“Stage One” U.S.-Japan Trade Agreements

On October 7, 2019, after six months of formal negotiations, the United States and Japan signed two agreements intended to liberalize bilateral trade. One, the U.S.-Japan Trade Agreement (USJTA), provides for limited tariff reductions and quota expansions to improve market access. The other, the U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement, includes commitments pertaining to digital aspects of international commerce, such as cross-border data flows. These agreements constitute what the Trump and Abe Administrations envision as “stage one” of a broader trade liberalization negotiation, which the two leaders first announced in September 2018. The two sides have stated their intent to continue negotiations on a more comprehensive deal after these agreements enter into force. Congress has an interest in U.S.-Japan trade agreement negotiations given congressional authority to regulate foreign commerce and the agreements’ potential effects on the U.S. economy and constituents.

USJTA is to reduce or eliminate tariffs on agriculture and some industrial goods, covering approximately $14.4 billion ($7.2 billion each of U.S. imports and exports) or 5% of bilateral trade. The United States is to reduce or eliminate tariffs on a small number (241) of mostly industrial goods, while Japan is to reduce or eliminate tariffs on roughly 600 agricultural tariff lines and expand preferential tariff-rate quotas for a limited number of U.S. products. The United States framed the digital trade commitments as “gold standard,” with commitments on nondiscriminatory treatment of digital products, and prohibition of data localization barriers and restrictions on cross-border data flows, among other provisions. The stage one agreement excludes most other goods from tariff liberalization and does not cover market access for services, rules beyond digital trade, or nontariff barriers. Notably, the agreement does not cover trade in autos, an industry accounting for one-third of U.S. imports from Japan. Japan’s decision to participate in bilateral talks came after President Donald Trump threatened to impose additional auto tariffs on Japan, based on national security concerns.

Prior to the Trump Administration, the United States negotiated free trade agreements (FTAs) that removed virtually all tariffs between the parties and covered a broad range of trade-related rules and disciplines in one comprehensive negotiation, driven in significant part by congressionally mandated U.S. negotiating objectives. Nontariff issues often require implementing legislation by Congress to take effect, and Congress has typically considered implementing legislation for past U.S. FTAs through expedited procedures under Trade Promotion Authority (TPA). The Trump Administration, however, plans to put the stage one agreements with Japan into effect without action by Congress. The Administration plans to use delegated tariff authorities in TPA to proclaim the USJTA market access provisions, while the U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement does not appear to require changes to U.S. law and is being treated as an Executive Agreement. Japan’s Diet (the national legislature) ratified the pact in December 2019. The Administration expects the agreements to take effect in early 2020, with negotiations on the second stage of commitments to begin within four months.

The Trump Administration’s interest in bilateral trade negotiations is tied to its withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement in 2017, which included the United States and Japan, along with 10 other Asia-Pacific countries. In general, TPP was far more comprehensive than the stage one U.S.-Japan agreements, as it would have eliminated most tariffs among the parties and created rules and disciplines on a number of trade-related issues, such as intellectual property rights and services. Japan’s FTAs with other countries, including the TPP-11, which entered into force among the remaining TPP members in 2018, and an FTA with the European Union (EU), which took effect in 2019, have led to growing concerns among U.S. industry and many in Congress that U.S. exporters face certain disadvantages in the Japanese market. The USJTA will largely place U.S. agricultural exporters on par with Japan’s other FTA partners with regard to tariffs, but unlike the TPP and its successor, the agreement excludes some agricultural products, such as rice and barley. It also does not include rules, such as on technical barriers to trade (TBT) and sanitary and phytosanitary measures, and therefore will not address various nontariff barriers U.S. agriculture and other industries face in Japan. Thus, U.S. agricultural exporters may continue to be at some disadvantage in the Japanese market compared to those from TPP countries or the EU.

In general, Congress and U.S. stakeholders support the agreements due to the expected benefits to U.S. agriculture and cross-border digital trade. At the same time, the overall economic effects of the agreement are likely to be modest due to the limited scope of the agreement. Many observers contend the deal should not be a substitute for a comprehensive trade agreement and view the second stage of talks as critical to U.S. interests. If more comprehensive negotiations begin in 2020, they may become intertwined with other bilateral issues, such as concerns among many Japanese officials that the United States has a waning interest in maintaining its current influence in East Asia, and upcoming negotiations over the renewal of the U.S.-Japan agreement on how to share the costs of basing U.S. military troops in Japan. Some Members of Congress have also raised questions over whether the staged approach to the U.S.-Japan negotiations is in the best interest of the United States, and what it may mean for future U.S. trade agreement negotiations. There are also questions about whether the agreements adhere to multilateral trade rules under the World Trade Organization (WTO), given their limited scope, and whether the Administration has adequately consulted with Congress in its negotiation and implementation of the new agreements.

"Stage One" U.S.-Japan Trade Agreements

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Background and Motivation for Negotiations

- Agriculture and Japan's Other Trade Agreements

- Motor Vehicles and Threat of U.S. Section 232 Tariffs

- U.S. Trade Agreement Authorities

- Agreement Provisions

- U.S.-Japan Trade Agreement (Tariff and Quota Commitments)

- U.S. Tariff and Quota Commitments

- Japan's Tariff and Quota Commitments

- U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement

- Views and Next Steps

- U.S. Views

- Japanese Views

- Next Steps

- Issues for Congress

- Congressional Role in Limited Scope and Staged Agreements

- Staged Negotiation or Comprehensive Deal

- Section 232 Auto Tariff Threat

- WTO Compliance

- Comparison to TPP (and TPP-11) and Strategic Considerations

Figures

Summary

On October 7, 2019, after six months of formal negotiations, the United States and Japan signed two agreements intended to liberalize bilateral trade. One, the U.S.-Japan Trade Agreement (USJTA), provides for limited tariff reductions and quota expansions to improve market access. The other, the U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement, includes commitments pertaining to digital aspects of international commerce, such as cross-border data flows. These agreements constitute what the Trump and Abe Administrations envision as "stage one" of a broader trade liberalization negotiation, which the two leaders first announced in September 2018. The two sides have stated their intent to continue negotiations on a more comprehensive deal after these agreements enter into force. Congress has an interest in U.S.-Japan trade agreement negotiations given congressional authority to regulate foreign commerce and the agreements' potential effects on the U.S. economy and constituents.

USJTA is to reduce or eliminate tariffs on agriculture and some industrial goods, covering approximately $14.4 billion ($7.2 billion each of U.S. imports and exports) or 5% of bilateral trade. The United States is to reduce or eliminate tariffs on a small number (241) of mostly industrial goods, while Japan is to reduce or eliminate tariffs on roughly 600 agricultural tariff lines and expand preferential tariff-rate quotas for a limited number of U.S. products. The United States framed the digital trade commitments as "gold standard," with commitments on nondiscriminatory treatment of digital products, and prohibition of data localization barriers and restrictions on cross-border data flows, among other provisions. The stage one agreement excludes most other goods from tariff liberalization and does not cover market access for services, rules beyond digital trade, or nontariff barriers. Notably, the agreement does not cover trade in autos, an industry accounting for one-third of U.S. imports from Japan. Japan's decision to participate in bilateral talks came after President Donald Trump threatened to impose additional auto tariffs on Japan, based on national security concerns.

Prior to the Trump Administration, the United States negotiated free trade agreements (FTAs) that removed virtually all tariffs between the parties and covered a broad range of trade-related rules and disciplines in one comprehensive negotiation, driven in significant part by congressionally mandated U.S. negotiating objectives. Nontariff issues often require implementing legislation by Congress to take effect, and Congress has typically considered implementing legislation for past U.S. FTAs through expedited procedures under Trade Promotion Authority (TPA). The Trump Administration, however, plans to put the stage one agreements with Japan into effect without action by Congress. The Administration plans to use delegated tariff authorities in TPA to proclaim the USJTA market access provisions, while the U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement does not appear to require changes to U.S. law and is being treated as an Executive Agreement. Japan's Diet (the national legislature) ratified the pact in December 2019. The Administration expects the agreements to take effect in early 2020, with negotiations on the second stage of commitments to begin within four months.

