Introduction

On March 8, 2018, President Trump issued two proclamations imposing tariffs on U.S. imports of certain steel and aluminum products, respectively, using presidential powers granted under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962.1 Section 232 authorizes the President to impose restrictions on certain imports based on an affirmative determination by the Department of Commerce (Commerce) that the targeted products are being imported into the United States "in such quantities or under such circumstances as to threaten to impair the national security." Section 232 investigations and actions are important for Congress, as the Constitution gives it primary authority over international trade matters. In the case of Section 232, Congress has delegated to the President broad authority to impose limits on imports in the interest of U.S. national security. The statute does not require congressional approval of any presidential actions that fall within its scope. In the Crude Oil Windfall Profit Tax Act of 1980, however, Congress amended Section 232 by creating a joint disapproval resolution provision under which Congress can override presidential actions in the case of adjustments to petroleum or petroleum product imports.2

Section 232 is one of several tools the United States has at its disposal to address trade barriers and other foreign trade practices. These include investigations and actions to address import surges that are a "substantial cause of serious injury" or threat thereof to a U.S. industry (Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974), those that address violations or denial of U.S. benefits under trade agreements (Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974), and antidumping and countervailing duty laws (Title VII of the Tariff Act of 1930).

Trade is an important component of the U.S. economy, and Members often hear from constituents when factories and other businesses are hurt by competing imports, or if exporters face trade restrictions and other market access barriers overseas. Section 232 actions may affect industries, workers, and consumers in congressional districts and states (both positively and negatively). Following the steel and aluminum Section 232 actions, Commerce initiated Section 232 investigations into imports of automobiles and automobile parts in May 2018, uranium ore and product imports in July 2018, and titanium sponges in March 2019. Commerce submitted the auto investigation report to the President on February 17, 2019, but the report has not been made public or shared with Congress; the uranium report is expected by mid-April 2019, and the titanium sponges report is due in late November 2019. The current investigations have raised a number of economic and broader policy issues for Congress.

This report provides an overview of Section 232, analyzes the Trump Administration's Section 232 investigations and actions, and considers potential policy and economic implications and issues for Congress. To provide context for the current debate, the report also includes a discussion of previous Section 232 investigations and a brief legislative history of the statute.

Overview of Section 232

The Trade Act of 1962, including Section 232, was enacted during the Cold War when national security issues were at the forefront. Section 232 has been used periodically in response to industry petitions, as well as through self-initiation by the executive branch. The Trade Expansion Act establishes a clear process and timelines for a Section 232 investigation, but the executive branch's interpretation of "national security" and the potential scope of any investigation can be expansive.

Key Provisions and Process

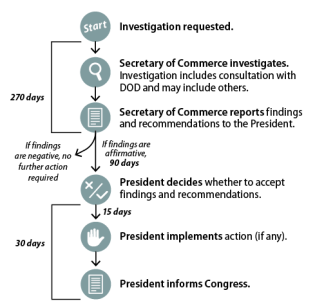

Upon request by the head of any U.S. department or agency, by application by an interested party, or by self-initiation, the Secretary of Commerce must commence a Section 232 investigation. The Secretary of Commerce conducts the investigation in consultation with the Secretary of Defense and other U.S. officials, as appropriate, to determine the effects of the specified imports on national security. Public hearings and consultations may also be held in the course of the investigation. Commerce has 270 days from the initiation date to prepare a report advising the President whether or not the targeted product is being imported "in such quantities or under such circumstances as to threaten to impair" U.S. national security, and to provide recommendations for action or inaction based on the findings. Any portion of the report that does not contain classified or proprietary information must be published in the Federal Register. See Figure 1 for the Section 232 process and timeline.

While there is no specific definition of national security in the statute, it states that the investigation must consider certain factors, such as domestic production needed for projected national defense requirements; domestic capacity; the availability of human resources and supplies essential to the national defense; and potential unemployment, loss of skills or investment, or decline in government revenues resulting from displacement of any domestic products by excessive imports.3

Once the President receives the report, he has 90 days to decide whether or not he concurs with the Commerce Department's findings and recommendations, and to determine the nature and duration of the action he views as necessary to adjust the imports so they no longer threaten to impair the national security (generally, imposition of some trade-restrictive measure). The President may implement the recommendations suggested in the Commerce report, take other actions, or decide to take no action. After making a decision, the President has 15 days to implement the action and 30 days to submit a written statement to Congress explaining the action or inaction; he must also publish his findings in the Federal Register. Presidential actions may stay in place "for such time, as he deems necessary to adjust the imports of such article and its derivatives so that such imports will not so threaten to impair the national security."4

|

|

Source: CRS graphic based on 19 U.S.C. §1862. |

Section 232 Investigations to Date

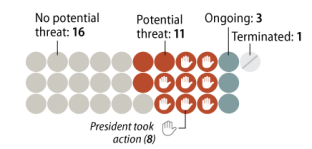

The Commerce Department (or the Department of the Treasury before it) initiated a total of 31 Section 232 investigations between 1962 and 2019, including three investigations that remain ongoing (see Table B-1). In 16 of these cases, Commerce determined that the targeted imports did not threaten to impair national security. In 11 cases, Commerce determined that the targeted imports threatened to impair national security and made recommendations to the President. The President took action eight times. One case was terminated at the petitioner's request before Commerce completed its investigation. Prior to the Trump Administration, 10 Section 232 investigations were self-initiated by the Administration. (For a full list of cases to date, see Appendix B.)

In eight investigations dealing with crude oil and petroleum products, Commerce decided that the subject imports threatened to impair national security. The President took action in five of these cases. In the first three cases on petroleum imports (1973-1978), the President imposed licensing fees and additional supplemental fees on imports, which are no longer in effect, rather than adjusting tariffs or instituting quotas. In two cases, the President imposed oil embargoes, once in 1979 (Iran) and once in 1982 (Libya). Both were superseded by broader economic sanctions in the following years.5

In the three most recent crude oil and petroleum investigations (from 1987 to 1999), Commerce determined that the imports threatened to impair national security, but did not recommend that the President use his authority to adjust imports. In the first of these reports (1987), Commerce recommended a series of steps to increase domestic energy production and ensure adequate oil supplies rather than imposing quotas, fees, or tariffs because any such actions would not be "cost beneficial and, in the long run, impair rather than enhance national security."6 In the latter two investigations (1994 and 1999), Commerce found that existing government programs and activities related to energy security would be more appropriate and cost effective than import adjustments. By not acting, the President in effect followed Commerce's recommendation.

Prior to the Trump Administration, a President arguably last acted under Section 232 in 1986. In that case, Commerce determined that imports of metal-cutting and metal-forming machine tools threatened to impair national security. In this case, the President sought voluntary export restraint agreements with leading foreign exporters, and developed domestic programs to revitalize the U.S. industry.7 These agreements predate the founding of the World Trade Organization (WTO), which established multilateral rules prohibiting voluntary export restraints (see "WTO Cases ").

In addition to the two recent cases on steel and aluminum, on May 23, 2018, after consultations with President Trump, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross announced the initiation of a Section 232 investigation to determine whether imports of automobiles, including SUVs, vans and light trucks, and automotive parts threaten to impair national security.8 In January 2018, two U.S. mining companies petitioned for the investigation into uranium imports.9 On July 18, Commerce announced the initiation of a Section 232 investigation on these imports and informed the Secretary of Defense.10 In September 2018, a U.S. titanium company petitioned for the investigation into titanium sponge imports. In March 2019, Commerce announced the initiation of a Section 232 investigation on these imports and informed the Secretary of Defense.11

|

|

Source: CRS Graphic based on BIS data (https://www.bis.doc.gov/). Note: For a detailed list of cases, see Appendix B. |

Relationship to WTO

While unilateral trade restrictions may appear to be counter to U.S. trade liberalization commitments under the WTO agreements, Article XXI of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which predates and was one of the foundational agreements of the WTO, allows WTO members to take measures to protect "essential security interests." Broad national security exceptions are also included in international trade obligations at the bilateral and regional levels, and could potentially limit the ability of countries to challenge such actions by trade partners. Historically, exceptions for national security have been rarely invoked and multiple trading partners have challenged recent U.S. actions under the WTO agreements (see "WTO Cases ").

