Introduction

The iconography of the Confederate states in the U.S. Civil War is a contested part of American historical memory.1 Confederate flags, statues, plaques, and similar memorials have been valued historical symbols for some Americans, but for others have symbolized oppression and discrimination. Further, Confederate symbols2 have sometimes been associated with violent confrontations and hate crimes in the United States, including in recent years. Recent prominent incidents in which Confederate symbols were invoked—in particular, the June 2015 shooting deaths of nine people in a historically black church in Charleston, SC, and violence at an August 2017 rally in Charlottesville, VA—have led to renewed consideration of the presence of Confederate symbols in public spaces. Some local and state governments have elected to remove Confederate statues, flags, and other symbols from places of public prominence.3

Congress is considering the role of Confederate symbols on federal lands and in federal programs. While no comprehensive inventory of such symbols exists, numerous federal agencies administer assets or fund activities in which Confederate memorials and references to Confederate history are present. The National Park Service (NPS, within the Department of the Interior), the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and the Department of the Army within the Department of Defense (DOD) all administer national cemeteries that sometimes display the Confederate flag. Many units of the National Park System are related to Civil War history and contain resources commemorating Confederate soldiers or actions. The Army has military installations named in honor of Confederate generals, and some Navy ships have historically been named after Confederate officers or battles.4 The U.S. Capitol complex contains works commemorating Confederate soldiers and officials, including statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection.5 Various federal agencies such as the General Services Administration and the Department of Transportation are connected with sites of Confederate commemoration, either on federal properties or through nonfederal activities that receive federal funding.

The presence of Confederate symbols on federal lands, and at some nonfederal sites that receive federal funding, may raise multiple questions for Congress. How should differing views on the meaning of these symbols be addressed? Which symbols, if any, should be removed from federal sites, and which, if any, should be preserved for their historical or honorary significance?6 Should every tribute to a person who fought for the Confederacy be considered a Confederate symbol? Should federal agencies give additional attention to education and dialogue about the conflicted history of these symbols—including their role in Civil War history and in subsequent historical eras—or are current interpretive efforts adequate? How, if at all, should current practices of honoring the Confederate dead in national cemeteries be changed? To what extent, if any, should the presence of Confederate symbols at nonfederal sites affect federal funding for programs connected to these sites?

This report focuses primarily on Confederate symbols administered by three federal entities—NPS, the VA, and DOD. Each of these entities manages multiple sites or programs that involve Confederate symbols. The report begins with a discussion of recent legislative proposals, and then discusses the agencies' current policies with respect to Confederate symbols, along with issues for Congress.

Recent Legislation

Bills in recent Congresses have addressed Confederate symbols and their relation to federal lands and programs. The 115th Congress is considering bills with varying provisions on Confederate commemorative works, names, and other symbols under federal jurisdiction. The 114th Congress also considered several legislative proposals, but none were enacted in law. Of the pending proposals in the 115th Congress, some might be relatively straightforward to implement, while others might give rise to questions about implementation. Depending on specific bill provisions, such questions could include what constitutes a Confederate symbol, how required agency actions toward Confederate symbols would be funded, whether or not a given display of a symbol would qualify as a historical or educational context, and how implementation would be affected by statutory requirements for historic preservation and other existing protections.

115th Congress

In the 115th Congress, H.R. 3660, the No Federal Funding for Confederate Symbols Act, would prohibit the use of federal funds for the creation, maintenance, or display of any Confederate symbol on any federal property. The term "Confederate symbol" is defined to include Confederate battle flags, any symbols or signs that honor the Confederacy, and any monuments or statues that honor the Confederacy or its leaders or soldiers. The bill specifies that the funding prohibition would not apply if the Confederate symbol is in a museum or educational exhibit, or if the funds are being used to remove the symbol from the federal site. Additionally, H.R. 3660 would direct the Secretary of Defense to rename 10 military installations that are currently named for Confederate military leaders.7

H.R. 3658, the Honoring Real Patriots Act of 2017, would require the Secretary of Defense to change the name of any military installation or other property under DOD jurisdiction that is currently named after any individual who took up arms against the United States during the American Civil War or any individual or entity that supported such efforts.

