Introduction and Overview

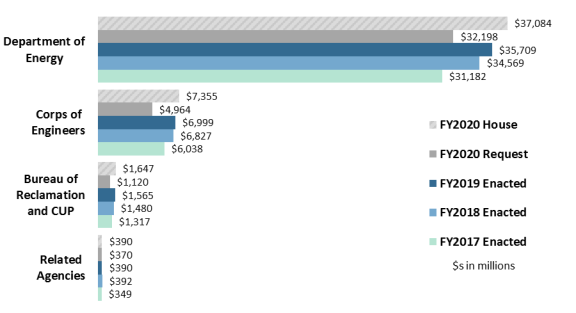

The Energy and Water Development and Related Agencies appropriations bill includes funding for civil works projects of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), the Department of the Interior's Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) and Central Utah Project (CUP), the Department of Energy (DOE), and a number of independent agencies, including the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) and the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC). Figure 1 compares the major components of the Energy and Water Development bill from FY2017 through the FY2020 House-passed measure.

|

Figure 1. Major Components of Energy and Water Development Appropriations Bill |

|

|

Sources: H.R. 2740, CBO Current Status Report, H.Rept. 116-83, FY2020 agency budget justifications, and explanatory statement for Energy and Water Development and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2019 (Division A of H.R. 5895). Includes some adjustments; see tables 4-7 for details. Notes: "FY2019 Request" includes Administration budget amendments and other adjustments applied after initial submittal. CUP=Central Utah Projec t Completion Account. |

President Trump submitted his FY2020 detailed budget proposal to Congress on March 18, 2019 (after submitting a general budget overview on March 11). The budget requests for agencies included in the Energy and Water Development appropriations bill total $37.956 billion—$6.705 billion (15%) below the FY2019 appropriation.1 (See Table 3.) A $1.309 billion increase (12%) is proposed for DOE nuclear weapons activities.

The FY2020 budget request proposed substantial reductions from the FY2019 enacted level for DOE energy research and development (R&D) programs, including a reduction of $178 million (-24%) in fossil fuels and $502 million (-38%) in nuclear energy. Energy efficiency and renewable energy (EERE) R&D would decline by $1.724 billion (-83%). DOE science programs would be reduced by $1.039 billion (-16%). Programs targeted by the budget for elimination or phaseout include energy efficiency grants, the Advanced Research Projects Agency—Energy (ARPA-E), and loan guarantee programs. Funding would be reduced for USACE by $2.035 billion (-29%), and Reclamation and CUP by $445 million (-28%).

The House passed the FY2020 Energy and Water Development bill on June 19, 2019, by a vote of 226-203. The Energy and Water bill is Division E of an "Appropriations Minibus" (H.R. 2740), which also includes appropriations for Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education; Defense; and State and Foreign Operations. The House-passed bill would provide total appropriations of $46.41 billion, which is $1.75 billion (4%) above the FY2019 enacted appropriation and $8.454 billion (22%) above the Administration request.2 The House Appropriations Committee approved the FY2020 Energy and Water Development appropriations bill on May 21, 2019, by a vote of 31-21 (H.R. 2960, H.Rept. 116-83).

The House-passed bill would increase R&D by 11% for EERE, and decrease fossil and nuclear energy R&D by less than 1% from the FY2019 enacted amounts. Rather than eliminate ARPA-E, as proposed by the Administration, the House bill would increase its funding to $428 million, 17% above the FY2019 enacted appropriation. DOE loan guarantee programs would be continued by the House-passed bill. USACE would receive $7.355 billion, a 5% increase over the FY2019 enacted level, and Reclamation and CUP would receive $1.647 billion, also 5% more than in FY2019. DOE weapons activities would receive a smaller increase than requested, to $11.761 billion, 6% above the FY2019 enacted appropriation, under the House bill.

For FY2019, the conference agreement on H.R. 5895 (H.Rept. 115-929) provided total Energy and Water Development appropriations of $44.66 billion—3% above the FY2018 level and 23% above the FY2019 request.3 The bill was signed by the President on September 21, 2018 (P.L. 115-244). Figures for FY2019 exclude emergency supplemental appropriations totaling $17.419 billion provided to USACE and DOE for natural disaster response by the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123), signed February 9, 2018. Similarly, the discussion and amounts in this report do not reflect the emergency supplemental appropriations provided in the Additional Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-20) for USACE ($3.258 billion) and Reclamation ($16 million). For more details, see CRS Report R45258, Energy and Water Development: FY2019 Appropriations, by Mark Holt and Corrie E. Clark, and CRS Report R45326, Army Corps of Engineers Annual and Supplemental Appropriations: Issues for Congress, by Nicole T. Carter.

Budgetary Limits

Congressional consideration of the annual Energy and Water Development appropriations bill is affected by certain procedural and statutory budget enforcement measures. These consist primarily of limits associated with the budget resolution on discretionary spending (spending provided in annual appropriations acts) and allocations of this amount that apply to spending under the jurisdiction of each appropriations subcommittee.

Statutory budget enforcement is currently derived from the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA; P.L. 112-25). The BCA established separate limits on defense and nondefense discretionary spending. These limits are in effect from FY2012 through FY2021 and are primarily enforced by an automatic spending reduction process called sequestration, in which a breach of a spending limit would trigger across-the-board cuts within that spending category.

The BCA's statutory discretionary spending limits were increased for FY2020 and FY2021 by the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (BBA 2019, P.L. 116-37, H.R. 3877), signed by the President August 2, 2019. For FY2020, BBA 2019 sets discretionary spending limits of $666.5 billion for defense funding and $621.5 billion for nondefense funding. Without BBA 2019, the FY2020 limits under BCA would have been $576 billion for defense and $543 billion for nondefense, substantially lower than the total appropriations in each category enacted for FY2019. With the enactment of BBA 2019, the discretionary spending limits for FY2020 will instead increase from their enacted FY2019 levels—by $19.5 billion for defense and $24.5 billion for nondefense.4

The House passed the FY2020 Energy and Water Development Appropriations bill before enactment of the FY2020 spending limits in BBA 2019. The total funding level in the House-passed Energy and Water bill was derived from the total federal spending levels in a resolution passed on April 9, 2019, that required the chairman of the House Budget Committee to submit discretionary appropriations allocations for FY2020 (H.Res. 293). Those allocations were published in the Congressional Record on May 3, 2019, and totaled $1.295 trillion, excluding adjustments. That FY2020 total spending amount was suballocated by the House Appropriations Committee to its subcommittees in a report first issued May 14, 2019 (H.Rept. 116-59, and later H.Rept. 116-103). The Energy and Water Development Subcommittee received a suballocation of $46.413 billion, approximately matching the total in H.R. 2960 as passed by the House.

The total spending level in H.Res. 293 is superseded by BBA 2019, whose total FY2020 discretionary appropriations limit of $1.288 trillion is $7 billion lower than the total in H.Res. 293. The BBA 2019 limits may therefore require changes in the Energy and Water bill's total funding.

(For more information, see CRS Insight IN11148, The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019: Changes to the BCA and Debt Limit, by Grant A. Driessen and Megan S. Lynch, and CRS Report R44874, The Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions, by Grant A. Driessen and Megan S. Lynch.)

Funding Issues and Initiatives

Several issues have drawn particular attention during congressional consideration of Energy and Water Development appropriations for FY2020. The issues described in this section—listed approximately in the order the affected agencies appear in the Energy and Water Development bill—were selected based on the total funding involved, the percentage of proposed increases or decreases, the amount of congressional debate engendered, and potential impact on broader public policy considerations.

USACE and Reclamation Budgets

For USACE, the Trump Administration requested $4.964 billion for FY2020, which is $2.035 billion (-29%) below the FY2019 appropriation. The request includes no funding for initiating new studies and construction projects (referred to as new starts). The FY2020 request seeks to limit funding for ongoing navigation and flood risk-reduction construction projects to those whose benefits are at least 2.5 times their costs, or projects that address safety concerns. Many congressionally authorized USACE projects would not meet that standard. The Administration also proposes to transfer the Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program from USACE to DOE. The House voted to increase USACE funding to $7.355 billion, which is $357 million (5%) above the FY2019 enacted appropriation. The House did not approve the proposed FUSRAP transfer.

