This report provides an overview of economic and fiscal conditions in the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI). The political status of the U.S. Virgin Islands and responses to Hurricanes Irma and Maria are not covered in depth here. Fiscal and economic challenges facing the USVI government may several issues for Congress. First, Congress may choose to maintain oversight of federal policies that could affect the USVI's long-term fiscal stability. Second, Congress may consider further legislation that would extend or restructure long-range disaster assistance programs to mitigate those challenges and promote greater resiliency of infrastructure and public programs. Federal responses to the USVI's fiscal distress could conceivably affect municipal debt markets more broadly.

Geography

The U.S. Virgin Islands are located about 45 miles east of Puerto Rico and about 1,000 miles southeast of Miami, Florida. The three larger islands—St. Croix, St. Thomas, and St. John—are home to nearly all of the roughly 105,000 people living in the U.S. Virgin Islands. The USVI capital, Charlotte Amalie, is located on St. Thomas, which is the primary center for tourism, government, finance, trade, and commerce. The Virgin Islands National Park covers about two-thirds of the island of St. John, which is located to the east of St. Thomas. St. Croix—situated approximately 40 miles south of St. Thomas and St. John—is the agricultural and manufacturing center of the USVI. The U.S. Virgin Islands also includes a fourth smaller island—Water Island—as well as many other smaller islands and cays. The British Virgin Islands (BVI) are, by and large, east and slightly north of the U.S. Virgin Islands. The southern shore of Tortola, the largest island in BVI, is less than two miles north of the northern shore of St. John, USVI.

Historical Background

Danish Colonial Era

In 1672, the Royal Danish West Indian Company (Det Kongelige Octroyerede Danske Vestindiske Compagnie) took control of St. Thomas and set up plantations. The Company expanded to St. John (then St. Jan) in 1718 and then purchased St. Croix from France in 1733.1 Sugar production and export was the primary economic sector during the period of Danish colonial control, although cotton, tobacco, indigo and other products were also exported. In 1754, the king of Denmark established a free trading policy, which encouraged commercial activity on St. Thomas, sidestepping restrictions imposed by the main European powers of the time.2 Economic conditions on those islands, however, slowed in the 1830s and a slave revolt in 1848 led to the abolition of slavery.3

After 1848, the economy of the Virgin Islands slowed for a combination of reasons. Other Caribbean ports attracted more trade, steam-powered ships could make more direct connections between North American and Europe, and the expansion of beet sugar production in Europe, Russia, and North America led to lower prices for the cane sugar industry.4

U.S. Acquisition and Administration

In 1867, Secretary of State William Seward reached an agreement with Denmark to buy the islands. The Senate, however, declined to ratify the treaty.5 After other unsuccessful attempts in the first decade of the 20th century, the U.S. government purchased the islands from Denmark in 1917, after a set of negotiations prompted by concerns that Germany might use the islands to attack American shipping.6 The U.S. government assumed control of the islands on March 31, 1917, just a week before the United States entered World War I. While the United States acquired the islands for strategic reasons, the islands have not generally served a strategic purpose beyond keeping them out of the control of potentially hostile powers.

Naval officers administered the islands after the United States took possession and made important improvements in public health, water supply, education, and social services. Efforts to advance economic development were less successful.7 In 1931, governance responsibilities were transferred to the U.S. Department of the Interior.8 In the 1930s, civilian administrators sought—largely unsuccessfully—to revive sugar production and convert failing plantations into smallholder homesteads. The diversion of labor to military projects during World War II led to further declines in agricultural production. After the end of Prohibition in 1933, however, rum distilling became a growing source of manufacturing employment, and taxes on rum have been an important revenue source.

