Introduction

Successive Administrations have identified Iran as a key national security challenge, citing Iran's nuclear and missile programs as well as its long-standing attempts to counter many U.S. objectives in the region. Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats, in his May 11, 2017, annual worldwide threat assessment testimony before Congress, described Iran as "an enduring threat to U.S. national interests because of Iranian support to anti-U.S. terrorist groups and militants.... " Successive National Defense Authorization Acts (NDAAs) require an annual report on Iran's military power, which has in recent years contained assessments of Iran similar to those presented by the intelligence community. The report for FY2016, released January 2017, says that Iran continues to take steps to "emerge as a dominant regional power."1

Iran's Policy Motivators

Iran's foreign and defense policies are products of overlapping, and sometimes contradictory, motivations. In describing the tension between some of these motivations, one expert has said that Iran faces constant decisions about whether it is a "nation or a cause."2 Iranian leaders appear to constantly weigh the relative imperatives of their revolutionary and religious ideology against the demands of Iran's national interests.

Threat Perception

Iran's leaders are apparently motivated, at least to some extent, by the perception of threat to their regime and their national interests Ayatollah posed by the United States and its allies.

- Iran's paramount decision-maker, Supreme Leader Grand Ayatollah Ali Khamene'i, has repeatedly stated that the United States has never accepted the Islamic revolution and seeks to overturn it through support for domestic opposition to the regime, imposition of economic sanctions, and support for Iran's regional adversaries.3 He frequently warns against Western "cultural influence"—social behavior that he asserts does not comport with Iran's societal and Islamic values. The FY2016 DOD report on the military power of Iran, released in January 2017, says that "Supreme Leader Ali Khamene'i maintains a deep distrust of U.S. intentions toward Iran.... "4

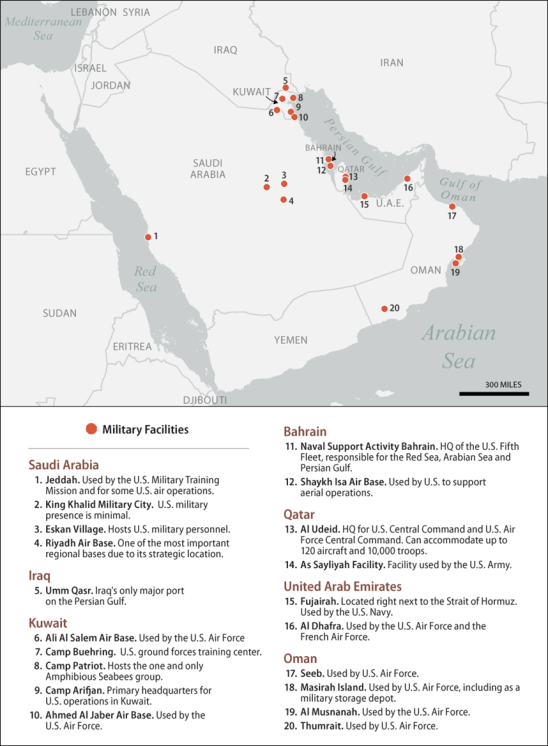

- Iran's leaders assert that the U.S. maintenance of a large military presence in the Persian Gulf region and in other countries around Iran reflects intent to intimidate Iran or attack it if Iran pursues policies the United States finds inimical.5

- Iran's leaders assert that the United States' support for Sunni Arab regimes that oppose Iran has led to the empowerment of radical Sunni Islamist groups and spawned Sunni-dominated terrorist groups such as the Islamic State.6

Ideology

The ideology of Iran's 1979 Islamic revolution continues to infuse Iran's foreign policy. The revolution overthrew a secular, authoritarian leader, the Shah, who the leaders of the revolution asserted had suppressed Islam and its clergy. A clerical regime was established in which ultimate power is invested in a "Supreme Leader" who melds political and religious authority.

- In the early years after the revolution, Iran attempted to "export" its revolution to nearby Muslim states. In the late 1990s, Iran abandoned that goal because promoting it succeeded only in producing resistance to Iran in the region.7

- Iran's leaders assert that the political and economic structures of the Middle East are heavily weighted against "oppressed" peoples and in favor of the United States and its allies, particularly Israel. Iranian leaders generally describe as "oppressed" peoples the Palestinians, who do not have a state of their own, and Shiite Muslims, who are underrepresented and economically disadvantaged minorities in many countries of the region.

- Iran claims that the region's politics and economics have been distorted by Western intervention and economic domination that must be brought to an end. Iranian officials claim that the creation of Israel is a manifestation of Western intervention that deprived the Palestinians of legitimate rights.

- Iran claims its ideology is nonsectarian, rebutting critics who say that Iran only supports Shiite movements. Iran cites its support for Sunni groups such as Hamas as evidence that it is not pursuing a sectarian agenda. Iran cites its support for secular and Sunni Palestinian groups as evidence that it works with non-Islamist groups to promote the rights of the Palestinians.

National Interests

Iran's national interests usually dovetail with, but sometimes conflict with, Iran's ideology.

- Iran's leaders, stressing Iran's well-developed civilization and historic independence, claim a right to be recognized as a major power in the region. They contrast Iran's history with that of the six Persian Gulf monarchy states (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, and Oman of the Gulf Cooperation Council, GCC), most of which gained independence only in the 1960s and 1970s. To this extent, many of Iran's foreign policy actions are similar to those undertaken by the Shah of Iran and prior Iranian dynasties.

- Iran has sometimes tempered its commitment to aid other Shiites to promote its geopolitical interests. For example, it has supported mostly Christian-inhabited Armenia, rather than Shiite-inhabited Azerbaijan, in part to thwart cross-border Azeri nationalism among Iran's large Azeri minority. It has refrained from backing Islamist movements in the Central Asian countries, which are mainly Sunni and potentially hostile toward Iran. Russia takes a similar view of Central Asian and other Sunni-dominated Islamist groups as does Iran.

- Even though Iranian leaders accuse U.S. allies of contributing to U.S. efforts to structure the Middle East to the advantage of the United States and Israel, Iranian officials have sought to engage with and benefit from transactions with historic U.S. allies, such as Turkey, to try to thwart international sanctions.

Factional Interests and Competition

Iran's foreign policy often appears to reflect differing approaches and outlooks among key players and interest groups.

- According to Iran's constitution and in practice, Iran's Supreme Leader has final say over all major foreign policy decisions. Grand Ayatollah Ali Khamene'i, Supreme Leader since 1989, consistently expresses mistrust of U.S. intentions toward Iran. His consistent refrain, and the title of his book widely available in Iran, is "I am a revolutionary, not a diplomat."8 Leaders of Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the military and internal security force created after the Islamic revolution, consistently express support for Khamene'i and an assertive foreign policy.

- More moderate Iranian leaders, including President Hassan Rouhani, argue that Iran should not have any "permanent enemies." They maintain that a pragmatic foreign policy has resulted in easing of international sanctions under the JCPOA, increased worldwide attention to Iran's views, and positions Iran as a potential trade and transportation hub in the region. Rouhani has said that the JCPOA is "a beginning for creating an atmosphere of friendship and co-operation with various countries."9 Rouhani tends to draw support from Iran's youth and intellectuals, who say they want greater integration with the international community and who helped Rouhani achieve a convincing first-round reelection victory on May 19, 2017, with 57% of the vote against a candidate with unified hardliner backing.

Instruments of Iran's National Security Strategy

Iran employs a number of different methods and mechanisms to implement its foreign policy, including supporting armed factions.

Financial and Military Support to Allied Regimes and Groups

- Iran provides arms, training, and military advisers in support of allied governments and movements, such as the regime of President Bashar Al Asad of Syria, Lebanese Hezbollah, Hamas, Houthi rebels in Yemen, and Shiite militias in Iraq. Iran supports some Sunni Muslim groups: most Palestinians are Sunni Muslims and several Palestinian FTOs receive Iranian support because they are antagonists of Israel.

- The State Department report on international terrorism for 2016 stated that Iran remained the foremost state sponsor of terrorism in 2016, and continued to play a "destabilizing role" in military conflicts in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen. Iran also has been implicated in supporting violent Shiite opposition group attacks in Bahrain. Iran was joined in these efforts by Hizballah.10

- DNI Dan Coats, in his annual worldwide threat assessment testimony to Congress on May 11, 2017, said Iran "continues to be the foremost state sponsor of terrorism"11—a formulation used by U.S. officials for more than two decades. Many of the groups Iran supports are named as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs) by the United States, and because of that support, Iran was placed on the U.S. list of state sponsors of terrorism ("terrorism list") in January 1984.12

- Some armed factions that Iran supports have not been named as FTOs and have no record of committing acts of international terrorism. Such groups include the Houthi ("Ansar Allah") movement in Yemen (composed of Zaidi Shiite Muslims) and some underground Shiite opposition factions in Bahrain.

