than 800 were injured, and more than 3,000 were arrested.27

Among the detained was opposition leader Leopoldo López. A Venezuelan court had issued an arrest warrant for López on February 13 for his alleged role in inciting riots that led to the killings. López participated in a February 18 protest march and then turned himself in. While initially López was accused of murder and terrorism, Venezuelan authorities ended up charging him with lesser counts of arson, damage to property, and criminal incitement. After several postponed court hearings, a Venezuelan judge ruled in early June 2014 that the case would go forward and that López would remain in prison while awaiting trial. López's trial began on July 23, 2014, but there were multiple delays. The Venezuelan court in the case ruled against the admissibility of much of the evidence submitted by López's defense, including more than 60 witnesses, but it accepted more than 100 witnesses for the prosecution.28 López's defense, human rights organizations, and the U.S. Department of State expressed concern about the lack of due process in the case, and President Obama called for his release.29

In addition to López, two opposition mayors, Daniel Ceballos of San Cristóbal in Táchira state and Enzo Scarano of San Diego in Carabobo state, were jailed in March 2014—Ceballos was sentenced to a year in prison on charges of "civil rebellion" and "conspiracy," and Scarano was sentenced to 10 months in prison for not complying with Supreme Court orders to remove street barricades. (Scarano was released in January 2015, and Ceballos was released to house arrest in August 2015.) Notably, the wives of both mayors won May 2014 special elections by a landslide to replace their husbands.

International human groups criticized the Venezuelan government for its heavy-handed approach in suppressing the protests.

- Amnesty International (AI) released a report in April 2014 documenting allegations of human rights violations in the context of the protests.30

- Human Rights Watch issued an extensive report in May 2014 that documented 45 cases involving more than 150 victims in which Venezuelan security forces allegedly abused the rights of protestors and other people in the vicinity of demonstrations and also allowed armed pro-government gangs to attack unarmed civilians.31

- The International Commission of Jurists, an international nongovernmental human rights organization with headquarters in Switzerland, issued a report in June 2014 highlighting key deficiencies in Venezuela's legal system that threaten the rule of law, democracy, and human rights in the country.32

For additional background on the human rights situation, see "Democracy and Human Rights Concerns," below. Table 1 also provides links to human rights organizations and other sources that report on the human rights situation in Venezuela.

Efforts Toward Dialogue

The outbreak of violence, especially the government's harsh response to the protests, prompted calls for dialogue from many quarters worldwide, including from the Obama Administration and some Members of Congress. Organization of American States (OAS) Secretary General José Miguel Insulza, U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, and Pope Francis called on efforts to end the violence and engage in dialogue. Secretary General Insulza repeatedly condemned the violence and maintained that only a broad dialogue between the government and the opposition can resolve the situation.33

Many Latin American nations had a restrained response to the situation in Venezuela. While they lamented the deaths of protestors and called for dialogue, most did not criticize the Maduro government for its harsh response to the protests.

OAS. Panama had called for a special meeting of the OAS Permanent Council in February, but the meeting was postponed on a technicality raised by Venezuela. (Venezuela subsequently broke relations with Panama in March 2014, accusing Panama of meddling in Venezuela's affairs, but relations ultimately were restored in July 2014.)

The OAS Permanent Council subsequently met on the issue of Venezuela on March 7, 2014, but only approved a lukewarm resolution expressing condolences for the violence, noting its respect for nonintervention and support for the efforts of the Venezuelan government and all political, economic, and social sectors to move forward with dialogue toward reconciliation. The United States, Canada, and Panama opposed the resolution, while all 29 other countries supported the resolution. In its dissent on the OAS vote, the United States maintained that it supports a peaceful resolution of the situation based on dialogue, but a genuine dialogue encompassing all parties and with a third party that all sides can trust.34

In a subsequent meeting on March 21, 2014, the OAS Permanent Council rejected Panama's attempt to raise the issue of the situation in Venezuela and voted (22 to 11, with 1 abstention) to close the session to the press. Panama had made Venezuelan opposition leader Maria Corina Machado a temporary member of Panama's delegation with the intention of speaking about the situation in Venezuela, but this was rejected (22 to 3, with 9 abstentions).35 (Machado subsequently was stripped of her seat in the National Assembly in late March 2014 because she joined Panama's delegation to the OAS.)