Among the various topics contributing to congressional debate on FY2020 appropriations for USACE are the potential use of civil works funds for barrier infrastructure along the U.S. southern border, and efforts to shape the activities of USACE's regulatory program (e.g., its administration of Section 404 of the Clean Water Act). For Reclamation, the FY2020 request would reduce funding by $440 million (28%) from the FY2019 level, to $1.11 billion. The House-passed bill would increase funding by $77 million (5%), to $1.627 billion. For more details, see CRS In Focus IF11137, Army Corps of Engineers: FY2020 Appropriations, by Nicole T. Carter and Anna E. Normand; CRS In Focus IF11158, Bureau of Reclamation: FY2020 Appropriations, by Charles V. Stern; and CRS Report R45326, Army Corps of Engineers Annual and Supplemental Appropriations: Issues for Congress, by Nicole T. Carter.

Power Marketing Administration Reforms: Divestiture, Rate Reform, and Repeal of Borrowing Authority

DOE's FY2020 budget request includes three mandatory proposals related to the Power Marketing Administrations (PMAs)—Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), Southeastern Power Administration (SEPA), Southwestern Power Administration (SWPA), and Western Area Power Administration (WAPA). PMAs sell the power generated by the dams operated by Reclamation and USACE. The Administration proposes to divest the assets of the three PMAs that own transmission infrastructure: BPA, SWPA, and WAPA.5 These assets consist of thousands of miles of high voltage transmission lines and hundreds of power substations. The budget request projects that mandatory savings from the sale of these assets would total approximately $5.8 billion over a 10-year period. The FY2020 budget request includes a proposal to repeal the borrowing authority for WAPA's Transmission Infrastructure Program, which facilitates the delivery of renewable energy resources.

The FY2020 budget also proposes eliminating the statutory requirement that PMAs limit rates to amounts necessary to recover only construction, operations, and maintenance costs; the budget proposes that the PMAs instead transition to a market-based approach to setting rates. The Administration has estimated that this proposal would yield $1.9 billion in new revenues over 10 years. The budget also calls for repealing $3.25 billion in borrowing authority provided to WAPA for transmission projects enacted under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5). The proposal is estimated to save $640 million over 10 years.

All of these proposals would need to be enacted in authorizing legislation, and no congressional action has been taken on them to date. The proposals have been opposed by groups such as the American Public Power Association and the National Rural Electrical Cooperative Association, and they have been the subject of opposition letters to the Administration from several regionally based bipartisan groups of Members of Congress. PMA reforms have been supported by some policy research institutes, such as the Heritage Foundation. For further information, see CRS Report R45548, The Power Marketing Administrations: Background and Current Issues, by Richard J. Campbell.

Termination of Energy Efficiency Grants

The FY2020 budget request proposes to terminate both the DOE Weatherization Assistance Program and the State Energy Program (SEP). The Weatherization Assistance Program provides formula grants to states to fund energy efficiency improvements for low-income housing units to reduce their energy costs and save energy. The SEP provides grants and technical assistance to states for planning and implementation of their energy programs. Both the weatherization and SEP programs are under DOE's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE). The weatherization program received $257 million and SEP $55 million for FY2019, after also having been proposed for elimination in that year's budget request, as well as in FY2018. According to DOE, the proposed elimination of the grant programs is "due to a departmental shift in focus away from deployment activities and towards early-stage R&D."6 The House voted to increase the weatherization grants by $37 million (14%) and the SEP grants by $15 million (27%) over their FY2019 enacted levels.

Proposed Cuts in Energy R&D

Appropriations for DOE R&D on energy efficiency, renewable energy, nuclear energy, and fossil energy would be reduced from $4.445 billion in FY2019 to $1.729 billion (-61%) under the Administration's FY2020 budget request. Major proposed reductions include bioenergy technologies (-82%), vehicle technologies (-79%), natural gas technologies (-79%), advanced manufacturing (-75%), building technologies (-75%), wind energy (-74%), solar energy (-73%), geothermal technologies (-67%), and nuclear fuel cycle R&D (-66%). DOE says the proposed reductions would primarily affect the later stages of energy research, which tend to be the most costly. "The Budget focuses DOE resources toward early-stage R&D, where the Federal role is strongest, and reflects an increased reliance on the private sector to fund later-stage research, development, and commercialization of energy technologies," according to the FY2020 DOE request.7

The House did not approve most of the Administration's proposed energy R&D reductions, instead recommending an overall increase of $265 million (6%) from the FY2019 enacted level, to $4.710 billion. Specific increases include 12% for renewable energy and 10% for energy efficiency. Fossil and nuclear energy R&D would receive a less than 1% decrease under the House-passed bill. In response to the Administration's proposed focus on early-stage research, the House Appropriations Committee report said, "The Committee rejects this short-sighted and limited approach, which will ensure that technology advancements will remain in early-stage form and are unlikely to integrate the results of this early-stage research into the nation's energy system."

Nuclear Waste Management

The Administration's FY2020 budget request, for the first time since FY2010, would provide new funding for a proposed nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain, NV; similar Administration requests for the repository project were not included in the enacted funding measures for FY2018 and FY2019. Under the FY2020 request, DOE would receive $116 million to seek an NRC license for the repository and to develop interim nuclear waste storage capacity. NRC would receive $38.5 million to consider DOE's application. DOE's total of $116 million in nuclear waste funding would come from two appropriations accounts: $90 million from Nuclear Waste Disposal and $26 million from Defense Nuclear Waste Disposal (to pay for defense-related nuclear waste that would be disposed of at Yucca Mountain).

The House did not approve the Administration's FY2020 funding request for Yucca Mountain and interim storage. However, the House-passed bill included $25 million within the DOE nuclear energy program, according to the Appropriations Committee report, "for interim storage activities, including the initiation of a robust consolidated interim storage program." An amendment offered during committee markup by Representative Simpson to provide funding for Yucca Mountain licensing activities was defeated, 25-27. In the Appropriations Committee report's minority views, Representatives Granger and Simpson wrote, "Although the amendment did not pass, we will continue to work with Members on both sides of the aisle to address this issue as the appropriations process continues. It is beyond time we complete the Yucca Mountain license application process."

DOE submitted a license application for the Yucca Mountain repository in 2008, but NRC suspended consideration in 2011 for lack of funding. The Obama Administration had declared the Yucca Mountain site "unworkable" because of opposition from the state of Nevada. The House voted to provide the Yucca Mountain funding requested for FY2018 and a $100 million increase for FY2019, but the Senate Appropriations Committee did not include it for FY2018, and it was not included in the Senate-passed bill for FY2019. Also as in FY2018, the FY2019 Senate bill included an authorization for a pilot program to develop an interim nuclear waste storage facility at a voluntary site (§304). The enacted FY2019 appropriations measure did not include the House-passed funding for Yucca Mountain or the Senate's nuclear waste pilot program provisions. For more background, see CRS Report RL33461, Civilian Nuclear Waste Disposal, by Mark Holt.

Elimination of Energy Loans and Loan Guarantees

The FY2020 budget request would halt further loans and loan guarantees under DOE's Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Loan Program and the Title 17 Innovative Technology Loan Guarantee Program. Similar proposals to eliminate the programs in FY2018 and FY2019 were not enacted. The FY2020 budget request would also halt further loan guarantees under DOE's Tribal Energy Loan Guarantee Program. Under the FY2020 budget proposal, DOE would continue to administer its existing portfolio of loans and loan guarantees. Unused prior-year authority, or ceiling levels, for loan guarantee commitments would be rescinded, as well as $169.5 million in unspent appropriations to cover loan guarantee "subsidy costs" (which are primarily intended to cover potential losses). On March 22, 2019, after the FY2020 budget request had been submitted, DOE provided $3.7 billion in additional Title 17 loan guarantees for two new reactors under construction at the Vogtle nuclear plant in Georgia. The Vogtle project had previously received $8.3 billion in loan guarantees under the DOE program.8 The House voted to continue all three loan and loan guarantee programs in FY2020.

International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor

The Administration's request for DOE includes $107 million in FY2020 for the U.S. contribution to the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), which is under construction in France by a multinational consortium. "ITER will be the first fusion device to maintain fusion for long periods of time" and is to lay the technical foundation "for the commercial production of fusion-based electricity," according to the consortium's website.9 The FY2020 DOE appropriation request, 19% below the FY2019 enacted level of $132 million, would pay for components supplied by U.S. companies for the project, such as central solenoid superconducting magnet modules.

