Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability: Background and Issues for Congress

Changes from March 25, 2020 to June 22, 2023

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability: Background and Issues for Congress

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- Military Retirement and VA Disability Compensation

- Military Retirement

- Reserve Retirement

- Disability Retirement

- Temporary Early Retirement Authority (TERA)

- VA Disability Compensation

- Interaction of DOD and VA Disability Benefits

- Combat-Related Special Compensation (CRSC)

- CRSC for Military Disability (Chapter 61) and TERA Retirees

- The Special Rule for Disability Retirees

- CRSC for Reserve Retirees

- CRSC Eligibility Summary

- Concurrent Retirement and Disability Payments (CRDP)

- CRDP for Temporary Early Retirement Authority (TERA) Retirees

- Concurrent Receipt and Blended Retirement System Lump Sum Payments

- CRSC and CRDP Comparisons and Costs

- Other Compensation for Injuries or Deaths Related to Military Service

- Claims Brought by Veterans

- Claims Brought by Active Servicemembers

- Other Options for Congress

- Eliminate or Sunset Concurrent Receipt Programs

- Allow Concurrent Receipt for Combat-related Disabilities Only

- Extend CRDP to All Chapter 61 Disability Retirees

- Modify or Eliminate the Special Rule

- Split Compensation by Agency for Longevity and Disability

- Extend CRDP to Those with a 40% or Less VA Disability Rating

Figures

Summary

Concurrent receipt in the military context typically means simultaneously receiving two types of federal monetary benefits: Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and June 22, 2023

Veteran Disability: Background and Issues for

Kristy N. Kamarck

Congress

Specialist in Military Manpower

Concurrent receipt is the term used to describe the simultaneous receipt of two types of federal

monetary benefits. In the military context, this often describes the simultaneous receipt of

Mainon A. Schwartz

military retired pay from the Department of Defense (DOD) and disability compensation from

Legislative Attorney

the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Prior to 2004, existing laws and regulations dictated

that a military retiree could not receive two payments from federal agencies for the same purpose; military retired pay and VA disability compensation were considered to fall under that

restriction. As a result, military retirees with physical disabilities recognized by the VA had their (taxable) military retired pay offset, or reduced dollar-for-dollar, by the amount of their (nontaxable) VA compensation. Legislative activity on the issue of concurrent receipt began in the late 1980s and culminated in the provision for Combat-Related Special Compensation (CRSC) in the Bob Stump National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2003 (P.L. 107-314). Since then, Congress has added Concurrent Retirement and Disability Payments (CRDP) for those retirees with a disability rated at 50% or greater, extended concurrent receipt to additional eligible populations, and further refined and clarified the program.

Concurrent receipt is applicable only to persons who are eligible for both (1) military retirees and (2) eligible for retired pay and (2) VA disability compensation. An eligible retiree cannot receive both CRDP and CRSC. The retiree may choose whichever is most financially advantageous to him or her and may make benefit changes during an annual open season.

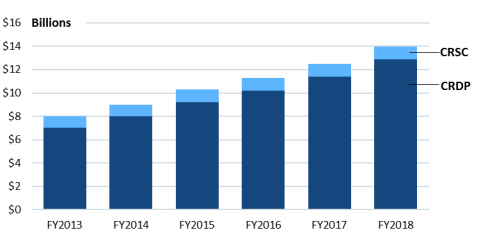

In FY2018

In FY2021, approximately 3639% of the retired military population was receiving either CRSC or CRDP at aan annual cost of $14$18.5 billion. Nevertheless, there are also military retirees who receive VA disability compensation butthat are not eligible for concurrent receipt. Determining whether to make some or all of this population eligible for concurrent receipt has been a point of contentionsubject of debate in Congress.

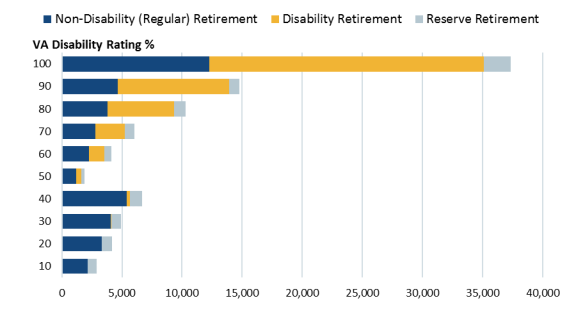

Figure 1. Estimated in Congress.

FY2013-FY2018 |

|

|

Source: Department of Defense (DOD) Office of the Actuary, Statistical Reports on the Military Retirement System. |

Introduction

Annual Concurrent Receipt Payments

FY2013-FY2021

Source: DOD Office of the Actuary, Statistical Reports on the Military Retirement System.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 10 link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 12 link to page 12 link to page 13 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 19 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 24 link to page 2 link to page 11 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 15 Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

Contents

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1

Background ............................................................................................................................... 1

Military Retirement and VA Disability Compensation .................................................................... 2

Military Retirement ................................................................................................................... 2

Reserve Retirement ............................................................................................................. 3 Disability Retirement .......................................................................................................... 3 Temporary Early Retirement Authority .............................................................................. 4

VA Disability Compensation ..................................................................................................... 4

Interaction of DOD and VA Disability Benefits ................................................................. 4

Combat-Related Special Compensation .......................................................................................... 6

CRSC for Military Disability (Chapter 61) and TERA Retirees ............................................... 7

The Special Rule for Disability Retirees ............................................................................. 7

CRSC for Reserve Retirees ....................................................................................................... 8 CRSC Eligibility Summary ....................................................................................................... 8

Concurrent Retirement and Disability Payments ............................................................................ 9

CRDP for TERA Retirees ......................................................................................................... 11

Concurrent Receipt and Blended Retirement System Lump Sum Payments ................................. 11 CRSC and CRDP Comparisons and Costs .................................................................................... 12

Funding ................................................................................................................................... 12

Other Compensation for Injuries or Deaths Related to Military Service ...................................... 14

Claims Brought by Veterans .................................................................................................... 14 Claims Brought by Active-Duty Servicemembers .................................................................. 15

Other Options for Congress ........................................................................................................... 17

Eliminate or Sunset Concurrent Receipt Programs ................................................................. 17 Allow Concurrent Receipt for Combat-related Disabilities Only ........................................... 17 Extend CRDP to All Chapter 61 Disability Retirees ............................................................... 18 Modify or Eliminate the Special Rule ..................................................................................... 18 Split Compensation by Agency for Longevity and Disability ................................................ 18 Extend CRDP to Those with a 40% or Less VA Disability Rating ......................................... 18 Consider Interactions with other Federal Benefits .................................................................. 18 Modify Concurrent Receipt Normal Cost Responsibilities ..................................................... 20

Figures Figure 1. Estimated Annual Concurrent Receipt Payments ............................................................ 2 Figure 2. Current CRSC Recipients by Disability Rating ............................................................... 7 Figure 3. CRSC Eligibility .............................................................................................................. 9 Figure 4. Current CRDP Recipients by Disability Rating ............................................................. 10 Figure 5. CRDP Eligibility ............................................................................................................. 11

Congressional Research Service

link to page 16 link to page 17 link to page 25 link to page 26 Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

Tables Table 1. Comparison of CRSC and CRDP .................................................................................... 12 Table 2. Number of Concurrent Pay Recipients and Estimated Annual Payments ....................... 13 Table 3. DOD Board of Actuaries Estimated Normal Cost Percentages ....................................... 21

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 22

Congressional Research Service

Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

Introduction Concurrent receipt in the military and veterans context typically means simultaneously receiving two types of federal monetary benefits: military retired pay from the Department of Defense (DOD) and disability compensation from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). With several separate programs, varying eligibility criteria, and several eligibility dates, some observers find the subject complex and somewhat confusing. However, concurrent Concurrent receipt is applicable only to persons who are eligible for both (1) military retirees and (2) eligible for VA retired pay and (2) VA disability compensation. This report addresses the two primary components of the concurrent receipt program: Combat-Related Special Compensation (CRSC) and Concurrent Retirement and Disability Payments (CRDP). It reviews the possible legislative expansion of the program to additional populations and provides several potential options for Congress to consider.

