Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations

Changes from November 29, 2019 to October 26, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations

Contents

- Political and Economic Situation

- Political Background and Colombia's Internal Conflict

- Roots of the Conflict

- The Uribe Administration (2002-2010)

The Santos AdministrationColombia: Background and U.S. Relations October 26, 2020 Colombia, a key U.S. al y in Latin America, endured from the mid-1960s more than a half of century of internal armed conflict. To address the country’s prominence in il egal June S. Beittel drug production, the United States and Colombia have forged a close relationship over Analyst in Latin American the past two decades. Plan Colombia, a program focused initial y on counternarcotics Affairs and later on counterterrorism, laid the foundation for an enduring security partnership. President Juan Manuel Santos (2010-2018) made concluding a peace accord with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC)—the country’s largest leftist guerril a organization at the time—his government’s primary focus. Following four years of peace negotiations, Colombia’s Congress ratified the FARC-government peace accord in November 2016. During a U.N.-monitored demobilization in 2017, approximately 13,200 FARC disarmed, demobilized, and began to reintegrate. The U.S.-Colombia partnership, original y forged on security interests, now encompasses sustainable development, human rights, trade, and wider cooperation. Support from Congress and across U.S. Administrations has been largely bipartisan. Congress appropriated more than $10 bil ion for Plan Colombia and its follow -on programs between FY2000 and FY2016, about 20% of which was funded through the U.S. Department of Defense. U.S. government assistance to Colombia over the past 20 years has totaled nearly $12 bil ion, with funds appropriated by Congress mainly for the Departments of State and Defense and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The United States also has provided Colombia with assistance to receive Venezuelans fleeing their country and, as of August 2020, some $23 mil ion to respond to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. For FY2020, Congress provided $448 mil ion for State Department- and USAID-funded programs for Colombia. The House-passed FY2021 foreign aid appropriations bil , H.R. 7608, would provide $457.3 mil ion to Colombia. The 2016 Peace Accord Remains Polarizing Iván Duque, a former senator from the conservative Democratic Center party, won the 2018 presidential election and was inaugurated for a four-year term in August 2018. Duque has been critical of the peace accord, and soon after coming to office he suspended peace talks with the National Liberation Army (ELN), currently Colombia’s largest leftist guerril a group. President Duque’s approval ratings slipped early in his presidency. His government faced weeks of protests and strikes in late 2019 for a host of policies, including delays in peace accord implementation. By late 2019, 25% of the peace accord’s more than 500 commitments had been fulfil ed, though the 15-year trajectory to fulfil the ambitious accord has been stymied by several factors, including public skepticism. Violence and COVID-19 Among Ongoing Challenges The FARC’s demobilization and abandonment of il egal activities triggered violence by other armed actors competing to replace the insurgents. In August 2019, a FARC splinter faction announced its return to arms. Venezuela appears to be sheltering and perhaps collaborating with FARC dissidents and ELN fighters, causing the U.S. and Colombian governments significant concerns. Colombia’s il icit cultivation of coca peaked in 2019, and violence targeting human rights defenders and social activists, including many leading peace-related programs, has escalated. The Duque administration took early measures to contain the COVID-19 pandemic when it arrived in Colombia. However, by early October 2020, Colombia had the fifth-highest number of COVID-19 infections in the world, though its mortality rate was near the region’s average. Prior to the pandemic, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecast that Colombia’s economy would exceed 3% growth in 2020. In October, the IMF revised its forecast to a contraction of more than 8%. The United States remains Colombia’s top trading partner, although investment from China has grown. The Trump Administration has outlined a new $5 bil ion United States-Colombia Growth Initiative, Colombia Crece, Congressional Research Service Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations which could accelerate Colombia’s economic recovery and boost long-term growth by bringing investment to Colombia’s marginalized rural areas. For additional background, see CRS In Focus IF10817, Colombia’s 2018 Elections, and CRS Report RL34470, The U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Background and Issues. Congressional Research Service link to page 6 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 12 link to page 13 link to page 15 link to page 17 link to page 19 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 23 link to page 24 link to page 28 link to page 29 link to page 31 link to page 31 link to page 34 link to page 35 link to page 37 link to page 38 link to page 39 link to page 40 link to page 41 link to page 43 link to page 8 link to page 19 link to page 45 link to page 45 link to page 36 link to page 36 link to page 37 link to page 37 Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations Contents Political and Economic Situation ....................................................................................... 1 Political Background and Colombia’s Half Century Conflict ............................................ 1 Roots of the Conflict............................................................................................. 2 The Uribe Administration (2002-2010) ......................................................................... 4 The Santos Administration (2010-2018) ........................................................................ 5 The Government of Iván Duque ................................................................................... 7 Countering Il icit Crops, Corruption, and the COVID-19 Pandemic ............................. 8 Economic Issues and Trade ....................................................................................... 10 Peace Accord Implementation ................................................................................... 12 Progress and Setbacks over Four Years Implementing the Peace Accord ..................... 14 The Current Security Environment ............................................................................. 16 FARC ............................................................................................................... 16 ELN ................................................................................................................. 17 Paramilitary Successors and Criminal Bands .......................................................... 17 Humanitarian Crisis in Venezuela and Its Consequences for Colombia............................. 18 Ongoing Human Rights Concerns .............................................................................. 19 Regional Relations................................................................................................... 23 Colombia’s Role in Training Security Personnel Abroad .......................................... 24 U.S. Relations and Policy ............................................................................................... 26 Plan Colombia and Its Follow-On Strategies ................................................................ 26 National Consolidation Plan and Peace Colombia.................................................... 29 Funding for Plan Colombia and Peace Colombia .......................................................... 30 Department of Defense Assistance ............................................................................. 32 Human Rights Conditions on U.S. Assistance .............................................................. 33 Cocaine Continues Its Reign in Colombia ................................................................... 34 Drug Crop Eradication and Other Supply Control Alternatives .................................. 35 New Counternarcotics Direction Under the Duque Administration ............................. 36 Outlook ....................................................................................................................... 38 Figures Figure 1. Map of Colombia............................................................................................... 3 Figure 2. Implementation of the Colombia Peace Accord .................................................... 14 Figure A-1. Relationship of U.N. and U.S. Estimates of Coca Cultivation and Cocaine Production in Colombia............................................................................................... 40 Tables Table 1. U.S. Assistance for Colombia by State Department and USAID Foreign Aid Account: FY2012-FY2020 ......................................................................... 31 Table 2. Department of Defense Assistance to Colombia (Preliminary Figures), FY2016-FY2019 ........................................................................................................ 32 Congressional Research Service link to page 40 link to page 40 link to page 44 link to page 47 link to page 47 Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations Table 3. U.S. Estimates of Coca Cultivation in Colombia .................................................... 35 Table 4. U.S. Estimates of Pure Cocaine Production in Colombia ......................................... 35 Appendixes Appendix A. Assessing the Programs of Plan Colombia and Its Successors ............................ 39 Appendix B. Selected Online Human Rights Reporting on Colombia .................................... 42 Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 42 Congressional Research Service Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations(2010-2018)- The Duque Government and a New Legislature

- Economic Issues and Trade

- Peace Accord Implementation

- The Current Security Environment

- Humanitarian Crisis in Venezuela and Its Consequences for Colombia

- Ongoing Human Rights Concerns

- Regional Relations

- Colombia's Role in Training Security Personnel Abroad

- U.S. Relations and Policy

- Plan Colombia and Its Follow-On Strategies

- National Consolidation Plan and Peace Colombia

- Funding for Plan Colombia and Peace Colombia

- Department of Defense Assistance

- Human Rights Conditions on U.S. Assistance

- Cocaine Continues Its Reign in Colombia

- Drug Crop Eradication and Other Supply Control Alternatives

- New Counternarcotics Direction Under the Duque Administration

- Outlook

Figures

Tables

Summary

Colombia, a key Latin American ally, endured half a century of internal armed conflict. Drug trafficking fueled the violence, funding left- and right-wing armed groups. Some analysts feared in the 1990s that Colombia would become a failed state, but the Colombian government devised a novel security strategy, known as Plan Colombia, to counter the insurgencies. Plan Colombia and follow-on programs ultimately became a 17-year U.S.-Colombian bilateral effort. The partnership initially focused on counternarcotics and later included counterterrorism. When fully implemented, it also included sustainable development, human rights, trade, regional security, and other areas of cooperation.

