Potential Options for Electric Power Resiliency in the U.S. Virgin Islands

In September 2017, Hurricanes Irma and Maria, both Category 5 storms, caused catastrophic damage to the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI), which include the main islands of Saint Croix, Saint John, and Saint Thomas among other smaller islands and cays. Hurricane Irma hit the USVI on September 6, with the eye passing over St. Thomas and St. John. Fourteen days later, on September 20, the eye of Hurricane Maria swept near St. Croix with maximum winds of 175 mph. The USVI government estimates that total uninsured damage from the hurricanes will exceed $7.5 billion. Although the electric power plants fared “relatively well” according to the local public water and power utility (the Virgin Islands Water and Power Authority [VIWAPA]), 80-90% of the power transmission and distribution systems across the USVI were damaged. In November 2017, the government of the USVI estimated that $850 million in hurricane recovery funding is needed to help “rebuild a more resilient electrical system.”

Before the 2017 hurricane season, VIWAPA was already challenged with fiscal problems and aging infrastructure. Although the USVI has never defaulted on its obligations, its fiscal problems include high debt levels, pension obligations, decreasing tax bases, and outdated infrastructures.

Like many remote island communities, the USVI is dependent on fuel oil for the generation of electricity. Until 2014, VIWAPA was 100% dependent on fuel oil. In 2010, the USVI established a goal to reduce fossil fuel-based energy use by 60% by 2025. As a result, VIWAPA has actively sought to improve energy efficiency and diversify its energy resources, particularly through the use of propane, solar, and wind power.

Initial disaster recovery efforts focused on restoring power. On September 13, 2017, the Federal Emergency Management Agency authorized the U.S. Department of Energy’s Western Area Power Administration (DOE-WAPA) to assist with emergency power restoration efforts on the USVI. DOE-WAPA completed their electric power system restoration activities and left the USVI by November 29.

Hurricanes and extreme weather will continue to threaten the Caribbean, which may prompt Congress to consider infrastructure hardening and improvements to make the systems more resilient. Building a modernized, flexible electric grid, capable of incorporating more renewable sources of electricity, underpinned by more efficient fossil fuel power plants and energy storage, may help the USVI accomplish these goals.

Policymakers are currently considering possible policy options for rebuilding the electricity grid with greater resiliency. This report explores several alternative electric power system structures for meeting the electricity services and needs of the USVI. The cost of rebuilding and modernizing the entire USVI electric grid likely far exceeds the fiscal capacity of the territory in the current budget environment. Incorporating resiliency could also be expensive. Congress may consider the role of comprehensive energy planning and whether the efforts to restore electric power in the USVI should include support for a resilient and modernized electric power system. Additional support for a modernized electrical grid may require new investment by the federal government, investment incentives to form public-private partnerships, or debt adjustments, among other strategies.

Potential Options for Electric Power Resiliency in the U.S. Virgin Islands

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- U.S. Virgin Islands Overview

- Population

- Economy

- Public Sector

- Virgin Islands Water and Power Authority

- VIWAPA's Power Plants

- VIWAPA's Transmission and Distribution System

- VIWAPA's Energy Efficiency Activities

- Restoration of the Electric Power System after Hurricanes Irma and Maria

- FEMA and Grid Restoration Assistance

- Collaboration with DOE and Western Area Power Administration

- Governor's Hurricane Recovery Funding Request

- Energy Planning Prior to 2017 Hurricane Season

- Past Power Evaluation Studies

- 2008 Power Evaluation Study

- EDIN-NREL Power Evaluation Study

- Comprehensive Energy Planning

- The 1982 Territorial Energy Assessment

- The 2006 Insular Areas Energy Assessment

- Making USVI's Electric Power System More Resilient

- Grid Hardening and Improving Resiliency

- Managing Costs of Hardening and Resiliency

- Reliability Through Island Transmission Interconnection

- Reducing Emissions and Renewable Generation

- Renewable Energy

- Potential Considerations for Congress

- USVI Recovery for the Energy Sector: Mitigation and Resiliency

- Legislation in the 115th Congress

Summary

In September 2017, Hurricanes Irma and Maria, both Category 5 storms, caused catastrophic damage to the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI), which include the main islands of Saint Croix, Saint John, and Saint Thomas among other smaller islands and cays. Hurricane Irma hit the USVI on September 6, with the eye passing over St. Thomas and St. John. Fourteen days later, on September 20, the eye of Hurricane Maria swept near St. Croix with maximum winds of 175 mph. The USVI government estimates that total uninsured damage from the hurricanes will exceed $7.5 billion. Although the electric power plants fared "relatively well" according to the local public water and power utility (the Virgin Islands Water and Power Authority [VIWAPA]), 80-90% of the power transmission and distribution systems across the USVI were damaged. In November 2017, the government of the USVI estimated that $850 million in hurricane recovery funding is needed to help "rebuild a more resilient electrical system."

Before the 2017 hurricane season, VIWAPA was already challenged with fiscal problems and aging infrastructure. Although the USVI has never defaulted on its obligations, its fiscal problems include high debt levels, pension obligations, decreasing tax bases, and outdated infrastructures.

Like many remote island communities, the USVI is dependent on fuel oil for the generation of electricity. Until 2014, VIWAPA was 100% dependent on fuel oil. In 2010, the USVI established a goal to reduce fossil fuel-based energy use by 60% by 2025. As a result, VIWAPA has actively sought to improve energy efficiency and diversify its energy resources, particularly through the use of propane, solar, and wind power.

Initial disaster recovery efforts focused on restoring power. On September 13, 2017, the Federal Emergency Management Agency authorized the U.S. Department of Energy's Western Area Power Administration (DOE-WAPA) to assist with emergency power restoration efforts on the USVI. DOE-WAPA completed their electric power system restoration activities and left the USVI by November 29.

Hurricanes and extreme weather will continue to threaten the Caribbean, which may prompt Congress to consider infrastructure hardening and improvements to make the systems more resilient. Building a modernized, flexible electric grid, capable of incorporating more renewable sources of electricity, underpinned by more efficient fossil fuel power plants and energy storage, may help the USVI accomplish these goals.

Policymakers are currently considering possible policy options for rebuilding the electricity grid with greater resiliency. This report explores several alternative electric power system structures for meeting the electricity services and needs of the USVI. The cost of rebuilding and modernizing the entire USVI electric grid likely far exceeds the fiscal capacity of the territory in the current budget environment. Incorporating resiliency could also be expensive. Congress may consider the role of comprehensive energy planning and whether the efforts to restore electric power in the USVI should include support for a resilient and modernized electric power system. Additional support for a modernized electrical grid may require new investment by the federal government, investment incentives to form public-private partnerships, or debt adjustments, among other strategies.

Introduction

In September 2017, Hurricanes Irma and Maria, both Category 5 storms, caused catastrophic damage to the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI).1 On September 6, the eye of Hurricane Irma passed over portions of the USVI—including St. Thomas and St. John—with maximum winds of 185 miles per hour (mph).2 On September 20, the eye of Hurricane Maria swept near St. Croix with maximum winds of 175 mph.3 The USVI government estimates that uninsured damage from the hurricanes will exceed $7.5 billion.4

According to the Virgin Islands Water and Power Authority (VIWAPA),5 the public water and power utility on the USVI, the Estate Richmond (St. Croix) and Krum Bay (St. Thomas) power plants fared "relatively well during the passage of Hurricane Maria" and provided uninterrupted electrical service to hospitals.6 However, according to the USVI recovery funding requests, the government estimates that 80-90% of the power transmission and distribution systems across the USVI were damaged. Recovery efforts from the hurricanes initially focused on maintaining electricity to hospitals and restoring electricity to water treatment plants and some industries. Governor Kenneth Mapp announced on January 10, 2018, that the goal to restore power to 90% of "eligible customers" had been met.7 According to the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), as of January 31, power has been restored to 93% of total customers (99% of eligible customers) across the USVI.8

Before the 2017 hurricane season, VIWAPA was already challenged with fiscal problems and aging infrastructure. Although the USVI has never defaulted on its obligations, it shares similar fiscal challenges as other islands in the Caribbean.9 These include high debt levels, pension obligations, decreasing tax bases, and outdated infrastructures.10

Policymakers are currently considering possible options for rebuilding the electricity grid on the islands, given the financial debt before the damage from the storms. VIWAPA's financial obligations, according to 2016 financial statements, include $232 million in outstanding debt along with an adjusted net pension liability of $259 million.11 The USVI government's much larger public debt, described in more detail below, may also affect rebuilding and investments in infrastructure.