H.R. 3779 would direct the Secretary of the Interior to develop a plan for the removal of the monument to Robert E. Lee at Antietam National Battlefield in Maryland. H.R. 3701 and S. 1772 would require the Architect of the Capitol to arrange for the removal from the National Statuary Hall Collection of statues of persons who voluntarily served the Confederate States of America.

H.Res. 12 would express the sense of the House of Representatives that the United States can achieve a more perfect union through avoidance and abatement of government speech that promotes or displays symbols of racism, oppression, and intimidation. The resolution would express support for the Supreme Court's conclusion in Walker v. Sons of Confederate Veterans that messages on state-issued license plates constitute government speech that is not protected by the First Amendment.8

During House consideration of H.R. 3354, the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies appropriations bill for FY2018, a number of amendments were submitted regarding Confederate symbols. These amendments would have prohibited funds from being used to create, maintain, or otherwise finance Confederate symbols, each under varying circumstances.9 None of these amendments were made in order by the House Committee on Rules.

114th Congress

In the 114th Congress, amendments to the FY2016 and FY2017 House Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies appropriations bills would have addressed the display and sale of Confederate flags at NPS units, including NPS national cemeteries. H.Amdt. 592 to H.R. 2822, the House Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies appropriations bill for FY2016, would have prohibited the use of funds in the bill to implement NPS policies that allow Confederate flags to be displayed at certain times in national cemeteries. An opposing amendment, H.Amdt. 651, would have prohibited funds from being used to contravene NPS policies on Confederate flags. H.Amdt. 586 would have prohibited NPS from using funds to administer contracts with park partners that sell items in NPS gift shops displaying a Confederate flag as a stand-alone feature. H.Amdt. 606 would have prohibited funds from being used by NPS to purchase or display a Confederate flag at any of its sites, except in situations where the flag would provide historical context. None of these amendments were ultimately included in P.L. 114-113, the Consolidated Appropriations Act for FY2016. Several similar amendments were submitted in the following year for H.R. 5538, the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies appropriations bill for FY2017, but were not made in order by the House Committee on Rules.10

Separately, an amendment to the FY2017 Military Construction and Veterans Affairs and Related Agencies appropriations bill addressed VA policies on display of the Confederate flag at its national cemeteries. H.Amdt. 1064 to H.R. 4974 would have prohibited funds in the bill from being used by the VA to implement its policy that permitted a Confederate flag to fly from a flagpole at certain times.11 The House of Representatives passed the bill as amended, but the Confederate flag provision was not included in the final omnibus appropriations legislation and did not become law.12 Another bill in the 114th Congress, H.R. 3007, would have prohibited the display of the Confederate battle flag in any VA national cemetery, but also was not enacted.

H.R. 4909, the House version of the National Defense Authorization Act for FY2017, included a provision to prohibit military departments from having Senior Reserve Officers' Training Corps units at educational institutions that displayed Confederate battle flags. The provision was included in the House-passed version of the bill but not in the enacted law, P.L. 114-328.

Also in the 114th Congress, S. 1689 would have reduced the amounts available to a state under the federally funded National Highway Performance Program and Surface Transportation Program if the state issued a license plate containing the image of a flag of the Confederate States of America. H.Res. 341 and H.Res. 355 would have required the Speaker of the House to remove any state flag containing a portion of the Confederate battle flag from the House wing of the Capitol or any House office building, except when displayed in Member offices. H.Res. 344 would have expressed the sense of the House urging states to remove the Confederate battle flag from public locations, to discontinue the use of the flag in government speech contexts (such as on license plates), and to remove depictions of the Confederate flag from their state flags, and urging businesses to discontinue selling Confederate battle flags and related merchandise. H.Res. 342 contained provisions similar to those that were later introduced as H.Res. 12 in the 115th Congress (see above).

National Park Service Policies and Issues

NPS manages over 70 units of the National Park System related to Civil War history, some of which contain works commemorating Confederate soldiers or actions.13 Additionally, NPS administers 14 national cemeteries that, under agency policy, may display the Confederate flag at certain times of year.14 The agency also provides education and interpretation related to Civil War history and the Confederate states. Park gift shops operated by concessioners sometimes sell books or other items that display Confederate symbols. Further, NPS is connected with historic preservation of some nonfederal Confederate memorials through its assistance to nonfederal sites such as national heritage areas, national historic landmarks, and nonfederal properties on the National Register of Historic Places. In the wake of recent incidents, these aspects of the NPS portfolio have come under scrutiny.

