The District of Columbia Tuition Assistance Grant (DCTAG) Program

To address concerns about the public postsecondary education offerings available to District of Columbia residents, the District of Columbia College Access Act of 1999 (P.L. 106-98) established the District of Columbia Tuition Assistance Grant (DCTAG) program. The program is meant to provide college-bound DC residents with a greater array of choices among institutions of higher education by providing grants for undergraduate education. Grants for study at public institutions of higher education (IHEs) nationwide offset the difference between in-state and out-of-state tuition and fees, up to $10,000 per year and a cumulative maximum of $50,000. Students may also receive grants of up to $2,500 per year and a cumulative maximum of $12,500 for undergraduate study at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) nationwide and private, nonprofit IHEs in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area.

DCTAG program grants are provided regardless of need or merit. However, to be eligible to receive a program grant, individuals must, among other criteria, be District of Columbia residents; be enrolled or accepted for enrollment on at least a half-time basis in a degree, certificate, or credential granting postsecondary education program; maintain satisfactory progress in their course of study; be 26 years of age or younger; have a family income under the applicable limit; and have received a secondary school diploma or its equivalent. Post-baccalaureate students who have already earned a bachelor’s degree are ineligible to participate.

Through academic year 2017-2018, a total of 28,998 students have received approximately $505.8 million in DCTAG awards and have attended over 500 IHEs in 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. While there has been a substantial increase in the amount annually appropriated for the DCTAG program and the maximum award size for students attending public two-year institutions since the program’s inception, there has been no change to the maximum award size for students attending other types of institutions. In light of the trend of rising postsecondary education costs, many program participants may be left paying more per year for their education than in previous years or possibly limiting their choices of which institution to attend.

This report first discusses the history of the DCTAG program and the events and legislation leading up to its enactment. It then describes the program’s administration, including recipient eligibility and the amount of award available based on the type of institution attended, award interaction with federal student aid, and funding. Next, the report presents DCTAG performance data, such as the types of institutions DCTAG recipients primarily attend and the types of students served by the program (e.g., the number of grants received, by DC ward). Finally, the report provides an analysis of grant benefits and discusses the extent to which DCTAG awards may be bridging the gap between in-state and out-of-state tuition.

The District of Columbia Tuition Assistance Grant (DCTAG) Program

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Background

- Legislation

- Program Structure

- Eligibility

- Institution

- Student

- Application

- Payments

- Interaction with Federal Student Aid

- Administration

- Appropriations

- Performance

- Students Served

- Awards Versus High School Enrollment

- Grants by Ward

- Graduation Rates

- Analysis of Grant Benefits

- Public Institutions of Higher Education

- Private Nonprofit Schools and Private HBCUs

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Maximum Annual and Lifetime DCTAG Awards at Eligible Institutions

- Table 2. Appropriations for the DCTAG Program

- Table 3. Five-Year Median Family Income and DCTAG Awards, by Ward

- Table 4. DCTAG Enrollment and Number of $10,000 Awards, by Academic Year

- Table 5. DCTAG Participants Enrolled in and Median Full-Time Enrollment Undergraduate Tuition and Fees at District of Columbia Private, Nonprofit Title IV-Eligible Four-Year IHEs

- Table 6. DCTAG Participants Enrolled in and Median Full-Time Enrollment Undergraduate Tuition and Fees at Private Nonprofit Title IV-Eligible HBCUs

Summary

To address concerns about the public postsecondary education offerings available to District of Columbia residents, the District of Columbia College Access Act of 1999 (P.L. 106-98) established the District of Columbia Tuition Assistance Grant (DCTAG) program. The program is meant to provide college-bound DC residents with a greater array of choices among institutions of higher education by providing grants for undergraduate education. Grants for study at public institutions of higher education (IHEs) nationwide offset the difference between in-state and out-of-state tuition and fees, up to $10,000 per year and a cumulative maximum of $50,000. Students may also receive grants of up to $2,500 per year and a cumulative maximum of $12,500 for undergraduate study at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) nationwide and private, nonprofit IHEs in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area.

DCTAG program grants are provided regardless of need or merit. However, to be eligible to receive a program grant, individuals must, among other criteria, be District of Columbia residents; be enrolled or accepted for enrollment on at least a half-time basis in a degree, certificate, or credential granting postsecondary education program; maintain satisfactory progress in their course of study; be 26 years of age or younger; have a family income under the applicable limit; and have received a secondary school diploma or its equivalent. Post-baccalaureate students who have already earned a bachelor's degree are ineligible to participate.

Through academic year 2017-2018, a total of 28,998 students have received approximately $505.8 million in DCTAG awards and have attended over 500 IHEs in 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. While there has been a substantial increase in the amount annually appropriated for the DCTAG program and the maximum award size for students attending public two-year institutions since the program's inception, there has been no change to the maximum award size for students attending other types of institutions. In light of the trend of rising postsecondary education costs, many program participants may be left paying more per year for their education than in previous years or possibly limiting their choices of which institution to attend.

This report first discusses the history of the DCTAG program and the events and legislation leading up to its enactment. It then describes the program's administration, including recipient eligibility and the amount of award available based on the type of institution attended, award interaction with federal student aid, and funding. Next, the report presents DCTAG performance data, such as the types of institutions DCTAG recipients primarily attend and the types of students served by the program (e.g., the number of grants received, by DC ward). Finally, the report provides an analysis of grant benefits and discusses the extent to which DCTAG awards may be bridging the gap between in-state and out-of-state tuition.