Recent Section 232 Actions on Steel and Aluminum

In April 2017, two presidential memoranda instructed Commerce to give priority to two self-initiated investigations into the national security threats posed by imports of steel and aluminum.12 In conducting its investigation, Commerce held public hearings and solicited public comments via the Federal Register and consulted with the Secretary of Defense and other agencies, as required by the statute.13 In addition to the hearings, stakeholders submitted approximately 300 comments regarding the Section 232 investigation and potential actions. Some parties (mostly steel producers) supported broad actions to limit steel imports, while others (mostly users and consuming industries such as automakers) opposed any additional tariffs or quotas on imports. The U.S. aluminum industry held differing views of the global aluminum tariff, with most parties opposing it.14 Some stakeholders in the steel and aluminum industries sought a middle ground, endorsing limited actions to target the underlying issues of overcapacity and unfair trade practices. Still others focused on the process, voicing caution in the use of Section 232 authority and warning against an overly broad definition of "national security" for protectionist purposes.15

The Commerce investigations analyzed the importance of certain steel and aluminum products to national security, using a relatively broad definition of "national security," defining it to include "the general security and welfare of certain industries, beyond those necessary to satisfy national defense requirements, which are critical for minimum operations of the economy and government."16 The scope of the investigations extended to current and future requirements for national defense and to 16 specific critical infrastructure sectors, such as electric transmission, transportation systems, food and agriculture, and critical manufacturing, including domestic production of machinery and electrical equipment. The reports also examined domestic production capacity and utilization, industry requirements, current quantities and circumstances of imports, international markets, and global overcapacity. Commerce based its definition of national security on a 2001 investigation on iron ore and semi-finished steel.17 Section 232 investigations prior to 2001 generally used a narrower definition considering U.S. national defense needs or overreliance on foreign suppliers.

Commerce Findings and Recommendations

The final reports, submitted to the President on January 11 and January 22, 2018, respectively, concluded that imports of certain steel mill products18 and of certain types of primary aluminum and unwrought aluminum19 "threaten to impair the national security" of the United States. The Secretary of Commerce asserted that "the only effective means of removing the threat of impairment is to reduce imports to a level that should ... enable U.S. steel mills to operate at 80 percent or more of their rated production capacity" (the minimum rate the report found necessary for the long-term viability of the U.S. steel industry and, separately, for the aluminum industry). The Secretary further recommended the President "take immediate action to adjust the level of these imports through quotas or tariffs" and identified three potential courses of action for both steel and aluminum imports, including tariffs or quotas on all or some steel imports from specific countries.

The Secretary of Defense, while concurring with Commerce's "conclusion that imports of foreign steel and aluminum based on unfair trading practices impair the national security," recommended targeted tariffs and that "an inter-agency group further refine the targeted tariffs, so as to create incentives for trade partners to work with the U.S. on addressing the underlying issue of Chinese transshipment" in which Chinese producers ship goods to another country to reexport.20 He also noted, however, that "the U.S. military requirements for steel and aluminum each only represent about three percent of U.S. production."21

Presidential Actions

On March 8, 2018, President Trump issued two proclamations imposing duties on U.S. imports of certain steel and aluminum products, based on the Secretary of Commerce's findings.22 The proclamations outlined the President's decisions to impose tariffs of 25% on steel and 10% on aluminum imports effective March 23, 2018, but provided for flexibility in regard to country and product applicability of the tariffs (see below). The new tariffs were to be imposed in addition to any duties already in place, including antidumping and countervailing duties.

In the proclamations, the President established a bifurcated approach, instructing Commerce to establish a process for domestic parties to request individual product exclusions and a U.S. Trade Representative (USTR)-led process to discuss "alternative ways" through diplomatic negotiations to address the threat with countries having a "security relationship" with the United States.

The President officially notified Congress of his actions in a letter dated April 6, 2018. Several Members actively engaged in voicing their views since the investigations were launched, including through hearings and letters to the President.23

Country Exemptions

Initially, the President temporarily excluded imports of steel and aluminum products from Mexico and Canada from the new tariffs, and the Administration implicitly and explicitly linked a successful outcome of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) renegotiation to maintaining the exemptions. With regard to other countries, the President expressed a willingness to be flexible, stating that countries with which the United States has a "security relationship" may discuss "alternative ways" to address the national security threat and gain an exemption from the tariffs. The President charged the USTR with negotiating bilaterally with trading partners on potential exemptions.

On March 22, after discussions with multiple countries, the President issued proclamations temporarily excluding Australia, Argentina, Brazil, South Korea, the European Union (EU), Canada and Mexico, from the Section 232 tariffs.24 The President gave a deadline of May 1, 2018, by which time each trading partner had to negotiate "a satisfactory alternative means to remove the threatened impairment to the national security by imports" for steel and aluminum in order to maintain the exemption. On April 30, 2018, the White House extended negotiations and tariff exemptions with Canada, Mexico, and the EU for an additional 30 days, until June 1, 2018, and exempted Argentina, Australia, and Brazil from the tariffs indefinitely pending final agreements.25 South Korea, which pursued a resolution over the tariffs in the context of discussions to modify the U.S.-South Korea (KORUS) Free Trade Agreement, agreed to an absolute annual quota for 54 separate subcategories of steel and was exempted from the steel tariffs.26 South Korea did not negotiate an agreement on aluminum and its exports to the United States have been subject to the aluminum tariffs since May 1, 2018.

On May 31, 2018, the President proclaimed Argentina and Brazil, in addition to South Korea, permanently exempt from the steel tariffs, having reached final quota agreements with the United States on steel imports.27 Brazil, like South Korea, did not negotiate an agreement on aluminum and is subject to the aluminum tariffs. The Administration also proclaimed aluminum imports from Argentina permanently exempt from the aluminum tariffs subject to an absolute quota.28 The Administration proclaimed imports of steel and aluminum from Australia permanently exempt from the tariffs as well, but did not set any quantitative restrictions on Australian imports.

As of June 1, 2018, imports of steel and aluminum from Canada, Mexico, and the European Union are subject to the Section 232 tariffs. These countries are among the largest suppliers of U.S. imports of the targeted goods, accounting for nearly 50% by value in 2018 (see Appendix D). The imposition of tariffs on these major trading partners increases the economic significance of the tariffs and prompted criticism from several Members of Congress, including the chairs of the House Ways and Means and Senate Finance Committees.29

The Trump Administration completed negotiations on the proposed United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) on September 30, 2018, to replace the NAFTA. The USMCA did not resolve or address the Section 232 tariffs on imported steel and aluminum from Canada and Mexico, but it includes a requirement that motor vehicles contain 70% or more of North American steel and aluminum content to qualify for duty-free treatment.30 The three parties continue to discuss the steel and aluminum tariffs, which some analysts speculate could result in quotas on imports of Mexican and Canadian steel and aluminum. Some U.S., Canadian, and Mexican policymakers have suggested that the parties will not ratify the new agreement until the Section 232 tariffs are removed; the White House economic adviser stated that the Administration continues to negotiate the tariffs as "part of the bigger legislative picture discussion" for passage of USMCA.31

With respect to the EU, on July 27, 2018, after meeting with EU President Juncker, President Trump announced plans for "high-level trade negotiations" to eliminate tariffs, including those on steel and aluminum, among other objectives. The two sides agreed to not impose further tariffs on each other's trade products while negotiations are active.32 It is unclear what those negotiations may seek in terms of alternative measures, but the United States could seek some type of quantitative restriction given the agreements the Administration has negotiated to date with most exempted countries.33 In addition to seeking quantitative restrictions, the Trump Administration may also pursue increasing traceability and reporting requirements, which may help limit transshipments of steel or aluminum originating from nonexempt countries.

