What Is the Farm Bill?

The farm bill is an omnibus, multiyear law that governs an array of agricultural and food programs. Although agricultural policies are sometimes created and changed by freestanding legislation or as part of other major laws, the farm bill provides a predictable opportunity for policymakers to comprehensively and periodically address agricultural and food issues. The farm bill is typically renewed about every five or six years.1

Historically, farm bills focused on farm commodity program support for a handful of staple commodities—corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, rice, peanuts, dairy, and sugar. Farm bills have become increasingly expansive in nature since 1973, when a nutrition title was first included. Other prominent additions since then include conservation, horticulture, and bioenergy.2

The omnibus nature of the farm bill can create broad coalitions of support among sometimes conflicting interests for policies that, individually, might have greater difficulty negotiating the legislative process. This can lead to competition for funds provided in a farm bill. In recent years, more stakeholders have become involved in the debate on farm bills, including national farm groups; commodity associations; state organizations; nutrition and public health officials; and advocacy groups representing conservation, recreation, rural development, faith-based interests, local food systems, and certified organic production.

The Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-334, H.Rept. 115-1072), referred to here as the "2018 farm bill," is the most recent omnibus farm bill. It was enacted in December 2018, with most provisions expiring in 2023. It succeeded the Agricultural Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-79; 2014 farm bill). The 2018 farm bill contains 12 titles encompassing commodity revenue supports, farm credit, trade, agricultural conservation, research, rural development, energy, and foreign and domestic food programs, among other programs.3 (All titles in the 2018 farm bill are described in the text box below as well as in the section "Title-by-Title Summaries of the 2018 Farm Bill.") Provisions in the 2018 farm bill modified the structure of farm commodity support, expanded crop insurance coverage, amended conservation programs, reauthorized and revised nutrition assistance, and extended authority to appropriate funds for many U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) discretionary programs through FY2023.

Without reauthorization, some farm bill programs would expire, such as the nutrition assistance programs and the farm commodity revenue programs. Procedurally, the potential for expiration and the consequences of expired law may motivate legislative action.4 Functionally, without reauthorization, support for certain basic farm commodities would revert to long-abandoned—and potentially costly—supply-control and price regimes under permanent law dating back to the 1940s. Some programs would cease to operate unless reauthorized, while others might continue to pay only existing obligations. Nutrition assistance programs that require reauthorization and are funded with mandatory spending can continue to operate via appropriations acts. Many discretionary programs would lose their statutory authority to receive appropriations, though an annual appropriations act could provide funding under an implicit authorization. Other programs amended in the farm bill have permanent authority (e.g., crop insurance).5

|

|

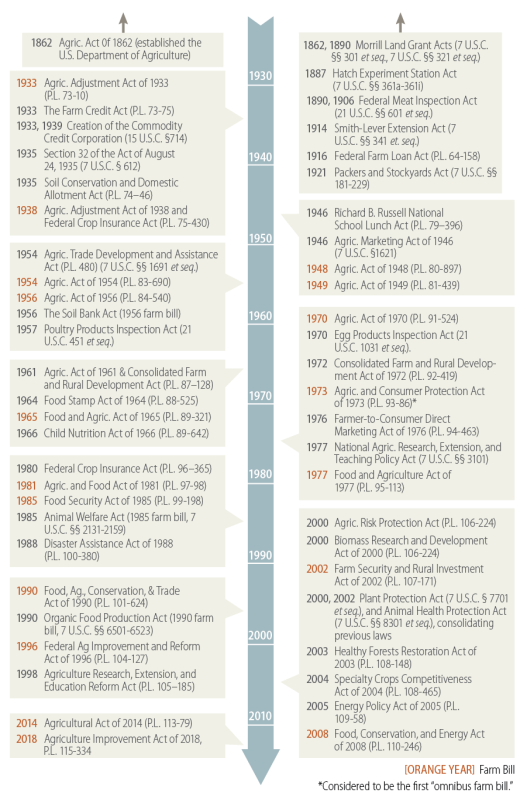

Figure 1 provides a timeline of selected important dates for U.S. farm bill policy and other related laws. In many respects, agricultural policy in the United States began with the creation of USDA, homesteading, and subsequent creation of the land-grant universities in the 1800s. Many stand-alone agricultural laws were passed during the early 1900s to help farmers with credit availability and marketing practices and to protect consumers via meat inspection.

