Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations

Changes from December 20, 2019 to July 28, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- Corruption and Government Institutions

- Evolution of Efforts to Combat Criminal Groups over 14 years

- Congressional Concerns

- Crime Situation in Mexico

- Background on Drug Trafficking in Mexico

- Components of Mexico's Drug Supply Market

- Evolution of the Major Drug Trafficking Groups

- Nine Major DTOs

- Tijuana/Arellano Felix Organization

- Sinaloa DTO

- Juárez/Carrillo Fuentes Organization

- Gulf DTO

- Los Zetas

- Beltrán Leyva Organization

- La Familia Michoacana

- Knights Templar

- Cartel Jalisco-New Generation

- Fragmentation, Competition, and Diversification

- Outlook

Summary

Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking

July 28, 2020

Organizations

June S. Beittel

Mexican drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) pose the greatest crime threat to the United States

Analyst in Latin American

and have “and have "the greatest drug trafficking influence,"” according to the annual U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration's (DEA's)

Affairs

Administration’s (DEA’s) annual National Drug Threat Assessment. These organizations work across the Western Hemisphere and globally. They are involved in extensive money laundering, bribery, gun trafficking, and corruption, and they cause Mexico's homicide rates, often

referred to as transnational criminal organizations (TCOs), continue to diversify into crimes of extortion, human smuggling, and oil theft, among others. Their supply chains traverse the

Western Hemisphere and the globe. Their extensive violence since 2006 has caused Mexico’s homicide rate to spike. They produce and traffic illicit drugs into the United States, including heroin, methamphetamine, marijuana, and powerful synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, and they traffic South American cocaine. Over the past decade, Congress has held numerous hearings addressing violence in Mexico, U.S. counternarcotics assistance, and border security issues.

Mexican DTO activities significantly affect the security of both the United States and Mexico. As Mexico'’s DTOs expanded their control of the opioids market, U.S. overdoses rose sharply according to the Centers for Disease Control, setting a record in 2019to a record level in 2017, with more than half of the 72,000 overdose deaths (47,000) involving opioids. Although preliminary 2018 data indicate a slight decline in overdose deaths, many analysts believe trafficking continues to evolve toward opioids. The major Mexican DTOs, also referred to as transnational criminal organizations (TCOs), have continued to diversify into such crimes as human smuggling and oil theft while increasing their lucrative business in opioid supply. According to the Mexican government's latest estimates, illegally siphoned oil from Mexico's state-owned oil company costs the government about $3 billion annually.

Mexico's DTOs have been in constant flux70% of overdose deaths involving opioids, including fentanyl. Many analysts believe that Mexican DTOs’ role in the trafficking and producing of opioids is continuing to expand.

Evolution of Mexico’s Criminal Environment Mexico’s DTOs have been in constant flux, and yet they continue to wield extensive political and criminal power. In 2006, four DTOs were dominant: the Tijuana/Arellano Felix organizationFélix Organization (AFO), the Sinaloa Cartel, the Juárez/Vicente Carillo Fuentes Organization (CFO), and the Gulf Cartel. Government operations to eliminate DTO leadership sparked organizational changes, whichthe cartel leadership increased instability among the groups andwhile sparking greater violence. Over the next dozen years, Mexico'’s large and comparatively more stable DTOs fragmented, creating at first seven major groups, and then nine, which are briefly described in this report. The DEA has identified those nine organizations as Sinaloa, Los Zetas, Tijuana/AFO, Juárez/CFO, Beltrán Leyva, Gulf, La Familia Michoacana, the Knights Templar, and Cartel Jalisco-New Generation Nuevo Generación (CJNG).

In mid-2019, the leader of the long-dominant Sinaloa Cartel, Joaquin ("Joaquín “El Chapo")” Guzmán, was sentenced to life in a maximum-security U.S. prison, spurring further fracturing of athe once-hegemonic DTO. In December 2019, Genaro García Luna, a former head of public security in the Felipe Calderón Administration (2006-2012), was arrested in the United States on charges he had taken enormous bribes from Sinaloa, further eroding public confidence in Mexican government efforts.

Since his inauguration in late 2018, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has implemented what some analysts contend is an ad hoc approach to security that has achieved little sustained progress. Despite reform promises, the president has relied on a conventional policy of using the military and a military-led national guard to help suppress violence. The president has targeted oil theft that siphons away billions in government revenue annually.

Recent Developments In 2019, Mexico’s national public security system reported more than 34,500 homicides, setting another record in absolute homicides and the highest national homicide rate since Mexico has published this data. In late 2019, several cartel fragments committed flagrant acts of violence, killing U.S.-Mexican citizens in some instances. Some Members of Congress questioned a U.S. policy of returning Central American migrants and others to await U.S. asylum proceedings in border cities, such as Tijuana, because these cities have reported among the highest urban homicide rates in the world. The Trump Administration also raised concerns over whether Mexican crime groups should be listed as terror organizations.

In June 2020, two high-level attacks on Mexican criminal justice authorities stunned Mexico, including an early morning assassination attempt targeting the capital’s police chief, allegedly by the CJNG. He survived the attack, but three others were killed in one of Mexico City’s most affluent neighborhoods. The other was the murder of a Mexican federal judge in Colima who had ruled in significant organized crime cases, including extradition of the CJNG’s top leader’s son to the United States.

once-hegemonic DTO.

By some accounts, a direct effect of this fragmentation has been escalated levels of violence. Mexico's intentional homicide rate reached new records in 2017 and 2018. In 2019, Mexico's national public security system reported more than 17,000 homicides between January and June, setting a new record. In the last months of 2019, several fragments of formerly cohesive cartels conducted flagrant acts of violence. For some Members of Congress, this situation has increased concern about a policy of returning Central American migrants to cities across the border in Mexico to await their U.S. asylum hearings in areas with some of Mexico's highest homicide rates.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, elected in a landslide in July 2018, campaigned on fighting corruption and finding new ways to combat crime, including the drug trade. According to some analysts, challenges for López Obrador since his inauguration include a persistently ad hoc approach to security; the absence of strategic and tactical intelligence concerning an increasingly fragmented, multipolar, and opaque criminal market; and endemic corruption of Mexico's judicial and law enforcement systems. In December 2019, Genero Garcia Luna, a former top security minister under the Felipe Calderón Administration (2006-2012), was arrested in the United States on charges he had taken enormous bribes from the Sinaloa Cartel, further eroding public confidence in government efforts.

For more background, see CRS Insight IN11205, Designating Mexican Drug Cartels as Foreign Terrorists: Policy Implications, CRS Report R45790, The Opioid Epidemic: Supply Control and Criminal Justice Policy—Frequently Asked Questions, and CRS Report R42917, Mexico: Background and U.S. Relations.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 4 link to page 7 link to page 9 link to page 12 link to page 14 link to page 16 link to page 19 link to page 19 link to page 20 link to page 22 link to page 23 link to page 24 link to page 25 link to page 27 link to page 28 link to page 29 link to page 30 link to page 31 link to page 32 link to page 5 link to page 8 link to page 12 link to page 18 link to page 34 link to page 37 Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations

Contents

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Congressional Concerns .................................................................................................................. 4 Escalation of DTO-Related Homicide, Corruption, and Impunity .................................................. 6

Corruption and Government Institutions ................................................................................... 9

Criminal Landscape in Mexico ...................................................................................................... 11

Illicit Drugs in Mexico and Components of Its Drug Supply Market ..................................... 13

Evolution of the Major Drug Trafficking Groups.......................................................................... 16

Nine Major DTOs.................................................................................................................... 16

Tijuana/Arellano Félix Organization ................................................................................ 17 Sinaloa DTO ..................................................................................................................... 19 Juárez/Carrillo Fuentes Organization ................................................................................ 20 Gulf DTO .......................................................................................................................... 21 Los Zetas ........................................................................................................................... 22 Beltrán Leyva Organization .............................................................................................. 24 La Familia Michoacana..................................................................................................... 25 Knights Templar ................................................................................................................ 26 Cártel Jalisco Nuevo Generación ...................................................................................... 27

Fragmentation, Competition, and Diversification ................................................................... 28

Outlook .......................................................................................................................................... 29

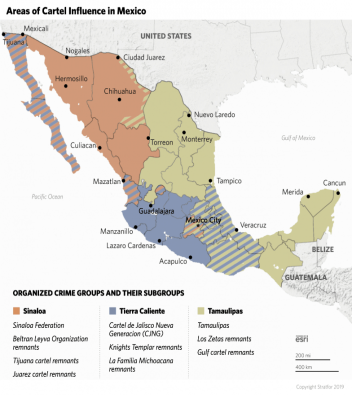

Figures Figure 1. Map of Mexico ................................................................................................................. 2 Figure 2. Stratfor Cartel Map by Region of Influence .................................................................... 5 Figure 3. Major Ports of Entry at the U.S.-Mexico Border ............................................................. 9 Figure 4. U.S. Customs and Border Patrol Seizures of Fentanyl and Methamphetamine ............. 15

Appendixes Appendix. Drug Trafficking in Mexico and Government Efforts to Combat the DTOs ............... 31

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 34

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations

Introduction Implications, CRS In Focus IF10578, Mexico: Evolution of the Mérida Initiative, 2007-2020, and CRS Report R42917, Mexico: Background and U.S. Relations. On the issues of fentanyl and heroin, see CRS Report R45790, The Opioid Epidemic: Supply Control and Criminal Justice Policy—Frequently Asked Questions.