- Iran generally opposes Sunni terrorist groups that work against Iran's core interests, such as Al Qaeda and the Islamic State organizations.13 Iran is actively working against the Islamic State organization in Syria and Iraq and, over the past few years, Iran has expelled some Al Qaeda activists who Iran allowed to take refuge there after the September 11, 2001, attacks. However, Iran allowed Al Qaeda senior operatives to transit or reside in Iran possibly as leverage against the United States or Saudi Arabia.

- Iran's operations in support of its allies—which generally include arms shipments, provision of advisers, training, and funding—are carried out by the Qods (Jerusalem) Force of the IRGC (IRGC-QF). That force is headed by IRGC Major General Qasem Soleimani, who reports directly to Khamene'i.14 IRGC leaders have on numerous occasions publicly acknowledged these activities.15 Much of the weaponry Iran supplies to its allies includes specialized anti-tank systems ("explosively-forced projectiles" EFPs), artillery rockets, mortars, short-range missiles, and anti-ship cruise missiles.16

- It should be noted that U.N. Security Council Resolution 2231, which superseded prior resolutions as of JCPOA Implementation Day (January 16, 2016), continues U.N. restrictions on Iran's exportation for a maximum of five years (from Adoption Day, October 17, 2015). Separate U.N. Security Council resolutions ban arms shipments to such conflict areas as Yemen (Resolution 2216) and Lebanon (Resolution 1701). There is no U.N. ban on arms exports to Syria.

|

Date |

Incident/Event |

Claimed/Likely Perpetrator |

|

November 4, 1979 |

U.S. Embassy in Tehran seized and 66 U.S. diplomats held for 444 days (until January 21, 1981). |

Hardline Iranian regime elements |

|

April 18, 1983 |

Truck bombing of U.S. Embassy in Beirut, Lebanon. 63 dead, including 17 U.S. citizens. |

Factions that eventually formed Lebanese Hezbollah claimed responsibility. |

|

October 23, 1983 |

Truck bombing of U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut. 241 Marines killed. |

Same as above |

|

December 12, 1983 |

Bombings of U.S. and French embassies in Kuwait City. 5 fatalities. |

Da'wa Party of Iraq—Iran-supported Iraqi Shiite militant group. 17 Da'wa activists charged and imprisoned in Kuwait |

|

March 16, 1984 |

U.S. Embassy Beirut Political Officer William Buckley taken hostage in Beirut—first in a series of kidnappings there. Last hostage released December 1991. |

Factions that eventually formed Hezbollah. |

|

September 20, 1984 |

Truck bombing of U.S. embassy annex in Beirut. 23 killed. |

Factions that eventually formed Hezbollah |

|

May 25, 1985 |

Bombing of Amir of Kuwait's motorcade |

Da'wa Party of Iraq |

|

June 14, 1985 |

Hijacking of TWA Flight 847. One fatality, Navy diver Robert Stetham |

Lebanese Hezbollah |

|

February 17, 1988 |

Col. William Higgins, serving with the a U.N. peacekeeping operation, was kidnapped in southern Lebanon; video of his corpse was released 18 months later. |

Lebanese Hezbollah |

|

April 5, 1988 |

Hijacking of Kuwait Air passenger plane. Two killed. |

Lebanese Hezbollah, seeking release of 17 Da'wa prisoners in Kuwait. |

|

March 17, 1992 |

Bombing of Israeli Embassy in Buenos Aires. 29 killed. |

Lebanese Hezbollah, assisted by Iranian intelligence/diplomats. |

|

July 18, 1994 |

Bombing of Argentine-Jewish Mutual Association (AMIA) building in Buenos Aires. |

Same as above |

|

June 25, 1996 |

Bombing of Khobar Towers housing complex near Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. 19 U.S. Air Force personnel killed. |

Saudi Hezbollah, a Saudi Shiite organization active in eastern Saudi Arabia and supported by Iran. Some assessments point to involvement of Al Qaeda. |

|

October 11, 2011 |

U.S. Justice Dept. unveiled discovery of alleged plot involving at least one IRGC-QF officer, to assassinate Saudi Ambassador in Washington, DC. |

IRGC-QF reportedly working with U.S.-based confederate allegedly in conjunction with a Mexican drug cartel. |

|

February 13, 2012 |

Wife of Israeli diplomat wounded in Delhi, India |

Lebanese Hezbollah |

|

July 19, 2012 |

Bombing in Bulgaria killed five Israeli tourists. |

Lebanese Hezbollah |

Sources: Recent State Department Country Reports on Terrorism; various press.

Other Political Action

Iran's national security is not limited to militarily supporting allies and armed factions.

- A wide range of observers report that Iran has provided funding to political candidates in neighboring Iraq and Afghanistan to cultivate allies there.17

- Iran has reportedly provided direct payments to leaders of neighboring states in an effort to gain and maintain their support. In 2010, then-President of Afghanistan Hamid Karzai publicly acknowledged that his office had received cash payments from Iran.18

- Iran has established some training and education programs that bring young Muslims to study in Iran. One such program runs in Latin America, despite the small percentage of Muslims there.19

Diplomacy

Iran also uses traditional diplomatic tools.

- Iran has an active Foreign Ministry and maintains embassies or representation in all countries with which it has diplomatic relations. Khamene'i has rarely traveled outside Iran as Supreme Leader—and not at all in recent years—but Iran's presidents travel outside Iran frequently, including to Europe or U.N. meetings in New York. Khamene'i and Iran's presidents frequently host foreign leaders in Tehran.

- Iran actively participates in or seeks to join many different international organizations, including those that are dominated by members critical of Iran's policies. Iran has sought to join the World Trade Organization (WTO) since the mid-1990s. Its prospects for being admitted increased by virtue of the JCPOA, but the process of accession is complicated and lengthy. Iran also seeks full membership regional organizations including the South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Officials from some SCO countries have said that the JCPOA removed obstacles to Iran's obtaining full membership, but opposition from some members have blocked Iran's accession to date.20

- From August 2012 until August 2015, Iran held the presidency of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), which has about 120 member states and 17 observer countries and generally shares Iran's criticisms of big power influence over global affairs. In August 2012, Iran hosted the NAM annual summit.

- Iran is a party to all major nonproliferation conventions, including the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC). Iran insists that it has adhered to all its commitments under these conventions, but the international community asserted that it did not meet all its NPT obligations and that Iran needed to prove that its nuclear program is for purely peaceful purposes. Negotiations between Iran and international powers on this issue began in 2003 and culminated with the July 2015 JCPOA.

- Iran has participated in multilateral negotiations to try to resolve the civil conflict in Syria, most recently in partnership primarily with Russia and Turkey. But, U.S. officials say that Iran's main goal is to ensure Asad's continuation in power.

Iran's Nuclear and Defense Programs

Iran has pursued a wide range of defense programs, as well as a nuclear program that the international community perceived could be intended to eventually produce a nuclear weapon. These programs are discussed in the following sections.

Nuclear Program21

Iran's nuclear program has been a paramount U.S. concern for successive administrations, in part because Iran's acquisition of an operational nuclear weapon could cause Iran to perceive that it is immune from outside military pressure. U.S. officials have asserted that Iran's acquisition of a nuclear weapon would produce a nuclear arms race in one of the world's most volatile regions and that Iran might transfer nuclear technology to extremist groups. Israeli leaders characterize an Iranian nuclear weapon as a threat to Israel's existence. Some Iranian leaders argue that a nuclear weapon could end Iran's historic vulnerability to great power invasion, domination, or regime change attempts.

Iran's nuclear program became a significant U.S. national security issue in 2002, when Iran confirmed that it was building a uranium enrichment facility at Natanz and a heavy water production plant at Arak.22 The perceived threat escalated significantly in 2010, when Iran began enriching uranium to 20% purity, which is relatively easy to enrich further to weapons-grade uranium (90%+). Another requirement for a nuclear weapon is a triggering mechanism that, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency, Iran researched as late as 2009. The United States and its partners also have insisted that Iran must not possess a nuclear-capable missile.

Iran's Nuclear Intentions and Activities

The U.S. intelligence community has stated in recent years, including in the Worldwide Threat Assessment delivered May 11, 2017, that the community does not know whether Iran will eventually decide to build nuclear weapons. But, Iran's acknowledged adherence to the JCPOA indicates that Iran has deferred a decision on the long-term future of its nuclear program. Iranian leaders cite Supreme Leader Khamene'i's 2003 formal pronouncement (fatwa) that nuclear weapons are un-Islamic as evidence that a nuclear weapon is inconsistent with Iran's ideology. On February 22, 2012, Khamene'i stated that the production of and use of a nuclear weapon is prohibited as a "great sin," and that stockpiling such weapons is "futile, expensive, and harmful."23 Some have argued that an attempt by Iran to develop a nuclear weapon would stimulate a regional arms race or trigger Israeli or U.S. military action.

