Background

Congress has been interested in disaster relief since the earliest days of the republic. On February 19, 1803, the 7th Congress passed the first known federal disaster assistance legislation, providing debt relief to the residents of Portsmouth, NH, following a December 26, 1802, fire that burned down most of the town ("A Bill for the Relief of the Sufferers by Fire, in the Town of Portsmouth," commonly known as the Congressional Act of 1803).1

Over the years, Congress has authorized the expansion of federal disaster assistance to individuals, businesses, and places (both for humanitarian reasons and as a means to enhance interstate commerce). For example

- During the 1930s, Congress passed legislation authorizing the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to make disaster loans for the repair and reconstruction of certain public facilities following an earthquake, and later, other types of disasters;2 and the Bureau of Public Roads to provide funding for highways and bridges damaged by natural disasters.3

- During the 1950s, Congress passed legislation authorizing the President to respond to major disasters.4

- During the 1960s, Congress passed legislation expanding the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' authority to implement flood control projects.5

- During the 1970s, Congress passed legislation authorizing federal loans and tax assistance to individuals affected by disasters, as well as federal funding for the repair and replacement of public facilities;6 and the establishment of the presidential disaster declaration process.7

- During the 1980s, Congress passed legislation authorizing numerous changes to federal disaster assistance programs administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which had been created by Executive Order 12127 on March 31, 1979, to, among other activities, coordinate federal disaster relief efforts.8

Since the 1980s, Congress has focused on the oversight of FEMA's implementation of federal disaster relief efforts and assessing the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (of 1988), hereinafter the Stafford Act, as amended (42 U.S.C. 5721 et seq.) to determine if its provisions meet current needs. One such potential need is providing disaster assistance following a terrorist attack.

Stafford Act Assistance in Response to Terrorism

The Stafford Act authorizes the President to issue two types of declarations that could potentially provide federal assistance to states and localities in response to a terrorist attack: a "major disaster declaration" or an "emergency declaration."9 Major disaster declarations authorize a wide-range of federal assistance to states, local governments, tribal nations, individuals and households, and certain nonprofit organizations to aid recovery from a catastrophic event. Major disaster declarations must be requested by the state governor or tribal leader. Emergency declarations authorize a more limited range of federal assistance and are issued by the President to protect property and public health and safety and to lessen or avert the threat of a major disaster.10 In most cases, the state governor or tribal leader must request an emergency declaration; however, under 501(b) of the Stafford Act, the President has authority to issue an emergency declaration without a gubernatorial or tribal request under specified conditions.11 Examples of these types of emergency declarations with respect to terrorist incidents include the April 19, 1995, bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Building in Oklahoma City, and the September 11, 2001, attack on the Pentagon.12 In each instance, the emergency declaration was followed by a major disaster declaration.

While the Stafford Act has been used to provide assistance in response to terrorist attacks in the past, recent incidents such as the mass shootings that occurred in 2015 and 2016 in San Bernardino, CA, and Orlando, FL, respectively, and the 2016 vehicular attacks in Nice, France, and Ohio State University may have brought to light some potential shortcomings in the Stafford Act. That is, certain terror attacks may not meet the criteria of a major disaster for two reasons. First, depending on the mechanism used in the attack, certain terror incidents may not meet the legal definition of a major disaster. Of interest here, the Stafford Act defines a major disaster as "any natural catastrophe (including any hurricane, tornado, storm, high water, wind-driven water, tidal wave, tsunami, earthquake, volcanic eruption, landslide, mudslide, snowstorm, or drought), or, regardless of cause, any fire, flood, or explosion, in any part of the United States, which in the determination of the President causes damage of sufficient severity and magnitude to warrant major disaster assistance."13 The list of incidents that qualify for a major disaster declaration is specifically limited, and it is not clear if a terror attack would meet the legal definition of a major disaster if the incident involved something other than a fire or explosion.

Meeting the definition of a major disaster is a necessary but insufficient condition for the receipt of major disaster assistance. The incident's cost must also be beyond the capacity of the state and local government. When an incident occurs, FEMA meets with the state to assess damage costs to affected homes and public infrastructure. Damages to public infrastructure are particularly important because this amount is compared to the state's population. This comparison is called the "per capita threshold." FEMA uses the threshold to assess state and local government capacity. In general, FEMA will recommend that the President declare a major disaster if the incident meets or exceeds the per capita threshold. It is conceivable that a terrorist incident could cause substantial loss of life but cause little or no damage to homes and public infrastructure. This lack of damage (to public infrastructure) may disqualify these incidents from receiving the wider range of assistance provided under a major disaster declaration.

With respect to terrorism, some may view the Stafford Act's current framework adequate and oppose efforts to alter it. Their reasons are twofold. First, while terrorist incidents such as mass shootings can be devastating in terms of loss of life and impact on national morale, some argue that a major disaster should not be declared for terrorist incidents that do not cause enough damage to public infrastructure to warrant federal assistance. State and local governments, as well as insurance coverage, they say, should be the main sources of assistance if damages are limited. Second, they may argue that terror incidents that do not meet the criteria of a major disaster could be eligible for Stafford Act assistance under an emergency declaration. In contrast to the prescribed definition of incidents that qualify as a major disaster, an emergency is defined more broadly to include "any occasion or instance for which, in the determination of the President, federal assistance is needed to supplement State and local efforts and capabilities to save lives and to protect property and public health and safety, or to lessen or avert the threat of a catastrophe in any part of the United States."14

Some might argue that an emergency declaration would provide adequate assistance to individuals and households after a terrorist incident. For example, as outlined in Section 502 of the Stafford Act, an emergency declaration may include Section 408 assistance. Some examples of Section 408 assistance include

- FEMA's Individuals and Household Program (IHP), which provides housing and grants to individuals and families; and

- Other Needs Assistance (ONA) grants, which is part of the IHP program in the form of grants to families and individuals. These grants can cover items including medical and dental expenses caused by the incident as well as funeral expenses. ONA grants may also cover certain necessary expenses such as the replacement of personal property and other expenses.

Others may argue that most acts of terrorism warrant the wide range of assistance provided by a major disaster declaration. They would argue that the assistance provided under an emergency declaration is too limited. For example, the Crisis Counseling program is not provided under an emergency declaration.15 The Crisis Counseling program may seem especially appropriate to a terrorist incident given the assistance it provides for what is likely a wrenching event for those involved.

In addition, the type of declaration determines what types of Small Business Administration (SBA) disaster loans are available. In general, homeowners, renters, businesses, and nonprofit organizations become eligible for disaster loans under a major disaster declaration. In contrast, typically only private nonprofit organizations are eligible for disaster loans under an emergency declaration. Finally, beyond the monetary assistance provided by a major disaster declaration, some would argue that major disaster declarations are important symbolic gestures of federal support to states and localities.

Declaration Procedure

The Stafford Act requires that all major disaster declaration requests be made by state governors or tribal leaders. Such requests must be made on the basis that the incident is of such severity and magnitude that effective response is beyond the capability of the affected state and local government. The request for a declaration begins with a letter to the President from the governor or tribal leader. Included with the letter are supplemental material and any relevant information about the incident.16 The letter also describes what types of federal assistance is being requested. In the case of a request for a major disaster declaration, a particularly important piece of information accompanying the letter is the Preliminary Damage Assessment (PDA). PDAs provide public infrastructure damage estimates (as well as estimated damage to households). By regulation, FEMA compares this damage estimate against the state's population.17 In general, FEMA will make a recommendation to the President that a major disaster be declared if public infrastructure damages exceed $1.42 per capita. This formula is known as the "per capita threshold."18

A request for an emergency declaration follows the same basic regulatory procedures highlighted above for major disasters with some nuances. Similar to a request for a major disaster declaration, the basis for an emergency declaration is that the incident is of such severity and magnitude that effective response is beyond the capability of the affected state and local government. FEMA, however, does not apply any formulas—including the per capita threshold—in regulations to make emergency declaration recommendations to the President.