|

Tariff Increase on U.S. Steel and Aluminum Imports from Turkey On August 10, 2018, President Trump issued a proclamation raising the Section 232 tariff to 50% on covered steel imports from Turkey. The President justified the action by stating "imports have not declined as much as anticipated and capacity utilization has not increased to [the] target level."34 The value of the Turkish lira relative to the U.S. dollar has declined by roughly 40% since the date that the Section 232 tariffs went into effect until August, when the President proclaimed the adjusted tariff rate.35 A depreciated lira makes U.S. imports from Turkey less costly to U.S. consumers, thereby counteracting the effect of the tariffs. The President noted the exchange rate volatility in his informal announcement of the tariff increase, but some observers contend that the action may be in response to ongoing foreign policy issues unrelated to trade.36 In addition, the President announced in a tweet on August 10 that he had authorized an increase of the tariff on aluminum from Turkey to 20%, but he has not yet signed a Section 232 proclamation putting the higher duty into effect. In 2018, Turkey was the 13th-largest supplier of U.S. steel imports covered by the tariffs, accounting for $779 million of U.S. imports (approximately 2.6% of relevant U.S. steel imports). U.S. steel imports from Turkey decreased by 35% (-$413 million) from 2017 to 2018, the year the tariffs took effect. |

Product Exclusions

To limit potential negative domestic impacts of the tariffs on U.S. consumers and consuming industries, Commerce published an interim final rule for how parties located in the United States may request exclusions for items that are not "produced in the United States in a sufficient and reasonably available amount or of a satisfactory quality."37 Requests for exclusions and objections to requests have been and will continue to be posted on regulations.gov.38 The rule went into effect the same day as publication to allow for immediate submissions.

Exclusion determinations are based upon national security considerations. To minimize the impact of any exclusion, the rule allows only "individuals or organizations using steel articles ... in business activities ... in the United States to submit exclusion requests," eliminating the ability of larger umbrella groups or trade associations to submit petitions on behalf of member companies.39 Any approved product exclusion is limited to the individual or organization that submitted the specific exclusion request. Parties may also submit objections to any exclusion within 30 days after the exclusion request is posted. The review of exclusion requests and objections will not exceed 90 days, creating a period of uncertainty for petitioners. Exclusions will generally last for one year from the date of signature.40

As of March 4, 2019, Commerce received almost 70,000 steel product exclusion requests, with 16,500 exclusions granted and 500 denied.41 As of the same date, Commerce received 10,000 aluminum exclusion requests, with 3,000 exclusions granted and 500 denied.42

Companies have complained about the intensive, time-consuming process to submit exclusion requests; the lengthy waiting period to hear back from Commerce, which has exceeded the 90 days in some cases; what some view as an arbitrary nature of acceptances and denials; and that all exclusion requests to date have been rejected when a U.S. steel or aluminum producer has objected.43 Alcoa, the largest U.S. aluminum maker, requested an exemption for all aluminum imported from Canada, where it operates three aluminum smelters. While the company benefits from higher aluminum prices as a result of the tariffs, it is also seeing increased costs in its own supply chain.44 In addition, the Cause of Action Institute filed a series of Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to gain insight into the exclusion process. Commerce did not respond, leading the organization to file a lawsuit against the agency.45

Several Members of Congress have raised concerns about the exclusion process. A bipartisan group of House Members, for example, raised concerns about the speed of the review process and the significant burden it places on manufacturers, especially small businesses.46 The Members included specific recommendations, such as allowing for broader product ranges to be included in a single request, allowing trade associations to petition, grandfathering in existing contracts to avoid disruptions, and regularly reviewing the tariffs' effects and sunsetting them if they have a "significant negative impact."47

Commerce asserts it has taken several steps to improve the exclusion process, including increasing and organizing its staff "to efficiently process exclusion requests," and "expediting the grant of properly filed exclusion requests that receive no objections." The agency's International Trade Administration (ITA) also became involved in the exclusion process by analyzing exclusion requests and objections to determine whether there is sufficient domestic production available to meet the requestor's product needs.48 BIS remains the lead agency involved in making final decisions regarding whether the requests are granted or denied.

Some Members have questioned the Administration's processes and ability to pick winners and losers through granting or denying exclusion requests. On August 9, 2018, Senator Ron Johnson requested that Commerce provide specific statistics and information on the exclusion requests and process and provide a briefing to the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. Senator Elizabeth Warren requested that the Commerce Inspector General investigate the implementation of the exclusion process, including a review of the processes and procedures Commerce has established; how they are being followed; and if exclusion decisions are made on a transparent, individual basis, free from political interference. She also requested evidence that the exclusions granted meet Commerce's stated goal of "protecting national security while also minimizing undue impact on downstream American industries," and that the exclusions granted to date strengthen the national security of the United States.49 Pending legislation to revise Section 232 also addresses the process for excluding products (e.g., S. 287).

On September 6, 2018, Commerce announced a new rule to allow companies to rebut objections to petitions.50 The new rule, published September 11, 2018, includes new rebuttal and counter-rebuttal procedures, more information about the exclusion submission requirements and process, the criteria Commerce uses in deciding whether to grant an exclusion request, and revised estimates of the total number of exclusion requests and objections that Commerce expects to receive.51 On October 29, 2018, the Commerce Inspector General's office (IG) initiated an audit of the agency's processes and procedures for reviewing and adjudicating product exclusion requests.52 The audit is ongoing.

To ensure that Commerce follows through with improving the exclusion process, in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6), signed on February 15, 2019, Congress provided funding for "contractor support to implement the product exclusion process for articles covered by actions taken under section 232."53 To ensure improvements to the exclusion process, Congress indicated that the additional money is to be "devoted to an effective Section 232 exclusion process" and required that Commerce submit quarterly reports to Congress.54 Congress mandated that the reports identify

- the number of exclusion requests received;

- the number of exclusion requests approved and denied;

- the status of efforts to assist small- and medium-sized businesses in navigating the exclusion process;

- Commerce-wide staffing levels for the exclusion process, including information on any staff detailed to complete this task; and

- Commerce-wide funding by source appropriation and object class for costs undertaken to process the exclusions.

Tariffs Collected to Date

As of March 28, 2019, U.S. Customs and Border Protection assessed $4.7 billion and $1.5 billion from the Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum, respectively. The tariffs collected are put in the general fund of the U.S. Treasury and are not allocated to a specific fund. Based on 2017 U.S. import values, annual tariff revenue from the Section 232 tariffs could be as high as $5.8 billion and $1.7 billion for steel and aluminum, respectively, but such estimates do not account for dynamic effects that may impact import flows.

Generally, higher import prices resulting from the tariffs should cause both import demand and tariff revenue to decrease over time, provided that U.S. production increases and sufficient domestic alternatives become available. Tariff revenue is also likely to decline as the Commerce Department grants additional product exclusions.

