Introduction

Members of Congress and Administrations have periodically considered reorganizing the federal government's trade and development functions to advance various U.S. policy objectives. In the 115th Congress, these issues have come to the fore in the context of development finance. "Development finance" is commonly used to describe government-backed financing to support private sector capital investments in developing and emerging economies. It can be viewed on a continuum of public and private support, situated between pure government support through grants and concessional loans and pure commercial financing at market-rate terms.

Development finance institutions (DFIs) are specialized entities that supply such finance. In the United States, the primary provider of development finance is the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), but other agencies, such as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), also provide development finance.

President Trump renewed the debate over the future of U.S. development finance at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) CEO Summit in Danang, Vietnam in November 2017, where he announced that the United States is committed "to reforming our development finance institutions so that they better incentivize private sector investment in your economies and provide strong alternatives to state-directed initiatives that come with many strings attached."1

The Trump Administration's National Security Strategy, released in December 2017, identified modernizing U.S. development finance tools as a priority to advance U.S. global influence. It noted that, "[w]ith these changes, the United States will not be left behind as other states use investment and project finance to extend their influence."2 Competition for influence with China, which is a major supplier of development finance, especially appears to be a prominent driver of the Administration's interest in development finance reform. Moreover, potential reorganization of the executive branch has been a broader interest of the Trump Administration.3 The President's FY2019 budget proposed the consolidation of OPIC and other agency development finance functions, specifically noting the Development Credit Authority (DCA) of USAID, into a new U.S. development finance agency to advance a number of U.S. policy objectives.4

In February 2018, two proposed versions of the Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development (BUILD) Act, H.R. 5105 in the House and S. 2463 in the Senate, were introduced on a bipartisan, bicameral basis to create a new U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (IDFC). The nearly identical bills in the House and Senate would consolidate all of OPIC's functions and the Development Credit Authority (DCA), enterprise funds, and development finance technical support functions of USAID. A primary difference between the bills is that the House version would authorize the new DFI for seven years, while the Senate version would authorize it until September 30, 2038.

The Trump Administration issued a statement strongly supporting the BUILD Act, noting that it was broadly consistent with the Administration's goals and FY2019 budget proposal. At the same time, the Administration called for some modifications to the bills to enhance the proposed DFI's alignment with national interests and institutional linkages, as well as to address risk management and other concerns.5 Stakeholders differ in their views of particular aspects of the DFI proposal and certain issues remain open questions.6

While some executive branch reorganizations can happen administratively, the changes contemplated here would likely require changes to U.S. law.7

Background

Overview of Development Finance Institutions

At the bilateral level, national governments can operate DFIs. The United Kingdom was the first country to establish a DFI in 1948. Many countries have followed suit. These DFIs are typically wholly or majority government-owned. They operate either as independent institutions or as a part of larger development banks or institutions. Their organizational structures have evolved, in some cases, due to changing perceptions of how to address identified development needs in the most effective way possible. Unlike OPIC, other bilateral DFIs tend to be permanent and not subject to renewals by their countries' legislatures.

DFIs also can operate multilaterally, as parts of international financial institutions (IFIs), such as the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private sector arm of the World Bank. They can operate regionally through regional development banks as well. Examples of these banks include the African Development Bank (AfDB), Asian Development Bank (AsDB), European Bank for Reconstruction & Development (EBRD), and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).8

The primary role of nearly all DFIs is promoting economic development by supporting foreign direct investment (FDI) in underserved types of projects, regions, and countries; undercapitalized sectors; and countries with viable project environments but low credit ratings (see text box). DFIs use a range of financial instruments to support private investment in development projects; depending on the DFI, these may include equity, direct loans, loan guarantees, political risk insurance, and technical assistance. Varied as they may be, DFIs aim to be catalytic agents in promoting private sector investment in developing countries. Their support is aimed to increase private sector activity and public-private partnerships that would not happen in the absence of DFIs because of the actual or perceived risk associated with the activity.

In providing support for development, DFIs typically pursue "additionality," that is, limiting their support to circumstances when commercial financing for a project is not available on commercially viable terms in order to complement, not compete with, the private sector. The presence of DFIs is considered to provide a guarantee of a long-term commitment to development that private capital would otherwise not bear on its own.9

At the same time, DFIs generally are market-oriented in their project support, such as in the fees they charge. They generally aim to be financially sustainable or profitable, investing in projects that generate returns. As such, DFIs often have a double bottom line of development impact and financial sustainability or profitability—prompting debate within the development community about the extent to which these goals are complementary or in tension.10

DFIs vary in the size of their activities, as well as their portfolio compositions—whether by financial instrument, geographic region, or economic sector. They often cofinance investment projects with each other, both at the multilateral and bilateral level. Such financing pools additional funds and diversifies risks across DFIs, such as for certain large-scale infrastructure projects that may be too big and risky for one DFI to finance alone. Unlike government-backed export financing, no international rules govern DFIs' investment financing activities.11

|

Examples of DFI Activity Energy Investment. Guinea experiences persistent power supply issues. Less than one-third of the population has access to electricity. Under the Power Africa initiative, OPIC is supporting the development of a 50 megawatt power plant in Guinea's capital of Conakry to help increase baseload power in the country. Electricity generated from the plant is to be sold to the public utility company under a five-year power purchase agreement. OPIC is providing $50 million in financing and $50 million in political risk insurance for the project. Alongside OPIC, the UK's development finance institution, CDC (formerly known as the Commonwealth Development Corporation), is providing a $39 million loan for the project. The project sponsor, Endeavour Energy, an Africa-focused power company owned by the investment firm Denham Capital, is providing $32 million in equity investment for project. The support extended by OPIC and CDC reportedly helped bring the project to a financial close. Financial Services Investment. Access to credit for small businesses in India is viewed as a constraint on India's economic development, particularly for women-owned businesses. About a quarter of India's 3 million women-owned businesses, which employ about 8 million people, are able to obtain the credit they need to support their businesses. In 2017, OPIC and Wells Fargo agreed with YES Bank, India's fourth-largest private sector bank, on support to expand access to credit for women-owned businesses and small businesses in low-income states in India. OPIC is to provide $75 million in financing and up to $75 million in syndicated financing jointly arranged by Wells Fargo and OPIC to YES Bank. The World Bank's IFC is also providing financing support for mobilizing capital for women entrepreneurs. Source: OPIC, "OPIC Commitments to Power Africa Have Reached $2.4 Billion to Date," press release, March 1, 2018; OPIC, "Active Projects"; CDC, "CDC Announces U.S. $39 Million Investment in 50MW Tè Power Plant in Guinea," press release, March 28, 2018. OPIC, "YES Bank Partners with OPIC and Wells Fargo to Support Financing of Women Entrepreneurs and SMEs," press release, July 13, 2017. |

For decades, the major players in development funding were international financial institutions and bilateral government donors. By the end of the 1980s, private capital flows began to accelerate, and bilateral DFIs, including those of the United States and European countries, became more active in development finance. With their growing economic power, emerging economies increasingly are now also major suppliers of such finance.