Post-World War II Economic Development

Other types of manufacturing once employed significant numbers, but have declined in recent years. Several watch assembly plants started up in 1959, but the last one closed in 2015.9 A large bauxite processing plant was built on St. Croix in the early 1960s, but closed in 2000 after several ownership changes.10 Near that site, Hess Oil partnered with a Venezuelan oil company to build a major oil refinery. That refinery, known as HOVENSA, for a time was one of the largest in the world, but closed in 2012.11

Early efforts in the 1950s to promote tourism were another success, especially after the closing of Cuba to American tourism after the 1959 Cuban Revolution. Tourism remains the major employer and economic activity in the U.S. Virgin Islands. The Revised Organic Act of 1954 (P.L. 83-517) included a provision to rebate, or "cover over," federal excise taxes on goods produced in the Virgin Islands to the island's government.12 The cover over of federal taxes on rum has been an especially important revenue source.

Current Structure of the Economy

Income Trends and Distribution

Median household income in the USVI for 2009, the latest available income estimate from the U.S. Census Bureau, was $37,254, about 75% of the mainland estimate of $50,221. Demographic and economic data for U.S. territories are typically less extensive and reported less frequently than for states.13 Table 1 compares the distribution of household incomes in the USVI with the U.S. total.

The distribution of household income levels in the USVI is skewed towards lower income brackets compared to U.S. totals. For example, 13.5% of USVI households had incomes below $10,000 in 2009, as compared to 7.8% for the U.S. total.

Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita provides another measure of economy activity. GDP is defined as the value of goods and services produced in a given area during a year. While income produced in an area that is repatriated elsewhere is included in GDP, it is excluded from gross national product (GNP), which reflects incomes of area residents. For areas where flows of repatriated earnings are large, GDP may be a flawed measure of local incomes.

Data on such flows of repatriated earnings, which may result from tax avoidance or minimization strategies, are difficult to obtain. The European Union added the USVI to a list of "non-cooperative tax jurisdictions" in March 2018.14 The European Council, a body consisting of EU heads of government and senior EU officials, stated that jurisdictions added to the list "failed to make commitments at a high political level in response to all of the EU's concerns."15 The USVI government called that decision "unjustified."16

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: U.S. Census, DP03: Selected Economic Characteristics: 2009 for USVI and the United States.

Notes: U.S. total is for resident population within the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. The collection of data for the mainland and USVI differ in certain ways. In general, Census Bureau data for USVI were gathered using decennial census long forms, while much of the mainland data are gathered through the American Community Survey program.

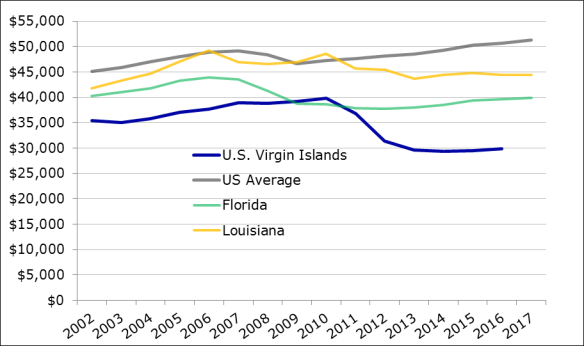

With those caveats regarding GDP in mind, Figure 1 presents trends in per capita GDP from 2004 through 2015. While per capita GDP fell during the 2007-2009 Great Recession, a sharper drop in USVI GDP per capita coincides with the demise of the HOVENSA refinery.

Tourism

In recent years, tourism and related trade has been the predominant component of the economy of the Virgin Islands. In years before Hurricanes Irma and Maria, about 1.2 million cruise passengers and about 400,000 airplane passengers arrived each year.17 Virgin Islands tourist destinations compete with many other Caribbean destinations. Much of the growth in Caribbean tourism has taken place in all-inclusive resorts that rely on low-wage labor, such as in the Dominican Republic.18

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). Chained price index used to adjust for inflation. Notes: Per capita GDP data may not reflect income of typical households due to skewness of income distribution and the repatriation of earnings. Florida and Louisiana have both been affected by major hurricanes. 2017 GDP data for the USVI are not yet available from BEA. |