While there are differences between the two types of declarations, the ultimate decision to declare and grant federal assistance for emergencies and major disasters rests solely with the President.

Major Disaster Declaration Criteria

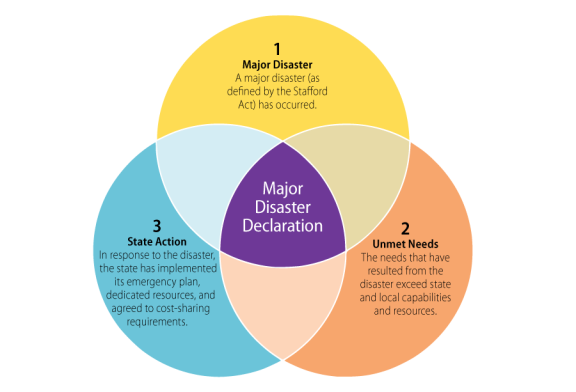

In general, an incident must meet three criteria to be eligible for a major disaster declaration: (1) definition, (2) unmet need, and (3) state action.

Definition

The Stafford Act defines a major disaster as

any natural catastrophe (including any hurricane, tornado, storm, high water, wind-driven water, tidal wave, tsunami, earthquake, volcanic eruption, landslide, mudslide, snowstorm, or drought), or, regardless of cause, any fire, flood, or explosion, in any part of the United States, which in the determination of the President causes damage of sufficient severity and magnitude to warrant major disaster assistance under this chapter to supplement the efforts and available resources of states, local governments, and disaster relief organizations in alleviating the damage, loss, hardship, or suffering caused thereby.19

The definition of a major disaster can be applied in several ways. The definition could be applied prescriptively. In this view, the definition would be considered as an itemized list of incidents eligible for federal assistance under the Stafford Act. As a result, certain incidents are not eligible for assistance because the definition is taken as verbatim and all inclusive. Another approach is to consider the definition as open to interpretation. In this view, the list of incidents is seen as providing examples of some of the incidents that could be considered a major disaster. Alternatively, the definition could be seen as a blend of the two approaches. The list of natural disasters might be seen as open-ended whereas human caused incidents are limited to the itemized list of "fire, flood, or explosion." Depending on the interpretation, the definition may limit certain incidents from receiving federal assistance.

The discussion regarding whether an incident would be denied assistance due to definitional limitations is hypothetical. There have been incidents denied for definitional reasons (such as the Flint water contamination incident) but thus far a Governor has not requested a major disaster for a terrorist incident and denied assistance based on the definition of a major disaster. It is unclear if the definition would be fatal to a request for a major disaster declaration. Ultimately, the President has the discretion to determine what incidents that meet this definition are eligible for a major disaster declaration.

Unmet Need

In addition to meeting the definition of a major disaster, the incident must result in damages significant enough to exceed the capabilities and resources of state and local governments. Exceeding state and local capabilities and resources is generally considered as the state's unmet need. Under the Stafford Act:

All requests for a declaration by the President that a major disaster exists shall be made by the Governor of the affected state. Such a request shall be based on a finding that the disaster is of such severity and magnitude that effective response is beyond the capabilities of the state and the affected local governments and that federal assistance is necessary.20

In general, FEMA assesses the degree of damage for an incident to help determine unmet need. FEMA considers six general areas:

- estimated cost of the assistance;

- localized impacts;

- insurance coverage;

- hazard mitigation;

- recent multiple disasters; and

- other federal assistance programs.

While all of these factors are considered when assessing an incident's worthiness for federal assistance, the estimated cost of assistance is perhaps the most critical because it contains the per capita threshold mentioned earlier in this report, as well as the unmet needs of families and individuals. Attacks such as the 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting in Florida and the 2015 San Bernardino, CA, shooting had a high number of fatalities with relatively low damages to public infrastructure. Limited public infrastructure damages may make the per capita threshold difficult to reach—particularly for highly populated states.

State Action

The state or tribal nation must implement its emergency plan, dedicate sufficient resources to respond to the incident, and agree to cost-sharing requirements, as follows:

As part of such request, and as a prerequisite to major disaster assistance under this chapter, the Governor shall take appropriate response action under state law and direct execution of the state's emergency plan. The Governor shall furnish information on the nature and amount of State and local resources which have been or will be committed to alleviating the results of the disaster, and shall certify that, for the current disaster, state and local government obligations and expenditures (of which state commitments must be a significant proportion) will comply with all applicable cost-sharing requirements of this chapter.21

As conceptualized in Figure 1, an incident is eligible for a disaster declaration if all three criteria intersect. An incident that does not meet the definition of a major disaster, and/or does not have unmet need would not have intersecting criteria and may have more difficulty receiving a major disaster declaration.

|

Figure 1. Major Disaster Declaration Criteria Definition, Unmet Need, and State Action |

|

|

Source: Based on CRS analysis of Sections 102(2) and 401 of the Stafford Act. |

Major Disaster Assistance

FEMA Assistance

The assistance provided for a major disaster declaration generally takes three forms: Public Assistance (PA), Individual Assistance (IA), and Hazard Mitigation Assistance (HMA). PA addresses the state or tribe's essential needs but concentrates on repairing damage to infrastructure (public roads, buildings, etc.).22 IA helps families and individuals. IA can be in the form of temporary housing assistance and grants to address post-disaster needs (such as replacing furniture, clothing and other items). It may also include crisis counseling and disaster unemployment benefit. HMA provides grant funding to the state for mitigation projects. HMA does not necessarily need to mitigate risks from the type of disaster that was declared. Rather, HMA can be used for mitigation projects identified before the declaration was issued.

FEMA, however, does not exclusively perform all disaster response and recovery operations for the federal government. The President has the authority to direct any federal agency to use its authorities and resources to support state and local response and recovery efforts, primarily through Sections 402, 403, and 502 of the Stafford Act. In general, when a declaration is declared, FEMA coordinates federal entities and organizations that are involved in the incident by "assigning" missions to relevant agencies to address a state's request for federal assistance or support overall federal operations pursuant to, or in anticipation of, a Stafford Act declaration.23 The activities carried out by other agencies through Mission Assignments are generally reimbursed by FEMA through the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF).24 For example, FEMA may request the Department of Health and Human Services to establish and operate a shelter co-located with a federal medical station to support non-medical caregivers and family members accompanying patients being treated at the station.

SBA Disaster Loan Program

Major disaster declarations also put the Small Business Administration (SBA) Disaster Loan Program into effect.25 The loan program provides three main types of loans for disaster-related losses: (1) Home and Personal Property Disaster Loans, (2) Business Physical Disaster Loans, and (3) Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDL).26 Home Physical Disaster Loans provide up to $200,000 to repair or replace disaster-damaged primary residences.27 Personal Property Loans provide up to $40,000 to replace personal items such as furniture and clothing.28 Business Physical Disaster Loans provide up to $2 million to help businesses of all sizes and nonprofit organizations repair or replace disaster-damaged property, including inventory and supplies.29 EIDLs provide up to $2 million to help meet financial obligations and operating expenses that could have been met had the disaster not occurred.30 Loan proceeds can only be used for working capital necessary to enable the business or organization to alleviate the specific economic injury and to resume normal operations.31 Loan amounts for EIDLs are based on actual economic injury and financial needs, regardless of whether the business suffered any property damage.

Major disaster declarations that include both IA and PA make all three loan types available. Only private non-profit organizations are eligible for SBA physical disaster loans and EIDL, if the major disaster declaration only provides PA.

