Economic and Fiscal Conditions in the U.S. Virgin Islands

Fiscal and economic challenges facing the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI) government raise several issues for Congress. Congress may choose to maintain oversight of federal policies that could affect the USVI’s long-term fiscal stability. Congress also may consider further legislation that would extend or restructure long-range disaster assistance programs to mitigate those challenges and promote greater resiliency of infrastructure and public programs. Federal responses to the USVI’s fiscal distress could conceivably affect municipal debt markets more broadly. Greater certainty in federal funding for disaster responses and Medicaid could support the USVI economy.

The USVI, like many other Caribbean islands acquired by European powers, were used to produce sugar and other tropical agricultural products and to further strategic interests such as shipping and the extension of naval forces. Once the United States acquired the U.S. Virgin Islands shortly before World War I, they effectively ceased to have major strategic importance. Moreover, at that time the Virgin Islands’ sugar-based economy had been in decline for decades.

While efforts of mainland and local policymakers eventually created a robust manufacturing sector after World War II, manufacturing in the Virgin Islands has struggled in the 21st century. In particular, the 2012 closing of the HOVENSA refinery operated by Hess Oil resulted in the loss of some 2,000 jobs and left the local economy highly dependent on tourism and related services. A renovation of the HOVENSA complex is reportedly in progress.

The territorial government, facing persistent economic challenges, covered some budget deficits with borrowed funds, which has raised concerns over levels of public debt and unfunded pension liabilities. Local policymakers have proposed tax increases and austerity measures to bolster public finances, which currently operate with restricted liquidity. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) expressed doubts that those fiscal measures would restore access to capital markets or address shortfalls in the funding of public pensions. The previous governor, Kenneth Mapp, set forth measures in his FY2019 budget proposals to delay expected public pension insolvency from 2024 to 2025 and promised to outline other measures that would further delay insolvency until 2028. Governor Albert Bryan Jr. succeeded Mapp in January 2019.

Damage caused by two powerful hurricanes—Irma and Maria—that hit the USVI in September 2017 created additional economic and social challenges. Public revenues, according to estimates based on USVI fiscal data, were halved after the two hurricanes. The USVI economy has relied heavily on tourism and related business activity, which made it more vulnerable to the effects of hurricanes than jurisdictions with more diverse economies. The severity of damage from Irma and Maria, and the subsequent disruption of the USVI tourism industry, suggest that a full economic recovery could take years.

Federal disaster assistance has included aid to public institutions, such as long-term loans to the USVI government and two hospitals; loans and grants to individuals and small businesses; and direct operations of the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA), the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Coast Guard, and other federal agencies. Funding for disaster relief has been augmented by supplemental appropriations. The extent of federal disaster assistance received by the USVI will depend, in part, on how funds provided in response to needs resulting from hurricanes and fires in 2017 are allocated among affected areas. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123; §20301), enacted on February 9, 2018, included additional Medicaid funding for the USVI and Puerto Rico through September 30, 2019. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) allocated $774 million in mitigation funds (CDBG-MIT funds) to the U.S. Virgin Islands and put restrictions on their use.

Economic and Fiscal Conditions in the U.S. Virgin Islands

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Geography

- Historical Background

- Second Voyage of Christopher Columbus

- Danish Colonial Era

- U.S. Acquisition and Administration

- Post-World War II Economic Development

- Current Structure of the Economy

- Income Trends and Distribution

- Tourism

- Manufacturing

- Agriculture

- Energy and Water

- Public Finances

- High Public Debt Levels Raise Concerns

- USVI Fiscal Responses

- Aftermath of Hurricanes Irma and Maria

- Disaster Responses

- Disaster Funding

- FY2019 Budget Proposals

- Economic Prospects

- Considerations for Congress

Figures

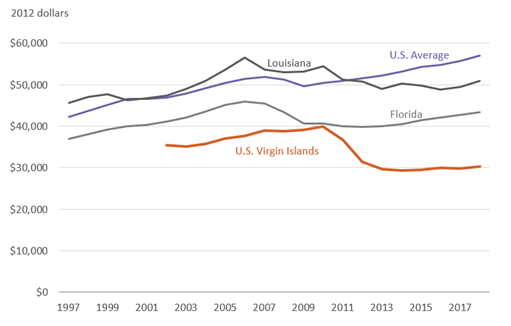

- Figure 1. Real Domestic Product per Capita, 1997-2019

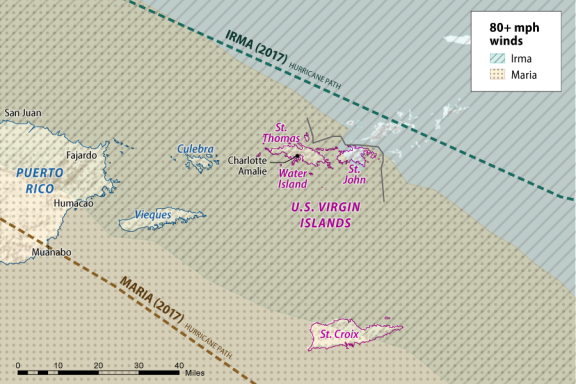

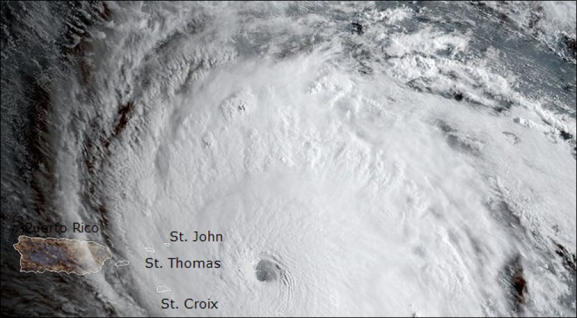

- Figure 2. Hurricane Irma, September 6, 2017

- Figure 3. Wind Speeds and Paths of Hurricanes Irma and Maria Near the U.S. Virgin Islands

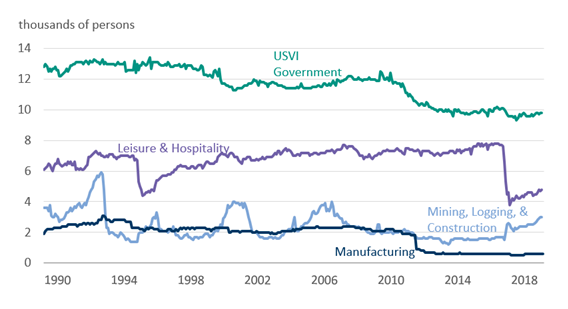

- Figure 4. Employment by Selected Sector in USVI, 1996-2019

- Figure 5. USVI Initial Unemployment Claims, 2007-2020

Summary

Fiscal and economic challenges facing the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI) government raise several issues for Congress. Congress may choose to maintain oversight of federal policies that could affect the USVI's long-term fiscal stability. Congress also may consider further legislation that would extend or restructure long-range disaster assistance programs to mitigate those challenges and promote greater resiliency of infrastructure and public programs. Federal responses to the USVI's fiscal distress could conceivably affect municipal debt markets more broadly. Greater certainty in federal funding for disaster responses and Medicaid could support the USVI economy.

The USVI, like many other Caribbean islands acquired by European powers, were used to produce sugar and other tropical agricultural products and to further strategic interests such as shipping and the extension of naval forces. Once the United States acquired the U.S. Virgin Islands shortly before World War I, they effectively ceased to have major strategic importance. Moreover, at that time the Virgin Islands' sugar-based economy had been in decline for decades.

While efforts of mainland and local policymakers eventually created a robust manufacturing sector after World War II, manufacturing in the Virgin Islands has struggled in the 21st century. In particular, the 2012 closing of the HOVENSA refinery operated by Hess Oil resulted in the loss of some 2,000 jobs and left the local economy highly dependent on tourism and related services. A renovation of the HOVENSA complex is reportedly in progress.