UNASUR-Sponsored Dialogue. With diplomatic efforts to help resolve the crisis frustrated in the OAS, attention turned to the work of the 12-member Union of South American Nations (UNASUR). In response to the political unrest in Venezuela, UNASUR foreign ministers had approved a resolution on March 12, 2014, expressing support for dialogue between the Venezuelan government and all political forces and social sectors and agreeing to create a commission, requested by Venezuela, to accompany, support, and advise a broad and constructive political dialogue aimed at restoring peace.36 By early April, UNASUR foreign ministers had helped to bring about an agreement for government-opposition talks to be monitored by the foreign ministers from Brazil, Colombia, and Ecuador and a representative from the Vatican as an observer.

The talks began on the evening of April 10 in a nearly six-hour public session. The opposition called for an amnesty law to free political prisoners and a disarming of the colectivos responsible for some of the violence. Before the talks, the MUD also set forth two other goals: an independent national truth commission to examine the recent unrest and a government commitment to fill senior vacancies in such institutions as the National Electoral Council and the Supreme Court with appointments that demonstrate impartiality.37 Two additional rounds of private talks between the opposition and the government were held in April, with limited progress. On May 13, the MUD announced that the talks were in crisis and that the opposition was suspending its participation until the government took actions to demonstrate its commitment to the process. The government's continued suppression of protests since the talks began, along with lack of concrete progress at the talks, were the key factors in the MUD's decision to suspend the dialogue.

Despite attempts by the foreign ministers of Brazil, Colombia, and Ecuador, the talks were not revived. UNASUR issued a statement May 23 reiterating that dialogue between the government and opposition sectors is necessary for resolving the conflict. In the statement, UNASUR also rejected the imposition of unilateral sanctions on Venezuelan officials, maintaining that the action would violate the principle of nonintervention and negatively affect the prospects for dialogue.38

When the UNASUR-sponsored dialogue began, there was disagreement within the MUD coalition over whether to participate in the talks. To some extent, this harkened back to disagreement over the opposition's overall political strategy noted above. More moderate opposition parties supported the decision to participate in the talks, while more hardline parties refused to participate as long as protestors and opposition leaders remain jailed. Leopoldo López's Popular Will party maintained that the government was "only offering a political show" and stated that it would not "endorse any dialogue with the regime while repression, imprisonment and persecution of our people continues."39 Other opposition activists refusing to participate included Maria Corina Machado and Antonio Ledezma, the metropolitan mayor of Caracas.

In the aftermath of the 2014 protests and the collapse of dialogue, Venezuela's opposition appeared to have become more divided, with some wanting to continue a confrontational approach of challenging the government through protests and calling for the president's resignation and others advocating a more moderate approach of focusing on the 2015 legislative elections and advancing solutions that appeal to a majority of Venezuelans. Former MUD presidential candidate Henrique Capriles maintained that the strategy of "la salida" (the exit) was "an absolute failure" that "gave oxygen to the government" and "distracted the country." He maintained that divisions within the opposition prevented it from taking advantage of the government's inability to improve the economy.40

Political and Economic Environment in 2015-2016

|

Venezuela at a Glance Population: 30.69 million (2014, WB). Area: 912,050 square kilometers (slightly more than twice the size of California) GDP: $260 billion (2015, current prices, IMF est.). GDP Growth (%): -3.9% (2014); -6.2% (2015); -10% (2016 forecast) (IMF). GDP Per Capita Income: $8,494 (2015, current prices, IMF est.) Key Trading Partners: Exports—U.S. 38%, India 19.6%, China 16.7%. Imports—U.S. 29%, China, 18.5%, Brazil, 12% (2015, EIU). Life Expectancy: 74.2 years (2014, WB) Literacy: 95.5% (2013, UNDP) Legislature: National Assembly (unicameral), with 167 members. Sources: Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU); International Monetary Fund (IMF); World Bank (WB); United Nations Development Programme (UNDP); and U.S. Department of State. |

The political and economic situation in Venezuela continued to deteriorate in 2015 and 2016, with the Maduro government continuing its repression of the political opposition, the economy entering deeper into recession, with a growing humanitarian crisis.

In February 2015, Venezuela's intelligence service detained the opposition metropolitan mayor of Caracas, Antonio Ledezma, who was subsequently charged with conspiracy in an alleged plot to overthrow the government. (He was released from jail in April 2015 for surgery and has been under house arrest since June 2015.) Ledezma, along with Leopoldo López (imprisoned since 2014) had signed a communiqué entitled the "National Agreement for Transition" to take measures to overcome the country's political and economic crisis, including free and transparent presidential elections.41 The Maduro government viewed the document as tantamount to calling for the government's overthrow and similar to the "la salida" (exit or solution) strategy adopted by López in 2014 that tried to force Maduro from power through street protests.