It is difficult to find centralized, comprehensive, and comparable sources of information on DFI activities. According to one study, the amount of financing committed by some major DFIs grew from about $10 billion in 2000 to nearly $70 billion 2014.12 That year, DFI annual commitments for private sector investment in developing countries were comprised of 40% by multilateral DFIs (including the IFC and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency, MIGA); 35% by bilateral DFIs (15 European DFIs, OPIC, and Japan's DFI); and 25% by regional finance institutions.13 By many accounts, the magnitude and scope of China's development finance outsizes that of other historical suppliers of development finance. For example, at the end of 2016, assets of the China Development Bank (CDB, discussed below) stood at 14.3 trillion yuan ($2.3 trillion).14 Measured by assets, the CDB is larger than the World Bank's IFC, whose assets totaled $90.4 billion in 2016.15

The growth of direct investment flows has outpaced that of official development assistance (ODA) provided by the 29 members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC), which includes the United States. As ODA has decreased and FDI to developing countries has increased, development finance has become more prominent as a way to encourage private investment to go to undercapitalized areas. For example, global investments in infrastructure total about $2.5 trillion a year, but do not meet demand, such as in developing countries experiencing population growth, expanding economies, and industrialization. Based on current trends, there is a shortfall in infrastructure investment of about $350 billion a year. That gap triples if the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are taken into account.16

Key U.S. Government Agencies in Development Finance

OPIC and USAID are at the center of the current development finance reorganization debate. While outside of the scope of this report, it is important to note that the United States also supports development finance at the multilateral and regional level through its contributions to entities such as the IFC and various regional development banks.17 This section provides an overview of OPIC and USAID and, for context, also briefly discusses some other agencies that employ tools similar to these agencies but generally for different purposes.

Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC)

OPIC is the official U.S. DFI. Established by the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended (FAA; 22 U.S.C. §2191 et seq.), it officially began operations in 1971 (see text box). It seeks to promote economic growth in developing economies by providing, on a demand-driven basis, project and other investment financing for overseas investments and insuring against the political risks of investing abroad, such as currency inconvertibility, expropriation, and political violence. OPIC provides loans, guarantees, and political risk insurance for qualifying investments. OPIC does not take equity positions in investment funds (pools of capital that make direct equity and equity-related investments in companies). Rather, OPIC supports investment funds through financing. OPIC also generally does not conduct technical assistance. Congress most recently extended OPIC's authority to conduct its programs through September 30, 2018 (P.L. 115-141).

Although OPIC uses financial tools and is oriented toward private enterprise, it is a foreign assistance tool. The FAA requires it to conduct its work under the Secretary of State's policy guidance. By statute, OPIC is governed by a 15-member Board of Directors, with 8 "private sector" Directors (with requirements for small business, labor, and other representation) and 7 "federal government" Directors (including the OPIC President, USAID Administrator, U.S. Trade Representative, and a Labor Department officer).

|

OPIC's Historical Origins and USAID Ties Federal support for U.S. private investment overseas predates OPIC's official creation. It started after World War II with the Marshall Plan, which included political risk insurance for U.S. investments in Europe. USAID absorbed these functions when it was established in 1961. During the early 1960s, Congress called for expanding USAID's investment guarantee program and increasing private capital flows to developing countries to support economic development.18 In his 1969 message to Congress on aid, amid congressional disillusionment about U.S. foreign aid, President Nixon recommended creating OPIC to assume USAID's investment guaranty and promotion functions, with "businesslike management of investment incentives" and a new emphasis on self-sufficiency and risk-management. Members of Congress debated the merits of creating OPIC. Supporters viewed the business-like nature of OPIC, as a partnership between private management and official policymakers, as beneficial. Critics expressed concern about removing from USAID an important tool of foreign aid and giving it to an organization governed by business concerns. While some thought that creating a small specialized organization would bring operational advantages, others were skeptical about the potential for increasing costs and adding to the federal bureaucracy. For some, a rationale for OPIC was that countries such as France, Germany, and the UK used comparable entities to promote private investment in development. Ultimately, support for OPIC prevailed. |

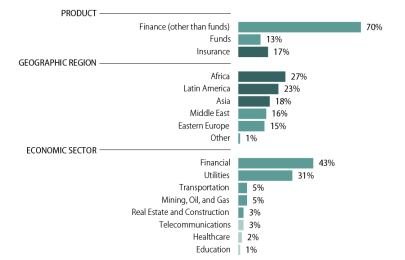

In FY2017, OPIC reported authorizing $3.8 billion in new commitments for 112 projects, and its exposure reached a record high of $23.2 billion (see Figure 1). OPIC estimated that it helped mobilize $6.8 billion in capital and supported 13,000 new jobs in host countries that year.