The House-passed bill includes $230 million for the U.S. contribution to ITER, a 74% increase from the FY2019 level. The House Appropriations Committee "continues to believe the ITER project represents an important step forward for energy sciences and has the potential to revolutionize the current understanding of fusion energy," according to the committee report.

ITER has long attracted congressional concern about management, schedule, and cost. The United States is to pay 9% of the project's construction costs, including contributions of components, cash, and personnel. Other collaborators in the project include the European Union, Russia, Japan, India, South Korea, and China. The total U.S. share of the cost was estimated in 2015 at between $4.0 billion and $6.5 billion, up from $1.45 billion to $2.2 billion in 2008.

Elimination of Advanced Research Projects Agency—Energy

The Trump Administration's FY2020 budget would eliminate the Advanced Research Projects Agency—Energy (ARPA-E) and rescind $287 million of the agency's unobligated balances. ARPA-E funds research on technologies that are determined to have potential to transform energy production, storage, and use.10 "This elimination facilitates opportunities to integrate the positive aspects of ARPA-E into DOE's applied energy research programs," according to the DOE request.11 The Administration also proposed to terminate ARPA-E in its FY2018 and FY2019 budget requests, but Congress increased the program's funding in both years.

Because ARPA-E provides advance funding for projects for up to three years, oversight and management of the program would still be required during a phaseout period. According to the Administration budget request, "ARPA-E will utilize the remainder of its unobligated balances to execute the multi-year termination of the program, with all operations ceasing by FY 2022."12 The House approved a 17% increase for ARPA-E over the FY2019 level, with the House Appropriations Committee stating in its report that it "strongly rejects the short-sighted proposal to terminate ARPA-E."

Weapons Activities

The FY2020 budget request for DOE Weapons Activities is 12% greater than the FY2019 enacted level ($12.409 billion vs. $11.100 billion). The House approved $11.761 billion for Weapons Activities, a 6% increase over the FY2019 level. Weapons Activities programs are carried out by the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), a semiautonomous agency within DOE.

Under Weapons Activities, the FY2020 budget request would increase funding for nuclear warhead life-extension programs (LEPs) by 10% ($2.1 billion vs $1.9 billion). The two most notable increases within that account are the funding request for W80-4 LEP, which would rise by 37% ($899 million vs. $655 million) and the initiation of funding for the W87-1 LEP.13 The increase in the request for the W80-4 warhead, which is due to be carried on the new long-range standoff weapon (a new cruise missile), apparently is the result of a new budget estimate, as the Department of Defense is not accelerating development of the missile. The FY2020 request seeks $112 million for the W87-1 warhead (formerly the Interoperable Warhead 1, or IW-I), which received $53 million in FY2019. This warhead is to be carried by the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent, a new land-based missile that is scheduled to enter the force in the 2030s. The House-passed bill would maintain level funding for the W87-1 warhead, a reduction of $59 million from the request.

The FY2020 budget request seeks $10 million for the W76-2 LEP, down from $65 million in FY2019. Work on this warhead is nearly complete. It is a low-yield modification of the current W76 warhead carried by U.S. submarine-launched ballistic missiles. It remains controversial in Congress despite its relatively low price tag. The House-passed bill would eliminate funding in FY2020 for the W76-2 but includes the requested amounts for the other LEPs.

In FY2020, NNSA is seeking $52 million, in the Stockpile Systems account, for surveillance efforts for the B83 gravity bomb, the most powerful bomb in the U.S. inventory. This effort represents a 47% increase over the $35 million request in FY2019. The Obama Administration had planned to retire this bomb, but the Trump Administration reversed that decision in its 2018 Nuclear Posture Review. This decision may also prove controversial, as several Senators have been vocal supporters of the plan to retire the bomb. The House-passed bill would reduce funding for the B83 bomb to $22 million, a 36% reduction from the FY2019 enacted level.

Within the Strategic Materials account in the NNSA budget proposal, funding for Plutonium Sustainment would increase 97%, from $361 million enacted for FY2019 to $712 million requested for FY2020. This increase would support the Administration's plans to produce plutonium pits (or cores) for nuclear warheads at two facilities—Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico and the Savannah River Site in South Carolina. The Administration is seeking $410 million to begin conceptual design and pre-Critical Decision (CD)-1 activities14 at Savannah River. The House-passed bill includes a $110 million (30%) increase in Plutonium Sustainment, about one-third of the increase requested by the Administration.

For more information, see CRS Report R44442, Energy and Water Development Appropriations: Nuclear Weapons Activities, by Amy F. Woolf.

Cleanup of Former Nuclear Sites

DOE's Office of Environmental Management (EM) is responsible for environmental cleanup and waste management at the department's nuclear facilities. The total FY2020 appropriations request for EM activities of $6.469 billion would be a decrease of $706 million (-10%) from FY2019. The budgetary components of the EM program are Defense Environmental Cleanup (-9%), Non-Defense Environmental Cleanup (-20%), and the Uranium Enrichment Decontamination and Decommissioning Fund (-15%). The House approved level funding of $7.175 billion for EM in FY2020.

The FY2020 request includes a proposal to transfer management of the Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program (FUSRAP) from USACE to the Office of Legacy Management (LM), the DOE office responsible for long-term stewardship of remediated sites. The FY2020 LM budget request includes $141 million for FUSRAP, down from $150 million appropriated to USACE for the program in FY2019. According to the DOE budget justification, "USACE will continue to conduct cleanup of FUSRAP sites on a reimbursable basis."15 The House-passed bill does not include the FUSRAP transfer and provides a 3% funding increase over the FY2019 enacted level within the USACE budget.

Bill Status and Recent Funding History

Table 1 indicates the steps during consideration of FY2020 Energy and Water Development appropriations. (For more details, see the CRS Appropriations Status Table at http://www.crs.gov/AppropriationsStatusTable/Index.)

|

Subcommittee Markup |

Final Approval |

||||||||

|

House |

Senate |

House Comm. |

House Passed |

Senate Comm. |

Senate Passed |

Conf. Report |

House |

Senate |

Public Law |

|

5/15/19 |

5/21/19 |

6/19/19 |

|||||||

Source: CRS Appropriations Status Table.

Table 2 includes budget totals for energy and water development appropriations enacted for FY2011 through FY2019, plus the FY2020 request.

Table 2. Energy and Water Development Appropriations,

FY2010-FY2019 and FY2020 Request

(budget authority in billions of current dollars)

|

FY2011 |

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

FY2020 Request |

|

31.7 |

32.7a |

30.7b |

34.1 |

34.8 |

37.3 |

38.5c |

43.2d |

44.7 |

38.0 |

Source: Compiled by CRS from totals provided by congressional budget documents. FY2020 request is from H.Rept. 116-83 and excludes subsequent scorekeeping adjustments.

Notes: Figures exclude permanent budget authorities and reflect rescissions.

a. Amount does not include $1.7 billion in emergency funding for the Corps of Engineers.

b. Amount does not include $5.4 billion in funding for USACE ($1.9 billion emergency and $3.5 billion additional).

c. Amount does not includes $1.0 billion in emergency funding for the USACE.

d. Amount does not include $17.4 billion in emergency funding for USACE ($17.4 billion) and Department of Energy programs ($22 million).

Description of Major Energy and Water Programs

The annual Energy and Water Development appropriations bill includes four titles: Title I—Corps of Engineers—Civil; Title II—Department of the Interior (Bureau of Reclamation and Central Utah Project); Title III—Department of Energy; and Title IV—Independent Agencies, as shown in Table 3. Major programs in the bill are described in this section in the approximate order they appear in the bill. Previous appropriations and budget recommendations for FY2020 are shown in the accompanying tables, and additional details about many of these programs are provided in separate CRS reports as indicated. For a discussion of current funding issues related to these programs, see "Funding Issues and Initiatives," above. Congressional clients may obtain more detailed information by contacting CRS analysts listed in CRS Report R42638, Appropriations: CRS Experts, by James M. Specht and Justin Murray.

