The Opioid Epidemic: Supply Control and Criminal Justice Policy—Frequently Asked Questions

Over the last several years, lawmakers in the United States have responded to rising drug overdose deaths, which increased four-fold from 1999 to 2017, with a variety of legislation, hearings, and oversight activities. In 2017, more than 70,000 people died from drug overdoses, and approximately 68% of those deaths involved an opioid.

Many federal agencies are involved in domestic and foreign efforts to combat opioid abuse and the continuing increase in opioid related overdose deaths. A subset of those agencies confront the supply side (some may also confront the demand side) of the opioid epidemic. The primary federal agency involved in drug enforcement, including prescription opioids diversion control, is the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Other federal agencies that address the illicit opioid supply include, but are not limited to, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Offices of the U.S. Attorneys, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, U.S. Department of State, U.S. Postal Inspection Service, and Office of National Drug Control Policy. This report focuses on efforts from these departments and agencies only.

Lawmakers have addressed opioid abuse as both a public health and a criminal justice issue, and Congress enacted several new laws in the 114th and 115th Congresses. These include the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 (CARA; P.L. 114-198), the 21st Century Cures Act (Cures Act; P.L. 114-255), and most recently the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act (SUPPORT Act; P.L. 115-271). Congress also provided funds specifically to address the opioid epidemic in FY2017-FY2019 appropriations.

This report answers common supply and criminal justice-related questions that have arisen as drug overdose deaths in the United States continue to increase. It does not provide a comprehensive overview of opioid abuse as a criminal justice issue. The report is divided into the following sections:

Overview of the Opioid Epidemic in the United States;

Overview of the Opioid Supply;

Opioids and Domestic Supply Control Policy;

Opioids and Foreign Supply Control Policy;

Recent Congressional Action on the Opioid Epidemic; and

The Opioid Epidemic and State Criminal Justice Policies.

The Opioid Epidemic: Supply Control and Criminal Justice Policy—Frequently Asked Questions

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Overview of the Opioid Epidemic in the United States

- What is an opioid?

- How many Americans abuse opioids?

- What is the physical harm associated with opioid abuse?

- Which states are experiencing a high number and/or rate of overdose deaths?

- Overview of the Opioid Supply

- What is the recent history of the opioid supply in the United States?

- Prescription Opioid Supply

- Heroin Supply

- Fentanyl Supply

- Where are illicit opioids produced?

- How do illicit opioids enter the country?

- Prescription Opioids

- Heroin

- Illicitly Produced Fentanyl

- Opioids and Domestic Supply Control Policy

- How does the federal government counter illicit opioid trafficking in the United States?

- Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP)

- Department of Justice (DOJ)

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS)

- U.S. Postal Inspection Service (USPIS)

- What is the DEA's role in preventing the diversion of prescription opioids?

- Which DOJ grant programs may be used to address the opioid epidemic?

- Comprehensive Opioid Abuse Grant Program (COAP)

- COPS Anti-Heroin Task Force Program

- Drug Courts

- The Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) Program

- Justice and Mental Health Collaboration Program (JMHCP)

- Juvenile Justice Program Grants

- Residential Substance Abuse Treatment (RSAT) for State Prisoners Program

- Tribal Resources Grant Program

- Where can DOJ opioid-related grant funding information be found?

- Opioids and Foreign Supply Control Policy

- How does the United States respond to international illicit opioid trafficking?

- What has Mexico done to interrupt the flow of illicit opioids into the United States?

- What has China done to interrupt the flow of illicit opioids into the United States?

- Recent Congressional Action on the Opioid Epidemic

- What federal laws have been enacted recently that address the opioid epidemic?

- How much FY2019 funding has Congress provided DHS, DOJ, and ONDCP to address the opioid epidemic?

- Is there an estimate for how much DOJ and other departments spend on the opioid epidemic?

- The Opioid Epidemic and State Criminal Justice Policies

- How have different states adapted their justice systems to deal with the opioid crisis?

Figures

Summary

Over the last several years, lawmakers in the United States have responded to rising drug overdose deaths, which increased four-fold from 1999 to 2017, with a variety of legislation, hearings, and oversight activities. In 2017, more than 70,000 people died from drug overdoses, and approximately 68% of those deaths involved an opioid.

Many federal agencies are involved in domestic and foreign efforts to combat opioid abuse and the continuing increase in opioid related overdose deaths. A subset of those agencies confront the supply side (some may also confront the demand side) of the opioid epidemic. The primary federal agency involved in drug enforcement, including prescription opioids diversion control, is the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Other federal agencies that address the illicit opioid supply include, but are not limited to, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Offices of the U.S. Attorneys, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, U.S. Department of State, U.S. Postal Inspection Service, and Office of National Drug Control Policy. This report focuses on efforts from these departments and agencies only.

Lawmakers have addressed opioid abuse as both a public health and a criminal justice issue, and Congress enacted several new laws in the 114th and 115th Congresses. These include the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 (CARA; P.L. 114-198), the 21st Century Cures Act (Cures Act; P.L. 114-255), and most recently the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act (SUPPORT Act; P.L. 115-271). Congress also provided funds specifically to address the opioid epidemic in FY2017-FY2019 appropriations.

This report answers common supply and criminal justice-related questions that have arisen as drug overdose deaths in the United States continue to increase. It does not provide a comprehensive overview of opioid abuse as a criminal justice issue. The report is divided into the following sections:

- Overview of the Opioid Epidemic in the United States;

- Overview of the Opioid Supply;

- Opioids and Domestic Supply Control Policy;

- Opioids and Foreign Supply Control Policy;

- Recent Congressional Action on the Opioid Epidemic; and

- The Opioid Epidemic and State Criminal Justice Policies.

Over the last several years, the public and lawmakers in the United States have been alarmed over the increasing number of drug overdose deaths, most of which have involved opioids. Congress has responded to the issue through legislative activity, oversight, and funding, while the Administration has sought to reduce the supply and demand of illicit drugs through enforcement, prevention, and treatment.

This FAQ report answers questions about the opioid epidemic and federal efforts to control the supply of opioids. It does not provide a comprehensive overview of opioid abuse and the criminal justice response. Instead, it answers common questions that have arisen due to rising drug overdose deaths and the availability of illicit opioids in the United States.

Overview of the Opioid Epidemic in the United States

This section answers questions on the nature of the opioid epidemic in the United States. The answers provide background on the types of opioids that are being abused, the associated harm to the abusers of these substances, and the extent of the abuse.

What is an opioid?

|

Terminology: Opioids and Opiates In current usage, the term "opioids" refers to all drugs derived from the opium poppy or emulating the effects of opium-derived drugs. Technically, the term "opiates" refers to natural compounds found in the opium poppy, and "opioids" refers to synthetic compounds that emulate the effects of opiates. In either case, the drugs act on opioid receptors in the brain. This report relies on current usage of the term opioids, to include both natural and synthetic opioids. |

An opioid is a type of drug that, when ingested, binds to opioid receptors in the body—many of which control a person's pain1. While opioids are medically used to alleviate pain, some are abused by being used in a way other than prescribed (e.g., in greater quantity) or taken without a doctor's prescription.2 Many prescription pain medications, such as hydrocodone and fentanyl, are opioids, as are some illicit drugs, such as heroin.

How many Americans abuse opioids?

In its annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) does not ask questions about "opioids" specifically; rather, it asks respondents about their use of heroin and misuse of prescription pain relievers in two separate questions.3 In 2017, SAMHSA estimated that 11.4 million people misused an opioid at least once in the past year—this includes 11.1 million prescription pain reliever "misusers"4 and 886,000 heroin users.5

In 2017, SAMHSA also estimated that 3.2 million Americans ages 12 and older (1.2% of the population 12 and older) were current "misusers" of prescription pain relievers, and approximately 494,000 Americans ages 12 and older (0.2% of the population 12 and older) were current users6 of heroin.7

The University of Michigan administers an annual Monitoring the Future Survey8, which measures drug use behaviors among 8th, 10th, and 12th graders; college students; and young adults. In 2018, 3.4% of surveyed 12th graders9 were current users of "narcotics other than heroin", and 0.1% of surveyed 8th, 10th, and 12th graders were current users of heroin.10

What is the physical harm associated with opioid abuse?

