Purposes, Authority, and Participants

Throughout its history, Congress has engaged in oversight—broadly defined as reviewing, monitoring, and supervising the implementation of public policy by the executive branch. Investigating how a statute is being administered enables Congress to assess whether federal agencies and departments are administering programs in an effective, efficient, and economical manner. The expansion of the national government's size and scope has only increased Congress's need for and use of available oversight tools to check on and check the executive. The "checking" function serves to protect Congress's policymaking role and its place under Article I in the U.S. constitutional system of checks and balances.1

Congress's oversight role is also significant because it shines the spotlight of public attention on many critical issues, which enables lawmakers and the general public to make informed judgments about executive performance. Woodrow Wilson, in his classic 1885 study Congressional Government, emphasized that the "informing function should be preferred even to its [lawmaking] function." He added that unless Congress conducts oversight of administrative activities, the "country must remain in embarrassing, crippling ignorance of the very affairs which it is most important it should understand and direct."2

Congress's authority to conduct oversight comes from four overlapping sources: the Constitution, Supreme Court decisions, laws, and House and Senate rules. First, oversight is an implicit constitutional responsibility of Congress. According to historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr., the Framers believed "it was not considered necessary to make an explicit grant of such authority. The power to make laws implied the power to see whether they were faithfully executed."3

Second, the investigative authority of Congress is broad and bolstered by an array of Supreme Court decisions. For example, in Watkins v. United States,4 the Court stated that the "power of Congress to conduct investigations is inherent in the legislative process. That power is broad. It encompasses inquiries concerning the administration of existing laws as well as proposed or possibly needed laws." There are limits to Congress's power to investigate, such as the Constitution (e.g., the protection accorded witnesses under the Fifth Amendment against self-incrimination).

Third, there are numerous laws that provide Congress with the authority to conduct oversight. Despite its lengthy heritage, oversight was not given explicit recognition in public law until enactment of the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946.5 That act required House and Senate standing committees to exercise "continuous watchfulness" over programs and agencies within their jurisdiction.

Fourth, the House and Senate have often amended their formal rules to encourage and strengthen committee oversight of the administration of laws. For example, House rules direct committees to create oversight subcommittees, undertake futures research and forecasting, and review the impact of tax expenditures within their respective jurisdictions. Senate rules require each standing committee to include regulatory impact statements in committee reports accompanying legislation.

Oversight occurs in virtually any congressional activity and through a wide variety of channels, organizations, and structures. These range from formal committee hearings to informal Member contacts with executive officials, from staff studies to reviews by congressional support agencies, and from casework conducted by Member offices to studies prepared by non-congressional entities, such as academic institutions, private commissions, or think tanks.

Purposes

Congressional oversight of the executive is designed to fulfill a variety of purposes, such as those outlined below.

Ensure Executive Compliance with Legislative Intent

Congress, of necessity, must delegate discretionary authority to federal administrators. To make certain that these officers faithfully execute laws according to the intent of Congress, committees and Members can review the actions taken and regulations formulated by departments and agencies.

Improve the Efficiency, Effectiveness, and Economy of Governmental Operations

A large federal bureaucracy makes it imperative for Congress to encourage and secure efficient and effective program management and to make every dollar count toward the achievement of program goals. A basic objective is strengthening federal programs through better managerial operations and service delivery. Such steps can improve the accountability of agency managers to Congress and enhance program performance.

Evaluate Program Performance

Systematic program performance evaluation remains an evolving technique of oversight. Modern program evaluation uses social science and management methodologies—such as surveys, cost-benefit analyses, and efficiency studies—to assess the effectiveness of ongoing programs.

Prevent Executive Encroachment on Legislative Prerogatives and Powers

Many commentators, public policy analysts, and legislators state that Presidents and executive officials may overstep their authority in various areas, such as the impoundment of funds, executive privilege, and war powers. Increased oversight—as part of the constitutional checks and balances system—can redress what many in the public and Congress might view as executive arrogation of legislative prerogatives.

Investigate Alleged Instances of Poor Administration, Arbitrary and Capricious Behavior, Abuse, Waste, Dishonesty, and Fraud

Instances of fraud and other forms of corruption, wasteful expenditures, incompetent management, and the subversion of governmental processes can provoke legislative and public interest in oversight.

Assess Agency or Officials' Ability to Manage and Implement Program Objectives

Congress's ability to evaluate the capacity of agencies and managers to carry out program objectives can be accomplished in various ways. For example, numerous laws require agencies to submit reports to Congress. Some of these are regular, occurring annually or semi-annually, for instance, while others are activated by a specific event, development, or set of conditions. Reporting requirements may promote self-evaluation by the agency. Organizations outside of Congress—such as offices of inspector general, the Government Accountability Office (GAO), and study commissions—also advise Members and committees on how well federal agencies are working.

Review and Determine Federal Financial Priorities

Congress exercises some of its most effective oversight through the appropriations process, which provides the opportunity to assess agency and departmental expenditures in detail. In addition, most federal agencies and programs are under regular and frequent reauthorizations—on an annual, two-year, five-year, or other basis—giving authorizing committees the opportunity to review agency activities, operations, and procedures. As a consequence of these oversight efforts, Congress can abolish or curtail obsolete or ineffective programs by cutting off or reducing funds. Congress might also increase funding for effective programs.

Ensure That Executive Policies Reflect the Public Interest

Congressional oversight can appraise whether the needs and interests of the public are adequately served by federal programs. Such evaluations might prompt corrective action through legislation, administrative changes, or other means and methods. Legislative reviews might also prompt measures to consolidate or terminate duplicative and unnecessary programs or agencies.

Protect Individual Rights and Liberties

Congressional oversight can help safeguard the rights and liberties of citizens and others. By revealing abuses of authority, oversight hearings and other efforts can halt executive misconduct and help prevent its recurrence through, for example, new legislation or indirectly by heightening public awareness of the issue(s).

Other Purposes

The purposes of oversight—and what activities are illustrative of this function—can also be stated in more precise terms. Like the general purposes noted above, these more specific purposes unavoidably overlap because of the numerous and multifaceted dimensions of oversight. A brief list includes the following:

- review the agency rulemaking process,

- monitor the use of contractors and consultants for government services,

- encourage and promote mutual cooperation between the branches,

- examine agency personnel procedures,

- acquire information useful in future policymaking,

- investigate constituent complaints and media critiques,

- assess whether program design and execution maximize the delivery of services to beneficiaries,

- compare the effectiveness of one program with another,

- protect agencies and programs against unjustified criticisms, and

- appraise federal evaluation activities.

|

Thoughts on Oversight and Its Rationales from... James Wilson (The Works of James Wilson, 1896, vol. II, p. 29), an architect of the Constitution and Associate Justice on the first Supreme Court: The House of Representatives … form the grand inquest of the state. They will diligently inquire into grievances, arising both from men and things. Woodrow Wilson (Congressional Government, 1885, p. 297), perhaps the first scholar to use the term oversight to refer to the review and investigation of the executive branch: Quite as important as legislation is vigilant oversight of administration. It is the proper duty of a representative body to look diligently into every affair of government and to talk much about what it sees. It is meant to be the eyes and the voice, and to embody the wisdom and will of its constituents. The informing function of Congress should be preferred even to its legislative function. John Stuart Mill (Considerations on Representative Government, 1861, p. 104), British utilitarian philosopher: [T]he proper office of a representative assembly is to watch and control the government; to throw the light of publicity on its acts; to compel a full exposition and justification of all of them which any one considers questionable. |

Authority to Conduct Oversight

U.S. Constitution

The Constitution grants Congress extensive authority to oversee and investigate executive branch activities. The constitutional authority for Congress to conduct oversight stems from such explicit and implicit provisions as

- The power of the purse. The Constitution provides: "No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law."6 Each year the House and Senate Committees on Appropriations review the financial practices and needs of federal agencies. The appropriations process allows Congress to exercise extensive control over the activities of executive agencies. Congress can define the precise purposes for which money may be spent, adjust funding levels, and prohibit expenditures for certain purposes.

