Introduction

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is an international organization that administers the trade rules and agreements negotiated by its 164 members to eliminate trade barriers and create nondiscriminatory rules to govern trade. It also serves as an important forum for resolving trade disputes. The United States was a major force behind the establishment of the WTO in 1995 and the rules and agreements that resulted from the Uruguay Round of multilateral trade negotiations (1986-1994). The WTO encompassed and expanded on the commitments and institutional functions of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which was established in 1947 by the United States and 22 other nations. Through the GATT and WTO, the United States and other countries sought to establish a more open, rules-based trading system in the postwar era, with the goal of fostering international economic cooperation, stability, and prosperity worldwide. Today, the vast majority of world trade, approximately 98%, takes place among WTO members.

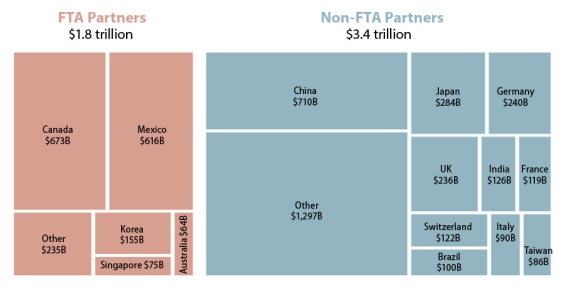

The evolution of U.S. leadership in the WTO and the institution's future agenda have been of interest to Congress. The terms set by the WTO agreements govern the majority of U.S. trading relationships. Some 65% of U.S. global trade is with countries that do not have free trade agreements (FTAs) with the United States, including China, the European Union (EU), India, and Japan, and thus rely on the terms of WTO agreements. Congress has recognized the WTO as the "foundation of the global trading system" within U.S. trade legislation and plays a direct legislative and oversight role over WTO agreements.1 U.S. FTAs also build on core WTO agreements. While the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) represents the United States at the WTO, Congress holds constitutional authority over foreign commerce and establishes U.S. trade negotiating objectives and principles and implements U.S. trade agreements through legislation. U.S. priorities and objectives for the GATT/WTO are reflected in trade promotion authority (TPA) legislation since 1974. Congress also has oversight of the USTR and other executive branch agencies that participate in WTO meetings and enforce WTO commitments.

The WTO's effectiveness as a negotiating body for broad-based trade liberalization has come under intensified scrutiny, as has its role in resolving trade disputes. The WTO has often struggled to reach consensus over issues that can place developed against developing country members (such as agricultural subsidies, industrial goods tariffs, and intellectual property rights protection). It has also struggled to address newer trade barriers, such as digital trade restrictions and the role of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in international commerce, which have become more prominent in the years since the WTO was established. Global supply chains and advances in technology have transformed global commerce, but trade rules have failed to keep up with the pace of change; since 1995 WTO members have been unable to reach consensus for a new comprehensive multilateral agreement. As a result, many countries have turned to negotiating FTAs with one another outside the WTO to build on core WTO agreements and advance trade liberalization and new rules. Plurilateral negotiations, involving subsets of WTO members rather than all members, are also becoming a more popular forum for tackling newer issues on the global trade agenda.

The most recent round of WTO negotiations, the Doha Round, began in November 2001, but concluded with no clear path forward, leaving multiple unresolved issues after the 10th Ministerial conference in 2015. Efforts to build on current WTO agreements outside of the Doha agenda continue. While WTO members have made some progress toward determining future work plans, no major deliverables or negotiated outcomes were announced at the 11th Ministerial conference in December 2017 and no consensus Ministerial Declaration was released.

Many have concerns that the growing use of protectionist trade policies by developed and developing countries, recent U.S. tariff actions and counterretaliation, and escalating trade disputes between major economies may further strain the multilateral trading system. The WTO is faced with resolving several significant pending disputes, which involve the United States, and resolving debates about the role and procedures of its Appellate Body, which reviews appeals of dispute cases.

In a break from past Administrations' approaches, U.S. officials have expressed doubt over the value of the WTO institution to the U.S. economy and questioned whether leadership in the organization is a benefit or cost to the United States. While USTR Robert Lighthizer acknowledged at the 2017 Ministerial that the WTO is an "important institution" that does an "enormous amount of good," the Trump Administration has expressed skepticism toward multilateral trade deals, including those negotiated within the WTO. In remarks to the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum in November 2017, President Trump stated the following: "Simply put, we have not been treated fairly by the World Trade Organization.... What we will no longer do is enter into large agreements that tie our hands, surrender our sovereignty, and make meaningful enforcement practically impossible."2 President Trump has also at times threatened to withdraw the United States from the WTO. During his United Nations General Assembly remarks in September 2019, President Trump claimed that the WTO "needs drastic change," and criticized China as declining to adopt promised reforms following WTO accession.3 In addition, amid concerns about "judicial overreach" in WTO dispute findings, the Administration is currently withholding approval for judge appointments to the WTO Appellate Body—a practice that began under the Obama Administration, and a concern shared by some Members of Congress. At the same time, "reform of the multilateral trading system" is a stated trade policy objective of the Trump Administration, and the United States remains engaged in certain initiatives and plurilateral efforts at the WTO.4 While many of the U.S.'s fundamental concerns predate the Trump Administration and are shared by other trading partners, questions remain about U.S. priorities for improving the system.

With growing debate over the role and future direction of the WTO, a number of issues may be of interest to Congress, including the value of U.S. membership and leadership in the WTO, whether new U.S. negotiating objectives or oversight hearings are needed to address prospects for new WTO reforms and rulemaking, and the relevant authorities and the impact of potential WTO withdrawal on U.S. economic and foreign policy interests.

This report provides background history of the WTO, its organization, and current status of negotiations. The report also explores concerns some have regarding the WTO's future direction and key policy issues for Congress.

Background

Following World War II, nations throughout the world, led by the United States and several other developed countries, sought to establish a more open and nondiscriminatory trading system with the goal of raising the economic well-being of all countries. Aware of the role of tit-for-tat trade barriers resulting from the U.S. Smoot-Hawley tariffs in exacerbating the economic depression in the 1930s, including severe drops in world trade, global production, and employment, the countries that met to discuss the new trading system considered open trade as essential for peace and economic stability.5

The intent of these negotiators was to establish an International Trade Organization (ITO) to address not only trade barriers but other issues indirectly related to trade, including employment, investment, restrictive business practices, and commodity agreements. Unable to secure approval for such a comprehensive agreement, however, they reached a provisional agreement on tariffs and trade rules, known as the GATT, which went into effect in 1948.6 This provisional agreement became the principal set of rules governing international trade for the next 47 years, until the establishment of the WTO.

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)

The GATT was neither a formal treaty nor an international organization, but an agreement between governments, to which they were contracting parties. The GATT parties established a secretariat based in Geneva, but it remained relatively small, especially compared to the staffs of international economic institutions created by the postwar Bretton Woods conference—the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. Based on a mission to promote trade liberalization, the GATT became the principal set of rules and disciplines governing international trade.

|

GATT/WTO Principles Most-favored nation (MFN) treatment (also called normal trade relations by the United States). Requires each member country to grant each other member country treatment at least as favorable as it grants to its most-favored trade partner. National treatment. Obligates each country not to discriminate between domestic and foreign products; once an imported product has entered a country, the product must be treated no less favorably than a "like" product produced domestically. |

The core principles and articles of the GATT (which were carried over to the WTO) committed the original 23 members, including the United States, to lower tariffs on a range of industrial goods and to apply tariffs in a nondiscriminatory manner—the so-called most-favored nation or MFN principle (see text box). By having to extend the same benefits and concessions to members, the economic gains from trade liberalization were magnified. Exceptions to the MFN principle are allowed, however, including for preferential trade agreements outside the GATT/WTO covering "substantially" all trade among members and for nonreciprocal preferences for developing countries.7 GATT members also agreed to provide "national treatment" for imports from other members. For example, countries could not establish one set of health and safety regulations on domestic products while imposing more stringent regulations on imports.