Confederate Commemorative Works in the National Park System

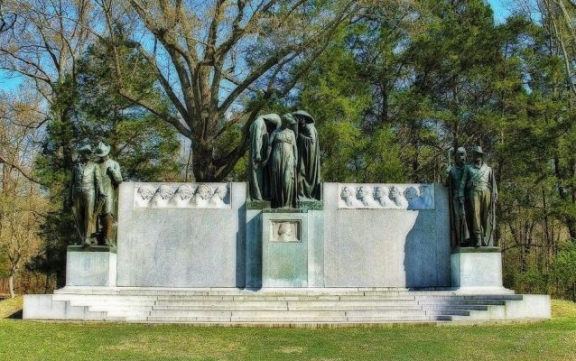

NPS has no comprehensive inventory of commemorative works at park sites—such as statues, plaques, and similar memorials—that relate to Confederate history.15 Confederate commemorative works are found at numerous NPS battlefields and other Civil War-related park units.16 Many of these works (such as the monument shown in Figure 1) are listed on, or are eligible for listing on, the National Register of Historic Places, and thus are afforded certain protections under the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA).17 In particular, Section 106 of the NHPA requires agencies to undertake consultations before taking actions that may adversely affect these listed or eligible historic properties, and Section 110(f) of the act provides similar, but stronger, protections for historic properties that have been designated as national historic landmarks.18 Some Confederate commemorative works in parks are not eligible for historic property designations, for example because they were constructed relatively recently.19

NPS policies govern the establishment and removal of commemorative works in national park units (except in the District of Columbia, where the Commemorative Works Act applies).20 Under NPS policy, new commemorative works in park units must be authorized by Congress or approved by the NPS Director. In Civil War parks, the policies preclude approval unless a work is specifically authorized by Congress or "would commemorate groups that were not allowed to be recognized during the commemorative period."21 Many Confederate commemorative works currently in NPS units would not have been subject to the NPS policies at the time of their establishment, because they were erected prior to NPS acquisition of the land.22

|

Figure 1. Confederate Monument, Shiloh National Military Park, Tennessee |

|

|

Source: National Park Service, "Shiloh Battlefield—Confederate Monument," at https://www.nps.gov/resources/place.htm%3Fid%3D79. Note: The monument is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. |

Concerning removal of commemorative works from NPS units, the agency's policies state the following:

Many commemorative works have existed in the parks long enough to qualify as historic features. A key aspect of their historical interest is that they reflect the knowledge, attitudes, and tastes of the persons who designed and placed them. These works and their inscriptions will not be altered, relocated, obscured, or removed, even when they are deemed inaccurate or incompatible with prevailing present-day values. Any exceptions from this policy require specific approval by the Director.23

NPS could face a number of constraints in considering removal of a Confederate commemorative work, depending on specific circumstances. Some commemorative works were established pursuant to acts of Congress, and thus could not be removed administratively by NPS.24 In other cases, such as those where the works existed prior to a park's establishment, requirements in park-establishing legislation that NPS preserve the park unit's resources, as well as historic property protections under the NHPA if a commemorative work is eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, could constrain the agency's options for removal.25 Broadly, NPS's mission under its Organic Act is to "conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life" in park units and to provide for their use "in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations."26 This fundamental mission could be seen as being at odds with potential administrative actions to remove existing works from park units. NPS could thus conclude that congressional legislation would be required to authorize the removal of particular works. Press reports following the August 2017 incidents in Charlottesville quoted NPS as stating that the agency "is committed to safeguarding these memorials while simultaneously educating visitors holistically and objectively about the actions, motivations, and causes of the soldiers and states they commemorate."27

In addition to structures such as monuments and memorials, some national park units have flown Confederate flags in various contexts, such as in battle reenactments. Prior to June 2015, NPS did not have a specific policy regarding the display of the Confederate flag outside of national cemeteries.28 After the Charleston, SC, shooting in 2015, then-NPS Director Jonathan Jarvis stated the following in a policy memorandum:

Confederate flags shall not be flown [NPS emphasis] in units of the national park system and related sites with the exception of specific circumstances where the flags provide historical context, for instance to signify troop location or movement or as part of a historical reenactment or living history program. All superintendents and program managers should evaluate how Confederate flags are used in interpretive and educational media, programs, and historical landscapes and remove the flags where appropriate.29

This policy remains in effect unless rescinded or amended.

