Introduction

The United States currently has a population of almost 1 million lawfully present foreign workers and accompanying family members who have been approved for, but have not yet received, a green card or lawful permanent resident (LPR) status.1 This queue of prospective immigrants—the employment-based backlog—is dominated by Indian nationals. It has been growing for decades and is projected to double in less than 10 years.

The employment-based immigrant backlog exists because the annual number of foreign workers whom U.S. employers hire and then sponsor to enter the employment-based immigration pipeline has regularly exceeded the annual statutory allocation of green cards. The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) that governs U.S. immigration policy limits the total annual number of employment-based green cards to 140,000 individuals. This worldwide limit is split among five employment-based categories—the first three of which each receive 40,040 green cards, and the other two receive 9,940 each. (See Appendix A for more detailed category information.)

Apart from these numerical limits, the INA also imposes a 7% per-country cap or ceiling that applies to each of the five categories.2 The 7% ceiling is not an allocation to individual countries but an upper limit established to prevent the monopolization of employment-based green cards by a small number of countries. This percentage limit is breached frequently for the countries that send the largest number of prospective employment-based immigrants, due to reallocations from other categories and countries.

For nationals from most immigrant-sending countries, the employment-based backlog does not pose a major obstacle to obtaining a green card. Current wait times to receive a green card for those individuals are relatively short, often under a year. This is particularly the case for nationals from countries that send relatively few employment-based immigrants to the United States.

However, for nationals from India, and to a lesser extent China and the Philippines—three countries that send large numbers of foreign workers to the United States—the combination of the numerical limits and the 7% per-country ceiling has created inordinately long waits to receive employment-based green cards and exacerbated the backlog. New prospective immigrants currently entering the backlog (beneficiaries) are double the available number of green cards. Many Indian nationals can expect to wait decades to receive a green card. For some, the waits will exceed their lifetimes.

For these prospective immigrants, many of whom already reside in the United States, the backlog can impose significant hardships. Prospective employment-based immigrants who lack LPR status cannot switch jobs, potentially subjecting them to exploitative work conditions. While waiting in the United States, backlogged workers often develop community ties, purchase homes and have children. Yet with a petition pending approval3 and no green card, they cannot easily travel overseas to see their families, and their spouses may have difficulty obtaining legal permission to work.4 Any noncitizen children who reach age 21 before their parents acquire a green card risk aging out of legal status.5 In effect, a large part of these prospective immigrants' lives and those of their family members are on hold. If a prospective immigrant in the backlog dies while waiting for a green card, the individual's spouse and family lose their place in the queue, and in some cases their legal status to reside in the United States.6

For some U.S. employers, the backlog can act as a competitive disadvantage for attracting highly trained workers relative to other countries with more accessible systems for acquiring permanent residence. U.S. universities educate a sizable number of foreign-born graduates in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics,7 among other fields, many of whom may be desirable candidates to U.S. employers.8 In the face of the substantial wait times for LPR status, however, growing numbers of such workers are reportedly migrating to countries other than the United States for education, employment, or both.9

In recent years, some Members of Congress have proposed solutions for addressing the employment-based backlog, ranging from changing the existing system's numerical limits to restructuring the entire employment-based immigration system. The latter approach is widely viewed as legislatively and politically formidable. On the other hand, legislative proposals to alter the numerical limits—and to remove the per-country ceiling in particular—for employment-based immigrants have been introduced more regularly.

One proposal currently under consideration in the Senate following its passage in the House is the Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act (H.R. 1044; S. 386, as amended), which would eliminate the 7% per-country ceiling for employment-based immigration, among other provisions. Supporters of the bill assert that it would improve the current employment-based immigration system, initially by granting more green cards to Indian nationals who generally have longer wait times under the current system compared with nationals from other countries. Ultimately, the bill would convert the per-country system into what some consider a more equitable first-come, first served system. Supporters of this approach argue that the existing 7% per-country ceiling unfairly discriminates against foreign workers on the basis of their country of origin. They contend that the current backlog incentivizes some employers to hire and exploit Indian foreign workers, knowing that these workers will be unable to leave their jobs for many years without losing their place in the queue.10

Those opposed to removing the per-country ceiling maintain that it fulfills its original purpose of preventing a few countries from dominating employment-based immigration. They contend that removing the ceiling merely shuffles the deck by changing who receives employment-based green cards, benefiting Indian and Chinese nationals at the expense of immigrants from all other countries. Because Indian employment-based immigrants are employed largely in the information technology sector, such a change may benefit that sector at the expense of other industrial sectors that are also critical to the United States.11 Opponents argue that legislative proposals such as S. 386 do not address the more fundamental issue of too few employment-based green cards for an economy that has doubled in size since the law establishing their current statutory limits was passed in 1990.12

If the 7% per-country ceiling were eliminated, some observers expect that Indian and Chinese nationals would initially receive most or all employment-based green cards for some years at the expense of nationals from all other countries.13 Once current backlogs were eliminated, however, country of origin would no longer directly affect the allocation of employment-based green cards, an outcome that some consider more equitable to Indian and Chinese prospective immigrants, and that others consider disadvantageous to prospective immigrants from all other countries.

This report analyzes how removing the per-country ceiling would impact the employment-based immigrant backlog over the next decade, using the provisions of S. 386, as amended, as a case study. While certain provisions analyzed are specific to only this bill, the broader objective of eliminating the per-country ceiling has appeared in numerous legislative proposals in past Congresses. The report reviews the employment-based immigration system, discusses the key provisions of S. 386 affecting the backlog, and presents results from a Congressional Research Service (CRS) analysis that projects, under current conditions, how the backlog would change over the decade following enactment. The report ends with concluding observations and some potential legislative options.

