Overview of Recent Tariff Actions

What are tariffs and what are average U.S. tariff rates?

Tariffs or duties are taxes assessed on imports of foreign goods, paid by the importer to the U.S. government, and collected by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP).1 Current U.S. tariff rates may be found in the Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) maintained by the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC).2 The U.S. Constitution grants Congress the sole authority to regulate foreign commerce and therefore impose tariffs, but, through various trade laws, Congress has delegated authority to the President to modify tariffs and other trade restrictions under certain circumstances. To date, President Trump has proclaimed increased tariffs under three different authorities. The President has also proclaimed other import restrictions, including quotas and tariff-rate quotas under these authorities, but the majority of the actions are in the form of ad-valorem tariff increases.

|

Types of Import Restrictions

Tariff – A tax on imports of foreign goods paid by the importer. Ad valorem tariffs are assessed as a percentage of the value of the import (e.g., a tax of 25% on the value of an imported truck). Specific tariffs are assessed at a fixed rate based on the quantity of the import (e.g., 7.7¢ per kilogram of imported almonds), and are most common on agricultural imports.

Quota – A restriction on the total allowable amount of imports based either on the quantity or value of goods imported. Quotas are in place on a limited number of U.S. imports, mostly agricultural commodities, in part due to past trade agreements to remove and prohibit them.

Tariff-rate Quota (TRQ) – TRQs involve a two-tiered tariff scheme in which the tariff rate changes depending on the level of imports. Below a specific value or quantity of imports, a lower tariff rate applies, but once this threshold is reached all additional imports face a higher, sometimes prohibitive, tariff rate.

|

The United States played a prominent role in establishing the global trading system after World War II and has generally led and supported global efforts to reduce and eliminate tariffs since that time. Through both negotiated reciprocal trade agreements and unilateral action, countries around the world, including the United States, have reduced their tariff rates over the past several decades, some by considerable margins. According to the World Trade Organization (WTO), U.S. most-favored-nation (MFN) applied tariffs, the tariff rates the United States applies to members of the WTO—nearly all U.S. trading partners—averaged 3.4% in 2017.3 Globally tariff rates vary, but are also generally low. For example, the top five U.S. trading partners all have average tariff rates below 10%: the European Union (EU) (5.1%), China (9.8%), Canada (4.0%), Mexico (6.9%), and Japan (4.0%). Despite these low averages, most countries apply higher rates on a limited number of imports, often agricultural goods.4

What are the goals of the President's tariff actions and why are these actions of note?

As discussed below (see "What are Section 201, Section 232, and Section 301?") the authorities under which President Trump has increased tariffs on certain imports allow for import restrictions to address specific concerns. Namely, these authorities allow the President to take action to temporarily protect domestic industries from a surge in fairly traded imports (Section 201), to protect against threats to national security (Section 232), and to respond to unfair trade practices by U.S. trading partners (Section 301). In addition to addressing these specific concerns, the President also states he is using the tariffs to pressure affected countries into broader trade negotiations to reduce tariff and nontariff barriers, such as the announced trade agreement negotiations with the EU and Japan, and to lower the U.S. trade deficit.5

President Trump's recently imposed tariff increases are of note because

- they are significantly higher than average U.S. tariffs (most of the increases are in the range of 10-25%), and have resulted in retaliation of a similar magnitude by some of the countries whose exports to the United States have been subject to the tariff increases;

- they affect approximately 12% of annual U.S. imports and 8% of U.S. exports, magnitudes that could grow if additional proposed or pending actions are carried out, or decrease if additional negotiated solutions are achieved;

- they represent a significant shift from recent U.S. trade policy as no President has imposed tariffs under these authorities in nearly two decades; and

- they have potentially significant implications for U.S. economic activity, the U.S. role in the global trading system, and future U.S. trade negotiations.

What are Section 201, Section 232, and Section 301?

Section 201, Section 232, and Section 301 refer to U.S. trade laws that allow presidential action, based on agency investigations and other criteria. Each allows the President to restrict imports to address specific concerns. The focus of these laws generally is not to provide additional sources of revenue, but rather to alter trading patterns and address specific trade practices. The issues the laws seek to address are noted in italics below.

|

Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974

|

Allows the President to impose temporary duties and other trade measures if the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) determines a surge in imports is a substantial cause or threat of serious injury to a U.S. industry (19 U.S.C. §2251-2255).

|

|

Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962

|

Allows the President to take action to adjust imports if the U.S. Department of Commerce finds certain products imported into the United States in such quantities or under such circumstances as to threaten to impair U.S. national security (19 U.S.C. §1862).

|

|

Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974

|

Allows the United States Trade Representative (USTR), at the direction of the President, to suspend trade agreement concessions or impose import restrictions if it determines an act, policy, or practice of a foreign country violates, or is inconsistent with, the provisions of, or otherwise denies benefits to the United States under, any trade agreement or is unjustifiable and burdens or restricts U.S. commerce (19 U.S.C. §2411-2420).

|

What tariff actions has the Administration taken or proposed to date under these authorities?

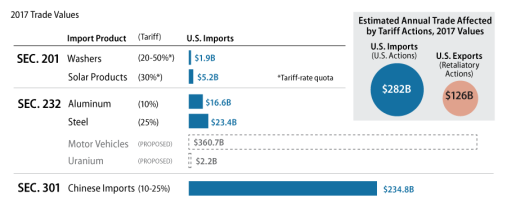

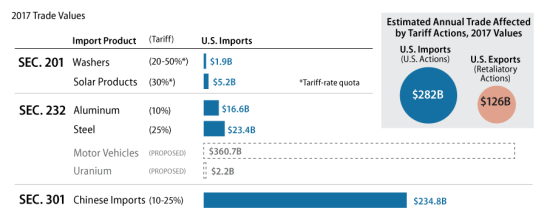

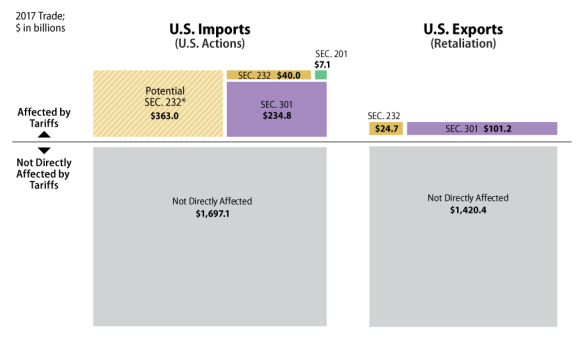

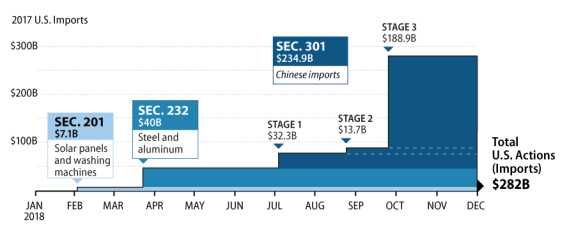

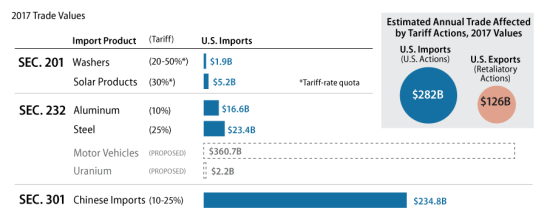

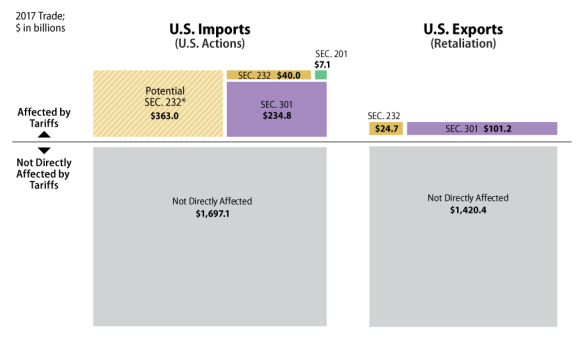

The Trump Administration has imposed import restrictions under the three authorities noted above, affecting approximately $282 billion in U.S. annual imports, based on 2017 import values (Figure 1). In addition, the President has initiated Section 232 investigations on U.S. imports of motor vehicles and uranium, which could result in increased tariffs on up to $361 billion and $2 billion of U.S. imports, respectively. The President has also suggested he may increase tariffs under Section 301 authorities on an additional $267 billion of U.S. imports from China, depending on the results of ongoing bilateral talks.

|

Figure 1. Trump Administration Tariff Actions and Affected Imports

|

|

|

|

Section 201 Safeguard Tariffs

(effective since February 7, 2018)

|

- Solar Cells: 4-year TRQ with 30% above quota tariffs, declining 5% annually. (All solar cell imports under the TRQ volume level will enter at the normal U.S. (duty-free) tariff rate).

- Solar Modules: 4-year TRQ with 30% tariffs, declining 5% annually.

- Large Residential Washers: 3-year TRQ, 20% in quota tariff, descending 2% annually; 50% above quota tariff, descending 5% annually.

