Introduction to HUD

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is responsible for administering a set of programs and activities that are primarily designed to address housing problems faced by households with low incomes or other special housing needs.1 These include several programs of rental assistance for persons who are poor, elderly, and/or have disabilities. Two primary rental assistance programs—Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers, and Section 8 project-based rental assistance—account for the majority of the department's non-emergency funding (64% of total HUD appropriations in FY2019). Two flexible block grant programs—HOME and Community Development Block Grants (CDBG)—help communities finance a variety of housing and community development activities designed to serve low-income families. Other, more specialized grant programs help communities meet the needs of homeless persons, including those with AIDS. Additionally, HUD's Federal Housing Administration (FHA) is designed to increase access to mortgage credit by insuring mortgages made by lenders to home buyers with low down payments and to developers of multifamily rental buildings containing relatively affordable units. Nearly all of the funding for HUD's programs and activities comes from discretionary appropriations provided each year in annual appropriations acts.

This report explores the trends in HUD's funding since FY2002. It begins with an explanation of the key budget concepts necessary to understand those trends. It concludes with a discussion of factors that may influence HUD's budget going forward. This report is current through the most recently completed fiscal year; for current year funding and status, please see the CRS Appropriations Status Table.

Components of HUD Funding: Key Concepts

HUD's annual budget, as considered by congressional appropriators, is generally comprised of several components: regular annual appropriations, emergency appropriations, rescissions, and offsets.2

HUD's programs and activities are funded almost entirely through discretionary3 regular annual appropriations. The amount provided through annual appropriations acts generally determines how much funding can be obligated and eventually spent for each of HUD's programs and activities.4 This is frequently referred to as gross budget authority.

In some years, emergency appropriations are also enacted, usually in response to disasters, for one or more of HUD's programs. This additional budget authority is often provided outside of the regular appropriations acts—often in emergency supplemental spending bills—and is provided in addition to regular annual appropriations.

Appropriations measures are generally subject to limits, or caps, on the amount of new non-emergency discretionary funding that can be provided in a fiscal year. One way to stay within these limits is to provide less in regular annual appropriations. Another way is to find offsets. A portion of the cost of HUD's regular annual appropriations acts is, in most years, offset in two ways. The first is through rescissions, or cancellations of unobligated or recaptured balances from previous years' funding. The second is through offsetting receipts and collections,5 which include fees paid by HUD partners or clients and estimated savings resulting from the way in which HUD's mortgage insurance programs are accounted for in HUD's budget (discussed later in this report).

The interaction between new appropriations and offsets provided through rescissions, receipts, and collections determines HUD's total net budget authority. Net budget authority is also the "cost" of the HUD budget, as estimated by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) in its scorekeeping process.6 The total amount of net budget authority provided to HUD each year is important for federal budgeting purposes, as net budget authority is the amount that counts against discretionary spending limits.7

However, net budget authority is not necessarily the best measure of the amount of funding that is being provided for HUD's programs and activities. Because of the role of offsets, declining or increasing net budget authority does not necessarily mean declining or increasing regular appropriations available for HUD's programs and activities. For example, if $2 billion in offsetting receipts or rescissions is available in a given year, Congress can provide $30 billion in regular appropriations for HUD's programs and activities, but it will only "cost" $28 billion for budget enforcement purposes.

As noted earlier, the amount provided in appropriations, not reduced for the savings generated from offsets, generally best reflects the amount of new funding available for HUD's programs and activities in a year.

Recent Trends

Overall Budget Authority

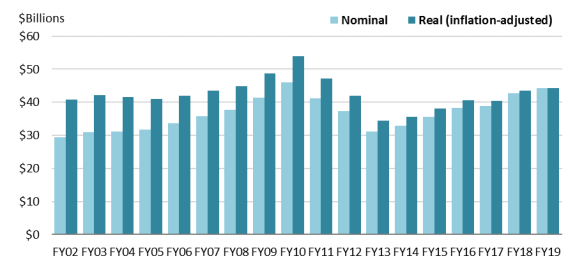

Since FY2002, HUD's regular (non-emergency) annual net budget authority has increased by 50% in terms of nominal (non-inflation adjusted) dollars, or 8% when adjusting for inflation.

