Introduction

This report provides both an overview of the FY2019 defense appropriations act (P.L. 115-245) and access to other CRS products providing additional detail and analysis on particular issues and programs dealt with by that law.

The Overview section of the report immediately following this Introduction covers the legislative history of the bill and the strategic and budgetary context within which is was debated. Subsequent sections of the report detail the bill's treatment of specific issues including procurement of various types of weapons. Each section dealing with procurement of a certain type of weapon includes a table presenting basic budget information and links to any relevant CRS product.

Overview

For FY2019, the Trump Administration requested $668.4 billion to fund programs falling within the scope of the annual defense appropriations act.1 This included $67.9 billion to be designated by Congress and the President as funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) and $599.4 billion for DOD's base budget, comprising all operations not designated as OCO. OCO-designated funding is related to current operations in Afghanistan and Syria, but includes other activities that Congress and the President so-designate.

As enacted, H.R. 6157 provides $667.3 billion, a net reduction of $1.09 billion amounting to less than two-tenths of 1% of the total (i.e., base budget plus OCO) request. Compared with the total amount provided by the FY2018 defense appropriations bill (P.L. 114-113), the FY2019 act provides an increase of 2.3%. (See Table 1.)

Table 1. FY2019 Defense Appropriations Act (P.L. 115-245)

amounts in millions of dollars of discretionary budget authority

|

Bill Title |

Total FY2018 |

FY2019 |

House-passed |

Senate- passed |

Conference Report |

||||||||||

|

Title I - Military Personnel |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Title II - Operation and Maintenance |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Title III - Procurement |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Title IV – Research and Development |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Title V - Revolving and Management Funds |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Title VI - Defense Health Program and Other DOD |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Title VII - Related Agencies |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Title VIII - General Provisions (including offsetting rescissions of prior appropriations) |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Subtotal: Base Budget |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Title IX - Overseas Contingency Operation (OCO) |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Total Appropriation |

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: House Appropriations Committee, H. Rept.115-769, Report to accompany H.R. 6157, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2019; Senate Appropriations Committee, S. Rept. 115-290, Report to accompany S. 2159, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2019; H. Rept. 115-952, Conference Report to accompany H.R. 6157, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill.

Note: The regular FY2018 Defense Appropriations Bill, providing $647.4 billion in discretionary budget authority, was enacted as Division A of the FY2018 Omnibus Appropriations Bill (H.R. 1625/P.L. 115-141). Two bills enacted subsequently, provided additional DOD funds for FY2018: the Third Continuing Resolution for FY2018 (H.R. 1370/P.L. 115-96) provided $4.5 billion for missile defense and the repair of two Pacific Fleet destroyers damaged in collisions; the Fifth Continuing Resolution for FY2018 (H.R. 1892/P.L. 115-123) provided $434 million for recovery from hurricane damage. Discretionary funds provided to DOD by all three bills are included in the table's FY2018 column.

The House initially passed H.R. 6197 on June 28, 2018, by a vote of 359-49. On that same day, the Senate Appropriations Committee reported S. 3159, its own version of the FY2019 Defense Appropriations bill. Subsequently, the Senate adopted several amendments to H.R. 6157, including one that substituted the text of the Senate committee bill for the House-passed text. The Senate also adopted an amendment that added to the defense bill the text of S. 3158, the FY2019 appropriations bill for the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, which the Senate Appropriations Committee had approved on August 20, 2018. The Senate then passed H.R. 6197, as amended, on August 23, 2018, by a vote of 85-7.

A House-Senate conference committee reported a version of the bill on September 13, 2018. The Senate approved the conference report on September 18 by a vote of 93-7 and the House did likewise on September 26 by a vote of 361-61. President Donald J. Trump signed the bill into law (P.L. 115-245) on September 28, 2018. (See Table 2.)

Table 2. FY2019 Defense Appropriations Act (P.L. 115-245)

|

Subcomm. Markup |

House Report |

House Passage |

Senate Report |

Senate Passage |

Conference Report |

Public Law |

||

|

House |

Senate |

House |

Senate |

|||||

|

6/7/2018 |

6/26/2018 |

H. Rept. 115-769 |

6/28/2018 |

S. Rept. 115-290 |

8/23/2018 |

9/26/2018 |

9/18/2018 |

P.L. 115-245 |

Notes: The Senate Appropriations Committee reported its version of the FY2019 defense appropriations bill as S. 3159. Subsequently, the Senate substituted the language of that bill for the language of the House-passed version of H.R. 6157, which it further amended and then passed.

The total amount requested for DOD that falls within the scope of the annual defense appropriations bill and amounts provided in P.L. 115-245 as enacted are relatively close. Within those gross totals, however, there are differences between the amounts requested and the amounts provided for hundreds of specific elements within the sprawling DOD budget. Many of these individual differences reflect congressional judgements about particular issues. However, there also are patterns of differences that reflect congressional views on broad policy or budgetary questions:2

- Title I of the act, that funds Military Personnel accounts, provides $2.2 billion less than was requested for pay and benefits. House-Senate conferees said the reduction should have no adverse impact on the force. According to the conference report, revised estimates of the budgetary impact of recent changes in the military retirement system were the basis for a net reduction from the request of $1.54 billion. Other reductions totaling $430 million were justified by conferees on the basis of "historical unobligated balances," that is, an accumulation of funds in certain accounts that were appropriated in prior years but were not spent.

- Base budget funding provided by the Operation and Maintenance (O&M) title of the act (Title II) amounts to a net reduction of $5.2 billion from the request.3 In part, the apparent cut reflects a transfer of nearly $2.0 billion to Title IX of the act, which funds OCO. The conferees justified additional reductions totaling $1.34 billion on the basis of either large unobligated balances or "historical underexecution," (i.e., a pattern of repeatedly spending less on military personnel in a given fiscal year than had been appropriated).

On the other hand, total procurement funding for the base budget (Title III) is $4.8 billion higher than the request. While the act makes hundreds of additions and cuts to the funding requested for particular items, three broad themes all push the act's procurement total upward: $2.48 billion is added to buy aircraft and other equipment for National Guard and reserve forces; $2.31 billion is added to fully fund or acquire major components for additional six ships (see Table 9); and $2.13 billion is added to the $8.49 billion requested for procurement of F-35 Joint Strike Fighters (see Table 10).