- Large Residential Washer Parts: 3-year TRQ, 50% above quota tariff, descending 5% annually.

|

|

Section 232 National Security Tariffs

(effective since March 23, 2018)

|

- Aluminum: 10% tariffs on selected aluminum imports from most countries, effective indefinitely.

- Steel: 25% tariffs on selected steel imports from most countries, effective indefinitely; 50% tariffs on steel imports from Turkey.

- Additional investigations on motor vehicle and motor vehicle parts and uranium are ongoing and could result in additional import restrictions.

|

|

Section 301 "Unfair" Trading Practices Tariffs

(effective on U.S. imports from China since July 6, 2018)

|

- STAGE 1: 25% import tariff on 818 U.S. imported Chinese products (List 1), effective indefinitely from July 6, 2018.

- STAGE 2: 25% import tariff on 279 U.S. imported Chinese products (List 2), effective indefinitely from August 23, 2018.

- STAGE 3: 10% import tariff on 5,745 U.S. imported Chinese products (List 3), effective indefinitely from September 24, 2018, and currently scheduled to increase to 25% in March 2019.

|

|

Measuring U.S. and Retaliatory Tariff Actions

The scale and scope of the U.S. and retaliatory tariff actions can be measured in a number of ways. When referring to the value of trade potentially affected by the various tariff measures, this report, unless otherwise noted, uses an approximation based on annual import and export values from 2017, the last full year for which U.S. and partner country trade data are available. The tariffs became effective at different times during 2018, so annual figures of actual trade affected are not yet available. Data for U.S. imports come from the U.S. Census Bureau. Data for U.S. exports come from partner country import data, sourced through Global Trade Atlas IHS Markit. Partner country trade data are used to measure U.S. exports generally because product classifications may differ between countries, making it difficult to match U.S. trade values with the specific products subject to the tariff measures.

In announcing its tariff actions, the Administration specified the U.S. import values potentially affected. For example, the United States Trade Representative (USTR) described its three stages of Section 301 actions as affecting $34 billion, $16 billion, and $200 billion of annual U.S. imports, respectively, accounting for $250 billion of total U.S. imports affected by Section 301 actions. CRS estimates of the trade values are slightly lower than the Administration's announced figures, which may reflect use of 2017 trade values. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), similarly used 2017 trade values to estimate the shares of U.S. trade affected by the tariff actions and reported largely similar figures to the numbers reported in this publication.

|

Which countries are affected by the tariff increases?

The import restrictions imposed under Section 201 and Section 232 apply to U.S. imports from most countries. The Section 301 tariffs apply exclusively to U.S. imports from China.

|

Section 201

|

- Canada is excluded from the additional duties on residential washers.

- Certain developing countries are excluded if they account for less than 3% individually or 9% collectively of U.S. imports of solar cells or large residential washers, respectively.

- All other countries included.

|

|

Section 232

|

- Australia is excluded from the additional duties on both steel and aluminum due to negotiation of "satisfactory alternative means" to address the national security concerns, but unlike other exempted countries no quota is in place on U.S. imports from Australia.

- Argentina is excluded from the additional duties on aluminum due to a negotiated quota agreement.

- Argentina, Brazil and South Korea are excluded from the additional duties on steel but are instead subject to quota allotments based on negotiated agreements.6

- All other countries included.

|

|

Section 301

|

- Additional import duties apply only to U.S. imports from China.

|

Why is China a major focus of the Administration's action?

China is a major focus of a Section 301 investigation and related tariff measures largely due to concerns over its intellectual property rights (IPR) and forced technology transfer practices, and the size of its bilateral trade deficit with the United States. China's government policies on technology and IPR have been longstanding U.S. concerns and are cited by U.S. firms as among the most challenging issues they face in doing business in China.7 Moreover, China is considered to be the largest global source of IP theft. On March 22, 2018, President Trump signed a presidential memorandum on U.S. actions related to the Section 301 investigation. Described by the White House as a response to China's "economic aggression," the memorandum identified four broad Chinese IP-related policies to justify U.S. action under Section 301, stating

- China uses joint venture requirements, foreign investment restrictions, and administrative review and licensing processes to force or pressure technology transfers from American companies;

- China uses discriminatory licensing processes to transfer technologies from U.S. companies to Chinese companies;

- China directs and facilitates investments and acquisitions, which generate large-scale technology transfer; and

- China conducts and supports cyber intrusions into U.S. computer networks to gain access to valuable business information.8

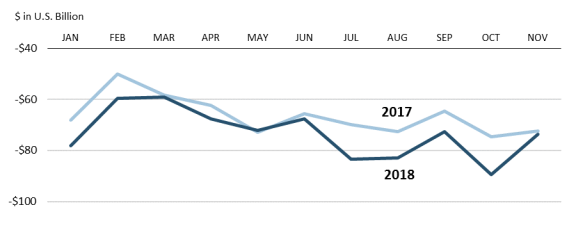

The USTR estimated that such policies cost the U.S. economy at least $50 billion annually.9 During his announcement of the Section 301 action, President Trump also stated that China should reduce the bilateral trade imbalance (which at $376 billion in 2017 for goods trade was the largest U.S. bilateral trade imbalance) and afford U.S. "reciprocal" tariff rates.10

Has the Administration engaged in negotiations with other countries with regard to these measures?

Yes. The Administration negotiated quota arrangements rather than imposing Section 232 tariffs on steel imports from Brazil and South Korea, and Section 232 tariffs on both steel and aluminum imports from Argentina. Although the steel and aluminum tariffs were not addressed in the proposed modifications to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), renamed the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), USTR Robert Lighthizer stated the three countries are discussing alternative measures.11 Side agreements to the USMCA include specific language exempting light trucks and 2.6 million passenger vehicle imports annually each from Canada and Mexico from future U.S. import restrictions under Section 232, as well as $32.4 billion and $108 billion of auto parts imports, respectively.12

The Administration also informally agreed not to move forward with additional Section 232 import duties on U.S. motor vehicle and parts imports from the European Union (EU) and Japan while broader bilateral trade negotiations are ongoing. Discussions on the steel and aluminum tariffs are also to be part of both negotiations.13

Additionally, the Administration has participated in talks with China regarding the trade practices that are the subject of the Section 301 tariffs. Negotiations in May 2018 initially appeared to resolve the trade conflict, but were ultimately unsuccessful.14 After further tariff actions by both sides, on December 1, 2018, Presidents Trump and Xi met at a private dinner during the G-20 Summit in Argentina. According to a White House statement, the two leaders agreed to begin negotiations immediately on "structural changes" with regard to IP and technology issues (related to the Section 301 case). The leaders also agreed to address agriculture and services issues. The parties set a goal of achieving an agreement in 90 days. In addition, the White House reported that President Xi agreed to make "very substantial" purchases of U.S. agricultural, energy, and industrial products. In exchange, President Trump agreed to suspend the planned Stage 3 Section 301 tariff rate increases that were scheduled to take effect on January 1, 2019, but stated that the increases would be implemented if no agreement was reached in 90 days (by March 1, 2019). High level talks continue, and on January 30-31, 2019, Chinese Vice Premier Liu met with President Trump and other U.S. officials, during which China pledged to purchase 5 million metric tons of U.S. soybeans.15 On January 31, President Trump indicated that a final resolution of the trade dispute would not be achieved until he met with President Xi.16 Reports suggest the trade talks may be extended beyond the March deadline.17

President Trump has made clear that the Administration is using these various import restrictions as a tool to get countries to negotiate on other issues. At the announcement of the proposed USMCA, the President stated "without tariffs, we wouldn't be talking about a deal, just for those babies out there that keep talking about tariffs. That includes Congress—'Oh, please don't charge tariffs.' Without tariffs, you wouldn't be standing here."18

The United States has also engaged or will engage in consultations at the WTO with some trading partners affected by the tariffs. Such consultations are a required first step in dispute settlement proceedings, which U.S. trading parties and the United States in turn, have initiated in response to the U.S. actions and trading partner retaliations. (See "What dispute-settlement actions have U.S. trading partners taken?" and "What dispute-settlement actions has the United States taken?")

Have U.S. trading partners taken or proposed retaliatory trade actions to date?