|

Figure 1. Selected Dates for U.S. Farm Bill Policy and Selected Related Laws |

|

|

Source: CRS. |

The economic depression and dust bowl in the 1930s prompted the first "farm bill" in 1933, with subsidies and production controls to raise farm incomes and encourage conservation. Commodity subsidies evolved through the 1960s, when Great Society reforms drew attention to food assistance. The 1973 farm bill was the first "omnibus" farm bill. It included not only farm supports but also food stamp reauthorization to provide nutrition assistance for needy individuals. Subsequent farm bills expanded in scope, adding titles for formerly stand-alone laws such as trade, credit, and crop insurance. New conservation laws were added in the 1985 farm bill, organic agriculture in the 1990 farm bill, research programs in the 1996 farm bill, bioenergy in the 2002 farm bill, and horticulture and local food systems in the 2008 farm bill.

What Is the Estimated Cost of the Farm Bill?

The farm bill authorizes programs in two spending categories: mandatory and discretionary.

- Mandatory spending programs generally operate as entitlements. Mandatory spending is authorized and paid for when a law is enacted under budget enforcement rules that use multiyear federal budget estimates.6

- Discretionary spending programs are authorized for their scope but are not funded in the farm bill. They are subject to annual appropriations and may not receive any funding or may receive less than the farm bill-authorized amount.

How Much Was It Expected to Cost at Enactment in 2018?

At enactment in December 2018, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the total cost of the mandatory programs in the farm bill would be $428 billion over its five-year duration, FY2019-FY2023, about $1.8 billion more than if the 2014 farm bill were extended. On a 10-year basis, the expected cost was $867 billion through FY2028, which was budget neutral (Table 1).7

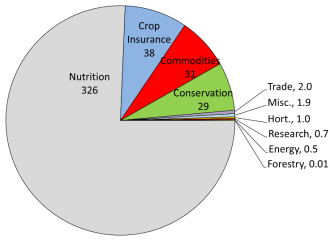

Four titles account for 99% of anticipated farm bill mandatory outlays: Nutrition, Crop Insurance, Farm Commodities, and Conservation. The Nutrition title comprises 76% of mandatory outlays, mostly for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps). The remaining 24% covers mostly federal crop insurance and commodity support (16%) and conservation (7%; Figure 2). Programs in other titles account for about 1% of mandatory outlays. However, many programs are authorized to receive discretionary (appropriated) funds.

How Have Projections Changed Since Enactment?

Since enactment of the 2018 farm bill, CBO has updated its projections of government spending given new information about the economy and program participation.8 Based on the May 2019 CBO baseline, the projected cost of the four largest titles of the farm bill is $418 billion (FY2019-FY2023; Table 2). This is $7 billion less than the $425 billion subtotal for those four titles at enactment (-1.7%). This change is due solely to changing economic conditions. Projected outlays under SNAP were reduced by about 1%. A rise in projected crop insurance outlays partially offsets a reduction in the farm commodity and disaster programs. Within Title I, dairy and disaster programs have higher projected outlays, and crop revenue programs have decreased.

Table 1. Budget for the 2018 Farm Bill

(millions of dollars, five- and 10-year totals, mandatory spending)