- The power to organize the executive branch. Congress has the authority to create, abolish, reorganize, and fund federal departments and agencies. It has the authority to assign or reassign functions to departments and agencies and grant new forms of authority and staff to administrators. Congress, in short, exercises ultimate authority over executive branch organization and generally over policy.7

- The power to make all laws for "carrying into Execution" Congress's own enumerated powers as well as those of the executive. Article I grants Congress a wide range of powers, such as the power to tax and coin money, regulate foreign and interstate commerce, declare war, provide for the creation and maintenance of armed forces, and establish post offices.8 Augmenting these specific powers is the Necessary and Proper Clause, also known as the "Elastic Clause," which gives Congress the authority to "make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof."9 These provisions grant broad authority to regulate and oversee departmental activities established by law.

- The power to confirm officers of the United States. The confirmation process not only involves the determination of a nominee's suitability for an executive (or judicial) position but also provides an opportunity to examine the current policies and programs of an agency along with those policies and programs that the nominee intends to pursue.10

- The power of investigation and inquiry. A traditional method of exercising the oversight function, an implied power, is through investigations and inquiries into executive branch operations. Legislators often seek to know how effectively and efficiently programs are working, how well agency officials are responding to legislative directives, and how the public perceives the programs. The investigatory method helps to ensure a more responsible bureaucracy while supplying Congress with information needed to formulate new legislation.

- Impeachment and removal. Impeachment provides Congress with a powerful, ultimate oversight tool to investigate alleged executive and judicial misbehavior and to eliminate such misbehavior through the convictions and removal from office of the offending individuals.11

|

The Supreme Court on Congress's Power to Oversee and Investigate McGrain v. Daugherty, 273 U.S. 135, 177, 181-182 (1927): Congress, investigating the administration of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) during the Teapot Dome scandal, was considering a subject "on which legislation could be had or would be materially aided by the information which the investigation was calculated to elicit." The "potential" for legislation was sufficient. The majority added, "We are of [the] opinion that the power of inquiry—with process to enforce it—is an essential and appropriate auxiliary to the legislative function." Eastland v. United States Servicemen's Fund, 421 U.S. 491, 509 (1975): Expanding on its holding in McGrain, the Court declared, "To be a valid legislative inquiry there need be no predictable end result." |

Principal Statutory Authority: Illustrative Examples

Direct Expansions of Congress's Oversight Power

A number of laws directly augment and safeguard Congress's authority, mandate, and resources to conduct oversight and legislative investigations. For example, there are pertinent statutes that affect congressional proceedings, such as obstruction (18 U.S.C. §1505), false statements by witnesses (18 U.S.C. §1001(c)(2)), and contempt procedures (2 U.S.C. §§192, 194). Among several other noteworthy laws, listed chronologically, are the following:12

- 1912 anti-gag legislation and whistleblower protection laws for federal employees:

- The Lloyd-La Follettee Act of 1912 (5 U.S.C. §7211) countered executive orders, issued by Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, that prohibited civil service employees from communicating directly with Congress. It also guaranteed that "the right of any persons employed in the civil service … to petition Congress, or any Member thereof, or to furnish information to either House of Congress, or to any committee or member thereof, shall not be denied or interfered with."

- The Whistleblower Protection Act of 1989 (P.L. 101-12, 5 U.S.C. ch. 12) makes it a prohibited personnel practice for an agency employee to take (or not take) any action against an employee that is in retaliation for disclosure of information that the employee believes relates to violation of law, rule, or regulation or evidences gross mismanagement, waste, fraud, or abuse of authority (5 U.S.C. §2302(b)(8)). The prohibition is explicitly intended to protect disclosures to Congress: "This subsection shall not be construed to authorize the withholding of information from Congress or the taking of any personnel action against an employee who discloses information to Congress."

- The Intelligence Community Whistleblower Protection Act (P.L. 105-272) establishes special procedures for personnel in the Intelligence Community to transmit urgent concerns involving classified information to inspectors general and the House and Senate Select Committees on Intelligence.

- Section 714 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2010 (P.L. 111-117) prohibits the payment of the salary of any officer or employee of the federal government who prohibits, prevents, attempts, or threatens to prohibit or prevent any other federal officer or employee from having direct oral or written communication or contact with any Member, committee, or subcommittee. This prohibition applies irrespective of whether such communication was initiated by such officer or employee or in response to the request or inquiry of such Member, committee, or subcommittee. Further, any punishment or threat of punishment because of any contact or communication by an officer or employee with a Member, committee, or subcommittee is prohibited under the provisions of this act.

- Section 716 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2010 (P.L. 111-117) prohibits the expenditure of any appropriated funds for use in implementing or enforcing agreement in Standard Forms 312 and 4414 of the government or any other non-disclosure policy, form, or agreement if such policy, form, or agreement does not contain a provision that states that the restrictions are consistent with and do not supersede, conflict with, or otherwise alter the employee obligation, rights, and liabilities created by Executive Order 12958;13 the Lloyd-La Follette Act (5 U.S.C. §7211); the Military Whistleblower Act (10 U.S.C. §1034); the Whistleblower Protection Act (5 U.S.C. §2303(b)(8)); the Intelligence Identities Protection Act (50 U.S.C. §421 et seq.); and United States Code Title 18, Sections 641, 793, 794, 798, and 952 and Title 50, Section 783(b).

- Budget and Accounting Act of 1921 (P.L. 67-13) establishing GAO

- Stated that GAO "shall be independent of the executive departments and under the control and direction of the Comptroller General of the United States."

- Granted authority to the comptroller general to "investigate, at the seat of government or elsewhere, all matters relating to the receipt, disbursement, and application of public funds."

- Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946 (P.L. 79-600):

- Mandated House and Senate committees to exercise "continuous watchfulness" of the administration of laws and programs under their jurisdiction.

- Authorized, for the first time in history, permanent professional and clerical staff for committees.

- Authorized and directed the comptroller general to make administrative management analyses of each executive branch agency.

- Established the Legislative Reference Service, renamed the Congressional Research Service by the 1970 Legislative Reorganization Act (see below), as a separate department in the Library of Congress and called upon the service "to advise and assist any committee of either House or joint committee in the analysis, appraisal, and evaluation of any legislative proposal … and otherwise to assist in furnishing a basis for the proper determination of measures before the committee."

- Intergovernmental Cooperation Act of 1968 (P.L. 90-577):

- Required that House and Senate committees having jurisdiction over grants-in-aid conduct studies of the programs under which grants-in-aid are made.