Background

In 1891, Congress first prohibited payment of both military retired pay and a disability pension possible legislative options for Congress to consider.

Background The historical precedent for offsets between veteran disability compensation and retired pay dates back to the 19th century. In 1890 and 1891, when Congress was debating pension policies for veterans of the Mexican War, certain Members expressed concern that some veterans drew more than one federal annuity related to military service; a combination of pension plus retired pay under the comparatively new retirement program (established in 1861), or a combination of pension plus active-duty pay.1 As part of the FY1892 appropriations act, Congress first passed legislation prohibiting concurrent payment of both military retired pay and a veteran pension under the premise that it represented dual or overlapping compensation for the same purpose. Congress modified that law in 1941, and in 19442 Similar language was included in a number of subsequent laws.3 Congress modified the statutory language in 1941 to give certain enlisted personnel a choice between retired pay or a disability pension.4

In 1944 (P.L. 78-314), Congress adopted a system of offsetting military retired pay with VA disability compensation. Under this system, retired military personnel were required to waive a portion of their retired pay equal to the amount of VA disability compensation,; a dollar-for-dollar offset.15 If, for example, a military retiree received $1,500 a month in retired pay and was rated by the VA as 70% disabled (and therefore entitled to approximately $1,000 per month in disability compensation), the offset would operate to pay $500 monthly in retired pay and $1,000 in disability compensation. Thus, the retiree still received a total of $1,500 per month, but the advantage for the retiree was that the VA disability compensation portion was not taxable. For many years some military retirees and advocacy groups sought a change in law to permit receipt of all, or some, of both payments without offset. Opponents of concurrent receipt have frequently referred to it as double dipping, maintaining that it representedrepresents two payments for the same condition. Supporters of concurrent receipt argued that the two payments were for different purposes: retired pay was deferred compensation for a career of service, while disability compensation was to account for loss future earning power.

In the FY2003 NDAA,purpose

1 Historically, the use of the term “pension” with regard to military and veteran benefits has referred to payments to a veteran based on the veteran's disability or financial need, or to the veteran's unremarried needy widow(er), or to a veteran's needy parent(s). Benefits to retired military personnel have frequently not been considered “pensions” but rather “retired or retainer pay”. This is because retirement from military service has often been characterized as reduced duty with reduced pay, due to military retirees being subject to involuntary recall to active duty.

2 During legislative debate in 1891, Members of the Senate noted that longevity pay for military personnel “upon the retired list” was intended to be compensation in full for military service and that receipt of both a disability pension and retired pay arising from the same service would be prohibited. The bill text stated, “And provided further, That hereafter no [disability] pension shall be allowed or paid to any officer, noncommissioned officer, or private in the Army, Navy, or Marine Corps of the United States, either on the active or retired list.” Senate debate, Congressional Record, vol. 22, part 3 (February 5, 1891), p. 2191.

3 Ch. 277, 27 Stat. 282, July 27, 1892; ch. 385, 31 Stat. 171, May 9, 1900; ch. 468, 34 Stat., 879, May 11, 1912; ch. 123, 37 Stat. 113; ch. 245, 41 Stat. 982, June 5, 1920; ch. 320, 43 Stat. 623, June 7, 1924. The U.S. Statutes at Large are available at https://www.loc.gov/collections/united-states-statutes-at-large/.

4 P.L. 77-140; 55 Stat. 395. 5 38 U.S.C. §§5304-5305.

Congressional Research Service

1

Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

or qualifying event.6 Supporters of concurrent receipt have argued that the two payments are for different purposes: contending that retired pay is deferred compensation for a career of service (longevity) and for availability for recall (as retainer pay), while the disability compensation is to account for lost earning power, reduced quality of life, and/or additional expenses incurred with respect to a service-connected disability.7

In the Bob Stump National Defense Act for Fiscal Year 2003 (NDAA) Congress created a benefit known as Combat -Related Special Compensation (CRSC).28 For certain disabled retirees whose disability is combat-related, CRSC provides a cash benefit financially identical to what concurrent receipt would provide them. The FY2004 NDAA authorized, for the first time, the phase-in of actual concurrent receipt (now referred to as Concurrent Retirement and Disability PaymentsPay or CRDP) for certain retirees, along with a greatlyan expanded CRSC program.39 The FY2005 NDAA further liberalized the concurrent receipt rules contained in the FY2004 NDAA and authorized immediate concurrent receipt for those with VA disability ratings totaling 100%.410 In 2007, as part of the FY2008 NDAA, Congress expanded concurrent receipt eligibility to include those who are 100% disabled due to unemployability and provided CRSC to those who were medically retired or retired prematurely due to force reduction programs prior to completing 20 years of service.5 11 The CRDP phase-in was fully implemented by 2014, and currently allows retirees with a VA disability rated at 50% or greater to receive both full retired pay and full VA disability compensation without any offset.

Military Retirement and VA Disability Compensation

Compensation An understanding of military retirement, VA disability compensation, and the interaction of these two benefits is helpful when discussing concurrent receipt.

This section outlines these concepts. Military Retirement

An active -duty servicemember typically becomes entitled to retired pay, an event frequently referred to as vesting, upon completion of 20 years of service, regardless of age. A member who retires is Retirement for longevity is typically referred to as a regular or non-disability retirement. A retired member is immediately paid a monthly annuity based on a percentage of their final base pay or the average of their high three years of base pay, depending on when they entered active duty.6 Retired pay accrues at the rate of 2.5% per year of service for those who have entered the12 Retired pay

6 See, for example, Jim Garamone, “Double-dip retirement measure may become law,” Government Executive, September 25, 2002, at https://www.govexec.com/defense/2002/09/double-dip-retirement-measure-may-become-law/12585/.

7 See, for example, Mark Belinsky, The NDAA Is the Next Battleground in the Fight for Concurrent Receipt, Military Officers Association of America (MOAA), July 6, 2022.

8 P.L. 107-314, §636; 10 U.S.C. §1413a. 9 P.L. 108-136, §§641-642. 10 P.L. 108-375, §642. 11 P.L. 110-181, §642. 12 CRS Report RL34751, Military Retirement: Background and Recent Developments, by Kristy N. Kamarck, for a detailed description of active-duty retirement.

Congressional Research Service

2

Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

accrues at a rate of 2.5% per year of service for those who entered service prior to January 1, 2018, and 2.0% for those enteringwho entered service on or after that date.7

13 Reserve Retirement

Reserve component servicemembers also become eligible for retirement upon completion of 20 years of qualifying service, regardless of age. However, their retired pay calculation is based on a point system that results in a number of equivalent years of service.814 In addition, a reserve component retiree does not usually begin receiving retired pay until reaching age 60.915 Those reservists who have retiredretire from service but do not yet receive retired pay are sometimes called gray-area retirees.

Disability Retirement

While retired pay eligibility at 20 years of service is the norm for active component members and age 60 for reserve component members

While members of the active component are generally eligible for retired pay at 20 years of qualifying service and reserve component members at age 60, earlier eligibility is possible under some circumstances. Servicemembers found to be unfit for continued service due to physical disability may be retired if the condition is permanent and stable and the disability is rated by DOD as 30% or greater.1016 These retirees are generally referred to as Chapter 61 retirees, a reference to Chapter 61 of Title 10, which covers disability retirement. As a result, some disability retirees are retired before becoming eligible for longevity retirement while others have completed 20 or more years of service.