Manufacturing

Manufacturing, which had played a major role in the Virgin Islands since the 1960s, now plays a minor economic role aside from two rum distilleries, which enjoy extensive public subsidies.19 Slightly more than 600 people were employed in manufacturing in 2015, mostly in small firms.20

Rum

The Cruzan distillery, which has a capacity to produce about 9 million proof gallons per year, claims a presence in the Virgin Islands since the mid-18th century. Cruzan was sold to Fortune Brands in 2008, after several changes in ownership.21 The Diageo distillery, which can produce some 20 million proof gallons per year, was built as part of a 2008 agreement with the territorial government.22 Diageo is a British multinational corporation specializing in the marketing of alcoholic beverages, which previously operated a distillery in Puerto Rico.23 A separate agreement between Cruzan and the USVI government was negotiated in 2009.24 In 2012, the USVI government agreed to modify the Cruzan agreement to increase subsidies, subject to set sales and marketing expense benchmarks.25

The agreements with the Virgin Islands Government and Diageo and Fortune Brands included an estimated $3.7 billion in subsidies and tax exemptions over 30 years, provided through proceeds of bonds that securitized "cover-over" excise taxes on rum sales rebated from the U.S. government and local tax abatements.26 The agreements also committed the USVI government to provide ongoing production and marketing subsidies paid from cover-over revenues. The agreement bars the USVI government from seeking reductions in rum subsidies.27 As noted above, federal excise taxes on rum imported into the United States from the USVI and Puerto Rico (PR), or from anywhere else, are "covered over" to the PR and the USVI governments.28

The HOVENSA Refinery and Limetree Bay

The HOVENSA oil refinery, mentioned above, had been one of the USVI's largest employers, with about 1,200 workers and nearly 1,000 contractors.29 Since 1998, the refinery operated as a joint venture between Hess Oil and Petróleos de Venezuela, a petroleum company owned by the Venezuelan government.30 The refinery suddenly shut down in 2012 after running large losses. While mainland refineries had shifted to natural gas as an energy source, the HOVENSA facility relied on relatively expensive fuel oil.31

HOVENSA filed for bankruptcy under chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code in September 2015.32 The USVI government received $220 million as part of the agreement to resolve HOVENSA's assets, which was used to cover the government's budget deficit for 2015.33 Limetree Bay purchased some HOVENSA facilities to build an oil storage facility that initially employed about 80 people and which later expanded to employ about 650 people.34

Over many decades, agriculture's role in the economy has dwindled to a marginal activity. Most of the island's food supply and essentially all of the molasses—a syrup extracted from sugar cane—used to produce rum is imported.

Energy and Water

The high cost of electricity in the U.S. Virgin Islands, at nearly 30 cents per kilowatt/hour or about three times the average cost on the mainland, may be one factor that hinders economic development.35 Island power systems do not benefit from gas pipelines or electric grids that extend over large areas, thus face higher costs than mainland systems. U.S. Virgin Islands Water and Power Authority (VIWAPA) supplies electrical power and water. The bulk of power generation is fueled by oil and diesel, although initiatives to enable use of propane and natural gas have been under way.36 For instance, VIWAPA modified some electric generating units to allow them the option to use natural gas, propane, or fuel oil.37 Expanding the efficient use of renewable sources of electricity, such as wind and solar, may require upgrades in transmission and generation systems. In 2015, renewable sources made up 8% of VIWAPA's peak demand generating capacity.38

Hurricanes Irma and Maria damaged an estimated 80% to 90% of VIWAPA's transmission and distribution lines, although power-generating plants were less affected. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) estimated that 93% of total USVI customers had their electric power restored by the end of January 2018.39