The Trump Administration's interest in bilateral trade negotiations is tied to its withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement in 2017, which included the United States and Japan, along with 10 other Asia-Pacific countries. In general, TPP was far more comprehensive than the stage one U.S.-Japan agreements, as it would have eliminated most tariffs among the parties and created rules and disciplines on a number of trade-related issues, such as intellectual property rights and services. Japan's FTAs with other countries, including the TPP-11, which entered into force among the remaining TPP members in 2018, and an FTA with the European Union (EU), which took effect in 2019, have led to growing concerns among U.S. industry and many in Congress that U.S. exporters face certain disadvantages in the Japanese market. The USJTA will largely place U.S. agricultural exporters on par with Japan's other FTA partners with regard to tariffs, but unlike the TPP and its successor, the agreement excludes some agricultural products, such as rice and barley. It also does not include rules, such as on technical barriers to trade (TBT) and sanitary and phytosanitary measures, and therefore will not address various nontariff barriers U.S. agriculture and other industries face in Japan. Thus, U.S. agricultural exporters may continue to be at some disadvantage in the Japanese market compared to those from TPP countries or the EU.

In general, Congress and U.S. stakeholders support the agreements due to the expected benefits to U.S. agriculture and cross-border digital trade. At the same time, the overall economic effects of the agreement are likely to be modest due to the limited scope of the agreement. Many observers contend the deal should not be a substitute for a comprehensive trade agreement and view the second stage of talks as critical to U.S. interests. If more comprehensive negotiations begin in 2020, they may become intertwined with other bilateral issues, such as concerns among many Japanese officials that the United States has a waning interest in maintaining its current influence in East Asia, and upcoming negotiations over the renewal of the U.S.-Japan agreement on how to share the costs of basing U.S. military troops in Japan. Some Members of Congress have also raised questions over whether the staged approach to the U.S.-Japan negotiations is in the best interest of the United States, and what it may mean for future U.S. trade agreement negotiations. There are also questions about whether the agreements adhere to multilateral trade rules under the World Trade Organization (WTO), given their limited scope, and whether the Administration has adequately consulted with Congress in its negotiation and implementation of the new agreements.

Introduction

On October 7, 2019, after six months of formal negotiations, the United States and Japan signed two agreements intended to liberalize bilateral trade.1 One, the U.S.-Japan Trade Agreement (USJTA), provides for limited tariff reductions and quota expansions to improve market access. The other, the U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement, includes commitments pertaining to digital aspects of international commerce, such as on data flows. These agreements constitute what President Donald Trump and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe envision as "stage one" of a broader trade liberalization negotiation, which the two leaders first announced in September 2018.2 The two sides have stated their intent to begin second stage negotiations on a more comprehensive deal after these agreements enter into force.

Congress will not have a role in approving the two agreements. The Trump Administration intends to use delegated tariff proclamation authorities in Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) to enact the tariff changes and quota modifications, while the digital trade commitments, which would not require changes to U.S. law, are in the form of an Executive Agreement. Japan's Diet (the national legislature), however, had to ratify the pact, and did so on December 5, 2019, paving the way for entry into force on January 1, 2020. The two Japan deals raise a number of issues for Congress, including their limited coverage and staged approach, as compared to past U.S. free trade agreement (FTA) negotiations, the trade authorities used to bring them into effect in the United States, questions over their compliance with World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, and questions over how they compare with the trade agreement the United States previously negotiated with Japan in the former Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and current TPP-11.

Given the narrow scope of the agreements, particularly the USJTA tariff commitments, their commercial and strategic impact is likely to be determined by whether a more comprehensive bilateral agreement can be achieved. Many Members of Congress and other stakeholders support the agreements, but view the prospective second stage of trade talks as critical for U.S. interests. At the same time, some observers have raised questions about the potential coverage of issues in future talks and whether there will be sufficient political support in both countries to make progress, especially during an election year in the United States.

Background and Motivation for Negotiations

In October 2018, in line with TPA requirements under the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-26; TPA-2015), the Administration provided Congress 90 days advance notification of its intent to begin negotiations. The Administration released its negotiating objectives, which included a number of issues beyond tariffs and digital trade, in December of the same year.3

The Trump Administration's interest in a trade agreement with Japan is closely tied to its decision to withdraw the United States from the TPP in 2017,4 and to pursue bilateral agreements, as opposed to the more regional approach taken under TPP.5 It also reflects the Administration's strategy of focusing on reaching agreements with major U.S. trade partners, especially those with which the United States runs a trade deficit (the U.S. goods trade deficit with Japan was $67.2 billion in 2018, the fourth-largest bilateral U.S. deficit).6 Although TPP included 10 countries in addition to the United States and Japan, the U.S.-Japan component of the agreement was the most economically consequential given existing U.S. trade agreements with 6 of the 10 other participants, and the relatively small economies of the remaining four (Brunei, Malaysia, New Zealand, and Vietnam).7

In these limited, stage one agreements with Japan, the Administration has attempted to address concerns raised by TPP proponents, especially agricultural groups, that the U.S. withdrawal placed U.S. exporters at a disadvantage in the Japanese market, in particular given Japan's recently enacted trade agreements with other trade partners.8 Following U.S. withdrawal from the TPP, Japan led efforts among the remaining 11 TPP countries to conclude the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP or TPP-11), which took effect in December 2018 for the first six signatories who ratified, including Japan, and for Vietnam in early 2019. The TPP-11 includes the comprehensive tariff liberalization commitments of TPP (near complete elimination among the parties), and the majority of TPP rules and disciplines on numerous trade-related issues, though the parties agreed to suspend a small number of nontariff commitments sought largely by the United States, following the U.S. withdrawal.9

Japan's FTA with the European Union (EU), which is to eventually remove nearly all tariffs and establish trade rules between the parties, went into effect in February 2019.10 It provides for elimination of the EU's 10% auto tariff, and elimination or reduction of most Japanese agricultural tariffs. Additional trade agreements involving Japan could take effect in coming years, compounding U.S. exporter concerns, including the possible 2020 conclusion of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which includes Japan, China, and 13 other Asian countries.11

Given Japan's commitment to TPP, Prime Minister Abe was initially hesitant to agree to bilateral U.S. trade negotiations, instead urging the Trump Administration to reconsider its withdrawal.12 Japan's decision to participate in bilateral talks came after President Trump raised the possibility, based on national security concerns, of imposing unilateral motor vehicle tariffs on Japan, an industry of national significance and accounting for one-third of U.S. goods imports from Japan (see "Motor Vehicles and Threat of U.S. Section 232 Tariffs"). The importance of the U.S.-Japan security relationship may also have factored into Japan's decisionmaking. Japan relies heavily on the United States for its military defense. The two countries' agreement on how to share the costs of the roughly 50,000 U.S. troops stationed in Japan is due to be renegotiated in 2020 as the current agreement expires at the end of March 2021. President Trump has called for Japan to significantly increase its contributions, perhaps by as much as fourfold.13 Japan, some analysts suggest, may see a bilateral trade agreement as way to reduce tension in the bilateral relationship, in light of other pressing security issues.14 Additionally, the Trump Administration may try to use the cost-sharing negotiations to extract concessions from Japan in proposed stage-two trade negotiations, or vice versa.