A servicemember retired for disability may select one of two available options for calculating their monthly retired pay:

1.1. Longevity Formula. Retired pay is computed by multiplying the years of service times 2.5% or 2.0% (based on a date of entry into service before or after Jan 1, 2018), then multiplying that result by the pay base.Monthly Retired Pay= (years of service x 2.5% or 2.0%) x (pay base)2.𝑀𝑜𝑛𝑡ℎ𝑙𝑦 𝑅𝑒𝑡𝑖𝑟𝑒𝑑 𝑃𝑎𝑦 = (𝑦𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑠 𝑜𝑓 𝑠𝑒𝑟𝑣𝑖𝑐𝑒 𝑥 2.5% 𝑜𝑟 2.0%) 𝑥 (𝑝𝑎𝑦 𝑏𝑎𝑠𝑒) 2. Disability Formula. Retired pay is computed by multiplying the DOD disability percentage by the pay base.17 𝑀𝑜𝑛𝑡ℎ𝑙𝑦 𝑅𝑒𝑡𝑖𝑟𝑒𝑑 𝑃𝑎𝑦 = (𝑑𝑖𝑠𝑎𝑏𝑖𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑦 %) 𝑥 (𝑝𝑎𝑦 𝑏𝑎𝑠𝑒) The maximum disability percentage that can be used under the disability formula is 75%.18percentage by the pay base.11Monthly Retired Pay= disability % x (pay base)

The maximum retired pay calculation under the disability formula cannot exceed 75% of base pay.12 Since the disability percentage method usually results in higher retired pay, it is most commonly selected. Generally, military retired pay based on longevity is taxable. Retired pay computed

13 An alternative retirement option, known as Redux, was also available for certain active-duty servicemembers, depending on their date of entry.13

14 See CRS Report RL30802, Reserve Component Personnel Issues: Questions and Answers, by Lawrence Kapp and Barbara Salazar Torreon.

15 P.L. 109-163, §614 reduced the age for receipt of retired pay for reserve component members by three months for each aggregate of 90 days of certain types of active duty performed after January 28, 2008. Attempts since then to make this benefit retroactive to September 11, 2001, have not been successful.

16 10 U.S.C. §1201. 17 10 U.S.C. §1401. 18 Ibid.

Congressional Research Service

3

Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

under the disability formula is also fully taxed unless the disability is the result of a combat-related injury.

Temporary Early Retirement Authority (TERA)

Personnel retired due to force management requirements and before completing 20 years of service are generally referred to as "“TERA retirees" because the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1993” because the FY1993 granted Temporary Early Retirement Authority (TERA) as a force-sizing tool to entice voluntary retirements during the drawdown of the early 1990s.1319 TERA retired pay is calculated in the same way as longevity retirement, but there is a retired pay reduction of 1% of the retired pay base for every year of service below 20.

VA Disability Compensation

To years.

VA Disability Compensation20 For a veteran to qualify for VA disability compensation, the VA must make a determination that the veteran sustained a particular injury or disease, or had a preexisting condition that was aggravated, while servinghas a current disability that is causally related to a particular injury or disease sustained in or aggravated by the veteran’s service in the Armed Forces.21 in the Armed Forces.14 Some exceptions exist for certain conditions that may not have been apparent during military service but which are presumed to be service-connected. The VA has a scale of 1011 ratings, from 100% to 100%, although there is no direct arithmetical relationship between the benefits paid at each step. Each percentage rating entitles the veteran to a specific level of disability compensation.1522 In a major difference from the DOD disability retirement system, a veteran receiving VA disability compensation can ask for a medical reexamination at any time (or; a veteran who does not receive disability compensation upon separation or retirement from service can be examined or reexamined later). All VA disability compensation is tax-free, which makes receipt of VA compensation desirable, even with the operation of the offset.

Interaction of DOD and VA Disability Benefits

As veterans, military retirees can apply to the VA for disability compensation. A retiree may (1) apply for VA compensation any time after leaving the service and (2) have his or hertheir degree of disability changed by the VA as thea result of a later medical reevaluation, as noted above. Many retirees seek benefits from the VA years after retirement for a condition that may have beenwas incurred during military service but that does not manifest itself until many years later. Typical examples include hearing loss, some cardiovascular problems, and conditions related to exposure to Agent Orange.

The DOD and VA disability rating systems have much in common, but there are also significant differences. DOD makes a determination of eligibility for disability retirement only once, at the time the individual separates from the service. Although DOD uses the VA rating schedule to

19 P.L. 102-484, §4403. 20 For more information, see CRS Report R44837, Benefits for Service-Disabled Veterans, coordinated by Scott D. Szymendera.

21 While most individuals who have served in the Armed Forces of the United States may be regarded as veterans, a military retiree is ordinarily someone who: (1) has completed a full active-duty military career (almost always at least 20 years of service), or who is disabled in the line of military duty and meets certain length of service and extent of disability criteria; and (2) who is eligible for retired pay and a broad range of nonmonetary benefits from DOD after retirement. A veteran is someone who has served in the Armed Forces but may not have either sufficient service or disability to be entitled to post-service retired pay and nonmonetary benefits from DOD. Generally, all military retirees are veterans, but not all veterans are military retirees. See CRS Report R42324, Who Is a “Veteran”?—Basic Eligibility for Veterans’ Benefits, by Scott D. Szymendera. 22 VA disability compensation rates are available at https://www.benefits.va.gov/compensation/rates-index.asp.

Congressional Research Service

4

Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

time the individual separates from the service. Although DOD uses the VA rating schedule to determine the percentage of disability, DOD measures disability, or lack thereof, against the extent to which the individual can or cannot perform military duties. Military disability retired pay, unlike VA disability compensation, is usually taxable unless related to a combat disability.

As a result of the current disability process, a retiree can have both a DOD and a VA disability rating, but these ratings will not necessarily be the same percentage. The percentage determined by DOD is used to determineDOD percentage is primarily based on fitness for duty and may result in the medical separation or disability retirement of the servicemember.23 The VA disability rating, on the other hand, wasis designed to reflect the “reductions in earning capacity,” and the “ratings shall be based, as far as practicable, upon the reflect the average lossimpairments of earning power.capacity resulting from such injuries in civil occupations.”24 Two major studies published in 2007 recommended a single, comprehensive medical examination that would establish a disability rating that could be used by both DOD and the VA.16

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2008VA.25

The FY2008 NDAA required a joint DOD and VA report on the feasibility of consolidating disability evaluation systems to eliminate duplication by having one medical examination and a single-source disability rating.1726 As a result, DOD and the VA initiated a one-year pilot program, now called the Integrated Disability Evaluation System (IDES), at two military bases. The program was expanded to other sites in 2009 and 2010, and since September 2011 all new disability retirement cases at facilities worldwide have been processed through IDES.18

27

As IDES was designed to streamline the disability evaluation process, DOD and VA now focus on trying to improve sharing of health care data and records sharing, a process deemed ", a process that a congressional commission deemed “vital to Service members who are leaving the DOD system with complex medical issues and ongoing health care needs."19”28 In September 2018, DOD and VA issued a joint statement indicating their commitment to implement an integrated electronic health system in an effort to allow for seamlessstreamlined sharing of health care data between both departments and aid the disability rating process.29

23 DOD, Disability Evaluation System, DODI 1332.18, November 10, 2022, p. 6, at https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/133218e.PDF?ver=hBMKOYoIHi4EotQiJbezIA%3D%3D.

24 38 U.S.C. §1155. 25 The President’s Commission on Care for America’s Returning Wounded Warriors (commonly referred to as the Dole-Shalala commission) and the Independent Review Group on Rehabilitative Care and Administrative Processes at Walter Reed Army Medical Center and National Naval Medical Center both contained similar recommendations concerning disability processing.

26 P.L. 110-181, §1612. 27 U.S. Government Accountability Office, Military Disability System; Improved Monitoring Needed to Better Track and Manage Performance, GAO-12-676, August 2012.

28 Military Compensation and Retirement Modernization Commission (MCRMC), Final Report of the MCRMC, January 2015, p. 133, at https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a625626.pdf.

29 Statement of the Secretary of Defense and Secretary of Veterans Affairs, Electronic Health Record Modernization Joint Commitment, September 26, 2018, at https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/docs/EHRM-Joint-Commitment-Statement.pdf. For more information see CRS Report R45987, MHS Genesis: Background and Issues for Congress, by Bryce H. P. Mendez.