Introduction

Mexico shares a nearly 2,000-mile border with the United States, and the two countries have historically close trade, cultural, and demographic ties. Mexico'’s stability is of critical importance to the United States, and the nature and intensity of violence in Mexico has been of particular concern to the U.S. Congress. Over the past decade, Congress has held numerous hearings addressing violence in Mexico, U.S. counternarcotics assistance, and border security issues.

According to one Mexican think tank that publishes an annual assessment, the top five cities in the world for violence in 2019 were in Mexico.1 Increasing violence, intimidation of Mexican politicians in advance of elections, and assassinations of journalists and media personnel have continued to raise alarm. From 2017 through 2019, a journalist was murdered nearly once a month on average, leading to Mexico’s status as one of the world’concern to the U.S. Congress. Increasing violence, intimidation of Mexican politicians in advance of the 2018 elections, and assassinations of journalists and media personnel have continued to raise alarm. In 2018, some 37 mayors, former mayors, or mayoral candidates were killed, and murders of nonelected public officials rose above 500.1 In 2017 and 2018, a journalist was murdered nearly once a month, leading to Mexico's status as one of the world's most dangerous countries to practice journalism.2 In the run-up to the 2018 local and national elections, some 37 mayors, former mayors, or mayoral candidates were killed, and murders of nonelected public officials rose above 500.3

Over many years, Mexico’s brutal drug-trafficking-related violence In 2019, press reports indicate that 12 journalists were assassinated in Mexico, in a year that appears to be on track for a new overall homicide record.2

Mexico's brutal drug trafficking-related violence over many years has been dramatically punctuated by beheadings, public hanging of corpses, car bombs, and murders of dozens of journalists and public officials. Beyond these brazen crimes, violenceofficials. Violence has spread from the border with the United States tointo Mexico's interior, flaring in the Pacific states of Michoacán and Guerrero and in the border states of Tamaulipas, Chihuahua, and Baja California, where Mexico's largest border cities are located. ’s interior. Organized crime groups have splintered and diversified their crime activities, turning to extortion, kidnapping, autooil theft, oilhuman smuggling, human smugglingsex trafficking, retail drug sales, and other illicit enterprises. These crimes often are described as more "parasitic"“parasitic” for local communities and populations inside Mexico, degrading a sense of citizen security. The violence has flared in the Pacific states of Michoacán and Guerrero, in the central states of Guanajuato and Colima, and in the border states of Tamaulipas, Chihuahua, and Baja California, where Mexico’s largest border cities are located (for map of Mexico, see Figure 1).

populations inside Mexico.

A spate of crimes between early October and December 2019 appear to have been committed by factions of formerly cohesive criminal groups. Those jarring incidents included

- The October capture by Mexican authorities of a son of imprisoned Mexican drug kingpin Joaquin ("El Chapo") Guzmán. Guzmán's son was briefly detained for trafficking, until the Sinaloa Cartel responded with overwhelming force that brought chaos to the city of Culiacan and prompted authorities to release him.

- The November 4 slaying of nine U.S.-Mexican dual citizens of an extended Mormon family (including children) in the border state of Sonora in Mexico.

- A shootout near the Texas-Mexico border in which some 21 people were killed over two days, including police, criminal group members, and civilians.

These incidents—described as massacres—drew the attention of President Trump, who pushed the Mexican government to invite greater assistance from the U.S. government to help Mexico win the drug war.3

Drug traffickers exercised significant territorial influence in parts of the country near drug production hubs and along drug- trafficking routes during the six-year administration of President Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-2018), much as they had under the previous president. Although homicide rates declined early in Peña Nieto'’s term, total homicides rose by 22% in 2016 and 23% in 2017, reaching a record level. In 2018, homicides in Mexico rose above 33,000, or for a national rate of 27 per 100,000 people. According to the U.S. Department of State, Mexico exceeded 34,500 intentional homicides in 2019 for a national rate of 29 per 100,000.4 Thus, for each of the most recent three years, records were set and then eclipsed.

1 El Consejo Ciudadano para la Seguridad Pública y la Justicia Penal (Citizen Council for Public Security and Criminal Justice), “Boletín Ranking 2019 de las 50 Ciudades más Violentas del Mundo,” June 1, 2020, http://www.seguridadjusticiaypaz.org.mx/sala-de-prensa/1590-boletin-ranking-2019-de-las-50-ciudades-mas-violentas-del-mundo. The survey found in 2019 the world’s top most violent cities (all in Mexico) were (1) Tijuana, (2) Ciudad Juárez, (3) Uruapan, (4) Irapuato, and (5) Ciudad Obregon.

2 For background on Mexico, see CRS Report R42917, Mexico: Background and U.S. Relations, by Clare Ribando Seelke. See also Juan Albarracín and Nicholas Barnes, “Criminal Violence in Latin America,” Latin American Research Review, vol. 55, no. 2 (June 23, 2020), pp. 397-406.

3 For more background, see Laura Y. Calderón et al., Organized Crime and Violence in Mexico, University of San Diego, April 2019. See also CRS Report R45199, Violence Against Journalists in Mexico: In Brief, by Clare Ribando Seelke.

4 Testimony of Richard Glenn, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, before the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere, Civilian Security, and Trade, for a hearing on “Assessing U.S. Security Assistance to Mexico,” February 13, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

1

Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations

Figure 1. Map of Mexico

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS).

rate of 27 per 100,000 people, about a 33% increase over the record set in 2017.4

Yet, Mexico's high homicide rate is not exceptional in the region, where many countries are plagued by high rates of violent crime, such as the "Northern Triangle" countries of Central America—El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. Overall, the Latin America region has a significantly higher homicide level than other regions worldwide. According to the U.N.'s Global Study on Homicide published in July 2019, with 13% of the world's population in 2017, Latin America had 37% of the world's intentional homicides.5 Mexico's homicide rate was once about average for the region, but the country's intentional homicides and homicide rates have risen steadily in the past three years. (This increase contrasts with homicide-rate declines in the Northern Triangle countries, where high rates decreased somewhat between 2017 and 2018.)

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service. |

Even by the Latin American experience, the increases in Mexico's homicide rate and absolute number of homicides from 2007 to the end of the administration of President Felipe Calderón in 2012 were unprecedented.6 Estimates of Mexico's disappeared or missing—numbering 40,000 from 2006, as reported by the Mexican government in 2019, have generated domestic and international concern.7 Alarm has grown about new bouts of extreme violence, and the continuing discovery of mass graves around the country remains a troubling sign.8

Casualties are reported differently by the Mexican government and Mexican media outlets that track the violence, so debate exists on how many have been killed.9 This report conveys Mexican government data, but the data have not consistently been reported or reported completely. For example, the Mexican government released tallies of "organized-crime related" homicides through September 2011. For a time, the Peña Nieto administration also issued such estimates, but it stopped in mid-2013. Although precise tallies diverged, during President Calderón's tenure (2006-2012) there was a sharp increase in the number of homicides, which leveled off at the end of 2012. In the Peña Nieto administration, after a couple years' decline, a sharp increase was recorded between 2016 and the first half of 2019, which surpassed previous totals. Overall, since 2006, many sources maintain that Mexico experienced roughly 150,000 murders related to organized crime, which is about 30% to 50% of total intentional homicides.10 In addition, the government assesses more than 40,000 Mexicans disappeared, as mentioned above.