Congress appropriated more than $10 billion for Plan Colombia and its follow-on programs between FY2000 and FY2016, about 20% of which was funded through the U.S. Department of Defense. Since 2017, Congress has provided nearly $1.2 billion in additional assistance for Colombia. For FY2019, Congress appropriated $418.1 million in foreign aid for Colombia, which encompassed efforts to promote peace and reconciliation, assist rural communities, and continue counternarcotics support through the U.S. State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development. Congress has signed two continuing resolutions for FY2020 appropriations, with FY2020 aid levels set to match FY2019 levels through late December 2019.

Peace Accord Forged But Remains Polarizing

President Juan Manuel Santos (2010-2018) primarily focused on concluding a peace accord with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC)—the country's largest leftist guerrilla organization. Following four years of negotiations, Colombia's Congress ratified the peace accord in November 2016. During a U.N.-monitored demobilization effort in 2017, some 13,000 FARC disarmed, including combatants, militia members, and others deemed eligible to demobilize.

In August 2018, Iván Duque, a former senator from the conservative Democratic Center party, was inaugurated to a four-year presidential term. He campaigned as a critic of the peace accord. His party objected to measures concerning justice and political representation of the FARC after its demobilization. Shortly after taking office, Duque suspended peace talks with the National Liberation Army (ELN)—Colombia's second-largest rebel group—which had begun under Santos.

Continuing Challenges

Many consider Plan Colombia and its successor strategies to have significantly improved Colombia's security and economic stability. Nevertheless, recent developments threaten the country's progress. The FARC's demobilization and abandonment of illegal activities have triggered open conflict among armed actors (including FARC dissidents and transnational criminal groups), who seek to control drug cultivation and trafficking, illegal mining, and other illicit businesses. In August 2019, a FARC splinter faction, which included the former lead FARC negotiator of the peace accord, announced its return to arms. In response, Venezuela appears to be sheltering and perhaps collaborating with FARC dissidents and ELN fighters, a development of grave concerns to the U.S. and Colombian governments.

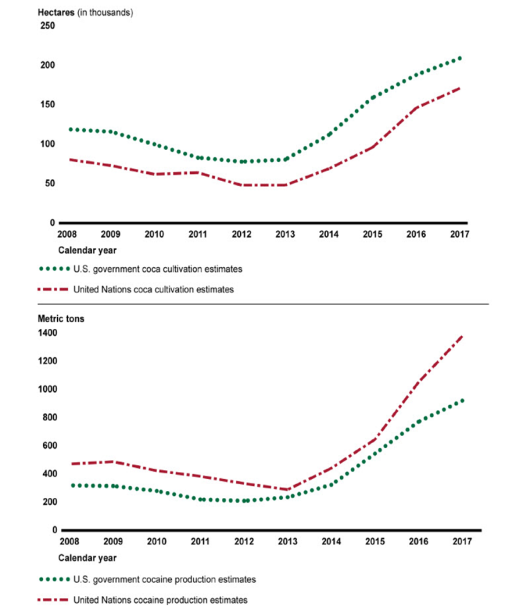

Colombia faces major challenges, including a sharp increase of coca cultivation and cocaine production; vulnerability to a mass migration of Venezuelans fleeing the authoritarian government of Nicolás Maduro; and a spike in attacks on human rights defenders, including social leaders implementing peace accord programs. As of September 2019, 1.4 million Venezuelans were residing in Colombia. Neighboring Venezuela's upheaval increased after the United States and several other nations, including Colombia, called for a democratic transition and recognized Juan Guaidó as Venezuela's interim president; as of late 2019 Guaidó and his supporters have not dislodged Maduro. Since FY2017, the U.S. State Department has allocated more than $400 million to support countries receiving Venezuelan migrants, with over half (almost $215 million in U.S. humanitarian and development assistance) for Colombia, as the most severely affected nation.

The United States remains Colombia's top trading partner. Colombia's economy grew by 2.6% in 2018 and is forecast to grow by more than 3% in 2019, with foreign direct investment also on the rise. For additional background, see CRS In Focus IF10817, Colombia's 2018 Elections, CRS Report R42982, Colombia's Peace Process Through 2016, and CRS Report RL34470, The U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Background and Issues.

Political and Economic Situation

Political and Economic Situation

Political Background and Colombia's Internal Conflict

’s Half Century Conflict

Colombia, one of the oldest democracies in the Western Hemisphere and the third most populous Latin American country, endured a multisided civil conflict for more than five decades until . Two-term

President Juan Manuel Santos declared the conflict over in August 2017 at the end of a U.N.-monitored disarmament.11 According to the National Center for Historical Memory 2013 report, presented to the Colombian government as part of the peace process, some 220,000 Colombians died in the armed conflict through 2012, 81% of them civilians.2

Colombia at a Glance Population: 49.8 million (2018, IMF)

GDP: $343.2 bil ion (2020

Poverty Rate

Key Trading Partners: United States (25.3%), China (15.7%) Mexico (6%) (2018, total trade, GTA)

Imports: $51.2 billion total. Top import products: machinery, cellular phones, motor vehicles, petroleum (2018, GTA)

|

The report also quantified the scale of the conflict, which has taken a huge toll on Colombian society: more than 23,000 selective assassinations between 1981 and 2012; internal displacement of more than 5 million Colombians due to land seizure and violence; 27,000 kidnappings between 1970 and 2010; and 11,000 deaths or amputees from anti-personnel land mines laid primarily by Colombia's main insurgent guerrilla group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).3 To date, more than 8 million Colombians, or roughly 15% of the population, have registered as conflict victims.

Although the violence has scarred Colombia, the country has achieved a significant turnaround. Once considered a likely candidate to become a failed state, Colombia, over the past two decades, has overcome much of the violence that had clouded its future. For example, between 2000 and 2016, Colombia saw a 94% decrease in kidnappings and a 53% reduction in homicides (below 25 per 100,000 in 2017—a 42-year low).4

Coupled with success in lowering violence, Colombia has opened its economy and promoted trade, investment, and growth. Colombia has become one of Latin America's most attractive locations for foreign direct investment. Yet, after steady growth over several years, Colombia's economy began to slow in 2015. It declined to 1.7% gross domestic product (GDP) growth in 2017, but recovered to 2.6% growth in 2018.5 In 2019, several sources forecast that economic growth will again exceed 3%.6

Between 2012 and 2016, the Colombian government held formal peace talks with the FARC, Colombia's largest guerrilla organization. In August 2016, the government of President Santos and FARC negotiators announced they had concluded their talks and achieved a 300-page peace agreement. The accord was narrowly defeated in a popular referendum held in early October 2016, but it was revised by the Santos government and agreed to by the FARC. The Colombian Congress ratified a revised accord at the end of November 2016.

In August 2017, President Santos announced the "end of the conflict," following the FARC's disarmament and demobilization. House. (Each chamber

Colombia has become one of Latin

has 6 additional seats in the 2018-2022 Congress due to

America’s most attractive locations for

a constitutional change and peace accord requirements)

foreign direct investment. Yet, after steady

Sources: International Monetary Fund (IMF);

growth over several years, Colombia’s

Central Intel igence Agency (CIA); Trade Data

economy began to slow in 2015. It declined

Monitor (TDM); World Bank (WB).

1 Juan Manuel Santos, “Palabras del Presidente Juan Manuel Santos en el Acto Final de Dejación de Armas de las Farc,” Presidencia de la Republica, June 27, 2017, http://es.presidencia.gov.co/discursos/170627-Palabras-del-Presidente-Juan-Manuel-Santos-en-el-acto-final-de-dejacion-de-armas-de-las-Farc and “ Aquí Estamos Viendo que lo Imposible Fue Posible,” Presidencia de la Republica, August 15, 2017. 2 Basta Ya! Colombia: Memorias de Guerra y Dignidad, Center for Historical Memory, at http://www.centrodememoriahistorica.gov.co/micrositios/informeGeneral/. 3 About half of Colombia’s 32 departments (states) have land mines, and the government has estimated that nearly 12,000 Colombians have been injured or killed by the weapons since 1990. “Estadísticas de Asistencia Integral a las

Víctimas de MAP y MUSE.” Oficina del Alto Comisionado para la Paz. August 31, 2020, http://www.accioncontraminas.gov.co/Estadisticas/estadisticas-de-victimas.