Congressional Research Service

5

link to page 11 Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

Combat-Related Special Compensation The FY2003 NDAA,30 as amended by the FY2004 NDAA,31 authorized CRSCdisability rating process.20

Combat-Related Special Compensation (CRSC)

The FY2003 NDAA,21 as amended by the FY2004 NDAA,22 authorized Combat-Related Special Compensation (CRSC). Military retirees with at least 20 years of service and who meet either of the following two criteria are eligible for CRSC:

-

• A disability that is

"“attributable to an injury for which the member was awarded the Purple Heart,"” and is not rated as less than a 10% disability bytheVA; or -

• A disability rating resulting from involvement in

"“armed conflict," "hazardous service," "” “hazardous service,” “duty simulating war,"” or"“through an instrumentality of war."23

”32

This definition of combat-related encompasses disabilities associated with any kind of hostile force; hazardous duty such as diving, parachuting, or using dangerous materials such as explosives; and individual training and unit training and exercises and maneuvers in the field. Instrumentalities of war include vehicles, vessels, or devices designed primarily for military service, for examplelike combat vehicles, Navy ships, and military aircraft. Injuries associated with instrumentalities of war may also be those associated with, for example, munitions explosions or inhalation of gases or vapors in combat training.

Retirees must apply for CRSC to their parent service

For CRSC, retirees must apply to their parent service (i.e., Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, or Space Force), and the parent service is responsible for verifying that the disability is combat-related. This process is not automatic; it is application-driven. CRSC payments will generally be equal to the application-driven, not automatic. CRSC payments are calculated by the amount of VA disability compensation that has been determined to be combat-related. The CRSC legislation does not end the requirement that the retiree'’s military retired pay be reduced by the amount of the total VA disability compensation the retiree receives. Instead, CRSC beneficiaries are to receive the financial equivalent of concurrent receipt as "“special compensation," but the statute states explicitly that it.” The statute explicitly states that CRSC is not retired pay.33 As of September 2021, a total of 95,001 retirees were receiving CRSC (see Figure 2).34

30 P.L. 107-314, §636. 31 P.L. 108-136, §642. 32 The FY2003 NDAA (P.L. 107-314) required that the disability be rated at least 60%. This requirement was repealed by the FY2004 NDAA (P.L. 108-136).

33 10 U.S.C. §1413a(g). 34 DOD Office of the Actuary, Statistical Report on the Military Retirement System: Fiscal Year Ended September 30, 2021, September 2022, p. 28.

Congressional Research Service

6

Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

is not retired pay per se. CRSC payments are paid from the DOD Military Retirement Fund.24 As of September 2018, a total of 93,106 retirees were receiving CRSC (see Figure 2).25

CRSC for Military Disability (Chapter 61) and TERA Retirees

Servicemembers with a permanent DOD disability rating of 30% or greater may be retired and receive retired pay prior to completing 20 years of service. TheseAs noted earlier, these retirees are generally referred to as "Chapter 61" retirees, a reference to Chapter 61, Title 10, which governs disability retirement retirees. In addition to the Chapter 61 retirees with less than 20 years of service, those who voluntarily retired under the Temporary Early Retirement Authority (TERA)TERA are also eligible for CRSC. The original CRSC legislation excluded those active -duty members who retired with less than 20 years of service.

The FY2008 NDAA expanded CRSC to include Chapter 61 and active -duty TERA retirees effective January 1, 2008.2635 Eligibility no longer requires a minimum number of years of service or a minimum disability rating (other than the 30% DOD rating noted above for disability retirement); a 10% VA rating may qualify if it is combat-related. Eligible retirees must still apply to their parent service to validate that the disability is combat-related.

The FY2008 NDAA included almost all reserve disability retirees in the eligible CRSC population except those retired under 10 U.S.C. §12731b, 12731b, a special provision which allows reservists with a physical disability not incurred in the line of duty to retire with between 15 and 19 creditable years of service.

36 The Special Rule for Disability Retirees

As noted earlier, an individual generally cannot receive

Historically, Congress has generally prohibited an individual from receiving two separate lifelong government annuities from federal agencies for the same purpose or qualifying event, for example, disability retired pay and VA disability compensation. To preclude this, there is a special rule for Chapter 61 disability retirees.. When

35 P.L. 110-181, §641. 36 Ibid.; 10 U.S.C. §12731b.

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 13 Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

authorizing CRSC, Congress created a special rule for Chapter 61 disability retirees who may be eligible for both DOD disability retired pay and VA disability compensation.37 Application of the special rule caps the CRSC at the level toamount at which the retiree could have qualified based solely on years of service or longevity(longevity). In some instances, the special rule could limit or completely eliminate the concurrent receipt payment. In other instances, application of the rule may not result in any changes. Each individual’s situation is unique (e.g., rank, years of service, DOD and VA disability ratings, and the disability percentage attributable to combat) and, as such, requires independent calculations.

Those most likely to see a reduction ofreceive smaller benefits under CRSC due to the special rule are active -duty servicemembers with a disability retirement who have significantly less than 20 years of service and a high VA disability rating. Reserve members with little active duty-duty time could also be impacted.

CRSC for Reserve Retirees

When CRSC was originally enacted in 2002, it required all applicants to have at least 20 years of service creditable for computation of retired pay. As a result, reserve retirees had to have at least 7,200 reserve retirement points (which converts to 20 years of equivalent service) to be eligible for CRSC. As noted earlier, a reservist receives a certain number of retirement points for varying levels of participation in the reserves, or active -duty military service. The 7,200-point figure could only have been attained by a reservist who had many years of active -duty military service in addition to a long reserve career. Initially this law, as enacted,As enacted, this law effectively denied CRSC to almost all reservists.

However, a provision in the FY2004 NDAA revised the service requirement for reserve component personnel. It specified that personnel who qualify for reserve retirement by having at least 20 years of duty creditable for reserve retirement are eligible for CRSC.38 While eligible for CRSC, reserve retirees must be drawing retired pay (generally, at age 60) to actually receive the CRSC payment.

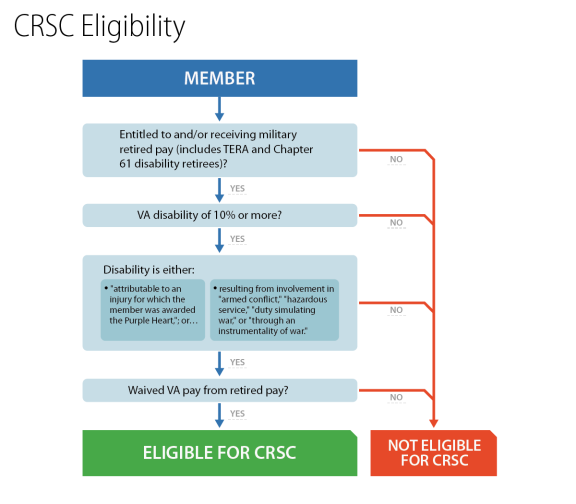

CRSC Eligibility Summary

Essentially, all military retirees who have combat-related disabilities compensable by the VA are eligible for CRSC (seesee Figure 3). Military retirees with service-connected disabilities whichthat are not combat-related as defined by the statute are not eligible for CRSC, but may be eligible for CRDP , as discussed below.

37 10 U.S.C. §1413a(b)(3), “Special Rules for Chapter 61 Disability Retirees.” 38 P.L. 108-136, §§641-642.

Congressional Research Service

8

Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

Figure 3. CRSC Eligibility

Source: CRS, Title 10 of the U.S. Code. as discussed below.

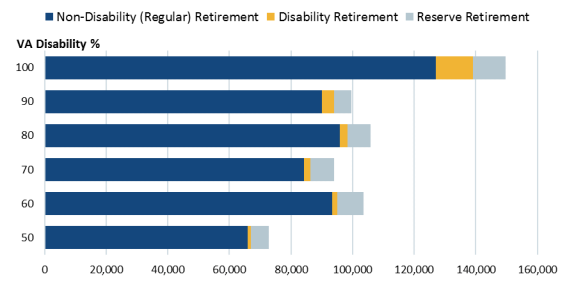

Concurrent Retirement and Disability Payments (CRDP)

The FY2004 NDAA authorized, for the first time, actualfull concurrent receipt of retired pay and veteran disability compensation for retirees with at least a 50% disability, regardless of the cause of disability.2739 The amount of concurrent receipt was phased in over a 10-year period, from 2004 to 2013, except for with regard to 100% disabled retirees, who became entitled to immediate concurrent receipt effective January 1, 2005. In 2014, all offsets ended; military retirees with at least a 50% disability became eligible to receive their entire military retired pay and VA disability compensation. In FY2021, 751,777 retirees received CRDP.40

39 P.L. 108-136, §641. 40 DOD Office of the Actuary, Statistical Report on the Military Retirement System: Fiscal Year Ended September 30, 2021, September 2022, p. 25.