The territorial government, facing persistent economic challenges, covered some budget deficits with borrowed funds, which has raised concerns over levels of public debt and unfunded pension liabilities. Local policymakers have proposed tax increases and austerity measures to bolster public finances, which currently operate with restricted liquidity. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) expressed doubts that those fiscal measures would restore access to capital markets or address shortfalls in the funding of public pensions. The previous governor, Kenneth Mapp, set forth measures in his FY2019 budget proposals to delay expected public pension insolvency from 2024 to 2025 and promised to outline other measures that would further delay insolvency until 2028. Governor Albert Bryan Jr. succeeded Mapp in January 2019.

Damage caused by two powerful hurricanes—Irma and Maria—that hit the USVI in September 2017 created additional economic and social challenges. Public revenues, according to estimates based on USVI fiscal data, were halved after the two hurricanes. The USVI economy has relied heavily on tourism and related business activity, which made it more vulnerable to the effects of hurricanes than jurisdictions with more diverse economies. The severity of damage from Irma and Maria, and the subsequent disruption of the USVI tourism industry, suggest that a full economic recovery could take years.

Federal disaster assistance has included aid to public institutions, such as long-term loans to the USVI government and two hospitals; loans and grants to individuals and small businesses; and direct operations of the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA), the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Coast Guard, and other federal agencies. Funding for disaster relief has been augmented by supplemental appropriations. The extent of federal disaster assistance received by the USVI will depend, in part, on how funds provided in response to needs resulting from hurricanes and fires in 2017 are allocated among affected areas. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123; §20301), enacted on February 9, 2018, included additional Medicaid funding for the USVI and Puerto Rico through September 30, 2019. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) allocated $774 million in mitigation funds (CDBG-MIT funds) to the U.S. Virgin Islands and put restrictions on their use.

This report provides an overview of economic and fiscal conditions in the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI). The political status of the U.S. Virgin Islands and responses to Hurricanes Irma and Maria are not covered in depth here. Fiscal and economic challenges facing the USVI government raise several issues for Congress. First, Congress may choose to maintain oversight of federal policies that could affect the USVI's long-term fiscal stability. Second, Congress may consider further legislation that would extend or restructure long-range disaster assistance programs to mitigate those challenges and promote greater resiliency of infrastructure and public programs. Federal responses to the USVI's fiscal distress could conceivably affect municipal debt markets more broadly.

Geography

The U.S. Virgin Islands are located about 45 miles east of Puerto Rico and about 1,000 miles southeast of Miami, Florida. The three larger islands—St. Croix, St. Thomas, and St. John—are home to nearly all of the roughly 105,000 people living in the U.S. Virgin Islands. The USVI capital, Charlotte Amalie, is located on St. Thomas, which is the primary center for tourism, government, finance, trade, and commerce. The Virgin Islands National Park covers about two-thirds of the island of St. John, which is located to the east of St. Thomas. St. Croix—situated approximately 40 miles south of St. Thomas and St. John—is the agricultural and manufacturing center of the USVI. The U.S. Virgin Islands also includes a fourth smaller island—Water Island—as well as many other smaller islands and cays. The British Virgin Islands (BVI) are, by and large, east and slightly north of the U.S. Virgin Islands. The southern shore of Tortola, the largest island in BVI, is less than two miles north of the northern shore of St. John, USVI.

Historical Background

Second Voyage of Christopher Columbus

On his second voyage to the Caribbean in November 1493, Admiral Christopher Columbus and his crew reached the archipelago of the Lesser Antilles—the string of islands ranging southeast from Puerto Rico. As his ships sailed northwest toward Puerto Rico, they encountered one larger island, which Columbus named Santa Ursula, and saw to the north what they thought were at least 40-odd other islands, which were called "las once mil Vírgenes." Santa Ursula, now known as St. Croix, was described as "very high ground, most of which was bare, the likes of which no one had seen before or after."1 Over time those islands became known as the Virgin Islands.

In the decades following Columbus's voyages, the Spanish crown had nearly sole control over all trade and navigation in the Caribbean. By the mid-1500s, merchants and privateers from France, England, and Holland moved into the region to trade with colonists who chafed at the high prices and narrow restrictions of Spanish imperial rules. Spanish galleons returning to Spain with goods and gold provided an additional motivation to privateers and pirates. The Spanish shifted much of their settlements and operations to the South American mainland and to the larger Caribbean islands, where resources were easier to exploit and defenses were easier to mount. The smaller islands to the east in the Lesser Antilles were thus largely left to others. Control of many of those islands, including the Virgin Islands, shifted back and forth among European powers, as peace treaties settled in Europe seldom applied in the New World.2

Danish Colonial Era

In 1672, the Royal Danish West Indian Company (Det Kongelige Octroyerede Danske Vestindiske Compagnie) took control of St. Thomas and set up plantations. The company expanded to St. John (then St. Jan) in 1718 and then purchased St. Croix from France in 1733.3 Sugar production and export was the primary economic sector during the period of Danish colonial control, although cotton, tobacco, indigo, and other products were also exported. In 1754, the king of Denmark established a free trading policy, which encouraged commercial activity on St. Thomas, sidestepping restrictions imposed by the main European powers of the time.4 Economic conditions on those islands, however, slowed in the 1830s, and a slave revolt in 1848 led to the abolition of slavery.5

After 1848, the Virgin Islands' economy slowed for a combination of reasons. Other Caribbean ports attracted more trade, steam-powered ships traveled more directly between North America and Europe, and the expansion of beet sugar production in Europe, Russia, and North America led to lower prices for the cane sugar industry.6

U.S. Acquisition and Administration

In 1867, Secretary of State William Seward reached an agreement with Denmark to buy the islands. The Senate, however, declined to ratify the treaty.7 After other unsuccessful attempts in the first decade of the 20th century, the U.S. government purchased the islands from Denmark in 1917, after a set of negotiations prompted by concerns that Germany might use the islands to attack American shipping.8 The U.S. government assumed control of the islands on March 31, 1917, just a week before the United States entered World War I. While the United States acquired the islands for strategic reasons, the islands have not generally served a strategic purpose beyond keeping them out of the control of potentially hostile powers.

Naval officers administered the islands after the United States took possession and made important improvements in public health, water supply, education, and social services. Efforts to advance economic development were less successful.9 In 1931, governance responsibilities were transferred to the U.S. Department of the Interior.10 In the 1930s, civilian administrators sought—largely unsuccessfully—to revive sugar production and convert failing plantations into smallholder homesteads. The diversion of labor to military projects during World War II led to further declines in agricultural production. After the end of Prohibition in 1933, however, rum distilling became a growing source of manufacturing employment, and taxes on rum have been an important revenue source.

Post-World War II Economic Development

Other types of manufacturing once employed significant numbers, but have declined in recent years. Several watch assembly plants started up in 1959, but the last one closed in 2015.11 A large bauxite processing plant was built on St. Croix in the early 1960s, but closed in 2000 after several ownership changes.12 Near that site, Hess Oil partnered with a Venezuelan oil company to build a major oil refinery. That refinery, known as HOVENSA, for a time was one of the largest in the world, but closed in 2012.13

Early efforts in the 1950s to promote tourism were another success, especially after the closing of Cuba to American tourism after the 1959 Cuban Revolution. Tourism remains the major employer and economic activity in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

The Revised Organic Act of 1954 (P.L. 83-517) included a provision to rebate, or "cover over," federal excise taxes on goods produced in the Virgin Islands to the island's government.14 The cover over of federal taxes on rum has been an especially important revenue source.

Current Structure of the Economy

Income Trends and Distribution

Typical incomes in the USVI are lower than on the U.S. mainland and poverty rates are higher.

Household Incomes

Median household income in the USVI in 2009, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, was $37,254, about 75% of the mainland estimate of $50,221.15 Demographic and economic data for U.S. territories are typically less extensive and reported less frequently than for states.16 Table 1 compares the distribution of household incomes in 2009 for the USVI with the U.S. total.