OPIC's activities are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. Projects must meet certain requirements, including that investors must have a meaningful U.S. connection in order to be eligible for OPIC support. OPIC must take certain considerations into account when determining whether to support a project (e.g., U.S. economic impact, environmental impact, worker rights, and development impact on country of investment destination). Projects are subject to certain limitations as well. The FAA directs OPIC to operate "on a self-sustaining basis, taking into account ... the economic and financial soundness of projects" and with regard to risk management principles. OPIC charges interest, premia, and other fees for its services to cover the cost of its operations. It assesses credit and other risks of proposed transactions, monitors commitments, and guards against potential losses through reserves.19

Unlike USAID (discussed below), OPIC's international presence is limited. OPIC states that it relies on expertise of other U.S. government agencies at U.S. missions abroad.

|

|

Source: CRS, based on data from OPIC's FY2018 congressional budget justification (CBJ). Notes: OPIC's portfolio composition by product is based on OPIC's portfolio on March 31, 2017 ($22.5 billion). The CBJ did not specify the date of exposure used for the portfolio breakdown by region and sector. Finance involves OPIC support through direct loans and loan guarantees. Funds are a specific type of finance that partners OPIC debt with private equity from a private source. |

U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)

USAID has been actively involved in providing development finance in various forms since its establishment in 1961.20 In its first 20 years, provision of development loans to developing country governments, mostly for infrastructure projects, made up a significant proportion of its operations. In the 1980s, with the Reagan Administration's Private Enterprise Initiative, the agency greatly expanded efforts to develop the private sector in developing countries, including lending to micro, small, and medium business. At this time, the agency possesses a range of development finance capacities:

The Development Credit Authority (DCA), managed by the DCA office in the Bureau for Economic Growth, Education, and the Environment (E3), supports bank lending for specific development purposes by employing the promise of U.S. government repayment typically of up to half of each loan in case of default. By lessening the liability to the lending bank, these partial loan guarantees aim to encourage banks to make loans for purposes and clients that they may have previously avoided as commercially unviable or too risky. In FY2016, nearly half of DCA guarantees issued by value (47%) promoted activity in energy and 26% focused on agriculture, while fully half of the value of guarantee assistance went to sub-Saharan Africa and 25% to Asia.

Enterprise Funds are private sector-managed entities established with the purpose of stimulating free market economic growth. Following a model of venture capital funds, they featured equity investment as a significant feature of their activities. The funds also, in varying degrees, provide support for mortgage securitization, microfinance, equipment leasing, credit cards, and other efforts to introduce new financial instruments. Ten such funds, supported by $1.2 billion in taxpayer assistance, were launched in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union in response to the fall of communist governments and economies in the late 1980s to early 1990s. Two enterprise funds have been established in recent years in Tunisia and Egypt.21

Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprise (MSME) Finance and Technical Support. Since the 1960s, USAID has provided financial and technical assistance to entrepreneurs through a range of intermediaries—cooperatives, commercial banks, credit unions, business associations, and other nongovernmental organizations (NGOs)—that offer loans and business development services. In addition, the agency has been instrumental in promoting policy reforms that facilitate a legal environment conducive to private sector lending in the developing world. For example, to help small and medium enterprises (SME) in rural areas of Nicaragua with limited access to finance and investment capital, the Enterprise and Employment Program (2009-2013) provided direct technical assistance and training to banks so they could create SME lending programs. The USAID mission also supported development of a new credit scoring tool to assist lenders in making better lending decisions, leading to $39 million in new lending.22

Catalyzing Private Sector Finance. For many decades—from the commercialization of contraceptive production and distribution in support of family planning, as well as the sale and manufacturing of oral rehydration therapy (ORT), in the 1980s, to the public-private partnerships of the Global Development Alliance in the early 2000s—USAID has sought to increase its development impact by leveraging the resources of the private sector.23 In drawing the financial support of the private sector, especially U.S. business, the agency has exploited its "convening power" as the leading development agency in the U.S. government with a mission presence in dozens of countries and expertise in the full range of development sectors.

Efforts to catalyze private sector finance are ongoing throughout the agency, at both mission and central bureau levels. In 2017, the USAID mission in Pakistan established three equity funds with a contribution of $24 million for each fund, matched or exceeded by private investors to help the expansion of small and medium business in that country. In Ethiopia, a $6 million Innovation Investment Fund has attracted private sector cost sharing of about $25 million in support of medium to large-scale businesses operating within pastoral areas.24

Launched in 2014, the Africa Bureau's Private Capital Group for Africa (PCGA) works to attract private capital to support development-related projects by identifying profitable transactions. With a team based in South Africa, it seeks to facilitate transactions by eliminating risk and other barriers to finance; to improve cities' ability to finance and service debt for public service projects; and to encourage the use of South African pension funds—a major source of finance capital—in development projects.25 The USAID Global Health Bureau's Center for Accelerating Innovation and Impact is exploring ways of funneling private sector finance to meet global health needs, including a pilot program to provide working capital to independent pharmacies in order to improve access to medicine in Africa.26

In 2015, a new Office of Private Capital Development and Microenterprise (PCM) was established in the E3 Bureau specifically to find new ways to mobilize private sector capital and expertise in support of development and facilitate USAID mission activity in this area. It has, for example, partnered with CrossBoundary Energy to pilot a new model of financing solar installations for enterprises in Africa and, working with Sarona Asset Management, it is piloting a currency risk mitigation tool that may help attract more institutional investment (pension funds, insurance companies) in development programs.27

U.S. Government Context

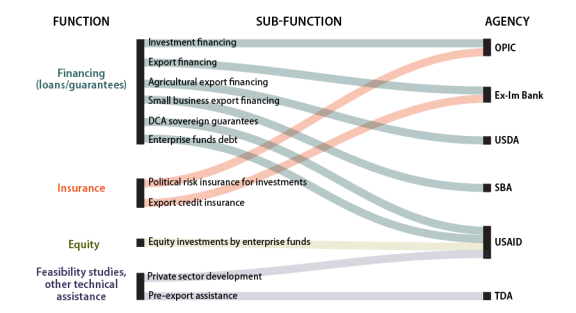

In addition to OPIC and USAID, some other U.S. government agencies administer functions similar to development finance but generally for different purposes (see Figure 2).

Several agencies also provide financing and insurance, notably the Export-Import Bank of the United States (Ex-Im Bank). Known as the official U.S. export credit agency (ECA), Ex-Im Bank helps finance U.S. exports of goods and services, not U.S. private sector investment.28 Unlike OPIC and USAID, Ex-Im Bank is not authorized under the FAA, but rather has its own charter, the Export-Import Bank Act of 1945, as amended (12 U.S.C. §635 et seq.). It focuses on supporting U.S. exports to contribute to U.S. employment, although its activities can have U.S. foreign policy implications. Other agencies, such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Small Business Administration (SBA), also provide export financing, but in a more limited manner and specific to their constituencies, that is, for U.S. exports of agricultural products and exports by U.S. small businesses, respectively.29

The U.S. Trade and Development Agency (TDA) is among the agencies that also provide technical assistance.30 Authorized under the FAA (22 U.S.C. §2421), TDA has a dual mission in supporting both U.S. foreign policy and trade objectives, as its name would suggest. TDA aims to link U.S. businesses to export opportunities overseas, including by infrastructure development, that lead to economic growth in developing and middle-income countries. TDA funds pre-export activities, such as feasibility studies and pilot projects.