For chronic and severe pain, opioids can improve the functioning of legitimate pain patients; however, there are short- and long-term physical risks of abusing opioids. For example, nonfatal overdoses have been associated with a number of health issues, including brain injury, pulmonary and respiratory problems, hypothermia, kidney and liver failure, seizures, and others.11 The most severe physical harm associated with opioid abuse is death due to overdose. Drug overdose deaths have increased four-fold from 16,849 in 1999 to 70,237 in 2017. Of the 70,237 overdose deaths, 47,600 (67.8%) involved opioids.12 The main driver of drug overdose deaths overall is synthetic opioids.13 Reports indicate that recent increases in overdose deaths are most likely driven by illicitly manufactured fentanyl.14

Aside from the harm associated with fatal and nonfatal opioid overdoses, addiction is a primary harm associated with opioids. Licit and illicit opioids are highly addictive.15 Addiction and general misuse of opioids have contributed to a series of public health, welfare, and social problems that have been widely discussed in public forums.16

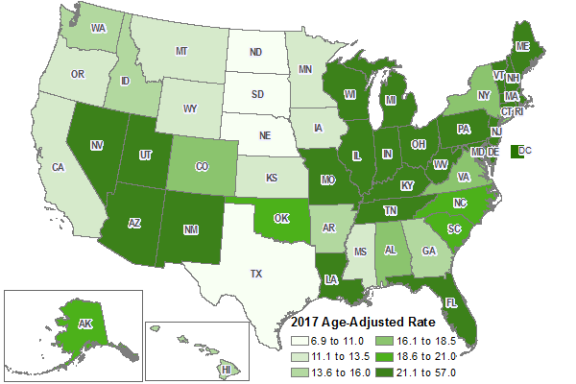

Which states are experiencing a high number and/or rate of overdose deaths?

The numbers and rates of drug overdose deaths vary by state and region of the United States. Table 1 shows the number of deaths and age-adjusted overdose death rates17 for each state and the national totals for 2017. As illustrated in Figure 1, the states east of the Mississippi River have comparatively higher rates of drug overdose deaths than states west of the Mississippi River, although New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah all rank in the top half of states for age-adjusted rates of drug overdose deaths.

Table 1. Total Numbers and Age-Adjusted Rates of Drug Overdose Deaths, 2017

Ranked from highest to lowest age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths

|

State |

Deaths |

Population |

Age-Adjusted Rate per 100,000 |

|

West Virginia |

974 |

1,815,857 |

57.8 |

|

Ohio |

5,111 |

11,658,609 |

46.3 |

|

Pennsylvania |

5,388 |

12,805,537 |

44.3 |

|

District of Columbia |

310 |

693,972 |

44.0 |

|

Kentucky |

1,566 |

4,454,189 |

37.2 |

|

Delaware |

338 |

961,939 |

37.0 |

|

New Hampshire |

467 |

1,342,795 |

37.0 |

|

Maryland |

2,247 |

6,052,177 |

36.3 |

|

Maine |

424 |

1,335,907 |

34.4 |

|

Massachusetts |

2,168 |

6,859,819 |

31.8 |

|

Rhode Island |

320 |

1,059,639 |

31.0 |

|

Connecticut |

1,072 |

3,588,184 |

30.9 |

|

New Jersey |

2,685 |

9,005,644 |

30.0 |

|

Indiana |

1,852 |

6,666,818 |

29.4 |

|

Michigan |

2,694 |

9,962,311 |

27.8 |

|

Tennessee |

1,776 |

6,715,984 |

26.6 |

|

Florida |

5,088 |

20,984,400 |

25.1 |

|

New Mexico |

493 |

2,088,070 |

24.8 |

|

Louisiana |

1,108 |

4,684,333 |

24.5 |

|

North Carolina |

2,414 |

10,273,419 |

24.1 |

|

Missouri |

1,367 |

6,113,532 |

23.4 |

|

Vermont |

134 |

623,657 |

23.2 |

|

Utah |

650 |

3,101,833 |

22.3 |

|

Arizona |

1,532 |

7,016,270 |

22.2 |

|

United States |

70,237 |

325,719,178 |

21.7 |

|

Illinois |

2,778 |

12,802,023 |

21.6 |

|

Nevada |

676 |

2,998,039 |

21.6 |

|

Wisconsin |

1,177 |

5,795,483 |

21.2 |

|

South Carolina |

1,008 |

5,024,369 |

20.5 |

|

Alaska |

147 |

739,795 |

20.2 |

|

Oklahoma |

775 |

3,930,864 |

20.1 |

|

New York |

3,921 |

19,849,399 |

19.4 |

|

Alabama |

835 |

4,874,747 |

18.0 |

|

Virginia |

1,507 |

8,470,020 |

17.9 |

|

Colorado |

1,015 |

5,607,154 |

17.6 |

|

Arkansas |

446 |

3,004,279 |

15.5 |

|

Washington |

1,169 |

7,405,743 |

15.2 |

|

Georgia |

1,537 |

10,429,379 |

14.7 |

|

Idaho |

236 |

1,716,943 |

14.4 |

|

Hawaii |

203 |

1,427,538 |

13.8 |

|

Minnesota |

733 |

5,576,606 |

13.3 |

|

Oregon |

530 |

4,142,776 |

12.4 |

|

Mississippi |

354 |

2,984,100 |

12.2 |

|

Wyoming |

69 |

579,315 |

12.2 |

|

Kansas |

333 |

2,913,123 |

11.8 |

|

California |

4,868 |

39,536,653 |

11.7 |

|

Montana |

119 |

1,050,493 |

11.7 |

|

Iowa |

341 |

3,145,711 |

11.5 |

|

Texas |

2,989 |

28,304,596 |

10.5 |

|

North Dakota |

68 |

755,393 |

9.2 |

|

South Dakota |

73 |

869,666 |

8.5 |

|

Nebraska |

152 |

1,920,076 |

8.1 |

Source: CRS presentation of data from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), NCHS- Drug Poisoning Mortality by State: United States, 2016, https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/NCHS-Drug-Poisoning-Mortality-by-State-United-Stat/xbxb-epbu. Population estimates are from U.S. Census Bureau, American Fact Finder, Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010, to July 1, 2017, 2017 Population Estimates.

Note: CDC calculated age-adjusted death rates as deaths per 100,000 in population using the direct method and the 2000 standard U.S. population. Crude death rates are influenced by the age distribution of a state's population. Age-adjusting the rates ensures that differences from one year to another or between two areas are not due to differences in the age distribution of a state's population.

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Drug Overdose Death Data, 2017, https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. Notes: CDC calculated age-adjusted death rates as deaths per 100,000 in population using the direct method and the 2000 standard U.S. population. Crude death rates are influenced by the age distribution of a state's population. Age-adjusting the rates ensures that differences from one year to another or between two areas are not due to differences in the age distribution of the states' populations. |

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have indicated that overdose deaths have increased in states also reporting large increases in fentanyl seizures.18 In addition, there is reportedly a "strong relationship" between the number of synthetic opioid deaths and the number of fentanyl reports in the National Forensic Laboratory Information System (NFLIS).19 The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) reports that the number of fentanyl-related deaths is likely underestimated because some medical examiners do not test for fentanyl and some death certificates do not list specific drugs.20

Overview of the Opioid Supply

Heroin, fentanyl, and prescription opioids are significant drug threats in the United States—in 2017, approximately 44% of domestic local law enforcement agencies responding21 to the National Drug Threat Survey (NDTS) reported heroin as the greatest drug threat in their area.22 While the percentage of NDTS respondents reporting high availability of controlled prescription drugs (CPDs),23 which include some opioids, has declined over the last several years (75% of NDTS respondents reported high availability in 2014, compared to 52% in 2017), the reported availability of heroin has increased (30% reported high availability in 2014, compared to 49% in 2017).24 Further, there has been a rise in the availability of illicit fentanyl—the primary synthetic opioid available in the United States.25

What is the recent history of the opioid supply in the United States?