Table 3. Energy and Water Development Appropriations Summary

(budget authority in millions of current dollars)

|

Title |

FY2016 Approp. |

FY2017 Approp. |

FY2018 Approp. |

FY2019 Request |

FY2019 Approp. |

FY2020 Request |

FY2020 House |

|

Title I: Corps of Engineers |

5,989 |

6,038 |

6,827 |

4,785 |

6,999 |

4,964 |

7,355 |

|

Title II: CUP and Reclamation |

1,275 |

1,317 |

1,480 |

1,057 |

1,565 |

1,120 |

1,647 |

|

Title III: Department of Energy |

29,744 |

31,182 |

34,569 |

30,395 |

35,709 |

32,198 |

37,084 |

|

Title IV: Independent Agencies |

342 |

349 |

392 |

353 |

390 |

370 |

390 |

|

General provisions |

21 |

||||||

|

Subtotal |

37,350 |

38,886 |

43,268 |

36,589 |

44,684 |

38,652 |

46,476 |

|

Rescissions and Scorekeeping Adjustmentsa |

-27 |

-436 |

-49 |

-249 |

-24 |

-696 |

-66 |

|

E&W Total |

37,323b |

38,450 |

43,219 |

36,340 |

44,660 |

37,956 |

46,410 |

Sources: H.R. 2740; CBO Current Status Report, H.Rept. 116-83; H.Rept. 115-929; S.Rept. 115-258; P.L. 115-31 and explanatory statement; S.Rept. 114-236; H.Rept. 114-532; Administration budget requests; H.Rept. 113-486; S.Rept. 114-54; H.R. 2029 explanatory statement, https://www.congress.gov/crec/2015/12/17/CREC-2015-12-17-bk2.pdf; H.R. 1625 explanatory statement, https://www.congress.gov/crec/2018/03/22/CREC-2018-03-22-bk2.pdf. Subtotals may include other adjustments.

a. Budget "scorekeeping" refers to official determinations of spending amounts for congressional budget enforcement purposes. These scorekeeping adjustments may include rescissions and offsetting revenues from various sources.

b. The energy and water development total in the Explanatory Statement includes $26.9 million in rescissions but excludes $111.1 million in additional scorekeeping adjustments that would reduce the grand total to $37.185 billion, the subcommittee allocation shown in S.Rept. 114-197. See Senate Committee on Appropriations, Comparative Statement of New Budget Authority FY2016, January 12, 2016, p. 11.

Agency Budget Justifications

FY2020 budget justifications for the largest agencies funded by the annual Energy and Water Development appropriations bill can be found through the following links:

- Title I, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Civil Works, http://www.usace.army.mil/Missions/CivilWorks/Budget

- Title II

- Bureau of Reclamation, https://www.usbr.gov/budget/

- Central Utah Project, https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/uploads/fy2020_cupca_budget_justification.pdf

- Title III, Department of Energy, https://www.energy.gov/cfo/downloads/fy-2020-budget-justification

- Title IV, Independent Agencies

- Appalachian Regional Commission, http://www.arc.gov/images/newsroom/publications/fy2020budget/FY2020PerformanceBudgetMar2019.pdf

- Nuclear Regulatory Commission, https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML1906/ML19065A279.pdf

- Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board, https://www.dnfsb.gov/about/congressional-budget-requests

- Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board, http://www.nwtrb.gov/about-us/plans

Army Corps of Engineers

USACE is an agency in the Department of Defense with both military and civilian responsibilities. Under its civil works program, which is funded by the Energy and Water appropriations bill, USACE plans, builds, operates, and in some cases maintains water resources facilities for coastal and inland navigation, riverine and coastal flood risk reduction, and aquatic ecosystem restoration.16 In recent decades, Congress has generally authorized Corps studies, construction projects, and other activities in omnibus water authorization bills, typically titled Water Resources Development Acts (WRDA), prior to funding them through appropriations legislation. Recent Congresses enacted the following omnibus water resources authorization acts: in June 2014, the Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014 (WRRDA, P.L. 113-121); in December 2016, the Water Resources Development Act of 2016 (Title I of P.L. 114-322, the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act [WIIN]); and in October 2018, the Water Resources Development Act of 2018 (Title I of P.L. 115-270, America's Water Infrastructure Act of 2018 [AWIA 2018]). These acts consisted largely of authorizations for new USACE projects, and they altered numerous USACE policies and procedures.17

Unlike in highways and municipal water infrastructure programs, federal funds for USACE are not distributed to states or projects based on formulas or delivered via competitive grants. Instead, USACE generally is directly involved in planning, designing, and managing the construction of projects that are cost-shared with nonfederal project sponsors.

Prior to FY2010, in addition to site-specific project funding included in the President's annual budget request for USACE, Congress, during the discretionary appropriations process, had identified many additional USACE projects to receive funding or had adjusted the funding levels for the projects identified in the President's request.18 Starting in the 112th Congress, site-specific project line items added or increased by Congress (i.e., earmarks) became subject to House and Senate earmark moratorium policies. As a result, Congress generally has not added funding at the project level since FY2010. In lieu of the project-based increases, Congress has included "additional funding" for select categories of USACE projects and provided direction and limitations on the use of these funds. For more information, CRS In Focus IF11137, Army Corps of Engineers: FY2020 Appropriations, by Nicole T. Carter and Anna E. Normand. Previous appropriations and the President's request for FY2020 are shown in Table 4.

|

Program |

FY2016 Approp. |

FY2017 Approp. |

FY2018 Approp. |

FY2019 Request |

FY2019 Approp. |

FY2020 Request |

FY2020 House |

|

Investigations and Planning |

121.0 |

121.0 |

123.0 |

82.0 |

125.0 |

77.0 |

140.0 |

|

Construction |

1,862.3 |

1,876.0 |

2,085.0 |

871.7a |

2,183.0 |

1,306.9a |

2,342.0 |

|

Mississippi River and Tributaries (MR&T) |

345.0 |

362.0 |

425.0 |

244.7a |

368.0 |

209.0a |

350.0 |

|

Operation and Maintenance (O&M) |

3,137.0 |

3,149.0 |

3,630.0 |

2,076.7a |

3,739.5 |

1,930.4a |

3,933.0 |

|

Regulatory |

200.0 |

200.0 |

200.0 |

200.0 |

200.0 |

200.0 |

210.0 |

|

General Expenses |

179.0 |

181.0 |

185.0 |

187.0 |

193.0 |

187.0 |

184.5 |

|

FUSRAPb |

112.0 |

112.0 |

139.0 |

120.0 |

150.0 |

0 |

155.0 |

|

Flood Control and Coastal Emergencies (FCCE) |

28.0 |

32.0 |

35.0 |

27.0 |

35.0 |

27.0 |

37.5 |

|

Office of the Asst. Secretary of the Army |

4.8 |

4.8 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

3.0 |

|

Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund |

965.1 |

965.0 |

|||||

|

Inland Waterways Trust Fund |

5.3 |

55.5 |

|||||

|

Total Title I |

5,989.0 |

6,037.8 |

6,827.0 |

4,784.6 |

6,998.5 |

4,963.8 |

7,355.0 |

Sources: H.R. 2740; CBO Current Status Report; H.Rept. 116-83; FY2020 Budget Justification; H.Rept. 115-929; S.Rept. 115-258; S.Rept. 115-132; H.Rept. 115-230; P.L. 115-31 and explanatory statement; S.Rept. 114-236; H.Rept. 114-532; FY2016 budget request and Work Plans for FY2013, FY2014, and FY2015; S.Rept. 114-54; P.L. 113-2; H.R. 2029 explanatory statement; H.R. 1625 explanatory statement, https://www.congress.gov/crec/2018/03/22/CREC-2018-03-22-bk2.pdf. FY2019 and FY2020 request numbers can be found at https://www.usace.army.mil/Missions/Civil-Works/Budget/.

a. In the Administration's FY2019 and FY2020 requests, some activities that would have previously been funded in these accounts were proposed to be funded through new Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund (HMTF) and Inland Waterway Trust Fund (IWTF) budget accounts. That is, the Administration proposed establishing USACE budget accounts for the HMTF and IWTF to fund eligible USACE activities directly (rather than the current practice of having USACE be reimbursed for HMTF- and IWTF-eligible expenses). For example, HMTF-eligible maintenance dredging would no longer be funded by the O&M account and reimbursed by using HMTF collections; instead the dredging would be funded directly from an HMTF account.

b. Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program. The Administration's FY2020 request proposes transferring administration and funding of FUSRAP to the DOE Office of Legacy Management.