|

Five years (FY2019-FY2023) |

10 years (FY2019-FY2028) |

|||||

|

Farm bill titles |

CBO baseline April 2018 |

Score of 2018 farm bill |

Projected outlays at enactment |

CBO baseline April 2018 |

Score of 2018 farm bill |

Projected outlays at enactment |

|

Commodities |

31,340 |

+101 |

31,440 |

61,151 |

+263 |

61,414 |

|

Conservation |

28,715 |

+555 |

29,270 |

59,754 |

-6 |

59,748 |

|

Trade |

1,809 |

+235 |

2,044 |

3,624 |

+470 |

4,094 |

|

Nutrition |

325,922 |

+98 |

326,020 |

663,828 |

+0 |

663,828 |

|

Credit |

-2,205 |

+0 |

-2,205 |

-4,558 |

+0 |

-4,558 |

|

Rural Development |

98 |

-530 |

-432 |

168 |

-2,530 |

-2,362 |

|

Research |

329 |

+365 |

694 |

604 |

+615 |

1,219 |

|

Forestry |

5 |

+0 |

5 |

10 |

+0 |

10 |

|

Energy |

362 |

+109 |

471 |

612 |

+125 |

737 |

|

Horticulture |

772 |

+250 |

1,022 |

1,547 |

+500 |

2,047 |

|

Crop Insurance |

38,057 |

-47 |

38,010 |

78,037 |

-104 |

77,933 |

|

Miscellaneous |

1,259 |

+685 |

1,944 |

2,423 |

+738 |

3,161 |

|

Subtotal |

426,462 |

+1,820 |

428,282 |

867,200 |

+70 |

867,270 |

|

- Increase revenue |

- |

+35 |

35 |

- |

+70 |

70 |

|

Total |

426,462 |

+1,785 |

428,247 |

867,200 |

+0 |

867,200 |

Sources: CRS. Compiled from the CBO Baseline by Title (unpublished; April 2018); and CBO cost estimate of the conference agreement for H.R. 2, December 11, 2018.

Notes: Baseline for the Credit title is negative because of receipts to the Farm Credit System Insurance Fund. Baseline for the Rural Development "cushion of credit" is accounted for outside of the farm bill.

|

Figure 2. Projected Outlays of the 2018 Farm Bill at Enactment (Mandatory outlays, billions of dollars, FY2019-FY2023) |

|

|

Sources: CRS. Compiled from the CBO Baseline by Title (unpublished, April 2018); and CBO cost estimate of the conference agreement for H.R. 2, December 11, 2018. |

Table 2. Projected Outlays of the 2018 Farm Bill Since Enactment

(millions of dollars, five-year totals, mandatory spending)

|

Selected farm bill titles |

At enactment, December 2018 |

Most recently, May 2019 |

||

|

Projection for FY2019-FY2023 |

Share |

Projection for FY2019-FY2023 |

Change since enactment |

|

|

Nutrition |

326,020 |

76.1% |

321,405 |

-4,615 |

|

Crop Insurance |

38,010 |

8.9% |

40,882 |

+2,872 |

|

Commodities and Disaster |

31,440 |

7.3% |

26,763 |

-4,677 |

|

Conservation |

29,270 |

6.8% |

28,477 |

-793 |

|

Subtotal, four largest titles |

424,740 |

99.2% |

417,527 |

-7,213 |

|

Total, 12 titles (see Table 1) |

428,282 |

100.0% |

na |

na |

Source: CRS, using CBO data. See Table 1, and based on CBO data in "Details About Baseline Projections for Selected Programs," May 2019.

Notes: "na" indicates that sufficient detail is not available to compile data for all titles in non-farm-bill years.

How Have the Allocations Changed over Time?

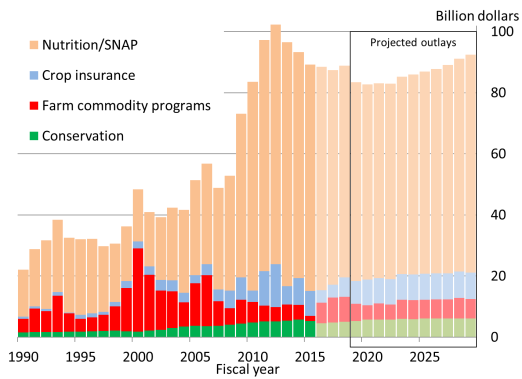

Figure 3 shows trends in nominal farm bill mandatory spending for 1990-2018 and projections through 2029. SNAP outlays, which comprise most of the Nutrition title, increased markedly through the recession that ended in 2009 and have been gradually decreasing since 2012. The distribution among farm safety net programs reflects the growing importance of crop insurance relative to the traditional farm commodity programs. This is a combination of both policy changes and an often-offsetting budget effect when market prices change. (Higher market prices imply less counter-cyclical support but higher insurance costs.) Conservation program outlays increased steadily since the 1990s but have leveled off in recent years.