Overview of the Permanent Employment-Based Immigration System

Each year, the United States grants LPR status to roughly 1 million foreign nationals,14 which allows them to live and work permanently in this country.15 The provisions that mandate LPR eligibility criteria—the pathways by which foreign nationals may acquire LPR status—and their annual numerical limits are established in the INA, found in Title 8 of the U.S. Code.

Among those granted LPR status are employment-based immigrants who serve the national interest by providing needed skills to the U.S. labor force.16 The INA specifies five preference categories of employment-based immigrants:

- 1. persons of extraordinary ability;

- 2. professionals with advanced degrees;

- 3. skilled and unskilled "shortage" workers for in-demand occupations (e.g., nursing);

- 4. assorted categories of "special immigrants"; and

- 5. immigrant investors (see Appendix A for more detail).

Each category has specific eligibility criteria, numerical limits, and, in some cases, application processes. The INA allocates 140,000 green cards annually for employment-based LPRs. In FY2018, employment-based LPRs accounted for about 13% of the almost 1.1 million LPRs admitted. The INA further limits each immigrant-sending country to an annual maximum of 7% of all employment-based LPR admissions, known as the 7% per-country ceiling.17 The ceiling serves as an upper limit for all countries, not a quota set aside for individual countries. As noted earlier, this percentage limit is breached frequently for the highest immigrant-sending countries, due to reallocations from other categories and countries.

The INA also contains provisions that allow countries to exceed the numerical limits set for each preference category and the per-country ceiling. First, unused green cards for each of the preference categories can roll down to be utilized in the next preference category.18 Second, in any given quarter, if the number of available green cards exceeds the number of applicants, the per-country ceiling does not apply for the remainder of green cards for that quarter.19 Third, any unused family-based preference immigrant green cards can be used for employment-based green cards in the next fiscal year.20

Such provisions regularly permit individuals from certain countries to receive far more employment-based green cards than the limits would imply. For example, the numerical limit for each of the first three employment-based categories is 40,040, which combined with the 7% per-country ceiling, would limit the annual number of green cards issued to Indian nationals to 2,803 per category. However, in FY2019, Indian nationals received 9,008 category 1 (EB1), 2,908 category 2 (EB2), and 5,083 category 3 (EB3) green cards.21

Among prospective immigrants, the INA distinguishes between principal prospective immigrants (principal beneficiaries), who meet the qualifications of the employment-based preference category, and derivative prospective immigrants (derivative beneficiaries), who include the principals' spouses and minor children. Derivatives appear on the same petition as principals and are entitled to the same status and order of consideration as long as they are accompanying or following to join principal immigrants.22 Both principals and derivatives count against the annual numerical limits, and currently less than half of employment-based green cards issued in any given year go to the principals.23

While some prospective employment-based immigrants can self-petition, most require U.S. employers to petition on their behalf. How prospective immigrants apply for employment-based LPR status depends on where they reside. If they live abroad, they may apply as new immigrant arrivals. If they reside in the United States, they may apply to adjust status from a temporary (nonimmigrant) status (e.g., H-1B skilled temporary worker, F-1 student) to LPR status.24

Employment-based immigration involves multiple steps and federal agencies. The Department of Labor (DOL) must initially provide labor certification for most preference category 2 and 3 immigrants.25 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) processes and adjudicates petitions for employment-based immigrants. USCIS assigns to each principal beneficiary and any derivative beneficiaries a priority date (the earlier of the labor certification or immigrant petition filing date), representing the prospective immigrant's place in the backlog. USCIS sends processed and approved immigrant petitions to the Department of State's (DOS's) National Visa Center, which allocates visa numbers or immigrant slots according to the INA's numerical limits and per-country ceilings. Individuals must wait for their priority date to become current before they can continue the process to receive a green card.26

Key Provisions of S. 386

The discussion below of S. 386, as amended, and the subsequent analysis are focused solely on the first three employment-based immigrant preference categories. These categories account for 120,120 or 86% of the 140,000 total employment-based green cards available annually. The EB4 category, which comprises special immigrants, and the EB5 category, which comprises immigrant investors, are statutorily included within the employment-based immigration system. Those categories, however, represent distinct types of immigrants that fall outside of S. 386's provisions, as well as much of the debate over the per-country ceiling.

The Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act (currently S. 386, as amended) has been introduced in Congress in different versions since 2011. In the 116th Congress, the bill was introduced in the House as H.R. 1044 by Representative Zoe Lofgren in February 2019 and was passed by the House on July 10, 2019, by a vote of 365 to 65. The bill was introduced in the Senate as S. 386 by Senator Mike Lee in February 2019. There have been negotiated proposed amendments since then, and the bill's provisions may change further.

In its current proposed form, S. 38627 contains the following provisions found in prior versions of the Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act:

- 1. Eliminating the per-country ceiling for employment-based immigrants;

- 2. Raising the per-country ceiling for family-based preference category immigrants from 7% to 15%; and

- 3. Allowing a three-year transition period for phasing out the employment-based per-country ceiling.

Eliminating the per-country ceiling for employment-based immigrants would convert the current system into a first-come, first-served system, with the earliest approved petitions receiving green cards before those filed subsequently, regardless of country of origin.