According to the President's proclamations implementing the Section 232 tariffs, one of the objectives of the tariffs is to "reduce imports to a level that the Secretary assessed would enable domestic steel (and aluminum) producers to use approximately 80 percent of existing domestic production capacity and thereby achieve long-term economic viability through increased production."55

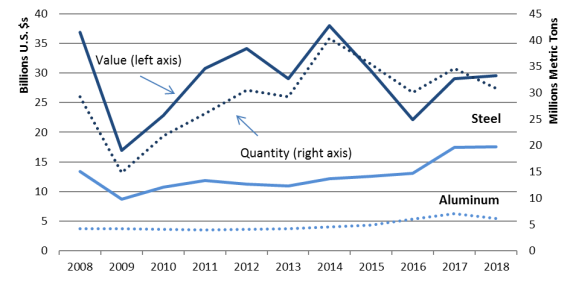

U.S. Steel and Aluminum Industries and International Trade

In 2018, U.S. imports of steel and aluminum products covered by the Section 232 tariffs totaled $29.5 billion and $17.6 billion, respectively (see Appendix D).56 Over the past decade, steel imports have fluctuated significantly, by value and quantity, while imports of aluminum have generally increased. U.S. imports of both metals increased slightly by value from 2017 to 2018 (Section 232 tariffs became effective at different times for different countries), but imports of both decreased by more than 10% in quantity terms (-3.8 million metric tons for steel and -0.9 million metric tons for aluminum).57 U.S. imports from individual countries fluctuated to an even greater degree over the past year (Figure 3). The largest declines in U.S. steel imports, by value, were from South Korea (-$430 million, -15%), Turkey (-$413 million, -35%), and India (-$372 million, -49%), with significant increases from the EU (+$567 million, +22%), Mexico (+$508 million, +20%), and Canada (+$404 million, +19%). The largest declines in aluminum imports were from China (-$729 million, -40%), Russia (-$676 million, -42%), and Canada (-$294 million, -4%), with major increases from the EU (+$395 million, 9%), India (+$221 million, 58%), and Oman ($186 million, +200%). The countries with permanent exclusions from the tariffs (all except Australia are instead subject to quotas) accounted for 18.4% of U.S. steel imports in 2018 and 4.4% of U.S. aluminum imports.

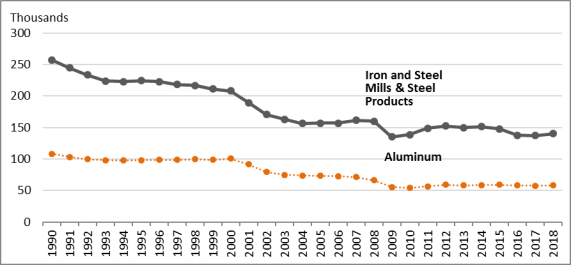

In 2018, U.S. steelmakers employed 140,100 workers (Figure 4), accounting for 1.1% of the nation's 12.7 million factory jobs. Employment in the steel industry has declined for many years as new technology, particularly the increased use of electric arc furnaces to make steel, has reduced the demand for workers.58 According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, labor productivity in steelmaking nearly tripled since 1987 and rose 20% over the past decade.59 Hence, even a significant increase in domestic steel production is likely to result in a relatively small number of additional jobs. In 2018, for the first time since 2014, steel manufacturers added 2,700 jobs, a rise of 2% from a year earlier.

Aluminum manufacturers employed 58,100 workers in 2018, a figure that has changed little since the 2007-2009 recession. Domestic smelting of aluminum from bauxite ore, which requires large amounts of electricity, has been in long-term decline, and secondary aluminum produced from recycled scrap melted in a smelter now accounts for the majority of domestic aluminum production.60 Imports of secondary unwrought aluminum are not covered by the Section 232 aluminum trade action.61

|

|

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Employment Survey for North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) 3311 (iron and steel mills), 3312 (steel products), and NAICS 3313 (aluminum). |

Steelmaking and aluminum smelting are both extremely capital intensive. As a result, even small changes in output can have major effects on producers' profitability. Domestic steel producers have operated at 80% or less of production capacity in recent years, with a shift in recent months to a capacity utilization rate at U.S. steel mills of more than 80%.62 Primary aluminum producers in the United States have operated at about 78% of production capacity in December 2018, up from around 43% in December 2017.63 A stated aim of the metals tariffs is to enable U.S. producers in both sectors to use an average of 80% of their production capacity, which the Section 232 reports deem necessary to sustain adequate profitability and continued capital investment.64

Global Production Trends

The OECD Global Forum on Steel Excess Capacity estimates global steel overcapacity was at 595 million metric tons in 2017.65 While China is the world's largest steel producer, accounting for roughly 45% of global capacity, relatively little Chinese steel enters the U.S. market directly, due to extensive U.S. dumping and subsidy determinations, but the large amount of Chinese production acts to depress prices globally. China has indicated that it plans to reduce its crude steelmaking capacity by 100-150 million metric tons over the five-year period from 2016 to 2020.66 According to the Chinese government, the country's crude steel capacity has fallen by more than 120 million metric tons since it announced its steel reduction goal in 2016.67

No OECD or other multinational forum has been established to monitor global aluminum overcapacity, though aluminum industry groups have called for such a forum.68 Although China accounted for more than half of the world's primary aluminum production in 2017, it does not export aluminum in commodity form to the United States. China ships semi-finished aluminum such as bars, rods, and wire to the United States. These are subject to the Section 232 tariffs.69

Metals imports should be put in the context of U.S. production. In 2018, the United States produced more than twice the amount of steel it imported. According to ITA, import penetration—the share of U.S. demand met by steel imports—reached 33% in 2016, compared to 23% in 2006.70 Some segments of the domestic steel industry, such as slab converters, import a sizable share of their semi-finished feedstock from foreign suppliers, totaling nearly 7.5 million tons in 2018.71 In the primary aluminum market, U.S. net import reliance rose to 50% in 2018 from 33% in 2014, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.72 Most U.S. foreign trade in steel and aluminum is with Canada (see Appendix C).

International Efforts to Address Overcapacity

OECD analysis has found that ongoing global steel overcapacity and excess production are largely caused by government intervention, subsidization, and other market-distorting practices, although these are not the only factors.73 Other reasons for excess capacity include cyclical market downturns. The situation is similar in the aluminum industry, where government financial support for large aluminum stockpiles has delayed the response to lower demand.

Past Administrations worked to address the issue of steel overcapacity. President George W. Bush, for example, initiated international discussions on global capacity reduction and improved trade discipline in the steel industry as part of his general steel announcement of 2001.74 Other governments agreed to join the Bush Administration in discussing overcapacity and trade issues at the OECD in a process that started in mid-2001. The industrial, steel-producing members of the OECD were joined by major non-OECD steel producers, such as India, Russia, and, during later stages of the talks, China. Negotiations were suspended indefinitely in 2004, and by 2005, the OECD had abandoned this effort to negotiate an agreement among all major steel-producing countries to ban domestic subsidies for steel mills.

The Obama Administration also participated in international efforts to curb steel imports, including the launch of the G-20 Global Forum on Steel Excess Capacity in 2016, another venue that sought to address the challenges of excess capacity in steel worldwide.75 In December 2016, the G-20 convened its first meeting of more than 30 economies—all G-20 members plus interested OECD members—as a global platform to discuss steel issues among the world's major producers.76 The same year, as part of the U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue (SE&D) established in 2009, the Obama Administration agreed to address excess steel production and also to communicate and exchange information on surplus production in the aluminum sector.77

In September 2018, the OECD Forum agreed on a process to identify and remove subsidies and take other measures to reduce the global steel overcapacity. The OECD issued a consensus report outlining six principles and specific policy recommendations to address excess steel capacity.78 The USTR, while supportive of the recommendations, questioned the Forum's ability to pursue effective implementation and did not rule out unilateral action.79

The aluminum industry argues it is also suffering because of China's excess production of primary aluminum. According to the aluminum associations of Japan, Europe, Canada, and the United States, global overcapacity amounted to 11 million metric tons in 2017. Akin to the global steel industry, aluminum producers contend that excess production has been largely caused by government intervention, subsidization, and other market-distorting practices, among other factors.80 As noted, the U.S. Aluminum Association and some of its international counterparts seek to establish a global forum to address aluminum excess capacity.

The Trump Administration's Section 232 actions have led multiple U.S. trading partners, such as the EU, the UK, and Canada, to initiate their own safeguard investigations and quota restrictions to prevent dumping of steel and aluminum exports and protect domestic industries. Unlike the OECD efforts, the individual country safeguard actions are uncoordinated.