Should Congress consider funding for electric power restoration, management of the electric power system by VIWAPA or alternatives to VIWAPA may be considered. This report presents a history of VIWAPA, describes issues related to the debt in USVI, and offers some options if Congress considers restructuring the electricity system. Improving the resiliency of USVI's grid will be expensive. Congress may consider whether investment incentives to form public-private partnerships could provide alternatives for modernizing the USVI's grid. Congress may also consider the role of comprehensive energy planning and whether the efforts to restore electric power in USVI will need to progress beyond simple restoration of electricity, and require new investment and oversight by the federal government.

U.S. Virgin Islands Overview

Population

The U.S. Virgin Islands are located about 45 miles east of Puerto Rico and about 1,000 miles southeast of Miami, FL. The USVI has a total land area of 134 square miles—nearly twice the area of Washington, DC—and is comprised of three primary districts, the islands of St. Croix, St. John, and St. Thomas.12 St. Thomas is the primary center for tourism, government, finance, trade, and commerce, and is home to the capital, Charlotte Amalie. The island of St. John lies to the east of St. Thomas. The Virgin Islands National Park covers nearly two-thirds of the island of St. John. St. Croix—situated approximately 40 miles south of St. Thomas and St. John—is the agricultural and manufacturing center of the USVI. In addition to the three large islands, there are approximately 50 smaller islands and cays within the USVI. The British Virgin Islands (BVI) are generally located to the east of the USVI. The USVI population was estimated at 103,700 persons in 2015, and about half of the population resides in Charlotte Amalie.13

Economy

The USVI economy in the past decade has struggled to cope with the closure of a major petroleum refinery in 2012 as well as a long-term decline of manufacturing employment. While the unemployment rate in 2008 (5.8%) equaled the U.S. average, USVI unemployment rose to 13.4% in 2013 and then declined to 10.3% in April 2017, remaining well above the mainland rate.14 Median household income in the USVI, according to 2009 Census Bureau estimates, was $37,254, well above that of Puerto Rico ($18,314) but below the U.S. level ($50,221).15 A similar pattern emerges from 2015 estimates of per capita income. Estimated USVI income per capita was $22,653, which was above that of Puerto Rico ($11,394) but below that of the United States as a whole ($28,930).16 The purchasing power of USVI incomes is diminished by the relatively higher costs of living, including the cost of energy, which is especially high relative to the mainland and other areas.17

In recent years, the USVI economy has depended heavily on tourism and related trade. In 2015, the USVI hosted 2.6 million visitors, 80% of which arrived on cruise ships.18 Hotels and other tourist facilities in the Caribbean are typically the largest commercial consumers of electric power.19 The islands' manufacturing sector, which had played a major role in economic development in the 1960s, is now a minor part of the USVI economy, aside from two rum distilleries, which are heavily subsidized with public funds.20 Slightly more than 600 people were employed in manufacturing in 2015, mostly in small firms.21

The February 2012 closure of the HOVENSA refinery compounded economic challenges presented by the 2007-2009 Great Recession.22 Located on St. Croix, HOVENSA was one of the world's largest petroleum refineries, employing about 1,200 people and nearly 1,000 contractors.23 The refinery operated as a joint venture between Hess Oil, a U.S. company, and Petróleos de Venezuela, a petroleum company owned by the Venezuelan government since 1998.24 HOVENSA filed for bankruptcy under chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code in September 2015.25 Some facilities were purchased by Limetree Bay, which maintains an oil storage facility in the USVI. That facility initially employed approximately 80 people, but now employs about 650.26 The government of the U.S. Virgin Islands received $220 million as part of the agreement to resolve HOVENSA's assets, which was used to cover the government's budget deficit for 2015.27 Despite the conversion of facilities to oil storage after ceasing refining and petroleum product exports, the refinery closure is estimated to have caused an annual decline of approximately $140 million in tax revenues.28

Since 2015, economic growth had recovered somewhat after several years of declines in the USVI gross territorial product (GTP).29 Economic data, however, have been scarce after the hurricanes of September 2017.

Public Sector

The public sector of the U.S. Virgin Islands faced serious fiscal challenges even before Hurricanes Irma and Maria. The USVI ran a $110 million deficit in FY2017, with ongoing annual structural deficits of about $170 million. The USVI government's long-term debt, according to FY2016 financial statements, totaled $2 billion, not including $3.4 billion in unfunded pension liability and VIWAPA debt.30

Several news reports in the last year have posed pointed questions about the sustainability of the islands' public debts.31 On a per capita or on a percentage of GTP basis, those debt levels are extremely high compared to other subnational governments. Concerns about debt levels had led each of the three major credit ratings agencies to downgrade the islands' public debts in January 2017.32 Those concerns intensified in the wake of the September 2017 hurricanes, as rating agencies complained of incomplete financial information from the USVI government. Within a month, two agencies withdrew their ratings and Moody's initiated a review of USVI bonds.33 At the end of January 2018, Moody's asserted that the USVI government would likely need to restructure its debts.34 Most of USVI's debt is structured as revenue bonds, which may restrict the islands' government's fiscal options.

In recent years, the islands' government has run structural deficits and has used bond proceeds to cover shortfalls.35 Most recently, the islands' government took steps to issue bonds in August 2016, which were to be used to cover financing shortfalls for its FY2017 budget. That issue was postponed until January 2017 and then cancelled.36 The apparent lack of access to capital markets at reasonable rates has left the islands' government with a narrow set of liquidity resources. The USVI Senate President, according to media reports, stated that the USVI "government [is] experiencing a financial crisis of great proportions."37

Governor Mapp, inaugurated in January 2015, proposed a series of measures intended to strengthen public finances, including certain tax increases and measures to constrain public spending.38 A package of tax measures, including higher taxes on beer, liquor, sodas, and timeshare rentals, which were part of the governor's proposals, was enacted on March 22, 2017.39 The governor also announced that a $40 million revenue anticipation note would be issued through Banco Popular, which he contended would provide the USVI government with liquidity through September 2017.40

Despite the devastation left in the wake of Hurricanes Irma and Maria, the Mapp Administration has sought to reassure bondholders that the USVI government would honor its financial commitments.41 The USVI government, nonetheless, faces serious fiscal challenges, even as the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has provided at least $456 million in disaster assistance.42

The USVI and other U.S. territories (aside from Puerto Rico) are not covered by the provisions of the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA; P.L. 114-187).43 Nonetheless, some credit ratings agencies view enactment of PROMESA as an indicator that Congress and the President could enact future legislation to enable debt adjustments in other territories.44

Virgin Islands Water and Power Authority

The Virgin Islands Water and Power Authority (VIWAPA) is an independent governmental agency of the USVI. It was created in 1964 by the Virgin Islands legislature. VIWAPA provides water and electricity services to customers across the USVI. It is a monopoly provider of electric power services and serves approximately 55,000 customers throughout the territory.45 It is not considered a monopoly provider of water services, providing desalinated potable water to approximately 13,000 customers in the major commercial and residential centers of St. Thomas, St. Croix, and St. John.46 Rates for both the electric and water systems are regulated by the Public Services Commission (PSC) of the USVI; the systems are independently financed with separate liens on net revenues securing the outstanding debt of each system.

Like many remote island communities, the USVI is dependent on fuel oil for the generation of electricity. In the Caribbean region, approximately 71% of the installed generation capacity utilized fuel oil in 2010.47 Overall, nearly 95% of electricity generation in the region relies on fossil fuel sources with fuel oil the predominant source.48 By contrast, in 2015 fuel oil accounted for less than 1%—and fossil fuel accounted for less than 65%—of the electricity generated in the United States.49 Historically, VIWAPA was able to purchase fuel from the HOVENSA refinery at below market prices due to the contractual agreement between the USVI and HOVENSA; however, VIWAPA was still subject to the price volatility of the market. Higher oil prices have led to higher electricity prices, and the closure of HOVENSA has increased VIWAPA's exposure to volatility.