S. 386, as amended, also contains the following additional provisions intended to address issues and concerns raised by stakeholders:

- 1. A Hold Harmless provision that would ensure no person with a petition approved before enactment would have to wait longer for their visa as the result of the bill's passage;

- 2. Allocating up to 5.75% of the 40,040 EB2 and EB3 categories (2,302 per category) for derivative and principal immigrants applying from overseas, who otherwise would wait in the backlog much longer once the per-country ceiling was removed, either to reunite with their principal immigrant parents/spouses or to be employed in the United States;28 and

- 3. Within the EB3 category, allocating up to 4,400 of the 40,040 slots for Schedule A occupations (professional nurses and physical therapists).29 It would also allocate slots for these immigrants' accompanying family members.30

Analysis of the Employment-Based Backlog

The following analysis projects what the employment-based backlog would look like in 10 years under current law and compares that outcome with the projected outcome if S. 386 were passed. As noted above, the analysis is limited to the EB1, EB2, and EB3 categories, which together account for 120,120 (86%) of the 140,000 employment-based green cards permitted annually under the INA.

Analytical Approach

The projection of the impact of S. 386 assumes the bill is passed in FY2020, and its provisions take effect in FY2021. As such, the analysis begins with the FY2020 employment-based backlog for the EB1, EB2, and EB3 categories and projects how the bill's provisions alter these backlogs over the 10 years from FY2021 through FY2030. For each category, the analysis estimates the number of new prospective immigrants whose petitions would be approved each year (thereby added to the backlog), as well as the number of backlogged approved petition holders who would receive a green card each year (thereby removed from the backlog). Within each category, the analysis projects the resulting backlog for India, China, the Philippines (for EB3 only), and all other countries or the "rest of the world" (RoW).

Projected annual additions to the employment-based backlog in the analysis are based on FY2018 USCIS data on approved employment-based immigrant petitions. The analysis holds that number constant through the 10-year period examined.

Projected annual reductions to the employment-based backlog are based on green card issuances to approved petitioners and their derivatives. Because S. 386 does not increase the INA's annual worldwide limit of 140,000 green cards issued each year, annual green card issuances in the EB1, EB2, and EB3 categories sum to 40,040 under both scenarios. Projected issuances are based on current DOS data on the number of individuals, by country, who receive EB1, EB2, and EB3 green cards.

Under S. 386, issuances occur from overseas petitioners (the 5.75% set-aside), Schedule A petitioners (nursing and physical therapy occupations), and the remaining individuals with approved petitions according to their priority date or place in the queue. In the analysis, the Hold Harmless provisions alter issuances for FY2021 only, and the three-year Transition Year provisions impact issuances for FY2022 and FY2023.31 The 5.75% set-aside expires in nine years (FY2029), and the Schedule A set-aside expires in six years (FY2026). (For more detailed methodology information, see Appendix B.)

As such, the analysis that follows is an arithmetic exercise beginning with the current EB1, EB2, and EB3 approved petition backlogs, each broken out for India, China, the Philippines (only for EB3), and RoW. For each subsequent year, new petition approvals for prospective employment-based immigrants increase the backlog, and green card issuances to those individuals and their family members reduce the backlog. Because the INA treats derivative immigrants and principal immigrants equally for reaching the annual worldwide limit and maintaining the per-country ceiling, the analysis necessarily includes dependent family members of principal immigrants. Each year's ending backlog balance equals the following year's starting balance. The following sections describe the results of the analysis.

First Employment-Based Category (EB1)

Table 1 presents the projected change in the current EB1 backlog after 10 years, as well as current and projected green card wait times. All figures are estimates. Status quo projections are compared to those that model the impact of S. 386. All figures are estimates.

Table 1. Estimated Backlogs and Green Card Wait Times, EB1 Petition Holders

(Impacts under current law compared to S. 386, as of FY2020 and FY2030)

|

Under Current Law |

Under S. 386, as Amended |

|||||||

|

India |

China |

RoW |

Total |

India |

China |

RoW |

Total |

|

|

Projected Backlogs |

||||||||

|

FY2020 |

73,482 |

24,825 |

21,425 |

119,732 |

73,482 |

24,825 |

21,425 |

119,732 |

|

FY2030 |

160,324 |

78,267 |

29,655 |

268,246 |

88,913 |

53,481 |

125,852 |

268,246 |

|

% Change |

118% |

215% |

38% |

124% |

21% |

115% |

487% |

124% |

|

Projected Waiting Times to Receive a Green Card For Newly Approved Petition Holder (Years) |

||||||||

|

FY2020 |

8 |

5 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

|

FY2030 |

18 |

15 |

1 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

Source: Figures computed by CRS; see Appendix A for sources and methodology.

Notes: FY2020 refers specifically to the start of the fiscal year on October 1, 2019, and FY2030 refers to the start of the fiscal year on October 1, 2029. Wait times for a green card can also be interpreted as the number of years required for the EB1 backlog in FY2020 or FY2030 to be eliminated, either under current conditions or those that would be imposed by S. 386. RoW = rest of the world; EB1 = first employment-based category.

In both scenarios, total annual EB1 green cards issued and total new beneficiaries entering the EB1 queue are assumed to remain the same—a conservative assumption (see Figure 1, below). Since the number of new beneficiaries exceeds the number of green cards issued each year, the total backlog under both scenarios is projected to more than double from 119,732 in FY2020 to 268,246 in FY2030. S. 386 would alter how the backlog grows by country of origin over this period. For Indian nationals, the backlog would increase by only 21% under the bill's provisions, instead of 118% under current law. Chinese nationals would experience a 115% backlog increase, instead of a 215% increase. Nationals from all other countries would bear the impact of these reductions. Their backlog would increase by more than five times over this period, from 21,425 to 125,852.

