Combating Corruption in Latin America: Congressional Considerations

Corruption of public officials in Latin America continues to be a prominent political concern. In the past few years, 11 presidents and former presidents in Latin America have been forced from office, jailed, or are under investigation for corruption. As in previous years, Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index covering 2018 found that the majority of respondents in several Latin American nations believed that corruption was increasing. Several analysts have suggested that heightened awareness of corruption in Latin America may be due to several possible factors: the growing use of social media to reveal violations and mobilize citizens, greater media and investor scrutiny, or, in some cases, judicial and legislative investigations. Moreover, as expectations for good government tend to rise with greater affluence, the expanding middle class in Latin America has sought more integrity from its politicians. U.S. congressional interest in addressing corruption comes at a time of this heightened rejection of corruption in public office across several Latin American and Caribbean countries.

Whether or not the perception that corruption is increasing is accurate, it is nevertheless fueling civil society efforts to combat corrupt behavior and demand greater accountability. Voter discontent and outright indignation has focused on bribery and the economic consequences of official corruption, diminished public services, and the link of public corruption to organized crime and criminal impunity. In some countries, rejection of tainted political parties and leaders from across the spectrum has challenged public confidence in governmental legitimacy. In some cases, condemnation of corruption has helped to usher in populist presidents. For example, a populist of the left won Mexico’s election and of the right Brazil’s in 2018, as winning candidates appealed to end corruption and overcome political paralysis.

The 2017 U.S. National Security Strategy characterizes corruption as a threat to the United States because criminals and terrorists may thrive under governments with rampant corruption. Studies indicate that corruption lowers productivity and mars competitiveness in developing economies. When it is systemic, it can spur migration and reduce GDP measurably.

The U.S. government has used several policy tools to combat corruption. Among them are sanctions (asset blocking and visa restrictions) against leaders and other public officials to punish and deter corrupt practices, and programming and incentives to adopt anti-corruption best practices. The United States has also provided foreign assistance to some countries to promote clean or “good” government goals. U.S. efforts include assistance to strengthen the rule of law and judicial independence, law enforcement training, programs to institutionalize open and transparent public sector procurement and other clean government practices, and efforts to tap private-sector knowledge to combat corruption.

This report examines U.S. strategies to help allies achieve anti-corruption goals, which were once again affirmed at the Summit of the Americas held in Peru in April 2018, with the theme of “Democratic Governance against Corruption.” The case studies in the report explore

Brazil’s collaboration with the U.S. Department of Justice and other international partners to expand investigations and use tools such as plea bargaining to secure convictions;

Mexico’s efforts to strengthen protections for journalists and to protect investigative journalism generally, and mixed efforts to implement comprehensive reforms approved by Mexico’s legislature; and

the experiences of Honduras and Guatemala with multilateral anti-corruption bodies to bolster weak domestic institutions, although leaders investigated by these bodies have tried to shutter them.

Some analysts maintain that U.S. funding for “anti-corruption” programming has been too limited, noting that by some definitions, worldwide spending in recent years has not exceeded $115 million annually. Recent congressional support for anti-corruption efforts includes training of police and justice personnel, backing for the Trump Administration’s use of targeted sanctions, and other efforts to condition assistance. Policy debates have also highlighted the importance of combating corruption related to trade and investment. The 116th Congress may consider the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which would revise the NAFTA trade agreement, and contains a new chapter on anti-corruption measures.

Combating Corruption in Latin America: Congressional Considerations

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Overview

- Background

- Early Anti-corruption Approaches

- The Fight Against Corruption Goes Global

- Corruption Scandals and Popular Response in 2018

- The Economics of Corruption and the Role of the Private Sector

- The Links Between Corruption, Violent Crime, and Impunity

- Corruption as a U.S. Foreign Policy Concern and Anti-corruption Assistance

- Case Studies

- Brazil: Mutual Legal Cooperation

- Mexico: Confronting Endemic Corruption and Weak Institutions

- U.S. Support for Anti-Corruption Efforts in Mexico

- Regional Bodies in Central America: CICIG and MACCIH

- International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala

- Mission to Support the Fight Against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras

- Observations Regarding the Case Studies

- Issues for Congress

- Recent U.S. Anti-Corruption and Rule of Law programs

- Congressional Considerations

Summary

Corruption of public officials in Latin America continues to be a prominent political concern. In the past few years, 11 presidents and former presidents in Latin America have been forced from office, jailed, or are under investigation for corruption. As in previous years, Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index covering 2018 found that the majority of respondents in several Latin American nations believed that corruption was increasing. Several analysts have suggested that heightened awareness of corruption in Latin America may be due to several possible factors: the growing use of social media to reveal violations and mobilize citizens, greater media and investor scrutiny, or, in some cases, judicial and legislative investigations. Moreover, as expectations for good government tend to rise with greater affluence, the expanding middle class in Latin America has sought more integrity from its politicians. U.S. congressional interest in addressing corruption comes at a time of this heightened rejection of corruption in public office across several Latin American and Caribbean countries.

Whether or not the perception that corruption is increasing is accurate, it is nevertheless fueling civil society efforts to combat corrupt behavior and demand greater accountability. Voter discontent and outright indignation has focused on bribery and the economic consequences of official corruption, diminished public services, and the link of public corruption to organized crime and criminal impunity. In some countries, rejection of tainted political parties and leaders from across the spectrum has challenged public confidence in governmental legitimacy. In some cases, condemnation of corruption has helped to usher in populist presidents. For example, a populist of the left won Mexico's election and of the right Brazil's in 2018, as winning candidates appealed to end corruption and overcome political paralysis.

The 2017 U.S. National Security Strategy characterizes corruption as a threat to the United States because criminals and terrorists may thrive under governments with rampant corruption. Studies indicate that corruption lowers productivity and mars competitiveness in developing economies. When it is systemic, it can spur migration and reduce GDP measurably.

The U.S. government has used several policy tools to combat corruption. Among them are sanctions (asset blocking and visa restrictions) against leaders and other public officials to punish and deter corrupt practices, and programming and incentives to adopt anti-corruption best practices. The United States has also provided foreign assistance to some countries to promote clean or "good" government goals. U.S. efforts include assistance to strengthen the rule of law and judicial independence, law enforcement training, programs to institutionalize open and transparent public sector procurement and other clean government practices, and efforts to tap private-sector knowledge to combat corruption.

This report examines U.S. strategies to help allies achieve anti-corruption goals, which were once again affirmed at the Summit of the Americas held in Peru in April 2018, with the theme of "Democratic Governance against Corruption." The case studies in the report explore

- Brazil's collaboration with the U.S. Department of Justice and other international partners to expand investigations and use tools such as plea bargaining to secure convictions;

- Mexico's efforts to strengthen protections for journalists and to protect investigative journalism generally, and mixed efforts to implement comprehensive reforms approved by Mexico's legislature; and

- the experiences of Honduras and Guatemala with multilateral anti-corruption bodies to bolster weak domestic institutions, although leaders investigated by these bodies have tried to shutter them.

Some analysts maintain that U.S. funding for "anti-corruption" programming has been too limited, noting that by some definitions, worldwide spending in recent years has not exceeded $115 million annually. Recent congressional support for anti-corruption efforts includes training of police and justice personnel, backing for the Trump Administration's use of targeted sanctions, and other efforts to condition assistance. Policy debates have also highlighted the importance of combating corruption related to trade and investment. The 116th Congress may consider the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which would revise the NAFTA trade agreement, and contains a new chapter on anti-corruption measures.