Confederate Flags in NPS National Cemeteries

NPS administers 14 national cemeteries, mainly related to the Civil War.30 NPS cemeteries contain graves of both Union and Confederate soldiers. Under NPS policies, they are administered "to preserve the historic character, uniqueness, and solemn nature of both the cemeteries and the historical parks of which they are a part."31

NPS policies address the display of Confederate flags at the graves of Confederate soldiers in NPS national cemeteries.32 The policies allow the Confederate flag to be displayed in some national cemeteries on two days of the year. If a state observes a Confederate Memorial Day, NPS cemeteries in the state may permit a sponsoring group to decorate the graves of Confederate veterans with small Confederate flags. Additionally, such flags may also be displayed on the nationally observed Memorial Day, to accompany the U.S. flag on the graves of Confederate veterans. In both cases, a sponsoring group must provide and place the flags, and remove them as soon as possible after the end of the observance, all at no cost to the federal government. At no time may a Confederate flag be flown on an NPS cemetery flagpole.33

Following the June 2015 shootings in Charleston, House Members addressed the display of Confederate flags at NPS cemeteries in proposed amendments to Interior appropriations bills for both FY2016 and FY2017. The amendments are described in the "Recent Legislation" section of this report.

Sale of Confederate-Themed Items in NPS Gift Shops

Some NPS units have shops operated by concessioners, cooperating associations, or other partners, which sell items related to the themes and features of the park. Following the June 2015 shootings in Charleston, both NPS and Congress addressed the sale of Confederate-themed items in NPS shops, particularly items displaying the Confederate flag. NPS asked its concessioners and other partners to voluntarily end sales of items that "depict a Confederate flag as a stand-alone feature, especially items that are wearable and displayable." NPS specified that "books, DVDs, and other educational and interpretive media where the Confederate flag image is depicted in its historical context may remain as sales items as long as the image cannot be physically detached."34

During consideration of FY2016 and FY2017 Interior appropriations, House Members introduced amendments concerning sales of Confederate-themed items in NPS facilities. See the "Recent Legislation" section for more information.

NPS Heritage Partnership and Historic Preservation Programs

NPS's responsibilities include assisting states, localities, and private entities with heritage and historic preservation efforts. NPS provides financial and technical assistance to congressionally designated national heritage areas, which consist primarily of nonfederal lands in which conservation efforts are coordinated by state, local, and private entities.35 Some heritage areas encompass sites with commemorative works and symbols related to the Confederacy.36

NPS also administers national historic landmark designations and the National Register of Historic Places. Through these programs, the Secretary of the Interior confers historic preservation designations primarily on nonfederal sites.37 The designations provide certain protections to the properties and make them eligible for preservation grants and technical preservation assistance. Some nonfederal sites commemorating the Confederacy have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and some have been designated as national historic landmarks. In debates about removing Confederate symbols at the state and local levels, these NPS-designated sites are sometimes involved. For example, the Monument Avenue Historic District in Richmond, VA, which contains a series of monuments to Confederate officers, is a national historic landmark district that has been the subject of debate.38 As discussed above, National Register properties and national historic landmarks have some protections under Sections 106 and 110 of the NHPA.39 However, the designations do not prohibit nonfederal landowners from altering or removing their properties. Only if federal funding or licensing were required for such actions would the NHPA protections be invoked.

Issues for Congress

Members of Congress have been divided on the appropriate role of Confederate symbols in the National Park System. Some legislation has sought to withhold funding for the maintenance of any Confederate symbols in national park units, other legislation to withhold funding for certain NPS uses of Confederate symbols outside of a historic context, other legislation to remove particular Confederate symbols, and still other legislation to maintain the status quo in terms of these symbols' presence in the park system. Also divisive has been the question of the periodic display of Confederate flags on headstones in NPS national cemeteries.