Similarly, base budget funding in the act for research and development (Title IV) is $3.8 billion higher than the request, partly because the legislation would add $2.3 billion to the $13.7 billion requested for science and technology (S&T) programs – that is, the part of the R&D effort focused on developing new and potentially useful scientific and engineering knowledge rather than on designing specific pieces of equipment intended for production.

Strategic Context

The Trump Administration presented its FY2019 defense budget request – nearly 96% of which is funded by the annual defense appropriations bill – as responding to an international security environment that has become increasingly contentious in recent years. Many observers view events such as China's construction of military bases in the South China Sea since 2013 and Russia's seizure of Crimea in March 2014 as marking an end to the post-Cold War era that began in the late 1980s and 1990s with the decline and collapse of the Soviet Union.

Many observers of contemporary international security trends contend that the United States and its allies are entering an era of increased strategic complexity. Very broadly speaking, during the Cold War and beyond, U.S. national security challenges were difficult, yet relatively straightforward to conceptualize, prioritize, and manage. U.S. national security and foreign policies during the Cold War were focused on its strategic competition with the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and on containing the spread of communism globally. In the years following the end of the Cold War, U.S. national security policies and practices were largely designed to curtail genocide in the Balkans and Iraq, while simultaneously containing regional aggressors such as Iran and North Korea and recalibrating relations with China and Russia.

The terrorist attacks on U.S. territory on September 11th, 2001 ushered in an era of national security policy largely focused on countering terrorism and insurgencies in the Middle East while containing, if not reversing, North Korean and Iranian nuclear weapons programs. As a legacy of the Cold War's ending, U.S. and allied military forces had overwhelming military superiority over adversaries in the Middle East and the Balkans. Accordingly, operations were conducted in relatively permissive environments.

The 2014 Russian invasion of the Crimean peninsula and subsequent proxy war in eastern Ukraine fostered concern in the United States and in Europe about an aggressive and revanchist Russia. Meanwhile, China began building and militarizing islands in the South China Sea in order to lay claim to key shipping lanes. Together, these events highlighted anew the salience in the U.S. national security agenda of dealing with other great powers, that is, states able and willing to employ military force unilaterally to accomplish their objectives. At the same time, the security challenges that surfaced at the end of the Cold War – fragile states, genocide, terrorism, and nuclear proliferation, to name a few – have remained serious threats to U.S. interests. In this international context, conceptualizing, prioritizing, and managing these myriad problems, arguably, is more difficult than it was in eras past. The situation is summarized by the December 2017 U.S. National Security Strategy (NSS), which notes:

The United States faces an extraordinarily dangerous world, filled with a wide range of threats that have intensified in recent years.4

Likewise, the January 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS) argues:

We are facing increased global disorder, characterized by decline in the long-standing rules-based international order—creating a security environment more complex and volatile than any we have experienced in recent memory.5

The Trump Administration's 2017 NSS and the 11-page unclassified summary of the NDS explicitly reorients U.S. national security strategy (including defense strategy) toward a primary focus on great power competition with China and Russia and on countering Chinese and Russian military capabilities.

In addition to explicitly making the great power competition the primary U.S. national security concern, the NDS also argues for a focus on bolstering the competitive advantage of U.S. forces, which, the document contends, has eroded in recent decades vis-à-vis the Chinese and Russian threats. The NDS also maintains that, contrary to what was the case for most of the years since the end of the Cold War, U.S. forces now must assume that their ability to approach military objectives will be vigorously contested.

The new U.S. strategy orientation set forth in the 2017 NSS and 2018 NDS is sometimes referred to a "2+3" strategy, meaning a strategy for countering two primary challenges (China and Russia) and three additional challenges (North Korea, Iran, and terrorist groups), although given the radically differing nature of these challenges, one might posit that such a heuristic oversimplifies the contours of the strategic environment.

|

2018 National Defense Strategy: Focus on 'High-End' Combat Capability For additional background on the National Defense Strategy, see CRS Report R45349, The 2018 National Defense Strategy: Fact Sheet, by Kathleen J. McInnis. For further background and analysis on the increased DOD focus on great power military competition, see CRS Report R43838, A Shift in the International Security Environment: Potential Implications for Defense—Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke, and CRS Report R44891, U.S. Role in the World: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke and Michael Moodie. |

Budgetary Context

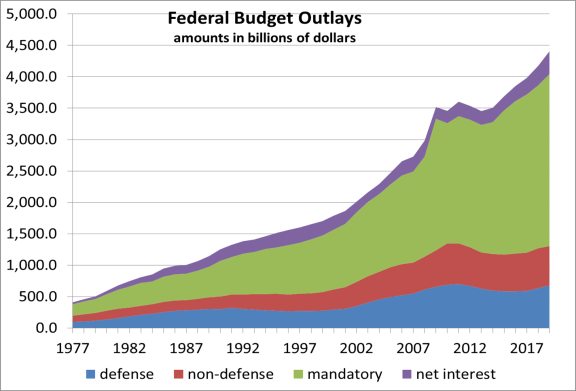

Congressional action on all FY2019 appropriations bills was shaped by an effort to rein in federal spending, out of concern for the increasing indebtedness of the federal government. The fastest growing segment of federal spending in recent decades has been mandatory spending for entitlement programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. (See Figure 1.)

|

Figure 1. Federal Budget Outlays amounts in billions of dollars |

|

|

Source: Office of Management and Budget, Historical Tables, Table 8-1 "Outlays by Budget Enforcement Act Category, 1962-2023." |

The Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011 (P.L. 112-25) was intended to reduce spending by $2.1 trillion over the period FY2012-FY2021, compared to projected spending over that period. One element of the act established binding annual limits (or caps) to reduce discretionary federal spending through FY2021 by $1.0 trillion. Separate annual caps on discretionary appropriations for defense-related activities and non-defense activities are enforced by a mechanism called sequestration. Sequestration provides for the automatic cancellation of previous appropriations, to reduce discretionary spending to the BCA cap for the year in question.

The caps on defense-related spending apply to discretionary funding for DOD and for defense-related activities by other agencies, comprising the national defense budget function which is designated budget function 050. The caps do not apply to funding designated by Congress and the president as emergency spending or spending on OCO.

|

The Budget Control Act For additional information on the BCA and its impact on the defense budget see CRS Report R44039, The Defense Budget and the Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions, by Brendan W. McGarry , CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions, by Megan S. Lynch, and CRS In Focus IF10657, Budgetary Effects of the BCA as Amended: The "Parity Principle", by Grant A. Driessen. |

Congress has raised the annual spending caps repeatedly, most recently with the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123), which set the national defense funding cap for FY2019 at $647 billion. Because the cap applies to defense-related spending in other agencies as well as to DOD, and because the annual defense appropriations bill covers most but not all of DOD's discretionary budget, the portion of the cap applicable to FY2019 defense appropriations bill is approximately $600 billion. The Administration's request for the bill was consistent with that cap, as is the enacted bill.