Overview

The majority of Latin American and Caribbean countries are functional democracies, but institutional weaknesses and widespread public corruption in many of these countries have undermined effective governance and sparked protest and demands for greater transparency. From a U.S. perspective, widespread corruption in Latin America is a potential threat to regional security, has a symbiotic relationship with violent crime, and can be a stimulus for migration.

This report examines how anti-corruption strategies in U.S. policy and legislation initially evolved from a desire to level the playing field for corporations working in the developing world. At first, U.S. corporations were regulated so they could not bribe or extort to win contracts, and then the focus expanded to helping build more effective institutions and the rule of law in developing countries to ensure more fair, predictable, and transparent systems. The report examines how corruption contributes to wasting public monies, distorting electoral outcomes, and reinforcing criminal structures. Although the fight against corruption is a global effort, this report focuses more closely on U.S. interests in fighting corruption in the region, and how U.S. policy and assistance programs have developed to address that goal. Contemporary anti-corruption efforts in Brazil, Mexico, and Central America are examined as case studies. The report closes with considerations for Congress in conducting its oversight role over U.S. funded anti-corruption efforts in the region and pursuing the policy objective of broadening the rule of law and encouraging good government.

Background

In the wake of numerous scandals, particularly regarding the multi-country scandal involving the Odebrecht corporation,1 corruption has become a searing, top-level concern in many Latin American nations, with implications for U.S. policy. In past decades, public rejection of corruption has risen and then crested and fallen back, sometimes to a tacit toleration of bribery and other corruption as the way of politics. Some critics maintain that corruption is so entrenched that it is now endemic in the region and forms the primary path to political power.2 The number of grand-scale scandals exposed in recent years in the region, such as payoff schemes involving high court justices and top-level officials, has led some voters to conclude that all parties and politicians are corrupt, resulting in presidents and vice presidents being pushed from office and traditional political parties being viewed as corrupt and illegitimate.

Some analysts maintain that chronic corruption diminishes support for democracy and stokes cynicism about the integrity of politics. However, 2018 saw prominent anti-corruption candidates and campaigns win elections across the region, with populist and anti-establishment fervor marking campaigns in Mexico, Brazil, and several other countries. In these contests, leading candidates abandoned traditional parties sullied by corruption allegations. For instance, in Mexico, the decades-long dominance of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI)3—displaced in 2000, but resurgent in 2012—was again swept out in Mexico's July 2018 national elections by the National Regeneration Party, or MORENA, founded four years earlier.4 Throughout the region, winning candidates of the left and the right—as in Mexico and Brazil—embraced anti-establishment platforms that appealed to voter disillusionment with corrupt elites.

In its global perceptions survey, Transparency International (TI) has found that a majority of Latin Americans tend to believe pervasive public corruption exists and is expanding its reach. The sense of widespread corruption may be sparking a civil society rejection of the status quo and a deeper commitment to combat corrupt behavior and demand accountability (see textbox).

|

Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index Transparency International, founded in 1993, is recognized as the first global nongovernmental organization (NGO) with a mission "to stop corruption and promote transparency, accountability and integrity at all levels and across all sectors of society." Its independent national chapters fight corruption and offer some help to corruption victims. Transparency International's Corruption Perception Index (CPI) is a frequently used measure of corruption that assesses citizens' perceptions of corruption. The index provides a worldwide comparison of corruption perceptions and is published annually. In the CPI covering 2016, 2017, and 2018, respondents in most Latin American nations surveyed believed corruption was increasing, and a majority of respondents cited their country's politicians as "mostly corrupt." Transparency International (TI) defines corruption as the use of public resources for private gain. Administrative or petty corruption refers to corrupt practices of lower level officials, such as small-scale bribe solicitation, payroll skimming, expectation of gifts, nepotism, selective enforcement of laws, and compensating absentee employees. These might be seen as everyday efforts to exploit ordinary people and small businesses. Grand corruption refers to corrupt practices involving significant resources and top-level officials, such as receipt of kickbacks for selecting bribe-paying bidders on large concessions or public procurement contracts, embezzlement of public funds, irregularities in political party and campaign finance, maintaining political patronage networks on public payrolls, and reducing prices (discounting) for the sale of public goods and infrastructure. Some observers have portrayed grand corruption as "elite capture by powerful vested interests" [including] capture of "high-level decision makers and politicians," potentially able to undermine democratic processes. This information from the Transparency International's website at https://www.transparency.org/ and Eduardo Engel, Delia Ferreira Rubio, and Daniel Kaufmann et al., Report of the Expert Advisory Group on Anti-Corruption, Transparency, and Integrity in Latin America and the Caribbean, Inter-American Development Bank, IDB Mongraph-677, Washington, DC, November 2018. |

Grand corruption involving top political leaders has touched nearly every part of Latin America, generating a wave of anti-corruption activism. In the past, such demonstrations have proven ephemeral, quickly fading as the systemic nature of the problem has left citizens resigned to the status quo. These anti-corruption campaigns may prove more enduring, however, as civil society organizations are attempting to build on their preliminary successes by pushing for institutional reforms to enhance transparency and accountability throughout the public sector.5

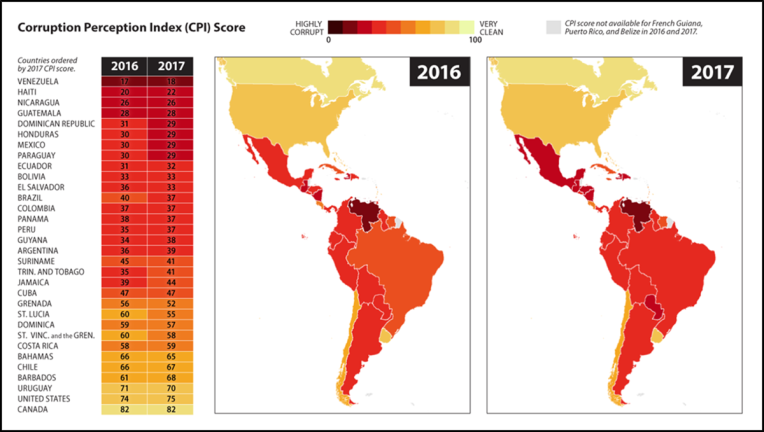

Regarding the relationship of perceptions of corruption as an accurate indicator of actual acts of corruption or prevalence of those acts, TI has in the past married the two. In the 20 Latin American nations polled in the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) for 2016, TI said that respondents identified politicians, political parties, and police as the most corrupt sectors of their societies. The most frequently cited offenses were graft, influence peddling, extortion, bribe solicitation, money laundering, and political finance violations (for 2016 and 2017 CPI results for Latin America and the Caribbean, see Figure 1). One of the 2016 surveys used to establish TI's country rankings asked whether respondents had paid a bribe for a public service over the past 12 months. Nearly one-third confirmed they had paid a bribe to receive a basic public service, such as health care or education.6

Another index, called the World Justice Project's Rule of Law Index (WJP Rule of Law Index), reports that corruption levels vary significantly across the region, although corruption appears to be both widespread and endemic. The Rule of Law Index identifies several indicators for a regional ranking related to governance. At the region's apex and exhibiting the strongest rule of law sit Chile, Costa Rica, and, at the top, Uruguay. The region's least successful on the 2019 Rule of Law Index are Nicaragua, Honduras, Bolivia, and, at the bottom, Venezuela. However, on the indicator of "absence of corruption" alone, the region's worst with regard to the metrics of bribery, improper influence by public or private interests, and misappropriation of public funds, were: Peru, Venezuela, Mexico, and at the bottom, Bolivia. The World Justice Project asserts that full, functioning democracies evolve slowly and anti-corruption programs able to influence and transform the status quo may take years to show results.7

Corruption patterns vary considerably from country to country. Transparency International and other regional surveys, such as the Latinobarómeter, have found the divergence between countries is more pronounced in Latin America and the Caribbean than in other regions. Some commentators argue that lower-level corruption is simpler to identify and root out. More widespread and higher levels of corruption are more difficult to contain and have powerful forces protecting them. For instance, compromised justice systems, apparent in recent scandals in Mexico, Colombia, and Peru, result in impunity for powerful defendants and inhibit the number of successfully completed prosecutions.8 This may result in diminished belief in democratic legitimacy and the rule of law. The confidence or expectation of fairness is replaced with mistrust when bribes are routinely demanded by the police; there is ample evidence of political kickback schemes; and evidence such as recordings shows the suborning of court officials and judges.