Iranian leaders assert that Iran's nuclear program was always intended for civilian uses, including medicine and electricity generation. Iran argued that uranium enrichment is its "right" as a party to the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and that it wants to make its own nuclear fuel to avoid potential supply disruptions by international suppliers. U.S. officials have said that Iran's use of nuclear energy is acceptable.

IAEA findings that Iran researched a nuclear explosive device—detailed in a December 2, 2015, International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) report—cast doubt on Iran's assertions of purely peaceful intent for its nuclear program. But there have been no assertions that Iran has diverted nuclear material for a nuclear weapons program.24

Nuclear Weapons Time Frame Estimates

Prior to the JCPOA, then-Vice President Biden told a Washington, DC, research institute on April 30, 2015, that Iran could likely have enough fissile material for a nuclear weapon within two to three months of a decision to manufacture that material. U.S. officials said that the JCPOA increased the "breakout time"—an all-out effort by Iran to develop a nuclear weapon using declared facilities or undeclared covert facilities—to at least 12 months.

Status of Uranium Enrichment and Ability to Produce Plutonium25

A key to extending the "breakout time" is to limit Iran's capacity to enrich uranium. When the JCPOA was agreed, Iran had about 19,000 total installed centrifuges, of which about 10,000 were operating. Prior to the interim nuclear agreement (Joint Plan of Action, JPA), Iran had a stockpile of 400 lbs of 20% enriched uranium (short of the 550 lbs. that would be needed to produce one nuclear weapon). Weapons grade uranium is uranium that is enriched to 90%.

Under the JCPOA, Iran removed from installation all but 6,100 centrifuges, and reduced its stockpile of 3.67% uranium enriched to 300 kilograms (660 lbs.). These restrictions start to come off after 10-15 years from Implementation Day (January 16, 2016). Another means of acquiring fissile material for a nuclear weapon is to reprocess plutonium, a material that could be produced by Iran's heavy water plant at Arak. In accordance with the JCPOA, Iran rendered inactive the core of the reactor and has agreed to limit its stockpile of heavy water to agreed levels. At times when Iran has temporarily exceeded the allowed amounts of heavy water, it has exported excess amounts (including to the United States) to reduce its holdings below threshold levels.

Bushehr Reactor/Russia to Build Additional Reactors

The JCPOA does not prohibit operation or new construction of civilian nuclear plants such as the one Russia built at Bushehr. Under their 1995 bilateral agreement commissioning the construction, Russia supplies nuclear fuel for that plant and takes back the spent nuclear material for reprocessing. Russia delayed opening the plant apparently to pressure Iran on the nuclear issue, but it became provisionally operational in September 2012.

In November 2014, Russia and Iran reached agreement for Russia to build two more reactors—and possibly as many as six more beyond that—at Bushehr and other sites. Russia is to supply and reprocess all fuel for these reactors. In January 2015, Iran announced it would proceed with the construction of two such plants at Bushehr. Because all nuclear fuel and reprocessing is supplied externally, these plants are not considered a significant proliferation concern and were not addressed in the JCPOA.

International Diplomatic Efforts to Address Iran's Nuclear Program

The JCPOA was the product of a long international effort to persuade Iran to negotiate limits on its nuclear program. That effort began when it was revealed by the United States that Iran was building facilities to enrich uranium. In 2003, France, Britain, and Germany (the "EU-3") opened a diplomatic track to negotiate curbs on Iran's program. On October 21, 2003, Iran pledged, in return for peaceful nuclear technology, to suspend uranium enrichment activities and sign and ratify the "Additional Protocol" to the NPT (allowing for enhanced inspections). Iran signed the Additional Protocol on December 18, 2003, although the Majles did not ratify it.

Iran ended the suspension after several months, but the EU-3 and Iran subsequently reached a more specific November 14, 2004, "Paris Agreement," under which Iran suspended uranium enrichment in exchange for renewed trade talks and other aid. The Bush Administration supported the agreement with a March 11, 2005, announcement that it would drop its objection to Iran's applying to join the World Trade Organization (WTO). The Paris Agreement broke down in 2005 when Iran rejected an EU-3 proposal for a permanent nuclear agreement as offering insufficient benefits. In August 2005, Iran began uranium "conversion" (one step before enrichment) at its Esfahan facility. On September 24, 2005, the IAEA Board declared Iran in noncompliance with the NPT and, on February 4, 2006, the IAEA board voted 27-326 to refer the case to the Security Council. The Council set an April 29, 2006, deadline to cease enrichment.

"P5+1" Formed. In May 20016, the Bush Administration join the talks, triggering an expanded negotiating group called the "Permanent Five Plus 1" (P5+1: United States, Russia, China, France, Britain, and Germany). A P5+1 offer to Iran on June 6, 2006, guaranteed Iran nuclear fuel (Annex I to Resolution 1747) and threatened sanctions if Iran did not agree (sanctions were imposed in subsequent years).27

U.N. Security Council Resolutions Adopted

The U.N. Security Council subsequently imposed sanctions on Iran in an effort to shift Iran's calculations toward compromise. A table outlining the provisions of the U.N. Security Council Resolutions on Iran's nuclear program can be found in CRS Report RS20871, Iran Sanctions, by [author name scrubbed]. (The resolutions below, as well as Resolution 1929, were formally superseded on January 16, 2016, by Resolution 2231.)

- Resolution 1696 (July 31, 2006). The Security Council voted 14-1 (Qatar voting no) for U.N. Security Council Resolution 1696, giving Iran until August 31, 2006, to suspend enrichment suspension, suspend construction of the Arak heavy-water reactor, and ratify the Additional Protocol to Iran's IAEA Safeguards Agreement. It was passed under Article 40 of the U.N. Charter, which makes compliance mandatory, but not under Article 41, which refers to economic sanctions, or Article 42, which authorizes military action.

- Resolution 1737 (December 23, 2006). After Iran refused a proposal to temporarily suspend enrichment, the Security Council adopted U.N. Security Council Resolution 1737 unanimously, under Chapter 7, Article 41 of the U.N. Charter. It demanded enrichment suspension by February 21, 2007, prohibited sale to Iran of nuclear technology, and required U.N. member states to freeze the financial assets of named Iranian nuclear and missile firms and related persons.

- Resolution 1747 (March 24, 2007) Resolution 1747, adopted unanimously, demanded Iran suspend enrichment by May 24, 2007. It added entities to those sanctioned by Resolution 1737 and banned arms transfers by Iran (a provision directed at stopping Iran's arms supplies to its regional allies and proxies). It called for, but did not require, countries to cease selling arms or dual use items to Iran and for countries and international financial institutions to avoid giving Iran any new loans or grants (except loans for humanitarian purposes).

- Resolution 1803 (March 3, 2008) Adopted by a vote of 14-0 (and Indonesia abstaining), Resolution 1803 added persons and entities to those sanctioned; banned travel outright by certain sanctions persons; banned virtually all sales of dual use items to Iran; and authorized inspections of Iran Air Cargo and Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Line shipments, if there is cause to believe that the shipments contain banned goods. In May 2008, the P5+1 added political and enhanced energy cooperation with Iran to previous incentives, and the enhanced offer was attached as an Annex to Resolution 1929 (see below).

- Resolution 1835 (September 27, 2008). In July 2008, Iran it indicated it might be ready to accept a temporary "freeze for freeze": the P5+1 would impose no new sanctions and Iran would stop expanding uranium enrichment. No agreement on that concept was reached, even though the Bush Administration sent an Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs to a P5+1-Iran meeting in Geneva in July 2008. Resolution 1835 demanded compliance but did not add any sanctions.

Developments during the Obama Administration

The P5+1 met in February 2009 to incorporate the Obama Administration's stated commitment to direct U.S. engagement with Iran and,28in April 2009, U.S. officials announced that a U.S. diplomat would attend P5+1 meetings with Iran. In July 2009, the United States and its allies demanded that Iran offer constructive proposals by late September 2009 or face "crippling sanctions." A September 9, 2009, Iranian proposal was deemed a basis for further talks, and an October 1, 2009, P5+1-Iran meeting in Geneva produced a tentative agreement for Iran to allow Russia and France to reprocess 75% of Iran's low-enriched uranium stockpile for medical use. A draft agreement was approved by the P5+1 countries following technical talks in Vienna on October 19-21, 2009. However, the Supreme Leader reportedly opposed Iran's concessions as excessive and the agreement was not finalized.