Comparison to Selected Foreign Bilateral DFIs

This section highlights selected foreign bilateral DFIs (see Appendix for comparative table).

Europe. The most direct counterparts and perhaps most easily comparable DFIs to OPIC are arguably the bilateral European DFIs that are members of the Association of European Development Finance Institutions (EDFI).31 Unlike OPIC, European DFIs can take equity positions and offer some technical assistance.32 However, they do not offer political risk insurance as OPIC does.33 Collectively, the EDFI members' portfolios reached $45 billion in 2015, more than double OPIC's $20 billion portfolio in 2015—through OPIC's portfolio was larger than that of any individual EDFI member. Like OPIC, the European DFIs overall tend to be most concentrated in Africa and Latin America. The UK's DFI is distinct in its exclusive focus since 2012 on Africa and South Asia, which it says allows it to focus on regions where the world's poorest people live. Financial services was the largest sector of support for EDFI members collectively, as for OPIC. Also, comparable to OPIC's focus on economic and social governance in its support of projects, EDFI states that its members have adopted a "shared set of principles for responsible financing, which underlines that respect for human rights and environmental sustainability is a prerequisite for financing by EDFIs."34

China. China, which has become a major, if not the leading, global supplier of development finance, provides development finance through several entities. At the national level, the key entity is China Development Bank (CDB), a state-owned "policy bank" that conducts development finance for specific purposes. More recently, China established two new multilateral development banks, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the New Development Bank (NDB), also known as the BRICS development bank.35 Data on China's development finance activities are limited and estimates vary widely, but China may have provided upwards of $100 billion in financing in recent years.36 China's development finance activities have been prominent in their linkages to major Chinese national efforts, notably the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).37 Announced in 2013, the BRI is China's vision for economic connectivity across Asia, Africa, Europe, and other parts of the world over land and sea routes, including major financing for infrastructure. It is unclear how much funding China plans to commit to BRI, with reports of Chinese investments potentially reaching $4 trillion, if not more.38 A number of China's financial institutions are involved in BRI.39 CDB reportedly has provided support for 100 BRI projects totaling $30 billion.40 Much of China's support for development is directed toward infrastructure and energy projects, with involvement of Chinese firms, including state-owned enterprises (SOEs). China's development finance activity in Asia, Africa, and Latin America has been a focal point for development finance watchers, but its range is broader, particularly in light of the BRI.

China's support for overseas investment often is not associated with the same environmental and social standards to which OPIC and many other DFIs subscribe. On one hand, some recipient governments may welcome that Chinese support is not as conditional as that of other DFIs on environmental and social requirements. At the same time, projects supported by China have raised questions about environmental and social risks, including displacement of large populations due to major infrastructure work, such as hydropower projects.41 China's financing also appears to take on risks that other DFIs may not want to take. Many of the countries in which China invests have high debt-to-GDP ratios, raising questions about debt sustainability.

Japan. Japan provides development finance through its Japanese Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC), which is wholly owned by the Japanese government. JBIC was established in 2012, combining Japan's investment and export financing functions. JBIC characterizes itself as a "policy-based institution" that conducts its operations based on policy needs in response to economic and financial situations domestically and internationally. A major focus of JBIC's activities is projects related to securing medium- to-long-term supplies of energy and mineral resources. The composition of JBIC's commitments by financial instrument type has changed over time. In earlier decades, export loans comprised the majority of JBIC's commitments, while presently overseas investment loans represent the bulk of new commitments. By geographic region, Asia represented the largest share of JBIC's FY2016 commitments, followed by North America and Europe.42

Potential Issues for Congress

This section discusses issues raised by the potential reorganization of U.S. government development finance functions. While many of the issues draw from the Administration's development finance reform proposal and the BUILD Act bills, the discussion has applicability to other proposals Congress may consider for development finance reorganization.

Modifying Development Finance Functions

At the outset, Congress may consider the rationales for and against the United States being involved in development finance and modifying that involvement.

Supporters of "upgrading" OPIC assert that outdated rules, limited resources and authorities, and lack of a long-term authorization constrain the agency. They have opposed proposals to eliminate OPIC or to consolidate it into a broader trade agency.43 They argue that OPIC helps fill in gaps in private sector support that arise from market failures, as well as helps U.S. firms compete against foreign firms backed by foreign DFIs for investment opportunities—thereby advancing U.S. foreign policy, national security, and economic interests. While even a strengthened OPIC may not be able to compete "dollar-for-dollar" with China's DFI activity, supporters argue that the United States "can and should do more to support international economic development with partners who have embraced the private sector-driven development model."44

At the same time, OPIC has been the subject of long-standing criticism. Opponents of OPIC dispute the notion that the federal government should be involved in financing and insuring private sector investments. They argue that OPIC diverts capital away from efficient uses and crowds out private alternatives, take issue with OPIC assuming risks unwanted by the private sector, and question the development benefits of its programs.45 Critics have called for terminating OPIC's functions or privatizing them, rather than boosting them through a new DFI.46

From an economic perspective, the impact of government-backed financing on markets is often debatable. Some economists contend that officially backed financing by other countries is likely to have little effect on the overall level of U.S. investment, although certain foreign government policies may have harmed specific U.S. industries, and even if it has an impact, the net benefit may be small or negative due to opportunity costs. Other experts contend that U.S. government support is critical for U.S. investors to offset the effects of similar programs used by foreign governments.

While some development financing is complementary, one point of debate is the extent to which there is direct competition for investment projects between U.S investors and foreign investors backed by other governments. Moreover, a range of factors beyond investment financing may influence competitiveness. Proof that state-backed foreign investment financing places U.S. firms at a competitive disadvantage in overseas markets is difficult to identify, in part because of the lack of transparency for DFI activities. Nevertheless, the sheer magnitude of financing provided by emerging economies suggests that such financing may have discernable impacts on U.S. commercial activity in the long term.