As shown in Figure 1, the trend in HUD regular net budget authority has not been steady. HUD's budget received large year-over-year increases from FY2002 through FY2010 (in nominal dollars), with the largest taking place in FY2009 and FY2010. Between FY2002 and FY2010, HUD's nominal net budget authority increased by 57%; 32% in real terms. However, by FY2013, the year of discretionary spending sequestration, declines in regular net budget authority for HUD erased most of the growth that had been seen since FY2002 in terms of nominal dollars, and all of the growth in terms of real (or inflation-adjusted) dollars. Since the low-point of FY2013, HUD's net budget authority has begun increasing again, with FY2019 approaching the peak in FY2010 (in nominal dollars).

|

Figure 1. HUD Regular (Non-emergency) Net Budget Authority, FY2002-FY2019 In nominal and real (2019) dollars |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of congressional funding data contained in conference reports accompanying annual appropriations acts. See Table A-1 for data. Notes: Real figures are presented in 2019 dollars, adjusted using the GDP chained index from the President's FY2020 budget documents. Figures represent regular net budget authority, which includes appropriations, offsets, and rescissions, and excludes funding designated as emergency. Figures include advance appropriations available in the fiscal year. |

These increases and decreases in regular net budget authority tell an accurate story of HUD's funding from a federal budgeting standpoint. However, the story they tell in terms of resources available for HUD's programs and activities is more complicated. Some of the ups and downs are attributable as much or more to changes in the amount of savings available from offsets and rescissions as they are to changes in the amount of funding available for HUD's programs and activities.

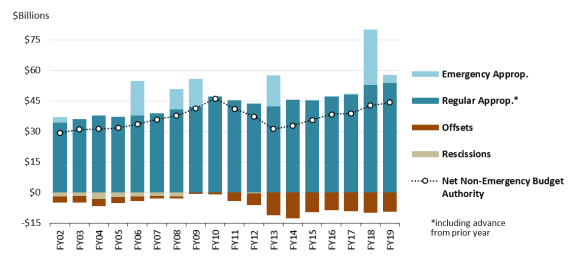

The next figure helps illustrate that interplay. As shown by the line in Figure 2, which repeats the nominal data shown by the light-colored bars in Figure 1, regular net budget authority for HUD increased about 50% between FY2002 and FY2019, from more than $29 billion to more than $44 billion, in nominal dollars. Yet, this overall increase masks several important interactions, which are illustrated by the bars in Figure 2.

|

Figure 2. Components of HUD Funding, FY2002-FY2019 (nominal) |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of congressional funding data contained in conference reports accompanying annual appropriations acts. See Table A-1 for data. |

Between FY2002 and FY2010, HUD's regular (non-emergency) net budget authority increased by 57% (shown by the dotted line in Figure 2). However, the amount of regular appropriations (which is the amount available for HUD's programs and activities) grew at a slower rate. During that period, regular annual appropriations—excluding emergency appropriations—grew by 37% (shown by dark blue bars in Figure 2). This means that from FY2002 to FY2010, funding for HUD's programs and activities (i.e., appropriations) did not grow as rapidly as it would appear from looking at the growth in HUD's regular net budget authority.

The difference between the growth in HUD's regular net budget authority and regular appropriations during this period is attributable to declines in offsets. Specifically, from FY2002 to FY2010 the amount available from offsetting receipts and collections and from rescissions declined by more than 70% and 96%, respectively (as shown in Figure 2). As explained earlier, these offsets are used to reduce the "cost" of appropriations for federal budget enforcement purposes. The decline in FHA receipts, discussed later in this report, was largely driven by a decline in FHA's overall market share, tied to the growing availability of subprime loans. The decline of rescissions was driven by trends in long-term Section 8 project-based rental assistance contracts (discussed later in this report). Specifically, as old contracts ended, there was often remaining budget authority that became available for rescission; as fewer and fewer old contracts remained, less and less of that original budget authority was available for rescissions.

The overall trend of increasing appropriations and decreasing offsets reversed beginning in FY2011 and continued through FY2013, when regular appropriations were cut relative to FY2010 and, at the same time, the amount of offsets increased. Regular appropriations were cut by about 4% in FY2011 relative to FY2010, by 4% in FY2012 relative to FY2011, and by 3% in FY2013 relative to FY2012. However, the reductions to HUD's regular net budget authority were much larger during this period. HUD's regular net budget authority was reduced by 11% in FY2011 compared to FY2010, by 9% in FY2012 compared to FY2011, and by 16% in FY2013 relative to FY2012. The difference in the size of the cut in net budget authority compared to the size of the cut in regular appropriations is the result of a nearly 12-fold increase in available offsets during this period (largely attributable to FHA, discussed in the next section).

