The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) entered into force on January 1, 1994 (P.L. 103-182), establishing a free trade area as part of a comprehensive economic and free trade agreement among the United States, Canada, and Mexico. Although some industries may have reduced their U.S. operations, in general, NAFTA is considered to have benefitted the United States economically as well as strategically in terms of North American relations.1 The U.S. food and agricultural sectors, which is the focus of this report, has benefitting especially from NAFTA. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and many agricultural industry groups claim that NAFTA has positively affected U.S. agricultural markets. NAFTA continues to be of interest to Congress given continued strong trilateral trade and investment ties and the agreement's significance for U.S. trade policy.

President Trump has repeatedly stated that he intends to either renegotiate or withdraw from NAFTA. In May 2017, the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) notified Congress of the Administration's intent to renegotiate NAFTA.2 USTR is scheduled to conduct a public hearing in late June 2017 and also requested public comment on "matters relevant to the modernization" of NAFTA.3 In response to congressional concerns that NAFTA's renegotiation could be "unsettling" to the U.S. agricultural community, the Administration has assured Congress that it will "do no harm" to existing U.S. agricultural export markets and will prioritize U.S. agricultural exports in the renegotiation.4

It is significant that all three NAFTA countries participated in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement from which the United States withdrew in January 2017, because TPP represented the most recent attempt to design a modern regional free trade agreement (FTA).5

For more background information on NAFTA and the current status of the Administration's activities, see CRS Report R42965, The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and CRS In Focus IF10047, North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

NAFTA's Agriculture Provisions

NAFTA's primary objectives were "to eliminate barriers to trade in, and facilitate the cross-border movement of goods and services" among the NAFTA countries. NAFTA's market access provisions were structured as three separate bilateral agreements. The first agreement, the Canada-United States Trade Agreement (CUSTA), took effect on January 1, 1989, and was later subsumed into NAFTA and included certain additional provisions. The second and third agreements are both under NAFTA—one between Mexico and the United States and another between Canada and Mexico. These latter agreements took effect on January 1, 1994.

For agriculture, NAFTA (including CUSTA) eliminated tariffs and addressed other types of non-tariff barriers to trade, such as quotas, licenses, and other types of restrictions and standards. NAFTA's agricultural provisions are contained within the "Agriculture and Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures" chapter (Chapter 7), but provisions in other chapters also apply. The text box provides a summary of NAFTA's provisions that address agricultural trade.

|

Sources: CRS from NAFTA's Chapter 7 (Agriculture and Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures) and other chapters. Based also on compilations by USDA, "NAFTA," January 2008, S. Zahniser et al., NAFTA at 20: North America's Free-Trade Area and Its Impact on Agriculture, WRS-15-01, February 2015; and M. N. Gifford, "Agricultural Trade Liberalization Under NAFTA: The Negotiation Process," in R. M. A. Lyons et al. (eds.), Trade Liberalization Under NAFTA: Report Card On Agriculture, Proceedings of the 6th Agricultural and Food Policy Systems Information Workshop, January 2001. |

Tariff and Quota Elimination

For agriculture, certain restrictions on bilateral trade were eliminated immediately upon implementation, while other restrictions were phased out over either a period of 4-, 9-, or 14-years (Table 1). Sensitive products, such as sugar, were given the longest phase-out period.

Tariff elimination for agricultural products under CUSTA concluded on January 1, 1998. However, quotas for certain agricultural products in U.S.-Canada trade were not liberalized. This was carried over without change into NAFTA. In the World Trade Organization (WTO) Uruguay Round, all import quotas were converted to tariff-rate quotas (TRQs).6 Accordingly, within-quota trade occurs at the duty-free tariff treatment agreed to in CUSTA, but the over-quota trade occurs at the WTO bound tariff equivalent of the old quota, which is not liberalized. Under CUSTA, Canada excluded dairy, poultry, and eggs for tariff elimination. In return, the United States excluded dairy, sugar, cotton, tobacco, peanuts, and peanut butter. Because Canada was able to exclude dairy products, poultry, and poultry products (including eggs) from tariff elimination in NAFTA, Canada is able to maintain a supply management system for these sectors by limiting imports through restrictive TRQs.7 These products were also exempt from Canada-Mexico trade liberalization.

|

1989 |

Canada-United States Trade Agreement (CUSTA) implemented |

|

January 1994 |

NAFTA commencement |

|

|

|

|

|

January 1998 |

Completion of nine-year transition period associated with CUSTA between Canada and the United States |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

January 2003 |

Completion of nine-year transition period under NAFTA between Mexico and the United States |

|

|

|

|

|

January 2008 |

Completion of 15-year transition period under NAFTA between Mexico and the United States |

|

|

|

Sources: S. Zahniser and J. Link, Effects of North American Free Trade Agreement on Agriculture and the Rural Economy, USDA Economic Research Service, WRS-02-1, July 2002; and H. Brunke and D. A. Sumner, "Role of NAFTA in California Agriculture: A Brief Review," University of California, AIC Issues Brief# 21, February 2003.

Tariff elimination for agricultural products under NAFTA concluded on January 1, 2008. Most non-tariff trade barriers in U.S.-Mexico agricultural trade were converted to either tariffs or TRQs. Prior to NAFTA, Mexico's trade-weighted tariff on U.S. products averaged about 11%. Tariffs for some agricultural products were higher, such as Mexican tariffs for fruits and vegetables, which averaged about 20% before NAFTA.8 Also prior to NAFTA, certain agricultural products—wheat, tobacco, cheese, evaporated milk, grapes, corn, dry beans, poultry, barley/malt, animal fats, potatoes and eggs—were subject to Mexican import licensing requirements affecting a reported 25% of the value of U.S. agricultural exports.9 Mexico also applied certain "official import prices," an arbitrary customs valuation system that raised duty assessments. In the United States, import quality requirements administered by USDA10 have affected imports of some Mexican products such as tomatoes, onions, avocados, grapefruit, oranges, olives, and table grapes.

U.S. agricultural imports subject to reduced TRQ under NAFTA include sugar, beef, dairy products, peanut butter and paste, cotton, apparel, and cotton (from Canada) and beef, apparel, fabric, and yarn (from Mexico).11

SPS Measures and Other Non-Tariff Barriers

In addition to tariffs and quotas, NAFTA addressed SPS measures and other types of non-tariff barriers that may limit agricultural trade. NAFTA requires that SPS measures be scientifically based, nondiscriminatory, and transparent and minimally affect trade.

SPS measures are laws, regulations, standards, and procedures that governments employ as "necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health" from the risks associated with the spread of pests, diseases, or disease-carrying and causing organisms or from additives, toxins, or contaminants in food, beverages, or feedstuffs.12 For agricultural exporters, SPS regulations are often regarded as one of the greatest challenges in trade, often resulting in increased costs and product loss and also the potential to disrupt integrated supply chains.13 A related issue involves technical barriers to trade (TBT). TBTs cover both food and non-food traded products. TBTs in agriculture include SPS measures and other types of measures related to health and quality standards, testing, registration, certification requirements, and packaging and labeling regulations.14 For more background information, see text box.

Although NAFTA entered into force before the WTO was established and the WTO's Agreement on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures ("SPS Agreement") was implemented, it contains a detailed SPS chapter and imposes specific disciplines on the development, adoption, and enforcement of SPS measures.15 Some consider NAFTA's SPS provisions as establishing the blueprint for the SPS Agreement.16 Similar to the SPS Agreement, NAFTA's SPS disciplines are designed to prevent the use of SPS measures as disguised trade restrictions. SPS measures should also be scientifically based and consistent with international and regional standards while at the same time explicitly recognizing each country's right to determine its appropriate level of protection (e.g., to protect consumers from unsafe products or to protect domestic crops and livestock from the introduction of foreign pests and diseases).17

NAFTA also established a Committee on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures to facilitate technical cooperation in the development, application, and enforcement involving SPS measures. The committee meets periodically to review and resolve SPS issues and also hosts a number of technical working groups to enhance regulatory cooperation and facilitate trade between the NAFTA countries. Working groups address, for example, national regulatory and scientific review capacity, as well as coordination and harmonization of pesticide standards among the NAFTA partner countries.

|

NAFTA entered into force before the WTO was established and the SPS Agreement was implemented. It contains a detailed SPS chapter that some consider provided the blueprint for the SPS Agreement. SPS measures regarding food safety and related public health protection are addressed in the SPS Agreement, which established enforceable multilateral disciplines on SPS measures. The SPS Agreement entered into force in 1995 as part of the establishment of the WTO. Trade rules regarding TBTs are spelled out in the WTO's Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade, which also entered into force in 1995. In general, under the SPS Agreement, WTO members agree to apply SPS measures only to the extent necessary to protect human, animal, or plant life and health—provided they are based on scientific evidence and information. At the same time, the SPS Agreement explicitly recognizes each country's right to determine its appropriate level of protection. However, member countries are encouraged to observe established and recognized international standards, and SPS measures may not be applied in a manner that arbitrarily or unjustifiably discriminates between WTO members where identical standards prevail. For more background information on SPS measures and the SPS Agreement, see CRS Report R43450, Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) and Related Non-Tariff Barriers to Agricultural Trade. |

USTR regularly reports on a range of ongoing trade concerns in its annual National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers (NTE) report, which covers trade barriers affecting U.S. agricultural and non-food exports for the major U.S. trading partners. The most recent NTE report highlights certain outstanding issues involving SPS and U.S. trade with its NAFTA partners. Select trade disputes between the United States and its NAFTA partners are discussed later in "Addressing Outstanding Trade Disputes."