In April 2010, Brazil and Turkey negotiated with Iran to revive the October arrangement. On May 17, 2010, the three countries signed a "Tehran Declaration" for Iran to send 2,600 pounds of low enriched uranium to Turkey in exchange for medically useful uranium.29 Iran submitted to the IAEA an acceptance letter, but the Administration rejected the plan as failing to address enrichment to the 20% level.

U.N. Security Council Resolution 1929

Immediately after the Brazil-Turkey mediation failed, then-Secretary of State Clinton announced that the P5+1 had reached agreement on a new U.N. Security Council Resolution that would give U.S. allies authority to take substantial new economic measures against Iran. Adopted on June 9, 2010,30 Resolution 1929, was pivotal insofar as it authorized U.N. member states to sanction key Iranian economic sectors such as energy and banking, thereby placing significant additional economic pressure on Iran. An annex presented a modified offer of incentives to Iran.31

Resolution 1929 produced no immediate breakthrough in talks. Negotiations on December 6-7, 2010, in Geneva and January 21-22, 2011, in Istanbul floundered over Iran's demand for immediate lifting of international sanctions. Additional rounds of P5+1-Iran talks in 2012 and 2013 (2012: April in Istanbul; May in Baghdad; and June in Moscow; 2013: Almaty, Kazakhstan, in February and in April) did not reach agreement on a P5+1 proposals that Iran halt enrichment to the 20% level; close the Fordow facility; and remove its stockpile of 20% enriched uranium.

Joint Plan of Action (JPA)

The June 2013 election of Rouhani as Iran's president improved the prospects for a nuclear settlement and, in advance of his visit to the U.N. General Assembly in New York during September 23-27, 2013, Rouhani stated that the Supreme Leader had given him authority to negotiate a nuclear deal. The Supreme Leader affirmed that authority in a speech on September 17, 2013, stating that he believes in the concept of "heroic flexibility"—adopting "proper and logical diplomatic moves.... "32 An agreement on an interim nuclear agreement, the "Joint Plan of Action" (JPA), was announced on November 24, 2013, providing modest sanctions relief in exchange for Iran to (1) eliminating its stockpile of 20% enriched uranium, (2) ceasing to enrich to that level, and (3) not increasing its stockpile of 3.5% enriched uranium.

The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)33

P5+1-Iran negotiations on a comprehensive settlement began in February 2014 but missed several self-imposed deadlines. On April 2, 2015, the parties reached a framework for a JCPOA, and the JCPOA was finalized on July 14, 2015. U.N. Security Council Resolution 2231 of July 20, 2015, endorsed the JCPOA and contains restrictions (less stringent than in Resolution 1929) on Iran's importation or exportation of conventional arms (for up to five years), and on development and testing of ballistic missiles capable of delivering a nuclear weapon (for up to eight years). On January 16, 2016, the IAEA certified that Iran completed the work required for sanctions relief and "Implementation Day" was declared.

The Trump Administration and the JCPOA

During the 2016 U.S. presidential election campaign, then-candidate Donald Trump was highly critical of the JCPOA and threatened to withdraw or renegotiate it. The Trump Administration has asserted that the JCPOA does not address key U.S. concerns about Iran's continuing "malign activities" in the region and it ballistic missile program, and might not be serving U.S. interests.34 The Administration continued to implement the deal and certified under the Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act (INARA, P.L. 114-17) that Iran is complying, while at the same time conducting a policy review. In interviews and based on press reports, President Trump indicated he might not certify Iran's compliance with the JCPOA at the next 90-day deadline on October 15—an action that could trigger a reimposition of U.S. sanctions and likely the collapse of the accord.35 During the U.N. General Assembly meetings in New York (September 18-21, 2017), which included a meeting on the sidelines of the P5+1 and Iran, Administration officials clarified the U.S. position as seeking either a modification of the JCPOA or a separate agreement that might extend the JCPOA's nuclear restrictions beyond current deadlines, limit Iran's development of ballistic missiles, and address Iran's "malign activities" in the region. On October 13, 2017, President Trump announced the results of the policy review and asked Congress and U.S. allies to address the JCPOA's weaknesses, including its lack of curbs on Iran's missile program or on Iran's support for regional armed factions—and threatened to end U.S. participation in the JCPOA unless such steps are taken. He did not certify Iranian compliance under INARA at the October 15 certification deadline. Iran has rejected any renegotiation of the JCPOA's terms, although Iranian leaders have reportedly signaled they might be willing to entertain talks about new limits on Iran's ballistic missile program.

Missile Programs and Chemical and Biological Weapons Capability

Iran has an active missile development program, as well as other WMD programs at varying stages of activity and capability, as discussed further below.

Chemical and Biological Weapons

U.S. reports indicate that Iran has the capability to produce chemical warfare (CW) agents and "probably" has the capability to produce some biological warfare agents for offensive purposes, if it made the decision to do so.36 This raises questions about Iran's compliance with its obligations under the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), which Iran signed on January 13, 1993, and ratified on June 8, 1997. Iran is widely believed to be unlikely to use chemical or biological weapons or to transfer them to its regional proxies or allies because of the potential for international powers to discover their origin and retaliate against Iran for any use.

Missiles37

U.S. officials assert that Iran's missile arsenal in the region, posing a potential threat to U.S. allies in the region, as well as to U.S. ships and forces in the region. DNI Coats testified on May 11, 2017, that "Iran's ballistic missiles are inherently capable of delivering WMD "and that Iran "already has the largest inventory of ballistic missiles in the Middle East." The intelligence directors added that Iran "can strike targets up to 2,000 kilometers from Iran's borders."

Still, Iran is not known to possess an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) capability (missiles of ranges over 2,900 miles). And, IRGC Commander-in-Chief Ali Jafari said in early October 2017 that the existing ranges of Iran's missiles are "sufficient for now," suggesting that Iran has no plans to develop an ICBM.38 If there is a decision to do so, progress on Iran's space program could shorten the pathway to an ICBM because space launch vehicles use similar technology. Iran's missile programs are run by the IRGC Air Force, particularly the IRGC Air Force Al Ghadir Missile Command—an entity sanctioned under Executive Order 13382. There are persistent reports that Iran-North Korea missile cooperation is extensive.

At the more tactical level, Iran is acquiring and developing many types of short range ballistic and cruise missiles that Iran's forces can use and transfer to regional allies and proxies to protect them and to enhance Iran's ability to project power. The DNI's May 11, 2017, testimony states that Iran "continues to develop a range of new military capabilities to monitor and target US and allied military assets in the region, including armed UAVs ... advanced naval mines, submarines and advanced torpedoes, and anti-ship and land-attack cruise missiles."

Resolution 2231 of July 20, 2015 (the only currently operative Security Council resolution on Iran) "calls on" Iran not to develop or test ballistic missiles "designed to be capable of" delivering a nuclear weapon, for up to eight years from Adoption Day of the JCPOA (October 18, 2015). The wording is far less restrictive than that of Resolution 1929, which clearly prohibited Iran's development of ballistic missiles. The JCPOA itself does not specifically contain ballistic missile restraints.

Iran has continued developing and testing missiles, despite Resolution 2231.

- On October 11, 2015, and reportedly again on November 21, 2015, Iran tested a 1,200-mile-range ballistic missile, which U.S. intelligence officials called "more accurate" than previous Iranian missiles of similar range. The tests occurred prior to the taking effect of Resolution 2231 on January 16, 2016 (Implementation Day).

- Iran conducted ballistic missile tests on March 8-9, 2016—the first such tests after Implementation Day.

- Iran reportedly conducted a missile test in May 2016, although Iranian media had varying accounts of the range of the missile tested.

- A July 11-21, 2016, test of a missile of a range of 2,500 miles, akin to North Korea's Musudan missile, reportedly failed. It is not clear whether North Korea provided any technology or had any involvement in the test.39

- On January 29, 2017, Iran tested what Trump Administration officials called a version of the Shahab missile, although press reports say the test failed when the missile exploded after traveling about 600 miles.

- On July 27, 2017, Iran's Simorgh rocket launched a satellite into space.

- On several occasions since the JCPOA was finalized, Iran has tested short-range ballistic missiles.

U.S. and U.N. Responses to Iran's Missile Tests

The Obama Administration termed Iran's post-Implementation Day ballistic missile tests as "provocative and destabilizing," "inconsistent with" Resolution 2231—stopping short of accusing Iran of "violation" of 2231. Trump Administration officials have used similar formulations for the tests in 2017, with the exception of the July 27 space launch - which the Administration termed a "violation" - because of that technology's inherent capability to carry a nuclear warhead. The U.N. Security Council referred the 2016 and 2017 tests to its sanctions committee but has not imposed any additional sanctions on Iran to date.