As the United States' fourth-largest trading partner and the world's third-largest economy, Japan routinely features prominently in U.S. trade policy. In 2018, Japan accounted for 5% of total U.S. exports ($121 billion) and 6% of total U.S. imports ($179 billion).15 The United States is arguably even more important to Japan, representing its second-largest trading partner after China in 2018, and accounting for nearly 20% of Japan's goods exports.16 The two countries are also major investment partners, with Japanese foreign direct investment (FDI) in the United States valued at $484 billion in 2018 on a historical cost basis, largely in manufacturing, and U.S. FDI in Japan valued at $125 billion, concentrated in finance and insurance. Major areas of U.S. focus in the trade relationship include market access for U.S. agricultural goods, given Japan's relatively high tariffs in this sector, and the elimination of various nontariff barriers, such as in the motor vehicles and services sectors.17

Agriculture and Japan's Other Trade Agreements

|

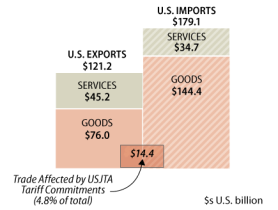

Figure 1. U.S. Agriculture Exports to Japan, 2018 (in U.S. $ billions) |

|

|

Source: U.S. Census Bureau trade data, accessed via U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS), September 2019, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/default.aspx. Note: Based on USDA's definition of agriculture. |

Japan is an important market for U.S. farmers and ranchers, accounting for about 9% of total U.S. agricultural exports to all destinations since 2014.18 In 2018, Japan was the third-largest export market for the United States, after Canada and Mexico, with $12.9 billion in U.S. agricultural exports—out of a total of $140 billion—shipped to Japan. Corn, beef, pork, soybeans, and wheat make up more than 60% of total U.S. agricultural exports to Japan (Figure 1).

With TPP-11 and the EU-Japan FTA entering into force in late 2018 and early 2019, exports from EU and TPP-11 member countries became more competitive for Japanese importers. U.S. agricultural exports to Japan meanwhile declined 7% ($8.3 billion) from January through August 2019, compared with the same period in 2018 ($9 billion).19 According to Japanese Customs data, notable product-specific declines during the first nine months of 2019, compared to the same period in 2018, include non-durum wheat (down 13%), pork (down 7%), and beef (down 4%).20 Over the same period, Japanese imports of these commodities from several EU and TPP-11 countries have increased.21 With the stage one U.S.-Japan agreement resulting in lower tariff rates on most U.S. agricultural products in the near term, it could improve the outlook for U.S. agricultural exporters.

Motor Vehicles and Threat of U.S. Section 232 Tariffs

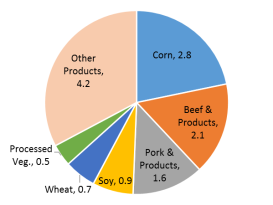

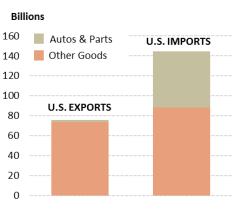

Motor vehicles and parts are the largest U.S. import category from Japan ($56.0 billion in 2018), while Japan imports few U.S.-made autos ($2.4 billion in 2018), despite having no auto tariffs (Figure 2).22 U.S. industry argues the latter stems from nontariff barriers, including discriminatory regulatory treatment,23 while Japan argues that U.S. producers' inability to cater to the Japanese market is to blame. Although Japan buys few U.S. cars, Japanese-owned production facilities in the United States (valued at $51 billion in 2018) employ more than 170,000 workers, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).24 President Trump has repeatedly flagged the U.S. automotive trade deficit and noted that U.S. goals in broader trade talks include market access outcomes that will increase U.S. auto production and employment, but no provisions on motor vehicles were included in the stage one agreement.

|

Figure 2. U.S.-Japan Goods Trade, 2018 (in U.S. $ billions) |

|

|

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). |

In May 2019, one year after the start of an investigation by the U.S. Department of Commerce under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 (19 U.S.C. §1862), President Trump proclaimed motor vehicle and parts imports, particularly from Japan and the EU, a threat to U.S. national security.25 This determination asserted that the imports affect "American-owned" producers' global competitiveness and research and development on which U.S. military superiority depends. Under affirmative Section 232 determinations, the President is granted authority to impose import restrictions, including tariffs. Toyota and other Japanese-owned auto firms took particular issue with the President's emphasis on U.S. ownership in his determination, noting their significant U.S. investments in automotive manufacturing and research facilities.26 The President directed the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) to negotiate with Japan (and the EU) to address this threat and report back within 180 days.27 Speaking immediately after the signing of the USJTA, USTR Lighthizer stated that in light of the new trade agreement, the Administration has no intent, "at this point," to pursue additional Section 232 U.S. auto import restrictions.28 Japan also remains subject to Section 232 tariffs on U.S. steel and aluminum imports, which the Administration implemented in March 2018.

U.S. Trade Agreement Authorities

Congress sets objectives for U.S. trade negotiations and establishes certain authorities to enact agreements that make progress toward achieving those objectives in Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) legislation under the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-26; TPA-2015).29 TPA allows for expedited consideration of implementing legislation to enact trade agreements covering tariff and nontariff barriers, provided the Administration meets certain notification and consultation requirements. It also provides the President, under Section 103(a) (19 U.S.C. §4202(a)), delegated authority to proclaim limited tariff reductions without further congressional action.30 The limits on Section 103(a) authority primarily relate to the amount and staging of the reduction in duty rates (see "U.S. Tariff and Quota Commitments").

Prior to the Trump Administration, the United States negotiated FTAs that removed virtually all tariffs between the parties and covered a broad range of trade-related rules and disciplines in one comprehensive negotiation. Nontariff issues often require implementing legislation by Congress to take effect, and Congress has typically considered implementing legislation for past U.S. FTAs under TPA's expedited procedures. The Trump Administration, however, plans to put the limited, stage one agreements with Japan into effect without congressional approval. The Administration intends to use delegated authorities pursuant to Section 103(a) of TPA to proclaim the tariff changes included in the USJTA, while the U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement does not appear to require changes to U.S. law and is being treated as an Executive Agreement.31 Some observers and Members of Congress have questioned whether Section 103(a) authorizes the President to also establish rules of origin and modify import quotas, which are components of the U.S. market access tariff commitments in the USJTA.32

The language of Section 103(a) proclamation authority originated in the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934, when tariff barriers were the primary focus of trade agreement negotiations. Similar language has been included in subsequent iterations of the TPA statue, including the current TPA-2015, which is effective through July 1, 2021. Past U.S. Administrations have invoked Section 103(a) and its past iterations to modify U.S. tariffs and implement agreements addressing tariff barriers. Most recently, in 2015 President Barack Obama invoked this authority to implement an agreement among members of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum to reduce duties on environmental goods.33

Agreement Provisions

The two agreements included in the "stage one" U.S.-Japan trade deal cover tariff and quota commitments on industrial and agricultural goods and commitments on digital trade. The limited coverage and composition represents a significant departure from recent U.S. trade agreements, which typically are comprehensive and cover additional issues such as customs procedures, government procurement, labor and environment protections, intellectual property rights (IPR), services, and investment.34

Notably, neither agreement includes a formal dispute settlement mechanism to enforce commitments should either side take fault with the other's implementation.35 The Trump Administration points to Article 6 of the USJTA, which lays out a 60-day consultation process for resolving issues relating to "the operation or interpretation" of the agreement as a means to resolve disputes relating to tariffs and quota commitments.36 A future comprehensive deal could include a formal dispute settlement mechanism, but it is unclear how this would affect the initial agreements.

U.S.-Japan Trade Agreement (Tariff and Quota Commitments)

The USJTA, which covers tariff and quota commitments, is four pages in length and includes eleven articles governing the operation of the agreement.37 Two separate annexes include the specific tariff reduction schedules for the United States and Japan. The annexes also include staging categories, which lay out the timeline for tariff reductions, and rules of origin, which specify the conditions under which imports are considered to originate from each country and therefore are eligible for the preferential tariff treatment. In total, the agreement is to reduce or eliminate tariffs on approximately $14.4 billion or 5% of bilateral trade ($7.2 billion each of U.S. imports and exports, Figure 3). The agreement also includes provisions providing for amendment and termination procedures (Article 8 and Article 10, respectively).