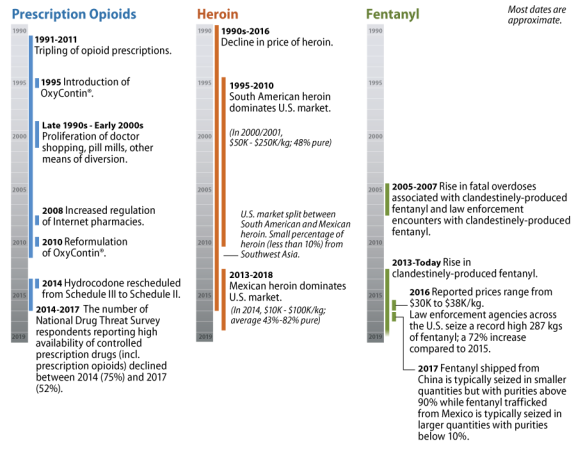

While opioids have been available in the United States since the 1800s, the market for these drugs shifted significantly beginning in the 1990s. This section focuses on this latter period (see Figure 2).

Prescription Opioid Supply

In the 1990s, the availability and abuse of prescription opioids, such as hydrocodone and oxycodone, increased as the legitimate production,26 and the subsequent diversion of some of these drugs, increased sharply.27 This continued into the early 2000s, as illegitimate prescription opioid users turned to family and friends, "doctor shopping," bad-acting physicians,28 pill mills,29 the internet, pharmaceutical theft, and prescription fraud to obtain prescription opioids.

The federal government has used varied approaches to reduce the unlawful prescription drug supply and prescription drug abuse, including diversion control through grants for state prescription drug monitoring programs30; a crackdown on pill mills; increased regulation of internet pharmacies31; the reformulation of a commonly abused prescription opioid, OxyContin® (oxycodone hydrochloride controlled-release)32; and the rescheduling of hydrocodone.33

Some experts have highlighted a connection between the crackdown on the unlawful supply of prescription drugs and the subsequent rise in the availability and abuse of heroin (discussed in the next section). Heroin is a cheaper alternative to prescription opioids, and may be accessible to some who are seeking an opioid high. Notably, while most users of prescription drugs will not go on to use heroin, accessibility and price are central factors cited by patients with opioid dependence who decide to turn to heroin.34

In October 2018, the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act (SUPPORT Act; P.L. 115-271) imposed tighter oversight of opioid production and distribution, required additional reporting and safeguards to address fraud, and limited Medicare coverage of prescription opioids.35 Also in 2018, the DEA proposed a "significant" reduction in opioid manufacturing for 2019.36 In its final order setting the aggregate production quota for certain controlled substances in 2019, the DEA noted that it "has observed a decline in the number of prescriptions written for schedule II opioids since 2014 and will continue to set aggregate production quotas to meet the medical needs of the United States while combating the opioid crisis."37

Heroin Supply

The trajectory of the heroin supply over the last several decades is much different than that of prescription opioids, but their stories are connected.38 In the late 1990s and early 2000s, white powder heroin produced in South America dominated the market east of the Mississippi River, and black tar and brown powder heroin produced in Mexico dominated the market west of the Mississippi.39 Most of the heroin found in the United States at that time came from South America, while smaller percentages came from Mexico and Southwest Asia.

In the 1990s, the purity and price of retail-level heroin varied considerably by region. The average retail-level purity of South American heroin was around 46%, which was considerably higher than that of Mexican, Southeast Asian, or Southwest Asian heroin. Mexican heroin was around 27% pure, while Southeast Asian and Southwest Asian heroin were around 24% and 30% pure, respectively.40 Retail prices for heroin fell dramatically throughout the 1990s—it was 55% to 65% less expensive in 1999 than in 1989.41

Through 2017, retail-level heroin prices continued to decline (although they increased slightly from 2015 to 2016), while purity, in particular that of Mexican heroin, has increased (although purity also dipped slightly from 2015 to 2016).42 The availability of Mexican heroin has increased. In 2016, nearly 90% of the heroin seized and tested in the United States was determined to have come from Mexico, while a much smaller portion was from South America.43 Mexican-sourced heroin dominates the U.S. heroin market, in part, because of its proximity and its established transportation and distribution infrastructure. In addition, increases in Mexican production have ensured a reliable supply of low-cost heroin, even as demand for the drug has increased. Mexican transnational criminal organizations have particularly increased their production of white powder heroin as they have expanded their retail presence44 into the eastern part of the United States (where the primary form of heroin consumed has been white powder) and they have diversified the heroin sold in western states. Of further concern is the increasing amount of heroin seizures containing fentanyl and/or fentanyl-related substances.45

Fentanyl Supply

Exacerbating the current opioid problem is the rise of illicit nonpharmaceutical fentanyl46 available on the black market. Diverted pharmaceutical fentanyl represents only a small portion of the fentanyl market. Illicit nonpharmaceutical fentanyl largely comes from China, and it is often mixed with or sold as heroin. It is 50 to 100 times more potent than heroin, and over the last several years, reported prices ranged between $30,000 and $38,000 per kilogram. The increased potency of illicit nonpharmaceutical fentanyl compounds, such as "gray death,"47 is even more dangerous. Law enforcement expects that illicit fentanyl distributors will continue to create new fentanyl products to circumvent new U.S., Chinese, and Mexican laws and regulations.48

Where are illicit opioids produced?

Illicit opioids include those from plant-based and synthetic sources. While some opium poppy crops are legally cultivated to meet global demand for scientific and medicinal purposes, the United Nations (U.N.) estimates that approximately 345,800 hectares of opium poppy crops were illicitly cultivated around the world in 2018—a 16.6% decrease from the estimated 414,500 hectares in 2017.49 The vast majority of illicit opium poppy is grown in Afghanistan, which cultivated approximately 263,000 hectares in 2018. Most heroin consumed in the United States is derived from illicit opium poppy crops cultivated in Mexico.50 According to U.S. government estimates, approximately 44,100 hectares of illicit opium poppy was cultivated in Mexico in 2017 (up from 28,000 hectares cultivated in 2015).51 Illicit cultivation of opium poppy has also been reported in Burma (37,300 hectares in 2018), Laos (5,700 hectares in 2015), and Colombia (282 hectares in 2017). Several dozen other countries have reported comparatively smaller seizures of opium poppy plants and eradication of opium poppy crops.

Synthetic opioids may enter the illicit drug market through diversion from legitimate pharmaceutical manufacturing operations or through the clandestine production of counterfeit medicines and/or of psychoactive substances intended for recreational consumption. Illicit synthetic opioids consumed in the United States are mostly foreign-sourced. According to the State Department, "China's large chemical and pharmaceutical industries provide an ideal environment for the illicit production and export of [synthetic drugs]."52 The State Department also reports that India's pharmaceutical and chemical industries are particularly susceptible to criminal exploitation; India legally produces opium for pharmaceutical uses and manufactures synthetic opiate pharmaceuticals, in addition to numerous precursor chemicals that could be diverted and used as ingredients in the production of illicit opioids. Clandestine laboratories illicitly producing fentanyl have been discovered in Mexico, Canada, the Dominican Republic, the United States, and other countries.53

How do illicit opioids enter the country?