Projected years to receive a green card for those waiting in the EB1 backlog reflect these shifts. Currently, backlogged EB1 Indian nationals can expect to wait up to eight years before receiving a green card. This also means that the current queue of 73,482 Indian nationals would require eight years to disappear. Under S. 386, this time would decrease to three years, and the number of years required to eliminate the backlog for Chinese nationals would decrease from five to three years. The backlog for RoW nationals would benefit from the Hold Harmless provisions in S. 386 and thus would disappear after one year under both scenarios. In FY2030, however, RoW nationals would experience projected wait times of seven years for a green card under S. 386, instead of one year under current law. In contrast, by FY2030, projected wait times for Indian and Chinese nationals would decline from 18 and 15 years, respectively, under current law, to seven years for each group.

Although rates of backlog increase and wait times diverge among country-of-origin groups, the common theme illustrated in Table 1 is the sizeable increase in the number of foreign workers and their dependents, largely residing in the United States, who would wait extended periods to obtain LPR status. Under this projection, the annual number of foreign workers sponsored for EB1 petitions continues to exceed (by an amount fixed at the FY2018 level) the number of statutorily mandated EB1 green cards.

Table 1 shows all EB1 foreign nationals in FY2030 facing the same seven-year wait to receive a green card. This demonstrates how eliminating the per-country ceiling under the provisions of S. 386 would convert the current employment-based system from one constrained by country-of-origin limits into one that functions on a first-come, first-served basis.

Second Employment-Based Category (EB2)

Table 2 presents projected changes to the current EB2 backlog after 10 years, as well as current and projected wait times for a green card. All figures are estimates. Projections are conducted for the status quo under current law and for if the current version of S. 386 were enacted. All figures are estimates.

Outcomes for the EB2 petition backlog would diverge considerably from those of the projected EB1 backlog because of the sizable difference between the current EB1 and EB2 backlogs. At 627,448 petitions, the current EB2 backlog is more than five times the size of the EB1 backlog (119,732 petitions) and is dominated overwhelmingly (91%) by Indian nationals. Chinese nationals make up the remaining 9% of the EB2 backlog. No EB2 backlog currently exists for nationals from any other country.

Total annual new beneficiaries entering the EB2 backlog and total EB2 green cards issued each year are the same under both scenarios. Since new entering beneficiaries always exceed green cards issued, the total backlog under either scenario is projected to more than double from 627,448 in FY2020 to 1,471,360 in FY2030. As with EB1 petitions, S. 386 would alter how the backlog grows by country of origin over this period. For Indian nationals, the backlog would increase by a smaller percentage—77% under the bill's provisions compared with 123% under current law. Chinese nationals, in contrast, would see their backlog increase by a greater percentage under the bill's provisions—217% versus 194% under current law. Nationals from all other countries, however, would experience the most notable difference in FY2030. Instead of a relatively small backlog of 30,051 that would disappear after a year under current law, RoW nationals would face a backlog nine times its current size (278,333).

Table 2. Estimated Backlogs and Green Card Wait Times, EB2 Petition Holders

(Impacts under current law compared to S. 386, as of FY2020 and FY2030)

|

Under Current Law |

Under S. 386, as Amended |

|||||||

|

India |

China |

RoW |

Total |

India |

China |

RoW |

Total |

|

|

Projected Backlogs |

||||||||

|

FY2020 |

568,414 |

59,034 |

0 |

627,448 |

568,414 |

59,034 |

0 |

627,448 |

|

FY2030 |

1,267,948 |

173,361 |

30,051 |

1,471,360 |

1,005,959 |

187,068 |

278,333 |

1,471,360 |

|

% Change |

123% |

194% |

n/a |

134% |

77% |

217% |

n/a |

134% |

|

Projected Waiting Times to Receive a Green Card For Newly Approved Petition Holder (Years) |

||||||||

|

FY2020 |

195 |

18 |

0 |

16 |

17 |

17 |

0 |

16 |

|

FY2030 |

436 |

51 |

1 |

37 |

37 |

37 |

37 |

37 |

Source: Figures computed by CRS; see Appendix A for sources and methodology.

Notes: FY2020 refers specifically to the start of the fiscal year on October 1, 2019, and FY2030 refers to the start of the fiscal year on October 1, 2029. Wait times for a green card can also be interpreted as the number of years required for the EB2 backlog in FY2020 or FY2030 to be eliminated, either under current conditions or those imposed by S. 386. n/a = not applicable; RoW = rest of the world; EB2 = second employment-based category.

The differential outcomes that S. 386 provides to Indian and Chinese nationals is also seen in the number of years they would have to wait for a green card by FY2030. Table 2 shows that under either scenario, green card wait times would increase for all groups in FY2030 compared to FY2020. Under current law, and owing to a limited number of green card issuances, the current backlog of 568,414 Indian nationals would require an estimated 195 years to disappear.32 By FY2030, this estimated wait time would more than double. Under S. 386, the estimated wait time for newly approved EB2 petition holders would shrink to 17 years, and in FY2030, the wait time would be 37 years, the same as for all other foreign nationals.

The significant drop in FY2030 green card wait times for Indian and Chinese nationals under S. 386 would come at the expense of nationals from all other countries. RoW nationals would see their EB2 backlog and wait times increase substantially. Currently, no backlog exists for persons with approved EB2 petitions from RoW countries. Under the current system, EB2 petition approval for anyone from other than India or China generally leads to a green card with no wait time.33 By removing the per-country ceiling, however, S. 386 would create a new RoW backlog by FY2030 that would be nine times its projected size under current conditions

Third Employment-Based Category (EB3)

Table 3 presents projected changes to the current EB3 backlog and green card wait times for both current law and following the potential enactment of S. 386. All figures are estimates. The EB3 analysis also includes projections for Filipino nationals, who represent relatively large numbers of foreign-trained nurses. As with the EB1 and EB2 categories, Indian nationals dominate the backlog, with 81% (137,161) of the total queue of 168,317 approved petitions. Chinese nationals represent 12% and Filipino nationals the remaining 7%. No backlog currently exists for nationals from all other countries.