It is important to note that SBA disaster loans are usually the only type of federal assistance available to businesses after a terror attack because FEMA does not provide assistance to the private sector.

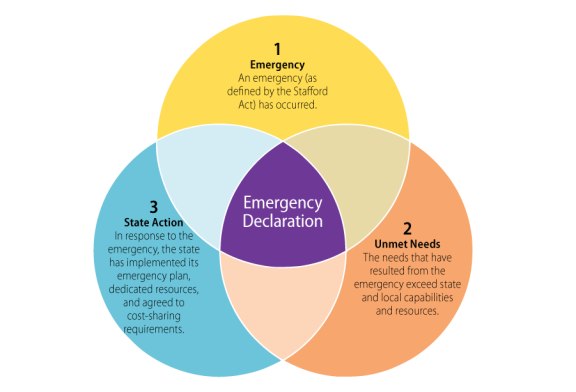

Emergency Declaration Criteria

The three criteria for an incident to be eligible for an emergency disaster declaration include (1) definition, (2) unmet need, and (3) state action.

Definition

The Stafford Act defines an emergency as

any occasion or instance for which, in the determination of the President, federal assistance is needed to supplement State and local efforts and capabilities to save lives and to protect property and public health and safety, or to lessen or avert the threat of a catastrophe in any part of the United States.32

While the definition of a major disaster includes a list of incidents that could be considered a major disaster, emergencies are defined more broadly. Consequently, a terrorist attack such as a mass shooting or other nontraditional attack (such as using a vehicle as a weapon) under consideration as an "emergency" would likely not face the definitional challenge posed by the "major disaster" definition.

Federal Responsibility

The Stafford Act procedure for an emergency declaration can be particularly useful when a terrorist incident involves federal property or a federal program is Section 501(b) of the act:

The President may exercise any authority vested in him by section 502 or section 503 with respect to an emergency when he determines that an emergency exists for which the primary responsibility for response rests with the United States, because the emergency involves a subject area for which, under the Constitution or laws of the United States, the United States exercises exclusive or preeminent responsibility and authority. In determining whether or not such an emergency exists, the President shall consult the Governor of any affected state, if practicable. The President's determination may be made without regard to subsection (a).33

While Presidents have rarely invoked this authority, it could provide a path for rapid action and certain forms of terrorism might be easily and justly defined as a federal responsibility. And as noted previously, emergency declarations can later be converted to major disaster declarations. The use of Section 501(b) is infrequent and has been invoked on three occasions: (1) the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building bombing in Oklahoma City in 1995, (2) the 2003 Space Shuttle Columbia explosion,34 and (3) the terrorist attack on the Pentagon on September 11, 2001.

It could be argued that the usefulness of 501(b) would be limited to certain situations that involve areas of federal responsibility (e.g., federal properties or programs). It could be further argued that that the use of Section 501(b) would be inappropriate, if the incident occurred in a business setting or an area of state and local jurisdiction. Others might disagree and argue that all terrorist incidents are a federal responsibility regardless of where they occur in the United States. According to this view, the 501(b) authority could be useful in the initial stages of a terrorist event since it provides the President with the discretion to act quickly without having to wait for a gubernatorial request for assistance. Others might be concerned that Section 501(b) might be invoked too often if applied to any situation that involved terrorism. For example, they may argue that it could lead to an expansion of federal assistance if routinely used in terror-related mass shootings.

Unmet Need

In general, similar to a major disaster, an incident must result in damages significant enough to exceed the capabilities and resources of state and local governments. Under the Stafford Act

All requests for a declaration by the President that an emergency exists shall be made by the Governor of the affected state. Such a request shall be based on a finding that the situation is of such severity and magnitude that effective response is beyond the capabilities of the state and the affected local governments and that federal assistance is necessary.35

As mentioned previously, the President has the authority to issue an emergency declaration in certain circumstances without a gubernatorial or tribal request. Thus, in certain circumstances, the response does not need to be beyond the capabilities of state and local governments since the response could be considered a uniquely federal responsibility.

State Action

As with a major disaster, the state or tribal nation must implement its emergency plan, dedicate sufficient resources to respond to the incident, and agree to cost-sharing requirements, as follows:

As a part of such request, and as a prerequisite to emergency assistance under this act, the Governor shall take appropriate action under State law and direct execution of the State's emergency plan. The Governor shall furnish information describing the state and local efforts and resources which have been or will be used to alleviate the emergency, and will define the type and extent of federal aid required. Based upon such Governor's request, the President may declare that an emergency exists.36

As illustrated in Figure 2, an incident is eligible for an emergency declaration if all three criteria intersect. An incident that does not meet the definition of a major disaster, or does not have unmet need would not have intersecting criteria and may have more difficulty receiving a major disaster declaration.

|

Figure 2. Emergency Declaration Criteria Definition, Unmet Need, and State Action |

|

|

Source: Based on CRS analysis of Sections 102(1) and 501(a) of the Stafford Act. |

Emergency Declaration Assistance

FEMA Assistance

Emergency declarations authorize activities that can help states and communities carry out essential services and activities that might reduce the threat of future damage. Emergency declarations authorize less assistance than a major disaster. Emergency declarations do not provide assistance for repairs and replacement of public infrastructure or nonprofit facilities. However, they do provide emergency services under the Stafford Act and other actions that might lessen the threat of a major disaster.

As with major disaster declarations, the President has the authority under an emergency declaration to direct any federal agency to use its authorities and resources in support of state and local response and recovery efforts under 502 of the Stafford Act. Also, the emergency authority includes Section 408 which means that housing assistance and grants for individuals and families could be provided under an emergency declaration.

SBA Disaster Loan Program

Emergency declarations also trigger the SBA Disaster Loan Program, albeit usually on a limited basis. All three SBA disaster loan types are available when the emergency declaration includes IA. Emergency declarations, however, rarely provide IA. Typically, limited PA is provided. For example, 281 emergences were declared from 1990 to 2015. Of these, 18 included IA. SBA disaster loans are generally only available to private, non-profit organizations for "PA-only" declarations. Some may see this as a limitation. For example, if an incident affected a business (e.g., malls, movie theaters, or nightclubs), those businesses would not be eligible for an SBA disaster loan under a PA-only emergency declaration.

Selected Examples of Stafford Act Assistance for Terror Incidents

The following section provides information on past terror attacks that have received federal assistance under the Stafford Act, including a general description of what types of assistance was provided for the incident. It also provides information on the Orlando Pulse nightclub shooting. It is included in this discussion because the governor requested Stafford Act assistance. The San Bernardino and Ohio State attacks are not included because Stafford Act declarations were not requested. Table 1 provides a comparison of each incident. It is notable that in all but one case, the declaration was issued on the same day as the attack.

Oklahoma City Bombing

An emergency declaration was issued to Oklahoma for the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building Bombing on April 19, 1995—the day of the bombing.37 The emergency declaration permitted FEMA to take vital actions necessary just hours following the tragedy. This principally involved bringing in FEMA's Urban Search and Rescue (USAR) teams.38 USAR Task Forces began arriving in Oklahoma City the afternoon of April 19, 1995.39 In addition, the emergency declaration also provided the sources that allowed the debris removal process to begin. Debris removal, however, was a challenging operation since the area to be cleared was also a Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) crime scene and new protocols were needed to accomplish response operations in that unique environment. As then-FEMA Director James Lee Witt explained:

Here were two earnest, dedicated, well-trained groups working as hard as they could—and yet there was an inherent conflict between them. In clearing out the debris, the search and rescue people needed to proceed slowly, carefully. The FBI wanted to pick up the pace, to get their hands on crime evidence immediately—and they wanted that evidence not to be contaminated. Each group was under tremendous pressure.40

A major disaster declaration was later issued for the incident on April 26, 1995. This action permitted, at the request of the governor, the activation of the Crisis Counseling program.41 This program provides funding to state and local mental health authorities to provide service to survivors affected by a disaster incident. Since the great majority of damage was to federal facilities, FEMA's expenditures were limited for this event since FEMA aid under the Stafford Act is directed toward the losses of state, tribal and local governments. Aid to families and individuals (which includes crisis counseling) was the largest program expenditure at $5.5 million.