The distribution of household income levels in the USVI is skewed toward lower income brackets compared to U.S. totals. For example, 13.5% of USVI households had incomes below $10,000 in 2009, as compared to 7.8% for the U.S. total.

|

United States |

% of Households |

USVI |

% of Households |

|

Less than $10,000 |

7.8% |

Less than $5,000 |

7.4% |

|

$5,000 to $9,999 |

6.1% |

||

|

$10,000 to $14,999 |

5.7% |

$10,000 to $14,999 |

6.9% |

|

$15,000 to $24,999 |

11.2% |

$15,000 to $24,999 |

14.4% |

|

$25,000 to $34,999 |

10.7% |

$25,000 to $34,999 |

12.3% |

|

$35,000 to $49,999 |

14.4% |

$35,000 to $49,999 |

14.5% |

|

$50,000 to $74,999 |

18.3% |

$50,000 to $74,999 |

16.9% |

|

$75,000 to $99,999 |

12.0% |

$75,000 to $99,999 |

9.3% |

|

$100,000 to $149,999 |

11.7% |

$100,000 or more |

12.2% |

|

$150,000 to $199,999 |

4.1% |

||

|

$200,000 or more |

3.9% |

||

|

Median household income |

$50,221 |

Median household income |

$37,254 |

|

Mean household income |

$68,914 |

Mean household income |

$52,261 |

|

Total households |

113,616,229 |

Total households |

43,214 |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, DP03: Selected Economic Characteristics: 2009 for USVI and the United States.

Notes: U.S. total is for resident population within the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. Data collection for the mainland and USVI differs in certain ways. In general, Census Bureau data for USVI were gathered using decennial census long forms, while much of the mainland data are gathered through the American Community Survey program.

GDP per Capita and Distortions Due to Tax Avoidance

Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita provides another measure of economy activity. GDP is defined as the value of goods and services produced in a given area during a year. While income produced in an area that is repatriated elsewhere is included in GDP, it is excluded from gross national product (GNP), which reflects incomes of area residents. For areas where flows of repatriated earnings are large, GDP may be a flawed measure of local incomes.

Data on such flows of repatriated earnings, which may result from tax avoidance or minimization strategies, are difficult to obtain. The European Union added the USVI to a list of "non-cooperative tax jurisdictions" in March 2018.17 The European Council, a body consisting of EU heads of government and senior EU officials, stated that jurisdictions added to the list "failed to make commitments at a high political level in response to all of the EU's concerns."18 The USVI government called that decision "unjustified."19 In October 2019, the European Council declined to remove the USVI from the list of noncooperative tax jurisdictions.20

With those caveats regarding GDP in mind, Figure 1 presents trends in per capita GDP from 2004 through 2015. Florida and Louisiana, which have both been affected by major hurricanes in that time period, are included for comparison. While USVI per capita GDP did not fall during the 2007-2009 Great Recession, it did drop sharply after the demise of the HOVENSA refinery.

Tourism

In recent years, tourism and related trade has been the predominant component of the economy of the Virgin Islands. In years before Hurricanes Irma and Maria, about 1.2 million cruise passengers and about 400,000 airplane passengers arrived each year.21 Virgin Islands tourist destinations compete with many other Caribbean destinations. Much of the growth in Caribbean tourism has taken place in all-inclusive resorts that rely on low-wage labor, such as in the Dominican Republic.22 Many hotels and resorts were seriously damaged or destroyed in the September 2017 hurricanes. Employment and tourist arrival data, discussed below, suggest the tourism sector has started to rebound, although that process could take years to complete.

Manufacturing

Manufacturing, which had played a major role in the Virgin Islands since the 1960s, now plays a minor economic role aside from two rum distilleries, which enjoy extensive public subsidies.23 Slightly more than 600 people were employed in manufacturing in 2015, mostly in small firms.24

Rum

The Cruzan distillery, which has a capacity to produce about 9 million proof gallons per year, claims a presence in the Virgin Islands since the mid-18th century. Cruzan was sold to Fortune Brands in 2008, after several changes in ownership.25 The Diageo distillery, which can produce some 20 million proof gallons per year, was built as part of a 2008 agreement with the territorial government.26 Diageo is a British multinational corporation specializing in the marketing of alcoholic beverages, which previously operated a distillery in Puerto Rico.27 A separate agreement between Cruzan and the USVI government was negotiated in 2009.28 In 2012, the USVI government agreed to modify the Cruzan agreement to increase subsidies, subject to set sales and marketing expense benchmarks.29

The agreements with the Virgin Islands Government and Diageo and Fortune Brands included an estimated $3.7 billion in subsidies and tax exemptions over 30 years, provided through proceeds of bonds that securitized "cover-over" excise taxes on rum sales rebated from the U.S. government and local tax abatements.30 The agreements also committed the USVI government to provide ongoing production and marketing subsidies paid from cover-over revenues. The agreement bars the USVI government from seeking reductions in rum subsidies.31 As noted above, federal excise taxes on rum imported into the United States from the USVI and Puerto Rico (PR), or from anywhere else, are "covered over" to the PR and the USVI governments.32

The HOVENSA Refinery and Limetree Bay

The HOVENSA oil refinery, mentioned above, had been one of the USVI's largest employers, with about 1,200 workers and nearly 1,000 contractors.33 Since 1998, the refinery operated as a joint venture between Hess Oil and Petróleos de Venezuela, a petroleum company owned by the Venezuelan government.34 The refinery suddenly shut down in 2012 after running large losses. While mainland refineries had shifted to natural gas as an energy source, the HOVENSA facility relied on relatively expensive fuel oil.35

HOVENSA filed for bankruptcy under chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code in September 2015.36 The USVI government received $220 million as part of the agreement to resolve HOVENSA's assets, which was used to cover the government's budget deficit for 2015.37 Limetree Bay purchased some HOVENSA facilities to build an oil storage facility that initially employed about 80 people and which later expanded to employ about 650 people.38

A renovation of the HOVENSA refinery complex was reportedly three-quarters complete in late 2019, potentially allowing fuel deliveries in early 2020.39

Agriculture

Over many decades, agriculture's role in the economy has dwindled to a marginal activity. Most of the island's food supply and essentially all of the molasses—a syrup extracted from sugar cane—used to produce rum is imported.

Energy and Water40

The high cost of electricity in the U.S. Virgin Islands is one factor that hinders economic development. Residential customers pay 40 cents per kilowatt/hour (kWh) or about three times the average cost on the mainland.41 Commercial electricity rates are approximately $0.47/kWh.42

Island power systems do not benefit from gas pipelines or electric grids that extend over large areas, thus face higher costs than mainland systems. U.S. Virgin Islands Water and Power Authority (VIWAPA) supplies electrical power and water. The bulk of power generation is fueled by oil and diesel, although initiatives to enable use of propane and natural gas have been under way.43 For instance, VIWAPA modified some electric generating units to allow them the option to use natural gas, propane, or fuel oil.44 Expanding the efficient use of renewable sources of electricity, such as wind and solar, may require upgrades in transmission and generation systems. In 2015, renewable sources made up 8% of VIWAPA's peak demand generating capacity.45

Public Finances

High Public Debt Levels Raise Concerns

Fiscal challenges facing the USVI government have intensified in recent years. Several news reports in 2017 posed pointed questions about the sustainability of the islands' public debts, which total about $2 billion.46 Those debt levels, on a per capita or on a percentage of GDP basis, are extremely high compared to other subnational governments in the United States. In addition, the most recent actuarial analysis of public pensions found a net pension liability of about $4 billion.47 In 2017, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that "more than a third of USVI's current bonded debt outstanding as of fiscal year 2015 was issued to fund government operating costs."48 A 2019 GAO report noted that the USVI government had been shut out of capital markets since 2017, which could hobble its ability to roll over maturing debt. The report also summarized concerns with the solvency of the public pension system, growth prospects, effects of 2017 changes in the federal tax law, 49 and the uncertain status of federal Medicaid funding.50

Concerns about debt levels had led each of the three major credit ratings agencies to downgrade at least part of the islands' public debts.51 Others suggested that USVI's public debts would have to be restructured.52 In August 2017, then-Governor Mapp said that communications with credit ratings agencies had been suspended, which prompted those agencies to drop USVI's credit ratings.53

The U.S. Virgin Islands and other U.S. territories are not covered by the provisions of the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA; P.L. 114-187).54 Nonetheless, some credit ratings agencies saw enactment of PROMESA as a sign that Congress and the President could enact future legislation to enable debt adjustments in other territories.55

USVI Fiscal Responses

Like many state governments, USVI public revenues were severely affected by the 2007-2009 Great Recession. Tourism, the mainstay of the USVI economy, was affected. In turn, government revenues, typically closely tied to economic activity, also fell. In addition, rum subsidy payments doubled from 2006 to 2007 and 2008.56 As noted above, the closure of the HOVENSA refinery in 2012 resulted in hundreds of lost jobs and a significant contraction of the USVI tax base.

