Softwood Lumber Imports from Canada: Current Issues

Softwood lumber imports from Canada have been a persistent concern for Congress for decades. Canada is an important trading partner for the United States, but lumber production is a significant industry in many states. U.S. lumber producers claim they are at an unfair competitive disadvantage in the domestic market against Canadian lumber producers because of Canada’s timber pricing policies. This has resulted in five major disputes (so-called lumber wars) between the United States and Canada since the 1980s.

The current dispute (Lumber V) started when the 2006 Softwood Lumber Agreement (SLA) expired on October 12, 2015. Under that agreement, Canadian softwood lumber shipped to the United States was subject to export charges and quota limitations when the price of U.S. softwood products fell below a certain level. After a year-long grace period, a coalition of U.S. lumber producers filed trade remedy petitions on November 25, 2016, which claimed that Canadian firms dump lumber in the U.S. market and that Canadian provincial forestry policies subsidize Canadian lumber production. These petitions subsequently were accepted by the two agencies that administer the trade remedy process: the International Trade Commission (ITC) and the International Trade Administration (ITA).

On December 7, 2017, the ITC determined that imports of softwood lumber, previously determined to be dumped and subsidized by ITA, caused material injury to U.S. producers. This means that ITA’s final duties in the anti-dumping (AD) and countervailing duty (CVD) proceedings, announced on November 2, 2017, can be imposed on affected Canadian lumber. ITA found subsidization of the Canadian industry and determined a subsidy margin of 3.34%-18.19% on Canadian lumber, depending on the firm. ITA found dumping margins of 3.20% to 8.89%, also firm dependent. Canada is challenging these trade remedy decisions at World Trade Organization and North American Free Trade Agreement tribunals.

Tension between the United States and Canada over the softwood lumber trade has been persistent and may be inevitable. Both countries have extensive forest resources, but they have quite different population levels and development pressures. Vast stretches of Canada are still largely undeveloped, whereas relatively fewer areas in the United States (outside Alaska) remain undeveloped. These differences have contributed to different forest management policies.

For decades, U.S. lumber producers have argued that they have been injured by subsidies given to their Canadian competitors in the form of lost market share and lost revenue. In the United States, the majority of the timberlands are privately owned; private markets dominate the allocation and pricing of timber, although federally owned forests are regionally significant. In Canada, forests are largely owned by the provincial governments and leased to private firms. The provinces establish the price of timber through a stumpage fee, a per unit volume fee charged for the right to harvest trees.

U.S. lumber producers argue that the stumpage fees charged by the Canadian provinces are subsidized, or priced at less than their market value, providing an unfair competitive advantage in supplying the U.S. lumber market. The Canadian provinces and lumber producers dispute the subsidy allegations. Directly comparing Canadian and U.S. lumber prices is difficult and often inconclusive, however, due to major differences in tree species, sizes, and grades; measurement systems; requirements for harvesters; environmental protection; and other factors.

The softwood lumber trade between the United States and Canada is of interest to Congress due to the controversy between Canadian and U.S. lumber producers and the larger implications it might have on trade between the two countries. The potential renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) may provide Congress an opportunity to weigh in on this issue, given its constitutional authority over trade policy, as well as authority granted under the 2015 Trade Promotion Authority (TPA). Congress may consider legislation or conduct oversight on these issues.

Softwood Lumber Imports from Canada: Current Issues

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Background

- Stakeholders in the U.S.-Canada Softwood Lumber Dispute

- U.S. Softwood Lumber Consumption

- Alleged Subsidies to Canadian Lumber Producers

- Different Land Ownership and Management Regimes

- Different Fee Systems

- History of the Dispute

- Lumber IV and the 2006 Softwood Lumber Agreement

- Lumber V

- Litigation

- U.S. Trade Remedy Action

- Trade Agreement Dispute Settlement

- Issues for Congress

- Summary and Conclusion

Figures

Tables

Appendixes

Summary

Softwood lumber imports from Canada have been a persistent concern for Congress for decades. Canada is an important trading partner for the United States, but lumber production is a significant industry in many states. U.S. lumber producers claim they are at an unfair competitive disadvantage in the domestic market against Canadian lumber producers because of Canada's timber pricing policies. This has resulted in five major disputes (so-called lumber wars) between the United States and Canada since the 1980s.

The current dispute (Lumber V) started when the 2006 Softwood Lumber Agreement (SLA) expired on October 12, 2015. Under that agreement, Canadian softwood lumber shipped to the United States was subject to export charges and quota limitations when the price of U.S. softwood products fell below a certain level. After a year-long grace period, a coalition of U.S. lumber producers filed trade remedy petitions on November 25, 2016, which claimed that Canadian firms dump lumber in the U.S. market and that Canadian provincial forestry policies subsidize Canadian lumber production. These petitions subsequently were accepted by the two agencies that administer the trade remedy process: the International Trade Commission (ITC) and the International Trade Administration (ITA).

On December 7, 2017, the ITC determined that imports of softwood lumber, previously determined to be dumped and subsidized by ITA, caused material injury to U.S. producers. This means that ITA's final duties in the anti-dumping (AD) and countervailing duty (CVD) proceedings, announced on November 2, 2017, can be imposed on affected Canadian lumber. ITA found subsidization of the Canadian industry and determined a subsidy margin of 3.34%-18.19% on Canadian lumber, depending on the firm. ITA found dumping margins of 3.20% to 8.89%, also firm dependent. Canada is challenging these trade remedy decisions at World Trade Organization and North American Free Trade Agreement tribunals.

Tension between the United States and Canada over the softwood lumber trade has been persistent and may be inevitable. Both countries have extensive forest resources, but they have quite different population levels and development pressures. Vast stretches of Canada are still largely undeveloped, whereas relatively fewer areas in the United States (outside Alaska) remain undeveloped. These differences have contributed to different forest management policies.

For decades, U.S. lumber producers have argued that they have been injured by subsidies given to their Canadian competitors in the form of lost market share and lost revenue. In the United States, the majority of the timberlands are privately owned; private markets dominate the allocation and pricing of timber, although federally owned forests are regionally significant. In Canada, forests are largely owned by the provincial governments and leased to private firms. The provinces establish the price of timber through a stumpage fee, a per unit volume fee charged for the right to harvest trees.

U.S. lumber producers argue that the stumpage fees charged by the Canadian provinces are subsidized, or priced at less than their market value, providing an unfair competitive advantage in supplying the U.S. lumber market. The Canadian provinces and lumber producers dispute the subsidy allegations. Directly comparing Canadian and U.S. lumber prices is difficult and often inconclusive, however, due to major differences in tree species, sizes, and grades; measurement systems; requirements for harvesters; environmental protection; and other factors.

The softwood lumber trade between the United States and Canada is of interest to Congress due to the controversy between Canadian and U.S. lumber producers and the larger implications it might have on trade between the two countries. The potential renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) may provide Congress an opportunity to weigh in on this issue, given its constitutional authority over trade policy, as well as authority granted under the 2015 Trade Promotion Authority (TPA). Congress may consider legislation or conduct oversight on these issues.