Formal Dispute Resolution Mechanism

NAFTA created both formal and informal mechanisms to resolve trade disputes among partner countries.18 NAFTA's formal mechanism for resolving disputes covers the agreement's provisions for investment (Chapter 11) and services (Chapter 14), the antidumping (AD) and countervailing duty (CVD) determinations (Chapter 19), and the general interpretation and application of the agreement (Chapter 20). NAFTA's rules-based systems for resolving disputes is meant to strengthen trade relations by providing an orderly, legal framework that defines and protects the interests of all partner countries. Table 2 highlights selected examples of dispute resolution through NAFTA, encompassing AD and CVD actions, NAFTA arbitration panels, government and industry negotiations, and technical assistance involving SPS measures.

Agricultural AD and CVD investigations and duty assessments under Chapter 19 provide a way for NAFTA countries to address trade disputes resulting from perceived unfair trade practices. It allows exporters and domestic producers a way to make their case and appeal the results of trade-remedy investigations before an independent and objective binational panel, and it provides an alternative option to judicial review of such decisions before domestic courts. AD duties may be imposed if imports are being sold at less than fair value and causing or threatening to cause injury to a domestic industry. CVD duties may be imposed on imported goods to offset subsidies provided to producers or exporters by the government of the exporting country, and they must also meet an injury test. Under NAFTA, each country may apply its own AD and CVD laws but must publish a notice of national investigations and inform others on how to provide input.19

|

National countervailing duty (CVD) or antidumping (AD) actions |

|

|

NAFTA arbitration panels |

|

|

Government negotiations (including internal working groups involving multiple federal agencies) |

|

|

Industry Negotiations |

U.S. and Mexican grape industries resolved dispute over Mexican labeling regulations. Mexican and U.S. cattle industry negotiations prevented Mexican AD duties. An Advisory Committee on Private Commercial Disputes Regarding Agricultural Goods is established. |

|

Technical Assistance |

NAFTA Sanitary and Phytosanitary Committee facilitates regional technical cooperation. The United States and Mexico established bilateral Plant Health Working Group and Karnal Bunt Team. The two countries are also cooperating in the development of a Mexican national grading and standards system for perishable commodities. |

Source: S. Zahniser and J. Link, Effects of North American Free Trade Agreement on Agriculture and the Rural Economy, USDA Economic Research Service, WRS-02-1, July 2002.

Note: For a listing of decisions and reports, see NAFTA Secretariat, https://www.nafta-sec-alena.org/Home/Dispute-Settlement/Decisions-and-Reports.

Additional general dispute settlement is provided under NAFTA's Chapter 20. The NAFTA secretariat is responsible for the administration of the dispute settlement process under both Chapters 19 and 20. Previous disputes and decisions involving the NAFTA secretariat cover refined sugar, sugar beets, and HFCS;20 softwood lumber;21 wheat;22 apples; and beef, pork, and poultry products; among other products.23 Other types of disputes involving U.S. agricultural markets and Canada or Mexico have included trade concerns involving milk products,24 country-of-origin labeling (COOL) of meat products,25 and potatoes. Some of these trade disputes have been formerly addressed within the framework of the WTO outside NAFTA.

Agricultural Trade Trends with NAFTA Partners

Canada and Mexico are key U.S. agricultural trading partners. Since NAFTA was implemented, the value of U.S. agricultural trade with Canada and Mexico has increased sharply and now accounts for a large overall share of all U.S. agricultural exports and imports.

Agricultural products presented here cover commodities as defined by USDA for the purposes of calculating U.S. agricultural exports, imports, and the agricultural trade balance. This definition includes raw and bulk agricultural commodities, nursery products, wine, and cotton fiber products. This definition excludes fish and seafood, distilled spirits and other beverages, and manufactured tobacco products (see text box).

Total Agricultural Trade

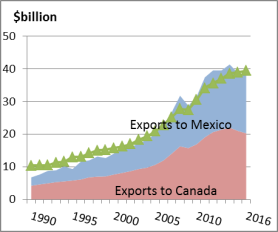

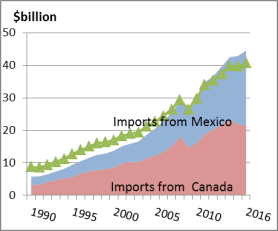

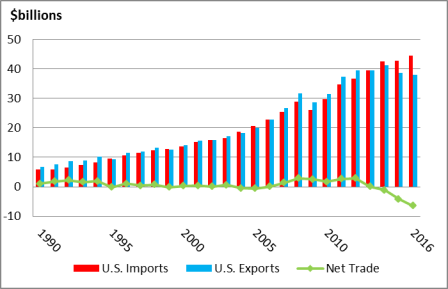

Over the past 25 years since NAFTA was implemented, the value of U.S. agricultural trade with Canada and Mexico has increased dramatically. Exports rose from $8.7 billion in 1992 to $38.1 billion in 2016, while imports rose from $6.5 billion to $44.5 billion over the same period (Table 3). This resulted in a $6.4 billion trade deficit for agricultural products in 2016, despite trends in previous years when there was a trade surplus (Figure 1). For example, from 2007 to 2011, U.S. agricultural trade to its NAFTA partners consistently showed a trade surplus, averaging $2.4 billion per year. This compares to the past five years (2012-2016), when the U.S. trade deficit averaged $1.8 billion per year. In general, trade balances tend to be variable year-to-year depending on market and production conditions, commodity prices and currency exchange rates, and consumer demand, among many other factors.

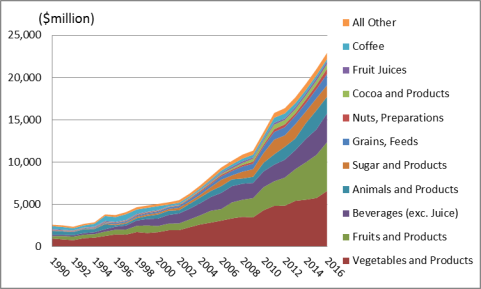

Adjusted for inflation, growth in the value of total U.S. agricultural exports and imports with its NAFTA partners have increased roughly threefold, growing at an average rate of about 5-6% annually26 (Figure 2, Figure 3).

|

USDA's definition of "agricultural products" (often referred to as "food and fiber" products)—for the purposes of calculating U.S. agricultural exports, imports, and the agricultural trade balance—covers a broad range of goods from unprocessed bulk commodities such as soybeans, feed corn, wheat, rice, and raw cotton to highly processed, high-value foods and beverages such as sausages, bakery goods, ice cream, beer and wine, and condiments sold in retail stores and restaurants. All of the products found in Chapters 1-24 of the U.S. Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) are considered agricultural products. Exceptions include fishery products (Chapters 3 and 16), manufactured tobacco products such as cigarettes and cigars (Chapter 24), and distilled spirits (Chapter 22). Agricultural products within these chapters generally fall into the following categories: grains, animal feeds, and grain products (such as bread and pasta); oilseeds and oilseed products (such as soybean oil and olive oil); livestock, poultry, and dairy products including live animals, meats, eggs, and feathers; horticultural products including all fresh and processed fruits, vegetables, tree nuts, as well as nursery products, and beer and wine; unmanufactured tobacco; and tropical products such as sugar, cocoa, and coffee. ("Animals and Products" generally include live animals, red meat, poultry, and dairy products, fats and oils, hides and skins, wool and mohair, and other miscellaneous products.) Products outside of Chapters 1-24 are also considered agricultural products. These include essential oils (Chapter 33), raw rubber (Chapter 40), raw animal hides and skins (Chapter 41), and wool and cotton (Chapters 51-52). Some products derived from plants or animals that are not considered "agricultural" because of their manufactured nature are cotton thread and yarn; fabric, textiles, and clothing; leather and leather articles of apparel; cigarettes and cigars; and distilled spirits. USDA's trade databases also include selected "non-agricultural" commodities. These include manufactured products derived from plants or animals (such as yarns, fabrics, textiles, leather, articles of apparel, cigarettes and cigars, and spirits) or products used in the farm production process (such as agricultural chemicals, fertilizers, and farm machinery). Other "non-agricultural" commodities in USDA's trade databases are fishery and seafood products given their food value (as USDA collaborates with the seafood industry to promote exports) and solid wood products (as USDA also collaborates with U.S. industry to promote exports of these products). Source: USDA, "GATS Agricultural Products Definition," https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/AgriculturalProducts.aspx. |

|

|

Source: CRS from USDA, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/ExpressQuery1.aspx. Data are not adjusted for inflation. Note: Agricultural products presented here cover commodities as defined by USDA. |