Debate Over Reorganization

In the event that Congress determines that U.S. development finance functions should be reformed, a key question is whether consolidation is the best way to proceed, or if reforms should be made within individual agencies, keeping their current structures intact. A proposal to create a new DFI has been in the making for some time. In recent years, various civil society stakeholders, including some analysts at the Center for Global Development (CGD), have proposed consolidating the functions of OPIC and other agencies that they view as development finance into a new DFI.47

Congressional hearings have been held in recent years on development assistance reform that have considered changes to OPIC.48 The Administration's FY2019 budget proposal to create a new DFI was the outgrowth of interagency discussions, led by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the National Security Council (NSC) and involving OPIC, USAID, the State Department, and others, on challenges related to development; these discussions were prompted by the President's executive order on government reorganization.49 Against this backdrop, the BUILD Act was introduced in the House and Senate in February 2018 (see text box).

The Trump Administration issued a statement strongly supporting the BUILD Act, noting that it was broadly consistent with the Administration's goals and FY2019 budget proposal while also calling for some modifications to the bills. From the Administration's perspective, the bills should be modified to enhance the new DFI's alignment with U.S. national interests, as well as its institutional links with USAID and other development agencies. The Administration also held that the bills require other changes, including to the DFI's funding structure, to enhance the DFI's risk management and prevent it from displacing private sector resources.50

|

Overview of BUILD Act Proposal (H.R. 5105/S. 2463) As introduced, the BUILD Act would create a new International Development Finance Corporation (IDFC), a wholly owned U.S. government corporation, by consolidating all of OPIC's functions and USAID's DCA, enterprise funds, and development finance technical support functions. The IDFC would aim to support the role of private sector capital and skills in the economic development of developing countries, to promote U.S. development assistance objectives and advance foreign policy and economic interests. Management. The IDFC would be managed by a nine-member Board of Directors, composed of the Chief Executive Officer of the IDFC, four U.S. government officials (the Secretary of State, USAID Administrator, Secretary of the Treasury, and Secretary of Commerce—or their designees), and four private sector members. In contrast to OPIC, which has a 15-member Board, there would be no requirement for the IDFC's private sector members to include representation from small business, organized labor, or cooperatives. The Board Chairperson would be chosen from among the Board members (as in the case of OPIC), while the Vice Chairperson would be the USAID Administrator or his/her designee. The BUILD Act also would establish a Chief Risk Officer, as well as risk and audit committees. The IDFC would have its own Inspector General (IG); this would be in contrast to OPIC, which is under the supervision of the USAID IG. Authorities. The IDFC's authorities would expand beyond OPIC's existing authorities to make loans and guarantees and issue insurance or reinsurance; they would also include the authority to take minority equity positions in investments, subject to limitations. Drawing from USAID, the IDFC would be authorized to establish and operate enterprise funds as well. In addition, the IDFC would have the authority to conduct feasibility studies on proposed investment projects (with cost-sharing) and provide technical assistance. Like OPIC, the IDFC's authorities to support development finance would be backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. Conditions. The IDFC's activities would be subject to statutory requirements and limitations. Like OPIC, it would have to take into account the economic and financial soundness of projects, as well as prioritize its support in low-income or lower-middle-income economies. However, it would have a higher bar for providing support in upper-middle-income countries—restricting support in those countries unless the President makes a national interest determination and such support is likely to be highly developmental or beneficial to the poorest population in that country. Compared to OPIC, the IDFC would be subject to greater specifications on interest rates and ensuring the market-based nature of the new entity's support. While OPIC support is limited to investors that have a U.S. connection, the IDFC would only have to provide preferential consideration to projects sponsored by or involving the U.S. private sector. The IDFC would also have to give preferential consideration to countries in compliance with or making substantial progress in coming into compliance with their international trade obligations. As with OPIC, the IDFC's support would also have to take into account worker rights and environmental impact considerations. Support could not be provided in countries and to projects benefiting persons subject to U.S. sanctions. Reflecting OPIC's current practice of making sure that its support is "additional" to the private sector support for investment, the bill would explicitly require its support to supplement, not compete with, private sector support. Coordination. The CEO of the IDFC would have to consult with the USAID Administrator and the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) CEO to coordinate activities for development purposes. Capacity and Authorization. The IDFC's overall exposure would be capped at $60 billion for the five-year period after the act's enactment, and subject to increases, compared to OPIC's statutory exposure limit of $29 billion. The House version of the bill would authorize the IDFC for seven years, while the Senate version would authorize the IDFC until September 30, 2038. Funding. Like OPIC, the IDFC would be expected to operate on a "self-sustaining" basis. The IDFC's operations would appear to be supported through the funds generated from its investment financing and insurance activities. In addition, the IDFC would be authorized to issue Treasury notes and other debts, subject to a maximum cap of $1 billion. Risk Management. A risk committee and audit committee would be established to monitor the new entity's performance. The IDFC also would be required to develop a performance measure system and monitor projects, building on OPIC's current development impact measurement system. It would be subject to reporting and auditing requirements. Transition. The bill includes a number of transitional provisions, including requiring the President to submit a reorganization plan to the appropriate congressional committees within 60 days after the act's enactment and formally terminate OPIC. |

Supporters of reorganization argue that it could enhance government efficiency by eliminating overlap of functions and reducing costs. They also argue that consolidating the U.S. government's development finance functions would allow the U.S. government to better leverage its suite of development finance tools. Supporters also argue that the new DFI would help the United States compete more effectively with China and foreign counterparts by better matching the resources and authorities of those foreign DFIs. In addition to these rationales for reorganization, supporters also may see the creation of a broader DFI as a way to strengthen OPIC or shield it from potential future risk of elimination.

Critics of reorganization argue that it could incur costs through the creation of a new bureaucracy, at least in the short run. Other concerns raised include the risk that reorganization could dilute or undermine the effectiveness of the development finance functions at issue because OPIC and USAID, while both focused on development, have different constituencies and approaches in their work. For instance, although both have programs that deal with private enterprise, OPIC has had to be self-sustaining and accordingly less of a risk-taker than USAID. Still others may argue that a more effective way for the United States to focus on enhancing coordination of development finance functions among agencies or to support development goals is to focus on its activities through multilateral and regional DFIs.

Structuring a New DFI

If Congress pursues reorganization, it faces a number of issues regarding how to structure the proposed new DFI. The proposed DFI can be viewed as a distinct new entity but also would as a successor to OPIC. Thus, the issues raised by reorganization are discussed here as potential changes to OPIC.