Bureau of Reclamation and Central Utah Project

Most of the large dams and water diversion structures in the West were built by, or with the assistance of, the Bureau of Reclamation. While the Corps of Engineers built hundreds of flood control and navigation projects, Reclamation's original mission was to develop water supplies, primarily for irrigation to reclaim arid lands in the West for farming and ranching. Reclamation has evolved into an agency that assists in meeting the water demands in the West while working to protect the environment and the public's investment in Reclamation infrastructure. The agency's municipal and industrial water deliveries have more than doubled since 1970.

Today, Reclamation manages hundreds of dams and diversion projects, including more than 300 storage reservoirs, in 17 western states. These projects provide water to approximately 10 million acres of farmland and 31 million people. Reclamation is the largest wholesale supplier of water in the 17 western states and the second-largest hydroelectric power producer in the nation. Reclamation facilities also provide substantial flood control, recreation, and other benefits. Reclamation facility operations are often controversial, particularly for their effect on fish and wildlife species and because of conflicts among competing water users during drought conditions.

As with the Corps of Engineers, the Reclamation budget is made up largely of individual project funding lines, rather than general programs that would not be covered by congressional earmark requirements. Therefore, as with USACE, these Reclamation projects have often been subject to earmark disclosure rules. The current moratorium on earmarks restricts congressional steering of money directly toward specific Reclamation projects.

Reclamation's single largest account, Water and Related Resources, encompasses the agency's traditional programs and projects, including construction, operations and maintenance, dam safety, and ecosystem restoration, among others.19 Reclamation also typically requests funds in a number of smaller accounts, and has proposed additional accounts in recent years.

Implementation and oversight of the Central Utah Project (CUP), also funded by Title II, is conducted by a separate office within the Department of the Interior.20

For more information, see CRS In Focus IF11158, Bureau of Reclamation: FY2020 Appropriations, by Charles V. Stern. Previous appropriations and recommendations for FY2020 are shown in Table 5.

|

Program |

FY2016 Approp |

FY2017 Approp |

FY2018 Approp |

FY2019 Request |

FY2019 Approp |

FY2020 Request |

FY2020 House |

|

Water and Related Resources |

1,119.0 |

1,155.9 |

1,332.1 |

891.0 |

1,392.0 |

962.0 |

1,481.0 |

|

Policy and Administration |

59.5 |

59.0 |

59.0 |

61.0 |

61.0 |

60.0 |

58.0 |

|

CVP Restoration Fund (CVPRF) |

49.5 |

55.6 |

41.4 |

62.0 |

62.0 |

54.9 |

54.9 |

|

Calif. Bay-Delta (CALFED) |

37.0 |

36.0 |

37.0 |

35.0 |

35.0 |

33.0 |

33.0 |

|

Gross Current Reclamation Authority |

1,265.0 |

1,306.5 |

1,469.5 |

1,049.0 |

1,550.0 |

1,109.9 |

1,626.9 |

|

Central Utah Project (CUP) Completion |

10.0 |

10.5 |

10.5 |

8.0 |

15.0 |

10.0 |

20.0 |

|

Total, Title II Current Authority (CUP and Reclamation) |

1,275.0 |

1,317.0 |

1,480.0 |

1,057.0 |

1,565.0 |

1,119.9 |

1,646.9 |

Sources: H.R. 2740; CBO Current Status Report; H.Rept. 116-83; FY2020 Budget Justifications; H.Rept. 115-929; S.Rept. 115-258; S.Rept. 115-132; H.Rept. 115-230; P.L. 115-31 and explanatory statement; S.Rept. 114-236; H.Rept. 114-532; FY2018 and FY2017 budget requests; H.R. 83 Explanatory Statement; S.Rept. 114-54; H.R. 2029 explanatory statement; H.R. 1625 explanatory statement, https://www.congress.gov/crec/2018/03/22/CREC-2018-03-22-bk2.pdf. Excludes offsets and permanent appropriations.

Notes: Columns may not add due to rounding. CVP = Central Valley Project.

Department of Energy

The Energy and Water Development bill has funded all DOE programs since FY2005. Major DOE activities include (1) R&D on renewable energy, energy efficiency, nuclear power, fossil energy, and electricity; (2) the Strategic Petroleum Reserve; (3) energy statistics; (4) general science; (5) environmental cleanup; and (6) nuclear weapons and nonproliferation programs. Table 6 provides the recent funding history for DOE programs, which are briefly described further below.

|

FY2016 Approp. |

FY2017 Approp. |

FY2018 Approp. |

FY2019 Request |

FY2019 Approp. |

FY2020 Request |

FY2020 House |

|

|

ENERGY PROGRAMS |

|||||||

|

Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy |

2,069.2 |

2,090.2 |

2,321.8 |

695.6 |

2,379.0 |

343.0 |

2,659.7 |

|

Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliabilityd |

206.0 |

230.0 |

248.3 |

||||

|

Electricity Delivery |

61.3 |

156.0 |

182.5 |

200.0 |

|||

|

Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emerg. Resp. |

95.8 |

120.0 |

156.5 |

153.0 |

|||

|

Nuclear Energy |

986.2 |

1,016.6 |

1,205.1 |

757.1 |

1,326.1 |

824.0 |

1,320.8 |

|

Fossil Energy R&D |

632.0 |

668.0 |

726.8 |

502.1 |

740.0 |

562.0 |

738.6 |

|

Naval Petroleum and Oil Shale Reserves |

17.5 |

15.0 |

4.9 |

10.0 |

10.0 |

14.0 |

14.0 |

|

Strategic Petroleum Reserve |

212.0 |

223.0 |

260.4 |

-124.9 |

245.0 |

105.0 |

224.2 |

|

Northeast Home Heating Oil Reserve |

7.6 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

10.0 |

10.0 |

-90.0 |

10.0 |

|

Energy Information Administration |

122.0 |

122.0 |

125.0 |

115.0 |

125.0 |

118.0 |

128.0 |

|

Non-Defense Environmental Cleanup |

255.0 |

247.0 |

298.4 |

218.4 |

310.0 |

247.5 |

308.0 |

|

Uranium Enrichment Decontamination and Decommissioning Fund |

673.7 |

768.0 |

840.0 |

752.8 |

841.1 |

715.1 |

873.5 |

|

Science |

5,350.2 |

5,392.0 |

6,259.9 |

5,391.0 |

6,585.0 |

5,546.0 |

6,870.0 |

|

Advanced Research Projects Agency—Energy (ARPA-E) |

291.0 |

306.0 |

353.3 |

0 |

366.0 |

-287.0 |

428.0 |

|

Nuclear Waste Disposal |

0 |

0 |

0 |

90.0 |

0 |

90.0 |

0 |

|

Departmental Admin. (net) |

131.0 |

143.0 |

189.7 |

139.5 |

165.9 |

117.5 |

150.0 |

|

Office of Inspector General |

46.4 |

44.4 |

49.0 |

51.3 |

51.3 |

54.2 |

54.2 |

|

International Affairs |

0 |

36.1 |

0 |

||||

|

Office of Indian Energy |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

18.0 |

8.0 |

27.0 |

|

Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Loans |

6.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

1.0 |

5.0 |

0 |

5.0 |

|

Title 17 Loan Guarantee |

17.0 |

7.0 |

23.0 |

-245.0 |

18.0 |

-384.7 |

30.0 |

|

Tribal Indian Energy Loan Guarantee |

0 |

0a |

1.0 |

-8.5 |

1.0 |

-8.5 |

1.0 |

|

TOTAL, ENERGY PROGRAMS |

11,026.6 |

11,283.7 |

12,918.0 |

8,512.5 |

13,472.4 |

8,349.3 |

14,195.0 |

|

DEFENSE ACTIVITIES |

|||||||

|

National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) |

|||||||

|

Weapons Activities |

8,846.9 |

9,245.6 |

10,642.1 |

11,017.1 |

11,100.0 |

12,408.6 |

11,760.8 |

|

Nuclear Nonproliferation |

1,940.3 |

1,882.9 |

1,999.2 |

1,862.8 |

1,930.0 |

1,993.3 |

2,079.9 |

|

Naval Reactors |

1,375.5 |

1,419.8 |

1,620.0 |

1,788.6 |

1,788.6 |

1,648.4 |

1,628.6 |

|

Office of Admin./Salaries and Expenses |

363.8 |

390.0 |

407.6 |

422.5 |

410.0 |

434.7 |

425.0 |

|

Total, NNSA |

12,526.5 |

12,938.3 |

14,669.0 |

15,091.1 |

15,228.6 |

16,485.0 |

15,894.3 |

|

Defense Environmental Cleanup |

5,289.7 |

5,405.0 |

5,988.0 |

5,630.2 |

6,024.0 |

5,506.5 |

5,993.7 |

|

Defense Uranium Enrichment D&Db |

0 |

563.0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Other Defense Activities |