As a result of the increase in offsets, the "cost" (for federal budgeting purposes) of providing appropriations for HUD's programs and activities declined from FY2010 to FY2013. In other words, the increases in offsets over this period meant that federal appropriators could realize larger budget savings even with smaller cuts in appropriations for HUD's programs and activities than they could have in the absence of such offsets.

Since FY2013, net budget authority for HUD rose 42%. The increase from FY2013-FY2019 is partly attributable to an increase in regular appropriations for HUD's program and activities (+27%), but also partly attributable to a decrease in savings from offsets and rescission (-15%)

FHA Offsetting Receipts

As mentioned earlier, in a constrained domestic discretionary funding environment, the role of savings from sources including offsetting receipts and rescissions of prior-year recaptured funding may significantly affect how much is provided in new regular appropriations for HUD's programs and activities.

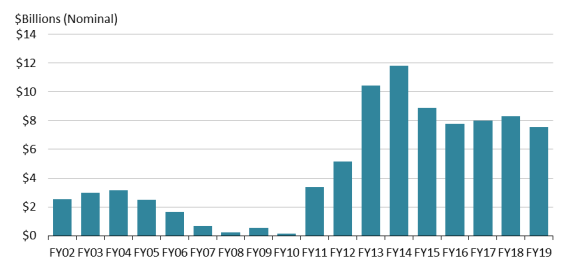

The largest share of offsets in the HUD budget has come from FHA. FHA, particularly its single-family insurance programs, generates offsetting receipts when the loans that are expected to be insured by the program in a given year are projected to collect more in fees paid by borrowers than will be needed to pay default claims to lenders over the life of the loans.8 As shown in Figure 3, the estimated amount of offsetting receipts from FHA can vary significantly from year to year.

From FY2002-FY2010, the amount available from FHA to offset the cost of new HUD appropriations declined from a high of more than $3 billion in FY2004 to $140 million in FY2010. This decline maps to FHAs declining market share over this period, as FHA's traditional customers—including first-time and lower-income homebuyers—began to access new subprime mortgage products.9

That trend reversed in FY2011, when the amount of offsetting receipts from FHA increased to more than $3.4 billion, the highest level in a decade. This trend continued into FY2012, with FHA receipts reaching over $5 billion and into FY2013 and FY2014, with offsetting receipts reaching historical highs of over $10 billion and $11 billion. These increases were attributable to FHA's increased market share following the 2007-2009 economic recession and downturn in the housing market, which included the collapse of the subprime mortgage market, as well as to policy changes made by FHA to tighten underwriting standards and increase the fees charged to new FHA-insured borrowers.10

FY2015 saw the first decline in FHA receipts since FY2010. While still at near-record levels (almost $9 billion), there were fears that FY2015 could be the beginning of a future decline in receipts, as the housing and credit markets recovered from the economic recession and FHA's market share began to decline. Receipts did decline for a second year in FY2016 (by almost $1 billion relative to the prior year), but fluctuated up and down from FY2017-FY2019. Whether FHA receipts will hold steady or begin to decline back closer to pre-recession levels is yet to be seen.

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of congressional funding data contained in conference reports accompanying annual appropriations acts. See Table A-1 for data. |

Growth in Section 8 Costs

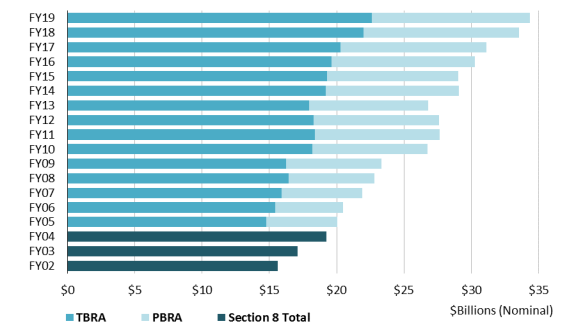

The growth in regular appropriations since FY2002 (shown by the dark blue bars in Figure 2) is largely attributable to growth in HUD's Section 8 tenant-based and project-based rental assistance accounts, which combined are the largest component of the HUD budget. The tenant-based rental assistance (TBRA) account funds the Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher program, and the project-based rental assistance (PBRA) account funds the Section 8 project-based rental assistance program.11 The vast majority of the funding provided to these accounts is used to provide for the annual renewal of rental housing assistance for the more than 3 million low-income families the programs currently serve.

