EPA’s Methane Regulations: Legal Overview

On March 28, 2017, President Trump signed Executive Order 13783, directing federal agencies to review existing regulations and policies that potentially burden the development or use of domestically produced energy resources. Acting pursuant to the order, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is reviewing and reconsidering several regulations issued during the Obama Administration that address methane emissions from various industrial sectors. Methane is a short-lived greenhouse gas (GHG) with a Global Warming Potential of more than 25 times carbon dioxide that is emitted from various industrial activities.

President Trump’s executive order specifically requires EPA to review the revised emission standards for new, modified, and reconstructed equipment, processes, and activities of the oil and natural gas sector issued by the Obama Administration in June 2016. EPA issued these standards for methane and volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions pursuant to Section 111 of the Clean Air Act (CAA). Based on its review and in response to several administrative petitions for reconsideration, EPA is now reconsidering certain emission requirements from the June 2016 rule, which remain in effect unless EPA finalizes a proposed two-year stay of these requirements or otherwise repeals those requirements.

In addition, EPA is reconsidering the emission standards and guidelines for new and existing municipal solid waste (MSW) landfills updated by the Obama Administration in August 2016. In those rules, EPA issued the updated and revised emission standards for MSW landfills built after 2014 to further reduce emissions, including methane emissions. The agency also revised emission guidelines established in 1996 for existing landfills operating prior to that date. At this time, the 2016 landfill rules are in effect. EPA has not formally proposed any revisions to the 2016 rules or initiated a public comment period for any issues under reconsideration.

EPA’s review of the oil and natural gas sector and landfill methane rules has influenced the pending judicial challenges to the various 2016 rules. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit granted EPA’s requests to pause the judicial challenges of both rules to allow EPA to complete its review of them. In addition, stakeholders have successfully challenged in court EPA’s attempts to stay the various requirements that the agency is currently reconsidering. Judicial review of EPA’s attempts to stay rules in effect could more broadly impact the Trump Administration’s efforts to similarly stay other rules that are under reconsideration.

This report examines the statutory authority for issuing the methane regulations, legal challenges to the standards, and legal issues related to the reconsideration and stay of the regulations.

EPA's Methane Regulations: Legal Overview

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- Regulations Under CAA Section 111

- Reconsideration of Regulations Under CAA Section 307

- Regulations Targeting Methane Emissions from Oil and Gas Operations

- Updating and Revising 2012 Emission Standards

- Information Collection for Existing Oil and Natural Gas Sources

- Reconsideration of the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs

- EPA's Stays for the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs and Resulting Litigation

- Three-Month Stay of Certain Requirements

- Proposed Two-Year Stay

- Petitions for Judicial Review

- Litigation Issues

- Endangerment Finding Under CAA Section 111(b)

- Scope of the Oil and Gas Source Category

- Next Steps

- Regulations Targeting Methane Emissions from Municipal Landfills

- Reconsideration of 2016 MSW Landfill NSPSs and Emission Guidelines

- Stay of the MSW Landfill NSPSs and Emission Guidelines

- Petitions for Review of the 2016 MSW Landfill Emission Guidelines

- Litigation Issues

- EPA's Authority to Revise Section 111(d) Emission Guidelines

- Next Steps

Summary

On March 28, 2017, President Trump signed Executive Order 13783, directing federal agencies to review existing regulations and policies that potentially burden the development or use of domestically produced energy resources. Acting pursuant to the order, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is reviewing and reconsidering several regulations issued during the Obama Administration that address methane emissions from various industrial sectors. Methane is a short-lived greenhouse gas (GHG) with a Global Warming Potential of more than 25 times carbon dioxide that is emitted from various industrial activities.

President Trump's executive order specifically requires EPA to review the revised emission standards for new, modified, and reconstructed equipment, processes, and activities of the oil and natural gas sector issued by the Obama Administration in June 2016. EPA issued these standards for methane and volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions pursuant to Section 111 of the Clean Air Act (CAA). Based on its review and in response to several administrative petitions for reconsideration, EPA is now reconsidering certain emission requirements from the June 2016 rule, which remain in effect unless EPA finalizes a proposed two-year stay of these requirements or otherwise repeals those requirements.

In addition, EPA is reconsidering the emission standards and guidelines for new and existing municipal solid waste (MSW) landfills updated by the Obama Administration in August 2016. In those rules, EPA issued the updated and revised emission standards for MSW landfills built after 2014 to further reduce emissions, including methane emissions. The agency also revised emission guidelines established in 1996 for existing landfills operating prior to that date. At this time, the 2016 landfill rules are in effect. EPA has not formally proposed any revisions to the 2016 rules or initiated a public comment period for any issues under reconsideration.

EPA's review of the oil and natural gas sector and landfill methane rules has influenced the pending judicial challenges to the various 2016 rules. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit granted EPA's requests to pause the judicial challenges of both rules to allow EPA to complete its review of them. In addition, stakeholders have successfully challenged in court EPA's attempts to stay the various requirements that the agency is currently reconsidering. Judicial review of EPA's attempts to stay rules in effect could more broadly impact the Trump Administration's efforts to similarly stay other rules that are under reconsideration.

This report examines the statutory authority for issuing the methane regulations, legal challenges to the standards, and legal issues related to the reconsideration and stay of the regulations.

Introduction

On March 28, 2017, President Trump issued Executive Order 13783, which aims to promote the development or use of domestically produced energy resources.1 Among its specific provisions, the order rescinded the Obama Administration's "Climate Action Plan" (CAP).2 The CAP aimed to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases (GHGs), as well as to encourage adaptation to a changing climate.3 One of the interagency initiatives within the CAP, the "Strategy to Reduce Methane Emissions" (Methane Strategy), focused on the control of methane emissions, a short-lived climate pollutant with a Global Warming Potential4 of more than 25 times CO2.5

President Trump's order also requires agencies to review their existing regulations and "appropriately suspend, revise, or rescind those that unduly burden" domestic energy production and use.6 The order specifically requires the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to review the revised volatile organic compounds (VOCs)7 and GHG (namely methane) emission standards for new, modified, and reconstructed equipment, processes, and activities of the oil and natural gas sector issued by the Obama Administration in June 2016.8 EPA issued these emission standards pursuant to Section 111 of the Clean Air Act (CAA) and the Methane Strategy.9 Upon review of the standards and several administrative petitions for reconsideration, EPA has now decided to reconsider certain requirements in the emissions standards for the oil and natural gas sector.10

Although the methane emission standards and guidelines for new and existing municipal solid waste (MSW) landfills are not specifically mentioned in Executive Order 13783, EPA has also reviewed and is currently reconsidering several requirements of the MSW landfill emission standards and guidelines that the Obama Administration updated in August 2016.11

EPA's review of the oil and natural gas sector and landfill methane rules has influenced several judicial challenges to the Obama-era rules. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (D.C. Circuit) granted EPA's requests to pause the judicial challenges to allow EPA to complete its review of the regulations.12 In addition, EPA has attempted to stay the requirements that are being reconsidered by the agency, but courts have restricted the agency's ability to stay such requirements.13

This report examines the statutory authority for issuing the various methane regulations, legal challenges to the standards, and legal issues related to the reconsideration and stay of these regulations. The report begins by providing a general legal background of CAA Section 111 and Section 307 requirements for reconsidering rules, before addressing the oil and natural gas sector rules and the MSW landfill methane rules.

Background

Regulations Under CAA Section 111

EPA issued the regulations addressing methane emissions from oil and natural gas sources and MSW landfills pursuant to CAA Section 111. Section 111 directs EPA to list categories of stationary sources that cause or contribute significantly to "air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare."14 Once EPA lists a source category (e.g., "crude oil and natural gas production"), Section 111(b) requires EPA to establish "standards of performance" (known as new source performance standards, or NSPSs) for new, modified, and reconstructed sources within a listed source category.15 A "standard of performance" is defined as an air pollution emission standard that reflects the "best system of emission reduction" (BSER) that has been "adequately demonstrated."16 In determining the BSER, EPA must take into account the cost of achieving the emission reductions; non-air quality health and environmental impacts; and energy requirements of the regulated sources.17

At the same time or after the Section 111(b) standards are issued for new, modified, and reconstructed sources, EPA must issue a "procedure" requiring states to submit plans that establish standards of performance for existing sources in a source category, under certain conditions.18 EPA refers to these Section 111(d) procedures as "emission guidelines" that states are required to follow when they develop plans to implement standards of performance for existing sources in their jurisdictions.19 Congress established a single definition for standards of performance promulgated pursuant to Sections 111(b) and 111(d), requiring EPA to consider the same factors when establishing standards of performance for both new, modified, reconstructed sources and existing sources.20