The price of electricity in the USVI exceeds 32 cents per kilowatt-hour (kWh), which is about three times the average price on the mainland.50 VIWAPA's reliance on fuel oil for the bulk of power generation leaves customer rates vulnerable to fuel price increases—fuel surcharges have resulted in electricity rates up to five times higher than the average price on the mainland.51 This vulnerability to fuel price increases is accounted for in monthly utility bills, which include a levelized energy adjustment clause (LEAC) factor (or fuel factor). The LEAC factor is a customer surcharge that allows VIWAPA to address increases or decreases in fuel prices. VIWAPA's customer rates and adjustments to the LEAC factor are subject to approval by the Virgin Islands Public Service Commission.

VIWAPA has experienced cash flow challenges.52 The government of the U.S. Virgin Islands—VIWAPA's largest customer—has been slow in providing payment for services. Chronic slow payment in addition to incidents of nonpayment for electricity services has hindered the utility's ability to recover costs and maintain equipment. Furthermore, cash flow concerns are exacerbated because revenues from recovered rates do not adequately cover expenses, resulting in delays in major equipment maintenance and repair, decreases in inventory levels of spare parts, and deferrals in preventative maintenance. These actions have increased the frequency of equipment outages and failures, which not only decreases power generation efficiency but also increases the cost of supplying energy to the customers.53

VIWAPA's Power Plants

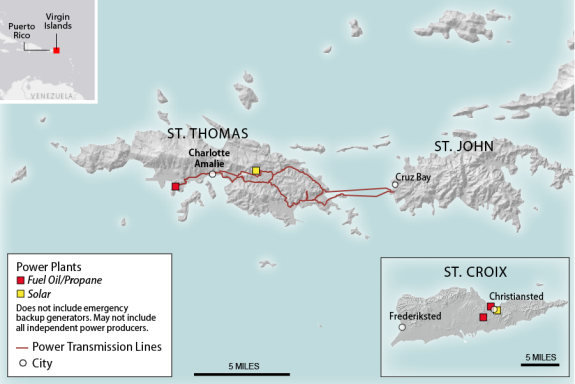

VIWAPA operates two separate electric power systems. Major generation facilities are located on the islands of St. Thomas and St. Croix (see Figure 1). St. John receives power from the generating station on St. Thomas via undersea cables and has backup power available via an emergency generator. On St. Thomas, VIWAPA's generating facilities are located at the Randolph E. Harley Generating Station in Krum Bay, on the southwestern end of the island. In addition to electricity generation, the site includes water production facilities and fuel oil unloading, storage, transportation, and warehouse facilities. On St. Croix, VIWAPA's electric generating facilities are located at the Estate Richmond site near Christiansted. Estate Richmond also has water production facilities and fuel oil unloading, storage, and warehouse facilities. VIWAPA relies heavily on distillate fuel oil (#2) and heavy fuel oil (#6) for power and water production, and fuel oil was the only fuel type used by VIWAPA for electricity generation until 2016.54

Table 1 lists VIWAPA's major generating units and their fuel source as of 2012 for St. Croix and St. Thomas. VIWAPA has actively sought to improve energy efficiency and diversify its energy resources in an effort to reduce fossil fuel-based energy use by 60% by 2025.55 In 2014, VIWAPA introduced solar power through power purchase agreements with independent power producers. According to EIA, the two largest solar facilities—each producing more than 4 MW of capacity—are located in Estate Donoe on St. Thomas and Estate Spanish Town on St. Croix.56 As of 2015, 8% of VIWAPA's peak demand generating capacity came from renewable sources. In addition to solar, wind power development has also been pursued, although the largest reported turbine is a 100-kilowatt unit on St. Croix.57

|

Unit No. |

Technology |

Fuel Type |

Rated Capacity (MW) |

In Service Date |

|

St. Croix Electric System (Total Rated Capacity 116.9 MW) |

||||

|

10 |

Steam Turbine/Oil-Fired Boiler |

No. 6 Oil |

10 |

1967 |

|

11 |

Steam Turbine/Oil-Fired Boiler |

No. 6 Oil |

19.1 |

1970 |

|

16 |

Combined Cycle Combustion Turbine |

No. 2 Oil |

20.9 |

1981 |

|

17 |

Combined Cycle Combustion Turbine |

No. 2 Oil |

21.9 |

1988 |

|

19 |

Simple Cycle Combustion Turbine |

No. 2 Oil |

22.5 |

1994 |

|

20 |

Combined Cycle Combustion Turbine |

No. 2 Oil |

22.5 |

1994 |

|

21 |

Heat Recovery Steam Generator |

— |

— |

1990 |

|

24 |

Heat Recovery Steam Generator |

— |

— |

2010 |

|

St. Thomas Electric System (Total Rated Capacity (212.8 MW) |

||||

|

7 |

Reciprocating Enginea |

No. 2 Oil |

2.5 |

1985 |

|

11 |

Steam Turbine/Oil-Fired Boiler |

No. 6 Oil |

18.5 |

1968 |

|

13 |

Steam Turbine/Oil-Fired Boiler |

No. 6 Oil |

36.9 |

1973 |

|

14 |

Simple Cycle Combustion Turbine |

No. 2 Oil |

12.5 |

1972 |

|

15 |

Combined Cycle Combustion Turbine |

No. 2 Oil |

20.9 |

1981 |

|

18 |

Combined Cycle Combustion Turbine |

No. 2 Oil |

23.5 |

1993 |

|

21 |

Heat Recovery Steam Generator |

— |

— |

1997 |

|

22 |

Simple Cycle Combustion Turbine |

No. 2 Oil |

24 |

2001 |

|

23 |

Simple Cycle Combustion Turbine |

No. 2 Oil |

39.5 |

2004 |

|

25 |

Simple Cycle Combustion Turbine |

No. 2 Oil |

22 |

2012 |

|

Total |

329.7 |

|||

Source: Governing Board of VIWAPA, Energy Production Action Plan, 2012, pp. 1-2.

Notes: Listed generating assets are those reported as of 2012. List does not include generators that supply power through power purchase agreements (e.g., solar power or wind power facilities).

a. This is included as part of the St. Thomas electric system although it is located on St. John and serves as an emergency backup generator.

In addition to introducing renewable power, VIWAPA has sought to diversify its fuel sources by converting or adding generating units that can consume propane. VIWAPA completed conversion of the main units on St. Croix in 2016, but outright replacement of some units in St. Thomas appears to be still ongoing.58 In addition to the equipment delay on St. Thomas, VIWAPA's propane supplier, Vitol, has withheld supplies due to VIWAPA's outstanding balance.59 As a result, VIWAPA extended its oil contract with Glencore and continues to use fuel oil as the primary fuel source as hurricane restoration proceeds.60 VIWAPA has targeted a 40% reduction in fossil fuel use through increasing power generation efficiency and reducing power consumption. While switching to propane is expected to reduce emissions and fuel costs, propane contains less energy than diesel fuel and produces less power output per unit of fuel.

VIWAPA's Transmission and Distribution System

VIWAPA operates two separate transmission and distribution (T&D) systems: one for St. Croix and one for St. Thomas and St. John. The T&D system on St. Croix is comprised of 24.9 kV subtransmission lines and 13.8 kV distribution lines. The T&D system on St. Thomas and St. John is comprised of 34.5 kV primary lines and 13.8 kV distribution lines. Both systems have some underground lines. Collectively, the USVI T&D systems have 737.8 miles of lines: 30.1 miles of 34.5 kV of which 59% (17.7 miles) is underground including two submarine cables to St. John; 106.6 miles of 24.9 kV of which 15% (16.5 miles) is underground; and 601.1 miles of 13.8 kV of which 7% (40.3 miles) is underground.61

VIWAPA's Energy Efficiency Activities

As part of the commitment to reduce fossil fuel use by 60% by 2025, VIWAPA has implemented a customer education and energy conservation campaign. Tips to save energy include the following:

- Using ceiling fans to cool rather than air conditioning units;

- Washing clothes in cold water;

- Hanging wet towels, swimming suits, and other items outside to dry in the sun rather than using an electric dryer;

- Air-drying dishes in the dishwasher rather than using the automatic dryer mode;

- Investing in a solar water heater;

- Replacing incandescent light bulbs with high efficiency, long-life compact florescent bulbs (CFL) or LED (light emitting diode) bulbs.62

In addition to encouraging energy conservation at home, VIWAPA is actively replacing sodium street-lamps with LEDs and incorporating solar power in street lighting.63

Restoration of the Electric Power System after Hurricanes Irma and Maria

The USVI were hit by both hurricanes, and damage on two of the three main islands (St. Thomas and St. John) was extensive. As noted, the USVI government estimates that 80-90% of the power transmission and distribution systems across the USVI were damaged. As of January 29, 2018, power had been restored to nearly 93% of total customers across the USVI.64 VIWAPA reported that approximately 3,900 customers (7%) remained without power within the territory. St. Thomas had approximately 2,900 total customers (11%) without power, which includes data from Water Island (100% power restored) and Hassel Island (0% power restored). St. John had approximately 160 total customers (4%) without power. St. Croix had approximately 800 total customers (3%) without power. As of January 31, 2018, nearly 800 "supplemental utility personnel" were assisting in restoration efforts across the territory.65 U.S. Coast Guard had reopened all ports that receive marine delivery of petroleum products.