Prescription Opioids

The active and inactive ingredients in prescription opioids may come from various countries around the world.54 Prescription drugs may be manufactured domestically or abroad. Current law and regulations allow for the importation of certain prescription drugs that are manufactured outside the country.55 Prescription drugs in the United States, regardless of where they were manufactured, flow through a regulated supply chain56—involving manufacturers, processers, packagers, importers, and distributors—until they are ultimately dispensed to end users.

The majority of misused prescription opioids available in the United States have been prescribed for a legitimate use and then diverted. Counterfeit prescription opioids are also available; in these cases, substances have often been pressed into pills in the United States, or abroad and then transported into the country, and sold. The DEA has indicated that one of the reasons traffickers may be disguising other opioids as CPDs could be that they are attempting to "gain access to new users."57

Heroin58

Mexican transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) are the major suppliers and key producers of most illegal drugs smuggled into the United States,59 and they have been increasing their share of the U.S. heroin market. The 2018 National Drug Threat Assessment notes that most illicit heroin flows into the United States over the Southwest border. It is primarily moved through legal ports of entry (POEs) in passenger vehicles or tractor trailers where it can be co-mingled with legal goods; a smaller amount of heroin is seized from individuals carrying the drugs on their person or in backpacks.60 Data from U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) indicate that in FY2018, 5,205 pounds of heroin were seized at POEs, and 568 pounds were seized between POEs.61

Illicitly Produced Fentanyl62

The DEA notes that "[f]entanyl continues to be smuggled into the United States primarily in powder or counterfeit pill form, indicating illicitly produced fentanyl as opposed to pharmaceutical fentanyl from the countries of origin."63 Fentanyl is smuggled into the United States directly from China through the mail,64 from China through Canada, or across the Southwest border from Mexico.65 Smaller quantities of fentanyl with relatively high purity (some over 90%) are smuggled from China, and larger quantities of fentanyl with relatively low purity (often less than 10%) are transported from Mexico.66 The DEA notes that Mexican traffickers often get fentanyl precursor chemicals from China. In addition, these traffickers may receive fentanyl from China, adulterate it, and smuggle it into the United States.

Data from CBP indicate that in FY2018, 1,785 pounds of fentanyl were seized at POEs, and 388 pounds were seized between POEs.67 The DEA reports that the San Diego border sector has been the primary entry point for fentanyl coming into the United States across the Southwest border (85% of the fentanyl seized coming across the Southwest border in 2017 flowed through the San Diego sector, and 14% came through the Tucson sector). Most commonly, the fentanyl seized coming through Southwest border POEs was smuggled in personally operated vehicles.68

Opioids and Domestic Supply Control Policy

How does the federal government counter illicit opioid trafficking in the United States?69

There are a number of federal departments and agencies involved in countering illicit opioid trafficking in the United States.

Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP)

ONDCP is responsible for creating, implementing, and evaluating U.S. drug control policies to reduce the use, manufacturing, and trafficking of illicit drugs as well as drug-related health consequences, crime, and violence.70 The ONDCP director is required to develop a National Drug Control Strategy (Strategy) to direct the nation's anti-drug efforts and a National Drug Control Budget (Budget) designed to implement the Strategy. The director also is required to coordinate implementation of the policies, goals, objectives, and priorities established by the Administration by agencies contributing to the Federal Drug Control Program.71 In addition, ONDCP manages several grant programs, including the High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTA) program.72 While ONDCP is not focused solely on countering opioid-related threats, it is a major priority of the office.73

HIDTA

The HIDTA program provides assistance to law enforcement agencies—at the federal, state, local, and tribal levels—that are operating in regions of the United States that have been deemed critical drug trafficking areas. There are 29 designated HIDTAs throughout the United States and its territories. The program aims to reduce drug production and trafficking through four means:

- promoting coordination and information sharing between federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement;

- bolstering intelligence sharing between federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement;

- providing reliable intelligence to law enforcement agencies such that they may be better equipped to design effective enforcement operations and strategies; and

- promoting coordinated law enforcement strategies that rely upon available resources to reduce illegal drug supplies, not only in a given area but throughout the country.74

HIDTA funds can be used to support the most pressing drug trafficking threats in the region. As such, when heroin trafficking is found to be a top priority in a HIDTA region, funds may be used to support initiatives targeting it.

In addition, in 2015 ONDCP launched the Heroin Response Strategy (HRS), "a multi-HIDTA, cross-disciplinary approach that develops partnerships among public safety and public health agencies at the Federal, state, and local levels to reduce drug overdose fatalities and disrupt trafficking in illicit opioids."75 Within the HRS, a Public Health and Public Safety Network coordinates teams of public health analysts and drug intelligence officers in each state. The HRS not only provides information to these participating entities on drug trafficking and use, but it has "developed and disseminated prevention activities, including a parent helpline and online materials."76

Other ONDCP Supply Control Initiatives

ONDCP has been involved in various other counter-trafficking operations since its creation in 1988.77 Recently, it collaborated with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security's Science and Technology Directorate (as well as CBP and the U.S. Postal Inspection Service) to launch the Opioid Detection Challenge—a $1.55 million global prize competition to seek new solutions to detect opioids in international mail.78

Department of Justice (DOJ)

DOJ controls the opioid supply through law enforcement; regulation of manufacturers, distributors, and dispensers; and grants to state and local agencies. U.S. efforts to target opioid trafficking have centered on law enforcement initiatives.

There are a number of DOJ law enforcement agencies involved in countering opioid trafficking. Within these agencies, there are a range of activities aimed at (or that may be tailored to) curbing opioid trafficking.

Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force (OCDETF) Program

The OCDETF program targets—with the intent to disrupt and dismantle—major drug trafficking and money laundering organizations. Federal agencies that participate in the OCDETF program include the DEA; Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI); Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF); U.S. Marshals; Internal Revenue Service (IRS); U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE); U.S. Coast Guard; Offices of the U.S. Attorneys; and the Department of Justice's (DOJ's) Criminal Division. These federal agencies also collaborate with state and local law enforcement on task forces.79 There are 14 OCDETF strike forces around the country and an OCDETF Fusion Center that gathers and analyzes intelligence and information to support OCDETF operations. The OCDETFs target those organizations that have been identified on the Consolidated Priority Organization Targets (CPOT) List, the "most wanted" list for leaders of drug trafficking and money laundering organizations. During FY2018, 52% of active OCDETF investigations involved heroin. According to DOJ, "OCDETF has adjusted its resources to target these investigations in an attempt to reduce the [heroin] supply."80

Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)

The DEA enforces federal controlled substances laws in all states and territories. The agency has developed a 360 Strategy aimed at "tackling the cycle of violence and addiction generated by the link between drug cartels, violent gangs, and the rising problem of prescription opioid and heroin abuse."81 The 360 Strategy leverages federal, state, and local law enforcement, diversion control, and community outreach organizations to achieve its goals. Additionally, the DEA routinely uses community-based enforcement strategies as well as multijurisdictional task forces to address opioid trafficking.82

The DEA also operates a heroin signature program (HSP) and a heroin domestic monitor program (HDMP) to identify the geographic sources of heroin seized in the United States. The HSP analyzes wholesale-level samples of "heroin seized at U.S. ports of entry (POEs), all non-POE heroin exhibits weighing more than one kilogram, randomly chosen samples, and special requests for analysis."83 The HDMP samples retail-level heroin seized in selected cities across the country.84 Chemical analysis of a given heroin sample can identify its "signature," which indicates a particular heroin production process that has been linked to a specific geographic region. In addition, the DEA has started a Fentanyl Signature Profiling Program (FSPP), analyzing samples from fentanyl seizures to help "identify the international and domestic trafficking networks responsible for many of the drugs fueling the opioid crisis."85

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)

The FBI investigates opioid trafficking as part of its efforts to counter transnational organized crime and gangs, cybercriminals, fraudsters, and other malicious actors. The FBI participates in investigations that range from targeting drug distribution networks bringing opioids across the Southwest border86 to prioritizing illicit opioid distributors leveraging the Dark Web87 to sell their drugs.88

Other DOJ Agencies

Other DOJ agencies have key roles in combatting the opioid epidemic. The Offices of the U.S. Attorneys are responsible for the prosecution of federal criminal and civil cases, which include cases against prescribers, pharmaceutical companies, and pharmacies involved in unlawful manufacturing, distribution, and dispensing of opioids as well as illicit opioid traffickers. Other enforcement agencies such as the ATF and U.S. Marshals may also be involved in seizing illicit opioids in the course of carrying out their official duties. The Office of Justice Programs (OJP) administers grant programs to address opioid supply and demand (some of which are discussed below in "Which DOJ grant programs may be used to address the opioid epidemic?").