In recent years, the islands' government has run structural deficits and has used bond proceeds to cover shortfalls.57 Kenneth Mapp, who was inaugurated as governor in January 2015, had proposed various fiscal measures intended to reduce or eliminate those deficits. In August 2016, the islands' government took steps to issue bonds, which were to be used to cover financing shortfalls for its FY2017 budget. That issue was postponed until January 2017 and then cancelled.58 The loss of access to capital markets at reasonable rates left the islands' government with a narrow set of liquidity resources.59

In January 2017, then-Governor Mapp proposed a series of measures intended to strengthen public finances, including certain tax increases, enhanced revenue collection measures, and reductions in public spending.60 A package of tax measures, including higher taxes on beer, liquor, sodas, and timeshare rentals, which were part of the governor's proposals, was enacted on March 22, 2017.61 GAO, in an analysis of debts of U.S. territories, expressed doubts that those fiscal measures would restore access to capital markets or address shortfalls in the funding of public pensions and other retirement benefits.62

Then-Governor Mapp also had announced that a $40 million revenue anticipation note would soon be issued through Banco Popular, which he contended would provide the USVI government with liquidity through September 2017.63 It appears that issuance was also suspended.64 The form of USVI's public debt service, in which many funds are routed through escrow accounts before reaching government coffers, also limits options for USVI policymakers.

Governor Albert Bryan Jr., who succeeded Mapp in January 2019, claimed to have stabilized government operations and finances in his first year in office, including by taking steps to reestablish relations with credit rating agencies and enhance transparency of public finances.65

Aftermath of Hurricanes Irma and Maria

The USVI was hit by two powerful hurricanes in September 2017, which caused extensive damage from which island residents are continuing to recover. Hurricane Irma—shown in Figure 2—was "one of the strongest and costliest hurricanes on record in the Atlantic basin."66 Irma passed directly over St. Thomas and St. John on September 6, 2017, causing "widespread catastrophic damage."67

|

|

Source: Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere, using NOAA GOES-16 satellite imagery. Notes: Hurricane Irma made landfall in the British Virgin Islands northwest of St. John and St. Thomas. The storm's center passed about 50 nautical miles north of San Juan, Puerto Rico. National Hurricane Center, Hurricane Irma: 30 August—12 September 2017, AL112017, May 30, 2018, p. 3. |

Two weeks later, on September 20, Hurricane Maria hit St. Croix, before continuing on to devastate Puerto Rico.68 Figure 3 shows paths and zones of extreme wind speeds for both hurricanes in the vicinity of USVI. In November 2017, the USVI government estimated that uninsured damage from the hurricanes would exceed $7.5 billion.69

Disaster Responses

Disaster declarations following Hurricane Irma70 and Hurricane Maria71 enabled the USVI government and its residents to receive federal assistance through various provisions of the Stafford Act (P.L. 93-288, as amended).72 Those declarations authorized the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to assist local and territory governments, certain private nonprofit organizations, and individuals through grants, loans, and direct aid. FEMA, the U.S. Corps of Engineers, and the U.S. Coast Guard, among other federal agencies, also directly supported disaster response and recovery efforts.

Other forms of federal disaster assistance have included loans and grants to individuals and small businesses, including through the Small Business Administration disaster loan program. The USVI government and two hospital authorities received Community Disaster Loans (CDLs) on January 3, 2018. The USVI government CDL totaled $10 million with a term of 20 years.73 CDLs were designed to provide liquidity to local governments that have suffered revenue declines due to disasters.74 Estimates based on USVI fiscal data suggest that public revenues were halved after the two hurricanes.75

Disaster Funding

Funding for disaster relief has been augmented by several supplemental appropriations.76 The extent of federal disaster assistance received by the USVI will depend, in part, on how funds provided in response to needs resulting from hurricanes and fires in 2017 are allocated among affected areas.

In the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123; §20301), enacted on February 9, 2018, Congress provided the USVI and Puerto Rico with additional Medicaid funding for the period January 1, 2018, through September 30, 2019. For the USVI Medicaid program, an additional $107 million was provided. Another $35.6 million would be available to the USVI subject to certain Medicaid program integrity and statistical reporting requirements. The federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) was also raised from 55% to 100% for both the USVI and Puerto Rico Medicaid programs during that interval.77

On February 4, 2020, House Appropriations Chairwoman Nita M. Lowey introduced H.R. 5687, an emergency supplemental appropriations bill. Title B of the measure includes provisions that would provide additional resources to territories, including the USVI, through support for child tax credits (and certain expansions of eligibility) and other tax credits, as well as a relaxation on limits on rum cover-over revenues directed to Puerto Rico and USVI. The House passed the measure on February 7, 2020, on a 237-161 vote. The Administration warned it would veto the measure.78

VIWAPA Financial Woes Hinder Recovery from Hurricane Damage

Hurricanes Irma and Maria damaged an estimated 80% to 90% of VIWAPA's transmission and distribution lines, although power-generating plants were less affected. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) estimated that 93% of total USVI customers had their electric power restored by the end of January 2018.79 According to the U.S. Virgin Islands action plan submitted to and approved by HUD, the energy sector infrastructure needs as a result of the hurricanes totaled nearly $2.3 billion.80

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) allocated $67.7 million (approximately 3%) to the U.S. Virgin Islands from a $2 billion Community Development Block Grant-Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) appropriation included in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123) "to provide enhanced or improved electrical power systems" for Puerto Rico and the USVI.81 Governor Bryan reportedly asked HUD to "acknowledge that the Virgin Islands needs at least $350 million of these funds to make a meaningful impact in strengthening the grid and lowering the high cost of electricity in the Virgin Islands."82

On September 16, 2019, $774 million in mitigation funds (CDBG-MIT funds) were allocated to the U.S. Virgin Islands; however, HUD announced that

[T]he grantee is prohibited from using CDBG-MIT funds for mitigation activities to reduce the risk of disaster related damage to electric power systems until after HUD publishes the Federal Register notice governing the use of the $2 billion for enhanced or improved electrical power systems. This limitation includes a prohibition on the use of CDBG-MIT funds for mitigation activities carried out to meet the matching requirement, share, or contribution for any Federally-funded project that is providing funds for electrical power systems until HUD publishes the Federal Register notice governing the use of CDBG-DR funds to provide enhanced or improved electrical power systems.83

The prohibition on the use of CDBG-MIT funds combined with VIWAPA's cash flow challenges limits VIWAPA's ability to improve resiliency. Without sufficient available funds, VIWAPA is unable to meet federal funding matching requirements in order to make use of eligible mitigation funding from FEMA to permanently harden the electrical power systems.84

The government of the U.S. Virgin Islands—VIWAPA's largest customer—has been slow in providing payment for services. The UVSI legislature, however, moved to appropriate $22.2 million for hospitals to pay outstanding obligations to VIWAPA, among other provisions.85

Throughout 2018 and 2019, USVI policymakers expressed concerns over VIWAPA's financial stability. For instance, Delegate Stacey Plaskett called on Governor Bryan and USVI Senate President Francis to declare a state of emergency in response to the territory's "energy crisis."86

FY2019 Budget Proposals

In his FY2019 budget proposals, Governor Mapp set forth plans to extend the solvency of the USVI public pension systems.87 According to those proposals, the projected insolvency of those plans would be postponed from 2024 to 2025.88 Additional measures, to be outlined in the future, were claimed to suffice to postpone insolvency for three additional years. The FY2019 budget proposals also called for a lifting of a hiring freeze. Additional revenues were expected from expanded federal reimbursement for health programs, along with recovery-related investment activity, although decreased tourist traffic is expected to keep accommodation tax and related collections well below prehurricane levels in FY2019.