NAFTA countries are key U.S. agricultural trading partners. As a share of U.S. trade, Canada and Mexico are ranked second and third (after China) as leading export markets for U.S. agricultural products. In 2016, Canada and Mexico accounted for 28% the total value of U.S. agricultural exports and 39% of its imports. This compares to 1992 (pre-NAFTA), when Canada and Mexico accounted for 20% and 26% of U.S. agricultural export and import values, respectively. In 2016, leading traded agricultural products under NAFTA were meat and dairy products; grains and feed; fruits, tree nuts, and vegetables; oilseeds; and sugar and related products.

|

Year |

Total Ag Exports |

Total Ag Imports |

Ag Exports to Canada |

Ag Imports from Canada |

Ag Exports to Mexico |

Ag Imports from Mexico |

NAFTA Ag Exports |

NAFTA Ag Imports |

Net Trade |

|

($billions) |

|||||||||

|

1990 |

39.5 |

22.9 |

4.2 |

3.2 |

2.6 |

2.6 |

6.8 |

5.8 |

1.0 |

|

1991 |

39.4 |

22.9 |

4.6 |

3.3 |

3.0 |

2.5 |

7.6 |

5.9 |

1.8 |

|

1992 |

43.2 |

24.8 |

4.9 |

4.1 |

3.8 |

2.4 |

8.7 |

6.5 |

2.2 |

|

1993 |

43.0 |

25.1 |

5.3 |

4.7 |

3.6 |

2.7 |

8.9 |

7.4 |

1.6 |

|

1994 |

46.2 |

27.0 |

5.6 |

5.3 |

4.6 |

2.9 |

10.1 |

8.2 |

1.9 |

|

1995 |

56.2 |

30.3 |

5.8 |

5.6 |

3.5 |

3.8 |

9.3 |

9.5 |

-0.1 |

|

1996 |

60.4 |

33.5 |

6.1 |

6.8 |

5.4 |

3.8 |

11.6 |

10.6 |

1.0 |

|

1997 |

57.1 |

36.1 |

6.8 |

7.4 |

5.2 |

4.1 |

12.0 |

11.6 |

0.4 |

|

1998 |

51.8 |

36.9 |

7.0 |

7.8 |

6.2 |

4.7 |

13.1 |

12.5 |

0.7 |

|

1999 |

48.4 |

37.7 |

7.1 |

8.0 |

5.6 |

4.9 |

12.7 |

12.9 |

-0.2 |

|

2000 |

51.3 |

39.0 |

7.6 |

8.7 |

6.4 |

5.1 |

14.1 |

13.7 |

0.3 |

|

2001 |

53.7 |

39.4 |

8.1 |

9.9 |

7.4 |

5.3 |

15.5 |

15.1 |

0.4 |

|

2002 |

53.1 |

41.9 |

8.7 |

10.3 |

7.2 |

5.5 |

15.9 |

15.9 |

0.0 |

|

2003 |

59.4 |

47.4 |

9.3 |

10.3 |

7.9 |

6.3 |

17.2 |

16.6 |

0.6 |

|

2004 |

61.4 |

54.0 |

9.7 |

11.5 |

8.5 |

7.3 |

18.2 |

18.7 |

-0.5 |

|

2005 |

63.2 |

59.3 |

10.6 |

12.3 |

9.4 |

8.3 |

20.0 |

20.6 |

-0.6 |

|

2006 |

71.0 |

65.3 |

12.0 |

13.4 |

10.9 |

9.4 |

22.8 |

22.8 |

0.0 |

|

2007 |

90.0 |

71.9 |

14.1 |

15.2 |

12.7 |

10.2 |

26.8 |

25.4 |

1.3 |

|

2008 |

114.8 |

80.5 |

16.3 |

18.0 |

15.5 |

10.9 |

31.8 |

28.9 |

2.8 |

|

2009 |

98.5 |

71.7 |

15.7 |

14.7 |

12.9 |

11.4 |

28.7 |

26.1 |

2.6 |

|

2010 |

115.8 |

81.9 |

16.9 |

16.2 |

14.6 |

13.6 |

31.5 |

29.8 |

1.7 |

|

2011 |

136.4 |

99.0 |

19.0 |

18.9 |

18.4 |

15.8 |

37.4 |

34.8 |

2.6 |

|

2012 |

141.6 |

102.9 |

20.6 |

20.2 |

18.9 |

16.4 |

39.5 |

36.6 |

2.9 |

|

2013 |

144.4 |

104.2 |

21.4 |

21.8 |

18.1 |

17.7 |

39.5 |

39.4 |

0.0 |

|

2014 |

150.0 |

111.8 |

22.0 |

23.2 |

19.4 |

19.3 |

41.3 |

42.5 |

-1.1 |

|

2015 |

133.1 |

113.6 |

21.0 |

21.8 |

17.7 |

21.0 |

38.7 |

42.9 |

-4.2 |

|

2016 |

134.9 |

114.6 |

20.2 |

21.6 |

17.8 |

23.0 |

38.1 |

44.5 |

-6.4 |

Source: CRS from USDA, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/ExpressQuery1.aspx. Data are not adjusted for inflation.

Note: Agricultural products presented here cover commodities as defined by USDA.

|

|

|

Reports by USDA further highlight how U.S. agricultural exports to its NAFTA partners have increased as a share of the total value of U.S. trade, often triggering shifts in trade with other U.S. trading partners. As part of its 20-year retrospective analysis of the impacts of NAFTA on the U.S. agricultural sectors,27 USDA reports that U.S. agricultural exports to NAFTA countries comprised 20% of the total value of total agricultural exports in 1991-1993, rising to 28% in 2010-2012. Exports to China and Hong Kong rose even more sharply, from 3% to 18% over the same period. In contrast, U.S. agricultural exports to other U.S. FTA partners rose slightly, and exports to the rest of the world dropped from about 77% to 54% of the value of U.S. exports. USDA's analysis also indicates that U.S. agricultural imports are now also more widely supplied by its NAFTA partners: Canada and Mexico comprised 27% of the total value of U.S. agricultural imports in 1991-1993, rising to 36% in 2010-2012. According to USDA, the value of agricultural imports from China and Hong Kong rose slightly, from 2% to 4% of total value, while agricultural imports from other U.S. FTA partners and the rest of the world dropped from about 70% to 60%.

Agricultural Trade with Canada

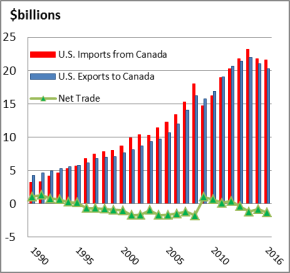

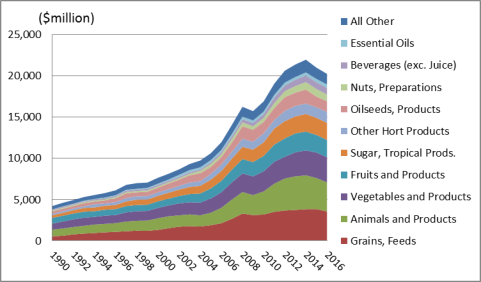

In 2016, U.S. agricultural exports to Canada were valued at $20.2 billion (Figure 4). Fish and seafood exports—while not included in the total for agricultural products—amounted to another $1.1 billion. Leading U.S. agricultural exports to Canada were (ranked in descending order based on value) grains and feed; animal products; fruits, vegetables, and related products; sugar/tropical products; other horticultural products; oilseeds; nuts; beverages (excluding fruit juice); and essential oils.28

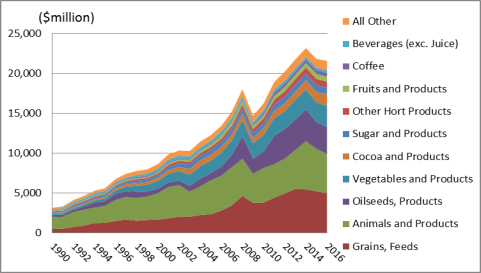

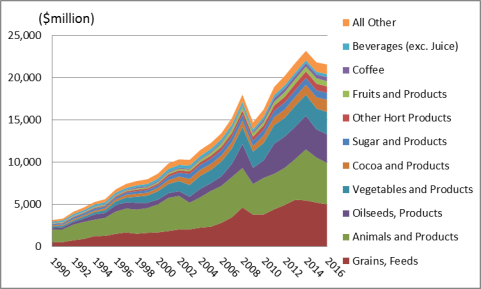

In 2016, U.S. agricultural imports from Canada were valued at $21.6 billion (Figure 5). Fish and seafood imports totaled another $3.2 billion. Leading U.S. agricultural imports from Canada were grains and feed; animal products; oilseeds; cocoa/sugar and related products; fruits, vegetables, and related products; other horticultural products; coffee; and beverages.