Although the GATT mechanism for the enforcement of these rules or principles was generally viewed as largely ineffective, the agreement nonetheless brought about a substantial reduction of tariffs and other trade barriers.8 The eight "negotiating rounds" of the GATT succeeded in reducing average tariffs on industrial products from between 20%-30% to just below 4%, facilitating a 14-fold increase in world trade over its 47-year history (see Table 1).9 When the first round concluded in 1947, 23 nations had participated, which accounted for a majority of global trade at the time. When the Uruguay Round establishing the WTO concluded in 1994, 123 countries had participated and the amount of trade affected was nearly $3.7 trillion. As of the end of 2018, there are 164 WTO members, and trade flows totaled $22.6 trillion in 2017.10

|

Round |

Negotiating |

Major |

|

1947: Geneva, Switzerland |

23 |

|

|

1949: Annecy, France |

13 |

|

|

1950-51: Torquay, UK |

38 |

|

|

1955-56: Geneva |

26 |

|

|

1960-61: Geneva (Dillon) |

26 |

|

|

1964-67: Geneva (Kennedy) |

62 |

|

|

1973-79: Geneva (Tokyo) |

102 |

|

|

1986-1994: Geneva (Uruguay) |

123 |

|

Source: Douglas A. Irwin, Free Trade Under Fire, p. 225, and Stephen D. Cohen, et al., Fundamentals of U.S. Foreign Trade Policy, p. 185.

During the first trade round held in Geneva in 1947, members negotiated a 20% reciprocal tariff reduction on industrial products, and made further cuts in subsequent rounds. The Tokyo Round represented the first attempt to reform the trade rules that had existed unchanged since 1947 by including issues and policies that could distort international trade. As a result, Tokyo Round negotiators established several plurilateral codes dealing with nontariff issues such as antidumping, subsidies, technical barriers to trade, import licensing, customs valuation, and government procurement.11 Countries could choose which, if any, of these codes they wished to adopt. While the United States agreed to all of the codes, the majority of GATT signatories, including most developing countries, chose not to sign the codes.12

The Uruguay Round, which took eight years to negotiate (1986-1994), proved to be the most comprehensive GATT trade round. This round further lowered tariffs in industrial goods and liberalized trade in areas that had eluded previous negotiators, notably agriculture and textiles and apparel. It also extended rules to new areas such as services, trade-related investment measures, and intellectual property rights. It created a trade policy review mechanism, which periodically examines each member's trade policies and practices. Significantly, the Uruguay Round created the WTO as a legal international organization charged with administering a revised and stronger dispute settlement mechanism—a principal U.S. negotiating objective (see text box)—as well as many new trade agreements adopted during the long negotiation. For the most part, the Uruguay Round agreements were accepted as a single package or single undertaking, meaning that all participants and future WTO members were required to subscribe to all of the agreements.13

|

U.S. Trade Negotiating Objectives for Uruguay Round U.S. trade negotiating objectives for the Uruguay Round, as set out by Congress in the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988 (P.L. 100-418), included the following:

|

World Trade Organization

The WTO succeeded the GATT in 1995. In contrast to the GATT, the WTO was created as a permanent organization. But as with the GATT, the WTO secretariat and support staff is small by international standards and lacks independent power. The power to write rules and negotiate future trade liberalization resides specifically with the member countries, and not the WTO director-general (DG) or staff. Thus, the WTO is referred to as a member-driven organization.14

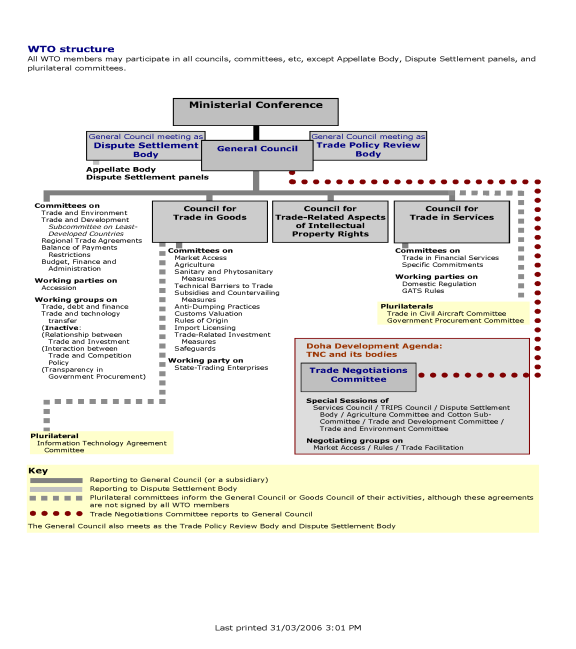

Decisions within the WTO are made by consensus, although majority voting can be used in limited circumstances. The highest-level body in the WTO is the Ministerial Conference, which is the body of political representatives (trade ministers) from each member country (Figure 1). The body that oversees the day-to-day operations of the WTO is the General Council, which consists of a representative from each member country. Many other councils and committees deal with particular issues, and members of these bodies are also national representatives.

In general, the WTO has three broad functions: administering the rules of the trading system; establishing new rules through negotiations; and resolving disputes between member states.

Administering Trade Rules

The WTO administers the global rules and principles negotiated and signed by its members. The main purpose of the rules is "to ensure that trade flows as smoothly, predictably, and freely as possible."15 WTO rules and agreements are essentially contracts that bind governments to keep their trade policies within agreed limits. A number of fundamental principles guide WTO rules.

In general, as with the GATT, these key principles are nondiscrimination and the notion that freer trade through the gradual reduction of trade barriers strengthens the world economy and increases prosperity. The WTO agreements apply the GATT principles of nondiscrimination as discussed above: MFN treatment and national treatment. The trade barriers concerned include tariffs, quotas, and a growing range of nontariff measures, such as product standards, food safety measures, subsidies, and discriminatory domestic regulations. The fundamental principle of reciprocity is also behind members' aim of "entering into reciprocal and mutually advantageous arrangements directed to the substantial reduction of tariffs and other barriers to trade and to the elimination of discriminatory treatment in international trade relations."16

Transparency is another key principle of the WTO, which aims to reduce information asymmetry in markets, ensure trust, and, therefore, foster greater stability in the global trading system. Transparency commitments are incorporated into individual WTO agreements. Active participation in various WTO committees also aims to ensure that agreements are monitored and that members are held accountable for their actions. For example, members are required to publish their trade practices and policies and notify new or amended regulations to WTO committees. Regular trade policy reviews of each member's trade policies and practices provide a deeper dive into an economy's implementation of its commitments—see "Trade Policy Review Mechanism (Annex 3)."17 In addition, the WTO's annual trade monitoring report takes stock of trade-restrictive and trade-facilitating measures of the collective body of WTO members.

|

|

Source: WTO, 2006, https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/organigram_e.pdf. |

While opening markets can encourage competition, innovation, and growth, it can also entail adjustments for workers and firms. Trade liberalization can also be more difficult for the least-developed countries (LDCs) and countries transitioning to market economies. WTO agreements thus allow countries to lower trade barriers gradually. Developing countries and sensitive sectors in particular are usually given longer transition periods to fulfill their obligations; developing countries make up about two-thirds of the WTO membership—WTO members self-designate developing country status.18 The WTO also supplements this so-called "special and differential" treatment (SDT) for developing countries with trade capacity-building measures to provide technical assistance and help implement WTO obligations, and with permissions for countries to extend nonreciprocal, trade preference programs.