- Provided that studies of these programs are to determine whether (1) their purposes have been met, (2) their objectives could be carried on without further assistance, (3) they are adequate to meet needs, and (4) any changes in programs or procedures should be made.

- Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970 (P.L. 91-510):

- Revised and rephrased in more explicit language the oversight function of House and Senate standing committees: "each standing committee shall review and study, on a continuing basis, the application, administration, and execution of those laws or parts of laws, the subject matter of which is within the jurisdiction of that committee."

- Required most House and Senate committees to issue biennial oversight reports.

- Strengthened the program evaluation responsibilities and other authorities and duties of the GAO.

- Re-designated the Legislative Reference Service as the Congressional Research Service, strengthening its policy analysis role and expanding its other responsibilities to Congress.

- Recommended that House and Senate committees ascertain whether programs within their jurisdiction could be appropriated for annually.

- Required most House and Senate committees to include in their committee reports on legislation five-year cost estimates for carrying out the proposed program.

- Increased by two the number of permanent staff for each standing committee, including provisions for minority party hirings, and provided for hiring of consultants by standing committees.

- Federal Advisory Committee Act of 1972 (P.L. 92-463):

- Directed House and Senate committees to make a continuing review of the activities of each advisory committee under its jurisdiction.

- The studies are to determine whether (1) such committee should be abolished or merged with any other advisory committee, (2) its responsibility should be revised, and (3) it performs a necessary function not already being performed.14

- Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974 (P.L. 93-344):

- Expanded House and Senate committee authority for oversight. Permitted committees to appraise and evaluate programs themselves "or by contract, or (to) require a Government agency to do so and furnish a report thereon to the Congress."

- Directed the comptroller general to "review and evaluate the results of Government programs and activities" on his own initiative or at the request of either House or any standing or joint committee and to assist committees in analyzing and assessing program reviews or evaluation studies. Authorized GAO to establish an Office of Program Review and Evaluation to carry out these responsibilities.

- Strengthened GAO's role in acquiring fiscal, budgetary, and program-related information;

- Established House and Senate Budget Committees and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). The CBO director is authorized to "secure information, data, estimates, and statistics directly from the various departments, agencies, and establishments" of the government.

- Required any House or Senate legislative committee report on a public bill or resolution to include an analysis (prepared by CBO) providing an estimate and comparison of costs that would be incurred in carrying out the bill during the next and following four fiscal years in which it would be effective.

- Public Debt Limit Increase of 2010 (P.L. 111-139):

- Required the comptroller general to conduct routine investigations to identify programs, agencies, offices, and initiatives with duplicative goals and activities within departments and government-wide and report annually to Congress on the findings, including the cost of such duplication.

- GAO Access and Oversight Act of 2017 (P.L. 115-3):

- Authorized GAO to obtain federal agency records, including through civil actions, required to discharge GAO's audit, evaluation, and investigative duties.

- Provided that no provision of the Social Security Act shall be construed to limit, amend, or supersede GAO's authority to obtain information or inspect records about an agency's duties, powers, activities, organization, or financial transactions.

- Required agency statements on actions taken or planned in response to GAO recommendations to be submitted to the congressional committees with jurisdiction over the pertinent agency program or activity.

Indirect Expansions of Congress's Oversight Power

Separate from expanding its own authority and resources directly, Congress has strengthened its oversight capabilities indirectly by, for instance, establishing study commissions to review and evaluate programs, policies, and operations of the government. In addition, Congress has created various mechanisms, structures, and procedures within the executive branch that improve the executive's ability to monitor and control its own operations and, at the same time, provide additional information and oversight-related analyses to Congress. These statutory provisions include

- Inspector General Act of 1978 (P.L. 95-452, 5 U.S.C. Appendix 3): Established offices of inspectors general in all cabinet departments and larger agencies and numerous boards, commissions, and government corporations.

- Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-576): Established chief financial officers in all cabinet departments and larger agencies.

- Financial Integrity Act of 1982 (P.L. 97-255): Designed to improve the government's ability to manage its programs.

- Cash Management Improvement Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-453): Designed to improve the efficiency, effectiveness, and equity in the exchange of funds between the federal government and state governments.

- Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 (P.L. 103-62), as amended by the GPRA Modernization Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-352): Designed to increase efficiency, effectiveness, and accountability within the government.

- Government Management and Reform Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-356): Designed to improve the executive's stewardship of federal resources and accountability.

- Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995 (P.L. 104-13): Controlled federal paperwork requirements.

- Information Technology Management Reform Act (P.L. 104-106): Established the position of chief information officer in federal agencies to provide relevant advice for purchasing the best and most cost-effective information technology available.

- Single Audit Act of 1984 (P.L. 98-502), as amended by the Single Audit Act Amendments of 1996 (P.L. 104-156): Established uniform audit requirements for state and local governments and nonprofit organizations receiving federal financial assistance;

- Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-121): Created a mechanism, the Congressional Review Act (CRA), by which Congress can review and disapprove a final federal rule or regulation.

- Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-343):

- Allowed the Secretary of the Treasury to purchase and insure "troubled assets" to help promote the strength of the economy and financial system. The act established two organizations to provide broad oversight of the program—a Financial Stability Oversight Board and a Congressional Oversight Panel.

- Placed audit responsibilities for the program with two individuals—a new special inspector general for the Troubled Asset Relief Program and the comptroller general. In 2010, Congress called on GAO to report annually, identifying "areas of potential duplication, overlap, and fragmentation, which, if effectively addressed, could provide financial and other benefits."

- Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act of 2006 (P.L. 109-282): Enabled the public to access information on all entities and organizations receiving federal grants and contracts over $25,000. Summary information on these matters is made available on a single, searchable website: USASpending.gov. The law required the comptroller general to submit a report to Congress on compliance with the act. The 2006 law was amended two years later by the Government Funding Transparency Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-252). It required recipients of federal awards to report certain information about themselves and other recipients.

- Digital Accountability and Transparency Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-101):

- Established government-wide standardization of federal spending data beyond grants and contracts with the aim of creating a unified, publicly accessible data set of information on all federal spending.

- Required the comptroller general, after reviewing federal agency inspector general reports, to submit to Congress and make publicly available a report assessing and comparing the completeness, timeliness, quality, and accuracy of the data submitted by federal agencies and the implementation and use of data standards by federal agencies.

Illustrative Examples of House and Senate Rules on Oversight

House Rules

House rules15 grant the Committee on Oversight and Reform a comprehensive role in the conduct of oversight. For example, the committee has the authority or responsibility to

- review and study on a continuing basis the operation of government activities at all levels, including the Executive Office of the President (Rule X, clause 3).

- receive and examine reports of the Comptroller General and submit to the House such recommendations as it considers necessary or desirable in connection with the subject matter of the reports (Rule X, clause 4).

- study intergovernmental relationships between the United States and the states and municipalities and between the United States and international organizations of which the United States is a member (Rule X, clause 4).

- conduct investigations, at its discretion and at any time, of matters that are jurisdictionally conferred to another standing committee. The findings and recommendations of the Oversight and Reform Committee in such an investigation shall be made available to any other standing committee having jurisdiction over the matter involved (Rule X, clause 4).

