Permanent Employment-Based Immigration and the Per-country Ceiling

The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) specifies a complex set of categories and numerical limits for admitting lawful permanent residents (LPRs) to the United States that includes economic priorities among the admission criteria. These priorities are addressed primarily through the employment-based immigration system, which consists of five preference categories. Each preference category has specific eligibility criteria; numerical limits; and, in some cases, distinct application processes. The INA allocates 140,000 visas annually for all five employment-based LPR categories, roughly 12% of the 1.1 million LPRs admitted in FY2017. The INA further limits each immigrant-sending country to an annual maximum of 7% of all employment-based LPR admissions, known as the per-country ceiling, or “cap.”

Prospective employment-based immigrants follow two administrative processing trajectories depending on whether they apply from overseas as “new arrivals” seeking LPR status or from within the United States seeking to adjust to LPR status from a temporary status that they currently possess. While some prospective employment-based immigrants can self-petition, most require U.S. employers to petition on their behalf. In both cases, the Department of State (DOS) is responsible for allocating the correct number of employment-based immigrant “visa numbers” or slots, according to numerical limits and the per-country ceiling specified in the INA.

This report reviews the employment-based immigration process by examining six pools of pending petitions and applications, representing prospective employment-based immigrants and any accompanying family members at different stages of the LPR process. While four of these pools represent administrative processing queues, two result from the INA’s numerical limitations on employment-based immigration and the per-country ceiling.

These latter two pools of foreign nationals, who have been approved as employment-based immigrants but must wait for statutorily limited visa numbers, totaled in excess of 900,000 as of mid-2018. Most originate from India, followed by China and the Philippines.

Some employers maintain that they continue to need skilled foreign workers to remain internationally competitive and to keep their firms in the United States. Proponents of increasing employment-based immigration levels argue that it is vital for economic growth. Opponents cite the lack of compelling evidence of labor shortages and argue that the presence of foreign workers can negatively impact wages and working conditions in the United States.

With this statutory and economic backdrop, the policy option of revising or eliminating the per-country ceiling on employment-based LPRs has been proposed repeatedly in Congress. Some argue that eliminating the per-country ceiling would increase the flow of high-skilled immigrants from countries such as India and China, who are often employed in the U.S. technology sector, without increasing the total annual admission of employment-based LPRs. Currently, nationals from India in particular, and to a lesser extent China and the Philippines, face lengthy queues and inordinately long waits to receive LPR status. Many of those waiting for employment-based LPR status are already employed in the United States on temporary visas, a potentially exploitative situation that some argue incentivizes immigrant-sponsoring employers to continue to recruit foreign nationals primarily from these countries for temporary employment. Others counter that the statutory per-country ceiling restrains the dominance of a handful of employment-based immigrant-sending countries and preserves the diversity of immigrant flows.

Permanent Employment-Based Immigration and the Per-country Ceiling

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Background on Numerical Limits

- The Per-country Ceiling

- Employment-Based Immigration System

- Preference Categories

- Priority Dates

- Petition and Application Processing

- Employment-Based Immigration Trends

- New Arrivals Versus Adjustments of Status

- Pools of Prospective Employment-Based LPRs

- Pending Labor Certification Applications at DOL

- Pending Immigrant Petitions at USCIS

- Pending Approved Visa Applications at DOS

- Pending Approved Adjustment of Status Petitions at USCIS

- Visa Applications Submitted to DOS

- Adjustment of Status Applications Submitted to USCIS

- Caveats on the Data on Pools of Prospective Employment-Based Immigrants

- Should the Per-country Ceiling Be Revised?

- Arguments In Favor

- Arguments Against

- Anticipated Outcomes

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Employment-Based Immigration Preference System

- Table 2. Priority Dates for Employment-Based Immigrants, December 2018

- Table 3. Approved Pending Employment-Based Immigrants at DOS

- Table 4. Approved Pending Employment-Based Immigrant Petitions at USCIS

- Table 5. Approved Pending Employment-Based Immigrant Petitions at USCIS

- Table 6. Employment-Based I-485 (Adjustment of Status) Applications In Process

Summary

The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) specifies a complex set of categories and numerical limits for admitting lawful permanent residents (LPRs) to the United States that includes economic priorities among the admission criteria. These priorities are addressed primarily through the employment-based immigration system, which consists of five preference categories. Each preference category has specific eligibility criteria; numerical limits; and, in some cases, distinct application processes. The INA allocates 140,000 visas annually for all five employment-based LPR categories, roughly 12% of the 1.1 million LPRs admitted in FY2017. The INA further limits each immigrant-sending country to an annual maximum of 7% of all employment-based LPR admissions, known as the per-country ceiling, or "cap."

Prospective employment-based immigrants follow two administrative processing trajectories depending on whether they apply from overseas as "new arrivals" seeking LPR status or from within the United States seeking to adjust to LPR status from a temporary status that they currently possess. While some prospective employment-based immigrants can self-petition, most require U.S. employers to petition on their behalf. In both cases, the Department of State (DOS) is responsible for allocating the correct number of employment-based immigrant "visa numbers" or slots, according to numerical limits and the per-country ceiling specified in the INA.

This report reviews the employment-based immigration process by examining six pools of pending petitions and applications, representing prospective employment-based immigrants and any accompanying family members at different stages of the LPR process. While four of these pools represent administrative processing queues, two result from the INA's numerical limitations on employment-based immigration and the per-country ceiling.

These latter two pools of foreign nationals, who have been approved as employment-based immigrants but must wait for statutorily limited visa numbers, totaled in excess of 900,000 as of mid-2018. Most originate from India, followed by China and the Philippines.

Some employers maintain that they continue to need skilled foreign workers to remain internationally competitive and to keep their firms in the United States. Proponents of increasing employment-based immigration levels argue that it is vital for economic growth. Opponents cite the lack of compelling evidence of labor shortages and argue that the presence of foreign workers can negatively impact wages and working conditions in the United States.

With this statutory and economic backdrop, the policy option of revising or eliminating the per-country ceiling on employment-based LPRs has been proposed repeatedly in Congress. Some argue that eliminating the per-country ceiling would increase the flow of high-skilled immigrants from countries such as India and China, who are often employed in the U.S. technology sector, without increasing the total annual admission of employment-based LPRs. Currently, nationals from India in particular, and to a lesser extent China and the Philippines, face lengthy queues and inordinately long waits to receive LPR status. Many of those waiting for employment-based LPR status are already employed in the United States on temporary visas, a potentially exploitative situation that some argue incentivizes immigrant-sponsoring employers to continue to recruit foreign nationals primarily from these countries for temporary employment. Others counter that the statutory per-country ceiling restrains the dominance of a handful of employment-based immigrant-sending countries and preserves the diversity of immigrant flows.

Introduction

Four major principles currently underlie U.S. policy for admitting lawful permanent residents (LPRs):1 reunifying families, admitting individuals with needed skills, providing humanitarian assistance, and diversifying immigrant flows by country of origin.2 These principles are expressed in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA),3 which contains a pathway for acquiring LPR status for each principle. Family reunification occurs primarily through family-sponsored immigration. Admitting individuals with needed skills occurs through employment-based immigration. Humanitarian assistance occurs primarily through the U.S. refugee and asylum programs. Origin-country diversity occurs primarily through the Diversity Immigrant Visa.

This report focuses on the second LPR pathway noted above, employment-based immigration. Employment-based immigrants enter the United States through one of five preference categories, each with its own eligibility requirements and numerical limitations and, in some cases, different application processes.

In addition to the numerical limits imposed upon each preference category, employment-based immigrants face a per-country ceiling, or "cap," that limits the number of immigrants from any single country of origin to 7% of the annual limit for each of the five preference categories. This limitation was imposed to prevent any one country or handful of countries from dominating the flow of employment-based immigration to the United States.4

The numerical limits imposed upon each preference category, combined with the per-country ceiling, mean that employment-based immigrants from certain countries can face considerable waits before they can acquire LPR status. In recent years, some Members of Congress have shown interest in reassessing the 7% per-country ceiling for employment-based immigration.