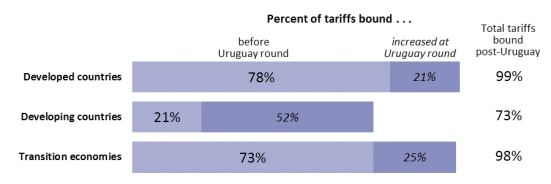

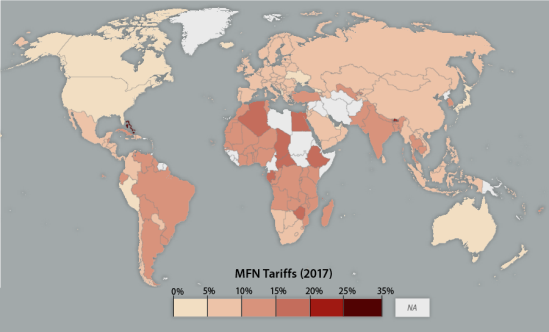

In WTO parlance, when countries agree to open their markets further to foreign goods and services, they "bind" their commitments or agree not to raise them. For goods, these bindings amount to ceilings on tariff rates. A country can change its bindings, but only after negotiating with its trading partners, which could entail compensating them for loss of trade. As shown in Figure 2, one of the achievements of the Uruguay Round was to increase the amount of trade under binding commitments. Bound tariff rates are not necessarily the rates WTO members apply in practice to imports from trading partners; so-called applied MFN rates can be lower than bound rates, as reflected in tariff reductions under the GATT. Figure 3 shows average applied MFN tariffs worldwide. In 2017, the United States simple average MFN tariff was 3.4%.

A key issue in the Doha Round for the United States was lowering major developing countries' relatively high bound tariffs to below their applied rates in practice to achieve commercially meaningful new market access.

|

|

Source: Data from WTO, Understanding the WTO: Basics, http://www.wto.org. Created by CRS. Notes: Percentages reflect shares of total tariff lines, but are not trade-weighted. The Uruguay Round was conducted from 1986 to 1994. |

|

|

Source: WTO, 2017, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/tariffs_e/tariff_data_e.htm. Created by CRS. |

Promising not to raise a trade barrier can have a significant economic effect because the promise provides traders and investors certainty and predictability in the commercial environment. A growing body of economic literature suggests certainty in the stability of tariff rates may be just as important for increasing global trade as reduction in trade barriers.19 This proved particularly important during the 2009 global economic downturn. Unlike in the 1930s, when countries reacted to slumping world demand by raising tariffs and other trade barriers, the WTO reported that its 153 members (at the time), accounting for 90% of world trade, by and large did not resort to protectionist measures in response to the crisis.20

The promotion of fair and undistorted competition is another important principle of the WTO. While the WTO is often described as a "free trade" organization, numerous rules are concerned with ensuring transparent and nondistorted competition. In addition to nondiscrimination, MFN treatment and national treatment concepts aim to promote "fair" conditions of trade. WTO rules on subsidies and antidumping in particular aim to promote fair competition in trade through recourse to trade remedies, or temporary restriction of imports, in response to alleged unfair trade practices—see "Trade Remedies."21 For example, when a foreign company receives a prohibited subsidy for exporting as defined in WTO agreements, WTO rules allow governments to impose duties to offset any unfair advantage found to cause injury to their domestic industries.

The scope of the WTO is broader than the GATT because, in addition to goods, it administers multilateral agreements on agriculture, services, intellectual property, and certain trade-related investment measures. These newer rules in particular are forcing the WTO and its dispute settlement system to deal with complex issues that go beyond tariff border measures.

Establishing New Rules and Trade Liberalization through Negotiations

As the GATT did for 47 years, the WTO provides a negotiating forum where members reduce barriers and try to sort out their trade problems. Negotiations can involve a few countries, many countries, or all members. As part of the post-Uruguay Round agenda, negotiations covering basic telecommunications and financial services were completed under the auspices of the WTO in 1997. Selected WTO members also negotiated deals to eliminate tariffs on certain information technology products and improve rules and procedures for government procurement. A recent significant accomplishment was the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement in 2017, addressing customs and logistics barriers.

The latest round of multilateral negotiations, the Doha Development Agenda (DDA), or Doha Round, launched in 2001, has achieved limited progress to date, as the agenda proved difficult and contentious. Despite a lack of consensus on its future, many view the round as effectively over.22 The negotiations stalled over issues such as reducing domestic subsidies and opening markets further in agriculture, industrial tariffs, nontariff barriers, services, intellectual property rights, and SDT for developing countries. The negotiations exposed fissures between developed countries, led by the United States and the EU, on the one hand, and developing countries, led by China, Brazil, and India, on the other hand, who have come to play a more prominent role in global trade.

The inability of countries to achieve the objectives of the Doha Round prompted many to question the utility of the WTO as a negotiating forum, as well as the practicality of conducting a large-scale negotiation involving 164 participants with consensus and the single undertaking as guiding principles. At the same time, many proposals have been advanced for moving forward from Doha and making the WTO a stronger forum for negotiations in the future.23 (See "Policy Issues and Future Direction.")

The WTO arguably has been more successful in the negotiation of discrete items to which not all parties must agree or be bound (see "Plurilateral Agreements (Annex 4)"). Some view these plurilaterals as a more promising negotiating approach for the WTO moving forward given their flexibility, as they can involve subsets of more "like-minded" partners and advance parts of the global trade agenda. Some experts have raised concerns, however, that this approach could lead to "free riders"—those who benefit from the agreement but do not make commitments—for agreements on an MFN basis, or otherwise, could isolate some countries who do not participate and may face new trade restrictions or disadvantages as a result. Others argue that only though the single undertaking approach to negotiations can there be trade-offs that are sufficient to bring all members on board.

Resolving Disputes

The third function of the WTO is to provide a mechanism to enforce its rules and settle trade disputes. A central goal of the United States during the Uruguay Round negotiations was to strengthen the dispute settlement mechanism that existed under the GATT. While the GATT's process for settling disputes between member countries was informal, ad hoc, and voluntary, the WTO dispute settlement process is more formalized and enforceable.24 Under the GATT, panel proceedings could take years to complete; any defending party could block an unfavorable ruling; failure to implement a ruling carried no consequence; and the process did not cover all the agreements. Under the WTO, there are strict timetables—though not always followed—for panel proceedings; the defending party cannot block rulings; there is one comprehensive dispute settlement process covering all the agreements; and the rulings are enforceable. WTO adjudicative bodies can authorize retaliation if a member fails to implement a ruling or provide compensation. Yet, under both systems, considerable emphasis is placed on having the member countries attempt to resolve disputes through consultations and negotiations, rather than relying on formal panel rulings. See "Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU)" for more detail on WTO procedures and dispute trends.

The United States and the WTO

The statutory basis for U.S. membership in the WTO is the Uruguay Round Agreements Act (URAA, P.L. 103-465), which approved the trade agreements resulting from the Uruguay Round. The legislation contained general provisions on

- approval and entry into force of the Uruguay Round Agreements, and the relationship of the agreements to U.S. laws (Section 101 of the act);

- authorities to implement the results of current and future tariff negotiations (Section 111 of the act);

- oversight of activities of the WTO (Sections 121-130 of the act);

- procedures regarding implementation of dispute settlement proceedings affecting the United States (Section 123 of the act);

- objectives regarding extended Uruguay Round negotiations;

- statutory modifications to implement specific agreements, including the following:

- Antidumping Agreement;

- Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (ASCM);

- Safeguards Agreement;

- Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA);

- Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) (product standards);

- Agreement on Agriculture; and

- Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).

U.S. priorities and objectives for the GATT/WTO have been reflected in various trade promotion authority (TPA) legislation since 1974. For example, the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988 specifically contained provisions directing U.S. negotiators to negotiate disciplines on agriculture, dispute settlement, intellectual property, trade in services, and safeguards, among others, that resulted in WTO agreements in the Uruguay Round (see text box above). The Trade Act of 2002 provided U.S. objectives for the Doha Round, including seeking to expand commitments on e-commerce and clarifications to the WTO dispute settlement system. The 2015 TPA, perhaps reflecting the impasse of the Doha Round, was more muted, seeking full implementation of existing agreements, enhanced compliance by members with their WTO obligations, and new negotiations to extend commitments to new areas.25

Section 125(b) of the URAA sets procedures for congressional disapproval of WTO participation. It specifies that Congress's approval of the WTO agreement shall cease to be effective "if and only if" Congress enacts a joint resolution calling for withdrawal. Congress may vote every five years on withdrawal; resolutions were introduced in 2000 and 2005, however neither passed.26 The next possible consideration of such a resolution would be in 2020.