Violence is an intrinsic feature of the trade in illicit drugs. Traffickers use it to settle disputes, and a credible threat of violence maintains employee discipline and provides a semblance of order with suppliers, creditors, and buyers, while also serving to intimidate potential competitors.115 This type of drug -trafficking-related violence has occurred routinely and intermittently in U.S. cities since the early 1980s. The violence now associated with drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) in Mexico is of an entirely different scale. In Mexico, the violence is not only is associated with resolving disputes, maintaining discipline, and intimidating rivals but also has has also been directed toward the government, political candidates, and the media. Some observers note that the excesses of some of Mexico'some of Mexico’s violence might be considered exceptional by the typical standards of organized crime.12 6 Periodically, when organized -crime-related homicides in Mexico have spread tobreak out in important urban centers or resultedresult in the murder of U.S. citizens, Members of Congress have considered the possibility of designating the criminal groups as foreign terrorists, as in late 2019.7 However, the 2019.13 The DTOs appear to lack a discernible political goal or ideology, which is one element of a widely recognized definition of terrorism.

Corruption and Government Institutions

The criminal involvement of state governors with the DTOs and other criminals reflects the extent of corruption into the layers of government and across parties in Mexico.14 Twenty former state governors, many from the long-dominant Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), were under investigation or in jail in 2018.15 Over the six years of PRI President Peña Nieto's term (2012-2018), Mexico fell 32 places in Transparency International's Corruption Perception Index.16

Noteworthy examples of corrupt former governors include

- Veracruz Governor Javier Duarte (2010-2016) of the PRI, arrested in Guatemala and extradited to Mexico in August 2017. During his term, the number of persons forcibly disappeared in Veracruz is estimated to exceed 5,000.17 Following his trial, Duarte received a nine-year sentence in September 2018.

- Roberto Borge of Quintana Roo (2010-2016), of the PRI, wanted on charges of corruption and abuse of public office, was extradited by Panama to Mexico in June 2018.18

- Tomás Yarrington of Tamaulipas (1999-2005), also of the PRI, was arrested in Italy in 2017 and extradited to the United States in 2018 for U.S. charges of drug trafficking, money laundering, and other corruption. Since 2012, he has been under investigation for his links to the Gulf Cartel and the Zetas in Mexico.19

- César Duarte of Chihuahua (2010-2016), also of the PRI, has fled Mexico and is an international fugitive wanted on a Red Notice by the International Criminal Police Organization Interpol.20

In an unexpected development, Genaro Garcia Luna, a former high-ranking security official, was arrested in Texas in December 2019 on charges of having taken multimillion-dollar bribes from the Sinaloa Cartel. Garcia Luna, who had headed Mexico's Federal Investigation Agency from 2001 to 2005 (under former President Vicente Fox of the National Action Party, or PAN) and then was the country's Secretary of Public Security (under President Calderón, also of PAN), left Mexico in 2012 had been seeking to become a naturalized U.S. citizen. President Lopez-Obrador hailed Garcia Luna's arrest as evidence that the Calderón government's fierce enforcement strategy had not successfully repelled the cartels.21

Evolution of Efforts to Combat Criminal Groups over 14 Years

Former President Calderón made an aggressive campaign against criminal groups, especially the large DTOs, the central focus of his administration's policy. He sent several thousand Mexican military troops and federal police to combat the organizations in drug trafficking "hot spots" around the country. His government made some dramatic and well-publicized arrests, but few of those captured kingpins were convicted. Between 2007 and 2012, as part of much closer U.S.-Mexican security cooperation, the Mexican government significantly increased extraditions to the United States, with a majority of the suspects wanted by the U.S. government on drug trafficking and related charges. The number of extraditions peaked in 2012 but remained steady during President Peña Nieto's term (although have tapered off under the current president). Another result of the "militarized" strategy used in successive Mexican administrations was an increase in accusations of human rights violations against the Mexican military, which was largely untrained in domestic policing.

Several observers have noted the severe human rights violations involving Mexican military and police forces, which, at times, reportedly have colluded with Mexico's criminal groups. According to a press investigation of published Mexican government statistics, Mexican armed forces injured or killed some 3,900 individuals in their domestic operations between 2007 and 2014 and labeled victims as civilian aggressors.22 According to the report, the government data do not clarify the causes for a high death rate (about 500 were injuries and the rest killings) or specify which of the military's victims were armed and which were bystanders. (Significantly, the military's role in injuries and killings was no longer made public after 2014 according to the account.23)

President Peña Nieto pledged he would take a new direction in his security policy that would focus on reducing criminal violence that affects civilians and businesses and be less oriented toward removing the leaders of the large DTOs. Ultimately, that promise was not met. His then-attorney general, Jesus Murillo Karam, said in 2012 that Mexico faced challenges from some 60 to 80 crime groups operating in the country whose proliferation he attributed to the predecessor Calderón government's kingpin strategy.24 However, despite Peña Nieto's stated commitment to shift the government's approach, analysts found considerable continuity between the approaches of Peña Nieto and Calderón.25 The Peña Nieto government recentralized control over security and continued to use a strategy of taking down the top drug kingpins, adopting the same list of top trafficker targets while adapting it over the years. Significantly, the long process of fragmentation has continued to splinter Mexico's criminal groups.26

President Peña Nieto continued cooperation with the United States under the Mérida Initiative, which began during President Calderón's term. The Mérida Initiative, a bilateral anticrime assistance package launched in 2008, initially focused on providing Mexico with hardware, such as planes, scanners, and other equipment, to combat the DTOs. The $3 billion effort (through 2018) shifted in recent years to focus on training and technical assistance for the police and enactment of judicial reform, including training at the local and state levels, southern border enhancements, and crime prevention. After some reorganization of bilateral cooperation efforts, the Peña Nieto government continued the Mérida programs. Peña Nieto's focus on crime prevention, which received significant attention early in his term, eventually was ended due to budget cutbacks.27

On December 1, 2018, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the populist leftist leader of the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA) party, took office for a six-year term after winning 53% of the vote in July elections. The new president pledged to make Mexico a more just and peaceful society, but he also vowed to govern with austerity. López Obrador aims to build infrastructure in southern Mexico, revive the state oil company, and promote social programs.28 Given fiscal constraints and rising insecurity, observers question whether his goals are attainable.29

President López Obrador has backed constitutional reforms to allow military involvement in public security to continue for five more years, despite a 2018 Supreme Court ruling that prolonged military involvement in security violated the constitution. He secured congressional approval to stand up a new 80,000-strong National Guard (composed of military police, federal police, and new recruits) to combat crime. This action surprised many in the human rights community, who succeeded in persuading Mexico's Congress to modify López Obrador's original proposal to ensure the National Guard will be under civilian command. The first assignment for about 20,000 members of the newly composed force involved more vigorous migration enforcement to comply with Trump Administration demands. López Obrador also created a presidential commission to coordinate efforts to investigate an unresolved case from 2014 in which 43 youth in Guerrero state are alleged to have been murdered by a drug cartel.

At the end of his first year in office, President Lopez Obrador has remained popular, although his denials that homicide levels have continued to increase and his criticism of the press for not providing more positive coverage have raised concerns. Some analysts question his commitment to combat corruption and refocus efforts to curb Mexico's crime-related violence. During his presidential campaign, Lopez Obrador said he would consider unconventional approaches, such as legalization of some drugs.30 However, a significant security policy to combat the DTOs, beyond adopting an approach to deter vulnerable youth from crime and a commitment to stop fighting the organizations' violence with violence (or "fire with fire"), has yet to be articulated.

Congressional Concerns

Over the past decade, Congress has held numerous oversight hearings addressing the violence in Mexico, U.S. counternarcotics assistance, and border security issues. Congressional concern increased in 2012, after U.S. consulate staff and security personnel working in Mexico came under attack.31 (Two U.S. officials traveling in an embassy vehicle were wounded in an attack allegedly abetted by corrupt Mexican police.32) Occasional use of car bombs, grenades, and rocket-propelled grenade launchers—such as the one used to bring down a Mexican army helicopter in 2015—continue to raise concerns that some Mexican drug traffickers may be adopting insurgent or terrorist techniques.