In addition to the Section 232 action, the Trump Administration is pursuing joint action on industrial overcapacity in other forums. The USTR, Ambassador Lighthizer, met with his EU and Japanese counterparts in May 2018, and the three countries agreed to concrete steps to address "nonmarket-oriented policies and practices that lead to severe overcapacity, create unfair competitive conditions for our workers and businesses, hinder the development and use of innovative technologies, and undermine the proper functioning of international trade."81 The ministers agreed to work toward negotiation of new international rules on subsidies and state-owned enterprises and improved compliance with WTO transparency commitments.82 The parties also agreed to cooperate on their concerns with third parties' technology transfer policies and practices83 and issued a joint statement containing a list of factors that identify if market conditions for competition exist.84 The parties have met multiple times and continue to work together, aiming to identify signals for nonmarket policies, enhance information sharing, and work with third parties to ensure market economy conditions exist and discuss potential new rules and means of enforcement.85 In addition, in November 2018, the United States, the EU, Japan, Argentina, and Costa Rica put forward a joint proposal in the WTO to increase transparency, proposing incentives for compliance or penalties for noncompliance with WTO notification reporting requirements regarding subsidies.86 U.S. unilateral tariff actions, however, may limit other countries' willingness to participate in multilateral forums.

Policy and Economic Issues

Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum imports into the United States raise a number of issues for Congress. The economic repercussions of U.S. and foreign actions may be felt not only by domestic steel and aluminum producers, but by downstream manufacturers or other industries targeted for retaliation, and consumers. The response by other countries can have implications for the U.S. economy and multilateral world trading system. Also, other countries may be hesitant in the future to cooperate with the United States to address broader global issues, including steel and aluminum overcapacity, if their exports are subject to U.S. tariffs.

U.S. trading partners' responses to Section 232 actions have varied based on the country's relationship with the United States. Some countries are pursuing direct negotiations, while keeping other countermeasures in reserve, and raising actions at the WTO (see below). Others have proposed or pursued retaliation with their own tariffs. Some companies have pursued litigation,87 and may also seek alternative markets for their own products to avoid U.S. tariffs.

Retaliation

Several major U.S. trading partners have proposed or are imposing retaliatory tariffs in in response to the U.S. actions (see Figure 5 below).88 In total, retaliatory tariffs are in effect on products accounting for approximately $23.2 billion of U.S. exports in 2018. The process of retaliation is complex given multiple layers of relevant international rules and the potential for unilateral action, which may or may not adhere to those existing rules. Both through agreements at the WTO and in bilateral and regional free trade agreements (FTAs), the United States and its trading partners have agreed to maintain certain tariff levels. Those same agreements include rules on potential responses, including formal dispute settlement procedures and in some cases commensurate tariffs, when one party increases its tariffs above agreed-upon limits.89 In addition to the national security considerations the Trump Administration has cited as justification for its Section 232 actions, increased tariffs are permitted under these agreements, under specific circumstances, including for example, antidumping tariffs, countervailing duties, and safeguard tariffs.90

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of Global Trade Atlas IHS Markit trade data. Retaliatory tariff lists sourced from WTO notifications and partner country notifications. See footnote footnote 88 for complete sourcing. Notes: U.S. exports approximated by using partner country import data. U.S. Section 232 actions target steel and aluminum imports, and steel and aluminum are among the top exports facing retaliation by several U.S. trading partners as highlighted above. (*) June 5, 2018, for the majority of products, with remaining effective July 5, 2018. (**) Turkey announced on August 18, 2018, an increase in its retaliatory tariff rates, in response to the Trump Administration's decision to increase the U.S. tariffs on Turkish steel to 50%. It is unclear from the notice when these additional tariff rates went fully into effect. (***) Russia published its list of retaliatory tariffs rates and products on July 6, 2018. The tariffs appear to have gone into effect within 30 days of the publication. |

The retaliatory actions of U.S. trading partners to date have been notified to the WTO pursuant to the Agreement on Safeguards. These retaliatory notifications are in addition to ongoing WTO dispute settlement proceedings (see "WTO Cases "). FTA partner countries may also claim that the increase in U.S. tariff rates violates U.S. FTA commitments and seek recourse through those agreements. For example, Canada and Mexico, U.S. partners in NAFTA, claim that the U.S. actions violate commitments in both NAFTA and the WTO agreements. Canada initially announced its intent to launch a dispute under the NAFTA's dispute settlement provisions in addition to actions at the WTO, although it appears Canada has taken no such action to date.91

U.S. trading partners' retaliation to the Trump Administration's Section 232 tariff actions has magnified the effects of the Section 232 tariffs. From an economic perspective, retaliation increases the scope of industries affected by the tariffs. U.S. agriculture exports, for example, are among the largest categories of U.S. exports targeted for retaliation, which may have contributed to reduced sales of certain U.S. farm products.92 Given the scale of U.S. motor vehicle and parts imports, if the Trump Administration moves forward with Section 232 tariffs on that sector and U.S. trading partners respond with retaliation of a similar magnitude, it could have significant negative effects on U.S. exporters. For example, the United States imported more than $50 billion of motor vehicles and parts from the EU in 2018,93 and the EU has announced it has prepared potential retaliatory tariffs on a commensurate value of U.S. exports.94

Retaliatory actions may also heighten concerns over the potential strain the Section 232 tariffs place on the international trading system. Many U.S. trading partners view the Section 232 actions as protectionist and in violation of U.S. commitments at the WTO and in U.S. FTAs, while the Trump Administration views the actions within its rights under those same commitments.95 Furthermore, the Trump Administration argues that retaliation to its Section 232 tariffs, which U.S. trading partners have imposed under WTO safeguard commitments, violates WTO rules because it has imposed Section 232 tariffs pursuant to WTO national security exceptions. If the dispute settlement process in those agreements cannot satisfactorily resolve this conflict, it could lead to further unilateral actions and increasing retaliation.

Domestic Court Challenges

The President's actions under Section 232 have resulted in legal challenges in the U.S. domestic court system. Specifically, the Section 232 actions on steel and aluminum have been challenged in cases before the U.S. Court of International Trade (CIT). In one case, Severstal Export Gmbh, a U.S. subsidiary of a Russian steel producer, sought a preliminary injunction from the United States Court of International Trade to prevent the United States from collecting the import tariffs on certain steel products.96 The company and its Swiss affiliate argued that the President acted outside of the authority that Congress had delegated to him because the tariffs were not truly imposed for national security purposes.97 The court denied the motion, determining that the plaintiffs were unlikely to prevail on the merits of their challenge.98 According to the case docket, the parties agreed to dismiss the case in May 2018.

In another case, which was heard by a three-judge panel of the court, the American Institute for International Steel (AIIS), a trade association, challenged the constitutionality of Congress's delegation of authority to the President under Section 232.99 The plaintiffs in the case argued that "Congress created an unconstitutional regime in section 232, in which there are essentially no limits or guidelines on the trigger or the remedies available to the President, and no alternative protections to assure that the President stays within the law, instead of making the law himself."100

On March 25, 2019, the court issued an opinion rejecting the plaintiffs' arguments that Congress delegated too much of its legislative power to the President in Section 232, in violation of the separation of powers established in the Constitution.101 In granting the United States' motion for judgment on the pleadings, the court held that it was bound by a 1976 Supreme Court precedent determining that Section 232 did not amount to an unconstitutional delegation because it established an "intelligible principle" to guide presidential action.102

One member of the three-judge panel, Judge Katzmann, wrote separately to express his significant concerns about the ruling without openly dissenting.103 Katzmann wrote that he was bound to follow Supreme Court precedent and uphold the delegation but questioned whether the nondelegation doctrine retained any significant meaning if a delegation as broad as that in Section 232 was permissible.104 The case is currently under appeal.

Most recently, U.S. importers of Turkish steel have initiated a case arguing that the President's increase of the Section 232 steel tariffs from 25% to 50% on U.S. imports from Turkey did not have a sufficient national security rationale, did not follow statutory procedural mandates, and violates the plaintiffs' Fifth Amendment Due Process rights because the action "creates an arbitrary distinction between importers of steel products from Turkey and importers of steel products from all other sources."105 The case remains pending before the CIT.