Public Finances

High Public Debt Levels Raise Concerns

Fiscal challenges facing the USVI government have intensified in recent years. Several news reports in 2017 posed pointed questions about the sustainability of the islands' public debts, which total about $2 billion.40 Those debt levels, on a per capita or on a percentage of GDP basis, are extremely high compared to other subnational governments in the United States. In addition, the most recent actuarial analysis of public pensions found a net pension liability of about $4 billion.41 The Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that "more than a third of USVI's current bonded debt outstanding as of fiscal year 2015 was issued to fund government operating costs."42

Concerns about debt levels had led each of the three major credit ratings agencies to downgrade at least part of the islands' public debts43 and led others to suggest that USVI's public debts would have to be restructured.44 In August 2017, Governor Mapp said that communications with credit ratings agencies had been suspended, which prompted those agencies to drop USVI's credit ratings.45

The U.S. Virgin Islands and other U.S. territories are not covered by the provisions of the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA; P.L. 114-187).46 Nonetheless, some credit ratings agencies saw enactment of PROMESA as a sign that Congress and the President could enact future legislation to enable debt adjustments in other territories.47

USVI Fiscal Responses

Like many state governments, USVI public revenues were severely affected by the 2007-2009 Great Recession. Tourism, the mainstay of the USVI economy, was affected. In turn, government revenues, typically closely tied to economic activity, also fell. In addition, rum subsidy payments doubled from 2006 to 2007 and 2008.48 As noted above, the closure of the HOVENSA refinery in 2012 resulted in hundreds of lost jobs and a significant contraction of the USVI tax base.

In recent years, the islands' government has run structural deficits and has used bond proceeds to cover shortfalls.49 Governor Kenneth Mapp, inaugurated in January 2015, has proposed various fiscal measures intended to reduce or eliminate those deficits. In August 2016, the islands' government took steps to issue bonds, which were to be used to cover financing shortfalls for its FY2017 budget. That issue was postponed until January 2017 and then cancelled.50 The loss of access to capital markets at reasonable rates left the islands' government with a narrow set of liquidity resources.51

In January 2017, Governor Mapp proposed a series of measures intended to strengthen public finances, including certain tax increases, enhanced revenue collection measures, and reductions in public spending.52 A package of tax measures, including higher taxes on beer, liquor, sodas, and timeshare rentals, which were part of the governor's proposals, was enacted on March 22, 2017.53 GAO, in an analysis of debts of U.S. territories, expressed doubts that those fiscal measures would restore access to capital markets or address shortfalls in the funding of public pensions and other retirement benefits.54

The governor also had announced that a $40 million revenue anticipation note would soon be issued through Banco Popular, which he contended would provide the USVI government with liquidity through September 2017.55 It appears that issuance was also suspended.56 The form of USVI's public debt service, in which many funds are routed through escrow accounts before reaching government coffers, also limits options for USVI policymakers.

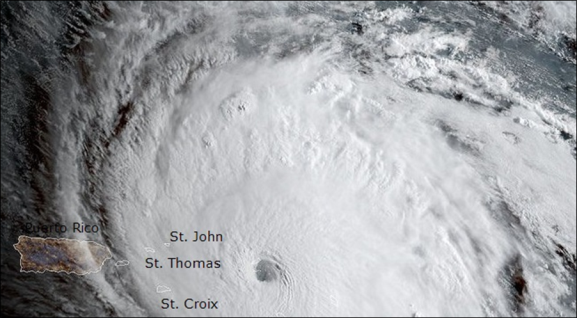

Aftermath of Hurricanes Irma and Maria

The USVI was hit by two massive hurricanes in September 2017, which caused extensive damage, from which island residents are continuing to recover. Hurricane Irma—shown in Figure 2—passed directly over St. Thomas and St. John on September 6, 2017, causing "widespread catastrophic damage."57 Two weeks later, on September 20, Hurricane Maria hit St. Croix, before continuing on to devastate Puerto Rico.58 In November 2017, the USVI government estimated that uninsured damage from the hurricanes will exceed $7.5 billion.59

|

|

Source: Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere, using NOAA GOES-16 satellite imagery. Notes: Hurricane Irma made landfall in the British Virgin Islands northwest of St. John and St. Thomas. The storm's center passed about 50 nautical miles north of San Juan, Puerto Rico. National Hurricane Center, Hurricane Irma: 30 August—12 September 2017, AL112017, May 30, 2018, p. 3. |