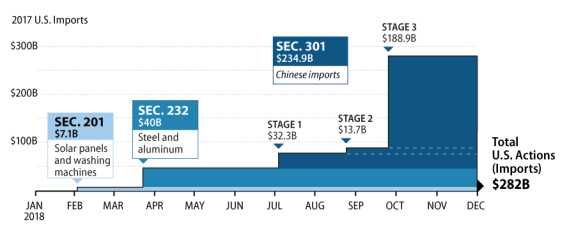

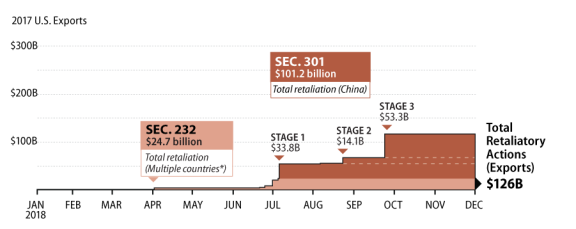

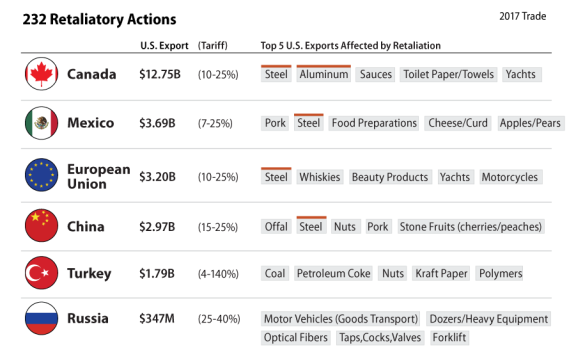

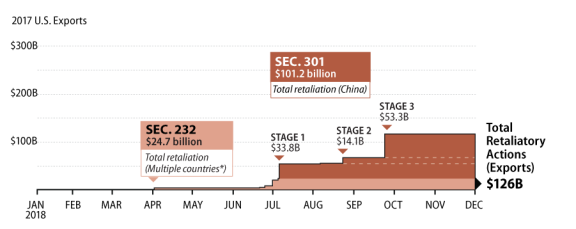

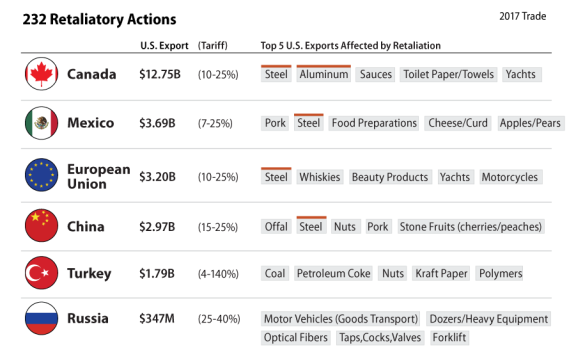

Yes. Some U.S. trading partners subject to the additional U.S. import restrictions have taken or announced proposed retaliations against each of the three U.S. actions. Since April 2018, a number of retaliatory tariffs have been imposed on U.S. goods accounting for $126 billion of U.S. annual exports, using 2017 export values (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2. Retaliatory Tariffs and Affected U.S. Exports

|

|

|

|

Section 201

|

- China and South Korea announced their intent to take retaliatory actions with regard to U.S. import restrictions on both solar products and washers.

- Japan announced its intent to retaliate with respect to the U.S. action on solar products.

- In line with WTO commitments on safeguards, the retaliatory actions are to take effect three years after the initial action, or in 2021.

|

|

Section 232

|

- Canada, China, the EU, Mexico, Russia and Turkey imposed retaliatory tariffs in response to the U.S. steel and aluminum tariffs.

- Japan and India notified proposed retaliation with the WTO but have not yet implemented retaliatory measures.

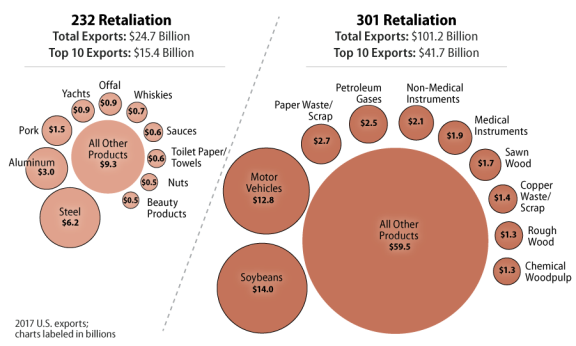

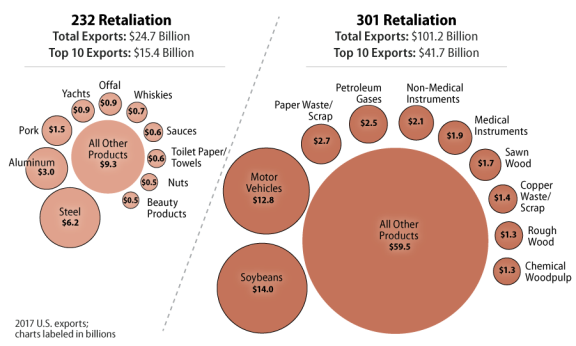

- Annual exports affected by the Section 232 retaliations total $25 billion, using 2017 export values.

|

|

Section 301

|

- China responded to each of the three U.S. lists of tariffs under Section 301 with its own retaliatory tariffs.

- Annual exports affected by Section 301 retaliations total $101 billion, using 2017 export values.

|

Has Congress responded to the Administration's tariff actions?

Yes. The tariffs impact various stakeholders in the U.S. economy, prompting both support and concern from different Members of Congress. To date, Congress has conducted oversight hearings on the Section 232 and 301 investigations and examined the potential economic and broader policy effects of the tariffs. Many Members have expressed concern over what they view as an expansive use of the delegated tariff authority under Section 232, and some Members have introduced legislation in the 115th and 116th Congresses that would amend the current authority in a number of ways, including requiring a greater congressional role before tariffs may be imposed. All actions continue to be actively debated, as some other Members see a need for expanded presidential authority to ensure more reciprocal tariff treatment by U.S. trading partners and have introduced legislation in the 116th Congress to that effect.19 Senator Grassley, chairman of the Senate Finance Committee announced that he intends to "review the President's use of power under Section 232 of the Trade Act of 1962" during the 116th Congress.20

Has the United States entered into a "trade war" and how does this compare to previous U.S. trade disputes?

There is no set definition of what may constitute a trade war. Beginning in 2017, the United States and some of its major trading partners imposed escalating import restrictions, particularly tariffs, on certain traded products. Some contend that with these actions—or threat thereof—the United States has embarked upon a full-scale "trade war."21 Although the scale and scope of these recent unilateral U.S. tariff increases are unprecedented in modern times, tensions in international trade relations are not uncommon. Over the last 100 years, the United States has been involved in a number of significant or "controversial" trade disputes.22 Past disputes, however, were more narrowly focused across products and trading partners, and generally temporary. Most were settled, and when unresolved, they were contained or defused through bilateral and multilateral negotiations. From the early 20th century until this year, one dispute resulted in a worldwide tit-for-tat escalation of tariffs: the trade dispute ignited by the U.S. Tariff Act of 1930, commonly known as the "Smoot-Hawley" Tariff Act.

The United States has imposed unilateral, restrictive trade measures in the past, but rarely before attempting to resolve its trade-related concerns through negotiations. The United States has, for the most part, engaged with trading partners in bilateral and multilateral fora to manage frictions over such issues and to achieve expanded market access for U.S. firms and farms and their workers. In particular, the United States has generally sought dispute resolution through the multilateral forum provided by the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and its successor, the WTO.23 As part of the dispute settlement process, WTO members may seek authorization to retaliate if trading partners maintain measures determined to be inconsistent with WTO rules.

When was the last time a President acted under these laws?24

Presidential action under these trade laws has varied since Congress enacted them in the 1960s and 1970s, but since 2002 past Presidents generally declined to impose trade restrictions under these laws. The use of Sections 201 and 301, which address some issues also covered by trade rules established at the WTO, has decreased since the creation of that institution in 1995 and its dispute-settlement system, considered more rigorous and effective than the dispute-settlement system under its predecessor, the GATT. The use of Section 232, which focuses on national security concerns and was created during the Cold War, has also declined and has been infrequently used over several decades.

|

Section 201

|

The ITC conducted 73 Section 201 investigations from 1975 to 2001. In 26 of those cases, the ITC determined imports were a threat to a domestic industry and the President decided to grant some form of relief. In 2002, based on a Section 201 case, President George W. Bush implemented a combination of quotas and tariff increases on various types of steel imports. The action was subsequently challenged in the WTO. In 2003, WTO panels determined that the safeguard action was inconsistent with the United States' WTO obligations, and on December 8, 2003, President Bush terminated the action. This was the last action taken under Section 201 prior to President Trump's import restrictions on solar products and washing machines.

|

|

Section 232

|

Prior to the Trump Administration, there were 26 Section 232 investigations resulting in nine affirmative findings by Commerce. In six of those cases, the President imposed a trade action. A President arguably last acted under Section 232 in 1986. In that case, Commerce determined that imports of metal-cutting and metal-forming machine tools threatened to impair national security. In this case, the President sought voluntary export restraint agreements with leading foreign exporters, and developed domestic programs to revitalize the U.S. industry.25 These agreements predate the founding of the WTO, which established multilateral rules prohibiting voluntary export restraints. The most recent Section 232 investigation prior to the Trump Administration took place in 2001 with regard to iron ore and finished steel, but it resulted in a negative finding by Commerce and no further action.

|

|

Section 301

|

From 1974 to 2016, the United States initiated 122 Section 301 cases, retaliating in 16 instances. During this period, the largest level of threatened U.S. Section 301 increased tariffs was $3.9 billion, which was against China in August 1992 over its extensive use of trade barriers on foreign imports (although an agreement was reached in October 1992).

The U.S. use of Section 301 fell considerably after the establishment of the WTO in 1995, which included a more effective and binding dispute settlement mechanism than existed under the GATT—a reform the U.S. actively sought and supported. U.S. implementation of the Uruguay Round agreements committed it to using the WTO dispute settlement process to resolve WTO-related issues with other WTO members. Some Section 301 investigations were initiated after 1995, but the issues involved were brought to the WTO. In October 2010, the USTR launched a Section 301 investigation into Chinese policies affecting trade and investment in green technologies (the last Section 301 case initiated until August 2017). The USTR stated that the issues raised were covered under the WTO agreements. It subsequently brought WTO dispute settlement cases against China over its wind power subsidies (December 2010) and its export restrictions on rare earth elements (March 2012).

|

Have the tariff measures resulted in legal challenges domestically or with regard to existing international commitments?