Since the 1980s, there have been five major disputes (so-called lumber wars) between the United States and Canada, interspersed by three different trade agreements.1 The latest dispute, Lumber V, started after the expiration of the 2006 Softwood Lumber Agreement (SLA) in October 2015.2 The U.S. lumber industry petitioned for trade protections shortly thereafter. This report provides background information on the dispute, summarizes the key issues leading to the tensions between the United States and Canada over softwood lumber, and examines current developments in Lumber V.

Background

Softwood lumber, for purposes of this report, is lumber produced from conifer trees. The definition of the term had been an issue leading up to the signing of the 2006 agreement and is discussed more thoroughly in the Appendix. The SLA definition is based on four tariff items under the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (HTSUS) and includes essentially all traditional softwood lumber items intended for residential construction.3 Because softwood lumber is primarily used for residential construction, repair, and remodeling, the demand for softwood lumber is a secondary demand, derived substantially from the demand for new or remodeled houses and other buildings.4

Both the U.S. and Canadian softwood lumber industries are largely driven by the U.S. housing market in general and the new construction or remodeling market specifically. In the early to mid-2000s, the U.S. and Canadian softwood lumber industries enjoyed a period of prosperity as the residential real estate market boomed. However, the softwood lumber industry began to struggle when the real estate market began to crash in 2007. For example, from 2005 to 2009 the number of new home construction starts declined by 74%.5 Over that same period, the use of softwood lumber in the United States decreased by 41%.6 Further, the number of sawmills (used to process lumber) decreased by 17%, sawmill capacity decreased by 11%, and sawmill production decreased by nearly 30%.7 Since 2010, the U.S. housing and softwood lumber markets have made a modest recovery. New home construction starts have increased annually.8 U.S. consumption of softwood lumber has increased annually since 2009, although it remains well below the rates of the early 2000s and at levels not seen since the early 1990s.9

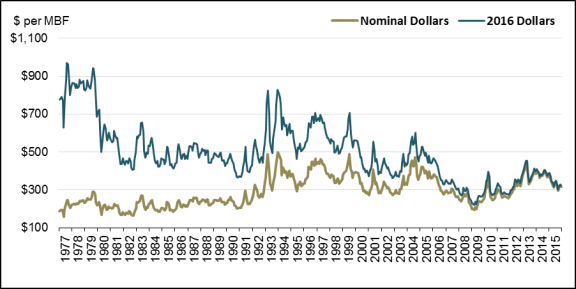

As a secondary demand, softwood lumber is largely price-inelastic. This means that modest changes in construction demand cause relatively large changes in lumber prices, but the price of lumber does not affect the supply or demand of lumber, or, debatably, the price of construction. For example, wood products are generally a minor component of construction costs. While some claim that wood products represent up to 15% of construction costs,10 using the 2014 average framing lumber composite price of $383 per thousand board feet (MBF),11 framing lumber in an average (2,690-square foot) new home would cost $7,512—3% of the 2014 median price of a new home.12 In contrast, the price of lumber dropped significantly as a result of the housing market crash. In 2009, the price of lumber fell below $200 MBF for several months, for the first time since the 1980s (see Figure 1). Since the expiration of the 2006 SLA, lumber prices have risen steadily, and they were above $400 MBF for both March and April 2017. When adjusted for inflation, however, the price of lumber remains relatively low, comparable to the prices of the early 2000s but below prices seen in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s in real terms.

Stakeholders in the U.S.-Canada Softwood Lumber Dispute

In the United States, the major stakeholders in the dispute include timber producers (forest land owners), lumber producers, and lumber consumers (homebuilders and home buyers). Timber producers are included with lumber producers, since many lumber producers also own significant tracts of forest land. In Canada, the major stakeholders include the Canadian lumber producers and the provincial governments, as the timberland owners.13

The U.S. lumber producers support trade restrictions on Canadian imports.14 In contrast, U.S. lumber consumers prefer access to affordable lumber and therefore many generally oppose trade restrictions on Canadian imports. The National Association of Home Builders (NAHB), representing the interests of U.S. lumber consumers, contends that American home buyers are the ones who eventually pay for the cost of the trade restrictions and that unrestricted trade benefits the U.S. economy as a whole.15 Further, they maintain that the restrictions have "reduced the incentive for U.S. producers to adopt new and innovative technology to increase production and improve efficiency of their mills so as to be internationally competitive."16 In response to the expiration of the agreement, NAHB and other partners have formed the American Alliance of Lumber Consumers to advocate for trade on lumber.17 However, under U.S. trade remedy laws,18 U.S. lumber consumers do not have standing in the dispute and may only participate as an interested party.19

|

Figure 1. Average Monthly Composite Prices for Framing Lumber in Current (Nominal) and 2016 Dollars |

|

|

Source: Random Lengths Publications, Inc., at http://www.randomlengths.com/ on April 12, 2017. Notes: Adjusted to 2016 dollars using the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. MBF = thousand board feet. |

U.S. Softwood Lumber Consumption

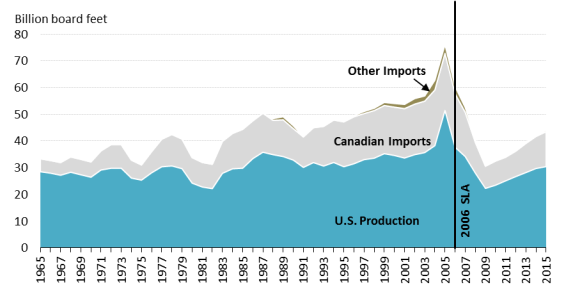

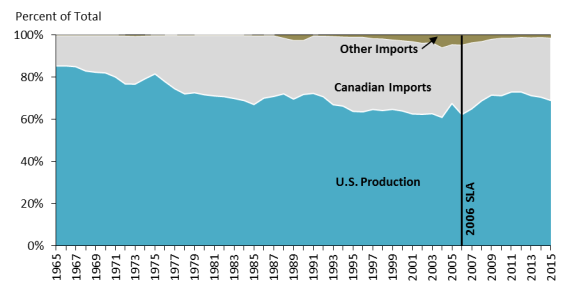

Historically, Canada has been the largest foreign supplier of softwood lumber in the United States, accounting for 95% of imports since 1965 (see Figure 2 and Figure 3).20 In 1965, the United States imported less than 5 billion board feet (BBF) of Canadian lumber, accounting for only 14% of U.S. consumption. However, Canadian imports rose to more than 20 BBF in 2004 and 2005, including an 80% increase from 1990. In comparison, U.S. lumber production for the domestic market (i.e., excluding U.S. lumber exports) during that same period increased by only 56%. The Canadian share of the U.S. market peaked at more than 35% in 1995-1996 and fluctuated around 33% until 2005. Over the nine years the 2006 SLA was in place, the Canadian share of the U.S. market averaged 28% annually.

