Colombia’s Changing Approach to Drug Policy

Colombia is one of the largest producers of cocaine globally, and it also produces heroin bound for the United States. Counternarcotics policy has long been a key component of the U.S.-Colombian relationship, which some analysts have described as “driven by drugs.” In recent years, Colombia revised its approach to counternarcotics policy, which may have implications for the U.S.-Colombian relationship going forward. On September 13, 2017, President Trump cited the recent spike in Colombia’s cocaine production as the reason he was reserving the option to decertify Colombia as a cooperating partner in fighting illegal drugs, an unexpected development given the close counternarcotics partnership between the United States and Colombia.

U.S. concerns about illicit drug production and trafficking in Colombia arose in the 1970s and grew significantly when Colombia became the dominant producer of cocaine in the Andean region in the mid-to-late 1990s. The United States has worked closely with Colombia to eradicate drug crops and combat trafficking. Simultaneously, since 2000, the United States has forged a partnership with Colombia—perhaps its closest bilateral relationship in Latin America—centered on helping Colombia recover its stability following a decades-long internal conflict with insurgencies of left-wing guerrillas and right-wing paramilitaries, whose longevity has been attributed, in part, to their role in the country’s illicit drug trade. Between FY2000 and FY2016, the U.S. Congress appropriated more than $10 billion of bilateral foreign assistance to support a Colombian-written strategy known as Plan Colombia and its successor programs. In addition to counternarcotics, the United States helped support security and development programs designed to stabilize Colombia’s security situation and strengthen its democracy.

A peace accord between the government of Colombia and the country’s main leftist insurgent group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), was signed in November 2016 after four years of formal peace talks. During protracted peace negotiations with the FARC, the Colombian government altered its approach to drug policy. A major change was the decision to end aerial spraying to eradicate coca crops, which had been a central—albeit controversial—feature of U.S.-Colombian counterdrug cooperation for more than two decades.

In addition, Colombia’s counternarcotics policies also shifted in 2015 to a public health approach. The shift was influenced by broader hemispheric trends to reform traditional antidrug practices in ways that proponents claim can reduce human rights violations. On the supply side, Colombia’s new drug policy gives significant attention to expanding alternative development and licit crop substitution while intensifying interdiction efforts. The revised drug policy approach promotes drug-use prevention and treatment for drug users. According to Colombian officials, the public health and prevention dimensions of the revised strategy will be led by Colombia’s Health Ministry, in coordination with other agencies.

In November 2016, Colombia’s Congress unanimously ratified the FARC-government peace accord, although some opponents boycotted that vote. The final accord was a revision following the narrow defeat of an earlier version of the accord in an October 2, 2016 referendum. The final peace agreement addresses important issues, such as illicit crop cultivation—a major source of FARC income—and rural development. According to President Juan Manuel Santos, the peace accord will draw former FARC members into efforts to counter illicit drug production and trafficking. In 2017, as Colombia began to implement the final peace accord and demobilize the FARC, the country is facing a large increase in cocaine production.

This report examines how Colombia’s drug policies have evolved in light of Colombia’s peace agreement with the FARC and its changing counternarcotics policy. It explores both policy and oversight concerns, such as

prospects for reducing coca and poppy cultivation under Colombia’s new drug policy and the peace accord with the FARC;

the role of Colombian drug trafficking organizations, including powerful criminal groups containing former paramilitaries, in a post-peace accord environment;

U.S.-Colombian cooperation on counternarcotics and Colombia’s future role in regional antidrug efforts; and

shifts in U.S. government assistance to support Colombia’s revised drug policy and how Colombia’s new policy converges with traditional U.S. priorities.

For additional background, see CRS Report RL34543, International Drug Control Policy: Background and U.S. Responses, by Liana W. Rosen; CRS Report R43813, Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations, by June S. Beittel.

Colombia's Changing Approach to Drug Policy

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Peace and Counternarcotics

- The Drug Trafficking Partial Agreement

- Colombia's 2015 Counternarcotics Policy: A Shift in Approach?

- Selected Elements of the Drug Strategy

- Coca Cultivation and Coca Eradication

- Eradication and U.S. Drug Policy

- Supply Reduction: Policy Alternatives to Aerial Eradication?

- Interdiction

- Alternative Development

- Colombia's Other Armed Groups and Future Drug Trafficking

- Policy Issues for Congress

- Funding Trends and U.S.-Colombian Counterdrug Cooperation

- State Department Counternarcotics Foreign Assistance

- Department of Defense Counternarcotics Authorities and Funding

- Colombia and Regional Counternarcotics Efforts

- Outlook

Summary

Colombia is one of the largest producers of cocaine globally, and it also produces heroin bound for the United States. Counternarcotics policy has long been a key component of the U.S.-Colombian relationship, which some analysts have described as "driven by drugs." In recent years, Colombia revised its approach to counternarcotics policy, which may have implications for the U.S.-Colombian relationship going forward. On September 13, 2017, President Trump cited the recent spike in Colombia's cocaine production as the reason he was reserving the option to decertify Colombia as a cooperating partner in fighting illegal drugs, an unexpected development given the close counternarcotics partnership between the United States and Colombia.

U.S. concerns about illicit drug production and trafficking in Colombia arose in the 1970s and grew significantly when Colombia became the dominant producer of cocaine in the Andean region in the mid-to-late 1990s. The United States has worked closely with Colombia to eradicate drug crops and combat trafficking. Simultaneously, since 2000, the United States has forged a partnership with Colombia—perhaps its closest bilateral relationship in Latin America—centered on helping Colombia recover its stability following a decades-long internal conflict with insurgencies of left-wing guerrillas and right-wing paramilitaries, whose longevity has been attributed, in part, to their role in the country's illicit drug trade. Between FY2000 and FY2016, the U.S. Congress appropriated more than $10 billion of bilateral foreign assistance to support a Colombian-written strategy known as Plan Colombia and its successor programs. In addition to counternarcotics, the United States helped support security and development programs designed to stabilize Colombia's security situation and strengthen its democracy.

A peace accord between the government of Colombia and the country's main leftist insurgent group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), was signed in November 2016 after four years of formal peace talks. During protracted peace negotiations with the FARC, the Colombian government altered its approach to drug policy. A major change was the decision to end aerial spraying to eradicate coca crops, which had been a central—albeit controversial—feature of U.S.-Colombian counterdrug cooperation for more than two decades.

In addition, Colombia's counternarcotics policies also shifted in 2015 to a public health approach. The shift was influenced by broader hemispheric trends to reform traditional antidrug practices in ways that proponents claim can reduce human rights violations. On the supply side, Colombia's new drug policy gives significant attention to expanding alternative development and licit crop substitution while intensifying interdiction efforts. The revised drug policy approach promotes drug-use prevention and treatment for drug users. According to Colombian officials, the public health and prevention dimensions of the revised strategy will be led by Colombia's Health Ministry, in coordination with other agencies.

In November 2016, Colombia's Congress unanimously ratified the FARC-government peace accord, although some opponents boycotted that vote. The final accord was a revision following the narrow defeat of an earlier version of the accord in an October 2, 2016 referendum. The final peace agreement addresses important issues, such as illicit crop cultivation—a major source of FARC income—and rural development. According to President Juan Manuel Santos, the peace accord will draw former FARC members into efforts to counter illicit drug production and trafficking. In 2017, as Colombia began to implement the final peace accord and demobilize the FARC, the country is facing a large increase in cocaine production.

This report examines how Colombia's drug policies have evolved in light of Colombia's peace agreement with the FARC and its changing counternarcotics policy. It explores both policy and oversight concerns, such as

- prospects for reducing coca and poppy cultivation under Colombia's new drug policy and the peace accord with the FARC;

- the role of Colombian drug trafficking organizations, including powerful criminal groups containing former paramilitaries, in a post-peace accord environment;

- U.S.-Colombian cooperation on counternarcotics and Colombia's future role in regional antidrug efforts; and

- shifts in U.S. government assistance to support Colombia's revised drug policy and how Colombia's new policy converges with traditional U.S. priorities.