Some assert that the current numerical limits on employment-based LPRs are not working in the national economic interest and potentially lead to exploitation of foreign workers who are waiting to acquire LPR status.5 Others argue that such limits prevent a few countries from dominating employment-based immigration.6

The report opens with explanations of the employment-based preference categories and the per-country ceiling governing annual permanent immigration. It then presents trend data on employment-based immigration. Focusing primarily on the five major employment-based preference categories, the report continues by analyzing pending queues of six distinct pools of petitions and applications found across the administrative process of acquiring employment-based LPR status. The report then presents arguments for and against removing the per-country ceiling on employment-based LPRs. It discusses recent congressional proposals to alter the per-country ceiling,7 and considers possible outcomes that might occur as a result of eliminating it.

Background on Numerical Limits

The INA limits worldwide permanent immigration to 675,000 persons annually: 480,000 family-sponsored immigrants, made up of family-sponsored immediate relatives of U.S. citizens (immediate relatives),8 and a set of four ordered family-sponsored preference immigrant categories ("preference immigrants"); 140,000 employment-based immigrants comprised of a set of five preference immigrant categories and 55,000 diversity visa immigrants.9 This worldwide limit, however, is referred to as a "permeable cap" because immediate relatives are exempt from numerical limits placed on family-sponsored immigration and thereby represent the flexible component of the 675,000 worldwide limit.10 Consequently, the actual total of foreign nationals receiving LPR status each year (including immigrants, refugees, and asylees) has averaged roughly 1 million persons during the past decade.11

The Per-country Ceiling

The INA further specifies a "per-country ceiling," or "cap," limiting the number of family-sponsored preference immigrants and the number of employment-based immigrants from any single country to 7% of the limit in each preference category.12 The per-country level is not a "quota" set aside for individual countries, as each country in the world could not receive 7% of the overall limit. The Department of State (DOS) notes that "the country limitation serves to avoid monopolization of virtually all the annual limitation by applicants from only a few countries," and is not "a quota to which any particular country is entitled."13

Employment-Based Immigration System

The INA outlines five distinct employment-based preference categories and their individual numerical limits within the overall worldwide total of lawful permanent residents. How prospective immigrants apply for employment-based LPR status depends on where they reside. They may apply directly from abroad as new immigrant arrivals or from within the United States as "status adjusters." Adjusting status refers to the process of changing from a temporary (nonimmigrant) status (e.g., F-1 student visa, H-1B skilled temporary worker visa) to LPR status.14 In either case, petitioning and application involve multiple steps and federal agencies. While some prospective employment-based immigrants can self-petition, most require U.S. employers to petition on their behalf.15

DOS and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) each play key roles in administering the law and policies on immigrant admission. In addition, petitioners for 2nd and 3rd preference category immigrants must apply for labor certification (described below) from the Department of Labor (DOL). Once any required labor certification is approved, DHS's U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) must adjudicate an immigrant petition.16 If the prospective immigrant resides in the United States, USCIS also processes the application to adjust to LPR status (discussed below). In contrast, if the prospective immigrant resides abroad, they must subsequently apply to DOS's Bureau of Consular Affairs for a visa to travel to the United States.17 DOS is also responsible for the allocation, enumeration, and assignment of all numerically limited "visa numbers" or slots, regardless of where prospective immigrants reside.18

Among prospective immigrants, the INA distinguishes between principal prospective immigrants (principals) who meet the qualifications of the employment-based preference category, and derivative prospective immigrants (derivatives) who include the principals' spouses and children. Derivatives appear on the same petition as principals and are entitled to the same status and order of consideration as long as they are "accompanying" or "following to join" principal immigrants.

Preference Categories

Employment-based LPR status is granted to eligible immigrants in the order in which immigrant petitions have been filed under the specific employment-based preference category for the origin country.19 Visa numbers are prorated according to the preference system allocations (Table 1).

|

Category |

Numerical Limit |

||

|

Employment-Based Preference Immigrants |

(Worldwide Level 140,000) |

||

|

1st preference: |

Priority workers: persons of extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics; outstanding professors and researchers; and certain multinational executives and managers |

28.6% of worldwide limit (40,040) plus unused 4th and 5th preference |

|

|

2nd preference: |

Members of the professions holding advanced degrees or persons of exceptional abilities in the sciences, arts, or business |

28.6% of worldwide limit (40,040) plus unused 1st preference |

|

|

3rd preference: |

Skilled shortage workers with at least two years training or experience; professionals with baccalaureate degrees; and unskilled shortage workers |

28.6% of worldwide limit (40,040) plus unused 1st or 2nd preference; unskilled "other workers" limited to 10,000 |

|

|

4th preference: |

"Special immigrants," including ministers of religion, religious workers, certain employees of the U.S. government abroad, and others |

7.1% of worldwide limit (9,940); religious workers limited to 5,000 |

|

|

5th preference: |

Immigrant investors who invest at least $1 million ($500,000 in rural areas or areas of high unemployment) in a new commercial enterprise that creates at least 10 new jobs |

7.1% of worldwide limit (9,940); 3,000 minimum reserved for investors in rural or high unemployment areas |

|

Source: CRS summary of INA §203(b); 8 U.S.C. §1153(b).

Note: Employment-based allocations are further affected by the Nicaraguan and Central American Relief Act (NACARA, Title II of P.L. 105-100), as amended by §1(e) of P.L. 105-139. NACARA provides immigration benefits and relief from deportation to certain Nicaraguans, Cubans, Salvadorans, Guatemalans, nationals of former Soviet bloc countries, and their dependents who arrived in the United States seeking asylum. Employment-based allocations also are affected by the Chinese Student Protection Act (P.L. 102-404), which requires that the annual limit for China be reduced by 1,000 until such accumulated allotment equals the number of aliens (roughly 54,000) acquiring immigration relief under the act. Consequently, each year, 300 immigrant visas are deducted from the 3rd preference category and 700 from the 5th preference category for China. See U.S. Department of State, Visa Office, Annual Numerical Limits for Fiscal Year 2018.

The INA provides for certain adjustments within the numerical limits imposed for each of the five employment-based preference categories. First, unused visa numbers for each of the preference categories can "roll down" and be used by immigrants applying in the next preference category.20 Second, in any given quarter, if the number of available visa numbers exceeds the number of applicants, then the per-country ceiling does not apply for the remainder of available visa numbers for that quarter.21 Third, any unused family-based preference immigrant visa numbers can be applied to employment-based preference immigrant visa numbers in the next fiscal year.22

Priority Dates

Due to numerical limitations for each preference category, the number of approved immigration petitions for a specific preference category in a given year may exceed visa numbers available for that category as well as the country of origin (due to the 7% per-country ceiling). As a result, individuals with approved petitions may be placed in a queue until a visa is available (see "Pools of Prospective Employment-Based LPRs").

|

Category |

China |

El Salvador, Guatemala, & Honduras |

India |

Mexico |

Philippines |

Vietnam |

All Others |

|

1st Preference: "Priority workers" |

9/1/16 |

7/1/17 |

9/1/16 |

7/1/17 |

7/1/17 |

7/1/17 |

7/1/17 |

|

2nd Preference: "Members of the professions holding advanced degrees or aliens of exceptional ability" |

7/1/15 |

Current |

4/1/09 |

Current |

Current |

Current |

Current |

|

3rd Preference: "Skilled workers, professionals, and other workers" |

6/8/15 or 6/1/07* |

Current |

3/1/09 |

Current |

6/15/17 |

Current |

Current |

|

4th Preference: "Certain special immigrants" |

Current |

2/22/16 |

Current |

1/1/17 |

Current |

Current |

Current |

|

5th Preference: "Employment creation" |

8/22/14 |

Current |

Current |

Current |

Current |

5/1/16 |

Current |

Source: U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, Visa Bulletin for December 2018, "Final Action Dates for Employment-Based Preference Cases."