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS); James L. Howard, U.S. Timber Production, Trade, Consumption, and Price Statistics 1965–2002, Res. Pap. FPL–RP–615 (Madison, WI: USDA Forest Service, December 2003), Table 28, p. 52 and Table 31, p. 55. Data update provided via personal correspondence. Notes: Black line indicates when the 2006 SLA was entered in force. |

|

|

Source: CRS; James L. Howard, U.S. Timber Production, Trade, Consumption, and Price Statistics 1965–2002, Res. Pap. FPL–RP–615 (Madison, WI: USDA Forest Service, December 2003), Table 28, p. 52 and Table 31, p. 55. Data update provided through personal correspondence with USDA. Notes: Black line indicates when the 2006 SLA entered into force. |

Alleged Subsidies to Canadian Lumber Producers

The main basis of the United States-Canada softwood lumber dispute is the allegation that Canadian lumber production is subsidized by the Canadian government. U.S. lumber producers allege that these subsidies give Canadian lumber producers an unfair advantage in the U.S. market, causing injury to U.S. producers.21 The U.S. Lumber Coalition, which represents the U.S. lumber industry, has argued that absent a trade agreement or other trade protection measures, Canadian imports have risen due to government programs in Canada.22 In particular, they assert that the fees set by the provinces for government-owned timber are less than prices in a competitive free market in North America would be. However, comparing the relative competitiveness of U.S. and Canadian lumber producers is challenging. This is due to differences in land ownership and thus timber supply, pricing and allocation systems, and measurement systems, among other factors, as described below.

Different Land Ownership and Management Regimes

The United States and Canada both have vast forest resources, but the ownership patterns, development pressures, and forest management policies in each country are very different. In Canada, about 94% of the timberlands are "crown lands" owned and administered by the federal and provincial governments.23 Overall, the provinces own 90% of the timberlands, the Canadian federal government owns 2%, and 6% is in private ownership, although the provincial ownership percentage varies by province. Most of the federally owned timberlands are northern boreal forests located in the Yukon, Nunavut, and Northwest Territories that do not produce significant amounts of softwood lumber. This contrasts with U.S. timberlands, where 42% are owned by the government (31% federal, 9% state, and 2% local) and 58% are privately owned.24 As a result, the U.S. lumber industry relies more heavily on private timber sources, whereas the Canadian lumber industry relies mostly on public sources of timber.

Each Canadian province has its own forestry laws, regulations, and standards, and Quebec enacted forestry reforms in 2013 in part as an effort to employ the "exit ramp" provisions of the 2006 SLA.25 In general, the provinces require management plans for forested areas, typically prepared by certified professional foresters and subject to participation or review by a broad spectrum of users and interests.26 The provinces also allocate timber harvest. The provinces typically use tenure agreements, or leases, which grant exclusive rights to the specific annual harvest level with various management obligations (e.g., road construction and reforestation).27 The tenure agreements may be long-term (5-25 years) or short-term (as brief as 6 months, with fewer management obligations). Many provinces also have other agreements for selling various types of timber to specific, often quite small or family-operated firms.

|

|

Sources: Map created by CRS using Esri Basemaps. British Columbia Forest Region boundary files were created by Data BC, a pilot project of the British Columbian government, current as of 1/13/2005, at https://apps.gov.bc.ca/pub/geometadata/metadataDetail.do?recordUID=32891&recordSet=ISO19115. Forest cover boundaries provided by the World Wildlife Fund Terrestrial Ecoregions data, current as of 2005. Notes: Province names in dark print were subject to export restrictions in the 2006 SLA; provinces in light print were excluded. |

Different Fee Systems

In large part due to the different land management regimes in the two countries, the United States and Canada each rely on different price allocation systems to determine the cost of lumber. In the United States, prices are established in competitive markets between willing buyers and willing sellers, often through auctions. This is the situation for wood product manufacturers and private timberland owners and, arguably, federal timber sales in areas with competitive bidding.28 Thus, much of the timber from lands in the United States is sold at relatively fair market values. This may not be the case in Canada, where leases (rather than competitive bids) are used to allocate timber.

In Canada, the provinces charge fees for timberland leases and timber harvests. There is generally a flat annual fee for maintaining the leases and a stumpage fee—a per-unit-of-volume fee charged for the right to harvest the trees—for the timber harvested. In many of the provinces, stumpage fees are determined administratively and range from a fixed, province-wide fee to fees established separately for each tenure agreement. These fees are adjusted periodically to reflect changes in the market prices of lumber and other wood products.

As discussed above, while the 2006 SLA was in force, Quebec modified its stumpage pricing systems. In 2013, Quebec passed the Sustainable Forest Development Act,29 which, among other provisions, established that 25% of the annual allowable crown harvest was to be sold at auction starting in 2013. The price received at auction was then factored into the timber agreements covering the remaining 75% of the harvest.

The stumpage fees administered by the Canadian provinces may not match market-determined prices, because the fees are determined by agency personnel who some argue have an incentive to set the fees below market value to assure the competitiveness of their products.30 The U.S. lumber industry asserts that the provinces have intentionally set the fees substantially below market prices, to assure the competitiveness of the Canadian producers.31 Whether provincial administrative stumpage fees approximate market values or are substantially below market values can only be determined by examining provincial fees and U.S. prices for comparable timber, but such comparisons are difficult, as discussed below.

Comparing U.S. and Canadian Stumpage Fees

Allegations that Canadian lumber production is subsidized by the Canadian government rest in part on the claims that Canadian stumpage prices—which are set administratively—are lower than the market-determined stumpage prices in the United States. If this is the case, it would result in a lower cost of production for Canadian firms compared to U.S. firms and might be considered a subsidy from the Canadian government. However, evidence to demonstrate the possible disparity between U.S. and Canadian stumpage fees is widespread, but inconclusive. Some reports have found significantly higher stumpage fees in Canada, while other reports have found the United States to have higher stumpage fees.32 Also, throughout the history of the dispute, the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) and the U.S. International Trade Administration (ITA) have found significant differences in stumpage fees in various examinations dating back to 1982. However, other analyses have shown little or no difference between U.S. and Canadian fees.33

Several factors can explain such apparent contradictions. First, U.S. timber and Canadian timber are measured differently. In the United States, trees and lumber are measured in board feet (linear), as described above. In Canada, trees and lumber are measured in cubic meters (volume). The conversion—how many board feet of lumber can be produced from a cubic meter of logs—depends on the diameter of the log, ranging from about 130 board feet per cubic meter for a 6-inch diameter, 16-foot log to more than 275 board feet per cubic meter for a 44-inch, 16-foot log.34 Thus, the conversion rate chosen (i.e., different assumptions about log diameters) can have a significant effect on the resulting price.