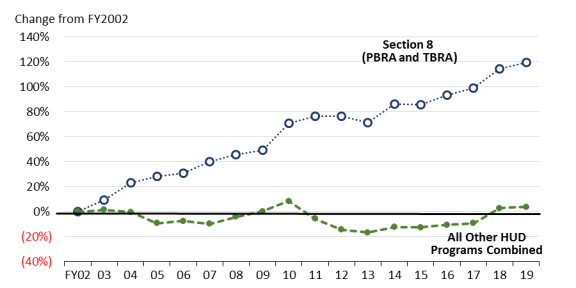

As can be seen in Figure 4, from FY2002 to FY2019 appropriations (in nominal dollars) for the combined Section 8 programs grew by 120%, while combined funding for all other HUD programs and activities increased by 4% overall, and for many years declined. During this period, the Section 8 programs went from accounting for about 46% of HUD's regular appropriations to accounting for about 64%.

|

Figure 4. Cumulative Percentage Change Since 2002 in Annual Appropriations for Section 8 Programs, Compared to All Other HUD Programs Combined (based on changes in nominal $) |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of congressional funding data contained in conference reports accompanying annual appropriations acts. See Table A-1 for data. Notes: Figures represent regular appropriations, not reduced for rescissions or offsets, and not including emergency appropriations. Figures for Section 8 include both tenant-based and project-based rental assistance, including advance appropriations available in the fiscal year, and are reduced for rescissions of funding from advance appropriations, but not rescissions of prior-year unobligated balances. TBRA: tenant-based rental assistance; PBRA: project-based rental assistance. |

As noted earlier, there are two Section 8 programs: tenant-based rental assistance (vouchers) and project-based rental assistance. These two programs were funded in the same account for many years, but since FY2005 they have been funded separately. As stated above and shown in Figure 4, appropriations for the Section 8 programs combined have grown by about 120% from FY2002 to FY2019. However, it is important to note that the rates of growth have not been the same across the two Section 8 programs. As shown in Figure 5, appropriations for the Section 8 project-based rental assistance (PBRA) account grew by 122% from FY2005 to FY2019; appropriations for the Section 8 tenant-based rental assistance (TBRA) account also grew, but by less than half the rate of the PBRA account, about 53%, during that time. The rapid growth in appropriations for PBRA is largely attributable to the renewal of old rental assistance contracts. PBRA contracts were originally created and funded in the 1970s and 1980s as long-term contracts funded by upfront appropriations estimated to be sufficient to cover their lifetime costs. When the original contracts expire and their original appropriations run out, 20-40 years later, they require new annual appropriations in order to be renewed so that they continue to be available to subsidize the housing of low-income families. The vast majority of PBRA contracts are now on an annual funding cycle, but a small and decreasing number of contracts expire each year and require new first-time renewal funding.

|

Figure 5. Section 8 Appropriations (TBRA and PBRA), FY2002-FY2019 (nominal $) |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of congressional funding data contained in conference reports accompanying annual appropriations acts. See Table A-1 for data. Notes: Figures include advance appropriations available in the fiscal year and are reduced for rescissions of funding from advance appropriations, but not rescissions of prior-year unobligated balances. PBRA and TBRA were funded in the same account until FY2005. Excludes emergency funding. |

Decline in Funding for Block Grant Programs

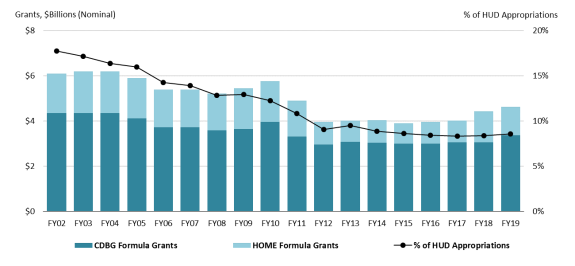

As illustrated in Figure 4, while funding for the two Section 8 programs has grown by about 120% since FY2002, funding for all other HUD programs combined has risen by about 4%. HUD's two largest block grant programs—the HOME Investment Partnerships program12 and the larger Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program13—have seen some of the greatest declines in funding over this period.