Yes. The President's actions have resulted in legal challenges in the U.S. domestic court system and in the dispute settlement system at the WTO. Specifically, the Section 232 actions on steel and aluminum have been challenged in cases before the U.S. Court of International Trade. Severstal Export Gmbh, a U.S. subsidiary of a Russian steel producer, has challenged whether the Administration's actions were appropriately based on national security considerations, as required by statute. The American Institute for International Steel (AIIS), a trade association opposed to tariffs, has challenged the constitutionality of Congress' delegation of authority to the President under Section 232.26 Most recently, U.S. importers of Turkish steel have initiated a case arguing that the President's increase of the Section 232 steel tariffs from 25% to 50% on U.S. imports from Turkey did not have a sufficient national security rationale, did not follow statutory procedural mandates, and violates a due process law.27 At the WTO, U.S. trading partners have initiated dispute settlement proceedings with regard to the President's actions under Section 201, Section 232, and Section 301. For more information, see the section on "What dispute-settlement actions have U.S. trading partners taken?"

Do these actions have broader economic and policy implications?

Many analysts are concerned that the U.S. measures threaten the rules-based global trading system that the United States helped to establish following World War II.28 The Trump Administration argues that the unilateral measures are justified under existing multilateral trade rules and as a response to violations of existing commitments under the WTO by other trading partners, particularly China. In contrast, U.S. trading partners contend that the Administration's unilateral actions undermine these existing commitments. They argue that the United States should make use of existing multilateral dispute settlement procedures to address concerns in the trading system rather than resorting to unilateral action. Supporters of the Administration's tariff actions argue that the tariffs and other import restrictions are a useful tool to protect domestic U.S. industries and incentivize U.S. trading partners to enter negotiations, in which they would otherwise have little interest in engaging.29 Some, including the Administration, also argue that the Section 301 actions address issues not adequately covered by existing WTO rules.

Some observers also raise concerns over the scale of the Administration's actions, which have led to import restrictions imposed on nearly all U.S. trading partners, including some close allies such as Canada, Japan, Mexico, South Korea, and the EU. These groups agree with the U.S. concerns over specific trade practices by China, but support a more targeted approach that includes cooperation between the United States and other countries that share U.S. concerns over violations to and shortcomings of the existing international trading system.30 While the United States is involved in multilateral discussions at various levels on potential reforms to the global trading system, specifically the WTO, some analysts argue ongoing tension resulting from the U.S. unilateral actions could hamper these efforts.31

The complex nature of international commerce, including its highly integrated global supply chains, makes difficult the accurate prediction of the effects of broad tariff actions on specific industrial sectors or individual companies. For example, the Administration imposed Section 201 safeguard tariffs on washing machines to support domestic manufacturers of washing machines, but these same domestic manufacturers now argue that subsequent Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum have led to increases in their input costs and caused further economic harm.32 U.S. domestic auto production, which the Trump Administration may seek to encourage through additional Section 232 tariffs now under investigation, is similarly negatively affected by the existing steel and aluminum tariffs. Retaliation in the form of increased tariffs on U.S. exports further complicates the economic outcome of the unilateral U.S. actions. Many companies also report that uncertainty resulting from the unpredictable nature of the U.S. and retaliatory actions has made long-term planning difficult; this may be putting a drag on U.S. and global economic activity. Others, including some domestic producers, argue that action was needed to prevent more injurious trade practices from occurring and to eventually achieve broader agreement on reducing tariff barriers and establishing new trading rules.

Is further escalation and retaliation possible?

Yes. Two pending Section 232 investigations on U.S. motor vehicle and parts imports and uranium are underway, which could lead to future import restrictions. Additionally, the scheduled increase in the tariff rate on the third tranche of Section 301 tariffs on U.S. imports from China could occur in the near future, as well as potential new tariffs on additional U.S. imports from China, absent a trade agreement to resolve the core issues that are the subject of current bilateral trade discussions.

U.S. motor vehicle and parts imports totaled $361 billion in 2017, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. These goods are among the top U.S. imports supplied by a number of U.S. trading partners, including Canada, Mexico, Japan, South Korea, and the EU, making an increase in U.S. tariffs that applies to these countries economically significant and likely to result in retaliatory action. Canada and Mexico are currently exempt from future auto 232 tariffs for a limited amount of imports under the proposed USMCA agreement. With respect to the EU and Japan, the Administration has notified Congress of its intent to negotiate bilateral trade agreements and informally agreed to refrain from imposing new auto tariffs while those talks progress. South Korea is the only major U.S. auto supplier without a formal or informal assurance from the Trump Administration that it will be exempt from Section 232 auto tariffs, despite recently implemented modifications to the U.S.-South Korea (KORUS) free trade agreement (FTA). A delay in ratification and implementation of the proposed USMCA, or a breakdown in talks with the EU and Japan could make an escalation on this front more likely.

As noted, President Trump has warned that he will follow through with his threat to increase Section 301 tariffs on $200 billion worth of products from China from 10% to 25% if a trade agreement is not reached by March 1, 2019, or potentially soon thereafter. He has also threatened increased tariffs on an additional $267 billion worth of imported Chinese products. China imports far less from the United States than it exports and therefore could not match U.S. tariffs on a comparable level of U.S. products, but it could increase the level of the tariffs on products that have already been impacted by retaliatory Section 301 tariffs, in addition to raising tariffs on U.S. products that have not yet been subject to retaliatory tariffs. Further, the Chinese government could take other retaliatory action, calling on its citizens to boycott the purchase of American goods and services in China, curtailing the operations of U.S. manufacturing firms in China, ordering Chinese firms to halt purchases of certain high-value U.S. products (e.g., Boeing aircraft) or restricting its citizens from traveling to, or investing in, the United States.33 The Chinese government could also choose to halt purchases of U.S. Treasury securities and possibly sell off some of its holdings.34

Scale and Scope of U.S. and Retaliatory Tariffs

What U.S. imports are included in the tariff actions?

The Administration has imposed tariffs on U.S. goods accounting for $282 billion of U.S. annual imports, using 2017 trade values. Section 301 actions currently account for the greatest share (83%) of affected imports. U.S. annual imports of products covered under the Section 301 actions currently total $235 billion, compared with $40 billion (14%) under Section 232, and $7 billion (3%) under Section 201 (Figure 3). The potential Section 232 actions on motor vehicles and uranium could cover an additional $361 billion and $2 billion, respectively in U.S. imports, depending on the countries and products included.

|

Figure 3. U.S. Imports Affected by Trump Administration Tariff Actions

|

|

|

Source: CRS analysis with data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

|

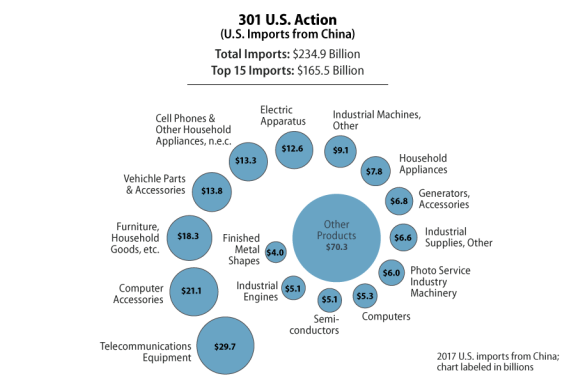

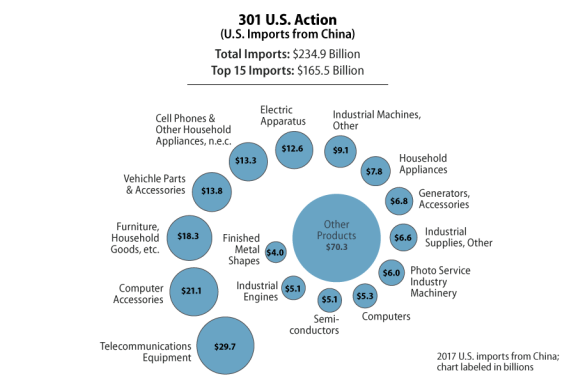

The scope of U.S. imports affected vary across the three different actions. Section 201 actions cover U.S. imports of washers, washing machine parts, and solar cells and modules. Section 232 actions cover U.S. imports of steel and aluminum products. Section 301 actions cover a broad range of U.S. imports from China. To date, the Administration has imposed increased tariffs under Section 301 on nearly 7,000 products at the 8-digit harmonized tariff schedule (HTS) level.35 Figure 4 below lists the top 15 products subject to the Section 301 import tariffs classified according to 5-digit U.S. end-use import codes. The major categories are telecommunications equipment, computer accessories, furniture, and vehicle parts.

|

Figure 4. U.S. Imports Affected by Section 301 Actions by Product

|

|

|

Source: CRS analysis with import data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Note: Product categories based on 5-digit U.S. end-use import codes.

|

What U.S. exports face retaliatory tariff measures?