While the Trump Administration has stated that the USJTA should "enable American [agricultural] producers to compete more effectively with countries that currently have preferential tariffs in the Japanese market,"38 the U.S.-Japan agreement is narrower in scope than either TPP-11 or the EU-Japan FTA. In particular, because of the legal authority under which the United States negotiated the USJTA, the agricultural provisions address only tariffs and quotas, while TPP-11 and the EU-Japan FTA also address many other policies that may interfere with trade in agricultural products. As a result, U.S. agricultural exporters may continue to be at some disadvantage in the Japanese market against those from the TPP-11 countries or the EU. Lack of legal text on non-market-access provisions, such as agricultural biotechnology, geographical indications, sanitary and phytosanitary measures, and technical barriers to trade (TBT) in the USJTA may limit the United States' ability to challenge potential future trade barriers in Japan (and vice versa) related to these issues, for example, if Japan were to align its requirements for agricultural imports more closely with those of the EU or of TPP-11 countries.39

|

A Note on U.S. and Japanese Tariffs U.S. and Japanese tariff commitments are a key component of the stage one bilateral trade agreements. The degree to which negotiated tariff reductions may affect bilateral trade patterns depends in large part on each country's existing most-favored nation (MFN) tariff rates—the non-preferential rates that currently apply to U.S. and Japanese imports from other WTO members—and existing trade patterns. Notably, some U.S.-Japan trade already enters each other's respective markets duty-free. Both the United States and Japan have relatively low average MFN tariffs with zero MFN tariffs on a large number of industrial goods, but both countries, and particularly Japan, have higher average MFN tariffs on agricultural products. According to the WTO's tariff profiles, simple average MFN tariff rates were 4.4% in Japan in 2018 (15.7% for agricultural goods and 2.5% for non-agricultural goods), and 3.4% in the United States (5.3% for agricultural goods and 3.1% for non-agricultural goods). These variations in agricultural and non-agricultural tariffs are even more important when considering existing trade flows. U.S. non-agricultural exports to Japan are concentrated in products with zero MFN duties. According to the WTO, in 2017, Japan's trade-weighted average MFN tariff on non-agricultural imports from the United States was 0.6%, with 86% of such imports from the United States by value entering duty-free. Meanwhile, Japan's trade-weighted average MFN tariff on agricultural imports from the United States was 27.5%, with 33.7% of such imports entering duty-free. For Japan's exports to the United States, the differences in duty rates between agricultural and non-agricultural products are less pronounced with U.S. trade-weighted average MFN tariffs on imports from Japan of 1.5% for non-agricultural products (with 38.4% of such imports entering duty-free) and 3% for agricultural goods (with 29.9% of such imports entering duty-free). This analysis suggests that while the USJTA tariff commitments are to affect a relatively small number of tariff lines (as discussed below), they may have a larger effect on U.S. exports to Japan than would otherwise be expected, given that Japan's tariff commitments are on agricultural products, which are the U.S. export categories facing the highest existing MFN duty rates. Source: WTO Tariff Profiles for Japan and the United States, 2019, at https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/daily_update_e/tariff_profiles/JP_e.pdf and https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/daily_update_e/tariff_profiles/US_e.pdf. |

U.S. Tariff and Quota Commitments

The USJTA tariff schedule commits the United States to reduce or eliminate tariffs on 241 tariff lines that accounted for $7.2 billion of U.S. imports from Japan in 2018 (about 5% of total U.S. goods imports from Japan).40 Per requirements under TPA's tariff proclamation authorities, which as discussed, the Administration intends to use to implement the agreement, U.S. products slated for tariff elimination must have less than a 5% current U.S. most-favored nation (MFN) tariff rate.41 The authority allows for the Administration to reduce tariffs by 50% for products with current MFN tariff rates above 5%. According to the USJTA tariff schedule, the United States is to eliminate tariffs on 169 of covered U.S. tariff lines, while the remaining 72 are to be reduced to 50% of their current MFN rate.42

Unlike the former TPP, which committed the United States to eliminate tariffs on 99% of U.S. tariff lines, the USJTA agreement is to affect a relatively small share of U.S. imports from Japan, both because it covers fewer products and does not include autos and auto parts, the largest single U.S. import category. The U.S. tariff schedule of the USJTA states that auto and auto parts "will be subject to further negotiations with respect to the elimination of customs duties."43 Under TPP, by contrast, the United States committed to eliminate its 2.5% car tariff over 25 years and its 25% light truck tariff over 30 years.

Most of the U.S. products covered in the agreement are industrial goods. Select tariff lines from 30 different U.S. Harmonized Schedule (HS) chapters or categories are included. However, roughly half of the covered products, both in terms of the number of tariff lines and U.S. import value, are from three chapters: machinery (U.S. imports of $3.3 billion in 2018), electrical machinery ($771 million), and tools ($683 million). Other product categories include optical/medical equipment ($534 million), iron and steel articles ($305 million), rubber ($302 million), organic chemicals ($182 million), inorganic chemicals ($182 million), musical instruments ($133 million), copper and articles ($125 million), photographic and cinematographic goods ($118 million), railway ($105 million), and toys ($79 million). The top 10 tariff lines covered by the agreement accounted for $3 billion of U.S. imports in 2018 or 42% of all imports covered (Table 1). U.S. tariffs on these 10 products are to be eliminated either upon entry into force (EIF) of the agreement or at the start of year two.

|

HTS |

Description |

2018 Imports (USD) |

U.S. MFN Tariff |

Staging Category |

||

|

84571000 |

Machining centers for working metal |

$730,727,675 |

4.2% |

Year 2 |

||

|

84581100 |

Horizontal lathes for removing metal, numerically controlled |

$437,823,133 |

4.4% |

Year 2 |

||

|

90021190 |

Objective lenses and parts for cameras, projectors, etc., except projection, nesoi |

$393,322,298 |

2.3% |

EIF |

||

|

84159080 |

Parts for air conditioning machines, nesoi, excluding parts of automotive air conditionersa |

$294,140,207 |

1.4% |

EIF |

||

|

82073060 |

Interchangeable tools for pressing, stamping or punching |

$255,131,757 |

2.9% |

EIF |

||

|

84771090 |

Injection-molding machines of a type used for working products from rubber or plastics, nesoi |

$202,780,063 |

3.1% |

Year 2 |

||

|

84119990 |

Parts of gas turbines nesoi |

$191,425,828 |

2.4% |

EIF |

||

|

38249992 |

Chemical products and preparations, nesoi |

$177,117,422 |

5.0% |

Year 2 |

||

|

84669398 |

Other parts for machines of headings 8456 to 8461, nesoi |

$165,391,111 |

4.7% |

Year 2 |

||

|

82090000 |

Cermet plates, sticks, tips and the like for tools, unmounted |

$161,837,384 |

4.6% |

Year 2 |

||

Sources: Tariff lines and MFN rates from USJTA Annex 2. U.S. imports from U.S. Census Bureau sourced from Global Trade Atlas IHS Markit.

Notes: HTS = Harmonized Tariff Schedule. Nesoi = not elsewhere stated or indicated. MFN = most favored nation. EIF = entry into force.

a. Tariff line only partially covered by U.S. tariff schedule commitments.

The United States also agreed to reduce or eliminate tariffs on 42 agricultural tariff lines on imports from Japan, which include certain perennial plants and cut flowers, persimmons, green tea, chewing gum, certain confectionary products, and soy sauce. In a side letter, the United States agreed to modify its tariff-rate quota (TRQ) for imports of Japanese beef.44 TRQs involve a two-tiered tariff scheme in which imports within an established quota face lower tariff rates, and imports beyond the quota face higher tariff rates. The United States has agreed to eliminate the 200 metric tons (MT) country-specific beef quota for Japan and increase its quota for "other countries or areas" to 65,005 MT. This would enable Japan to ship additional amounts of beef to the United States at low tariff rates under the increased "other countries or areas" quota.