On St. John, work to restore infrastructure and reopen the Virgin Islands National Park has started. St. Croix is accepting hotel guests and received its first posthurricanes cruise ship on November 11, 2017.66

FEMA and Grid Restoration Assistance

As a public utility, VIWAPA is an eligible applicant that can receive federal assistance through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). In particular, FEMA provides grant assistance through the Public Assistance Grant Program (PA Program) for the repair, restoration, and replacement of public facilities, as defined by law, in states and communities that have received major or emergency disaster declarations through the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (Stafford Act, P.L. 93-288, as amended).67

Generally, under the PA Program, an eligible applicant who owns a public facility or facilities may receive grant assistance to repair or replace its predisaster design (its size and capacity) and function. Grants additionally can include eligible expenses that are required by current applicable codes and standards, provided the work is required as a direct result of the disaster. Pursuant to 44 C.F.R. §206.226(d), for a code-required improvement to be eligible, the code or standard requiring the upgrade must meet the five criteria listed below:

- 1. Apply to the type of repair or restoration required;

- 2. Be appropriate to the predisaster use of the facility;

- 3. Be found reasonable, in writing, and formally adopted, and implemented prior to the disaster declaration date or be a legal federal requirement;

- 4. Apply uniformly to all facilities of the type being repaired within the applicant's jurisdiction; and

- 5. Have been enforced during the time that it was in effect. FEMA may require documentation showing prior application of the standard.

In 2009, the USVI enacted net metering safety standards that follow the interconnection standard in the federal Energy Policy Act of 2005 (EPAct 2005, P.L. 109-58) via regulation.68 EPAct 2005 referenced the IEEE standard 1547, Standard for Interconnecting Distributed Resources with Electric Power Systems, which is a consensus-based industry standard that "establishes criteria and requirements for interconnection of distributed resources (DR) with electric power systems."69 Whether FEMA will determine this code standard to be "applicable" per 44 C.F.R. §206.226(d) is unclear.

Qualifying projects may also be required to meet minimum standards for public assistance to promote resiliency and achieve risk reduction. The minimum standards for eligible building restoration projects are described in a 2016 FEMA policy.70 According to FEMA, the minimum standards policy does not directly apply to most power facilities, as power facilities do not fit the definition of "building."71 At issue is whether the legal authority supporting the FEMA minimum standards policy would allow for further expansion of the policy to power facilities at the discretion of FEMA.72

While the 2017 hurricane season severely impacted the USVI, hurricane damage is not unknown to the USVI and VIWAPA. As of 2010, VIWAPA had completed $29 million in hazard mitigation projects, $18 million of which have been financed through FEMA's Hazard Mitigation Grant Program.73 A brief chronology of hurricane damage to VIWAPA infrastructure is provided in Table 2.

|

September 17, 1989 |

Hurricane Hugo struck the USVI and damaged 60% of the electric distribution system in St. Croix. VIWAPA restored the system and received disaster funding from FEMA of approximately $55 million (accounting for overpayment). |

|

September 15, 1995 |

Hurricane Marilyn struck the USVI and damaged the electric distribution system. Estimated cost of repairs was $45 million, and VIWAPA funded restoration and rehabilitation through various means. |

|

September 2004 |

Tropical Storm Jeanne damaged VIWAPA facilities. Estimated repair costs were approximately $1 million. |

|

October 2008 |

Hurricane Omar struck the USVI and caused an estimated $3 million worth of damage to the electric distribution system. |

Collaboration with DOE and Western Area Power Administration

On September 13, FEMA authorized the U.S. Department of Energy's Western Area Power Administration (DOE-WAPA) to assist with emergency power restoration efforts on the USVI.74 This mission was authorized after Hurricane Irma through a mutual aid agreement.75 On November 30, 2017, the final crew members from DOE-WAPA had completed their electric power system restoration activities and left the USVI.76 Crews from DOE-WAPA had been in the USVI since mid-September as part of the USVI emergency power restoration mission.77

Governor's Hurricane Recovery Funding Request

In November 2017, the government of the USVI estimated that uninsured hurricane-related damages would exceed $7.5 billion.78 Total funding in the request for the islands is $7.49 billion to address government, public sector, and housing needs. Within that total, the request for the energy sector is $850 million. The intent is to incorporate resiliency measures into the electric power system rebuilding effort. This would include burying utility lines, building microgrid systems, and adding renewable generation capacity to the power system.

Energy Planning Prior to 2017 Hurricane Season

The USVI and VIWAPA engaged in several energy planning efforts prior to the 2017 hurricane season. Efforts focused on evaluating future power needs and cost-effective options as well as comprehensive energy planning. This planning process is consensus-based, involving various stakeholders, and includes assessing future energy needs within the context of existing policies.79

Past Power Evaluation Studies

Two power evaluation studies conducted for VIWAPA assessed future power needs and options for the USVI's electric power systems.

2008 Power Evaluation Study

The design engineering company R.W. Beck completed a study of VIWAPA's future electricity and water production options. The study was commissioned by the Public Services Commission and VIWAPA. The primary purpose of the study was to compare selected potential technologies and fuels and provide VIWAPA with information to evaluate responses for future requests for proposals to meet various goals. These goals include reducing operating costs of both electricity and water systems and decreasing dependence on fossil fuels. The study recommended four alternative approaches to electricity generation and water production that warrant further consideration based on technological and financial feasibility and potential environmental compliance.80 For the electric power system, recommended alternatives included electricity generation from wind power, liquefied natural gas (LNG), and circulating fluidized bed (CFB) boilers that use petroleum coke and coal as fuel sources.

EDIN-NREL Power Evaluation Study

In 2010, USVI set an aggressive goal to reduce USVI's dependence on fossil fuel by 60% by 2025. In collaboration with the International Energy Agency and other public-private partnerships, DOE cosponsored the "Energy Development in Island Nations" (EDIN)81 initiative with the USVI as an initial pilot project to demonstrate economic ways for islands to use renewable electricity technologies and energy efficiency to reduce energy costs. Recommendations from the EDIN project were at the core of the USVI's renewable energy initiative called VIenergize.82

VIWAPA, in collaboration with the DOE and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), the Department of the Interior (DOI), and the Virgin Islands Energy Office (VIEO), developed and implemented a plan to meet the goal of 60% fossil fuel reduction by 2025. The collaboration established a baseline energy use, assessed clean energy resources, and identified both renewable energy and energy efficiency solutions.83

As part of this relationship, NREL developed a roadmap for the development of clean energy resources in the USVI in addition to reports that consider specific technologies.84 The Governing Board of VIWAPA, through consultation with technical experts and management staff, identified the following strategies for the reduction of the cost of energy:

- 1. Implement measures to enhance production efficiency at existing power generation facilities.

- 2. Convert base load power production from fuel oil to liquefied natural gas or liquefied petroleum gas.85

- 3. Develop grid interconnection between the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico.

- 4. Maximize development of solar and wind resources.

- 5. Pursue biomass energy and ocean thermal energy as potential diversification of base load energy.

Comprehensive Energy Planning

Congress has recognized that electric power systems in insular areas—territories of the United States including the USVI—are vulnerable to hurricanes and typhoons and dependent on imported fuel.86 Under 48 U.S.C. §1492, Congress authorized comprehensive energy planning, demonstration of cost-effective renewable energy technologies, and financial assistance for projects in insular areas related to energy efficiency, renewable energy, and building power transmission and distribution lines.87

Two energy assessment reports were conducted in fulfillment of requirements under 48 U.S.C. §1492: a DOE report issued in 1982,88 and a DOI report issued in 2006.89 Both reports, reviewed below, acknowledge cooperation with territorial governments and utilities.