Perceived harms to the United States from the DTOs, or transnational criminal organizations (TCOs), as the U.S. Department of Justice now identifies them, are due in large part to the organizations' control of and efforts to move illicit drugs and to expand aggressively into the heroin (or plant-based) and synthetic opioids market. Mexico experienced a sharp increase in opium poppy cultivation between 2014 and 2018, and increasingly Mexico has become a transit country for powerful synthetic opioids. This corresponds to an epidemic of opioid-related deaths in the United States, which continues to increase demand for both heroin and synthetic opioids. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, of the 72,000 Americans who died of drug overdoses in 2017, nearly 28,500 involved fentanyl or a similar analog of the synthetic drug—45% more than in 2016.33 Meanwhile, in Mexico, attacks on political candidates and sitting officials in the 2018 electoral season caused several candidates to withdraw from their races to avoid violence to themselves or their staffs and families. This overt political intimidation poses another concerning threat to democracy in Mexico.34 Crime linked to extortion, forced disappearances, and violent robbery have increased, while crime groups have diversified their activities.35

The U.S. Congress has expressed concern over the violence and has sought to provide oversight on U.S.-Mexican security cooperation. The 116th Congress may continue to evaluate how the Mexican government is combating the illicit drug trade, working to reduce related violence, and monitoring the effects of drug trafficking and violence challenges on the security of both the United States and Mexico. In March 2017, the U.S. Senate passed S.Res. 83 in support of both Mexico and China and their efforts to achieve reductions in fentanyl production and trafficking.

Crime Situation in Mexico

The splintering of the large DTOs into competing factions and gangs of different sizes began in 2017 and continues today. The development of these different crime groups, ranging from TCOs to small local mafias with certain trafficking or other crime specialties, has made the crime situation even more diffuse and the groups' criminal behavior harder to eradicate.

The older, large DTOs tended to be hierarchical, often bound by familial ties and led by hard-to-capture cartel kingpins. They have been replaced by flatter, more nimble organizations that tend to be loosely networked. Far more common in the present crime group formation is the outsourcing of certain aspects of trafficking. The various smaller organizations resist the imposition of norms to limit violence. The growth of rivalries among a greater number of organized crime "players" has produced continued violence, albeit in some cases these players are "less able to threaten the state and less endowed with impunity."36 However, the larger organizations (Sinaloa, for example) that have adopted a cellular structure still have attempted to protect their leadership, as in the 2015 escape orchestrated for Sinaloa leader "El Chapo" Guzmán through a mile-long tunnel from a maximum-security Mexican prison.

The scope of the violence generated by Mexican crime groups has been difficult to measure due to restricted reporting by the government and attempts by crime groups to mislead the public. The criminal actors sometimes publicize their crimes in garish displays intended to intimidate their rivals, the public, or security forces, or they publicize the criminal acts of violence on the internet. Conversely, the DTOs may seek to mask their crimes by indicating that other actors or cartels, such as a competitor, are responsible. Some shoot-outs are not reported as a result of media self-censorship or because the bodies disappear;37 one example is the reported death of a leader of the Knights Templar, Nazario Moreno Gonzalez, who was reported dead in 2010, but no body was recovered. Rumors of his survival persisted and were confirmed in 2014, when he was killed in a gun battle with Mexican security forces.38 (See "Knights Templar," below.)

Forced disappearances in Mexico also have become a growing concern, and efforts to accurately count the missing or forcibly disappeared have been limited, a problem that is exacerbated by underreporting. Government estimates of the number of disappeared people in Mexico have varied over time, especially of those who are missing due to force and possible homicide. In the Gulf Coast state of Veracruz, in 2017, a vast mass grave was unearthed containing some 250 skulls and other remains, some of which were found to be years old.39 Journalist watchdog group Animal Politico, which focuses on combating corruption with transparency, concluded in a 2018 investigative article that combating impunity and tracking missing persons cannot be handled in several states because 20 of Mexico's 31 states lack the biological databases needed to identify unclaimed bodies. Additionally, 21 states lack access to the national munitions database used to trace bullets and weapons.40

According to the Swiss-based Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, about 380,000 people were forcibly displaced in Mexico between 2009 and 2018, as a result of violence and organized crime. Some Mexican government authorities have said the number may exceed 1 million, but the definition of the causes of displacement is broad in such a count and includes anyone who moved due to violence. Dislocated Mexicans often cite clashes between armed groups, with Mexican security forces, intergang violence, and fear of future violence as reasons for leaving their homes and communities.41

Background on Drug Trafficking in Mexico

DTOs have operated in Mexico for more than a century. The DTOs can be described as global businesses with forward and backward linkages for managing supply and distribution in many countries. As businesses, they are concerned with bringing their product to market in the most efficient way to maximize their profits.

Mexican DTOs are the major wholesalers of illegal drugs in the United States and are increasingly gaining control of U.S. retail-level distribution through alliances with U.S. gangs. Their operations, however, are markedly less violent in the United States than in Mexico, despite their reportedly broad presence in many U.S. jurisdictions.

The DTOs use bribery and violence as complementary tactics. Violence is used to discipline employees, enforce transactions, limit the entry of competitors, and coerce. Bribery and corruption help to neutralize government action against the DTOs, ensure impunity, and facilitate smooth operations. The proceeds of drug sales (either laundered or as cash smuggled back to Mexico) are used in part to corrupt U.S. and Mexican border officials,42 Mexican law enforcement, security forces, and public officials either to ignore DTO activities or to actively support and protect DTOs. Mexican DTOs advance their operations through widespread corruption; when corruption fails to achieve cooperation and acquiescence, violence is the ready alternative.

The relationship of Mexico's drug traffickers to the government and to one another is a rapidly evolving picture, and any current snapshot (such as the one provided in this report) must be continually adjusted. In the early 20th century, Mexico was a source of marijuana and heroin trafficked to the United States, and by the 1940s, Mexican drug smugglers were notorious in the United States. The growth and entrenchment of Mexico's drug trafficking networks occurred during a period of one-party rule in Mexico by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which governed for 71 years. During that period, the government was centralized and hierarchical, and, to a large degree, it tolerated and protected some drug production and trafficking in certain regions of the country, even though the PRI government did not generally tolerate crime.43

Mexico is a longtime recipient of U.S. counterdrug assistance, but cooperation was limited between the mid-1980s and mid-2000s due to U.S. distrust of Mexican officials and Mexican sensitivity about U.S. involvement in the country's internal affairs. Numerous accounts maintain that for many years the Mexican government pursued an overall policy of accommodation. Under this system, arrests and eradication of drug crops took place, but due to the effects of widespread corruption the system was "characterized by a working relationship between Mexican authorities and drug lords" through the 1990s.44

The system's stability began to fray in the 1990s, as Mexican political power decentralized and the push toward democratic pluralism began, first at the local level and then nationally with the election of PAN candidate Vicente Fox as president in 2000.45 The process of democratization upended the equilibrium that had developed between state actors (such as the Federal Security Directorate, which oversaw domestic security from 1947 to 1985) and organized crime. No longer were certain officials able to ensure the impunity of drug traffickers to the same degree and to regulate competition among Mexican DTOs for drug trafficking routes, or plazas. To a large extent, DTO violence directed at the government appears to be an attempt to reestablish impunity, while the inter-cartel violence seems to be an attempt to reestablish dominance over specific drug trafficking plazas. The intra-DTO violence (or violence inside the organizations) reflects a reaction to suspected betrayals and the competition to succeed killed or arrested leaders.

Links Between Crime Groups and Mexican Law Enforcement, and Other High-Ranking Officials According to an April 2019 report of the University of San Diego's Justice in Mexico project, "The ability of organized crime groups to thrive hinges critically on the acquiescence, protection, and even active involvement of corrupt government officials, as well as corrupt private sector elites, who share the benefits of illicit economic activities."46

When |

Before this political development, an important transition of Mexico's role in the international drug trade took place during the 1980s and early 1990s. As Colombian DTOs were forcibly broken up, Mexican traffickers gradually took over the highly profitable traffic in cocaine to the United States. Intense U.S. government enforcement efforts led to the shutdown of the traditional trafficking route used by the Colombians through the Caribbean. As Colombian DTOs lost this route, they increasingly subcontracted the trafficking of cocaine produced in the Andean region to the Mexican DTOs, which they paid in cocaine rather than cash. These already-strong Mexican organizations gradually took over the cocaine trafficking business, evolving from being mere couriers for the Colombians to being the wholesalers they are today.