In the Western Hemisphere, populist leaders including Nicaragua's Daniel Ortega and Venezuela's Nicolás Maduro have resorted to tactics that undermine democratic institutions like the free press and an independent judiciary, which, when functioning, can help prevent corruption. In Peru, President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski stepped down in March 2018 to avoid impeachment for allegedly taking Odebrecht bribes right before he was to host a Summit of the Americas focused on eradicating corruption. In Mexico and Brazil in 2018, and in El Salvador early in 2019, presidential candidates campaigned successfully against traditional political parties deemed corrupt. In 2018, Mexico's long-dominant Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), was dogged by corruption allegations and performed poorly in congressional and presidential elections.

Political parties are crucial to a competitive democracy, but when they are no longer accountable they lose their primary function of placing a check on the consolidation and abuse of power. Disillusioned and cynical voters who have regularly experienced breaches by their governments, leaders or political parties, can lose trust that is not easily restored. The effort needed to rebuild a country's democratic institutions, such as a functioning justice system, takes patience and political will that is hard to sustain over time. Anti-corruption efforts can face towering political opposition and significant undercurrents that undercut prosecution and future transparency.

The economic costs related to systemic corruption are well researched. In 2018, the costs to Mexico of corruption were estimated to be as high as 5% of the country's GDP and in Peru and Colombia as much as 10%.9 Many analysts contend corruption also exacerbates inequality (a persistent feature of several Latin American and Caribbean societies) which increases instability.10

Many observers have noted the unusual level of activism on anti-corruption reaching nearly every corner of the region in recent years and wondered whether it will endure and produce lasting reform.11 They question whether this current resistance to an existing culture of impunity can be prevented from falling into anti-democratic reaction, or, once again, slipping into resignation.

In the realm of foreign assistance and especially investment, U.S. competitors, including China and to a lesser extent Russia, are using investment in the region, such as infrastructure or energy development projects, not to strengthen recipient governments, but to further their own economic interests. These projects can be beset by hidden costs and have unknown beneficiaries, while they lack public oversight. Greater transparency on bidding and public finance will help give the general public greater capacity to assess them. U.S. programs to strengthen the rule of law and increase governmental transparency may directly benefit recipient nations in Latin America and the Caribbean by extending the institutional foundation for sustained economic development.

|

Figure 1. Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI): Western Hemisphere |

|

|

Sources: "Corruption Perceptions Index 2017", Transparency International, February 21, 2018, https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2017. "Corruption Perceptions Index 2016", Transparency International, January 25, 2017, https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2016. Figure created by CRS. Notes: The corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) ranks countries and territories by their perceived levels of public sector corruption. The index is calculated using different data sources from 11 different institutions that capture perceptions of corruption. For a country or territory to be included in the CPI, a minimum of three sources must assess that country. A country's CPI score is calculated as the average of all standardized scores available for that country. Scores are rounded to whole numbers. In 2016, 176 countries worldwide were included; and, in 2017, 180 countries were included. |

Early Anti-corruption Approaches

U.S. foreign assistance programs to bolster rule of law, encourage good governance, and eliminate bribery, extortion, and graft have been common in Latin America for about three decades. Anti-corruption programming sponsored by the United States and major international financial institutions grew out of ferment in the 1970s, when the long-time practice of businesses and foreign corporations paying bribes to gain contracts in developing countries was exposed (see textbox on Select International Efforts to Combat Corruption). Controlling bribery and payments to foreign governments by businesses became the focus, for the first time, of U.S. legislative reform, the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), in 1977. The law (P.L. 95-213, Title 1) prohibits U.S. corporate bribery of foreign officials. However, this change initially raised concern that the new policy could disadvantage U.S. corporations in comparison to firms from other countries.12

In 1996, the Organization of American States (OAS) adopted the Inter-American Convention Against Corruption (IACAC), the world's first anti-corruption treaty. The IACAC provides OAS member states with a set of legal tools and an institutional framework to prevent, detect, punish, and eradicate corruption. The convention covers criminalization of corruption, international cooperation, asset recovery, and considers preventive roles for business, civil society and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in curtailing corruption. All 34 active OAS member states are party to the IACAC, including the United States, which ratified the convention in 2000 (Treaty Doc. 105-39). The Convention requires signatory states to penalize active and passive corruption, transnational corruption, and improper use of confidential information. However, few high-level public office holders in the region have been brought to justice, especially those who are financially and politically powerful. Signatories' implementation of the IACAC treaty is largely voluntary and relies on sustained political will. (See Appendix B for background on the implementation of IACAC).

In 1997, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), with strong support from the United States, adopted the Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions. Entering into force in 1999 and binding only upon OECD member nations, the Convention on Bribery has actually had a large impact in Latin America, even though only Mexico and Chile at the time were OECD members. Subsequently, Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Costa Rica adopted the measures and other countries changed their laws to begin to conform to the requirements of the 1996 OAS and 1997 OECD conventions.

Some of the innovations from the anti-corruption conventions allowed legislatures in Latin America to sidestep the philosophical question of the capacity of a legal entity (e.g., a corporation) to have a will or intent to commit a crime. With corporations legally capable of committing a crime (such as bribery of local or national officials) then culpability could be assessed. Another method to encourage prevention of corruption was adoption of a "safe harbor" defense for companies, providing them a motive to reform their practices through greater internal corruption safeguards and monitoring.

If a business implemented staunch policies to prevent bribery—such as designating an officer to monitor operations for potential corruption who reports twice a year to the top officer or CEO—then the business could avoid criminal liability, even if individuals inside the corporation were caught in bribery or graft. This policy rewards self-monitoring by offering a buffer from liability as an inducement for self-policing and prevention.