Second, except for the occasional forest plantation, forests are not uniform monocultures—forests may contain several species of trees, each of which varies in diameter, height, and quality. U.S. and Canadian forests differ in their species mix (percentage of trees or timber volume in each species) as well as in the size and quality of the trees of each species. Comparisons typically use a single dominant species (e.g., Douglas fir), but the stumpage fee for the dominant species can be affected by the fee for other species. In U.S. federal timber sales, for example, competitive bidding is generally limited to the dominant species, with the other species being sold at the appraised price; this leads to an overall balance, but limits the validity of the fees for comparing the prices of timber in different areas. Adjusting for these differences is difficult, under the best of circumstances.

Other factors also affect stumpage fees. For example, management responsibilities imposed on timber purchasers differ. In Canada, licensees are generally responsible for reforestation and for some forest protection.35 In U.S. federal forests, timber purchasers generally make deposits to pay for agency reforestation efforts, and some of those deposits are typically reported as part of the stumpage fees. Road construction and road maintenance responsibilities and labor compensation also differ.

History of the Dispute

The dispute between the United States and Canada regarding softwood lumber trade dates back to the 1930s, but the so-called lumber wars began in the 1980s when the United States first considered trade protection measures.36 Table 1 summarizes the major periods of trade dispute and agreement from 1982 to the present.

|

Time Period |

Trade Status |

Summary |

|

1982-1983 |

Trade Dispute: Lumber I |

The U.S. lumber industry, represented by the Coalition for Fair Canadian Lumber Imports (CFLI; now known as the U.S. Lumber Coalition), filed a preliminary countervailing duty petition, arguing that the U.S. lumber industry had been harmed by subsidized Canadian provincial stumpage fees. However, the International Trade Administration (ITA) did not establish a countervailing duty. |

|

1986 |

Trade Dispute: Lumber II |

The U.S. lumber industry filed a new countervailing duty petition. In contrast to 1982, the 1986 preliminary finding established a 15% ad valorem countervailing duty, pending a final determination due by December 31, 1986. A final determination was avoided with the signing of a joint Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the two countries on December 30, 1986. |

|

1986-1991 |

Trade Agreement: MOU |

The 1986 MOU established a 15% tax on Canadian imports until the Canadian provinces raised stumpage fees. The MOU lasted six years. |

|

1992-1995 |

Trade Dispute: Lumber III |

Canada withdrew from the MOU and the United States imposed another countervailing duty (6.51% ad valorem) shortly thereafter. The United States and Canada filed competing claims against each other in U.S. and international courts for trade violations. |

|

1996-2001 |

Trade Agreement: 1996 Softwood Lumber Agreement |

The United States and Canada signed a five-year Softwood Lumber Agreement that established a fee on imports exceeding a specified quota. |

|

2001-2005 |

Trade Dispute: Lumber IV |

Immediately following the expiration of the 1996 agreement, the United States again imposed countervailing and antidumping orders on Canadian lumber imports (Lumber IV). Again, both countries initiated proceedings in international and U.S. courts claiming violations of various trade agreements, including the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements. The lawsuits persisted until the 2006 Softwood Lumber Agreement was entered in force. |

|

2006-2015 |

Trade Agreement: 2006 Softwood Lumber Agreement |

The United States and Canada signed a six-year Softwood Lumber Agreement that established a system of fees and quotas on Canadian imports. In 2012, the agreement was extended through October 12, 2015. The agreement expired on October 12, 2015, and included a one-year grace period that precluded any trade-protection petitions. |

|

2016-current |

Trade Dispute: Lumber V |

After the expiration of the grace period in October 2016, the U.S. lumber industry filed a new countervailing duty petition. Final AD/CVD duties were assessed by the Department of Commerce on November 2, 2017 (see below). |

Source: CRS.

Lumber IV and the 2006 Softwood Lumber Agreement

Between 2001 and 2006, the United States collected approximately $5.3 billion from duties on Canadian lumber (Lumber IV).37 Duty collection and related litigation was terminated with the signing of the SLA in October 2006.38 Under the agreement, the United States returned about $4 billion that was collected from the duties to the importers of record. The remaining deposits were split evenly between the U.S. lumber industry and jointly agreed-upon initiatives. In exchange, the parties agreed to terminate, or in some cases dismiss, all international and domestic court claims filed by Canada, Canadian producers, the United States, and the U.S. industry. The SLA precluded new cases, investigations and petitions, and actions to circumvent the commitments in the agreement and included an agreement by which the participating U.S. producers would not file new petitions or investigations for a period of 12 months after the agreement's termination or expiration. The SLA also established a third-party arbitration system to handle any disputes under the agreement.

The SLA established export charges on softwood lumber originating from specific Canadian provinces when the price of lumber fell below $355 per thousand board feet (MBF),39 with the rate charged varying based on the prevailing composite price.40 The export charges were significantly reduced for Canadian producing regions that also agreed to volume restraints, which become increasingly restrictive as the average price dropped.

The SLA was first set to expire in 2013 but included a one-time option to be renewed for an additional two years. Nearly two years prior to the expiration, on January 23, 2012, the United States and Canada both agreed to the two-year extension. The SLA then expired on October 12, 2015, without any formal negotiations for a new agreement between the counties taking place. The U.S. lumber industry identified perceived flaws in the SLA arbitration process and was in favor of letting the agreement expire. The Canadian government and Canadian lumber producers generally have supported free trade but have been amenable to trade agreements that ensure access to the U.S. market.

Lumber V

As mentioned above, the 2006 SLA expired on October 12, 2015, although a one-year cooling-off period prevented trade litigation from being introduced until after October 12, 2016. On March 10, 2016, President Obama and Prime Minister Trudeau announced the start of discussions to "explore all options" regarding the dispute, charging their trade representatives with reporting back within 100 days.41 The result of this exercise was a set of negotiating goals, which included, among other elements:

- "an appropriate structure, designed to maintain Canadian exports at or below an agreed U.S. market share to be negotiated, with the stability, consistency and flexibility necessary to achieve the confidence of both industries;

- provisions for regional or company exclusions, if justified; and

- provisions promoting regional policies that eliminate the underlying causes of trade frictions, including a regional exits process that is meaningful, effective and timely, recognizing that should an exit be granted, it would be reversible if the circumstances justifying the exit change."42

These goals would effectively limit softwood lumber exports to specified market share, but they left for negotiating the method to achieve this end: through a quota system, an export tax, or a combination of both. The goals also reflect the Canadian desire for flexibility by region and the ability to exit out of market share system based on adoption of market pricing. In subsequent talks, the following concepts were discussed:

- Market restraint mechanism: Canada proposed an export tax on its lumber to achieve a certain market share in the United States. Canada also sought provincial flexibility—quota, export tax, or a combination—to achieve the market access goal. U.S. producers have criticized an export tax as not guaranteeing a certain market share; they claim such a tax would only penalize Canadian producers for exporting above target. As such, U.S. producers are in favor of a quota-only system.