Disaster Responses

Disaster declarations following Hurricane Irma60 and Hurricane Maria61 enabled the USVI government and its residents to receive federal assistance through various provisions of the Stafford Act (P.L. 93-288, as amended).62 For example, the USVI government and two hospital authorities received Community Disaster Loans (CDLs) on January 3, 2018. The USVI government CDL totaled $10 million with a term of 20 years.63 CDLs were designed to provide liquidity to local governments that have suffered revenue declines due to disasters.64

Estimates based on USVI fiscal data suggest that public revenues were halved after the two hurricanes.65 Other forms of federal disaster assistance have included loans and grants to individuals and small businesses, as well as direct operations of the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA), the U.S. Corps of Engineers, and the U.S. Coast Guard, among other federal agencies.

Funding for disaster relief has been augmented by several supplemental appropriations.66 The extent of federal disaster assistance received by the USVI will depend, in part, on how funds provided in response to needs resulting from hurricanes and fires in 2017 are allocated among affected areas.

In the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123; §20301), enacted on February 9, 2018, Congress provided the USVI and Puerto Rico with additional Medicaid funding for the period January 1, 2018, through September 30, 2019. For the USVI Medicaid program, an additional $107 million was provided. Another $35.6 million would be available to the USVI subject to certain Medicaid program integrity and statistical reporting requirements. The federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) was also raised from 55% to 100% for both the USVI and Puerto Rico Medicaid programs during that time period.67

FY2019 Budget Proposals

In his FY2019 budget proposals, Governor Mapp set forth plans to extend the solvency of the USVI public pension systems.68 According to those proposals, the projected insolvency of those plans would be postponed from 2024 to 2025.69 Additional measures, to be outlined in the future, were claimed to suffice to postpone insolvency for three additional years. The FY2019 budget proposals also called for a lifting of a hiring freeze. Additional revenues were expected from expanded federal reimbursement for health programs, along with recovery-related investment activity, although decreased tourist traffic is expected to keep accommodation tax and related collections well below pre-hurricane levels in FY2019.

Economic Prospects

The USVI economy has relied heavily on tourism and related business activity, which made it more vulnerable to the effects of hurricanes than jurisdictions with more diverse economies. The severity of damage from Irma and Maria, and the subsequent disruption of the USVI tourism industry, suggest that a full economic recovery could take years. While cruise ship arrivals have rebounded somewhat, albeit at a pace 27% behind 2017 trends, air arrivals in 2018 have been about 50% or more below 2017 levels.70 Many hotels have remained closed since the hurricanes and some only plan to reopen in 2019.71

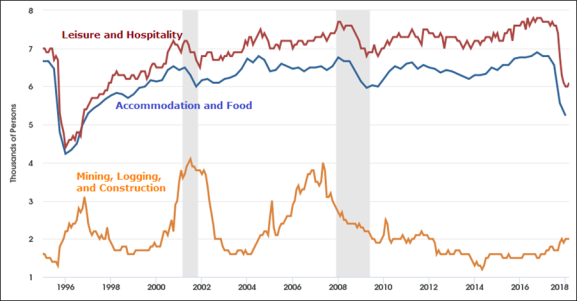

Figure 3 shows employment trends in two sectors associated with tourism—accommodation and food services as well as leisure and hospitality—along with the construction sector.72 Employment in the two tourism-related sectors shows a steep decline after Hurricane Marilyn in 199573 and after Hurricanes Irma and Maria in September 2017. Employment in those sectors took about six years to recover to pre-Marilyn levels. Increases in the construction sector offset about half of those losses in 1996 and 1997, presumably due to recovery and reconstruction work.

|

|

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Virgin Islands All Employees: Accommodation and Food Services; Leisure and Hospitality; and Mining, Logging, and Construction. Notes: Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Shaded areas denote 2001 and 2007-2009 U.S. recessions. |

The uptick in construction employment in late 2017 and early 2018, however, appears much smaller than in the post-Marilyn time period. Moreover, the post-hurricane increases in construction-related activity have been more gradual than the post-hurricane decreases in tourism-related sector activity.