- report to the House not later than April 15 in the first session of a Congress—after consultation with the Speaker, the majority leader, and the minority leader—the authorization and oversight plans submitted by the committees together with any recommendations that the Oversight and Reform Committee, or the House leadership group, may make to ensure the most effective coordination of authorization and oversight plans (Rule X, clause 2).

- choose to adopt a rule authorizing and regulating the taking of depositions by a Member or counsel of the committee including pursuant to subpoena under clause 2(m) of Rule XI (Rule X, clause 4).

- evaluate the effect of laws enacted to reorganize the legislative and executive branches of government.

House rules also provide authority for oversight by other standing committees as follows:

- Each standing committee (except Appropriations) shall review and study the application, administration, execution, and effectiveness of all laws within its jurisdiction and determine whether laws and programs addressing subjects within its jurisdiction should be continued, curtailed, or eliminated (Rule X, clause 2). Information pertinent to committee oversight and investigative procedures, such as subpoena power, can be found in Rule XI, clauses 1 and 2.

- Committees have the authority to review and study the impact or probable impact of tax policies on subjects that fall within their jurisdiction (Rule X, clause 2).

- Certain committees have special oversight authority (i.e., to review and study, on an ongoing basis, specific subject areas that are within the legislative jurisdiction of other committees). Special oversight is somewhat akin to the broad oversight authority granted the Committee on Oversight and Reform by the 1946 Legislature Reorganization Act except that special oversight is generally limited to named subjects (Rule X, clause 3).

- Each standing committee having more than 20 members shall establish an oversight subcommittee or require its subcommittees to conduct oversight in their respective jurisdictional areas (Rule X, clause 2 and 5).

- Committee reports on measures are to include oversight findings separately set out and clearly identified. They are also to include a statement of general performance goals and objectives, including outcome-related goals and objectives, for which the measure authorizes funding (Rule XIII, clause 3).

- Each standing committee, or a subcommittee thereof, shall hold at least one hearing during each 120-day period following the establishment of the committee on the topic of waste, fraud, abuse, or mismanagement in government programs that that committee may authorize. Such hearings shall include a focus on the most egregious instances of waste, fraud, abuse, or mismanagement in government programs as documented by any report the committees have received from the comptroller general or an inspector general. Committee and subcommittees shall also hold at least one hearing on issues raised by reports issued by the comptroller general indicating that federal programs or operations that the committee may authorize are at high risk for waste, fraud, and mismanagement, known as the "high-risk list" or "high-risk series" (Rule XI, clause 2).

- The chair of each standing committee (except Appropriations, Ethics, and Rules) shall prepare, in consultation with the ranking minority member, an oversight plan for that Congress not later than March 1 of the first session of a Congress. Committee plans shall be submitted simultaneously to the Committees on Oversight and Reform and House Administration. No later than April 15 in the first session of a Congress—after consultation with the Speaker, the majority leader, and the minority leader—the Committee on Oversight and Reform shall report to the House on the oversight plans of the committees together with any recommendations that it, or the House leadership group, may make to ensure the most effective coordination of oversight plans and otherwise to achieve these objectives. In developing their plans, each standing committee shall to the maximum extent feasible (Rule X, clause 2):

- consult with other committees that have jurisdiction over the same or related laws, programs, or agencies with the objective of ensuring maximum coordination and cooperation among committees when conducting reviews of such laws, programs, or agencies and include in the plan an explanation of steps that have been or will be taken to ensure such coordination and cooperation;

- review specific problems with federal rules, regulations, statutes, and court decisions that are ambiguous, arbitrary, or nonsensical or that impose severe financial burdens on individuals;

- give priority consideration to including in the plan the review of those laws, programs, or agencies operating under permanent budget authority or permanent statutory authority;

- have a view toward ensuring that all significant laws, programs, or agencies within the committee's jurisdiction are subject to review every 10 years; and

- have a view toward insuring against duplication of federal programs.

- Each committee must submit to the House not later than January 2 of each odd-numbered year a report that includes (Rule XI, clause 1):

- separate sections summarizing the legislative and oversight activities of the committee during the applicable period,

- a summary of the oversight plans submitted by the committee,

- a summary of the actions taken and recommendations made with respect to the authorization and oversight plans, and

- a summary of any additional oversight activities undertaken by that committee and any recommendations made or actions taken thereon.

In addition, the Speaker, with the approval of the House, may appoint special ad hoc oversight committees for the purpose of reviewing specific matters within the jurisdiction of two or more standing committees (Rule X, clause 2).

Senate Rules

Under Senate Rules,16 each standing committee (except for Appropriations and Budget) shall review and study, on a continuing basis, the application, administration, and execution of those laws, or parts of laws, within its legislative jurisdiction (Rule XXVI, clause 8).

In addition to that general oversight requirement, "comprehensive policy oversight" responsibilities are granted to specified standing committees. This duty is similar to special oversight in the House. For example, the Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry is authorized to study and review, on a comprehensive basis, matters relating to food, nutrition, and hunger both in the United States and in foreign countries—and rural affairs—and report thereon from time to time (Rule XXV, clause 1(a)).

All standing committees, except Appropriations, are required to include regulatory impact evaluations in their committee reports accompanying each public bill or joint resolution (Rule XXVI, clause 11). The evaluations are to include matters such as

- an estimate of the numbers of individuals and businesses that would be regulated,

- a determination of the measure's economic impact and effect on personal privacy, and

- a determination of the amount of additional paperwork that will result from the regulations.

The Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs exercises jurisdiction over government operations generally and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in particular. Selected oversight duties under Rule XXV, clause 1(k) include

- reviewing and studying on a continuing basis the operation of government activities at all levels to determine their economy, effectiveness, and efficiency;

- receiving and examining reports of the comptroller general and submit recommendations as it deems necessary to the Senate;

- evaluating the effects of laws enacted to reorganize the legislative and executive branches of the government; and

- studying intergovernmental relationships between the United States and the states and municipalities and international organizations of which the United States is a member.

Finally, on March 1, 1948 (during the 80th Congress), the Senate adopted S.Res. 189, which established the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs (then titled the Committee on Government Operations). The subcommittee was an outgrowth of the 1941 Truman Committee (after Senator Harry Truman), which investigated fraud and mismanagement of the nation's war program. The Truman Committee ended in 1948, but the chairman of the Government Operations Committee transferred the functions of the Truman Committee to a subcommittee: the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. Since then this subcommittee has investigated scores of issues, such as government waste, fraud, and inefficiency.

Congressional Participants in Oversight

Members

Oversight is generally considered a committee activity. However, both casework and other project work conducted in Members' personal offices, or in their district or state offices, can result in findings about bureaucratic behavior and policy implementation. These discoveries, in turn, can lead to the adjustment of agency policies and procedures and to changes in public law.

Casework—responding to constituent requests for assistance on projects or complaints or grievances about program implementation—provides an opportunity to examine bureaucratic activity and operations, if only in a selective way. The accessibility of governmental websites also allows interested constituents to monitor federal activities and expenditures and to share their findings or observations with Members, relevant committees, and legislative staff.

Individual Members may also conduct their own investigations or ad hoc hearings or direct their staff to conduct oversight studies. Members might also request GAO, another legislative branch agency, a specially created party task force, a private research group, or some other entity to conduct an investigation. Individual lawmakers lack the authority to use compulsory processes (e.g., subpoenas) or conduct official hearings.