Notes: *For some preference categories, the Visa Bulletin provides separate priority dates for each subcategory within that category. Because most priority dates are the same for all subcategories within a preference category, Table 2 presents one priority date for the entire preference category. The exception is the 3rd preference category for China, where the Visa Bulletin shows a priority date of June 8, 2015 for those applying as "professional and skilled" workers, and a priority date of June 1, 2007 for those applying as "unskilled" workers.

DOS's Visa Bulletin for December 2018 presents action dates (also known as "cut-off dates") for employment-based preference immigrants (Table 2). If a date appears for any preference category, it indicates that the category is "oversubscribed" and that a numerically limited visa number is available only to prospective employment-based immigrants with priority dates that are on or earlier than that cut-off date. Such prospective employment-based immigrants are eligible to submit their visa application to DOS or their adjustment of status application to USCIS. The term "current" indicates that DOS can issue visa numbers to all qualified applicants in that category regardless of priority date or country of origin.

Usually cut-off dates in the Visa Bulletin advance with time. However, visa number demand by applicants with a variety of priority dates can fluctuate from month to month, invariably affecting cut-off dates. Such fluctuations can cause cut-off date movement to slow or stop. In some cases where visa number demand unexpectedly exceeds supply, DOS may have to regress cut-off dates to earlier dates to maintain an orderly queue, a situation referred to as "visa retrogression." In sum, visa retrogression occurs when more people apply for a visa number in a particular category or country than there are visa numbers available for that month.23

Priority dates shown in the Visa Bulletin are not necessarily an accurate guide for visa applicants to gauge their expected wait times until they can apply for a visa or adjust status. Changes in the rate at which foreign nationals apply for LPR status can alter waiting times substantially. For example, the Visa Bulletin for December 2018 indicates that Indian nationals, whose 2nd preference employment-based petitions (professionals with advanced degrees) were submitted on or before April 1, 2009, could apply for a visa. Indian nationals who were considering applying as employment-based immigrants might interpret this to mean that filing a 2nd preference employment-based immigrant petition in December 2018 would result in an expected wait time of about 9.5 years until they could receive LPR status. However, if more or fewer Indian nationals applied for employment-based LPR status between 2009 and 2018 than those who applied for LPR status during the 9.5 years prior to April 1, 2009, expected wait times for LPR status could be longer or shorter, respectively.

Petition and Application Processing

Before petitioning for 2nd and 3rd preference category workers, employers must first apply for a foreign labor certification from DOL. To grant it, DOL must determine through its foreign labor certification program that (1) there are insufficient able, willing, qualified, and available U.S. workers to perform the work in question; and (2) the employment of foreign workers will not adversely affect the wages and working conditions of similarly employed U.S. workers.24

Following this step, sponsoring employers and self-petitioning individuals must file one of three employment-based immigrant petitions with USCIS: an Immigrant Petition for Alien Workers (USCIS Form I-140) for 1st, 2nd, and 3rd preference categories; a Petition for Amerasian Widow(er), or Special Immigrant (USCIS Form I-360) for the 4th preference category; and an Immigrant Petition by Alien Entrepreneur (USCIS Form I-526) for the 5th preference category.

USCIS sends processed and approved immigrant petitions to DOS's National Visa Center (NVC), which assigns a priority date25 (the petition filing date) that represents the prospective immigrant's place in the visa queue. Individuals must wait for their priority date to "become current" before proceeding.26 Priority dates become "current" when they are earlier than the "final action dates" (often referred to as the "cut-off dates") published for the five numerically limited, employment-based immigrant preference categories in DOS's monthly Visa Bulletin (see Table 2 below). Once a prospective immigrant's priority date becomes current, the next steps taken depend on whether he or she resides abroad or in the United States.

If the prospective immigrant resides abroad, he or she must apply to DOS for a visa to enter the United States with an Application for Immigrant Visa and Alien Registration (DOS Form DS-260). If the prospective immigrant is already residing in the United States, he or she must apply to USCIS to adjust status with an Application to Register Permanent Residence or Adjust Status (USCIS Form I-485).27

The final stage in the employment-based immigration process is an interview with either a DOS consular official for foreign nationals residing abroad or a USCIS adjudicator for foreign nationals residing in the United States.28 If the prospective immigrant is living abroad, the DOS consular office in the applicant's home country will schedule an interview with the prospective immigrant to determine if he or she can receive an immigrant visa to come to the United States and seek admission as an LPR, a pathway known as consular processing.29

Regardless of whether the potential LPR is applying for a visa abroad from a DOS consular office or applying to adjust status with USCIS in the United States, DOS assigns the visa priority dates and allocates the visa numbers.30

Employment-Based Immigration Trends

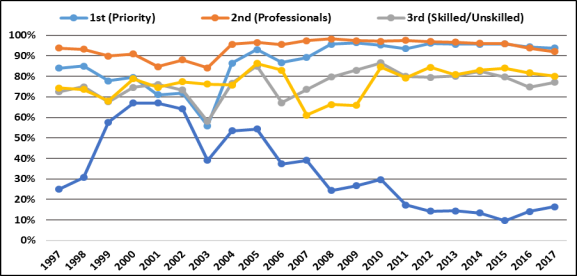

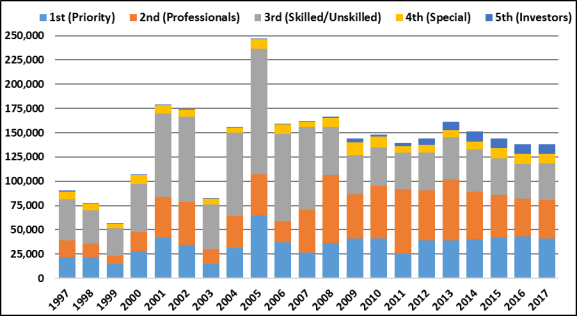

Figure 1 presents the trends in the admission of employment-based immigrants from 1997 to 2017 by preference category.31 Over this period, the total number of employment-based immigrants fluctuated from a low of 56,817 (in 1999) to a peak of 246,877 (in 2005). In FY2017, these 137,855 employment-based immigrants represented 12% of the 1,127,167 foreign nationals who received LPR status.32 The data illustrate that, as noted in Table 1 above, the INA allocates most employment-based LPRs to the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd preference categories.

|

Figure 1. New Employment-Based Immigrants, by Preference Category (FY1997-FY2017) |

|

|

Source: DHS Office of Immigration Statistics, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, Tables 4 and 6, multiple years. |

The 2003 dip and the 2005 spike in employment-based LPRs resulted from disruptions caused by the transfer of immigration functions from the legacy Immigration and Naturalization Service in the Department of Justice to the new USCIS in the newly created Department of Homeland Security in 2003.33 The 2005 increase in employment-based LPRs resulted from a provision in the Real ID Act of 2005, which provided for the "recapture" or re-use of past unused employment-based visa numbers.34

Within the total number of employment-based immigrants, the annual number of employment-based preference LPRs have fluctuated substantially over the two decades. In contrast with all other employment-based preference immigrants, the number of 5th preference immigrants increased tenfold between FY1997 and FY2017 (from 936 to 9,863), largely from the popularity of the USCIS EB-5 Regional Center Program.35

New Arrivals Versus Adjustments of Status

Most foreign nationals who became employment-based LPRs in the past two decades were already living in the United States and adjusted to LPR status from some other temporary (nonimmigrant) status (Figure 2).36 In FY2017, for example, 82% of employment-based LPRs adjusted to LPR status from within the United States; only 18% acquired LPR status as new arrivals from abroad. The 5th preference immigrant investors were the exception, with a majority being admitted as new arrivals since 2006.37

Pools of Prospective Employment-Based LPRs

As noted above, acquiring LPR status through the INA's employment-based immigration provisions requires a series of administrative steps performed by various federal agencies involving labor certifications, immigration petitions, and visa applications. The following section isolates and describes six distinct groups of LPR petitions and applications in order of administrative processing:

- pending labor certification applications at DOL,

- pending immigrant petitions at USCIS,

- pending approved visa applications at DOS,

- pending approved adjustment of status petitions at USCIS,

- visa applications submitted to DOS, and

- adjustment of status applications submitted to USCIS.