Since the early 1990s, the OAS has convened the Summit of the Americas to address common agenda items in the Western Hemisphere. Both President Barack Obama and President George W. Bush supported initiatives and programs aimed at increasing transparency and accountability in governance to help achieve the overarching U.S. international policy goal of fostering good governance in the region. The Summit convened in April 2018, in Lima, Peru, attended by Vice President Pence rather than President Trump, had the theme of "Democratic Governance against Corruption," echoing a long-term concern with public corruption eroding support for democracy.13

In the past five years, as U.S. enforcement of the FCPA has increased, it has been used to expand the reach of U.S. extraterritorial jurisdiction, as evidenced in support to the Odebrecht case. Several countries are considering a similar statute, or FCPA-like laws to prohibit corporate bribery, including nations as diverse as India, Thailand, and France.14 In addition, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation opened a unit on international corruption in Miami, Florida, in February 2019, with a focus on violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.15

The Fight Against Corruption Goes Global16

Anti-corruption has emerged gradually on the international agenda over recent decades. Factors contributing to its growing prominence as an international policy concern include domestic pressure in many countries to curb political corruption, business risks associated with corruption exposure in a globalized economy, and the undermining impact of official corruption on economic development and foreign aid.17

U.S. advocacy also appears to have played a significant role internationally, although approaches to combating corruption vary widely by country. International standards can provide guidelines and a framework for domestic reform and, critically, mobilize international pressure to enact and implement anti-corruption policies. Due to widespread links between corruption and natural resource exploitation, one prominent area for broadening accountability is in the use of natural resources. Many countries endowed with minerals and resources in demand by more developed economies have sought to put in place voluntary transparency measures and public monitoring of natural resource revenue and expenditure flows to ensure the assets gained will go for public purposes. Transparency measures to prevent resource diversion through corruption and mismanagement have included enactment of broader accountability-focused legal reforms, such as mandatory state budget transparency and accountability measures, freedom of information laws, and the formalization of citizens' participatory rights in state decisionmaking and regulation of extractive industries.

For many countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, extractive resources provide a critical source of government revenue. The textbox below identifies some of the important global anti-corruption efforts, such as the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, which some Latin American countries have adopted.

|

Select International Initiatives to Combat Corruption Numerous global and regional multilateral membership bodies, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), international financial institutions, and multilateral financial institutions, and singular multilateral initiatives address anti-corruption challenges at various levels. Brief information on a selection of these is included below. Selected Civil Society Organizations Many civil society organizations focus on corruption-related issues either globally or at the regional or country level, including within Latin America. A coalition of civil society organizations "committed to promoting the ratification, implementation and monitoring" of the U.N. Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) was established in 2006 and now includes over 350 organizations.18 In addition to TI, prominent examples of other globally focused civil society organizations engaging on this issue include

|

|

Global Anti-Corruption Summit In May 2016, the United Kingdom hosted the Global Anti-Corruption Summit, described as the first of its kind for convening more than 40 foreign governments as well as private sector and NGO representatives toward the goal of combating corruption. Key outcome documents from the summit included a Global Declaration Against Corruption, an Anti-Corruption Summit Communique, and more than 600 individual commitments regarding anti-corruption efforts.19 In September 2017, TI's United Kingdom chapter released a report monitoring progress to date on a selection of the country commitments and found that progress had been made on a majority of them, and 17 percent had been completed.20 Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) EITI aims to establish a "global standard" for transparency and accountability in oil, gas, and minerals management. EITI standards require "the disclosure of information along the extractive industry value chain from the point of extraction, to how revenues make their way through the government, and how they benefit the public." Fifty-one countries are currently implementing the EITI Standard, a set of commitments that signatory governments agree to implement domestically.21 Of note, the United States withdrew from the EITI in November 2017, citing incompatibility with the U.S. legal framework, although under the prior administrations of Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama it had been implemented.22 Open Government Partnership (OGP) In 2011, the United States helped launch OGP with the goal of bringing together governments and civil society to "make governments more inclusive, responsive, and accountable." Participating countries commit to principles of open and transparent government and submit independently monitored action plans. There are currently 79 participating countries, including most countries in Latin America.23 |

|

International Monetary Fund (IMF) Through lending and technical assistance, the IMF helps countries to strengthen their governance and combat corruption. IMF-supported lending may include conditionality tied to strengthening governance, while IMF technical assistance provides guidance on good governance and combating corruption.24 The World Bank The World Bank "considers corruption a major challenge to its twin goals of ending extreme poverty by 2030 and boosting shared prosperity for the poorest 40 percent of people in developing countries." It describes its corruption-related efforts as working "at the country, regional, and global levels to help its clients build capable, transparent, and accountable institutions and design and implement anti-corruption programs relying on the latest discourse and innovations."25 The Bank's global work in this area includes implementation of the Stolen Assets Recovery Initiative (StAR) in partnership with the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). StAR "works with developing countries and financial centers to prevent the laundering of the proceeds of corruption and to facilitate more systematic and timely return of stolen assets."26 |

Corruption Scandals and Popular Response in 2018

Although protests decrying corruption in public office have occurred since 2015 in Brazil, Mexico, and in many countries of Central America, the events of 2018 suggest that corruption prosecutions and revelations during the year significantly increased. As a result, numerous anti-corruption candidates and campaigns played central roles during the 2018 elections, and protests against corrupt leaders erupted in countries throughout the region. (For more details, see the timeline in Appendix C).

Brazil. In Brazil, a sprawling corruption investigation underway since 2014 known as Lavo Jato (Car Wash, in English) implicated much of the political class.27 Brazil's multinational construction firm Odebrecht was one of the firms involved, and, in a landmark plea agreement, admitted to paying millions in bribes to politicians and office holders throughout Latin America. Odebrecht executives, in an agreement with authorities in the United States, Brazil, and Switzerland, admitted to paying some $788 million in bribes to secure public contracts worth more than $3.3 billion. The fallout extended beyond Brazil to countries such as Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Panama, and Peru.28 Both inside Brazil and in other countries, successful prosecution of cases connected to the Odebrecht plea deal received support from the U.S. Department of Justice (see Brazil case study below).

In January 2019, Transparency International endorsed a comprehensive package of 70 reforms developed in conjunction with numerous public and private partners inside Brazil to set the country on a path to restore legitimacy to its political institutions. According to Transparency:

The anti-corruption package includes proposals for institutional reforms, draft bills, constitutional amendments, draft resolutions and other rules to control corruption and tackle its systemic roots. 29

Some of those proposals were incorporated into draft laws that Minister of Justice and Public Security Sérgio Moro presented to the Brazilian Congress in February 2019. Moro presided over the Car Wash investigation as a federal judge prior to being offered the Ministry of Justice and Public Security by President-elect Bolsonaro.30

In Brazil, former President Michel Temer (2016-2018), who was protected from investigation while in office, was arrested on charges of bribery and money laundering in March 2019. According to the Brazilian police, during his vice presidency in 2014 Temer took more than $2 million from Odebrecht to benefit himself and his Brazilian Democratic Movement Party.31 In addition, an array of former high-level government officials in Brazil, such as Aécio Neves, a former senator, governor, and 2014 presidential candidate for the Brazilian Social Democracy Party, face investigations for taking Odebrecht bribes for favorable consideration of legislation preferred by Odebrecht. Former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003-2010) has been sentenced to two 12-year prison terms for steering contracts to Odebrecht and another Brazilian construction firm, OAS, in exchange for renovated properties.