Japan's Tariff and Quota Commitments

Under the USJTA, Japan agreed to eliminate or reduce tariffs for certain U.S. agricultural products and to provide preferential quotas for other U.S. agricultural products. Japan's commitments cover approximately 600 tariff lines, accounting for $7.2 billion of U.S. exports in 2018, according to the USTR.45 Essentially, Japan is providing the same level of market access to the products included in the USJTA as provided to exports from countries that are members of TPP-11. Some products included in TPP-11 such as rice and certain dairy products, however, are not included in the USJTA. According to the USTR, once this agreement is implemented, over 90% of U.S. food and agricultural products exported to Japan will either enter duty-free or receive preferential tariff access.46

When TPP-11 went into effect in December 2018, Japan implemented its first set of tariff cuts and TRQ expansions for TPP-11 countries, and followed these with a second round of tariff cuts and TRQ expansions on April 1, 2019, the start of its new fiscal year. In the USJTA, Japan agreed to accelerate and adjust its TRQ expansion and tariff reduction schedule so that Japan's imports of affected U.S. agricultural products are to receive the same level of market access as imports from TPP-11 countries. This means that tariff rates under the USJTA are to fall slightly faster than those under the TPP-11. For example, under TPP-11, tariffs on beef imports into Japan, previously 38.5%, were reduced to 27.5% in Year 1, to 26.6% in Year 2, and are to reach 9% in Year 16. Under the USJTA, tariffs on Japanese imports of U.S. beef would be reduced to 26.6% in Year 1 and would reach 9% in Year 15.

Key Products and Provisions

- Japan is to reduce tariffs on meat products that collectively accounted for $2.9 billion of U.S. exports to Japan in 2018. Tariffs on processed beef products, including beef jerky and meat extracts, are to be eliminated in 5 to 15 years. Japan's right to raise tariffs if imports of U.S. beef exceed a specified level are to be restricted, and would be eliminated if the specified level is not exceeded47 for four consecutive fiscal years after Year 14.

Tariffs on pork muscle cuts are to be eliminated over 9 years, and tariffs on processed pork products are to go to zero in Year 5. Certain fresh and frozen pork products would continue to be subject to Japan's variable levies when import prices are low, but the maximum variable rate is to be reduced by almost 90% by Year 9.48 As with beef, Japan's right to raise tariffs if imports of U.S. pork exceed a specified level is to be restricted. Japan is to gradually increase the amount of U.S. fresh, chilled, and frozen pork that could be imported annually without triggering additional tariffs, and such tariffs are to be terminated at the end of Year 10. - Japan is to eliminate tariffs immediately upon entry into force of the agreement on selected products, including almonds, walnuts, blueberries, cranberries, sweet corn, grain sorghum, and broccoli, that collectively accounted for $1.3 billion of U.S. exports to Japan in 2018. Tariffs on corn used for feed, the largest U.S. agricultural export to Japan ($2.8 billion or 22% of total U.S. agricultural exports to Japan in 2018), are also to be eliminated upon entry into force of the agreement.49

- Japan is to phase out tariffs in stages for products accounting for $3 billion of U.S. exports in 2018, such as cheeses, processed pork, poultry, beef offal, ethanol, wine, frozen potatoes, oranges, fresh cherries, egg products, and tomato paste.

- Japan agreed to provide country-specific quotas (CSQ) for some products, which provide access to a specified quantity of imports from the United States at a preferential tariff rate, generally zero. The CSQs would provide these products the same access into Japan as would have been accorded if the United States had joined the TPP-11. Products covered by CSQs include wheat, wheat products, malt, processed cheese, glucose, fructose, corn starch, potato starch and inulin. Additionally, Japan agreed to create a single whey CSQ for the United States that would begin at 5,400 MT and grow to 9,000 MT in Year 10. This CSQ combines the provisions of three separate CSQs for whey under the TPP provisions: whey used in infant formula (3,000 MT); whey mineral concentrate (4,000 MT); and whey permeate (2,000 MT).

- Japan agreed to improve access for U.S. skim milk powder by introducing an annual global (WTO) tender for 750 MT of skim milk powder, which would be accessible to the U.S. as well as other WTO-member exporters.50 This is viewed to represent a minor concession, given that the United States exported 713,000 MT of skim milk powder in 2018.51

- Japan agreed to reduce the government-mandated mark-up on imported U.S. wheat and barley, which are controlled by state trading enterprises.52

- Japan agreed to limit the use of safeguard measures to control surges in imports of U.S. whey, oranges, and race horses.

Quota-Specific Issues

According to the USTR, Japan has stated a commitment to "match the [agricultural] tariffs" provided to TPP-11 member countries in USJTA.53 While Japan's tariff schedule under the USJTA attempts to match the TPP-11 schedule, the TRQ schedule falls short of the TPP-11 schedule, potentially disadvantaging market access for some U.S. agricultural products. Under the TPP provisions, Japan had agreed to provide a rice CSQ for the United States, which was to start at 50,000 MT in Year 1 and reach 70,000 MT in Year 13. The U.S.-Japan Trade Agreement does not make provisions for a CSQ for U.S. rice, but Japan has made provisions for a CSQ for Australian rice under the TPP-11. TPP-11 additionally includes provisions for global TRQs for barley and barley products other than malt; butter; skim and other milk powder; cocoa products; evaporated and condensed milk; edible fats and oils; vegetable preparations; coffee, tea and other preparations; chocolate, candies and confectionary; and sugar. No corresponding TRQs are included in the U.S.-Japan agreement.

Japan's simple average MFN tariff on all agricultural imports was 15.7% in 2018, although almost 22% of the Japanese agricultural tariff lines had MFN tariff rates greater than 15%.54 Many of the agricultural products subject to in-quota tariffs are subject to additional mark-ups through the state trading system, making the products more expensive to Japanese consumers. This may tend to suppress imports. For example, 29% of the amount of whey for infant formula that could have been imported under the TRQ was actually imported into Japan in 2017,55 and the corresponding fill rates for skim-milk powder ranged between 25% and 34%.56 Given that many TRQ quotas go unfilled and that over-quota tariff rates are extremely high, there is little trade beyond the set quota levels.

U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement

Digital trade, a growing part of the U.S. and global economy, is an area in which the United States and Japan have had largely similar goals on addressing the lack of common trade rules and disciplines.57 Digital trade entails not only digital products and services delivered over the internet, but is also a means to facilitate economic activity and innovation, as companies across sectors increasingly rely on digital technologies to reach new markets, track global supply chains, and analyze big data.58 The USTR has referred to the U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement, which parallels the proposed U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), as the "most comprehensive and high-standard trade agreement" negotiated on digital trade barriers.59 Provisions of the U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement largely reflect the proposed USMCA, as well as related U.S. negotiating objectives that Congress established under TPA, suggesting the agreement is likely to serve as a template for future U.S. FTAs.60 The agreement has also been cast by the USTR as demonstrating the "continued leading role" of both nations in global rulemaking on digital trade. In this view, U.S.-Japan approaches on rules and standards could set precedents for other ongoing talks, including at the WTO on a potential e-commerce agreement, where conflicting approaches to digital and data issues by other participating members (such as China) have been raised as joint concerns.

Key Provisions and Selected Comparisons

Key commitments of the U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement are highlighted below, with some comparisons to the latest U.S. and Japanese commitments in USMCA and TPP-11, respectively. In USMCA and TPP-11, given the crosscutting nature of digital trade and cross-border data flows, related provisions are covered in multiple FTA chapters beyond digital trade or e-commerce, including financial services, IPR, technical barriers to trade, and telecommunications. Like the USJTA, the U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement includes provisions allowing for potential amendments and possible termination (Article 22).

- Customs duties and nondiscrimination. Commitments prohibit customs duties on products transmitted electronically and discrimination against digital products, including coverage of tax measures.

- Cross-border data flows and data localization. Commitments prohibit restrictions on cross-border data flows, except as necessary for "legitimate public policy objectives." It also prohibits requirements for "localization of computing facilities" (i.e., data localization) as a condition for conducting business.61 Financial service providers are covered under the rules on data localization, as long as financial regulators have access to information for regulatory and supervisory purposes. This approach is distinct from Japan's commitments under TPP-11, which excludes financial services, but is similar to U.S. commitments under USMCA.