Because each step in the process involves some form of review or adjudication, a certain number of petitions or applications in each pool are denied and do not advance to the next step. As such, foreign nationals at the early stages of the employment-based immigration process face a lower likelihood of ultimately obtaining LPR status compared with those near the end of the process.

While the six distinct groups of petitions and applications discussed here illustrate the pools of prospective employment-based immigrants at different stages of administrative processing, only two pools represent applicants who are limited from advancing because of the INA's numerical limits. Those two pools (the third and the fourth) include those with approved employment-based immigrant petitions who are either waiting overseas to obtain a visa or waiting in the United States to adjust their status. As such, those two pools represent the employment-based immigration queue.38

Employment-based immigrant petitions are submitted not only on behalf of principal immigrants who meet the qualifications of the applicable preference category but also on behalf of derivative immigrants (i.e., the spouses and children accompanying or following to join the principal prospective immigrants) who are included in the same petition.39 In the discussion below of the fourth pool of prospective immigrants waiting to adjust status with USCIS, the number of derivative immigrants is estimated using USCIS data (see "Pending Approved Adjustment of Status Petitions at USCIS").

Pending Labor Certification Applications at DOL

As noted above, employers who wish to file a petition with USCIS for 2nd (professionals) and 3rd (skilled/unskilled) preference category immigrant workers must first obtain a foreign labor certification from DOL. The INA does not impose limits on the number of labor certification requests that DOL can approve, and annual fluctuations in certification application volume generally reflect fluctuating employer labor demand.

For FY2018, DOL's Office of Foreign Labor Certification reported receiving 104,360 applications - and processing 119,776 applications from FY2018 and earlier years. Of the applications processed, 109,550 beneficiaries (91%) received certification, 6,255 (5%) were denied, and 3,971 (3%) were withdrawn.40

Pending Immigrant Petitions at USCIS

Once any required labor certification has been obtained, petitioners file one of three employment-based immigrant petitions (I-140, I-360, or I-526, as described above) with USCIS.41 As such, this queue represents a workflow of employment-based immigration petitions "in process" that have not yet been approved.

Data on petitions in this pool are presented in USCIS processing statistics issued each quarter. As of June 30, 2018 (the most recent date for which data are publicly available), pending employment-based immigration petitions numbered 45,889 for I-140 petitions, 49,898 for I-360 petitions, and 17,126 for I-526 petitions, totaling 112,913 for all three petition types. By comparison, 3rd quarter pending petitions for these three petition types totaled 115,159 in FY2017 and 81,302 in FY2016.42

Approval or denial hinges not on any numerical limits imposed by the INA but on whether petitioners have provided sufficient and appropriate documentation and whether the beneficiaries meet the qualifications for the specific preference category.

Pending Approved Visa Applications at DOS

The third pool of pending employment-based applicants includes foreign nationals living abroad with approved employment-based immigrant petitions who are waiting to apply for a numerically limited visa. Unlike the first and second pools above, this pool is limited from advancing to the next administrative step because of numerical restrictions imposed by the INA. This pool is the overseas equivalent to the pool of applicants with approved immigrant petitions waiting to adjust status at USCIS (discussed below). At the end of each fiscal year, DOS' National Visa Center (NVC) publishes a tabulation of persons with approved immigrant petitions who are waiting to apply for a visa.43 The NVC reported 112,189 pending applications for employment-based LPR visas as of November 1, 2017. Unlike the data on approved immigrant petitions that are pending with USCIS, visa applicants with DOS include both principal petition beneficiaries as well as their derivative spouses and children.

Table 3 presents the total number of persons, including derivatives, with approved employment-based immigrant petitions pending with the NVC as of November 1, 2017, by preference category and country of origin. Overall, almost half (47%) were for 3rd preference "professional and skilled workers." The next two categories with the largest number of pending visa petitions were for 5th preference employment creation "investors" and 2nd preference "professionals with advanced degrees or of exceptional ability." Table 3 also shows that China, India, and the Philippines dominate as the source countries for foreign nationals in this queue, comprising over four fifths (82%) of the total.

Table 3. Approved Pending Employment-Based Immigrants at DOS

(by preference category and top countries of origin, November 1, 2017)

|

Country of Origin |

1st (Priority) |

2nd (Profes-sional) |

3rd (Skilled) |

3rd (Other) |

4th (Special) |

5th (Investor) |

Total |

|

China |

2,212 |

1,689 |

1,840 |

1,955 |

— |

26,725 |

34,421 |

|

India |

402 |

10,961 |

21,962 |

454 |

136 |

307 |

34,222 |

|

Philippines |

— |

405 |

20,937 |

1,102 |

— |

— |

22,444 |

|

South Korea |

217 |

1,439 |

933 |

476 |

38 |

278 |

3,381 |

|

UK |

277 |

— |

733 |

— |

— |

— |

1,010 |

|

Vietnam |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

649 |

649 |

|

Mexico |

92 |

— |

— |

490 |

32 |

— |

614 |

|

Iran |

174 |

256 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

430 |

|

Hong Kong |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

423 |

423 |

|

Venezuela |

249 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

249 |

|

Canada |

210 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

210 |

|

Brazil |

170 |

— |

— |

— |

31 |

— |

201 |

|

France |

94 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

94 |

|

Cambodia |

— |

— |

— |

— |

25 |

— |

25 |

|

All Others |

1,430 |

1,975 |

6,789 |

1,416 |

329 |

1,877 |

13,816 |

|

Total |

5,527 |

16,725 |

53,194 |

5,893 |

591 |

30,259 |

112,189 |

Source: U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, Annual Report of Immigrant Visa Applicants in the Family-Sponsored and Employment-Based Preferences Registered at the National Visa Center as of November 1, 2017.

Notes: U.K. refers to Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The notation "—" indicates no value for the category.

Pending Approved Adjustment of Status Petitions at USCIS

The fourth pool of pending employment-based applications includes foreign nationals already present in the United States with approved employment-based immigrant petitions who have not yet adjusted status. This pool is the domestic equivalent to the pool of applicants with approved immigrant petitions waiting to apply for a visa (discussed above). This pool is the largest of the six discussed in this section. These foreign nationals reside in the United States as legal nonimmigrants, and many work as skilled temporary workers with H-1B visas.

Prospective immigrants can only file an adjustment of status application (Form I-485) after DOS has indicated that a visa number is available. Such availability depends on how many visa numbers DOS has already allocated—for persons applying from abroad as well as those seeking to adjust status from within the United States—for the specific employment preference category during that fiscal quarter. It also depends on whether visa numbers are available within that category for persons from their country of origin, given the 7% per-country ceiling. If a visa is available even with these two constraints, prospective immigrants with approved immigrant petitions can submit an adjustment of status application to USCIS.

Although USCIS does not regularly publish reports on the population of foreign nationals with approved immigrant petitions who are waiting to adjust status, one recent report on this pool of applicants is publicly available (Table 4).44 It indicates that 395,025 approved petitions were pending as of April 20, 2018.45 Indian nationals, with 306,601 approved petitions (78%), and Chinese nationals, with 67,031 approved petitions (17%), together account for 95% of all petitions in this pool. More than half of these petitions are for the 2nd employment-based preference category.