The distribution of spending across titles in the farm bill over time is not a zero-sum game. Legislative changes enacted in each farm bill account for only a fraction of the observed change between farm bills. Every year, CBO re-estimates the baseline to determine expected costs. Baseline projections can rise and fall over time based on changes in economic conditions, and an increase in one title does not imply a reduction in another title. Moreover, budget issues for the whole federal government and for each farm bill may affect policy decisions for how farm bill spending is allocated. All of these factors are reflected in the trends seen in Figure 3.

For example, an often-discussed issue is the size of the Nutrition title. When the 2008 farm bill was enacted, the Nutrition title was 67% of the five-year total budget. When the 2014 farm bill was enacted, the nutrition share had risen to 80% of the farm bill total, largely because the Nutrition title baseline had increased as a result of an economic recession. By the 2018 farm bill, the amount and share in the Nutrition title had moderated to about 76% (Table 3). These changes in the size and proportion, however, do not mean that the title grew at the expense of agricultural programs. The total for the entire farm bill rose and fell with the Nutrition title's baseline. The overall amounts for agriculture programs (non-nutrition) also rose, even though their share of the total declined relative to the comparatively larger changes in the Nutrition title. Since the 2008 farm bill, Conservation title projections have grown slightly, while Energy title programs have generally remained flat until a recent decline in the 2018 farm bill. Conversely, the Horticulture title shows steady growth in its amount and share, especially relative to other titles—even though its base amount is relatively small.

Table 3. Distribution of Farm Bill Titles in 2008, 2014, and 2018

(billions of nominal dollars, five-year projection at enactment, mandatory spending)

|

2008 farm bill |

2014 farm bill |

2018 farm bill |

||||||||||||||||

|

Farm bill titles |

Amount |

Share |

Amount |

Share |

Amount |

Share |

||||||||||||

|

Overall |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Nutrition (Title IV) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Rest of the farm bill |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Total, entire farm bill |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Selected agricultural titles |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Farm commodities (Title I) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Crop insurance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Subtotal, farm safety net |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Conservation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Research |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Energy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Horticulture |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

Title-by-Title Summaries of the 2018 Farm Bill

Following are summaries of the major provisions of each title of the 2018 farm bill. For more detailed information, see CRS Report R45525, The 2018 Farm Bill (P.L. 115-334): Summary and Side-by-Side Comparison.

Title I: Commodities9

The Commodities title authorizes support programs for dairy, sugar, and covered commodities—including major grain, oilseed, and pulse crops—as well as agricultural disaster assistance. The 2018 farm bill extends authority for most current commodity programs but with some modifications. Major field-crop programs include Price Loss Coverage (PLC), Agricultural Risk Coverage (ARC), and Marketing Assistance Loans (MAL). The new dairy program protects a portion of the margin between milk and feed prices. The sugar program provides a combination of price supports, limits on imports, and processor/refiner marketing allotments. Four disaster assistance programs focus primarily on livestock and tree crops. Title I also includes several administrative provisions that set payment limits, an adjusted gross income (AGI) threshold, and other details for payment attribution and eligibility.

The 2018 farm bill provides producers the flexibility of switching between ARC and PLC coverage under certain conditions. Producers can update their program yields for the PLC, and an escalator provision was added that could potentially raise a covered commodity's effective reference price. For ARC, data from the Risk Management Agency become the primary source for county average yields, which is intended to avoid cross-county disparities in payments. For the marketing assistance loan program, rates are increased for several crops, including barley, corn, grain sorghum, oats, extra-long-staple cotton, rice, soybeans, dry peas, lentils, and small and large chickpeas. Regarding payment limitations, the definition of family farm is expanded to include first cousins, nieces, and nephews, thus increasing eligibility.

For dairy, a new Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) program adds higher levels of margin coverage, provides for lower producer-paid premium rates for 5 million pounds or less of milk production, and allows producers to cover a larger percentage of milk production compared with the 2014 Margin Protection Program. Under DMC, premiums were designed to incentivize higher levels of coverage. Producers may participate in both margin coverage and the Livestock Gross Margin-Dairy insurance program that insures the margin between feed costs and a designated milk price.

For assistance following a disaster, the 2018 farm bill amends payments for livestock and tree losses and removes select payment limitations. It also expands eligibility for the Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program (NAP) and amends payment calculations and service fees.