4 Statistics from Embassy of Colombia in the United States and Parker Asmann and Eimhin O’Reilly, “InSight Crime’s 2019 Homicide Round-Up,” InSight Crim e, January 28, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

1

Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations

to 1.7% gross domestic product (GDP) growth in 2017 but recovered in 2018.5 For 2019, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimatesd Colombia’s GDP expanded by 3.3%. Although the IMF had predicted the Colombian economy would expand by a similar amount in 2020, it now forecasts an 8% contraction due to the recession triggered by the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and another crash in the price of oil, which remains one of Colombia’s

top exports.6

President Iván Duque, who took office in August 2018, acknowledged that his administration faced multiple challengeschal enges related to the long internal conflict. He noted that a majority of the

peace accord'’s implementation had yet to be started, and that the country faced a volatile internal security situation where the FARC had demobilized but the state had failed to assert control in rural and peripheral parts of the country, as well as an areas most affected by the conflict. This situation was exacerbated by an enormous influx of Venezuelan migrants, who sought refuge in Colombia and continue to arrive. Later in 2019, as Venezuelans residing in Colombia surpassed 1.4 million, President Duque described Colombia as undergoing a migration "shock"—a mass movement of migrants flowing out of Venezuela across its borders.

as they fled the authoritarian government of Nicolás Maduro. As of early 2020, some 1.8 mil ion Venezuelans

were residing in Colombia.

Roots of the Conflict

Roots of the Conflict

The Colombian conflict predates the formal founding of the FARC in 1964, as the FARC had its beginnings in the peasant self-defense groups of the 1940s and 1950s. Colombian political life has long suffered from polarization and violence based on the significant inequalities suffered by landless peasants in the country'’s peripheral regions. In the late 19th19th century and part of the 20th 20th

century, the elite Liberal and Conservative parties dominated Colombian political life. Violence and competition between the parties erupted following the 1948 assassination of Liberal presidential candidate Jorge Gaitán, which set off a decade-long period of extreme violence,

known as La Violencia.

After a brief military rule (1953-1958), the Liberal and Conservative parties agreed to a form of coalition governance, known as the National Front. Under the arrangement, the presidency of the country alternated between Conservatives and Liberals, each holding office in turn for four-year intervals. This form of government continued for 16 years (1958-1974). The power-sharing

formula did not resolve the tension between the two historic parties, and many leftist, Marxist-inspired insurgencies took root in Colombia, including the FARC, launched in 1964, and the smallersmal er National Liberation Army (ELN), which formed the following year. The FARC and ELN conducted kidnappings, committed serious human rights violations, and carried out a campaign of

terror that aimed to unseat the central government in Bogotá.

(departments and capitals shown) |

|

|

Rightist paramilitary groups formed in the 1980s when wealthy ranchers and farmers, including drug traffickers, hired armed groups to protect themselves from the kidnapping and extortion plots of the FARC and ELN. In the 1990s, most of the paramilitary groups formed an umbrella umbrel a

organization, the United-Self Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC). The AUC massacred and assassinated suspected supporters of the insurgents and directly engaged the FARC and ELN in military battles. The Colombian military has long been accused of close collaboration with the AUC, accusations ranging from ignoring their activities to actively supporting them. Over time, the AUC became increasingly engaged in drug trafficking and other illicit il icit businesses. In the late

5 Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), Colombia: Country Report, October 2018. Many analysts identified Colombia’s dependence on oil and other commodity exports as the primary cause of the slowdown between 2014 and 2017.

6 International Monetary Fund (IMF), “Outlook for Latin America and the Caribbean: An Intensifying Pandemic,” IMF Blog, June 26, 2020; October 2020 World Economic Outlook, Statistical Appendix, at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/09/30/world-economic-outlook-october-2020.

Congressional Research Service

2

Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations

businesses. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the U.S. government designated the FARC, ELN, and AUC as Foreign

Terrorist Organizations (FTOs).7 The AUC was formally dissolved in a collective demobilization 7

Figure 1. Map of Colombia

(departments and capitals shown)

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS).

7 For additional background on the Foreign T errorist Organizations (FT Os) in Colombia and their evolution as part of the multisided conflict, see CRS Report R42982, Colom bia’s Peace Process Through 2016, by June S. Beittel.

Congressional Research Service

3

link to page 21 link to page 8 Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations

The AUC was formal y dissolved in a collective demobilization between 2003 and 2006 after many of its leaders stepped down. However, many former paramilitaries joined armed groups (called(cal ed criminal bands, or Bacrim, in Spanish, Bacrim, by the Colombian government) that have continued to participate in the lucrative drug trade and commit other crimes and other crime and have committed grave

human rights abuses. (For more, see " “The Current Security Environment,"” below.)

The Uribe Administration (2002-2010)

The inability of Colombia'’s two dominant parties to address the root causes of violence in the

country led to the election of an independent, Álvaro Uribe, in the presidential contest of 2002. Uribe, who served two terms, came to office with promises to take on the violent leftist guerrillas, guerril as,

address the paramilitary problem, and combat illegalil egal drug trafficking.

During the 1990s, Colombia had become the region'’s—and the world'’s—largest producer of cocaine. Peace negotiations with the FARC under the prior administration of President Andrés Pastrana (1998-2002) had ended in failure; the FARC used a large demilitarized zone located in the central Meta department (see mapmap, Figure 1) to regroup and strengthen itself. The central Colombian government granted the FARC this demilitarized zone, a traditional practice in

Colombian peace negotiations, but the FARC used it to launch terror attacks, conduct operations, and increase the cultivation of coca and its processing, while failing to negotiate seriously. Many analysts, noting the FARC'’s strength throughout the country, feared that the Colombian state might fail and some Colombian citizens thought the FARC might at some point successfully take power.88 The FARC was then reportedly at the apogee of its strength, numbering an estimated

16,000 to 20,000 fighters under arms.

This turmoil opened the way for the aggressive strategy advocated by Uribe. During President Uribe'Uribe’s August 2002 inauguration, the FARC showered the event with mortar fire, signaling the group'

group’s displeasure at the election of a hardliner, who believed a military victory over the Marxist rebels was possible. In his first term (2002-2006), President Uribe strengthened and expanded the country'country’s military, seeking to reverse the armed forces'’ prior losses to the FARC. Uribe entered

into peace negotiations with the AUC.

President Pastrana had refused to negotiate with the rightist AUC, but Uribe promoted the process and urged the country to back a controversial Justice and Peace Law that went into effect in July 2005 and provided a framework for the AUC demobilization. By mid-2006, some 31,000 AUC paramilitary forces had demobilized. The AUC demobilization, combined with the stepped-up

counternarcotics efforts of the Uribe Administrationadministration and increased military victories against the FARC'FARC’s irregular forces, helped to bring down violence, although a high level of human rights violations still stil plagued the country.99 Uribe became widely popular for the effectiveness of his security policies, a strategy he called "cal ed “Democratic Security."” Uribe'’s popular support was evident when Colombian voters approved a referendum to amend their constitution in 2005 to permit

Uribe to run for a second term.

Following his reelection in 2006, President Uribe continued to aggressively combat the FARC. For Uribe, 2008 was a critical year. In March 2008, the Colombian military bombed the camp of FARC'

8 Peter DeShazo, Johanna Mendelson Forman, and Phillip McLean, Countering Threats to Security and Stability in a Failing State: Lessons from Colom bia, Center for Strategic & International Studies, September 2009.

9 Many Colombians have expressed disappointment in the AUC demobilization for failing to provide adequate punishments for perpetrators and adequate reparations to victims of paramilitary violence. It has also been seen as incomplete because those who did not demobilize or those who re-mobilized into criminal gangs have left a legacy of criminality. For a concise history of the AUC, see “AUC Profile,” InSight Crime: Organized Crime in the Americas, at http://www.insightcrime.org/colombia-organized-crime-news/auc-profile.