Since NAFTA was implemented, the balance of agricultural trade between the United States and Canada has alternated between a trade surplus and a trade deficit (Figure 6). Over the past five years (2012-2016), the U.S. trade deficit with Canada has averaged about $0.7 billion per year.

|

|

Source: CRS from USDA, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/ExpressQuery1.aspx. Data are not adjusted for inflation. Note: Agricultural products presented here cover commodities as defined by USDA. |

|

|

Source: CRS from USDA, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/ExpressQuery1.aspx. Data are not adjusted for inflation. Note: Agricultural products presented here cover commodities as defined by USDA. |

|

|

|

Agricultural Trade with Mexico

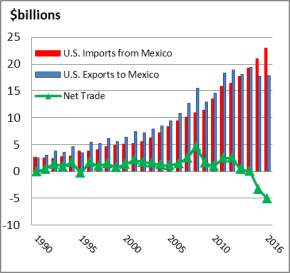

In 2016, U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico were valued at $17.8 billion (Figure 8). Fish and seafood exports were negligible (less than $100 million). Leading U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico were (ranked in descending order based on value): animal products; grains and feed; oilseeds; sugar/tropical products; other horticultural products; fruits, nuts, and vegetables, and related products; cotton; seeds and nursery products.

In 2016, U.S. agricultural imports from Mexico were valued at $23.0 billion (Figure 9). Fish and seafood imports totaled another $0.6 billion. Leading U.S. agricultural imports from Mexico were fruits, vegetables, and related products; beverages; animal products; sugar/products; grains and feeds; nuts; cocoa/products; fruit juices; and coffee.

The balance of agricultural trade between the United States and Mexico has alternated between a trade surplus and a trade deficit since NAFTA was implemented (Figure 7). Over the past five years (2012-2016), taking into account alternating periods of trade surplus and deficit, the U.S. agricultural trade deficit with Mexico averaged $1.1 billion per year. The deficit has grown more sharply in recent years as overall U.S. agricultural imports from Mexico have continued to grow while U.S. exports to Mexico have receded. Prior to 2015, U.S.-Mexico agricultural trade consistently showed a U.S. trade surplus.

|

|

Source: CRS from USDA, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/ExpressQuery1.aspx. Data are not adjusted for inflation. Note: Agricultural products presented here cover commodities as defined by USDA. |

|

|

Source: CRS from USDA, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/ExpressQuery1.aspx. Data are not adjusted for inflation. Note: Agricultural products presented here cover commodities as defined by USDA. |

Selected State-Level Trade

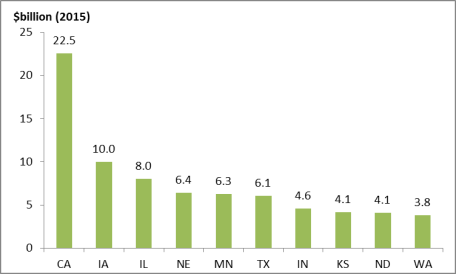

Leading agricultural exporting states are California, Iowa, Illinois, Nebraska, Minnesota, Texas, Indiana, Kansas, North Dakota, and Washington (Figure 10). USDA-reported export data by state are not available by country of destination and date back to 2000 only.29 Therefore, available state data from USDA are not entirely suitable for showing trends under NAFTA at the state level.

|

|

Source: USDA, "State Export Data," https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/state-export-data/. Note: State-level trade data are limited, and trends under NAFTA or agricultural trade among the NAFTA countries by state are not available. |

Limited additional trade data are reported by some states. For example, the state of California compiles and reports official annual agricultural export data.30 These data are derived from port of export district data reported in the official U.S. trade data, published industry sources, and unpublished government and industry information. Comparable official state data are not available to examine U.S. or state-level agricultural imports.31 For California, available state-reported export data indicate that the state's agricultural exports have grown substantially over the past decade, totaling more than $20.7 billion in 2015—a more than threefold increase compared to the 1990s. Of total agricultural exports, NAFTA countries comprised the largest market for California's farm exports, accounting for 22% of California's agricultural exports. Leading exports to Canada were wine, lettuce, strawberries, table grapes, processed tomatoes, almonds, oranges, raspberries and blackberries, carrots, walnuts, peaches and nectarines, cauliflower, broccoli, spinach, pistachios, and dairy products. Leading exports to Mexico were dairy products, table grapes, processed tomatoes, almonds, peaches and nectarines, flowers and nursery plants, walnuts, pistachios, strawberries, rice, cotton, raisins, plums, oranges, lettuce, and kiwi fruit. Agricultural exports from California to Canada and Mexico comprise roughly 10% of total U.S. agricultural exports to NAFTA partners.

Similar trade data are not readily available for other states. However, industry reports indicate that both Mexico and Canada are leading markets for Iowa's pork products32 and also grain products from some Northern Plains states.33

State-level data are not available to assess the estimated economic effects of NAFTA on key agricultural producing and exporting states. Studies exist for a few states, such as California,34 but much of this research is dated and is not comprehensive.

Estimating NAFTA Effects

Estimating the economic impact of NAFTA to the U.S. agriculture industry is not straightforward. It is difficult to isolate changes in U.S. agricultural trade and markets attributable to NAFTA's implementation from other factors that may have influenced trade over this period. Such non-NAFTA influences include changes in agricultural policies, advances in technology (including the Internet), and growing integration of the global economy.35 U.S. tariffs and trade protections for food and agricultural products were already minimal before NAFTA was implemented.36 Trade liberalization and expansion and increased foreign direct investment in the food and agricultural sectors had begun before NAFTA was implemented.37 In addition, available data are often incomplete and of limited use in generating accurate results from economic models. Such estimates may also provide an incomplete accounting of the total economic effects of trade agreements.38

Among the types of generally acknowledged benefits from trade are greater market access and a reduction in barriers to economic activities (e.g., tariff and other non-tariff trade barriers); lower consumer prices, more product variety, and year-round access for certain products. Higher product sales through exports contribute to economic growth, as do higher incomes in trading partner countries, which contribute to increased demand for higher-value agricultural products.39 Others point to the benefits of regional trade agreements, including market integration, competitive or complementary economic linkages, and geographical proximity.40

In general, NAFTA is considered to have benefitted U.S. agriculture. Some credit NAFTA with further facilitating trade by formalizing these changes and providing a more stable trade environment among the NAFTA partner countries. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce states: "NAFTA has been a bonanza for U.S. farmers and ranchers, helping U.S. agricultural exports to Canada and Mexico to increase by 350%," despite growth over the period in Mexico's agricultural production.41 USTR also claims that NAFTA has benefitted American farmers.42

Many U.S. food and agricultural industry groups claim that NAFTA has positively affected their markets.43 According to an industry coalition group, "NAFTA has been a windfall for U.S. farmers, ranchers and food processors."44 Since the agreement was implemented, trilateral agricultural trade among the member countries has risen sharply. Additionally, trade with Canada and Mexico comprise an ever-larger share of U.S. agricultural markets. Many attribute generally lower U.S. consumer prices and improved consumer choices and variety (e.g., imports of off-season produce and greater variety of food products) to NAFTA's elimination of tariffs and quota restrictions under the agreement. Others note that as Mexico's consumer incomes improve, U.S. agricultural exporters could benefit from increased market demand for some food products.45