On several occasions in 2015 and 2016, the Obama Administration designated additional firms for sanctions under Executive Order 13382. The Trump Administration has, on several occasions, sanctioned Iran missile-related entities under E.O. 13382 and under the Iran, North Korea, and Syria Nonproliferation Act. And, as noted, the Countering America's Adversaries through Sanctions (P.L. 115-44), mandates sanctioning entities that assist Iran's missile program.

Section 1226 of the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (S. 2943, P.L. 114-328) requires the DNI, as well as the Secretary of State and the Secretary of the Treasury, to each submit quarterly reports to Congress on Iranian missile launches in the one preceding year, and on efforts, if any, to impose sanctions on entities assisting those launches. The provision sunsets on December 31, 2019.

Iran asserts that conventionally armed missiles are an integral part of its defense strategy and the tests will continue. Iran argues that it is not developing a nuclear weapon and therefore is not designing its missile to carry a nuclear weapon.

U.S. and Other Missile Defenses

Successive U.S. Administrations have sought to build up regional missile defense systems. The United States and Israel have a broad program of cooperation on missile defense as well as on defenses against shorter range rockets and missiles such as those Iran supplies to Lebanese Hezbollah. The United States has also long sought to organize a coordinated GCC missile defense system, building on the individual capabilities and purchases of each GCC country. The United States has sold the Patriot system (PAC-3) as the more advanced "THAAD" (Theater High Altitude Area Defense) to the Gulf states. In 2012, the United States emplaced an early-warning missile defense radar in Qatar that, when combined with radars in Israel and Turkey, would provide a wide range of coverage against Iran's missile forces.40

The United States has sought a defense against an eventual long-range Iranian missile system. U.S. efforts in that regard have focused on emplacing missile defense systems in various Eastern European countries and on ship-based systems. The FY2013 national defense authorization act (P.L. 112-239) contained provisions urging the Administration to undertake more extensive efforts, in cooperation with U.S. partners and others, to defend against the missile programs of Iran (and North Korea).

|

Shahab-3 |

The 800-mile range missile is operational, and Defense Department (DOD) reports indicate Tehran is improving its lethality and effectiveness. |

|

Shahab-3 "Variants" |

Iran appears to be developing several extended-range variants of the Shahab, under a variety of names including: Sijil, Ashoura, Emad, Ghadr, and Khorramshahr. The Ashoura is a solid fuel Shahab-3 variant with 1,200-1,500-mile range, which puts large portions of the Near East and Southeastern Europe in range. Some Shahab variants inscribed with the phrase "Israel must be wiped off the face of the earth"—were launched on March 8-9, 2016. |

|

BM-25/Musudan Variant |

This missile, with a reported range of up to 2,500 miles, is of North Korean design, and in turn based on the Soviet-era "SS-N-6" missile. Reports in 2006 that North Korea supplied the missile or components of it to Iran have not been corroborated, but Iran reportedly tried to test its own version of this missile in July 2016. |

|

Short Range Ballistic Missiles and Cruise Missiles |

Iran is fielding increasingly capable short-range ballistic and anti-ship cruise missiles, according to DOD reports, including the ability to change course in flight. One short-range ballistic missile (the Qiam) was first tested in August 2010. Iran has also worked on a 200 mile-range (Fateh 110) missile using solid fuel, a version of which is the Khaliji Fars (Persian Gulf) anti-ship ballistic missile. Iran also has armed its patrol boats with Chinese-made C-802 anti-ship cruise missiles and Iranian variants of that weapon. Iran also has C-802s and other missiles emplaced along Iran's coast, including the Chinese-made CSSC-2 (Silkworm) and the CSSC-3 (Seersucker). Iran also possesses a few hundred short-range ballistic missiles, including the Shahab-1 (Scud-b), the Shahab-2 (Scud-C), and the Tondar-69 (CSS-8). |

|

ICBMs |

An ICBM is a ballistic missile with a range of 5,500 kilometers (about 2,900 miles). After long estimating that Iran might have an ICBM capability by 2010, the U.S. intelligence community has not stated that Iran has produced an ICBM, to date. |

|

Space Vehicles |

In February 2009, Iran successfully launched a small, low-earth satellite on a Safir-2 rocket (range about 155 miles). Iran claimed additional satellite launches subsequently, including the launch and return of a vehicle carrying a small primate in December 2013. Since March 2016, Iran has been reported to readying the Simorgh vehicle for a space launch, and the launch occurred on July 27, 2017. |

|

Warheads |

Wall Street Journal report of September 14, 2005, said that U.S. intelligence believes Iran is working to adapt the Shahab-3 to deliver a nuclear warhead. Subsequent press reports said that U.S. intelligence captured an Iranian computer in mid-2004 showing plans to construct a nuclear warhead for the Shahab.41 No further information has been reported since. |

Conventional and "Asymmetric Warfare" Capability

Iran's leaders have repeatedly warned that Iran would take military action if Iran is attacked. Iran's forces are widely assessed as incapable of defeating the United States in a classic military confrontation, but they are potentially able to do significant damage to U.S. forces. Iran appears to be able to defend against any conceivable aggression from Iran's neighbors, while lacking the ability to deploy concentrated armed force across long distances or waterways. Iran is able to project power against U.S. and U.S.-allied interests in the region not necessarily through conventional military power but by supporting friendly governments and proxy forces.

Organizationally, Iran's armed forces are divided to perform functions appropriate to their roles. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC, known in Persian as the Sepah-e-Pasdaran Enghelab Islami)42 controls the Basij (Mobilization of the Oppressed) volunteer militia that has been the main instrument to repress domestic dissent. The IRGC also has a national defense role and it and the regular military (Artesh)—the national army that existed under the former Shah—report to a joint headquarters. On June 28, 2016, Supreme Leader Khamene'i replaced the longtime Chief of Staff (head) of the Joint Headquarters, Dr. Hassan Firuzabadi, with IRGC Major General Mohammad Hossein Bagheri, who was an early recruit to the IRGC and fought against Kurdish insurgents and in the Iran-Iraq War. About 56 years old, Bagheri, uncharacteristically of a senior IRGC figure, has generally not been outspoken on major issues,43 but the appointment of an IRGC officer to head the joint headquarters demonstrates the IRGC's dominance. On the other hand, Rouhani's August 2017 appointment of a senior Artesh figure, Brigadier General Amir Hatami, as Defense Minister for Rouhani's second term cabinet, suggests that the Artesh remains a viable and respected institution in Iran's defense establishment. The Artesh is deployed mainly at bases outside cities and has no internal security role.

The IRGC Navy and regular Navy (Islamic Republic of Iran Navy, IRIN) are distinct forces; the IRIN has responsibility for the Gulf of Oman, whereas the IRGC Navy has responsibility for the closer-in Persian Gulf and Strait of Hormuz. The regular Air Force controls most of Iran's combat aircraft, whereas the IRGC Air Force runs Iran's ballistic missile programs. Iran has a small number of warships on its Caspian Sea coast. Since 2014, Iran sent some warships into the Atlantic Ocean on a few occasions, presumably to try to demonstrate growing naval strength.

Military-Military Relationships and Potential New Arms Buys

Iran's armed forces have few formal relationships with foreign militaries outside the region. Iran's military-to-military relationships with Russia, China, Ukraine, Belarus, and North Korea generally have focused on Iranian arms purchases or upgrades. Iran and Russia are cooperating in Syria to assist the Asad regime's military effort against a multi-faceted armed rebellion. The cooperation expanded in August 2016 with Russia's bomber aircraft being allowed, for a brief time, use of Iran's western airbase at Hamadan to launch strikes in Syria—the first time the Islamic Republic gave a foreign military use of Iran's military facilities.44

Iran and India have a "strategic dialogue" and some Iranian naval officers reportedly underwent some training in India in the 1990s. Iran's military also conducted joint exercises with the Pakistani armed forces in the early 1990s. In September 2014, two Chinese warships docked at Iran's port of Bandar Abbas, for the first time in history, to conduct four days of naval exercises,45 and in October 2015, the leader of Iran's regular (not IRGC) Navy made the first visit ever to China by an Iranian Navy commander. In August 2017, the chief of Iran's joint military headquarters made the first top-level military visit to Turkey since Iran's 1979 revolution.

Sales to Iran of most conventional arms (arms on a U.N. Conventional Arms Registry) were banned by U.N. Resolution 1929. Resolution 2231 requires (for a maximum of five years from Adoption Day) Security Council approval for any transfer of weapons or military technology, or related training or financial assistance, to Iran. Defense Minister Hossein Dehgan visited Moscow in February 2016, reportedly to discuss possible purchases of $8 billion worth of new conventional arms, including T-90 tanks, Su-30 aircraft, attack helicopters, anti-ship missiles, frigates, and submarines. Such purchases would require Security Council approval under Resolution 2231, and U.S. officials have said the United States would use its veto power to deny approval for the sale.