Background

The District of Columbia Tuition Assistance Grant (DCTAG) program was created in 1999 to address concerns about the public postsecondary education offerings available to District of Columbia residents. In the 1990s, the University of the District of Columbia (UDC), which, at the time, was the only public institution of higher education (IHE) in Washington, DC, faced a series of obstacles that threatened its existence. In the midst of financial shortfalls across the District's government, the school's budget was severely reduced, from $76 million in FY1992 to $43 million in FY1995. In 1996, when UDC's budget was reduced by an additional $16.2 million, fall enrollment dropped from 10,000 students the previous year to 7,600 students.1 The next fall, acting UDC President Julius E. Nimmons, Jr. laid off 125 faculty members, nearly one-third of the institution's full-time faculty, as well as 200 of the university's 437 non-faculty employees.2 The school's accreditation, though thrown into doubt, was renewed in 1997. Despite reforms put into place after the reaccreditation, UDC remained under public scrutiny for several years.

As a possible indicator that the public higher education available in Washington, DC, did not meet their needs, District residents enrolled in postsecondary institutions outside of their home jurisdiction at a rate far higher than their peers elsewhere in the United States. In the fall of 1998, 3,116 District residents were enrolled as undergraduate freshmen in IHEs, of whom 1,163 (37%) attended public or private institutions in DC. The national average for postsecondary attendance within an individual's jurisdiction3 of residence that year was 82%. The in-state attendance rates of all 50 states were higher than that of the District, with Alaska's the next lowest at 50%.4

This disparity in college-attendance trends across states raised concerns about the cost for District students attending IHEs. In each of the 50 states, some form of public higher education is made available to in-state students at a lower cost than the price of tuition and fees offered to students from outside the state, thereby reducing the average total postsecondary education cost for residents of that jurisdiction. In academic year (AY) 1999–2000, "dependent undergraduates from the District of Columbia paid [an average of] $7,890 per year in tuition minus all grant aid … more than twice the national average" of $3,215 per student annually.5

Although similar issues arising elsewhere in the United States might be rectified through the reallocation of resources among public IHEs and the development of policies at the state level, supporters of the program argued that both the District of Columbia's unique role and status as the nation's capital and the state of local governance required remedies of this sort to be achieved through federal action. In general, budgetary authority for Washington, DC, rests in the hands of Congress, as:

The Constitution gives Congress the power to "exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever" pertaining to the District of Columbia. In 1973, Congress granted the city limited home rule authority and empowered citizens of the District to elect a mayor and city council. However, Congress retained the authority to review and approve all District laws, including the District's annual budget.6

While Congress retains the power to determine the appropriation and allocation of funds, it typically cedes much of the daily governance to local government. However, in the 1990s, troubled city services, a poor credit rating that hindered the District's ability to borrow funds, and an FY1995 budget deficit of $722 million led to federal intervention. Two pieces of legislation, the District of Columbia Financial Responsibility and Management Assistance Act of 1995 (P.L. 104-8) and the National Capital Revitalization Act of 1997 (P.L. 105-33), increased the federal role in the governance of the District of Columbia. New oversight committees were formed and many of the "state functions" normally carried out by the District of Columbia's government were temporarily transferred to Congress.7

As Congress attempted to rejuvenate the District of Columbia's local government and improve the standard of living for the average citizen,8 an increasing number of concerns were raised about the postsecondary education opportunities available to District residents. In March 1999, Washington, DC's Delegate to Congress Eleanor Holmes Norton and Representatives Tom Davis and Constance Morella introduced a bill that would create a program to provide support for higher education to DC residents.

Legislation

On November 12, 1999, the District of Columbia College Access Act (P.L. 106-98) was signed into law, authorizing the DCTAG program for FY2000 to FY2005.9 Congress defined the program's purpose as "enabl[ing] college-bound residents of the District of Columbia to have greater choices among institutions of higher education."10

The DCTAG program provides grants to District residents, regardless of need or merit, to attend eligible public and private, nonprofit IHEs in the United States. When the program was first enacted, annual grants of up to $10,000 (with a cumulative cap of $50,000) were available to mitigate the additional tuition and fees charged to out-of-state students at public IHEs exclusively in Maryland and Virginia. Additionally, annual grants of $2,500 (with a cumulative cap of $12,500) were available exclusively for tuition and fees at a limited number of private, nonprofit IHEs and private, nonprofit historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) in Maryland and Virginia. Both the $10,000 grant for attendance at a public institution and the $2,500 grant for attendance at certain private, nonprofit schools were intended to assist DC high school graduates in pursuing a postsecondary education and to provide them with a "greater range of options" for their postsecondary education.11

The act also included a provision12 that permitted the mayor of the District of Columbia to broaden the list of public institutions eligible to receive program funds, which could include IHEs outside Maryland and Virginia. In May 2000, Mayor Anthony Williams exercised this administrative authority and expanded the program to provide up to $10,000 per student per year (with a cumulative cap of $50,000) toward the difference between in-state and out-of-state undergraduate tuition and fees at all public colleges and universities nationwide.

The District of Columbia College Access Improvement Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-157) further amended the program to provide awards of up to $2,500 per student per year (with a cumulative cap of $12,500) to assist students with paying the tuition and fees for any private, nonprofit HBCU nationwide. The addition of these eligible institutions was intended to help expand DC residents' access to HBCUs nationwide.13

Since its original authorization in 1999, the DCTAG program has been reauthorized twice, once in 2004 (P.L. 108-457) and again in 2007 (P.L. 110-97). The 2007 reauthorization extended the appropriation of funds for the DCTAG program through FY2012 and introduced a means-testing provision prohibiting Washington, DC, residents from families with taxable annual incomes of $1,000,000 or greater from receiving awards.

Additionally, eligibility criteria for the DCTAG program have been amended twice through appropriations acts. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113) lowered the maximum family income limit from $1,000,000 to $750,000 for students beginning an undergraduate program in school year 2016-2017, with the amount to be adjusted for inflation in subsequent years. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6) further reduced the maximum family income limit to $500,000 for students beginning an undergraduate program in school year 2019-2020, with the amount to be adjusted for inflation in subsequent years.