Committees

The most common method of conducting oversight is through the committee structure. Legislative history demonstrates that the House and Senate have long used their standing committees—as well as joint, select, or special committees—to investigate federal activities and agencies:

- The House Committee on Oversight and Reform and the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs have broad oversight jurisdiction over virtually the entire federal government. They have been vested with broad investigatory powers over government-wide activities.

- The House and Senate Committees on Appropriations have similar responsibilities when examining and reviewing the fiscal activities of the federal government.

- Each standing committee of Congress has oversight responsibilities for reviewing government activities principally within their jurisdiction. These panels also have the authority to establish oversight and investigative subcommittees. The establishment of an oversight subcommittee does not preclude the other legislative subcommittees from conducting oversight.

- Certain House and Senate committees have "special oversight" or "comprehensive policy oversight" of designated subject areas, as noted above.

Personal Staff

Constituent letters, complaints, and requests for projects and assistance frequently bring issues and deficiencies in federal programs and administration to the attention of Members and their personal office staffs. The casework performed by a Member's staff for constituents can be an effective oversight tool.

Casework can be an important vehicle for pursuing both the oversight and legislative interests of the Member. Members and their staff aides are mindful of the relationship between casework and the oversight function. This connection is facilitated by a regular exchange of ideas among the Member, legislative aides, and caseworkers on problems brought to the office's attention by constituents. Casework might also prompt legislative initiatives to resolve those problems.

Caseworkers and other legislative staffers may seek to maximize service to their Member's constituents when they establish a relationship with the staff of the subcommittees and committees that handle the areas of concern to the Member's constituents. Through this interaction, the staff of the pertinent standing committee(s) can be made aware of the problems with the agency or program in question, assess how widespread and significant they are, determine their causes, and recommend corrective action.

Member office staff might also identify cases that lead to formal changes in agency procedures and processes. Staff follow-up may enhance this type of informal oversight. Telephone and email inquiries, reinforced with written requests, tend to ensure agency attention to issues raised by caseworkers and Members' constituents.

Committee Staff

As issues become more complex, the professional staffs of committees can provide the expertise required to conduct effective oversight and investigations. Committee staff typically have the experience, knowledge, and analytical skills to conduct proficient and thorough oversight for the committees and subcommittees they serve. Committees may also call upon legislative support agencies for assistance, hire consultants, "borrow" staff from federal departments, or employ academics and others with specialized expertise.

Committee staff, in summary, occupy a central position in the conduct of oversight. Their informal contacts with executive officials at all levels constitute one of Congress's most effective techniques for performing its "continuous watchfulness" function.

Congressional Support Agencies and Offices

Of the agencies in the legislative branch, three directly assist Congress in support of its oversight function:

- 1. CBO;

- 2. CRS, of the Library of Congress; and

- 3. GAO.

For further detail on these offices, see "Oversight Information Sources and Consultant Services" later in this report.

Through their work assisting in the overall operations of the House and Senate, additional offices that might play a role in oversight include, among others, the House General Counsel's Office, House Parliamentarian's Office, Senate Parliamentarian's Office, House Clerk's Office, Secretary of the Senate's Office, Office of Senate Legal Counsel, Senate and House Historian's Office, and the Senate Library.

Oversight Coordination and Processes

A persistent challenge for Congress in conducting oversight is coordination among committees, both within each chamber as well as between the two houses. As the final report of the House Select Committee on Committees of the 93rd Congress noted, "Review findings and recommendations developed by one committee are seldom shared on a timely basis with another committee, and, if they are made available, then often the findings are transmitted in a form that is difficult for Members to use."17 Despite the passage of time, this statement remains relevant today. Oversight coordination between House and Senate committees is also uncommon, and it occurs primarily in the aftermath of perceived major policy failures or prominent inter-branch conflicts, as with the Iran-Contra affair and the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

Intercommittee cooperation on oversight can be beneficial for a variety of reasons. For example, it can help minimize unnecessary duplication and conflict and inhibit agencies from playing one committee against another. There are formal and informal ways to achieve oversight coordination among committees.

Oversight Coordination

General Techniques of Ensuring Oversight Coordination

The House and Senate can establish select or special committees to probe issues and agencies, promote public understanding of national concerns, and coordinate oversight of issues that span the jurisdiction of more than one standing committee.

House rules require the findings and recommendations of the Committee on Oversight and Reform to be considered by the authorizing committees if presented to them in a timely fashion. Such findings and recommendations are to be published in the authorizing committees' reports on legislation.18 House rules also require the oversight plans of committees to include ways to maximize coordination between and among committees that share jurisdiction over related laws, programs, or agencies.19

Specific Means of Ensuring Oversight Coordination

Specific means of ensuring oversight coordination include the following:

- Joint committee or subcommittee oversight hearings on programs or agencies.

- Informal agreement among committees to oversee certain agencies and not others. For example, the House and Senate Committees on Commerce agreed to hold oversight hearings on certain regulatory agencies in alternate years.

- Consultation between the authorizing and appropriations committees. The two Committees on Commerce have worked closely with their corresponding appropriations subcommittees to alert those panels to the authorizing committees' intent with respect to regulatory ratemaking by such agencies as the Federal Communications Commission.

Oversight Through Legislative and Investigative Processes

The Budget Process20

The Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974,21 as amended, enhanced the legislative branch's capacity to shape the federal budget. The act has had major institutional and procedural effects on Congress:

- Institutionally, Congress created three new entities: the Senate Committee on the Budget, the House Committee on the Budget, and CBO.

- Procedurally, the act established methods that permit Congress to determine budget policy as a whole; relate revenue and spending decisions; determine priorities among competing national programs; and ensure that revenue, spending, and debt legislation are consistent with the overall budget policy.

The budget process coexists with the established authorization and appropriation procedures and significantly affects each:

- On the authorization side, the Budget Act requires committees to submit their budgetary "views and estimates" on matters under their jurisdiction to the Committee on the Budget not later than six weeks after the President submits a budget or at such time that the Budget Committee might request.

- On the appropriations side, new contract and borrowing authority must go through the appropriations process. Subcommittees of the Appropriations Committees are assigned a financial allocation that determines how much may be included in the measures they report, although less than one-third of federal spending is subject to the annual appropriations process. (The tax and appropriations panels of each house also submit budgetary views and estimates to their respective Budget Committees.)

- In deciding spending, revenue, credit, and debt issues, Congress is sensitive to trends in the overall composition of the annual federal budget (expenditures for defense, entitlements, interest on the debt, and domestic discretionary programs).22

In short, these Budget Act reforms have the potential to strengthen oversight by enabling Congress to better relate program priorities to financial claims on the national budget. Each committee, knowing that it will receive a fixed amount of the total to be included in a budget resolution, has an incentive to scrutinize existing programs to make room for new programs or expanded funding of ongoing projects or to assess whether programs have outlived their usefulness.

The Authorization Process

Through its authorization power, Congress exercises significant control over government agencies. The entire authorization process may involve a host of oversight tools—hearings, studies, and reports—but the key to the process is the authorization statute.