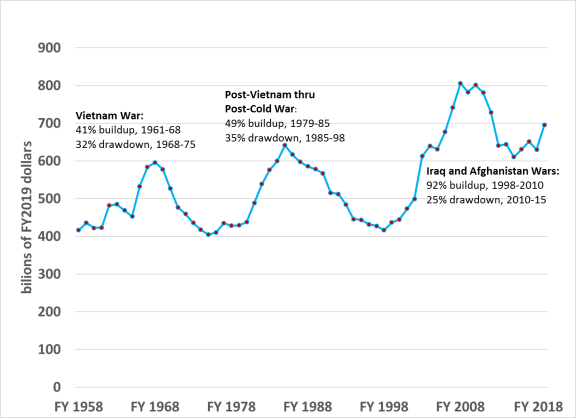

The total FY2019 DOD request – including both base budget and OCO funding – continued an upswing that began with the FY2016 budget, which marked the end of a relatively steady decline in real (that is, inflation-adjusted) DOD purchasing power. Measured in constant dollars, DOD funding peaked in FY2010, after which the drawdown of U.S. troops in OCO operations drove a reduction in DOD spending. (See Figure 2.)

Appropriations Overview

Military Personnel

- The law funds the Administration's proposal to increase the size of the armed forces by 15,600 personnel in the active components – with nearly half of that increase destined for the Navy – and by a total of 800 members of the Air Force Reserve and Air National Guard. The Senate-passed version of the bill would have funded less than half the amount of the proposed increase in active-duty personnel and none of the amount of the proposed increase in the reserve component. (See Table 3.)

The Senate Appropriations Committee report on S. 3159 (which became the basis for the Senate-passed version of the appropriations bill) stated no reason for recommending less than half the amount of the Administration's proposed increase. However, on this point, the Senate version of the appropriations bill mirrored the Senate-passed version of the companion John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2019 (H.R. 5515; P.L. 115-232), which also would have approved half the amount of the proposed increase in the active-duty components and none of the amount of the proposed reserve component increase. In the Senate Armed Services Committee report to accompany its version of the NDAA, the panel expressed concern that, because unemployment is at historically low levels, the services might have trouble recruiting enough additional personnel to fill a larger force while maintaining their current standards for enlistment.

- As with the FY2019 defense appropriations bill, the conference report on the FY2019 NDAA authorized the Administration's proposed increase in military end-strength.

Table 3. FY2019 Military Personnel (End-Strength) Supported by

FY2019 Defense Appropriations Act (P.L. 115-245)

|

FY2018 |

FY2019 budget request |

House-passed |

Senate-passed |

P.L. 115-245 |

|||||

|

Active Components |

|||||||||

|

Army |

483,500 |

487,500 |

487,500 |

485,741 |

487,500 |

||||

|

Navy |

327,900 |

335,400 |

335,400 |

331,900 |

335,400 |

||||

|

Marine Corps |

186,000 |

186,100 |

186,100 |

186,100 |

186,100 |

||||

|

Air Force |

325,100 |

329,100 |

329,100 |

325,720 |

329,100 |

||||

|

Subtotal: Active Components |

1,322,500 |

1,338,100 |

1,338,100 |

1,329,461 |

1,338,100 |

||||

|

Reserve Components |

|||||||||

|

Army Reserve |

199,500 |

199,500 |

199,500 |

199,500 |

199,500 |

||||

|

Army National Guard |

343,500 |

343,500 |

343,500 |

343,500 |

343,500 |

||||

|

Navy Reserve |

59,000 |

59,100 |

59,100 |

59,000 |

59,100 |

||||

|

Marine Corps Reserve |

38,500 |

38,500 |

38,500 |

38,500 |

38,500 |

||||

|

Air Force Reserve |

69,800 |

70,000 |

70,000 |

69,800 |

70,000 |

||||

|

Air National Guard |

106,600 |

107,100 |

107,100 |

106,600 |

107,100 |

||||

|

Subtotal: Reserve Components |

816,900 |

817,700 |

817,700 |

816,900 |

817,700 |

||||

Sources: House Appropriations Committee, H. Rept.115-769, Report to accompany H.R. 6157, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2019; Senate Appropriations Committee, S. Rept. 115-290, Report to accompany S. 2159, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2019; H. Rept. 115-952, Conference Report to accompany H.R. 6157, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill.

- The enacted version of the appropriations bill funds the Administration's recommended 2.6 % increase in military basic pay effective January 1, 2019 (as both the House and Senate versions would have done). The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates the cost of this raise to be $1.8 billion.6

|

FY2019 Military Personnel Policy Issues For information and analysis concerning military policy issues treated in the companion FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 5515), see CRS Report R45343, FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act: Selected Military Personnel Issues, by Bryce H. P. Mendez et al. |

Defense Health Program

In terms of total funding, the act appropriates $34.0 billion for the Defense Health Program (DHP) in FY2019, which represents an increase of less than 1% over the Administration's $33.7 billion request.7 As usual, those similar totals mask a number of differences. Compared with the request, the enacted bill cuts:

- $213 million to force DOD to deal with what House and Senate conferees labelled "excess growth" in the cost of pharmaceuticals;

- $215 million in anticipation that the funds will not be needed because the program will continue to exhibit its pattern of historical underexecution; and

- $597 million to correct what the House Appropriations Committee said was erroneous accounting for congressional action on the FY2018 DHP budget.

Among the amounts the enacted bill would add to the request are:

- $10 million for training therapeutic service dogs; and

- $2 million to coordinate the actions of DOD and the Department of Veterans Affairs to study the possible adverse health effects of the widespread use of open burning pits to dispose of trash at U.S. military sites in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The Senate-passed version of the bill would have added to the request $750 million for maintenance and repair of DHP facilities, but this was not included in the final version of the bill.