WTO Agreements

The WTO member-led body negotiates, administers, and settles disputes for agreements that cover goods, agriculture, services, certain trade-related investment measures, and intellectual property rights, among other issues. The WTO core principles are enshrined in a series of trade agreements that include rules and commitments specific to each agreement, subject to various exceptions. The GATT/WTO system of agreements has expanded rulemaking to several areas of international trade, but does not extensively cover some key areas, including multilateral investment rules, trade-related labor or environment issues, and emerging issues like digital trade or the commercial role of state-owned enterprises.

Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization

The Marrakesh Agreement is the umbrella agreement under which the various agreements, annexes, commitment schedules, and understandings reside. The Marrakesh Agreement itself created the WTO as a legal international organization and sets forth its functions, structure, secretariat, budget procedures, decisionmaking, accession, entry-into-force, withdrawal, and other provisions. The Agreement contains four annexes. The three major substantive areas of commitments undertaken by the members are contained in Annex 1.

Multilateral Agreement on Trade in Goods (Annex 1A)

The Multilateral Agreement on Trade in Goods establishes the rules for trade in goods through a series of sectoral or issue-specific agreements (see Table 2). Its core is the GATT 1994, which includes GATT 1947, the amendments, understanding, protocols, and decisions of the GATT from 1947 to 1994, cumulatively known as the GATT-acquis, as well as six Understandings on Articles of the GATT 1947 negotiated in the Uruguay Round. In addition to clarifying the core WTO principles, each agreement contains sector- or issue-specific rules and principles. The schedule of commitments identifies each member's specific binding commitments on tariffs for goods in general, and combinations of tariffs and quotas for some agricultural goods. Through a series of negotiating rounds, members agreed to the current level of trade liberalization (see Figure 2 above).

|

Agreement on |

Agreement on Implementation of Article VI (Anti-dumping) |

Agreement on Import Licensing Procedures |

Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) |

|

Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS) |

Agreement on Implementation of Article VII (Customs Valuation) |

Agreement on Subsidies |

Understanding on Rules |

|

Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) |

Agreement on Preshipment Inspection |

Agreement on |

Agreement on Trade |

|

Agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures (TRIMS) |

Agreement on Rules of Origin (ROO) |

General Agreement |

Agreement on |

In the last four rounds of negotiations, WTO members aimed to expand international trade rules beyond tariff reductions to tackle barriers in other areas. For example, agreements on technical barriers to trade (TBT) and sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures aim to protect a country's rights to implement domestic regulations and standards, while ensuring they do not discriminate against trading partners or unnecessarily restrict trade.27

Agreement on Agriculture (AoA)

The Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) includes rules and commitments on market access and disciplines on certain domestic agricultural support programs and export subsidies. Its objective was to provide a framework for WTO members to reform certain aspects of agricultural trade and domestic farm policies to facilitate more market-oriented and open trade.28 Regarding market access, members agreed not to restrict agricultural imports by quotas or other nontariff measures, converting them to tariff-equivalent levels of protection, such as tariff-rate quotas—a process called "tariffication." Developed countries committed to cut tariffs (or out-of-quota tariffs, those tariffs applied to any imports above the agreed quota threshold) by an average of 36% in equal increments over six years; developed countries committed to 24% tariff cuts over 10 years. Special safeguards to temporarily restrict imports were permitted in certain events, such as falling prices or surges of imports.

The AoA also categorizes and restricts agricultural domestic support programs according to their potential to distort trade. Members agreed to limit and reduce the most distortive forms of domestic subsidies over 6 to 10 years, referred to as "amber box" subsidies and measured by the Aggregate Measure of Support (AMS) index.29 Subsidies considered to cause minimal distortion on production and trade are not subject to spending limits and exempted from obligations as "green box" and "blue box" subsidies or under de minimis (below a certain threshold) or SDT provisions. In addition, export subsidies were to be capped and subject to incremental reductions, both by value and quantity of exports covered. A so-called "peace" clause protected members using subsidies that comply with the agreement from being challenged under other WTO agreements, such as through use of countervailing duties; the clause expired after nine years in 2003. Members are required to regularly submit notifications on the implementation of AoA commitments—though some countries, including the United States, have raised concerns that these requirements are not abided by in a consistent fashion.

Further agricultural trade reform was a major priority under the Doha Round, but negotiations have seen limited progress to date (see "Ongoing WTO Negotiations"). However, in 2015, members reached an agreement to fully eliminate export subsidies for agriculture.

Trade-Related Investment Measures (TRIMS)

The framework of the GATT did not address the growing linkages between trade and investment. During the Uruguay Round, the Agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures (TRIMS) was drafted to address certain investment measures that may restrict and distort trade. The agreement did not address the regulation or protection of foreign investment, but focused on investment measures that may violate basic GATT disciplines on trade in goods, such as nondiscrimination. Specifically, members committed not to apply any TRIM that is inconsistent with provisions on national treatment or a prohibition of quantitative restrictions on imports or exports. TRIMS includes an annex with an illustrative list of prohibited measures, such as local content requirements—requirements to purchase or use products of domestic origin. The agreement also includes a safeguard measure for balance of payment difficulties, which permits developing countries to temporarily suspend TRIMS obligations.

While TRIMS and other WTO agreements, such as the GATS (see below), include some provisions pertaining to investment, the lack of comprehensive multilateral rules on investment led to several efforts under the Doha Round to consider proposals, which to date have been unfruitful (see "Future Negotiations"). In December 2017, 70 WTO members announced plans to begin new discussions on developing a multilateral framework on investment facilitation, in part to complement the successful negotiation of rules on trade facilitation.

General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) (Annex 1B)

The GATT agreements focused solely on trade in goods, excluding services. Services were eventually covered in the GATS as a result of the Uruguay Round agreements.30 The GATS provides the first and only multilateral framework of principles and rules for government policies and regulations affecting trade in services. It has served as the foundation on which rules in other trade agreements on services are based.

The services trade agenda is complex due to the characteristics of the sector. "Services" refers to a growing range of economic activities, such as audiovisual, construction, computer and related services, express delivery, e-commerce, financial, professional (e.g., accounting and legal services), retail and wholesaling, transportation, tourism, and telecommunications. Advances in information technology and the growth of global supply chains have reduced barriers to trade in services, expanding the services tradable across national borders. But liberalizing trade in services can be more complex than for goods, since the impediments faced by service providers occur largely within the importing country, as so-called "behind the border" barriers, some in the form of government regulations. While the right of governments to regulate service industries is widely recognized as prudent and necessary to protect consumers from harmful or unqualified providers, a main focus of WTO members is whether these regulations are applied to foreign service providers in a discriminatory and unnecessarily trade restrictive manner that limits market access.

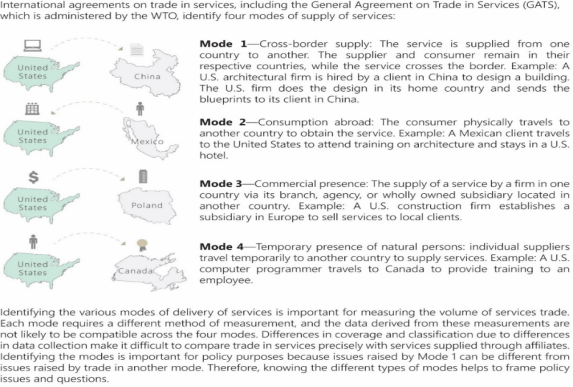

The GATS contains multiple parts, including definition of scope (excluding government-provided services); principles and obligations, including MFN treatment and transparency; market access and national treatment obligations; annexes listing exceptions that members take to MFN treatment; as well as various technical elements. Members negotiated GATS on a positive list basis, which means that the commitments only apply to those services and modes of delivery listed in each member's schedule of commitments.31 WTO members adopted a system of classifying four modes of delivery for services to measure trade in services and classify government measures that affect trade in services, including cross-border supply, consumption abroad, commercial presence, and temporary presence of natural persons (Figure 4). Under GATS, unless a member country has specifically committed to open its market to suppliers in a particular service, the national treatment and market access obligations do not apply.

In addition to the GATS, some members made specific sectoral commitments in financial services and telecommunications. Negotiations to expand these commitments were later folded into the broader services negotiations.