- Consumer protection and privacy. Commitments require parties to adopt or maintain online consumer protection laws, as well as a legal framework on privacy to protect personal information of users of digital trade. The content and enforcement of these laws are left to each government's discretion, while encouraging development of mechanisms to promote interoperability between different regimes. Unlike USMCA, there is no explicit reference to take into account guidelines of relevant international bodies' privacy frameworks, such as the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum or the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). However, both the United States and Japan have endorsed and participate in the APEC Cross-Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) system.62

- Source code and technology transfer. Commitments prohibit requiring the transfer or disclosure of software source code or algorithms expressed in source code as a condition for market access, with some exceptions. By comparison, under TPP-11 algorithms are not covered.

- Liability for interactive computer services. Commitments limit imposing civil liability with respect to third-party content for internet platforms that depend on interaction with users, with some exclusions such as for intellectual property rights infringement.63 This rule reflects provisions of the U.S. Communications Decency Act, which has raised concerns for some Members of Congress and civil society organizations about inclusion in U.S. FTAs, amid ongoing debate about the provisions' merits and possible revision to the law in the future.64

- Cybersecurity. Commitments promote collaboration on cybersecurity and use of risk-based strategies and consensus-based standards over prescriptive regulation in dealing with cybersecurity risks and events.

- Open government data. Commitments promote publication of and access to government data in machine-readable and open format for public usage.

- Cryptography. Commitments prohibit requiring the transfer or access to proprietary information, including a particular technology or production process, by manufacturers or suppliers of information and communication technology (ICT) goods that use cryptography, as a condition for market access, with some exceptions, such as for networks and devices owned, controlled, or used by government.

Views and Next Steps

U.S. Views

In general, the stage one agreements have been well received by several Members of Congress and U.S. stakeholders for the expected benefits to agriculture and cross-border digital trade. At the same time, many observers also contend the deals should not be a substitute for a comprehensive agreement and view the second stage of talks as critical to U.S. interests. The U.S. Trade Advisory Committee Report to the USTR and Congress reflects a range of views from among the various committees represented.65 The private sector Advisory Committee for Trade Policy and Negotiations (ACTPN) expressed support for the initial deals and the "significant boost to the U.S. economy that will result from implementation," while urging immediate negotiation of a comprehensive agreement and recommending several priorities for the talks.66 The Intergovernmental Policy Advisory Committee (IGPAC), which is composed of representatives from state and local governments, however, argued that the agreement did not meet most negotiating objectives under TPA, due to its "narrow nature."67 In the view of the Labor Advisory Committee, the deal is a "lopsided agreement designed to address short-term political objectives."68 Various industry committees issued reports outlining priorities for future talks. Some cited what they viewed as the USTR's lack of consultation and the lack of dispute settlement provisions in the agreements as concerns.

Overall, many observers agree that the USJTA is important for U.S. agriculture to regain competitiveness in the Japanese market. At the same time, some raise concerns about product exclusions and the lack of provisions on nontariff barriers that were generally covered in past U.S. FTAs. One trade policy expert cautioned against the tariff-only approach as a model for future U.S. agreements.69 Given this concern, U.S. businesses have strongly advocated for continued progress toward a more comprehensive agreement.70 Other stakeholders question whether there will be sufficient political support in both countries to make progress in future talks, especially during an election year in the United States.71 In particular, since the agriculture sector—among countries' most sensitive markets and thus typically relegated to final stage negotiations—has already secured access, some view the United States as having limited leverage to secure further concessions.72 Other trade experts view the agreement as failing to maximize the potential of the U.S.-Japan economic relationship, both in terms of the market access gains, which essentially had already been agreed to in TPP,73 but also in terms of advancing U.S.-Japan leadership on rulemaking. More broadly, some view successful next-stage talks as also being critical to "engineer an American return to the regional economic architecture."74 Under this outlook, reaching a second-stage comprehensive agreement with Japan could help ease the perception among many East Asian policymakers and scholars that the Trump Administration's Indo-Pacific strategy has an insufficient economic component.75

Japanese Views

While Prime Minister Abe framed the agreement as a "win-win outcome" that benefits both countries,76 some Japanese observers have criticized the agreement as a one-sided deal benefiting the political and economic interests of the United States.77 In particular, critics cite the lack of U.S. market access commitments in the auto sector in exchange for Japanese agricultural concessions, as well as the lack of concrete commitment by the United States not to impose Section 232 auto tariffs, despite verbal assurances from the Trump Administration. Instead, in a joint statement, both sides indirectly alluded to the issue, committing to "refrain from taking measures against the spirit of these agreements … and make efforts for an early solution to other tariff-related issues."78 An estimate by the Japanese government of the economic benefits of a bilateral trade deal assumes the removal of U.S. auto tariffs—an approach criticized by some members of the Japanese Diet, who remain skeptical of achieving this future concession.79 More broadly, some analysts point to Japan conceding to bilateral talks as dimming any prospect for a possible U.S. return to TPP, a long-held Japanese goal. In others' view, the deal was favorable to Japan in achieving the primary goals of avoiding potential auto tariffs and sealing an expeditious conclusion of an agreement limited to goods—Prime Minister Abe's initial characterization of the deal. Further, while Japan made concessions in agriculture, they remain limited to commitments in past Japanese trade agreements (TPP-minus in some cases). Japanese industry broadly welcomes the agreement, in particular the sectors that gain from reduced U.S. tariffs, but like U.S. industry, urge further progress.80

Next Steps

Japan ratified the agreements on December 5, 2019, while the Trump Administration previously signed an executive agreement on the digital trade commitments, and is expected to issue a proclamation implementing the agreed tariff changes in December, paving the way for entry into force in January 2020. In its notification to Congress of the U.S. intent to enter into the agreements, the Administration stated that it "looks forward to continued collaboration with Congress on further negotiations with Japan to achieve a more comprehensive trade agreement."81 The Administration did not specify a timeline, however. The United States and Japan stated their intent to "conclude consultations within four months after the date of entry into force of the United States-Japan Trade Agreement and enter into negotiations thereafter in the areas of customs duties and other restrictions on trade, barriers to trade in services and investment, and other issues in order to promote mutually beneficial, fair, and reciprocal trade."82 While USTR trade negotiating objectives released at the outset of the talks in December 2018 suggested a broad range of issues beyond tariffs and digital trade are to be covered, it remains unclear what specific issues would be the subject of the next-stage talks.

Issues for Congress

The stage one agreements with Japan on agriculture, industrial goods, and digital trade, as well as the approach the Trump Administration has taken to negotiate them represent a significant shift in U.S. trade agreement policy. Given its constitutional authority to regulate foreign commerce, Congress may reflect on whether this shift aligns with congressional objectives. Congress may also consider the impact of the agreements on the U.S. economy, including the implications of completing (or not completing) a broader second-stage deal with Japan, and how a staged approach affects the countries' ability to achieve additional agreements.

Congressional Role in Limited Scope and Staged Agreements

The Administration's plan to implement the stage one U.S.-Japan agreements without the approval of Congress, an unprecedented move for U.S. FTA negotiations, has prompted debate among some Members over the appropriate congressional role. In a November 26, 2019, letter to the USTR some Members sought clarification from the Administration regarding its intent to implement the agreements and how Section 103(a) trade authorities under TPA allow the Administration to enter into a tariff agreement with Japan.83 Some analysts and Members cite uncertainties as to whether the delegated authorities also permit implementation of changes in rules of origin and quota modifications under the agreements. Some Members further suggest that future debate over potential reauthorization of TPA should consider congressional intent behind these delegated tariff authorities.84 At the same time, other Members have indicated that they would not object to the Administration's plan to implement the agreements with Japan without congressional approval.85 On procedure, questions have been raised by some as to whether the Administration has fulfilled the consultation requirements of TPA throughout the negotiations—Section 103(a) includes fewer requirements with respect to tariff-only agreements.86 The digital trade commitments do not appear to require changes to U.S. law, but the inclusion of certain provisions has prompted some congressional debate. In the case of past U.S. FTAs, such debate would typically play out during congressional debate and formal consideration of legislation to implement the respective agreement under TPA. Key questions for Congress may include

- What role should Congress play in limited trade agreements, given the authorities and requirements established in TPA?