The DOE report states that no appropriations were received for the assessment; therefore, the scope was constrained to assessing the existing energy supply, existing demand data, and the potential for near-term commercially feasible technologies. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 (P.L. 109-58) directed the DOI to update the 1982 assessment, which led to the 2006 report.

The 1982 Territorial Energy Assessment

The 1982 DOE report stated that replacing imported petroleum products for electric power with indigenous energy resources could benefit the economy.90 Recommendations included reducing electricity and gasoline consumption. Alternative resources considered included solar for water heating, wind, and ocean thermal energy conversion. Despite large reserve margins, the electric power system "experiences reliability problems because of its isolation and because of maintenance difficulties."91

The 2006 Insular Areas Energy Assessment

In 2006, the DOI report assessed the energy system for insular areas including the USVI. Petroleum remained the primary source of energy. The report discussed that in addition to electricity generation, VIWAPA uses exhaust heat from diesel fuel combustion turbines for evaporative desalination plants. For new generating units, the report recommended that VIWAPA consider alternative technologies, concluding that diesel fuel is not the best alternative considering the capital cost, reliability, and air quality concerns associated with diesel generation.92 Recommendations included the following:

- Developing power purchase agreements with fuel oil suppliers, larger hotels, and resorts to increase efficiency and explore cogeneration opportunities;

- Installing replacements for inefficient generation;

- Evaluating feasibility of using petroleum coke; and

- Assessing building energy efficiency standards and other metrics to reduce energy demand.93

Making USVI's Electric Power System More Resilient

Electric system reliability94 is a key measure of a utility's performance, and is often mentioned by electric utilities simply as their ability to "keep the lights on." As such, it can be measured based on the frequency and duration of power outages during a period (usually as hours of power outage during a year).

The amount of power a utility generates must be kept in balance with the amount of power customers need (i.e., customer demand). Utilities seek to have enough power generation (in terms of megawatt-hours) from a system's installed capacity and a capacity reserve (both in megawatts) to serve the peak power demand from customers. Each of the USVI's two grids maintains enough capacity and reserve margin to separately meet customer demand on the St. Thomas and the St. Croix systems, as described earlier in this report. Maintaining reliability is therefore planned uniquely for each of the two grids, and thus conceivably made more difficult and expensive since the two electricity systems are not presently interconnected.

The resiliency95 of a power system is another matter. According to the DOE, there are no commonly used metrics for measuring grid resilience. While DOE says that several resilience metrics and measures have been proposed, it recognizes that to date "there has been no coordinated industry or government initiative to develop a consensus on, or implement, standardized resilience metrics."96

If power outages are to be minimized, electric power systems must be able to recover quickly from weather-related events which challenge the system's reliability. Electric utilities generally approach planning for weather-related events from the potential for an event to result in an outage. Extreme weather events, such as hurricanes, present another level of risk to the reliability of a system, especially for electric utility systems on isolated Caribbean and Atlantic islands that face such risks annually. As of 2010, VIWAPA had completed $29 million of hazard mitigation projects, $18 million of which has been financed through FEMA's Hazard Mitigation Grant Program.97 In the November 2017 hurricane recovery funding request, the USVI estimated that $300 million is needed to meet the mitigation and resiliency needs for the energy sector.98

Grid Hardening and Improving Resiliency

Electric power systems exposed to the elements in the USVI were severely damaged by the 2017 hurricanes. In November 2017 the CEO of VIWAPA testified as follows:

By far, the most extensive damage was experienced by the transmission and distribution system and the overall electrical grid. The two power plants, in Estate Richmond on St. Croix and at Krum Bay on St. Thomas, fared well. The transmission and distribution system suffered damage at the hands of Hurricane Irma on the order of 80% on St. Thomas and 90% on St. John, with the two outlying islands, Hassel Island and Water Island, each suffering about 90% damage to their electrical infrastructure. Hurricane Maria rendered about 60% damage to St. Croix's system. Today, [VI]WAPA is engaged in a major restoration effort on all islands. We are in the process of rebuilding transmission feeders and primary circuits, all before we can completely restore commercial and residential customers.99

While hardening activities are generally based on the types of extreme weather experienced in a region, activities to improve resiliency may consider more than a region's history with storms. According to a 2010 report from DOE, a number of actions exist for hardening electric grid transmission and distribution infrastructure. Some actions electric utilities can take to harden energy infrastructure include the following measures.100

To protect against damage from flooding:

- Elevating substations, control rooms, pump stations;

- Relocating or constructing new lines and facilities.

To protect against damage from high winds:

- Upgrading damaged poles and structures;

- Strengthening poles with guy wires;

- Burying power lines underground.

Newer electric power infrastructure can potentially survive damage from extreme weather better than older infrastructures, simply due to the repeated exposure over time to weather events of older facilities. Therefore, DOE also recommends modernizing electricity systems by deploying smart grid technologies with smart sensors and control technology to pinpoint system problems, and reroute power flows as needed.101

The chief executive officer of VIWAPA described the efforts the utility planned to undertake to further harden electric systems to minimize the effects of severe weather (such as major hurricanes).

[VI]WAPA is beginning to replace traditional wooden poles with composite poles on various key transmission feeders on all islands. The composite poles have a proven track record of withstanding sustained wind speeds of up to 200 miles per hour. We have identified a need for approximately 4,300 composite poles for major primary electrical circuits for the St. Thomas-St. John district, and approximately 5,900 composite poles on St. Croix. The Authority is also aiming to relocate key aerial facilities underground. Utilizing past FEMA hazard mitigation grant funding, [VI]WAPA has already placed limited portions of its distribution system underground. Service to critical infrastructure such as hospitals, airports, and 75% of the business districts are underground. In the aftermath of last month's storms, they were among the first facilities to be restored. Our focus now is to underground facilities that service key seaports and shipping companies, to be in a position to restore inbound cargo traffic to the islands upon the opening of the shipping channels by the Coast Guard following a hurricane or tropical storm.102

DOE also states that electric system resiliency can be enhanced by improvements to utility preparedness by programs and investments which improve general readiness (e.g., conducting hurricane preparedness planning and training; complying with inspection protocols; managing vegetation; participating in mutual assistance groups; improving employee communications; and tracking, purchasing, or leasing mobile transformers and substations and procuring spare equipment). Storm-specific readiness can also be improved by activities such as maintaining minimum fuel tank volumes, facilitating employee evacuation and reentry to storm areas, securing fuel contracts for emergency vehicles, expanding deployment staging areas, and supplying logistics to recovery staging areas.103

Other observers point out that distributed resources, particularly microgrids,104 can function separately from a centralized power grid, and may be easier to repair and restore electricity service than a centralized power generation system, which provides power to communities via transmission and distribution systems.105

[VI]WAPA is also exploring the benefits of electric micro grids, a move toward hardening of the electrical grid which is also vulnerable in windstorms. We have the first micro grid on the drawing board for implementation on St. Croix. Each micro grid would be a localized group of energy sources that would work both in lockstep with [VI]WAPA's generating facilities but independently as a source of power. In the event of a major electrical service interruption, for example, the micro grid would function as a small generating facility to produce electricity on its own power.106

Managing Costs of Hardening and Resiliency

Hurricanes and other severe storms are almost certain to recur in the Caribbean region as part of the weather cycle. The potential for resulting major damage varies based upon the intensity of such storms. A recent study107 recommended that exposed infrastructure be protected against wind speeds of 155 miles per hour and heavy flood waters, based on observations and damage to electric power transmission and distribution infrastructure from Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico.

Resiliency arguably entails a certain amount of redundant capabilities in the power generation, transmission, and distribution functions. Deciding just how much redundancy is considered necessary will likely go beyond the usual cost-benefit analyses to address perceived risk. While DOE's recommendations below are extensive, electric utilities generally try to manage the potential costs of actions to promote system reliability by considering the risks of various extreme weather events. A strategy for grid resilience was suggested in the 2013 report from DOE and the President's Council of Economic Advisors and focused on six factors identifying weather-related risks to the system, and the cost for hardening of the grid.108

Key among these factors were the following:

- Risk awareness and preparation using mutual aid networks with other utilities;

- Cost-effective grid strengthening focused on distribution line pole upgrades to concrete, steel, or composite materials, and transmission tower upgrades to galvanized steel lattice or concrete structures; and

- Increasing system flexibility and robustness by utilizing new technologies for power generation and control, and energy storage.