To date, U.S. trading partners have retaliated against U.S. Section 232 and Section 301 actions. China, Japan, and South Korea have also announced planned retaliation to U.S. Section 201 actions, but in line with WTO commitments on safeguard retaliations, they are not to be imposed until 2021. The total actions to date affect approximately $126 billion of annual U.S. exports, using 2017 trade values.

The retaliations against U.S. Section 232 actions affect U.S. exports to six trade partners: Canada, Mexico, the EU, China, Turkey, and Russia. The retaliation is similar to the U.S. actions both in terms of the tariff rates (most are in the range of 10%-25%) and the products covered (steel or aluminum are among the top products targeted). Other major products targeted include food preparations and agricultural products, yachts, motorcycles, whiskies, and some heavy machinery (Figure 5). In total, approximately $25 billion of U.S. annual exports are potentially affected by trade partner retaliations against the U.S. Section 232 actions.

|

Figure 5. Section 232 Retaliation by Country

|

|

|

Source: CRS analysis based on partner country import data sourced through Global Trade Atlas IHS Markit.

Notes: U.S. exports of specific products subject to retaliatory tariffs approximated by using partner country import data. U.S. Section 232 actions target steel and aluminum imports, and steel and aluminum are among the top products facing retaliation by several U.S. trading partners as highlighted above.

|

Retaliatory tariffs imposed by China in response to U.S. Section 301 actions affect approximately $101 billion of U.S. annual exports, accounting for about 80% of U.S. exports subject to retaliatory tariffs currently in effect (Figure 6). Like the retaliation in response to U.S. Section 232 actions, agricultural products are a main target. Soybeans, which accounted for $14 billion of U.S. exports to China in 2017, are the top overall export affected. Motor vehicles were the second-largest category of exports under the Section 301 retaliation, but these retaliatory tariffs have been temporarily suspended as part of the recent efforts at bilateral U.S.-China negotiations to resolve the trade conflict.36 The Chinese retaliatory tariffs, like the U.S. Section 301 tariffs, range from 10%-25% and cover thousands of tariff lines.

|

Figure 6. U.S. Exports Affected by Retaliatory Tariffs

|

|

|

Source: CRS analysis with partner country trade data sourced from Global Trade Atlas IHS Markit.

Notes: U.S. exports based on partner country import data, and categorized by 4-digit HS product classifications for all products except steel and aluminum, which are based on 2-digit HS classifications. China temporarily suspended its 25% retaliatory tariffs on motor vehicles on January 1, 2019, effective until April 1, 2019.

|

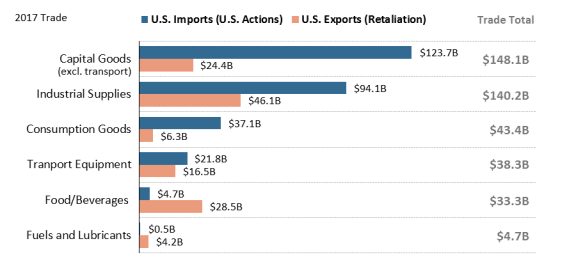

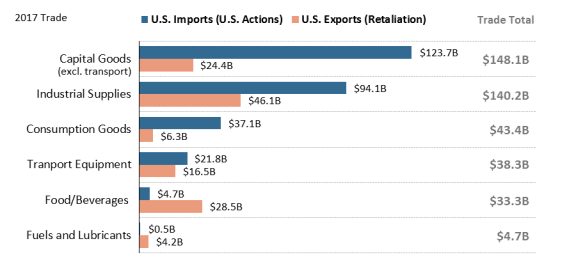

How do the U.S. tariff actions and subsequent retaliation compare?

U.S. and retaliatory tariffs differ in both scale and scope of products covered. The United States has placed increased tariffs on products accounting for approximately $282 billion of annual U.S. imports, while retaliatory tariffs cover approximately $126 billion of annual U.S. exports, using 2017 trade values. China, which is subject to the largest share of new U.S. tariffs and has imposed the largest share of new retaliatory tariffs, imports far less from the United States than the United States imports from China, limiting the amount of retaliatory tariffs China can impose on U.S. exports. (See discussion on "Is further escalation and retaliation possible?")

In terms of the products covered, the largest categories of U.S. imports affected by the tariffs are capital goods and industrial supplies (Figure 7). This suggests that, to date, U.S. tariffs are concentrated on products primarily used as inputs in the production of other goods rather than on final consumption goods; therefore the effects of the tariffs may be most pronounced in increased costs for U.S. producers. Among U.S. exports, food and beverages is the second-largest category of goods facing retaliatory tariffs, suggesting that U.S. agriculture producers are among the groups most negatively affected by the retaliatory actions.

|

Figure 7. U.S. Trade Affected by Increased Tariffs by Product Category

|

|

|

Sources: CRS analysis based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau and Global Trade Atlas IHS Markit.

Notes: U.S. exports based on partner country import data. Product category classification is based on 3-digit Broad Economic Categories (BEC).

|

What share of annual U.S. trade is affected or potentially affected by the U.S. and retaliatory actions?

As a share of overall U.S. trade, approximately 12% of annual U.S. goods imports ($282 billion of $2,342 billion total imports) are subject to increased U.S. tariffs under the Trump Administration's actions (Figure 8). Approximately 8% of annual U.S. goods exports ($126 billion of $1,546 billion total exports) are subject to increased tariffs under partner country retaliatory actions. If the United States moves forward with additional tariffs under the two pending Section 232 investigations on U.S. imports of motor vehicles/parts and uranium, the share of affected U.S. imports could increase up to nearly 30%. U.S. motor vehicle and parts imports totaled $361 billion in 2017.37

|

Figure 8. Shares of U.S. Goods Trade Affected by Tariff Actions

|

|

|

Source: CRS analysis with data from the U.S. Census Bureau and partner country.

Note: (*) Potential 232 action includes pending U.S. investigations on motor vehicles/parts and uranium imports and may include some overlapping coverage with existing 301 tariffs.

|

What factors affect the products selected for retaliation?

A variety of factors likely go into a country's decision regarding which products to target for retaliation. Retaliatory tariffs are explicitly targeted to encourage the United States to remove its Section 232 and Section 301 tariffs, whereas the Trump Administration's enacted and proposed tariffs aim both to alter U.S. trading partners' practices more broadly, including reducing existing tariff and nontariff barriers, and to protect domestic industries. Retaliatory tariffs can have negative effects on both the exporting country (the United States) and the importing country imposing the retaliation. Therefore, retaliating countries are likely to target products that create the most pressure on the United States to change its policy while minimizing any negative effects on themselves. Some factors that may create greater pressure for U.S. policy change include (1) demand for the targeted product is price sensitive (i.e., demand is price elastic), therefore a small tariff increase will lead to a sharper decline in exports; (2) the retaliating country is a major world market for the product, in which case the exports may not be easily diverted to other markets; and (3) the producers of the targeted products in the United States (i.e., those negatively affected by the tariffs) have high levels of political influence (e.g., the product is made in congressional districts with Members on key committees).

Factors that would decrease the negative effects on the importer (retaliating country) include (1) other countries competitively produce the product allowing for alternate sourcing; and (2) importers can easily substitute a different product for the targeted import (e.g., substituting wheat for corn for animal feed).38 Retaliating countries might also seek to impose similar tariffs as those against which they are retaliating (e.g., steel and aluminum are the top products subject to retaliation in response to the Administration's Section 232 steel and aluminum tariffs).39 Retaliating countries may also seek to lessen the negative impacts of the tariffs on certain segments of the population (e.g., a country might target luxury goods consumed by higher income groups rather than basic food and apparel products that account for a larger share of low-income household consumption).

Once the President imposes tariffs, can the President change them?

Yes. The President has the authority to reduce, modify, or terminate import restrictions imposed under Sections 201, 232, and 301. Certain limitations on the President's authority to modify the tariffs apply as specified in the relevant statutes.40 The President has adjusted several tariff increases since they were initially proclaimed. For example, the President increased the tariff on U.S. steel imports from Turkey under Section 232 from 25% to 50%.41 However, certain U.S. importers of Turkish steel have brought a challenge to this tariff increase at the U.S. Court of International Trade. Similarly, the President has modified actions taken under Section 301 by increasing the scope of imports from China that are subject to new tariffs.42 Some products have also received exemptions from the tariff measures, explained below.

What exemptions are allowed from the tariffs imposed to date?

Section 201

In Presidential Proclamation 9693, announcing the Section 201 action on solar products, the President gave the USTR 30 days to develop procedures for exclusion of particular products from the safeguard measure.43 On February 14, 2018, the USTR published a notice establishing procedures to consider requests for the exclusion of particular products.44 Based on that notice, the USTR received 48 product exclusion requests and 213 subsequent comments responding to these requests by the deadline, March 16, 2018. On September 19, 2018, the USTR announced a limited number of solar product exclusions, and indicated that additional requests received by the March 16, 2018 deadline remained under evaluation.45

Canada is excluded from the additional duties on washers.46 Certain developing countries were excluded, provided that they account for less than 3% individually or 9% collectively of U.S. imports of solar cells or large residential washers, respectively. All other countries are covered by the Section 201 trade actions.