An authorization statute creates and shapes government programs and agencies, and it contains the statement of legislative policy for the agency. Authorization is the first lever in congressional exercise of the power of the purse. It usually allows an agency to be funded, but it does not guarantee financing of agencies and programs. Frequently, authorizations establish dollar ceilings on the amounts that can be appropriated.

The authorization-reauthorization process is a significant oversight tool. Through this process, Members are informed about the work of an agency and given an opportunity to direct the agency's effort in light of experience.23

Expiration of an agency's program provides an opportunity for in-depth oversight. In recent decades, there has been a mix of permanent and periodic (annual or multi-year) authorizations, although reformers at times press for biennial budgeting (i.e., acting on a two-year cycle for authorizations, appropriations, and budget resolutions). Periodic reauthorizations increase the likelihood that an agency will be scrutinized systematically.

In addition to formal amendment of the agency's authorizing statute, the authorization process gives committees an opportunity to exercise informal, nonstatutory controls over the agency. An agency's understanding that it must come to the legislative committee for renewed authority increases the influence of the committee. This condition helps to account for the appeal of short-term authorizations. Nonstatutory controls used by committees to exercise direction over the administration of laws include statements made in

- committee hearings,

- committee reports accompanying legislation,

- floor debate, and

- contacts and correspondence with the agency.

If agencies fail to comply with these informal directives, the authorization committees can apply sanctions or move to convert the informal directive to a statutory command.

The Appropriations Process

The appropriations process is among Congress's most significant forms of oversight. Its strategic position stems from the constitutional requirement that "no Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law."24 This "power of the purse" allows the House and Senate Committees on Appropriations to play a prominent role in oversight.

The oversight function of the Committees on Appropriations derives from their responsibility to examine the budget requests of the agencies as contained in the President's budget. The decisions of the committees are conditioned on their assessment of the agencies' need for their budget requests as indicated by past performance. In practice, the entire record of an agency is fair game for the required assessment. This comprehensive overview and the "carrot and stick" of appropriations recommendations make the committees significant focal points of congressional oversight and are a key source of their power in Congress and in the federal government generally.25

Enacted appropriations legislation frequently contains at least five types of statutory controls on agencies:

- 1. It specifies the purpose for which funds may be used.

- 2. It defines the specified funding level for the agency as a whole as well as for programs and divisions within the agency.

- 3. It sets time limits on the availability of funds for obligation.

- 4. It may contain limitation provisions. For example, in appropriating $350 million to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for research and development, Congress added this condition: "Provided, That not more than $55,000,000 of these funds shall be available for procurement of laboratory equipment, supplies, and other operating expenses in support of research and development."26

- 5. It may stipulate how an agency's budget can be reprogrammed (shifting funds within an appropriations account).

Nonstatutory controls are a major form of oversight. Language in committee reports and in hearings, letters to agency heads, and other communications give detailed instructions to agencies regarding committee expectations and desires. Agencies are not legally obligated to abide by nonstatutory recommendations, but failure to do so may result in a loss of funds and flexibility the following year. Agencies ignore nonstatutory controls at their peril.

|

An Example of Nonstatutory Control of Agency Appropriations The conference report for the Omnibus Consolidated and Emergency Supplemental Appropriations for FY1999 provides guidelines for the reprogramming and transfer of funds for the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act, 1999. Each request from an agency to the review committee "shall include a declaration that, as of the date of the request, none of the funds included in the request have been obligated, and none will be obligated, until the Committees on Appropriations have approved the request."27 |

The Investigatory Process

Congress's power to investigate is implied in the Constitution. Numerous Supreme Court decisions have upheld the legislative branch's right of inquiry, provided it stays within its legitimate legislative sphere. The roots of Congress's authority to conduct investigations extend back to the British Parliament and colonial assemblies. In addition, the House of Representatives has been described as the "grand inquest of the nation."28 Since the Framers expected lawmakers to employ the investigatory function, based upon parliamentary precedents, it was seen as unnecessary to invest Congress with an explicit investigatory power.

Investigations and related activities may be conducted by

- individual Members,

- committees and subcommittees,

- staff or outside organizations and personnel under contract, or

- congressional support agencies such as GAO and CRS.

Investigations may serve several purposes:

- They can help to ensure honesty and efficiency in the administration of laws.

- They can secure information that assists Congress in making informed policy judgments.

- They may aid in informing the public about the administration of laws.

See the next section of this report on "Investigative Oversight" for greater detail and analysis.

The Confirmation Process

By establishing a public record of the policy views of nominees, congressional hearings allow lawmakers to call appointed officials to account at a later time. Since at least the Ethics in Government Act of 1978,29 which encouraged greater scrutiny of nominations, Senate committees have set aside more time to probe the qualifications, independence, and policy views of presidential nominees, seeking information on everything from their physical health to their financial assets. The confirmation process can assist in oversight in at least three ways:

- 1. The Constitution provides that the President "shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law."30 The consideration of appointments to executive branch leadership positions is a major responsibility of the Senate and especially of Senate committees, which review and hold hearings regarding the qualifications of nominees.

- 2. Confirmation hearings serve as an opportunity for senatorial oversight and influence, providing a forum for the discussion of the policies and programs the nominee intends to pursue. The confirmation process as an oversight tool can be used to provide policy direction to nominees, inform nominees of congressional interests, and seek commitments on future behavior.

- 3. Once a nominee has been confirmed by the Senate, oversight includes following up to ensure that the nominee fulfills any commitments made during confirmation hearings. Subsequent hearings and committee investigations can explore whether such commitments have been kept.

The President has alternative authority to make appointments that do not require the advice and consent of the Senate, including, under certain circumstances, recess appointments31 and designations under the Vacancies Act.32

The Impeachment Process

The impeachment power of Congress is a unique oversight tool available to Congress. Impeachment applies to the President, Vice President, and other federal civil officers in the executive and judicial branches.33 Impeachment offers Congress

- a constitutionally mandated method for obtaining information that might otherwise not be made available, and

- an implied threat of punishment for an official whose conduct exceeds acceptable boundaries.

Impeachment procedures differ from those of conventional congressional oversight. The most significant procedural differences center on the roles played by each house of Congress. The House of Representatives has the sole power to impeach.34 A simple majority is needed in the House to approve articles of impeachment. The Senate has the sole power to try an impeachment.35 A two-thirds majority is required in the Senate to convict and remove the individual. Should the Senate deem it appropriate in a given case, it may, by majority vote, impose an additional judgment of disqualification from holding further federal offices of honor, trust, or profit.36

The impeachment process is cumbersome and infrequently used. The House has voted to impeach in 20 cases. The Senate has voted to convict in eight cases, all pertaining to federal judges. The most recent executive impeachment trial was that of President Clinton in 1998-1999;37 the most recent judicial impeachment trial was that of U.S. District Court Judge G. Thomas Porteous Jr. in 2010. A number of constitutional and procedural issues were addressed in the Clinton impeachment trial and other past impeachment proceedings, although the answers to some of these questions remain ambiguous. For example

- The impeachment process has been continued from one Congress to the next,38 although the procedural steps vary depending upon the stage in the process.

- The Constitution defines the grounds for impeachment as "Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors."39 However, the meaning and scope of "high Crimes and Misdemeanors" remains in some dispute and depends on the interpretation of individual legislators.