The government of the USVI says it has been focused on improving the resiliency of the island's grid gradually over time, and with each episode of severe weather.

We're already taking basic steps to improve the resilience of the grid as we build it back, using things like composite poles that can better withstand hurricane force winds, but we must go further. With your help, we plan to bury power lines on the primary and secondary road systems throughout the Virgin Islands and invest in a micro-grid system that will add renewable generation capacity—things like solar and wind energy—to the system.109

Improving the resilience of USVI's electricity system to extreme weather events is made even more critical, since the territory has separate grids serving the islands. VIWAPA is also looking at the potential benefit of adding a microgrid capable of serving as a small generating facility, independent of the grid, in the case of a major power outage.

[VI]WAPA is working to develop the initial micro grid in conjunction with the Virgin Islands Port Authority at St. Croix's Henry E. Rohlsen Airport. This particular micro grid would be energized with four megawatts of solar power and two megawatts of battery storage. Depending on available funding, [VI]WAPA will seek to develop additional micro grids at strategic locations across the Territory.110

Reliability Through Island Transmission Interconnection

VIWAPA has discussed the potential purchase of 20-30 MW of power via submarine transmission lines with the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA):

[S]uch an interconnection arrangement may provide benefits to the Authority such as reduced power supply costs, reduced operating reserves requirements, improved system reliability, potential economic long- or short-term arrangements, potential participation in non-oil fired generation to be developed in Puerto Rico, and the potential to take advantage of economies of scale in the development of larger generating units. Due to the potential benefits regarding this alternative, discussions with PREPA should be given priority by the Authority. If this arrangement is shown to be beneficial, the Authority plans to incorporate this option in future power supply evaluations.111

The proposed project would develop a 45-mile, 115 kV underwater transmission cable with fiber optics and connect between the eastern point of Fajardo, Puerto Rico, and Botany Bay on the island of St. Thomas:

As contemplated, the IAES [Inter American Energy Sources LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of PREPA] would own the transmission cable and would develop, permit, finance, and construct the Transmission Project in consultation with the Authority. The Authority would develop, permit, finance and construct a new substation at Botany Bay. The Authority would purchase from IAES electric power generated by PREPA subject to the terms and conditions of a power and other required purchase agreements. Subject to approvals by PREPA and the Authority, as well as receipt of various approvals and permits, the Transmission Project could be commercially available within a three-year period. The estimated direct construction cost of the new substation at Botany Bay has not yet been developed and is not included in the Authority's 2010-2014 Capital Improvement Program.112

In addition to a transmission project with Puerto Rico, VIWAPA has also considered a direct current (DC) transmission intertie between St. Thomas and St. Croix. A direct route passes through water that is approximately 12,000-18,000 feet deep; however, for practical purposes a water depth limited to no more than 6,000 feet deep is preferred. Accounting for the shallower depth, a potential route could be expected to be approximately 100 miles in length. The length makes a DC circuit operating 150 kV more practical than an alternating current (AC) due to transmission cable limitations. The benefits of such a system include the ability to use larger size generators and smaller planning reserves. In the USVI, the planning reserve margin is currently based on the two largest units on each island. An interconnection could reduce this planning margin to the two largest units on the two islands collectively. Larger generating units typically have lower capital costs per kilowatt (kW). Without an interconnection, each island's system must operate to withstand a sudden loss of the largest unit due to forced outage. St. Croix is, therefore, limited to generating units of approximately 20 MW each to maintain system reliability. With an interconnected system, larger units could be installed on either island without reduced systems reliability.113 The 2008 analysis found that at the time these benefits combined with plant efficiency improvements would not outweigh the costs of the interconnection project; however, the report noted that VIWAPA may consider an interconnection in the future when considering the addition of new or replacement generation capacity.

|

Caribbean-wide Power Generation and Marketing Another potential option to address energy costs and employment issues in the region could be for a power generation and marketing authority (PGMA), based in Puerto Rico or the USVI. A U.S.-based PGMA could potentially export power via undersea cables to a wider Caribbean region.114 A federal government corporation created for this purpose would likely need to price its output to recover its capital costs of construction over a reasonable period, and to cover its operations and maintenance costs. Like power marketing administrations (PMAs)—which were created to both dispose of electric power produced by dams and to promote small community and farm electrification—any federal funds used for the PGMA's establishment or costs could be repaid with interest to the U.S. Treasury. As with other federal government corporations, establishing a PGMA would require an act of Congress. A PGMA taking advantage of economies of scale and fueled by cleaner burning LNG could generate electricity at U.S. market-based rates, which are likely to be lower cost than power generated in most Caribbean Basin countries from smaller plants burning diesel and heavy fuel oil in single country markets. Basing a PGMA in the USVI would not require a Jones Act exemption, as one already exists,115 and could potentially repurpose some of the HOVENSA facilities. |

Reducing Emissions and Renewable Generation

Power generation in the USVI, like most of the Caribbean, has been fueled historically by imported petroleum products since the islands lack fossil fuel resources. With the aging of power plants in the St. Thomas and St. Croix systems and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency consent decrees to reduce emissions, the USVI began to look at alternative fuels. Propane was chosen for a new generation of central station power plants, as it was deemed the cheaper alternative to liquefied natural gas (LNG).116 However, the new combustion turbines would be fuel flexible, allowing them to burn LNG, propane, or fuel oil. VIWAPA completed conversion of the main units on St. Croix in 2016, but outright replacement of some units in St. Thomas appears to be still ongoing.117 The USVI government has implemented a goal of reducing petroleum use by 60% by 2025,118 and VIWAPA has targeted a 40% reduction in fossil fuel use by increasing the efficiency of power generation and by reducing power consumption. While switching to propane is expected to reduce emissions and fuel costs, propane contains less energy than diesel fuel and produces less power output per unit of fuel.

Renewable Energy

Most Caribbean islands have potential for development of renewable resources. Development of renewable sources in the USVI has been studied for several years with assistance from DOE and various national laboratories, focusing on solar, wind, and bioenergy resources (e.g., waste-to-energy and landfill gas facilities). In 2009, the USVI government passed an initiative requiring 30% of the territory's "peak demand capacity" to be served by renewable sources by 2025.119 Before the 2017 hurricanes, solar photovoltaic (PV) facilities provided most of the renewable capacity in the territory, largely through public-private partnerships.

The USVI's first large solar facility was a 450-kilowatt array at King Airport on St. Thomas. By 2017, [VI]WAPA was regularly obtaining 1% to 2% of its electricity on St. Thomas from solar power. The largest solar facilities are Estate Donoe on St. Thomas, inaugurated in 2015, and Estate Spanish Town, which opened on St. Croix in 2014. Both have more than 4 megawatts of capacity. Those projects are run by independent power producers (IPPs).... In addition, distributed (customer-sited, small-scale) solar generation on consumer rooftops is providing about 15 megawatts of generating capability.... Since 1990, the government has provided rebates for consumer-sited renewable facilities like solar PV panels, solar water heaters, and small wind turbines. Solar water heaters are required in all new construction and in major renovations. The USVI legislature directed American Recovery and Reinvestment Act [P.L. 111-5] funds to rebates for solar water heating systems, and nearly 1,500 systems were installed on the islands.120

Limited information is available on the status of the solar facilities after the hurricanes, although the AES Distributed Energy site at Estate Donoe on St. Thomas was reported to be damaged after Hurricane Irma.121

Despite some evaluations indicating the potential for utility scale wind development, siting and project costs have been issues, with the result that no such projects have been built to date.122 The largest wind turbine in the territory appears to be a 100 kW turbine on St. Croix.123

While plans for more ambitious waste-to-energy facilities have not been realized, a small landfill gas facility at the Bovoni landfill in St. Croix has operated for a few years; however, the landfill has been scheduled to close in 2019 under a consent decree with the U.S. EPA in response to environmental violations at the site.124

In 2016, VIWAPA held public meetings to gain input on an Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) to identify future system options, including the further use of renewables in its generation portfolio, and potential regional interconnections.125

Potential Considerations for Congress

Hurricanes Irma and Maria damaged approximately 80% to 90% of the transmission and distribution systems in the USVI. The USVI estimates that total uninsured hurricane-related damages will likely exceed $7.5 billion (including but not limited to electrical system damage). Prior to the release of the USVI's recovery funding request, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) submitted an additional request for fiscal year (2018) funding for $44 billion to address ongoing recovery efforts in multiple states and territories hit by Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria.126 The $44 billion supplemental request does not include the final funding requirements requested by the territories. Congress may consider appropriating supplemental funds above the Administration's request of $44 billion, as recovery cost estimates subsequently provided by Puerto Rico and the USVI exceed the amount requested by OMB for all states and territories affected by disasters in 2017.127 Congress may want to also consider options to assist the territories with comprehensive energy planning to develop modern and resilient electric power systems.