Table 4. Approved Pending Employment-Based Immigrant Petitions at USCIS

(Immigrant petitions approved as of April 20, 2018, with priority dates on or after May 2018)

|

Country of Origin |

1st (Priority) |

2nd (Profes-sional) |

3rd (Skilled) |

3rd (Other) |

4th (Special) |

5th (Investor) |

Total |

|

China |

23,530 |

16,617 |

3,948 |

521 |

— |

22,415 |

67,031 |

|

El Salvador |

— |

— |

— |

— |

7,252 |

— |

7,252 |

|

Guatemala |

— |

— |

— |

— |

6,027 |

— |

6,027 |

|

Honduras |

— |

— |

— |

— |

5,402 |

— |

5,402 |

|

India |

34,824 |

216,684 |

54,892 |

201 |

— |

— |

306,601 |

|

Mexico |

— |

— |

— |

— |

700 |

— |

700 |

|

Philippines |

— |

— |

1,476 |

15 |

— |

— |

1,491 |

|

Vietnam |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

521 |

521 |

|

Total |

58,354 |

233,301 |

60,316 |

737 |

19,381 |

22,936 |

395,025 |

Source: USCIS, "Form I-140, Immigration Petition for Alien Worker, Form I-360, Petition for Amerasian, Widow(er), or Special Immigrant - Employment Based, Form I-526, Immigrant Petition by Alien Entrepreneur, Count of Approved Petitions as of April 20, 2018 with Priority Date On or After May 2018 Department of State Visa Bulletin."

Notes: According to USCIS, this report was prepared as part of a special congressional request and may not precisely measure this pool's population. As noted in the text, figures in Table 4 may overstate the number of pending petitions and may include petitions from other pools that are discussed in this report. For example, the figures may include multiple petitions for the same individuals, reflecting attempts to improve the likelihood of acquiring LPR status by petitioning through different LPR pathways. Some petitions may be for foreign nationals who ultimately acquire LPR status in another way. Some petitions may have been for foreign nationals overseas that USCIS subsequently forwarded to DOS for visa processing. USCIS Briefing to CRS, October 31, 2018. "—" indicates no value for the category.

Figures presented in Table 4 represent only principal immigrants and do not account for derivative immigrants. However, the USCIS report cited in the table also presents FY2016 data on the average number of derivative immigrants receiving LPR status through principal immigrants for each employment-based preference category (Table 5). These "derivative multipliers" presented by USCIS can then be applied to the pending principal petitions to estimate the numbers of derivative immigrants included in the principal immigrant petitions for each preference category. CRS used these multipliers to compute estimated numbers of derivatives that are shown in Table 5. Summing the total estimated derivative figure (431,842) with the actual principal figure (395,025) yields an estimate of the total number of foreign nationals included in this pool of approved pending immigrant petitions (826,867).

Table 5. Approved Pending Employment-Based Immigrant Petitions at USCIS

(Actual principal immigrant petitions and estimated derivative immigrants included, April 20, 2018)

|

1st (Priority) |

2nd (Profes-sional) |

3rd (Skilled) |

3rd (Other) |

4th (Special) |

5th (Investor) |

Total |

|

|

Actual Principal Immigrants |

58,354 |

233,301 |

60,316 |

737 |

19,381 |

22,936 |

395,025 |

|

Derivative Immigrant Multiplier |

1.4 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

1.5 |

0.3 |

1.9 |

N/A |

|

Estimated Derivative Immigrants |

81,696 |

233,301 |

66,348 |

1,106 |

5,814 |

43,578 |

431,842 |

|

Total Estimated Immigrants |

140,050 |

466,602 |

126,664 |

1,843 |

25,195 |

66,514 |

826,867 |

Source: USCIS, "Form I-140, Immigration Petition for Alien Worker, Form I-360, Petition for Amerasian, Widow(er), or Special Immigrant - Employment Based Form I-526, Immigrant Petition by Alien Entrepreneur, Count of Approved Petitions as of April 20, 2018 with Priority Date On or After May 2018 Department of State Visa Bulletin." Estimated derivative immigrants and total estimated immigrants were computed by CRS using the derivative immigrant multiplier found in the USCIS report cited above.

Notes: "N/A" indicates not applicable for the category.

Visa Applications Submitted to DOS

The fifth pool of pending employment-based applications includes visa applicants overseas who have had their I-140 immigration petitions approved, have been allocated a numerically limited visa number, and have submitted their application for a visa. Most can expect to receive an interview with a DOS consular official, the last major step in this pathway to LPR status.

DOS does not publish statistics on this pool of applications, but in its monthly Visa Bulletin, it presents visa application filing dates in addition to application "cut off" or final action dates. Prospective employment-based immigrants with priority dates on or prior to the filing dates may submit their visa applications and accompanying documentation to DOS. The filing dates, which DOS began publishing in 2015, are intended to have applicants submit their paperwork ahead of time to ensure a more accurate tally of visa numbers available each quarter.46 A rough estimate of this pool of visa applications submitted to DOS would consist of those whose priority dates fall between the filing dates and the final action dates in the Visa Bulletin.47

Adjustment of Status Applications Submitted to USCIS

The sixth pool of pending employment-based applications includes foreign nationals (including derivatives) with approved employment-based petitions who had been granted a numerically limited visa number and had filed I-485 (Application to Register Permanent Residence or Adjust Status) applications with USCIS to adjust status. Applications in this pool, sometimes referred to as the "I-485 Inventory," fall into two groups.48

Table 6. Employment-Based I-485 (Adjustment of Status) Applications In Process

(at USCIS Service Centers, by preference category and top countries, July 2018)

|

Country of Origin |

1st (Priority) |

2nd (Profes-sional) |

3rd (Skilled & Other) |

4th (Special) |

5th (Investor) |

Total |

|

China |

1,419 |

90 |

71 |

25 |

455 |

2,060 |

|

India |

3,168 |

15,826 |

473 |

152 |

43 |

19,662 |

|

Mexico |

315 |

77 |

89 |

36 |

2 |

519 |

|

Philippines |

17 |

177 |

53 |

35 |

— |

282 |

|

All Others |

2,638 |

2,053 |

1,012 |

515 |

205 |

6,423 |

|

Total |

7,557 |

18,223 |

1,698 |

763 |

705 |

28,946 |

Source: USCIS Employment-Based I-485 Inventory Statistics – updated July 2018, https://www.uscis.gov/greencard/pending-employment-based-i-485-inventory.

Notes: The total presented excludes 525 "Employment Third Preference Other Worker" (EW) applications that USCIS did not distribute among the five preference categories in its statistics. As such, the final total presented by USCIS for this pool was 28,946 plus 525 or 29,471.

The first group of I-485 adjustment of status applications include those that had received visa numbers prior to March 6, 2017. These were being processed by USCIS's Service Center Operations (SCOPS), and totaled 29,471 as of July 2018 (Table 6, Notes).49 Among this group, almost two-thirds (63%) were filed by 2nd preference applicants (professionals with advanced degrees or of exceptional ability), and one fourth (26%) by 1st preference applicants (priority workers). India was the dominant source country for these I-485 applicants with over two-thirds (68%) of the total.50

The second group of I-485 adjustment of status applications include all those submitted on or after March 6, 2017 which are processed by the USCIS Field Operations Directorate (FOD).51 Data on the FOD group of I-485 applications are not publicly available. According to USCIS, however, the FOD group is several times larger than the SCOPS group described above.52

As noted above, prospective immigrants can only file an I-485 application once a visa number is available. For both groups of submitted I-485 applications, therefore, DOS has already allotted visa numbers. As such, these applications represent an administrative processing backlog and not a queue of prospective immigrants waiting for numerically limited visa numbers. USCIS data indicate that the agency approves most I-485 applicants.53 Thus, these I-485 applicants, who have almost completed the employment-based immigration process, are among the most likely to receive LPR status among the six pools of petitioners and applicants discussed in this section.

Caveats on the Data on Pools of Prospective Employment-Based Immigrants

The discussion above, which described six pools of petitions and applications processed by DOL, USCIS, and DOS across the employment-based LPR process, requires several caveats. First, because the six pools sometimes represent petitions and applications that are summed and presented by agencies at different dates (e.g., November 1, 2017, April 2018), they may not be strictly comparable. Second, figures for petitions at USCIS do not include prospective derivative immigrants, although the latter were estimated for the fourth pool described above (pending approved adjustment of status petitions at USCIS). Third, according to USCIS, some portion of petitions and applications in the fourth pool may be included in other pools discussed because of accounting protocols and processing timing differences. According to the agency, the fourth pool also includes many duplicate or inactive petitions.54

The six pools present (to the extent permitted by available data) a cross-sectional view of petition and application processing. The first and second pools represent workload queues that reflect relative demand for foreign workers during the fiscal year. The third and fourth pools represent queues of approved pending visa and adjustment of status applications that cannot advance because of the INA's numerical limits and the 7% per-country ceiling. The fifth and sixth pools represent administrative backlogs of applications that have been allocated numerically limited visa numbers and are closest to completion.