Proposals concerning Confederate symbols at NPS sites arise in the context of the agency's mission to preserve its historic and cultural resources unimpaired for future generations. Absent congressional authorization, NPS's preservation mandates could constrain the agency from taking administrative actions desired by some, such as removing Confederate commemorative works from NPS units. Under both the Obama and Trump Administrations, NPS has expressed that some Confederate symbols in park units are required to be preserved under NPS statutes and can be framed and interpreted appropriately through educational activities.40 At the same time, the Obama Administration took steps to discourage or end some other uses of Confederate symbols—in particular the use of the Confederate flag in a "stand-alone" context.41 This policy has remained in place under the Trump Administration.

If Congress desired to remove Confederate commemorative works in the National Park System, another consideration would be how to fund the removals. NPS, which faces a sizable backlog of deferred maintenance, has stated that it generally lacks funds to dispose of unneeded or unwanted assets.42

Department of Veterans Affairs Policies and Issues

National Cemeteries

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) administers 135 national cemeteries and 33 soldier's lots and memorial areas in private cemeteries through the National Cemetery Administration (NCA). All cemeteries administered by the NCA are "considered national shrines as a tribute to our gallant dead."43

The first national cemeteries were developed during the Civil War and were administered by the military.44 Over time, the federal government created new national cemeteries and took control of cemeteries that previously had been administered privately or by the states. The NCA was created in 1973 when all national cemeteries then administered by the Army, with the exception of Arlington National Cemetery and Soldier's Home National Cemetery in Washington, DC, were transferred to the VA.45

Numerous national cemeteries and lots contain the remains of former Confederate soldiers and sailors, including those who died while being held prisoner by the United States or in federal hospitals during the Civil War.46 Under current law, however, persons whose only military service was in the Confederate army or navy are not eligible for interment in national cemeteries.47

State Veterans' Cemeteries

The NCA is authorized to provide grants to state, territorial, or tribal governments to assist with the establishment of state veterans' cemeteries.48 These grants may be used only for establishing, expanding, or improving cemeteries and cannot be used for land acquisition or regular operating expenses. State veterans' cemeteries that receive federal grants must adhere to federal law regarding eligibility for interment, but may add additional restrictions on eligibility such as residency requirements. Thus, since Confederate veterans are not eligible for interment in national cemeteries, they are also not eligible for interment in state veterans' cemeteries that receive federal grants.

Monuments and Memorials in National Cemeteries

Federal law permits the VA to accept monuments and memorials donated by private entities and to maintain these monuments and memorials in national cemeteries, including those dedicated to individuals or groups.49 The VA website identifies 34 monuments and memorials in national cemeteries that explicitly honor Confederate soldiers, sailors, political leaders, or veterans.50 Some of these monuments and memorials predate federal control of the cemeteries where they are located. For example, one of the Confederate monuments at Point Lookout Confederate Cemetery in Maryland was erected before the state transferred control of that cemetery to the federal government. Other monuments and memorials were more recently established, such as the Confederate monument erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Sons of Confederate Veterans in 2005 at Camp Butler National Cemetery in Illinois. Table 1 provides a list of national cemeteries with Confederate monuments and memorials and the dates, if available, of their establishment.

Table 1. Confederate Monuments and Memorials in National Cemeteries Administered by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)