Congressional Research Service

4

Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations

FARC’s second-in-command, Raul Reyes (located inside Ecuador a short distance from the border), killingkil ing him and 25 others. Also in March, another of FARC'’s ruling seven-member secretariat was murdered by his security guard. In May, the FARC announced that their supreme leader and founder, Manuel Marulanda, had died of a heart attack. The near-simultaneous deaths of three of the seven most important FARC leaders were a significant blow to the organization. In July 2008, the Colombian government dramatically rescued 15 long-time FARC hostages,

including three U.S. defense contractors who had been held captive since 2003 and Colombian senator and former presidential candidate Ingrid Bentancourt. The widely acclaimed, bloodless

rescue further undermined FARC morale.10

Uribe'10

Uribe’s success and reputation, however, were marred by several scandals, including the "parapolitics"“parapolitics” scandal in 2006 that exposed links between illegal il egal paramilitaries and politicians, especiallyespecial y prominent members of the national legislature. Subsequent scandals that came to light during the former president'’s tenure included the "“false positive"” murders allegedlyal egedly carried out by the military (primarily the Colombian Army), in which innocent civilians were killed extrajudiciallykil ed

extrajudicial y. In 2009, the media revealed illegal il egal wiretapping and other surveillancesurveil ance carried out by the government intelligence agency, the Department of Administrative Securityintel igence agency, which attempted to discredit journalists, members of the judiciary, and political opponents of the Uribe government. (In early 2012, the tarnished national intelligence intel igence agency was replaced by Uribe'’s successor, Juan Manuel Santos.)

However, military use of wiretapping continued to raise controversy, including a contentious revelation in late

2019.11

Despite the controversies, President Uribe remained popular and his supporters urged him to run for a third term. Colombia'’s Constitutional Court turned down a referendum proposed to alter the

constitution to allowal ow President Uribe a third term in 2010.

The Santos Administration (2010-2018)

Once it became clear that President Uribe was constitutionally ineligible constitutional y ineligible to run again, Juan Manuel Santos of the pro-Uribe National Unity party (or Party of the U) quickly consolidated his preeminence in the 2010 presidential campaign. Santos is, a centrist from an elite family that once owned the country'’s largest newspaper. He served as, became Uribe'’s defense minister through 2009. In 2010, Santos campaigned on a continuation of the Uribe government'’s approach to security and its role

encouraging free markets and economic opening, calling his reform policy "Democratic Prosperity." In the May 2010 presidential race, Santos took almost twice as many votes as his nearest competitor but did not win a majority. Santos won the. Santos handily won a June 2010 runoff with 69% of the vote. Santos's "’s “National Unity"” ruling coalition, formed during his campaign, included the center-right National Unity and Conservative parties, the centrist Radical Change

Party, and the center-left Liberal party.11

On August 7, 2010, during his first inauguration speech, President Santos said he planned to follow in the path of President Uribe, but "the door to [peace] talks [with armed rebels] is not locked."12 12

During his first two years in office, President Santos reorganized the executive branch, built on the market opening strategies of the Uribe Administrationadministration, and secured a free-trade agreement with the United States, Colombia'’s largest trade partner. The trade agreement went into effect in

May 2012. To address U.S. congressional concerns about labor relations in Colombia, including the issue of violence against labor union members, the United States and Colombia agreed to an Action Plan Related to Labor Rights (Labor Action Plan) in April 2011. Many of the steps

10 T he rescue operation received U.S. assistance and support. See Juan Forero, “In Colombia Jungle Ruse, U.S. Played A Quiet Role; Ambassador Spotlights Years of Aid, T raining,” Washington Post, July 9, 2008.

11 See below for more on the wiretapping issues that plagued subsequent governments. Joe Parkin Daniels, “Colombia: Spying on Reporters Shows Army Unable to Shake Habits of Dirty War,” Guardian, September 22, 2020. 12 In July 2011, the coalition contained 89 senators out of 102 in the Colombian upper house. However, in late September 2013, the Green Party (renamed the Green Alliance) broke away from the ruling coalition, although it sometimes continued to vote with the government.

Congressional Research Service

5

Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations

Action Plan Related to Labor Rights (Labor Action Plan) in April 2011. Many of the steps prescribed by the plan were completed in 2011, while the U.S. Congress was considering the free

trade agreement.

Significantly, the Santos government maintained a vigorous security strategy and struck hard at

the FARC'’s top leadership. In September 2010, the Colombian military killed kil ed the FARC'’s top military commander, Victor Julio Suárez (known as "“Mono Jojoy"”), in a bombing raid. In November 2011, the FARC'’s supreme leader, GuillermoGuil ermo Leon Saenz (aka "“Alfonso Cano"”) was assassinated. He was replaced by Rodrigo Londoño Echeverri (known as "“Timoleón Jiménez" or "Timochenko"” or

“Timochenko”), the group'’s current leader.

While continuing the security strategy, the Santos Administrationadministration began to re-orient the Colombian government'’s stance toward the internal armed conflict through a series of reforms..13 The first legislative reform that moved this new vision along, signed by President Santos in June 2011, was the Victims'’ and

Land Restitution Law (Victims'’ Law), to provide comprehensive reparations to an estimated (at the time) 4 million to 5 million mil ion to 5 mil ion victims of the conflict. Reparations under the Victims'’ Law included monetary compensation, psycho-social support and other aid for victims, and the return of mil ionsof millions of hectares of stolen land to those displaced.1314 The law was intended to process an estimated 360,000 land restitution cases.1415 (For more on the law, see textbox below on "“Status of

Implementation of the Victims'’ Law.") In June 2012, another government initiative—the Peace Framework Law, also known as the Legal Framework for Peace—was approved by the Colombian Congress, which signaled that congressional support for a peace process was growing.15

”)

In August 2012, President Santos announced he had opened exploratory peace talks with the FARC and was ready to launch formal talks. The countries of Norway, Cuba, Venezuela, and

Chile each held an international support role, with Norway and Cuba serving as peace talk hosts and "guarantors." Following the formal start in Norway, the actual negotiations began a month later in mid-November 2012 in Cuba, where the FARC-government talks“guarantors.” Launched in Norway, FARC-government talks moved to Cuba, where the

negotiations continued until their conclusion in August 2016.

In the midst of extended peace negotiations, Colombia'’s 2014 national elections presented a unique juncture for the country. As a result of the elections, the opposition Centro Democrático (CD) party gained 20 seats in the Senate and 19 in the less powerful Chamber of Representatives,1616 and its leader, former President Uribe, became a popular senator. His presence in the Senate challenged chal enged the ruling coalition that backed President Santos, who won reelection in a second-round runoff in

June 2014 against a CD-nominated presidential candidate.

In February 2015, the Obama Administration provided support to the peace talks by naming Bernard Aronson, a a former U.S. assistant secretary of state for Inter-American Affairs, as the U.S. Special Envoy to

the Colombian peace talks. Talks with the FARC concluded in August 2016. In early OctoberIn early October, after peace negotiations had ended, to the surprise of many, many, approval of the accord was narrowly defeated in a national plebiscite by less than a half percentage point of the votes cast. Regardless, President Santos was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in December 2016, in part demonstrating strong international support for the peace agreement. In response to the voters'’ criticisms, the Santos government and the FARC crafted a modified

agreement, which they signed on November 24, 2016. Rather than presenting this agreement to a plebiscite, President Santos sent it directly to the Colombian Congress, where it was ratified on November 30, 2016. Although both chambers of Colombia'’s Congress approved the agreement

13 In August 2014, for instance, the Colombian Constitutional Court ruled that demobilized guerrillas who had not committed crimes against humanity could eventually run for political office.

14 T he Victims’ and Land Restitution Law (Victims’ Law) covers harms against victims that date back to 1985, and land restitution for acts that happened after 1991.

15 Embassy of Colombia, “Victims and Land Restitution Law: Addressing the Impact of Colombia’s Internal Armed Conflict,” fact sheet, January 2013. 16 Final results for the 2014 legislative elections provided to the Congressional Research Service (CRS) by a Colombian Embassy official, July 22, 2014.

Congressional Research Service

6

Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations

s Congress approved the agreement unanimously, members of the opposition CD party, who criticized various provisions in the accord that they deemed inadequate

accord, boycotted the vote.