Section 111(d)(1)(A) limits EPA's authority to issue Section 111(d) emission guidelines for existing sources. Based on its interpretation of Section 111 under the Obama Administration, for any air pollutant to which a Section 111(b) NSPS applied for new, modified, or reconstructed sources, EPA was required to regulate the same pollutant under Section 111(d) for existing sources unless that air pollutant was already regulated as (1) a "criteria pollutant" under the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) program21 or (2) a "hazardous air pollutant" (HAP) under the National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP) program.22 For example, because GHGs such as methane are not considered "criteria pollutants" under the NAAQS or HAPs under the CAA, EPA reasoned that it had authority under Section 111(d) to address methane emissions from existing MSW landfills once it had issued NSPSs for methane emission standards for new, modified, and reconstructed sources in those categories.23 However, EPA's interpretation and scope of its authority under Section 111(d) are currently subject to judicial challenge.24

Prior to 2016, EPA had issued Section 111(d) emission guidelines to address the following:

- GHG emissions from existing fossil fuel-fired power plants (known as the Clean Power Plan, or CPP);25

- VOC and methane emissions from MSW landfills;26

- organics, metals, and nitrogen oxides from municipal waste combustor units;27

- acid mist from sulfuric acid production units;28

- air pollutants from hospital/medical/infectious waste incinerators;29

- fluoride emissions from phosphate fertilizer plants;30

- reduced sulfur emissions from kraft pulp mills;31 and

- fluoride emissions from primary aluminum plants.32

Reconsideration of Regulations Under CAA Section 307

Under CAA Section 307(d)(7)(B), EPA must convene a reconsideration proceeding if the petitioner meets certain conditions.33 The petitioner must demonstrate that the objection to the final rule could not have been raised during the public comment period for the proposed rule, and the EPA Administrator must conclude that the "objection is of central relevance to the outcome of the rule."34 In granting reconsideration, EPA must provide the "same procedural rights as would have been afforded had the information been available at the time the rule was proposed," such as public notice and comment.35 If EPA denies the petition for reconsideration, the petitioner may seek judicial review of the denial.36

Further, under Section 307(d)(7)(B), EPA's reconsideration of a rule does not automatically postpone the effectiveness of the rule unless EPA or a court stays the rule for up to three months during the reconsideration.37 In other words, if EPA determines that it must convene a reconsideration proceeding, the agency or a court may grant a stay of the effectiveness of the rule for a limited period of three months.38

As discussed below, EPA has granted reconsideration for specific requirements in the oil and natural gas sector and landfill methane rules and has issued three-month stays of the effective dates of those requirements for the rules.39

Regulations Targeting Methane Emissions from Oil and Gas Operations40

Updating and Revising 2012 Emission Standards

The crude oil and natural gas sector is one of the highest-emitting industrial sectors of methane and VOCs in the United States.41 In 2012, EPA issued a final rule setting standards of performance to limit emissions of VOCs from new, modified, and reconstructed sources in the oil and gas industry pursuant to CAA Section 111(b) (2012 Oil and Gas NSPSs).42 In an effort to achieve the Obama Administration's goal of reducing methane emissions from the oil and gas sector and to respond to petitions for reconsideration of the 2012 NSPS to address methane emissions,43 EPA proposed a rule revising and updating the 2012 NSPS in August 2015.44 After receiving over 900,000 comments, the agency issued the final rule on June 3, 2016 (2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs).45

EPA's final rule amended the 2012 Oil and Gas NSPSs, expanding the emission sources covered by the rule and establishing performance standards for GHGs (i.e., methane limitations) from a number of oil and gas emission sources.46 The final rule established, among other things,

- methane and VOC standards for emission sources and equipment not regulated under the 2012 Oil and Gas NSPSs, including hydraulically fractured oil well completions; pneumatic pumps; and fugitive emissions47 from well sites and compressor stations; and

- methane emission standards for hydraulically fractured gas well completions and equipment leaks at natural gas processing plants that are currently regulated under the 2012 Oil and Gas NSPSs for VOC, but not for methane emissions.48

The final rule took effect on August 2, 2016, and applied only to equipment, processes, and activities in the production, processing, transmission, and storage phases of oil and natural gas systems constructed or modified after July 17, 2014; it did not apply to distribution entities.49 EPA noted that while the new methane standards cover many sources, those sources already complying with the 2012 Oil and Gas NSPSs would not likely be required to install additional emissions controls, as VOC controls also curb methane emissions.50 EPA estimated that the standards for new and modified sources are expected to reduce 510,000 short tons of methane in 2025, with estimated costs of $530 million and "climate benefits" of $690 million by 2025.51

Information Collection for Existing Oil and Natural Gas Sources

As discussed above, the release of the final 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs under CAA Section 111(b) triggered EPA's duty to issue Section 111(d) emission guidelines for existing oil and natural gas sources covered under the 111(b) rule.52 In 2016, EPA sent an Information Collection Request (ICR) to oil and natural gas companies seeking information on their existing oil and gas sources as a first step to regulating their methane emissions.53 Effective March 2, 2017, EPA withdrew the ICR to assess the need for this information and to reduce the burden on businesses during this assessment.54 The ICR withdrawal was issued shortly after nine state attorneys general and two governors submitted a letter to EPA, asking that the ICR be suspended and withdrawn.55 EPA has not announced when or if it will reissue the ICR. Several states, cities, and environmental groups have sent EPA notices of intent to sue the agency, alleging that EPA failed to perform "its nondiscretionary duty" to issue emission guidelines limiting methane and VOC emissions from existing sources in the oil and natural gas sector.56

Reconsideration of the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs

In April and June 2017, EPA granted administrative petitions for reconsideration of several aspects of the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs pursuant to CAA Section 307(d)(7)(B).57 On April 18, 2017, EPA granted petitions to reconsider (1) the application of fugitive emissions requirements to low production well sites, and (2) the process and criteria used for requesting and approving the use of alternative means of emission limitations (AMEL)—an equivalent and enforceable state emissions limit—to comply with the fugitive emissions requirements.58 EPA determined that the final rule subjected low production wells to fugitive emissions requirements based on information and rationale that differed significantly from the proposal, making it "impracticable" for petitioners to object to these requirements during the public comment period.59 Similarly, EPA determined that petitioners did not have the opportunity to object or comment on the AMEL process and criteria because these provisions were introduced for the first time in the final rule.60 Because these fugitive emission requirements relate directly to whether and how they apply to certain sources, EPA concluded that they are of "central relevance" to the outcome of the rule and granted reconsideration.61

In June 2017, EPA identified two other issues concerning the 2016 rule that, in the agency's view, met the Section 307(d)(7)(B) criteria for reconsideration.62 Petitioners sought reconsideration of provisions that require a professional engineer (PE) to certify (1) the proper design of closed vent systems63 and (2) "technical infeasibility" determinations to exempt a pneumatic pump at a well site from emission reduction requirements.64 EPA acknowledged that it failed to present costs associated with the PE certification requirements in the proposal and determined that these compliance requirements are of central relevance to the outcome of the rule.65 Thus, EPA has convened an administrative reconsideration proceeding to address these issues in addition to the fugitive emissions requirements.66

As part of the reconsideration proceeding, EPA plans to prepare a notice of proposed rulemaking that will provide the petitioners and the public an opportunity to comment on the rule requirements and associated issues identified above.67 EPA also intends to look broadly at the entire 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs, potentially indicating that EPA may revise other aspects of the emission standards. If EPA decides to revise the rule, CAA Section 307(d) requires that the agency follow the notice-and-comment rulemaking procedures that were used to promulgate the 2016 rule.68

EPA's Stays for the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs and Resulting Litigation

Three-Month Stay of Certain Requirements

As part of the reconsideration process, on June 5, 2017, EPA stayed parts of the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs: the fugitive emissions requirements,69 including the deadline for the initial monitoring survey, and other provisions related to the issues being reconsidered, until August 31, 2017.70 EPA issued the three-month stay pursuant to its authority under CAA Section 307(d)(7)(B) without public notice and comment.71 As discussed above, EPA or a court may stay the effectiveness of a rule for up to three months during the reconsideration once EPA grants reconsideration.72 Environmental groups filed a petition to review and an emergency motion to stop or vacate the three-month stay, arguing that EPA did not have authority to issue the stay.73