The annual number of new beneficiaries entering the EB3 backlog and total EB3 green cards issued are the same each year under both scenarios, increasing almost all backlogs between FY2020 and FY2030. As with EB1 and EB2 petitions, S. 386 would alter how the backlog grows by country of origin over this period. For Indian nationals, the backlog is projected to decline by 8% under the bill's provisions compared with a 79% increase under current law. Chinese nationals, in contrast, would see almost no change in their backlog under the bill's provisions compared to current law. Filipino nationals would see a 25% increase in their relatively small backlog. RoW nationals would experience the most notable difference in FY2030, with the backlog increasing to roughly double the size under S. 386 (251,171) compared to the projected backlog under current law (136,783).

Table 3. Estimated Backlogs and Green Card Wait Times, EB3 Petition Holders

(Impacts under current law compared to S. 386, as of FY2020 and FY2030)

|

Under Current Law |

Under S. 386, as Amended |

|||||||||

|

India |

China |

Philip-pines |

RoW |

Total |

India |

China |

Philip-pines |

RoW |

Total |

|

|

Projected Backlogs |

||||||||||

|

FY2020 |

137,161 |

19,657 |

11,499 |

0 |

168,317 |

137,161 |

19,657 |

11,499 |

0 |

168,317 |

|

FY2030 |

244,907 |

64,387 |

10,113 |

136,783 |

456,190 |

126,494 |

64,169 |

14,381 |

251,171 |

456,190 |

|

% Change |

79% |

228% |

-12% |

n/a |

171% |

-8% |

226% |

25% |

n/a |

171% |

|

Projected Waiting Times to Receive a Green Card For Newly Approved Petition Holder (Years) |

||||||||||

|

FY2020 |

27 |

5 |

2 |

0 |

4 |

7 |

7 |

2 |

0 |

4 |

|

FY2030 |

48 |

17 |

2 |

5 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

Source: Figures computed by CRS; see Appendix A for sources and methodology.

Notes: FY2020 refers specifically to the start of the fiscal year on October 1, 2019, and FY2030 refers to the start of the fiscal year on October 1, 2029. Wait times for a green card can also be interpreted as the number of years required for the EB3 backlog in FY2020 or FY2030 to be eliminated, either under current conditions or those imposed by S. 386. n/a = not applicable; RoW = rest of the world; EB3 = third employment-based category.

Projected years to receive a green card for those waiting in the EB3 queue reflect these changes in backlog size. Currently, new Indian beneficiaries entering the EB3 backlog can expect to wait 27 years before receiving a green card. Under S. 386, this wait time would shorten to seven years, and the wait time for Chinese nationals would increase from five to seven years. For Filipino and RoW nationals, FY2020 wait times would not change. By FY2030, however, wait times under S. 386 would equalize the substantial differences in green card wait times under current law, with RoW nationals waiting an estimated 11 years to receive a green card.

Concluding Observations

This analysis projects the impact of eliminating the 7% per-country ceiling on the first three employment-based immigration categories over a 10-year period. It models outcomes under current law, as well as under the provisions of S. 386, as amended. The bill would phase out the per-country ceiling over three years and reserve green cards for certain foreign workers, among other provisions. S. 386 would not increase the total number of employment-based green cards, which equals 120,120 for the first three employment-based categories under current law.

The analyses of the EB1, EB2, and EB3 categories all project similar outcomes: Indian nationals, and to a lesser extent Chinese nationals, who are currently in the employment-based backlog would benefit from shorter waiting times under S. 386 compared with current law. The bill would eliminate all current EB1, EB2, and EB3 backlogs in 3, 17, and 7 years, respectively, with some modest differences by country of origin. Once current backlogs are eliminated under the Hold Harmless provision of S. 386, persons with approved employment-based petitions would receive green cards on a first-come, first-served basis, with equal wait times within each category, regardless of country of origin. In FY2030, foreign nationals with approved EB1, EB2, and EB3 petitions could expect to wait 7, 37, and 11 years, respectively, regardless of country of origin. By contrast, maintaining the 7% per-country ceiling would, over 10 years, substantially increase the long wait times to receive a green card for Indian and Chinese nationals, but it would also continue to allow nationals from all other countries to receive their green cards relatively quickly.

S. 386 would not alter the growth of future backlogs compared to current law. This analysis projects that, by FY2030, the EB1 backlog would grow from an estimated 119,732 individuals to an estimated 268,246 individuals; the EB2 backlog, from 627,448 individuals to 1,471,360 individuals; and the EB3 backlog, from 168,317 individuals to 456,190 individuals. In sum, the total backlog for all three employment-based categories would increase from an estimated 915,497 individuals currently to an estimated 2,195,795 by FY2030. If the current number of new beneficiaries each year continues, these outcomes would occur whether or not S. 386 is enacted, as the bill contains no provisions to change the number of green cards issued.

As noted throughout this report, all figures from this analysis are estimates. They are based largely on the assumption that current immigration flows—of newly approved employment-based immigrant petitions added to the backlog and of employment-based green card issuances by country of origin removed from the backlog—remain constant over 10 years. As such, results from the analysis are subject to change, depending on how numbers of future petition approvals and green card issuances deviate from current levels.