776.4 |

784.0 |

840.0 |

853.3 |

860.3 |

1,035.3c |

901.3 |

|

Defense Nuclear Waste Disposal |

0 |

0 |

0 |

30.0 |

0 |

26.0 |

0 |

|

TOTAL, DEFENSE ACTIVITIES |

18,592.7 |

19,690.3 |

21,497.0 |

21,604.6 |

22,112.9 |

23,052.8 |

22,789.2 |

|

POWER MARKETING ADMINISTRATION (PMAs) |

|||||||

|

Southwestern |

11.4 |

11.1 |

11.4 |

10.4 |

10.4 |

10.4 |

10.4 |

|

Western |

93.4 |

95.6 |

93.4 |

89.4 |

89.4 |

89.2 |

89.4 |

|

Falcon and Amistad O&M |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

|

TOTAL, PMAs |

105.0 |

106.9 |

105.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

99.8 |

100.0 |

|

General provisions |

-334.8 |

-71.0 |

|||||

|

DOE total appropriations |

29,744.2 |

31,181.8 |

34,569.1 |

30,394.6 |

35,708.9 |

32,197.8 |

37,084.2 |

|

Offsets and adjustments |

-26.9 |

-435.8 |

-49.0 |

-248.5 |

-23.6 |

-695.9 |

|

|

Total, DOE |

29,717.3 |

30,746.0 |

34,520.1 |

30,146.1 |

35,685.3 |

31,501.9 |

37,084.2 |

Sources: H.R. 2740; CBO Current Status Report; H.Rept. 116-83; FY2020 Budget Justification; H.Rept. 115-929; S.Rept. 115-258; S.Rept. 115-132; H.Rept. 115-230; P.L. 115-31 and explanatory statement; S.Rept. 114-236; H.Rept. 114-532; FY2018 and FY2017 budget requests; H.R. 83 Explanatory Statement; FY2015 budget request; H.Rept. 113-486; S.Rept. 114-54; H.R. 2029 explanatory statement; H.R. 1625 explanatory statement, https://www.congress.gov/crec/2018/03/22/CREC-2018-03-22-bk2.pdf.

Notes: Columns may not add due to rounding.

a. Appropriation of $9.0 million entirely offset by rescission.

b. The amounts appropriated for Defense Uranium Enrichment Decontamination and Decommissioning (D&D) are transferred to the Uranium Enrichment Decontamination and Decommissioning Fund, and are treated as receipts that increase the balance of that fund available for appropriation in subsequent annual appropriations acts. Until appropriated from the fund, the amounts for Defense Uranium Enrichment D&D are not available to DOE for obligation to support D&D of federal uranium enrichment facilities.

c. Includes $141 million for the Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program that is currently managed USACE.

d. The Office of Electric Delivery and Energy Reliability was split in FY2019 into the Office of Electricity Delivery and the Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response.

Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy

DOE's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) conducts research and development on transportation energy technology, energy efficiency in buildings and manufacturing processes, and the production of solar, wind, geothermal, and other renewable energy. EERE also administers formula grants to states for making energy efficiency improvements to low-income housing units and for state energy planning.

The Sustainable Transportation program area includes electric vehicles, vehicle efficiency, and alternative fuels. DOE's electric vehicle program aims to "reduce the cost of electric vehicle batteries by more than half, to less than $100/kWh [kilowatt-hour] (ultimate goal is $80/kWh), increase range to 300 miles, and decrease charge time to 15 minutes or less." DOE's vehicle fuel cell program is focusing on the costs of fuel cells and their hydrogen fuel. According to the FY2020 budget request, "To be cost competitive with gasoline-powered internal combustion engines on a cents-per-mile driven basis, the cost of hydrogen delivered and dispensed needs to be less than $4/gge [gasoline gallon equivalent] (untaxed), and the cost of a durable fuel cell system to be less than $40/kW." Bioenergy goals include the development of "drop-in" fuels—fuels that would be largely compatible with existing energy infrastructure and vehicles, with a goal of $3/gge.21

Renewable power programs focus on electricity generation from solar, wind, water, and geothermal sources. The solar energy program has a goal of achieving, by 2030, costs of 3 cents per kWh for unsubsidized, utility-scale photovoltaics (PV). Wind R&D is to focus on early-stage research and testing to reduce costs and improve performance and reliability. The geothermal program is to focus on developing "enhanced geothermal systems" with an electricity generation cost target of 20.8 cents/kWh by 2022.22

In the energy efficiency program area, the advanced manufacturing program focuses on improving the energy efficiency of manufacturing processes and on the manufacturing of energy-related products. The building technologies program includes R&D on lighting, space conditioning, windows, and control technologies to reduce building energy-use intensity. The energy efficiency program also provides weatherization grants to states for improving the energy efficiency of low-income housing units and state energy planning grants.23

For more details, see CRS Report R44980, DOE's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE): Appropriations Status, by Corrie E. Clark.

Electricity Delivery, Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Energy Reliability

The Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response (CESER) was created from programs that were previously part of the Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability. The programs that were not moved into CESER became part of the DOE Office of Electricity (OE).24

OE's mission is to lead DOE efforts "to strengthen, transform, and improve energy infrastructure so that consumers have access to secure and resilient sources of energy." Major priorities of OE are developing a model of North American energy vulnerabilities, pursuing megawatt-scale electricity storage, integrating electric power system sensing technology, and analyzing electricity policy issues.25 The office also includes the DOE power marketing administrations, which are funded from separate appropriations accounts.

CESER is the federal government's lead entity for energy sector-specific responses to energy security emergencies—whether caused by physical infrastructure problems or by cybersecurity issues. The office conducts R&D on energy infrastructure security technology; provides energy sector security guidelines, training, and technical assistance; and enhances energy sector emergency preparedness and response.26

DOE's Multiyear Plan for Energy Sector Cybersecurity describes the department's strategy to "strengthen today's energy delivery systems by working with our partners to address growing threats and promote continuous improvement, and develop game-changing solutions that will create inherently secure, resilient, and self-defending energy systems for tomorrow."27 The plan includes three goals that DOE has established for energy sector cybersecurity:

- strengthen energy sector cybersecurity preparedness;

- coordinate cyber incident response and recovery; and

- accelerate research, development, and demonstration (RD&D) of resilient energy delivery systems.

Nuclear Energy

DOE's Office of Nuclear Energy (NE) "focuses on three major mission areas: the nation's existing nuclear fleet, the development of advanced nuclear reactor concepts, and fuel cycle technologies," according to DOE's FY2020 budget justification. It calls nuclear energy "a key element of United States energy independence, energy dominance, electricity grid resiliency, national security, and clean baseload power."28

The Reactor Concepts program area includes research on advanced reactors, including advanced small modular reactors, and research to enhance the "sustainability" of existing commercial light water reactors. Advanced reactor research focuses on "Generation IV" reactors, as opposed to the existing fleet of commercial light water reactors, which are generally classified as generations II and III. R&D under this program focuses on advanced coolants, fuels, materials, and other technology areas that could apply to a variety of advanced reactors. To help develop those technologies, the Reactor Concepts program is developing a Versatile Test Reactor that would allow fuels and materials to be tested in a fast neutron environment (in which neutrons would not be slowed by water, graphite, or other "moderators"). Research on extending the life of existing commercial light water reactors beyond 60 years, the maximum operating period currently licensed by NRC, is being conducted by this program with industry cost-sharing.