On July 3, 2017, the D.C. Circuit, in a 2-1 split decision, held that the "90-day stay was unauthorized under section 307(d)(7)(B) and thus unreasonable," vacating the stay.74 In its decision, the majority of the court first addressed EPA's claim that the court did not have jurisdiction to review the claim because the stay is a not a "final action."75 Under the CAA, judicial review is limited to "final action taken, by the [EPA] Administrator."76 In rejecting the argument, the majority explained that the "imposition of the stay is an entirely different matter" from the EPA's decision to reconsider the final rule, which was not a reviewable final agency action.77 The majority reasoned that "EPA's stay . . . is essentially an order delaying the rule's effective date, and this court has held that such orders are tantamount to amending or revoking a rule."78 The stay, the majority concluded, was a reviewable "final agency position" on the effective date of the rule that "affects regulated parties' 'rights or obligations.'"79 In her dissent, Judge Janice Rogers Brown disagreed, arguing that the stay was not a final agency action because the stay (1) "facilitates" the reconsideration of the requirements and does not "resolve them"; and (2) does not compel compliance or impose "legal or practical requirements on anyone."80

After concluding that it had jurisdiction to review the stay, the majority of the court considered whether EPA had authority to issue the stay.81 The majority rejected EPA's argument that the agency had "inherent" authority to issue the stay, explaining that EPA "may act only pursuant to authority delegated to them by Congress."82 Further, the majority noted that EPA did not rely on its inherent authority, but purported to act pursuant to Section 307(d)(7)(B), a statute that, in the majority's view, "clearly delineates" that EPA is authorized to issue a three-month stay only if the agency was required to reconsider the rule.83 Therefore, the majority reasoned that it must review EPA's reconsideration decision because "[u]nder CAA section 307(d)(7)(B), . . . the stay EPA imposed is lawful only if reconsideration was mandatory."84

The court concluded that the reconsideration was not mandatory because the petitioners did not object to an issue that was impracticable to raise during the public comment period.85 The court determined that the industry groups petitioning for an administrative reconsideration had "ample opportunity to comment on all four issues" under reconsideration as evidenced by EPA directly addressing those comments in the final rule.86 Because it was not "impracticable" to raise those issues during the comment period, the majority of the court held that EPA was not required under Section 307(d)(7)(B) to grant reconsideration and therefore not authorized to issue the three-month stay.87 As a result, the majority concluded that EPA's decision to impose the stay was "arbitrary" and "capricious," and the court granted the motion to vacate the stay.88 Once the stay was vacated, the formerly stayed requirements went back into effect.89

Judicial review of EPA's attempts to stay rules already in effect could have broader effects on the Trump Administration's efforts to similarly stay or postpone requirements in other rules that are under reconsideration.90 The majority's decision to vacate the three-month stay of the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs may affect future cases that challenge EPA's authority under CAA Section 307(d)(7)(B) to issue a three-month stay when reconsidering a rule.91 In holding that EPA does not have inherent authority to issue temporary stays, the majority of the court limits EPA's authority to issue a three-month stay under Section 307(d)(7)(B) to circumstances when the agency is required to reconsider a rule.92

Further, some federal agencies that have attempted to use the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) to stay rules in effect have been struck down by the courts. For example, a federal district court granted summary judgment to plaintiffs that alleged that the Bureau of Land Management violated the APA when the Bureau temporarily postponed the compliance dates for certain sections of the rule regulating methane emissions from oil and natural gas production activities on public lands after the rule's effective date had already passed.93

Proposed Two-Year Stay

Before the D.C. Circuit issued its decision regarding EPA's authority to issue the three-month stay of the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs, EPA also proposed to further extend the three-month stay of the fugitive emissions requirements, well site pneumatic standards, and closed vent certification requirements for two years—until September 12, 2019.94 In the proposal, EPA stated that the longer stay is "necessary" to provide sufficient time to complete its reconsideration of these requirements through the public notice-and-comment process.95 However, the proposal did not identify the legal authority that permits EPA to issue the stay; nor did the agency rely on Section 307(d)(7)(B) for the longer stay. The public comment period for the proposed stay closed on August 9, 2017.96

After reviewing comments submitted by stakeholders, EPA, on November 8, 2017, issued a notice of data availability (NODA) for the proposed stay.97 The NODA seeks comment on additional information, ideas, and issues stakeholders raised regarding EPA's legal authority to issue the stay and challenges in implementing the stayed requirements.98 For example, EPA is seeking comment on its legal authority to stay or extend the compliance periods for the requirements under reconsideration.99 EPA argues that these proposed actions to stay or extend the compliance deadlines are "lawful exercises" of the agency's "inherent" authority to reconsider, revise, replace, or repeal past decisions and its general rulemaking authority under Section 301(a) of the CAA,100 which authorizes EPA "to prescribe such regulations as are necessary to carry out [its] functions" under the Act.101 The public comment period for the NODAs closed December 8, 2017.102

Petitions for Judicial Review

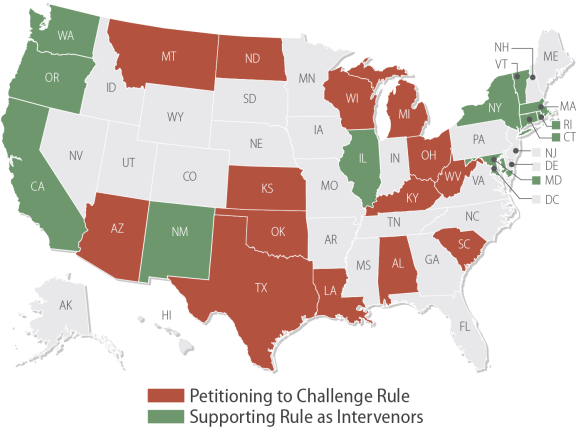

Although EPA is reconsidering the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs, the underlying rule is also being challenged in court. Prior to the start of the Trump Administration, North Dakota,103 Texas (including the Railroad Commission of Texas and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality as named parties),104 a coalition of 13 states (including several state agencies),105 and various gas associations filed petitions for review of the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs.106 Eleven states, the city of Chicago, and various environmental advocacy groups intervened on behalf of EPA to support the final rule.107 (See Figure 1.) All petitions have been consolidated with the lead case, North Dakota v. EPA.108 In May 2017, the court granted EPA's request to hold the case in abeyance while the agency reviews the rule.109

Litigation Issues

Before the litigation was paused, the petitioners filed their preliminary statements of the legal issues110 that will be raised in the litigation.111 The final statement of issues will be presented in the petitioners' briefs,112 which have yet to be filed. This report does not aim to provide a comprehensive preview of the potential legal arguments that may be presented to the court for or against EPA's final rule. The sections below highlight some potential issues that may be raised in litigation, including a challenge to EPA's authority to issue the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs.

Endangerment Finding Under CAA Section 111(b)

CAA Section 111 requires EPA to first establish a list of source categories to be regulated, and then establish emission standards for new sources in that source category.113 Section 111(b)(1)(A) requires that a source category be included on the list if, "in [the EPA Administrator's] judgment it causes, or contributes significantly to, air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare."114 EPA commonly refers to this determination as an "endangerment finding."115 In 1979, EPA listed "crude oil and natural gas production" as a source category under Section 111 based on its "endangerment finding."116

Several of the petitioners' statements of issues claimed that EPA failed to make the required "endangerment finding" for methane from the oil and gas sector under CAA Section 111.117 One petitioner argued that EPA is required under Section 111(b) to make "endangerment findings" for particular pollutants such as methane that it seeks to regulate for listed source categories.118

In the final rule, EPA relied primarily on its previous 1979 "endangerment finding" for the "crude oil and natural gas production" source category as its authority to issue new and updated NSPSs for methane and VOC emissions.119 In the response to comments section of the final rule, EPA reasoned that the agency did not need to make a separate "endangerment finding" for methane because the "2009 Endangerment Finding [for motor vehicles] that defines the aggregate group of six well-mixed [GHGs] as the air pollution addresses emissions of any individual component of that aggregate group and, therefore, supports the rational basis for this final rule."120 EPA reiterated that the GHG is the "regulated pollutant," and the standards are expressed in form of limitations on methane emissions.121 The final rule also included a new "endangerment finding" based on previous and new scientific analyses, and stated that "to the extent such a finding were necessary, pursuant to section 111(b)(1)(A), the Administrator hereby determines that, in her judgment, this source category, as defined above, contributes significantly to air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare."122 Petitioners also seek to litigate whether the new "endangerment finding" is an arbitrary and capricious determination, prohibited by the CAA.123

Scope of the Oil and Gas Source Category

Several petitioners also argued that EPA has "unlawfully" expanded the listed "crude oil and natural gas production" source category to additional types of emission sources not previously regulated, such as hydraulically fractured oil well completions; pneumatic pumps; and fugitive emissions from well sites and compressor stations.124 As discussed above, CAA Section 111 requires EPA to establish a list of source categories to be regulated if EPA determines that the source category "causes, or contributes significantly to, air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare."125 One petitioner argued in its comments on the proposed rule that EPA's 1979 original source category determination for "crude oil and natural gas production" cannot "be read to include the numerous smaller emissions points by this proposal. The 1979 listing was focused on major-emitting operations and cannot be reasonably construed as encompassing small, discrete sources that are separate and apart from a large facility, like a processing plant."126