December 2015 Legislative Elections and Aftermath

Venezuela's opposition coalition, known as the MUD, triumphed in the country's December 6, 2015, legislative elections over the ruling PSUV. In the official vote count, the MUD won 109 seats, which, combined with the support of 3 elected indigenous representatives, gave it a total of 112 seats in the 167-member unicameral National Assembly, a two-thirds majority, compared to 55 seats for the PSUV. The election was a major defeat for Chavismo but, as noted below, the Maduro government took actions to deny the opposition its supermajority.

The opposition had faced significant disadvantages in the legislative elections. OAS Secretary General Luis Almagro made public a letter to the head of Venezuela's National Electoral Council that expressed strong criticism about the level of transparency and electoral justice ahead of the elections. Almagro asserted that the opposition operated on an uneven playing field that included the government's use of state resources for campaign purposes; the disqualification of seven opposition candidates; the judiciary's investigation of opposition political parties; and government actions that diminished freedom of the press and expression. In a disturbing development before the elections, Luis Manuel Díaz, an opposition leader with Democratic Action (AD), was assassinated at a public meeting in the state of Guárico on November 25, 2015. Venezuela rejected any international election observation missions, including from the OAS and the European Union. Instead, it agreed to a delegation from the UNASUR that arrived just before the elections. In the absence of international observers, electoral observation by Venezuelan domestic groups, such as the Observatorio Electoral Venezolano, became all the more important.

Ahead of the legislative elections, the MUD was far ahead in the polls, with a lead ranging from almost 19 percentage points to 30 percentage points. It campaigned on an agenda to release political prisoners and efforts to stimulate the ailing economy. The coalition includes some two dozen parties across the political spectrum. The largest of these include Justice First (PJ), the party of the MUD's 2012 and 2013 presidential candidate, Henrique Capriles; Popular Will (VP), whose party founder, Leopoldo López, was imprisoned in February 2014 and sentenced in September 2015 to almost 14 years in prison for allegedly inciting violence and other charges (a conviction that was criticized worldwide); A New Era (UNT); and AD.

In the aftermath of the MUD's electoral victory, the Maduro government thwarted the power of the incoming opposition legislature. To secure control of the 32-member Supreme Court, the outgoing PSUV-controlled National Assembly confirmed 13 new magistrates whose terms were not up until the end of 2016. In doing so, the outgoing National Assembly prevented the new opposition-controlled National Assembly from confirming the judges. The Supreme Court subsequently blocked three newly elected National Assembly representatives (all from the state of Amazonas) from the MUD from taking office, which deprived the opposition of its two-thirds majority. A two-thirds majority would have provided the opposition with extensive powers, including the abilities to submit bills directly to national referendum, approve and amend organic laws, remove Supreme Court Justices in cases of serious misconduct, and convene a Constituent Assembly to rewrite the constitution. Nevertheless, a simple and a three-fifths majority are supposed to convey significant power to the opposition, including providing it with a major role in the government's budget, the ability to remove ministers and the vice president from office, and powers to overturn enabling laws that give the president decree powers.

Since the National Assembly took office in January 2016, the Supreme Court has blocked several laws and actions approved by the legislature. In February, the Supreme Court upheld President Maduro's emergency economic decree, which the National Assembly had rejected in January; the measure provides the president with broad enabling powers circumventing the powers of the legislature.42 In March, the Supreme Court ruled that the legislature had no right to examine the Maduro government's rushing through of 13 magistrates in late 2015.43 In April, the court declared an amnesty law unconstitutional on grounds that it would have granted impunity for common crimes; the measure would have pardoned opposition leader Leopoldo López and other political prisoners—about 120 in all.44 In April, the court also struck down a constitutional amendment that would have reduced the presidential term of office from six years to four years, maintaining that any constitutional change could not be retroactive.45 In July 2016, Venezuela's National Assembly swore in the three opposition legislators that the Supreme Court had blocked from taking office, which led the Supreme Court to rule in early September that the National Assembly's bills would be "null and void."46 In November 2016, the three legislators stepped down as a concession to ease tension between the government and the opposition.