Venezuela. In 2018, an exodus of desperate Venezuelans continued to leave their country, which was under the sway of an authoritarian government that had asserted its power through human rights abuses and significant corruption from drug trafficking and other crimes.32 A May 2018 report by Insight Crime identified more than 120 high-level Venezuelan officials who had engaged in criminal activity.33 In Venezuela, Odebrecht reportedly provided bribes of more than $98 million to President Nicolás Maduro and his government to gain priority treatment. When President Maduro ousted his Attorney General Luisa Ortega, she reported the President solicited a $50 million bribe directly from the Brazilian construction firm. An Odebrecht executive based in Venezuela maintains that the company only paid Maduro $35 million, and other reports state that Odebrecht also sent contributions to Maduro's political opposition.34

The Andean Region

Ecuador. In late 2017, Ecuador's vice president, Jorge Glás, was convicted of taking bribes exceeding $13 million from the Odebrecht firm when he served under former President Rafael Correa (2007-2017). He was removed from office, convicted, and given a seven-year prison sentence, which he is currently serving. Former President Correa, who currently resides in Europe with his Belgian wife, is also wanted by the current government of President Lenín Moreno for arranging the kidnapping of an Ecuadorian official who was a political opponent in 2012. Other charges against Correa include economic mismanagement during his 10-year tenure that involves his ties to Odebrecht.35

Colombia. High-level corruption networks have been exposed since March 2018, when Colombia's Supreme Court sentenced the country's top anti-corruption official, Luis Gustavo Moreno, to four years in prison for corruption. An investigation by Colombia's Attorney General's office found a corruption network pervading the national justice system involving high court justices receiving bribes from influential defendants. In late 2018, Colombia's current Attorney General, Néstor Humberto Martínez, was linked to Odebrecht bribes when he served as legal counsel to the Aval Group, a New York Stock Exchange-listed conglomerate run by the Colombia's wealthiest individual.36 In May 2019, Martínez announced his resignation but for an unrelated matter.37 Odebrecht executives admitted in their guilty plea that they had provided $32.5 million in bribes to facilitate the building of Colombia's Ruta del Sol highway and other infrastructure projects. A Colombian senator, who had accepted some bribes, cooperated in the prosecution to further expose the scheme. It ensnared a number of important Colombian officials in the previous administrations of President Juan Manuel Santos (2010-2018) and President Álvaro Uribe (2002-2010). A former governor, Sergio Fajardo, and a left-centrist presidential candidate, dedicated his 2018 presidential campaign to combating corruption, which became the impetus for a popular referendum promoting anti-corruption, promoted by the candidate who ran as Fajardo's vice president.38

Peru. The Odebrecht campaign-finance and bribery scandals upset political relations nowhere more than in Peru. Several high-profile political figures continue to be under investigation. Four former presidents of Peru are linked to the Odebrecht scandal and other corruption charges. President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (2016-2018) stepped down in March 2018 to avoid impeachment, but may continue to be held in preventive detention for up to three years.39 The Public Ministry opened an investigation into Kuczynski's alleged involvement in buying votes to avoid impeachment as well as his ties to bribery by the Brazilian construction firm. Former president Ollanta Humala (2011-2016) and first lady Nadine Heredia, while released from pretrial detention, are under investigation for money laundering and corruption charges. Peru's government has sought to extradite former president Alejandro Toledo (2001-2006) from the United States for allegedly accepting bribes during his administration. In April 2019, former Peruvian president Alan Garcia (who served from 1985 to 1990 and 2006 to 2011) shot himself during his arrest on Odebrecht-related charges, and died shortly afterwards. His private secretary and other officials in his administrations are being closely investigated for allegedly taking bribes from Odebrecht.40

In October 2018, a judge ordered former presidential candidate and congressional leader Keiko Fujimori to pretrial detention for allegedly laundering illegal campaign contributions from Odebrecht. In his government's fiscal year 2019 budget, Peruvian President Vizcarra expanded funding to the judiciary by 11% to develop additional mechanisms to combat corruption.

Referenda in the Andes. Voters in three Andean nations considered anti-corruption measures in public referenda held in 2018: in Ecuador in February, Colombia in August, and Peru in December. The Ecuador referendum approved all seven measures on the ballot, some of which tackled public corruption. The Colombian referendum, in which more than 11 million voted, was disqualified for not reaching its high voter threshold requirements (it was also the fourth national vote held in 2018). Although requirements for the referendum were not met, the seven measures on Colombia's ballot received high approval levels. New President Iván Duque supported most of the measures, and pledged to introduce some of them in legislation during his four-year term, although none of the measures that the Administration introduced in the first four months of 2019 passed the Colombian Congress. When Peru's President Martín Vizcarra came to office after president Kuczynski resigned in March 2018 he committed to fighting public corruption. The December 10, 2018, referendum in Peru that Vizcarra steered to a vote resulted in a ban on reelection of Members of Congress, a reform of the body that appoints members of the judiciary, and measures to regulate how political parties are financed. The only measure that failed was a controversial proposal to reestablish a bicameral Congress.41

Central America

In 2018, anti-corruption institutions in Guatemala and Honduras faced inhospitable governments opposed to their mission once charges got too close to either themselves, family members, or close political colleagues. The U.N.'s International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), established in 2006, was embraced by President Jimmy Morales when he took office in 2016, but when CICIG began to scrutinize more closely allegations of financing irregularities in his electoral campaign, Morales's government became openly hostile to extending CICIG's mandate.42 In early January 2019, President Morales abruptly ended CICIG's mandate, prematurely disregarding the stated will of the nation's top court and instigating a constitutional standoff (see case study).43 In 2016, the Organization of American States worked with the Honduran government to establish a similar organization, the Mission to Support the Fight against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH). The Honduran government has also sought to undermine MACCIH over the past year.

Dominican Republic.44 In May 2017, the attorney general issued indictments for 14 people, including a cabinet minister (who then resigned) and two senators, on charges of receiving $92 million in bribes from Odebrecht in exchange for construction contracts. The government maintains that the investigation is ongoing, but none of those accused were sentenced to prison, and in June 2018, the attorney general dropped charges against seven of the 14 defendants. Others linked with the Odebrecht scandal include a senator and former public works minister, both of whom belong to the dominant Dominican Liberation Party. Reportedly, resolution of their cases could tarnish the party's image in the run-up to the 2020 national elections.

El Salvador. Former president of El Salvador Mauricio Funes (2009-2014) was found guilty of massive illicit enrichment during his time in office. After fleeing to Nicaragua, he was granted asylum by President Daniel Ortega in 2018. Former Salvadoran president Anthony Saca (2004-2009), Funes's predecessor from a rightwing party, pled guilty to similar charges and was convicted and sentenced to 10 years in prison in El Salvador in September 2018; former first lady Ana Ligia de Saca, announced in April 2019 she has reached a plea deal to avoid prison for her role in laundering $25 million in public money.45

Panama. In Panama, several high-profile politicians have faced charges of illicit financial gains. For example, U.S. court documents contend that Odebrecht reportedly paid more than $59 million in bribe payments in Panama to secure public works contracts between 2010 and 2014.46 In August 2017, Odebrecht agreed to pay the Panamanian government $220 million in fines.47 Former President Ricardo Martinelli (2009-2014) was extradited to Panama from the United States for charges of using public funds to spy on political opponents during his administration. In late 2018, two of Martinelli's sons were arrested in the United States for illegal actions, including accusations of taking Odebrecht bribes. Top members of the Martinelli government are also being investigated for receiving bribes from Odebrecht (e.g., former Minister of the Economy Frank de Lima).48

Mexico. In 2018, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador campaigned successfully for office by attacking corruption and promising to remove corrupt elites. However, how the President will implement his campaign pledges remains unclear. López Obrador was inaugurated in December 2018, and his new Attorney General announced in May 2019 that he planned to prioritize Odebrecht. The former president of the state oil company, Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), Emilio Lozoya Austin, has been accused of a scheme involving ghost companies and bribery by Odebrecht provided to Lozoya to help fund electoral campaigns of the historically dominant Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). In mid-February 2019, López Obrador maintained that the cases against Mexican officials begun under his predecessor, President Enrique Peña Nieto of the PRI party, would have to be re-launched.49

In Mexico, corruption investigations of 20 former state governors, most from the PRI, diminished the party's legacy.50 Following the end of the term of PRI President Enrique Peña Nieto in late 2018, the historic party reportedly is considering changing its name due to its poor showing in legislative and presidential elections. Among the PRI party governors under investigation or in jail in Mexico are former Veracruz Governor Javier Duarte (2010-2016) who was arrested in Guatemala and extradited to Mexico in August 2017. Following his trial in Mexico, he received a nine-year sentence in September 2018. Others are Governor Roberto Borge of Quintana Roo (2010-2016) who is wanted on charges of corruption and abuse of public office; Governor Tomás Yarrington of Tamaulipas state along the U.S.-Mexico border with Texas, who was arrested in Italy and extradited to the United States for U.S. charges of money laundering and other corruption; and former PRI governor Cesar Duarte of the border state of Chihuahua, who fled Mexico and is an international fugitive wanted on a Red Notice by the International Criminal Police Organization, Interpol.