Congressionally-Directed Medical R&D

Continuing a 28-year-long pattern, the act adds to the Administration's DHP budget request funds for medical research and development. Beginning with a $25 million earmark for breast cancer research in the FY1992 defense appropriations act (P.L. 102-172), Congress has added a total of $13.2 billion to the DOD budget through FY2018 for research on a variety of medical conditions and treatments.

The Administration's DHP budget request included $710.6 million for research and development.8 The House-passed version of H.R. 6157 would have added $775.6 million, most of which was allocated to one of 27 specific medical conditions or treatments. The Senate version would have added to the request $963.2 of which $431.5 million was allocated among 10 specific diseases or treatments.9 The enacted version of the bill appropriates a total of $2.18 billion for DHP-funded medical research, an increase of $1.47 billion over the request that covers each of the particular medical conditions and treatments that would have been funded by either chamber's bill.

As has been typical for several years, the largest amounts for particular diseases in both the House and Senate versions of the FY2019 bill are aimed at breast cancer, prostate cancer, and traumatic brain injury (TBI). (See Table 4.)

|

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

FY2019 |

Final |

|

|

Breast Cancer |

130 |

130 |

120 |

130 |

|

Prostate Cancer |

100 |

100 |

64 |

100 |

|

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) and Psychological Health |

125 |

125 |

60 |

125 |

Sources: House Appropriations Committee, H.Rept. 115-769, Report to accompany H.R. 6157, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2019; Senate Appropriations Committee, S.Rept. 115-290, Report to accompany S. 2159, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2019; H.Rept. 115-952, Conference Report to accompany H.R. 6157, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill.

|

Congressionally Directed Medical Research For additional information on the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program, see CRS In Focus IF10349, Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs Funding for FY2019, by Bryce H. P. Mendez and CRS Report R45399, Military Medical Care: Frequently Asked Questions, by Bryce H. P. Mendez. |

Operation and Maintenance (O&M) Funds

The act cuts $4.8 billion from the Administration's $199.5 billion request for base budget O&M funds, making the final appropriation $194.7 billion.10 However, more than one-third of the apparent reduction ($2.0 billion) is accounted for by funds that the bill appropriates as part of the budget for OCO, despite their having been requested in the base budget.

For dozens of additional cuts from the base budget O&M request, House-Senate conferees cited rationales that imply that the reductions need not have an adverse impact on DOD activities:

- Cuts totaling $1.3 billion were justified by the assumption that particular programs would underspend their budget requests by that amount, often on the basis of what the conferees called a pattern of historical underexecution of their annual appropriations;

- Cuts totaling $1.3 billion were justified on grounds that DOD had not justified its request for those funds; and

- Cuts totaling $343 million were justified on grounds that the requests amounted to unrealistically large increases over the prior year's appropriation.

House-backed 'Readiness' Increases

The House-passed version of the bill would have added a total of $1.0 billion spread across the active and reserve components of the armed forces to "restore readiness." According to the House committee report, the funds were intended to be spent on training, depot maintenance, and base operations according to a plan DOD was to submit to Congress 30 days in advance of expenditure. The funds were not included in the enacted version of the bill.

Selected Acquisition Programs

Strategic and Long-Range Strike Systems

The Administration's FY2019 budget request continued the across-the-board modernization of the U.S. strategic arsenal that had been launched by the Obama Administration.11 Within that program, the initial House and Senate versions of H.R. 6157 funded the major initiatives with some changes, many of which reflected routine budget oversight. (See Table 5.)

|

Strategic Arms Modernization Program For background and additional analysis, see CRS Report RL33640, U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces: Background, Developments, and Issues, by Amy F. Woolf. |

The enacted version of the bill adds a total of more than $300 million to the amounts requested to develop three new long-range weapons. Specifically it adds:

- $69.4 million to the $345.0 million requested for a new, nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) to replace Minuteman III missiles deployed in the 1970s, an increase conferees said would meet an unspecified "unfunded requirement";

- $203.5 million for "program acceleration" to the $263.4 million requested to develop Conventional Prompt Global Strike weapon sufficiently accurate to strike a target at great range with a conventional (i.e., non-nuclear) warhead; and

- $50 million, also to meet an unspecified "unfunded requirement," to the $614.9 million requested to develop a Long-Range Stand-Off (LRSO) weapon to replace the nuclear-armed air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) carried by long-range bombers.

|

System |

FY2019 budget requested |

House-passed H.R. 6157 |

Senate- passed |

Conference report |

|

|

Upgrades to Existing Bombers (B-2, B-1, B-52) |

Proc. |

221.1 |

218.2 |

214.1 |

217.2 |

|

R&D |

723.8 |

710.5 |

759.7 |

710.4 |

|

|

Columbia-class Ballistic Missile Submarine |

Proc. |

3,005.3 |

2,949.4 |

3,242.3 |

3,173.4 |

|

R&D |

704.9 |

686.7 |

732.9 |

732.9 |

|

|

D-5 Trident II Missile Mods |

Proc. |

1,078.8 |

1,044.8 |

1,078.8 |

1,056.8 |

|

R&D |

157.7 |

145.7 |

167.9 |

148.4 |

|

|

B-21 Bomber |

R&D |

2,314.2 |

2,314.2 |

2,276.5 |

2,279.2 |

|

Long-Range Stand-off Weapon |

R&D |

614.9 |

699.9 |

624.9 |

664.9 |

|

Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent [new ICBM] |

R&D |

345.0 |

441.4 |

345.0 |

414.4 |

|

Conventional Prompt Global Strike |

R&D |

263.4 |

273.4 |

615.9 |

466.9 |

Sources: House Appropriations Committee, H. Rept. 115-769, Report to accompany H.R. 6157, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2019; Senate Appropriations Committee, S.Rept. 115-290, Report to accompany S. 2159, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2019; H.Rept. 115-952, Conference Report to accompany H.R. 6157, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill.

Note: Full citations of CRS products are listed in the Appendix.

|

Low-Yield Nuclear Warhead One of the Trump Administration's more controversial initiatives – the deployment of a nuclear warhead with a relatively low explosive yield on some Trident submarine-launched missiles – is funded mostly by the Department of Energy, which develops and manufactures nuclear bombs and missile warheads. The $65 million requested for this program was provided by P.L. 115-244, the FY2019 Energy and Water Development, Legislative Branch and Military Construction and Department of Veterans Affairs Consolidated Appropriation Act The defense appropriations bill includes relatively small (and unspecified) amounts to lay the groundwork for mounting these warheads on existing missiles, when they become available. However, in its report to accompany the defense bill, the Senate Appropriations Committee insisted that no funds provided by the defense bill be used to deploy the new warhead (designated the W 76 Mod 2) until DOD had submitted a report discussing several issues associated with the project, including the risk that an adversary could misinterpret the launch of a missile carrying a single, low-yield warhead with the launch of a Trident carrying up to a dozen more powerful nuclear warheads. |

Ballistic Missile Defense Systems

The act supports the general thrust of the administration's funding request for ballistic missile defense, with the sort of funding adjustments that are routine in the appropriations process.