Some claim that NAFTA has resulted in both benefits and losses, and that positive and negative impacts attributed to the agreement have been overstated or mixed.46 Economic impacts under NAFTA depend on what is produced and where it is produced. This is also true regarding the agreement's effects on employment and wages, as some workers and industries have faced disruptions due to loss of market share from increased competition, while others have gained from the new market opportunities that were created.47 Yet others claim that NAFTA has further contributed to consolidation in North America's agriculture, resulting in fewer small farms, particularly in Mexico.48

In the end, the extent to which NAFTA has benefitted the U.S. economy is not clear cut, since the gains could be partly attributable to Mexico's unilateral liberalization (which was happening at the same time as NAFTA) or to gains attributable to the U.S.-Canada FTA (CUSTA, which was already in effect before NAFTA was negotiated). Other factors have influenced regional agricultural trade, including changes in Mexico's agricultural policies and workforce, advances in technology (e.g., e-commerce, greenhouse production), disruption due to the peso devaluation in the 1990s and the economic downturns in 2001 and 2009, and competing buyers and sellers of agricultural commodities in countries outside of NAFTA. Other market developments that may have influenced North American trade since NAFTA's implementation include alternative product uses (e.g., corn used in ethanol production and corn byproducts, such as dried distiller grains) and other market substitution effects, changes in crop mix, mechanization, increases in labor efficiencies, and growing integration of the global economy.49

Improved Market Integration

As part of its 20-year retrospective analysis of the impacts of NAFTA on the U.S. agricultural sectors, USDA concluded that "NAFTA has had a profound effect on many aspects of North American agriculture over the past two decades," contributing to increased market integration and cross-border investment and other "important changes in consumption and production."50 USDA's assessment is based on cross-border economic activity (primarily agricultural trade and intraregional foreign direct investment [FDI]51) as well as tariffs, quotas, and other barriers to trade and investment.

According to USDA

NAFTA has had a substantial impact on the integration of North America's agricultural markets.... Integration is visible in increased cross-border flows of goods, services, capital, and labor. Trade in goods consists of not only final consumer products but also intermediate inputs and raw materials, as firms reorganize their activities around regional markets for both inputs and outputs, spurred in part by greater foreign direct investment (FDI). In addition, decision-makers in both the government and the private sector continue to pursue a course of greater institutional and policy cooperation and coordination to encourage further market integration.

Most agricultural sectors within NAFTA are associated with a high degree of market integration.52 A few sectors are associated with medium integration, including U.S. and Canada wheat markets and also markets adversely affected by the retaliatory tariffs applied by Mexico in conjunction with the U.S.-Mexico trucking dispute.53 Market integration is low in sectors that were exempted from NAFTA, such as between the U.S. and Canadian dairy, poultry, and egg product sectors. USDA's analysis provides additional examples of how NAFTA has advanced the integration of North America regional agriculture, broken down by selected commodity groupings—grains and oilseeds; livestock and animal products; fruits and vegetables; sugar and sweeteners; cotton, textiles, and apparel; and processed foods. And despite improved market integration, USDA's analysis indicates that prices are still not fully integrated in North American agriculture.54

USDA's analysis concludes that NAFTA has resulted in substantial levels of foreign investment in the processed food sectors but that NAFTA has only a small, positive net effect on U.S. agricultural employment. Regionalization of SPS standards—referring to increased vigilance to assess and eradicate plant and animal pests and diseases—is also attributed with facilitating trade in North American meat and produce markets.55

Participants at a 2001 workshop agreed that "Mexico and Canada had clearly benefited from NAFTA, that processors of higher valued products in all three countries were the greatest beneficiaries, and that small Mexican producers were the biggest losers."56 The greatest beneficiaries were said to be producers of feed grain and oilseeds and processors of high-value products, such as processed foods, produce, and horticultural products.

Increased Foreign Direct Investment

According to USDA, Mexico is the third-largest host country for U.S. direct investment in the global food and beverage industries and has also attracted FDI in production agriculture—much of it since NAFTA was implemented.57 Some, however, claim that Mexican restrictions on corporate farming, acreage limits, and land investment restrictions in coastal and border areas have been a constraint to U.S. investment in some sectors.58

The most recent available Commerce Department data indicate that U.S. direct investment in Mexico on a historical-cost basis (i.e., the stock of direct investment) was about $3.6 billion in the food industry in 2011, $4.2 billion in the beverage industry in 2010, and $375 million in crop and animal production combined in 2007. Since NAFTA, the U.S. direct investment position in the Mexican food and beverage industries has expanded greatly, "rising from a total for the two industries of about $2.3 billion in 1993 to about $8.7 billion in 2007, before declining to about $7.5 billion in 2010."59 Most U.S. investment has been in the beverage industry.

Canada is also a major recipient of U.S. direct investment. In 2010, according to USDA, U.S. direct investment in Canada's food and beverage industries was $5.9 billion and $7.8 billion, respectively.60 USDA's retrospective analysis further highlights that NAFTA has resulted in substantial levels of foreign investment in the processed food sectors.61

U.S.-Mexico Competitive Conditions

Researchers at the University of California (UC) highlight some of the common myths about the competitive farm conditions between the United States and Mexico based on an example involving fruit and vegetable production.62 Contrary to popular belief, Mexico does not necessarily have an advantage in agricultural production because of relatively lower wage rates and worker benefits for labor-intensive agricultural products (such as fruits and vegetables), labor abundance, or lower environmental and food safety standards. In reality, fruit and vegetable production places demands on capital, technology, management, research, marketing, and infrastructure. Mexico's principal advantage is seasonal (climatic advantage) rather than a cost advantage. Mexican farm labor is generally less well-trained and less efficient, offsetting some of its wage rate advantage. Some Mexican growing areas also experience labor shortages. In addition, Mexican growers often provide social services for workers, such as housing and schools, which raises production costs. Most Mexican producers who grow for export markets must also meet necessary product quality and safety standards and be third-party certified. Mexico also has a disadvantage in marketing and in the buyers' perception of its products, as well as in research and development (R&D) and infrastructure, compared to the United States.

These same UC researchers further highlight some the competitive advantages of agricultural production in United States compared to Mexico.63 For example, the U.S. agricultural sectors continue to benefit from R&D from federal institutions—such as USDA and the land grant university system—and public sector investments in transportation and infrastructure of many types, including water storage and distribution. U.S. producers also benefit from extensive private sector research targeting specific crop needs, transparent and relatively responsive government support, and direct access to the U.S. domestic markets—still the world's largest consumer market.

One of the more controversial aspects of NAFTA has been its effect on the agricultural sector in Mexico and the perception that the agreement has caused a higher amount of worker displacement in the agricultural sector than in other sectors of the economy. Some claim that Mexico has been impacted by transitory poverty created by economic adjustments and also social exclusion to the benefits of globalization.64 Although Mexico's farm exports rose sharply, rural poverty levels in Mexico remain the same as before the agreement, and the expected wage and income convergence between Mexico and the United States did not happen.65 Some have called for reform of NAFTA to address these and other perceived concerns in Mexico's farming community.66 Others dispute the role of trade in Mexico's rural poverty.67 While NAFTA likely contributed to changes to Mexico's agricultural sector, given increasing import competition from the United States, some changes are likely also attributable to Mexico's policy reforms to its agricultural sectors.68

Industry Reaction to Potential NAFTA Changes

Many stakeholders in U.S. agricultural sectors have expressed opposition to the Trump Administration's decision to withdraw from TPP and threats to withdraw from NAFTA, citing benefits to the food and agricultural industries from trade and potential for disruptions in U.S. export markets given growing uncertainty in U.S. trade policy. However, some in Congress and within U.S. agriculture are cautiously supporting efforts to renegotiate or "modernize" some of NAFTA's provisions as they pertain to agriculture. Some recommend that many of the agricultural provisions agreed to in the TPP agreement could provide a possible model framework for a NAFTA renegotiation.