Of the two programs, formula grants under the HOME program have had the steepest decline in funding (-28% since FY2002) compared to CDBG (-22%). However, in terms of dollars, funding for CDBG formula grants has declined by the largest amount (about -$976 million) compared to HOME (-$497 million).

Combined, the formula grants under the HOME and the CDBG programs have seen a 24% decline in nominal funding from FY2002 to FY2019 (see Figure 6). While they accounted for nearly a fifth of HUD's total regular appropriations in FY2002, as shown in Figure 6, their combined share of HUD's total regular appropriations declined to 8.6% in FY2015 and has stayed at roughly that share since then.14

|

Figure 6. Appropriations for HOME and CDBG Formula Grants, FY2002-FY2019 Totals, and combined share of total HUD appropriations (nominal) |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of congressional funding data contained in annual appropriations acts and data contained in CRS Report R40118, An Overview of the HOME Investment Partnerships Program, by Katie Jones and CRS Report R43394, Community Development Block Grants: Recent Funding History, by Eugene Boyd. See Table A-1 for data. Notes: Figures represent regular appropriations, not reduced for rescissions or offsets, and not including emergency appropriations. |

Supplemental Emergency Funding for CDBG

While funding for regular CDBG formula grants has declined over this period, it is important to note that the Community Development Fund account (which funds CDBG) also has been provided with supplemental emergency funding over this period for special purposes, including to provide aid to communities in response to disasters, to respond to foreclosures, and to promote economic stimulus.15 Most of the nearly $92 billion in emergency funding provided to HUD from FY2002 through FY2019 (shown in Figure 2) was provided through the Community Development Fund account for these special purposes. These funds are generally not subject to the statutory limits on discretionary spending.16

Looking Ahead

The same factors that have driven the trends in funding for HUD and its programs and activities in the past are likely to continue to influence future trends. Further, new factors that may influence HUD's funding going forward have emerged, such as the expansion of the Rental Assistance Demonstration.

The Budget Control Act and Budget Enforcement

Among the factors that may have influenced and many continue to influence HUD's future funding levels is the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA, P.L. 112-25), as amended.17 In addition to other provisions, the BCA established enforceable discretionary spending limits. It also resulted in a discretionary sequestration in FY2013. The sequestration process required automatic, largely across-the-board, spending cuts at the account and program level to achieve specified deficit reduction targets. It took place on March 1, 2013, and resulted in a reduction of approximately $3 billion in funding for HUD in FY2013.

The initial lower discretionary spending limits contained in the BCA were meant to reduce the growth of discretionary spending over time. Meeting these lower discretionary spending limits requires providing less appropriations, achieving more offsets, or both, across the federal budget and, presumably, also in HUD's budget. In response to the challenges these lower spending limits presented for the annual appropriations process, the BCA was amended to raise the limits several times, most recently in 2019.18

Under current law, there are no statutory discretionary spending limits in place beyond FY2021. Whether projected growth in budget deficits will lead to further constraints on domestic discretionary spending in the future is unclear.19

Growth in Section 8 Costs

As noted earlier, appropriations for the Section 8 project-based and tenant-based (voucher) rental assistance subsidies have grown significantly and now represent nearly two-thirds of HUD's budget. This cost growth is unlikely to reverse in the near term for several reasons.

First, each year in the recent past new vouchers have been funded to serve additional families, primarily for homeless veterans and families and youth involved in the child welfare system. These new vouchers receive initial funding in the annual appropriations law in which they are created, but then require each year thereafter additional renewal funding through the annual appropriations process if that assistance is to be maintained.

Second, under the terms of the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD)20, HUD has been authorized to convert up to 445,000 units of public housing to either Section 8 voucher or Section 8 project-based rental assistance contracts. In the first year of conversion, the funding for those contracts is transferred from the public housing accounts to the tenant-based or project-based rental assistance accounts. However, after the first year the renewal needs of those contracts become a part of the base Section 8 contract renewal needs. Thus, 445,000 former public housing units will need renewal funding out of one of the Section 8 accounts when all of the currently authorized units complete their RAD conversions.