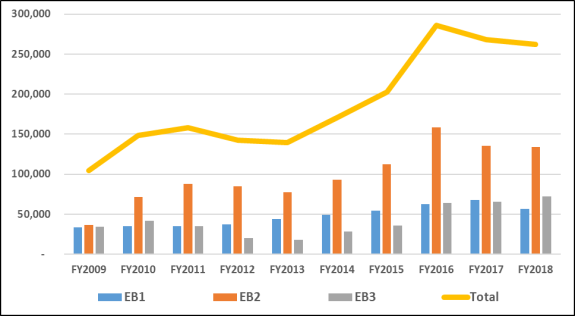

In one respect, the analysis yields conservative estimates—it assumes that the number of new beneficiaries entering the employment-based immigration system will remain at their FY2018 levels. USCIS data for the past decade, however, show a consistent upward trend in the number of approved I-140 employment-based immigrant petitions (Figure 1).34 Regarding green card issuances, the analysis is not subject to future variation because under current law or the provisions of S. 386, the number of employment-based green cards issued each year remains fixed by statute. In FY2018, the former exceeded 262,000, while the latter remained at 120,120.

The number of employment-based immigrants who are sponsored by U.S. employers and who enter the immigration pipeline with the aspiration of acquiring U.S. lawful permanent residence far exceeds the number of LPR slots available to them. Removing the 7% per-country ceiling would initially reduce wait times considerably for Indian and Chinese nationals in the years following enactment of S. 386, but it would do so at the expense of nationals from all other countries, as well as of the enterprises in which the latter are employed. In a decade, wait times would equalize among all nationals within each category, regardless of country of origin. This outcome may appear more equitable to some because prospective immigrants from all countries would have to wait the same period to receive a green card. However, it may appear less equitable to others because it would make backlog-related waiting times apply to nationals from all countries rather than just nationals from a few prominent immigrant-sending countries. S. 386 would not address the imbalance between the number of foreign nationals who enter the employment-based pipeline and the number who emerge with LPR status.

Legislative Options

Four options Congress could consider related to the current employment-based immigration backlog include maintaining current law by leaving the 7% per-country cap as is; removing the 7% per-country cap for employment-based immigrants as is proposed under S. 386; increasing the number of employment-based LPRs permitted under the current system; or reducing the number of prospective immigrants entering the employment-based pipeline. These options are not necessarily mutually exclusive and could be considered in combination with others. Some Members of Congress have also introduced legislation that would offer more substantial structural changes to the employment-based system.

Maintain Current Law. Supporters of the per-country ceiling cite the current law's original purpose of this provision: to prevent nationals from a few countries from monopolizing the limited number of employment-based green cards. This 7% threshold allows prospective immigrants from other countries to acquire LPR status in a relatively short time, diversifying the skilled pool of workers from which U.S. employers may draw. To the extent that prospective immigrants from high immigrant-sending countries such as India and China concentrate in particular industrial sectors, the per-country ceiling imposes constraints on some industries and allows others to access that worker pool.35 Because Indian nationals, in particular, have entered the employment-based backlog in relatively large numbers over the past two decades, they experience the most pronounced impact of the per-country ceiling. Some Indian nationals currently wait for decades to receive green cards—and in the case of new EB2 petition holders, centuries. Some Indian nationals consider this provision of the law discriminatory and unfair.36

Remove Annual Per-Country Ceiling for Employment-Based Immigrants. Supporters of removing the per-country ceiling emphasize the inordinately long wait times which, as shown above, require Indian nationals who enter the employment-based backlog to wait an estimated 8, 195, and 27 years, respectively, for green cards in the EB1, EB2, and EB3 categories. This analysis estimates that, holding current conditions constant, these wait times could increase to 18, 436, and 48 years, respectively, by FY2030. Long wait times call into question the legitimate functioning of the employment-based pathway to lawful permanent residence when large numbers of current and prospective backlogged workers remain in temporary status most, if not all, of their working lives. Opponents of removing the per-country ceiling maintain that it currently functions as intended. They point to the concentration of Indian and Chinese nationals in the U.S. information technology sector and argue that prospective employment-based immigrants from other countries benefit far more segments of the U.S. economy.

Increase Number of Employment-Based LPRs under Current System. The number of green cards for employment-based immigrants could be increased by altering current numerical limits for specific categories or the total worldwide limit. Some have proposed exempting accompanying family members to achieve this goal. Other proposals would increase employment-based immigrants in exchange for reducing the number of other immigrant types, such as family-based preference or diversity immigrants.37 Such legislation would alleviate current and future employment-based backlogs more expediently than under the current system. Supporters of expanding the number of green cards point out that the current limit of 140,000 for all five employment-based preference categories (120,120 for the first three) was established 30 years ago when the U.S. economy was half its current size.38 They contend that the larger U.S. economy and the shifting economic importance of technological innovation reinforces the need to find the "best and brightest" workers, including from overseas, who can contribute to U.S. economic growth. Opponents of increasing the number of employment-based green cards point to the lack of evidence indicating labor shortages in technology sectors.39 They contend that the green card backlog harms U.S. workers by forcing them to compete in some industries with foreign workers who may accept more onerous working conditions and lower wages in exchange for LPR status. Some also argue that current immigration levels are too high. Legislation increasing the number of green cards may face resistance from the Trump Administration and some Members of Congress who oppose increasing immigration levels.