Santiago Narra, the former head of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office for Attention to Electoral Crimes (FEPADE), claims in a book published in January 2019 that the Peña Nieto administration was rife with corruption. According to Narra, governors made common practice of using intimidation and bribery to quash or co-opt dissent.51

Southern Cone

Argentina. In Argentina during 2018 a large scandal surfaced called "the Notebooks." The name comes from notebooks belonging to a former government chauffeur, who allegedly recorded cash payments he ferried to the residence of Presidents Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, who governed Argentina in succession from 2003 to 2015. The kickbacks to the Kirchners were allegedly in exchange for public works contracts approved between 2008 and 2015. The chauffeur's notebooks revealed an alleged bribery scheme totaling $160 million. In August 2018, federal authorities in Argentina arrested 12 former government officials and business executives on corruption-related charges. Fernandez de Kirchner has immunity from arrest as a sitting senator, but she can be prosecuted on the charges.52 Other investigations into public works bribes directly tied to Odebrecht include investigations of Julio de Vido and Daniel Cameron, respectively the minister of planning under both Néstor Kirchner and Fernandez de Kirchner, and the energy secretary in the Fernandez Administration. De Vido allegedly received bribes for road construction tenders in the President's home state of Santa Cruz and other projects. Energy Minister Cameron was allegedly involved in a gas pipeline expansion project that involved taking bribes in cooperation with the Brazilian construction mega-firm.53 In September 2018, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, who may be positioning herself to run again for president, was indicted on bribery charges alleging her involvement in taking some $69 million in bribes.54

Paraguay. Historically Paraguay has been plagued by corruption emerging from a chaotic political history. In the 20th century, the landlocked country experienced a 35-year military dictatorship under General Alfredo Stroessner. Paraguay's legacy of dictatorship included one-party rule that endured until 2008.

President Mario Benito Abdo Benítez, elected in April 2018, was a grandson of a general in the Stroessner cabinet, although he pledged to work toward greater transparency and not return to the days of nepotism and centralized rule.

A grassroots protest movement known as "escraches," started by a disenchanted criminal lawyer in August 2018, has led to some prominent politicians, reportedly from parties across the political spectrum, choosing to resign rather than be humiliated. Youthful supporters say that the focus of these protests is to reduce impunity from the historically weak and unresponsive judicial institutions of the country that require identifying and shaming the accused to push the cases forward. Protest leaders maintain long-unaddressed cases have been taken up and prosecuted with unprecedented speed. However, critics question the ethics of using visible protests at homes of officials (whose homes are picketed and pelted with raw eggs), when these officials are only alleged to be corrupt or to have committed crimes, and some protests have turned violent.55 On April 24, 2019, Paraguay's Comptroller General resigned as it became evident that the Paraguayan senate planned to vote in favor of his impeachment on charges of corruption. The vote to impeach him was reportedly supported by President Abdo Benítez.56

The Economics of Corruption and the Role of the Private Sector

The World Economic Forum (WEF) has identified the inability of weak national institutions to cope with insecurity and prevent and punish corruption as a barrier to investment. According to the WEF's 2017-2018 Global Competitiveness Index, the largest economies in Latin America (Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico) ranked below 100 out of 137 countries in the performance of their institutions. WEF recognizes Brazil for its efforts to use its judiciary to clean up government and punish bribery. On the other hand, El Salvador has received the lowest levels of foreign direct investment (FDI) in Central America over the past decade, with extensive insecurity and corruption cited as the primary reasons.57 Corruption constricts funds that should be available for legitimate socio-economic challenges, such as controlling violence and crime. On the other hand, criminal influence allowed to run rampant engenders instability that negatively affects economic growth. The worst-off victims of corruption tend to be the most marginal and therefore the most vulnerable.

Some analysts maintain that private sector responses to corruption are often reactive rather than proactive and that in some countries businesses are part of the problem. Other analysts maintain that business leaders can be catalysts for demanding clean, non-corrupt governance and can serve as strong advocates for laws to prohibit bribery and extortion to end the distorted impact of corruption on competition. Private sector leaders have supported anti-bribery legislation in several of the more established Latin American democracies. In Mexico, the major business association for small and medium-sized businesses, COPARMEX, is advocating for full implementation of the National Anti-Corruption System, which began under the Peña Nieto government in 2017 (described in the Mexico case study). The business association supports establishing an independent prosecutor's office, one of the key features of the system. On the other hand, business leaders from Guatemala and Honduras have in many cases sought to weaken anti-corruption efforts and controls.

The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) report on anti-corruption, transparency and integrity in Latin America and the Caribbean called for an integrated approach for systemic change to reduce corruption. The report, published in 2018, describes earlier interventions encouraged by multilateral and regional institutions as "uneven and partial." The report points out that the use of corruption indicators by the main rating agencies (Standard & Poor's, Moody's, and Fitch) are critically important for investment and loans available to a recipient country.58

Typically, politicians receive payoffs in exchange for favors to aid their parties or campaigns that ultimately may distort public-works bidding (some for multi-billion dollar infrastructure projects). Levels of outside direct investment are also influenced by perceptions of public corruption. For instance, Chile has had one of the lowest levels of perceived corruption in Latin America, and was quick to correct a perception of increasing corruption when its record was tarnished by scandals between 2015 and 2017. Chile's reputation has helped it achieve both high growth and significant foreign direct investment.59

A Push Factor for Migration?

Many scholars report that corruption affects productivity and lowers competitiveness; when it is systemic, corruption can reduce GDP.60 Public-sector corruption, widespread in many Latin American societies, may handicap Latin American growth, skew incentives, and erode public services. The active involvement of corrupt elites, whether from the private or public sector, may allow criminal networks to remain deeply embedded. Public-sector corruption can be a contributor to migration, since corruption that fosters criminality and corrodes the rule of law may be a factor in Central Americans leaving their countries of origin to migrate to the United States. In addition to economic factors, the growing reach of violent crime into their communities has been cited as an impetus to emigrate. Corruption hinders government efforts to address the factors that cause people to migrate, and undermines public confidence in state institutions.

The Links Between Corruption, Violent Crime, and Impunity61

Many governments in Latin America, particularly those in the Central America-Mexico drug transit zone through which 90% of U.S.-bound cocaine passes, suffer from weak and overwhelmed criminal justice systems. Weak criminal justice systems are unable to investigate and punish crimes and they are easily penetrated by bribery or intimidation. As a result, all manner of criminal behavior may increase, in a self-reinforcing cycle, due to lack of trust in the justice system, failure to invest in fixing the system to bring about improvements, and greater criminal impunity or non-prosecution of crimes. This continues to erode confidence in judicial authorities who are perceived to be "captured" by criminal networks. Lack of confidence in the justice system can affect the morale of criminal-justice personnel and further increase their susceptibility to corruption.