WTO Cases

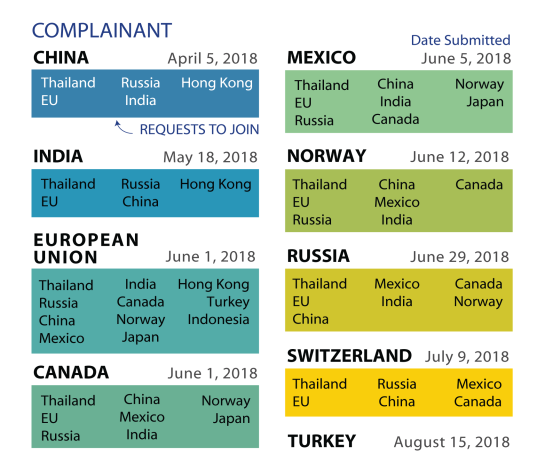

The President's imposition of tariffs on certain imports of steel and aluminum products,106 as well as Commerce's exemption of certain WTO members' products from such tariffs, may also have implications for the United States under WTO agreements. As an example, on April 9, 2018, China took the first step in challenging the executive branch's actions as violating U.S. obligations under the WTO agreements (particularly the Agreement on Safeguards) by requesting consultations with the United States.107 Under WTO dispute settlement rules, members must first attempt to settle their disputes through consultations. If these fail, the member initiating a dispute may request the establishment of a dispute settlement panel composed of trade experts to determine whether a country has violated WTO rules.108 In October, China requested the formation of a panel.109 Other WTO members have requested consultations with the United States, or joined existing requests, and panels have been composed to hear the cases (see Figure 6).

In its request, China alleged that the U.S. tariff measures and exemptions are contrary to U.S. obligations under several provisions of the GATT, the foundational WTO agreement that sets forth binding international rules on international trade in goods.110 In particular, China alleged that the measure violates GATT Article II, which generally prohibits members from imposing duties on imported goods in excess of upper limits to which they agreed in their Schedules of Concessions and Commitments.111 It further alleged that Commerce's granting of exemptions from the import tariffs to some WTO member countries, but not to China, violates GATT Article I, which obligates the United States to treat China's goods no less favorably than the goods of other WTO members (i.e., most-favored-nation treatment).112 China also maintained that the Section 232 tariff measures are "in substance" a safeguards measure intended to alleviate injury to a domestic industry from increased quantities of imported steel that competes with domestic steel, but that the United States did not make the proper findings and follow the proper procedures for imposing such a measure as required by the GATT and WTO Safeguards Agreement.113

|

|

Source: CRS based on WTO filings. |

The United States has invoked the so-called national security exception in GATT Article XXI in defense of the steel and aluminum tariffs. GATT Article XXI states, in relevant part, that the GATT114 will not

be construed . . . (b) to prevent any [member country] from taking any action which it considers necessary for the protection of its essential security interests

(i) relating to fissionable materials or the materials from which they are derived; (ii) relating to the traffic in arms, ammunition and implements of war and to such traffic in other goods and materials as is carried on directly or indirectly for the purpose of supplying a military establishment; [or]

(iii) taken in time of war or other emergency in international relations. . .

While some analysts argue that a WTO panel may evaluate whether a WTO member's use of the national security exception falls within one of the three provisions listed above, historically, the United States has taken the position that this exception is self-judging—or, in other words, once a WTO member has invoked the exception to justify a measure potentially inconsistent with its WTO obligations, a WTO panel may not proceed to the merits of the dispute and cannot evaluate whether the WTO member's use of the exception is proper.115 Though this exception has been invoked several times throughout the history of the WTO and its predecessor agreement, the GATT 1947, it has yet to be interpreted by a WTO dispute settlement panel.116 Accordingly, there is little guidance as to (1) whether a WTO panel would decide, as a threshold matter, that it had the authority to evaluate whether the United States' invocation of the exception was proper; and (2) how a panel might apply the national security exception, if invoked, in any dispute before the WTO involving the new steel and aluminum tariffs.117 In the past, however, WTO members have expressed concern that overuse of the exception will undermine the world trading system because countries might enact a multitude of protectionist measures under the guise of national security.118

If one of the WTO panels renders an adverse decision against the United States, the United States would be expected to remove the tariffs, generally within a reasonable period of time, or face the possibility of paying compensation to the complaining member or being subject to countermeasures allowed under the rules.119 Such countermeasures might include the complaining member imposing higher duties on imports of selected products from the United States.120 However, China has already begun imposing its own duties on selected U.S. exports without awaiting the outcome of a dispute settlement proceeding,121 perhaps because it often takes years before the WTO's Dispute Settlement Body authorizes a prevailing WTO member to retaliate.122

In turn, the United States has argued that unilateral imposition of tariffs in response to the U.S. Section 232 measures cannot be justified under WTO rules.123 On July 16, 2018, the United States filed its own WTO complaints over the retaliatory tariffs imposed by five countries (Canada, China, EU, Mexico, and Turkey) in response to U.S. actions, and in late August filed a similar case against Russia.124 Dispute settlement panels have been composed to hear these cases.

Additional Section 232 Investigations

Automobiles and Parts

As mentioned, subsequent to the steel and aluminum investigations, the Trump Administration initiated a third Section 232 investigation into the imports of automobiles, including SUVs, vans and light trucks, and automotive parts in May 2018. Commerce held a public hearing to inform the investigation and requested comments from stakeholders on the impact of these imports on national security, identifying a broad set of factors related to national defense and the national economy for consideration.125 As many foreign auto manufacturers have established facilities in the United States, Commerce specifically requested information on how the impact may differ when "U.S. production by majority U.S.-owned firms is considered separately from U.S. production by majority foreign-owned firms."

The value of U.S. imports potentially covered under the new investigation is significantly greater than that of steel and aluminum imports. With complex global supply chains, industry dynamics such as the existence of foreign-owned auto manufacturing facilities in the United States, and the potential for further retaliation by trading partners if tariffs are imposed as a result of the investigation, the economic consequences could be substantial.126 According to Ford Motor Co.'s executive vice president and president of global operations, Joe Hinrichs, "the auto industry is a global business. The benefits of scale and global reach are important ... The big companies that we compete against—Toyota, Volkswagen, General Motors, Nissan, Hyundai, Kia—are all global in nature because we realize the benefits of sharing the engineering, the platforms and scale, and our supply base."127

Some Members and auto industry representatives have spoken out in opposition to the new Section 232 investigation. The Driving American Jobs Coalition was created to oppose the potential tariffs and is comprised of a coalition of industry groups representing auto manufacturers, parts suppliers, auto dealers, parts distributors, retailers, and vehicle service providers.128 Others view the investigation as a tactical move by the Administration to pressure trade negotiating partners as the President continues to threaten auto tariffs.129 As mentioned, the EU has reportedly drafted a list of targets for retaliatory tariffs if the Administration moves forward with auto tariffs under Section 232.130 Three groups have voiced support for at least limited measures to address auto imports: the United Automobile Workers, the United Steelworkers, and the Forging Industry Association.131

Commerce submitted the final Section 232 report to the President on February 17, 2019, but the report has not been publicly released.132 Some Members have asked for the report to be made public, and the Cause of Action Institute sued Commerce to release the report after an unsuccessful Freedom of Information Act request.133 As noted earlier, the President has 90 days to review the report and make his determination as to whether he agrees or not with the Commerce findings and/or recommendation. In advance of the report's release, Senate Finance Chairman Grassley publicly reiterated his opposition to potential tariffs on auto or auto part imports, stating "I hope the president will heed my call to forgo the auto tariffs and focus on opening new markets.... In short, raising tariffs on cars and parts would be a huge tax on consumers who buy or service their cars, whether they are imported or domestically produced."134 Proposed legislation in the House and Senate would require a report by the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) on the economic importance of domestic automotive manufacturing before the President could act (S. 121, H.R. 1710).