- Market Access: The Canadian proposal reportedly is based on a 32% market share. The U.S. producers reportedly sought a 28% share gradually lowered to 22% during the term of an agreement.

- Regional flexibility: Canada also sought continued exclusions for largely private-held timber from the maritime provinces. They also favored a province's ability to exit the market access restraints if it adopts market based systems, as Quebec claims it has done. The previous SLA contained such a provision, which Canada criticized as ineffectual.

These discussions did not make headway during the last months of the Obama Administration. In the Trump Administration, Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross and Canadian Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland undertook negotiations to solve the dispute in the summer and fall of 2017, and Secretary Ross announced the postponement of the final AD/CVD determinations to facilitate an extension of the talks. However, Commerce announced on November 2, 2017, that the two parties were unable to reach an agreement and announced the final determinations (see below).43

Litigation

U.S. Trade Remedy Action

The Committee Overseeing Action for Lumber International Trade Investigations or Negotiations (COALITION) petitioned the International Trade Administration (ITA) of the Department of Commerce and the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) to initiate antidumping (AD) and countervailing duty (CVD) proceedings against Canadian softwood lumber on November 25, 2016 (see Table 2). Under AD and CVD procedures, ITA must first determine whether the petition has merit and whether further investigation is warranted. ITA decided in the affirmative on December 15, 2016. ITC then determines whether there is a reasonable indication of injury. ITC made a positive determination on January 9, 2017. If ITC had found no reasonable indication of injury, the proceedings would have ended.44

In the next phase, ITA investigated the existence and extent of the unfair trade practice and made preliminary estimates of the dumping or subsidy margins. On April 24, 2017, ITA determined the existence of a subsidy of between 3.02% and 24.12% on five major companies and an "all other" rate of 19.88%. As a result of this decision, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), in turn, suspended liquidation (i.e., delayed the computation of duties until the proceedings are finished) and required importers to post cash deposits or bonds to cover the potential duties resulting from the estimated subsidy margin. ITA also found "critical circumstances" for some companies, meaning that retroactive duties from 90 days prior to the preliminary determination will be imposed on them.

The ITA made its preliminary dumping determination on June 26, 2017. Preliminary dumping margins were assessed at 4.59%-7.72%, depending on the company, with an all-other rate of 6.87%, and CBP suspended liquidation to account for these duties. ITA found critical circumstances for companies subject to the all-other rate, thus retroactive dumping duties will be applied from 90 days prior to the preliminary determination. It also exempted lumber products made from logs originating in the maritime provinces of Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island, as they are primarily harvested from private lands.45

ITA made its final AD/CVD determinations on November 2, 2017.46 Dumping margins were assessed for four specific firms at 3.20% to 8.89%, with an all-other firm rate of 6.58%. In the AD cases, Commerce found critical circumstances for three of the four firms, as well as the all-other category, triggering the aforementioned retroactive duties. The final subsidy determinations were assessed at 3.34%-18.19%, depending on the firm, with a 14.25% all-other rate. Unlike the AD cases, Commerce did not find critical circumstances in the subsidy cases. As with the preliminary determinations, Commerce exempted products from the 3 maritime provinces.

On December 7, 2017, ITC determined that practices found by ITA caused "material injury," to the U.S. lumber industry.47 Thus, Commerce is expected to issue AD and CVD orders equivalent to the calculated subsidy or dumping margin.

Trade Agreement Dispute Settlement

As expected, Canada has challenged the U.S. trade remedy actions at WTO and NAFTA dispute settlement. A challenge at the WTO is brought to determine whether a trade action is compatible with its agreements, in this case the Antidumping Agreement and the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing measures. A NAFTA Chapter 19 action is brought to assess whether a country's investigating authorities (ITA, ITC) are following its own laws.

NAFTA

On November 14, 2017, Canada requested the establishment of a panel to review the final CVD duties imposed by ITA (see above). Subsequently, Canada also requested the establishment of a dispute settlement (DS) panel to review to final AD duties on December 5.48 Under NAFTA Chapter 19, a party can seek a binational review panel to assess whether a party's investigating authority's decision is consistent with its trade remedy laws. Panelists are appointed from a roster of experts in each NAFTA party and panels are designed to reach a final decision within 315 days after initiation.

WTO

Canada took the first step to bringing a WTO case on the U.S. actions by requesting consultations with the United States on the softwood lumber duties on November 28, 2017.49 In its request, Canada maintains that Commerce impermissibly used certain methodologies in calculating the dumping duties, and also used the practice of zeroing,50 which the WTO has ruled impermissible. It also requested consultation on CVD duties, which it claims improperly described its timber programs as subsidies. After the mandated 60-day consultation period, the United States blocked Canada's first request for the establishment of DS panels on March 27, 2018. Canada's second request for a panel—which cannot be blocked under DS body rules—was granted by the DS body meeting on April 9, 2018.

|

Antidumping Investigation |

Countervailing Duty Investigation |

|

|

Petitions Filed |

November 25, 2016 |

November 25, 2016 |

|

ITA Initiation Date |

December 15, 2016 |

December 15, 2016 |

|

ITC Preliminary Determinations |

January 9, 2017 |

January 9, 2017 |

|

ITA Preliminary Determinations |

June 26, 2017 |

April 24, 2017 |

|

ITA Final Determinations |

November 2, 2017 |

November 2, 2017 |

|

ITC Final Determinations |

December 7, 2017 |

December 7, 2017 |

|

Issuance of Orders |

December 22 (expected) |

December 22, (expected) |

Source: CRS.

Notes: Dates subject to change. ITA = International Trade Administration; ITC = U.S. International Trade Commission.

Issues for Congress

While the softwood lumber litigation plays out, Congress may seek to influence any settlement of the softwood lumber dispute through potential renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).51 During the campaign and in office, President Trump has vowed to renegotiate or withdraw from NAFTA. However, under Trade Promotion Authority (TPA),52 the President must give advanced notice to Congress for any renegotiation and must consult with Congress before and during the negotiations. This process affords Congress the opportunity to influence and direct the course of negotiations.

In this fashion, Congress may seek to examine several issues relating to a potential future agreement. For example, Members may seek to shape an agreement within the context of NAFTA itself. Congress may seek the removal of export log restrictions as part of any NAFTA package. Some Members of Congress favor the removal of the NAFTA Chapter 19 dispute settlement arbitration panels, which Canada has used to challenge the decisions of U.S. trade remedy enforcement agencies, including in the softwood lumber cases. Congress also may consider the extent to which U.S. home builders and home buyers are affected by the possibility of renewed antidumping and countervailing duties being placed on softwood lumber.

Summary and Conclusion

The end of the 2006 SLA and the commencement of trade remedy litigation is a recurring pattern in the decades-long softwood lumber dispute. The determination of injury from subsidy and dumping likely will be followed, as it has in the past, by Canadian appeals to the World Trade Organization and NAFTA dispute settlement. Then, the parameters of a new export restraint agreement may be explored.