The peace process was recognized as the most significant achievement of the Santos presidency

and lauded outside of Colombia and throughout the region. Its innovative involvement of conflict victims in the peace talks and other features received widespread approval, but it did not win consistent support for President Santos inside Colombia, whose approval ratings fluctuated. Disgruntled Colombians perceived Santos as an aloof president whose energy and political capital were expended accommodating an often-despised criminal group. Thevictims in the peace talks and, ultimately, its focus on victims in the final 2016 accord have been viewed as a major contribution. Yet, it did not win support for President Santos inside Colombia, as his approval ratings fluctuated significantly. His crowning achievement, the accord—negotiated over accord—negotiated over

50 rounds of talks—covered five substantive topics: rural development and agricultural reform; political participation by the FARC; an end to the conflict, including demobilization,

disarmament, and reintegration; and chapters on drug policy and justice for victims.

The Duque Government and a New Legislature

The Government of Iván Duque Colombians elected a new congress in March 2018 and a new president in June 2018. Because no presidential candidate won more than 50% of the vote onin May 27, 2018, as required for a victory in the first round, a June 2018 second-round runoff was held June 17 between thebetween rightist candidate Iván Duque and the

and leftist candidate Gustavo Petro. Duque was carried to victory with almost 54% of the vote. Runner-up Petro, a former mayor of Bogotá, a former Colombian Senator, and once a member of the M-19 guerilla gueril a insurgency, nevertheless did better than any leftist candidate in a presidential race in the past century;, winning 8 million votes, mil ion votes (or 42% of the votes cast). Around 4.2% cast

blank bal ots in protest.

Through al iance. Around 4.2% were protest votes, signifying Colombian voters who cast blank ballots.

Through alliance building, Duque achieved a functional majority, or a "unity"“unity” government, which involved the Conservative Party and Santos'’s prior National Unity (or Party of the U) joining the CD, although compromise would be required to keep the two centrist parties in sync with the

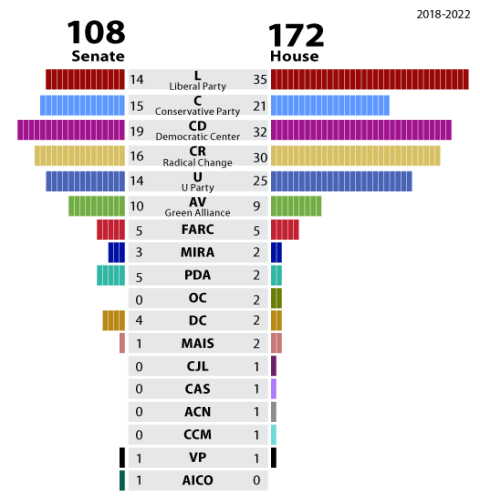

more conservative CD. In the new Congress, two extra seats for the presidential and vice presidential runners-up became automatic seats in the Colombian Senate and House, due to a 2015 constitutional change that allowedal owed presidential runner-up Gustavo Petro to return to the Senate. The CD party, which gained seats in both houses in the March vote, won the majority in the Colombian Senate (see Figure 2 for seat breakouts by party). However, the legislative majority fractured during President Duque'’s first year in office, which has left his government with limited support in Congress to accomplish major legislative objectives.

(March 11, 2018, results and the 12 automatic seats shown) |

|

Notes: FARC=Revolutionary Alternative Common Force; MIRA=Absolute Renovation Independent Movement; PDA=Alternative Democratic Pole; OC=Citizens' Option; DC=Decentes; MAIS=Alternative Indigenous and Social Movement; CJL=Colombia Justa Libres; CAS=Alternate Santander Coalition; ACN=Ancestral Afro-Colombian Communal Council of Playa Renaciente; CCM=La Mamuncia Communal Council; VP (Second Place Presidential in the Senate; Second Place Vice Presidential in House); AICO=Indigenous Authorities of Colombia. |

Duque was inaugurated on August 7, 2018, and at the age of 42 was Colombia's youngest president elected in a century. He possessed limited prior experience in Colombian politics. Duque was partially educated in the United States and worked for a decade at the Inter-American Development Bank in Washington, DC. He was the handpicked candidate of former president Uribe, who vocally opposed many of Santos's policies. Disgruntled Colombians perceived Santos as an aloof president whose energy and political capital were expended accommodating an often-despised criminal group. President Duque campaigned on his experience as a technically oriented politician, who presented himself as a modernizer.

left his government with limited support in Congress to accomplish major

legislative objectives.17

President Duque campaigned on his experience as a technical y oriented politician and presented

himself as a modernizer. Duque was inaugurated in August at the age of 42—Colombia’s youngest president elected in a century. He possessed limited prior experience in Colombian politics. Duque was partial y educated in the United States and worked for a decade at the Inter-American Development Bank in Washington, DC. He was the handpicked candidate of former

president Uribe, who vocal y opposed many of Santos’s policies.

17 T he FY2018-2022 Colombian Congress has 280 seats, including 10 for FARC party representatives (9 of which are currently filled). T he two legislative sessions run from July 20 to December 16 and from March 16 to June 20. T he Senate members are elected nationally (not by district or state), with two coming from a special ballot for indigenous communities. T he House of Representatives has two members from each of Colombia’s 32 departments (states) and 1 more for each 125,000-250,000 inhabitants in a department, beyond the first 250,000. In the House, two seats are reserved for the Afro-Colombian community, one for indigenous communities, one for Colombians residing abroad, and one for political minorities.

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 41 link to page 41 Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations

In a September 2018 speech before the U.N. General Assembly, the new president outlined his policy objectives.17 Duque called.18 Duque cal ed for increasing legality, entrepreneurship, and fairness by (1) promoting peace; (2) combating drug trafficking and recognizing it as a global menace; and (3) fighting corruption, which he characterized as a threat to democracy. He also maintained that the humanitarian crisis in neighboring Venezuela was an emergency that threatened to destabilize the region. Duque proposedembraced a leadership role for Colombia in denouncing the authoritarian

government of President Nicolás Maduro.

By late 2018, Colombia'’s acceptance of more than 1 milliona mil ion Venezuelans was adding pressure on

the government'’s finances, generating a burden estimated at nearly 0.5% of the country'’s GDP.18

President Duque also campaigned on returning to spraying coca crops with the herbicide glyphosate. This would reverse Colombia'19 The influx of Venezuelan refugees and migrants continued in 2020; despite some reverse migration during the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly 1.8 mil ion Venezuelans remained in Colombia in early September 2020, according to the U.S. Agency for International Development

(USAID).20

Colombian authorities have registered over 8 mil ion victims in the country’s five-decade internal conflict—equivalent to about 15% of the current population—with 7.2 mil ion currently eligible for reparations under the peace accord. The most common form of victimization is internal

displacement; Colombia has the world’s second-highest number of internal y displaced persons, numbering nearly 8 mil ion. Many observers raise concerns about human rights conditions inside Colombia and the ongoing lack of governance in remote rural areas, such as the nearly 1,400-mile

border area alongside Venezuela.

Countering Illicit Crops, Corruption, and the COVID-19 Pandemic

President Duque campaigned on restarting the practice of spraying coca crops with the herbicide glyphosate to reduce supply. This would reverse Colombia’s decision in mid-2015 to end aerial spraying, which had been a central—albeit controversial—feature of U.S.-Colombian counterdrug cooperation for two decades.1921 In 2017, Colombia'’s Constitutional Court decided to retain the suspension of the use of glyphosate until the government took measures to limit its impact on humans. In 2020, Colombia continues to face chal enges in destroying and removing

coca crops, as rural areas contend with rising levels of violence and economic desperation due to competition over the FARC’s former il icit economies. (For more, see “New Counternarcotics

Direction Under the Duque Administration” below.)

Corruption has become a top concern in Colombian politics, as members of the judicial branch, politicians, and other officials have faced a series of corruption charges.22 Colombians’ concerns

18 Embassy of Colombia in the United States, “T he Pact for Fairness and Progress,” Remarks by the President of the Republic, Iván Duque Márquez, before the General Assembly of the United Nations in the 73 rd period of ordinary sessions. September 26, 2018.

19 Antonio Maria Delgado, “ Colombia Will Find It Hard to Accept Another 1 Million Venezuelan Migrants,” Miami Herald, November 27, 2018.