Program Structure

The following section provides an overview of how the DCTAG program operates. It addresses eligibility criteria for institutions and students, application and disbursement procedures, interactions between DCTAG awards and federal student aid, and program administration.

Eligibility

Institution

The size of the DCTAG award that a District of Columbia resident can receive is based on the type of institution attended (see Table 1). District of Columbia residents are eligible to receive DCTAG funds in amounts not to exceed $10,000 per student per year (with a total per student cap of $50,000) to attend any public Title IV-eligible14 two-year15 or four-year IHE in the United States.16 Because the UDC provides an in-state tuition rate for DC students, District of Columbia residents are specifically prohibited from using DCTAG funds to reduce the cost of attending UDC. Likewise, students may not use DCTAG funds to attend the Community College of the District of Columbia—the open-admission, two-year IHE that was split off from UDC in August 2009 as a separate institution—because it offers reduced tuition to residents of Washington, DC.

Private, nonprofit Title IV-eligible HBCUs17 nationwide and private, nonprofit Title IV-eligible IHEs18 in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area (defined as the District of Columbia; the cities of Alexandria, Falls Church, and Fairfax in Virginia; Arlington and Fairfax counties in Virginia; and Montgomery and Prince George's counties in Maryland)19 are eligible to accept DCTAG funds in amounts not to exceed $2,500 per student per year (with a total per student cap of $12,500).

|

Maximum Annual and Lifetime Awards |

Public |

Private, Nonprofit Title IV-Eligible IHEs in the Washington, DC, Metropolitan Area |

Private, Nonprofit Title IV-Eligible HBCUs Nationwide |

|

Maximum annual award |

$10,000 |

$2,500 |

$2,500 |

|

Student lifetime cap |

$50,000 |

$12,500 |

$12,500 |

Source: Table compiled by CRS based on review of the District of Columbia College Access Act, D.C. Code §38-2701 et seq.

To receive funds under the DCTAG program, any of the aforementioned institutions, except HBCUs, are required to enter into an agreement with the mayor of the District of Columbia regarding reporting requirements and the institution's use of funds to supplement, not supplant, assistance that it would otherwise provide eligible students.20

Student

To become and remain eligible for a grant under the DCTAG program, a student must

- be a resident of the District of Columbia;

- be a citizen, national, or permanent resident of the United States; be able to provide evidence from the Immigration and Naturalization Service that he or she is in the United States for other than a temporary purpose with the intention of becoming a citizen or permanent resident; or be a citizen of any one of the Freely Associated States;

- be enrolled or accepted for enrollment, on at least a half-time basis, in a degree, certificate, or other program (including a study-abroad program approved for credit by the student's home institution) leading to a recognized educational credential at an eligible institution;

- maintain satisfactory progress in his or her course of study, as defined by Section 484(c) of the Higher Education Act of 1965, as amended;

- not be in default on a federal student loan;

- be 26 years of age or younger;21

- have either graduated from a secondary school or received the equivalent of a secondary school diploma or have been accepted for enrollment as a freshman at an eligible institution; and

- be domiciled in the District of Columbia for not less than the 12 consecutive months preceding enrollment at an eligible IHE, if undergraduate study is started within three calendar years22 of high school graduation or its equivalent or be domiciled in the District of Columbia for not less than five consecutive years preceding enrollment at an eligible IHE, if undergraduate study is started more than three calendar years after high school graduation or its equivalent.

Post-baccalaureate students who have already earned a bachelor's degree or students whose family's federal taxable income exceeds the maximum limit23 are ineligible to participate in the DCTAG program.24

Application

To receive funds through the DCTAG program, an eligible student must25

- first submit a DC OneApp, the District of Columbia's online application that District residents use to apply for the District of Columbia's state-level higher education grant programs;

- then fill out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA); and

- finally, submit required supporting DC OneApp documents, including income or benefits verification or a document26 no older than 45 days from the date of the DC OneApp submission that reflects the name and address of either the applicant or their parent or legal guardian, proof of high school or equivalent completion (first-time applicants only), and a student aid report.27

Payments

After a student submits a successful application and the grant size is determined, awards are paid directly to the eligible IHE at which the student is enrolled. In the case of public institutions, the grant may be no larger than the difference between the in-state and out-of-state tuition and fees, and in no case may the grant be larger than $10,000 per year, as previously indicated in Table 1. Grants awarded to students attending school on a less than full-time basis are prorated.

To participate in the DCTAG program, institutions must complete (or have completed) a Program Participation Agreement; submit a W-9 form; enter cost of attendance, credit hour cost, in/out of state tuition, and contact information in DC OneApp; and submit an invoice to DCTAG for payment through DC OneApp.

Interaction with Federal Student Aid

Because DCTAG funds are not intended to cover the full cost of college attendance, students may seek additional sources of financial assistance. Title IV federal student aid programs administered by the U.S. Department of Education constitute a large share of such support. The maximum loan or grant amount for each of these programs is determined by a different need analysis calculation involving, but not limited to, the cost of attendance and the total estimated financial assistance from other sources.28 For the purpose of these calculations, funds received through the DCTAG program would most likely be considered either scholarships or state grants, both of which are considered estimated financial assistance.29 As a result, receiving a DCTAG award may reduce the federal student aid available to a student. For a list of additional student support available to District of Columbia residents, see the Appendix.