Congressional Research Service

9

link to page 15

Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

concurrent receipt effective January 1, 2005. Depending on the degree of disability, the initial amount of retired pay that the retiree could have restored would vary from $100 to $750 per month, or the actual amount of the offset, whichever was less. In 2014, all offsets ended; military retirees with at least a 50% disability became eligible to receive their entire military retired pay and VA disability compensation. In FY2018 there were 625,765 retirees receiving CRDP.28

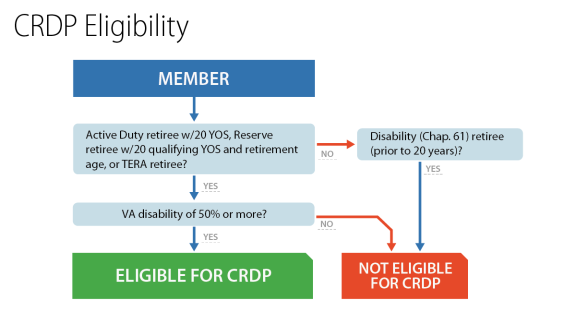

A retiree cannot receive both CRSC and CRDP benefits. The retiree may choose whichever is more financially advantageous to him or her and may change the type of benefit to be received during an annual open season to maximize the payments receivedand may change their election during an annual open season to maximize payments. There are currently two groups of retirees who are not eligible for CRDP benefits (seesee Figure 5). The first group is nondisabilitynon-disability military retirees with service-connected disabilities that have been rated by the VA at 40% or less. The second group includescomprises Chapter 61 disability retirees with service-connected disabilities and lessfewer than 20 years of service.

Congressional Research Service

10

link to page 11

Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

Figure 5. CRDP Eligibility

Source: CRS, Title 10 of the U.S. Code. Notes: “Member” than 20 years of service.

|

Source: CRS, Title 10 of the United States Code.

|

CRDP for Temporary Early Retirement Authority (TERA) Retirees

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1993 granted temporary authority for the services to offer early retirements to personnel with more than 15 but less than 20 years of service.2941 This authority was extended in subsequent authorization bills. TERA was used as a force-sizing tool to entice voluntary retirements during the post-Cold War drawdown. TERA retired pay was calculated in the usual way except that there is an additional reduction of 1% for every year of service below 20. Part or all of this latter reduction could be restored if the retiree worked in specified public service jobs (such as law enforcement, firefighting, and education) during the period immediately following retirement, until the point at which the retiree would have reached the 20-year mark if he or she had remained in the service.

–Cold War drawdown.

TERA retirees are eligible for CRSC and CRDP even though they have lessfewer than 20 years of service. The special rule for disability retirees (see "see “The Special Rule for Disability Retirees”) ") does not apply to TERA retirees since TERA is not a disability retirement, but rather a regular retirement but for those with less than 20 years of service.

considered a disability retirement. Concurrent Receipt and Blended Retirement System Lump Sum Payments

The Blended Retirement System (BRS), effective for all servicemembers joining on or after January 1, 2018, offers servicemembers the option to select a lump sum payment of a portion of their military retired pay in lieu of a monthly annuity.3042 If a member retiring under the BRS is eligible for CRDP and elects the lump sum payment of retired pay, the individual is to continue to receivecontinues receiving a monthly VA disability payment. If the member electing the lump sum payment is not eligible for CRDP (i.e., the retired pay offset applies), the VA is to withhold disability payments until the VA withholds disability payments until the

41 P.L. 102-484, §4403. 42 For more information on the BRS, see CRS Report RL34751, Military Retirement: Background and Recent Developments, by Kristy N. Kamarck.

Congressional Research Service

11

link to page 16 Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

sum of the amount withheld over time equals the gross amount of the lump sum payment.3143 If the member is eligible for CRSC, the procedures for withholding VA disability payments relate to the combat-related portion of the total VA entitlement.32

44 CRSC and CRDP Comparisons and Costs

CRSC and CRDP share some common elements, but are unique benefitsbenefits. Table 1 summarizes some of the similarities and differences between CRSC and CRDP.

Table 1. Comparison of CRSC and CRDP

CRSC

CRDP

Classification

Special compensation

Military retired pay

Qualified disabilities

Combat-related disabilities

Service-connected disabilities

Enrol ment

Must apply to parent service for

Automatic, initiated by

verification that disability is combat-

Defense Finance and

related

Accounting Service (DFAS)

Type of Compensation

Special compensation (not retired

Restored retired pay

pay)

Tax Liability

Nontaxable

Taxable

Subject to Division with a Former Spouse No

Table 1. Comparison of CRSC and CRDP

|

CRSC |

CRDP |

|

|

Classification |

Special compensation |

Military retired pay |

|

Qualified disabilities |

Combat-related disabilities |

Service-connected disabilities |

|

Enrollment |

Must apply to parent service for verification that disability is combat-related |

Automatic, initiated by DFAS |

|

Type of Compensation |

Special compensation (not retired pay) |

Restored retired pay |

|

Tax Liability |

Nontaxable |

Taxable |

|

Subject to Division with a Former Spouse |

No |

Yes (longevity retired pay portion only)a

Subject to Garnishment for Alimony

Yes

Yes (longevity retired pay

and/or Child Support

portion only)

Source: Derived from DFAS |

|

Subject to Garnishment for Alimony and/or Child Support |

Yes |

Yes (longevity retired pay portion only) |

Source: Derived from Defense Finance and Accounting Service (DFAS) chart at http://www.dfas.mil/retiredmilitary/disability/comparison.html.

. Note: Under 10 U.S.C. §1408, the amount of retired pay related to the individual'’s disability is not subject to division with a former spouse or subject to alimony payments. For more information on division of retired pay with former spouses, see CRS Report RL31663, Military Benefits for Former Spouses: Legislation and Policy Issues, by Kristy N. Kamarck.

Funding CRDP and CRSC are paid from the DOD Military Retirement Fund.33 Costsfunded through accrual payments to the DOD Military Retirement Fund (MRF) established under 10 U.S.C. §1461.45 DOD and the Department of Homeland Security (for the Coast Guard) make contributions to the MRF through annual appropriations to account for the cost of future retirees.46 This contribution is a percentage of basic pay for members of the Armed Forces, called the normal cost percentage (NCP). The U.S. Department of Treasury is responsible for mandatory contributions to the fund to account for the unfunded liability incurred at the

43 DOD, Deputy Secretary of Defense, “Implementation of the Blended Retirement System,” memorandum, January 27, 2017.

44 DOD Office of the Actuary, Statistical Report on the Military Retirement System for Fiscal Year 2017, July 2018, p. 13.

45 Although CRSC is paid from the Military Retirement Fund, it is not technically considered retired pay. 46 10 U.S.C. §1466.