SBA approved 163 disaster loans for $7.3 million. This included 71 approved home disaster loans for $452,700 and 92 business disaster loans for $6.8 million.42

September 11th Terrorist Attacks

Following the attacks on the Twin Towers, a major disaster declaration was issued on September 11, 2001 for the state of New York.43 The following day an emergency was declared for Virginia, site of the Pentagon attack. Later, on September 21, 2001, a major disaster was declared for Virginia with September 11th identified as the beginning of the incident period.44

The scope of the New York attacks, along with the President's declaration, resulted in legislation that appropriated $40 billion to address not only recovery for these events but security concerns, including transportation safety and initiating counter measures against terrorism. Half of the appropriated amount ($20 billion) was devoted by law (P.L. 107-38) to recovery and assistance efforts in New York, Virginia, and Pennsylvania. FEMA's work involved urban search and rescue teams, debris removal, crisis counseling, and housing aid for displaced residents. FEMA's DRF expenditures in New York alone surpassed $8.7 billion.45

In the case of Virginia, the largest expenditures were for aid to families and individuals. More than $14.5 million was provided for these programs (including crisis counseling), while nearly $5 million was provided for emergency work and debris clearance.

The two disaster declarations triggered the SBA Disaster Loan Program. For New York, SBA approved 6,384 loans for roughly $551 million. This included 412 approved home loans for roughly $6.0 million, 566 approved business loans for $37 million, and 5,406 approved EIDL loans for $507 million. For Virginia, SBA approved 256 loans for roughly $31 million. This included one approved business loan for $125,500, and 255 approved EIDL loans for approximately $31 million.46

Boston Marathon Bombing

An emergency declaration was issued to Massachusetts on April 17, 2013, for the Boston Marathon Bombing—two days after the incident.47 The Boston bombing was a unique situation that resulted in a large man-hunt, the shutdown of a major city, and the eventual capture of one perpetrator and the killing of the other in a shootout with the police.

Unlike some other terrorism-related incidents, this event stretched out over several days. In addition to the damage caused at the blast site, it also tested the resources of state and local first responders throughout the area. FEMA's Deputy Administrator explained FEMA's post-incident role:

FEMA was authorized to provide Category B emergency protective measures to include items such as police personnel, search and rescue, and removal of health and safety hazards. FEMA also provided Public Assistance to include funding for shelters and emergency care for Norfolk and Suffolk counties, which was primarily used for residents whose homes had been impacted during the blast or could benefit from crisis counseling.48

Eventually, the incident period was extended, beginning on April 15, 2013, and concluding on April 22, 2013, to capture the eligible costs expended by public safety and other response personnel throughout the region. FEMA's portion of those costs (75% of the eligible amount) totaled just over $6 million. Additionally, FEMA "authorized state and local agencies in Massachusetts to use existing preparedness grant funding to support law enforcement and first responder overtime costs resulting from investigation support activities or heightened security measures."49

SBA approved four EIDL loans for $214,300 in the aftermath of the Boston Marathon Bombing.50 Other SBA disaster loan types were not available because the incident was declared an emergency (as opposed to a major disaster).

Orlando Pulse Nightclub Shooting

On June 13, 2016, Florida Governor Rick Scott made a request to the President to issue an emergency declaration in response to the mass shooting at Pulse nightclub in Orlando, FL, on June 12, 2016. The governor's request is the first known Stafford Act request in response to a mass shooting incident. The governor requested $5 million for emergency protective measures (Category B) under the Public Assistance program. The assistance was intended to address health and safety measures, and assistance for management, control, and reduction of immediate threats to public health and safety.

According to FEMA Administrator Craig Fugate, the President denied the request for assistance partly because the Governor could not satisfactorily demonstrate that the response to the incident was beyond the capacity of the state and local governments. According to the denial letter sent by FEMA Administrator Craig Fugate to Governor Rick Scott:

a presidential emergency declaration under the Stafford Act applies when federal assistance is needed to supplement state and local efforts and capabilities to save lives and to protect property and public health and safety, or to lessen or avert the threat of a catastrophe. Because your request did not demonstrate how the emergency response associated with this situation is beyond the capability of the state and affected local governments or identify any direct federal assistance needed to save lives or protect property, an emergency declaration is not appropriate for this incident.51

The request was also denied because other forms of federal assistance would be provided for the incident. The letter further states:

although the Stafford Act is not the appropriate source of funding for those activities and this situation, several federal agencies, including the Department of Justice, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and FEMA have resources that may help support the response to this incident absent an emergency declaration under the Stafford Act. We will work closely with you and your staff to identify these additional capabilities.52

Although the request for an emergency declaration was denied, FEMA approved a request from Florida to reallocate $253,000 in unspent money from the Homeland Security Grant Program to help pay for overtime costs in the wake of the shooting.53

SBA only provided EIDL for the attack and related investigation. This included five approved loans for $353,400.54

|

Oklahoma City Bombing April 19, 1995 |

September 11th Terrorist Attacks September 11, 2001 |

Boston Marathon Bombing April 15, 2013 |

Orlando Pulse Nightclub Shooting June 12, 2016 |

|

|

Emergency Declaration number and Date |

EM-3115 April 19, 1995 |

Virginia: EM-3168 New Jersey: EM-3169 |

EM-3362 April 17, 2013 |

Request Denied |

|

Major Disaster Declaration number and Date |

DR-1048 April 26, 1995 |

New York: DR-1391 Virginia: DR-1392 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Total FEMA Projected Obligations |

$33,017,023 |

New York: $8,703,240,139 Virginia: $28,326,526 New Jersey: $89,273,429 |

$6,567,942 |

N/A |

|

Public Assistance |

Yes |

New York: Yes Virginia: Yes New Jersey: Yes |

Yes |

N/A |

|

Individual Assistance |

Yes |

New York: Yes Virginia: Yes New Jersey: No |

No |

N/A |

|

SBA Declaration Date and Loan Type |

Program Automatically Triggered by Major Disaster Declaration |

Program Automatically Triggered by Major Disaster Declaration |

April 26, 2013 EIDL Only |

June 23, 2016 EIDL Only |

|

SBA Home Disaster Loan Amount |

$453,000 |

New York: $6,100,000 Virginia: N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

SBA Business Disaster Loan Amount |

$6,800,000 |

New York: $37,500,000 Virginia: $125,500 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

SBA EIDL Amount |

N/A |

New York: $507,000,000 Virginia: $31,400,000 |

$214,000 |

$353,000 |

Sources: Based on CRS analysis of funding data provided by FEMA and SBA. Declaration information was derived from https://www.fema.gov/disasters and https://www.sba.gov/loans-grants/see-what-sba-offers/sba-loan-programs/disaster-loans/current-disaster-declarations.

Policy Considerations

It is generally agreed that the government should help victims of terrorism in times of need, but the proper scope of that assistance with respect to the Stafford Act is subject to debate. Some might question whether the fiscal responsibility resides primarily with the federal or the state government. The debate may be further complicated if the incident does not clearly meet the definition of a major disaster or does not meet certain thresholds, or both. The selected approach will likely be influenced by how policymakers view the role of the federal government in response to terrorism. Some may argue that Stafford Act assistance is warranted for all or most acts of terrorism. Others might argue that Stafford Act assistance should only be provided in cases where the incident meets the existing framework of definitions and unmet need.