Should the Per-country Ceiling Be Revised?

Proposals to adjust or eliminate the per-country ceiling on employment-based immigration have appeared in legislative proposals in recent Congresses. For example, the Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act (S. 744), a comprehensive immigration reform bill which passed the Senate in the 113th Congress, would have eliminated the per-country ceiling for employment-based immigration and raised it for family-based immigration from 7% to 15%. An identical provision was introduced in the 115th Congress with H.R. 392 (i.e., the "Yoder Amendment" to the Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act, 2019 (H.R. 6776)).

Arguments In Favor

Those who favor raising or eliminating the employment-based per-country ceiling argue that the current employment-based immigration system makes prospective employment-based immigrants wait for excessively long periods to acquire LPR status. During these waits, such foreign workers are generally unable to reunite with spouses and children who reside overseas.

Others who favor eliminating the per-country ceiling contend that the current system discriminates against some foreign workers based on their country of origin, a characteristic they contend has little bearing on workers' labor market contributions. Such proponents argue that the current system effectively ties immigrant workers to the employers that sponsor them for extended periods and invites potential exploitation. According to this perspective, employers who petition on behalf of prospective employment-based immigrants have disproportionate power over them. Because such employers can withdraw their petitions at will, they discourage foreign workers from negotiating for higher wages and/or improved working conditions.55 All else being equal, rational employers therefore benefit financially by sponsoring such workers who remain relatively immobile during their extensive waits to receive LPR status. Prospective immigrants who consider leaving their employers face the prospect of effectively forfeiting their pending employment-based immigrant petitions. If they cannot utilize another immigration pathway to remain in the United States, they must return to their home countries.

In particular, Indian (and to a lesser extent Chinese and Filipino) nationals sit in much longer queues of pending employment-based petitions submitted to USCIS and visa applications to DOS than their counterparts from other countries.56 They consequently must wait the longest to obtain LPR status. Those who favor eliminating the per-country cap contend that such circumstances effectively encourage employers to sponsor prospective employment-based immigrants primarily from India.57 According to this perspective, de facto discrimination results on the basis of origin country, fostered partly by U.S. laws which otherwise prohibit most forms of labor market discrimination. The more that employers follow this hiring approach, the greater the queue of Indian prospective immigrants and the longer the waiting times for acquiring LPR status, creating a self-reinforcing cycle that may limit hiring of prospective employment-based immigrants from other countries.

Proponents argue, therefore, that removing the per-country ceiling from employment-based immigrants would "level the playing field" by making immigrants from all countries more equally attractive to employers. If the per-country ceiling is eliminated and the current queue of pending petitions and visas is processed, proponents argue, employers would have no incentive to sponsor employment-based immigrants from any one country over others except based on conventional labor market criteria. As a result, waiting times for prospective employment-based immigrants to receive LPR status would ultimately equalize across countries of origin.

From a national interest perspective, many have argued that current circumstances discourage skilled foreign workers from countries such as India from seeking employment and immigration sponsorship in the United States.58 Prospective immigrants, aware that they could wait for substantial periods of time before actually receiving LPR status, may decide to start their careers and conduct entrepreneurial activities in other countries where the equivalent of LPR status is more quickly obtained. Consequently, firms who wish to attract highly skilled foreign workers may face competitive disadvantages compared to firms based in countries that provide permanent legal status more easily. Some empirical research suggests that long waits for LPR status affects the number of highly trained students in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) programs who remain in the United States to work after completing their studies.59

Arguments Against

Opponents of removing the per-country ceiling contend that doing so would substantially reduce country-of-origin diversity and potentially allow a few countries to dominate all permanent employment-based immigration to the United States. They contend that removing the per-country ceiling would advantage Indian and Chinese prospective immigrants who would move more quickly to the head of the queue at the expense of those from all other countries.60

Arguments against lifting the per-country ceiling often point to the H-1B visa for temporary "professional specialty workers," an employment category generally associated with STEM fields.61 The H-1B visa represents a frequently used pathway for skilled nonimmigrant (temporary) workers to become employment-based immigrants.62 Some observers criticize the H-1B visa as exploitative of foreign workers, mostly from India, because once sponsored for employment-based LPR status, workers are unable to change employers, leaving them vulnerable to exploitative practices.63 They note that Indian nationals dominate H-1B visa recipients with almost three fourths of the total.64

Anticipated Outcomes

Many observers are interested in how revising the per-country ceiling would affect future flows of employment-based immigrants. Estimating such impacts are challenging for a number of reasons, including the complex accounting among the six pools of petitions and applications. If Congress eliminated the per-country ceiling for employment-based immigrants, many expect that Indian and Chinese nationals would dominate the flow of new employment-based LPRs for as many years as needed to clear out the accumulated queue of prospective immigrants from those countries. This queue would include those with approved employment-based immigrant petitions who are waiting to file either a visa application with DOS or an adjustment of status application with USCIS (i.e., the third and fourth pools discussed above in "Pools of Prospective Employment-Based LPRs.")

As noted above, the "Yoder Amendment," which was introduced during the 115th Congress and would eliminate the per-country ceiling for all employment-based preference categories, illustrates what kind of impacts might be expected.65 The amendment would phase out the ceiling over four years. In the first year, a single country could use 85% of all visa numbers in a preference category with the remaining 15% still subject to the 7% per-country ceiling. Thus for the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd preference categories, each of which account for 40,040 visa numbers under the current system, this would amount to 34,034 visa numbers (40,040 x 0.85) for each of the first three preference categories in the first year after enactment. That percentage would increase to 90% for the second and third years (36,036 visa numbers), and reach 100% in the fourth and subsequent years.

To illustrate this further, consider the 3rd employment-based preference category. Data presented above for the third and fourth pools in "Pools of Prospective Employment-Based LPRs" yield an estimated 170,000 principal and derivative immigrants from India, China, and the Philippines who were waiting for LPR status in 2018.66 Given the parameters of the Yoder Amendment, one could estimate that roughly four to five years would be required to eliminate this queue of prospective 3rd preference employment-based immigrants.67

Other outcomes may also result from eliminating the per-country ceiling, apart from reducing certain queues of prospective immigrants more quickly, and removing the perceived employer incentive to choose nationals from these countries over other countries. For example, shorter wait times for LPR status might actually incentivize greater numbers of nationals from India, China, and the Philippines to seek employment-based LPR status. If that were to occur, the reduction in the number of approved petitions pending might be short-lived. In addition, absent a per-country ceiling, a handful of countries could conceivably dominate employment-based immigration, possibly benefitting certain industries that employ foreign workers from those countries, at the expense of foreign workers from other countries and other industries that might employ them.