Reduce Number of Prospective Immigrants Entering Employment-Based Pipeline.40 A primary pathway to acquire an employment-based green card is by working in the United States on an H-1B visa for specialty occupation workers, getting sponsored for a green card by a U.S. employer, and then adjusting status when a green card becomes available.41 When first established in 1990, the H-1B program was limited to 65,000 visas per year. Current limits have since been expanded by excluding H-1B visa renewals and H-1B visa holders employed by nonprofit organizations and institutions of higher education, as well as 20,000 aliens holding a master's or higher degree (from a U.S. institution of higher education). In FY2019, for example, 188,123 individuals received or renewed an H-1B visa, far more than the original 65,000 annual limit.42 Although some other nonimmigrant visas allow foreign nationals to work in the United States, the INA permits only H-1B and L visa holders to be "intending immigrants" who can then renew their status indefinitely while waiting to adjust to LPR status.43 Eliminating this "dual intent" classification or otherwise reducing the number of prospective immigrants entering the employment-based backlog would reduce the growth of the backlog and shorten wait times. Arguments against reducing skilled migration emphasize the impacts on economic growth in certain industrial sectors.44

Reform Structure of Employment-Based Immigration System. Some recent legislative proposals have taken broader approaches toward restructuring the employment-based immigration system. The Trump Administration and some Members of Congress have proposed changing the current system from one that relies on employer sponsorship to a merit-based system that would rank and admit potential immigrants based on labor market attributes and expected contributions to the U.S. economy.45 Other Members of Congress have introduced proposals establishing place-based immigration systems that would let each state determine the number and type of temporary workers it needs.46 All of these approaches exceed the scope of the more narrow discussion of the numerical and per-country limits addressed in this analysis.

Appendix A. Employment-Based Preference Categories

Within permanent employment-based immigration, the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) outlines five distinct employment-based preference categories. Each of the five categories is constrained by its own eligibility requirements and numerical limit (Table A-1).

|

Preference Category |

Eligibility Criteria |

Numerical Limit |

|

1: "Priority workers" |

Priority workers: persons of extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics; outstanding professors and researchers; and certain multinational executives and managers |

28.6% of worldwide limit (40,040), plus unused fourth and fifth preferences |

|

2: "Members of the professions holding advanced degrees or aliens of exceptional ability" |

Members of the professions holding advanced degrees or persons of exceptional abilities in the sciences, arts, or business |

28.6% of worldwide limit (40,040), plus unused first preference |

|

3: |

Skilled shortage workers with at least two years training or experience; professionals with baccalaureate degrees; and unskilled shortage workers |

28.6% of worldwide limit (40,040), plus unused first or second preference; unskilled "other workers" limited to 10,000 |

|

4: |

"Special immigrants" including ministers of religion, religious workers, certain employees of the U.S. government abroad, and others |

7.1% of worldwide limit (9,940); religious workers limited to 5,000 |

|

5: |

Immigrant investors who invest at least $1.8 million ($900,000 in rural areas or areas of high unemployment) in a new commercial enterprise that creates at least 10 new jobs |

7.1% of worldwide limit (9,940); 3,000 minimum reserved for investors in rural or high unemployment areas |

Source: CRS summary of Immigration and Nationality Act §203(b); 8 U.S.C. §1153(b).

Note: Employment-based allocations are further affected by the Nicaraguan and Central American Relief Act (NACARA; Title II of P.L. 105-100), as amended by §1(e) of P.L. 105-139. NACARA provides immigration benefits and relief from deportation to certain Nicaraguans, Cubans, Salvadorans, Guatemalans, and nationals of former Soviet bloc countries, as well as their dependents who arrived in the United States seeking asylum. Employment-based allocations also are affected by the Chinese Student Protection Act (P.L. 102-404), which requires that the annual limit for China be reduced by 1,000 until such accumulated allotment equals the number of aliens (roughly 54,000) acquiring immigration relief under the act. Consequently, each year, 300 immigrant visa numbers are deducted from the third preference category and 700 from the fifth preference category for China. See U.S. Department of State, Visa Office, Annual Numerical Limits for Fiscal Year 2018.

Appendix B. Methodological Notes

The results presented in this report are based on an arithmetic projection of the employment-based backlog under current law and under the provisions of S. 386, as amended. Each element of the projection is described below.

Current Backlog Balance. The current backlog balance consists of individuals who possess approved employment-based petitions47 and who are waiting for a statutorily limited green card.48 For this analysis, CRS obtained unpublished data from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) indicating, for each of the countries within the three employment-based categories analyzed herein, the number of people with approved I-140 petitions.49 The USCIS data are further broken down by year of priority date, indicating the numerical order in which approved petitions in the backlog are to receive green cards.

New Petition Approvals. To estimate newly approved petitions of prospective employment-based immigrants, the analysis relies on unpublished USCIS figures of EB1, EB2, and EB3 petitions approved in FY2018.50 The figures are further divided by country, for India and China only. These figures include only principal immigrants and do not account for derivative immigrant family members who accompany or follow to join the principal immigrants and who are included within the same statutory numerical limits. Derivative immigrants are estimated by multiplying the number of principal immigrants by the average derivative-to-principal immigrant ratios (derivative multipliers).51

Hold Harmless Issuances. As noted above, S. 386 contains a provision ensuring that no one holding an approved petition waits additional time in the backlog as the result of the bill's passage. This provision applies to EB1, EB2, and EB3 categories. To approximate the Hold Harmless provision's impact, this analysis assumes that requirements for this provision would be met with one year's worth of issuances under current law, or current issuances, as recorded by the most recent FY2019 U.S. Department of State (DOS) annual visa report.52

Overseas Petitioner Issuances. As noted above, S. 386 contains a provision that would reserve up to 5.75% (2,302) of the 40,040 EB2 and EB3 green cards for foreign nationals petitioning from overseas. Most prospective employment-based immigrants in the backlog already reside in the United States. When notified by DOS that a visa number is available for them, they can apply with USCIS to adjust status from a nonimmigrant status (e.g., possessing an H-1B visa) to LPR status. However, some backlogged prospective immigrants reside abroad in their home countries. Employers seeking to hire these individuals face a competitive disadvantage because they are not already employing them. Individuals based overseas who face long wait times are likely to advance their careers elsewhere rather than wait abroad for years to receive an employment-based green card in the United States. This analysis assumes that green cards reserved under this provision would be used mostly by RoW country nationals who currently face no wait times.