For so-called mid-course defense, intended to protect U.S. territory against a relatively small number of intercontinental-range warheads, the Administration's program would expand the fleet of interceptor missiles currently deployed in Alaska and California, while developing an improved version of that interceptor. The program also is deploying shorter-range THAAD, Aegis, and Patriot missiles to provide a so-called terminal defense intended to protect U.S. allies and forces stationed abroad and to provide a second-layer of protection for U.S. targets. (See Table 6.)

|

U.S. Ballistic Missile Defense Program For an overview of U.S. ballistic missile defenses, see CRS In Focus IF10541, Defense Primer: Ballistic Missile Defense. |

Accounting for a FY2018 Windfall

The act cuts a total $301.7 million from the amounts requested for various projects associated with mid-course defense of U.S. territory on grounds that these funds were intended for purposes Congress already had funded in the FY2018 defense appropriations act (P.L. 115-141). That measure was enacted two months after the FY2019 budget request was sent to Congress, reiterating the request for the funds in question.

Missile Defense in South Korea

The act adds more than $400 million to the amounts requested to develop and acquire missile defenses for South Korea and U.S. forces stationed there. North Korea has tested long-range and short-range ballistic missiles as well as nuclear weapon.12 The increase includes $284.4 million to develop a network linking THAAD interceptor missiles and shorter-range Patriot missiles based in South Korea and Japan with sensors that could track incoming North Korean missiles.

The act also adds $140 million to the $874 million requested to procure THAAD interceptors that are deployed in Guam, in the Middle East, and in South Korea.

|

System |

FY2019 budget requested |

House-passed H.R. 6157 |

Senate-passed |

Conference Report |

|

|

Mid-Course Ballistic Missile Defense (including test) |

proc. |

524.0 |

508.0 |

565.0 |

532.6 |

|

r&d |

1,008.2 |

$917.0 |

876.0 |

876.0 |

|

|

Improved Mid-Course Ballistic Missile Defense (incl. radars and warhead) |

r&d |

1,019.6 |

753.4 |

765.8 |

729.8 |

|

Aegis and Aegis Ashore |

proc. |

820.8 |

791.7 |

840.8 |

812.5 |

|

r&d |

891.0 |

849.5 |

897.0 |

864.5 |

|

|

Terminal Ballistic Missile Defense (THAAD, Patriot/PAC-3 and Patriot Mods) |

proc. |

2,368.6 |

2,378.6 |

2,508.6 |

2,518 |

|

r&d |

340.6 |

514.7 |

534.7 |

524.7 |

|

|

Israeli Cooperative Missile Defense Programs (incl. David's Sling) |

proc. |

130.0 |

130.0 |

130.0 |

130.0 |

|

r&d |

300.0 |

300.0 |

300.0 |

300.0 |

|

|

Iron Dome |

proc. |

70.0 |

70.0 |

70.0 |

70.0 |

Sources: House Appropriations Committee, H. Rept.115-769, Report to accompany H.R. 6157, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2019; Senate Appropriations Committee, S. Rept. 115-290, Report to accompany S. 2159, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2019; H. Rept. 115-952, Conference Report to accompany H.R. 6157, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill.

Note: Full citations of CRS products are listed in the Appendix.

Military Space Programs

While Congress and the Administration weighed alternative ways to organize a new organization – a Space Force13 – to address long-standing criticisms of DOD's acquisition of space satellites and associated launchers, the debate was not cited by the House and Senate Appropriations Committees in their reports on the FY2019 defense appropriations bill. Nor was it cited by House and Senate conferees in their Joint Explanatory Statement to accompany the conference report on the bill. The enacted bill funded – with largely modest changes – the Administration's requests for several major defense-related space programs. (See Table 7.)

The most sizeable departure from the Administration's request was the addition of $200 million to the $245.4 million requested in R&D funding associated with the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV), which is the program for acquiring satellite launch rockets and launch services for relatively heavy DOD space payloads.

|

System |

FY2019 budget requested |

House-passed H.R. 6157 |

Senate |

Conference Report |

|

|

Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) |

proc. |

1,704.5 |

1,704.5 |

1,445.6 |

1,514.5 |

|

r&d |

245.4 |

245.4 |

445.4 |

445.4 |

|

|

Space-Based Infra-Red System, High (SBIRS High) |

proc. |

138.4 |

108.4 |

138.4 |

108.4 |

|

r&d |

60.6 |

60.6 |

60.6 |

60.6 |

|

|

Evolved SBIRS/Overhead Persistent Infra-Red (OPIR) |

r&d |

643.1 |

633.1 |

743.1 |

643.1 |

|

Global Positioning System (GPS III) |

proc. |

71.5 |

71.5 |

71.5 |

71.5 |

|

r&d |

1,405.2 |

1,387.2 |

1,325.2 |

1,325.2 |

|

Sources: House Appropriations Committee, H. Rept.115-769, Report to accompany H.R. 6157, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2019; Senate Appropriations Committee, S. Rept. 115-290, Report to accompany S. 2159, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2019; H. Rept. 115-952, Conference Report to accompany H.R. 6157, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill.

Note: Full citations of CRS products are listed in the Appendix.

Ground Combat Systems

The act supports the general thrust of the Administration's program to beef up the capacity of Army and Marine Corps units to prevail in full-scale, high-tech combat with the forces of near-peer adversaries, namely Russia and China. The increased DOD emphasis on conventional combat with major powers is rooted in the 2018 National Defense Strategy of which DOD published an unclassified synopsis on January 19, 2018.14

In addition to modernizing the ground forces' existing capabilities, the Administration's FY2019 budget request included stepped-up investments to improve two capabilities the Army identifies as among its top modernization priorities: mobile defenses against cruise missiles and drone aircraft; and improved firepower and mobility for infantry units. While taking some reductions from the amounts requested for some programs – cuts based on program delays, the availability of prior-year funds, and so forth – the bills would provide funding above the requested level to accelerate other programs. (See Table 8.)

|

For background and analysis on recent Army planning, see CRS Insight IN10889, Army Futures Command (AFC), by Andrew Feickert. |

Existing Capabilities15

The act funded most of the roughly $2.5 billion requested to continue upgrading the Army's fleet of M-1 tanks, built between 1980 and 1996. For the program to continue modernizing the service's Bradley armored troop carriers – which is roughly contemporary with the tank fleet – it would cut nearly a quarter of the $1.04 billion requested, mostly on grounds of a "change of acquisition strategy."