For additional background, see CRS Report RL34543, International Drug Control Policy: Background and U.S. Responses, by Liana W. Rosen; CRS Report R43813, Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations, by June S. Beittel.

Introduction

Counternarcotics policy has been the defining issue in U.S.-Colombian relations since the 1980s because of Colombia's preeminence as a source country for illicit drugs.1 Peru and Bolivia were the main global producers of cocaine in the 1980s and early 1990s; however, successful efforts in reducing supply in those countries pushed cocaine production to Colombia, which soon surpassed both its Andean neighbors (see Figure 1).

Colombia emerged to dominate the global cocaine trade by the late 1990s. National concern about the crack cocaine epidemic and extensive drug use in the United States led to greater concern with Colombia as a source. At the same time, as Colombia became the largest producer of coca leaf and the largest exporter of finished cocaine, heroin produced from Colombian-grown poppies was supplying a growing proportion of the U.S. market.2 Alarm over the volumes of heroin and cocaine being exported to the United States was a driving force behind U.S. efforts to assist Colombia in addressing the drug problem.

Over the past 17 years, the United States and Colombia have forged a close security partnership, initially through a strategy called Plan Colombia, which was first funded by the U.S. Congress in 2000. Plan Colombia and its successor efforts laid the foundation for a strategic partnership aimed at enhancing security, lowering violence, fighting drugs and terrorism, and strengthening Colombia's democratic development.3 That partnership has broadened to include sustainable development, human rights, trade, regional security, and many other areas of cooperation.

Between FY2000 and FY2016, Congress provided more than $10 billion of foreign assistance from the U.S. Departments of State and Defense in support of Plan Colombia and its successor programs. The strategy received backing from Democratic and Republican Administrations and bipartisan support in Congress.

The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (known by its Spanish acronym, FARC), which has been defined as a foreign terrorist organization (FTO) by the U.S. government since 1997, and other armed groups in Colombia finance themselves through profits derived from drug trafficking. The lucrative drug trade in the 1990s had added new fuel to a multisided, decades-long internal armed conflict, featuring right-wing paramilitaries and a rural peasant-based insurgency.4 According to some analysts, the FARC took control of Colombia's resilient coca crop largely by dominating Colombia's impoverished countryside, where peasant farmers needed a cash crop, and by taxing traffickers. The FARC first became involved in the drug trade by levying protection fees on coca bush harvesters, buyers of coca paste and cocaine base, and cocaine processing laboratory operators in territory under FARC control. Over time, the FARC took a more direct role in owning and directing drug production and distribution.

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS). |

In 2012, the Colombian government opened peace talks with the FARC, receiving accolades from the U.S. government and most nations in the region for the effort to resolve the long-standing armed conflict through a political settlement. In February 2016, President Obama's Administration, anticipating a possible peace agreement between the government and the FARC, proposed a post-peace accord approach to U.S.-Colombian cooperation called Peace Colombia. The Administration's initiative requested $450 million of support to help implement any agreement, including foreign aid for reducing illicit drug production and trafficking, which built on bilateral cooperation established under Plan Colombia.5 Congress did not complete action on the foreign operations appropriations measure for FY2017 until May, when Congress passed the omnibus appropriations measure, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31), which essentially funded the foreign operations portion of Peace Colombia at $391.3 million. The Trump Administration's proposed foreign aid for Colombia in FY2018 for foreign operations would reduce funding to $251 million. In August, the House passed an omnibus appropriations bill for FY2018 (H.R. 3354) that would fund bilateral programs for Colombia at $335.9 million. Congressional passage of a continuing resolution (CR) through December 8, 2017, may be followed by another temporary CR before the 115th Congress determines the remainder of FY2018 foreign operations funding for Colombia.

In November 2016, the Colombian government and the FARC signed a historic peace accord that came on the heels of four years of formal peace talks and, 40 days earlier, the razor-thin defeat of an earlier peace accord in an October 2016 public referendum. The government of President Juan Manuel Santos, responding to the first accord's surprise defeat, quickly renegotiated the peace accord with the FARC. The Santos Administration maintained that the renegotiated agreement responded to some of the major concerns voiced by opponents of the first accord. The revised accord was approved by Colombia's Congress in late November 2016 (although some congressional opponents boycotted the final vote).

In 2017, the government began to implement the revised accord and demobilize FARC forces under the verification of a team of United Nations monitors.6 Data were published that demonstrated Colombia had seen a large increase in cocaine production in 2016. During the protracted peace talks with the FARC, the Colombian government altered its approach to drug policy and announced a new strategy (see "Colombia's 2015 Counternarcotics Policy: A Shift in Approach?," below). According to President Santos, the FARC-government peace accord had the potential to draw the once-powerful leftist guerrilla organization into the effort to counter illicit drug production and trafficking.

In April 2017, the FARC submitted to authorities a list containing the names of 6,804 FARC members who were concentrated in special disarmament zones. The group also provided a list of 1,541 urban militia members and agreed to provide another list with additional names.7 As months passed, better and more nuanced tallies became available. According to the International Crisis Group (ICG), some 11,200 FARC, including militia, combatants, and former FARC prisoners who were released, have demobilized. Others maintain the figure is higher and may exceed 12,000.8

Some members and units of the FARC, in an early act of defiance, stated they would not disarm. These members, closely affiliated with the drug trade, were rejected by the FARC central leadership as recalcitrant dissidents.9 Others, disillusioned by the government's failure to live up to its obligations during demobilization and reintegration, have slowly abandoned the peace process and left the encampments. Most recent estimates suggest that between 5% and 10% of the FARC who disarmed in 2017 have returned to illicit activities.10

Colombian authorities also are grappling with criminal groups, such as organizations that the government calls Bandas Criminales, or Bacrim, which many civil society groups see as successors to the rightist paramilitaries that demobilized between 2003 and 2006. The Bacrim have publicly announced plans to usurp FARC drug routes and gain control of cocaine trafficking. Press reports indicate that Bacrim leaders have advertised salaries to induce FARC combatants to reject demobilization and join their criminal businesses.11

Furthermore, a second rebel group, the National Liberation Army (ELN), also heavily involved in the drug trade, began formal peace talks with the Santos government in February 2017, in Quito, Ecuador. The ELN-government negotiations are similar to the FARC-government framework for peace talks, and yet the two sets of negotiations are also distinct in some important ways. Part of the difference lies in the distinct command structures of the two leftist guerrilla groups; whereas the FARC is controlled by a ruling secretariat, the ELN's structure is more horizontal, decentralized, and consensus based. The lead issue of the ELN negotiations will be "participation of society in constructing peace."12 In October 2017, the ELN and the Santos government started a three-month temporary ceasefire, the first bilateral ceasefire ever negotiated between the Colombian government and the ELN.

Peace and Counternarcotics13

President Santos launched formal peace talks with the FARC in October 2012. The FARC-government talks opened ceremonially in Norway and moved to Cuba in November 2012, where negotiating teams reached tentative agreements over the course of four years and some 50 rounds of talks on the following topics:

- land and rural development (May 2013);

- the FARC's political participation after disarmament (November 2013);

- illicit crops and drug trafficking (May 2014);

- victims' reparations and transitional justice (finalized in December 2015); and

- the demobilization and disarmament of the FARC and a bilateral cease-fire (June 2016).

One of the critical topics of the peace negotiations was the issue of controlling illegal crops and drug trafficking—a major source of FARC income. In May 2014, both sides appeared to resolve through a partial agreement, as the provisional elements of the final accord were called, the issue of trafficking and production of illegal drugs. Although the Santos Administration's counternarcotics policy changed in 2015 (see "Colombia's 2015 Counternarcotics Policy: A Shift in Approach?," below), the final peace accord, which was concluded in November 2016, remained largely unchanged from the May 2014 partial agreement on the topic of drugs.

