U.S. National Health Security: Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress

In its quadrennial National Health Security Strategy, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) states:

U.S. National Health Security actions protect the nation's physical and psychological health, limit economic losses, and preserve confidence in government and the national will to pursue its interests when threatened by incidents that result in serious health consequences whether natural, accidental, or deliberate.

The strategy aims to ensure the resilience of the nation's public health and health care systems against potential threats, including natural disasters and human-caused incidents, emerging and pandemic infectious diseases, acts of terrorism, and potentially catastrophic risks posed by nation-state actors.

By law, the HHS Secretary "shall lead all Federal public health and medical response to public health emergencies and incidents covered by the [National Response Framework]," and the HHS Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) shall "[s]erve as the principal advisor to the Secretary on all matters related to Federal public health and medical preparedness and response for public health emergencies." However, under the nation's federal system of government, state and local agencies and private entities are principally responsible for ensuring health security and responding to threats. The federal government's ability to affect national health security, through funding assistance and other policies, is relatively limited.

|

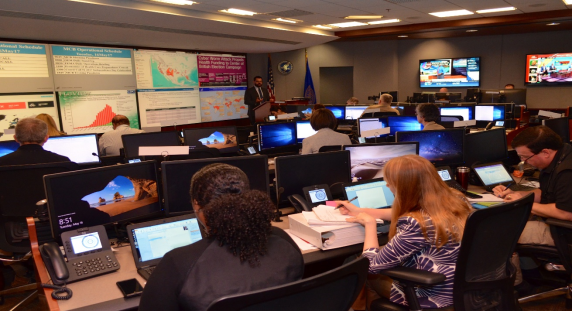

Figure 1. HHS Secretary's Operations Center (SOC), |

|

|

Source: Office of the HHS Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, February 6, 2019. Notes: The health care sector was a significant target of the cyberattack. The image shows a staff briefing on cyber threat information sharing and other efforts to protect health care infrastructure. |

The nation's public health emergency management laws have expanded considerably following the terrorist attacks in 2001. Since then, a number of public health emergencies revealed both improvements in the nation's readiness, and persistent gaps. The National Health Security Preparedness Index (NHSPI, or the Index), a public-private partnership begun in 2013, currently assesses preparedness, using 140 measures, across all 50 states and the District of Columbia. In its latest comprehensive report, for 2017, NHSPI found overall incremental improvements over earlier years. However, the report highlighted differing preparedness levels among states, stating:

Large differences in preparedness persisted across states, and those in the Deep South and Mountain West regions lagged significantly behind the rest of the nation. If current trends continue, the average state will require 9 more years to reach health security levels currently found in the best-prepared states.

In addition, measures of health care delivery—for example, the number of certain types of health care providers (including mental health providers) per unit of population, access to trauma centers, the extent of preparedness planning in long-term care facilities, and uptake of electronic health record systems—continued to yield the lowest scores.

The readiness of individual health care facilities and services to respond to a mass casualty incident or other public health emergency has been a persistent health security challenge. Aiming to address this, the HHS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has implemented a rule that requires 17 different types of health care facilities and service providers to meet a suite of preparedness benchmarks in order to participate in (i.e., receive payments from) the Medicare and Medicaid programs. The Emergency Preparedness (EP) Rule became effective in November, 2017. Policymakers may be interested to see, in NHSPI results and through other studies, the extent to which the EP Rule yields meaningful improvements in national health system preparedness in the future.

For incidents declared by the President as major disasters or emergencies under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (P.L. 93-288, as amended), public assistance is available to help federal, state, and local agencies with the costs of some public health emergency response activities, such as ensuring food and water safety. However, no federal assistance program is designed specifically to cover the uninsured costs of individual health care services that may be needed as a consequence of a disaster. There is no consensus that this should be a federal responsibility. Nonetheless, during mass casualty incidents, hospitals and health care providers may face expectations to deliver care without a clear payment source of reimbursement. Also, the response to an incident could necessitate activities that begin before Stafford Act reimbursement to HHS has been approved, or that are not eligible for reimbursement under the act. (For example, there is no precedent for a major disaster declaration under the Stafford Act for an outbreak of infectious disease, and only one declaration of emergency, for West Nile virus in 2000.) Although the HHS Secretary has authority for a no-year Public Health Emergency Fund (PHEF), Congress has not appropriated monies to it for many years, and no funds are currently available.

On several occasions Congress has provided supplemental appropriations to address uncompensated disaster-related health care costs and otherwise unreimbursed state and local response costs flowing from a public health emergency. These incidents include Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Sandy, the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, and the Ebola and Zika virus outbreaks. Supplemental appropriations for hurricane relief were provided for costs (such as uncompensated care) that were not reimbursed under the Stafford Act. The act was not invoked for the three infectious disease incidents, and supplemental appropriations were therefore needed to fund most aspects of the federal response to those outbreaks.

Some policymakers, concerned about the inherent uncertainty in supplemental appropriations, have proposed dedicated funding approaches for public health emergency response. Two proposals in the 115th Congress (S. 196, H.R. 3579) would have appropriated funds to the PHEF. These measures did not advance. In appropriations for FY2019 (P.L. 115-245), Congress established and appropriated $50 million (to remain available until expended) to an Infectious Diseases Rapid Response Reserve Fund, to be administered by the Director of the HHS Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) "to prevent, prepare for, or respond to an infectious disease emergency." The 116th Congress may choose to examine any uses of this new fund by CDC, and to consider appropriations to the PHEF, as well as other options to improve national health security preparedness.