The act provided more funds than requested in order to accelerate modernization of two other components of the Army's current combat vehicle fleet, adding:

- $110.0 million to the $310.8 million requested to replace the chassis and powertrain of the M-109 Paladin self-propelled with the more powerful and robust chassis of the Bradley troop carrier; and

- $94.0 million to the $265.3 million requested to replace the flat underside of many types of Stryker wheeled combat vehicles with a V-shaped bottom intended to more effectively deflect the explosive force of buried landmines.

The act generally funded programs to replace two older types of tracked vehicles, providing:

- $447.5 million (of $479.8 million requested) to continue procurement of the Advanced Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV), intended to replace the Vietnam War-vintage M-113 tracked personnel carrier; and

- $167.5 million, as requested, for procurement of the Amphibious Combat Vehicle (ACV), a successor to the Marine Corps' equally dated AAV-7 amphibious troop carrier.

Infantry Firepower and Mobility

The Administration requested a total of $449 million to develop and begin purchasing vehicles intended to boost the lethality and mobility of Army infantry units – that is, forces not equipped with M-1 tanks and other armored vehicles. Nearly 90% of those funds were for development of a relatively light-weight tank (designated Mobile Protected Firepower or MPF) with the balance of the money intended to begin purchasing four-wheel-drive, off-road vehicles for reconnaissance missions and troop transport, designated Light Reconnaissance Vehicle (LRV) and Ground Mobility Vehicle (GMV), respectively.

The act funds the three programs with some relatively small reduction reflecting concerns that their development or testing schedules are unrealistically ambitious.

Anti-Aircraft Defense

The FY2019 budget request includes nearly $450 million for programs intended to beef up mobile Army defenses against aircraft, including unmanned aerial systems and cruise missiles. These include a Stryker combat vehicle equipped to launch Stinger missiles (designated IM-SHORAD) and a larger, truck-mounted missile launcher (designated IFPC).

The act cut the total R&D request for the programs by nearly 25% for various, relatively typical rationales including development program delays.

|

System |

FY2019 budget request |

House-passed |

Senate- passed |

Conference Report |

|

|

M-1 Abrams tank (mods and upgrades) |

Proc. |

2,492.5 |

2,492.5 |

2,486.2 |

2,486.2 |

|

R&D |

164.8 |

149.8 |

165.8 |

165.8 |

|

|

M-2 Bradley Fighting Vehicle (new and mods) |

Proc. |

880.4 |

811.8 |

720.4 |

720.4 |

|

R&D |

167.0 |

154.8 |

87.0 |

87.0 |

|

|

Paladin Self-propelled artillery |

Proc. |

418.8 |

569.6 |

525.9 |

525.9 |

|

R&D |

40.7 |

37.2 |

30.7 |

37.2 |

|

|

Stryker Combat Vehicle (new and mods) |

Proc. |

309.4 |

358.5 |

392.6 |

392.6 |

|

R&D |

58.9 |

49.2 |

45.4 |

45.4 |

|

|

Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV) |

Proc. |

710.2 |

674.0 |

709.0 |

672.8 |

|

R&D |

118.2 |

112.0 |

118.2 |

112.0 |

|

|

Amphibious Combat Vehicle |

Proc. |

167.5 |

159.6 |

167.5 |

167.5 |

|

R&D |

98.2 |

76.1 |

48.9 |

66.1 |

|

|

Infantry Firepower and Mobility Programs (MPF, GMV, and LRV) |

Proc. |

47.0 |

43.0 |

47.0 |

42.7 |

|

R&D |

401.8 |

325.9 |

394.9 |

375.1 |

|

|

Air Defense Programs (IM-SHORAD and IFPC) |

Proc. R&D |

176.9 326.8 |

141.9 268.7 |

173.2 275.8 |

176.9 252.6 |

Sources: House Appropriations Committee, H. Rept.115-769, Report to accompany H.R. 6157, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2019; Senate Appropriations Committee, S. Rept. 115-290, Report to accompany S. 2159, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2019; H. Rept. 115-952, Conference Report to accompany H.R. 6157, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill.

Note: Full citations of CRS products are listed in the Appendix.

National Guard and Reserve Force Equipment

Following what has long been the usual practice, the act adds to the DOD budget $2.35 billion for procurement of aircraft, ground vehicles, and other equipment for National Guard or other reserve component units. These funds are provided in addition to the $3.64 billion worth of equipment for Guard and reserve forces that was included in the Administration's FY2019 budget request.

The increase includes a total of $1.30 billion in the National Guard and Reserve Equipment Account (NGREA) which is allocated among the six reserve force components: the Army and Air National Guard, and the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force Reserve. In their Joint Explanatory Statement on the final version of the bill, House and Senate conferees directed the funds to be used "for priority equipment that may be used for combat and domestic response missions."

Amounts are not earmarked for specific purchases, but conferees on the defense bill directed that "priority consideration" in using the funds be given to 18 types of items. The 18 categories range in specificity from "digital radar warning receivers for F-16s" to "cold-weather and mountaineering gear and equipment."

Other congressional initiatives include specific increases for National Guard equipment:

- $640 million for 8 C-130J cargo planes;

- $168 million for 6 AH-64E attack helicopters;

- $156 million for 8 UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters; and

- $100 million for HMMWV ("Hum-vee") vehicles.

Naval Systems

The act funds the major elements of the Administration's shipbuilding program, which aims at enlarging and modernizing the Navy's fleet. The stated goals of the program are to improve the Navy's ability to respond to increasingly assertive military operations by China in the Western Pacific and Indian Oceans, and to halt, if not reverse, the decline in the technological edge that U.S. forces have enjoyed for decades. (See Table 9.)

|

Shipbuilding Plans For additional background and analysis, see CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke, esp. Appendix A, "Strategic and Budgetary Context". |

Carrier 'Block Buy'

The Administration's $1.60 billion request to fund a Ford-class aircraft carrier was intended as the fourth of eight annual increments to cover the estimated $12.6 billion cost of what will be the third ship of the Ford class. That ship, designated CVN-80 and named Enterprise, is slated for delivery to the Navy at the end of FY2027.