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS)

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP)

CBP works to counter the trafficking of illicit opioids (among other drugs) along the U.S. borders as well as via mail curriers. To help detect and interdict these substances, CBP employs tools such as nonintrusive inspection equipment (including x-ray and imaging systems), canines, and laboratory testing of suspicious substances. The agency also uses information and screening systems to help detect illicit drugs, targeting precursor chemicals, equipment, and the drugs themselves.89

CBP, through the Office of Field Operations (OFO) and the U.S. Border Patrol, seizes illicit drugs coming into the United States at and between POEs.90 CBP data indicate that 90% of the heroin seized by CBP in FY2018 was seized by OFO at POEs, and 10% was seized by the Border Patrol between POEs. In addition, these data indicate that 82% of the fentanyl seized in FY2018 was seized by OFO at POEs, and 18% was seized by the Border Patrol between POEs.91

U.S. Coast Guard (USCG)

Drug interdiction is part of the Coast Guard's law enforcement mission. The agency is responsible for interdicting noncommercial maritime flows of illegal drugs. Cocaine is the primary illicit drug encountered by the Coast Guard, as it is the most common drug moved via noncommercial vessels.92 While the Coast Guard encounters other illicit drugs, including opioids, the agency notes that those drugs are more commonly moved on land or in commercial maritime vessels that are regulated by other enforcement agencies.93 The Coast Guard also participates in multi-agency counterdrug task forces, including OCDETF.

U.S. Postal Inspection Service (USPIS)

USPIS is the law enforcement arm of the U.S. Postal Service. It shares responsibility for international mail security with other federal agencies, and as a result of the opioid epidemic, it has dedicated more resources to investigating prohibited substances in the mail.94 From FY2016 through FY2018, USPIS had a "1,000% increase in international parcel seizures and a 750% increase in domestic parcel seizures related to opioids."95 In FY2018, USPIS and its law enforcement partners seized over 96,000 pounds of drugs in the mail, including marijuana, methamphetamine, synthetic opioids, and others, but their publicly available data does not describe what portion of these drugs were opioids.96

What is the DEA's role in preventing the diversion of prescription opioids?

The DEA has a key regulatory function in drug control. While it conducts traditional law enforcement activities such as investigating drug trafficking (including trafficking of heroin and other illicit opioids), it also regulates the flow of controlled substances in the United States. The Controlled Substances Act (CSA)97 requires the DEA to establish and maintain a closed system of distribution for controlled substances; this involves the regulation of anyone who handles controlled substances, including exporters, importers, manufacturers, distributors, health care professionals, pharmacists, and researchers.

Unless specifically exempted by the CSA, these individuals must register with the DEA. Registrants must keep records of all transactions involving controlled substances, maintain detailed inventories of the substances in their possession, and periodically file reports with the DEA, as well as ensure that controlled substances are securely stored and safeguarded.98 The DEA regulates over 1.5 million registrants.99

The DEA uses its criminal, civil, and administrative authorities to maintain a closed system of distribution and prevent diversion of drugs, such as prescription opioids, from legitimate purposes. Actions include inspections, order form requirements, education, and establishing quotas for Schedule I and II controlled substances.100 More severe administrative actions include immediate suspension orders and orders to show cause for registrations.101 As noted previously, in 2018 the DEA significantly lowered the aggregate production quota for opioids in 2019.102

Which DOJ grant programs may be used to address the opioid epidemic?

Discussed below are grant programs that have a direct or possible avenue to address the opioid epidemic. This discussion provides examples of such programs, and should not be considered exhaustive. Many DOJ grant programs have broad purpose areas for which funds can be used. While some focus on broad crime reduction strategies that might include efforts to combat drug-related crime, others—including the selected programs—have purpose areas that are more specifically focused on drug threats. Of note, these programs do not solely address illicit drug supply control; some also address demand as well as other criminal justice issues. They are included because they are administered by DOJ agencies.

Comprehensive Opioid Abuse Grant Program (COAP)

COAP is a recently created DOJ grant program103 (administered by BJA) for states, units of local government, and Indian tribes (34 U.S.C. 10701 et seq.). This grant program supports projects primarily relating to opioid abuse, including (1) diversion and alternatives to incarceration projects; (2) collaboration between criminal justice, social service, and substance abuse agencies; (3) overdose outreach projects, including law enforcement training related to overdoses; (4) strategies to support those with a history of opioid misuse,104 including justice-involved individuals; (5) prescription drug monitoring programs; (6) development of interventions based on a public health and public safety understanding of opioid abuse; and (7) planning and implementation of comprehensive strategies in response to the growing opioid epidemic.105

The Harold Rogers Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) was incorporated into COAP. The Harold Rogers PDMP is a competitive grant program that was created to help law enforcement, regulatory entities, and public health officials collect and analyze data on prescriptions for controlled substances. Law enforcement uses of PDMP data include (but are not limited to) investigations of physicians who prescribe controlled substances for drug dealers or abusers, pharmacists who falsify records in order to sell controlled substances, and people who forge prescriptions.106

COPS Anti-Heroin Task Force Program

The Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) Office's Anti-Heroin Task Force (AHTF) Program provides funding assistance on a competitive basis to state law enforcement agencies to investigate illicit activities related to the trafficking or distribution of heroin or diverted prescription opioids. Funds are distributed to states with high rates of primary treatment admissions for heroin and other opioids. Further, the program focuses its funding on state law enforcement agencies with multi-jurisdictional reach and interdisciplinary team structures—such as task forces.107

Drug Courts108

The Drug Court Discretionary Grant Program

The Drug Court Discretionary Grant program109 (Drug Courts Program) is meant to enhance drug court services, coordination, and substance abuse treatment and recovery support services. It is a BJA-administered, competitive grant program that provides resources to state, local, and tribal courts and governments to enhance drug court programs for nonviolent substance-abusing offenders. Drug courts are designed to help reduce recidivism and substance abuse among participants and increase an offender's likelihood of successful rehabilitation through early, continuous, and intense judicially supervised treatment; mandatory periodic drug testing; community supervision; appropriate sanctions; and other rehabilitation services.

The Drug Courts Program is not focused on opioid abusers, but drug-involved offenders, including opioids abusers, may be processed through drug courts.