In the final rule, EPA claimed that the rule did not expand the oil and gas source category. The agency reasoned that 1979 source category listing of "crude oil and natural gas production" broadly covered the natural gas industry including production, processing, transmission, and storage of oil and natural gas.127 EPA pointed to the 1979 source category listing analysis that indicated that the agency previously evaluated emissions from various segments of the natural gas industry, such as production and processing.128 The agency explained that it provided notice in the rulemaking that smaller sources emitting less than 100 tons of emissions could be subject to NSPSs even though the 1979 listing of the "crude oil and natural gas production" was classified under the "major source categories."129 EPA also highlighted the 1984 proposed NSPSs to limit VOC emissions from specific equipment in the natural gas production industry to support the broad scope of the oil and natural gas source category.130 The 1984 proposal defined the crude oil and natural gas production industry to include "the operations of exploring for crude oil and natural gas products, drilling for these products, removing them from beneath the earth's surface, and processing these products from oil and gas fields for distribution to petroleum refineries and gas pipelines."131

However, EPA appeared to acknowledge the concerns and perceived ambiguity regarding the scope of the oil and gas category source. In the final rule, EPA stated that

[T]o the extent that there is any ambiguity in the prior listing, the EPA hereby finalizes, as an alternative, its proposed revision of the category listing to broadly include the oil and natural gas industry. As revised, the listed oil and natural gas source category includes oil and natural gas production, processing, transmission, and storage. In support, the EPA has included in this action the requisite finding under section 111(b)(1)(A) that, in the Administrator's judgment, this source category ... contributes significantly to air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.132

If the litigation moves forward, the court will most likely address whether this alternative category revision is necessary or sufficient under Section 111.

Next Steps

On May 18, 2017, the court granted EPA's request to hold the cases in abeyance as EPA reviews and reconsiders the rule.133 Until a stay is finalized, the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs remain in effect. EPA has not issued any further notices regarding the reconsideration proceeding for the rule. See Table 1 below for the current status of the oil and gas sector methane rules.

|

Regulatory Action |

Status of the Regulatory Action (as of January 2018) |

Status of Litigation on Regulatory Action (as of January 2018) |

|

2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs 81 Fed. Reg. 35,824 (June 3, 2016) |

In effect, but under reconsideration |

Held in abeyance North Dakota v. EPA, No. 16-1242, (D.C. Cir. May 18, 2017) |

|

Three-Month Stay: 82 Fed. Reg. 25,730 (June 5, 2017) |

Vacated by D.C. Circuit (July 31, 2017) |

D.C. Circuit ruled, 2-1, to vacate Clean Air Council v. Pruitt, 862 F.3d 1 (D.C. Cir. 2017) |

|

Proposed Two-Year Stay: 82 Fed. Reg. 27,645 (June 16, 2017) |

Public comment period closed on August 9, 2017 |

N/A |

|

Notice of Data Availability for the Proposed Two-Year Stay 82 Fed. Reg. 51,788 (Nov. 8, 2017) |

Public comment period closed on December 8, 2017 |

N/A |

|

2016 Proposed Information Collection Request for Existing Oil and Gas Facilities 81 Fed. Reg. 35,763 (June 3, 2016) |

Withdrawn (March 2, 2017) |

N/A |

Source: Prepared by CRS from regulatory and litigation filings.

Notes: This table does not include all CAA regulations that affect the oil and gas sector.

a. EPA also proposed a three-month stay to cover the gap period from when the two-year delay is finalized to its effective date pursuant to the Congressional Review Act. Oil and Natural Gas Sector: Emission Standards for New, Reconstructed, and Modified Sources: Three Month Stay of Certain Requirements, Proposed Rule, 82 Fed. Reg. 27,641 (June 16, 2017).

Regulations Targeting Methane Emissions from Municipal Landfills

Landfills emit gas that contains methane, carbon dioxide, and more than 100 different nonmethane organic compounds (NMOCs), such as vinyl chloride, toluene, and benzene.134 In 1996, EPA listed municipal solid waste (MSW) landfills as a CAA Section 111 category of stationary sources that causes or contributes significantly to air pollution that may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.135 In addition to listing MSW landfills as a source category, EPA, at that same time, issued NSPSs for new, modified, and reconstructed MSW landfills pursuant to Section 111(b) and emission guidelines for existing landfills pursuant to Section 111(d) to address NMOCs and methane emissions.136 In response to a consent decree resolving a lawsuit137 and the Obama Administration's Methane Strategy, in 2014 EPA proposed updates to the 1996 MSW landfill NSPSs and sought public comments on whether EPA should update the companion emission guidelines for existing landfills.138 Over 20 years after the original NSPSs and emission guidelines were issued, EPA published on August 29, 2016, its updated NSPSs to reduce landfill gas emissions from MSW landfills built, modified, or reconstructed after July 17, 2014.139 The agency also revised the 1996 emission guidelines for existing landfills operating prior to that date.140

The updated NSPSs aimed to further decrease methane emissions from MSW landfills. The revised NSPSs maintained the current design capacity applicability threshold for new or modified landfills at 2.5 million metric tons (MMT) of design capacity (or 2.5 million cubic meters of waste).141 The updated NSPSs lowered the emission threshold that triggers requirements to capture landfill gas emissions (including methane) from the current 50 metric tons of NMOCs per year to 34 metric tons.142 Under the rule, EPA would have required that a gas collection control system be installed and operational within 30 months after landfill gas emissions reach 34 metric tons of NMOCs or more per year.143 The rule also updated monitoring requirements; expanded approved uses for treated landfill gas; and included other clarifications and updated definitions.144 According to an agency fact sheet, 115 new, modified, or reconstructed landfills would be subject to the emission control requirements of the revised standards by 2025.145

Similar to the revised NSPSs, the revised emission guidelines for existing landfills built prior to July 17, 2014, would have required active landfills that emit more than 34 metric tons of NMOCs annually to install landfill gas collection and control systems.146 Closed landfills would remain subject to the 1996 threshold of 50 metric tons per year when determining when controls must be installed or can be removed.147

As a result of the lower threshold for active landfills, EPA estimated that the emission control requirements will apply to 731 existing open and closed landfills, as compared to 638 facilities currently subject to the 1996 emission control requirements.148 Both rules became effective on October 28, 2016 and remain in effect unless EPA finalizes a stay or revises the rules.149

Reconsideration of 2016 MSW Landfill NSPSs and Emission Guidelines

In May 2017, EPA granted administrative petitions for reconsideration of several requirements in the revised and updated MSW landfill NSPSs and emission guidelines based on the criteria under CAA Section 307(d)(7)(B).150 Under the Trump Administration, EPA found that the petitioners "demonstrated that it was impractical to raise the objection during the period for public comment" on a number of issues,151 including Tier 4 surface emissions monitoring.152 The 2016 MSW landfill NSPSs and emission guidelines added Tier 4 surface emissions monitoring procedures that would allow certain landfills that would have exceeded the applicability threshold for emission control requirements using other approved modeling procedures (i.e., Tiers 1 and 2) to use, as an alternative, surface monitoring to determine applicability.153 A landfill that demonstrates that surface emissions are below 500 parts per million for four consecutive quarters using Tier 4 monitoring procedures would not be required to install emissions control technology even if Tiers 1 or 2 modeling calculations indicated that the landfill exceeded the applicability threshold.154

EPA highlighted the petitioners' objection to the Tier 4 surface emission monitoring as meeting the Section 307(d)(7)(B) criteria for reconsideration. EPA explained that the final rule imposed restrictions on the use of the optional Tier 4 surface emissions monitoring method that were not included in the proposed rule and were "added without the benefit of public comment."155 EPA also determined that the objection to the Tier 4 monitoring limitations were of central relevance to the rule because they reduced "flexibility" to use the optional monitoring method.156 Based on these determinations, EPA has convened an administrative reconsideration proceeding to address the issues and objections raised by the petitioners.157 As part of the reconsideration proceeding, EPA plans to prepare a notice of proposed rulemaking that will provide the petitioners and the public an opportunity to comment on the rule requirements and associated issues identified above.158

Stay of the MSW Landfill NSPSs and Emission Guidelines

In addition to granting reconsideration of the issues discussed above, EPA stayed for three months the effectiveness of both MSW landfills NSPSs and emission guidelines, in their entirety, starting from May 31 until August 29, 2017, pursuant to its authority under Section 307(d)(7)(B).159 EPA reasoned that staying all requirements of the rules was necessary because the Tier 4 monitoring provisions in the two rules are "integral to how the rules function as a whole."160 Because this three-month stay expired on August 29, 2017, the 2016 rules are currently in effect during the reconsideration process. At this time, EPA has not formally proposed a longer stay of the rules or initiated the public comment period for issues under reconsideration.