The Drug Trafficking Partial Agreement14

On May 16, 2014, the peace talks between the FARC and the Colombian government reached a new draft, or partial agreement, on illicit crops and drug trafficking just days before the first-round presidential vote in which President Santos ran against an opposition candidate opposed to the peace process. The FARC and government negotiators announced their agreement on drugs to be enacted if a final agreement were signed by both parties, which committed them to work together to eradicate coca and to combat drug trafficking in the territories under guerrilla control.15

The partial agreement, entitled "The Solution to the Problem of Illicit Drugs," addressed coca eradication and crop substitution, public health and drug consumption, and drug production and trafficking. The negotiators reached six major areas of agreement:

- 1. FARC acknowledged its links to the drug business and committed to ending its involvement.

- 2. FARC agreed to assist with demining in rural areas to make drug crop eradication safer.

- 3. FARC agreed to cooperate "practically and efficiently" in resolving the illegal drugs problem.

- 4. The Colombian government agreed to prioritize voluntary drug-crop eradication over forced and aerial eradication.

- 5. The government committed to a crop substitution and alternative development program in line with the rural development accord reached in May 2013, the first topic resolved at the peace talks.

- 6. The government agreed to provide public health programs to prevent addiction and to treat drug consumption as a public health problem.16

Other partial agreements concluded over the course of the negotiations with the FARC also are relevant to drug policy. In December 2015, on the topic of victims' reparations and transitional justice, the FARC and the Colombian government announced they had redefined the "crime" of drug trafficking as it relates to past drug trafficking charges against the FARC or prior violations by the FARC during the internal conflict in a final partial accord.17 Colombia re-characterized the crime of drug trafficking in transitional justice parlance as a connected crime to the political act of insurgency. In other words, drug trafficking would be designated a political crime when used to support the FARC in its armed insurgency against the Colombian state (and therefore eligible for amnesty under the accord). Drug trafficking, if not combined with more severe violations, would no longer be a straightforward criminal violation of the penal code for eligible FARC fighters.

Some observers have speculated that the cessation of aerial spraying in Colombia could be viewed as an additional narcotics-related concession to the FARC during the course of the negotiations. Although not sanctioned by the accord, the issue of FARC combatants leaving the FARC and joining criminal groups after disarming, such as the remobilized paramilitaries have in recent years, raised the prospects of competing criminal groups taking control of FARC drug production and trafficking routes. Further, the same criminal bands, containing both leftist guerrillas and rightist paramilitaries—former enemies—might seek to go after the lucrative cocaine business working in tandem.

As noted below, the Santos government ended the use of the herbicide glyphosate to spray coca crops as part of a change in drug policy made in 2015. However, the May 2014 partial agreement, like the final accord ratified by the Colombian Congress in late 2016, leaves open the prospects in the future of aerial eradication of illicit crops. The Colombian government, however, had determined that reintroduction of coca crop aerial eradication would be made only as a "last-choice" option. In 2017, implementation of the FARC-government peace accord has increased the centrality of voluntary crop eradication and crop substitution and other livelihood alternatives as the major tools for supply reduction in combination with aggressive interdiction. In a public document released by the Colombian Embassy in Washington, DC, in March 2017, the Colombian government stated its commitment to fight drug trafficking with a focus on "working hand-in-hand with the United States to fight against illegal drugs, including strengthening interdiction capacity, fighting organized crime, and promoting alternative development."18

Colombia's 2015 Counternarcotics Policy: A Shift in Approach?19

Many observers have highlighted the apparent shift in Colombia's counternarcotics strategy in 2015 from a criminal justice and enforcement approach to one that potentially places drug policy within a broader public health framework. Some observers point to the Santos government's adoption of "harm reduction" drug policy rhetoric, which promotes reform of traditional antidrug practices in ways that reduces human rights violations. This reform approach has been advocated by some policymakers in both Europe and the Western Hemisphere. The Colombian government issued a four-page synopsis of the new drug policy approach in Spanish in September 2015.

On the supply side, Colombia's new drug policy gives significant attention to expanding alternative development and licit crop substitution to combat illicit drug production. In October 2015, after a finding by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a World Health Organization affiliate, that the herbicide used to aerially spray coca in Colombia "probably" causes cancer, the Santos Administration determined that Colombian law required the practice to be discontinued.20 Subsequently, in September 2015, the Colombian government released a new counternarcotics strategy, focused on several objectives:

- reduce drug-related crime and prioritize efforts to combat links in the drug-production supply chain;

- build capacity in cultivation zones or areas by focusing on social, economic, and political development; and

- enact an integrated approach to reducing drug consumption that emphasizes public health, human rights, and human development.

To accomplish these objectives, Santos laid out a strategy that included the following:

- social investment and institutional reform (e.g., construction of roads, provision of electricity and water utilities, and access to health care and education);

- crop substitution (e.g., food security programs and technical and financial assistance for households that abandon drug-crop cultivation);

- enhanced interdiction, investigations, and prosecutions (e.g., destruction of drug laboratories; seizure of cargoes and precursor chemicals; and effective detention of drug traffickers); and

- demand reduction through drug-use prevention and evidence-based treatment.

Coinciding with the release of the new drug strategy was the October 1, 2015, shuttering of the aerial eradication program, once a cornerstone of U.S.-supported drug control in Colombia. Viewed by some in Colombia and the United States as a crucial supply-control element, aerial spraying of coca crops with the herbicide glyphosate was no longer part of the Colombian government's counterdrug policy.

Colombia's revised antidrug strategy prominently featured a new government agency to be set up by December 2015 to implement a social program to assist coca growers, called the Agency for Alternative Development in Zones of Illicit Cultivation. The first director of the new agency, Eduardo Díaz Uribe, who was identified in the original four-page plan, would report directly to the President of Colombia. As of late 2016, the agency under Díaz was located inside the Office of the Presidency under Minister of Post-Conflict Rafael Pardo, where it was placed by decree earlier in the year.21 As the program was finally launched in February 2017, Díaz, whose title is now Director of Comprehensive Care on the Fight Against Drugs, announced that the government hoped to replace 50,000 hectares (ha) of illicit coca crops with legal crops in 2017 and that coca farmers would receive one-time payments to help provide food security and to help ensure that families can transfer quickly to alternative sources of income.22 The program began to make progress after May 2017 by brokering agreements with some 100,000 families (covering about 90,000 hectares of coca) but actual removal of the coca crops has not been as high as anticipated. Some analysts project that the voluntary removal of coca will be less than a third of the annual goal of 50,000 hectares by the end of 2017.

On crop substitution, the strategy explains that communities and individuals who now cultivate coca crops will be given an opportunity to commit to voluntarily eradicate their crops in exchange for development support. Additionally, if families abstain from drug-crop cultivation for five years, they would receive title to the land they occupy. Forced manual eradication by the government, however, remains a tool to assure compliance from those who do not commit to voluntarily removing their illicit crops. The document also includes a section on a special strategy to address drug cultivation in Colombia's national parks, a location where a significant portion of coca is now cultivated to evade aerial spraying, in addition to protected territories of Afro-Colombian and indigenous communities.23

The health and prevention orientation of the new strategy was to be led by the Ministry of Health, along with 10 other federal entities, which are to contribute to the National Plan for Use Prevention and Care. This approach aligns the Colombian strategy with harm-reduction approaches for curbing drug use that have been promoted by reform advocates who are critical of traditional counternarcotics, law enforcement-oriented tactics and policies. President Santos at times has expressed fundamental criticism of global narcotics-control approaches, since he was first elected President in 2010. He has not proposed that Colombia take the lead in experimenting with new ways to approach drug control. Nevertheless, he has strongly stated that Colombia has paid a very high price "in blood and treasure" for antidrug policies that have not been as effective as might have been anticipated given the level of sacrifice.

Many observers anticipate that the prospects for success of Colombia's new antidrug strategy depend on the outcome of the government's efforts to implement the peace accord. The State Department's International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, published in March 2017, maintained that "the new strategy constitutes a major component of the Colombian government's plans for the implementation of its final peace accord with the FARC."24 The level of the FARC's involvement following demobilization in 2017 remains uncertain.