Economic Prospects

The USVI economy has relied heavily on tourism and related business activity, which made it more vulnerable to the effects of hurricanes than jurisdictions with more diverse economies.

Employment Trends

Figure 4 shows employment trends in the tourism-dependent leisure and hospitality sector, the territorial government, the manufacturing sector, and the construction sector.89

Employment in the leisure and hospitality sector shows a steep decline after Hurricane Marilyn in 1995 and after Hurricanes Irma and Maria in September 2017, after which employment in that sector was halved.90 Leisure and hospitality employment took about six years to recover to pre-Marilyn levels. Increases in the construction sector offset about half of those losses in 1996 and 1997, presumably due to recovery and reconstruction work. As of December 2019, tourism sector employment has recovered somewhat, but remains well below pre-2017 levels.

Construction employment also rose in 2018 and 2019, but that uptick appears much smaller than in the post-Marilyn time period. Moreover, the posthurricane increases in construction-related activity have been small relative to the loss of tourism employment after 2017.

Employment in the USVI territorial government declined over the 2010-2014 period, but has remained relatively stable since then.

Tourism Trends

The severity of damage from Irma and Maria, and the subsequent disruption of the USVI tourism industry, suggest that a full economic recovery could take years. Many hotels have remained closed since the hurricanes, although some reopened in 2019.91 Cruise ship passenger arrivals fell from 1.8 million in calendar year (CY) 2016 to 1.3 million in 2017, but have rebounded somewhat. Air passenger arrivals fell from nearly 800,000 in 2016 to less than 500,000 in 2018. Air arrivals for the first three quarters of CY2019 ran 44% ahead of the same period in 2018.92

Unemployment Claims

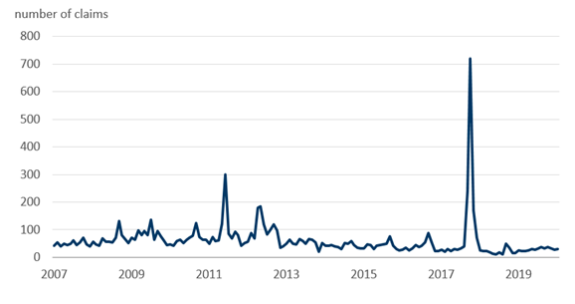

The economic effects of Hurricanes Irma and Maria can also be seen in initial unemployment claims data, shown in Figure 5. The post-Irma and Maria uptick in late 2017 is more than twice the size of the 2011-2012 upticks near the time of the closure of the HOVENSA refinery.

The New York Federal Reserve Bank compared the economic effects of Hurricanes Irma and Maria on the USVI and Puerto Rico, noting that the estimated percentage job loss following those hurricanes (-7.8%) was far greater than the percentage job losses in New York City (-3.3%) during the Great Recession.93

Researchers report that many young professionals and health care workers have left the USVI for positions on the mainland, which may complicate recovery efforts in the health care sector.94

Tracking the progress of USVI economic recovery is complicated as many federal statistical programs report fewer data series for U.S. territories than for states.95 The Virgin Islands Bureau of Economic Research (VIBER), however, reports regularly on economic, tourism, and population trends.

|

Figure 5. USVI Initial Unemployment Claims, 2007-2020 (Monthly Data) |

|

|

Source: U.S. Employment and Training Administration, Initial Claims in U.S. Virgin Islands [VIRICLAIMS]. Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/VIRICLAIMS. |

Considerations for Congress

The fiscal and economic challenges facing the USVI government raise several issues for Congress. First, Congress may consider further legislation that would extend or restructure long-range disaster assistance programs to mitigate those challenges and promote greater resiliency of infrastructure and public programs.

Second, if fiscal pressures on the USVI intensify, Congress might consider a framework similar to that established by the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA; P.L. 114-187). In the past, however, USVI policymakers opposed making PROMESA provisions available to other territories because of concerns about borrowing costs.96 At present, the USVI lacks access to the federal Bankruptcy Code or other processes for debt restructuring involving judicial processes.

Third, Congress might consider proposals to support initiatives to lower energy costs for the USVI. Mainland electrical power generation, to a large extent, has shifted to using more natural gas as a fuel.97 Construction of a liquefied natural gas (LNG) import facility and accompanying generation plants could lead to lower energy prices and an enhanced capacity to employ renewable energy sources. Other innovative energy technologies might also be used to that end. While VIWAPA has taken some steps to modernize its generating units, some major investments may be required. For example, construction of a LNG facility and further conversions of generating units could lower electricity rates, but would require financial commitments that would likely challenge the fiscal capacity of the USVI government and VIWAPA. Moreover, LNG supply contracts typically extend over decades due to the scale of required investments, arrangements which could be difficult to negotiate given the USVI's fiscal situation.

Fourth, Congress may expand oversight of federal agencies that administer disaster assistance programs, including FEMA and HUD, to ensure the timely receipt of assistance by grantees. Several Members of Congress have expressed concerns that funds for federal disaster recovery efforts have been unduly delayed. Congress could also examine the interplay among federal agencies, federal rules and regulations that apply to disaster responses operations, and local governments and nonprofits in affected areas.

Fifth, Congress may revisit the structure of the rum cover-over program to assess whether its current structure is appropriately fitted to public purposes. The contractual bar to USVI advocacy of changes in the cover-over program could require Congress to initiate any such alterations.

Sixth, Congress may choose to promote economic and social development through a wide range of tax and social program rules, some of which treat USVI differently than states.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Martín Fernández de Navarrete, Colección de los Viages y Descubrimientos que hicieron por Mar los Españoles desde Fines del Siglo XV [Collection of the Voyages and Discoveries Made by the Spaniards since the Late 15th Century] (Madrid: Imprensa Real, 1825), v. I, pp. 208. "…eran mas de cuaranta y tantos islones, tierra muy alta, é la mas della pelada, la cual no era ninguna ni es de las que antes ni despues habemos visto." For an assessment of the legend of St. Ursula, see Ben Johnson, "Saint Ursula and the 11,000 British Virgins," Historic UK, https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Saint-Ursula-the-11000-British-Virgins/. |

| 2. |

Clarence H. Haring, Buccaneers in the West Indies in the XVII Century (London: Meuthen, 1910), ch. 1-2 and pp. 235-236, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/19139/19139-h/19139-h.htm. |

| 3. |

Niklas Thode Jensen and Gunvor Simonsen, "Introduction: The Historiography of Slavery in the Danish-Norwegian West Indies, c. 1950-2016," Scandinavian Journal of History, vol. 41 (2016), no. 4-5, pp. 475-494. |

| 4. |

Frank Moya Pons, History of the Caribbean (Markus Wiener: Princeton, NJ, 2007), pp. 126-127. |

| 5. |

Isaac Dookhan, A History of the Virgin Islands of the United States (Canoe Press: Jamaica, 1994), pp. 175-179. |

| 6. |

Ibid., ch. 13. Also see Roy A. Ballinger, "A History of Sugar Marketing through 1974," U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economics, Statistics, and Cooperatives Service, 1978, https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/40532/50517_aer382a.pdf?v=42069. |

| 7. |

James Brown Scott, "The Purchase of the Danish West Indies by the United States of America," American Journal of International Law, vol. 10, no. 4, October 1916, pp. 853-859, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2186936. Some alleged that Senator Sumner, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, opposed annexation of the islands out of enmity toward Secretary of State William Seward and his support for President Andrew Johnson during impeachment proceedings (see Department of State web page cited below). Contemporary observers, however, pointed to extensive evidence that Sumner, who became a forceful proponent of the Alaska purchase, opposed acquiring the Danish islands on substantive grounds. See Edward L. Pierce, Memoir and Letters of Charles Sumner (Boston: Roberts Bros., 1893), vol.4 (1829-1897), pp. 328-330. |

| 8. |

U.S. Department of State, Purchase of the U.S. Virgin Islands, 1917, archived web page, https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/wwi/107293.htm. |