Efforts to Recall President Maduro

With the power of the National Assembly stymied by the Maduro government, opposition efforts for much of 2016 focused on attempts to recall President Maduro in a national referendum. The government, however, resorted to delaying tactics that slowed down the process considerably, and on October 20, 2016, Venezuela's National Electoral Council (CNE) indefinitely suspended the process after five state-level courts issued rulings alleging fraud in a signature collection drive held in June.

The opposition had been working for a recall referendum to be held before January 10, 2017, the four-year point of the six-year presidential term. Under Venezuela's constitution, if the recall were approved after January 10, 2017, the appointed vice president would become president for the remainder of the presidential term. (On January 4, 2017, President Maduro appointed former Interior Minister and Governor of Aragua state Tareck El Aissami as vice president, replacing Aristóbulo Istúriz, a former governor of Anzoátegui state who served in the position for one year.) If the recall had been held before January 10, 2017, a new presidential election would have been called within 30 days, giving the opposition an opportunity to compete for the presidency before the next regularly scheduled election in late 2018.

Multiple steps are required for the referendum to go forward. The recall process began in April 2016; Venezuela's CNE released forms needed to begin the procedure of seeking a recall referendum, but it did so only after several opposition National Assembly legislators had chained themselves to the CNE's office to protest the body's refusal to provide the paperwork.

The opposition then needed to collect signatures from 1% of Venezuela's electorate in each state—almost 198,000 signatures nationwide. On May 2, 2016, the opposition delivered more than 1.95 million signatures to the CNE. On June 10, the CNE announced that it had disqualified 605,727 of the signatures but that the remaining 1.35 million signatures were ready to be validated. The validation process began June 20 and was not completed until August 1, 2016, when the CNE announced that the opposition had successfully collected the signatures.

The next step was for the opposition to gather the signatures of at least 20% of registered voters—about 3.9 million signatures. Initially, the CNE announced in August 2016 that the collection of 20% of signatures would possibly take place at the end of October. Then, on September 21, 2016, the CNE announced that the signature drive would be held over a three-day period from October 26, 2016, to October 28, 2016. As part of the process, the CNE approved 5,392 voting machines (in 1,356 voting centers) for more than 19 million registered voters and is requiring the signatures of 20% of registered voters in each state.47 (In contrast, the opposition wanted some 19,500 voting machines to be made available and for the requirement of 20% of signatures collected to be at the national level instead of required for each state.) As noted above, the CNE suspended the recall referendum process on October 20, 2016, and the signature collection did not take place.

If the signature collection had taken place, the next step would have been for the CNE to verify that enough signatures were received. If so, the referendum would have taken place within 90 days. For the recall of the president to occur, the referendum would have needed to be approved by more than the number of votes that Maduro received when elected—almost 7.6 million.

Major opposition protests occurred at several junctures over the government's delays with the recall referendum process. In May 2016, opposition protests erupted over the CNE's slowness in verifying the signatures collected. On May 13, 2016, President Maduro decreed a 60-day national emergency, maintaining that there were plots supported by the United States to topple his government. Protests continued despite the state of emergency, and a number of protesters were arrested. On June 9, several opposition National Assembly members, including majority leader Julio Borges, were physically attacked by armed PSUV supporters after they were turned away from the CNE by police. On September 1, 2016, hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans protested peacefully in Caracas to press for the recall referendum to be held this year. The CNE's suspension of the recall referendum process prompted massive protests in cities nationwide on October 26, 2016.

OAS Efforts on Venezuela48

|

Article 20 of the Inter-American Democratic Charter In the event of an unconstitutional alteration of the constitutional regime that seriously impairs the democratic order in a member state, any member state or the Secretary General may request the immediate convocation of the Permanent Council to undertake a collective assessment of the situation and to take such decisions as it deems appropriate. The Permanent Council, depending on the situation, may undertake the necessary diplomatic initiatives, including good offices, to foster the restoration of democracy. If such diplomatic initiatives prove unsuccessful, or if the urgency of the situation so warrants, the Permanent Council shall immediately convene a special session of the General Assembly. The General Assembly will adopt the decisions it deems appropriate, including the undertaking of diplomatic initiatives, in accordance with the Charter of the Organization, international law, and the provisions of this Democratic Charter. The necessary diplomatic initiatives, including good offices, to foster the restoration of democracy, will continue during the process. |

OAS Secretary General Luis Almagro has spoken out strongly about the situation in Venezuela. On May 18, 2016, the Secretary General published a public letter to President Maduro, partly in response to Maduro's accusations that Almagro was an agent of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).49 Almagro called for Maduro to "return the riches of those who have governed with you to your country ... to return political prisoners to their families ... [and] ... to give the National Assembly back its legitimate power." He expressed hope that no one should commit the folly of carrying out a coup against Maduro and that Maduro himself would not do so (Maduro threatened to make the National Assembly disappear).50 With regard to the recall referendum, Almagro said, "You have an obligation to public decency to hold the recall referendum in 2016, because when politics are polarized the decision must go back to the people. To deny the people that vote, to deny them the possibility of deciding, would make you just another petty dictator, like so many this Hemisphere has had."