Uranium

Unlike the self-initiated investigations into steel, aluminum, and auto imports, the Trump Administration opened two additional Section 232 investigations in response to industry petitions. In July 2018, Commerce launched a Section 232 investigation into uranium ore and product imports in response to a petition from two U.S. mining companies and after consulting with industry and government officials.135 The petitioners, the uranium-mining companies Energy Fuels and Ur-Energy, requested limiting imports to guarantee about 25% of the U.S. nuclear market for U.S. uranium producers, and "Buy American" provisions for government purchases of uranium to bolster the industry.136

Uranium mining is a relatively small-scale industry in the United States, accounting for 1.6% of global production of uranium from mines. At the end of 2017, Energy Fuels was the only remaining operator of a uranium mine in the United States. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) reports U.S. production at U.S. mines shrank to 1.2 million pounds, down 55% from 2016, and U.S. production in 2017 was at its lowest annual level since 2004. EIA also reports annual drops since 2013 in shipments, employment, and expenditures in the U.S. uranium production industry.137 Kazakhstan accounted for 39% of the world's production of uranium; Canada and Australia supplied roughly a third of the world's production in 2017.138 China made up 3.2% of worldwide uranium production in 2017.

The House Natural Resources Subcommittee questioned the need for the investigation and requested documentation from the petitioners regarding their communication with the Administration.139 The U.S. nuclear power industry opposes the investigation and claims that a uranium quota would lead to job losses in their industry.140

Titanium Sponge

In March 2019, Commerce launched another Section 232 investigation in response to a petition from a U.S. titanium firm.141 In explaining the investigation, the Commerce Secretary stated, "Titanium sponge has uses in a wide range of defense applications, from helicopter blades and tank armor to fighter jet airframes and engines."142

Titanium Metals Corporation (known as Timet) is currently the only producer of titanium sponge in the United States; USGS estimates that titanium sponge manufacturing employed 150 workers in 2018.143 In 2015, there were three such producers.144 For 2018, and the United States was 75% import reliant for titanium sponge.145 In 2018, Japan was the biggest supplier of titanium sponge, accounting for more than 90% of sponge imports; Kazakhstan was the second-leading supplier to the United States, making up 6.5% of imported titanium sponge.146 Although China was the world's largest producer of titanium sponge, producing 70,000 tons in 2018, it is not an important source of sponge imports for the United States.147 Any Section 232 tariff would be added to the existing 15% ad valorem tariff on titanium sponge imports.

Unlike steel and aluminum imports, which have multiple countervailing and antidumping duties in place, there are no such duties in place for uranium or titanium sponge imports; however, there is a suspended investigation into Russian uranium imports.148

Potential Economic Impact

The Section 232 tariffs affect various stakeholders in the U.S. economy, prompting reactions from several Members of Congress, some in support and others voicing concern. Congress has also held a number of hearings to examine the issue. For example, the tariffs and their effects on U.S. stakeholders were a focus of Members' questions during recent House Ways and Means and Senate Finance hearings on U.S. trade policy with USTR Robert Lighthizer.149 In general, the tariffs are expected to benefit domestic steel and aluminum producers by restricting imports, thereby putting upward pressure on U.S. steel and aluminum prices and expanding production in those sectors, while potentially negatively affecting consumers and downstream domestic industries (e.g., manufacturing and construction) due to higher costs of input materials. In addition, retaliatory tariffs by other countries raise the price of U.S. exports, potentially leading to fewer sales of U.S. products abroad, magnifying the possible negative impact of the Section 232 tariffs.

Economic studies of the tariffs estimate varying potential aggregate outcomes, but generally suggest an overall modest negative effect on the U.S. economy of the tariffs imposed to date, which could increase considerably if the Administration proceeds with Section 232 tariffs on U.S. motor vehicles and parts. U.S. motor vehicle and parts imports totaled $373.7 billion in 2018, nearly eight times the value of U.S. steel and aluminum imports ($47.1 billion) subject to Section 232 tariffs.150

Economic Dynamics of the Tariff Increase

Changes in tariffs affect economic activity directly by influencing the price of imported goods and indirectly through changes in exchange rates and real incomes. The extent of the price change and its impact on trade flows, employment, and production in the United States and abroad depend on resource constraints and how various economic actors (foreign producers of the goods subject to the tariffs, producers of domestic substitutes, producers in downstream industries, and consumers) respond as the effects of the increased tariffs reverberate throughout the economy. The following outcomes are generally expected at the level of individual firms and consumers:

- The price of the imported goods subject to the tariff is likely to increase. The magnitude of the price increase will depend on a number of factors, including the extent to which foreign producers lower their own prices and absorb a portion of the tariff increase. Known as the tariff "pass-through" rate, recent economic studies find that the tariffs have been nearly completely passed through to downstream industries and consumers with little effect on foreign export prices.151

Anecdotal reports suggest U.S. firms are paying increased prices for steel and aluminum purchased from abroad. For example, CP Industries, a maker of steel cylinders based in McKeesport, PA, is paying tariffs on imports of certain Chinese steel pipes it asserts cannot be produced in sufficient quantity in the United States to meet its demands.152 The company claims this raises the costs of its production by roughly 10%. The higher input costs potentially give foreign competitors an advantage in the U.S. market and abroad. - Demand for the imported goods facing the tariffs is likely to decrease, while demand for those goods produced domestically is likely to increase. Consumers and downstream firms' sensitivity to the price increase (their price elasticity of demand) will depend in large part on the degree to which the steel and aluminum products produced domestically are sufficient substitutes for the products facing the tariffs.

In 2018, the year the tariffs went into effect, U.S. imports of steel and aluminum subject to higher tariffs decreased by more than 10% in quantity terms, although both increased slightly in value terms (Figure 3). Annual domestic U.S. steel production meanwhile increased by 6% from 2017 to 2018,153 while primary U.S. aluminum production increased by 18% (January-November, latest data available).154 - The price and output of goods subject to the tariff produced domestically are likely to increase. As consumers of the products facing the tariffs shift their demand to lower- or zero-tariff substitutes, domestic producers are likely to respond with a combination of increased output and prices. Resource constraints that may limit or slow an expansion of output could cause prices to increase more rapidly. The low U.S. unemployment rate suggests such constraints may include frictions in shifting labor from other domestic industries into steel and aluminum production.155 In addition to reacting to higher-cost production and supply constraints, domestic steel and aluminum producers may also increase prices simply as a strategic response to the higher prices charged by their foreign competitors subject to the tariffs.156

In an anticipation of higher domestic demand and the ability to charge higher prices on U.S. steel and aluminum, some producers have announced investment and production increases. For example, U.S. Steel Corporation announced plans to increase capacity through a number of new or expanded facilities, including most recently a new furnace near Birmingham, AL.157 Similarly, three U.S. aluminum smelters are being restarted, including a Century Aluminum facility in Kentucky.158 Broad indices of U.S. steel and aluminum producer prices were up 14% and 5% between 2017 and 2018, respectively.159 - Input costs for downstream domestic producers are likely to increase. As prices likely rise in the United States for the goods subject to the tariffs, domestic industries that use steel and aluminum in their products ("downstream" industries, such as auto manufacturers and oil producers) face higher input costs. Higher input costs for downstream domestic producers are likely to lead to some combination of lower profits for producers and higher prices for consumers, which in turn could dampen demand for downstream products and result in a reduction of output in these sectors, and possibly employment declines. For example, Ford CEO James Hacket suggested the metal tariffs are expected to cost the auto manufacturer roughly $1 billion.160