Finally, the costs of individual subsidies have gone up over time. Both programs effectively subsidize the difference between tenant's income-based contributions to rent and market or market-comparable rents. In many years, rents have been rising faster than incomes, particularly for the lowest-income families who are served by these programs. 21

Congress has heretofore demonstrated a commitment to providing sufficient funding so that all Section 8 project-based rental assistance contracts are renewed and every family that is receiving a Section 8 voucher—more than 3 million families all-told, including individuals who are elderly or have disabilities and families with children—can continue to receive assistance. As the cost of the programs has risen in recent years, particularly in light of constraints on domestic discretionary spending, questions about the future of that commitment have arisen and interest has been expressed in changes that could lead to cost savings. Some of these proposals have included program changes that would result in tenants paying higher rents. However, to the extent the commitment to renewing all in-use subsidies each year continues, and assuming market trends continue and significant cost-saving reforms are not enacted, it is unlikely that the cost of the PBRA and voucher programs will decline, and they are likely to continue to increase.

Funding for Other HUD Programs

As noted earlier, as funding for the two Section 8 programs has increased, funding for all other HUD programs has decreased, particularly, but not limited to, funding for HUD's two largest block grant programs: HOME and CDBG. This dynamic may be attributable, in part, to the way the different programs are perceived by funders. Unlike the Section 8 voucher program, where a potential cut in funding can easily translate into a specified number of families losing their assistance, the direct implications of cutting funding for many of the other HUD programs—particularly broad-purpose block grant programs—may be less clear, given that these programs can fund a range of purposes.22 This perception, to the extent it continues, may make the remaining HUD programs more vulnerable to future funding reductions in a limited funding environment.

If there is pressure to limit discretionary spending, federal policymakers may re-evaluate HUD's programs and activities and consider cost-saving program reforms. Such reforms may include program eliminations (as has been proposed in the budget requests of the Trump Administration) or consolidations. Program consolidations may include proposals to merge programs considered duplicative23 or proposals to expand the role or purposes of block grant programs to absorb existing or new programs or activities.24

Future of FHA

As noted earlier, increases in the amount of offsets available from FHA receipts may have served to shield appropriations for HUD programs from deeper cuts in recent years. However, the future of FHA receipts is uncertain. FHA's receipts are impacted by a variety of factors, including the fees FHA charges, the credit quality of the loans insured, and the volume of FHA's business. These factors, in turn, are affected by both policy decisions as well as things that are largely outside the role of policymakers, such as market conditions.

Part of the reason FHA has generated such large surplus receipts in recent years is because its business grew, in part because tighter credit availability in response to the 2007-2009 recession and downturn in housing markets led more home buyers to use FHA. FHA's market share has decreased somewhat since that time, as mortgage credit markets loosened, and could decrease further in the future due to economic conditions or policy changes. Similarly, due in part to tightened credit availability during the housing market downturn, FHA began insuring more loans made to borrowers with better credit profiles during this time period. To the extent that FHA returns to serving a higher share of borrowers with lower credit scores or other riskier attributes, estimates of future loan performance might not be as strong and FHA offsetting receipts could consequently decrease.

Also, both Congress and the past several Administrations have expressed interest in revisiting the role of the federal government in U.S. mortgage markets. Future reforms could serve to shrink the role of FHA, thus shrinking its offsetting receipts, or could allow FHA to keep some portion of its offsetting receipts to use for technology or other administrative needs, presumably reducing the amount that would be available to offset the rest of the HUD budget. Finally, some budget experts and policymakers have proposed requiring the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to change the way that it calculates the costs of FHA and other federal credit programs in the budget.25 While the details of the accounting change are complicated, it is generally understood that this change would mean that FHA would generate fewer offsetting receipts, and it could end up needing regular appropriations.26 Any of these changes to FHA and any resulting reduction in offsetting receipts could increase pressure to further reduce appropriations for HUD's programs and activities if discretionary spending limits remain.