In addition, because the INA grants LPRs the ability to sponsor family members through its family-sponsorship provisions, removing the per-country ceiling would alter, to an unknown extent, the country-of-origin composition of subsequent family-based immigrants acquiring LPR status each year.68

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

LPRs are foreign nationals who have been approved to live and work permanently in the United States. In this report, the terms LPR and immigrant are used interchangeably. |

| 2. |

For a more complete discussion of permanent legal immigration, see CRS Report R42866, Permanent Legal Immigration to the United States: Policy Overview. |

| 3. |

The Immigration and Nationality Act was originally enacted as Act of June 27, 1952, ch. 477, and has been subsequently amended. The Immigration Amendments of 1965 (also known as the Hart-Celler Act, P.L. 89-236) replaced the national origins quota system (enacted after World War I) with the per-country ceiling. The Immigration Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-649), which increased the numerical limits for employment-based immigrants, was the last law to substantially revise employment-based immigration. With respect to employment-based immigration, the 1990 act revised the preference system and the labor certification process (discussed below). |

| 4. |

INA §202(a)(2), 8 U.S.C. §1152. This report uses the phrase "per-country ceiling" in the singular form throughout although technically there are several caps. For a "dependent foreign state"—a category that encompasses any colony, component, or dependent area of a foreign state, such as the Azores and Madeira Islands of Portugal and Macau of the People's Republic of China—the per-country ceiling is 2%. The 7% per-country ceiling also applies to family-sponsored preference immigrants (see CRS Report R43145, U.S. Family-Based Immigration Policy). This report focuses exclusively on the per-country ceiling for employment-based immigration. |

| 5. |

See, for example, Maria L. Ontiveros, "H-1B Visas, Outsourcing and Body Shops: A Continuum of Exploitation for High Tech Workers," Berkeley Journal of Employment & Labor Law, vol. 38 (2017), pp. 2-46. |

| 6. |

See, for example, Jessica Vaughan, "Scrapping the Per-Country Cap Helps the Companies that Shun U.S. Tech Workers," Center for Immigration Studies, November 9, 2018. |

| 7. |

Many legislative proposals would alter the per-country cap for both employment-based as well as family-based immigration. This report focuses entirely on employment-based immigration. |

| 8. |

The INA defines immediate relatives as the spouses and unmarried minor children of U.S. citizens, and the parents of adult U.S. citizens. |

| 9. |

See, respectively, INA §§201(c)-(e), 8 U.S.C. §§1151(c)-(e). The Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act of 1997 (NACARA; P.L. 105-100) temporarily decreases the 55,000 annual ceiling on the diversity visa category. Since FY1999, this ceiling has been reduced by up to 5,000 annually to offset immigrant numbers made available to certain unsuccessful asylum seekers from El Salvador, Guatemala, and formerly communist countries in Europe who are being granted immigrant status under special rules established by NACARA. NACARA Section 203(e) states that when the cut-off date (the visa availability date for oversubscribed immigration categories) for the employment 3rd preference "other worker" (OW) category reaches the priority (filing) date of the latest OW petition approved prior to November 19, 1997, the 10,000 OW numbers available for a fiscal year are to be reduced by up to 5,000 annually beginning in the following fiscal year. Since the OW cut-off date reached November 19, 1997, during FY2001, the reduced OW limit began in FY2002 and will continue until all NACARA adjustments are offset. |

| 10. |

Apart from the INA's worldwide limit on family-based, employment-based and diversity immigrants, refugees and asylees, who are technically not classified as immigrants by the INA, may also acquire LPR status. The number of refugees admitted each year is determined by the President, in consultation with Congress. The INA does not impose a statutory limit on the number of refugees or asylees who can acquire LPR status each year. For more information, see CRS Report RL31269, Refugee Admissions and Resettlement Policy. |

| 11. |

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics 2017, Table 6. |

| 12. |

INA §202(a)(2); 8 U.S.C. §1152. |

| 13. |

U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, Operation of the Immigrant Numerical Control Process, undated, p. 3. |

| 14. |

Nonimmigrants are admitted for a specific purpose and a temporary period of time—such as tourists, foreign students, diplomats, temporary agricultural workers, exchange visitors, or intracompany business personnel. Nonimmigrants are often referred to by the letter that denotes their specific provision in the statute, such as H-2A agricultural workers, F-1 foreign students, or J-1 cultural exchange visitors. For more information, see CRS Report R45040, Nonimmigrant (Temporary) Admissions to the United States: Policy and Trends. |

| 15. |

Self-petitioning is available to persons of extraordinary ability within the 1st preference category (INA §204(a)(1)(E), 8 U.S.C. §1154(a)(1)(E)); immigrants applying within the 2nd preference category who qualify for a national interest waiver (8 C.F.R.§204.5(k)(1)); special immigrants within the 4th preference category (INA §204(a)(1)(G), 8 U.S.C. §1154(a)(1)(G)); and investor immigrants within the 5th preference category (INA §204(a)(1)(H), 8 U.S.C. §1154(a)(1)(H)). A national interest waiver allows foreign nationals to petition for employment-based LPR status without obtaining a labor certification from the Department of Labor (DOL) because it is in the interest of the United States. The INA does not define which jobs qualify for the waiver, but it is typically granted to individuals "with exceptional ability and whose employment in the United States would greatly benefit the nation." For more information, see U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, "Employment-Based Immigration: Second Preference EB-2," at https://www.uscis.gov/working-united-states/permanent-workers/employment-based-immigration-second-preference-eb-2, updated October 29, 2015. |

| 16. |

USCIS formally uses the term petition to refer to a request for an immigration benefit that is submitted by one party (e.g., an employer) on behalf of another (e.g., the prospective immigrant) and the term application to refer to an immigration benefit submitted by the individual receiving the benefit. In this report, these two terms may be used interchangeably. |

| 17. |

Visas are required for prospective immigrants who reside overseas, but not for those residing in the United States. Visas allow foreign nationals to travel to a U.S. land, air, or sea port of entry and request permission from a Customs and Border Protection (CBP) inspector to enter the United States. Having a visa does not guarantee U.S. entry but it shows that a consular officer at a U.S. Embassy or Consulate abroad has determined that the visa bearer is eligible to seek U.S. entry for the specific purpose indicated by the specific visa. For background information on visa issuances, see CRS Report R43589, Immigration: Visa Security Policies. Prospective employment-based immigrants who are admitted to the United States receive LPR status upon arrival. |

| 18. |

In this report, the term visa number refers to the number of LPRs that the INA permits each year under its numerical and per-country limits. This should not be confused with visas which DOS grants to foreign nationals residing overseas to allow them to travel to the United States and request admission at a U.S. port of entry. |

| 19. |

INA §203(b); 8 U.S.C. §1153. |

| 20. |

Unused visa numbers for the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd employment-based preference categories "roll down" to the next category. Unused visa numbers for the 4th and 5th categories "roll up" to the 1st category. INA §203(b); 8 U.S.C. §1153. |

| 21. |

The American Competitiveness in the Twenty-First Century Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-313) enabled the per-country ceiling for employment-based immigrants to be surpassed for individual countries that are oversubscribed as long as visas are available within the 140,000 annual worldwide limit for employment-based preference immigrants. INA 202(a)(5)(A), 8 U.S.C. 1152(a)(5)(A). |

| 22. |

INA §201(d)(2)(C); 8 U.S.C. §1151(d)(2)(C). In recent years, the number of these visa numbers has been relatively insignificant. |

| 23. |

For more information, see Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Visa Retrogression, https://www.uscis.gov/green-card/green-card-processes-and-procedures/visa-availability-priority-dates/visa-retrogression. |

| 24. |

INA §212(a)(5); 8 U.S.C. §1182(a)(5). |

| 25. |

In most cases, the priority date is the date that USCIS accepts the completed petition form for processing. For more information, see U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, "Visa Availability and Priority Dates" at https://www.uscis.gov/greencard/visa-availability-priority-dates. |

| 26. |

Individuals can use DOS's monthly online Visa Bulletin to check whether their priority date is current. |

| 27. |

USCIS's National Benefits Center conducts background investigations for I-485 applications, including collecting fingerprints, conducting background checks, and reviewing for possible fraud and grounds for inadmissibility. USCIS puts applicants who pass these reviews into an interview queue and schedules them for interviews. |

| 28. |

As of March 6 2017, President Trump's Executive Order 13780 mandated that USCIS interview all prospective EB-1, EB-2, and EB-3 employment-based immigrants residing in the United States and applying to adjust status. Previously, USCIS had discretion to defer to the findings of prior interviews conducted by consular officials granting the individuals visas to come initially to the United States. USCIS generally waived such interviews except in cases of evidence of fraud or security concern. See Executive Order 13780, "Protecting the Nation From Foreign Terrorist Entry Into the United States," 82 Federal Register 13209-13219, March 6, 2017. |

| 29. |

All LPR applicants generally must be interviewed by a DOS consular officer. The interview enables the officer to verify the contents of the application and check medical, criminal, and financial records to see whether an applicant is inadmissible on grounds outlined in the INA. |