U.S. lumber producers assert that they have been injured by Canadian subsidies that have given Canadian lumber producers an unfair advantage in selling lumber in the U.S. market. These two conditions—subsidies and injury—are prerequisites for a countervailing duty under U.S. trade law. One alleged subsidy is Canadian provincial stumpage fees (fees for the right to harvest trees), which may be less than the value of the timber in a competitive market. In the 10 Canadian provinces, 90% of the timberland is owned by the provinces. The majority of provincial timber is allocated to lumber producers under long-term area-tenure agreements, which specify harvest levels, management requirements, and stumpage fees. The stumpage fees generally are set administratively and adjusted periodically to reflect changes in lumber markets. This situation contrasts with that in the United States, where most timberlands are privately owned and timber from federal and state lands typically is offered for sale at competitive auctions. Administered fees are not likely to match market values but could be higher or lower, depending on the purpose and methods by which they are established; critics have claimed that the Canadian administrative fees are set low to assure profitable production, regardless of market conditions. Several studies have shown significantly lower Canadian stumpage fees, but other studies have found comparable cross-border prices. These contradictory results may be explained by the adjustments made to account for differences in timber measurement systems (one cubic meter of Canadian logs yields 125–275 board feet of U.S. lumber, depending on the logs' diameters); in tree species, sizes, and grades; and in requirements imposed on the timber purchaser (e.g., reforestation and road construction), among other factors. Analyses of the differences are difficult and generally problematic.

Injury to the U.S. lumber industry remains a complex issue. The Canadian share of the U.S. softwood lumber market grew substantially over the past 60 years, from less than 7% in 1952 to more than 35% in 1996. During that period, U.S. lumber production for domestic consumption grew slowly (from nearly 30 billion board feet [BBF] in the early 1950s to 35 BBF in 1999), while imports of Canadian lumber rose substantially (from less than 3 BBF in the early 1950s to more than 18 BBF in 1999). Under the 1996 agreement, imports remained at a relatively stable rate, fluctuating around 33%-34%. Under the 2006 SLA, Canadian imports declined to around 28%. This decline is likely attributable—at least in part—to the SLA and a drastically decreased demand for softwood lumber due to the crisis in the U.S. housing market.

Other factors might also be important in the dispute over lumber imports from Canada. Some believe the persistence of the dispute is due, at least in part, to the conflict between a U.S. trade policy focused on the removal of trade barriers and the process for obtaining industry protection under U.S. trade law. Others contend that the dispute is fueled by interest-group politics, and that the U.S. lumber industry is better organized and more influential than U.S. lumber consumers, who mostly feel the cost impacts of the trade protection measures.53 In addition, environmental laws and policies may differ, and the impact of those laws and policies for lumber production costs complicates any cross-border analyses. Finally, the dispute may be alleviated in part due to increasing cross-border firm integration.54 In other words, lumber producers may increasingly become globalized, with holdings in both the United States and Canada, and as such may begin to question these border protection measures.

Appendix. What Is Softwood Lumber?

The definition of "softwood lumber" subject to the SLA had been an issue leading up to the signing of the 2006 agreement.55

Softwood is a classification of tree species and contrasts with the other major classification, hardwood. Both, however, are misnomers. Some hardwoods, "such as aspen and poplar, are softer (less dense) than many softwoods," such as yellow pines.56 Softwood species are all in the order Coniferales—the conifers. Conifers generally have needle-like leaves and cones for reproduction. These plants are often called evergreens, because most retain their needles in winter.57 The hardwood timber species are in the phylum Anthophyta—the angiosperms, or flowering plants. These plants are often called deciduous, because most species in temperate climates lose their leaves in the winter; however, some temperate-climate species (e.g., holly) and most tropical and subtropical species are evergreen, retaining their leaves throughout the year. Despite the imprecision, softwood is the term of art for conifer species and is used in this report to indicate lumber produced from conifer species. This use is also consistent with the definition of softwood lumber in the harmonized tariff schedules and in the 2006 SLA. (See below.)

Lumber is the collective term for products sawn from logs. This contrasts with the panel products—plywood, particleboard, etc.—where the logs are sliced, peeled, or chipped and the wood pieces are then glued together to form sheets or panels.58 It also contrasts with paper products, where wood chips are dissolved to remove the lignin and the fibers adhere by being pressed together under heat. Lumber is grouped into different categories based on cross-sectional dimensions. Boards are lumber products of less than 2 inches in nominal thickness—typically 1 inch thick and 1 inch to 12 inches wide (in 2-inch increments).59 Dimension lumber are products of 2 inches to 5 inches in nominal thickness—most commonly 2 inches thick and 2 inches to 12 inches wide (in 2-inch increments) in nominal dimensions. Timbers are lumber products at least 5 inches thick and wide, and timbers include products destined for further processing. The vast majority of softwood lumber—nearly 75%—is used for residential construction, remodeling, and repair.60

For purposes of the dispute, softwood lumber is defined in Annex 1A of the SLA using four tariff items under the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (HTSUS):61

Softwood lumber products include all products classified under tariff items 4407.1000, 4409.1010, 4409.1020, and 4409.1090 (for purposes of description only):

coniferous wood sawn or chipped lengthwise, sliced or peeled, whether or not planed, sanded or finger-jointed, of a thickness exceeding 6 mm [about 1/4 inch];

coniferous wood, coniferous wood siding and coniferous wood flooring (including strips and friezes for parquet flooring, not assembled) continuously shaped (tongued, grooved, rebated, chamfered, V-jointed, beaded, moulded, rounded or the like) along any of its edges or faces (other than wood mouldings and wood dowel rods), whether or not planed, sanded or finger-jointed ...62

These tariff items include essentially all the traditional softwood lumber items intended for residential construction, as described above, including softwood drilled and notched lumber and angle-cut lumber and excluding logs, poles, wood fencing, and railway sleepers (cross-ties). The definitions also allow for products that are classified under certain other HTSUS subheadings but meet the SLA's definition of softwood lumber products. This definition also excludes certain products, including windows and doors (with frames), garage doors, box springs, pallets, roof trusses, and other fabricated wood products.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

This report was informed by previous reports written by Ross Gorte, retired CRS specialist in Natural Resources Policy.