Similar to their challenge to the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs stay, environmental groups filed a petition to review and a motion to vacate the three-month stay of the MSW landfills NSPSs and emission guidelines in the D.C. Circuit.161 Although the court denied the petitioners' motion to vacate the stay,162 the court is moving forward with briefing of the case and has asked the parties to address standing and mootness now that the three-month stay has expired.163 The final briefs in the case are due on February 26, 2018.164

The petitioners' litigation issues mirror those raised in the challenge to the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs stay, arguing that EPA exceeded its authority under Section 307(d)(7)(B) because the agency failed to meet preconditions for mandatory reconsideration.165 The petitioners also claim that the stay is arbitrary and capricious because the stay of both regulations in their entirety is "overbroad" relative to the "narrow" issues under reconsiderations.166

Petitions for Review of the 2016 MSW Landfill Emission Guidelines

Although EPA is reconsidering the 2016 MSW landfills emission guidelines, the guidelines themselves are being challenged in court.167 Prior to the start of the Trump Administration, industry trade associations and waste management and recycling companies challenged EPA's 2016 revised emission guidelines for existing MSW landfills in the D.C. Circuit.168 On June 14, 2017, the court granted EPA's request to hold the case in abeyance while the agency reviews and reconsiders the rule.169

Litigation Issues

Although the litigation is on hold, the petitioners have submitted preliminary statements of issues that challenge EPA's authority to revise emission guidelines. Among the various legal arguments raised, petitioners make a unique and potentially far-reaching challenge to EPA's authority to revise emission guidelines issued under Section 111(d) of the CAA.

EPA's Authority to Revise Section 111(d) Emission Guidelines

Petitioners challenging the landfill emission guidelines question whether EPA has the authority to revise the 1996 emission guidelines for existing MSW landfills under CAA Section 111(d).170 The core of the legal argument is whether Section 111(d) implicitly allows EPA to revise and update emission standards. Pursuant to CAA Section 111(b), EPA is required to "at least every 8 years review and, if appropriate, revise" NSPSs for new, modified, and reconstructed sources.171 However, Section 111(d) does not include a similar mandated review period for emission guidelines for existing sources.172 EPA's implementing regulations for Section 111(d) emission guidelines only address revisions to the agency's determination regarding adverse public health effects that may alter compliance times under the guidelines and require states to make corresponding revisions to their state plans.173

Under the Obama Administration, EPA asserted in the 2016 landfill emission guidelines' preamble that the agency "is not statutorily obligated to conduct a review of the Emission Guidelines, but has the discretionary authority to do so when circumstances indicate that it is appropriate."174 EPA reasoned that this is a permissible interpretation of the CAA, and "is consistent with the gap filling nature of section 111(d)" to regulate air pollutants and sources not addressed in other sections of the CAA.175 EPA argued that it would be "illogical" for the agency to be precluded from requiring existing sources to update air pollution controls when the BSER will change over time as these sources continue to operate for decades.176

In support of this position, EPA highlighted jurisprudence that has recognized the power of regulatory agencies to reassess and revise promulgated rules even without an express statutory mandate to make such a revision.177 The Supreme Court, for example, has stated that "[r]egulatory agencies do not establish rules of conduct to last forever; they are supposed, within the limits of the law and of fair and prudent administration, to adapt their rules and practices to the Nation's needs in a volatile, changing economy."178 EPA, under the Trump Administration, is making a similar argument to support delaying and extending the compliance timelines for the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs.179 The agency contends that it has the "inherent authority to reconsider past decisions and to revise, replace, or repeal a decision to the extent permitted by law and supported by a reasoned explanation."180

EPA's authority to revise Section 111(d) emission guidelines has not been questioned previously because this was the agency's first attempt to do so. Some argue in comments on the proposed emission guidelines that Congress's explicit mandate authorizing EPA to review and potentially revise Section 111(b) NSPSs for new, modified, and reconstructed every eight years demonstrates that Congress knew how to provide for such review and revision and intentionally did not provide a similar provision with respect to Section 111(d) emission guidelines.181 One commentator has pointed out that the Supreme Court has held that "where Congress includes particular language in one section of a statute but omits it in another section of the same Act, it is generally presumed that Congress acts intentionally and purposely in the disparate inclusion or exclusion."182 In contrast, EPA argued in the revised emission guidelines that "[h]ad Congress intended to preclude the EPA from updating the emission guidelines to reflect changes, it would surely have specifically said so, something it did not do."183

The legislative history of CAA Section 111 does not discuss the eight-year review for NSPSs under Section 111(b) or review of emission guidelines under Section 111(d). The history does provide some discussion regarding the need for EPA to look to currently available and evolving techniques in determining what constitutes the BSER that has been adequately demonstrated for standards of performance and emission guidelines. For example, when amending the CAA in 1970, the Senate Public Works Committee stated that "[t]he performance standards should be met through application of the latest available emission control technology or through other means of preventing or controlling air pollution."184 The committee also stated that "standards of performance are not static," and that they "should provide an incentive for industries to work toward constant improvement in techniques for preventing and controlling emissions from stationary sources."185 In a report regarding the 1977 CAA amendments, the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee reiterated that "[i]n passing the Clean Air Amendments of 1970, the Congress for the first time imposed a requirement for specified levels of control technology.... This requirement sought to assure the use of available technology and to stimulate the development of new technology."186 This history appears to suggest that EPA can broadly review and revise the "standards of performance," a term of art that applies to both Section 111(b) NSPSs and Section 111(d) emission guidelines,187 to ensure that the standards reflect the improvement of systems of emission reduction.

In addition, a reference to Section 110 procedures in Section 111(d) raises questions as to whether Congress intended for EPA to revise emission guidelines and state plans in a similar manner as Section 110. Specifically, Section 111(d) requires EPA to "prescribe regulations which shall establish a procedure similar to that provided by section 110 under which each State shall submit to the [EPA] Administrator a plan which ... establishes standards of performance for any existing source for any air pollutant."188 In turn, CAA Section 110 requires states to adopt and submit to EPA for approval state implementation plans (SIPs) that provide for the "implementation, maintenance, and enforcement" of NAAQS promulgated by EPA under CAA Section 109.189 EPA is required to review the NAAQS every five years.190 If EPA decides to revise the NAAQS, states are required to revise their SIPs to implement and enforce the revised NAAQS.191

It could be argued that this regulatory scheme is similar to Section 111(d) because emission guidelines are implemented through state plans. Once EPA sets guidelines for standards of performance for existing sources under Section 111(d), states are required to submit to EPA for approval a plan to implement and enforce the standards of performance for existing sources.192 Therefore, it could be argued that in referencing Section 110 in Section 111(d), Congress may have intended to allow EPA to revise Section 111(d) guidelines and state plans in the same manner that NAAQS and SIPs are allowed to be revised in Section 109 and Section 110, respectively.

However, Section 110 and 111(d) are not completely analogous. In both cases, state plan revisions are necessary when the standards are revised because the state is the primary implementation and enforcement authority; but unlike Section 111(d), Section 110 revisions are triggered through a statutorily mandated five-year review under Section 109.193 In contrast, Congress did not mandate a review and revision cycle for Section 111(d) emission guidelines for existing sources.

If the case moves forward, a ruling upholding EPA's implicit authority to review and revise Section 111(d) guidelines could support future EPA review and revision of other Section 111(d) emission guidelines to require additional emission reductions for existing sources based on a new analysis of the BSER.194

Next Steps

The litigation challenging the substantive requirements of the MSW landfill emission guidelines is currently on hold pending EPA's review and reconsideration.195 See Table 2 below for the current status of the landfill methane rules.

|

Regulatory Action |

Status of the Regulatory Action (as of January 2018) |

Status of Litigation on Regulatory Action |

|

2016 MSW Landfill NSPSs 40 C.F.R. pt. 60, subpt. XXX |

In effect for MSW landfills constructed, modified, or reconstructed after July 17, 2014, but under reconsideration Stayed from May 31, 2017, until Aug. 29, 2017 |

N/A |

|

2016 MSW Landfill Emission Guidelines 40 C.F.R. pt. 60, subpt. Cf |

In effect for MSW landfills constructed, modified, or reconstructed before July 17, 2014, but under reconsideration Stayed from May 31, 2017, until August 29, 2017 |

Held in abeyance Nat'l Waste & Recycling Ass'n v. EPA, No. 16-1371 (D.C. Cir. June 14, 2017) |

|

Three-Month Stay: 2016 MSW Landfill Rules 82 Fed. Reg. 24,878 (May 31, 2017) |

Expired on August 29, 2017 |

Litigation moving forward Briefs due in February 2018 |

Source: Prepared by CRS from regulatory and litigation filings.