Administration

The DCTAG program is administered by the mayor of the District of Columbia, through the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). As mandated by statute, the District of Columbia government established a dedicated account for program funds, with separate line items for federal appropriations, District government contributions, unobligated balances from prior appropriations, and interest earned on the balance.30 If the funds made available for the program are not sufficient to fully support all applicants at the maximum allowable grant amount, the mayor is required to ratably reduce awards—first reducing those granted to first-time recipients and then those granted to renewing recipients. Should this be required, the mayor is authorized to apply ratable reductions based on student financial need and administrative burden.

Appropriations

The DCTAG program is funded through annual appropriations, which are available until expended and do not expire at the end of each fiscal year. From the program's inception through FY2007, these funds were included in annual District of Columbia Appropriations Acts; beginning in 2008, program funds were appropriated through annual Federal Services and General Government Appropriations Acts. Between FY2010 and FY2015, funding for the DCTAG program either remained level or decreased through various appropriations acts and continuing resolutions. Appropriated funds increased in FY2016, however, and have remained at that level ever since. Table 2 details the funding levels for each year of the program's existence.

|

Fiscal Year |

Appropriations Act |

Appropriation (in millions) |

Percentage Change from Prior Year |

|

2000 |

$17.0 |

— |

|

|

2001 |

$17.0 |

0.0% |

|

|

2002 |

$17.0 |

0.0% |

|

|

2003 |

$17.0 |

0.0% |

|

|

2004 |

$17.0 |

0.0% |

|

|

2005 |

$25.4 |

49.4% |

|

|

2006 |

$32.9 |

29.5% |

|

|

2007 |

$32.9 |

0.0% |

|

|

2008 |

$33.0 |

0.3% |

|

|

2009 |

$35.1 |

6.4% |

|

|

2010 |

$35.1 |

0.0% |

|

|

2011 |

$35.1 |

0.0% |

|

|

2012 |

$30.0 |

-14.5% |

|

|

2013 |

$28.4f |

-5.0% |

|

|

2014 |

$30.0 |

5.3% |

|

|

2015 |

$30.0 |

0.0% |

|

|

2016 |

$40.0 |

33.3% |

|

|

2017 |

$40.0 |

0.0% |

|

|

2018 |

$40.0 |

0.0% |

|

|

2019 |

$40.0 |

0.0% |

Source: District of Columbia Appropriations Acts, FY2000-2007; Federal Services and General Government Appropriations Acts, FY2008-2019.

a. P.L. 109-115 initially appropriated $33.2 million for the DCTAG program in FY2006. P.L. 109-148 instituted an across-the-board rescission of 1%, which reduced the program appropriation to $32.9 million, as shown.

b. P.L. 109-289 was the first of four continuing resolutions (CRs) that funded DCTAG in FY2007. The other CRs maintained the DCTAG program's funding at the FY2006 level. See P.L. 109-369, P.L. 109-383, and P.L. 110-5.

c. P.L. 111-242 was the first of several CRs that funded DCTAG in FY2011, all of which maintained the DCTAG program's funding at the FY2010 level. See P.L. 111-290, P.L. 111-317, P.L. 111-322, P.L. 112-4, P.L. 112-6, P.L. 112-8, and P.L. 112-10.

d. P.L. 112-33 was followed by five CRs that maintained the $30 million funding amount for DCTAG in FY2012. See P.L. 112-36, P.L. 112-67, P.L. 112-68, P.L. 112-77, and P.L. 112-74.

e. P.L. 113-6 is a CR that provides funding through the end of FY2013. It was preceded by P.L. 112-175, which was a CR that that provided funding through March 27, 2013.

f. FY2013 appropriations reflect the final amount appropriated, including the 5% across-the-board spending reduction authorized by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA; P.L. 112-25), commonly referred to as "sequestration."

Performance

Aside from general administrative duties that the District of Columbia must fulfill under the DCTAG program, the mayor must submit to Congress an annual report detailing the number of eligible students served and the amount of grant awards disbursed, any reduction in grant size, and the credentials earned by eligible student cohorts. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) also is required to monitor the program, particularly with respect to barriers to enrollment for program participants and overall program efficacy.31 In 2018, GAO released a report that recommended the District of Columbia's OSSE issue annual reports relating DCTAG's performance to program goals.32 The Mayor of the District of Columbia has stated that OSSE will expand annual reporting to link performance data more directly to program goals.33 The remainder of this section of the report provides program performance data for the DCTAG program.

Students Served

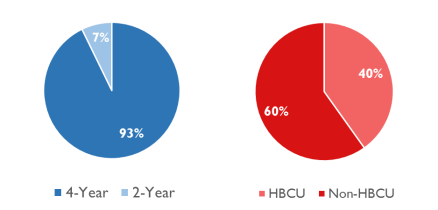

Through academic year 2017-2018, a total of 28,998 students have received approximately $505.8 million in DCTAG awards and have attended over 500 IHEs in 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.34 In AY2017–2018 alone, approximately $32.5 million in DCTAG funds supported 4,571 students enrolled in postsecondary institutions.35 In that same year, 93% of DCTAG participants were enrolled in four-year institutions. Forty percent of participants were enrolled at HBCUs, as shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1. DCTAG Awards by Institution Type AY2017-2018 |

|

|

Source: OSSE, DCTAG Program Annual Data Report 2017-2018, April 2019. |

In the fall of 2016, 2,465 District of Columbia residents who had graduated from high school within the previous 12 months enrolled in Title IV-eligible two- or four-year degree-granting IHEs as freshmen.36 That same year, 1,335 DCTAG awards were disbursed to first-time recipients who had graduated from high school in the previous academic year, meaning that approximately 54% of the recent high school graduates from Washington, DC, who enrolled as freshmen at IHEs in fall 2016 received DCTAG funds. This figure does not include those students who enrolled at ineligible institutions or otherwise did not meet eligibility requirements. Therefore, the DCTAG program does appear to assist a relatively large number of those students choosing to pursue a postsecondary education at eligible IHEs shortly after graduating high school in financing their postsecondary education.