WTO members aimed to update GATS provisions and market access commitments as part of the Doha Round. Several WTO members have since submitted revised offers of services liberalization, but in the view of the United States and others the talks have not yielded adequate offers of improved market access (see "Future Negotiations"). Given the lack of progress, in 2013, 23 WTO members, including the United States, representing approximately 70% of global services trade, launched negotiations of a services-specific plurilateral agreement.32 Although outside of the WTO structure, participants designed the Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) negotiations in a way that would not preclude a concluded agreement from someday being brought into the WTO. TiSA talks were initially led by Australia and the United States, but have since stalled; the Trump Administration has not stated a formal position on TiSA.

|

Figure 4. Four Modes of Service Delivery and Hypothetical Examples |

|

|

Source: CRS based on WTO. |

Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) (Annex 1C)

The TRIPS Agreement marked the first time multilateral trade rules incorporated intellectual property rights (IPR)—legal, private, enforceable rights that governments grant to inventors and artists to encourage innovation and creative output.33 Like the GATS, TRIPS was negotiated as part of the Uruguay Round and was a major U.S. objective for the round.

The TRIPS Agreement sets minimum standards of protection and enforcement for IPR. Much of the agreement sets out the extent of coverage of the various types of intellectual property, including patents, copyrights, trademarks, trade secrets, and geographical indications. TRIPS includes provisions on nondiscrimination and on enforcement measures, such as civil and administrative procedures and remedies. IPR disputes under the agreement are also subject to the WTO dispute settlement mechanism.

The TRIPS Agreement's newly placed requirements on many developing countries elevated the debate over the relationship between IPR and development. At issue is the balance of rights and obligations between protecting private right holders and securing broader public benefits, such as access to medicines and the free flow of data, especially in developing countries. TRIPS includes flexibilities for developing countries allowing longer phase-in periods for implementing obligations and, separately, for pharmaceutical patent obligations—these were subsequently extended for LDCs until January 2033 or until they no longer qualify as LDCs, whichever is earlier.34 The 2001 WTO "Doha Declaration" committed members to interpret and implement TRIPS obligations in a way that supports public health and access to medicines.35 In 2005, members agreed to amend TRIPS to allow developing and LDC members that lack production capacity to import generic medicines from third country producers under "compulsory licensing" arrangements.36 The amendment entered into force in January 2017.37

Trade Remedies

While WTO agreements uphold MFN principles, they also allow exceptions to binding tariffs in certain circumstances. The WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (ASCM), Agreement on Safeguards, and articles in the GATT, commonly known as the Antidumping Agreement, allow for trade remedies in the form of temporary measures (e.g., primarily duties or quotas) to mitigate the adverse impact of various trade practices on domestic industries and workers. These include actions taken against dumping (selling at an unfairly low price) or to counter certain government subsidies, and emergency measures to limit "fairly"-traded imports temporarily, designed to "safeguard" domestic industries.

Supporters of trade remedies view them as necessary to shield domestic industries and workers from unfair competition and to level the playing field. Other domestic constituents, including some importers and downstream consuming industries, voice concern that antidumping (AD) and countervailing duty (CVD) actions can serve as disguised protectionism and create inefficiencies in the world trading system by raising prices on imported goods. How trade remedies are applied to imports has become a major source of disputes under the WTO (see below).

The United States has enacted trade remedy laws that conform to the WTO rules:38

- U.S. antidumping laws (19 U.S.C. §1673 et seq.) provide relief to domestic industries that have been, or are threatened with, the adverse impact of imports sold in the U.S. market at prices that are shown to be less than fair market value. The relief provided is an additional import duty placed on the dumped imports.

- U.S. countervailing duty laws (19 U.S.C. §1671 et seq.) give similar relief to domestic industries that have been, or are threatened with, the adverse impact of imported goods that have been subsidized by a foreign government or public entity, and can therefore be sold at lower prices than U.S.-produced goods. The relief provided is a duty placed on the subsidized imports.

- U.S. safeguard laws give domestic industries relief from import surges of goods; no allegation of "unfair" practices is needed to launch a safeguard investigation. Although used less frequently than AD/CVD laws, Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974 (19 U.S.C. §2251 et seq.), is designed to give domestic industry the opportunity to adjust to import competition and remain competitive. The relief provided is generally a temporary import duty and/or quota. Unlike AD/CVD, safeguard laws require presidential action for relief to be put into effect.

Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU) (Annex 2)

The dispute settlement system, often called the "crown jewel" of the WTO, has been considered by some observers to be one of the most important successes of the multilateral trading system.39 WTO agreements contain provisions that are either binding or nonbinding. The WTO Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes—Dispute Settlement Understanding or DSU—provides an enforceable means for WTO members to resolve disputes arising under the binding provisions.40 The DSU commits members not to determine violations of WTO obligations or impose penalties unilaterally, but to settle complaints about alleged violations under DSU rules and procedures.

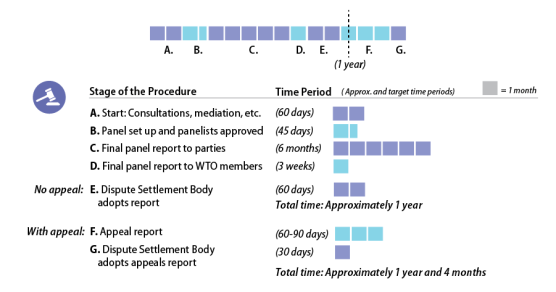

The Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) is a plenary committee of the WTO, which oversees the panels and adopts the recommendation of a dispute settlement panel or Appellate Body (AB) panel. Panels are composed of three (or five in complex cases) panelists—not citizens of the members involved—chosen through a roster of "well qualified governmental and/or non-governmental individuals" maintained by the Secretariat. WTO members must first attempt to settle a dispute through consultations, but if these fail, a member seeking to initiate a dispute may request that a panel examine and report on its complaint. A respondent party is able to block the establishment of a panel at the DSB once, but if the complainant requests its establishment again at a subsequent meeting of the DSB, a panel is established. At its conclusion, the panel recommends a decision to the DSB that it will adopt unless all parties agree to block the recommendation. The DSU sets out a timeline of one year for the initial resolution of disputes (see Figure 5); however, cases are rarely resolved in this timeframe.

The DSU also provides for AB review of panel reports in the event a panel decision is appealed. The AB is composed of seven rotating panelists serving four-year terms, with the possibility of a one-term reappointment. According to the DSU, appeals are to be limited to questions of law or legal interpretation developed by the panel in the case (Article 17.6). The AB is to make a recommendation and the DSB is to ratify that recommendation within 120 days of the ratification of the initial panel report, but again, such timely resolution rarely occurs. The United States has raised several issues regarding the practices of the AB and has blocked the appointments of several judges—for more on the current debate, see "Proposed Institutional Reforms."

Following the adoption of a panel or appellate report, the DSB oversees the implementation of the findings. The losing party is then to propose how it is to bring itself into compliance "within a reasonable period of time" with the DSB-adopted findings. A reasonable period of time is determined by mutual agreement with the DSB, among the parties, or through arbitration. If a dispute arises over the manner of implementation, the DSB may form a panel to judge compliance. If a party declines to comply, the parties negotiate over compensation pending full implementation. If there is still no agreement, the DSB may authorize retaliation in the amount of the determined cost of the offending party's measure to the aggrieved party's economy. There have been some calls for reform of the dispute settlement system to deal with the procedural delays and new strains on the system, including the growing volume and complexity of cases.

Filing a dispute settlement case provides a way for countries to resolve disputes through a legal process and to do so publicly, signaling to domestic and international constituents the need to address outstanding issues. Dispute settlement procedures can serve as a deterrent for countries considering not abiding by WTO agreements, and rulings can help build a body of case law to inform countries when they implement new regulatory regimes or interpret WTO agreements.

That said, WTO agreements and decisions of panels are not self-executing and cannot directly modify U.S. law. If a case is brought against the United States and the panel renders an adverse decision, the United States would be expected to remove the offending measure within a reasonable period of time or face the possibility of either paying compensation to the complaining member or becoming subject to sanctions, often in the form of higher tariffs on imports of certain U.S. products.