Appendix. Data

|

FY 02 |

FY 03 |

FY 04 |

FY 05 |

FY 06 |

FY 07 |

FY 08 |

FY 09 |

FY 10 |

FY 11 |

FY 12 |

FY 13a |

FY 14 |

FY 15 |

FY 16 |

FY 17 |

FY 18 |

FY 19 |

|

|

Regular Appropriationsb |

34.3 |

36.1 |

37.9 |

37.0 |

37.7 |

38.8 |

40.7 |

42.1 |

47.0 |

45.3 |

43.6 |

42.4 |

45.5 |

45.4 |

47.0 |

48.1 |

52.7 |

53.8 |

|

Section 8 Totalc |

15.6 |

17.1 |

19.3 |

20.1 |

20.5 |

21.9 |

22.8 |

23.3 |

26.7 |

27.6 |

27.6 |

26.8 |

29.1 |

29.0 |

30.2 |

31.1 |

33.5 |

34.3 |

|

TBRA |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

14.8 |

15.4 |

15.9 |

16.4 |

16.2 |

18.2 |

18.4 |

18.3 |

18.0 |

19.2 |

19.3 |

19.6 |

20.3 |

22.0 |

22.6 |

|

PBRA |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

5.3 |

5.0 |

6.0 |

6.4 |

7.1 |

8.6 |

9.3 |

9.3 |

8.9 |

9.9 |

9.7 |

10.6 |

10.8 |

11.5 |

11.7 |

|

All Other HUD Programs |

18.7 |

19.0 |

18.6 |

16.9 |

17.3 |

16.9 |

17.9 |

18.7 |

20.3 |

17.6 |

16.0 |

15.6 |

16.4 |

16.3 |

16.7 |

16.9 |

19.2 |

19.4 |

|

CDBG Formula Grants |

4.3 |

4.3 |

4.3 |

4.1 |

3.7 |

3.7 |

3.6 |

3.6 |

3.9 |

3.3 |

2.9 |

2.2 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

3.1 |

3.1 |

3.4 |

3.4 |

|

HOME Formula Grants |

1.7 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.6 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

|

Offsets |

-3.0 |

-3.4 |

-3.5 |

-2.9 |

-2.1 |

-1.3 |

-1.0 |

-0.7 |

-0.9 |

-4.1 |

-5.8 |

-11.2 |

-12.6 |

-9.7 |

-8.7 |

-9.2 |

-10.1 |

-9.6 |

|

FHA Offsetting Receiptsd |

2.5 |

3.0 |

3.1 |

2.5 |

1.6 |

0.7 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.1 |

3.4 |

5.2 |

10.4 |

11.8 |

8.9 |

7.8 |

8.0 |

8.3 |

7.6 |

|

Rescissionse |

-2.0 |

-1.7 |

-3.2 |

-2.3 |

-2.1 |

-1.7 |

-2.0 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

-0.4 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Emergency Appropriations |

2.8 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

17.1 |

0.0 |

10.0 |

13.7 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

15.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

28.0 |

4.1 |

|

Total Regular Net Budget Authority |

29.4 |

31.0 |

31.2 |

31.8 |

33.6 |

35.8 |

37.7 |

41.3 |

46.1 |

41.1 |

37.3 |

31.2 |

32.8 |

35.6 |

38.3 |

38.8 |

42.7 |

44.2 |

|

Total Net Budget Authority (Inc. Emergency) |

32.2 |

31.0 |

31.2 |

31.9 |

50.7 |

35.8 |

47.7 |

55.0 |

46.2 |

41.1 |

37.4 |

46.4 |

32.8 |

35.6 |

38.6 |

39.2 |

70.7 |

48.3 |

Source: CRS analysis of congressional funding data contained in conference reports accompanying annual appropriations acts.

a. FY2013 figures reflect the reductions resulting from the March 1, 2013, sequestration ordered by the Office of Management and Budget, under the terms of the Budget Control Act of 2011, as amended. The source for FY2013 post-sequestration figures is a table provided by HUD.

b. Figures represent regular appropriations, not reduced for rescissions or offsets and not including emergency appropriations.

c. Figures for Section 8 include both tenant-based and project-based rental assistance, including advance appropriations available in the fiscal year, and are reduced for rescissions of funding from prior advance appropriations, but not rescissions of prior-year unobligated balances. Beginning in FY2014, funding for the Family Self Sufficiency program, which was previously funded as a set-aside within the TBRA account, is included with "All Other HUD Programs."

d. Figures reflect congressional estimates for FHA receipts at the time of enactment of annual appropriations legislation.

e. Totals include rescissions of prior years' funding, not rescissions of current year funding, such as rescissions of prior-year advance appropriations.