- The Constitution provides for impeachment of the "President, Vice President, and all civil Officers of the United States."40 While the outer limit of the "civil Officers" language is not altogether clear, past precedents suggest that it covers at least federal judges and executive officers subject to the Appointments Clause.

- Members of the House and Senate are not subject to impeachment because they are not "civil officers." The House impeached William Blount, a U.S. Senator from Tennessee, in 1797, but the Senate chose to expel him from the Senate instead of conducting an impeachment trial.

Investigative Oversight41

Congressional oversight and investigations, which are often adversarial, can serve to sustain and vindicate Congress's role in the United States' constitutional scheme of separated powers. The rich history of congressional investigations—from the failed St. Clair expedition in 1792 and including Teapot Dome, Watergate, Iran-Contra, and Whitewater—have established, both legally and as a matter of practice, the nature and contours of congressional prerogatives necessary to maintain the integrity of the legislative branch.

This section provides an overview of some of the more common legal, procedural, and practical issues that committees may face in the course of conducting oversight and/or congressional investigations. It begins with a general summary of Congress's constitutional authority to perform oversight and investigations. It then turns to a discussion of the legal tools commonly used by congressional committees in conducting oversight and investigations, including the legal basis for subpoenas, staff depositions, and committee hearings, as well as a discussion of the various forms of contempt of Congress, the primary enforcement mechanism available. The section will then discuss limitations on congressional authority to conduct successful oversight and investigations, including constitutional privileges, such as executive privilege. Finally, the section will address a series of frequently encountered legal issues, such as the applicability of the Privacy Act and the Freedom of Information Act, access to grand jury materials and pending litigation files, and access to classified and confidential information.

Constitutional Authority to Perform Oversight and Investigative Inquiries

Congress's authority to obtain information, including classified and confidential information, is, generally speaking, broad. While there is no express provision of the Constitution or specific statute authorizing the conduct of congressional oversight or investigations, the Supreme Court has firmly established that such power is essential to the legislative function as to be implied from the general vesting of legislative powers in Congress.42 In Eastland v. United States Servicemen's Fund, for instance, the Court stated that the "scope of its power of inquiry … is as penetrating and far-reaching as the potential power to enact and appropriate under the Constitution."43 In Watkins v. United States, the Court emphasized that the "power of the Congress to conduct investigations is inherent in the legislative process. That power is broad. It encompasses inquiries concerning the administration of existing laws as well as proposed or possibly needed statutes."44 The Court also noted that the first Congresses held "inquiries dealing with suspected corruption or mismanagement of government officials"45 and stated that the investigative power "comprehends probes into departments of the federal government to expose corruption, inefficiency, or waste."46

Authority of Congressional Committees

Oversight and investigative authority is implied in Article I of the Constitution and rests with the House of Representatives and Senate. The House and Senate have delegated this authority to various entities, the most relevant of which are the standing committees of each chamber. Committees of Congress have the power only to inquire into matters within the scope of the authority delegated to them by their parent bodies.47 However, a committee's investigative purview is substantial and wide-ranging if it satisfies this jurisdictional requirement and if the committee has a legislative purpose for conducting the inquiry.

Committee Jurisdiction

Establishing committee jurisdiction is the foundation for any attempt to obtain information and documents from the executive branch or a private entity or person. A claim of lawful jurisdiction, however, does not automatically entitle the committee to access whatever documents and information it may seek. Rather, an appropriate claim of jurisdiction authorizes the committee to inquire and request information. The specifics of such access may still be subject to prudential, political, and constitutionally based privileges asserted by the targets of the inquiry.

A congressional committee is a creation of its parent house and, therefore, can inquire only into matters within the scope of the authority that has been delegated to it by that body.48 Thus, the enabling chamber rule or resolution that gives life to the committee also defines the grant and limitations of the committee's power.49 In construing the scope of a committee's authorizing charter, courts look to the words of the rule or resolution itself and then, if necessary, to the usual sources of legislative history such as floor debate, legislative reports, and prior committee practice and interpretation.

House Rule X and Senate Rule XXV address the organization of each chamber's standing committees and establish their jurisdiction.50 Jurisdictional authority for "special" investigations may be given to a standing committee, a joint committee of both houses, a subcommittee of a standing committee, or another entity (a "task force," for instance). The current House and Senate rules confer jurisdiction on their standing committees with a high degree of specificity, and in recent years, the authorizing resolutions for special and select committees have also been drafted with particular care. Therefore, it may be more difficult for a noncompliant witness to claim in court that a committee has overstepped its delegated scope of authority.

Legislative Purpose

While the congressional power of inquiry is broad, it is not unlimited. The Supreme Court has cautioned that the power to investigate may be exercised only "in aid of the legislative function"51 and cannot be used to expose for the sake of exposure alone. The Watkins Court underlined these limitations, stating

There is no general authority to expose the private affairs of individuals without justification in terms of the functions of the Congress … nor is the Congress a law enforcement or trial agency. These are functions of the executive and judicial departments of government. No inquiry is an end in itself; it must be related to, and in furtherance of, a legitimate task of the Congress.52

A committee's inquiry must have a legislative purpose or be conducted pursuant to some other constitutional power of Congress, such as the authority of each House to discipline its own members, judge the returns of their elections, and conduct impeachment proceedings.53 The 1881 Supreme Court decision in Kilbourn v. Thompson54 held that the challenged investigation was an improper probe into the private affairs of individuals. However, in McGrain v. Daugherty, the Court presumed legislative purpose for an investigation.55 The House or Senate rule or resolution authorizing the investigation does not have to specifically state the committee's legislative purpose.56 In In re Chapman,57 the Court upheld the validity of a resolution authorizing an inquiry into charges of corruption against certain Senators despite the fact that it was silent as to what might be done when the investigation was completed. The Court stated

The questions were undoubtedly pertinent to the subject matter of the inquiry. The resolutions directed the committee to inquire "whether any Senator has been, or is, speculating in what are known as sugar stocks during the consideration of the tariff bill now before the Senate." What the Senate might or might not do upon the facts when ascertained, we cannot say nor are we called upon to inquire whether such ventures might be defensible, as contended in argument, but it is plain that negative answers would have cleared that body of what the Senate regarded as offensive imputations, while affirmative answers might have led to further action on the part of the Senate within its constitutional powers.

Nor will it do to hold that the Senate had no jurisdiction to pursue the particular inquiry because the preamble and resolutions did not specify that the proceedings were taken for the purpose of censure or expulsion, if certain facts were disclosed by the investigation. The matter was within the range of the constitutional powers of the Senate. The resolutions adequately indicated that the transactions referred to were deemed by the Senate reprehensible and deserving of condemnation and punishment. The right to expel extends to all cases where the offense is such as in the judgment of the Senate is inconsistent with the trust and duty of a Member.