Section 232

Individual countries and products may be exempted from the Section 232 tariffs.

Country Exemptions

According to the initial presidential proclamation, countries with which the United States has a "security relationship" may discuss "alternative ways" to address the national security threat posed by imports of steel and aluminum and gain an exemption from the tariffs. To date four countries have reached agreements with the United States exempting them from part or all of the Section 232 tariffs:

- 1. South Korea agreed to an absolute annual quota for 54 separate subcategories of steel in place of the steel tariffs.47 South Korea did not negotiate an agreement on aluminum and has been subject to the aluminum tariffs since May 1, 2018.

- 2. Brazil was permanently exempted from the steel tariffs, having reached final quota agreements with the United States on steel imports.48 Brazil, like South Korea, did not negotiate an agreement on aluminum and has been subject to the aluminum tariffs since June 1, 2018.

- 3. Argentina was permanently exempted from the steel and aluminum tariffs and agreed to absolute quotas for each.49

- 4. Australia gained a permanent exemption from the tariffs without any quantitative restrictions.

Product Exclusions

The 232 product exclusion process is administered by the Department of Commerce's Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS). Thousands of requests have been filed to date and the exclusion process has been the subject of criticism and scrutiny by several Members of Congress and other affected stakeholders. To limit potential negative domestic impacts of the tariffs on U.S. consumers and consuming industries, Commerce published an interim final rule for how parties located in the United States may request exclusions for items that are not "produced in the United States in a sufficient and reasonably available amount or of a satisfactory quality."50 The rule went into effect the same day as publication to allow for immediate submissions.

Requesters must complete the official response form spreadsheets for each steel and aluminum exclusion and submit the forms on regulations.gov, where both requests for exclusions and objections to requests are posted.51 There is no time limit for submitting an exclusion request. Each requester must complete a separate application for each product to be considered for exclusion. Exclusion determinations are to be based on national security considerations, but the specific nature of these considerations remain undefined. To minimize the impact of any exclusion, the interim rule allows only "individuals or organizations using steel articles ... in business activities ... in the United States to submit exclusion requests," eliminating the ability of larger umbrella groups or trade associations to submit petitions on behalf of member companies. A parallel requirement applies for aluminum requests. Any approved product exclusion will be limited to the individual or organization that submitted the specific exclusion request. Parties may also submit objections to any exclusion within 30 days after the exclusion request is posted. The review of exclusion requests and objections will not exceed 90 days. Exclusions will generally last for one year.

Companies and some Members of Congress have criticized the intensive, time-consuming process to submit exclusion requests, the lengthy waiting period for a response from Commerce, what some view as an arbitrary nature of acceptances and denials, and the fact that all exclusion requests to date have been rejected when a U.S. steel or aluminum producer has objected to it.52 (See "Have Members of Congress and other stakeholders raised issues regarding the product exclusion process?") In response, Commerce announced a new rule to allow companies to rebut objections to petitions. The new rule, published September 11, 2018, includes new rebuttal mechanisms, more information about the exclusion submission requirements and process, and the criteria Commerce uses in deciding whether to grant an exclusion request.

In September, Commerce provided revised estimates of the anticipated number of exclusion requests (96,954) and objections (38,781).53 To streamline and increase the transparency of the process, Commerce developed an online portal for users to submit requests for exclusions, objections, rebuttals, or surrebuttals. Commerce began testing the portal in December 2018 with the goal of implementing it in early 2019.54

Section 301

During the Section 301 notice and comment period on proposed Section 301 tariff increases, the USTR heard from a number of U.S. stakeholders who expressed opposition and/or concern about how such measures could impact their businesses, as well as U.S. consumers. In response, the USTR created a product exclusion process, whereby firms could petition for an exemption from the Section 301 tariff increases for specific imports. The USTR stated that product exclusion determinations would be made on a case-by-case basis, based on information provided by requesters that showed

- Whether the particular product is available only from China;

- Whether the imposition of additional duties on the particular product would cause severe economic harm to the requester or other U.S. interests; and

- Whether the particular product is strategically important or related to ''Made in China 2025'' or other Chinese industrial programs.55

To date, USTR has only created this product exclusion process for the first two stages of tariff increases under Section 301. Several Members of Congress have sent letters to the USTR calling for an exclusion process for stage three tariffs as well. The joint explanatory statement to the FY2019 appropriations law (P.L. 116-6), enacted February 15, 2019, directs USTR to establish a product exclusion process for stage three tariffs within 30 days.56

How many product exclusion requests have been made?57

|

Section 201

|

The USTR received 48 product exclusion requests and 213 subsequent comments responding to these requests by the deadline, March 16, 2018. Product exclusions were granted for a limited number of solar products.

|

|

Section 232

|

The Department of Commerce notes that as of August 20, 2018, more than 38,000 exclusion requests and 17,000 objections to those requests had been received. More recent analysis by third parties suggest that as of November 5, 2018, 49,000 requests had been submitted with 12,276 granted, 5,073 denied, and 7,776 returned for re-submission, and as of December 20, 2018, interested parties had submitted 44,389 exclusion requests for steel and 6,013 for aluminum, and 15,509 objections had been filed (15,047 for steel and 462 for aluminum).

|

|

Section 301

|

Requests to the USTR for Stage 1 and Stage 2 exclusions were due by October 9, 2018, and December 18, 2018, respectively. According to the USTR, through January 30, 2019, there were 13,739 stage 1 and stage 2 tariff exclusion requests, of which 985 exclusions were granted and 2,499 requests denied. Requests not granted or denied remain under review.

|

Have Members of Congress and other stakeholders raised issues regarding the product exclusion process?

Several Members of Congress have raised concerns about the Section 232 exclusion process. For example, in a letter to Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, and at a June 2018 hearing, then-Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch and Ranking Member Ron Wyden urged improvements to the product exclusion procedures on the basis that the detailed data required placed an undue burden on petitioners and objectors. They also suggested that the process appeared to bar small businesses from relying on trade associations to consolidate data and make submissions on behalf of multiple businesses. The letter further stated that Commerce had not instituted a clear process for protecting business proprietary information.58 In a follow-up letter to the Secretary of Commerce in December, Senators Hatch and Wyden recognized that some improvements had been made to the exclusion process but identified further issues raised by stakeholders and U.S. businesses. They asked Commerce to address the concerns by adhering to the published timelines for reviewing requests and making specific changes to how the agency handles requests with technical defects.59

Some Members have used multiple channels to continue to raise issues. A bipartisan group of House Members articulated concerns about the speed of the review process and the significant burden it places on manufacturers, especially small businesses.60 The Members' letter included specific recommendations, such as allowing for broader product ranges to be included in a single request, allowing trade associations to petition, grandfathering existing contracts to avoid disruptions, and regularly reviewing the tariffs' effects and sunsetting them if they have a "significant negative impact."61 In September 2018, during an oversight hearing, multiple Senators raised concerns directly to the Assistant Secretary for Export Administration, Bureau of Industry and Security at Commerce, about agency management of the Section 232 exclusion process, including staffing and funding levels, and the need for greater transparency, among other issues.62

Some Members have questioned the Administration's processes and ability to pick winners and losers through granting or denying exclusion requests. On August 9, 2018, Senator Ron Johnson requested that Commerce provide specific statistics and information on the exclusion requests and process and provide a briefing to the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. Senator Elizabeth Warren requested that the Commerce Inspector General investigate the implementation of the exclusion process, including a review of the processes and procedures Commerce has established, how they are being followed, and if exclusion decisions are made on a transparent, individual basis, free from political interference. She also requested evidence that the exclusions granted meet Commerce's stated goal of "protecting national security while also minimizing undue impact on downstream American industries," as well as evidence that the exclusions granted to date strengthen the national security of the United States.63 In response to a formal request by Senators Pat Toomey and Tom Carper, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) announced on December 12, 2018, it will investigate the Section 232 product exclusion process in early 2019.64 Congress authorized additional funds for the Section 232 product exclusion process in the FY2019 appropriations law (P.L. 116-6), and in the accompanying joint explanatory statement, stipulated that Commerce provide quarterly reports to Congress on its administration of the process.65

The Section 301 exclusion process managed by USTR and effective for the first two tranches of Section 301 tariffs has not attracted the same level of attention from Congress as the Section 232 exclusion process. A bipartisan group of more than 160 Representatives, however, have urged the Administration to allow product exclusions on the third and largest tranche of Section 301 tariffs, and the joint explanatory statement to P.L. 116-6, directs USTR to establish such an exclusion process within 30 days of the law's enactment.66

Economic Implications of Tariff Actions

What are the general economic dynamics of a tariff increase and who are the economic stakeholders potentially affected?