Awards Versus High School Enrollment

In AY2017-2018, 79% of DCTAG program participants had attended a high school that was either in the District of Columbia Public Schools system or a public charter school, while about 16% of participants had attended a private high school.37 According to data collected in the 2017 American Community Survey, 82% of all District of Columbia residents who were enrolled in grades 9-12 attended public schools while 18% attended private schools.38 These data suggest that DCTAG program participants have begun to reflect the DC high school student population as a whole more closely than in the past.39 For instance, from AY2006-2007 though AY2011-2012, approximately 27% of DCTAG recipients had attended a private high school,40 while only about 15% of DC high school students overall had done so.41

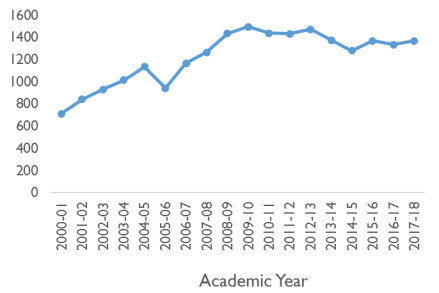

Since its inception, DCTAG participation has increased, and the number of recent high school graduate participants also has increased significantly; however, participation rates have leveled off somewhat in recent years, as shown in Figure 2.

Grants by Ward

The District of Columbia is divided into eight subdivisions, or wards, each of which is home to an average of about 84,000 residents.42 Every ward is represented in the DC Council by an elected councilmember, making wards discrete political units. Because household income, educational attainment, and other social factors vary greatly among the wards, measures of social equity are often calculated by ward.

OSSE data demonstrate how awards have been distributed across wards in the past several years. Table 3 compares the median family income and the percentage of DCTAG recipients within each ward. The data seem to indicate that those wards with the lowest median family income (i.e., wards 4, 5, 7, and 8) have a higher percentage of DCTAG recipients than those wards with the highest median family income (i.e., wards 1, 2, 3, and 6). The 2017 median household income for recipients was $41,038.43 However, it is also important to note that the number of DCTAG-eligible students is not equal across wards.44

|

Ward 1 |

Ward 2 |

Ward 3 |

Ward 4 |

Ward 5 |

Ward 6 |

Ward 7 |

Ward 8 |

|

|

Median Family Income 2013-2017a |

$112,485 |

$178,325 |

$210,561 |

$106,086 |

$80,843 |

$143,894 |

$47,090 |

$35,420 |

|

Share of DCTAG Recipients 2013-2017 |

6.9% |

2.6% |

8.7% |

19.0% |

16.5% |

8.7% |

20.1% |

16.9% |

Source: District of Columbia Office of Planning, American Community Survey (ACS) Estimates, "2013-2017 ACS 5-Year Ward"; CRS analysis based on data from OSSE, FY18 Performance Oversight Questions, Q67 Attachment – DCTAG.

a. The median family income was calculated using 2017 inflation-adjusted dollars.

Graduation Rates

The most recent OSSE data available suggest that the six-year undergraduate graduation rate for DCTAG recipients may be below the national average.45 For instance, for the cohort that began pursuing a bachelor's degree in academic year 2010-2011, nationwide, 59.8% of students completed their bachelor's degree within six years of enrollment,46 whereas 41.6% of DCTAG recipients graduated within six years of enrollment.47

Analysis of Grant Benefits

While there has been a substantial increase in the amount of funds appropriated for the DCTAG program (see Table 2) and the maximum award size for students attending public two-year institutions since the program's inception, there has been no change to the maximum award size for students attending other types of institutions. In light of the trend of rising postsecondary education costs, many program participants may be left paying more per year for their education than in previous years or possibly limiting their choices of which institution to attend. The extent to which DCTAG awards may be covering a declining proportion of the differential between in-state and out-of-state tuition is a commonly raised concern about the DCTAG program. This section of the report examines the extent to which the maximum award may be bridging the gap between in-state and out-of-state tuition. It also examines growth in maximum awards as a share of all awards. The most recent data available are from the 2011-2012 academic year.48

Public Institutions of Higher Education

Most DCTAG recipients choose to attend a public four-year IHE,49 for which they can receive up to $10,000 per year toward the difference between in- and out-of-state tuition. Even though the number of DCTAG recipients on the whole has remained relatively stable between AY2004-2005 and AY2011-2012,50 there was a consistent increase in the number of maximum awards disbursed each year, as shown in Table 4. The nationwide increase in tuition and fees may be contributing to this upturn in maximum awards received,51 although there may be other factors that impact this.

|

2004-2005 |

2005-2006 |

2006-2007 |

2007-2008 |

2008-2009 |

2009-2010 |

2010-2011 |

2011-2012 |

||

|

DCTAG Enrollment |

4,759 |

4,631 |

4,452 |

4,580 |

4,686 |

5,070 |

5,103 |

5,253 |

|

|

Number of |

922 |

1,059 |

1,010 |

1,223 |

1,384 |

1,508 |

1,518 |

1,521 |

|

|

Percentage of participants receiving $10,000 awards |

19.4% |

22.9% |

22.7% |

26.7% |

29.5% |

29.7% |

29.7% |

28.9% |

|

Source: Compiled using data from OSSE, DCTAG Accomplishments 2013, pp. 3 and 13 and data provided by OSSE, December 20, 2013.