Veterans Treatment Courts

BJA administers the Veterans Treatment Court Program through the Drug Courts Program using funds specifically appropriated for this purpose. The purpose of the Veterans Treatment Court Program is "to serve veterans struggling with addiction, serious mental illness, and/or co-occurring disorders."110 Grants are awarded to state, local, and tribal governments to fund the establishment and development of veterans treatment courts. While veterans treatment court grants have been part of the OJP's Drug Courts Program for several years, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 (CARA; P.L. 114-198) authorized DOJ to award grants to state, local, and tribal governments to establish or expand programs for qualified veterans,111 including veterans treatment courts; peer-to-peer services; and treatment, rehabilitation, legal, or transitional services for incarcerated veterans.112

Juvenile and Family Drug Treatment Courts

The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) supports juvenile and family drug court programs through its Drug Treatment Courts Program. This program supports the implementation or enhancement of state, local, and tribal drug court programs that focus on juveniles and parents with substance abuse issues. One of its specific goals is to help those with substance abuse problems related to opioid abuse or co-occurring mental health disorders who are involved with the court system.113

The Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) Program

Administered by BJA, the JAG program provides funding to state, local, and tribal governments for state and local initiatives, technical assistance, training, personnel, equipment, supplies, contractual support, and criminal justice information systems in eight program purpose areas: (1) law enforcement programs; (2) prosecution and court programs; (3) prevention and education programs; (4) corrections and community corrections programs; (5) drug treatment and enforcement programs; (6) planning, evaluation, and technology improvement programs; (7) crime victim and witness programs (other than compensation); and (8) mental health and related law enforcement and corrections programs, including behavioral programs and crisis intervention teams. Given the breadth of the program, funds could be used for opioid abuse programs, but state and local governments that receive JAG funds are not required to use their funding for this purpose.114

Justice and Mental Health Collaboration Program (JMHCP)

Also administered by BJA, the JMHCP supports collaborative criminal justice and mental health systems efforts to assist individuals with mental illnesses or co-occurring mental health and substance abuse disorders who come into contact with the justice system. It encourages early intervention for these individuals; supports training for justice and treatment professionals; and facilitates collaborative support services among justice professionals, treatment and related service providers, and governmental partners. Three types of grants are supported under this program: (1) Collaborative County Approaches to Reducing the Prevalence of Individuals with Mental Disorders in Jail, (2) Planning and Implementation, and (3) Expansion.115

Juvenile Justice Program Grants

Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA) Formula Grant Program

The JJDPA authorizes OJJDP to make formula grants116 to states that can be used to fund the planning, establishment, operation, coordination, and evaluation of projects for the development of more-effective juvenile delinquency programs and improved juvenile justice systems. Funds provided to the state may be used for a wide array of juvenile justice related programs, such as substance abuse prevention and treatment programs. None of the program purpose areas deal specifically with combating opioid abuse, but they are broad enough that the grants made under this program could be used for this purpose.

JJDPA Title V Incentive Grants Program

The JJDPA authorizes OJJDP to make discretionary grants117 to the states that are then transmitted to units of local government in order to carry out delinquency prevention programs for juveniles who have come into contact, or are likely to come into contact, with the juvenile justice system. Purpose areas include (but are not limited to) alcohol and substance abuse prevention services, educational programs, and child and adolescent health (as well as mental health) services. None of the program purpose areas deal specifically with combating opioid abuse, but they are broad enough that they could be used for this purpose.

Opioid Affected Youth Initiative

The Opioid Affected Youth Initiative is a competitive grant program administered by OJJDP that funds state, local, and tribal government efforts to "develop a data-driven coordinated response to identify and address challenges resulting from opioid abuse that are impacting youth and community safety."118 The program supports recipients in implementing strategies and programs to identify areas of concern, collect and interpret data to help develop youth strategies and programming, and implement services to assist children, youth, and families affected by opioid abuse.

Residential Substance Abuse Treatment (RSAT) for State Prisoners Program

The RSAT Program is a formula grant program administered by BJA that supports state, local, and tribal governments in developing and implementing substance abuse treatment programs in correctional and detention facilities. Funds may also be used to support reintegration services for offenders as they reenter the community after a period of incarceration. Beginning in FY2018, BJA requires potential grantees to explain "how funded programs will address the addition of opioid abuse reduction treatment and services."119

Tribal Resources Grant Program

The COPS Office administers the Tribal Resources Grant Program. It generally supports tribal law enforcement needs, and specifically aims to enhance tribal law enforcement's capacity to engage in anti-opioid activities, among other objectives.120

Where can DOJ opioid-related grant funding information be found?

For state-specific information on grants and funding from OJP, see the OJP Award Data web page121 and search by location or by grant solicitation. In FY2018, the Department of Justice released a document entitled, Fact Sheet: Justice Department is Awarding Almost $320 Million to Combat Opioid Crisis, which provides a list of FY2018 grantees.122

Opioids and Foreign Supply Control Policy

How does the United States respond to international illicit opioid trafficking?

The United States has taken a multipronged foreign policy approach to addressing foreign flows of illicit opioids destined for the United States. To date, this approach has included multilateral diplomacy, bilateral efforts, and unilateral action.

On the multilateral front, the U.S. government, primarily working through the U.S. Department of State, engages international organizations and entities involved in addressing drug control issues, including opioids. This includes diplomatic engagement with United Nations (U.N.) entities such as the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND), the primary U.N. counternarcotics policy decisionmaking body; the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), which monitors how member states implement treaty commitments related to drug control; and the U.N. Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC), mandated to provide technical cooperation and research and analytical projects that support member states' implementation of counternarcotics policies. The United States also addresses opioid trafficking through the Organization of American States' (OAS') Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission (CICAD). Through such organizations, the United States supports efforts to promote cross-border information sharing.

One objective of U.S. efforts at the U.N. is to accelerate the rate at which new drugs and related precursor chemicals are incorporated into the U.N. international drug control regime. For example, U.S. diplomats advocated for the international control of two of the key chemical precursors used in the production of fentanyl: N-phenethyl-4-piperidone (NPP) and 4-anilino-N-phenethyl-4-piperidone (ANPP). The CND subsequently added NPP and ANPP to the U.N.'s list of drugs and chemicals under international control, effective October 2017.123

Until recently, the United States had also engaged the Universal Postal Union (UPU) on the issue of opioid trafficking through international mail. Through the UPU, the United States had, for example, supported the exchange of advance electronic data (AED) for international mail items specifically to improve global efforts to detect and interdict synthetic drugs shipped through the mail.124 In October 2018, however, the Trump Administration announced that it would begin a one-year withdrawal process from the UPU, potentially affecting how the United States and the UPU engage on opioid matters.125

|

Role of the State Department's Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) Whether multilaterally or bilaterally, the U.S. Department of State, particularly through the INL Bureau, broadly aims to support and build foreign capacity to disrupt the flow of opioids and other illicit narcotics into the United States.126 This includes the provision of technical assistance in illicit substances detection, forensics, and cyber investigation techniques as well as sharing with international partners U.S. expertise on reducing drug demand. INL leads the U.S. delegation to the CND and supports projects of the INCB and UNODC with foreign assistance funding appropriated through the International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) foreign operations account. INL uses its INCLE funds to train foreign officials to identify and detect illicit substances. This includes providing foreign governments with specialized training to intercept suspicious drugs and chemicals sold online and shipped through the mail and express consignments. INL also funds training and technical assistance programs designed to help foreign governments investigate, prosecute, and dismantle the sale of synthetic drugs online as well as follow the digital money trail of synthetic drug traffickers.127 INL also supports demand reduction efforts to promote best practices for the prevention and treatment of drug use. This includes support for public health messaging on the risks of synthetics; assistance to foreign governments with implementing evidence-based prevention, treatment, and recovery support services; and the development of data collection on the illicit synthetic drug market, including consumption trends, toxicological screening of synthetic drug profiles, and the prevalence of toxic adulterants in illicit drug supplies.128 |

Bilateral cooperation on opioids has included focused efforts in China, Mexico, and Canada, among other countries. Such engagement has variously taken the form of structured diplomatic dialogues, bilateral law enforcement cooperation, and foreign assistance programming. With respect to China, bilateral cooperation on counternarcotics matters is a top diplomatic priority for the United States.129