As Mexico's DTOs rose to dominate the U.S. drug markets in the 1990s, the business became even more lucrative. This shift raised the stakes, which encouraged the use of violence in Mexico to protect and promote market share. The violent struggle among DTOs over strategic routes and warehouses where drugs are consolidated before entering the United States reflects these higher stakes. Today, the major Mexican DTOs are poly-drug, handling more than one type of drug, although they may specialize in the production or trafficking of specific products. According to the U.S. State Department's 2019’s 2020 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR)), Mexico is a significant source and transit country for heroin, marijuana, and synthetic drugs (such as methamphetamine and to a lesser degree fentanylfentanyl) destined for the United States. Mexico remains the main trafficking route for U.S.-bound cocaine from the major supply countries of Colombia and (to a lesser extent) Peru and Bolivia.53 The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) notes that traffickers and retail sellers of fentanyl and heroin combine them in various ways, such as pressing the combined powder drugs into highly addictive and extremely powerful counterfeit pills.

destined for the United States.

The extent of Mexico's role in production of the synthetic opioid fentanyl, which is 30 to 50 times more potent than heroin, is less known, although Mexico's role in fentanyl trafficking is increasingly well documented.49 Mexico remains the main trafficking route for U.S.-bound cocaine from the major supply countries of Colombia and (to a lesser extent) Peru and Bolivia.50 The west coast state of Sinaloa, with its long coastline and difficult-to-access areas, is favorable for drug cultivation and remains the heartland of Mexico'’s drug trade. Marijuana and opium poppy cultivation has flourished in the state for decades.5154 It has also been the sourcehome of Mexico's ’s most notorious and successful drug traffickers.

Components of Mexico's Drug Supply Market

Cocaine.

Cocaine. Cocaine of Colombian origin supplies most of the U.S. market, and most of that supply is trafficked through Mexico, with. Mexican drug traffickers are the primary wholesalers of cocaine to the United States. According to the State Department's 2019 INCSR published in March 2019U.S. cocaine. According to the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), coca cultivation and cocaine production in Colombia rose sharply, with the U.S. government estimating that Colombia producedincreased to a record 921951 metric tons of pure cocaine in 2019, an 8% rise over 2018.55 Cutting cocaine with synthetic opioids (often unbeknownst to users) has become more commonplace and increases the dangers of overdose.

cocaine in 2017.52 For 2018, the U.S. government reported that Colombia's coca cultivation dropped slightly to 208,000 hectares and its potential cocaine production declined to an estimated 887 metric tons.53

Heroin and Synthetically Produced Opioids. In its 2018Heroin and Synthetically Produced Opioids. In its 2019 National Drug Threat Assessment (NDTA), the DEA warns that Mexico’s crime organizations, aided by corruption and impunity, (NDTA), the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) warns that Mexican TCOs present an acute threat to U.S. communities given their dominance in heroin and fentanyl exports. In Mexico, the drug traffickers have driven up the homicide and extortion rates and led to a rising homicide rate in recent years, projected to climb to 29 homicides per 100,000 individuals in 2019, based on current estimates.54 Mexico's heroin traffickers, who traditionally provided black or brown heroin to U.S. cities west of the Mississippi, began in 2012 and 2013 to innovate and changed their opium processing methods to produce white heroin, a purer and more potent product, which they trafficked mainly to the U.S. East Coast and Midwest. DEA seizure data determined in 2017 that 91% of heroin consumed in the United States was sourced to Mexico, and the agency maintains that no other crime groupsMexico’s heroin traffickers, who traditionally provided black or brown heroin to the western part of the United States, in 2012 and 2013 began to change their opium processing methods to 51 U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, Mexico Travel Advisory, June 17, 2020, https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/traveladvisories/traveladvisories/mexico-travel-advisory.html.

52 Juan Arvizo, “Crimen Displazó a 380 Mil Personas,” El Universal, July 24, 2019. See also Parker Asmann, “Is the Impact of Violence in Mexico Similar to War Zones?,” InSight Crime, October 23, 2017. 53 U.S. State Department, International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, March 2020. 54 The region where Sinaloa comes together with the states of Chihuahua and Durango is a drug-growing area sometimes called Mexico’s “Golden Triangle” after the productive area of Southeast Asia by the same name. In this region, a third of the population is estimated to make their living from the illicit drug trade.

55 White House, ONDCP, “United States and Colombian Officials Set Bilaeral Agenda to Reduce Cocaine Supply,” press release, March 5, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

13

link to page 18 Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations

produce white heroin, a purer and more potent product. The DEA maintains that no other crime groups, foreign or domestic, have a comparable reach to distribute within the United States.56

According to the ONDCP, 41,800 hectares of opium poppy were cultivated in Mexico in 2018—down 5% compared to 2017 but up 280% since 2013. Mexico’s potential production of pure heroin rose to 106 metric tons (MT) in 2018 from 26 MT in 2013.57 The DEA reports that 90% of U.S. seized heroin comes from Mexico, which is increasingly laced with fentanyl.

The extent of Mexico’s role in production of fentanyl, which is 30-50 times more potent than heroin, is less well understood than Mexico’s role in fentanyl trafficking, which is increasingly well documented.58 What is known is that seizures of fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and methamphetamine—the leading synthetic lab-produced drugs entering the U.S. illicit drug market—have been rising along the Southwest border. (For U.S. Customs and Border Protection seizure data, see Figure 4.)

Illicit imports of fentanyl from Mexico involve Chinese-produced fentanyl or fentanyl precursors coming most often from China. Many analysts contend have a comparable reach to distribute within the United States.55

According to the 2019 INCSR and the U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy, Mexico has cultivated an increasing amount of opium poppy. Mexico cultivated an estimated 32,000 hectares (ha) in 2016, 44,100 ha in 2017, and 41,800 ha in 2018. The U.S. government estimated that Mexico's potential production of heroin rose to 106 metric tons in 2018 from 26 metric tons in 2013, suggesting Mexican-sourced heroin is likely to remain dominant in the U.S. market.56 Some analysts believe, however, that plant-sourced drugs, such as heroin and morphine, are going to be increasinglymay be gradually replaced in the criminal market by synthetic drugs. If that happens, it is possibleIn the first half of 2019, according to the State Department, Mexico seized 157.3 kilograms of fentanyl, a 94% increase over the same time period in 2018.59 Some observers suggest that if synthetic drugs continue to expand their market share, the drug cartel structure that has relied upon control of opium production, heroin manufacture, and the distribution channels ofdistribution using the plaza system in Mexico and the criminal distribution systemfor trafficking drugs for sale inside the United States may be transformed. Simultaneously, poor Mexican farmers who cultivate opium to produce heroin maycould be disrupted. Synthetic drug trafficking with distribution arranged over the internet via the Dark Web would replace it. Abandoning heroin for the cheaper-to-produce fentanyl might cause Mexican opium farmers to be thrown out of work.60

56 ONDCP, “New Annual Data Released by White House Office of National Drug Control Policy Shows Poppy Cultivation and Potential Heroin Production Remain at Record-High Levels in Mexico,” press release, June 14, 2019.

57 For background on Mexico’s heroin and fentanyl exports, see CRS In Focus IF10400, Trends in Mexican Opioid Trafficking and Implications for U.S.-Mexico Security Cooperation, by Liana W. Rosen and Clare Ribando Seelke.

58 DEA, 2017 National Drug Threat Assessment, DEA-DCT-DIR-040-1, October 2017. See also Steven Dudley, “The End of the Big Cartels: Why There Won’t Be Another El Chapo,” InSight Crime, March 18, 2019. 59 U.S. State Department, International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, March 2020. 60 For sources of the concepts here, see Dudley, “The End of the Big Cartels;” testimony of Bryce Pardo, RAND Corporation, to House Homeland Security on Intelligence and Counterterrorism Subcommittee and Border Security, Facilitation, and Operations Hearing, “Homeland Security Implications of the Opioid Crisis,” July 25, 2019; Vanda Felbab-Brown, “Fending Off Fentanyl and Hunting Down Heroin: Controlling Opioid Supply from Mexico,” Brookings Institution, July 2020.