Note: This table does not include all CAA regulations that affect MSW landfills.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

See Exec. Order No. 13783, 82 Fed. Reg. 16, 093 (Mar. 31, 2017) (signed on Mar. 28, 2017). For additional information on the order, see CRS Legal Sidebar WSLG1789, New Executive Order Directs Agencies to Revise or Rescind Climate Change Rules and Policies, by Linda Tsang. |

| 2. |

Exec. Order No. 13783, § 3(b)(i)-(ii). |

| 3. |

Exec. Off. of the President, The President's Climate Action Plan (2013), https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/image/president27sclimateactionplan.pdf. For additional background on the Climate Action Plan, see CRS Report R43120, President Obama's Climate Action Plan, coordinated by Jane A. Leggett. |

| 4. |

The Global Warming Potential (GWP) is a metric EPA has adopted to compare the climate impacts of different gases. Understanding Global Warming Potentials, Envtl. Prot. Agency, https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/understanding-global-warming-potentials (last visited Jan. 18, 2018). The GWP measures the total energy the emissions of 1 ton of a gas will absorb over a given period of time, relative to the emissions of 1 ton of CO2. Id. |

| 5. |

Methane (CH4) is estimated to have a GWP of 28–36 over 100 years. Id. EPA's Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks and Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Reporting Program follow the international GHG reporting standards under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which requires the use of GWP values from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's (IPCC's) Fourth Assessment Report, published in 2007. Id. The report lists a GWP of 25 for methane. IPCC, Fourth Assessment Report: Climate Change (2007), https://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg1/en/ch2s2-10-2.html. For additional information on methane and its GWP, see CRS Report R43860, Methane: An Introduction to Emission Sources and Reduction Strategies, coordinated by Richard K. Lattanzio; CRS Report R43860, Methane: An Introduction to Emission Sources and Reduction Strategies, coordinated by Richard K. Lattanzio; and CRS Report R42986, Methane and Other Air Pollution Issues in Natural Gas Systems, by Richard K. Lattanzio. |

| 6. |

Exec. Order No. 13783, § 1(c). |

| 7. |

EPA defines a volatile organic compound (VOC) as "any compound of carbon, excluding carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, carbonic acid, metallic carbides or carbonates and ammonium carbonate, which participates in atmospheric photochemical reactions." Technical Overview of Volatile Organic Compounds, Envtl. Prot. Agency, https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/technical-overview-volatile-organic-compounds#definition (last visited Jan. 18, 2018). |

| 8. |

Id. § 7. |

| 9. |

Oil and Natural Gas Sector: Emission Standards for New, Reconstructed, and Modified Sources, Final Rule, 81 Fed. Reg. 35,824 (June 3, 2016) (codified at 40 C.F.R. pt. 60, subpts. OOOO and OOOOa) [hereinafter 2016 Oil & Gas NSPSs]; 42 U.S.C. § 7411. |

| 10. |

See infra "Reconsideration of the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs." |

| 11. |

See infra "Reconsideration of 2016 MSW Landfill NSPSs and Emission Guidelines." |

| 12. |

Per Curiam Order, North Dakota v. EPA, No. 16-1242 (D.C. Cir. May 18, 2017); Clerk's Order, North Dakota v. EPA, Nat'l Waste & Recycling Ass'n v. EPA, No. 16-1371 (D.C. Cir. June 14, 2017). |

| 13. |

See infra "EPA's Stays for the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs and Resulting Litigation" and "Stay of the MSW Landfill NSPSs and Emission Guidelines." |

| 14. |

42 U.S.C. § 7411(b)(1)(A). For example, EPA added "municipal solid waste landfills" as a Section 111 source category "because, in the judgement of the [EPA] Administrator, it contributes significantly to air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health and welfare." Standards of Performance for New Stationary Sources and Guidelines for Control of Existing Sources: Municipal Solid Waste Landfills, 61 Fed. Reg. 9,905, 9,906 (Mar. 12, 1996). See also Priority List and Additions to the List of Categories of Stationary Sources; Final Rule, 44 Fed. Reg. 49,222, 49,226 (Aug. 21, 1979) (listing "crude oil and natural gas production" as a source category under Section 111). Once EPA has promulgated new standards, states are allowed to develop and submit to EPA for approval a procedure for implementing and enforcing the standards of performance for new, modified, or reconstructed stationary sources. 42 U.S.C. § 7411(b)(6). If the state procedure is approved, EPA will delegate implementation and enforcement authority to the state. Id. |

| 15. |

42 U.S.C. § 7411(b)(1)(A). |

| 16. |

Id. § 7411(a). |

| 17. |

Id. For additional information regarding how the courts have interpreted BSER, see CRS Report R43699, Key Historical Court Decisions Shaping EPA's Program Under the Clean Air Act, by Linda Tsang and Alexandra M. Wyatt. |

| 18. |

42 U.S.C. § 7411(d)(1). EPA used its authority under Section 111(d) to issue the Clean Power Plan (CPP) to regulate GHG emissions from existing power plants. See generally Carbon Pollution Emission Guidelines for Existing Stationary Sources: Electric Utility Generating Units, Final Rule, 80 Fed. Reg. 64,661 (Oct. 23, 2015). |

| 19. |

42 U.S.C. § 7411(d)(1). Section 111(d) directs EPA to establish state plan procedures similar to Section 110 of the CAA, which requires states to develop and revise implementation plans to achieve EPA's national ambient air quality standards (NAAQS) and subsequent changes to those standards. Id.; see also id. § 7410. |

| 20. |

Compare id. § 7411(b)(1)(B) (requiring EPA to establish "standards of performance"), with id. § 7411(d)(1) (requiring EPA to establish a procedure "under which each State shall submit ... a plan which ... establishes standards of performance for any existing source"). The definition of "standards of performance" is provided under 42 U.S.C. § 7411(a)(1), and applies to the provisions under Section 111. |

| 21. |

42 U.S.C. §§ 7408-7410. |

| 22. |

Id. § 7412. |

| 23. |

See e.g., 2016 Landfill Emission Guidelines, supra note 140, at 59,277-78. |

| 24. |

For discussion of litigation related to Section 111(d)'s limits on EPA's authority, see CRS Report R44480, Clean Power Plan: Legal Background and Pending Litigation in West Virginia v. EPA, by Linda Tsang and Alexandra M. Wyatt. |

| 25. |

40 C.F.R. pt. 60, subpt. UUUU. For more information about the CPP, see CRS Report R44341, EPA's Clean Power Plan for Existing Power Plants: Frequently Asked Questions, by James E. McCarthy et al., and CRS Report R44480, Clean Power Plan: Legal Background and Pending Litigation in West Virginia v. EPA, by Linda Tsang and Alexandra M. Wyatt. |

| 26. |

40 C.F.R. pt. 60, subpt. Cf. |

| 27. |

Id. pt. 60, subpt. Cb. |

| 28. |

Id. pt. 60, subpt. Cd. |

| 29. |

Id. pt. 60, subpt. Ce. CAA Section 129 requires EPA to issue Section 111(d) emission guidelines for air pollution from hospital/medical/infectious waste incinerators. 42 U.S.C. § 7429(b). |

| 30. |

Phosphate Fertilizer Plants: Final Guideline Document Availability, 42 Fed. Reg. 12,022 (Mar. 1, 1977). |

| 31. |

Kraft Pulp Mills; Final Guideline Document; Availability, 44 Fed. Reg. 29,828 (May 22, 1979). |

| 32. |

Primary Aluminum Plants; Availability of Final Guideline Document, 45 Fed. Reg. 26,294 (April 17, 1980). In addition, EPA's 2005 Clean Air Mercury Rule (CAMR) delisted coal-fired power plants from CAA Section 112 and, instead, established a cap-and-trade system for mercury under Section 111(d). 70 Fed. Reg. 28,606 (May 18, 2005). The D.C. Circuit vacated CAMR in 2008 on grounds unrelated to the guidelines' substantive requirements. See New Jersey v. EPA, 517 F.3d 574, 581-84 (D.C. Cir. 2008) (holding that EPA's delisting of the source category from Section 112 was unlawful and that EPA was obligated to promulgate standards for mercury and other hazardous air pollutants under Section 112). |