20 U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), “Venezuela Regional Crisis – Complex Emergency, Fact Sheet #3, FY2020,” September 25, 2020. 21 For additional background, see CRS Report R44779, Colombia’s Changing Approach to Drug Policy, by June S. Beittel and Liana W. Rosen.

22 A corruption national referendum in August 2018 was backed by President Duque but did not reach its threshold (failing to do so by less than half a percentage point). T he actual vote favored all seven proposed changes on the ballot, and Duque pledged to address some of the anti-corruption measures presented in the referendum through legislation. For recent polling on the public concern about corruption, see U.S. State Department, Office of Opinion Research, “Colombia: Nearly Four Years On, the Public Down on FARC Peace,” OPN-X-20, September 23, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

8

Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations

about corruption became particularly acute during the 2018 elections, as major scandals were revealed. Several government officials were discovered to have received funding from Odebrecht, a Brazilian construction company embroiled in a region-wide corruption scandal.23 In December 2018, presidential runner-up Gustavo Petro also was accused of taking political contributions from Odebrecht, suggesting corrupt practices had taken hold across the Colombian political

spectrum.24

Despite an early and long-lasting national lockdown from March to September 2020, Colombia was unable to stop a severe COVID-19 outbreak that led to one of the Western hemisphere’s

highest daily death tolls from the virus. Observers note that government measures failed to reach and protect the poor, who tend to be more vulnerable to COVID-19 infection due to their living conditions and high levels of informal employment.25 By mid-October 2020, Colombia had some 28,000 deaths (56.4 deaths per 100,000). Nevertheless, Colombia’s mortality rate was wel below several other countries in the hard-hit Latin American region. Although Colombia had registered 1 mil ion COVID-19 infections as of October 2020 (for a time, the fifth-highest number in the

world), some experts suggested widespread testing was stil lagging.26

The Duque administration struggled with low approval ratings and dissent within its governing

coalition throughout 2019. The administration’s first budget for 2019 (presented in late October 2018) was linked to an unpopular tax reform that would subject food and agricultural commodities to a value-added tax. Duque’impact on humans.

Colombians' concerns about corruption became particularly acute during the 2018 elections, as major scandals were revealed. Similar to many countries in the region, government officials, including Santos during his 2014 campaign for reelection and the opposition candidate during that campaign, were accused of taking payoffs (bribes) from the Odebrecht firm, the Brazilian construction company that became embroiled in a region-wide corruption scandal. In December 2018, presidential runner-up Gustavo Petro was also accused of taking political contributions from Odebrecht with evidence presented by a CD senator, indicating that both the left and the right of the Colombian political spectrum have been tainted by corruption allegations.20A series of corruption charges made against members of Colombia's judicial branch, politicians, and other officials made the issue prominent in Colombian politics. In late August 2018, an anti-corruption referendum was defeated, narrowly missing a high vote threshold by less than half a percentage point, although the actual vote favored all seven proposed changes on the ballot. President Duque endorsed the referendum and maintains he will seek to limit abuses identified in the referendum through legislation.

The Duque Administration's first budget for 2019 (presented in late October 2018) was linked to an unpopular tax reform that would expand a value-added tax to cover basic food and agricultural commodities. The 2019 budget totals $89.7 billion, providing the education, military and police, and health sectors with the biggest increases, and reducing funding for peace accord implementation.21 Duque's own Democratic Center party split with him on the value-added tax, which quickly sank his approval ratings from 53% in early September 2018 to a low of 27% in November 2018.27 Duque’s national coalition was further weakened when some parties broke from it and, in October 2019, when Defense Minister Guil ermo Botero was

threatened with censure in the Colombian Congress. Botero was forced to resign, leading to a major cabinet reshuffle.28 Weeks of protest in autumn 2019 centered on concern about the peace

accord’s stal ed implementation, social leader kil ings, and pension and tax matters.29

However, in the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak, the government coalition expanded to include the centrist right-leaning Cambio Radical party and others, providing a majority in the Senate and a near majority for the government coalition in the Chamber of Representatives.30 This expanded coalition provided the Duque administration with sufficient legislative support to enact several pandemic-related measures. Duque’s approval ratings improved in April 2020 to over 50% in

light of the government’s success with managing the virus outbreak and settled at 48% in a poll

taken in early October 2020.31

23 In 2014, President Santos’s reelection campaign and the opposition candidate’s campaign were both accused of accepting Odebrecht funding.

24 “Corte Suprema Llama a Declaración a Varios T estigos en el Caso del Video de Petro,” El Espectador, December 10, 2018.

25 Ana Vanessa Herrero, “Locked-Down Colombians Fly Red Flags to Call for Help,” Washington Post, May 11, 2020. 26 Sara T orres and Avery Dyer, “Argentina and Colombia, A T ale of T wo Lockdowns,” Weekly Asado, Wilson Center, October 2, 2020.

27 See Invamer’s Colombia Opina #2,” Semana, November 2018. 28 Arthur Dhont, “Colombian Government Likely to Struggle to Implement Economic Policies in 2020 Because of Social and Legislative Opposition,” HIS Global Insight Analysis, November 12, 2019; “Colombia: Embattled Duque Prepares for Protests,” LatinNews Weekly Report, November 14, 2019. 29 “Will Protesters Keep T aking to the Streets in Colombia?,” Latin America Advisor (blog), Dialogue, September 23, 2020.

30 EIU, Country Report: Colombia, October 2020. 31 Invamer polling results from April 8-26, 2020, at https://docs.google.com/viewerng/viewer?url=https://

Congressional Research Service

9

Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations

In September 2020, amid a rise in mass kil ings and violence in the Colombian countryside, protests against police brutality and abuse in response to social protest were fueled by the death of a Colombian lawyer at the hands of the Bogotá police.32 In mid-October, a national mobilization of indigenous groups that traveled across the country to come to the capital joined a national strike by students; labor unionists; and those concerned with flagging peace accord implementation, political violence, and pandemic response in largely peaceful protest in cities and

towns across Colombia.33

low of 27% in November 2018,22 among the lowest levels in the early part of a presidential mandate. In August 2019, Duque's approval rating rested near 29% (with a disapproval level of 63%), and he faced a continued lack of unified congressional backing.23 His coalition, which had established a congressional majority with other center and center-right parties, appeared to fall apart in early 2019, when some of the parties abandoned the ruling coalition; this process accelerated in October 2019. At that time, Defense Minister Guillermo Botero, threatened with censure in the Colombian Congress, resigned, leading to a major Cabinet reshuffle.24

As the Duque Administration passed its one-year mark, it faced the challenges of bringing a record expansion of coca cultivation and cocaine production under control, implementing the peace accord, and controlling crime and violence by armed groups seeking to replace the FARC, while addressing spillover challenges from a destabilized Venezuela. To date, the Colombian government has registered over 8 million victims of its own 52-year conflict, about 15% of the country's population, of which about 6.7 million are eligible for reparations under the peace accord. The most significant cause of the conflict's victimization is internal displacement; Colombia has the world's second-highest number of internally displaced persons. Many observers raise concerns about human rights conditions inside Colombia and the ongoing lack of governance in remote rural areas, such as the nearly 1,400-mile border area alongside a severely troubled Venezuela.

Economic Issues and Trade

Economic Issues and Trade The Colombian economy is the fourth largest in Latin America after Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina (as measured at the end of 20182019). The World Bank characterizes Colombia as an upper-middle-income country, although its commodities-dependent economy has been hit by oil price declines and peso devaluations, at times eroding fiscal revenue. The United States is Colombia's ’s largest trade partner, and bilateral economic relations have deepened since the U.S.-Colombia

Free Trade Agreement entered into force in May 2012.2534 By 2021, the agreement willis to phase out all

al tariffs on consumer and industrial products.