Congressional Research Service

14

link to page 18 Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations

Figure 4. U.S. Customs and Border Patrol Seizures of Fentanyl and

Methamphetamine

Data from FY2014-FY2019

Fentanyl

Methamphetamine

3,000

Number of Seizures in Pounds (lbs)

80,000

2,250

60,000

1,500

40,000

750

20,000

0

0

FY14 FY15 FY16 FY17 FY18 FY19

FY14 FY15 FY16 FY17 FY18 FY19

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Office of Field Operations’ Nationwide Drug Seizures and U.S. Border Patrol’s Nationwide Seizures, https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/cbp-enforcement-statistics. Notes: Prepared by CRS Graphics.

However, the economic devastation of the coronavirus pandemic, projected by the International Monetary Fund to reduce economic growth in Mexico by more than 10% in 2020 (estimated as of June 2020), may temporarily push former opium growers back into cultivation. The medium- and longer-term impact of the pandemic and coming recession on drug markets and consumer demand remains unknown.61

of work.57

Illicit imports of fentanyl from Mexico involve Chinese fentanyl or fentanyl precursors coming most often from China. In addition, these traffickers adulterate fentanyl imported from China and smuggle it into the United States. Some reporters maintain in their contacts with traffickers who "cook" fentanyl in laboratories that these cartel cooks are not mixing their product with heroin any longer. These reporters contend that DTOs trafficking heroin are deemphasizing heroin-fentanyl combinations and sending pure fentanyl to the United States or primarily fentanyl-based products, such as counterfeit pills.58

Cannabis. In 2017, Mexico seized 421 metric tons of marijuana and eradicated more than 4,230 hectares of marijuana, according to the State Department's 2019 INCSR. However, some analysts foresee a decline in U.S. demand for Mexican marijuana because drugs "other than marijuana" will likely become dominant in the future. This projection relates to more marijuana being grown legally in several states in the United States and Canada, which have either legalized cannabis or made it legal for medical purposes, thus decreasing its value as part of Mexican trafficking organizations' profit portfolio.

Methamphetamine. Mexican-produced methamphetamine has overtaken U.S. sources of the drug and expanded into nontraditional methamphetamine markets inside the United States, allowing Mexican traffickers to control the wholesale market inside the United States, according to the DEA. The expansion of methamphetamine seizures inside Mexico, as reported by the annual INCSR, is significant. In 2017, Mexico seized some 11.3 metric tons of methamphetamine, but in 2018, as of AugustAs of August 2018, as reported in the 2019 INCSR, Mexican authorities had seized 130 metric tonsMT of methamphetamine, due in part to a large seizure of some 50 MT in Sinaloa.62 U.S. methamphetamine seizures significantly increased between 2014 and 2019, as shown in Figure 4. in part the result of an arrest and seizure of some 50 metric tons of the drug in Sinaloa.59 The purity and potency of methamphetamine has driven up overdose deaths in the United States, according to the 2018 NDTA. Most Mexican trafficking organizations include a portion of the methamphetamine business in their trafficking operations and collectively control the wholesale methamphetamine distribution system inside the United States.

Note on U.S.-Mexican Enforcement Cooperation. The Mexican government increased its eradication efforts of opium poppy and cannabis, targeting both plant-based drugs. According to the State Department's 2019 INCSR, U.S. government assistance helped to push back on the growing involvement of the Mexican criminal groups in heroin and fentanyl trafficking by providing drug interdiction equipment to destroy drug labs, equipment for poppy eradication, and equipment for maritime interdiction. The Mexican government seized 356 kilograms of heroin, and eradicated about 29,200 ha of opium poppy. Regarding clandestine drug laboratories, Mexico dismantled some 103 labs in 2017.60

Evolution of the Major Drug Trafficking Groups

.

Cannabis. In the first six months of 2019, Mexico seized 91 MT of marijuana and eradicated more than 2,250 hectares of marijuana, according to the State Department’s 2020 INCSR. 61 Many analysts have made observations about the near-term impacts of the pandemic, but there is a diversity of perspectives on the long term. See Parker Asmann, Chris Dalby and Seth Robbins, “Six Ways Coronavirus Is Impacting Organized Crime in the Americas,” InSight Crime, May 4, 2020; Ernst, “Mexican Criminal Groups See Covid-19 Crisis as Opportunity to Gain More Power;” Robert Muggah, “The Pandemic Has Triggered Dramatic Shifts in the Global Criminal Underworld,” Foreign Policy, May 8, 2020. 62 Arthur DeBruyne, “An Invisible Fentanyl Crisis Emerging on Mexico’s Northern Border,” Pacific Standard, February 6, 2019. See also “50 Tonnes of Meth Seized in Sinaloa; Estimated Value US $5 Billion,” Mexico New Daily, August 18, 2018; Mike La Susa, “Massive Mexico Methamphetamine Seizure Reflects Market Shifts,” InSight Crime, August 21, 2018.

Congressional Research Service

15

Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations

Authorities are projecting a continued decline in U.S. demand for Mexican marijuana because drugs “other than marijuana” will likely predominate. This is also the case due to legalized cannabis or medical cannabis in several U.S. states and Canada, reducing its value as part of Mexican trafficking organizations’ portfolio. Mexico is also considering cannabis legalization and regulation.

Evolution of the Major Drug Trafficking Groups The DTOs have been in constant flux in recent years.63The DTOs have been in constant flux in recent years.61 By some accounts, when President Calderón came to office in 2006, there were four dominant DTOs: the Tijuana/Arellano Felix Félix organization (AFO), the Sinaloa Cartel, the Juárez/Vicente Carillo Fuentes Organization (CFO), and the Gulf Cartel. Since then, the large, moreformerly stable organizations that existed in the earlier years of the Calderón administration have fractured into many more groups.

For several years, the U.S. Drug Enforcement AdministrationDEA identified the following seven organizations as dominant: Sinaloa, Los Zetas, Tijuana/AFO, Juárez/CFO, Beltrán Leyva, Gulf, and La Familia Michoacana. In some sense, these might be viewed as the "traditional"“traditional” DTOs. However, many analysts suggest that those 7 groups have fragmented to between 9 and as many as 20 major organizations. Today, fragmentation, or "balkanization," of the major crime groupsseven groups have fragmented. In the past decade, as fragmentation has produced many more criminal actors, it has been accompanied by many groups'’ diversification into other types of criminal activity, as noted earlier. The following section focuses on nine DTOsthe nine currently most prominent DTOs (about which the most information is readily available) and whose current status illuminates the fluidity of all the crime groups in Mexico as they face new challenges from competition and changing market dynamics.

Some analysts maintain there may be as many as 20 major organizations and more than 200 criminal groups overall.64

Nine Major DTOs Nine Major DTOs

Reconfiguration of the major DTOs—often called transnational criminal organizations, or TCOs,referred to as TCOs due to their diversification into other criminal businesses——preceded the intensive fragmentation that is commonexists today. The Gulf Cartel, based in northeastern Mexico, had a long history of dominance in terms ofdominant power and profits, with the height of its power in the early 2000s. However, the Gulf cartel'Cartel’s enforcers—Los Zetas, who were organized from highly trained Mexican military deserters—split to form a separate DTO and turned against their former employers, engaging in a hyper-violent competition for territory.

The well-established Sinaloa DTO, with roots in western Mexico, has fought brutally for increased control of routes through the border states of Chihuahua and Baja California, with the goal of remaining the dominant DTO in the country. Sinaloa has a more decentralized structure of loosely linked smaller organizations, which has been susceptible to conflict when units break away. Nevertheless, the decentralized structure has enabled it to be quite adaptable in the highly competitive and unstable environment that now prevails.62

65

Sinaloa survived the arrest of its billionaire founder Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzmán in 2014. The federal operation to capture and detain Guzmán, which gained support from U.S. intelligence, was viewed as a major victory for the Peña Nieto government. Initially the kingpin'’s arrest did not

63 See Patrick Corcoran, “How Mexico’s Underworld Became Violent,” InSight Crime, April 2, 2013. According to this article, constant organizational flux, which continues today, characterizes violence in Mexico.