At the 2016 Special Session of the United Nations General Assembly on the World Drug Problem, President Santos outlined his vision of peace and post-conflict reconciliation as it relates to drug policy. He underscored that although drug profits had funded the FARC for many decades, he foresaw a post-conflict environment in which the demobilized FARC (and possibly the smaller ELN) would join the fight against drugs and "become an ally in the eradication and substitution of illicit crops, and even assist with identifying former production centers and transportation routes."25

Selected Elements of the Drug Strategy

In addition to the emphasis on health and harm reduction approaches to drug policy, the Santos Administration's counterdrug strategy stresses enhanced interdiction and economic and social programs to encourage crop substitution by farmers, backed by enforced manual eradication of illicit crops if coca growers do not voluntarily eradicate. Although some analysts maintain that Colombia is on the cusp of a new, more peaceful stage, few believe it will be the end of drug production and trafficking in Colombia.

Coca Cultivation and Coca Eradication

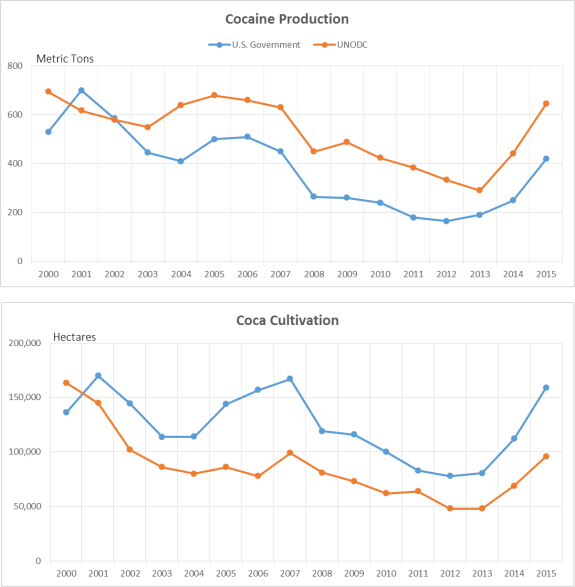

After significant year-on-year declines in coca cultivation in Colombia between 2007 and 2012, U.S. government estimates indicate that coca cultivation has been on the rise once more. Coca cultivation rose from 78,000 ha in 2012 to 159,000 ha in 2015 (the most cultivation since 2007). During this time, Colombia's coca cultivation increases drove higher production, according to most analysts, although evasion of drug-crop removal efforts and innovation to increase coca crop productivity also may have played an important role. According to U.S. estimates, Colombia produced 495 metric tons (mt) of pure cocaine in 2015 (see Figure 3).26

Between 2009 and 2013, Colombia aerially sprayed roughly 100,000 ha annually. In 2013, however, eradication efforts declined. Colombia aerially eradicated roughly 47,000 ha. It manually eradicated 22,120 ha, short of its manual-eradication goal of 38,500 ha.27 This reduction had a number of causes: the U.S.-supported spray program was suspended in October 2013 after two U.S. contract pilots were shot down, rural protests in Colombia hindered manual and aerial eradication efforts, and security challenges limited manual eradicators working in border areas.28 In 2013, Ecuador won an out-of-court settlement in a case filed in 2008 before the International Court of Justice in The Hague for the negative effects of spray drift over its border with Colombia.29

Despite its efforts, Colombia became the top producer of cocaine once more in 2014, and it remains one of three countries in the Andean region that produce nearly all of the world's supply of coca and cocaine, much of which is destined for the U.S. market. These trends are illustrated in Figure 2, which compares estimates by the U.S. government with those of the United Nations, in cooperation with national governments, of Colombia's cocaine production from 2000 to 2015 and illustrates the relationship to coca cultivation estimates from the two sources for the same period. The two sources track similar trends, and both the U.S. government and the UN reported a significant jump in illicit drug-crop cultivation (mainly coca) in Colombia in both 2014 and 2015.30

|

Figure 2. Historical Cocaine Production and Coca Cultivation in Colombia (data from the U.S. government and the U.N. Office of Drugs and Crime [UNODC]) |

|

|

Source: Cultivation data for years 2000-2015 from annual U.S. Department of State, International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR), volume 1, and from the U.N. World Drug Report. The production data are from the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, National Drug Control Strategy Data Supplement 2016, and White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, "ONDCP Releases Data on Cocaine Cultivation and Production in Colombia," at https://defenseoversight.wola.org/primarydocs/170314_colombia_coca.pdf. Notes: A hectare is a metric unit of 10,000 square meters equal to about 2.5 acres. U.S. and U.N. methodologies for coca cultivation and cocaine production differ and have changed over time, rendering comparisons of annual data problematic. UNODC typically has estimated lower coca cultivation levels but higher yield estimates of pure cocaine. Cultivation survey areas have expanded over time, and cloud cover in some years limited the accuracy of satellite imagery of coca fields. Conversion factors for estimating cocaine production also have changed, with some prior-year estimates retroactively recalculated. Future methodology changes may lead to revisions of data currently reported. |

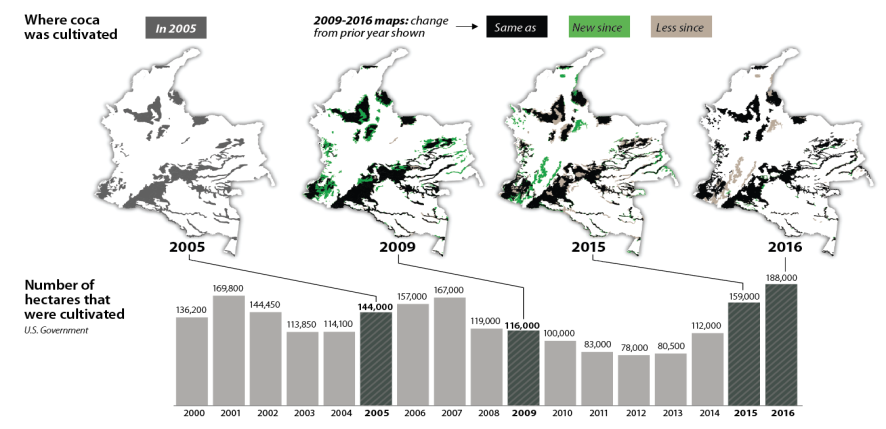

More recent data indicate that rising cultivation has resulted in a big surge in cocaine production. For 2015, the U.N. Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) reported 96,000 ha of coca were cultivated in Colombia,31resulting in 646 mt of potential pure cocaine, an estimated increase of 46%. By contrast, the U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy noted that its estimates of coca cultivation in Colombia in 2015—which reached 159,000 ha, or a 42% expansion over the year before—peaked in 2016 at 188,000 hectares in 2016 (see Figure 3).

U.S. estimates indicate that potential cocaine production grew significantly during the time frame that coincides with a drop in Colombia's total eradication (manual and aerial) from 137,894 ha eradicated in 2011 to 67,256 ha eradicated in 2014. Reporting on drug trends separately from the United States, the United Nations jointly with the Colombian government reported that 37,199 ha were aerially eradicated in 2015 (until October 1, 2015, when aerial eradication operations ceased) and 14,267 ha were eradicated by hand.32 In 2016, the first full year in which aerial eradication was not conducted, the Colombian government reported 17,642 ha of manually eradicated coca crops. Although views differ on whether this increase in cultivation and production was a direct result of lower eradication levels or of the Colombian government's engagement in peace talks with the FARC, key questions center on how the Colombian government will counteract these sharp increases.33

U.S. policymakers have expressed renewed concern over Colombia's drug production in the context of the historic peace accord with the FARC and changes to Colombia's counternarcotics strategy. According to the State Department, Colombia's manual eradication budget has declined by two-thirds since 2008 and the number of manual eradicators in 2016 declined by 90% compared to 2008.34 However, the Colombian government reportedly prepared for a manual eradication push in 2017 by training some 20,000 army troops to serve on eradication brigades.35

|

|

Source: Graphic by CRS. Map generated by Hannah Fischer using data from Environmental Systems Research Institute (Esri, 2014); Department of State (2017); personal communication with contacts at Department of State (2017). Cultivation data for years 2000 to 2015 from annual U.S. Department of State, International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR), volume 1, Colombia country reports, U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) for 2016 cultivation estimate https://defenseoversight.wola.org/primarydocs/170314_colombia_coca.pdf. Notes: The map depicts survey area boundaries, which are delineated around areas that are most likely to have coca cultivation. This is based on both historical data and new information. The map does not indicate density of coca crop cultivation. |

Eradication and U.S. Drug Policy

U.S. efforts to combat the production of illicit drugs, including cocaine, historically have relied on crop eradication as a key supply-control tool. Without drug cultivation, the State Department argued in 2007, "there would be no need for costly enforcement and interdiction operations."36 Eradication policies, however, have been politically fraught, particularly in Colombia. Until 2015, Colombia was the only country that permitted aerial spraying of herbicides to eradicate drug crops.