On May 31, 2016, Secretary General Almagro invoked the Inter-American Democratic Charter when he called (pursuant to Article 20) on the OAS Permanent Council to convene an urgent session on Venezuela to decide whether "to undertake the necessary diplomatic efforts to promote the normalization of the situation and restore democratic institutions." The Secretary General issued an extensive report on the political and economic situation in Venezuela concluding that there are "serious disruptions of the democratic order" in the country. The report made several recommendations, including the holding of a recall referendum in 2016, the immediate release of all those imprisoned for political reasons, and a halt to the executive branch's permanent blocking of laws adopted by the National Assembly. According to the Secretary General's report, the situation requires that the hemispheric community assume its responsibility for moving forward with the procedure outlined in Article 20 in a progressive and gradual manner.51

Prior to the Secretary General's action, the leadership of Venezuela's National Assembly had asked Almagro to invoke the charter, contending that the Venezuelan government had acted in an unconstitutional and antidemocratic fashion that had severely undermined and impaired the democratic order. They maintained that "there exists a grave crisis of democracy, of the rule of law, and of human rights ... a clear impairment of the essential elements of representative democracy" set forth in the charter.52 Human Rights Watch also called for the OAS to invoke the charter "to press Venezuela to restore judicial independence and the protection of fundamental rights."53 The Maduro government has strongly opposed OAS involvement in Venezuela's political situation, arguing that the Secretary General is a pawn of the United States.54

Separate from considering the Secretary General's report, the OAS Permanent Council met on June 1, 2016, to consider a draft declaration on the situation in Venezuela submitted by Argentina and co-sponsored by Barbados, Honduras, Mexico, Peru, and the United States. Before its adoption by consensus, the resolution was amended at the behest of Venezuela to add language noting respect for the "principle of non-intervention" and "full respect for … [Venezuela's] sovereignty," but it kept key provisions of the original resolution. As approved, the declaration offered Venezuela support to identify a course of action to search for solutions through open and inclusive dialogue, supported the initiative of the former leaders of Spain (José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero), the Dominican Republic (Leonel Fernández), and Panama (Martin Torrijos) to reopen an effective dialogue between the government and the opposition, and supported other dialogue efforts that could lead to the resolution of differences and the consolidation of representative democracy.55 At Venezuela's request, the Permanent Council held a special meeting on June 21 to hear from former President Rodríguez Zapatero about the status of the dialogue initiative.

With regard to the Secretary General's request invoking Article 20, the Permanent Council held a special session on June 23, 2016, to receive the presentation of the Secretary General's report. Venezuela had argued that the meeting itself should not be held, but a majority of countries voted to proceed with the agenda for the session. Nevertheless, the Permanent Council did not take any action on the Secretary General's report. When the Secretary General originally called the meeting, he wanted the Permanent Council to decide (by majority vote of 18 of 34 members) if it agreed with his report concluding that an alteration of the constitutional regime had taken place and, if so, what diplomatic initiatives may be taken, such as the offering of "good offices" (e.g., serving as a mediator or facilitating dialogue) to resolve the situation.56

On June 15, 2016, at the OAS General Assembly held in the Dominican Republic, 15 of 34 OAS member states—including the United States, along with Argentina, Belize, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay—issued a statement on the situation in Venezuela that reaffirmed the Permanent Council resolution adopted on June 1, 2016. In the statement, the 15 member states expressed support for a "timely, national, inclusive, and effective political dialogue"; encouraged respect for the Venezuelan constitution, which enshrines "the separation of powers, respect for the rule of law and democratic institutions"; expressed support "for the fair and timely implementation of constitutional mechanisms"; condemned "violence regardless of its origin"; and called on the "responsible authorities to guarantee due process and human rights, including the right to peaceful assembly and free expression of ideas."57