Changes in tariffs affect economic activity directly by influencing the price of imported goods and indirectly through changes in exchange rates and real incomes. The extent of the price change and its impact on trade flows, employment, and production in the United States and abroad depend on resource constraints and how various economic actors (foreign producers of the goods subject to the tariffs, producers of domestic substitutes, producers in downstream industries, and consumers) respond as the effects of the increased tariffs reverberate throughout the economy. Retaliatory tariffs, which U.S. trading partners have imposed in response to U.S. Section 232 and Section 301 tariffs, also affect U.S. exporters. The following outcomes (summarized in Table 1) are generally expected at the level of individual firms and consumers:

|

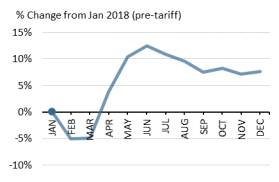

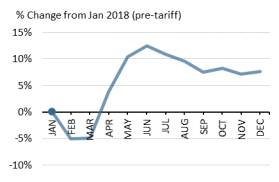

Figure 9. U.S. Washing Machine Prices

|

|

|

Source: CRS analysis based on U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data.

Note: Consumer price index series id CUUR0000SS30021 covers "laundry equipment."

|

- U.S. consumers: Higher tariff rates generally lead to price increases for consumers of the goods subject to the tariffs and for consumers of downstream products as input costs rise. Higher prices in turn lead to decreased consumption depending on consumers' price sensitivity for a particular product.67 As one example, the monthly price of washing machines in the United States, which are currently subject to tariff increases under Section 201, has increased by as much as 12% compared to January 2018 before the tariffs became effective (Figure 9).

- U.S. producers of domestic substitutes: U.S. producers competing with the imported goods subject to the tariffs (e.g., domestic steel and aluminum producers) may benefit to the degree they are able to charge higher prices for their domestic goods. However, in the short run, U.S. producers' ability to increase production may be limited. A broad index of U.S. steel producer prices was up 14% in December relative to March, when the Section 232 tariffs first took effect.68 A similar price indicator for aluminum refining and primary aluminum production shows more volatile prices, with the index down 6.2% between March 2018 and December 2018.69

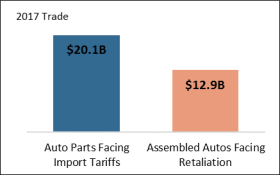

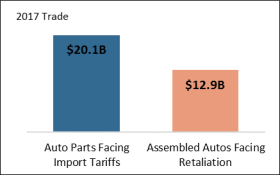

- U.S. producers in downstream industries: U.S. producers using goods subject to the additional tariffs as inputs may be harmed because the tariffs may cause their costs to increase. U.S. motor vehicle producers may be among the industries most hurt since they face: (1) higher input costs for steel; (2) tariffs on parts accounting for $20 billion of annual imports; and (3) retaliatory tariffs on assembled motor vehicle exports to China accounting for $13 billion of annual exports (Figure 10).70

|

Figure 10. Motor Vehicle Trade and Tariffs

|

|

|

Sources: CRS analysis using data from the U.S. Census Bureau and Global Trade Atlas IHS Markit.

Notes: Includes all U.S. tariff actions and retaliatory tariffs. Based on 5-digit end use categories. China temporarily suspended its 25% retaliatory tariffs on motor vehicles on January 1, 2019, effective until April 1, 2019.

|

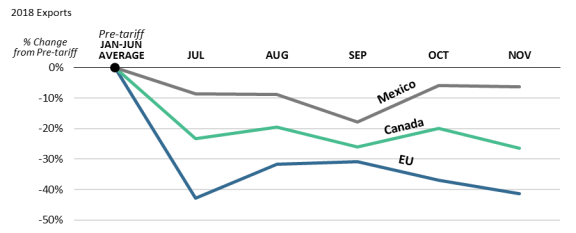

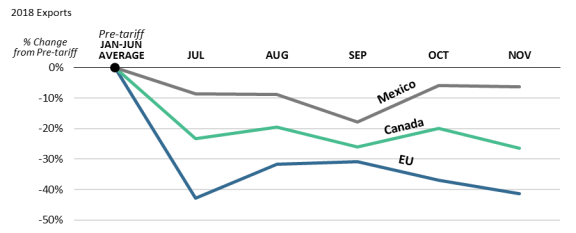

- U.S. exporters subject to retaliatory tariffs: U.S. exporters facing retaliatory tariffs may be at a price disadvantage in export markets relative to competitors from other countries, which may decrease demand for U.S. exports to those markets. Since Section 232 retaliatory tariffs took effect in the EU, Canada, and Mexico in July, U.S. average monthly exports of the products subject to retaliation have been below their pre-tariff monthly 2018 average by 37%, 23%, and 10%, respectively (Figure 11). China purchases such a large share of certain U.S. agricultural exports—China accounted for 57% of all U.S. soybean exports in 2017—its retaliatory tariffs and the subsequent decline in export sales may have contributed to depressed U.S. prices for some commodities.71

- Foreign producers of the goods subject to the tariffs: Foreign producers can also be affected by tariff increases if consumer demand falls in response to rising prices. In some instances, typically when demand is very price sensitive, or highly elastic, foreign producers may choose to lower their prices and absorb a portion of the tariff increase. The degree to which foreign producers change their prices in response to tariff changes is known as the tariff pass-through rate.72 Over a longer time horizon, production may shift to other countries to avoid the increased tariffs imposed on products manufactured in the countries affected.73

|

Figure 11. U.S. Exports to EU, Canada, and Mexico subject to Section 232 Retaliation

|

|

|

Source: CRS analysis with data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Notes: Exports subject to retaliation at 6-digit HTS classification.

|

Table 1. Potential Costs and Benefits of Increased Tariffs

|

Economic Group

|

Potential Costs

|

Potential Benefits

|

|

U.S. consumers

|

Higher prices on goods subject to import tariffs and downstream products facing higher input costs

|

Lower prices on products subject to export retaliation

|

|

U.S. producers of domestic substitutes

|

|

Increased profit margins as tariffs allow for higher prices in domestic market

|

|

U.S. producers of downstream products

|

Decreased profit margins as input costs rise

|

|

|

U.S. exporters subject to retaliatory tariffs

|

Decreased profit margins as export sales decline and domestic prices fall due to lower foreign demand

|

|

|

Foreign producers subject to tariffs

|

Decreased profit margins as demand falls with rising import prices in U.S. market

|

|

Notes: Tariffs are only one of many variables affecting economic conditions in U.S. and global markets. Other factors, including fluctuations in the business cycle, exchange rates, and monetary policy may dominate the effects of the tariff changes.

In addition to these microeconomic effects, tariffs can also affect macroeconomic variables. With regard to the value of the U.S. dollar, as demand for foreign goods may fall in response to higher tariffs, U.S. demand for foreign currency may also fall, putting upward pressure on the relative exchange value of the dollar. This in turn would reduce demand for U.S. exports and increase demand for foreign imports, partly offsetting the effects of the tariffs. Tariffs may also affect national consumption patterns, depending on how the shift to higher cost domestic substitutes affects consumers' discretionary income and therefore aggregate demand. In the current tight labor environment tariffs may have less impact on overall U.S. employment levels, but may result in some movement of workers between industries and potential industry-specific unemployment as labor demand rises in domestic industries benefitting from the tariffs and falls in industries harmed by increased input costs or retaliatory tariffs. Economists generally agree that a reallocation of resources, including capital and labor, based on price distortions such as tariffs reduces efficiency and productivity over the long run.

What do economic studies estimate as the potential impacts of the tariff actions on the U.S. economy?

U.S. government and international institutions, think tanks, and consulting groups have prepared estimates of the potential impacts of the tariffs by projecting trade values using historical trade data and various modeling techniques (Table 2). These studies have produced a range of estimates, but generally suggest a moderately negative impact. The Congressional Budget Office, for example, estimates a 0.1% decline in the annual U.S. GDP growth rate resulting from the tariffs currently in place, while the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates approximately a 0.2% decline in the annual U.S. GDP growth rate. Most studies show slight employment gains and production increases in U.S. industries competing with the imports subject to additional tariffs and declines in sectors facing retaliation and heavily reliant on inputs subject to additional tariffs.

The net estimated effects are relatively modest, because approximately 10.5% of U.S. annual trade (12% of imports and 8% of exports) is affected by the tariff actions to date and trade represents a moderate share of total U.S. economic activity (27% of U.S. GDP in 2017). However, the effects may be substantial for individual firms reliant either on imports subject to the U.S. tariffs or exports facing retaliatory measures, as well as consumers for whom the affected products account for a large share of consumption.