Title II: Conservation10

The Conservation title provides assistance to agricultural producers by addressing environmental resource concerns on private land through land retirement, conservation easements, working lands assistance, and partnership opportunities. The 2018 farm bill reauthorizes and amends many of the largest conservation programs and creates a number of new pilot programs, carve-outs, and initiatives.

The two largest working lands programs—Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP)—were reauthorized and amended. Enrollment for CSP is reduced and funds are shifted, in part, to EQIP and other farm bill conservation programs. EQIP is expanded to irrigation and drainage entities, and additional funding carve-outs and pilot projects are authorized. The largest land retirement program—the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP)—is reauthorized and expanded by incrementally increasing the enrollment limit from 24 million acres in FY2019 to 27 million acres by FY2023. CRP payments to participants are reduced, and additional subprograms are authorized. The Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) is redefined as a stand-alone program with separate contracts and an expanded scope of eligible projects. Agricultural land easements in the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP) are amended to provide additional flexibility to eligible entities.

Title III: Trade11

The Trade title addresses U.S. agricultural export programs and U.S. international food assistance programs. Major programs support agricultural trade promotion and facilitation, such as the Market Access Program, and the primary U.S. international food assistance program, Food for Peace (FFP) Title II.

The 2018 farm bill reauthorizes existing U.S. export promotion programs and consolidates four programs into a new Agricultural Trade Promotion and Facilitation Program (ATPFT) that establishes permanent mandatory funding. It also establishes a Priority Trade Fund within ATPFT. The enacted law also reauthorizes direct credits or export credit guarantees for the promotion of agricultural exports to emerging markets.

The 2018 farm bill reauthorizes all international food assistance programs as well as certain operational details such as prepositioning of agricultural commodities and micronutrient fortification. It also adds a provision requiring that food vouchers, cash transfers, and local and regional procurement of non-U.S. foods avoid market disruption in the recipient country. The 2018 farm bill amends FFP Title II by eliminating the requirement to monetize—that is, sell on local markets to fund development projects—at least 15% of FFP Title II commodities. It also increases the minimum level of FFP Title II funds allocated for nonemergency assistance. The 2018 farm bill also reauthorizes and/or amends other international food assistance programs, including the McGovern-Dole program.

Title IV: Nutrition12

The Nutrition title provides food assistance for low-income households through programs including SNAP and The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP). The 2018 farm bill amends various aspects of the programs and reauthorizes them through FY2023. Rules regarding SNAP eligibility and benefit calculation are largely maintained, including general work requirements and the time limit for nondisabled adults without dependents. The law requires some changes to the calculation for homeless households' benefits as well as certain aspects of benefit calculation. Among other program integrity policies, the 2018 farm bill establishes a National Accuracy Clearinghouse to identify concurrent enrollment in multiple states.

For the SNAP Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) system, the 2018 farm bill places limits on fees, shortens the time frame for unused benefits, and changes the authorization requirements for some farmers' market operators. It requires nationwide online acceptance of SNAP benefits and authorizes a pilot project about recipients' use of mobile technology to redeem SNAP benefits.

The 2018 farm bill further reauthorizes, renames, and expands the Food Insecurity Nutrition Incentive (FINI, now the Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program), a grant program for projects that incentivize SNAP and other low-income participants' purchase of fruits and vegetables. The 2018 farm bill also continues funding for the Senior Farmers' Market Nutrition Program and reauthorizes but reduces funding for the Community Food Projects grants.

It also reauthorizes and revises food distribution programs. Supporting emergency feeding organizations, the bill reauthorizes TEFAP and authorizes new projects to facilitate the donation of raw/unprocessed commodities. The Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations now requires the federal government to pay at least 80% of administrative costs and includes a demonstration project for tribes to purchase their own commodities.

Title V: Credit

The Credit title offers direct government loans to farmers/ranchers and guarantees on private lenders' loans. For the USDA farm loan programs, the enacted law adds criteria that may be used to reduce a three-year farming experience requirement. It raises the maximum loan size for guaranteed loans by about 25%. It further doubles the limit for direct farm ownership loans and increases the direct operating loan limit by one-third. Beginning and socially disadvantaged farmers may benefit from a higher guarantee percentage on loans. For the Federal Agricultural Mortgage Corporation (known as FarmerMac), the 2018 farm bill increases an acreage exception to remain a qualified loan. For the Farm Credit System Insurance Corporation, the farm bill provides greater statutory guidance about its conservatorship and receivership authorities, which are largely modeled after the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. It also reauthorizes the State Agricultural Loan Mediation Program and expands the range of eligible issues.