Major Disaster Definition

As mentioned previously, the definition of a major disaster contains a list of incidents that can be considered a major disaster. One hypothetical concern is, as currently defined, certain acts of terror may not meet the definition of a major disaster. The following discussion demonstrates how Congress designed the definition to address natural disasters and human-caused incidents.

The term "major disaster" was originally defined in the Federal Disaster Relief Act of 1950 as

any flood, drought, fire, hurricane, earthquake, storm, or other catastrophe in any part of the United States which, in the determination of the President, is or threatens to be of sufficient severity and magnitude to warrant disaster assistance by the federal government to supplement the efforts and available resources of states and local governments in alleviating the damage, hardship, or suffering caused thereby, and respecting which the governor of any State (or the Board of Commissioners of the District of Columbia) in which such catastrophe may occur or threaten certifies the need for disaster assistance under this Act, and shall give assurance of expenditure of a reasonable amount of the funds of the government of such state, local governments therein, or other agencies, for the same or similar purposes with respect to such catastrophe.55

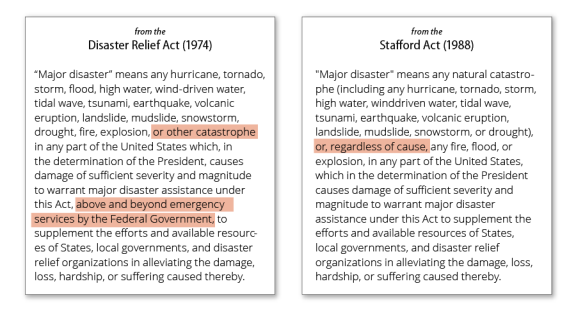

Congress expanded on the list of specific incidents when it amended the definition in the Disaster Relief Act of 1974 which defined a major disaster as

any hurricane, tornado, storm, flood, high water, wind-driven water, tidal wave, tsunami, earthquake, volcanic eruption, landslide, mudslide, snowstorm, drought, fire, explosion, or other catastrophe in any part of the United States which, in the determination of the President, causes damage of sufficient severity and magnitude to warrant major disaster assistance under this Act, above and beyond emergency services by the federal government, to supplement the efforts and available resources of States, local governments, and disaster relief organizations in alleviating the damage, loss, hardship, or suffering caused thereby.56

It is notable that the Senate report on the bill indicated that a major disaster is defined as "any damage caused by these hazards determined by the President to be of sufficient severity and magnitude to warrant federal assistance" to supplement state and local efforts.57 To some, this would support the argument that the definition should be prescriptively viewed as a list of eligible incidents.

Congress amended the definition again in 1988—the year the Stafford Act was enacted. Congress designed the new definition with a subtle change in wording to limit human-caused incidents from receiving major disaster declarations. As shown in Figure 3, Congress removed "or other catastrophe" from the definition of a major disaster and inserted "or, regardless of cause."

According to the Senate report accompanying the bill, Congress removed "other catastrophe" because it had been broadly interpreted to justify federal assistance to humanly caused incidents. According to the Senate report

Congress intended the [the Disaster Relief Act of 1974] to alleviate state and local conditions caused by natural catastrophes. Although non-natural catastrophes are not specifically enumerated by Section 102 of the act, the phrase "other catastrophes" has been broadly interpreted to justify federal assistance in response to humanly caused traumatic events. The expansion of legislative intent in the administration of the Disaster Relief Act has provoked recent congressional concern.58

The report further states that

Broadening the scope of the act to cover both natural and non-natural catastrophes has strained the capacity of programs designed to respond only to natural catastrophes. Within its intended context the act has functioned relatively well. It is comprehensive and flexible legislation, well-suited to handle the full range of natural disasters for which it was designed. It was not written, however, to respond to the occasionally catastrophic consequences of social, economic, or political activity and establishes no administrative or programmatic mechanisms to do so.59

As demonstrated above, it appears that Congress sought to prevent the Stafford Act from being used to address an array of social issues and the specificity of the amended definition may have precluded some incidents from being declared a major disaster. For example, Michigan Governor Rick Snyder's request for a major disaster declaration for the Flint water contamination incident was denied based on the grounds that it did not meet the definition of a major disaster. The denial letter sent from the FEMA Administrator to the governor (see Appendix) stated the incident did not meet the legal definition of a major disaster because it was "not a result of a natural disaster, nor was it caused by fire, flood, or explosion."60

Another potential issue related to the definition's strict enumeration of human-caused incidents is that it is hypothetically conceivable that two incidents with equal damages and loss of life with different mechanisms of destruction would be treated differently in terms of eligibility. For example, an explosion that kills 50 people could be eligible for a major disaster (if there are sufficient damages to public infrastructure) whereas if a vehicle (similar to the 2016 Nice, France, attack) was used to kill 50 people it could arguably be considered ineligible. A similar argument could be made about a sarin gas attack or a cybersecurity attack that do not involve an explosion or result in fire.

Others may argue that the definition's specificity would not preclude terror incidents from being declared major disasters if the consequences merited a major disaster declaration—regardless of the mechanism. They may further argue that an incident could be recast with some ingenuity to make the incident conform to the definition. For instance, they may argue that, broadly interpreted, firing a gun or releasing gas involves a type of explosion. An arguable example of recasting incident was attempted in the unsuccessful appeal of Flint water contamination incident. The appeal letter stated that

Respectfully, I appeal the determination that the event "does not meet the legal definition of a major disaster under 42 U.S.C. §5122." This unique disaster poses imminent and long-term threat to the citizens of Flint. Its severity warrants special consideration for all categories of the Individual and Public Assistance Programs, as well as the Hazard Mitigation program in order to facilitate recovery. While the definition under 44 C.F.R. §206.2(17) provides examples of what might constitute a natural disaster, I submit that this disaster is analogous to the flood category, given that the qualities within the water, over a long term, flooded and damaged the city's infrastructure in ways that were not immediately or easily detectable. This disaster is a natural catastrophe in the sense that lead contamination into water is a natural process.61

One concern that could emerge from broad interpretations of the definition is that it could lead to "declaration creep" wherein marginal incidents are increasingly considered major disasters. They may also argue that incidents without fire or explosions would likely not create significant damages and would therefore not warrant a major disaster declaration. An emergency declaration would be more appropriate according to this view.

If Congress is concerned that the definition of a major disaster might preclude some incidents from receiving federal assistance, it could consider amending the definition to explicitly include terrorism. Since FEMA is a component agency of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) it might be assumed that a potential definition would be the one used by DHS. There are, however, multiple definitions used by the federal government and there is no consensus on the definition of terrorism. As demonstrated in Table 2, several U.S. governmental agencies have different definitions of terrorism. In some definitions, such as the one used by the Department of State, the act must be politically motivated whereas in other definitions it does not need to be a factor (such as the one used by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and DHS). Some might argue that definitions that rely on motivation are problematic if applied to Stafford Act assistance because they are based on the intentionality of the act rather than the act's consequences. For example, a mass shooting that is motivated by hate or brought about by mental illness might not be considered an act of terrorism while a similar incident that is politically motivated might.