As with China, U.S. officials pursue bilateral cooperation with Mexico on counternarcotics matters through meetings, including through the cabinet-level U.S.-Mexico Strategic Dialogue on Disrupting Transnational Criminal Organizations, sub-cabinet level U.S.-Mexico Security Cooperation Group, U.S.-Mexico Bilateral Drug Policy Working Group, and National Fentanyl Conference for Forensic Chemists. Trilaterally, the United States, Mexico, and Canada have met several times through the North American Drug Dialogue to address heroin and fentanyl issues. In addition to structured dialogues, U.S. federal law enforcement agencies also engage regularly with their counterparts on ongoing investigations through their representatives based at U.S. embassies and consulates abroad; formal law enforcement cooperation is also facilitated through mutual legal assistance mechanisms.130

The United States also funds and conducts programming with China and Mexico to address opioids. In China, INL funding supports drug-related information exchanges, training for Chinese counterparts on specialized topics related to synthetic opioids, and efforts to promote effective drug demand reduction. INL also funds a Resident Legal Advisor, a DOJ prosecutor who is based at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing; a key project has been to conduct outreach to Chinese counterparts involved in amending China's legal and regulatory framework to place the entire fentanyl class of substances under drug control.131 In Mexico, current efforts to address illicit opioids fit within a broader context of longstanding U.S.-Mexico cooperation to disrupt drug production, dismantle drug distribution networks, prosecute drug traffickers, and deny transnational criminal organizations access to illicit revenue.132 In such efforts, U.S. support has included programming to address illicit opium poppy cultivation and eradication, drug production and trafficking, border security, and criminal justice judicial institution reform.

In addition, the U.S. government has taken domestic action to address foreign sources and traffickers of opioids through the U.S. criminal justice system and through the application of financial sanctions against specially designated foreign nationals.133 Recent DOJ indictments have involved Chinese nationals allegedly involved in fentanyl production.134 Further targeting one of the Chinese nationals under indictment, Jian Zhang, the U.S. Department of the Treasury designated Zhang, four of his associates, and an entity used as a front for the trafficking of fentanyl and fentanyl analogues for sanction, pursuant to the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act (Kingpin Act).135 The Treasury and DOJ have taken similar action against Mexican individuals and entities involved in trafficking heroin and fentanyl to the United States.136

What has Mexico done to interrupt the flow of illicit opioids into the United States?

The government of Mexico cooperates with the United States on counternarcotics matters, including opioid supply reduction. The government eradicates opium poppy; tracks, seizes, and interdicts opioids and precursor chemicals; dismantles clandestine drug laboratories; and carries out operations against transnational organized crime groups engaged in opioid trafficking and other related crimes. The Mexican government also participates in international efforts to control precursor chemicals, including fentanyl precursors NPP and ANPP.

In 2018, the government of Mexico increased its budget for public security and justice (including antidrug efforts) by 6.2% as compared to 2017, and formed an Office of National Drug Policy within the Attorney General's Office to coordinate federal drug policy.137 Inaugurated to a six-year term in December 2018, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has continued cooperation on drug control with the United States. Observers maintain that both governments could find a common interest in combating fentanyl smuggling, but predict that the López Obrador government's proposal to regulate opium cultivation for medicinal purposes could cause friction in bilateral relations.138

The Mexican military leads efforts to eradicate illicit drug crops in Mexico, including a reported 29,692 hectares of opium poppy in 2017.139 Mexican authorities reportedly seized approximately 766.9 kilograms of opium gum140 in 2017, up from 235 kilograms in 2016.141 The United States has provided specialized training and equipment to Mexican authorities that contributed to increased fentanyl seizures in 2017 and 2018. Various Mexican agencies have identified and seized fentanyl and fentanyl-laced counterfeit pills with U.S.-funded nonintrusive inspection equipment and canine teams. In September 2018, Mexican law enforcement discovered a production mill used to produce carfentanil (an analogue 100 times more potent than fentanyl).142

What has China done to interrupt the flow of illicit opioids into the United States?

As discussed, China is a primary source of illicit fentanyl destined for the United States. As of December 1, 2018, China had imposed controls on 170 new psychoactive substances, including 25 fentanyl analogues. It had also imposed controls on two fentanyl precursor chemicals.143 According to the DEA, U.S. seizure data show that China's implementation of controls on fentanyl analogues has had "an immediate effect on the availability of these drugs in the United States."144 President Xi Jinping said China was willing to go further and control the entire class of fentanyl substances, a move supported by President Trump.145

In April 2019, three Chinese government agencies jointly announced that effective May 1, 2019, all fentanyl-related substances will be added to China's "Supplementary List of Controlled Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances with Non-Medical Use."146 Li Yuejin, Deputy Director of China's National Narcotics Control Commission, outlined a series of follow-on steps that he said China would take. He said China would issue "guidance on applicable laws for handling criminal cases related to fentanyl substances" and protocols for filing and prosecuting similar cases. Other actions he said China would take include the following:

- investigating suspected illicit fentanyl manufacturing bases;

- scrubbing drug-related content from the Internet;

- "cut[ting] off online communication and transaction channels for criminals";

- pressuring parcel delivery services to require that senders register their real names;

- stepping up inspections of international parcels;

- setting up special teams to conduct criminal investigations focused on manufacturing and trafficking of fentanyl substances and other drugs;

- strengthening information-sharing and case cooperation with "relevant countries," including the United States, with the goal of dismantling transnational drug smuggling networks; and

- stepping up development of technology for examining and identifying controlled substances.147

The DEA welcomed the Chinese government's announcement, saying, "[t]his significant development will eliminate Chinese drug traffickers' ability to alter fentanyl compounds to get around the law."148 ONDCP noted that China's scheduling decision does not cover all the precursor chemicals used to make fentanyl substances, meaning that they might continue to flow to Mexico where traffickers use them to make fentanyl destined for the United States.149

China's postal service, China Post, has an existing agreement with the USPS to provide advanced electronic data (AED) on parcels mailed to the United States.150 China's government has also cracked down on illicit fentanyl rings in China and assisted DOJ investigations of Chinese nationals suspected of illicit fentanyl manufacturing and distributing.151

Recent Congressional Action on the Opioid Epidemic

What federal laws have been enacted recently that address the opioid epidemic?

Congress largely has taken a public health approach (i.e., focusing on prevention and treatment) toward addressing the nation's opioid crisis, but recently enacted laws have addressed supply control and other criminal justice issues as well. Three major laws were enacted in the 114th and 115th Congresses that address the opioid epidemic—the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA, P.L. 114-198); the 21st Century Cures Act (Cures Act; P.L. 114-255); and the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act (SUPPORT Act; P.L. 115-271). CARA focused primarily on opioids but also addressed broader drug abuse issues. The Cures Act authorized state opioid grants (in Division A) and included more general substance abuse provisions (in Division B) as part of a larger effort to address health research and treatment. The SUPPORT Act broadly addressed substance use disorder prevention and treatment as well as diversion control through extensive provisions involving law enforcement, public health, and health care financing and coverage.152 Further, Congress and the Administration provided funds to specifically address opioid abuse in FY2017-FY2019 appropriations.

How much FY2019 funding has Congress provided DHS, DOJ, and ONDCP to address the opioid epidemic?