USVI Recovery for the Energy Sector: Mitigation and Resiliency

Of the $7.5 billion requested by the USVI, the total request for the energy sector is $850 million. The USVI estimated that for the energy sector request approximately $550 million would be requested from FEMA, while $300 million would be requested from the Department of Housing and Urban Development's Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery Grants (CDBG-DR) program.128 The requested funds for the energy sector would be directed to repair the grid (estimated at approximately $300 million), increase system resiliency to extreme weather (estimated at another $300 million), and provide backup generation (estimated at $250 million).129

Risk mitigation for outages involves performing routine and necessary maintenance of systems and equipment, and mitigating circumstances, such as vegetation management. The resiliency effort would attempt to mitigate damage to components of the T&D systems which were impaired. This would involve undergrounding of electric distribution for key feeder lines serving 10,000 residential customers and numerous critical facilities (e.g., police, fire, hospitals, government offices, and port terminals). About $48 million would be used to replace wooden poles with composite poles to harden overhead systems for main trunks of transmission and distribution feeders. Pole-mounted transformers would be replaced by pad-mounted transformers at an estimated cost of $10 million. Mitigation would include an emergency power generation system for St. John.

A further $250 million is proposed for emergency backup power systems. Improvements are proposed to harden onsite generators at key facilities to ensure continuity of operations, and to acquire portable generators for noncritical and temporary staging areas or base camps.

Legislation in the 115th Congress

Several bills have been introduced in the 115th Congress that would provide disaster assistance to impacted areas from the 2017 hurricanes. OMB requested $44 billion in supplemental funds in November; on December 21, 2017, the House passed an $81 billion emergency aid bill to help rebuild communities that were affected by the hurricanes and wildfires in 2017 (H.R. 4667, FY2018 Further Supplemental for Disaster Assistance for Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria and 2017 Wildfires and Other Purposes). As part of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123), $89.3 billion in additional emergency disaster relief was enacted. This appropriation is in addition to P.L. 115-56 and P.L. 115-72, two supplemental appropriations enacted in response to 2017 hurricanes.130

In the Senate, S. 2165—Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands Equitable Rebuild Act of 2017—would provide disaster recovery assistance specifically for the territories impacted by Hurricanes Irma and Maria.

Congress may consider other legislative action in addition to federal disaster assistance. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 (P.L. 109-58) amended 48 U.S.C 1492 to authorize DOE and DOI to provide technical and financial assistance to insular area governments. Assistance under DOI authority includes grants for power line projects designed to protect the system from damage caused by hurricanes and typhoons. Congress may consider providing appropriations to facilitate energy planning or improving system resiliency. Congress may also consider changes to existing authorizations addressing federal assistance for energy planning and rebuilding or modernizing the electric power systems of insular areas. Further, Congress may consider legislation to enable debt adjustments for the USVI and other territories not covered by the provisions of the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA; P.L. 114-187).

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

The U.S. Virgin Islands include the main islands of Saint Croix, Saint John, and Saint Thomas, which comprise the three administrative districts. These three districts also include smaller islands. The USVI is an insular area of the United States and is located approximately 45 miles east of Puerto Rico. |

| 2. |

National Weather Service (NWS), "Hurricane Irma Intermediate Advisory Number 30A," September 6, 2017, http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/2017/al11/al112017.public.030.shtml. |

| 3. |

NWS, "Major Hurricane Maria—September 20, 2017." http://www.weather.gov/sju/maria2017. |

| 4. |

Government of the U.S. Virgin Islands, U.S. Virgin Islands Hurricane Recovery Funding Request, November 2017. |

| 5. |

The Virgin Islands Water and Power Authority refers to itself as "WAPA." This report uses the acronym "VIWAPA" to distinguish it from other entities that also use "WAPA." |

| 6. |

VIWAPA, "Virgin Islands WAPA 9-21 Status Update," September 21, 2017, http://www.viwapa.vi/news/Hurricane_Restoration_Updates/Update_Details/17-09-21/Virgin_Islands_WAPA_9-21_Status_Update.aspx. |

| 7. |

A definition for "eligible customers" is not provided. Government of the U.S. Virgin Islands, "U.S. Virgin Islands Rings in New Year with over 90 Percent of Power Restored," press release, January, 10, 2018, http://informusvi.com/u-s-virgin-islands-rings-in-new-year-with-over-90-percent-of-power-restored/. |

| 8. |

In this case, "eligible" customers are described as those able "to receive power at this time based on surveys of the condition of each customer meter and/or structure." DOE, "Hurricanes Maria and Irma January 31 Event Summary," Report #89, January 31, 2018, https://energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2018/01/f47/Hurricanes%20Maria%20and%20Irma%20Event%20Summary%20January%2031%2C%202018.pdf. |

| 9. |

Andrew Scurria, "Hurricane Irma Adds New Fiscal Strain for U.S. Territories," The Wall Street Journal, September 8, 2017, https://www.wsj.com/articles/hurricane-irma-adds-new-fiscal-strain-for-u-s-territories-1504822406. For further information on Puerto Rico's economic and fiscal situation, see CRS Report R44095, Puerto Rico's Current Fiscal Challenges, by [author name scrubbed]. For further discussion of Puerto Rico's electric power system, see CRS Report R45023, Repair or Rebuild: Options for Electric Power in Puerto Rico, by [author name scrubbed], [author name scrubbed], and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 10. |

Andrew Scurria, "U.S. Virgin Islands Utility to Test Bond Market," The Wall Street Journal, May 11, 2017, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-virgin-islands-utility-to-test-bond-market-1494513445. |

| 11. |

BDO USA, Electric System of the Virgin Islands Water and Power Authority, Management's Discussion and Analysis, Financial Statements, Required Supplemental Information and Supplemental Schedule, Years Ended June 30, 2016 and 2015, June 27, 2017. Also see "WAPA Has the Solution, But Can It Get the Financing?" St. Croix Source, May 18, 2017. |

| 12. |

United States Virgin Islands Bureau of Economic Research, Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy for the United States Virgin Islands 2009, https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/uploads/USVI-CEDS-2009-2.pdf. |

| 13. |

Office of Insular Affairs of the Department of the Interior, "U.S. Virgin Islands," https://www.doi.gov/oia/islands/virgin-islands. Also see CIA Factbook, Virgin Islands, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/print_vq.html. |

| 14. |

USVI does not participate in the Local Area Unemployment program of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, so unemployment rates may be less precisely estimated than for the mainland. See USVI Office of the Governor, Bureau of Economic Research, "U.S. Virgin Islands Annual Economic Indicators," December 2016, http://www.usviber.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/ECON16-december.pdf. GAO reported that the closure of the refinery in 2012 resulted in a loss of 2,000 jobs on St. Croix and that the unemployment rate was 10.3% in April 2017. See U.S. GAO, U.S. Territories: Public Debt Outlook, GAO-18-160, October 2, 2017, p. 53, https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-160. |

| 15. |

The USVI estimate is from the 2010 Census. For Puerto Rico and the U.S. average, see U.S. Census Bureau, Household Income for States: 2008 and 2009, ACSBR/09-2, September 2010, by Amanda Noss; https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2010/acs/acsbr09-2.pdf. |

| 16. |

U.S. Virgin Islands Bureau of Economic Research, Economic Review, p. 3, March 2017, http://www.usviber.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Economic-Review-March-2017.pdf. Five-year 2015 American Community Survey (ACS) estimates were used for Puerto Rico and the U.S. average. U.S. average is determined from surveys within the 50 states and the District of Columbia. |