The effects could grow if U.S. tariff actions and retaliation escalates. The IMF, for example, estimates that U.S. GDP growth could fall by approximately 1% and global growth could fall by 0.8% if the United States goes forward with an additional 25% tariff on imports from China and on motor vehicle imports from a number of countries, and partner countries retaliate.74 For context, in 2017 U.S. GDP was $19.5 trillion, making a 1% decline equivalent to a reduction in GDP of $195 billion. Staff from the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, recently noted that "trade policies and foreign economic developments could move in directions that have significant negative effects on U.S. economic growth."75 Part of this decline in economic growth reflects concern that the tariff escalation also creates a general environment of uncertainty. Economic research on uncertainty suggests it may lead to lower investment and generally restrain economic activity, including trade.76

These estimates, however, should be interpreted with caution because (1) they require various assumptions that can affect the predicted outcomes; (2) the extent of the U.S. tariffs and retaliation has fluctuated significantly in recent months and is subject to change; and (3) some of the studies were produced or sponsored by stakeholders advancing specific interests. Economists from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta also note that because tariffs have decreased significantly over the past several decades, there is a dearth of recent empirical evidence to inform models on tariff increases.77

Table 2. Selected Studies on the Economic Impact of Recent Tariff Actions

|

Date

|

Institution

|

Tariff Focus

|

Predicted Effects

|

|

April 2018

|

Federal Reserve Bank of Dallasa

|

Section 232 steel and aluminum and hypothetical escalation with EU and China

|

0.24% decline in U.S. GDP annual growth rate and 0.45% decline in investment, increases to 3.49% decline in U.S. GDP annual growth with prohibitive tariffs on all U.S.-China and U.S.-EU trade

|

|

June 2018

|

The Trade Partnershipb

|

Section 232 steel and aluminum

|

0.2% decline in U.S. GDP annual growth rate

|

|

July 2018

|

Peterson Institute for International Economicsc

|

Proposed Section 232 auto tariffs

|

Price increases in U.S. motor vehicles ranging from $1,409 - $6,971, depending on vehicle type

|

|

September 2018

|

OECDd

|

All current tariffs and proposed increases

|

0.3-0.4% increase in U.S. price level from current tariffs, growing to 1% increase with new tariffs on autos and additional tariffs on Chinese imports

|

|

September 2018

|

Barclayse

|

Hypothetical 20% U.S.-China and U.S.-global trade tariffs

|

0.2-0.4% decline in U.S. GDP annual growth rate, rising to a 1.5% decline if U.S. increases tariffs to 20% on all partners

|

|

October 2018

|

International Monetary Fundf

|

All current tariffs and proposed increases

|

0.2% decline in U.S. GDP annual growth rate, growing to 1% decline with new tariffs on autos and additional tariffs on Chinese imports

|

|

November 2018

|

Coalition for Prosperous Americag

|

Section 232 steel and aluminum

|

0.11% decline in U.S. GDP annual growth rate

|

|

November 2018

|

ImpactECONh

|

All current tariffs and proposed increases

|

1.78% decline in U.S. GDP annual growth rate, assuming additional U.S. tariffs on autos and Chinese imports and subsequent retaliation

|

|

December 2018

|

Economic Policy Institutei

|

Section 232 aluminum tariffs

|

Aluminum employment increase of 300 workers, eventually growing to 3,000

|

|

December 2018

|

The Tax Foundationj

|

All current tariffs and proposed increases

|

0.12% decline in U.S. GDP annual growth rate, growing to 0.5% decline with new tariffs on autos and additional tariffs on Chinese imports

|

|

January 2019

|

Congressional Budget Officek

|

All current tariffs

|

0.1% decline in U.S. GDP annual growth rate on average through 2029

|

Sources: Full citations for the studies below with hyperlinks embedded in the table above.

a. Michael Sposi and Kelvinder Virdi, Steeling the U.S. Economy for the Impacts of Tariffs, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Economic Letter, Volume 13, No. 5, April 2018;

b. Joseph Francois, Laura M. Baughman, and Daniel Anthony, Round 3: Trade Discussion of Trade War, The Trade Partnership, Policy Brief, June 5, 2018;

c. Mary E. Lovely, Jeremie Cohen-Setton, and Euijin Jung, Vehicular Assualt: Proposed Auto Tariffs will Hit American Car Buyers' Wallets, Peterson Institute for International Economics, Policy Brief 18-16, July 2018;

d. OECD, Interim Economic Outlook, September 20, 2018;

e. Barclays, U.S.- China Trade Tensions: When Giants Collide, September 12, 2018;

f. International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook 2018: Challenges to Steady Growth, October 9, 2018, pp. 33-35;

g. Jeffrey Ferry and Steven L. Byers, Measuring the Impact of the Steel Tariffs on the U.S. Economy, Coalition for a Prosperous America, November 2018;

h. Terrie Walmsley and Peter Minor, Estimated Impacts of US Sections 232 and 301 Trade Actions, ImpactECON, November 2018;

i. Robert E. Scott, Aluminum Tariffs Have Led to a Strong Recovery in Employment, Production, and Investment, Economic Policy Institute, December 11, 2018;

j. Erica York, The Economic and Distributional Impact of the Trump Administration's Tariff Actions, The Tax Foundation, December 5, 2018;

k. Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2019 to 2029, January 2019, pp. 25-29.

What are some potential long-term effects of escalating tariffs between countries?

Most economists agree that the U.S. and global economies have benefitted significantly from the major reduction in global tariff rates that has taken place since the 1940s. If tariff rates were to increase for a significant period of time it could insulate domestic producers from foreign competition, and potentially lead to less efficient and competitive production. This in turn could lead to lower overall economic growth in the United States and abroad, since more closed economies are generally less dynamic, with less innovation and productivity growth. Furthermore, retaliatory tariffs are particularly damaging to U.S. exporters in foreign markets because, unlike multilateral tariffs, the retaliatory tariffs only target U.S. imports. Therefore, exporters from other countries that compete with U.S. firms are likely to be more competitive in the retaliatory markets. Recent trade agreements involving major U.S. trade partners, but not the United States, such as the new EU-Japan FTA and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP or TPP-11) agreement, which consists of the 11 countries remaining in the TPP following the U.S. withdrawal, may likely compound this competitive disadvantage for U.S. exporters.78 Some argue it may be difficult for U.S. exporters to regain lost export opportunities in the future once importers establish relationships with suppliers from other countries.79

Another potential long-term effect of the tariffs is a shift in the U.S. role in international economic policymaking. While some stakeholders question the benefits of the dominant U.S. role in global rules-setting, others argue this has generally been of benefit to the United States, allowing U.S. priorities to feature prominently in existing international trade obligations.80 There are also concerns over the potential geopolitical aspects of tariff escalation. Some argue that the highly integrated nature of the global economy today acts as a deterrent to military conflict.81 Conversely, if tariff escalation creates a more fragmented global economy or imposes significant costs on a particular economy, it may lessen this deterrent.

Are there examples of U.S. producers benefitting or being harmed by the tariffs?

In addition to studies on the potential macroeconomic effects of the tariffs, a variety of anecdotal information on the tariffs' impact on specific businesses can be found in press reports or quarterly or annual company reporting. The President's tariff actions and subsequent retaliatory tariffs are only one of many factors influencing economic conditions for U.S. companies, making it difficult to assess the tariffs' direct effects.

In general, this anecdotal information largely conforms to the theoretical effects of the tariffs outlined in this report. Companies stating they have benefitted from the tariffs are producers competing with the imported products subject to the tariffs, while many downstream manufacturers and retailers assert they have been harmed. Many U.S. exporters subject to retaliatory tariffs also argue that these trade policy actions have negatively affected their operations. For some U.S. producers, the effects of the tariffs have been more complex, including companies that are both benefitting from higher domestic prices due to the tariffs while also being harmed by higher input costs. Companies with major overseas operations argue they have been indirectly harmed through lower sales abroad resulting from an economic slowdown in the countries subject to the Administration's tariff actions. The text box below provides selected examples of companies in each of these four broad categories.

|

Selected Companies with U.S. Operations Affected by the Tariffs

U.S. Producers Reportedly Benefitting from Increased Prices - ArcelorMittal (steel) – Company officials stated the tariffs were a "net positive," and CEO Lakshmi N. Mittal stated trade policies "helped in structurally changing the landscape of the steel industry," while reporting a profit increase to $1.9 billion in the second quarter of 2018, up 41% from the same quarter the previous year,82

- Nucor (steel) – CEO John Ferriola announced the "second strongest quarter in Nucor's history" for the second quarter of 2018 arguing that the company benefitted from reduced imports resulting from "the broad-based tariffs imposed under Section 232."83

- Century Aluminum (aluminum) – CEO Michael Bless, whose company is chiefly a domestic producer and the main proponent of the tariff, claims it has "created the conditions to support the restart of the U.S. primary aluminum capacity ... Once all the announced restarts are back online, U.S. production will be up 60%."84

U.S. Retailers and Downstream Producers Reportedly Harmed from Increased Prices - Walmart – CEO Doug McMillon stated that the company would attempt to delay price increases as long as possible but that it was being affected by Section 301 tariffs and eventually, it would be forced to increase prices, with worries about "what customers will have to pay if tariffs do escalate."85

- Ford – Ford CEO James Hackett claims that metals tariffs cost the company roughly $1 billion in profits.86

- Caterpillar – Claims that tariffs on steel and aluminum added $40 million to costs in the third quarter of 2018, with expectations of costs around $100 million for the second half of the year.87

- Beverage Companies – Warn that because they package their products in aluminum cans, the 10% tariff will force them to increase product prices. For example, the malt beverage industry claims that the tariff will cost it about $348 million, making it more difficult to grow and further invest in their U.S. operations.88 Coca-Cola's CEO James Quincey said the company expects to increase prices in part because the tariff on imported aluminum has made Coke cans more expensive to produce.89

U.S. Exporters Reportedly Harmed by Retaliatory Tariffs - Tyson Foods – Stated concerns over retaliatory tariff actions in Canada and Mexico, noting "because of the ongoing trade war and the tariffs it's produced – we're getting less for our products in some key markets."90 Pork is one of the largest U.S. export categories facing retaliatory tariffs in Canada and Mexico.