| 33. |

42 U.S.C. § 7607(d)(7)(B). |

| 34. |

See id. ("If the person raising an objection can demonstrate to the [EPA] Administrator that it was impracticable to raise such objection within such time or if the grounds for such objection arose after the period for public comment (but within the time specified for judicial review) and if such objection is of central relevance to the outcome of the rule, the Administrator shall convene a proceeding for reconsideration of the rule and provide the same procedural rights as would have been afforded had the information been available at the time the rule was proposed."). |

| 35. |

Id. |

| 36. |

Id. |

| 37. |

42 U.S.C. § 7607(d)(7)(B). |

| 38. |

Id. |

| 39. |

See infra "Reconsideration of the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs" and "Reconsideration of 2016 MSW Landfill NSPSs and Emission Guidelines." |

| 40. |

In addition to the EPA's regulation of methane emissions from oil and gas sources operated by private entities, the Department of the Interior's (DOI's) Bureau of Land Management (BLM) issued a rule in 2016 to replace existing guidance and regulations issued 30 years prior under the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 that would have reduced methane emissions from oil and natural gas production activities on public lands. Waste Prevention, Production Subject to Royalties, and Resource Conservation, 81 Fed. Reg. 83,008 (Nov. 18, 2016). For information on the BLM methane rule, see CRS Legal Sidebar WSLG1806, UPDATE: BLM Venting and Flaring Rule Survives (For Now), by Linda Tsang, and CRS Report R42986, Methane and Other Air Pollution Issues in Natural Gas Systems, by Richard K. Lattanzio. |

| 41. |

For further information regarding air pollutants emitted from the oil and gas sector, see CRS Report R42986, Methane and Other Air Pollution Issues in Natural Gas Systems, by Richard K. Lattanzio. |

| 42. |

Oil and Natural Gas Sector: New Source Performance Standards and National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants Reviews; Final Rule, 77 Fed. Reg. 49,542 (Aug. 16, 2012) (codified at 40 C.F.R. pt. 60, subpt. OOOO). |

| 43. |

See e.g., Clean Air Council et al., Petition for Reconsideration, In the Matter of: Final Rule Published at 77 FR 49490 (Aug. 16, 2012), titled "Oil and Gas Sector: New Source Performance Standards and National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants Reviews; Final Rule," Docket ID No. EPA–HQ–OAR–2010–0505, RIN 2060–AP76 (2012). |

| 44. |

Oil and Natural Gas Sector: Emission Standards for New and Modified Sources; Proposed Rule, 80 Fed. Reg. 56,593 (Sept. 18, 2015). |

| 45. |

2016 Oil & Gas NSPSs, supra note 9, at 35,840, 35,848. |

| 46. |

Id. at 35,825. |

| 47. |

EPA defines fugitive emissions as "methane losses can occur from leaks ... in all parts of the [natural gas] infrastructure, from connections between pipes and vessels, to valves and equipment." Id. |

| 48. |

Id. at 35,825-26. |

| 49. |

Id. at 35,843-48. |

| 50. |

EPA, EPA's Actions to Reduce Methane Emissions from the Oil and Natural Gas Industry: Final Rules and Draft Information Collection Request 2 (2016), https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-09/documents/nsps-overview-fs.pdf. |

| 51. |

2016 Oil & Gas NSPSs, supra note 9, at 35,827. |

| 52. |

See supra "Regulations Under CAA Section 111." |

| 53. |

Proposed Information Collection Request; Comment Request; Information Collection Effort for Oil and Gas Facilities, 81 Fed. Reg. 35,763 (June 3, 2016). |

| 54. |

Notice Regarding Withdrawal of Obligation To Submit Information, 82 Fed. Reg. 12,817 (Mar. 7, 2017). |

| 55. |

Letter from Ken Paxton, Att'y. Gen., Texas, et al., to Scott Pruitt, Admin., EPA (Mar. 1, 2017), https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2017-03/documents/letter_from_attorneys_general_and_governors.pdf |

| 56. |

Letter from Peter Zalzal, Envtl. Def. Fund, et al., to E. Scott Pruitt, Admin., EPA (Aug. 28, 2017), https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2017-09/documents/edf_noi_08282017.pdf; Letter from Eric T. Schneiderman, Att'y Gen., et al., to Scott Pruitt, Admin., EPA (June 29, 2017), https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2017-07/documents/states_noi_06292017.pdf. |

| 57. |

Oil and Natural Gas Sector: Emission Standards for New, Reconstructed, and Modified Sources; Grant of Reconsideration and Partial Stay, 82 Fed. Reg. 25,730, 25,731-32 (June 5, 2017). See supra "Reconsideration of Regulations Under CAA Section 307" for discussion of Section 307(d)(7)(B) requirements for reconsideration. |

| 58. |

82 Fed. Reg. at 25,730. |

| 59. |

Id. |

| 60. |

Id. |

| 61. |

Id. |

| 62. |

Id. at 25,731-32. |

| 63. |

See id. at 25,732 (arguing that EPA failed to present costs associated with requiring a PE to certify the design and capacity of closed vent systems used to comply with the emission standards in the 2016 Oil and Gas NSPS). |

| 64. |

See id. (arguing that EPA did not propose that a PE must certify technical infeasibility determinations to qualify for an exemption for certain pneumatic pumps). |

| 65. |

Id. |

| 66. |

Id. |

| 67. |

Id. |

| 68. |

42 U.S.C. § 7607(d). |

| 69. |

The 2016 Oil and Gas NSPSs required regulated entities to conduct an "initial monitoring survey" to identify fugitive emissions at new well sites and compressor stations by June 3, 2017. 40 C.F.R. § 60.5397a(f); 2016 Oil & Gas NSPSs, supra note 9, at 35,824. |

| 70. |

82 Fed. Reg. at 25,732-33. |

| 71. |

Id. |

| 72. |

42 U.S.C. § 7607(d)(7)(B). See supra "Reconsideration of Regulations Under CAA Section 307" for discussion of Section 307(d)(7)(B) stay requirements. |

| 73. |

Petition for Review, Clean Air Council v. Pruitt, No. 17-1145 (D.C. Cir. June 5, 2017); Petitioners' Emergency Motion for a Stay or in the Alternative, Summary Vacatur, No. 17-1145 (D.C. Cir. June 5, 2017). |

| 74. |

Clean Air Council v. Pruitt, 862 F.3d 1, 8 (D.C. Cir. 2017) (per curiam). |

| 75. |

Id. at 6. |

| 76. |

42 U.S.C. § 7607(b)(1). |

| 77. |

Clean Air Council, 862 F.3d at 6. |

| 78. |

Id. |

| 79. |

Id. at 7 (internal citations omitted). |

| 80. |

Id. at 14-17 (Brown, J., dissenting). |

| 81. |

Id. at 8 (majority opinion). In her dissent, Judge Brown did not reach the issue of whether EPA had authority to issue the stay. Id. at 18 (Brown, J., dissenting). |

| 82. |

Id. at 9 (majority opinion). |

| 83. |

Id. |

| 84. |

Id. at 9. |

| 85. |

Id. at 14. |

| 86. |

Id. |

| 87. |

Id. |

| 88. |

Id. Ten days after its decision, the court granted EPA's request to recall the mandate, and allowed the stay to remain in effect for two weeks (until July 17, 2017) in order to give EPA time to determine whether it would appeal the decision to vacate the stay. Order, Clean Air Council v. Pruitt, No. 17-1145 (D.C. Cir. July 13, 2017). The court issued the mandate on July 31, 2017. Per Curiam Order, Clean Air Council v. Pruitt, No. 17-1145 (D.C. Cir. July 31, 2017). In an 8-3 vote, a majority of the court denied the petition for rehearing en banc filed by intervenor states and industry groups. Per Curiam Order, Clean Air Council v. Pruitt, No. 17-1145 (D.C. Cir. Aug. 10, 2017). |

| 89. |

See e.g., Action on Smoking & Health v. Civil Aeronautics Bd., 713 F.2d 795, 797 (1983) ("To 'vacate,' as the parties should well know, means 'to annul; to cancel or rescind; to declare, to make, or to render, void; to defeat; to deprive of force; to make of no authority or validity; to set aside.' Thus, by vacating or rescinding the recissions [sic] proposed by ER-1245, the judgment of this court had the effect of reinstating the rules previously in force.... "). |

| 90. |

See infra "Stay of the MSW Landfill NSPSs and Emission Guidelines." |

| 91. |

Id. |

| 92. |

Clean Air Council, 862 F.3d at 9. |

| 93. |

California v. Bureau of Land Mgmt., No. 17-cv-03804-EDL, 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 176620, at *13-14 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 4, 2017). |