| 9. |

The first civilian governor, Paul Pearson, wrote in his first report that "[t]he change of administration was made for the purpose of undertaking a rehabilitation program which would remedy the desperate economic condition of the Virgin Islands, help its citizens to earn a livelihood, and gradually decrease the annual deficit which the Islands had incurred and which Congress each year has been forced to make up." Report of the Virgin Islands Governor, August 31, 1931, http://historycms.house.gov/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=15032434334. |

| 10. |

Dookhan, op. cit., pp. 265-272. Executive Order 5566, President Herbert Hoover, February 27, 1931, https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/migrated/oia/about/upload/Executive-Order-5566.pdf. |

| 11. |

Dookhan, op. cit., p. 287; and U.S. Virgin Islands Bureau of Economic Research, Economic Review, May 2016, http://www.usviber.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Economic-Review-May-2016.pdf. |

| 12. |

Dookhan, op. cit., p. 287; and St. Croix Renaissance Group, "St. Croix Renaissance Park," website, http://www.stxrenaissance.com/about.html. |

| 13. |

S&P Global Platts, "HOVENSA Refinery, Once World's Largest, Likely to Remain Shut," January 18, 2013, https://www.platts.com/latest-news/oil/houston/feature-hovensa-refinery-once-worlds-largest-6047570. |

| 14. |

For details, see CRS Report R41028, The Rum Excise Tax Cover-Over: Legislative History and Current Issues, by Steven Maguire. Some degree of self-governance was granted by the 1936 Organic Act (P.L. 74–749), which among other provisions shifted formulation of economic strategies to the residents of the Virgin Islands. |

| 15. |

U.S. Census Bureau, DP03: Selected Economic Characteristics: 2009 for USVI and the United States. The Eastern Caribbean Center at the University of the Virgin Islands, in its 2013 community survey, estimated median household income in the USVI as $31,098. Former U.S. Census Bureau experts advised survey administrators, but how that estimate compares with decennial census estimates is difficult to determine. |

| 16. |

See Justyna Goworowska and Steven Wilson, Recent Population Trends for the U.S. Island Areas: 2000 to 2010, U.S. Census Bureau, Report P23-213, April 8, 2015, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p23-213.pdf. |

| 17. |

European Council and the Council of the European Union, "Taxation: Three Jurisdictions Removed, Three Added to EU List of Non-Cooperative Jurisdictions," web page, March 13, 2018, http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2018/03/13/taxation-3-jurisdictions-removed-3-added-to-eu-list-of-non-cooperative-jurisdictions. |

| 18. |

Ibid. |

| 19. |

"VI Government Calls EU's Blacklisting of Territory As Tax Haven 'Unjustified'," Virgin Islands Consortium, March 13, 2018, http://viconsortium.com/business/vi-government-calls-eus-blacklisting-of-territory-as-tax-haven-unjustified/. |

| 20. |

European Council and the Council of the European Union, "Taxation: 2 Countries Removed from List of Non-Cooperative Jurisdictions, 5 Meet Commitments," press release, October 10, 2019, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2019/10/10/taxation-2-countries-removed-from-list-of-non-cooperative-jurisdictions-5-meet-commitments/. |

| 21. |

U.S. Virgin Islands Bureau of Economic Research, Economic Review, p. 3, May 2016, http://www.usviber.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Economic-Review-May-2016.pdf. |

| 22. |

Anne O. Krueger, Ranjit Teja, and Andrew Wolfe, Puerto Rico: A Way Forward, June 29, 2015. |

| 23. |

Bill Kossler, "V.I. Budget Crisis Part 5: Weren't Rum Funds Supposed to Save Us?" St. John Source, May 8, 2017, https://stjohnsource.com/2017/05/08/v-i-budget-crisis-part-5-werent-rum-funds-supposed-to-save-us/. |

| 24. |

Economic Review, op. cit. p. 3. |

| 25. |

Business Wire, "Fortune Brands Receives Cash Payment from Pernod Ricard and Acquires Cruzan Rum Brand," August 28, 2008, http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20080828005964/en/Fortune-Brands-Receives-Cash-Payment-Pernod-Ricard. In 2017, Diageo reported total sales of $22.3 billion (£18.1 billion) and profits of $3.4 billion (£2.8 billion). Rum—produced in USVI and elsewhere—accounted for 7% of Diageo's net sales. See Diageo 20-K Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filing for year ended June 30, 2017, https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/835403/000119312517250792/d374393d20f.htm. |

| 26. |

The agreement was approved by Act 7012 of 2008, enacted July 11, 2008. The agreement is available as an appendix here: http://www.legvi.org/vilegsearch/ShowPDF.aspx?num=7012&type=Act. |

| 27. |

PR News Wire, "Virgin Islands Governor John de Jongh Announces Landmark Initiative with Diageo for Captain Morgan Rum Distillery on St. Croix," June 23, 2008. |

| 28. |

Appendix E of Official Statement for Virgin Islands Public Finance Authority, Subordinated Revenue Bonds, Cruzan Project, Series 2009A, December 8, 2009, http://www.usvipfa.com/PDF/OS/CruzanProject2009.pdf. |

| 29. |

Act 7362 of 2012, enacted April 25, 2012. The revised contract is available as an appendix here: http://www.legvi.org/vilegsearch/ShowPDF.aspx?num=7362&type=Act. |

| 30. |

Jack Lyne, "Yo Ho Ho and Billion-Dollar Bottles of Rum," 2009, http://siteselection.com/ssinsider/incentive/Billion-Dollar-Bottles-of-Rum.htm. Also see CRS Report R41028, The Rum Excise Tax Cover-Over: Legislative History and Current Issues, by Steven Maguire. The Diageo agreement is available as Appendix B at http://www.usvipfa.com/PDF/OS/Diageo2009.pdf. |

| 31. |

See Virgin Islands Public Finance Authority, Official Statement, Subordinated Revenue Bonds, Virgin Islands Matching Fund Loan Note—Diageo Project, Series 2009A, Appendix B, clause 4.1.4, at http://www.usvipfa.com/PDF/OS/Diageo2009.pdf. Section 7.3.4 of the 2009 Cruzan agreement (op. cit.) specifies that "(t)he Government agrees to use reasonable efforts to strenuously oppose any proposed legislation, initiative, act, event, plan or proposal which would otherwise have the effect of voiding or reducing any of the obligations or commitments as set forth in this Agreement." |

| 32. |

CRS Report R41028, The Rum Excise Tax Cover-Over: Legislative History and Current Issues, by Steven Maguire. |

| 33. |

Jason Bronis, "HOVENSA LLC to Shut Virgin Islands Oil Refinery Owned by Hess Corp. and Venezuela's PDVSA," Associated Press, January 18, 2012. |

| 34. |

The name appears to derive from Hess Oil and Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. See Hess Corporation, History of Hess Corporation, website, at http://www.hess.com/company/hess-history. |

| 35. |

S&P Global Platts, "HOVENSA Refinery, Once World's Largest, Likely to Remain Shut," January 18, 2013, https://www.platts.com/latest-news/oil/houston/feature-hovensa-refinery-once-worlds-largest-6047570. |

| 36. |

In re HOVENSA LLC, Voluntary Petition, Case 1:15-bk-10003-MFW, September 15, 2015. Also see Governor John de Jongh, "Economic Impact of the HOVENSA Closing," presentation to a federal interagency meeting, February 24, 2012, https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/migrated/oia/igia/2012/upload/26-Special-USVI-Report-on-Economic-Impact-of-HOVENSA-Closing-2-24-12.pdf. |

| 37. |

Economic Review, op. cit. p. 4. |

| 38. |

Governor Kenneth Mapp, State of the Territory Message, January 22, 2018, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1_-zu9pWaWkKVTjPoSNcMGn85x6n0JRlJ/view. |

| 39. |

Gary McWilliams, "Restart of Idled St. Croix Oil Refinery Set for Early 2020 After Delay," Reuters, November 7, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-refinery-virginislands/restart-of-idled-st-croix-oil-refinery-set-for-early-2020-after-delay-idUSKBN1XH2CL. |

| 40. |

This material draws on products authored by Corrie E. Clark and Richard J. Campbell. |