| 30. |

For information on how DOS allocates numerically limited immigrant visa numbers, see U.S. Department of State, "The Operation of the Immigrant Numerical Control System," undated, https://travel.state.gov/content/dam/visas/Immigrant%20Visa%20Control%20System_operation%20of.pdf. |

| 31. |

The Immigration Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-649) substantially revised employment-based preference categories and raised the numerical limits. These amendments were fully implemented by 1994. |

| 32. |

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics, 2016 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, Table 6. |

| 33. |

Confirmed by USCIS, CRS briefing, October 31, 2018. |

| 34. |

Section 502 of the Real ID Act of 2005 is found in Division B of P.L. 109-13, the Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act for Defense, the Global War on Terror, and Tsunami Relief. |

| 35. |

Congress created the Regional Center Program in Section 610 of P.L. 102-395, which provided an additional pathway to LPR status through the EB-5 visa category. Regional centers are "any economic unit, public or private, which [are] involved with the promotion of economic growth, including increased export sales, improved regional productivity, job creation, and increased domestic capital investment." 8 C.F.R. §204.6 (e). The program allows foreign investors to pool their investment in a regional center to fund a broad range of projects within a specific geographic area. The investment requirement for regional center investors is the same as for standard EB-5 investors. For more information, see CRS Report R44475, EB-5 Immigrant Investor Visa. |

| 36. |

DHS does not publish data detailing from what nonimmigrant categories status adjusters are leaving. |

| 37. |

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics, 2016 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, Table 6. |

| 38. |

In this report, the term "queue" refers to persons who are waiting to advance in the process of obtaining LPR status because of the numerical limits and per-country ceiling specified in the INA. In contrast, the term "backlog" refers to persons waiting due to administrative processing. Backlogs can often expand or contract depending on how an agency utilizes its personnel to process applications and petitions. Unless otherwise specified, the USCIS backlogs referred to in this report occur under normal operating conditions within USCIS. |

| 39. |

Derivative employment-based immigrants are entitled to their status under INA §203(b), 8 U.S.C. §1153(d). |

| 40. |

U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration, Office of Foreign Labor Certification, Permanent Labor Certification Program, Selected Statistics, FY 2018 YTD, data as of September 30, 2018. |

| 41. |

As noted above, most employment-based petitioners must file an Immigrant Petition for Alien Workers (USCIS Form I-140). Petitioners under the 4th special immigrant category must file a Petition for Amerasian Widow(er), or Special Immigrant (USCIS Form I-360), and petitioners under the 5th immigrant investor category must file an Immigrant Petition by Alien Entrepreneur (USCIS Form I-526). |

| 42. |

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, "Data Set: All USCIS Application and Petition Form Types" (updated October 30, 2018), https://www.uscis.gov/tools/reports-studies/immigration-forms-data/data-set-all-uscis-application-and-petition-form-types. This web page has links to 3rd quarter data for FY2018, FY2016, and FY2014. |

| 43. |

U.S. Department of State, Annual Report of Immigrant Visa Applicants in the Family-Sponsored and Employment-Based Preferences Registered at the National Visa Center as of November 1, 2017. |

| 44. |

See Table 3 notes. USCIS, "Form I-140, Immigration Petition for Alien Worker, Form I-360, Petition for Amerasian, Widow(er), or Special Immigrant - Employment Based Form I-526, Immigrant Petition by Alien Entrepreneur, Count of Approved Petitions as of April 20, 2018 with Priority Date On or After May 2018 Department of State Visa Bulletin," accessed by CRS on November 5, 2018 at https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/files/nativedocuments/Count_of_Approved_I-140_I-360_and_I-526_Petitions_as_of_April_20_2018_with_a_Priority_Date_On_or_After_May_2018.PDF. |

| 45. |

Petitions were classified as pending based upon DOS's Visa Bulletin for May 2018. See U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, Visa Bulletin For May 2018, April 6, 2018. |

| 46. |

The White House, Modernizing and Streamlining Our Legal Immigration System for the 21st Century, July 2015. |

| 47. |

USCIS Briefing to CRS, October 31, 2018. |

| 48. |

This dichotomy stems from Executive Order 13780 discussed above which was issued on March 6, 2017 and mandated face-to-face interviews for all prospective EB1, EB2, and EB3 employment-based immigrants as a security measure. |

| 49. |

July 2018 represents the most recent data available as of November 2, 2018. See USCIS, "Employment-Based I-485 Inventory Statistics," updated July 2018, https://www.uscis.gov/greencard/pending-employment-based-i-485-inventory. |

| 50. |

For more information on this group of applications, see USCIS, "Questions & Answers: Pending Employment-Based Form I-485 Inventory," February 25, 2016, https://www.uscis.gov/greencard/questions-answers-pending-employment-based-form-i-485-inventory. |

| 51. |

USCIS Briefing to CRS, October 31, 2018. |

| 52. |

Ibid. |

| 53. |

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, "Number of Service-wide Forms by Fiscal Year To- Date, Quarter, and Form Status 2018," 3rd Quarter (June 30, 2018), updated October 29, 2018, https://www.uscis.gov/tools/reports-studies/immigration-forms-data/data-set-all-uscis-application-and-petition-form-types. |

| 54. |

USCIS Briefing to CRS, October 31, 2018. |

| 55. |

See for example, Maria L. Ontiveros, "H-1B Visas, Outsourcing and Body Shops: A Continuum of Exploitation for High Tech Workers," Berkeley Journal of Employment & Labor Law, vol. 38 (2017), pp. 2-46. |

| 56. |

The queue of Indian workers, in particular, grew between 1999 and 2003 as the result of both the American Competitiveness and Workforce Improvement Act of 1998 (P.L. 105-277), which raised the cap on the H-1B nonimmigrant visa from 65,000 to 115,000 for FY999 and FY2000, and the American Competitiveness in the 21st Century Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-313), which increased the H-1B cap to 195,000 for FY2001, FY2002, and FY2003. Many H-1B workers are sponsored by U.S. employers as employment-based immigrants. For more discussion, see text below. |

| 57. |

Immigration Voice, "Green Card Backlogs, Per country Limits and bill H.R.392," press release, undated, https://immigrationvoice.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=5&Itemid=80. |

| 58. |

See for example, Parija Kavilanz, "Immigrant doctors in rural America are sick of waiting for green cards," CNN Money, June 13, 2018; Stuart Anderson, "Will Congress Ever Solve The Long Wait For Green Cards?," Forbes, May 21, 2018; and Stuart Anderson, Waiting and More Waiting: America's Family and Employment-Based Immigration System, National Foundation for American Policy, October 4, 2011; and The White House, Modernizing and Streamlining Our Immigration System for the 21st Century, July 2015, pp. 29-30. |

| 59. |

See, for example, Shulamit Kahn and Megan MacGarvie, "The Impact of Permanent Residency Delays for STEM PhDs: Who leaves and Why," NBER Working Paper No. 25175, October 2018. |

| 60. |

See, for example, Jessica Vaughan, "Scrapping the Per-Country Cap Helps the Companies that Shun U.S. Tech Workers," Center for Immigration Studies, November 9, 2018. |

| 61. |

More information on the H-1B visa can be found in CRS Report R43735, Temporary Professional, Managerial, and Skilled Foreign Workers: Policy and Trends. |

| 62. |

The H-1B visa is one of only a few temporary (nonimmigrant) visas that permit adjustment to LPR status. A common pathway to LPR status for foreign nationals involves education in the United States on a student visa, employment in the United States upon completion of studies using Optional Practical Training, employment through the H-1B visa, and, often through the same employer, sponsorship for employment-based LPR status. For more information, see CRS Report R45040, Nonimmigrant (Temporary) Admissions to the United States: Policy and Trends. |

| 63. |

See, for example, David North, "A Tale of Two Exploitative Foreign Worker Programs," Center for Immigration Studies, October 31, 2018. |

| 64. |