As of the beginning of October 2019, the WTO has initiated 590 disputes on behalf of its members and issued more than 350 rulings, with 2018 marking its most active year to date.41 Nearly two-thirds of WTO members have participated in the dispute settlement system. Not all complaints result in formal panel proceedings; about half were resolved during consultations. The complainants usually win their cases, in large part because they initiate disputes that they have a high chance of winning. In the words of WTO Director-General (DG) Roberto Azevêdo, the widespread use of the DS system is evidence it "enjoys tremendous confidence among the membership, who value it as a fair, effective, efficient mechanism to solve trade problems."42

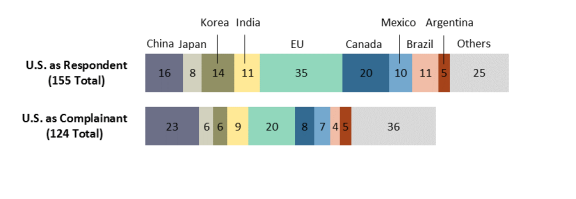

The United States is an active user of the DS system. Among WTO members, the United States has been a complainant in the most dispute cases since the system was established in 1995, initiating 124 disputes, followed by the EU with 102 disputes.43 The two largest targets of complaints initiated by the United States are China and the EU, which, combined, account for more than one-third (Figure 6). The latest summary by USTR reports that among WTO disputes through 2015 the United States largely prevailed on "core issues" in 46 of its complaints and lost in 4.44 Since the report was released, additional cases have been ruled in favor of the United States, including disputes over India's solar energy policies and Indonesia's import licensing requirements. The majority of disputes initiated by the United States between 2016 and 2019 remain in the consultation or panel stages and have not been decided.

|

|

Source: WTO, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/find_dispu_cases_e.htm. Created by CRS. Notes: Does not include cases with U.S. participation as a third party. Dispute count as of October 1, 2019. |

As a respondent in 155 dispute cases since 1995, the United States has also had the most disputes filed against it by other WTO members, followed by the EU (85 disputes) and China (44 disputes). The EU is the largest source of disputes filed against the United States, followed by Canada, China, South Korea, Brazil, and India. A large number of complaints concern U.S. trade remedies, in particular the methodologies used for calculating and imposing antidumping duties on U.S. imports. The latest summary by USTR reports that as a respondent, the United States won on "core issues" in 17 cases and lost in 57 cases through 2015.45 Since then, the WTO has ruled against the United States on certain aspects of complaints related to U.S. trade remedies, including in cases initiated by South Korea, China, Canada, and Turkey.46 The United States has prevailed in other cases, for example in December 2017, a panel ruled in U.S. favor in a case brought by Indonesia over U.S. duties on coated paper imports.47 The DSB has authorized retaliation against the United States for maintaining a measure in violation of WTO rules in just a handful of cases.48 Most recently, in February 2019, a panel authorized South Korea to retaliate in a complaint over U.S. methodology for calculating antidumping duties on South Korean imports of large residential washers.49

Several pending WTO disputes are of significance to the United States. One involves China's complaints over U.S. and EU failure to grant China market economy status (see "China's Accession and Membership"). Other cases involve challenges to the tariff measures imposed by the Trump Administration under U.S. trade laws, including Section 201 (safeguards), Section 232 (national security), and Section 301 ("unfair" trading practices) (Table 3). Nine WTO members, including China, the EU, Canada, and Mexico, initiated separate complaints at the WTO, based on allegations that U.S. Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum imports are inconsistent with WTO rules. In May 2019, the cases involving Canada and Mexico were withdrawn due to a negotiated settlement with the United States.50 Consultations were unsuccessful in resolving the disputes, and panels have been established and composed in the seven remaining cases. Most countries notified their consultation requests pursuant to the Agreement on Safeguards, though some countries also allege that U.S. tariff measures and related exemptions are contrary to U.S. obligations under several provisions of the GATT. Several other WTO members have requested to join the disputes as third parties.

On July 16, 2018, the United States filed its own WTO complaints over retaliatory tariffs imposed by five countries (Canada, China, EU, Mexico, and Turkey) in response to U.S. actions, and in late August, it filed a similar case against Russia.51 Most recently, the United States filed a case against India in July 2019 based on its retaliation. The United States has invoked the so-called national security exception (GATT Article XXI) in defense of its tariffs (see "Key Exceptions under GATT/WTO"), and states that the tariffs are not safeguards as claimed by other countries. By early 2019, the majority of the disputes had entered the panel phase; the United States requested a panel in its case with India in September.

|

Issue |

Complainant country |

Dispute number |

Date Filed / Status |

|

|

SECTION 201 |

||||

|

U.S. safeguard measure on crystalline silicon photovoltaic products |

South Korea |

DS545 |

5/14/18 consultations requested; 9/26/18 panel established |

|

|

China |

DS562 |

8/14/18 consultations requested 8/15/19 panel established |

||

|

U.S. safeguard measure on large residential washers imports |

South Korea |

DS546 |

5/14/18 consultations requested; 9/26/18 panel established; 7/01/19 panel composed |

|

|

SECTION 232 |

||||

|

U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum imports |

China |

DS544 |

4/05/18 consultations requested; 11/21/18 panel established; 01/25/19 panel composed |

|

|

India |

DS547 |

5/18/18 consultations requested; 12/4/18 panel established; 01/25/19 panel composed |

||

|

EU |

DS548 |

6/01/18 consultations requested; 11/21/18 panel established; 01/25/19 panel composed |

||

|

Canada |

DS550 |

6/01/18 consultations requested; 11/21/18 panel established; 05/23/19 settled or terminated (withdrawn, mutually agreed solution) |

||

|

Mexico |

DS551 |

6/05/18 consultations requested; 11/21/18 panel established; 05/28/19 settled or terminated (withdrawn, mutually agreed solution) |

||

|

Norway |

DS552 |

6/12/18 consultations requested; 11/21/18 panel established; 01/25/19 panel composed |

||

|

Russia |

DS554 |

6/29/18 consultations requested; 11/21/18 panel established; 01/25/19 panel composed |

||

|

Switzerland |

DS556 |

7/09/18 consultations requested; 12/4/18 panel established; 01/25/19 panel composed |

||

|

Turkey |

DS564 |

8/15/18 consultations requested; 11/21/18 panel established; 01/25/19 panel composed |

||

|

SECTION 301 |

||||

|

U.S. tariffs on certain Chinese imports |

China |

DS543 |

4/04/18 consultations requested; 1/28/19 panel established; 06/03/19 panel composed |

|

|

China |

DS565 |

8/23/18 consultations requested |

||

Trade Policy Review Mechanism (Annex 3)

Annex 3 sets out the procedures for the regular trade policy reviews that are conducted by the Secretariat to report on the trade policies of the membership. These reviews are carried out by the Trade Policy Review Body (TPRB) and are conducted periodically with the largest economies (United States, EU, Japan, and China) evaluated every three years, the next 16 largest economies every five years, and remaining economies every seven years. These reviews are meant to increase transparency of a country's trade policy and enable a multilateral assessment of the effect of policies on the trading system. These reviews also allow each member country to question specific practices of other members, and may serve as a forum to flag, and possibly avoid, future disputes.