- Should Congress consider changes to delegated authorities in future consideration of potential TPA reauthorization?

Staged Negotiation or Comprehensive Deal

Congress set negotiating objectives for U.S. trade agreements in statute in its 2015 grant of TPA (19 U.S.C. §3802). Based on these guidelines and as required by TPA, the Trump Administration laid out 22 specific areas of focus for its bilateral negotiations with Japan.87 The stage one U.S.-Japan trade agreements, however, include provisions related to two of these areas: a limited reduction of tariffs on trade in goods and digital trade. The Administration has stated its intent to address the remaining issues in future negotiations, but its ability to conclude and implement such negotiations depend on the political landscape and will in both countries, making a second-phase deal an uncertain prospect. While the U.S. trade advisory committees generally support the initial-stage agreements, some, such as the services sector advisory committee, also argue that the two-stage or perhaps a multi-stage approach could make it more challenging for the United States to achieve the strongest possible overall outcomes in certain sectors.88

The staged approach also raises questions over the potential economic impact of the agreement. Due to the Administration's intended use of Section 103(a) proclamation authorities to enact the agreed tariff changes with Japan, an economic assessment by the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) will not be required for this stage one deal. The agreement may have a modest overall effect on the U.S. economy, given that it covers a small share of bilateral trade, but it could be significant for the U.S. agricultural exporters that will enjoy improved access to Japan's highly protected market. Key questions for Congress may include

- How do these stage one agreements with Japan affect the ability of the United States to negotiate a more comprehensive agreement in the future?

- Do staged trade negotiations adhere to Congress's negotiating objectives in TPA, and should Congress support this staged approach in future U.S. trade negotiations?

Section 232 Auto Tariff Threat

Congress delegated authority to the President to enact tariffs under Section 232 specifically to address possible threats to U.S. national security. President Trump, however, has stated that his use of tariff authorities have been a critical tool in getting U.S. trade partners to the negotiating table,89 and Japan's Foreign Minister, Toshimitsu Motegi, who negotiated the phase-one deal for Japan, highlighted the importance of avoiding Section 232 auto tariffs as a key outcome of the U.S.-Japan negotiations.90 The Administration has yet to publish the Commerce Department's report outlining the national security threat posed by auto imports, despite direct requests from Congress and legal requirement to do so.91 Some trade analysts caution that U.S. use or threat of trade barriers as negotiating leverage undermines existing global trade rules and could set a precedent used by other countries against the United States in the future.92 Many Members of Congress have questioned the security rationale behind the President's proposed and implemented tariff actions, and some support legislation revising Section 232 authorities.93 Key questions for Congress may include

- Does the use of Section 232 tariff authorities as leverage in broader trade and tariff negotiations represent an appropriate use of the delegated authorities?

- What are the potential long-term implications to U.S. and global trade policy of using the threat of tariff increases as leverage in trade liberalization negotiations?

WTO Compliance

The limited scope of the USJTA commitments (in particular, the exclusion of auto trade), has led several analysts and some Members of Congress to question the extent to which the agreement adheres to Article XXIV of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) under the WTO.94 This provision requires regional trade agreements outside the WTO to eliminate duties and other restrictive regulations of commerce on "substantially all trade" between the parties.95 As discussed, U.S. market access commitments in the initial deal cover a limited share of U.S. goods imports from Japan. Congress has historically taken issue with other countries' partial scope agreements, advocating for better adherence to Article XXIV, including within TPA and other trade statutes.96 Some analysts suggest this concern could be mitigated if the stage one U.S.-Japan agreement were to qualify as an "interim agreement" under Article XXIV; but these agreements must include a "plan and schedule" for the formation of the free trade area within a "reasonable length of time."97 In practice, however, WTO members have rarely challenged other trading partners' agreements for consistency with these requirements under formal dispute settlement proceedings.98 Whether or not the agreement ultimately is inconsistent with the letter or spirit of WTO rules likely depends on the timeline and scope of the next-stage U.S.-Japan talks, which both sides have indicated aim to be comprehensive in scope. Key questions for Congress may include

- Are the stage one agreements consistent with U.S. obligations under the WTO?

- Does the limited scope of the agreements set precedents for other countries to negotiate other partial trade agreements that liberalize trade on a limited set of products or sectors that could potentially discriminate against the United States, as well as potentially undermine respect and adherence to the letter and spirit of WTO rules?

Comparison to TPP (and TPP-11) and Strategic Considerations

The Trump Administration's bilateral trade agreement negotiations with Japan represent an alternative to the U.S.-Japan trade agreement negotiated as part of TPP. Given the Trump Administration's decision to conclude a limited, stage one agreement, the most significant distinction with TPP (and TPP-11) at this point is that TPP covered a much broader range of commitments. For example, USJTA commits the countries to reduce or eliminate tariffs on small share of each country's overall tariff lines, whereas TPP committed both countries to eliminate tariffs on all but a limited number of agricultural products.99 In addition, this phase-one agreement with Japan includes one nontariff issue, digital trade, whereas TPP covered issues such as rules on technical barriers to trade, sanitary and phytosanitary measures, state-owned enterprises, labor and environmental standards, investment and intellectual property rights protections, and market access for services, among others. As discussed, whether the Administration will include such commitments in future negotiations with Japan—and in what form—remains to be seen.100

The Trump Administration's bilateral approach to negotiations with Japan also differs from the Obama Administration's and the George W. Bush Administration's multiparty approach to TPP, which may be tied to differing strategic priorities by the Administrations. For example, the Obama Administration saw the TPP as the economic component of its rebalance to Asia and a vehicle to establish rules that reflect U.S. interests and values as the regional framework for commerce, rather than allowing other countries, such as China, to set regional norms.101 The broad membership of TPP, arguably, was an important component of this strategy, creating an opportunity to harmonize rules across multiple trading partners, and creating a greater likelihood of attracting additional future participants.102 The Trump Administration, alternatively, has prioritized achieving fair and reciprocal trade, both in its objectives for the U.S.-Japan trade agreement and its broader Indo-Pacific strategy.103 The Administration argues that a bilateral approach to negotiations allows the United States to take full advantage of its economic heft to secure the most advantageous terms and allows for better enforceability.104 Key questions for Congress may include

- How has the U.S. withdrawal from TPP affected U.S. economic and strategic interests in Japan and the Asia-Pacific region and what is the best approach to advancing those interests moving forward in the next stage of talks with Japan?

- What are the costs and benefits of bilateral versus regional or multiparty approaches to U.S. trade agreement negotiations?

- Should the United States consider joining TPP-11?

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

U.S. Trade Representative (USTR), "U.S.-Japan Trade Agreement Text," https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/japan-korea-apec/japan/us-japan-trade-agreement-negotiations; USTR, "U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement Text," https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/japan-korea-apec/japan/us-japan-trade-agreement-negotiations/us-japan-digital-trade-agreement-text. |

| 2. |

White House, "Joint Statement of the United States and Japan," September 28, 2018, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/joint-statement-united-states-japan/. |

| 3. |

USTR, "United States-Japan Trade Agreement (USJTA) Negotiations: Summary of Specific Negotiating Objectives," December 2018, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/2018.12.21_Summary_of_U.S.-Japan_Negotiating_Objectives.pdf. |

| 4. |

See CRS In Focus IF10000, TPP: Overview and Current Status, by Brock R. Williams and Ian F. Fergusson. |

| 5. |

In addition to trade talks with Japan, the Trump Administration has negotiated minor revisions to the U.S. Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with South Korea (KORUS), which it implemented through proclamation. It negotiated more substantive revisions to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Canada and Mexico, which require implementing legislation from Congress to take effect. For more, see CRS In Focus IF10733, U.S.-South Korea (KORUS) FTA, coordinated by Brock R. Williams, and CRS In Focus IF10997, Proposed U.S.-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) Trade Agreement, by M. Angeles Villarreal and Ian F. Fergusson. |

| 6. |

Data from U.S. Census Bureau, "U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services (FT900)," 2018 Annual Revision, at https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/Press-Release/2018pr/final_revisions/index.html. |