The act, which provides nearly the total amount requested,16 includes a provision that allows the Navy – under certain conditions – to use the funds for a block buy contract that would fund procurement of components for both CVN-80 and the planned fourth ship of the Ford class, designated CVN-81. Proponents of such an arrangement contend that it could accelerate the delivery of the fourth ship and reduce the overall cost of the two vessels.17 Before the funds could be used for a block buy, DOD would have to certify to Congress an analysis demonstrating that the approach would save money, as required by Section 121 of the companion FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act, H.R. 5515 (P.L. 115-232).

Amphibious Landing Ships

The act adds to the Administration's request $1.1 billion to accelerate the planned production of ships to support amphibious landings and large air-cushion craft to haul tanks and other combat equipment ashore. This total includes:

- $350 million to begin construction of an LHA-class helicopter carrier;

- $350 million to begin construction of either an LPD-17-class amphibious landing transport or a variant of that ship designated LX(R);

- $225 million for an Expeditionary Fast Transport, a catamaran that can carry a few hundred troops and their gear hundreds of miles at 40 mph; and

- $182.5 million to buy eight air-cushion landing craft (instead of the five requested) to haul tanks and other equipment ashore from transport ships.

|

System |

FY2019 budget requested |

House-passed |

Senate-passed |

Conference Report |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Ford-class Aircraft Carrier |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1,573.2 |

||||||||||

|

Mid-life Refueling and Overhaul for |

|

|

|

|

|

|

425.9 |

||||||||||

|

Virginia-class attack submarine |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

7,137.1 |

|||||||||

|

DDG 51-class Aegis destroyer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

5,891.8 |

|||||||||

|

Mods to existing Aegis cruisers and destroyers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

731.4 |

||||||||||

|

Littoral Combat Ship |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

1,571.2 |

|||||||||

|

T-AO 125-class refueling oiler |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

1,052.1 |

|||||||||

|

LHA-class Amphibious Assault Ship |

|

|

|

|

|

|

350.0 |

||||||||||

|

LPD 17-class or LX(R)-class Amphibious Landing Ship |

|

|

|

|

|

|

350.0 |

||||||||||

|

Expeditionary Fast Transport |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

225.0 |

|||||||||

|

Expeditionary Seabase Ship |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

647.0 |

|||||||||

|

Ship-to-Shore Connector |

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

507.9 |

|||||||||

|

Cable Ship |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.0 |

||||||||||

Sources: House Appropriations Committee, H. Rept.115-769, Report to accompany H.R. 6157, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2019; Senate Appropriations Committee, S. Rept. 115-290, Report to accompany S. 2159, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2019; H. Rept. 115-952, Conference Report to accompany H.R. 6157, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill.

Note: Full citations of CRS products are listed in the Appendix.

Aviation Systems

Generally speaking, the act funds the Administration's requests for military aircraft acquisition, subject to relatively minor cuts reflecting routine congressional oversight. The major departures from the request were increased funds to accelerate production of the F-35 Joint Strike fighter and the addition of funds to buy helicopters and C-130 cargo planes for the National Guard.

|

U.S. Military Aviation For additional background, see CRS In Focus IF10546, Defense Primer: United States Airpower, by Jeremiah Gertler |

F-35 Joint Strike Fighter

The act's largest addition to the Administration's request for a single weapons program is the addition of $1.70 billion to acquire 16 F-35 Joint Strike Fighters to the 77 F-35s funded in the budget request.18 The additional funds provides eight more aircraft in addition to the 48 requested for the Air Force, two more of the short-takeoff, vertical-landing (STOVL) F-35s for the Marine Corps (in addition to the 20 requested), and six more of the aircraft carrier-adapted version – four for the Navy (in addition to the nine requested), and two for the Marine Corps.

Other notable funding increases in the bill for procurement of combat aircraft include:

- $65.0 million to extend the life of A-10 ground-attack planes by replacing their wings; and

- $100.0 million to begin acquisition of a relatively low-tech (and relatively inexpensive) ground-attack plane designated OA-X for use against other-than-top-tier adversaries.