The Fuel Cycle Research and Development program includes generic research on nuclear waste management and disposal. One of the program's primary activities is the development of technologies to separate the radioactive constituents of spent fuel for reuse or solidifying into stable waste forms. Other major research areas in the Fuel Cycle R&D program include the development of accident-tolerant fuels for existing commercial reactors, evaluation of fuel cycle options, and development of improved technologies to prevent diversion of nuclear materials for weapons. The program is also developing sources of high-assay low enriched uranium (HALEU), in which uranium is enriched to between 5% and 20% in the fissile isotope U-235, for potential use in advanced reactors. For more information, see CRS Report R45706, Advanced Nuclear Reactors: Technology Overview and Current Issues, by Danielle A. Arostegui and Mark Holt.

Fossil Energy Research and Development

Much of DOE's Fossil Energy R&D Program focuses on carbon capture and storage for power plants fueled by coal and natural gas. Major activities include Advanced Coal Energy Systems and Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS); Natural Gas Technologies; and Unconventional Fossil Energy Technologies from Petroleum—Oil Technologies.

Advanced Coal Energy Systems includes R&D on modular coal-gasification systems, advanced turbines, solid oxide fuel cells, advanced sensors and controls, and power generation efficiency.

Elements of the CCUS program include the following:

- Carbon Capture subprogram for separating CO2 in both precombustion and postcombustion systems;

- Carbon Utilization subprogram for R&D on technologies to convert carbon to marketable products, such as chemicals and polymers; and

- Carbon Storage subprogram on long-term geologic storage of CO2, focusing on saline formations, oil and natural gas reservoirs, unmineable coal seams, basalts, and organic shales.29

For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10589, FY2019 Funding for CCS and Other DOE Fossil Energy R&D, by Peter Folger, and CRS Report R44472, Funding for Carbon Capture and Sequestration (CCS) at DOE: In Brief, by Peter Folger.

Strategic Petroleum Reserve

The Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR), authorized by the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (P.L. 94-163) in 1975, consists of caverns built within naturally occurring salt domes in Louisiana and Texas. The SPR provides strategic and economic security against foreign and domestic disruptions in U.S. oil supplies via an emergency stockpile of crude oil. The program fulfills U.S. obligations under the International Energy Program, which avails the United States of International Energy Agency (IEA) assistance through its coordinated energy emergency response plans, and provides a deterrent against energy supply disruptions. DOE has been conducting a major maintenance program to address aging infrastructure and a deferred maintenance backlog at SPR facilities.

The federal government has not purchased oil for the SPR since 1994. Beginning in 2000, additions to the SPR were made with royalty-in-kind (RIK) oil acquired by DOE in lieu of cash royalties paid on production from federal offshore leases. In September 2009, the Secretary of the Interior announced a phaseout of the RIK Program. By early 2010, the SPR's capacity reached 727 million barrels.30 A series of oil sales and purchases since then have resulted in a net reduction of the SPR inventory. Currently, the SPR contains about 645 million barrels.31

Congress has enacted several laws since 2015 that mandate sales of SPR oil, including the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-74), the Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act (P.L. 114-94), the 21st Century Cures Act of 2016 (P.L. 114-255), the 2017 Tax Revision (P.L. 115-97), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123), and the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018. Broadly considered, this legislation requires oil to be sold from the reserve over the period FY2017 through FY2027, totaling 266 million barrels.

For more information, see CRS Report R45577, Strategic Petroleum Reserve: Mandated Sales and Reform, by Robert Pirog, and CRS In Focus IF10869, Reconsidering the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, by Robert Pirog.

Science and ARPA-E

The DOE Office of Science conducts basic research in six program areas: advanced scientific computing research, basic energy sciences, biological and environmental research, fusion energy sciences, high-energy physics, and nuclear physics. According to DOE's FY2020 budget justification, the Office of Science "is the Nation's largest Federal sponsor of basic research in the physical sciences and the lead Federal agency supporting fundamental scientific research for our Nation's energy future."32

DOE's Advanced Scientific Computing Research (ASCR) program focuses on developing and maintaining computing and networking capabilities for science and research in applied mathematics, computer science, and advanced networking. The program plays a key role in the DOE-wide effort to advance the development of exascale computing, which seeks to build a computer that can solve scientific problems 1,000 times faster than today's best machines. DOE has asserted that the department is on a path to have a capable exascale machine by the early 2020s.

Basic Energy Sciences (BES), the largest program area in the Office of Science, focuses on understanding, predicting, and ultimately controlling matter and energy at the electronic, atomic, and molecular levels. The program supports research in disciplines such as condensed matter and materials physics, chemistry, and geosciences. BES also provides funding for scientific user facilities (e.g., the National Synchrotron Light Source II, and the Linac Coherent Light Source-II), and certain DOE research centers and hubs (e.g., Energy Frontier Research Centers, as well as the Batteries and Energy Storage and Fuels from Sunlight Energy Innovation Hubs).

Biological and Environmental Research (BER) seeks a predictive understanding of complex biological, climate, and environmental systems across a continuum from the small scale (e.g., genomic research) to the large (e.g., Earth systems and climate). Within BER, Biological Systems Science focuses on plant and microbial systems, while Biological and Environmental Research supports climate-relevant atmospheric and ecosystem modeling and research. BER facilities and centers include four Bioenergy Research Centers and the Environmental Molecular Science Laboratory at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Fusion Energy Sciences (FES) seeks to increase understanding of the behavior of matter at very high temperatures and to establish the science needed to develop a fusion energy source. FES provides funding for the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) project, a multinational effort to design and build an experimental fusion reactor. According to DOE, ITER "aims to provide fusion power output approaching reactor levels of hundreds of megawatts, for hundreds of seconds."33 However, many U.S. analysts have expressed concern about ITER's cost, schedule, and management, as well as the budgetary impact on domestic fusion research.34

The High Energy Physics (HEP) program conducts research on the fundamental constituents of matter and energy, including studies of dark energy and the search for dark matter. Nuclear Physics supports research on the nature of matter, including its basic constituents and their interactions. A major project in the Nuclear Physics program is the construction of the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams at Michigan State University.

A separate DOE office, the Advanced Research Projects Agency—Energy (ARPA-E), was authorized by the America COMPETES Act (P.L. 110-69) to support transformational energy technology research projects. DOE budget documents describe ARPA-E's mission as overcoming long-term, high-risk technological barriers to the development of energy technologies.

For more details, see CRS Report R45715, Federal Research and Development (R&D) Funding: FY2020, coordinated by John F. Sargent Jr.

Loan Guarantees and Direct Loans

DOE's Loan Programs Office provides loan guarantees for projects that deploy specified energy technologies, as authorized by Title 17 of the Energy Policy Act of 2005 (EPACT05, P.L. 109-58), direct loans for advanced vehicle manufacturing technologies, and loan guarantees for tribal energy projects. Section 1703 of the act authorizes loan guarantees for advanced energy technologies that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and Section 1705 established a temporary program for renewable energy and energy efficiency projects.

Title 17 allows DOE to provide loan guarantees for up to 80% of construction costs for eligible energy projects. Successful applicants must pay an up-front fee, or "subsidy cost," to cover potential losses under the loan guarantee program. Under the loan guarantee agreements, the federal government would repay all covered loans if the borrower defaulted. Such guarantees would reduce the risk to lenders and allow them to provide financing at below-market interest rates. The following is a summary of loan guarantee amounts that have been authorized (loan guarantee ceilings) for various technologies:

- $8.3 billion for nonnuclear technologies under Section 1703;

- $2.0 billion for unspecified projects from FY2007 under Section 1703;

- $18.5 billion for nuclear power plants ($12.0 billion committed) under Section 1703;

- $4 billion for loan guarantees for uranium enrichment plants under Section 1703;

- $1.18 billion for renewable energy and energy efficiency projects under Section 1703, in addition to other loan guarantee ceilings, which can include applications that were pending under Section 1705 before it expired; and

- In addition to the loan guarantee ceilings above, an appropriation of $161 million was provided for subsidy costs for renewable energy and energy efficiency loan guarantees under Section 1703. If the subsidy costs averaged 10% of the loan guarantees, this funding could leverage loan guarantees totaling about $1.6 billion.