| 7. |

In 2018, Japan's gross domestic product (GDP) accounted for 85% of the GDP of the five TPP countries without an existing U.S. FTA. Malaysia and Vietnam represent major growth markets in the region, however, with average GDP growth rates over 5% since 2010, compared to 1.4% on average in Japan. |

| 8. |

Robert Lighthizer, "Questions for the Record for Ambassador Robert Lighthizer," Senate Committee on Finance, The President's 2019 Trade Policy Agenda hearing, 116th Cong., 2nd sess., June 18, 2019, p. 10, at https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/SFC%20Hearing%206-18-2019%20QFR%20Responses%20FINAL.pdf. |

| 9. |

Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership text and resources, February 21, 2018, https://www.mfat.govt.nz/en/trade/free-trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements-in-force/cptpp/comprehensive-and-progressive-agreement-for-trans-pacific-partnership-text-and-resources/. |

| 10. |

European Commission, "EU-Japan Trade Agreement Enters into Force," January 31, 2019, http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/press/index.cfm?id=1976. For more detail, see CRS In Focus IF11099, EU-Japan FTA: Implications for U.S. Trade Policy, by Cathleen D. Cimino-Isaacs. |

| 11. |

For more, see CRS Insight IN11200, The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership: Status and Recent Developments, by Cathleen D. Cimino-Isaacs and Michael D. Sutherland. |

| 12. |

"Despite TPP Agreement, Japan Under Pressure to Make Free Trade Deal with U.S.," Japan Times, November 12, 2017. |

| 13. |

See CRS Report RL33436, Japan-U.S. Relations: Issues for Congress, coordinated by Emma Chanlett-Avery; Lara Seligman and Robbie Gramer, "Trump Asks Tokyo to Quadruple Payments for U.S. Troops in Japan," Foreign Policy, November 15, 2019. |

| 14. |

Matthew P. Goodman, "Scoring the Trump-Abe Trade Deal," CSIS Commentary, October 1, 2019. |

| 15. |

U.S. trade and investment figures from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) country fact sheet on Japan, at https://apps.bea.gov/international/factsheet/. |

| 16. |

Data from Japan Ministry of Finance, accessed through Global Trade Atlas IHS Markit. |

| 17. |

For more information on Japanese trade barriers, see USTR, 2019 National Trade Estimate on Foreign Trade Barriers, March 2019, pp. 279-294. |

| 18. |

U.S. Census Bureau trade data, accessed via the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS), September 2019, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/default.aspx. U.S. export statistics discussed in this section use the USDA definition of agriculture. |

| 19. |

U.S. Census Bureau trade data, accessed via USDA, FAS, Global Agricultural Trade System, on November 1, 2019, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/Gats/ExpressQuery1.aspx. |

| 20. |

Accessed via the Global Trade Atlas, November 1, 2019. |

| 21. |

Japan's non-durum wheat imports from Italy increased 8%, Germany over 50%, and Bulgaria over 1,000%; pork imports from the Netherlands grew 19%, Canada 5%, Mexico 20%, Denmark and Spain 8% each, and Germany almost 15%; beef imports from Canada increased 92%, New Zealand 25% and Mexico 13%. |

| 22. |

BEA, International Transactions, Expanded Detail by Area and Country, https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?ReqID=62&step=1, accessed November 2019. |

| 23. |

Testimony of Josh Nassar, House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Trade, U.S.-Japan Trade Agreements hearing, 116th Cong., 2nd sess., November 20, 2019, at https://waysandmeans.house.gov/legislation/hearings/us-japan-trade-agreements. |

| 24. |

BEA, Foreign Direct Investment in the United States: Data on Activities of Multinational Enterprises, https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/index_MNC.cfm, accessed November 2019. |

| 25. |

See CRS In Focus IF10971, Section 232 Auto Investigation, coordinated by Rachel F. Fefer. |

| 26. |

Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association, "Chairman's Comment on the President's Executive Proclamation on the Sec. 232 Automotive Imports Investigation," May 21, 2019, https://www.jama.org/jama-chairman-comment-on-the-232-investigation-proclamation/. |

| 27. |

The 180-day deadline expired on November 14, 2019 without any action by the President, leading some commentators to question whether the President retains the authority to impose such tariffs without conducting a new investigation. David Lawder "Trump Can No Longer Impose 'Section 232' Auto Tariffs After Missing Deadline: Experts," Reuters, November 19, 2019. |

| 28. |

USTR, "On-The-Record Press Gaggle by Ambassador Lighthizer on the U.S.-Japan Trade Agreement," press release, September 25, 2019. |

| 29. |

The Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015 (TPA-2015), was signed into law on June 29, 2015 (P.L. 114-26). CRS Report R43491, Trade Promotion Authority (TPA): Frequently Asked Questions, by Ian F. Fergusson and Christopher M. Davis. |

| 30. |

Specifically, Section 103(a) broadly authorizes the President to enter into an agreement regarding tariff barriers with a foreign country when "existing duties or other import restrictions … are unduly burdening and restricting the foreign trade of the United States." Section 103(a) requires fewer notification and consultation requirements for tariff-only agreements. |

| 31. |

White House, "Presidential Message to Congress Regarding the Notification of Initiation of United States – Japan Trade Agreement," September 16, 2019, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/presidential-message-congress-regarding-notification-initiation-united-states-japan-trade-agreement/. |

| 32. |

Some members of the House Ways and Means Trade Subcommittee raised these questions in a letter to USTR in November 2019. See "Ways & Means Members Press USTR for Answers on U.S.-Japan Trade Agreement in Letter to Lighthizer," Inside U.S. Trade, November 27, 2019. |

| 33. |

See Presidential Proclamation 9384, "To Modify the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States," 80 Federal Register 81155-81156, December 23, 2015, at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2015-12-29/pdf/2015-32853.pdf. |

| 34. |

For an overview of U.S. trade agreements and their coverage, see CRS Report R45198, U.S. and Global Trade Agreements: Issues for Congress, by Brock R. Williams. |

| 35. |

Typically, U.S. FTAs include specific procedures for resolving disputes, which include the option to establish a dispute settlement panel with possible punitive measures, including the withdrawal of trade concessions (i.e., a return of tariffs to their pre-agreement levels), if the panel finds that a party failed to adhere to agreement provisions. See CRS In Focus IF10645, Dispute Settlement in the WTO and U.S. Trade Agreements, by Ian F. Fergusson. |

| 36. |

"USTR Cites Consultation Process as Primary Enforcement Tool in Japan Deal," Inside U.S. Trade, October 15, 2019. |

| 37. |

USTR, "Trade Agreement between the United States of American and Japan," October 7, 2019, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/agreements/japan/Trade_Agreement_between_the_United_States_and_Japan.pdf. |

| 38. |

USTR, "Fact Sheet: Agriculture‐Related Provisions of the U.S.-Japan Trade Agreement," September 2019, https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/fact-sheets/2019/september/fact-sheet-agriculture%E2%80%90related. |

| 39. |

The United States would be able to seek recourse via the World Trade Organization (WTO) where both the United States and Japan are signatories. |

| 40. |

The agreement's U.S. tariff schedule is included in Annex II, "Tariffs and Tariff-Related Provisions of the United States." Trade data sourced from the U.S. Census Bureau via Global Trade Atlas IHS Markit. U.S. tariff lines are eight-digit classifications in the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (HTSUS). For the complete U.S. tariff schedule and 2019 U.S. MFN tariff rates, see https://dataweb.usitc.gov/tariff/annual. |

| 41. |

In addition, the President is not allowed to reduce the duty rate on any "import sensitive agricultural product" below the rate applicable under the Uruguay Round Agreements or a successor agreement. 19 U.S.C. §4202(a)(3). |

| 42. |

The U.S. tariff commitments include 11 different staging categories, which would phase in all U.S. tariff reductions within 10 years. |

| 43. |

USTR, "U.S.-Japan Trade Agreement: Annex II Tariffs and Tariff-Related Provisions of the United States," p 2. |

| 44. |