Management Structure. Congress may consider how the structure and composition of the proposed DFI's management structure may reflect policy priorities. Under the BUIILD Act, the proposed DFI's Board of Directors would vary from OPIC's Board of Directors. The new DFI's nine-member Board of Directors would be composed of the Chief Executive Officer of the new DFI, four U.S. government officials (the Secretary of State, USAID Administrator, Secretary of the Treasury, and Secretary of Commerce—or their designees), and four private sector members. The Chairperson of the Board would be designated by the President from among the members of the Board, while the USAID Administrator (or his/her designee) would be the Vice Chairperson. In comparison, by statute, OPIC's 15-member Board of Directors is composed of 8 "private sector" Directors (with requirements for small business, labor, and cooperatives interests) and 7 "federal government" Directors (including the OPIC President, USAID Administrator, U.S. Trade Representative, and a Labor Department officer). The Chairman and Vice Chairmen of OPIC's Board are to be appointed by the President of the United States among the members of the Board. Thus, distinctions include that the new DFI's Board of Directors would be smaller; have more "federal government" than "private sector" representation; not have a specific requirement to have small business, organized labor, or cooperatives representation; and be required to have the USAID Administrator (or his/her designee) as the Vice Chairperson of the Board. These differences could raise questions about how the new DFI's management structure vis-à-vis OPIC's management structure could affect its emphasis on various stakeholder interests in its operations and institutional ties with other government agencies.

Length of Authorization. A question for Congress is whether to establish the new DFI as a permanent entity or one subject to reauthorization and, if the latter, how frequently. The House version of the BUILD Act would extend the new DFI's authority by seven years and the Senate version would extend it until FY2038. In considering this issue, Congress may consider looking to OPIC. In recent years, OPIC has been subject to yearly extensions of its authority through the appropriations process. Some argue that a multiyear or permanent authorization would enhance OPIC's ability to plan in the long term and provide assurances to investors about its programs. (OPIC commitments and obligations can be made for multiyear periods extending beyond any particular reauthorization.) Others argue that periodic reauthorizations allow for enhanced congressional oversight of OPIC's activities. Other DFIs tend not to be subject to a regular reauthorization process, as they were established as "permanent" entities, but remain subject to ongoing oversight and scrutiny by legislative bodies or executive agencies.

Exposure Limit. Congress may consider whether to modify OPIC's statutory exposure cap to change the capacity of the proposed new DFI. OPIC currently has a $29 billion exposure cap and in recent years has been nearing it. The BUILD Act would set the new development finance agency's exposure at $60 billion for five years, subject to increases based on certain considerations. A larger exposure cap would allow the new DFI to take on more projects and have the potential to have a greater development impact, yet it might increase risks to U.S. taxpayers if the projects that were supported experienced defaults or were subject to claims recoveries.

Authorities. Congress may examine whether to modify OPIC's existing authorities.

- Equity authority. The BUILD Act would give the new DFI the authority to take a minority equity stake in investment funds, subject to limitations. Supporters of such authority argue that the new DFI would be able to use the higher returns generally associated with equity investments to support more projects, as well as be more competitive vis-à-vis foreign counterparts, given that most other DFIs have equity authority.51 OPIC asserts that the ability to invest in investment funds as a limited partner could help diversify its total exposure in the long run through its "incremental return," as well as enable it to partner more effectively with other DFIs.52 However, there remains resistance to the notion of the U.S. government taking an ownership stake in a private enterprise. Critics argue that equity authority would require more resources in managing an investment, compared to one supported through debt instruments alone, and could lead to additional risk and financial exposure.

- Technical assistance. The BUILD Act would give the new DFI the authority to make grants for feasibility studies and other technical assistance. Presently, OPIC has limited authority to provide technical assistance for certain investment projects in Africa. Other U.S. government agencies focus more specifically on technical assistance for foreign policy programs, including the Department of State, USAID, and TDA—sometimes in collaboration with OPIC. For example, in the wake of the "Arab Spring," OPIC approved $500 million in lending to Egypt and Jordan to support small businesses in those countries, and USAID provided grant funding and technical assistance.53 Those in favor of technical assistance capacity for the DFI contend that this function would enhance the agency's effectiveness. Nevertheless, the new DFI's technical assistance function could overlap with other government agencies' roles. The technical assistance issue has prompted some to question the rationale for excluding TDA from the consolidation. Others point out that TDA aims to support U.S. exports through its programs to support economic development overseas.

Policy Parameters for Project Support. Congress may consider what requirements and limitations to impose on the new DFI's support for projects. Through such conditions, Congress can exercise its authority over the DFI and guide its activities more directly, even if it is not involved in approving individual projects. At the same time, it may wish to consider the impact of layering conditions on the new DFI's support on its flexibility and agility, including vis-à-vis other DFIs, which may attach different terms and policy conditions to their support. Many of the BUILD Act's provisions mirror OPIC's current parameters, such as requirements to take into account worker rights and environmental impact factors. Some provisions would vary, including the following:

- Scope of geographic operations. OPIC, by its statute, must give preferential consideration to investment projects in less-developed countries and restrict its support in higher-income countries; it has interpreted this requirement to allow it to support projects in higher-income countries that are highly developmental or focus on underserved areas or populations.54 The BUILD Act also would prioritize support in low-income or lower-middle-income economies, but set a higher bar for providing support in upper-middle-income countries, including subjecting it to a national interest determination by the President. This could enhance the DFI's development impact in the poorest regions, but also inhibit its impact to the extent that investors prefer supporting projects that are in higher-income countries but that are nevertheless development oriented.

- "U.S. nexus" requirement. While OPIC support is only available to investors that have a U.S. connection, the new DFI would only have to give preferential consideration to projects sponsored by or involving the U.S. private sector. Such a modification could expand the DFI's development impact, but at the same time, decrease benefits to U.S. employment interests.

Risk Management. The adequacy of the proposed new U.S. DFI's risk management practices could be of interest for Congress, as the BUILD Act would expand the new DFI's exposure cap and its authorities. Some may argue that any increased risks relative to OPIC would be limited, and that the proposed DFI would have the organizational structure to manage risks properly, such as through the Chief Risk Officer and audit and risk committees prescribed by the BUILD Act. Others say that technical assistance conducted by the new DFI for projects could help to strengthen projects, and lead to projects that are more financially sound. Still others may argue that for the new DFI to be effective, it must be willing to take on risks, because it is in those riskier markets where it will be able to make the most the difference in terms of development.