Perhaps an alternative approach would be expanding the types of assistance available under an emergency declaration rather than amending the definition. For example, Congress could make crisis counseling and SBA disaster loans for businesses and households available under emergency declarations. This would arguably help to address events where there is great loss of life but relatively little damage to public infrastructure. These measures may also provide a boost for public morale in such a situation as well as an assurance to state and local governments that they may receive some supplemental help.

|

Department of 6 U.S.C. 101 |

(16) The term "terrorism" means any activity that— (A) involves an act that— (i) is dangerous to human life or potentially destructive of critical infrastructure or key resources; and (ii) is a violation of the criminal laws of the United States or of any State or other subdivision of the United States; and (B) appears to be intended— (i) to intimidate or coerce a civilian population; (ii) to influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion; or (iii) to affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping. |

|

Federal Bureau 28 C.F.R. .85 (l) |

"Terrorism includes the unlawful use of force and violence against persons or property to intimidate or coerce a government, the civilian population, or any segment thereof, in furtherance of political or social objectives." |

|

Department 22 U.S.C. 2656f(d)(2) |

"the term 'terrorism' means premeditated, politically motivated violence perpetrated against noncombatant targets by subnational groups or clandestine agents" |

|

U.S. Code 18 U.S.C. 2331 |

(1) the term "international terrorism" means activities that— (A) involve violent acts or acts dangerous to human life that are a violation of the criminal laws of the United States or of any State, or that would be a criminal violation if committed within the jurisdiction of the United States or of any State; (B) appear to be intended— (i) to intimidate or coerce a civilian population; (ii) to influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion; or (iii) to affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping; and (C) occur primarily outside the territorial jurisdiction of the United States, or transcend national boundaries in terms of the means by which they are accomplished, the persons they appear intended to intimidate or coerce, or the locale in which their perpetrators operate or seek asylum; (2) the term "national of the United States" has the meaning given such term in section 101(a)(22) of the Immigration and Nationality Act; (3) the term "person" means any individual or entity capable of holding a legal or beneficial interest in property; (4) the term "act of war" means any act occurring in the course of— (A) declared war; (B) armed conflict, whether or not war has been declared, between two or more nations; or (C) armed conflict between military forces of any origin; and (5) the term "domestic terrorism" means activities that— (A) involve acts dangerous to human life that are a violation of the criminal laws of the United States or of any State; (B) appear to be intended— (i) to intimidate or coerce a civilian population; (ii) to influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion; or (iii) to affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping; and (C) occur primarily within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States. |

Per Capita Threshold

Some may be concerned that FEMA might not recommend a major disaster declaration to the President for an act of terrorism because the incident does not meet or exceed the $1.42 per capita threshold. Using this threshold, FEMA may not recommend a declaration for an incident with a high number of casualties but limited damage to public infrastructure. For example, the Orlando Pulse nightclub attack killed 49 people but caused little damage to public property. Almost all of the damage was to the nightclub.62 In addition, damages to businesses are generally not considered when formulating the per capita threshold which is based on public sector damage.

Even if there is substantial damage to public infrastructure, some populous states may have difficulty meeting the per capita threshold. For example, in 2013 Illinois communities were denied federal assistance after a string of tornados devastated rural communities of the state. The storms caused significant damages to the rural communities but, given the state's large population, there was not enough damage to meet the per capita threshold.63

Some might argue that loss of life should play a larger role when FEMA makes declaration recommendations. Others might question whether terror attacks with limited public infrastructure damage—while devastating in their own right in terms of loss of life and the impact they can have on national morale—cause enough damage to warrant a major disaster declaration.

If Congress is concerned that the per capita threshold may prevent state and local governments from receiving a major disaster declaration for a terror attack, Congress could require FEMA to consider factors beyond damages to public infrastructure when formulating its recommendation to the President. One potential assessment tool is the value of statistical life (VSL) which assigns a monetary value to each fatality caused by the given incident. For example, the U.S. Department of Transportation uses $9.1 million as the VSL when evaluating risk reduction.64 If this VSL amount was applied to the Orlando attack, the 49 fatalities would amount to roughly $446 million in damages.

Proponents might argue that evaluating a terror attack with VSL would provide objective criteria for making recommendations as to whether an incident warranted federal assistance. Others might question if altering the per capita threshold is necessary. They may point out that the per capita threshold is used solely by FEMA to make recommendations. Also, FEMA already considers damage to homes and rental properties. As noted previously, the ultimate decision to grant federal assistance for a major disaster rests solely with the President.

Furthermore, the per capita threshold is designed to evaluate a state's capacity to respond to an incident. It could be argued that highly populated states should be able to fund their recovery without federal assistance because they have a higher tax base on which to draw. According to this view, adjusting the per capita threshold or applying additional factors would be unnecessary.

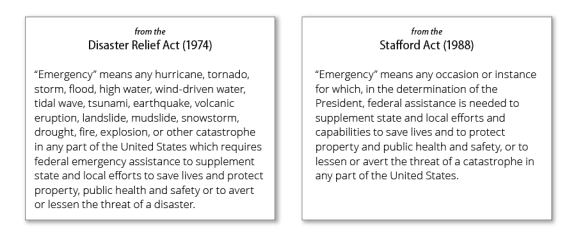

Emergency Declarations for Acts of Terrorism

Whereas Congress sought to limit the President's authority to issue major disaster declarations for human-caused incidents under the Stafford Act, the inverse might be said about emergency declarations. As demonstrated by Figure 4, the definition of an emergency in the Disaster Relief Act of 1974 included a specific list of incidents eligible for an emergency declaration. The amended definition eliminated the list and defined emergency more broadly.

|

Figure 4. Emergency Definition Comparison of Disaster Relief Act and the Stafford Act |

|

|

Source: 42 U.S.C. §5122. |

It could be argued that the amended definition provides the President with a great deal of discretion to issue an emergency declaration in response to acts of terrorism. And as mentioned previously, FEMA does not use the per capita threshold formula to make emergency declaration recommendations to the President. To some, the broad definition and lack of a per capita formula make emergency declarations more suitable for certain types of terror attacks such as mass shootings.

Consequently, some may argue that there is no need to change the Stafford Act to make it easier for "soft target" attacks to receive a major disaster declaration because it is relatively easier to obtain an emergency declaration.65

Even so, some might see the decision to issue an emergency declaration as arbitrary and question how state capacity is determined. For example, in a news release in response to the denied emergency declaration for the Orlando shooting, Governor Rick Scott stated

It is incredibly disappointing that the Obama Administration denied our request for an emergency declaration. Last week, a terrorist killed 49 people, and wounded many others, which was the deadliest shooting in U.S. history. It is unthinkable that President Obama does not define this as an emergency. We are committing every state resource possible to help the victims and the community heal and we expect the same from the federal government.66

The press release also provided links to other incidents that were approved for emergency declarations, including President Obama's 2009 inauguration, the 2016 Flint Water crisis, the Massachusetts water main break in 2010, and the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, among others. Some might question why these incidents warranted emergency declarations but the Pulse nightclub shooting did not.

Proponents of changing the Stafford Act may also argue that, even if an incident receives an emergency declaration, the scope of the assistance is limited compared to a major disaster. For one, assistance is primarily provided to governmental entities under an emergency declaration. Individuals may receive some temporary housing assistance (which may not be applicable if the incident does not impact people's homes) and other forms of assistance such as Other Needs Assistance, which is a grant to households for necessary items damaged or destroyed by the incident, under Section 408 of the Stafford Act. But assistance to those experiencing mental health problems, generally addressed by FEMA's Crisis Counseling program, is not available under an emergency declaration. Further, as mentioned previously, SBA disaster loans are generally only available to private non-profit organizations under an emergency declaration.

If Congress is concerned that emergency declarations would not provide enough assistance in response to certain types of terror attacks, it could consider expanding the types of assistance potentially available for these incidents. The expanded assistance could be tied to all emergency declarations, or designed exclusively for acts of terror. In addition, Congress could require the SBA to provide the full range of disaster loans if an emergency were declared for an act of terror.