Reaction to Threats of NAFTA Withdrawal

In late April 2017, President Trump announced he was considering an executive order to set in motion the U.S. withdrawal from NAFTA.69 The response from the U.S. agriculture community was swift, with many U.S. agricultural groups expressing strong opposition to outright NAFTA withdrawal. Ultimately, President Trump decided not to withdraw from NAFTA at this time. This and other recent actions by the Administration have raised concerns in the U.S. agricultural community over the uncertainty of U.S. trade policy and the potential for disruptions in U.S. export markets.70

Media reports following the Administration's announcement highlight opposition to outright withdrawal from many in Congress.71 Some in Congress opposed the nomination of Robert Lighthizer for USTR, given concerns about the Administration's intentions regarding U.S. trade policy, including NAFTA.72 Several Members of Congress claim that NAFTA has had positive impacts on their states' agricultural sectors.73

Reactions from a number of U.S. agricultural leaders were starker. According to the National Pork Producers Council, NAFTA withdrawal could be "cataclysmic"74 and "financially devastating" to U.S. pork producers.75 The National Corn Growers Association said that "withdrawing from NAFTA would be disastrous for American agriculture" and disrupt trade with the sector's top trading partners. The American Soybean Association said withdrawing from NAFTA is a "terrible idea" and would hamper ongoing recovery in the sector.76 The U.S. Grains Council highlighted that withdrawal would have an "immediate effect on sales to Mexico."77 The National Association of Wheat Growers stated that Mexico is the "largest U.S. wheat buyer," accounting for more than 10% of wheat exports annually.78 Fruit and vegetable growers also did not support NAFTA withdrawal, citing the benefit of exports to Mexico.79

Many U.S. agricultural trade associations continue to express strong support for NAFTA. Following the threat of withdrawal and fear that Mexican buyers could seek alternative markets, the U.S. corn, soybean, dairy, pork, beef, and rice industries sent high-ranking representatives to Mexico to reassure buyers that the U.S. will remain a stable and reliable export market.80 The state of Nebraska also hosted a delegation of Mexican grain and food industry officials to shore up against possible threats to the U.S.-Mexico trading relationship.81 Various reports indicate that Mexico is looking to find alternative suppliers for some imported products, such as rice (which could be supplied by Vietnam and Thailand), corn and soybeans (Argentina and Brazil),82 and dairy products (New Zealand and Europe).83 Media reports also indicate that Mexico is not worried about finding alternative consumer markets for some of its exported products, such as avocados, which are now mostly sold to the United States.

Reaction to Calls to "Modernize" NAFTA

On May 23, 2017, USTR formally notified Congress of the Administration's intent to renegotiate NAFTA.84 Despite strong opposition to NAFTA withdrawal by many in Congress and much of the agricultural industry, some Members of Congress and farm interest groups are supporting NAFTA renegotiation.85 Many in Congress want the Trump Administration to pressure Canada to change its dairy pricing policies, which they contend discriminate against the United States, and to address this issue as part of a NAFTA renegotiation.86 House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Kevin Brady stated that "NAFTA contains many good provisions, but portions of it should be updated and improved."87 Others see renegotiation as an opportunity to address concerns regarding certain outstanding trade disputes. The state of Washington reportedly sees NAFTA renegotiation as an opportunity to address ongoing concerns regarding potatoes, milk, cheese, and wine.88 Others support NAFTA renegotiation if it "does no harm" to existing U.S. export markets.89 In response to congressional concerns that NAFTA's renegotiation could be "unsettling" to the U.S. agricultural community, the Administration has assured Congress that it will protect U.S. agricultural export advantages gained under NAFTA.90 Major food companies have also warned against drastic NAFTA changes and worry about unforeseen consequences of opening up the trade deal.91

An industry coalition of 130 agricultural groups and food companies support the Administration's efforts to modernize NAFTA "in ways that preserve and expand upon the gains achieved."92 The American Farm Bureau Federation claims that there are "compelling reasons to update and reform NAFTA from agriculture's perspective, including improvements to biotechnology, sanitary and phytosanitary measures, and geographic indicators."93 Others support proposals to "update and modernize" NAFTA.94

In addition to addressing Canada's dairy support and pricing policies, the dairy industry claims that "improvements are needed" to address SPS commitments and geographical indications (GIs).95 Potato growers support renegotiation to address outstanding concerns in U.S.-Mexico potato trade involving SPS measures, which they recommend be addressed similarly to how SPS was addressed in the TPP agreement.96 Others call for reforms of Canada's grain grading standards.97 Among groups that rely in part on agricultural product inputs, the U.S. textile, apparel, and footwear industry has also expressed strong support for NAFTA and urges that any renegotiation "do no harm" to the "successful supply chains" the industry now relies on.98

U.S. meat and livestock interests are divided over whether NAFTA renegotiation should bring country-of-origin labeling (COOL) for meat and pork products back into law: The National Cattlemen's Beef Association does not want to revive mandatory labeling,99 while the National Farmers Union sees an opportunity to do so.100

Many farm interest groups cite commitments agreed to under the TPP agreement as possible approaches in renegotiating NAFTA.101 Similarly, others cite provisions regarding agriculture discussed during the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP) negotiation with the European Union (EU) over the past few years.102 Some Canadian officials are recommending that provisions in the trade negotiations between the EU and Canada in the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) be used as a blueprint for NAFTA.103 The Mexican government is in the process of setting its priorities, which include improving competitiveness in the NAFTA region.104 Other Mexican officials have indicated that although parts of NAFTA may need to be modernized, the agricultural provisions do not.105 Reportedly, a Mexican industry delegation urged the Trump Administration not to take Mexico for granted as a market for U.S. agricultural products.106

However, many in Congress and the U.S. agricultural sectors have expressed the need for caution when renegotiating NAFTA.107 In general, most agricultural groups worry about destabilizing current markets and the potential unpredictability of future talks.108 They also point out that there could be "enormous risks" to existing U.S. export markets if the negotiations were to fail.109 The National Association of State Departments of Agriculture supports "prudent" renegotiation that does not do away with the "significant gains and advantages" under NAFTA.110 Others wonder whether NAFTA renegotiation could backfire, leading to tougher requirements, such as rules of origin for goods made in North America111 or additional tariffs or quotas on imports to protect the viability of Canadian and Mexican domestic producers.112 The chief agriculture negotiator for USTR during the Obama Administration has cautioned the Trump Administration to take a more measured approach to any future NAFTA talks and warned that a failure to do so could backfire against the U.S. agriculture industry, it being an easy target for retaliation.113 Others note that renegotiation may be complicated by the complex nature of agricultural issues.114

Finally, a coalition of sugar exporting countries (except for Mexico) is urging the Administration to take action in its renegotiations to address concerns about Mexico's sugar shipments to the United States.115 Some in Congress, however, argue that the high-profile U.S.-Mexico sugar case is not about market access but shipments of subsidized, dumped Mexican sugar.116 On June 6, 2017, the United States and Mexico agreed in principle to amendments in the case,117 which could remove this contentious issue from any upcoming NAFTA talks.

Reaction to Decision to Withdraw from TPP

In January 2017, the Trump Administration formally withdrew the United States from the TPP agreement.118 All three NAFTA countries are signatories to TPP. Prior to withdrawal, a broad cross-section of agricultural groups and food and agribusiness interests had expressed support for implementing TPP, citing increased market access for U.S. farm and food products under the agreement and potential for expanded exports. As such, some in the U.S. agricultural sector have expressed disappointment at the decision to withdraw from TPP, citing, for example, the possibility under the agreement for California agriculture to reach key markets in the Pacific Rim.119 In Congress, some Members have expressed the desire to rejoin TPP.120

However, support for TPP within agriculture, while broad-based, was not universal. A number of groups representing agriculture and food industry interests opposed TPP, reflecting concerns about competition from imports, the lack of a strong enforcement mechanism against currency manipulation, and the potential offshoring of jobs in the food processing sector.

The TPP agreement sought to liberalize agricultural trade through lower tariffs, expanded TRQs, and agreements over rules and procedures for reducing non-tariff barriers. As negotiated, TPP would have materially increased the overseas markets to which U.S. farm and food products would have preferential access. A 2016 ITC report concluded that TPP would provide significant benefits for U.S. agriculture.121

Regarding renegotiation of some of NAFTA's agricultural provisions, some stakeholders have recommended that many of the agricultural provisions agreed to in the TPP agreement could provide a possible framework for any future NAFTA renegotiation. Many U.S. trade groups also recommend that negotiators consider many of the types of agricultural commitments agreed to in the TPP agreement, which are viewed to have broadly improved upon existing agricultural provisions in U.S. FTAs. These changes address SPS and other non-tariff barriers to trade, among other issues.122 How some provisions in the TPP agreement could provide a general framework to renegotiate certain agricultural provisions is further discussed below in "Options for Renegotiating NAFTA."