64 Muggah, “The Pandemic Has Triggered Dramatic Shifts in the Global Criminal Underworld;” Esberg, “More Than Cartels.”

65 Oscar Becerra, “Traffic Report: Battling Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel,” Jane’s Information Group, May 7, 2010. The author describes the networked structure: “The Sinaloa Cartel is not a strictly vertical and hierarchical structure, but instead is a complex organization containing a number of semiautonomous groups.”

Congressional Research Service

16

Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations

s arrest did not spawn a visible power struggle within the DTO. His dramatic escape in July 2015 followed by his rearrestre-arrest in January 2016, however, raised speculation that his role in the Sinaloa Cartel might have become more as a figurehead, rather than a functional leader.

The Mexican government'’s decision to extradite Guzmán to the United States, carried out on January 19, 2017, appears to have led to violent competition from a competing cartel, the Cartel Jalisco-New Generation (CJNG), CJNG, which had split from Sinaloa in 2010. Over 2016 and the early months of 2017, CJNG'the CJNG’s quick rise and a possible power struggle inside of Sinaloa between El Chapo'’s sons and a successor to their father, a longtime associate known as "“El Licenciado,"” reportedly caused increasing violence.63

66

In the Pacific Southwest, La Familia Michoacana—a DTO once based in the state of Michoacán and influential in surrounding states—split apart in 2015. It eventually declined in importance as its successor, the Knights Templar, grew in prominence in the region known as the tierra calienteTierra Caliente of Michoácan, Guerrero, and in parts of neighboring states Colima and Jalisco. At the same time, the CJNG rose to prominence between 2013 and 2015 and is currently deemed by many analysts as Mexico’s largest and most dangerous DTO. Themany analysts to be the most dangerous and largest Mexican cartel. CJNG has thrived with the decline of the Knights Templar, which was targeted by the Mexican government.64

67 The CJNG has assassinated numerous public officials in an effort to intimidate the Mexican government.

Open-source research about the "traditional" DTOs,traditional DTOs and their successors mentioned above is more available than information about smaller factions. With as many as 200-400 criminal groups, it is hard to assess longevity or even do a census of which ones are major actors. Current information about the array of new regional and local crime groups, numbering more than 45 groups, is more difficult to assess. The once-coherent organizations and their successors are still operating, both in conflict with one another andand, at times, cooperatively.

Tijuana/Arellano FelixFélix Organization

The AFO is a regional "tollgate"“tollgate” organization that historically hashas historically controlled the drug smuggling route between Baja California (Mexico) to southern California.6568 It is based in the border city of Tijuana. One of the founders of modern Mexican DTOs, Miguel Angel FelixÁngel Félix Gallardo, a former police officer from Sinaloa, created a network that included the Arellano FelixFélix family and numerous other DTO leaders (such as Rafael Caro Quintero, Amado Carrillo Fuentes, and Joaquín "El Chapo"El Chapo Guzman). The seven "“Arellano Felix"Félix” brothers and four sisters inherited the AFO from their uncle, Miguel Angel FelixÁngel Félix Gallardo, after his arrest in 1989 for the murder of DEA Special Agent Enrique "Kiki" Camarena.66

“Kiki” Camarena.69

66 Anabel Hernández, “The Successor to El Chapo: Dámaso López Núñez,” InSight Crime, March 13, 2017. 67 Juan Montes and José de Córdoba, “Cartel Becomes Top Mexico Threat,” Wall Street Journal, July 9, 2020; Luis Alonso Pérez, “Mexico’s Jalisco Cartel—New Generation: From Extinction to World Domination,” InSight Crime and Animal Politico, December 26, 2016.

68 John Bailey, “Drug Trafficking Organizations and Democratic Governance,” in The Politics of Crime in Mexico: Democratic Governance in a Security Trap (Boulder: FirstForum Press, 2014), p. 121. Mexican political analyst Eduardo Guerrero-Gutiérrez of the Mexican firm Lantia Consulting defines a “toll-collector” cartel or DTO as one that derives much of the organization’s income from charging fees to other DTOs using its transportation points across the U.S.-Mexican border.

69 Special Agent Camarena was an undercover DEA agent working in Mexico who was kidnapped, tortured, and killed in 1985. The Guadalajara-based Félix Gallardo network broke up in the wake of the investigation of its role in the murder.

Congressional Research Service

17

Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations

The AFO was once one of the two dominant DTOs in Mexico, infamous for brutally controlling the drug trade in Tijuana in the 1990s and early 2000s.6770 The other was the Juárez DTO, also known as the Carrillo Fuentes Organization. The Mexican government and U.S. authorities took vigorous enforcement action against the AFO in the early years of the 2000s, with the arrests and killings of the five brothers involved in the drug trade—the last of whom was captured in 2008.

In 2008, Tijuana became one of the most violent cities in Mexico. That year, the AFO split into two competing factions when Eduardo Teodoro "“El Teo" Garcia” García Simental, an AFO lieutenant, broke from Fernando "“El Ingeniero" Sanchez” Sánchez Arellano (the nephew of the Arellano FelixFélix brothers who had taken over the management of the DTO). GarciaGarcía Simental formed another faction of the AFO, reportedly allied with the Sinaloa DTO.6871 Further contributing to the escalation in violence, other DTOs sought to gain control of the profitable Tijuana/Baja California-–San Diego/California plaza in the wake of the power vacuum left by the earlier arrests of the AFO'’s key leadership.

s key players.

Some observers believe that the 2010 arrest of GarciaGarcía Simental created a vacuum for the Sinaloa DTO to gain control of the Tijuana/San Diego smuggling corridor.6972 Despite its weakened state, the AFO appears to have maintained control of the plaza through an agreement made between SanchezSánchez Arellano and the Sinaloa DTO'’s leadership, with Sinaloa and other trafficking groups paying a fee to use the plaza.73

In 2013, the DEA identified Sánchezpaying a fee to use the plaza.70 Some analysts credit the relative peace in Tijuana to a law enforcement success, but it is unclear how large of a role policing strategy played.

In 2013, the DEA identified Sanchez Arellano as one of the six most influential traffickers in the region.7174 Following his arrest in 2014, however, SanchezSánchez Arellano'’s mother, Enedina Arellano FelixFélix, who was trained as an accountant, reportedly took over. It remains unclear if the AFO retains enough power through its own trafficking and other crimes to continue to operate as a tollgate cartel. Violence in Tijuana rose to more than 100 murders a month in late 2016, with the uptick in violence attributed to Sinaloa battling its new challenger, CJNG, according to some analyses.72 CJNG apparently hasthe CJNG.75 The CJNG has apparently taken an interest in both local drug trafficking inside Tijuana and cross-border trafficking into the United States. As in other parts of Mexico, the role of the newly powerful CJNG organization may determine the nature of the area'’s DTO configuration in coming years.73 76 Some analysts maintain that the resurgence of violence in Tijuana and the spiking homicide rate in the nearby state of Southern Baja California are linked to the CJNG forging an alliance with remnants of the AFO. In 2018As noted previously, Tijuana was the city with the highest number of homicides in the country in both 2018 and 2019.

70 Mark Stevenson, “Mexico Arrests Suspected Drug Trafficker Named in US Indictment,” Associated Press, October 24, 2013.

71 Steven Dudley, “Who Controls Tijuana?,” InSight Crime, May 3, 2011. Sánchez Arellano took control in 2006 after the arrest of his uncle, Javier Arellano Félix.

72 E. Eduardo Castillo and Elliot Spagat, “Mexico Arrests Leader of Tijuana Drug Cartel,” Associated Press, June 24, 2014.

73 “Mexico Security Memo: Torreon Leader Arrested, Violence in Tijuana,” Stratfor Worldview, April 24, 2013, http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/mexico-security-memo-torreon-leader-arrested-violence-tijuana#axzz37Bb5rDDg. In 2013, Nathan Jones at the Baker Institute for Public Policy asserted that the Sinaloa-AFO agreement allows those allied with the Sinaloa DTO, such as the CJNG, or otherwise not affiliated with Los Zetas to also use the plaza. For more information, see Nathan P. Jones, “Explaining the Slight Uptick in Violence in Tijuana,” Baker Institute, September 17, 2013, http://bakerinstitute.org/files/3825/.