Both manual and aerial eradications (sprayings) were central components of Plan Colombia. Manual eradication, involving uprooting and killing the drug plant by teams of eradicators, was much more dangerous in the context of Colombia's long internal conflict, with scores of Colombian eradicators killed.37 Yet, aerial eradication by spray planes was always controversial because of the risk of spray drift to licit food crops and other potential or perceived health or environmental risks.38 Even though eradication—both aerial and manual—was less emphasized by the Obama Administration, as recently as FY2015 roughly 24% of the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) counternarcotics budget went to eradication, with most of that spent on eradication efforts in the Western Hemisphere.

Originally, Colombia's aerial eradication efforts focused on both coca and opium. When the country's opium crops declined by more than 90% between 2000 and 2009, the government shifted the focus of eradication efforts almost exclusively to coca.39

Many have questioned why a downward trend in drug cultivation and drug production in Colombia between 2007 and 2012 was not sustained and cultivation and production trends have instead reversed.40 Some analysts posit that without investment in rural development and projection of the state in remote areas (increasing state presence), any decrease in illicit crops cannot be sustained. Other factors that may have contributed to the large increases in coca bush cultivation in Colombia between 2014 and 2016 include the following:

- the FARC incited farmers to increase coca planting in anticipation of benefits from the government, such as crop substitution programs and credits;

- total eradication (number of hectares sprayed) has declined and counter-eradication efforts have become more effective in recent years;41

- the price of gold fluctuated—when gold prices increased, the FARC moved into illegal mining and encouraged coca farmers and others to engage in mining activities; however, when gold prices fell in 2013 and 2014, Colombian peasant farmers and the FARC reverted to more coca production; and

- cocaine demand ticked up in the U.S. and European market.42

|

Debate on the Herbicide Glyphosate to Eradicate Drug Crops Glyphosate is a broad-spectrum, nonselective post-emergence herbicide that is widely used worldwide for commercial and household application. Its historic use as the main herbicide applied in spray operations to eradicate coca in Colombia has generated long-standing controversy because of environmental and human health effects that continue to be debated, including in the U.S. and Colombian Congresses. In March 2015, the World Health Organization's (WHO's) International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) identified glyphosate as "probably" able to cause cancer in humans and classified it as a Group 2A carcinogen. The IARC's designation of glyphosate as a Group 2A carcinogen contributed to the Colombian government's decision to stop aerial eradication operations with glyphosate, which sparked tension between the Colombian Ministries of Health and Defense. However, some European and U.S. agencies have come to different conclusions regarding glyphosate. Several months after the IARC review was published, the European Food Safety Authority, an independent agency funded by the European Union, published a different assessment that glyphosate is "unlikely to pose a carcinogenic hazard to humans." As required by law, since the early 2000s the U.S. Department of State and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have repeatedly reviewed the scientific literature regarding glyphosate safety. All of these reviews generally have concluded that glyphosate exposure associated with aerial eradication in Colombia was not linked to adverse health outcomes in humans. Earlier EPA assessments of glyphosate had varied. In 1985, for example, the EPA classified glyphosate as "possibly carcinogenic to humans," but in 1991 the EPA changed its classification to "evidence of non-carcinogenicity in humans." Further fueling policy confusion over the appropriateness of glyphosate's use for drug-crop eradication, another review conducted by experts at the U.N.'s Food and Agriculture Organization and the WHO concluded in May 2016 that glyphosate is "unlikely to pose a carcinogenic risk to humans" when humans are exposed to the herbicide through food. The WHO explained that the conclusions by the joint group and by IARC were not contradictory, stating that the two groups' conclusions were "different, yet complementary" and that the IARC assessment focused on hazard while the joint group's review looked at risk. The debate in Colombia is likely to continue, as the Colombian government announced in early May 2016 that it would resume the use of glyphosate to eradicate coca crops but only in manual, ground-based operations. The decision to redeploy the application of glyphosate on coca crops came when 2015 cultivation data began to show a large uptick. The government's announcement to begin using glyphosate manually elicited public commentary that Colombia's policies on the herbicide's use were inconsistent and could incite future protests. In 2017, a press report indicated that aerial eradication may be resuming, but an official at the Embassy of Colombia in the United States confirmed this is not the Santos Administration's policy. Sources: See, for example, "Colombia Restarts Controversial Glyphosate Fumigation of Coca," Telesur, January 11, 2017; Brian Levesque, "Colombia Will Not Resume Aerial Coca Fumigation," Colombia Reports, September 6, 2016; Zachary P. Mugge, "Plan Colombia: The Environmental Effects and Social Costs of the United States' Failing War on Drugs," Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law and Policy, vol. 15, no. 2 (2004), pp. 309-340. |

The Colombian government's twin announcements in 2015 to end the controversial practice of spraying drug crops (primarily coca) with the herbicide glyphosate and adopt a new drug policy also may have contributed to the increase. Many analysts suggest that Colombian illicit crop farmers and cocaine and heroin producers reportedly use increasingly sophisticated ways to enhance productivity through eradication evasion strategies and other tactics. Policymakers in Colombia and the United States may choose to assess if the government's revised counternarcotics strategy, with its focus on rural development to reduce dependence on drug cultivation, enhanced law enforcement to interdict drugs and combat organized crime groups, and the public health approach to address domestic drug use, can bring the surge in cocaine production under control.

Supply Reduction: Policy Alternatives to Aerial Eradication?

Colombian policymakers maintain that the elimination of aerial spraying to destroy large volumes of coca can be compensated by increasing the government's focus on manual eradication, alternative livelihoods programming, and enhanced interdiction. Manual eradication, however, may remain cost prohibitive to implement in many parts of Colombia due to the continued threat of land mines and ongoing insecurity. Alternative livelihoods programs are long-term efforts whose fruits, sometimes literally, may not be borne out for years. Many proponents of coca eradication, whether aerial or manual, observe that it was never designed as a drug-control strategy to be effective in isolation. Most often, eradication was conceived as a program to be sequenced with alternative development. Some analysts maintain that effectively sequencing eradication with alternative development is the only way to sustainably lower coca cultivation.43

Interdiction

The Colombian government promotes the role of interdiction as a key element of its current counternarcotics policy. Colombia has committed to further enhancing interdiction's role and has a record of being a stalwart partner with the United States in interdiction. Such efforts include drug and precursor seizures; tracking of suspected illegal drug flights; capture of air- and watercraft used to convey illegal drugs; and use of specialized forces to dismantle laboratories and base camps, as well as to capture significant trafficking leaders. According to the United Nations, Colombia accounted for approximately 56% of cocaine seizures in South America and more than one-third of global cocaine seizures between 2009 and 2014.44

In 2016, Colombia seized 421 mt of cocaine and cocaine base (in 2015, Colombia seized 295 mt of cocaine).45 The State Department often cites Colombia's strong collaboration with the United States in bilateral maritime counternarcotics operations as a special area of strength. Historically, the State Department's Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement (INL) Affairs has supported Colombia's interdiction efforts. In the absence of aerial eradication, many analysts anticipate that supply-side reduction efforts will become more dependent on Colombian interdiction to mitigate outbound flows of cocaine, destined primarily for the United States.