Footnotes

| 1. |

For a complete background of the dispute up to the 2006 Softwood Lumber Agreement (SLA), see CRS Report RL33752, Softwood Lumber Imports from Canada: Issues and Events, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]; and CRS Report RL30826, Softwood Lumber Imports From Canada: History and Analysis of the Dispute, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 2. |

For more information on the 2006 SLA, see CRS Report R44851, The 2006 U.S.-Canada Softwood Lumber Trade Agreement (SLA): In Brief, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 3. |

The SLA definitions also includes some products that are classified under certain other Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (HTSUS) subheadings, but also excludes certain products, including windows and doors (with frames), garage doors, box springs, pallets, roof trusses, and other fabricated wood products. |

| 4. |

Henry Spelter, David McKeever, and Daniel Toth, Profile 2009: Softwood Sawmills in the United States and Canada, US Forest Service, FPL-RP-659, Madison, WI, 2009, https://www.treesearch.fs.fed.us/pubs/34525. (Hereinafter referred to as Spelter et al., Profile 2009.) |

| 5. |

See New Residential Construction data statistics published by the U.S. Census Bureau, http://www.census.gov/construction/nrc/index.html. |

| 6. |

James L. Howard, U.S. Timber Production, Trade, Consumption, and Price Statistics 1965– 2002, Res. Pap. FPL–RP–615 (Madison, WI: USDA Forest Service, December 2003), Table 28, p. 52 and Table 31, p. 55. Data update provided via personal correspondence, April 2017. (Hereinafter referred to as Howard, U.S. Timber Statistics.) |

| 7. |

Spelter et al., Profile 2009. Production is calculated from 2005 to 2008, because 2009 numbers were not published. |

| 8. |

See New Residential Construction data statistics published by the U.S. Census Bureau, http://www.census.gov/construction/nrc/index.html. |

| 9. |

Howard, U.S. Timber Statistics. |

| 10. |

The National Association of Home Builders estimates that wood products represent 15% of the construction cost of an average home. However, there are some concerns about the methodology used to arrive at this estimate. Specifically, the results rely on a small number of self-reported responses (2% response rate, with 44 responses from N=2,185) and it is unclear if the estimate also includes the cost of labor. Heather Taylor, New Construction Cost Breakdown, National Association of Home Builders, November 1, 2011. |

| 11. |

This is a weighted average of U.S. and framing lumber prices calculated weekly by Random Lengths, Inc., a wood products price reporting firm located in Eugene, OR. See http://www.randomlengths.com. |

| 12. |

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2014 the average size of a new single family home was 2,690 square feet, and the median sales price of a new single family homes was $282,800 (http://www.census.gov/construction/chars/sold.html). |

| 13. |

Daowei Zhang, The Softwood Lumber War: Politics, Economics, and the Long U.S.-Canadian Trade Dispute (Washington, DC: Resources for the Future, 2007). (Hereinafter cited as Zhang, The Softwood Lumber War, 2006.) |

| 14. |

See for example, U.S. Lumber Coalition, "U.S. Lumber Industry Applauds Commerce Department Finding of Massive Canadian Subsidies," press release, April 24, 2017, at https://uslumbercoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/USLC-Press-Release-Re-Lumber-V-CVD-Prelim-FINAL-04.24.2017.pdf. |

| 15. |

National Association of Home Builders, "Statement from NAHB Chairman Granger MacDonald on Comments by Commerce Secretary Ross Regarding Canadian Lumber Tariffs," press release, April 25, 2017, at http://www.nahb.org/en/news-and-publications/press-releases/2017/04/statement-from-nahb-chairman-on-comments-by-commerce-secretary-regarding-canadian-lumber.aspx. See also James W. Tobin III, Comments submitted to the U.S. Department of Commerce on behalf of the National Association of Home Buildings Regarding Subsidy Programs Provided by Countries Exporting Softwood Lumber and Softwood Lumber Products to the United States, National Association of Home Builders, May 29, 2014. |

| 16. |

Gerald Howard, Comments Submitted to the Office of the United States Trade Representative on Behalf of the National Association of Home Builders Regarding the Two-Year Extension of Softwood Lumber Agreement, National Association of Home Builders, October 14, 2011. |

| 17. |

Other members of the coalition include the National Retail Federation and the National Lumber and Building Material Dealers Association. National Association of Home Builders (NAHB), NAHB Forms Coalition Dedicated to Free Lumber Trade, March 30, 2016, at http://nahbnow.com/2016/03/nahb-forms-coalition-dedicated-to-free-lumber-trade/. |

| 18. |

For more information on U.S. trade remedies, see CRS Report RL32371, Trade Remedies: A Primer, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 19. |

19 U.S.C. §1677 (9). |

| 20. |

Howard, U.S. Timber Statistics. |

| 21. |

Zhang, The Softwood Lumber War, 2006. |

| 22. |

U.S. Lumber Coalition Comments to the USTR. |

| 23. |

Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, The State of Canada's Forests: 2016 (Ottawa, ON, Canada: 2011), at http://www.nrcan.gc.ca/forests/canada/ownership/17495. |

| 24. |

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, "Table B-2–Forest Land Area in the United States by Ownership. Region, and Subregion, and State, 2012," Forest Resources of the United States, 2012, GTR WO-91. at http://www.treesearch.fs.fed.us/pubs/47322. |

| 25. |

For more information, see CRS Report R44851, The 2006 U.S.-Canada Softwood Lumber Trade Agreement (SLA): In Brief, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 26. |

Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, Sustainable Forest Management: A Continued Commitment in Canada, Monograph No. 9 (Ottawa, ON, Canada: 2000). |

| 27. |

David Haley and Martin K. Luckert, Forest Tenures in Canada: A Framework for Policy Analysis, Information Report E-X-43 (Ottawa, ON, Canada: Forestry Canada, 1990). (Hereinafter cited as Haley and Luckert, Forest Tenures in Canada.) |

| 28. |

Some may argue that the U.S. government is not comparable to a traditional private "willing seller," since the U.S. government does not make investments or sales based on profitability, as a private landowner presumably would. However, since the U.S. federal government only owns 33% of U.S. timberlands, it likely has a significant but less substantial impact on timber markets than do the Canadian provinces. However, this may vary in terms of the regional impact of federal land ownership and regional lumber markets. |

| 29. |

Sustainable Forest Management Act, CQLR c A-18.1, http://canlii.ca/t/ks3n. |

| 30. |

See Andrew Kentz, David A. Yocis, and Jordan C. Kahn, Comments Submitted to the Office of the United States Trade Representative on Behalf of the U.S. Lumber Coalition, U.S. Lumber Coalition, November 26, 2014; and John A. Ragosta, Harry L. Clark, Carloandrea Meacci, and Gregory I. Hume, Canadian Governments Should End Lumber Subsidies and Adopt Competitive Timber Systems: Comments Submitted to the Office of the United States Trade Representative on Behalf of the Coalition for Fair Lumber Imports, unpublished report (Washington, DC: Dewey Ballantine LLP, April 14, 2000), Appendix 1. |

| 31. |

Ibid. |

| 32. |

See Henry Spelter, "If America Had Canada's Stumpage System," Forest Science, vol. 52, no. 4 (2006); Coopers & Lybrand, Certain Forest Products From Canada, Before the United States Department of Commerce International Trade Administration: Valuation of Stumpage Subsidy, unpublished report (Washington, DC: October 1982), 18 p; and Dewey Ballantine Comments for the CFLI to the USTR. |