|

System |

FY2019 budget requested |

House-passed H.R. 6157 |

Senate-passed |

Conference report |

||||||||

|

# |

Amt. |

# |

Amt. |

# |

Amt. |

# |

Amt. |

|||||

|

Fighter and Ground-Attack Aircraft |

||||||||||||

|

F/A-18 |

Proc. |

24 |

1,996.4 |

24 |

1935.3 |

24 |

1,911.8 |

24 |

1,923.3 |

|||

|

F/A-18 mods |

Proc. |

1,213.5 |

1,184.8 |

1,125.6 |

1,159.7 |

|||||||

|

R&D |

301.8 |

256.2 |

311.6 |

313.1 |

||||||||

|

F-35 (all variants) and mods |

Proc. |

77 |

8,798.5 |

93 |

10,522.7 |

89 |

9,614.2 |

93 |

10,412.7 |

|||

|

R&D |

1,262.0 |

1,262.0 |

1,023.3 |

|||||||||

|

F-22 mods |

Proc. |

259.7 |

262.7 |

259.7 |

262.7 |

|||||||

|

R&D |

603.6 |

603.6 |

588.5 |

588.5 |

||||||||

|

F-15 mods |

Proc. |

695.8 |

746.5 |

613.6 |

671.5 |

|||||||

|

R&D |

330.0 |

330.2 |

313.6 |

340.3 |

||||||||

|

F-16 mods |

Proc. |

324.3 |

232.4 |

304.3 |

303.4 |

|||||||

|

R&D |

191.6 |

191.6 |

185.9 |

185.9 |

||||||||

|

A-10 mods |

Proc. |

109.1 |

174.1 |

109.1 |

157.7 |

|||||||

|

R&D |

26.7 |

26.7 |

26.7 |

26.7 |

||||||||

|

OA-X light attack plane |

Proc. |

0.0 |

40.0 |

300.0 |

100.0 |

|||||||

|

Unmanned Aerial Systems |

||||||||||||

|

RQ-4 Global Hawk [long-range reconnaissance] |

Proc. |

3 |

699.3 |

3 |

642,6 |

3 |

799.3 |

3 |

774.5 |

|||

|

R&D |

507.5 |

502.3 |

507.5 |

507.5 |

||||||||

|

MQ-9 Reaper [reconnaissance and ground-attack] |

Proc. |

29 |

561.4 |

24 |

487.4 |

35 |

595.6 |

24 |

411.6 |

|||

|

R&D |

115.3 |

94.3 |

115.3 |

104.3 |

||||||||

|

MQ-25 Stingray [carrier-based aerial refueling and reconnaissance] |

R&D |

718.9 |

451.4 |

668.9 |

518.9 |

|||||||

|

Combat Support and Transport Aircraft |

||||||||||||

|

KC-46 tanker |

Proc. |

15 |

2,559.9 |

15 |

2,293.6 |

15 |

2,415.5 |

15 |

2,290.9 |

|||

|

R&D |

88.2 |

83.2 |

80.2 |

80.2 |

||||||||

|

Air Force One replacement |

R&D |

673.0 |

673.0 |

616.4 |

657.9 |

|||||||

|

VH-92 presidential helicopter |

Proc. |

6 |

649.0 |

6 |

649.0 |

6 |

649.0 |

6 |

649.0 |

|||

|

R&D |

245.1 |

245.1 |

245.1 |

245.1 |

||||||||

|

C-130 (new aircraft only) |

Proc. |

10 |

1,523.9 |

17 |

2,120.0 |

10 |

1,420.2 |

17 |

2,058.0 |

|||

|

R&D |

51.0 |

31.6 |

48.0 |

31.6 |

||||||||

|

P-8 Poseidon |

Proc. |

10 |

1,983.8 |

10 |

1,947.2 |

10 |

1,935.4 |

10 |

1,941.8 |

|||

|

R&D |

197.7 |

178.0 |

197.7 |

198,0 |

||||||||

|

E-2D Advanced Hawkeye |

Proc. |

4 |

983.4 |

6 |

1,312.8 |

5 |

1,144.9 |

6 |

1,313.1 |

|||

|

R&D |

223.6 |

211.5 |

238.1 |

210.6 |

||||||||

|

JSTARS replacement aircraft |

R&D |

0.0 |

623.0 |

30.0 |

0.0 |

|||||||

|

Rotary-wing and Tilt-rotor Aircraft |

||||||||||||

|

AH-64 Apache and mods (new and remanufactured aircraft) |

Proc. |

60 |

1,376.1 |

66 |

1,463.8 |

* |

2,096.1 |

66 |

1,544.1 |

|||

|

R&D |

31.0 |

31.0 |

24.0 |

24.0 |

||||||||

|

UH-60 Blackhawk (new aircraft and upgrades) |

Proc. |

68 |

1,262.3 |

76 |

1,369.4 |

83 |

1,590.8 |

76 |

1,413.1 |

|||

|

R&D |

35.2 |

35.2 |

35.2 |

35.2 |

||||||||

|

CH-47 Chinook (new and remanufactured aircraft) |

Proc. |

7 |

148.5 |

7 |

140.1 |

7 |

148.5 |

7 |

140.1 |

|||

|

R&D |

157.8 |

129.6 |

153.8 |

144.9 |

||||||||

|

CH-53K |

Proc. |

8 |

1,274.9 |

8 |

1,188.7 |

8 |

1,183.9 |

8 |

1,168.7 |

|||

|

R&D |

326.9 |

331.9 |

331.9 |

336.9 |

||||||||

|

UH-1/AH-1 (new aircraft and upgrades) |

Proc. |

25 |

820.8 |

25 |

798.4 |

25 |

820.8 |

25 |

798.4 |

|||

|

R&D |

58.1 |

53.1 |

58.1 |

54.3 |

||||||||

|

V-22 Osprey and mods |

Proc. |

7 |

1,118.5 |

13 |

1,439.0 |

7 |

1,307.5 |

13 |

1,421.5 |

|||

|

R&D |

161.6 |

152.0 |

161.6 |

152.0 |

||||||||

|

Search and Rescue Helicopter |

R&D |

457.7 |

457.7 |

384.7 |

445.7 |

|||||||

Sources: House Appropriations Committee, H. Rept.115-769, Report to accompany H.R. 6157, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2019; Senate Appropriations Committee, S. Rept. 115-290, Report to accompany S. 2159, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2019; H. Rept. 115-952, Conference Report to accompany H.R. 6157, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill.

Note: Full citations of CRS products are listed in the Appendix.

Appendix.

Following are the full citations of CRS products identified in tables by reference number only.

CRS Reports

CRS Report RS22103, VH-71/VXX Presidential Helicopter Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Jeremiah Gertler

CRS Report RS20643, Navy Ford (CVN-78) Class Aircraft Carrier Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke

CRS Report RL31384, V-22 Osprey Tilt-Rotor Aircraft Program, by Jeremiah Gertler

CRS Report RL32418, Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke

CRS Report RL33741, Navy Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke

CRS Report RL33745, Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke

CRS Report RL34398, Air Force KC-46A Tanker Aircraft Program, by Jeremiah Gertler

CRS Report R41129, Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke

CRS Report R41464, Conventional Prompt Global Strike and Long-Range Ballistic Missiles: Background and Issues, by Amy F. Woolf

CRS Report R42723, Marine Corps Amphibious Combat Vehicle (ACV): Background and Issues for Congress, by Andrew Feickert

CRS Report R43049, U.S. Air Force Bomber Sustainment and Modernization: Background and Issues for Congress, by Jeremiah Gertler

CRS Report R43240, The Army's Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV): Background and Issues for Congress, by Andrew Feickert

CRS Report R43618, C-130 Hercules: Background, Sustainment, Modernization, Issues for Congress, by Jeremiah Gertler and Timrek Heisler

CRS Report R44463, Air Force B-21 Raider Long-Range Strike Bomber, by Jeremiah Gertler

CRS Report R44968, Infantry Brigade Combat Team (IBCT) Mobility, Reconnaissance, and Firepower Programs, by Andrew Feickert

CRS Report R44972, Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke

Insight, In Focus

CRS Insight IN10931, U.S. Army's Initial Maneuver, Short-Range Air Defense (IM-SHORAD) System, by Andrew Feickert

CRS In Focus IF10954, Air Force OA-X Light Attack Aircraft Program, by Jeremiah Gertler