Alternative Development

As elsewhere, significant time, even decades, may be required for rural development to succeed in regions of Colombia susceptible to illicit crop cultivation. Many analysts have suggested that Colombia's underdeveloped rural areas will require an infusion of resources to address the structural causes of poverty. These include a lack of access to land; a lack of access to land titling, irrigation, roads, and limited technical assistance in remote areas; in addition to the absence of national government or state presence—including basic services such as education and health—in rural zones which remain lawless and abandoned.

Under Plan Colombia, drug-crop eradication was carried out with a companion policy to provide licit alternatives, such as crop substitutes or alternative employment opportunities that were viable and sustainable. USAID funded and provided alternative development programs to assist communities to transition to licit livelihoods, although with extremely limited success. As part of the recently approved peace accord with the FARC, poor coca farmers in Briceño, Antioquia, participated in an alternative development program pilot (for further discussion, see textbox entitled "Alternative Development Pilot in Antioquia, Colombia, below).

The Colombian government and the FARC are promoting the planting of alternative crops, as the government previously did under Plan Colombia with U.S. support. USAID's Areas for Municipal Level Alternative Development (ADAM) and More Investment for Sustainable Alternative Development (MIDAS) projects aimed to reduce coca cultivation by expanding economic options for poor farmers between 2006 and 2011.46 ADAM implemented agricultural and infrastructure support activities, which included developing smaller-scale, licit crops with long-term income potential, such as cacao and specialty coffee. MIDAS, in coordination with the Colombian government, launched policy reforms to maximize employment and income growth. According to a 2010 audit, USAID's ADAM and MIDAS projects failed to provide secure alternate livelihoods for coca farmers on a sustainable basis. The programs did not contribute to a significant reduction of coca crop and cocaine production as a result. A major criticism of the ADAM and MIDAS programs was that the programs did not reach Colombian farmers who either grew coca or were susceptible to coca growing.47

Colombia's Plan de Consolidación Integral de la Macarena (PCIM), first implemented in 2007 in the department of Meta, was an alternative development pilot program under the Center for Coordination of Integral Action (CCAI). It was implemented by an office of the Colombian presidency under former President Álvaro Uribe. The pilot program, which received USAID support, depended on Colombian military and police to execute coca removal and eradication. First, the military and police would physically secure an area; then, they would eradicate coca crops, either voluntarily or involuntarily. Complementing the PCIM coca removal effort, the Colombian government provided two other programs: Familias en Acción and Familias Guardabosques, "both of which [were] designed to provide conditional cash transfers to least advantaged groups."48 Familias en Acción promoted childhood health and education; Familias Guardabosques encouraged local cooperation with drug eradication. Despite initial success in significant reduction of coca cultivation, PCIM was hindered by the bureaucratic position of the CCAI, a government agency that eventually was eliminated. According to one account, the CCAI was not in a position to command sufficient resources from the Colombian government for its programs and had to "cajole" actual line agencies to contribute from their budgets or personnel allocations.

Many factors contributed to alternative development failures during the ongoing armed conflict in Colombia, not least of which was the challenge of conducting programs during ongoing war insecurity. In addition, the Uribe government's "zero coca" policy, which required complete eradication of illicit crops as a prerequisite to receive support or development assistance for any alternative development project, posed a significant challenge to impoverished coca farmers. The certification process to ensure that farmers had uprooted their entire illicit crop often took an extended period of time, and then the alternative crops had to be cultivated for another period of time. In the interim, according to some analysts, peasant families were left without adequate provisions to feed themselves or acquire basic livelihoods.

|

Alternative Development Pilot in Antioquia, Colombia On June 10, 2016, the Colombian Government and the FARC announced a voluntary crop substitution pilot in Briceño, Antioquia. The pilot is managed by the FARC, the Colombian government, and the U.N. Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC). The framework for the pilot program is to consult with the local population on the community's crop-substitution program, offering participants a degree of participation. Colombia has experience with alternative development efforts that have incorporated local input into their design and implementation, such as crop-substitution programs to change from coca to cacao crops, coffee, or other agricultural products or retraining efforts to wean farmers from coca-planting livelihoods and prepare them for licit employment. Early critics of the pilot suggested the strategy would not be replicable in other parts of the country where the political, security, and cultivation dynamics are different. Some observers, weighing the pilot's modest progress since its 2016 launch, suggest that a successful program will require broader commitments, resources, and coordination from the government and its international partners. According to some activists and rights groups, the government has done little to ensure that peasants in Briceño have access to technical assistance and viable alternative economies necessary to supplant coca. Other observers, who saw eradication as one of many multifaceted factors involved in the construction of a long-lasting peace, argued that the government should balance the soft and hard aspects of voluntary eradication. The government, they say, should not squander opportunities to build social capital and trust with rural communities as it pursues its drug eradication, interdiction and other supply reduction goals. The Colombian government and the FARC have worked to implement measures that demonstrate political will and commitment to the draft agreements settled during the negotiations. For example, in mid-2015, both sides agreed to pilot a land-mine removal program in El Orejón, Antioquia, which was where the first jointly run effort by the Colombian government and the FARC was launched. El Orejón, located in the Briceño municipio ("county," in English), is 1 of 10 hamlets where the alternative development pilot program is taking place; thus, the demining and the alternative development program pilots overlap. The land-mine pilot ended in December 2016 with close to 20,000 square meters of terrain cleared. The alternative development pilot is expected to end in 2017. According to press reports, some 600 families have voluntarily eradicated an estimated 300 hectares of coca. Sources: Martin Jelsma and Coletta A. Youngers, "Coca and the Colombian Peace Accords: A Commentary on the Pilot Substitution Project in Briceño," WOLA, August 10, 2017; Juan David Ortiz Franco, "Acuerdo en la Habana para Sustituir Cultivos Ilícitos en Briceño, ¿Que Dicen los Campesinos?," Pacifista, June 13, 2016; Vanesa Restrepo, "En Briceño Concluyó Plan Piloto de Desminado Humanitario," El Colombiano, December 21, 2016. |

Colombia's Other Armed Groups and Future Drug Trafficking

The FARC is seen by most Colombians as a terrorist group that committed grave human rights violations and financed itself for decades with proceeds from illicit drugs, kidnapping, extortion, illegal mining, and other illicit businesses. As FARC combatants have demobilized, the opportunity for groups who remain armed to take on FARC's lucrative criminal enterprise appears to be quite attractive.49

Colombia has had many illegal groups that have benefited from narcotics trafficking, ranging from the large cartels of the last century—such as the Medellin Cartel led by Pablo Escobar in the early 1990s and the Norte Del Valle Cartel, which began in the 1990s but was not fully disarticulated by Colombian authorities until 2012—to the leftist insurgent groups, such as the FARC and ELN, and the rightist paramilitaries who joined together in the 1990s under the banner of the Self Defense Forces of Colombia. New and lesser-known criminal organizations, or cartelitos, also have entered aspects of Colombia's narcotics trade.

Some analysts posit that the growing threat from the paramilitaries, who controlled the largest share of the cocaine trade before entering peace negotiations with the government of former President Uribe and laying down their arms between 2003 and 2006, makes these groups and their successors the most likely to fill the criminal void left by demobilization of the FARC. The demobilization that followed the paramilitary peace process was not fully successful. If the largest drug trafficking organization in Colombia was the FARC, as some observers maintain, these other armed groups may compete to replace the FARC in its domination of the lucrative trafficking routes.