Title VI: Rural Development13

The Rural Development title supports rural business and community development. The 2018 farm bill makes changes to existing USDA programs. It temporarily prioritizes public health emergencies and substance use disorder, including in the Distance Learning and Telemedicine Program, the Community Facilities Program, and the Rural Health and Safety Education Program. For rural broadband deployment, the 2018 farm bill authorizes the Rural Broadband Access Program to provide grants in addition to direct and guaranteed loans and increases the minimum acceptable speed levels for broadband service. The farm bill reauthorizes the Rural Energy Savings Program and amends the program to allow off-grid and energy storage systems. It amends the definition of rural to exclude individuals incarcerated on a "long-term or regional basis" and excludes the first 1,500 individuals who reside in housing located on military bases. The 2018 farm bill further provides that areas defined as rural between 1990 and 2020 may remain so until the 2030 census. It amends the Cushion of Credit Payments Program for rural utilities to cease new deposits and to modify the interest rate.

Title VII: Research, Extension, and Related Matters14

The Research title supports agricultural research at the federal level and provides support for cooperative research, extension, and postsecondary agricultural education programs. The 2018 farm bill reauthorizes several existing programs and establishes new programs and initiatives.

The 2018 farm bill also amends and reauthorizes funding for the competitively awarded Agriculture and Food Research Initiative (AFRI), Organic Agriculture Research and Extension Initiative (OREI), and Specialty Crop Research Initiative (SCRI). It reauthorizes the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP), which distributes funds to eligible applicants on a formula basis. It enhances mandatory funding and requires a strategic plan for the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research (FFAR).

Among new programs and initiatives, the 2018 farm bill establishes the Agriculture Advanced Research and Development Authority Pilot, research Centers of Excellence at 1890 Institutions (historically black land-grant colleges and universities), and competitive grants programs to benefit tribal students and those at 1890 Institutions. It also establishes new competitive research and extension grants for hemp research and indoor and urban agriculture.

Title VIII: Forestry15

The Forestry title supports forestry management programs run by USDA's Forest Service. The 2018 farm bill continues provisions related to forestry research and provides financial and technical assistance to nonfederal forest landowners. It also includes several provisions addressing management of the National Forest System lands managed by the Forest Service and the public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management in the Department of the Interior.16 It reauthorizes the Healthy Forests Reserve Program, Rural Revitalization Technology, National Forest Foundation, and funding for implementing statewide forest resource assessments. It authorizes financial assistance for large restoration projects that cross landownership boundaries. The enacted law also addresses issues related to the accumulation of biomass and the associated risk for uncharacteristic wildfires.

The 2018 farm bill changes how the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management comply with the National Environmental Policy Act for management of sage grouse and mule deer habitat. It also changes the Forest Service's authority to designate insect and disease treatment areas and procedures intended to expedite the environmental analysis. It establishes two watershed protection programs on National Forest System lands and authorizes acceptance of cash or in-kind donations for those programs.

Title X: Energy17

The Energy title encourages the development of biofuels and farm and community renewable energy systems through grants, loan guarantees, and a feedstock procurement initiative. It also supports increases in energy efficiency as well as the development of biobased products. The 2018 farm bill extends eight programs and one initiative through FY2023, repeals one program and one initiative (the Repowering Assistance Program and the Rural Energy Self-Sufficiency Initiative), and establishes one new grant program (the Carbon Utilization and Biogas Education Program). It amends the Biomass Crop Assistance Program to include algae. It also modifies the definitions of biobased product (to include renewable chemicals), biorefinery (to include the conversion of an intermediate ingredient or feedstock), and renewable energy systems (to include ancillary infrastructure such as a storage system). Compared to previous farm bills, the 2018 farm bill provides less mandatory funding for existing USDA energy programs.

Title X: Horticulture18

The Horticulture title supports specialty crops—as defined in statute, covering fruits, vegetables, tree nuts, and nursery products—through a range of initiatives, including market promotion, plant pest and disease prevention, and public research. The title also provides support to certified organic agricultural production and locally produced foods.