Many questions surround the amount of opioid funding appropriated each year. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6),153 provided $347.0 million for "comprehensive opioid abuse reduction activities, including as authorized by CARA, and for … programs, which shall address opioid abuse reduction consistent with underlying program authorities"154 (which includes many of the programs cited above in "Which DOJ grant programs may be used to address the opioid epidemic?"). In FY2019, the DEA received an increase of $77.8 million over FY2018 funding "to help fight drug trafficking, including heroin and fentanyl." The additional DEA funding will also go toward the addition of "at least four new heroin enforcement teams and DEA 360 Strategy programming."155

Other opioid-specific funding in FY2019 DOJ, DHS, and ONDCP appropriations includes

- $9.0 million for the Opioid-Affected Youth Initiative;

- $27.0 million for the COPS Program for improving tribal law enforcement, including anti-opioid activities among other purposes (the Tribal Resources Grant Program);

- $32.0 million for anti-heroin task forces (composed of state law enforcement agencies) in areas with high rates of opioid treatment admissions to be used for counter-opioid drug enforcement;

- $24.4 million for CBP for laboratory personnel, port of entry technology, canine personnel, and support staff for opioid detection;

- $44.0 million for Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) for additional personnel (criminal investigators, special agents, intelligence analysts, and support personnel) for domestic and international opioid/fentanyl-related investigations;

- $8.5 million for DHS research and development related to opioids/fentanyl; and

- $3.0 million for ONDCP for Section 103 of CARA - Community-based Coalition Enhancement Grants to Address Local Drug Crises.156

Is there an estimate for how much DOJ and other departments spend on the opioid epidemic?

It is problematic, for many reasons, to identify and sum opioid funding. The amounts listed in the section above represent instances where Congress provided opioid-specific funding for agencies and programs within DOJ, DHS, and ONDCP only. It does not include funding for some broader drug programs, such as HIDTA, unless there was a specific appropriation for opioid-related activity. Some programs that can be used for opioid-related purposes—such as the JAG program, which is used for wide-ranging criminal justice purpose areas—are not included in the list. For some programs for which Congress specified opioid-related purposes, the amount appropriated for the program is not necessarily, and often is not, entirely for opioid-related issues.

The Opioid Epidemic and State Criminal Justice Policies

How have different states adapted their justice systems to deal with the opioid crisis?

Across the country, states have adapted elements of their criminal justice responses—including police, court, and correctional responses157—in a variety of ways due to the opioid epidemic. While this section does not provide a state-by-state analysis, it highlights several examples of how states' justice systems have responded to the opioid crisis. These examples were selected because they are some of the more common state policy approaches to confronting the opioid epidemic.

Many states are increasing law enforcement officer access to naloxone, an opioid overdose reversal drug, in an effort to reduce the number of overdose deaths.158 Officers receive training on how to identify an opioid overdose and administer naloxone, and they carry the drug so they can respond immediately and effectively to an overdose. As of November 2018, over 2,400 police departments in 42 states reported that they had officers that carry naloxone159—this figure more than doubled over two years. In addition, most states that have expanded access to naloxone have also provided immunity to those who possess, dispense, or administer the drug. Generally, immunity entails legal protections (for civilians) from arrest or prosecution and/or civil lawsuits for those who prescribe or dispense naloxone in good faith.160

State and local law enforcement coordinate special operations and task forces to combat fentanyl and heroin trafficking in their jurisdictions. In addition to participation in federal initiatives, state and local police and district attorneys lead operations to dismantle trafficking networks in areas plagued by high numbers of opioid overdoses. For example, in southeast Massachusetts161 the Bristol County District Attorney recently announced the conclusion of a year-long investigation of a "highly organized and complex" fentanyl network that resulted in 11 arrests.162 This investigation was led by the Bristol Country District Attorney's office and involved several local police agencies, the Massachusetts State Police, and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.163

Another criminal justice adaptation is the enactment of what are known as "Good Samaritan" laws to encourage individuals to seek medical attention (for themselves or others) related to an overdose without fear of arrest or prosecution. In general, these laws prevent criminal prosecution for illegal possession of a controlled substance under specified circumstances. While the laws vary by state as to what offenses and violations are covered, as of June 2017, 40 states and the District of Columbia have some form of Good Samaritan overdose immunity law.164

Most states have drug diversion or drug court programs165 for criminal defendants and offenders with substance abuse issues, including opioid abuse.166 Some states view drug courts as a tool to address rising opioid abuse and have moved to expand drug court options in the wake of the opioid epidemic. Over the last several years, the National Governors Association has sponsored various activities to assist states in combatting the opioid epidemic, including learning labs to develop best practices for dealing with opioid abuse treatment for justice-involved populations—such as the expansion of opioid addiction treatment in drug courts.167 In November 2017, the President's Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis stated that DOJ should urge states to establish drug courts in every county.168

In recent years, several states have also enacted legislation increasing access to medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for drug-addicted offenders who are incarcerated or have recently been released.169 In March 2019, SAMHSA released guidance to state governments on increasing the availability of MAT in criminal justice settings.170

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

CRS Visual Information Specialist Amber Wilhelm and former CRS Research Assistant Kenny Fassel assisted with the graphics and data presented in this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), "Opioid Basics—Commonly Used Terms," https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/opioids/terms.html. |

| 2. |

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Opioids, June 2018, https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids. This CRS report uses the common term "abuse" to encompass a range of behaviors that are not limited to addiction. Such behaviors are variously described as "illicit use," "non-medical use," or "misuse," among other terms. See, for example, the terms used in American College of Preventive Medicine, Use, Abuse, Misuse & Disposal of Prescription Pain Medication: Clinical Reference, Washington, DC, 2011; and Federation of State Medical Boards, Model Policy on the Use of Opioid Analgesics in the Treatment of Chronic Pain, July 2013, pp. 15-18. |

| 3. |

Subtypes of pain relievers include hydrocodone, oxycodone, tramadol, codeine, morphine, fentanyl, buprenorphine, oxymorphone, Demerol®, hydromorphone, and methadone. See U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables, September 2018, Table 1.1A (hereinafter, Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables) and Methodological Summary and Definitions, Table C-1, https://www.samhsa.gov/data/. |

| 4. |

SAMHSA defines "misuse" of prescription drugs as "use in any way not directed by a doctor including use without a prescription of one's own medication; use in greater amounts, more often, or longer than told to take a drug; or use in any other way not directed by a doctor." Prescription drugs do not include over-the-counter drugs. |

| 5. |

Some respondents fell into both categories, which is why the total (11.4 million) is lower than the two categories combined; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2018, https://www.samhsa.gov/data/. |

| 6. |

SAMHSA defines "current use" as having used at least once in the past month. |

| 7. |

Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. |

| 8. |

Monitoring the Future is funded by the National Institute of Drug Abuse, a component of the National Institutes of Health. |

| 9. |

8th and 10th graders were not reported because the authors considered the data for this question from 8th and 10th graders to be of questionable validity. |

| 10. |

Only drug use not under a doctor's orders is included. A list of example narcotics, including Vicodin, OxyContin, and Percocet, was provided to the respondents. For more information, see Lloyd D. Johnston, et al., Monitoring the Future, National Survey Results on Drug Use: 2018 Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use, The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research, January 2019, Table 7, Trends in 30-Day Prevalence of Use of Various Drugs for Grades 8, 10, and 12 Combined. |

| 11. |

Kathryn F. Hawk, Federico E. Vaca, and Gail D'Onofrio, "Reducing Fatal Opioid Overdose: Prevention, Treatment and Harm Reduction Strategies," Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, vol. 88, no. 3 (September 3, 2015), pp. 235-245. |

| 12. |

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Drug Overdose Deaths and Understanding the Epidemic, https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/index.html; CDC, Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths—United States, 2013–2017, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), January 4, 2019; and CDC, Data Brief 294. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999-2016, data table for Figure 1, "Age-adjusted drug overdose death rates: United States, 1999-2016." |

| 13. |

The synthetic opioid category includes synthetic drugs such as fentanyl and tramadol, but methadone is excluded because the CDC tracks methadone deaths separately. See U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Drug Overdose Deaths, https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. |

| 14. |

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths – United States, 2013-2017, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, January 4, 2019, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm675152e1.htm. |

| 15. |

Nora D. Volkow, What Science Tells Us About Opioid Abuse and Addiction, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee, January 27, 2016, https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2016/what-science-tells-us-about-opioid-abuse-addiction. |

| 16. |