| 33. |

See Zhang, The Softwood Lumber War, 2006; The Council of Forest Industries of B.C., A Brief Examination of Comparative Factors Affecting the Forest Industries of the U.S. Pacific Northwest and British Columbia, unpublished report (Vancouver, BC, Canada: October 1981), Brink Lindsay, Mark A. Groombridge, and Prakash Loungani, Nailing the Homeowner: The Economic Impact of Trade Protection of the Softwood Lumber Industry (Washington, DC: Cato Institute, 2000), 15 pp. (Hereinafter referred to as Cato Institute, Nailing the Homeowner.) |

| 34. |

David A. Hartman, William A. Atkinson, Ben S. Bryant, and Richard O. Woodfin, Jr., Conversion Factors for the Pacific Northwest Forest Industry (Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Institute of Forest Products, n.d.), p. 11; with conversion of cubic feet to cubic meters (at 35 cubic feet per cubic meter) by CRS. |

| 35. |

Haley and Luckert, Forest Tenures in Canada. |

| 36. |

For a complete background of the dispute up to the 2006 Softwood Lumber Agreement, see CRS Report RL33752, Softwood Lumber Imports from Canada: Issues and Events, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed], and CRS Report RL30826, Softwood Lumber Imports From Canada: History and Analysis of the Dispute, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 37. |

For more information, see CRS Report RL33752, Softwood Lumber Imports from Canada: Issues and Events, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 38. |

For more information on the 2006 SLA, see CRS Report R44851, The 2006 U.S.-Canada Softwood Lumber Trade Agreement (SLA): In Brief, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 39. |

The SLA applied export measures to lumber products from timber harvested in the provinces of Alberta, British Columbia Coastal, British Columbia Interior, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and Saskatchewan. This figure, $355 MBF, was the average monthly composite price for lumber between May 2002 and April 2006, as calculated by Random Lengths, Inc. See http://www.randomlengths.com. |

| 40. |

As established in the SLA, the Canadian government calculated the prevailing monthly price to determine if export measures were to apply for any given month. The prevailing monthly price was calculated as the most recent 4-week average of the weekly framing lumber composite price, available 21 days before the beginning of the month that the prevailing monthly price was to be applied. |

| 41. |

White House, "Fact Sheet: US-Canada Relationship," press release, March 10, 2016. |

| 42. |

White House Press Release, Joint Statement by the Prime Minister of Canada and the President of the United States on Softwood Lumber. |

| 43. |

Department of Commerce Press Release, November 2, 2017, https://www.commerce.gov/news/press-releases/2017/11/us-department-commerce-finds-dumping-and-subsidization-imports-softwood. |

| 44. |

For more information on the trade remedy process, see CRS Report RL32371, Trade Remedies: A Primer, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 45. |

Fact Sheet: Commerce Preliminarily Finds Dumping of Imports of Softwood Lumber from Canada, http://enforcement.trade.gov/download/factsheets/factsheet-canada-softwood-lumber-ad-prelim-062617.pdf. |

| 46. |

Fact Sheet: Commerce Finds Dumping and Subsidization of Imports of Softwood Lumber from Canada, https://www.commerce.gov/sites/commerce.gov/files/softwood_lumber_canada_ad_cvd_final_fact_sheet.pdf. |

| 47. |

U.S. ITC Press Release, December 7, 2017, https://www.usitc.gov/press_room/news_release/2017/er1207ll879.htm. |

| 48. |

See https://www.nafta-sec-alena.org/Home/Dispute-Settlement/Status-Report-of-Panel-Proceedings. |

| 49. |

DS553 United States- Countervailing Measures on Softwood Lumber from Canada, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds533_e.htm; DS534 United States- Anti-Dumping Merasures Applying Differential Pricing Methodology to Softwood Lumber from Canada, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds534_e.htm. |

| 50. |

Zeroing compares the price of the product a firm charges in a foreign market with the price of the product on the domestic market, but disregards—sets at zero—all transactions in which the price of the product the firm charges on the domestic market is smaller than the price on the foreign market. This practice tends to increase the calculation of the dumping margin. |

| 51. |

For more information on NAFTA, see CRS Report R42965, The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed], and CRS In Focus IF10047, North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 52. |

Bipartisan Comprehensive Trade Promotion and Accountability Authority (P.L. 114-26). For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10038, Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 53. |

Zhang, The Softwood Lumber War, 2006. |

| 54. |

Ibid. |

| 55. |

The definition of which softwood lumber products would be subject to the quota had been at issue in the years leading up to the 2006 SLA. In previous agreements, only standard construction lumber was included in the quota calculations and specialty products (such as builders' joinery) were outside of the quota. Drilled studs were originally classified as builders' joinery, but were reclassified by the U.S. Customs Service in the late 1990s as softwood lumber subject to quota limitations in the agreement, along with various other items previously classified as builders' joinery. The issue, essentially, was whether various products were specialty products with particular construction applications or standard construction lumber with minor modifications to avoid the quota. The items continue to be classified under tariff item 4407 and are subject to the quota limitations in the 2006 SLA. |

| 56. |

The major softwood species—the pines, firs, and spruces—are generally softer (less dense) than the major hardwood tree species of temperate climates—the oaks and maples. |

| 57. |

Trees of the larch genus (Larix spp.) are deciduous, with bare limbs in winter. |

| 58. |

A process similar to plywood production can be used to produce lumber-sized products. Known as parallel-laminated veneer (PLV) lumber, the product is made of wood layers glued together in parallel (in contrast to the perpendicular layers in plywood) and then sawn to traditional lumber sizes. The process has been used for producing large wooden beams (timbers) for many years, but is uncommon for traditional lumber products because the production costs are higher than for traditional products. |

| 59. |

Lumber is identified in nominal sizes, rather than actual dimensions. The nominal sizes were the original dimensions of green, rough-sawn lumber; the actual dimensions are the minimum sizes for dry, finished lumber as specified by the American Lumber Standards Committee, a committee of lumber producers, distributors, and users who have developed voluntary product standards and methods for grading, testing, and marking lumber products, under the aegis of the National Institute of Standards and Technology. See 71 Federal Register 61399 (October 16, 2006) for the softwood lumber agreement. |

| 60. |

Henry Spelter, David McKeever, and Daniel Toth, Profile 2009: Softwood Sawmills in the United States and Canada, USDA Forest Service, Research Paper FPL-RP-659, October 2009, http://www.fpl.fs.fed.us/documnts/fplrp/fpl_rp659.pdf. (Hereinafter referred to as Spelter et al., Profile 2009.) |

| 61. |

"Annex IA Softwood Lumber Products," Softwood Lumber Agreement Between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of Canada (Washington, DC: October 12 2006) at https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/factsheets/Trade%20Topics/enforcement/softwood%20lumber/2006%20U.S.-Canada%20Softwood%20Lumber%20Agreement.pdf. |

| 62. |

Ibid. |