|

State |

National Cemetery |

Number of Monuments and Memorials |

Dates of Establishment of Monuments and Memorials |

|

Alabama |

Mobile National Cemetery |

1 |

1940 |

|

Arkansas |

Fort Smith National Cemetery |

1 |

Not listed |

|

Little Rock National Cemetery |

1 |

1884 |

|

|

Illinois |

Camp Butler National Cemetery |

1 |

2005 |

|

Confederate Mound |

1 |

Not listed |

|

|

North Alton Confederate Cemetery |

1 |

1909 |

|

|

Rock Island Confederate Cemetery |

5 |

2003; 4 monuments not listed |

|

|

Indiana |

Crown Hill Confederate Mound |

1 |

1933 (updated 1993) |

|

Woodlawn Monument Site |

1 |

1912 |

|

|

Maryland |

Loudon Park National Cemetery |

1 |

1912 (approx.) |

|

Point Lookout Confederate Cemetery |

2 |

1876, 1910 |

|

|

Missouri |

Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery |

1 |

1988 |

|

Springfield National Cemetery |

1 |

1901 |

|

|

Union Confederate Monument Site |

1 |

Not listed |

|

|

New Jersey |

Finn's Point National Cemetery |

1 |

1910 |

|

New Mexico |

Santa Fe National Cemetery |

1 |

1993 |

|

New York |

Woodlawn National Cemetery |

2 |

1911,a 1937 |

|

Ohio |

Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery |

2 |

1897, 1902 |

|

Confederate Stockade Cemetery |

4 |

1910, 1925 (2 monuments), 2003 |

|

|

Pennsylvania |

Philadelphia National Cemetery |

1 |

1911 |

|

South Carolina |

Beaufort National Cemetery |

1 |

1997 |

|

Virginia |

Ball's Bluff National Cemetery |

1 |

Not listed |

|

Hampton National Cemetery |

1 |

Not listed |

|

|

Wisconsin |

Fort Crawford Cemetery Soldiers' Lot |

1 |

1930s (approx.) |

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS) compilation of data from the website of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) at https://www.cem.va.gov/cem/cems/allnational.asp.

Note: The VA does not list the dates of establishment for all monuments and memorials.

a. The Shohola Monument, erected in 1911, commemorates the deaths of Union and Confederate soldiers in a railroad accident in Pennsylvania during the Civil War.

Headstones and Grave Markers

Veterans interred in national cemeteries, or in state or private cemeteries, are generally eligible for headstones or grave markers provided at no cost by the VA.51 For Confederate veterans, government headstones or grave markers may be provided only if the grave is currently unmarked. The person requesting a headstone for a Confederate veteran may select a standard VA headstone, which includes identifying information about the veteran and his or her service and an emblem of belief corresponding to the veteran's faith, or a special Confederate headstone that includes the Southern Cross of Honor as shown in Figure 2.52 The Southern Cross of Honor was created by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1898 and is the only emblem, other than an emblem of belief or an emblem signifying receipt of the Medal of Honor, that may be included on a government headstone or grave marker.

Display of Confederate Flags at National Cemeteries

Similar to NPS policy, VA policy allows for small flags of the former Confederate States of America (Confederate flags) to be placed at individual gravesites of Confederate veterans, with or without a U.S. flag, on Memorial Day and on Confederate Memorial Day in states that have designated a Confederate Memorial Day.53 In states without a Confederate Memorial Day, another date may be selected by the cemetery administrator. The VA does not provide the Confederate flags. The display is allowed only at national cemeteries where Confederate soldiers and sailors are buried. Any display of a Confederate flag must be requested by a sponsoring historical or service organization, which must provide the flags. The sponsoring organization must also place and remove the flags at no cost to the government.

The VA also permits the family members of a deceased veteran to display a Confederate flag during an interment, funeral, or memorial service at a national cemetery in accordance with federal law, which permits the display of "any religious or other symbols chosen by the family."54

In 2016, the House of Representatives agreed to an amendment to the Military Construction and Veterans Affairs and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2017, that would have prohibited the VA from implementing its policy that permitted a Confederate flag to fly from a flagpole, subordinate to the U.S. flag, at national cemeteries with Confederate veterans buried in mass graves on the same days that small graveside Confederate flags were permitted.55 The House of Representatives passed the bill as amended, but the Confederate flag provision was not included in the final omnibus appropriations legislation and did not become law.56 On August 12, 2016, the VA announced that the agency was amending its policy such that a Confederate flag may no longer fly from a fixed flagpole at any national cemetery at any time.57

Issues for Congress

The current controversy over the display of Confederate symbols on public lands and supported with federal funds affects the VA, its national cemeteries, and current law and policy regarding the provision of headstones for Confederate gravesites. The desire to remove Confederate symbols is balanced against federal policy that permits existing Confederate graves in national cemeteries to remain undisturbed and permits Confederate monuments and memorials in national cemeteries and the use of a Confederate symbol on government headstones. Legislation such as H.R. 3660, which references Confederate symbols, raises questions about how existing headstones, monuments, and memorials would be treated within the context of maintaining national cemeteries as "national shrines," as well as whether or not future headstones issued by the VA for unmarked Confederate graves should include the Southern Cross of Honor.