| 17. |

See McIntyre/IMF (2016), op cit. Also see USVI WAPA, "What's in My Electric Rates?" February 2017; http://www.viwapa.vi/Customers/RatesFees/Electric_Rate.aspx. In early 2017, USVI residential electrical rates were about $0.33/kWh compared to a U.S. average of $0.13/kWh. See U.S. DOE, EIA, USVI Energy Profile and Energy Estimates, January 18, 2018, https://www.eia.gov/state/data.php?sid=VQ#Prices. |

| 18. |

Office of Insular Affairs of the Department of the Interior, "U.S. Virgin Islands," https://www.doi.gov/oia/islands/virgin-islands. |

| 19. |

Arnold McIntyre, et al., "Caribbean Energy: Macro-Related Challenges," IMF working paper 16-53, March 2016, pp. 11-12; https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2016/wp1653.pdf. |

| 20. |

Bill Kossler, "V.I. Budget Crisis Part 5: Weren't Rum Funds Supposed to Save Us?" St. John Source, May 8, 2017, https://stjohnsource.com/2017/05/08/v-i-budget-crisis-part-5-werent-rum-funds-supposed-to-save-us/. |

| 21. |

U.S. Virgin Islands Bureau of Economic Research, Economic Review, p. 3, March 2017, http://www.usviber.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Economic-Review-March-2017.pdf. |

| 22. |

Kossler, B., "The V.I. Budget Crisis: Part 2, The Hovensa Effect," St. Croix Source, April 16, 2017, https://stcroixsource.com/2017/04/16/the-v-i-budget-crisis-part-2-the-hovensa-effect/. |

| 23. |

Jason Bronis, "Hovensa LLC to Shut Virgin Islands Oil Refinery Owned by Hess Corp. and Venezuela's PDVSA," Associated Press, January 18, 2012. |

| 24. |

The name appears to derive from Hess Oil and Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. See Hess Corporation, History of Hess Corporation, website: http://www.hess.com/company/hess-history. |

| 25. |

In re Hovensa LLC, Voluntary Petition, Case 1:15-bk-10003-MFW, September 15, 2015. |

| 26. |

Governor Kenneth Mapp, State of the Territory Message, January 22, 2018, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1_-zu9pWaWkKVTjPoSNcMGn85x6n0JRlJ/view. |

| 27. |

Economic Review, op. cit. p. 4. |

| 28. |

Bill Kossler, "The V.I. Budget Crisis: Part 2, The Hovensa Effect," St. Croix Source, April 16, 2017, https://stcroixsource.com/2017/04/16/the-v-i-budget-crisis-part-2-the-hovensa-effect/. |

| 29. |

Economic Review, op. cit. p. 2. |

| 30. |

BDO USA, "Government of the U.S. Virgin Islands: Management's Discussion and Analysis, Financial Statements and Required Supplementary Information, Year Ended September 30, 2016," June 27, 2017, https://emma.msrb.org/ER1068028-ER836665-ER1237555.pdf. Also see Bill Kossler, "The V.I. Budget Crisis, Part 3: The GERS Time Bomb," St. Croix Source, April 24, 2017, https://stcroixsource.com/2017/04/24/the-v-i-budget-crisis-part-3-the-gers-time-bomb/. |

| 31. |

For example, see Simone Baribeau, "United States Virgin Islands Risks Capsizing Under Weight of Debt," Forbes, January 23, 2017; and "Welcome to the Virgin Islands: One of the Most Indebted Places in the US," Wall Street Journal, January 26, 2017. A Moody's estimate put total debt at $1.97 billion: see Moody's Investor's Service, Credit Opinion: U.S. Virgin Islands (Government of), January 24, 2017. |

| 32. |

Ernice Gilbert, "Fitch, Moody's and Now S&P Downgrades USVI Bonds as Territory Barrels Towards Financial Collapse," The Virgin Islands Consortium, January 26, 2017, http://viconsortium.com/business/fitch-moodys-now-sp-downgrades-usvi-bonds-territory-barrels-towards-financial-collapse/. A listing of credit ratings agency announcements can be found at the Electronic Municipal Market Access website: https://emma.msrb.org. The USVI created an information portal to address those concerns, https://www.usvipfainvestorrelations.com/usvi-investor-relations-vi/financial-documents/i2880, although it had announced on August 25, 2017, that it would not report certain financial data to credit ratings agencies. See the "News" link at portal noted above. |

| 33. |

Moody's Investors Service, "Moody's Places US Virgin Islands' $1.2B Matching Fund Revenue Bonds on Review, Direction Uncertain," October 6, 2017. Also see Robert Slavin, "Virgin Islands Loses Its Rating From S&P," Bond Buyer, October 5, 2017. |

| 34. |

Ernice Gilbert, "Moody's Downgrades USVI Bonds Further; Says Government May Need To Restructure Debt," The Virgin Islands Consortium, February 9, 2018, http://viconsortium.com/virgin-islands-2/moodys-downgrades-usvi-bonds-further-says-government-may-need-to-restructure-debt/. |

| 35. |

Bill Kossler, "The V.I. Budget Crisis: How Did We Get Here, How Do We Get Out?" St. Thomas Source, April 10, 2017, http://stthomassource.com/content/2017/04/10/the-v-i-budget-crisis-how-did-we-get-here-how-do-we-get-out/. For example, in 2010 the USVI Public Finance Agency issued a series of revenue bonds, some of which matured in ten years, proceeds of which were used to "finance certain operating expenses" and to refinance other debts. See Official Statement for the Virgin Islands Public Finance Authority Revenue Bonds Virgin Islands Matching Fund Loan Note Series 2010A, available at https://emma.mrsb.org. |

| 36. |

Moody's Investor's Service, Credit Opinion: U.S. Virgin Islands (Government of), January 24, 2017; and Fitch Ratings, "Fitch Downgrades U.S. Virgin Islands IDR and Rev Bonds; Ratings on Negative Watch," January 17, 2017. |

| 37. |

Ernice Gilbert, "Senate President Slams Administration for Failing to Meet Crucial Obligations; Senate to Convene to Create 'Stimulus Package,'" The Virgin Islands Consortium, March 16, 2017, http://viconsortium.com/business/senate-president-slams-administration-for-failing-to-meet-crucial-obligations-senate-to-convene-to-create-stimulus-package/. |

| 38. |

The Virgin Islands Consortium, "Facing Liquidity Crisis, Mapp Formally Submits Proposed 'Sin' Tax Measure To Senate Aimed At Curtailing Incessant Borrowing," January 24, 2017, http://viconsortium.com/business/facing-liquidity-crisis-mapp-formally-submits-proposed-sin-tax-measure-to-senate-aimed-at-curtailing-incessant-borrowing/. Also see Fitch Ratings, "Fitch Downgrades U.S. Virgin Islands IDR and Rev Bonds; Ratings on Negative Watch," January 17, 2017. |

| 39. |

The Virgin Islands Revenue Enhancement and Economic Recovery Act of 2017 (Bill 32-0005; Act 7987), http://www.legvi.org/vilegsearch/ShowPDF.aspx?num=7987&type=Act. |

| 40. |

James Gardner, "Not Willing to Take a Pay Cut, Mapp Says Government Will Have Funds Through September," St. Thomas Source, April 17, 2017, http://stthomassource.com/content/2017/03/23/not-willing-to-take-a-pay-cut-mapp-says-govemmentwill-have-funds-through-september/. |

| 41. |

Governor Kenneth Mapp, State of the Territory, January 22, 2018, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1_-zu9pWaWkKVTjPoSNcMGn85x6n0JRlJ/view. |

| 42. |

FEMA, "More than $456 Million in Disaster Assistance for the U.S Virgin Islands," press release NR 75, January 5, 2018, https://www.fema.gov/news-release/2018/01/05/more-456-million-disaster-assistance-us-virgin-islands. |

| 43. |

PROMESA does include a provision to cover other territories in the event that a final judicial order would otherwise nullify the act on uniformity grounds. |

| 44. |

Fitch Ratings, "Fitch Places U.S. Virgin Islands and Guam's Ratings on Rating Watch Negative," press release, July 6, 2016. |

| 45. |

Moody's Investors Service (Moody's), "Moody's downgrades VI WAPA's senior bond to Caa1 and subordinated bond to Caa2; outlook negative," press release, January 25, 2017. |

| 46. |