Options for Renegotiating NAFTA

The Administration's official notice to Congress does not cite specific negotiating objectives for U.S. agriculture. The Trump Administration's earlier draft notice sent to congressional leadership did outline certain objectives for U.S. agriculture and SPS measures.123 USTR's request for public comment on "matters relevant to the modernization" of NAFTA, however, does address certain agricultural issues, including SPS and other technical trade barriers.124

Among the types of potential gains hoped for by U.S. agricultural exporters from "modernizing" NAFTA are improving agricultural market access (e.g., liberalization of remaining dutiable agricultural products that were exempted from the agreement and may be subject to TRQs and high out-of-quota tariff rates). Other potential areas for modernization include amending, updating, or adding to NAFTA's SPS provisions (e.g., "going beyond" existing WTO rights and obligations regarding SPS measures and requiring additional SPS enforcement). Additionally, potential gains to U.S. producers could derive from addressing certain outstanding agricultural trade disputes between the United States and its NAFTA partners and also addressing concerns regarding GIs.125

A number of these issues were addressed in the TPP agreement126 and have been raised in the T-TIP negotiations.127 Many industry representatives and some other groups claim that a successful NAFTA renegotiation would incorporate many of the types of changes related to food and agriculture agreed to in the TPP agreement.128

Some farm interest groups, however, are pushing for additional changes that go beyond those in the TPP. For example, the U.S. Biotech Crops Alliance and the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO) recommend that the U.S. enter a "mutual recognition agreement" with Canada and Mexico on "the safety determination of biotech crops intended for food, feed and for further processing" and "develop a consistent approach to managing low-level presence of products that have undergone a complete safety assessment and are approved for use" in other countries to further address how to treat agricultural shipments with trace amounts of unauthorized biotech traits.129

Improving Agricultural Market Access

Under NAFTA, tariffs and quantitative restrictions were eliminated on most agricultural products, with the exception of some that may be subject to TRQs and high out-of-quota tariff rates—such as U.S. exports to Canada of dairy products, poultry, and eggs. Some products imported to the United States may also be subject to TRQs. According to USTR, imports of U.S. products above quota levels may be subject to tariffs as high as 245% for cheese and 298% for butter.130 Canada uses supply-management systems to regulate its dairy, chicken, turkey, and egg industries, which involves production quotas and producer marketing boards to regulate price and supply, as well as TRQs and high over-quota tariffs for imports. NAFTA did not exempt agricultural products from U.S.-Mexico trade liberalization.

Renegotiating NAFTA could address trade liberalization of these additional products. USDA officials believe there are opportunities to expand U.S. exports of dairy, poultry, and eggs to Canada and Mexico and to even further expand U.S. agricultural exports overall. The Trump Administration has asked ITC to conduct an investigation into the probable economic effect of providing duty-free treatment for currently dutiable imports from Canada and Mexico, which will likely include these exempted agricultural products. In addition, ITC will assess the probable economic effects of eliminating tariffs for more than 380 "import sensitive agricultural products," most of which are currently under TRQs.131

Potential challenges remain in negotiating additional access of these exempted products, especially for milk and dairy products, given Canada's domestic subsidy and pricing policies. Major U.S. dairy market stakeholders—together with their counterparts in several dairy-exporting competitor countries—contend that these current policies violate Canada's commitments under NAFTA, the WTO, and also CETA, an FTA between the EU and Canada.132

Potential for Updating NAFTA's SPS Provisions

Several agricultural groups have noted the potential benefits of renegotiation if NAFTA were to include updated provisions regarding SPS measures.133 As highlighted by congressional and industry leaders, the need to establish "sufficiently enforceable obligations that go beyond the WTO SPS chapter" are among the primary objectives involving agricultural trade.134 Both the TPP and T-TIP negotiations addressed concerns involving SPS and TBT issues in agricultural trade that "go beyond" commitments in the SPS and the TBT agreements—referred to as "SPS-Plus" and "TBT-Plus." SPS-Plus and TBT-Plus concepts are generally intended to amplify and enhance the rights and obligations of all WTO members under these two agreements. For further background, see discussion in text box.

|

SPS-Plus and TBT-Plus provisions were described in a report submitted by U.S. and EU trade officials as part of the so-called U.S.-EU High Level Working Group on Jobs and Growth (HLWG). As part of the T-TIP negotiations, a final report submitted by U.S. and EU trade officials as part of the HLWG to advise the negotiations recommended that the United States and EU seek to establish

SPS-Plus provisions maintain core WTO SPS principles while strengthening and elaborating requirements regarding risk assessment and management, reinforcing the agreement's least-trade-restrictive principle, promoting trade-facilitating measures (e.g., equivalence, mutual recognition), and enhancing transparency and notification requirements. SPS-Plus provisions would also be fully enforceable and add some form of rapid response mechanism to facilitate trade (discussed further in the following section). Sources: HLWG, "Final Report of the U.S.-EU High Level Working Group on Jobs and Growth," February 11, 2013. See also S. Morris, "SPS and TBT Plus: Building upon the WTO in Dependable Ways," USDEC, May 23, 2017; and U.S. Grains Council, "SPS Mechanisms in TPP Agreement a Win for U.S. Agriculture," press release, October 29, 2015. |

U.S. industry groups favorably regard SPS-Plus provisions. The concluded TPP agreement included commitments on SPS and TBT rules that many in the U.S. agricultural community say generally address U.S. concerns and should be regarded as a blueprint for any subsequent negotiations involving SPS issues in agricultural trade.135 As outlined by USTR, the TPP countries agreed to a series of changes that address specific concerns, including

- allowances for public comment on proposed SPS measures to inform decisionmaking and to ensure that exporters understand the rules they will need to follow,

- assurances that import programs be risk-based and that import checks are carried out without undue delay,

- improvements in information exchange related to equivalency or regionalization requests,

- promotion of "systems-based audits to assess the effectiveness of regulatory controls" of the exporting country, and

- establishment of a mechanism for consultations between governments.136

But support for SPS-Plus is not universal. Some groups claim that efforts to modify SPS rules are an attempt to dismantle food safety regulations that some food companies view as impediments to trade and production.137 Some further assert that the TPP's SPS chapter should not be a blueprint for FTAs. They contend that such changes would "further weaken and possibly conflict with global standards setting bodies on food and plant safety."138

An ITC analysis concluded that the TPP's SPS provisions "would likely benefit U.S. firms exporting food and agriculture products to all TPP members."139 ITC also reports that, despite some opposition to the agreement's SPS provisions, most comments from agricultural interests were supportive of the SPS provisions in TPP. Industry representatives also widely supported the cooperative technical consultation process and the ability to have recourse to dispute settlement under the dispute resolution chapter for SPS measures.

Ensuring SPS Enforcement

Many have been frustrated by ongoing and protracted disputes between the United States and its NAFTA partners regarding trade in some agricultural commodities. Disputes involving the application SPS and TBT measures, such as import licensing and certification requirements, also invoke trade concerns regarding the application of domestic subsidy programs, which were explicitly not addressed in the agreement.

In addition to seeking greater transparency and more timely notifications than currently required by the WTO, other hoped-for improvements under SPS-Plus and TBT-Plus provisions are some form of "rapid response mechanism" (RRM) to improve the application of SPS and TBT measures. The ultimate goal is to adopt enforcement mechanisms or a dispute settlement process and to quickly resolve stoppages of agricultural products at the border.

Many are also advocating for additional enforceability regarding SPS measures and mechanisms to more rapidly address disputes.140 Whereas SPS-Plus means trade agreements would contain SPS rules and disciplines for agricultural trade that go beyond the WTO, SPS enforceability would further ensure that provisions in these trade agreements would have their "own self-contained SPS enforcement mechanisms that would be much quicker than the WTO dispute settlement process."141

Under TPP, there was agreement "to improve information exchange related to equivalency or regionalization requests and to promote systems-based audits to assess the effectiveness of regulatory controls" of the exporting country. In addition, there was agreement "to establish a mechanism for consultations between governments" in an effort to "rapidly resolve SPS matters.142 Some, however, claim that RRM is an attempt to push potentially unsafe food into consumer markets.143

Addressing Outstanding Trade Disputes

Some regard NAFTA renegotiations as a way to help resolve long-standing trade disputes between the partner countries for a range of sensitive agricultural products such as beef, pork, poultry, dairy, rice, and fruits and vegetables. Many have expressed the need to address ongoing concerns regarding milk and cheese,144 potatoes, and wine.145 Such disputes often involve the application of SPS and TBT measures but also the application of domestic agricultural subsidy programs in the partner countries that were explicitly not addressed in NAFTA.

USTR regularly reports on a range of ongoing trade concerns in its annual National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers (NTE) report, which covers trade barriers affecting both agricultural and non-food items between the United States and its trading partners, including Canada and Mexico. Reported outstanding trade disputes are those that are being addressed either through the WTO or NAFTA secretariat, while others may be addressed through other forms of dispute resolution, including government and industry negotiations or technical assistance.