Department of Defense Policies and Issues

According to the Department of Defense (DOD), a servicemember's right of expression should be preserved to the maximum extent possible in accordance with the constitutional and statutory provisions of Title 10 of the U.S. Code, and consistent with good order and discipline and the national security.58 The Defense Department does not explicitly prohibit the display of the Confederate flag. However, if a commander determines that the display of the Confederate flag or Confederate symbols is detrimental to the good order and discipline of the unit, then the commander can ban such displays.

Navy Policy Statement

Currently, the Navy is the only military service that has an overall policy concerning the Confederate flag. NSTCINST 5000.1F, Naval Service Training Command Policy Statement Regarding the Confederate Battle Flag, August 29, 2017 (Enclosure 7), states the following:59

1. It is critical that all Naval Service Training Command (NSTC) Sailors, Marines, and civilians, as well as the general public, trust that NSTC is committed to providing an environment of equal opportunity (EO) and maintaining an ethnically-diverse workforce. To promote a positive EO environment, Command leaders must avoid associating the Navy with symbols that will undermine our message that NSTC is dedicated to providing an environment free of discrimination or harassment.

2. Reasonable minds differ on what the Confederate battle flag signifies. Some Americans see it as a symbol of racism and hatred, others view it as a symbol of Southern pride and heritage, while yet others consider it an outright political message. When Command leaders associate their unit with the Confederate battle flag, such as by displaying the Confederate battle flag or presenting an award that conspicuously emphasizes the Confederate battle flag, they link the Navy with the meanings that people associate with that symbol—good and bad. Command Leaders should not connect the Navy to the Confederate battle flag in a way that undermines the Navy's message of inclusiveness. However, not all displays of the Confederate battle flag will result in such inferences. A cased Confederate battle flag displayed alongside other Civil War artifacts in a Navy museum is unlikely to be viewed as a partisan statement by the Navy. Command leaders must use good sense in deciding which uses will not undermine our positive EO message.

3. While the First Amendment does not limit which messages the Navy as an organization chooses to convey, it does limit Navy regulation of individual expression rights. Therefore, Command leaders must preserve the free expression rights of NSTC Sailors, Marines, and civilians to the maximum extent possible in accordance with the Constitution and statutory provisions. That said, no Command leader should be indifferent to conduct that, if allowed to proceed unchecked, would destroy the effectiveness of a unit. Command leaders must use calm and prudent judgment when balancing these interests.

Tattoos and Body Markings

Some military recruits with Confederate flag tattoos have been barred from joining the military on the basis of policies prohibiting certain types of tattoos. The Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps all have policies that prohibit tattoos that are injurious to good order and discipline. There is no explicit prohibition against the Confederate flag and symbols in tattoos. However, the Navy does have a general policy regarding the display of the Confederate flag (see above).

Army

Army Regulation (AR) 670-1, Uniform and Insignia Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia, prohibits soldiers from having any extremist, indecent, sexist, or racist tattoos or markings anywhere on their body.60 The Army has no specific prohibitions concerning the Confederate flag or symbols.

Navy

Naval Personnel Command (NAVPERS) Instruction 15665I, General Uniform Regulations, Chapter 2, Grooming Standards, Article 2201.7 states the following:

Tattoos/body art/brands located anywhere on the body that are prejudicial to good order, discipline, and morale or are of a nature to bring discredit upon the naval service are prohibited. For example, tattoos/body art/brands that are obscene, sexually explicit, and or advocate discrimination based on sex, race, religion, ethnic, sexual orientation or national origin are prohibited. In addition, tattoos/body art/brands that symbolize affiliation with gangs, supremacist or extremist groups, or advocate illegal drug use are prohibited.61

Marine Corps

Marine Corps Bulletin 1020, Marine Corps Tattoo Policy, states, "Tattoos located anywhere on the body that are prejudicial to good order and discipline, or are of a nature to bring discredit upon the naval service, are prohibited. Examples include, but are not limited to, tattoos that are drug-related, gang-related, extremist, obscene or indecent, sexist, or racist."62 There is no specific prohibition for the Confederate flag, but some recruits with Confederate flag tattoos have reportedly been barred in the past for violating the Marine Corps' tattoo policy.63

Air Force

Air Force Instruction (AFI) 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of Air Force Personnel, Chapter 3.4.1, states, "Tattoos/brands/body markings anywhere on the body that are obscene, commonly associated with gangs, extremist, and/or supremacist organizations, or that advocate sexual, racial, ethnic, or religious discrimination are prohibited in and out of uniform."64 There is no explicit prohibition against the Confederate flag.