| 94. |

Oil and Natural Gas Sector: Emission Standards for New, Reconstructed, and Modified Sources: Stay of Certain Requirements, 82 Fed. Reg. 27,645 (June 16, 2017) [hereinafter Proposed 2-year Stay of the 2016 Oil & Gas NSPSs]. Further, the agency also proposed a three-month stay to cover the gap period from when the two-year delay is finalized to its effective date pursuant to the Congressional Review Act. Oil and Natural Gas Sector: Emission Standards for New, Reconstructed, and Modified Sources: Three Month Stay of Certain Requirements, Proposed Rule, 82 Fed. Reg. 27,641 (June 16, 2017). In the proposal, EPA explains that if the two-year stay is finalized, it would likely be considered a "major rule" under the CRA. Id. at 27,642. Under the CRA, a major rule cannot take effect until 60 days after publication in the Federal Register or after Congress receives the rule report, whichever is later. 5 U.S.C. § 801(a)(3). Based on its expectation that courts are not likely to consider a three-month stay to be a major rule under the CRA, EPA anticipates that the three-month stay, if finalized, would take effect immediately upon its publication in the Federal Register and would stay the requirements for the period between the two-year stay's filing and effective dates. 82 Fed. Reg. at 27,642-43. |

| 95. |

Proposed 2-year Stay of the 2016 Oil & Gas NSPSs, 82 Fed. Reg. at 27,648. |

| 96. |

Id. |

| 97. |

Oil and Natural Gas Sector: Emission Standards for New, Reconstructed, and Modified Sources: Stay of Certain Requirements, Proposed rule; notice of data availability, 82 Fed. Reg. 51,788 (Nov. 8, 2017). EPA also issued a notice of data availability for the proposed three-month stay. Oil and Natural Gas Sector: Emission Standards for New, Reconstructed, and Modified Sources: Three Month Stay of Certain Requirements, Proposed rule; notice of data availability, 82 Fed. Reg. 51,794 (Nov. 8, 2017). |

| 98. |

Proposed 2-year Stay of the 2016 Oil & Gas NSPSs, 82 Fed. Reg. at 27,648. |

| 99. |

82 Fed. Reg. at 51,790. |

| 100. |

Id. |

| 101. |

42 U.S.C. § 7601(a). |

| 102. |

82 Fed. Reg. at 51,788; 82 Fed. Reg. at 51,794. |

| 103. |

Petition for Review, North Dakota v. EPA, No. 16-1242 (D.C. Cir. July 15, 2016). |

| 104. |

Petition for Review, Texas et al. v. EPA, No. 16-1257 (D.C. Cir. July 28, 2016). |

| 105. |

Petition for Review, West Virginia et al. v. EPA, No. 16-1264 (D.C. Cir. Aug. 2, 2016). Besides West Virginia, the state coalition includes Alabama, Arizona, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Attorney General Bill Schuette for the people of Michigan, Montana, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Wisconsin, Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet, and the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (NCDEQ). Id. On March 20, 2017, the court granted NCDEQ's motion to withdraw as a petitioner. Id. |

| 106. |

Petition for Review, W. Energy Alliance v. EPA, No. 16-1266 (D.C. Cir. Aug. 2, 2016); Petition for Review, Indep. Petroleum Ass'n of Am. et al. v. EPA, No. 16-1262 (D.C. Cir. Aug. 2, 2016); Petition for Review, Interstate Nat. Gas Ass'n, No. 16-1263 (D.C. Cir. Aug. 2, 2016); Petition for Review, GPA Midstream Gas Ass'n, No. 16-1267 (D.C. Cir. Aug. 2, 2016); Petition for Review, Texas Oil & Gas Ass'n, No. 16-1269 (D.C. Cir. Aug. 2, 2016); Petition for Review, Am. Petroleum Inst., No. 16-1270 (D.C. Cir. Aug. 2, 2016). |

| 107. |

See Clerk's Order, North Dakota v. EPA, No. 16-1242 (D.C. Cir. Dec. 19, 2016) (granting motion to intervene as respondents for the Clean Air Council, Earthworks, Environmental Defense Fund, Environmental Integrity Project, Natural Resources Defense Council, and Sierra Club; the States of California, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington; the Commonwealth of Massachusetts; and the City of Chicago). |

| 108. |

See Clerk's Order, North Dakota v. EPA, No. 16-1242 (D.C. Cir. Aug. 8, 2016). |

| 109. |

Per Curiam Order, North Dakota v. EPA, No. 16-1242 (D.C. Cir. May 18, 2017). |

| 110. |

See id.; D.C. Cir. R. 15(c). |

| 111. |

See e.g., Petitioner N.D.'s Statement of Issues to be Raised, North Dakota v. EPA, No. 16-1242 (D.C. Cir. Aug. 22, 2016) [hereinafter N.D. Statement of Issues]; Petitioner W. Energy Alliance's Non-Binding Statement of Issues to be Raised, North Dakota v. EPA, No. 16-1242 (D.C. Cir. September 1, 2016) [hereinafter WEA Statement of Issues]; Nonbinding Statement of Issues of the Am. Petroleum Inst., North Dakota v. EPA, No. 16-1242 (D.C. Cir. Sept. 6, 2016) [hereinafter API Statement of Issues]. |

| 112. |

D.C. Cir. R. 28(a)(5). |

| 113. |

42 U.S.C. § 7411(b)(1). |

| 114. |

Id. § 7411(b)(1)(A). |

| 115. |

2016 Oil & Gas NSPSs, supra note 9, at 35,828. |

| 116. |

Priority List and Additions to the List of Categories of Stationary Sources; Final Rule, 44 Fed. Reg. 49,222, 49,226 (Aug. 21, 1979). |

| 117. |

See N.D. Statement of Issues, supra note 111; WEA Statement of Issues, supra note 111; API Statement of Issues, supra note 111; Comments from Kathleen M. Sgamma, V.P. of Govt. & Public Aff., W. Energy Alliance, to Gina McCarthy, Admin., EPA (Dec. 4, 2015). |

| 118. |

API Statement of Issues, at 2; Comments from Howard Feldman, Sen. Dir., Am. Petroleum Inst., to Gina McCarthy, Admin., EPA (Dec. 4, 2015), at 5-6. |

| 119. |

2016 Oil & Gas NSPSs, supra note 9, at 35,833. |

| 120. |

Id. |

| 121. |

Id. at 35,877. |

| 122. |

Id. at 35,833. |

| 123. |

WEA Statement of Issues, supra note 111, at 2; API Statement of Issues, supra note 111 at 2. |

| 124. |

WEA Statement of Issues, supra note 111, at 2; API Statement of Issues, supra note 111, at 2; N.D. Statement of Issues, supra note 111, at 2. |

| 125. |

42 U.S.C. § 7411(b)(1)(A). |

| 126. |

API Comments, supra note 111, at 4. |

| 127. |

2016 Oil & Gas NSPSs, supra note 9, at 35,832. |

| 128. |

Id. |

| 129. |

Id. When the "crude oil and natural gas production" source category was listed in 1979, EPA defined a "major source category" as "those categories for which an average size plant has the potential to emit 100 tons or more per year of any one pollutant." Priority List and Additions to the List of Categories of Stationary Sources, 44 Fed. Reg. 49,222 (Aug. 21, 1979). EPA used the "major source" categories to rank and prioritize setting standards for the listed sources. Id. |

| 130. |

2016 Oil & Gas NSPSs, supra note 9, at 35,832. |

| 131. |

Standards of Performance for New Stationary Sources; Onshore Natural Gas Processing Plants In the Natural Gas Production Industry; Equipment Leaks of VOC; Proposed Rule and Notice of Public Hearing, 49 Fed. Reg. 2,636, 2,637 (Jan. 20, 1984). |

| 132. |

2016 Oil & Gas NSPSs, supra note 9, at 35,833. |

| 133. |

Per Curiam Order, North Dakota v. EPA, No. 16-1242 (D.C. Cir. May 18, 2017). |

| 134. |

Standards of Performance for New Stationary Sources and Guidelines for Control of Existing Sources: Municipal Solid Waste Landfills, 61 Fed. Reg. 9,905, 9,906 (Mar. 12, 1996). |

| 135. |

61 Fed. Reg. at 9,919 (codified at 40 C.F.R. § 60.16). |

| 136. |

61 Fed. Reg. at 9,905 (Mar. 12, 1996). |

| 137. |

Environmental Defense Fund filed a lawsuit, arguing that EPA failed to review the 1996 NSPS by the statutorily required deadline, which is every eight years pursuant to CAA Section 111(b). Envt'l Def. Fund v. EPA. No. 1:11-cv-04492 (S.D.N.Y. June 30. 2011). Under a consent decree resolving that lawsuit, EPA agreed to review the 1996 landfill NSPS and take final action on whether to revise them. Consent Decree, Envt'l Def. Fund v. EPA. No. 1:11-cv-04492 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 1, 2012). |

| 138. |