The only loan guarantees under Section 1703 have been $8.3 billion in guarantees provided to the consortium building two new reactors at the Vogtle plant in Georgia. DOE committed an additional $3.7 billion in loan guarantees for the Vogtle project on March 22, 2019.35 Another nuclear loan guarantee is being sought by NuScale Power to build a small modular reactor in Idaho.36

Nuclear Weapons Activities

In the absence of explosive testing of nuclear weapons, the United States has adopted a science-based program to maintain and sustain confidence in the reliability of the U.S. nuclear stockpile. Congress established the Stockpile Stewardship Program in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1994 (P.L. 103-160). The goal of the program, as amended by the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010 (P.L. 111-84, §3111), is to ensure "that the nuclear weapons stockpile is safe, secure, and reliable without the use of underground nuclear weapons testing." The program is operated by NNSA, a semiautonomous agency within DOE established by the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2000 (P.L. 106-65, Title XXXII). NNSA implements the Stockpile Stewardship Program through the activities funded by the Weapons Activities account in the NNSA budget.

Most of NNSA's weapons activities take place at the nuclear weapons complex, which consists of three laboratories (Los Alamos National Laboratory, NM; Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, CA; and Sandia National Laboratories, NM and CA); four production sites (Kansas City National Security Campus, MO; Pantex Plant, TX; Savannah River Site, SC; and Y-12 National Security Complex, TN); and the Nevada National Security Site (formerly the Nevada Test Site). NNSA manages and sets policy for the weapons complex; contractors to NNSA operate the eight sites.37 Radiological activities at these sites are subject to oversight and recommendations by the independent Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board, funded by Title IV of the annual Energy and Water Development appropriations bill.

There are three major program areas in the Weapons Activities account:

Directed Stockpile Work includes the life extension programs (LEPs) on existing warheads and stockpile services programs that monitor their condition; and maintaining warheads through repairs, refurbishment, and modifications. It also includes funding for research and development in support of specific warheads, and dismantlement of warheads that have been removed from the stockpile. This last activity received more significant funding as the number of warheads in the U.S. stockpile declined after the Cold War; it also provides a source for critical components for warheads remaining in the stockpile. Directed Stockpile Work also involves programs that work on the materials needed for nuclear warheads, including the plutonium pits that are the core of the weapons.

Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E) includes five programs that focus on "efforts to develop and maintain critical capabilities, tools, and processes needed to support science based stockpile stewardship, refurbishment, and continued certification of the stockpile over the long-term in the absence of underground nuclear testing." This area includes operation of some large experimental facilities, such as the National Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Infrastructure and Operations has, as its main funding elements, material recycle and recovery, recapitalization of facilities, and construction of facilities. The latter include two major projects that have generated congressional controversy: the Uranium Processing Facility (UPF) at the Y-12 National Security Complex and the Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement (CMRR) Project, which deals with plutonium, at Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Nuclear Weapons Activities also has several smaller programs, including the following:

- Secure Transportation Asset, providing for safe and secure transport of nuclear weapons, components, and materials;

- Defense Nuclear Security, providing operations, maintenance, and construction funds for protective forces, physical security systems, personnel security, and related activities; and

- Information Technology and Cybersecurity, whose elements include cybersecurity, secure enterprise computing, and Federal Unclassified Information Technology.

For more information, see CRS Report R44442, Energy and Water Development Appropriations: Nuclear Weapons Activities, by Amy F. Woolf, and CRS Report R45306, The U.S. Nuclear Weapons Complex: Overview of Department of Energy Sites, by Amy F. Woolf and James D. Werner.

Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation

DOE's nonproliferation and national security programs provide technical capabilities to support U.S. efforts to prevent, detect, and counter the spread of nuclear weapons worldwide. These programs are administered by NNSA's Office of Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation.

The Materials Management and Minimization program conducts activities to minimize and, where possible, eliminate stockpiles of weapons-useable material around the world. Major activities include conversion of reactors that use highly enriched uranium (useable for weapons) to low-enriched uranium, removal and consolidation of nuclear material stockpiles, and disposition of excess nuclear materials.

Global Materials Security has three major program elements. International Nuclear Security focuses on increasing the security of vulnerable stockpiles of nuclear material in other countries. Radiological Security promotes the worldwide reduction and security of radioactive sources, including the removal of surplus sources and substitution of technologies that do not use radioactive materials. Nuclear Smuggling Detection and Deterrence works to improve the capability of other countries to halt illicit trafficking of nuclear materials.

Nonproliferation and Arms Control works to "to support U.S. nonproliferation and arms control objectives to prevent proliferation, ensure peaceful nuclear uses, and enable verifiable nuclear reductions," according to the FY2020 DOE justification.38 This program conducts reviews of nuclear export applications and technology transfer authorizations, implements treaty obligations, and analyzes nonproliferation policies and proposals.

Other programs under Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation include research and development and construction, which advances nuclear detection and nuclear forensics technologies. Nuclear Counterterrorism and Incident Response provides "interagency policy, contingency planning, training, and capacity building" to counter nuclear terrorism and strengthen incident response capabilities, according to the FY2020 budget justification.39

Cleanup of Former Nuclear Weapons Production and Research Sites

The development and production of nuclear weapons during half a century since the beginning of the Manhattan Project resulted in a waste and contamination legacy managed by DOE that continues to present substantial challenges today. DOE also manages legacy environmental contamination at sites used for nondefense nuclear research. In 1989, DOE established the Office of Environmental Management primarily to consolidate its responsibilities for the cleanup of former nuclear weapons production sites that had been administered under multiple offices.40

DOE's nuclear cleanup efforts are broad in scope and include the disposal of large quantities of radioactive and other hazardous wastes generated over decades; management and disposal of surplus nuclear materials; remediation of extensive contamination in soil and groundwater; decontamination and decommissioning of excess buildings and facilities; and safeguarding, securing, and maintaining facilities while cleanup is underway.41 DOE's cleanup of nuclear research sites adds a nondefense component to the EM's mission, albeit smaller in terms of the scope of their cleanup and associated funding.42

DOE has identified more than 100 separate sites in over 30 states that historically were involved in the production of nuclear weapons and nuclear energy research for civilian purposes.43 The geographic scope of these sites is substantial, collectively encompassing a land area of approximately 2 million acres. Cleanup remedies are in place and operational at the majority of these sites. Responsibility for the long-term stewardship of them has been transferred to the Office of Legacy Management and other offices within DOE for the operation and maintenance of cleanup remedies and monitoring.44 Some of the smaller sites for which DOE initially was responsible were transferred to the Army Corps of Engineers in 1997 under the Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program (FUSRAP). Once USACE completes the cleanup of a FUSRAP site, it is transferred back to DOE for long-term stewardship under the Office of Legacy Management, which is separate from EM and has its own funding account.

Three appropriations accounts fund the Office of Environmental Management. The Defense Environmental Cleanup account is the largest in terms of funding, and it finances the cleanup of former nuclear weapons production sites. The Non-Defense Environmental Cleanup account funds the cleanup of federal nuclear energy research sites. Title XI of the Energy Policy Act of 1992 (P.L. 102-486) established the Uranium Enrichment Decontamination and Decommissioning Fund to pay for the cleanup of three federal facilities that enriched uranium for national defense and civilian purposes.45 Those facilities are located near Paducah, KY; Piketon, OH (Portsmouth plant); and Oak Ridge, TN. Title X of P.L. 102-486 authorized the reimbursement of uranium and thorium producers for their costs of cleaning up contamination attributable to uranium and thorium sold to the federal government.46

The adequacy of funding for the Office of Environmental Management to attain cleanup milestones across the entire site inventory has been a recurring issue. Cleanup milestones are enforceable measures incorporated into compliance agreements negotiated among DOE, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the states. These milestones establish time frames for the completion of specific actions to satisfy applicable requirements at individual sites.47

Power Marketing Administrations

DOE's four Power Marketing Administrations were established to sell the power generated by the dams operated by the Bureau of Reclamation and the Army Corps of Engineers. Preference in the sale of power is given to publicly owned and cooperatively owned utilities. The PMAs operate in 34 states; their assets consist primarily of transmission infrastructure in the form of more than 33,000 miles of high voltage transmission lines and 587 substations. PMA customers are responsible for repaying all power program expenses, plus the interest on capital projects. Since FY2011, power revenues associated with the PMAs have been classified as discretionary offsetting receipts (i.e., receipts that are available for spending by the PMAs), thus the agencies are sometimes noted as having a "net-zero" spending authority. Only the capital expenses of WAPA and SWPA require appropriations from Congress.

For more information, see CRS Report R45548, The Power Marketing Administrations: Background and Current Issues, by Richard J. Campbell.

Independent Agencies