SBA Disaster Loans and CDBG Disaster Assistance

SBA Disaster Loan Program

This section examines how the SBA Disaster Loan programs might be used to assist businesses, individuals, and households following a terrorist attack. The section also examines a potential alternative source of federal funding that has been used to assist businesses negatively impacted by a terror attack.

As previously mentioned, SBA disaster loans are usually the only type of federal assistance available to businesses affected by a terror attack. There are potentially four scenarios where the SBA Disaster Loan Program could be used to support business recovery activities following a terror attack. These include two types of presidential declarations as authorized by the Stafford Act, and two types of SBA declarations authorized by the Small Business Act.67 In addition to providing disaster loans for businesses, some of these declarations also make disaster loans available to individuals and households. As demonstrated below, the type of declaration determines what loans types are made available:

- Major Disaster or Emergency Declaration Authorizing PA and IA. The President issues a major disaster declaration, or an emergency declaration, and authorizes both IA and PA under the authority of the Stafford Act. When the President issues such declarations, Home and Personal Property Disaster Loans, and Business Physical Disaster Loans become available to homeowners, renters, businesses of all sizes, and nonprofit organizations located within the disaster area. Home and Personal Property Disaster Loans, and Business Physical Disaster Loans can be used to repair and replace items and structures damaged by an attack. EIDL may also be made available under this declaration to provide loans to businesses that suffered substantial economic injury as a result of the incident.

- Major Disaster or Emergency Declaration Authorizing PA Only. The President makes a major disaster declaration or emergency declaration that only provides the state with PA. In such a case, a private nonprofit entity located within the disaster area that provides noncritical services may be eligible for a SBA physical disaster loan and EIDL.68

Disaster loans would not available to renters and homeowners under this type of declaration. In addition, Business Physical Disaster Loans, and EIDLs are generally not made available to businesses (unless they are a private nonprofit entity) when the declaration only provides PA.

As mentioned previously, there are two scenarios under which SBA disaster loans could be provided in response to a terror attack without the issuance of presidential disaster declaration:

- Gubernatorial Request for Assistance. Under this scenario, the SBA Administrator issues a physical disaster declaration in response to a gubernatorial request for assistance.69 Under this type of declaration, SBA disaster loans would be available to eligible homeowners, renters, businesses of all sizes, and nonprofit organizations within the disaster area or contiguous counties and other political subdivisions. EIDL would also be available under this type of declaration.

- Gubernatorial Certification of Substantial Economic Injury. The SBA Administrator may issue an EIDL declaration when SBA receives a certification from a governor that at least five small businesses have suffered substantial economic injury as a result of a disaster. This declaration may be offered only when other viable forms of financial assistance are unavailable. Small agricultural cooperatives and most private nonprofit organizations located within the disaster area or contiguous counties and other political subdivisions are eligible for SBA disaster loans when the SBA Administrator issues an EIDL declaration.

These types of loans, however, may not be used to repair damages resulting from a terror attack. Rather, loan proceeds can only be used for working capital necessary to enable the business or organization to alleviate the specific economic injury and to resume normal operations. For example, a business may suffer a dramatic decline in its business operations and revenue stream or have difficulty obtaining materials as a result of a terror attack.

As illustrated above, the type of loans that are made available to individuals, homeowners, and businesses largely depends on declaration type.70 Some observers might be concerned that certain disaster loans may not be available following a terrorist attack. In the view of those observers, Congress could consider amending existing programs by making all SBA disaster loan types available following a terror attack for certain declarations. For example, Congress might make EIDL, home and business disaster loans available for major disaster and emergencies that only provide PA.

Community Development Block Grants71

Another source of potential assistance to businesses is Department of Housing and Urban Development's (HUD's) Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program. The CDBG program provides grants to states and localities to assist their recovery efforts following a presidentially declared disaster. Generally, grantees must use at least half of these funds for activities that principally benefit low- and moderate-income persons or areas. The program is designed to help communities and neighborhoods that otherwise might not recover due to limited resources. While the SBA Disaster Loan Program is automatically triggered by a presidential disaster declaration, CDBG is not. Instead, Congress has occasionally addressed unmet disaster needs by providing supplemental disaster-related appropriations for the CDBG program. Consequently, CDBG is not provided for all major disasters, but only at the discretion of Congress.

Congress has authorized supplemental appropriations of funds in response to terror attacks through CDBG. For example

- In 1995, following the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building attack in Oklahoma City, OK, Congress appropriated $12 million in supplemental CDBG funding to the City of Oklahoma City. Funds were to be used to establish a revolving loan fund only for the purposes of making loans to carry out economic development activities that would primarily benefit a designated area in the city impacted by the bombing.

- On November 26, 2001, two months following the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, Congress appropriated $700 million in CDBG supplemental funding to the state of New York for assistance to properties and businesses damaged by, and for economic revitalization related to the terror attack.72

- On January 10, 2002, Congress followed that initial appropriation with a second appropriation of $2 billion in CDBG assistance to the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC) to be used to, among other things, reimburse businesses and persons for economic losses, including funds to reimburse tourism areas adversely impacted by the attacks.73

- On August 2, 2002, Congress appropriated an additional $783 million to the state of New York through the LMDC in cooperation with the City of New York in support of the city's economic recovery efforts. Funds were used to provide financial assistance to properties and businesses, including the redevelopment of infrastructure, and for economic revitalization activities.74

Most federal disaster assistance programs are funded through annual appropriations. This generally ensures that the programs have funds available when an incident occurs. As a result, these programs can provide assistance in a relatively short period of time. For example, a July 2015 SBA Office of Inspector General (OIG) study found that SBA's processing time for home disaster loans averaged 18.7 days and application processing times for business disaster loans averaged 43.3 days.75

CDBG disaster assistance, on the other hand, is funded through supplemental funding. In general, Congress only provides supplemental funding when disaster needs exceed the amount available through annual appropriations. This typically only occurs when a large incident takes place, such as Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy. This is because Congress must debate and pass supplemental funding. Additionally, funding for CDBG disaster assistance is not available for all incidents.

Some might argue the necessity for supplemental funding would preclude smaller terror incidents from receiving CDBG disaster assistance. Others might be concerned that assistance is not timely. For example, an appropriation for CDBG disaster assistance was enacted on June 3, 2008. The allocation date for the CDBG disaster assistance was September 11, 2008—three months after the enacted appropriation.

One potential option would be to fund CDBG disaster assistance through annual appropriations. Doing so would create an account with funds that could be made immediately available to help expedite CDBG disaster assistance. Congress could examine strategies to make CDBG disaster assistance available to businesses that suffered damage as a result of a terrorist incident. The assistance could be triggered by a major disaster declaration, an emergency declaration, or both.

Critics of the above policy option might argue that if this approach were used, it would be necessary to determine under what situations CDBG disaster assistance would be released. Critics may also argue that determinations for CDBG disaster assistance are made by Congress. Changing the process to one based on annual appropriation might shift the determination to a (relevant) federal agency. Similarly, as mentioned previously, CDBG disaster assistance is typically only available for large-scale incidents. Creating a permanent CDBG program for disaster assistance might provide a gateway for smaller incidents to receive CDBG disaster assistance. This, in turn, might lead to increased federal expenditures for disaster assistance.

Expanded FEMA Assistance

Some may question whether the Stafford Act is the appropriate authority for providing assistance to terror incidents with high number of casualties and limited damage. The assistance provided under the Stafford Act is primarily for recovery purposes (i.e., repairing and replacing damaged buildings and infrastructure). Under the existing Stafford Act authorities the assistance FEMA might provide would be the Other Needs Assistance (ONA) grant program that can be used to pay funeral expenses. And even in those cases, there may be private insurance already meeting those needs. Arguably, ONA could be expanded to begin to cover other costs following a death in the family and an expansion of FEMA coverage of related emergency health care costs might be helpful to the uninsured affected by a terrorist event. Similarly, a terrorist event could also be the trigger for expanded Disaster Unemployment Assistance benefits. But beyond those areas, little of the FEMA catalogue of assistance would apply beyond the programs already being employed.