For more information, see CRS Report R44321, Diversity, Inclusion, and Equal Opportunity in the Armed Services: Background and Issues for Congress.

Arlington National Cemetery and Army Cemeteries

Confederate Flag Display

Arlington National Cemetery is under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Army. The Army policy states in Department of the Army (DA) Pamphlet 290–5, Administration, Operation, and Maintenance of Army Cemeteries, that on Memorial Day, or on the day when Confederate Memorial Day is observed, a small Confederate flag of a size not to exceed that of the U.S. flag may be placed on Confederate graves at private expense.65 Individuals or groups desiring to place these flags must agree in writing to absolve the federal government from any responsibility for loss or damage to the flags. Confederate flags must be removed at private expense on the first workday following Memorial Day or the day observed as Confederate Memorial Day.

Confederate Graves and Confederate Memorial

On June 6, 1900, Congress authorized $2,500 for a section of Arlington National Cemetery to be set aside for the burial of Confederate dead.66 Section 16 was reserved for Confederate graves, and among the 482 persons buried there are 46 officers, 351 enlisted men, 58 wives, 15 southern civilians, and 12 unknowns.67 To further honor the Confederate dead at Arlington, the United Daughters of the Confederacy petitioned to erect a monument that was approved by then-Secretary of War William Howard Taft on March 4, 1906, and sculpted by Moses Ezekiel (see Figure 3 and Figure 4).68 President Woodrow Wilson unveiled the memorial on June 4, 1914.

|

Figure 3. Confederate Memorial in Arlington National Cemetery |

|

|

Source: Arlington National Cemetery at http://www.arlingtoncemetery.mil/Explore/Monuments-and-Memorials/Confederate-Memorial. Note: Moses Ezekiel was a well-known sculptor and Confederate veteran who was later buried at the base of the monument. The bronze monument stands 32 feet in height and is the South represented as a woman atop a base with a frieze composed of 14 inclined shields for each Confederate state and the border state Maryland. The memorial is surrounded by Confederate graves. |

|

Figure 4. Details of the Base of the Arlington Confederate Memorial |

|

|

Source: Arlington National Cemetery at http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/csa-memorial-017-062803.jpg. Note: Included in the base are mythological figures and illustrated images of the trials and tribulations of Southerners during the war. |

Military Installations

Currently there are 10 major Army installations in southern states named after Confederate military leaders and no such installations for the other military departments. For more information on these installations and the naming policy and procedures for each military department, see CRS Insight IN10756, Confederate Names and Military Installations.

Issues for Congress

The Department of the Army has no formal administrative process for renaming military installations. Following the 2015 shooting in Charleston, SC, then-Army Chief of Public Affairs Brigadier General Malcolm Frost said, "Every Army installation is named for a soldier who holds a place in our military history. Accordingly, these historic names represent individuals, not causes or ideologies."69

Legislation has been introduced in the 115th Congress to rename the bases: H.R. 3658, Honoring Real Patriots Act of 2017, would require the Secretary of Defense to rename any military property "that is currently named after any individual who took up arms against the United States during the American Civil War or any individual or entity that supported such efforts." H.R. 3660 would also direct that the bases be renamed and would prohibit the use of federal funds for maintenance of Confederate symbols, including on military installations.

Proponents of renaming the bases contend that there are noteworthy national military leaders from other conflicts who demonstrated selfless service and sacrifice, including Medal of Honor recipients, who would be more appropriate for such an honor. Opponents of renaming these installations cite the bureaucracy of creating a new review process and the difficulty of satisfying the various viewpoints over which names (if any) would be selected as subjects of contention.

In sum, Congress faces multiple questions and proposals concerning Confederate symbols on federal lands and in federally funded programs. Legislation in the 115th Congress would address Confederate symbols in different ways. Proposals range from those concerned with individual Confederate symbols to those that would broadly affect all Confederate symbols on federal lands. In some cases, questions could arise about how the proposals would be implemented from a logistical and financial standpoint, and how they would interact with existing authorities.