We cannot assume on this record that the action of the Senate was without a legitimate object, and so encroach upon the province of that body. Indeed, we think it affirmatively appears that the Senate was acting within its right, and it was certainly not necessary that the resolutions should declare in advance what the Senate meditated doing when the investigation was concluded.58

In McGrain v. Daugherty,59 the original resolution that authorized the Senate investigation into the Teapot Dome affair made no mention of a legislative purpose. A subsequent resolution for the attachment of a contumacious witness declared that his testimony was sought for the purpose of obtaining "information necessary as a basis for such legislative and other action as the Senate may deem necessary and proper."60 The Court found that the investigation was ordered for a legitimate legislative purpose. It wrote

The only legitimate object the Senate could have in ordering the investigation was to aid it in legislating, and we think the subject matter was such that the presumption should be indulged that this was the real object. An express avowal of the object would have been better; but in view of the particular subject-matter was not indispensable….

The second resolution—the one directing the witness be attached—declares that this testimony is sought with the purpose of obtaining "information necessary as a basis for such legislative and other action as the Senate may deem necessary and proper." This avowal of contemplated legislation is in accord with what we think is the right interpretation of the earlier resolution directing the investigation. The suggested possibility of "other action" if deemed "necessary or proper" is of course open to criticism in that there is no other action in the matter which would be within the power of the Senate. But we do not assent to the view that this indefinite and untenable suggestion invalidates the entire proceeding. The right view in our opinion is that it takes nothing from the lawful object avowed in the same resolution and is rightly inferable from the earlier one. It is not as if an inadmissible or unlawful object were affirmatively and definitely avowed.61

Moreover, it has been held that a court cannot say that a committee of Congress exceeds its power when the purpose of its investigation is supported by reference to specific problems that in the past have been, or in the future may be, the subject of appropriate legislation.62 In the past, the types of legislative activity that have justified the exercise of investigative power have included the primary functions of legislating and appropriating,63 the function of deciding whether or not legislation is appropriate,64 oversight of the administration of the laws by the executive branch,65 and the congressional function of informing itself in matters of national concern.66 In addition, Congress's power to investigate such diverse matters as foreign and domestic subversive activities,67 labor union corruption,68 and organizations that violate the civil rights of others69 have all been upheld by the Supreme Court.

Despite the Court's broad interpretation of legislative purpose, its scope is not without limits. Courts have held that a committee lacks legislative purpose if it appears to be conducting a legislative trial rather than an investigation to assist in performing its legislative function.70 However, although "there is no congressional power to expose for the sake of exposure,"71 "so long as Congress acts in pursuance of its constitutional power, the Judiciary lacks authority to intervene on the basis of the motives which spurred the exercise of that power."72

Legal Tools Available for Oversight and Investigations

A review of congressional precedents indicates that there is no single method or set of procedures for engaging in oversight or conducting an investigation.73 Historically, congressional committees appeared to rely a great deal on public hearings and subpoenaed witnesses to gather information and accomplish their investigative goals. In more recent years, congressional committees have seemingly relied more heavily on staff level communication and contacts as well as other "informal" attempts at gathering information—document requests, informal briefings, interviews, etc.—before initiating the necessary formalistic procedures such as issuing committee subpoenas, holding on-the-record depositions, and/or engaging the subjects of inquiries in public hearings. This section discusses the formal process of issuing subpoenas, depositions, and holding committee hearings. This section also reviews Congress's authority to grant witnesses limited immunity for the purpose of obtaining information and testimony that may be protected by the Fifth Amendment's right against self-incrimination.

Subpoena Power

As a corollary to Congress's accepted oversight and investigative authority, the Supreme Court has determined that the issuance of subpoenas "has long been held to be a legitimate use by Congress of its power to investigate."74 The Court has referred to the subpoena power as "an essential and appropriate auxiliary to the legislative function"75 and said the following about its usefulness to Congress:

A legislative body cannot legislate wisely or effectively in the absence of information respecting the conditions which the legislation is intended to affect or change; and where the legislative body does not itself possess the requisite information—which not infrequently is true—recourse must be had to others who do possess it. Experience has taught that mere requests for such information often are unavailing, and also that information which is volunteered is not always accurate or complete; so some means of compulsion are essential to obtain what is needed. All this was true before and when the Constitution was framed and adopted. In that period the power of inquiry—with enforcing process—was regarded and employed as a necessary and appropriate attribute of the power to legislate—indeed, was treated as inhering in it.76

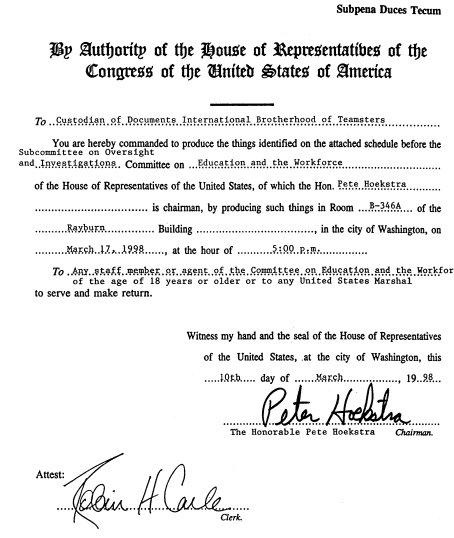

A properly authorized subpoena issued by a committee or subcommittee has the same force and effect as a subpoena issued by the parent house itself. Individual committees and subcommittees must be delegated the authority to issue subpoenas. Senate Rule XXVI(1) and House Rule XI(2)(m)(1) presently empower all standing committees and subcommittees to issue subpoenas requiring the attendance and testimony of witnesses and the production of documents. Special or select committees must be specifically delegated that authority by Senate or House resolution. The rules governing issuance of committee subpoenas vary by committee. Some committees require a full committee vote to issue a subpoena, while others empower the chairman to issue them unilaterally or with the concurrence of the ranking minority member.77

Congressional subpoenas are served by the U.S. Marshal's office, committee staff, or the Senate or House Sergeants-at-Arms. Service may be effected anywhere in the United States. The subpoena power has been held to extend to aliens physically present in the United States. As will be discussed below, however, securing compliance of U.S. nationals and aliens living in foreign countries is more complex.78

A witness seeking to challenge the legal sufficiency of a subpoena has limited remedies to defeat the subpoena even if it is found to be legally deficient. In order for a subpoena to be valid, the underlying investigation must meet the following general criteria, as articulated by the Supreme Court in Wilkinson v. United States:

- The committee's investigation of the broad subject matter area must be authorized by Congress.

- The investigation must be pursuant to "a valid legislative purpose."79

- The specific inquiries must be pertinent to the broad subject matter areas that have been authorized by Congress.80

However, regardless of the subpoena's legal sufficiency, courts will generally not entertain a subpeona recipient's attempt to block a subpoena under the Speech or Debate Clause because the Constitution81 provides "an absolute bar to judicial interference" with such compulsory process.82 As a consequence, a witness's typical judicial recourse is to refuse to comply with the subpoena, risk being cited for contempt, and then challenge the legal sufficiency of the subpoena in the contempt prosecution.

Staff Deposition Authority

Committees often rely on informal staff interviews to gather information to prepare for investigative hearings. However, in recent years, congressional committees have also used staff-conducted depositions as a tool in exercising their investigatory power.83 On a number of occasions such specific authority has been granted pursuant to Senate and House resolutions.84 When granted, procedures for taking depositions may be issued, including provisions for notice (with or without a subpoena), transcription of the deposition, the right to be accompanied by counsel, and the manner in which objections to questions are to be resolved.85

Staff depositions afford a number of significant advantages for committees engaged in complex investigations, including the ability to