The total stock of U.S. investment in Colombia was $7.2 billionrose to $7.2 bil ion in 2017, with mining, manufacturing, and wholesale trade as the leading sectors. According to the 2020 National Trade Estimate Report, U.S. foreign direct investment (FDI) in Colombia was $7.7 bil ion in 2018, a 7.1% increase over 2017, led by mining, manufacturing, finance, and insurance.35 In common with most Latin American nations, Colombia has sought over the past decade to increase the attractiveness of investing. Some analysts contend that Colombia’s FDI increase came not only

from the extractive industries, such as petroleum and mining, but also from such areas as agricultural products, transportation, and financial services. Investment from China in Colombia has increased at a slow but steady rate in recent years, including in the Bogotá metro system and

communications.36 Over the past decade, the bulk of Chinese investment has been in oil and gas.37

manufacturing, and wholesale trade as the leading sectors.26 Colombia's GDP expanded by 2.6% in 2018, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit, and is projected to grow by slightly more than 3% in 2019.27

Promoting more equitable growth and ending the internal conflict were twin goals of the two-term Santos Administration. Unemployment, which historically has been high at over 10%, fell below that double-digit mark during Santos's first term and remained at 9.2% in 2016. It rose slightly to 9.7% in 2018. For the first three quarters of 2019, unemployment exceeded 10%.28 Despite its relative economic stability, high poverty rates and inequality have contributed to social upheaval in Colombia for decades. The poverty rate in 2005 was slightly above 45%, but it declined to below 27% in 20162018. The issues of limited land ownership and high rural poverty rates remain contentious.29 According to a United Nations study published in 20112011 U.N. study, 1.2% of the population owned 52% of the noticias.caracoltv.com/sites/default/files/encuesta_invamer_abril_2020.pdf; “ Encuesta de Opinión” and Centro Nacional de Consultoría, S.A.. October 5, 2020, at https://www.valoraanalitik.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Encuesta-CNC.pdf.

32 Juan Pappier, “T he Urgent Need to Reform Colombia\’s Security Policies,” Human Rights Watch, Americas Quarterly, September 22, 2020; Steven Grattan and Anthony Failoa, “ In Colombia, a Death in Police Custody Follows a History of Brutality,” Washington Post, October 6, 2020. 33 ”Protesters in Colombia Decry Government Pandemic Response,” Associated Press, October 21, 2020; Bocanegra, Nelson. “T housands, Including Indigenous People, March in Peaceful Colombia Protests,” Reuters, October 21, 2020. 34 T he agreement is officially known as the U.S.-Colombia T rade Promotion Agreement. For more background, see CRS Report RL34470, The U.S.-Colom bia Free Trade Agreem ent: Background and Issues, by M. Angeles Villarreal and Edward Y. Gracia. 35 United States T rade Representative, “2019 National T rade Estimate Report,” March 2019; “2020 National T rade Estimate Report,” March 2020. 36 “China’s Strong Push into Colombia,” Al Jazeera, February 22, 2020; “Foreign Investment in Colombia Holds Firm, says T rade Minister,” Financial Tim es, October 7, 2020.

37 “Colombia: OFDI China a Nivel de Empresa (200-2019),” accessed October 28, 2020, distributed by Red Académica de América Latina y el Caribe sobre China y Monitor de la OFDI de Chin a en América Latina y el Caribe, at https://www.redalc-china.org/monitor/informacion-por-pais/busqueda-por-pais/31-colombia.

Congressional Research Service

10

Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations

land, and data revealed in 2016 indicated about half of working Colombians were employed in the informal economy. Promoting more equitable growth and ending the internal conflict were twin goals of the two-term former Santos administration. Unemployment, which historical y has been at over 10%, fel below that double-digit mark during Santos’s first term and remained so until it nudged just over 10% in 2018. In 2019, the Duque administration’s first full year in office, Colombia’s unemployment rate climbed to 10.5%. The Economist Intel igence Unit estimates

that in 2020, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Colombia’s unemployment rate wil

exceed 16% (adding a mil ion newly unemployed).38

Colombia’s Stimulus to Foster a Recovery

Fol owing one of the longest national lockdowns in South America, begun in March 2020, Colombia lifted its pandemic-related restrictions to reopen ful y in September. The government enacted measures to counter a historic economic contraction (more than 15%, from April to June 2020), the country’s worst quarter-on-quarter economic performance on record. The Colombian government announced fiscal measures, including flexibility in the use of income to finance extraordinary operating expenditures and a relaxation of debt rules. In a May 2020 executive decree, the government announced it would subsidize 40% of the $250-per-month minimum wage for workers at companies that have seen revenues drop by at least 20% during the pandemic. On September 22, the government announced it would issue another round of subsidies in December to such businesses. In late September, Colombia’s government signaled its plans to draw from an International Monetary Fund (IMF) flexible credit line that was recently increased by the IMF to $17.2 bil ion. This is the first time any country has tapped resources from that mechanism since it was set up in 2009. The Colombian government’s recovery strategy includes three planks: (1) refocusing on renewable energy, (2) speeding development in its rural periphery most affected by the 50-year internal conflict, and (3) extending broadband as part of a Colombian digital transition. These approaches aim to transform Colombia from a commodity-based economy to a value-added services economy.

Sources: Economist Intel igence Unit (EIU), Country Report: Colombia, September 2020; EIU, “Colombia to Draw from IMF Flexible Credit Line,” October 6, 2020; Mariana Palau, “Colombia Pins Recovery Hopes on Technology not Oil,” Financial Times, October 7, 2020; Luisa Horwitz, Paoloa Nagovitch, Hol y Sonneland, and Carin Zissis, “The Coronavirus in Latin America,” Americas Society/Council of the Americas, September 23, 2020.

According to State Department, 1.2% of the population owned 52% of the land,30 and data revealed in 2016 that about 49% of Colombians continued to work in the informal economy.

Colombia is often described as a country bifurcated between metropolitan areas with a developed, middle-income economy, and some rural areas that are poor, conflict-ridden, and weakly governed. The fruits of the growing economy have not been shared equally with this ungoverned, largely rural periphery. Frequently these more remote areas are inhabited by ethnic minorities or other disadvantaged groups, such as Afro-Colombians, indigenous populations, or landless peasants and subsistence farmers, who are vulnerable to illicit economies due to few connections to the formal economy.

Despite Colombia's macroeconomic stability, several issues remain, such as a still-complicated tax system, a high corporate tax burden, and continuing piracy and counterfeiting concerns. Colombia's rural sector protestors have periodically demanded long-term and integrated-agricultural reform in a country with one of the most unequal patterns of land ownership.31 In October and November 2018, Colombian secondary and university students protested in high numbers during six large mobilizations, taking place over 60 days, to demand more funding for education.32 The student mobilizations continued in late October 2019, placing pressure on the Duque government as social demands in Argentina, Chile, and other developed South American economies raised the specter of prolonged citizen protests.

The United States is Colombia's leading trade partner. Colombia accounts for a small percentage of U.S. trade (approximately 1%), ranking 22nd among U.S. export markets and 27th among foreign exporters to the United States in 2017.33 Colombia has secured free trade agreements with the European Union, Canada, and the United States, and with most nations in Latin America. Colombian officials have worked over the past decade to increase the attractiveness of investing in Colombia, and foreign direct investment (FDI) grew by 16% between 2015 and 2016. This investment increase came not only from the extractive industries, such as petroleum and mining, but also from such areas as agricultural products, transportation, and financial services.

In 2017, U.S. foreign direct investment (FDI) in Colombia totaled $7.2 billion. In the first two quarters of 2019, according to Colombia's government, U.S. FDI increased by more than 24% over the same period in 2018.34 Colombia has made progress on trade issues, such as copyright, pharmaceuticals, fuel and trucking regulations, and labor concerns (including subcontracting methods and progress on resolving cases of violence against union activists).

Although Colombia is ranked highly for business-friendly practices and has a favorable regulatory environment that encourages trade across borders, it is still plagued by persistent corruption and an inability to effectively implement institutional reforms it has undertaken, particularly in regions where government presence is weak. According to the U.S. State Department in its analysis of national investment climates, Colombia has demonstrated a political commitment to create jobs, develop sound capital markets, and achieve a legal and regulatory system that meets international norms for transparency and consistency.