- U.S. exports from the industries subject to retaliatory tariffs are likely to decline. Six U.S. trading partners (Canada, Mexico, EU, China, Turkey, and Russia) have imposed retaliatory tariffs in response to U.S. Section 232 tariffs affecting approximately $23 billion of U.S. exports in 2018, including many U.S. agricultural goods such as pork and dairy products. The retaliatory tariffs may have led to decreased demand for U.S. exports and given U.S. exporters an incentive to manufacture abroad to avoid the tariffs. For example, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture, Chinese tariffs on soybeans caused overall U.S. agricultural and food exports to China to decline in 2018, and China increased its purchases of soybeans from Brazil and elsewhere.161

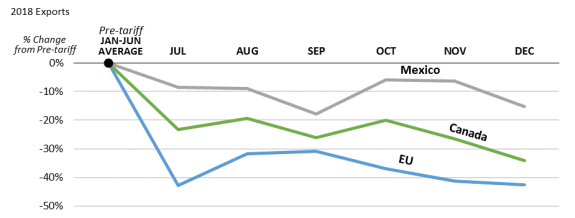

Canada, Mexico, and the EU account for 80% of U.S. exports subject to retaliatory tariffs in response to Section 232 actions. Since the retaliatory tariffs took effect, U.S. exports to these trading partners have decreased on average by 25%, 10%, and 38%, respectively. Facing retaliatory tariffs on U.S. motorcycle exports to the EU, Harley Davidson has announced its intent to shift some of its production out of the United States in order to remain competitive in the EU market.162

Aggregating these microeconomic effects, tariffs also have the potential to affect macroeconomic variables, although these impacts may be limited in the case of the Section 232 tariffs, given their focus on two specific commodities with potential exemptions, relative to the size of the U.S. economy. With regard to the value of the U.S. dollar, as demand for foreign goods potentially falls in response to the tariffs, U.S. demand for foreign currency may also fall, putting upward pressure on the relative exchange value of the dollar.163 This in turn would reduce demand for U.S. exports and increase demand for foreign imports, partly offsetting the effects of the tariffs. Tariffs may also affect national consumption patterns, depending on how the shift to higher-cost domestic substitutes affects consumers' discretionary income and therefore aggregate demand. Finally, given their ad hoc nature, these tariffs, in particular, are also likely to increase uncertainty in the U.S. business environment, potentially placing a drag on investment.

Assessing the Overall Economic Impact

From a global standpoint, tariff increases on steel and aluminum are likely to result in an unambiguous welfare loss due to what most economists consider is a misallocation of resources caused by shifting production from lower-cost to higher-cost producers. On the other hand, some see the Administration's trade actions as addressing long-standing issues of fairness that are intended to provide U.S. producers with a more level playing field. Looking solely at the domestic economy, the net welfare effect is unclear, but also likely negative. Generally, economic models would suggest the negative impact of higher prices on consumers and industries using the imported goods is likely to outweigh the benefit of higher profits and expanded production in the import-competing industry and the additional government revenue generated by the tariff. It is theoretically plausible to generate an overall positive welfare effect for the domestic economy if the foreign producers absorb a large enough portion of the tariff increase. Given the current excess capacity and intense price competition in the global steel and aluminum industries, however, this level of tariff absorption by foreign firms seems unlikely. Moreover, retaliation by foreign governments would erode this welfare gain.

The direct economic effects of the Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum may be limited due to the relatively small share of economic activity directly affected. In 2018, U.S. steel and aluminum imports were $29.5 billion and $17.6 billion, respectively, roughly 2% of all U.S. imports. Various stakeholder groups have prepared quantitative estimates of the costs and benefits across the economy. Specific estimates from these studies should be interpreted with caution given their sensitivity to modeling assumptions and techniques, but generally they suggest a small negative overall effect on U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) from the tariffs with employment shifts into the domestic steel and aluminum industries and away from other sectors in the economy.

|

Studies Examining the Economic Effects of Recent Tariff Actions The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the tariffs imposed by the Trump Administration to date (including Section 301 tariffs, which affect nearly five times the level of U.S. imports as Section 232 tariffs) will result in GDP declines of 0.1% annually.164 A study by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) comes to a largely similar conclusion, but further estimates that if the Administration goes forward with Section 232 tariffs on the auto industry and U.S. trade partners retaliate this negative effect could grow to approximately 0.6% annual GDP decline.165 A more recent academic study, which also accounts for increased U.S. government revenue resulting from the tariffs, estimates a slightly more modest negative aggregate welfare effect of $7.8 billion annually or 0.04% of GDP.166 For a more comprehensive listing of studies, see Table 2 in CRS Report R45529, Trump Administration Tariff Actions: Frequently Asked Questions, coordinated by Brock R. Williams. |

Issues for Congress

As Congress debates the Administration's Section 232 actions it may consider the following issues, many of which include potential legislative responses.

Appropriate Delegation of Constitutional Authority

In enacting Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, Congress delegated aspects of its authority to regulate international commerce to the executive branch. Use of the statute to restrict imports does not require any formal approval by Congress or an affirmative finding by an independent agency, such as the USITC, granting the President broad discretion in applying this authority. Should Congress disapprove of the President's use of the statute, its current recourse is limited to passing new legislation or using informal tools to pressure the Administration (e.g., putting holds on presidential nominee confirmations in the Senate). Some Members and observers have suggested that Congress should require additional steps in the Section 232 process. In the 116th Congress, a variety of proposals have been introduced to amend Section 232, in various ways, such as by

- requiring an economic impact study by the USITC, congressional consultation, or approval of any new tariffs,

- allowing for a resolution of disapproval of trade actions, or

- revisiting the delegation of its constitutional authority more broadly, such as by requiring congressional approval of executive branch trade actions more generally.

Some Members, including Senate Finance Chair Grassley, seek to draft a consensus bill to restore congressional authority that would gain sufficient bipartisan support to withstand a possible presidential veto. Issues under debate include whether any changes would be retroactive, potentially affecting the steel and aluminum tariffs, or whether they would only apply to future actions, and whether Congress's role should be consultative or decisive (e.g., requiring congressional approval). For a list of proposals in the 116th Congress, see Appendix C.

Legislative Responses to Retaliatory Tariffs

Several major U.S. trading partners have proposed or are currently imposing retaliatory tariffs in response to the U.S. actions. In the 115th Congress, some Members of Congress proposed legislation to respond to the potential economic impact of these foreign retaliatory tariffs. Some proposals expand programs like trade adjustment assistance to include assistance for workers, firms, and farmers harmed by foreign retaliation.167 Other measures propose increased funding and programming for certain agricultural export programs to help farmers find new markets for their exports.168 For a list of proposals from the 115th Congress, see Appendix C.

Establishing Threshold

It is relatively easy for a stakeholder to prompt the Section 232 investigation process. The statute states that "Upon request of the head of any department or agency, upon application of an interested party, or upon his own motion, the Secretary of Commerce ... shall immediately initiate an appropriate investigation." To limit the volume of Section 232 petitions and ensure that any requests are sufficiently justified, Congress may consider establishing criteria or a threshold that a request must meet before Commerce and Defense agencies invest resources in conducting a Section 232 investigation. Similarly, Congress may consider limiting the types of imported articles that may be considered under Section 232 (e.g., S. 287).

Interpreting National Security

Congress created the Section 232 process to try to ensure that U.S. imports do not cause undue harm to U.S. national security. Some observers have raised concerns that restrictions on U.S. imports under Section 232, however, may harm U.S. allies, which could also have negative implications for U.S. national security. For example, Canada is considered part of the U.S. defense industrial base according to U.S. law and is also a top source of U.S. imports of steel and aluminum.169

National security is not clearly defined in the statute, allowing for ambiguity and alternative interpretations by an Administration. International trade commitments both at the multilateral and FTA level generally include broad exceptions on the basis of national security. The Trump Administration argues its Section 232 actions are permissible under these exceptions, while many U.S. trading partners claim the actions are unrelated to national security. If the United States invokes the national security exemption in what may be perceived to be an arbitrary way, it could similarly encourage other countries to use national security as a rationale to enact protectionist measures and limit the scope of potential U.S. responses to such actions.