Asymmetric Warfare Capacity

Iran tries to compensate for its conventional military deficiencies by developing a capacity for "asymmetric warfare." Defense Department reports and intelligence community testimony continues to assess that Iran is developing forces and tactics to control the approaches to Iran, including the Strait of Hormuz, and that the IRGC-QF remains a key tool of Iran's "foreign policy and power projection." Iran's naval strategy appears to be center on developing an ability to "swarm" U.S. naval assets with its fleet of small boats and large numbers of anti-ship cruise missiles and its inventory of coastal defense cruise missiles (such as the Silkworm or Seersucker). It is also developing increasingly lethal systems such as more advanced naval mines and "small but capable submarines," according to the 2016 DOD report. Iran has added naval bases along its coast in recent years, enhancing its ability to threaten shipping in the strait. As discussed further later in this report, IRGC Navy vessels frequently conduct "high-speed intercepts" or close-approaches of U.S. naval vessels in the Persian Gulf, sometimes causing U.S. evasive action or warning shots.

Iran's arming of regional allies and proxies represents another aspect of Iran's development of asymmetric warfare capabilities. The FY2016 DOD report on Iran's military power, cited earlier, states that "The IRGC-QF continues to seek improved access within foreign countries and to support proxy groups to advance Iran's interests." Arming allies and proxies helps Iran expand its influence with little direct risk, gives Tehran a measure of deniability, and serves as a "force multiplier." Iran's provision of anti-ship and coastal defense missiles to the Houthi rebels in Yemen, discussed further below, could represent an effort by Tehran to project military power into the key Bab el-Mandeb Strait chokepoint. In the event of confrontation, Iran could try to retaliate against an adversary through terrorist attacks inside the United States or against U.S. embassies and facilities in Europe or the Persian Gulf. Iran could also try to direct Iran-supported forces in Afghanistan or Iraq to attack U.S. personnel there. Iran's support for regional terrorist groups and other armed factions was a key justification for Iran's addition to the U.S. list of state sponsors of terrorism ("terrorism list") in January 1984.

|

Military and Security Personnel: 475,000+. Regular army ground force is about 350,000, Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) ground force is about 100,000. IRGC navy is about 20,000 and regular navy is about 18,000. Regular Air Force has about 30,000 personnel and IRGC Air Force (which runs Iran's missile programs) is of unknown size. Security forces number about 40,000-60,000 law enforcement forces, with another 600,000 Basij (volunteer militia under IRGC control) available for combat or internal security missions. |

|

Tanks: 1,650+ Includes 480 Russian-made T-72. Iran reportedly discussing purchase of Russian-made T-90s. |

|

Surface Ships and Submarines: 100+ (IRGC and regular Navy) Includes 4 Corvette; 18 IRGC-controlled Chinese-made patrol boats, several hundred small boats.) Also has 3 Kilo subs (reg. Navy controlled). Iran has been long said to possess several small subs, possibly purchased assembled or in kit form from North Korea. Iran claimed on November 29, 2007, to have produced a new small sub equipped with sonar-evading technology, and it deployed four Iranian-made "Ghadir class" subs to the Red Sea in June 2011. Iran reportedly seeks to buy from Russia additional frigates and submarines. |

|

Combat Aircraft/Helicopters: 330+ Includes 25 MiG-29 and 30 Su-24. Still dependent on U.S. F-4s, F-5s and F-14 bought during Shah's era. Iran reportedly negotiating with Russia to purchase Su-30s (Flanker) equipped with advanced air to air and air to ground missiles (Yakhont ant-ship missile). Iran reportedly seeks to purchase Russia-made Mi-17 attack helicopters. |

|

Anti-aircraft Missile Systems: Iran has 150+ U.S.-made I-Hawk (from Iran-Contra Affair) plus possibly some Stingers acquired in Afghanistan. Russia delivered to Iran (January 2007) 30 anti-aircraft missile systems (Tor M1), worth over $1 billion. In December 2007, Russia agreed to sell five batteries of the highly capable S-300 air defense system at an estimated cost of $800 million. Sale of the system did not technically violate U.N. Resolution 1929, because the system is not covered in the U.N. Registry on Conventional Arms, but Russia refused to deliver the system as long as that sanction remained in place. After the April 2, 2015, framework nuclear accord, Russian officials indicated they would proceed with the S-300 delivery, and delivery proceeded in 2016. Iran reportedly also seeks to buy the S-400 anti-aircraft system from Russia. |

|

Defense Budget: About 3% of GDP, or about $15 billion. The national budget is about $300 billion. |

Sources: IISS Military Balance (2016)—Section on Middle East and North Africa, and various press reports.

|

The IRGC is generally loyal to Iran's political hardliners and is clearly more politically influential than is Iran's regular military, which is numerically larger, but was held over from the Shah's era. The IRGC's political influence has grown sharply as the regime has relied on it to suppress dissent. A Rand Corporation study stated: "Founded by a decree from Ayatollah Khomeini shortly after the victory of the 1978-1979 Islamic Revolution, Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) has evolved well beyond its original foundations as an ideological guard for the nascent revolutionary regime.... The IRGC's presence is particularly powerful in Iran's highly factionalized political system, in which [many senior figures] hail from the ranks of the IRGC...." Its overall commander, IRGC Major General Mohammad Ali Jafari, who has been in the position since September 2007, is considered a hardliner against political dissent and a close ally of the Supreme Leader. He criticized Rouhani for accepting a phone call from President Obama on September 27, 2013, and opposed major concessions in the JCPOA negotiations. Militarily, the IRGC fields a ground force of about 100,000 for national defense. The IRGC Navy has responsibility to patrol the Strait of Hormuz and the regular Navy has responsibility for the broader Arabian Sea and Gulf of Oman (deeper waters further off the coast). The IRGC Air Force runs Iran's ballistic missile programs, but combat and support military aviation is operated exclusively by the regular Air Force, which has the required pilots and sustainment infrastructure for air force operations. The IRGC is the key organization for maintaining internal security. The Basij militia, which reports to the IRGC commander in chief, operates from thousands of positions in Iran's institutions and, as of 2008, has been integrated at the provincial level with the IRGC's provincial units. As of December 2016, the Basij is led by hardliner Gholam Hosein Gheibparvar. In November 2009, the regime gave the IRGC's intelligence units greater authority, surpassing that of the Ministry of Intelligence. Through its Qods (Jerusalem) Force (QF), the IRGC has a foreign policy role in exerting influence throughout the region by supporting pro-Iranian movements and leaders. The IRGC-QF commander, Brigadier General Qassem Soleimani, reportedly has an independent channel to Khamene'i. The IRGC-QF numbers approximately 10,000-15,000 personnel who provide advice, support, and arrange weapons deliveries to pro-Iranian factions or leaders in Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, Persian Gulf states, Gaza/West Bank, Afghanistan, and Central Asia. IRGC leaders have confirmed the QF is in Syria to assist the regime of Bashar al-Assad against an armed uprising, and it is advising the Iraqi government against the Islamic State (also known as ISIS or ISIL)—tacitly aligning it there with U.S. forces. Section 1223 of the FY2016 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 114-92) required a DOD report any U.S. military interaction with the IRGC-QF, presumably in Iraq. The IRGC-QF commander during 1988-1995 was Brigadier General Ahmad Vahidi, who served as defense minister during 2009-2013. He led the QF when it allegedly assisted Lebanese Hezbollah carry out two bombings of Israeli and Jewish targets in Buenos Aires (1992 and 1994) and is wanted by Interpol. He allegedly recruited Saudi Hezbollah activists later accused of the June 1996 Khobar Towers bombing. As noted, the IRGC is also increasingly involved in Iran's economy, acting through a network of contracting businesses it has set up, most notably Ghorb (also called Khatem ol-Anbiya, Persian for "Seal of the Prophet"). Active duty IRGC senior commanders reportedly serve on Ghorb's board of directors and its chief executive, Rostam Ghasemi, served as Oil Minister during 2011-2013. In 2009, the IRGC bought a 50% stake in Iran Telecommunication Company at a cost of $7.8 billion, although that firm was later privatized. The Wall Street Journal reported on May 27, 2014, that Khatam ol-Anbia has $50 billion in contracts with the Iranian government, including in the energy sector but also in port and highway construction. It has as many as 40,000 employees. Numerous IRGC and affiliated entities, including the IRGC itself and the QF, have been designated for U.S. sanctions as proliferation, terrorism supporting, and human rights abusing entities—as depicted in CRS Report RS20871, Iran Sanctions. The United States did not remove any IRGC-related designations under the JCPOA, but the EU will be doing so in about eight years. |

Sources: Frederic Wehrey et al.,"The Rise of the Pasdaran," Rand Corporation, 2009; Katzman, Kenneth, "The Warriors of Islam: Iran's Revolutionary Guard," Westview Press, 1993; Department of the Treasury; http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2013/09/30/130930fa_fact_filkins?printable=true¤tPage=all.