Colombia is a founding member of the Pacific Alliance along with Chile, Mexico, and Peru. It has sought to deepen trade integration and cross-border investment with its partners in this alliance. The Pacific Alliance aims to go beyond reducing trade barriers by creating a common stock market, allowing for the eventual free movement of businesses and persons, and . Within a framework of relative economic stability, Colombia has a complicated tax system, high corporate tax burden, and ongoing piracy and counterfeiting concerns. In Transparency International’s Corruption

Perception Index, Colombia ranked 96 out of the 180 countries polled in 2019, placing it

regional y just behind Ecuador and ahead of Peru, Brazil, and Mexico.39

Colombia’s rural sector activists periodical y have demanded long-term and integrated-agricultural reform in a country with one of the most unequal patterns of land ownership in the world and many landless rural poor. The Duque government also has faced pressure from student mobilizations and other groups demanding more public education funding, full peace accord compliance, and greater employment opportunity.40 Although protests waned during the

pandemic, they may reemerge with increased demands as restrictions are lifted.

38 EIU, Country Report: Colombia, September 2020. 39 T ransparency International, “Corruption Perceptions Index 2019,” January 2020, at https://www.transparency.org/cpi2019. 40 Steven Grattan, “Colombia Protests: What Prompted T hem and Where Are T hey Headed?,” Al Jazeera, November 26, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

11

Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations

The United States is Colombia’s leading trade partner. Colombia accounts for a smal percentage of U.S. trade (approximately 1%), ranking 23rd among U.S. export markets and 25th among foreign exporters to the United States in 2019. Colombia has secured free-trade agreements with the European Union, Canada, and the United States, as wel as with most nations in Latin

America.

Colombia is a founding member of the Pacific Al iance along with Chile, Mexico, and Peru. The Pacific Al iance aims to go beyond reducing trade barriers by creating a common stock market, al owing for the eventual free movement of businesses and persons, and by serving as an export

serving as an export platform to the Asia-Pacific region. Colombia's role in the Pacific Alliance and Colombia's accession to the Organization forIn April 2020, Colombia became the third Latin American country to join the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development, which it is in the process of completing after being invited to become a member in May 2018 (following a review of the country's macroeconomic policies), are relatively new developments.

after a seven-year

accession process.

In August 2020, the Trump Administration announced a new United States-Colombia Growth Initiative, Colombia Crece, to harness assistance from a variety of U.S. agencies, such as the International Development Finance Corporation, to bring investment to Colombia’s rural areas and fight crime through sustainable development and growth. According to U.S. National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien, on an official visit to Colombia in August 2020, investment

levels wil reach $5 bil ion.41

Peace Accord Implementation Peace Accord Implementation

The four-year peace talks between the FARC and the Santos Administrationadministration started in Norway and moved to Cuba, where negotiators worked through a six-point agenda during more than 50 rounds of talks. Over the course of four years, the Colombian government and the FARC

negotiated several central issues, with the following major sub-agreements:

- land use and rural development (May 2013);

- the FARC

'’s political participation after disarmament (November 2013); illicit il icit crops and drug trafficking (May 2014);victims' victims’ reparations and transitional justice (December 2015); and- the demobilization

A sixth topic provided for mechanisms to implement and monitor the peace agreement. All Al parties to the accord recognized that implementation would be challengingchal enging, with many Colombians

questioning whether the FARC would be held accountable for its violent crimes.35 The42

In August 2016, the Santos administration and FARC negotiators announced they had concluded their talks and achieved a 300-page peace agreement. The accord was narrowly defeated in a popular referendum held in early October 2016, but it was revised by the Santos government and agreed to by the FARC. The Colombian Congress ratified a revised accord at the end of

November 2016.

41 White House, “Statement by National Security Advisor Robert C. O’Brien, Press Release, August 17, 2020;

“Colombia y Estados Unidos Lanzan Iniciativa ‘Colombia Crece.’” El Tiempo. August 17, 2020. https://www.eltiempo.com/politica/gobierno/colombia-y-estados-unidos-lanzan-iniciativa-colombia-crece-530200.

42 For more background on the peace talks and the actors involved in the conflict, see CRS Report R42982, Colombia’s Peace Process Through 2016, by June S. Beittel.

Congressional Research Service

12

link to page 19 Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations

Colombia’s Constitutional Court ruled in October 2017 that over the next three presidential terms (until 2030), Colombia must follow the peace accord commitments.43The Special Jurisdiction of Peace (JEP by its Spanish acronym), set up to adjudicate the most heinous crimes of Colombia's ’s decades-long armed conflict, began to hear cases in July 2018. However, Colombians remain skeptical of itsthe JEP’s capacity. Some analysts have estimated that implementing the programs required byin the accord may cost up to $45 bil ion over 15 years.44 the accord may take 15 years and cost from $30 billion to $45 billion.36 The country faces steep challenges

chal enges to underwrite the post-accord peace programs in an era of declining revenues and competing challengeschal enges, such as the influx of Venezuelan migrants.

and the health and economic

crises resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.

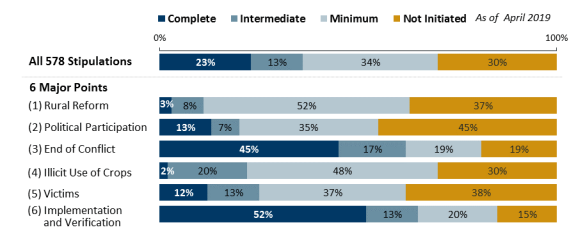

The Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame is responsible for monitoring implementation of the peace agreement. The latest assessment, covering developments through November 2019, shows the portions of the agreement furthest along in implementation are disarmament and demobilizationagreement. It released its latest assessment in April 2019. In the Kroc Institute review of implemented commitments shown in Figure 3, disarmament and demobilization is the most complete. During a U.N.-monitored demobilization effort in 2017, some 13,200 FARC (armed combatants and militia members) disarmed, demobilized, and

began the reintegration process.37 45

By contrast, the least-implemented commitments include landpeace accord elements (see Figure 2) involve land reform and

and rural development elements,, particularly measures concerned with more equitable access to land for rural inhabitants. There also have been limited advances in implementation of the National Program for the Substitution of Il icit Crops and the Comprehensive Community and Municipal Substitution

and Alternative Development Programs in some 3,053 vil ages in 19 departments.46

43 “Colombia Peace Deal Cannot Be Modified for 12 years, Court Rules,” Reuters, October 11, 2017. 44 See, for instance, “Implementacíon del Acuerdo de Paz Necesitaria $76 Billones Adicionales,” El Espectador, September 21, 2018. 45 T he 13,200 demobilized FARC include those who had been imprisoned for crimes of rebellion, who were accredited by the Colombian government as eligible to demobilize. (T ally of demobilized from Luisa Fernando Mejía, “How Colombia Is Welcoming Migrants—and Staying Solvent,” Am ericas Quarterly, September 11, 2019, at https://www.americasquarterly.org/content/how-colombia-welcoming-migrants-and-staying-solvent .)

46 Germán Valencia and Fredy Chaverra, “PDET -PNIS T erritories in T ension with the Future Zones,” Fundacion Paz y Reconciliacion. July 20, 2020, at https://pares.com.co/2020/07/21/territorios-pdet-pnis-en-tension-con-las-zonas-futuro/.

Congressional Research Service

13

Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations

Figure 2 concerned with more equitable access to land, including connecting the impoverished rural parts of Colombia to the main economy, and counternarcotics programs to support the transition to licit crops.

In July 2017, the U.N. Security Council voted to establish the U.N. Verification Mission in Colombia for a period of three years.38 On September 12, 2019, the U.N. Security Council extended the mission's mandate until September 25, 2020 to verify implementation of the Colombian accord with the FARC.39 Colombia's Constitutional Court ruled in October 2017 that over the next three presidential terms (until 2030), Colombia must follow the peace accord commitments.40

|

|

. Implementation of the Colombia Peace Accord

Source: Created by CRS with data Notes: The Kroc Institute is the first university-based research center to directly support the implementation of a peace accord. |

While progress has been uneven across the all commitments, some programs received external commitments, some programs received external

and international pressure to proceed quickly and were "“fast tracked"” by the Colombian Congress. For example, in a December 2016 ruling, the Colombian Constitutional Court granted fast-track implementation to the revised peace accord that was approved in late 2016, particularly as it applied to the FARC's disarmament and demobilization. In a 2017 ruling, however, the court determined that all legislation related to implementation of the accord needed to be fully debated rather than approved in an expedited fashion, which some analysts suggested slowed implementation significantly. ’s disarmament and demobilization. Other factors that became obstacles to quick implementation included efforts by the Duque government to revise the accord. In March 2019, the Duque