Oversight. The BUILD Act would establish an Inspector General (IG) specific to the new DFI. Presently, the USAID IG has legal authority to conduct reviews, investigations, and inspections of OPIC's operations and activities. Given the differing roles of OPIC and USAID and the fact that the new DFI, as a merger, would be a distinctly new entity, one view could be that there is a need to establish an IG specific to the new DFI.55 Another view could be that the current OPIC-USAID arrangement suffices and no additional resources should be directed to creating a new IG.

Measuring Success. If Congress structures a new DFI, a consideration is how to measure the proposed agency's performance. Under the BUILD Act, the new DFI would be required to develop a performance measurement system and monitor projects, using OPIC's current development impact measurement system as a starting point. Measuring development impact can be complicated for a number of reasons, including definitional issues, difficulties isolating the impact of development finance from other variables that affect development outcome, challenges in monitoring projects for development impact after DFI support for a project ends, and resource constraints. Comparing development impacts across DFIs is also difficult as development indicators may not be harmonized. To the extent that the proposed DFI raises questions within the development community about whether it would be truly "developmental" at its core, rigorous adherence to development objectives through a measurement system will likely be critical to gauging its effectiveness. Moreover, Congress may wish to take a broader view of U.S. development impact, given the active U.S. contributions to regional and multilateral DFIs.

Funding

If Congress decides to establish a new DFI, it will likely have to consider how to fund it. Under the BUILD Act, the new DFI would be directed to be "self-sustaining" like OPIC and similarly to fund its operation through the fees and other revenues it collects. Congress may consider to what extent the DFI's potentially expanded capacity and functions, as well as other features, may shape its ability to operate on a self-sustaining basis or not. For example, one consideration is how the new DFI would fund its grant-making functions. The Administration proposal allocates $56 million in Economic Support and Development Fund (ESDF) money for development finance related programming and authorizes "additional transfers" of funds from USAID.56 OPIC leadership points to the ESDF as a possible way to fund grants by the new DFI.57 Some contemplate that the DFI's grant-making activities would be limited.

Impact on USAID and U.S. Development Objectives

If enacted into law, both the proposed legislation and the Administration's FY2019 budget proposal on the new DFI would have an impact on USAID, although, lacking detail, the full extent of these initiatives' impact is not yet clear. The Administration proposal and the legislation both call for USAID to transfer the Development Credit Authority to the new DFI. The legislation alone calls for further removal from USAID of the enterprise funds and the Office of Private Capital and Microenterprise. This section discusses possible consequences for USAID.

Removal of the DCA. The DCA is one of many assistance tools available to USAID. It has generally been used by the agency to produce specific development outcomes. Almost all DCA projects have originated through the country- or region-based missions which identified a problem and used DCA guarantees to help address the problem, often in conjunction with an array of other project activities, including technical assistance and training that, in their totality, made the loans more effective. Supporters of the proposed reorganization assert that consolidating DCA with other development finance functions would increase the efficiency of these functions.58 However, former USAID Administrator Andrew Natsios and former Associate Administrator Eric Postel argue that removing the DCA from USAID would end the integration of this tool in that broader project design, making its use as a development tool less effective.59 As discussed below, proponents suggest that, with effective interagency coordination, USAID could still access the full benefits of DCA guarantee instruments.

Removal of the Enterprise Funds. Some observers say that the existing authorities for the Europe/Eurasia enterprise funds, which the legislation would transfer to the proposed DFI, are specific to the time and place in which they operated. Those older funds are also substantially different from the two current funds, which, like existing models of investment funds managed directly by OPIC, are more restricted in their range of activities to equity investments and lending. The new USAID enterprise funds, however, remain primarily funded by U.S. government grant funds, while OPIC's are supported with private sector money. The USAID model is also private-sector-managed, likely requiring close USAID oversight and an in-country presence to ensure the funds fulfill a development, rather than a purely for-profit, mission. As such, their removal to an agency without either feature may make this model less effective as a development instrument. Relatedly, it has been argued that if the new DFI would have the authority to conduct equity investment, there is no need for an enterprise fund.60

Removal of the Office of Private Capital and Microenterprise (PCM). PCM conducts both a research/project pilot function in identifying opportunities to draw in private capital and a technical expertise resource function benefitting USAID missions. The latter function would likely be lost if the office is transferred to the new DFI or, as some have noted, would simply have to be reintroduced in some other form if USAID is to play any continuing role in this sphere. It is also not clear whether legislators intend to transfer microfinance functions out of the agency as well—PCM does little on this issue, as microenterprise activities have been incorporated into other sectors and mechanisms.61

Transfer of these financing functions, whether for efficiency or nonduplication purposes, could have unintended impacts on USAID's overall development efforts. For example, USAID has employed loan guaranties in support of its broader health, agriculture, environment, and other sector programs. To a more limited extent, it has supported equity investment programs separate from the enterprise funds in Pakistan and elsewhere. Efforts to leverage private capital in support of development are conducted throughout the agency and in every sector with or without PCM assistance. To the extent that the DFI proposals would prevent duplication of methodologies that employ private funding, many USAID development efforts could be made less effective.

In addition, the proposal calls for the transfer of $56 million from traditional USAID accounts to the new DFI to be used for development finance-related programming, including advisory services, technical assistance, capacity building, and credit subsidies. This funding, and "additional transfers" for which the proposal seeks authority, would otherwise presumably remain with USAID to achieve similar objectives.62

As currently constituted, the proposals imply that cost savings and operational efficiencies would ensue from concentrating development finance capabilities in one institution. It is unclear how the transfer of offices, personnel, and loan authorities from one agency to the next would save funds. It is also unclear how the new DFI would be able to efficiently conduct its activities without seeking to duplicate the features that give USAID its advantage as a development programming and implementation agency, namely its convening power, development know-how, and mission presence. One possible answer that the legislation implies is close coordination (see below).