The most recent trade policy review of China occurred in July 2018.52 During the review members noted and commended some recent initiatives of China to open market access and liberalize its foreign investment regime. Several concerns were also raised, including "the preponderant role of the State in general, and of state-owned enterprises in particular," and "China's support and subsidy policies and local content requirements, including those that may be part of the 2025 [Made in China] plan."53

|

2018 Trade Policy Review of the United States The most recent trade policy review of the United States culminated in December 2018.54 The U.S. government's view of its trade policy and the WTO Secretariat's report on U.S. trade policy were released on November 12, 2018. The Secretariat's report is a factual description of a country's policy and of significant developments since the last review. It does not pass judgement on the consistency of a country's policies with WTO agreements. Subsequently, the TPRB met on December 17-19 to assess the report, pose questions, and allow other members to opine on specific aspects of U.S. policy. In his statement, U.S. Ambassador to the WTO Dennis Shea contended that U.S. trade policy is "steadfastly focused on the national interest including retaining and using US sovereign power to act in defense of that interest." He described U.S. trade policy as resting on five major pillars: "supporting U.S. national security, strengthening the U.S. economy, negotiating better trade deals, aggressive enforcement of U.S. trade laws, and reforming the multilateral trading system."55 While WTO members generally lauded the United States on a free and open trade policy, and recognized its traditional role as a pillar of the multilateral trading system, some countries voiced their displeasure at recent U.S. trade actions. Members took issue with the imposition of tariffs on steel and aluminum as a result of the Section 232 national security determinations; the imposition of Section 301 tariffs on China; increased use of trade remedies; and rising levels of trade-distorting farm subsidies, including the aid package for agricultural producers hit by retaliatory tariffs; as well as perennial irritants, such as Buy American policies and Jones Act maritime and cabotage restrictions.56 According to the EU Ambassador to the WTO Marc Vanheukelen, "the multilateral trading system is in a deep crisis and the United States is in the epicenter for a number of reasons."57 |

Plurilateral Agreements (Annex 4)

Most WTO agreements in force have been negotiated on a multilateral basis, meaning the entire body of WTO members subscribes to them. By contrast, plurilateral agreements are negotiated by a subset of WTO members and often focus on a specific sector. A handful of such agreements supplement the main WTO agreements discussed previously.58

Within the WTO, members have two ways to negotiate on a plurilateral basis, also known as "variable geometry."59 A group of countries can negotiate with one another provided that the group extends the benefits to all other WTO members on an MFN basis—the foundational nondiscrimination principle of the GATT/WTO. Because the benefits of the agreement are to be shared among all WTO members and not just the participants, the negotiating group likely would include those members forming a critical mass of world trade in the product or sector covered by the negotiation in order to avoid the problem of free riders—those countries that receive trade benefits without committing to liberalization. An example of this type of plurilateral agreement granting unconditional MFN is the Information Technology Agreement (ITA), in which tariffs on selected information technology goods were lowered to zero, as negotiated by WTO members comprising more than 90% of world trade in these goods (see below).

A second type of WTO plurilateral is the non-MFN agreement, often referred to as "conditional-MFN." In this type, participants undertake additional obligations among themselves, but do not extend the benefits to other WTO members, unless they directly participate in the agreement. Also known as the "club" approach, non-MFN plurilaterals allow for willing members to address policy issues not covered by WTO disciplines. However, these types of agreements require a waiver from the entire WTO membership to commence negotiations. Some countries are reluctant even to allow other countries to negotiate for fear of being left out, even while not being ready to commit themselves to new disciplines. Yet, according to one commentator, these members are "simply outsmarting themselves" by encouraging more ambitious members to take negotiations out of the WTO.

Government Procurement Agreement

The Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) is an early example of a plurilateral agreement with limited WTO membership—first developed as a code in the 1979 Tokyo Round. As of the end of 2018, 47 WTO members (including the 28 EU member countries and United States) participate in the GPA; non-GPA signatories do not enjoy rights under the GPA.60 The GPA provides market access for various nondefense government projects to contractors of its signatories.61 Each member specifies government entities and goods and services (with thresholds and limitations) that are open to procurement bids by foreign firms of the other GPA members. For example, the U.S. GPA market access schedules of commitments cover 85 federal-level entities and voluntary commitments by 37 states.62

Negotiations to expand the GPA were concluded in March 2012, and a revised GPA entered into force on April 6, 2014. Several countries, including China—which committed to pursuing GPA participation in its 2001 WTO accession process—are in long-pending negotiations to accede to the GPA. South Korea, Moldova, and Ukraine were the latest WTO members to join the GPA in 2016. According to estimates by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), from 2008 to 2012, 8% of total global government expenditures, and approximately one-third of U.S. federal government procurement, was covered by the GPA or similar commitments in U.S. FTAs.63

Information Technology Agreement

Unlike the GPA, the Information Technology Agreement (ITA) is a plurilateral agreement that is applied on an unconditional MFN basis. In other words, all WTO members benefit from the tariff reductions enacted by parties to the ITA regardless of their own participation.64 Originally concluded in 1996 by a subset of WTO members, the ITA provides tariff-free treatment for covered IT products; however, the agreement does not cover services or digital products like software. In December 2015, a group of 51 WTO members, including the United States, negotiated an expanded agreement to cover an additional 201 products and technologies, valued at over $1 trillion in annual global exports.65 Members committed to reduce the majority of tariffs by 2019. In June 2016, the United States initiated the ITA tariff cuts. China began its cuts in mid-September 2016 with plans to reduce tariffs over five to seven years. ITA members are expected to review the agreement's scope in 2018 to determine if additional product coverage is needed.

Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA)

|

Impact of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement According to WTO estimates, global export gains from full implementation of the TFA could range from $750 billion to more than $3.6 trillion dollars per year and, for the 2015-2030 time period, could increase world export growth by 2.7% a year and world GDP growth by over 0.5% a year. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates that TFA implementation could lower the costs of doing trade as much as 12.5%-17.5% globally. |

The Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) is the newest WTO multilateral trade agreement, entering into force on February 22, 2017, and perhaps the lasting legacy of the Doha Round, since it is the only major concluded component of the negotiations.66 The TFA aims to address multiple trade barriers confronted by exporters and importers and reduce trade costs by streamlining, modernizing, and speeding up the customs processes for cross-border trade, as well as making it more transparent. Some analysts view the TFA as evidence that achieving new multilateral agreements is possible and that the design, including special and differential treatment provisions, could serve as a template for future agreements.

The TFA has three sections. The first is the heart of the agreement, containing the main provisions, of which many, but not all, are binding and enforceable. Mandatory articles include requiring members to publish information, including publishing certain items online; issue advance rulings in a reasonable amount of time; and provide for appeals or reviews, if requested.

The second section provides for SDT for developing country and LDC members, allowing them more time and assistance to implement the agreement. The TFA is the first WTO agreement in which members determine their own implementation schedules and in which progress in implementation is explicitly linked to technical and financial capacity. The TFA requires that "donor members," including the United States, provide the needed capacity building and support. Finally, the third section sets institutional arrangements for administering the TFA.

Key Exceptions under GATT/WTO

Under WTO agreements, members generally cannot discriminate among trading partners, though specific market access commitments can vary significantly by agreement and by member. WTO rules permit some broad exceptions, which allow members to adopt trade policies and practices that may be inconsistent with WTO disciplines and principles such as MFN treatment, granting special preferences to certain countries, and restricting trade in certain sectors, provided certain conditions are met. Some of the key exceptions follow.

General exceptions. GATT Article XX grants WTO members the right to take certain measures necessary to protect human, animal, or plant life or health, or to conserve exhaustible natural resources, among other aims. The measures, however, must not entail "arbitrary" or "unjustifiable" discrimination between countries where the same conditions prevail, or serve as "disguised restriction on international trade." GATS Article XIV provides for similar exceptions for trade in services.

National security exception. GATT Article XXI protects the right of members to take any action they consider "necessary for the protection of essential national security interests" as related to (i) fissionable materials; (ii) traffic in arms, ammunition, and implements of war, and such traffic in other goods and materials carried out to supply a military establishment; and (iii) taken in time of war or other emergency in international relations. Similar exceptions relate to trade in services (GATS Article XIV bis) and intellectual property rights (TRIPS Article 73).

More favorable treatment to developing countries. The so-called "enabling clause" of the GATT—called the "Decision on Differential and More Favorable Treatment, Reciprocity and Fuller Participation of Developing Countries" of 1979—enables developed country members to grant differential and more favorable treatment to developing countries that is not extended to other members. For example, this permits granting unilateral and nonreciprocal trade preferences to developing countries under special programs, such as the U.S. Generalized System of Preferences (GSP), and also relates to regional trade agreements outside the WTO (see below).