The 2018 farm bill reauthorizes many of these provisions, including block grants to states, support for farmers markets, data and information collection, education on food safety and biotechnology, and organic certification. Provisions affecting the specialty crop, certified organic, and local foods sectors are not limited to the Horticulture title (Title X) but are contained within several other titles, including the Research, Nutrition, and Trade titles.

The 2018 farm bill expands and adds funding for farmers markets and local food promotion programs by combining existing programs to create a new Local Agriculture Market Program. Other provisions supporting local and urban agriculture development are housed in the Miscellaneous, Research, Conservation, and Crop Insurance titles.19 The 2018 farm bill makes changes to USDA's National Organic Program (NOP) and related programs, addressing concerns about organic import integrity by including provisions that strengthen the tracking, data collection, and investigation of organic product imports. It also expands mandatory funding for the National Organic Certification Cost Share Program and expands support for technology upgrades to improve tracking and verification of organic imports.

The 2018 farm bill authorizes establishing a regulatory framework for the cultivation of hemp (as defined in statute) and creates a new regulatory program for hemp production under USDA's oversight. Related provisions expand the statutory definition of hemp and expand eligibility to produce hemp to a broader set of producers and groups, including tribes and territories. Provisions in other titles further expand support for hemp, including making hemp eligible for federal crop insurance and certain USDA research programs, as well as excluding hemp from the statutory definition of marijuana under the Controlled Substances Act.20

Title XI: Crop Insurance

The Crop Insurance title modifies the permanently authorized Federal Crop Insurance Act. The federal crop insurance program offers subsidized policies to farmers to protect against losses in yield, crop revenue, or whole farm revenue.

The 2018 farm bill makes several modifications. It expands coverage by authorizing catastrophic policies for forage and grazing crops and grasses. It also allows producers to purchase separate crop insurance policies for crops that can be both grazed and mechanically harvested on the same acres and to receive independent indemnities for each intended use. For crop insurance research and development, the farm bill redefines beginning farmer or rancher as an individual having actively operated and managed a farm or ranch for less than 10 years. This redefinition makes these individuals eligible for federal subsidy benefits of whole-farm insurance plans.

The law also allows waivers of certain viability and marketability requirements for developing a policy or pilot program for the production of hemp. It further adds hemp (as defined in statute) as an eligible crop for federal crop insurance and to the limited list of crops that cover post-harvest losses.

Title XII: Miscellaneous

The Miscellaneous title covers a wide array of issues across six subtitles, including livestock, agriculture and food defense, historically underserved producers, Department of Agriculture Reorganization Act of 1994 Amendments, and other general provisions.

The livestock provisions establish the National Animal Disease Preparedness Response Program and the National Animal Vaccine and Veterinary Countermeasures Bank. Other livestock provisions authorize appropriations for the Sheep Production and Marketing Grant Program; add llamas, alpacas, live fish, and crawfish to the list of covered animals under the Emergency Livestock Feed Assistance Act; and establish regional cattle and carcass grading centers. Other animal-related provisions ban the slaughter of dogs and cats, impose a ban on animal fighting in U.S. territories, and require a report on the importation of dogs.

The Miscellaneous title includes a number of other provisions covering a wide range of policy issues. Among these, it directs USDA to restore certain exemptions for inspection and weighing services that were included in the United States Grain Standards Act but were rescinded by USDA when the act was reauthorized in 2015. It amends the Controlled Substances Act to exclude hemp (as defined in statute) from the statutory definition of marijuana. The enacted law also establishes the Farming Opportunities Training and Outreach program by combining and expanding existing programs for beginning, limited resource, and socially disadvantaged farmers and ranchers.21 It further extends outreach and technical assistance programs for socially disadvantaged farmers and ranchers and adds military veteran farmers and ranchers as a qualifying group. It also creates a military veterans agricultural liaison within USDA to advocate for and provide information to veterans and establishes an Office of Tribal Relations to coordinate USDA activities with Native American tribes.22 The enacted law requires USDA to conduct additional planning and monitoring of plant disease and pest concerns and reauthorizes policies supporting citrus growers and cotton and wool apparel manufacturers.