| 41. |

Residential customers pay $0.40 per kilowatt-hour (kWh) for the first 250 kWh and $0.43/kWh above that threshold. |

| 42. |

Rates reported by VIWAPA are approved by the Public Services Commission of the Virgin Islands. See VIWAPA, "Electric Rate," July 1, 2019, http://www.viwapa.vi/customer-service/rates/electric-rate. Also see U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information Agency (EIA), "U.S. Virgin Islands Territory Profile and Energy Estimates," January 16, 2020, https://www.eia.gov/state/?sid=VQ. The EIA reports that commercial rates for the United States averaged 10.6 cents per kWh. EIA, Electric Power Monthly, Table 5.6, January 27, 2020, https://www.eia.gov/electricity/monthly/epm_table_grapher.php?t=epmt_5_6_a. |

| 43. |

Ibid. and Economic Review, op. cit. p. 2. |

| 44. |

See CRS Report R45105, Potential Options for Electric Power Resiliency in the U.S. Virgin Islands, by Corrie E. Clark, Richard J. Campbell, and D. Andrew Austin, at pp. 11 and 23. |

| 45. |

Ibid., Table 1. |

| 46. |

For example, see Simone Baribeau, "United States Virgin Islands Risks Capsizing Under Weight of Debt," Forbes, January 23, 2017; and "Welcome to the Virgin Islands: One of the Most Indebted Places in the US," Wall Street Journal, January 26, 2017. A Moody's estimate put total debt at $1.97 billion: see Moody's Investor's Service, Credit Opinion: U.S. Virgin Islands (Government of), January 24, 2017. |

| 47. |

Virgin Islands Retirement System (GERS) Retirement Board, Government of the Virgin Islands Retirement System Actuarial Valuation and Review as of October 1, 2015, August 8, 2016, http://www.usvigers.com/Libraries/Administration_Documents/FINAL_-_GERS_FY_2015_Audited_Financial_Statements.sflb.ashx. |

| 48. |

GAO, U.S. Territories: Public Debt Outlook, GAO-18-160, October 2, 2017, https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-160. |

| 49. |

Federal tax legislation generally treats corporations in territories as foreign entities. Provisions of the 2017 changes include significant modification of the treatment of foreign corporations, which could affect some parts of the USVI economy. See CRS Report R45186, Issues in International Corporate Taxation: The 2017 Revision (P.L. 115-97), by Jane G. Gravelle and Donald J. Marples. |

| 50. |

GAO, U.S. Territories: Public Debt Outlook 2019 Update, GAO-19-525, June 2019, https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-19-525. |

| 51. |

A listing of credit ratings agency announcements can be found at the Electronic Municipal Market Access website, http://emma.msrb.org. |

| 52. |

Bill Kossler, "Analysts Worry USVI Following Puerto Rico's Path," VI Source, January 17, 2017, https://stjohnsource.com/2017/01/17/analysts-worry-usvi-following-puerto-ricos-path/. |

| 53. |

Ernice Gilbert, "Mapp Says VI Government Has Cut Ties with Ratings Agencies," Virgin Islands Consortium, August 23, 2017. |

| 54. |

PROMESA does include a provision to cover other territories in the event that a final judicial order would otherwise nullify the act on uniformity grounds. |

| 55. |

Fitch Ratings, "Fitch Places U.S. Virgin Islands and Guam's Ratings on Rating Watch Negative," press release, July 6, 2016. |

| 56. |

Rum subsidies increased from $9.3 million in 2006 to $20.2 million in 2007 and $18.7 million in 2008. See Virgin Islands Public Finance Authority, Official Statement, Subordinated Revenue Bonds, Virgin Islands Matching Fund Loan Note—Diageo Project, Series 2009A, p. 46, http://www.usvipfa.com/PDF/OS/Diageo2009.pdf. |

| 57. |

Bill Kossler, "The V.I. Budget Crisis: How Did We Get Here, How Do We Get Out?" St. Thomas Source, April 10, 2017, http://stthomassource.com/content/2017/04/10/the-v-i-budget-crisis-how-did-we-get-here-how-do-we-get-out/. |

| 58. |

Moody's Investor's Service, Credit Opinion: U.S. Virgin Islands (Government of), January 24, 2017; and Fitch Ratings, "Fitch Downgrades U.S. Virgin Islands IDR and Rev Bonds; Ratings on Negative Watch," January 17, 2017. |

| 59. |

GAO, U.S. Territories: Public Debt Outlook, GAO-18-160, p. 54, October 2, 2017. |

| 60. |

Virgin Islands Consortium, "Facing Liquidity Crisis, Mapp Formally Submits Proposed 'Sin' Tax Measure To Senate Aimed At Curtailing Incessant Borrowing," January 24, 2017. Also see Fitch Ratings, "Fitch Downgrades U.S. Virgin Islands IDR and Rev Bonds; Ratings on Negative Watch," January 17, 2017. |

| 61. |

"An Act to Enhance Revenues ..." (Bill 32-0005; Act 7987), http://www.legvi.org/vilegsearch/Detail.aspx?docentry=25084. Also see Governor Kenneth Mapp, Proposed Budget for FY2018 for the Government of the Virgin Islands of the United States, July 20, 2017, https://dof.vi.gov/sites/default/files/docs/FY%202018%20Executive%20Budget%20Book%20Final.pdf. |

| 62. |

GAO, U.S. Territories: Public Debt Outlook, GAO-18-160, pp. 55-56, October 2, 2017. |

| 63. |

James Gardner, "Not Willing to Take a Pay Cut, Mapp Says Government Will Have Funds Through September," St. Thomas Source, April 17, 2017, http://stthomassource.com/content/2017/03/23/not-willing-to-take-a-pay-cut-mapp-says-government-will-have-funds-through-september/. |

| 64. |

No such security appears on the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board's EMMA website (http://emma.msrb.org/). |

| 65. |

Governor Albert Bryan Jr., "State of the Territory Address," January 13, 2020, https://www.vi.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/State-of-the-Territory.pdf. Also see Robert Moore, "State of the Territory: Bryan Extols Successes of His First Year, Proclaims Territory on the Right Track," Virgin Islands Consortium, January 14, 2020, https://viconsortium.com/vi-politics/virgin-islands-the-state-of-the-territory-gov-bryan-extols-the-successes-of-his-first-year-proclaims-the-territory-on-the-right-track. |

| 66. |

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Hurricane Center, Hurricane Irma, Tropical Cyclone Report AL112017, March 9, 2018, p. 1, https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL112017_Irma.pdf. |

| 67. |

Ibid., p. 14. |

| 68. |

Richard J. Pasch, Andrew B. Penny, and Robbie Berg, Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Maria (AL152017) 16–30 September 2017, National Hurricane Center, April 10, 2018, https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL152017_Maria.pdf. |

| 69. |

Testimony of Governor Kenneth Mapp, in U.S. Congress, House Committee on Natural Resources, The Need for Transparent Financial Accountability in Territories' Disaster Recovery Efforts, hearings, 115th Cong., 1st sess., November 17, 2017, http://docs.house.gov/meetings/II/II00/20171114/106587/HHRG-115-II00-Wstate-MappK-20171114.pdf. |

| 70. |

Federal Emergency Management Agency, Virgin Islands Hurricane Irma (DR-4335), disaster declared September 7, 2017, https://www.fema.gov/disaster/4335. |

| 71. |

Federal Emergency Management Agency, Virgin Islands Hurricane Maria (DR-4340), disaster declared September 20, 2017, https://www.fema.gov/disaster/4340. |

| 72. |

See CRS Report R41981, Congressional Primer on Responding to Major Disasters and Emergencies, by Bruce R. Lindsay and Elizabeth M. Webster. Also see CRS Insight IN10810, Natural Disasters of 2017: Congressional Considerations Related to FEMA Assistance, coordinated by Jared T. Brown. |

| 73. |

USVI CDL contract is available at https://emma.msrb.org/ES1087705-ES849717-ES1250894.pdf. |

| 74. |

See CRS Report R42527, FEMA's Community Disaster Loan Program: History, Analysis, and Issues for Congress, by Jared T. Brown. Also see CRS Insight IN11106, Community Disaster Loans: Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress, by Michael H. Cecire. |