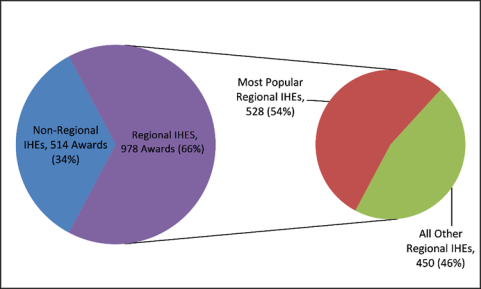

In AY2011-2012, 66% of those DCTAG recipients who received the maximum annual DCTAG award of $10,000 enrolled at public four-year IHEs in Delaware, Maryland, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Virginia (regional IHEs). Moreover, most of those students enrolled in a small number of those regional IHEs. For instance, Figure 3 shows that of the 978 students who received the maximum $10,000 DCTAG award and attended a regional IHE in AY2011-2012, 528 (54%) attended one of six schools: Pennsylvania State University, University Park; Bowie State University; George Mason University; Norfolk State University; the University of Maryland, College Park; and Virginia Commonwealth University; the other 450 (46%) students who received the maximum award attended 53 other regional IHEs.52

|

Figure 3. AY2011-2012 Number of Maximum DCTAG Awards at Public Four-Year IHEs, by Location |

|

|

Source: Compiled using data provided by the OSSE, December 20, 2013. |

The average in- and out-of-state tuition differential for these six most-attended regional IHEs was $14,092; therefore, on average, a DCTAG recipient who attended one of these schools and who received the maximum annual award would still face a gap of an average of $4,092 in out-of-state tuition.53

To meet the program's stated purpose of providing access to a greater range of postsecondary educational options, Congress could consider increasing the maximum annual DCTAG award to account for the in- and out-of-state tuition differential at popular regional public IHEs at which many DCTAG recipients are receiving the maximum annual award. Such a decision would likely be weighed in relation to competing demands for resources. Alternatively, Congress could consider better matching individual students' financial need to DCTAG funds awarded through means testing or by lowering the current $500,000 family income cap for participation.

Private Nonprofit Schools and Private HBCUs

Tuition and fees at private, nonprofit four-year IHEs also have grown considerably since DCTAG was created, but the maximum annual award—$2,500—has not increased. Table 5 shows that, between AY2004-2005 and AY2011-2012, the median tuition and fees54 for such institutions in the District of Columbia increased by 42.5%,55 while the percentage of DCTAG recipients enrolled in DC area private, nonprofit four-year IHEs in each year has decreased slightly.

Table 5. DCTAG Participants Enrolled in and Median Full-Time Enrollment Undergraduate Tuition and Fees at District of Columbia Private, Nonprofit Title IV-Eligible Four-Year IHEs

|

Academic Year 2004–2005 |

Academic Year 2011-2012 |

Difference |

Percentage Change |

|

|

Tuition and Fees |

$23,025 |

$32,800 |

$9,775 |

42.5% |

|

DCTAG Participantsa |

469 |

489 |

20 |

4.3% |

|

Share of DCTAG Participants |

9.9% |

9.3% |

— |

— |

Source: Compiled using the National Center for Education Statistics' Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, December 23, 2013, http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/, and data provided by the OSSE, December 20, 2013.

a. The number of DCTAG participants presented in this table represents the aggregate number of students enrolled full-time and part-time.

Table 6 shows a similar but slightly more pronounced result for DCTAG participants choosing to attend private, nonprofit HBCUs. From AY2004-2005 to AY2011-2012, the median tuition and fees at such institutions increased by 38.3%, while the number of DCTAG recipients attending decreased by 2.6%.

Table 6. DCTAG Participants Enrolled in and Median Full-Time Enrollment Undergraduate Tuition and Fees at Private Nonprofit Title IV-Eligible HBCUs

|

Academic Year 2004-2005a |

Academic Year 2011–2012 |

Difference |

Percentage Change |

|

|

Tuition and Fees |

$9,596 |

$13,275 |

$3,679 |

38.3% |

|

DCTAG Participantsb |

581 |

566 |

-15 |

-2.6% |

|

Share of DCTAG Participants |

12.2% |

10.8% |

— |

— |

Source: Compiled using the National Center for Education Statistics' Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, December 23, 2013 , http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/, and data provided by the OSSE, December 20, 2013.

a. The District of Columbia College Access Improvement Act of 2002, P.L. 107-157, which amended the DCTAG program to provide awards to assist students with paying the tuition and fees for any private HBCU nationwide was passed in 2002; however, funds were retroactively disbursed to students attending private HBCUs in AY2001-2002. Because the students likely did not know of the potential awards upon choosing to attend a private HBCU in AY2001-2002, these figures were not included in this table. Rather, a later academic year in the program's existence was chosen, as it is likely more representative of students' school choices.

b. The number of DCTAG participants presented in this table represents the aggregate number of students enrolled full-time and part-time.

Although the increase in tuition and fees at DC private, nonprofit IHEs and private HBCUs nationwide may not have deterred DCTAG recipients from attending such schools, the unchanged $2,500 award does not go as far as it did previously relative to the cost of tuition and fees, thereby causing recipients to pay more out-of-pocket costs than in years past.

Appendix. Other Higher Education Support Programs for District of Columbia Residents

In addition to federal student aid, there are other programs that are available to residents of Washington, DC:

- The District of Columbia College Access Program (DC CAP)56 is a nonprofit organization that was founded in 1999 to encourage and enable DC high school students to enroll in postsecondary schools and provides them with educational counseling and financial assistance to help them succeed. In partnership with the District of Columbia Public School system (DCPS), District of Columbia charter schools, and OSSE, DC CAP serves DC high school students, primarily from low-income, minority, and single-parent households, during both high school and college, through counseling, seminars, and preparatory programs. In addition, the organization offers high school graduates need-based Last Dollar Awards of up to $2,000 per student per year for up to five years to cover unmet college expenses.