The 2017 NTE report highlights certain outstanding issues involving SPS and TBT issues between the United States and Mexico, among which are146

- Mexico's risk assessment requirements affecting unpasteurized commercial milk exports from the United States;

- Mexico's pest quarantine of stone fruit (peach, nectarine, and apricot) growers in California, Georgia, South Carolina, and the Pacific Northwest;

- Mexico's pest quarantine requirements prohibiting the shipment of U.S. fresh potatoes beyond a 26-kilometer zone along the U.S.-Mexico border; and

- Mexico's administrative procedures and customs practices, including insufficient prior notification of procedural changes, inconsistent interpretation of regulatory requirements at different border posts, and uneven enforcement of Mexican standards and labeling rules.

For Canada, the 2017 NTE report highlights a number of U.S. concerns over agricultural products, some of which have been notified to the WTO:

- Canada's restrictions on the sale, advertising, or importation of seed varieties that are not registered in the prescribed manner;

- Canada's cheese compositional standards that limit the amount of dry milk protein concentrate (MPC) that can be used in cheese making, restricting access of certain U.S. dairy products to the Canadian market;

- Canada's practice of supply management systems regulating its dairy, chicken, turkey, and egg industries involving production quotas, producer marketing boards to regulate price and supply, and TRQs;

- U.S. concerns involving Canada's concessions to the EU as part of its trade agreement involving GIs, which may restrict the sale of certain U.S. products to Canada;

- restrictions on U.S. grain exports due to Canadian statutory grades, which are reserved exclusively for grains grown in Canada;

- restrictions within Canadian provinces that restrict the sale of wine, beer, and spirits through province-run liquor control boards; and

- Canadian restrictions involving trade in softwood lumber.

In addition, the United States has also brought other cases against Canada147 and Mexico148 within the WTO.

Not listed here are any perceived trade barriers to Mexican or Canadian agricultural exports to the United States, according to authorities in those countries.

The text box (below) further discusses two high-profile trade disputes between the United States and its NAFTA partners.

Dispute Settlement Under NAFTA

Unlike other U.S. FTAs, NAFTA contains a binational dispute settlement mechanism (Chapter 19) to review AD and CVD decisions of a domestic administrative body. Canada and Mexico sought this provision in NAFTA as a check on what they considered unfair AD/CVD decisions from U.S. administrative agencies. Under Chapter 19, a dispute settlement panel chosen from a trinational roster reviews any AD and CVD determinations that are not satisfactorily settled.

Some have called for the elimination of Chapter 19. For example, Senator Ron Wyden, ranking Member of the Senate Finance Committee, has repeatedly indicated that NAFTA renegotiation should include the "elimination of Chapter 19 of the NAFTA, which enables Canada and Mexico to challenge the way that the U.S. addresses unfairly traded imports from those countries."149 This concern stems largely from the long-standing U.S.-Canada softwood lumber dispute regarding allegedly dumped and subsidized lumber from Canada.150 In these cases, the panels have often found fault with U.S. administrative decisions, which resulted in the reduction of AD/CVD rates.

|

U.S. Ultra-Filtered Milk Exports to Canada Canada's supply management system for its dairy sector—a regime that supports milk prices at high levels relative to world market prices though quotas on domestic production together with high tariff levels and TRQs that restrict imports of dairy products—has long been a source of concern for the U.S. dairy industry. Currently, U.S. dairy interests are concerned about an ingredient pricing strategy the Canadian dairy industry is pursuing, designated as Class 7. U.S. interests assert that this pricing strategy is intended to further discourage imports of certain U.S. milk products to Canada, including ultra-filtered milk, in favor of Canadian dairy products while also facilitating exports of Canadian skim milk products beyond their allowable WTO commitments. U.S. dairy interests contend that Canada's program is designed to favor Canadian milk products at the expense of imports. They also assert that the Class 7 initiative will facilitate dumping of Canadian skim milk ingredients on world markets. In a September 2016 letter to government trade officials, major U.S. dairy market stakeholders—together with their counterparts in several dairy-exporting competitor countries—contended that the Canadian dairy industry's ingredients pricing program that was agreed to in principle (the basis for Class 7) violates Canada's commitments under NAFTA, the WTO, and the EU-Canada CETA. In an April 2017 letter, Canada's ambassador to the United States rejected assertions that Canada's dairy policies are causing financial loss for U.S. dairy farmers and that they violate Canada's international trade obligations, asserting that the U.S. dairy industry is more protectionist than is Canada's. The ambassador further points out that the Class 7 National Ingredient Strategy is an industry initiative representing an agreement among Canada's dairy producers and processors. Separately, Canadian dairy industry officials contend that the dilemma facing U.S. farmers whose supply contracts are not being extended reflects excess U.S. milk production, not Canada's dairy pricing policies. In a letter dated April 13, 2017, U.S. dairy industry groups requested that President Trump intervene directly with Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to halt the Class 7 program. In addition, several Members of Congress from Minnesota have asked President Trump to explore whether Class 7 pricing violates Canada's WTO obligations. In a recent speech, President Trump vowed to "stand up" for Wisconsin dairy farmers. Renegotiating NAFTA could provide a construct for addressing Canada's dairy ingredient pricing strategy. For more information, see CRS Report R43905, Major Agricultural Trade Issues in the 115th Congress; and CRS Insight IN10692, New Canadian Dairy Pricing Regime Proves Disruptive for U.S. Milk Producers. For information on other disputes, see CRS Report R44851, The 2006 U.S.-Canada Softwood Lumber Trade Agreement (SLA): In Brief. Mexico's Prohibitions on U.S. Fresh Potatoes Mexico continues to prohibit the shipment of U.S. fresh potatoes beyond a 26-kilometer zone along the U.S.-Mexico border, despite a series of attempts to address this issue. In 2003, the United States and Mexico signed the Table Stock Potato Access Agreement. The agreement provided a process for allowing U.S. potatoes access to all of Mexico over a three-year period. However, Mexico did not implement the agreement, citing pest detections in U.S. potato shipments—thus invoking SPS and related trade measures in this case. In 2011, the North American Plant Protection Organization released a report identifying six pests that Mexico should consider quarantine pests in potatoes for consumption. Both the United States and Mexico agreed to the report and its recommendations. In May 2014, Mexico published new import regulations for potatoes in the Diario Oficial (the official journal of the government of Mexico). These new regulations would allow the importation of U.S. potatoes into any part of Mexico. The Mexican Potato Industry Association (CONPAPA) challenged the new import regulations in Mexican courts. In July 2016, Mexican authorities issued decrees to reinstate U.S. fresh potato access to areas beyond the 26-kilometer border zone, superseding the 2014 regulations issued by Mexico's Secretariat of Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries and Food (SAGARPA) that CONPAPA had blocked with a series of court injunctions. CONPAPA then sought and obtained from Mexican courts three new injunctions against these decrees. USDA, USTR, and SAGARPA, in consultation with their respective potato industries, continue to work on ways to resolve this case. Meanwhile, U.S. potato growers are supporting NAFTA renegotiation to further address this and related SPS issues, which they recommend be addressed in a manner similar to how SPS was addressed in the TPP agreement. Sources: USTR, 2017 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers; and B. Thomson, "U.S. Potato Farmers Still Smarting From Soured Deal with Mexico," Agri-Pulse, February 28, 2017. |

Some U.S. stakeholders view Chapter 19 as unlawful151 and express concerns about whether an extrajudicial body should be able to review U.S. AD and CVD decisions. Senator Wyden said he has received assurances from the Trump Administration that NAFTA renegotiation will consider concerns regarding Chapter 19152 and also "look to improve on what was achieved in the TPP agreement."153 However, Canada and Mexico are expected to seek to retain the chapter.

While FTA partners seek to resolve disputes without resorting to dispute settlement through consultation, mediation, and negotiation, U.S. FTAs, including NAFTA, contain a formal dispute settlement mechanism (Chapter 20). These mechanisms are rarely used, as a preponderance of cases are brought to WTO dispute settlement. Three cases have been decided under NAFTA dispute settlement. If NAFTA were renegotiated to contain provisions not in the WTO body of agreements, dispute settlement under NAFTA could be used with greater frequency. Some contend that TPP may provide a model for any reworking of NAFTA's dispute resolution provisions. TPP provided for dispute resolution and contained additional disciplines. These included transparency, cooperation and alternative mechanisms (such as consultation), formal consultations and panel review within specified time frames, composition of panels, functioning and integrity of panels, private rights of action, and panel reporting.154 TPP also addressed panel report implementation to maximize compliance to the agreed obligations. It also encouraged the use of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms with respect to private commercial disputes.

Addressing Geographical Indications