Schedule A Issuances. S. 386 contains a provision that would reserve up to 4,400 green cards for Schedule A occupations (professional nurses and physical therapists).53 Under the most recent version of the bill, this set-aside would last for six years following enactment. The set-aside includes 4,400 principal immigrants, as well as their family members, effectively doubling the provision's impact. To estimate the number of family members, the analysis assumes that Schedule A principal immigrants brought with them an average of 1.06 derivative immigrants. As such, the total set-aside under this provision is 4,400 principal immigrants plus 4,664 derivative immigrants, for a total set-aside of 9,064 immigrants. Because of the Hold Harmless provisions, Schedule A issuances are projected to start in Year 2 of the analysis (FY2022). Issuances are distributed between nationals from the Philippines, which send the majority of foreign-trained immigrant nurses to the United States, and nationals from all other countries.54

Transition Year Issuances. S. 386 contains provisions that would allow a transition from the current 7% per-country ceiling to its elimination in the first three years following enactment. The transition would affect issuances in the first three years following enactment.

Table B-1. Transition Year Green Card Issuances Under S. 386

(eliminating the 7% per-country ceiling over the first three years)

|

Year |

Major Immigrant-Sending Countries |

Rest of the World (RoW) Countries |

|

FY2021 |

85% of total annual green card issuances (34,034) are split between the two countries with the most employment-based (EB) immigrants; of these, not more than 85% (28,929) can go to the first country. The remainder, at least 15% (5,105), go to the second country. |

15% of total annual green card issuances (6,006) are reserved for RoW countries; among these, not more than 25% can go to a single state. |

|

FY2022 |

90% of total annual green card issuances (36,036) are split between the two countries with the most EB immigrants; of these, not more than 85% (30,631) can go to the first country. The remainder, at least 15% (5,405), go to the second country. |

10% of total annual green card issuances (4,004) are reserved for RoW countries; among these, not more than 25% can go to a single state. |

|

FY2023 |

90% of total annual green card issuances (36,036) are split between the two countries with the most EB immigrants; of these, not more than 85% (30,631) can go to the first country. The remainder, at least 15% (5,405), go to the second country. |

10% of total annual green card issuances (4,004) are reserved for RoW countries; among these, not more than 25% can go to a single state. |

Source: Section 2(c) of S. 386, as amended.

Note: The Transition Year provisions apply only to the EB2 and EB3 preference categories. First country refers to Indian nationals who currently make up the largest number of employment-based prospective immigrants in the EB1, EB2, and EB3 backlogs, and second country refers to Chinese nationals who make up the second largest number.

Because all of the issuance provisions described above overlap during the first few years, this analysis gives precedence to the Hold Harmless, Overseas Petition, and Schedule A issuances over the Transition Year issuances. Consequently the 40,040 green cards allocated by S. 386 to the EB1, EB2, and EB3 categories according to Table B-1 are first reduced by the Overseas Petition and Schedule A issuances before being allocated according to the Transition Year provisions. In addition, Year 1 (FY2021) Transition Year issuance limits are preempted by the higher priority Hold Harmless issuances for that year.

Backlog Reduction Methodology. Backlogged employment-based petition holders are issued green cards in the analysis according to the year in which they entered the backlog. Although the issuance limits described above quantify the number of issuances for each country in each of the three employment-based preference categories, the elimination of the current existing backlog is based on how many backlogged petitions can be processed within annual green card limits and on which country's nationals have the oldest petitions.

In FY2018, USCIS approved 22,799 EB1, 66,904 EB2, and 34,964 EB3 petitions, per the November 2019 report cited above. Factoring in family members using the derivative multipliers for each EB category described above—1.48 for EB1, 1.00 for EB2, and 1.06 for EB3—yields an estimated 56,542 new additions to the EB1 backlog, 133,808 new additions to the EB2 backlog, and 72,026 new additions to the EB3 backlog. Given that 40,040 statutorily mandated green cards can reduce these backlogs each year, the net result is an estimated increase in the EB1, EB2, and EB3 backlogs each year by 16,502, 93,768, and 31,986 petitions, respectively (i.e., approved principal immigrant green card petitions, increased by their dependents and reduced by green card issuances).

As a result, the estimated total EB1 backlog at the start of FY2020 of 119,732 (Table 1) increases by a projected 148,518 individuals over nine years (16,502 x 9), resulting in an estimated EB1 backlog at the start of FY2030 of 268,260.55 The estimated total EB2 backlog at the start of FY2020 of 627,448 (Table 2) increases by a projected 843,912 individuals over nine years (93,768 x 9), resulting in an estimated EB2 backlog at the start of FY2030 of 1,471,360. The estimated total EB3 backlog at the start of FY2020 of 168,317 (Table 3) increases by a projected 287,874 individuals over nine years (31,986 x 9), resulting in an estimated EB3 backlog at the start of FY2030 of 456,191.56

These totals are further broken down in the analysis by the provisions of S. 386 that allocate the 40,040 annual green card issuances according to the provisions described above. Those provisions alter the number of green cards that nationals from individual countries would otherwise receive under current law. The overall projected impact on the total backlog remains the same whether or not S. 386 is enacted.