- The Mayor's Scholars Undergraduate Fund provides need-based grants of up to $4,000 to eligible DC residents, which they can apply towards the cost of pursuing their first undergraduate degree at certain eligible institutions located in the DC area. Individuals who receive DCTAG assistance are also eligible to receive Mayor's Scholars Undergraduate Fund grants. The program was first announced in October 2012 and began operating in FY2013.57

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Previous versions of this report were authored by Alexandra Hegji, Analyst in Social Policy, and by Christopher S. Van Orden, former Presidential Management Fellow.

Footnotes

| 1. |

Raoul Dennis, "Accreditation Renewed for the University of the District of Columbia," Black Issues in Higher Education, December 11, 1997, pp. 16–17. |

| 2. |

"News and Views: UDC; A Chain of Calamities," The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, June 30, 1997, p. 72. |

| 3. |

"Jurisdiction" is defined here as the 50 U.S. states and Washington, DC. |

| 4. |

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), "Residence and Migration of all freshmen students in degree-granting institutions, by state: Fall 1998." |

| 5. |

Thomas Kane, Evaluating the Impact of the D.C. Tuition Assistance Grant Program, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 10658, August 2004, pp. 1–2, http://www.nber.org/papers/w10658. |

| 6. |

CRS Report R44172, Financial Services and General Government (FSGG): FY2015 Appropriations. |

| 7. |

CRS Report RS20990, The District of Columbia Financial Responsibility and Management Assistance Act, P.L. 104-8: An Overview of the Law and Related Amendments (archived report, available to congressional clients upon request). |

| 8. |

In another effort to promote the growth of Washington, DC's middle class, Congress established a $5,000 tax credit for first-time home buyers in Washington, DC, under the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 (P.L. 105-34). CRS Report 97-766, District of Columbia Revitalization: Legislation Enacted Under the 105th Congress, (archived report, available to congressional clients upon request). |

| 9. |

The law is also codified at the local level as Division VI, Title 38, Subtitle IX, Chapter 27 of the DC Code. |

| 10. |

P.L. 106-98 §1. |

| 11. |

U.S. Congress, House of Representatives Committee on Government Reform, District of Columbia College Access Act, report to accompany H.R. 974, 106th Cong., 1st sess., May 24, 1999, H.Rept. 106-158, p. 5; U.S. Congress, Hearing before the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, Oversight of Government Management, Restructuring and the District of Columbia Subcommittee, H.R. 974—The District of Columbia College Access Act and S. 856—The Expanded Options in Higher Education for District of Columbia Students Act of 1999, 106th Cong., 1st sess., June 24, 1999, S. Hrg. 106-252, p. 9. U.S. Congress, Senate Labor and Public Welfare, Education Amendments of 1971, report to accompany S. 659, 92nd Cong., 1st sess., August 3, 1971, S.Rept. 92-346 (Washington: GPO, 1971), p. 115. |

| 12. |

P.L. 106-98 §3(c)(1)(a)(ii). |

| 13. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, District of Columbia College Access Improvement Act of 2001, report to accompany H.R. 1499, 107th Cong., 1st sess., November 29, 2001, S.Rept. 107-101, p. 4. |

| 14. |

"Title IV-eligible" refers to an IHE's eligibility to participate in the federal student aid programs authorized under Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965 (P.L. 89-329), as amended, such as the Direct Loan program. For additional information on Title IV eligibility requirements, see CRS Report R43159, Institutional Eligibility for Participation in Title IV Student Financial Aid Programs. |

| 15. |

Since AY 2017-2018, the maximum award amount for public two-year IHEs has been equal to that for public four-year IHEs. Prior to that year, the maximum award amount for public two-year IHEs was $2,500. |

| 16. |

A full list of eligible, participating institutions can be found at District of Columbia Office of State Superintendent of Education (OSSE), "DCTAG Participating Colleges Institutions." |

| 17. |

As defined in §322(2) of the Higher Education Act of 1965 (20 U.S.C. 1061(2)). |

| 18. |

As defined in §101(a) of the Higher Education Act of 1965 (20 U.S.C. 1001(a)). |

| 19. |

D.C. Code §38-2704(c)(1)(A)(i). |

| 20. |

D.C. Code §38-2702(c)(1)(C). |

| 21. |

Students must be 26 years of age or younger throughout the duration of their participation in the program. The maximum age was raised from 24 years old effective AY2017-2018. |

| 22. |

Periods of service in the Armed Forces or the Peace Corps or National Service, as defined in Subtitle D of Title I of the National and Community Service Act of 1990 (42 U.S.C. 12571 et. seq.), are excepted from this time limit. |

| 23. |

For the 2019-2020 academic year, the maximum family taxable income is $500,000 for students who begin an undergraduate course of study in that year. For students who began their undergraduate program from academic year 2016-2017 to academic year 2018-2019, the maximum family taxable income is $796,671 (adjusted for inflation from $750,000) for academic year 2019-2020. For students who began their undergraduate program prior to academic year 2015-2016, the maximum family taxable income is $1,062,228 (adjusted for inflation from $1,000,000). OSSE, Information on DCTAG Maximum Income, https://osse.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/osse/page_content/attachments/Information%20on%20DCTAG%20Maximum%20Income%203.4.2019.pdf. |

| 24. |

D.C. Code §38-2702(c)(2). |

| 25. |

OSSE, DCTAG Apply and Submit, https://osse.dc.gov/node/1362081. |

| 26. |

The document may be a current utility bill or letter, phone bill (land line, not cell phone), bank statement, pay stub, or mortgage statement. |

| 27. |

OSSE, DCTAG Required Supporting Documents Checklist, https://osse.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/osse/publication/attachments/2019-20%20Supporting%20Documents%20Checklist.pdf. |