Exceptions for regional trade agreements (RTAs). WTO countries are permitted to depart from the MFN principle and grant each other more favorable treatment in trade agreements outside the WTO, provided certain conditions are met. Three sets of rules generally apply. GATT Article XXIV applies to goods trade, and allows the formation of free trade areas and customs unions (areas with common external tariffs). These provisions require that RTAs be notified to the other WTO members, cover "substantially all trade," and do not effectively raise barriers on imports from third parties. GATS Article V allows for economic integration agreements related to services trade, provided they entail "substantial sectoral coverage," eliminate "substantially all discrimination," and do not "raise the overall level of barriers to trade in services" on members outside the agreement. Paragraph 2(c) of the "enabling clause," which deals with special and differential treatment, allows for RTAs among developing countries in goods trade, based on the "mutual reduction or elimination of tariffs." RTA provisions in the GATS also allow greater flexibility in sectoral coverage within services agreements that include developing countries.

Joining the WTO: The Accession Process

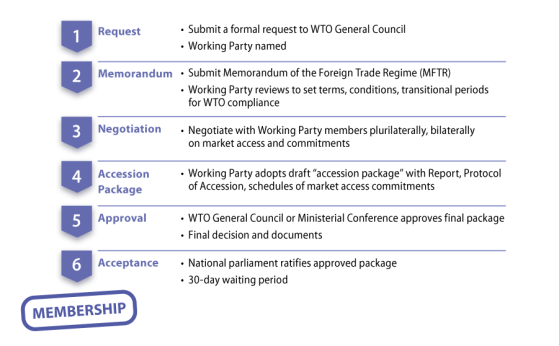

There are currently 164 members of the WTO. Another 22 countries are seeking to become members.67 Joining the WTO means taking on the commitments and obligations of all the multilateral agreements. Governments are motivated to join not just to expand access to foreign markets but also to spur domestic economic reforms, help transition to market economies, and promote the rule of law.68 While any state or customs territory fully in control of its trade policy may become a WTO member, a lengthy process of accession involves a series of documentation of a country's trade regime and market access negotiation requirements (see Figure 7).69

For example, Kazakhstan joined the WTO on November 30, 2015, after a 20-year process. Afghanistan became the 164th WTO member on July 29, 2016, after nearly 12 years of negotiating its accession terms. Other countries have initiated the process but face delays. Iran first applied for membership in 1996 and, while it submitted its Memorandum on the Foreign Trade Regime in 2009 (a prerequisite for negotiating an accession package), Iran has not begun the bilateral negotiation process, and the United States is unlikely to support its accession.70

As the WTO generally operates by member consensus, any single member could block the accession of a prospective new member. As part of the process, a prospective member must satisfy specific market access conditions of other WTO members by negotiating on a bilateral basis. The United States has been a central arbiter of the accession process for countries like China (joined in 2001, see below), Vietnam (2007), and Russia (2012), with which permanent normal trade relations had to be established concurrently under U.S. law for the United States to receive the full benefits of their membership.

|

|

Source: WTO. Created by CRS. Notes: The Working Party is a group of WTO members negotiating multilaterally with a country that is applying to join the WTO. |

China's Accession and Membership

China formally joined the WTO in December 2001.71 China has emerged as a major player in the global economy, as the fastest-growing economy, largest merchandise exporter, and second-largest merchandise importer worldwide. China's accession into the WTO on commercially meaningful terms was a major U.S. trade objective during the late 1990s.72 Entry into the WTO was viewed as an important catalyst for spurring additional economic and trade reforms and the opening of China's economy in a market, rules-based direction.73 These reforms have made China an increasingly significant market for U.S. exporters, a central factor in global supply chains, and a major source of low-cost goods for U.S. consumers. At the same time, China has yet to fully transition to a market economy and the government continues to intervene in many parts of the economy, which has created a growing debate over the role of the WTO in both respects.

Negotiations for China's accession to the GATT and then the WTO began in 1986 and took more than 15 years to complete. During WTO negotiations, China sought to enter the WTO as a developing country, while U.S. trade officials insisted that China's entry into the WTO had to be based on "commercially meaningful terms" that would require China to significantly reduce trade and investment barriers within a relatively short time. In the end, a compromise was reached that required China to make immediate and extensive reductions in various trade and investment barriers, while allowing it to maintain some level of protection (or a transitional period of protection) for certain sensitive sectors (see text box).74

|

Selected Terms of China's 2001 WTO Accession75

|

According to USTR, after joining the WTO, China began to implement economic reforms that facilitated its transition toward a market economy and increased its openness to trade and foreign direct investment (FDI). China also generally implemented its tariff cuts on schedule. However, by 2006, U.S. officials and companies noted evidence of some trends toward a more restrictive trade regime and more state intervention in the economy.76 In particular, observers voiced concern about various Chinese industrial policies, such as those that foster indigenous innovation based on forced technology transfer, domestic subsidies, and IP theft. Some stakeholders have expressed concerns over China's mixed record of implementing certain WTO obligations and asserted that, in some cases, China appeared to be abiding by the letter but not the "spirit" of the WTO.77

The United States and other WTO members have used dispute settlement procedures on a number of occasions to address China's alleged noncompliance with certain WTO commitments. As a respondent, China accounts for about 12% of total WTO disputes since 2001. The United States has brought 23 dispute cases against China at the WTO on issues, including IPR protection, subsidies, and discriminatory industrial policies, and has largely prevailed in most cases. Though some issues remain contested, China has largely complied with most WTO rulings.78 China has also increasingly used dispute settlement to confront what it views as discriminatory measures; to date, it has brought 16 cases against the United States (as of October 2019).

More broadly, the Trump Administration has questioned whether WTO rules are sufficient to address the challenges that China's economy presents. USTR Robert Lighthizer expressed this view in remarks in September 2017: "The sheer scale of their coordinated efforts to develop their economy, to subsidize, to create national champions, to force technology transfer, and to distort markets in China and throughout the world is a threat to the world trading system that is unprecedented. Unfortunately, the World Trade Organization is not equipped to deal with this problem."79 USTR views efforts to resolve concerns over Chinese trade practices to date as limited in effectiveness, including through WTO dispute settlement, as well as recent proposals by WTO members to craft new rules and WTO reforms.80 In its latest annual report to Congress on China's WTO compliance for 2018, USTR stated:

[The WTO dispute settlement] mechanism is not designed to address a trade regime that broadly conflicts with the fundamental underpinnings of the WTO system. No amount of WTO dispute settlement by other WTO members would be sufficient to remedy this systemic problem. Indeed, many of the most harmful policies and practices being pursued by China are not even directly disciplined by WTO rules.81

Another related concern some have is China's claim that it is a "developing country" under the WTO, and, in particular, implications for concessions under ongoing and future WTO negotiations.82 Through developing country status, which countries self-designate, countries are entitled to certain rights under special and differential treatment (SDT), among other provisions in WTO agreements (for more discussion, see "Treatment of Developing Countries" and text box). While it is unclear the extent of SDT provisions China has sought in current ongoing negotiations, China is a part of the coalition group of Asian developing members at the WTO and has claimed to be a developing country in various fora.83 In the view of the Trump Administration, "the United States has never accepted China's claim to developing-country status," and the WTO should change its approach to affording flexibilities based on developing country status.84 (See "Treatment of Developing Countries"). Chinese officials have asserted that despite being the world's second-largest economy, China remains a developing country, due to its relatively low GDP per capita and other economic challenges.85

Concerns over China's trade actions despite its WTO commitments have led the Trump Administration to increase the use of unilateral mechanisms outside the WTO that in its view more effectively address Chinese "unfair trade practices;" the recent Section 301 investigation of Chinese IPR and technology transfer practices and resulting imposition of tariffs is evidence of this strategy.86 Prior to the establishment of the WTO, the United States resorted to Section 301 relatively frequently, in particular due to concerns that the GATT lacked an effective dispute settlement system.87 When the United States joined the WTO in 1995, it agreed to use the dispute settlement mechanism rather than act unilaterally; many analysts contend that the United States has violated its WTO obligations by imposing tariffs against China under Section 301. Following its investigation, the United States also initiated a WTO dispute settlement case against China's "discriminatory technology licensing" in March 2018. Subsequently, China filed its own complaints at the WTO over U.S. tariff actions (see above).