74 Castillo and Spagat, “Mexico Arrests Leader.” 75 Christopher Woody, “Mexico Is Settling into a Violent Status Quo,” Houston Chronicle, March 21, 2017. 76 Sandra Dibble, “New Group Fuels Tijuana’s Increased Drug Violence,” San Diego Union-Tribune, February 13, 2016; Christopher Woody, “Tijuana’s Record Body Count Is a Sign That Cartel Warfare Is Returning to Mexico,” Business Insider, December 15, 2016.

Congressional Research Service

18

Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations

homicides in the country, with 2,246 homicides, or a homicide rate of 115 per 100,000, suggesting the violence that receded in 2012 has returned to the municipality.74

Sinaloa DTO

Sinaloa DTO

Sinaloa, described as Mexico'’s oldest and most established DTO, is comprised of a network of smaller organizations. In April 2009, then-President Barack Obama designated the notorious Sinaloa Cartel as a drug kingpin entity pursuant to the Kingpin Act.75 Often77 Frequently regarded as the most powerful drug trafficking syndicate in the Western Hemisphere, the Sinaloa Cartel was an expansive network at its apex;: Sinaloa leaders successfully corrupted public officials from the local to the national level inside Mexico and abroad to operate in some 50 countries. Traditionally one of Mexico'’s most prominent organizations, each of its major leaders was designated a kingpin in the early 2000s. At the top of the hierarchy was Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzmán, listed in 2001, ; Ismael Zambada Garcia ("García (“El Mayo"”), listed in 2002,; and Juan Jose "José “El Azul"” Esparragoza Moreno, listed in 2003.

By some estimates, Sinaloa had grown to control 40%-60% of Mexico'’s drug trade by 2012 and had annual earnings calculated to be as high as $3 billion.7678 The Sinaloa Cartel has long been identified by the DEA as the primary trafficker of drugs to the United States.7779 In 2008, a federation dominated by the Sinaloa Cartel (which included the Beltrán Leyva organizationOrganization and the Juárez DTO) broke apart, leading to a battle among the former partners that sparked the most violent period in recent Mexican history.

Since its 2009 kingpin designation of Sinaloa, the United States has attempted to dismantle Sinaloa'Sinaloa’s operations by targeting individuals and financial entities allied with the cartel. For example, in October 2010, the U.S. Department of the Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control identified Alejandro Flores Cacho, along with 12 businesses and 16 members of his financial and drug trafficking enterprise located throughout Mexico and Colombia, as collaborators with Sinaloa. (In August 2017, OFAC identifiedAugust 2017, the U.S. Department of Treasury, sanctioned the Flores DTO and its leader, RaulRaúl Flores Hernandez, as Kingpins.78)

Hernández, as kingpins.80

The Sinaloa Cartel'’s longtime most visible leader, "El Chapo" Guzmán, escaped twice from Mexican prisons in 2001 and again in 2015. The second escape in July 2015—after re-arrest the year prior, was a major embarrassment to the Peña Nieto administration, and that incident may have convinced the Mexican government to extradite the alleged kingpin rather than try him in Mexico after his recapture.

In January 2017, the Mexican government extradited Guzmán to the United States. He was indicted in New York District'’s federal court in Brooklyn and tried for four months, from November 2018 to February 2019. His lawyers maintained he was not the head of the Sinaloa enterprise and instead a "lieutenant" following orders.79enterprise.81 Nevertheless, he was convicted by a federal jury in February 2019 and sentenced by a U.S. district judge in July 2019 to a life term in prison, with the addition of 30 years, and ordered to pay $12.6 billion in forfeiture for being the principal leader of the Sinaloa Cartel and for 26 drug-related charges, including a murder conspiracy.80

After Guzman's trusted deputy "El Azul"82

77 At the same time, the President identified two other Mexican DTOs as Kingpins: La Familia Michoacana and Los Zetas. The Kingpin designation is one of two major programs by the U.S. Department of the Treasury imposing sanctions on drug traffickers. Congress enacted the program sanctioning individuals and entities globally in 1999.

78 From 2012 on, cartel leader El Chapo Guzmán was ranked in Forbes Magazine’s listing of self-made billionaires. 79 “Profile: Sinaloa Cartel,” InSight Crime, January 8, 2016. 80 U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Longtime Mexican Drug Kingpin Raul Flores Hernandez and His Vast Network: OFAC Kingpin Act Action Targets 22 Mexican Nations and 43 Entities in Mexico,” press release, August 9, 2017.

81 Alan Feuer, “El Chapo May Not Have Been Leader of Drug Cartel, Lawyers Say,” New York Times, June 26, 2018. 82 DEA, “Joaquín ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán, Sinaloa Cartel Leader, Sentenced to Life in Prison Plus 30 Years,” press release, July 17, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

19

Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations

After Guzmán’s trusted deputy El Azul Esparragoza Moreno was reported to have died in 2014, the head of the Sinaloa DTO was assumed to be Guzmán'’s partner, Ismael Zambada GarciaGarcía, alias "“El Mayo,"” who is thought to continue in that leadership role.8183 Sinaloa may operate with a more horizontal leadership structure than previously thought.8284 Sinaloa operatives control certain territories, making up a decentralized network of bosses who conduct business and violence through alliances with each other and local gangs. Local gangs throughout the region specialize in specific operations and are then contracted by the Sinaloa DTO network.8385 The shape of the cartel in the current criminal landscape is evolving, however, as Sinaloa'’s rivals eye a formidable drug empire built on the proceeds from trafficking South American cocaine, and locally sourced methamphetamine, marijuana, and heroin to the U.S. market.

For a former hegemon in the cartel landscape, the Sinaloa Cartel is now under pressure and its future remains unclear

The Sinaloa Cartel has appeared under a certain amount of pressure thus far in 2020. Some analysts warn that Sinaloa remains powerful given its dominance internationally and its infiltration of the upper reaches of the Mexican government. Other analysts maintain that Sinaloa is in decline, citing its breakup into factions and violence from inter- and intra-organizational tensions. The CJNG tensions. Cártel Jalisco Nueva Generación–CJNG–has evidently battled withagainst its former partner, Sinaloa, in a number of regions, and has been deemed by several authorities Mexico's new most powerful and expansive crime syndicate.

to be Mexico’s new most expansive cartel. Friction between the two factions of the Sinaloa organization intensified in May and June 2020, with violent infighting between a faction led by El Chapo’s children (known collectively as “Los Chapitos”) and those aligned with a faction under El Mayo.86

Juárez/Carrillo Fuentes Organization

Juárez/Carrillo Fuentes Organization

Based in the border city of Ciudad Juárez in the central northern state of Chihuahua, the once-powerful Juárez DTO controlled the smuggling corridor between Ciudad Juárez and El Paso, TX, in the 1980s and 1990s.8487 By some accounts, the Juárez DTO controlled at least half of all Mexican narcotics trafficking under the leadership of its founder, Amado Carrillo Fuentes. Vicente Carrillo Fuentes, Amado'’s brother, took over the leadership of the cartel when Amado died during plastic surgery in 1997 and reportedly led the Juárez organization until his arrest in October 2014.

In 2008, the Juárez DTO broke from the Sinaloa federation, with which it had been allied since 2002.8588 The ensuing rivalry between the Juárez DTO and the Sinaloa DTO helped to turn Ciudad Juárez into one of the most violent cities in the world. From 2008 to 2011, the Sinaloa DTO and the Juárez DTO fought a "“turf war,"” and Ciudad Juárez experienced a wave of violence with 83 Kyra Gurney, “Sinaloa Cartel Leader ‘El Azul’ Dead? ‘El Mayo’ Now in Control?,” InSight Crime, June 9, 2014. Juan José Esparragoza Moreno supposedly died of a heart attack while recovering from injuries sustained in a car accident.

84 Observers dispute the extent to which Guzmán made key strategic decisions for Sinaloa. Some maintain he was a figurehead whose arrest had little impact on Sinaloa’s functioning, as he ceded operational tasks to “El Mayo” and Esparragoza long before his arrest.

85 “Revelan Estructura y Enemigos de ‘El Chapo’,” Excélsior, March 26, 2014; Bailey, “Drug Trafficking Organizations and Democratic Governance,” p. 119.