| 28. |

See CRS Report R45931, Federal Student Loans Made Through the William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan Program: Terms and Conditions for Borrowers. |

| 29. |

See Federal Student Aid Handbook: 2019-2020, vol. 3, Ch. 7, https://ifap.ed.gov/fsahandbook/attachments/1920FSAHbkVol3Ch7.pdf. |

| 30. |

D.C. Code §38-2705(h). |

| 31. |

Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31), §4. Mandate incorporated by reference from S.Rept. 114-280. |

| 32. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, District of Columbia: Improved Reporting Could Enhance Management of the Tuition Assistance Grant Program, GAO-18-527, September 2018, https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-527. |

| 33. |

Ibid. |

| 34. |

OSSE, District of Columbia Tuition Assistance Grant Program Annual Data Report 2017-18, April 2019, https://osse.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/osse/page_content/attachments/DCTAG%20Annual%20Data%20Report%202017-18%20as%20of%20April%202019.pdf. |

| 35. |

Ibid. |

| 36. |

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, 2016, Table 309.20, "Residence and Migration of All First-Time Degree/Certificate-Seeking Undergraduates in Degree-Granting Institutions Who Graduated from High School in the Past 12 Months, by State or Jurisdiction: Fall 2016," https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_309.20.asp. |

| 37. |

OSSE, District of Columbia Tuition Assistance Grant Program Annual Data Report 2017-18, April 2019, https://osse.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/osse/page_content/attachments/DCTAG%20Annual%20Data%20Report%202017-18%20as%20of%20April%202019.pdf. |

| 38. |

U.S. Census Bureau, American FactFinder, American Community Survey, School Enrollment by Level of School by Type of School for the Population 3 Years and Over, 2017, https://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/17_1YR/C14002/0400000US11. |

| 39. |

As all DCTAG recipients are high school graduates, it would also be appropriate to compare the types of high schools attended by DCTAG recipients versus other DC high school graduates in a given year; however, such data is not readily available. |

| 40. |

OSSE, DCTAG Accomplishments 2013. |

| 41. |

U.S. Census Bureau, American FactFinder, American Community Survey, School Enrollment by Level of School by Type of School for the Population 3 Years and Over, 2010-2012, https://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/12_3YR/C14002. |

| 42. |

District of Columbia Office of Planning, American Community Survey (ACS) Estimates, "2013-2017 ACS 5-Year Ward," https://planning.dc.gov/page/american-community-survey-acs-estimates. |

| 43. |

OSSE, District of Columbia Tuition Assistance Grant Program Annual Data Report 2017-18, April 2019, https://osse.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/osse/page_content/attachments/DCTAG%20Annual%20Data%20Report%202017-18%20as%20of%20April%202019.pdf. |

| 44. |

For instance, from AY2013-2014 through AY2016-2017, the number of students enrolled in DC Public Schools who reside in Ward 8 was more than 11 times the number of students enrolled in DC Public Schools who reside in Ward 2. OSSE, Data and Reports, Supporting Data from OSSE's 2016 Performance Oversight Hearing – Enrollment. |

| 45. |

Data for graduation rates of DCTAG recipients and for nationwide graduation rates are not strictly comparable. The National Center for Education Statistics defines the six-year graduation rate as the percentage of first-time, full-time students who began pursuing a bachelor's degree at a four-year institution and completed the bachelor's degree at the same institution within six years of the start date. OSSE defines the DCTAG six-year graduation rate as the percentage of students awarded DCTAG at a four-year institution, including both full-time and part-time, who graduated from any institution within six years of their first year. |

| 46. |

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, 2017, Table 326.10, "Graduation rate from first institution attended for first-time, full-time bachelor's degree- seeking students at 4-year postsecondary institutions, by race/ethnicity, time to completion, sex, control of institution, and acceptance rate: Selected cohort entry years, 1996 through 2010," https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_326.10.asp. |

| 47. |

OSSE, FY18 Performance Oversight Questions, Q67 Attachment – DCTAG. https://osse.dc.gov/page/fy18-performance-oversight-questions. |

| 48. |

CRS has placed a request with the DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education for updated data, but those data have not yet been made available. |

| 49. |

OSSE, District of Columbia Tuition Assistance Grant Program Annual Data Report 2017-18, April 2019, https://osse.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/osse/page_content/attachments/DCTAG%20Annual%20Data%20Report%202017-18%20as%20of%20April%202019.pdf.. |

| 50. |

DCTAG funds were not disbursed to students until AY2000-2001 and the program was still in the initial implementation phase at that time, not necessarily operating at full capacity; therefore, the first few years of program details may not be representative of the DCTAG program when fully operational and were not included in Table 4. |

| 51. |

In this analysis, it is assumed that a $10,000 award is indicative of the in- and out-of-state tuition differential exceeding $10,000. |

| 52. |

OSSE, December 20, 2013. |

| 53. |

An analysis of popularly attended regional IHEs is provided because data allowing for a weighted average of the differential faced by maximum award recipients across all IHEs are not readily available. |

| 54. |

The dollar amounts of tuition and fees in this analysis are not adjusted for inflation. |

| 55. |

DCTAG funds are available for study at private Title IV-eligible IHEs only in the DC metropolitan area. DC institutions alone have been selected to demonstrate the regional trend. |

| 56. |

DC CAP, 16 Year Report Card, 1999-2016, https://dccap.org/about/16-year-report-card. |

| 57. |

DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, "Mayor Gray and OSSE Announce First-ever DC College Fund," press release, October 5, 2012, http://osse.dc.gov/release/mayor-gray-and-osse-announce-first-ever-dc-college-fund; D.C. Office of the State Superintendent of Education, "DC Mayor's Scholarship Undergraduate Fund," https://osse.dc.gov/mayorsscholars. |