In Colombia, many paramilitaries remobilized into criminal groups called Bacrim. By 2013, a group that consisted of many former paramilitaries and was known by several names including Clan del Golfo, but most commonly as Los Urabeños, emerged as the dominant Bacrim. The group became a major target of enforcement by the Santos government.50 Los Urabeños nevertheless demonstrated an intent to replace the FARC in some parts of the country. It has openly advertised to recruit former FARC combatants who have declared themselves dissidents from the peace process.51

What can be done to prevent criminal groups such as Los Urabeños from asserting control over former FARC territory? If the FARC—or a significant portion of its organization—does demobilize and join the fight against drug trafficking in a post-accord situation, how can other armed groups not part of the peace process be prevented from taking the FARC's illegal drug businesses and other criminal enterprises? The nation's second-largest guerrilla group, the ELN, began formal peace talks with the Santos government in February 2017. Public support for the peace process guided by the Santos government with either group of leftist guerrillas remains mixed and ambivalent.52 Some analysts have stated that even if most FARC fighters conform to the peace accord, the percentage of FARC militants who remain in criminal endeavors could eventually exceed 25% of the total.53 Thus, the prospects for what some have dubbed "Facrim"—or FARC members who re-criminalize—may pose a significant future challenge. Given the expected delay in the FARC's full reintegration and the possibility that ELN talks will proceed slowly even if the current temporary ceasefire holds, the upcoming presidential and legislative campaigns aimed at Colombia's national elections in March and May 2018 (with a presidential runoff in June in needed) may expose the peace effort to intense domestic criticism.

Policy Issues for Congress

Colombia's partnership with the United States broadened during the years of Plan Colombia and its successor programs from a primary emphasis on counternarcotics, although also with significant programs addressing humanitarian concerns, such as justice reform and human rights, to a wider set of concerns. Over the course of Plan Colombia and its follow-on programs, and with bipartisan support in the U.S. Congress, social and economic programs assumed a more equally weighted emphasis and became part of a whole-of-government strategy with benefits that included greater economic stability, protection of human rights, decreased violence, and increased investment and trade. Plan Colombia was initially part of a regional framework, the Andean Counterdrug Initiative, which also funded programs in neighboring countries such as Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela. Many observers viewed Plan Colombia as a model for U.S. foreign policy in the region, and some saw it as an example of effective state capacity building and counterterrorism.54

In terms of drug-control policy and reducing drug supply, however, many analysts considered Plan Colombia's successes limited. As the Colombian government implements the peace accord with the FARC, whose insurgency was fueled by the drug trade, the U.S. Congress may consider how to evaluate the newer "post-Plan Colombia" counterdrug approach, including such issues as eradication of drug crops, alternative development, and interdiction. The final peace accord with the FARC, ratified in November 2016 by the Colombian Congress, returned aerial spraying to the government's antidrug armory. Nevertheless, force eradication was defined as a last option after voluntary methods proved unsuccessful. Policymakers also may consider the potential costs and effectiveness of alternative development and enhanced interdiction.

Additionally, U.S. policymakers may assess the likelihood of FARC-dominated coca cultivation and trafficking shifting to other Colombian criminal organizations. Key questions remain: Will there be a violent battle of succession among criminal groups? To what degree can and should Colombia's role in regional counternarcotics efforts be expanded? Will U.S. and Colombian drug control objectives continue to align? And to what degree will counternarcotics appropriations by the 115th Congress for the Departments of State and Defense, as well as USAID, synchronize with and support a newer Colombian counterdrug strategy?

Funding Trends and U.S.-Colombian Counterdrug Cooperation

State Department Counternarcotics Foreign Assistance

According to the State Department, Colombia received an estimated $87.7 million in FY2016 for counternarcotics assistance. The Obama Administration's budget request for FY2017 sought to provide continued counternarcotics assistance to Colombia, including some $95 million in Foreign Military Financing, International Military Education and Training, and International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) for reducing drug production and coca cultivation, as well as to combat illicit activities and organized crime. Colombia's counternarcotics efforts in the area of alternative development to replace illicit crops with licit crops also are supported by USAID's Economic Support Fund account, which included about $30 million in the FY2017 request for rapid-response efforts, such as support to Colombia's new agency for the substitution of illicit crops.

As part of the ongoing State Department-funded assistance to Colombia, INL has sought to adjust its counternarcotics efforts to Colombia's "post-FARC" drug policy objectives. Following the cessation of aerial eradication in 2015, the State Department sought to shift funding previously allocated for such purposes, including aircraft assets, to other counternarcotics activities. According to the State Department, key areas of ongoing and future counternarcotics programming with INCLE funds include (1) enhanced land and maritime interdiction; (2) rural police support; (3) manual eradication support; (4) environmental monitoring; and (5) aviation, including helicopter airlift for rural police support and manual eradication. INL is also seeking to repurpose several of the aircraft previously used for spray operations for drug-related detection and monitoring. Some aircraft may be fitted with cameras to provide real-time imagery to monitor coca growth and related cease-fire commitments.

Department of Defense Counternarcotics Authorities and Funding

Congress has provided the Department of Defense (DOD) with several counternarcotics-related authorities, including some that specifically authorize DOD to conduct counternarcotics activities in Colombia. In the past, DOD has provided Colombia with a range of training, equipment, and other support for counterdrug purposes, including nonlethal protective and utility personnel equipment, such as navigation equipment, secure and nonsecure communications equipment, radar equipment, night vision systems, vehicles, aircraft, and boats.55 The FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA; P.L. 114-328) significantly revised DOD's authorities to support foreign security forces through security cooperation, which includes DOD's counterdrug efforts. The extent to which those changes will affect DOD's support to Colombia for counternarcotics purposes remains to be seen, as DOD's implementation of these new authorities proceeds.

The primary purpose of the FY2017 NDAA provisions was to clarify, rationalize, and improve upon a legal framework for DOD security cooperation that many considered too complex and unwieldy for effective planning and execution. With respect to counternarcotics policy, however, analysts are exploring whether the reforms may modify both the scope of authorities available for DOD to conduct counterdrug activities with foreign partners and the availability of funding allocated for counterdrug purposes. Originating in a provision in the 2002 Supplemental Appropriations Act for Further Recovery From and Response to Terrorist Attacks on the United States (P.L. 107-206, §305), Congress also authorized DOD to use counternarcotics funds designated for Colombia for a unified campaign against both narcotics trafficking and terrorism. The provision, most recently extended through FY2019 in the FY2017 NDAA (§1013), further outlines numerical and participation limitations for U.S. personnel on assignment in Colombia pursuant to this authority. The FY2018 NDAA (H.R. 2810), as passed by Congress and cleared for signature by the President on November 16, 2017, further extended this authority to FY2022 (§1011).

Some analysts have speculated on whether the applicability of DOD's authority to support a unified campaign in Colombia against both narcotics trafficking and terrorism would change if the FARC were to be delisted as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO).56 To this end and in light of Colombia's peace deal with the FARC, the Senate version of the FY2018 NDAA also sought to modify the authority to support a unified campaign against "other illegally armed groups" and expand the authority to include support for efforts to demobilize, disarm, and reintegrate their members; these changes ultimately did not pass. If the FARC were to be delisted, this authority conceivably could continue to be used in Colombia but DOD may choose to focus its efforts against the ELN, which remains designated as an FTO by the State Department. What is not clear, however, is how or whether resources, personnel, and the scope of activities in Colombia would be adjusted in light of a potential FARC delisting. The beginning of talks with the ELN on February 7, 2017, may present a further challenge to DOD to limit its use of this authority.

Colombia and Regional Counternarcotics Efforts

In 2012, then-President Obama and President Santos announced a new joint endeavor, the U.S.-Colombia Action Plan on Regional Security Cooperation (USCAP) at the Sixth Summit of the Americas, hosted by Colombia. This joint effort, built on ongoing security cooperation, addresses hemispheric challenges, such as combating transnational organized crime, bolstering counternarcotics programs, strengthening legal institutions and the rule of law, and fostering resilient communities.57

The action plan focuses on capacity building for security personnel in Central America and the Caribbean conducted by Colombian security forces (both Colombian military and police). To carry out the plan, Colombia undertook 39 activities in 2013 that trained more than 700 individuals from Panama, Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. In 2014, Colombia conducted 152 activities and reportedly trained more than 3,500 security personnel from the same four countries, in addition to Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic. In 2015, under the USCAP, the same six countries received training for more than 3,300 of their security forces; and, in 2016, another 271 activities took place resulting in more than 11,000 trainees over the four years of the program.