Iran's Regional and International Activities

The following sections analyze Iran's actions in its region and more broadly, in the context of Iran's national security strategy.

Near East Region

The focus of Iranian security policy is the Near East, where Iran employs all instruments of its national power. Successive Administrations have described many of Iran's regional operations as "malign activities." Testifying before the House Armed Services Committee on March 29, 2017, the commander of U.S. Central Command, responsible for most of the region, stated that "It is my view that Iran poses the greatest long-term threat to stability in this part of the world." It can be argued that U.S. efforts to limit Iran's strategic reach would require major new U.S. commitments in several conflict-torn countries in the region. President Trump did not announce any major new steps to counter Iran's malign activities in his October 13, 2017, announcement of his administration's Iran policy.

The Persian Gulf

|

|

Source: Created by CRS. |

Iran has a 1,100-mile coastline on the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman. The Persian Gulf monarchy states (Gulf Cooperation Council, GCC: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates) have always been a key focus of Iran's foreign policy. In 1981, perceiving a threat from revolutionary Iran and spillover from the Iran-Iraq War that began in September 1980, the six Gulf states—Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates—formed the GCC alliance. U.S.-GCC security cooperation, developed during the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War, expanded significantly after the 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Prior to 2003 the extensive U.S. presence in the Gulf was also intended to contain Saddam Hussein's Iraq, but, with Iraq militarily weak since the fall of Saddam Hussein, the U.S. military presence in the Gulf is focused mostly on containing Iran and conducting operations against regional terrorist groups. The GCC states host significant numbers of U.S. forces at their military facilities and procure sophisticated U.S. military equipment.

Some of the GCC leaders also accuse Iran of fomenting unrest among Shiite communities in the GCC states, particularly those in the Eastern Provinces of Saudi Arabia and in Bahrain, which has a majority Shiite population. At the same time, all the GCC states maintain relatively normal trading relations with Iran, and some have undertaken or considered joint energy and transportation projects with Iran. In early 2017, Iran sought to ease tensions with the GCC countries in an exchange of letters and visits arranged through the intermediation of Kuwait. The initiative produced a February 2017 visit by President Hassan Rouhani to Kuwait and Oman, but the same regional issues that divide Iran and the GCC countries sank the initiative.

The willingness of Qatar, Kuwait, and Oman to engage Iran contributed to a rift within the GCC in which Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Bahrain—joined by a few other Muslim countries—announced on June 5, 2017, an air, land, and sea boycott of Qatar.46 The rift has given Iran an opportunity to accomplish a long-standing goal of dividing the GCC states and weakening their alliance. Iran has, for example, increased its food exports to Qatar as that country looks for alternative sources of food imports other than Saudi Arabia, and in August 2017, Qatar restored full diplomatic relations with Tehran. The GCC rift came two weeks after President Donald Trump visited Saudi Arabia and expressed strong support for Saudi Arabia and for isolating Iran.

An additional U.S. and GCC concern is the Iranian threat to the long-asserted core U.S. interest to preserve the free flow of oil and freedom of navigation in the Persian Gulf, which is only about 20 miles wide at its narrowest point. The Strait of Hormuz is identified by the Energy Information Administration as a key potential "chokepoint" for the world economy. Each day, about 17 million barrels of oil flow through the strait, which is 35% of all seaborne traded oil and 20% of all worldwide traded oil.47 U.S. and GCC officials view Iran as the only realistic threat to the free flow of oil and freedom of navigation in the Persian Gulf and Strait of Hormuz. Some GCC states are developing oil export pipelines that avoid the Strait of Hormuz. In mid-2015, Iran stopped several commercial ships transiting the strait as part of an effort to resolve commercial disputes with the shipping companies involved—stoppages possibly intended to demonstrate Iran's potential ability to control the strait. The following sections analyze the main outlines of Iran's policy toward each GCC state.

Saudi Arabia48

Iranian leaders assert that Saudi Arabia seeks hegemony for its school of Sunni Islam and to deny Iran and Shiite Muslims influence in the region. Iranian aid to Shiite-dominated governments and to Shiites in Sunni-dominated countries aggravates sectarian tensions and has contributed to a war by proxy with Saudi Arabia,49 which asserts that it seeks to thwart an Iranian drive for regional hegemony. Iran's arming of the Houthi rebels in Yemen has also increased Iran's potential to threaten the Kingdom militarily, and Saudi Arabia blamed Iran directly for a Houthi-fired missile that was intercepted outside Riyadh in early November 2017, calling it "an act of war." Simultaneously, Saudi Arabia sought to undermine Hezbollah's influence in Lebanon by advising that country's Prime Minister, Sa'd Hariri, to resign as head of a coalition government that includes Hezbollah. On Iraq, both Iran and Saudi Arabia back the Shiite-dominated government, although Saudi leaders have criticized that government for sectarianism whereas Iran supports Baghdad relatively uncritically. Since mid-2017, Saudi leaders, with U.S. backing, have sought to engage Baghdad to draw it closer to the Arab world and away from Iran.

The Saudi-Iran rift expanded in January 2016 when Saudi Arabia severed diplomatic relations with Iran in the wake of violent attacks and vandalism against its embassy in Tehran and consulate in Mashhad, Iran. The attacks were a reaction to Saudi Arabia's January 2, 2016, execution of an outspoken Shia cleric, Nimr Baqr al Nimr, alongside dozens of Al Qaeda members; all had been convicted of treason and/or terrorism charges. Subsequently, Saudi Arabia and Bahrain broke diplomatic relations with Iran, and Qatar, Kuwait, and UAE recalled their ambassadors from Iran. In December 2016, Saudi Arabia executed 15 Saudi Shiites sentenced to death for "spying" for Iran.

Saudi officials repeatedly cite past Iran-inspired actions as a reason for distrusting Iran. These actions include Iran's encouragement of violent demonstrations at some Hajj pilgrimages in Mecca in the 1980s and 1990s, which caused a break in relations from 1987 to 1991. The two countries increased mutual criticism of each other's actions in the context of the 2016 Hajj. Some Saudis accuse Iran of supporting Shiite dissidents in the kingdom's restive Shiite-populated Eastern Province. Saudi Arabia asserts that Iran instigated the June 1996 Khobar Towers bombing and accuses it of sheltering the alleged mastermind of the bombing, Ahmad Mughassil, a leader of Saudi Hezbollah. Mughassil was arrested in Beirut in August 2015.

United Arab Emirates (UAE)50

The UAE has similarly takes a hard line against Iran, opposing extensive diplomatic engagement. UAE leaders blamed Iran for arming the Houthi rebels in Yemen that used Iran-supplied anti-ship missiles to damage a UAE naval vessel in the Bab el-Mandeb Strait in late 2016. As noted above, the UAE withdrew its ambassador from Iran in solidarity with Saudi Arabia in connection with the Nimr execution in January 2016.

The UAE is alone in the GCC in having a long-standing territorial dispute with Iran, concerning the Persian Gulf islands of Abu Musa and the Greater and Lesser Tunb islands. The Tunbs were seized by the Shah of Iran in 1971, and the Islamic Republic took full control of Abu Musa in 1992, violating a 1971 agreement to share control of that island. The UAE has sought to refer the dispute to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), but Iran insists on resolving the issue bilaterally. (ICJ referral requires concurrence from both parties to a dispute.) In 2013-2014, the two countries held direct apparently productive discussions on the issue and Iran reportedly removed some military equipment from the islands.51 However, no resolution has been announced. The GCC has consistently backed the UAE position.

Despite their political and territorial differences, the UAE and Iran maintain extensive trade and commercial ties. Iranian-origin residents of Dubai emirate number about 300,000, and many Iranian-owned businesses are located there, including branch offices of large trading companies based in Tehran and elsewhere in Iran.