Interagency Coordination

If Congress determines that consolidation is the best way to proceed, a critical issue is how to ensure sufficient, long-term interagency coordination between the new DFI and other federal agencies. The legislation suggests that coordination between the DFI and two key development agencies—USAID and the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC)—would be a necessary feature of the proposal by requiring appointment of a Chief Development Officer who would be responsible for coordinating policy and its implementation with the development missions of its sister agencies. The Administration budget proposal similarly anticipates the DFI's "strong linkages" to USAID, suggesting that it would work "closely with the missions and other parts of USAID to enhance the enabling environment for private sector investment."63

Supporters of the DFI proposal appear to recognize the role of USAID missions in identifying and funding financing needs and USAID's Development Credit Authority in implementing those financing programs. Many supporters of the DFI proposal believe that this system should continue even with DCA consolidation into the DFI. They argue that the proposal might have positive benefits for USAID if its relationship with the DFI provides USAID missions with access, not only to its former DCA guarantee instrument, but to the whole range of finance tools, including equity and risk insurance, that the DFI would manage. Similarly, the DFI would be able to significantly expand its overseas presence through access to USAID's missions. The trick, as some observers have noted, is to make the process for USAID missions to draw on DFI tools and the DFI to draw on USAID—the coordination between the two distinct agencies—"seamless."

The history of foreign aid interagency cooperation and coordination suggests the difficulties of achieving smoothly functioning coordination. In the past decade alone, commentators have pointed to the fragmentation of development assistance among multiple players, the problems of coordination between the State Department Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator and its program implementers, tensions between State and USAID in Pakistan and Arab Spring countries, and the lack of complementarity between MCC and USAID (despite the latter's presence on the MCC Board of Directors) as examples of interagency difficulties.64

Different agencies develop different corporate cultures and focus and observers note strong distinctions between OPIC and USAID. Currently, OPIC provides relatively larger-scale financing, has been more oriented toward infrastructure historically but has offered support for financial and other noninfrastructure investments lately, and can only support projects that have meaningful involvement by the U.S. private sector.65 USAID works at a significantly more small-scale, locally oriented level, and has been described as more risk tolerant in its development efforts as it works in a much less structured environment. Each agency approaches development in vastly different ways—the fact that they do not do the same deals now suggests these differences.66 Some have suggested that OPIC is unlikely to understand the myriad USAID regulations and legislative restrictions under which it operates and question whether it or the DFI would be able to work successfully in the USAID mission environment (and vice versa).

Some observers believe that, for the new DFI to effectively play a development assistance role in support of USAID, coordination should be hard-wired into the authorizing legislation, rather than depending on impermanent interpersonal relationships or shared board membership to effect a temporary cooperation. One suggestion is a dual-hatted—both DFI and USAID—Chief Development Officer, to help ensure that the DFI operates in a way that would meet USAID needs in the field. Another possible path forward is to require that DCA guarantees continue to draw their funding from USAID mission budgets, thereby ensuring that the DFI views USAID as a key customer. In addition, the metrics required by the legislation to measure development success could include support for USAID programs as an indicator.

In addition to examining interagency coordination from a development perspective, Congress also may consider coordination issues from the export promotion perspective. OPIC has a strong private sector orientation, and investment is linked to U.S. exports and other economic impacts. OPIC and Ex-Im Bank have a history of collaboration, including on financing projects under Administration initiatives such as Power Africa and conducting outreach to small businesses on U.S. government financing resources.67 OPIC also is a member of the interagency Trade Promotion Coordinating Committee (TPCC)68 and involved in Administration export promotion efforts.69 To the extent that the proposed DFI's role with respect to the private sector is different from that of OPIC, Congress may consider to what extent the proposal would affect the current synergies between OPIC and Ex-Im Bank, as well as broader implications for interagency coordination of the U.S. government's export promotion activities.

Competitiveness and Future Rules-Setting

Congress may examine how the new DFI would support U.S. businesses in competing with foreign businesses for overseas investment opportunities. For example, how would the capacity, authorities, policy parameters, and other features formulated by Congress enable or constrain the DFI from supporting U.S. private investment overseas for development? What policy trade-offs would these features entail?

The new DFI's potential role in supporting U.S. strategic economic interests also may be of congressional interest. The Trump Administration has cast development finance reorganization as a way to advance U.S. influence and serve as an alternative to state-directed investment models, notably by China. The National Security Strategy stated, "American-led investments represent the most sustainable and responsible approach to development and offer a stark contrast to the corrupt, opaque, exploitive, and low-quality deals offered by authoritarian states."70 Given that a U.S. DFI would not be able to match the resources of China's DFIs, Congress may examine how the new DFI could deploy its resources strategically to advance U.S. policy objectives. At the same time, Congress may examine how a more strategic orientation for the DFI would align with the typically demand-driven nature of U.S. government support for private sector activity, as has been the case for OPIC.

In addition, Congress may consider whether to advocate for creating international "rules for the road" for development finance. Such rules could help ensure that the proposed DFI operates on a "level playing field" relative to its counterparts, given the variation in terms, conditions, and practices of DFIs internationally. U.S. involvement in developing such rules could help advance U.S. strategic interests. However, such rules would only be effective to the extent that major suppliers of development finance are willing to abide by them. For example, China is not a party to international rules on export credit financing, though it has been involved in recent negotiations to develop new rules on such financing.

Outlook

While there is bipartisan, bicameral support in Congress for moving forward with development finance reorganization, the current proposal presents Congress with a number of issues in terms of structuring the proposed new DFI and the implications of reorganization. Development finance is a cross-cutting issue implicating U.S. interests in terms of foreign policy, national security, economic interests, and international investment. Combining public support with private sector capital, development finance also intersects with a range of stakeholder interests and any reorganization may raise questions about how to balance various policy goals. Thus, consideration of the BUILD Act or any other legislation introduced to reorganize federal development finance functions may be an active area of debate for Congress.

Appendix. Comparison: OPIC and Foreign DFIs

Source: CRS, based on information available about DFIs in their annual reports and other sources.

Notes: Data on development finance activity size may not be directly comparable due to differences among the DFIs, such as in operations, metrics, reporting, and fiscal years. In addition, the size amounts reported may reflect more than development finance, such as for entities that conduct both export and investment financing. Conversions to U.S. dollars based on Federal Reserve exchange rates on April 13, 2018. Finance may include loans and guarantees, as well specialized types of financing, such as project financing.