This negative-feedback loop has contributed to Latin America having the highest homicide rate of any region in the world outside a war zone. The linkage between violence and corruption has led Latin Americans to protest the dire situation that they face in their communities, and has been an impetus for their support of anti-corruption campaigns and anti-crime candidates in recent elections. Venezuela, Guatemala, and Honduras, ranked in TI's 2018 Corruption Perceptions Index as highly corrupt by respondents, also registered some of the region's highest homicide rates. Correspondingly, these countries have some of the most-elevated emigration rates in the region, as families facing criminal threats leave rather than rely on security forces that they perceive as corrupt for protection.62

|

Mexico's Search for an Independent Prosecutor General Mexico's attorney general's office (PGR) has been plagued by low budgets, allegations of corruption, inefficiency, and a lack of political will to resolve high-profile cases. Many civil society groups, which advocated for a new criminal justice system, focused their efforts on urging the Mexican congress to create an independent national prosecutor's office to replace the PGR, by implementing a change to the Mexican Constitution made in 2014. Under the new system, the Senate would appoint a respected independent person to lead the new institution. President Andrés Manuel López Obrador downplayed the importance of the new office during his presidential campaign, but Mexico's Congress established the office after he was inaugurated in December 2018. Dr. Alejandro Gertz Manero, a 79-year-old associate of President López Obrador, was named Prosecutor General by the Mexican Senate in January 2019. He will serve a nine-year term, extending beyond the constitutionally mandated six-year term of the President. |

In February 2019, the drug trafficking kingpin Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán who led Mexico's notorious Sinaloa cartel for decades, was convicted in New York on multiple counts of operating a continuing criminal enterprise. The charges included trafficking more than 440,000 pounds of cocaine into the United States, murder, acts of torture, kidnapping, and money laundering. According to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the Sinaloa Cartel has the most extensive reach of any transnational crime group into U.S. cities.

In some of the trial's most incendiary testimony, U.S. government witnesses testified that former senior officials in the Mexican government took bribes from Guzmán; one witness alleged that former president Peña Nieto (2012-2016) received a $100 million bribe from Guzmán.63 The conclusion of the Guzmán trial may do little to diminish the role of corruption generated by drug trafficking, which is entrenched and secured by the enormous profits of the drug trade.

U.S.-supported Mexican efforts to train judicial personnel and judges, establish rule of law programming, and professionalize police and military have had limited sustainable impact, (see Mexico case study below). Most crimes still go unreported because the public believe there is ongoing police collaboration with the criminal networks and/or public officials acquiesce to criminal acts.64 Successful prosecutions are rare, with 8% of every 100 homicide cases resolved, due to poor investigations, corrupt policing, and other inefficiencies.

The effort to build more independence and protect the judiciary from undue political influence in Mexico has focused on establishing a separate attorney general's office. As noted in the textbox, in early 2019 Mexico's Senate appointed Alejandro Gertz Manero to serve a nine-year term in a newly defined attorney general position.65 The appointment has raised concerns that the desired independence may be compromised, as the appointee has a long political association with Mexican President López Obrador. How the President will direct and respond to the newly independent office remains to be seen.66

Conditions that Can Cause Damage and Casualties

Extortion by criminal networks—or by public officials—on an ongoing basis can be significant and corrosive. State resources or public funds to counter violence are diminished if funds are drained by officials stealing public monies. Extortion by criminal networks or officials can reduce funding for essential services like education and healthcare or public works, while artificially raising the cost to citizens for such services. When contracts for major public infrastructure, such as dams, large transportation, or water-supply projects are awarded to the highest briber instead of the lowest priced, qualified bidder, consequences can be deadly. In Peru, in 2017, one criminal group, dubbed by authorities the Imposters of Reconstruction, set up a fake government agency to assist in letting contracts designed to recover from floods and landslides caused by El Niño. The fake agency bilked some 50 to 100 contractors to pay bribes to expedite their bids in the bogus El Niño recovery.67

Oversight of public procurement and transparency requirements may be insufficient to prevent office holders and politicians from using extortion and nepotism to their benefit. Furthermore, government regulatory systems are often thwarted through bribery. The mine-waste dam collapse in January 2019 in Minais Gerais, Brazil, resulted in some 300 deaths. Prosecutors are considering charges of murder and violation of mine safety requirements for the Vale SA employees involved and the German company that signed off on dam inspections for filing false reports. The regulatory body for mines in Brazil had recently approved the dam as low risk, and the inspectors are alleged to have known that the dam was unsafe and at risk of collapse.68

Corruption as a U.S. Foreign Policy Concern and Anti-corruption Assistance

The 2017 U.S. National Security Strategy maintains that corruption of weak governments, especially those cowed by criminals and terrorists, poses a serious national security challenge. It asserts that reducing violence should be a priority in countries that are U.S. trade and security partners because extreme violence is economically and socially disruptive and creates instability. The range of corrupt practices is broad and solutions to control public corruption are quite diverse as the case studies in this report indicate. Police and justice systems are open to corruption when morale and integrity are low and external pressures high, which may allow abusive prosecutorial practices to prevail, such as the use of torture or efforts to destroy or fabricate evidence. Weak rule of law subverts justice systems, and diminishes political systems and participatory democracy.

For several years, U.S. foreign assistance has been provided to fight corruption and enhance the rule of law in Latin America (including judicial training), to improve law-enforcement techniques to conduct investigations, make arrests and properly handle evidence, and enhance oversight of civil society for better accountability. U.S. assistance has supported whistleblower protections and other measures to allow private citizens to be more effective watchdogs of public officials, disrupt abuses, and prevent corruption from taking hold again.

Identifying U.S. partners as tainted by corruption can increase tensions in bilateral relations. As a result, U.S. assistance programs are often identified as efforts to increase the efficiency or integrity of "good government," increase "transparency," and inculcate the rule of law, rather than to combat egregious violations or known violators. Furthermore, anti-establishment and populist governing styles of leaders in Latin America may define their policy ends as anti-corruption, but this may mask other political goals that are more anti-institutional rather than committed to strengthening the nation's institutions.

One example of the U.S. approach is the new proposed trade agreement signed by the United States, Canada, and Mexico in late 2018.69 U.S. trade talks with Mexico and Canada to replace the North Trade Agreement (NAFTA) resulted in the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, (USMCA), which includes a chapter on anti-corruption. The main purpose of the chapter is to "prevent and combat bribery and corruption in international trade and investment." The accomplishment of dedicating a full chapter to reinforce the trilateral commitment to combat corruption is significant, but success would be achieved as the provisions are translated into action. This is especially true in Mexico, where significant gaps remain in implementing anti-corruption regulation.70 Some scholars have identified the various anti-corruption requirements in the chapter as some of the most comprehensive in any trade treaty, though largely drawn from the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement from which the Trump Administration withdrew in 2017. The USCMA chapter includes measures to combat corruption, which are legislative, administrative, and promotional.71

Relevant assistance provided by the U.S. government to combat corruption includes assistance and efforts by U.S. State Department, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the Department of Justice, the Department of the Treasury, and the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), outlined below.

U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), State Department and the Department of Justice72

The U.S. government's primary manager of foreign assistance is USAID and the closely linked U.S. State Department. The two organizations are the main funders of programming for increasing transparency, rule of law, and good government, and often use NGOs to implement their programs. State and USAID program implementers range from associations to local, U.S. embassy, and national civil society groups. Anti-corruption activities are integrated in the strategy of each USAID country mission and embassy, and therefore may influence programs beyond democracy and good governance to include such areas as health, education, economic growth, and promotion of environmental and natural resources management.