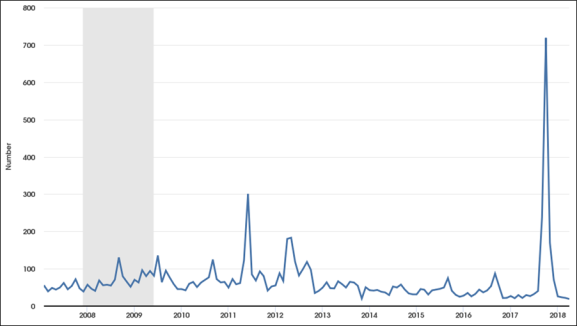

The economic effects of Hurricanes Irma and Maria can also be seen in initial unemployment claims data, shown in Figure 4. The post-Irma and Maria uptick in late 2017 is more than twice the size of the 2011-2012 upticks near the time of the closure of the HOVENSA refinery.

|

Figure 4. USVI Initial Unemployment Claims, Monthly Data, April 2007 through April 2018 |

|

|

Source: U.S. Employment and Training Administration, Initial Claims in U.S. Virgin Islands [VIRICLAIMS]. Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/VIRICLAIMS. |

The New York Federal Reserve Bank compared the economic effects of Hurricanes Irma and Maria on the USVI and Puerto Rico, noting that the estimated percentage job loss following those hurricanes (-7.8%) was far greater than the percentage job losses in New York City (-3.3%) during the Great Recession.74

Researchers report that many young professionals and health care workers have left the USVI for positions on the mainland, which may complicate recovery efforts in the health care sector.75

Tracking the progress of USVI economic recovery is complicated as many federal statistical programs report fewer data series for U.S. territories than for states.76 The Virgin Islands Bureau of Economic Research (VIBER), however, does produce regular reports on economic, tourism, and population trends.

Considerations for Congress

The fiscal and economic challenges facing the USVI government raise several issues for Congress. First, Congress may consider further legislation that would extend or restructure long-range disaster assistance programs to mitigate those challenges and promote greater resiliency of infrastructure and public programs.

Second, if fiscal pressures on the USVI intensify, Congress might consider a framework similar to that established by the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA; P.L. 114-187). In the past, however, USVI policymakers have opposed making PROMESA provisions available to other territories because of concerns about borrowing costs.77 At present, the USVI lacks access to the federal Bankruptcy Code or other processes for debt restructuring involving judicial processes.

Third, Congress might consider proposals to support initiatives to lower energy costs for the USVI. Mainland electrical power generation, to large extent, has shifted to using more natural gas as a fuel.78 Construction of a liquefied natural gas (LNG) import facility and accompanying generation plants could lead to lower energy prices and an enhanced capacity to employ renewable energy sources. Other innovative energy technologies might also be used to that end. While VIWAPA has taken some steps to modernize its generating units, some major investments may be required. For example, construction of a LNG facility and further conversions of generating units could lower electricity rates, but would require financial commitments that would likely challenge the fiscal capacity of the USVI government and VIWAPA. Moreover, LNG supply contracts typically extend over decades due to the scale of required investments, arrangements which could be difficult to negotiate given the USVI's fiscal situation.

Fourth, Congress may revisit the structure of the rum cover-over program to assess whether its current structure is appropriately fitted to public purposes. The contractual bar to USVI advocacy of changes in the cover-over program could require Congress to initiate any such alterations.

Fifth, Congress may choose to promote economic and social development through a wide range of tax and social program rules, some of which treat USVI differently than states.