USCAP trainings made up about one-fourth of all trainings of third-country security personnel provided by Colombian police and military. Colombia has trained military and police from other countries, both under the USCAP partnership and via other arrangements, totaling more than 30,000 security personnel from over 70 countries, with most located between Colombia and the United States. According to the U.S. and Colombian governments, the goals of the training by Colombian forces are to "export" Colombian expertise in combating crime and terrorism and to promote the rule of law and increase bilateral and multilateral law enforcement cooperation. Critics of the effort to "export Colombian security successes" maintain that human rights concerns have not been adequately addressed.58

Some observers are concerned that the portion of these trainings funded by the U.S. government may lack transparency and circumvent congressionally imposed human rights restrictions on U.S.-funded security cooperation.59 Advocates for Colombian training efforts maintain that the Colombian national police and armed forces are among the most highly trained and experienced in the region and that the professionalization of Colombian forces is an important asset to be shared in a region challenged by drug trafficking, crime, and related violence.

In late 2017, Colombian Vice President Óscar Naranjo met with several advisers to President Donald Trump during a trip to Washington, DC, including Rich Baum, acting director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP); head of the Department of Homeland Security, Elaine Duke, and Vice President Mike Pence. During his meeting with the U.S. officials, Vice President Naranjo proposed creating a naval task force to buttress maritime drug interdiction efforts. "This is a strategy with three purposes: to increase interdiction efforts on the high seas, increase interdiction efforts of speedboats and semi-submersibles on the Pacific and have greater control over fluvial access to the Pacific Ocean. We are talking about an operation to cover the waterways, gather intelligence and increase the capacity for interdiction," stated Naranjo. He added among the issues discussed with Pence and other representatives of U.S. agencies and Congress, was Colombia's commitment to raise levels of interdiction of drugs and chemical precursors and to the advance the removal of illicit crops.60

Outlook

The success of Colombia's new national drug strategy may depend on how the peace accord with the FARC is enacted. Peace or post-conflict efforts involve a broad spectrum of development programs and other activities which could influence, in turn, political stability, economic growth, and management of drug trafficking and other crime.

Although some observers maintain that the scale of FARC trafficking will decline in post-accord Colombia, it is uncertain how many former FARC combatants will defect or decline to participate in post-accord programs. The FARC and other armed groups in the country financed themselves with drug profits and other illicit businesses, and the Colombian drug trade likely will continue to meet large international—and particularly U.S.—drug demand. As discussed, other Colombian drug traffickers have aggressively sought to supplant the FARC, which is estimated to have once controlled roughly 60% to70% of Colombia's coca-growing areas and lucrative trafficking routes, according to government statements and recent studies.61

Some analysts have estimated that the process of executing programs related to post-accord and post-conflict development could take more than a decade and cost as much as $42 billion. The country faces steep challenges to underwrite the post-accord peace programs in an era of declining budgets as it seeks to address reparations and land restitution for more than 8 million conflict victims; modernize and expand Colombia's justice system; and effectively carry out transitional justice (including full confessions, punishment, and reparations to victims and communities) for crimes by both the FARC and the Colombian security forces, as required by the peace accord. The informal campaigning and positioning for the 2018 national elections in Colombia may result in the government's drug policy being critically evaluated by those who continue to oppose the peace process with the leftist guerillas and may be profoundly affected by the president who is to take office in August 2018.

Colombia is working to achieve peace with low government reserves, a weakened currency, and the unknowns of future external foreign aid or assistance.62 The cost and challenge of bringing social services to vulnerable, often-isolated parts of the country that are subject to violence and drug-crop production include effectively removing land-mines in the second-most land-mine-affected country in the world, and overcoming a historic dearth of transportation and other infrastructure. Many observers contend that these legal, security, and social conditions must be addressed for viable crop substitution and sustainable alternative livelihood programs to succeed. Some observers raise concerns that without adequate external financial support, the Colombian government's capacity to finance alternative livelihood programs and build the socioeconomic conditions to assist rural communities to move away from a dependence on illicit crops over the next decade is quite precarious.63

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Research Associate Edward Gracia contributed significantly to this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

During the 1980s, Colombian cocaine trafficking organizations, including the Medellin and Cali Cartels, grew to notoriety. Subsequently, Colombia became the center of coca cultivation and processing as well as the primary global source of processed cocaine. |

| 2. |

According to State Department testimony, by 2001 Colombia was providing 22% to 33% of the heroin consumed in the United States (slightly over 4 metric tons [mt]). Testimony of Paul E. Simons, Acting Assistant Secretary of State for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, in U.S. Congress, House Committee on Government Reform, America's Heroin Crisis: The Impact of Colombian Heroin and How We Can Improve Plan Colombia, hearing, 107th Congress, 2nd sess., December 12, 2002 (Washington, DC: GPO, 2003). |

| 3. |

For more information, see CRS Report R43813, Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations, by June S. Beittel. |

| 4. |

Nick Miroff, "Colombia Is Preparing for Peace. So Are Its Drug Traffickers," Washington Post, February 2, 2016. |

| 5. |

White House, "Fact Sheet: Peace Colombia—A New Era of Partnership Between the United States and Colombia," February 4, 2016, at https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2016/02/04/fact-sheet-peace-colombia-new-era-partnership-between-united-states-and. |

| 6. |

For more on 2017 implementation measures, see CRS Report R43813, Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations, by June S. Beittel. |

| 7. |

Rafael Guarin, "Cuál Desarme de las Farc?," Semana, April 6, 2017, http://www.semana.com/opinion/articulo/para-que-no-haya-repeticion-se-debe-garantizar-el-desarme-total-de-las-farc/521189. |

| 8. |

"Ya son 4.011 los Acreditados de las Farc por Renuncia a las Armas," El Tiempo, June 15, 2017, http://www.eltiempo.com/politica/proceso-de-paz/el-comisionado-de-paz-acredita-a-milicianos-de-las-farc-99350. |

| 9. |

Mimi Yagoub, "'No nos Desmovilizaremos': Primeros Disidentes de las FARC no Serán los Últimos," InSight Crime, July 8, 2016, http://es.insightcrime.org/analisis/no-nos-desmovilizaremos-primeros-disidentes-farc-seran-ultimos. |

| 10. |

For discussion, see James Bargent and Camilo Mejia, "Can Colombia and the FARC Stumble Their Way to Lasting Peace?," World Politics Review, February 28, 2017; Angelika Albaladejo, "Is Colombia Underestimating the Scope of FARC Dissidence," InSight Crime, October 17, 2017. |

| 11. |

Tristan Clavel, "Colombia's Urabeños Recruiting Dissidents from FARC Peace Process," InSight Crime, January 26, 2017. |

| 12. |

Sebastian Bernal and Geoff Ramsey, "Colombia's ELN Peace Talks Explained," Washington Office on Latin America, February 7, 2017. |

| 13. |

For more background, see CRS Report R42982, Colombia's Peace Process Through 2016, by June S. Beittel. |

| 14. |

A partial agreement was one term used to mean a provisional agreement on an element of the peace talks before the entire agreement between the FARC and the government was concluded and signed. |

| 15. |

Drawn from "Peace Talks Between the Colombian Government and FARC: Agreement on the Third Point Under Discussion Drug Trafficking," fact sheet, May 2014, provided to CRS by the Colombian Embassy. |

| 16. |

For more background on the agreement on illicit drugs, see John Otis, The FARC and Colombia's Illegal Drug Trade, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, November 2014. Washington Office on Latin America drug policy analyst Coletta Youngers describes the agreement as taking an economic development approach, with local decisionmaking, participation, and planning to develop locally appropriate crop substitution or alternative livelihoods programs. While highlighting that the framework outlined in the agreement is positive, she notes that the failure to recognize the need to allow some coca cultivation until alternative sources of income are put in place and the very short time frame contemplated in the accord are unrealistic. She also cites the agreement's endorsement of voluntary eradication over forced eradication and aerial spraying of drug crops as positive elements that, if the accord is implemented, will represent a significant shift in the government's current drug control strategy (CRS interview, February 2015). |

| 17. |