In 1994, USAID opened a new Office of Transition Initiatives (OTI) to provide rapid response programming to help support peace and democracy. OTI has assisted NGOs to combat antidemocratic forces and fight corruption or bolster weak institutions by providing more agile U.S. government responses on the ground. Nevertheless, the OTI concentrates on conflict settings rather than governance reform, which often require long-term interventions. The State Department's International Narcotics and Law Enforcement bureau advances the rule of law and human rights by supporting criminal justice institutions in a country, promoting accountability, and helping to strengthen and reinforce the rule of law.

In the last 30 years, USAID and State Department have funded programs to reinforce institutions that tackle corruption and cultivate a "culture of transparency" and integrity. Rule of Law (ROL) programming and judicial and prosecutorial training were part of USAID's 2005 strategy focused on overcoming challenges posed by corruption and targeting agency resources to meet greatest need with more precision. In 2012, with the intention to integrate anti-corruption goals throughout the agency's development portfolio, USAID established the Center of Excellence on Democracy, Human Rights, and Governance. According to one analysis, worldwide programming on combating corruption has totaled roughly 330 projects over seven years (2007 to 2013). About 30 were short-term projects including evaluations, while 289 were long-term country projects.73

Some funds for anti-corruption and justice programs abroad involve transfers from the State Department to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), such as the International Criminal Investigative Training Assistance Program (ICITAP), which is a law enforcement development agency. It works with foreign governments to develop professional and transparent law enforcement institutions that can fend off corruption, lower the threat of transnational crime, counter terrorism, and protect human rights. The 17 ICITAP field offices include three based in Mexico, Panama, and Colombia. The Office of Overseas Prosecutorial Assistance and Training (OPDAT) carries out capacity building in the justice sector, largely by assigning experienced U.S. prosecutors to U.S. Embassies, who provide peer advice and training to host country prosecutors, judges, and other justice sector personnel. They also provide advice on legislation and criminal enforcement policy.

Strategies under the MCC to Combat Corruption

Another avenue of anticorruption assistance to the region is the U.S. Millennium Challenge Corporation, which provides positive incentives for good governance and transparency in its inventory system. The MCC requires countries to pass a "control of corruption" threshold in order to unlock funding such as assistance known as a compact, which on average provides a recipient country with $300 million of U.S. foreign assistance.

Created by Congress in 2004, the MCC was established as an independent assistance agency to award funds to developing nations based on a competitive selection process. A country's performance record is the primary (but not the only) basis for awarding funds; and these criteria include a record of clean and transparent governance when judged in comparison with other nations with similar socio-economic characteristics. Since revising its approach in its 2016 strategy NEXT: A Strategy for MCC's Future, MCC's awards and threshold programs seek to address and promote reforms that support sustainable anti-corruption practices. In the past decade, the region has received several threshold programs (Honduras, Paraguay, and Peru) and two large compacts for El Salvador. The program for Honduras, which the MCC launched in 2005, ended prematurely because of a 2009 coup. Over the past ten years, MCC has awarded roughly $800 million of assistance to countries in the Western Hemisphere in compacts and threshold programs.

Sanctions and the U.S. Treasury Department

U.S. Treasury Department programs, including sanctions, listings, and asset seizures in cooperation with police also address corruption. The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) in Treasury administers and enforces economic sanctions that target foreign entities and persons for their activities related to terrorism, narcotics trafficking, and other threats to the national security, foreign policy, or the economy of the United States. Two of OFAC's sanctions programs address drug trafficking while other programs target terrorist funding. Additionally, 22 individuals and 27 companies from Venezuela are designated as "specially designated narcotics traffickers" under the Kingpin Act.74

In 2015, President Obama issued E.O. 13692 to target those who have undermined democratic processes or institutions, including acts of public corruption, violence or human rights abuses by senior Venezuelan officials. The Trump Administration has imposed sanctions on 74 Venezuelan officials pursuant to E.O. 13692 (in addition to 7 officials sanctioned by President Obama). These officials include President Maduro and his wife, Vice President Delcy Rodriguez, United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) First Vice President Diosdado Cabello, Supreme Court members, and other high level military officials, state governors, and other officials.

In early 2019, the United States applied strong sanctions on Venezuelan oil and the Trump Administration has issued executive orders restricting the government and the ability of Venezuela's state oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PdVSA), to access the U.S. financial system (E.O. 13808), barring U.S. purchases of Venezuela's new digital currency (E.O. 13827), and barring U.S. purchases of Venezuelan debt (E.O. 13835). On November 1, 2018, President Trump signed E.O. 13850, creating a framework to sanction those who operate in Venezuela's gold sector or are deemed complicit in corrupt transactions involving the government. On January 28, pursuant to E.O. 13850, the Administration imposed sanctions on PdVSA to prevent Maduro and his government from benefitting from Venezuela's oil revenue.

The 116th Congress has paid close attention to the turmoil in Venezuela and is likely to continue to consider the steps to influence the Venezuelan government and a return to democratic rule. The humanitarian crisis in the country has caused an exodus of Venezuelans—reportedly the largest outflow of refugees and migrants ever in the Western Hemisphere—which has tested the capacity of receiving countries to respond. For the United States, Europe, and others, the conduit of narcotics through Venezuela has had immediate ill effects. The Maduro government, that is widely considered to be the region's most corrupt, has caused suffering within and beyond Venezuela's borders.75 The effectiveness of sanctions on members of the Maduro government and on the vital oil sector, along with consequences for a destitute and undernourished population, are still to be seen. Should a transition to democracy occur in Venezuela, some observers speculate that what may be revealed would be multi-jurisdictional and massive corruption. It would far exceed the scope of what the State Department identified in a mid-April 2019 fact sheet.76

Case Studies

The following examples highlight the various ways in which the U.S. government has supported recent anti-corruption efforts in Latin America. The selected cases—Brazil, Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras—examine the extent to which U.S. support has contributed to driving anti-corruption efforts in widely divergent legal and historical contexts. The United States in these illustrative cases has sought to work closely with established authorities and civil society actors to combat impunity, increase transparency, and dislodge corruption. In Brazil, the U.S. Justice Department cooperated with Brazilian prosecutors on a complex international bribery and corruption case. In Mexico, the United States has supported rule of law reforms to increase judicial independence, reduce impunity, and protect journalists in the context of a strong central government. In Central America, with its historically weak governments, the multilateral institutions and outside experts worked alongside the justice systems in Guatemala and Honduras to expose corruption and criminal control.

Brazil: Mutual Legal Cooperation77

Over the past five years, Brazilian authorities have carried out a series of overlapping investigations that have uncovered systemic corruption. As noted above, operation Lava Jato ("Car Wash"), launched in March 2014, has implicated high-level politicians from across the political spectrum, as well as many of the country's most prominent business executives. The initial investigation revealed that political appointees at the state-controlled oil company, Petróleo Braileiro S.A. (Petrobras), colluded with construction firms to fix contract bidding processes. The firms then provided kickbacks equivalent to 1-2% of the value of their inflated contracts to Petrobras officials and their politician sponsors in the ruling coalition.78 Subsequent investigations have discovered similar practices throughout the public sector, with businesses providing bribes and illegal campaign donations in exchange for contracts or other favorable government treatment. To date, Brazilian prosecutors have charged more than 900 individuals and secured more than 200 convictions for crimes including corruption, money laundering, and abuse of the international financial system.79 Most of the politicians implicated by the scandals have yet to be convicted, however, since the Supreme Court, which is charged with trying high-ranking public officials, faces a significant case backlog.