Concluding Observations

This report has outlined several different approaches, both definitional and administrative, that could fill in perceived gaps that have been forecast based on possible events juxtaposed against current policy parameters. One view argues that the Stafford Act should be amended to assure that terrorist attacks are eligible for major disaster assistance. Another view is that the Stafford Act is a flexible instrument that has assisted states and families and individuals through a myriad of unanticipated situations. According to this view, the Stafford Act's existing structure is sufficient to meet the potential terrorism challenges that may lie ahead.

The selected approach will likely be influenced by two factors: (1) impact on federal costs, and (2) personal views concerning the appropriate nature of the federal government's role in addressing terrorism. Some might be concerned that amending the Stafford Act to assure that soft target and nonconventional terror attacks are eligible for major disaster assistance might, in their view, inappropriately shift the primary financial burden for addressing terrorism costs from the states to the federal government. Others might see these costs as minimal, particularly compared to the costs of natural disasters, such as those from major hurricanes. With respect to the appropriate role for the federal government in addressing terrorism costs, some might argue that the federal government should provide assistance for all instances of terrorism, even if those costs could be adequately handled by the state. Others might argue that federal assistance should be provided only in those cases where state and local government financial capacity is lacking.

Appendix. Examples of Request and Denial Letters

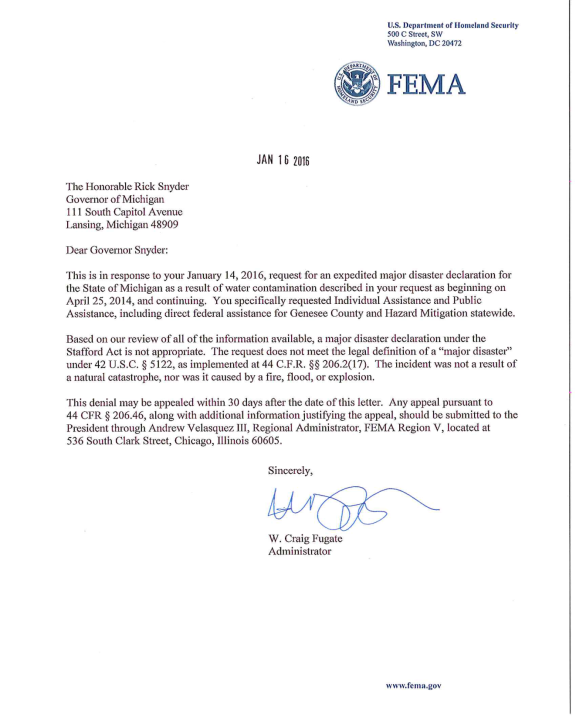

|

Figure A-1. FEMA Denial Letter: Flint Water Contamination Incident January 16, 2016 |

|

|

Source: Letter from W. Craig Fugate, FEMA Administrator, to Rick Snyder, Governor of Michigan, |

|

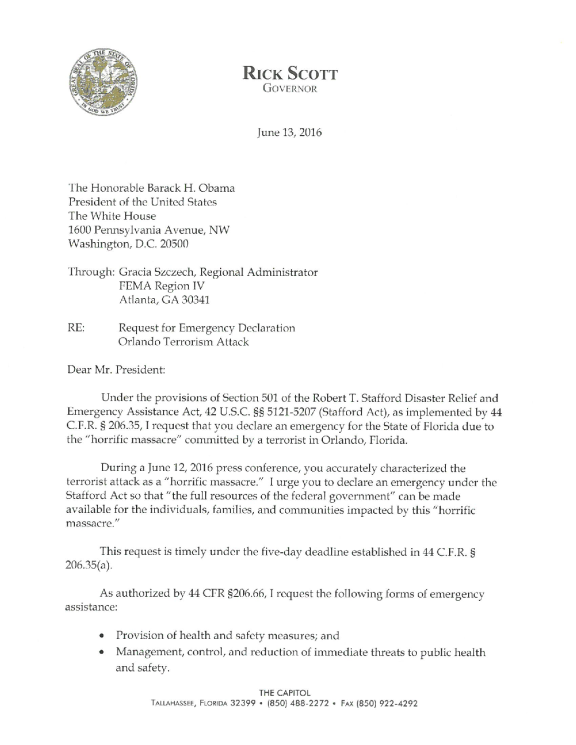

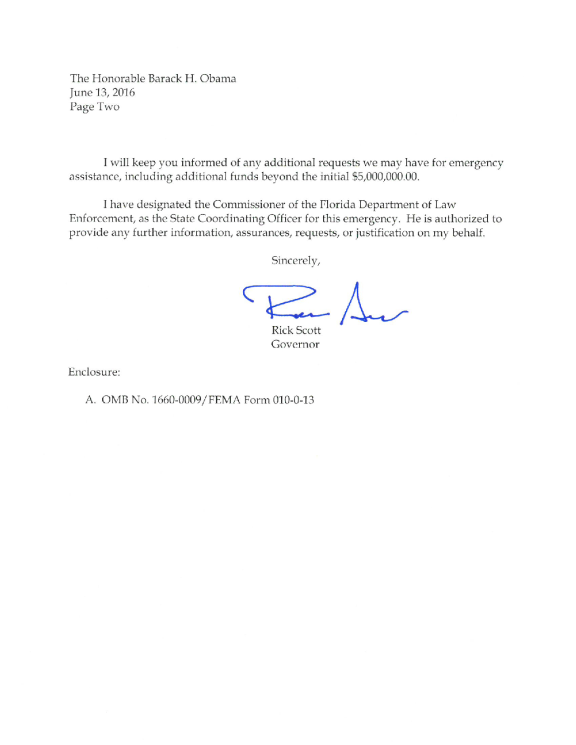

Figure A-2. Governor Scott Emergency Declaration Request: June 13, 2016 |

|

|

|

Source: http://www.flgov.com/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/OTA.pdf. |

|

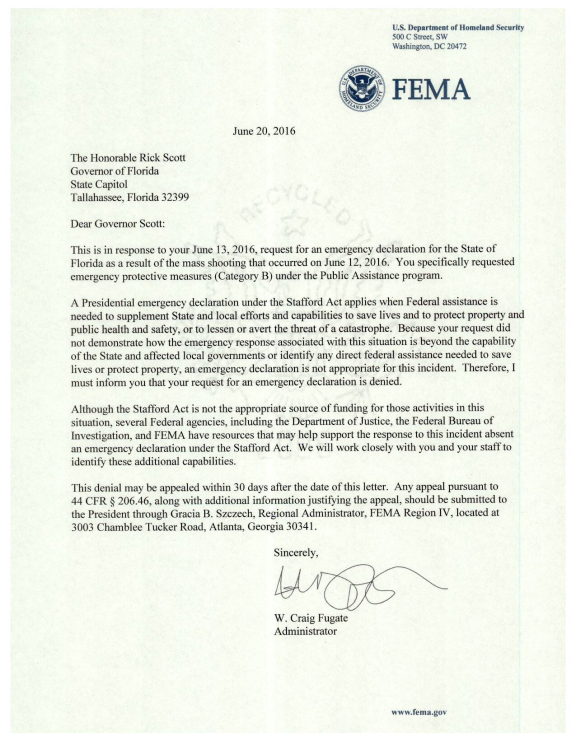

Figure A-3. FEMA Denial Letter: Pulse Nightclub Shooting June 20, 2016 |

|

|

Source: http://www.flgov.com/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/FEDDENIAL.pdf. |