Congressional Research Service

12

link to page 17 Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

establishment of the MRF in fiscal year 1985 and for the addition of the Coast Guard to the fund in fiscal year 2023.47 The DOD Board of Actuaries determines the NCPs for DOD and Treasury.48

In 2003, when Congress authorized concurrent receipt benefits, it specified that DOD’s contributions would be determined “without regard to” the concurrent receipt benefits, having the practical effect of giving Treasury the responsibility for normal cost payments for concurrent receipt benefits.49 According to the DOD Board of Actuaries,

We believe the original intent of the Concurrent Receipt rules was to limit the increase in DoD costs triggered by eliminating VA disability benefit offsets and increasing MRF liabilities, not to transfer the majority of NCP funding responsibility to Treasury. The current situation appears to be an unintended consequence driven by the increased VA disability benefit utilization, and a potential misapplication of the Concurrent Receipt rule relative to its original intent.50

Payments out of the fund have been rising every year as a consequence of the phased implementation and a rise in the number of eligible recipients.3451 As of September 2018, 362021, 38.8% of all military retirees collecting retired pay were receiving either CRDP or CRSC.35

(see Table 2).52

Table 2. Number of Concurrent Pay Recipients and Estimated Annual Payments

FY2009-FY2021

CRDP

CRSC

Estimated

Estimated

Annual

Annual

% of Total Retirees

Fiscal

Number of

Payments

Number of

Payments

Receiving CRDP or

Year

Recipients

(billions)

Recipients

(billions)

CRSC

FY2021

751,777

$17.3

95,001

$1.2

38.8%

FY2020

711,219

$15.8

95,613

$1.2

36.9%

FY2019

670,611

$14.4

95,626

$1.2

35.2%

FY2018

625,765

$12.8

93,106

$1.1

35.9%

FY2017

577,399

$11.4

91,137

$1.1

33.5%

FY2016

529,117

$10.2

91,305

$1.1

31.2%

FY2015

486,632

$9.2

88,610

$1.1

29.0%

FY2014

438,455

$8.0

86,320

$1.0

26.6%

47 10 U.S.C. §1465. The National Defense Authorization Act for FY2021 (P.L. 116-283) required the Coast Guard be added to the MRF beginning in FY2023.

48 10 U.S.C. §1465. 49 P.L. 108-136 §641; 10 U.S.C. §§1465, 1466(c)(2)(D). 50 Letter from DOD Board of Actuaries to Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III, “RE: Transferring the Cost of the Military Retirement Fund (MFR) from DoD to Treasury Due to Increasing Concurrent Receipt Benefits,” December 2, 2022, on file with the authors.

51 The number of veterans eligible for disability pay has been increasing in part due to policy changes that have increased outreach, improved claims processing and designated additional conditions for benefit eligibility. Increases in VA disability claims have also been attributed to the specific types of injuries suffered by veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts.

52 DOD Office of the Actuary, Statistical Report on the Military Retirement System for Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 2021, September 2022.

Congressional Research Service

13

Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

CRDP

CRSC

Estimated

Estimated

Annual

Annual

% of Total Retirees

Fiscal

Number of

Payments

Number of

Payments

Receiving CRDP or

Year

Recipients

(billions)

Recipients

(billions)

CRSC

FY2013

395,143

$7.0

82,929

$1.0

24.4%

FY2012

355,938

$6.1

78,379

$0.9

22.3%

FY2011

318,862

$5.2

76,358

$0.9

20.4%

FY2010

298,865

$4.6

73,890

$0.8

19.4%

FY2009

260,092

$3.9

72,549

$0.8

17.5%

Source: DOD Office of the Actuary, Statistical Reports on the Military Retirement System, Number of Military Retirees by State and Number of Military Retirees Receiving Concurrent Receipt by State. Data are current as of September 30 of the designated fiscal year. Notes: Some retirees may be eligible for both CRSC and CRDP but can only receive one or the other. Payments are made from the DOD MRF. The phase-in period for ful Table 2. Number of Concurrent Pay Recipients and Estimated Annual Payments

FY2009-FY2018

|

Fiscal Year |

CRDP |

CRSC |

|||||||||||

|

Number of Recipients |

Annual Payments (billions) |

Number of Recipients |

Annual Payments (billions) |

% of Total Retirees Receiving CRDP or CRSC |

|||||||||

|

FY2018 |

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||

|

FY2017 |

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||

|

FY2016 |

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||

|

FY2015 |

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||

|

FY2014 |

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||

|

FY2013 |

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||

|

FY2012 |

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||

|

FY2011 |

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||

|

FY2010 |

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||

|

FY2009 |

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||

Source: DOD Office of the Actuary Statistical Reports on the Military Retirement System.

Notes: Some retirees may be eligible for both CRSC and CRDP but can only receive one or the other. Annual payments are made from the DOD Military Retirement Fund. The phase-in period for full CRDP was complete on December 31, 2013.

2013.

Other Compensation for Injuries or Deaths Related to Military Service

Another way that deceased or disabled servicemembers or their families couldcan potentially obtain government compensation would beis by suing the government in court. However, the United States has sovereign immunity, which prevents private citizens from suing it in court unless the government consents to the suit.36

53

Claims Brought by Veterans

Congress has waived the United States'’ sovereign immunity in certain circumstances, including for some tort claims for injuries or deaths caused by negligent or wrongful acts of federal employees.3754 Subject to various exceptions and conditions, the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA) of 1946 generally authorizes plaintiffs to bring civil lawsuits:

- • against the United States;

- • for money damages;

- • for injury to or loss of property, or personal injury or death;

- • caused by a federal employee

'’s negligent or wrongful act or omission; - • while acting within the scope of his or her office or employment;

- • under circumstances where the United States, if a private person, would be liable

to the plaintiff in accordance with the law of the place where the act or omission occurred.

38

55

53 See, for example, FDIC v. Meyer, 510 U.S. 471, 475 (1994) (“Absent a waiver, sovereign immunity shields the Federal Government and its agencies from suit.”).

54 28 U.S.C. §§1346(b), 2671-80. 55 Ibid. For more about the FTCA, including exceptions to the general rule that are not discussed herein, see CRS Report R45732, The Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA): A Legal Overview.

Congressional Research Service

14

Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

The FTCA thus authorizes veteransThe FTCA thus authorizes veterans39 in certain circumstances to sue the United States for the negligent or wrongful acts of federal employees.56 Most relevant to the disability context, such lawsuits can include suits involving VA medical personnel acting within the scope of their employment.40

57

While a court may award a plaintiff money damages in an FTCA suit for medical malpractice or other injuries caused by the VA, Congress specifically provided that such FTCA judgments would postpone VA disability benefits related to the same injury until the amount of forestalled benefits equalsequaled the amount of the judgment.4158 In other words, a veteran who wins or settles a medical malpractice lawsuit is to havehas their VA benefits withheld in the same amount of the award.4259 For example, if a veteran suffered an injury at a VA hospital that resulted in a disability that entitled her to $1,000 per month, but he or she sued theshe also sued VA under the FTCA and was awarded $50,000 in damages, his or her disability benefits would be withheld for four years and two months (i.e., 50 months) following that award. For very large awards, the veteran might not receive any further monthly benefits because the cumulative withheld benefits would never exceed the full amount of the award.

Claims Brought by Active Servicemembers

-Duty Servicemembers

The Feres doctrine limits active-duty servicemembers’ suits against the United States.

Congress specifically excluded claims arising out of wartime military combatant activities from the FTCA,43 meaning that wartime active-duty servicemembers who were injured or died as a result of combatant activities could not sue the federal government for compensation.

In 1950, the Supreme Court determined that the United States was more broadly60 meaning that the United States is immune from suit for compensation based on wartime active-duty servicemembers’ injuries or deaths from combatant activities.

In 1950, the Supreme Court recognized an additional limitation on servicemember lawsuits, holding that the United States is immune from suit for injuries to active-duty servicemembers whenever the injuries arise out of, or occur during, activities related to military service.44“incident to service.”61 Unlike the explicit statutory bar on lawsuits arising out of combatant activities, the bar on lawsuits arising out of military service activities is a judicially created exception to the FTCA without any explicit textual basis.4562 This exception came to beis known as the Feres doctrine, named for the Supreme Court case dismissing claims brought by or on behalf of several servicemembers who sustained injuries due to the to alleged negligence of others in the armed forces.46 The Supreme Court has routinely declined invitations to revisit or alter the Feres doctrine in subsequent years.47

The FY2020 NDAA, however, newly authorizes63 The Supreme Court has routinely

56 As discussed below, the status of active military servicemembers is different from veterans, who are no longer in active military service. See, for example, Bush v. Secretary of Dep’t of Veterans Affairs, 2014 WL 127092, at *6 (S.D. Ohio Jan. 13, 2014).

57 See, for example, Levin v. United States, 568 U.S. 503 (2013) (permitting a suit under the FTCA brought by a veteran who suffered injuries as a result of cataract surgery performed by a Navy doctor at a military hospital).