| 75. |

Bill Kossler, "The V.I. Budget Crisis, Part 16: Irma and Maria Make a Bad Situation Worse," St. John Source, December 25, 2017, https://stjohnsource.com/2017/12/25/the-v-i-budget-crisis-part-16-irma-and-maria-make-a-bad-situation-worse/. FY2017 revenues were just below $700 million, while estimated FY2018 revenues were just above $300 million. |

| 76. |

See CRS Report R45084, 2017 Disaster Supplemental Appropriations: Overview, by William L. Painter. |

| 77. |

For background on FMAP rates, see CRS Report R43847, Medicaid's Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP), by Alison Mitchell. |

| 78. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB), Statement of Administration Policy: H.R. 5687—Emergency Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief and Puerto Rico Disaster Tax Relief Act, 2020, February 5, 2020, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/SAP_HR-5687.pdf. |

| 79. |

Ibid. |

| 80. |

Of the $2.3 billion, less than $400 million had been obligated at the time of the Community Development Block Grant-Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) funding request; see USVI Housing Finance Authority, Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery Program Action Plan, FR 6066-N-01, July 10, 2018, p. 58. According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), as of July 20, 2018, FEMA had obligated approximately $795 million for the USVI for direct federal assistance through mission assignments and Public Assistance grant funds for electricity restoration, and FEMA had provided $75 million to VIWAPA through the Community Disaster Loan program. See GAO, 2017 Hurricane Season: Federal Support for Electricity Grid Restoration in the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico, GAO-19-296, April 18, 2019, pp. 11-12, https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/698626.pdf. |

| 81. |

See data on grant B-18-DE-78-0001 at https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/cdbg-dr/cdbg-dr-grantee-contact-information/#all-disasters. |

| 82. |

Government House of the U.S. Virgin Islands, "Governor Bryan Working with HUD Secretary Ben Carson on Increased Funding for Electric Grid, Other Improvements Under CDBG-DR," press release, April 17, 2019. |

| 83. |

HUD, "Allocations, Common Application, Waivers, and Alternative Requirements for Community Development Block Grant Mitigation Grantees; U.S. Virgin Islands Allocation," 84 Federal Register 47528, September 10, 2019. The HUD Community Planning and Development, Community Development Fund section of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123) includes deadlines for the allocation of CDBG-MIT funds, but not for the Federal Register notices detailing how the funds may be used. It states, "That of the amounts made available under the second and fourth provisos of this heading, the Secretary shall allocate to all such grantees an aggregate amount not less than 33 percent of each such amounts of funds provided under this heading within 60 days after the enactment of this subdivision based on the best available data (especially with respect to data for all such grantees affected by Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria), and shall allocate no less than 100 percent of the funds provided under this heading by no later than December 1, 2018 [emphasis added]." The second proviso referred to states, "That of the amounts made available under this heading, up to $16,000,000,000 shall be allocated to meet unmet needs for grantees that have received or will receive allocations under this heading for major declared disasters that occurred in 2017 or under the same heading of Division B of P.L. 115-56, except that, of the amounts made available under this proviso, no less than $11,000,000,000 shall be allocated to the States and units of local government affected by Hurricane Maria, and of such amounts allocated to such grantees affected by Hurricane Maria, $2,000,000,000 shall be used to provide enhanced or improved electrical power systems [emphasis added]." CRS was not able to identify any congressionally mandated deadlines related to HUD's issuance of a Federal Register notice for the CDBG-MIT funds for the U.S. Virgin Islands' electrical power system. Due to the complexity of legislation and publications related to the CDBG-DR and CDBG–MIT programs, however, it is possible that the search conducted by CRS was not comprehensive. |

| 84. |

Office of the Governor-Elect of the United States Virgin Islands, "WAPA Transition Cluster Report," December 21, 2018, https://stjohnsource.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2019/10/WAPA-Cluster-Report.pdf, p. 13. |

| 85. |

April Knight, "Rules Panel Approves Tabled Medicaid Windfall Bill," The St. John Source, June 25, 2019, https://stjohnsource.com/2019/06/25/rules-panel-approves-tabled-medicaid-windfall-bill/. |

| 86. |

Letter from Delegate Stacey E. Plaskett to Governor Albert Bryan and Senate President Novelle Francis, September 18, 2019, https://assets.sourcemedia.com/08/e5/c0e026694577987b312117b23db5/09-18-19-letter-from-delegate-to-gov-and-senate-president.pdf. |

| 87. |

Robert Slavin, "Virgin Islands Proposes Steps to Help Pension System," Bond Buyer, June 1, 2018. The USVI Executive FY2019 budget proposals, submitted to the USVI Legislature on May 30, 2018, are available through links in this web page: https://www.vi.gov/fy-2019-spending-plan-includes-provisions-to-stabilize-retirement-system-provide-salary-increases-and-merge-hospital-operations/. |

| 88. |

Bill Kossler, "Mapp's 2019 Budget Expects Big Returns From Rebuilding," St. Thomas Source, June 1, 2018, https://stthomassource.com/content/2018/06/01/mapps-2019-budget-expects-big-returns-from-rebuilding/. |

| 89. |

The official category is "mining, logging, and construction." USVI, however, has no significant employment in the mining and logging industries. |

| 90. |

See U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Weather Service, Natural Disaster Survey Report Hurricane Marilyn September 15-16, 1995, January 1996, https://www.weather.gov/media/publications/assessments/marilyn.pdf. |

| 91. |

Virgin Islands Consortium, "Frenchman's Reef Marriott Resort, Sugar Bay, to Remain Closed For Repairs Until 2019; Ritz-Carlton Through Oct. 2018," October 19, 2017. Also see Emily Palmer, "Caneel Bay: Why a Caribbean Paradise Remains in Ruins: Two Years After Back-to-Back Hurricanes Struck St. John, the Famed Caneel Bay Resort has not Reopened," New York Times, January 20, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/20/travel/st-john-caneel-bay-resort.html. |

| 92. |

USVI Bureau of Economic Research (VIBER), Cruise Passenger Arrivals, various issues. Also see VIBER, Air Visitor Arrivals, various issues. |

| 93. |

New York Federal Reserve Bank, "Press Briefing: Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands," February 12, 2018, https://www.newyorkfed.org/press/pressbriefings/puerto-rico-and-the-us-virgin-islands. |

| 94. |

Samantha Artiga, Cornelia Hall, Robin Rudowitz, and Barbara Lyons, Health Care in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands: A Six-Month Check-Up After the Storms, Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation report, April 24, 2018, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/health-care-in-puerto-rico-and-the-u-s-virgin-islands-a-six-month-check-up-after-the-storms-report/. |

| 95. |

For example, the U.S. Census Bureau relies on decennial census data to track population and other demographic data for the USVI and other smaller island areas, while the American Community Survey (ACS) and Puerto Rican Community Survey track demographic trends on an ongoing basis. See Justyna Goworowska and Steven Wilson, Recent Population Trends for the U.S. Island Areas: 2000 to 2010, U.S. Census Bureau, Report P23-213, April 08, 2015, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p23-213.pdf. Also see U.S. Census, "About the Puerto Rico Community Survey," web page, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/about/puerto-rico-community-survey.html. USVI and Puerto Rico have not participated in the Census of Governments since 1982. |

| 96. |

Virgin Islands Consortium, "V.I. Budget Crisis, Part 19: Congress Can Still Do a Lot—But If It Doesn't, Brace For Impact," December 31, 2017, https://stthomassource.com/content/2017/12/31/v-i-budget-crisis-part-19-congress-can-still-do-a-lot-but-if-it-doesnt-brace-for-impact/. |

| 97. |

U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), Monthly Energy Review, figure 7.2, May 2018, https://www.eia.gov/totalenergy/data/monthly/pdf/sec7.pdf. According to EIA estimates for 2017, natural gas fueled 31.7% of U.S. electricity generation, while coal fueled 30.1%. See EIA, "FAQ: What is U.S. Electricity Generation by Energy Source," https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=427&t=3. |