Qatar52

Since 1995, Qatar has occupied a "middle ground" between anti-Iran animosity and sustained engagement with Iran. Qatar maintains periodic high-level contact with Iran; the speaker of Iran's Majles (parliament) visited Qatar in March 2015 and the Qatari government allowed him to meet with Hamas leaders in exile there. Qatar also pursues policies that are opposed to Iran's interests, for example by providing arms and funds to factions in Syria opposed to Syrian President Bashar Al Asad and by joining Saudi-led military intervention in Yemen (which ceased after Qatar pulled out of Yemen as a consequence of the intra-GCC rift). Qatar has sometimes used its engagement with Iran to obtain the release of prisoners held by Iran or its allies, and strongly refutes Saudi-led assertions that it is aligned with or politically close to Iran. Qatar did withdraw its Ambassador from Iran in connection with the Nimr execution discussed above, but restored relations in August 2017 in large part to reciprocate Iran's support for Qatar in the intra-GCC rift.

Qatar does not have territorial disputes with Iran, but Qatari officials reportedly remain wary that Iran could try to encroach on the large natural gas field Qatar shares with Iran (called North Field by Qatar and South Pars by Iran). In April 2004, the Iran's then-deputy oil minister said that Qatar is probably producing more gas than "her right share" from the field.

Bahrain53

Bahrain, ruled by the Sunni Al Khalifa family and still unsettled by unrest among its majority Shiite population, is a strident critic of Iran. Bahrain's leaders consistently allege that Iran is agitating Bahrain's Shiite community, some of which is of Persian origin, to try to overturn Bahrain's power structure. In 1981 and again in 1996, Bahrain publicly claimed to have thwarted Iran-backed efforts by Bahraini Shiite dissidents to violently overthrow the ruling family. Bahrain has consistently accused Iran of supporting radical Shiite factions that are part of a broader and mostly peaceful uprising begun in 2011 by mostly Shiite demonstrators.54 On several occasions, Bahrain has temporarily withdrawn its Ambassador from Iran following Iranian criticism of Bahrain's treatment of its Shiite population or alleged Iranian involvement in purported anti-government plots. In June 2016, Iran used Bahrain's measures against key Shiite opposition leaders to issue renewed threats against the Al Khalifa regime. Bahrain broke ties with Iran in concert with Saudi Arabia in January 2016 over the Nimr execution dispute.

Some reports in indicate that Iran's efforts to support violent factions in Bahrain includes providing weapons, explosives, and weapons-making equipment. In late 2016, Bahraini authorities uncovered a large warehouse containing equipment, apparently supplied by Iran, that is tailored for constructing "explosively-forced projectiles" (EFPs) such as those Iran-backed Shiite militias used against U.S. armor in Iraq during 2004-2011. No EFPs have actually been used in Bahrain, to date.55 On January 1, 2017, 10 detainees who had been convicted of militant activities such as those discussed above broke out of Bahrain's Jaw prison with the help of attackers outside the jail. In late March 2017, security forces arrested a group of persons that authorities claimed were plotting to assassinate senior government officials and "community figures," asserting that the cell received military training by IRGC-QF. On March 17, 2017, the State Department named two members of a Bahrain militant group, the Al Ashtar Brigades, as Specially Designated Global Terrorists (SDGTs), asserting the group is funded and supported by Iran.56 The State Department report on international terrorism for 2016, released in July 2017, contained findings similar to those of the report for 2015, stating that

Iran has provided weapons, funding, and training to Bahraini militant Shia groups that have conducted attacks on the Bahraini security forces. On January 6, 2016, Bahraini security officials dismantled a terrorist cell, linked to IRGC-QF, planning to carry out a series of bombings throughout the country.

Tensions also have flared occasionally over Iranian attempts to question the legitimacy of a 1970 U.N.-run referendum in which Bahrainis chose independence rather than affiliation with Iran. In March 2016, a former IRGC senior commander and adviser to Supreme Leader Khamene'i reignited the issue by saying that Bahrain is an Iranian province and should be annexed.57

Kuwait58

Kuwait cooperates with U.S.-led efforts to contain Iranian power and is participating in Saudi-led military action against Iran-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen, but it also has tried to mediate a settlement of the Yemen conflict and broker a GCC-Iran rapprochement. Kuwait appears to view Iran as helpful in stabilizing Iraq, a country that occupies a central place in Kuwait's foreign policy because of Iraq's 1990 invasion. Kuwait has extensively engaged Iraq's Shiite leaders despite criticism of their marginalization of Sunni Iraqis. Kuwait also exchanges leadership-level visits with Iran; Kuwait's Amir Sabah al-Ahmad Al Sabah visited Iran in June 2014, meeting with Rouhani and Supreme Leader Khamene'i. Kuwait's Foreign Minister visited Iran in late January 2017 to advance Iran-GCC reconciliation, and Rouhani visited Kuwait (and Oman) in February 2017 as part of that abortive effort.

Kuwait is differentiated from some of the other GCC states by its integration of Shiites into the political process and the economy. About 25% of Kuwaitis are Shiite Muslims, but Shiites have not been restive there and Iran was not able to mobilize Kuwaiti Shiites to end Kuwait's support for the Iraqi war effort in the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988). At the same time, on numerous occasions, including in 2016, Kuwaiti courts have convicted Kuwaitis with spying for the IRGC-QF or Iran's intelligence service. Kuwait recalled its Ambassador from Iran in connection with the Saudi-Iran dispute over the Saudi execution of Al Nimr.

Oman59

Omani officials assert that engagement with Iran is a more effective means to moderate Iran's foreign policy than to isolate or threaten Iran, and Oman has the most consistent and extensive engagement with Iran's leadership. Omani leaders express gratitude for the Shah's sending of troops to help the Sultan suppress rebellion in the Dhofar region in the 1970s, even though Iran's regime changed since then.60 In March 2014, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani visited Oman, and he visited again in February 2017 along with Kuwait (see above). Sultan Qaboos visited Iran in August 2013, reportedly to explore with the newly elected Rouhani concepts for improved U.S.-Iran relations and nuclear negotiations that ultimately led to the JCPOA. His August 2009 visit there was controversial because it coincided with large protests against alleged fraud in the reelection of then-President Mahmud Ahmadinejad. Since sanctions on Iran were lifted, Iran and Oman have accelerated their joint development of the Omani port of Duqm, which Iran envisions as a trading and transportation outlet for Iran. Since late 2016, Oman also has been an repository of Iranian heavy water, the export of which is needed for Iran to comply with the JCPOA.

Oman has not supported any factions fighting the Asad regime in Syria and has not joined the Saudi-led Arab intervention in Yemen, enabling Oman to undertake the role of mediator in both of those conflicts. Oman has denied that Iran has used its territory to smuggle weaponry to the Houthi rebels in Yemen that Iran is supporting. Oman was the only GCC country to not downgrade its relations with Iran in connection with the January 2016 Nimr dispute. And, Oman has drawn closer to Iran in 2017 because of Iran's support for Qatar in the intra-GCC rift, which Omani leaders reportedly perceived as a precipitous and misguided action by Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

U.S.-GCC Consultations on Iran

In 2015, the JCPOA caused GCC concerns that the United States might be reducing its commitment to Gulf security. President Obama and the GCC leaders held two summit meetings—in May 2015 and April 2016—apparently intended to reassure the GCC of U.S. support against Iran. The statement following the 2015 summit at Camp David stated

In the event of [ ] aggression or the threat of [ ] aggression [against the GCC states], the United States stands ready to work with our GCC partners to determine urgently what action may be appropriate, using the means at our collective disposal, including the potential use of military force, for the defense of our GCC partners.61

The summit meetings produced announcements of a U.S.-GCC strategic partnership and specific commitments to (1) facilitate U.S. arms transfers to the GCC states; (2) increase U.S.-GCC cooperation on maritime security, cybersecurity, and counterterrorism; (3) organize additional large-scale joint military exercises and U.S. training; and (4) implement a Gulf-wide coordinated ballistic missile defense capability, which the United States has sought to promote in recent years.62 Perhaps indicating reassurance, the GCC states expressed support for the JCPOA.63

The Trump Administration's characterization of Iran as a major regional threat and its assertions that the JCPOA has not brought peace and security to the region has eased the concerns about U.S. policy toward Iran among the GCC states that take a hard-line on Iran. The GCC states have expressed reassurance from the Trump Administration's relaxation of restrictions on arms sales to the GCC states—an indication of an inclination to prioritize defense ties to the GCC states over concerns over GCC human rights practices or other issues. At the same time, no GCC now advocates that the United States withdraw from the JCPOA, asserting that it is an established feature whose termination would promote additional regional instability.

The recent U.S.-GCC meetings expanded on a long process of formalizing a U.S.-GCC strategic partnership, including a "U.S.-GCC Strategic Dialogue" inaugurated in March 2012. Earlier, in February 2010, then-Secretary Clinton also raised the issue of a possible U.S. extension of a "security umbrella" or guarantee to regional states against Iran.64 However, no such formal U.S. security pledge was issued.

U.S. Military Presence and Security Partnerships in the Gulf