58 38 U.S.C. §1151(b)(1). 59 Ibid. See also 28 U.S.C. §2672 (discussing administrative settlement of claims). 60 28 U.S.C. §2680(j). 61 Feres v. United States, 340 U.S. 135, 146 (1950). 62 The FTCA defines “employee of the government” to include “members of the military or naval forces of the United States.” 28 U.S.C. §2671. 63 Feres, 340 U.S. at 136-37. The case involved three plaintiffs: the executrix of a servicemember who died in a barracks fire, alleging that the government should have known the barracks was unsafe; a servicemember in whose stomach a military surgeon allegedly left a 30-inch by 18-inch towel; and the executrix of a servicemember who allegedly died because of negligent treatment by army surgeons. Ibid. All three claims were dismissed because of the United States’ sovereign immunity, which the Supreme Court held that Congress had not waived. Ibid. at 146.

Congressional Research Service

15

Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

declined invitations to revisit or alter the Feres doctrine,64 although at least one member of the Court routinely dissents from denials of certiorari and urges that Feres should be overruled.65

Congress has authorized some actions that would otherwise be barred by the Feres doctrine.

In 2019, Congress enacted a provision in the FY2020 NDAA authorizing the Secretary of Defense to allow, settle, and pay an administrative claim against the United States for personal injury or death of a servicemember caused by a DOD health care provider'’s medical malpractice.4866 Similar provisions had been previously introduced in both houses as the SFC Richard Stayskal Military Medical Accountability Act,4967 named for a Purple Heart recipient whose misdiagnosis while he was on active duty allegedly allowed a cancer to spread until it became terminal.50 The standalone bills would have allowed lawsuits in federal court rather than directing claims to a DOD administrative proceeding.51

The provision in the FY2020 NDAA thus circumscribed the Feres doctrine for68

The provision authorizing DOD administrative settlements, codified at 10 U.S.C. §2733a, thus provides a path for relief in cases alleging medical malpractice by DOD health care providers. Although it does not allow lawsuits in federal court (and thus does not technically alter the Feres doctrine), it does provide an avenue by which some servicemembers may settle a claim forreceive compensation for certain injuries or disabilitiesfor an injury or disability—conceivably, for the same injury or disability that might entitle them to disability retired pay or VA disability compensation. The DOD regulations clarify that an administrative medical malpractice claim “will have no effect on any other compensation the member or family is entitled to under the comprehensive compensation system applicable to all members,” but that a claimant may not “receive duplicate compensation for the same harm.”69

In 2022, in the Camp Lejeune Justice Act, Congress created another path for certain medical malpractice claims that would otherwise likely be barred by the Feres doctrine.70 Under that act, individuals (including veterans) who were exposed to contaminated water at Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune in North Carolina for at least 30 days between August 1, 1953, and December 31, 1987, may sue the United States for harm caused by that exposure.71 Claims under this law must be made no later than August 10, 2024, or 180 days after the date on which the claim is denied by the appropriate federal agency, whichever is later.72 Claims arising out of combatant activities are

64 For example, Daniel v. United States, 889 F.3d 978, 982 (9th Cir. 2018), cert. denied, 139 S. Ct. 1713 (2019) (“If ever there were a case to carve out an exception to the Feres doctrine, this is it. But only the Supreme Court has the tools to do so.”). For more information, see CRS In Focus IF11102, Military Medical Malpractice and the Feres Doctrine, by Bryce H. P. Mendez and Andreas Kuersten; and CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10305, The Feres Doctrine: Congress, the Courts, and Military Servicemember Lawsuits Against the United States.

65 See, e.g., Clendening v. United States, 143 S. Ct. 11, 12 (2022) (Thomas, J., dissenting) (“As I have explained several times, Feres should be overruled.”).

66 P.L. 116-92, §731 (codified at 10 U.S.C. §2733a). 67 S. 2451, 116th Cong. (2019); H.R. 2422, 116th Cong. (2019). 68 Ibid. The House version of the FY2020 NDAA likewise took this approach. H.R. 2500 §729, 116th Cong. (2019). This approach was not adopted in enacted law.

69 32 C.F.R. §45.1(b). 70 P.L. 117-168; 136 Stat. 1759 (2022). 71 The U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina has exclusive jurisdiction over these cases once the claimant has received a disposition by the relevant federal agency. P.L. 117-168, §804(d), (h).

72 P.L. 117-168, §804(j)(2).

Congressional Research Service

16

Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

expressly excluded from the act.73 Relief awarded under this law will be offset by the amount of any support for any healthcare or disability benefits related to water exposure at Camp Lejeune received from programs administered by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Medicare, or Medicaid.74

them to disability retired pay or VA disability compensation.

It is unclear whether payments under this administrative process will require the Secretary to withhold retired pay or disability benefits in the amount of any settlement or award. Generally, administrative adjustment of claims under 28 U.S.C. § 267252 are subject to the same withholding of veterans benefits in the amount of the award as court judgments.53 However, § 2733a may only be used to settle claims "not allowed to be settled and paid under any other provision of law," so it seems to exclude claims that could be settled under the FTCA's administrative process.54

Other Options for Congress

Other Options for Congress Veteran advocacy groups continue to lobby for changes to the concurrent receipt programs that would expand benefits to a larger population of retirees. Other groups have pressed Congress to offset or streamline duplicative benefits, contending that the dual receipt of VA and DOD payments amounts to double-dipping, or in some cases triple-dipping for those veterans also eligible for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) from the Social Security Administration.55

75

Some of the factors that Congress might consider regarding potential changes include program costs, funding, program efficiencies, individual eligibility requirements, and interaction with other servicemembers'servicemembers’ and veterans'’ benefits and programs. Below are some options to change concurrent receipt programs that have been proposed or considered.

Eliminate or Sunset Concurrent Receipt Programs

The Congressional Budget Office has previously estimated that eliminating the CRDP would save the government $139 billion between 2018 and 2026.5676 While achieving significant cost savings, eliminating or sunsetting CRDP, CRSC, or both could be unpopular among servicemembers, veterans, and their families. Some previous efforts to reduce benefits to servicemembers have included a grandfather clause that would allow all current servicemembers and retirees to maintain existing benefits while the law would only apply to those who would have joined the service after a specific date.

Allow Concurrent Receipt for Combat-related Disabilities Only

One option could be to eliminate concurrent receipt for noncombat-related disabilities. This option would essentially repeal CRDP and expand CRSC to allow for any retired member to receive concurrent DOD and VA payments, but only for the amount of the disability determined to be combat-related under existing law or other defined criteria. A member could continue to receive VA disability payments and retired pay, but the offset would be applied to the portion of VA disability compensation not related to combat. This would have the effect of reducing or eliminatingreduce or eliminate the concurrent benefit for some military retirees with rated disabilities of 50% or greater that are not related to combat.

Extend CRDP to All Chapter 61 Disability Retirees

73 P.L. 117-168, §804(i). 74 P.L. 117-168, §804(e)(2). 75 Romina Boccia, Triple-Dipping: Thousands of Veterans Receive More than $100,000 in Benefits Every Year, The Heritage Foundation, November 6, 2014, at https://www.heritage.org/social-security/report/triple-dipping-thousands-veterans-receive-more-100000-benefits-every-year. For more information on SSDI benefits, see CRS Report R44948, Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI): Eligibility, Benefits, and Financing, by William R. Morton. 76 Congressional Budget Office, Options for Reducing the Deficit: 2017 to 2026: Option 11, Eliminate Concurrent Receipt of Retirement Pay and Disability Compensation for Disabled Veterans, Washington, DC, December 8, 2016. Congressional Research Service 17 Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability Extend CRDP to All Chapter 61 Disability Retirees As previously discussed, the FY2008 NDAA extended CRSC eligibility to Chapter 61 retirees who retired due to combat-related physical disability prior to completing 20 years of service. However, Chapter 61 retirees with service-connected disabilities rated less than 50% or with less than 20 years of service are not eligible for CRDP. Congress could expand the CRDP provision to include this cohort. Some observers may note that eliminating or modifying the special rule would result in paying for the same disability twice, by DOD and by VA.

Modify or Eliminate the Special Rule

With the extension of CRSC to Chapter 61 disability retirees, the special rule factors significantly into the concurrent receipt calculations The special rule affects concurrent receipt calculations for Chapter 61 disability retirees. For those whose CRSC payment is limited or eliminated by the special rule, there may be a perceived inequity between CRSC recipients with 20 or more years of service (longevity retirees) and Chapter 61 retirees (disability retirees who generally have less than 20 years of service) retirees.

.

To resolve this potential issue, Congress could modify or eliminate the special rule or limit its application to specific military operations. Again, eliminating or modifying the special rule would result in a situation that could be perceived as paying for the same disability twice, by DOD and by VA.

Split Compensation by Agency for Longevity and Disability

Another option would be to completely overhaul the military retirement and disability system whereby DOD would only compensate for years of service and the VA would only compensate for disability, as recommended by the Dole-Shalala commission in 2007.5777 This commission recommended that in all cases DOD annuity payments should be "“based solely on rank and length of service,"” while the VA should "“assume all responsibility for establishing disability ratings and for all disability compensation and benefits programs."”78 Under this scenario, Chapter 61 retirees would not have eligibility to have DOD retired pay calculated under the disability formula. This could make the calculation of retired pay and disability compensation for these retirees less complex.

Extend CRDP to Those with a 40% or Less VA Disability Rating

At present, those military retirees with service-connected disabilities rated at 50% or greater are eligible for CRDP. Congress could revise the concurrent receipt legislation to include the entire population of military retirees with service-connected disabilities. In 2014, CBO estimated that to extend benefits to all veterans who would be eligible for both disability benefits and military retired pay would cost $30 billion from 2015 to 2024.79

Consider Interactions with other Federal Benefits One option for Congress might be to consider the total monetary benefits that a veteran receives from the federal government. Part of the historical basis for post-service compensation from as early as the 1800s was to account for a physical disability incurred in military service or to

77 Serve, Support, Simplify: Report of the President’s Commission on Care for America’s Returning Wounded Warriors, co-chaired by Bob Dole and Donna Shalala, July 2007.

78 Ibid. 79 Congressional Budget Office, Veterans’ Disability Compensation: Trends and Policy Options, Washington, DC, August 2014.

Congressional Research Service

18

Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

provide economic security for aged veterans.80 In the decades since, the government has established several other income security programs. As noted by the Bradley Commission in 1956, due in part to the establishment of a social security system,

The basic needs of all citizens, veterans and nonveterans alike, for economic security are being increasingly met through general Federal, State, and private programs. […] These general income-maintenance expenditures […] benefit veterans and their families as well as the general population.

The disability benefits programs of Government agencies are expanding. Various disability programs affect veterans, but there appear to be great differences in philosophy and purpose. There is a need for better coordination and for common standards on a governmentwide basis.81

Congress has, in the past, expressed concern about the sustainability of social security benefits and potential overlaps in disability benefits. In 2014, in response to a congressional inquiry into the compensation received by disabled military personnel, the Government Accountability Office reported that a total of 2,304 military retirees received concurrent federal payments of $100,000 or more from DOD retirement, VA disability compensation, and SSDI—with one beneficiary receiving the highest total of $208,757 annually.82

More recently, in a 2022 report, CBO proposed options for amending VA disability benefits law to reflect eligibility for other federal benefits. One such option would reduce VA disability benefits paid to veterans who are older than the full retirement age for social security. The stated rationale for this option was,

VA’s disability payments are intended to compensate for the average earnings that veterans would be expected to lose given the severity of their service-connected medical conditions or injuries, whether or not a particular veteran’s condition actually reduced his or her earnings. Disability compensation is not means-tested: Veterans who work are eligible for benefits, and most working-age veterans who receive such compensation are employed. After veterans reach Social Security’s full retirement age, VA’s disability payments continue at the same level. By contrast, the income that people receive from Social Security or private pensions after they retire usually is less than their earnings from wages and salary before retirement.83

Some observers have argued that lawmakers should consider a broad “modernization of the disability ratings system” including implementing means-testing in the name of fiscal responsibility.84 Such an effort might consider disability compensation with respect to the earnings potential of veterans in the contemporary economy. Since at least the Civil War, earning capacity for the purpose of VA disability benefits was largely based on the individual’s ability to

80 DOD, "Chapter III.B.3. Disability Retired Pay," in Military Compensation Background Papers, 8th ed. (2018), p. 599.

81 Veteran's Benefits in the United States, A Report to the President by the President's Commission on Veterans's Pensions, April 1956, p. 8, at http://www.veteranslawlibrary.com/files/Commission_Reports/Bradley_Commission_Report1956.pdf.

82 U.S. Government Accountability Office, Disability Compensation: Review of Concurrent Receipt of Department of Defense, GAO-14-854R, September 30, 2014, p. 4, at https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-14-854r.pdf.

83 Congressional Budget Office, Options for Reducing the Deficit, 2023 to 2032, Volume II; Smaller Reductions, December 7, 2022, at https://www.cbo.gov/budget-options/58654; https://www.cbo.gov/budget-options/56843.

84 Editorial Board, "Opinion; Veterans deserve support. But one benefit program deserves scrutiny," Washington Post, April 3, 2023, at https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/04/03/veterans-affairs-disability-payments-overdue-update/.

Congressional Research Service

19

Concurrent Receipt of Military Retired Pay and Veteran Disability

perform manual labor.85 Today, the proportion of jobs in professional, managerial, clerical, and other primarily desk-based jobs relative to manual labor jobs in the U.S. economy has increased, potentially shifting estimates of earnings capacity for those with physical disabilities.86

Some veteran advocacy groups have argued that VA payments compensate for unique disabilities associated with the physical and mental stress of military service that affect not only employment opportunities and earnings potential, but also quality of life.87 Congress may consider these arguments, in light of other fiscal and policy goals. 88

Modify Concurrent Receipt Normal Cost Responsibilities The FY2024 President’s budget request included $20.7 billion in mandatory funding for accrual payments for future concurrent receipt benefits—$10.1 billion (95%) more than the $10.6 billion budgeted for such payments in FY2023.89 The increase followed revised assumptions of the DOD Board of Actuaries (the Board) in 2022 to reflect higher Treasury Department costs for concurrent receipt accrual payments.90 In particular, the Board approved a normal cost percentage (NCP)—the share of a servicemember’s basic pay used to determine an actuarial value of retirement benefits to fund each year—of 28.3% for the Treasury Department to pay concurrent receipt costs in FY2024, up from a previous estimate of 16.1%.91 The Board cited several factors as contributing to increasing concurrent receipt costs, including more incentive among servicemembers to apply for the benefits, broader definitions of disability and higher disability ratings by the VA, and higher incidence of combat-related disability from recent conflicts.92 The Board also noted the recent passage of the Honoring Our PACT Act of 2022 (P.L. 117-168), which expands VA disability benefits related to burn pits and other toxic substances, could further increase these costs.93

85 Veteran's Benefits in the United States, A Report to the President by the President's Commission on Veterans' Pensions, April 1956, p. 39, at http://www.veteranslawlibrary.com/files/Commission_Reports/Bradley_Commission_Report1956.pdf.

86 Ian D. Wyatt and Daniel E. Hecker, Occupational changes during the 20th century, Bureau of Labor Statistics, March 2006, at https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2006/03/art3full.pdf.

87 “Opinion; Readers respond: Don’t touch veterans’ disability benefits,” Washington Post, April 6, 2023, at https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/04/06/veterans-disability-benefits-earned-compensation/; and “Opinion; This is the true cost of America’s wars,” Washington Post, April 10, 2023, at https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/04/10/true-cost-america-wars-veterans/.

88 For an example of prior study on this matter, see Beth J. Asch et al., Capping Retired Pay for Senior Field Grade Officers; Force Management, Retention, and Cost Effects, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, 2018, at https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2251.html.

89 OMB, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2024, Analytical Perspectives, Table 24-1, “Budget Authority and Outlays by Function, Category, and Program (PDF), March 13, 2023, at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BUDGET-2024-PER/pdf/BUDGET-2024-PER-6-1-1.pdf. These figures exclude additional concurrent receipt costs associated with unfunded liability payments.