Turkey (Türkiye): Major Issues and U.S. Relations

Changes from October 18, 2019 to November 8, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- Turkey's Strategic Orientation

- Overview

- Effect of Tensions on U.S./NATO Cooperation

- Syria and October 2019 Incursion

- U.S. Sanctions and Other Actions

in Light of OPS - Executive Order 13894 and Other Administration Measures

- Congressional Action and Possible Additional Sanctions

- Administration Sanctions

- Possible Congressional Sanctions and Other Actions

- Effect on Turkish Behavior?

- Other Possible U.S. Options and NATO Implications

- Turkey's S-400 Acquisition from Russia

- Removal from F-35 Aircraft Program

- CAATSA Sanctions?

- Turkey's Rationale and Implications for NATO

- Relevant U.S. Legislation

- Domestic Turkish Developments

- Political Developments Under Erdogan's Rule

- Economic Status

Figures

Summary

Some specific Turkish actions have raised questions about Turkey's commitment to NATO and overall strategic orientation. In 2019, Turkey's incursion into northeastern Syria and acceptance of components for a Russian S-400 surface-to-air defense system have brought bilateral tensions to crisis levels, and contributed to Trump Administration sanctions on Turkey and the possibility of additional sanctions or other actions from Congress. Events in Syria and a 2016 coup attempt in Turkey appear to have led Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to act more independently from the United States and cultivate closer ties with Russia and its President Vladimir Putin.

Turkey faces a number of political and economic challenges that inform its relations with the United States. Observers voice concerns about Erdogan's growing authoritarianism, and question how he will govern a polarized electorate and deal with the foreign actors who can affect Turkey's financial solvency and regional security. To meet its security, economic, and energy needs, Turkey cooperates with the United States and several other countries whose respective interests may conflict. Without significant rents from natural resources, Turkey's economic performance is largely dependent on maintaining diversified global trade and investment ties, including with the West. The following are major points of concern in the U.S.-Turkey relationship.

Turkey's October 2019 incursion into northeastern Syria. Events in Syria have fed U.S.-Turkey tensions, particularly regarding Kurdish-led militias that partnered with the United States against the Islamic State over Turkey's strong objections. Those Kurdish-led militias have links with the PKK (Kurdistan Workers' Party), a U.S.-designated terrorist organization that originated in Turkey and has waged an on-and-off insurgency against the Turkish government while using refuges in both Syria and Iraq. In October 2019, Turkey's military (and allied Syrian opposition groups) entered northeastern Syria after President Trump ordered a pullback of U.S. Special Forces shortly after a call with President Erdogan. The declared aims of what Turkey callscalled Operation Peace Spring (OPS) arewere to target "terrorists"—both the Kurdish-led militias and the Islamic State, or (IS/ISIL/ISIS)—and create a "safe zone" for the possible resettlementreturn of some of the approximately 3.6 million Syrian refugees in Turkey. After TurkeyTurkish-led forces gained control of some largely Arab-populated sectors of Syria previously controlled by Kurdish-led militias, the Kurds reportedly reached arrangements with Syria's government that may allow it to regain control over much of northeastern Syria—raising several questions about Syria's future, including how to prevent an IS resurgencea U.S.-facilitated cease-fire and Turkey-Russia agreement have provided for a primarily Turkish-patrolled safe zone in those sectors, as well as Russian-Syrian help in removing Kurdish-led militias from other border areas east of the Euphrates, raising several questions about Syria's future.

U.S. sanctions and other U.S./NATO actions or options in light of OPS. Via Executive Order 13894 on October 14, theThe Trump Administration authorized various sanctions on Turkey and actors transacting with it in connection with OPS. The Treasury Department designated for sanctions key Turkish ministers and ministries (including defense and energy), and it has broad authority to designate other actors. This authority, along with other U.S. actions affecting bilateral trade, may be intended to encourage a diplomatic resolution. Vice President Pence helped arrange for a conditional pause in OPS on October 17 that, if it becomes a permanent halt, would allow for a Turkish-patrolled safe zone and a reversal of U.S. sanctions designations. Some Members of Congress have introduced bills seeking stronger sanctions against Turkey in response to OPS, including on U.S. and foreign arms transactions and on Turkish financial institutions. On October 16, the House passed H.J.Res. 77—a resolution condemning both OPS and some Administration actions—by a vote of 354-60imposed sanctions on some Turkish cabinet ministries and ministers in response to OPS, but lifted them upon announcing a permanent cease-fire on October 23. The executive order authorizing sanctions against Turkey remains in effect. On October 29, the House passed the Protect Against Conflict by Turkey Act (H.R. 4695) by a vote of 403-16. H.R. 4695 could require the imposition of sanctions on some Turkish officials, U.S. and foreign arms transactions with Turkey, and Turkish financial institutions. On the same day, the House (by a vote of 405-11) also passed a nonbinding resolution characterizing actions by the Ottoman Empire (Turkey's predecessor state) against Armenians from 1915 to 1923 as genocide. The prospects of sanctions legislation in the Senate are unclear, as is how sanctions might affect Turkey's economy, public sentiment, and patterns of trade and defense procurement. The crisis over OPS has fueled speculation about the future of allied cooperation with Turkey within NATO, specifically regardingincluding the status of reported U.S. military assets—such as possible tactical nuclear weapons—in Turkey. Separately, on October 16, a U.S. Attorney's office indicted Turkey's Halkbank (which is majority-owned by Turkey's government) for violations of U.S. laws relating to Iran sanctions, in a case that has been pending for years and is sensitive for President Erdogan.

S-400 acquisition from Russia, removal from the F-35 program and possible sanctions. Shortly after Russia began delivering an S-400 air defense system to Turkey in July 2019, the United States announced that Turkey would not receive the 100 F-35 aircraft it had planned to purchase and would no longer manufacture components for F-35s. U.S.-Turkey tensions on the issue could have broad implications for defense cooperation, bilateral relations, and Turkey's role in NATO. The S-400 deal also could trigger U.S. sanctions under existing law. According to some reports, President Trump may delay sanctions while pursuing a deal potentially allowing Turkey to remain in the F-35 program if it (1) agrees not to use the S-400 and (2) acquires a U.S. Patriot air defense system. In July, President Erdogan reportedly threatened to retaliate against S-400-related sanctions, including by withdrawing Turkey from NATO and ejecting the United States from Incirlik Air Base.

Introduction

This report provides background information and analysis on the following topics:

- Turkey's strategic orientation toward the United States and Russia, and how that affects Turkish cooperation with the United States and NATO;

- Turkey's October 2019 incursion into Syria, including the effect on Syrian Kurds who have helped the United States counter the Islamic State (IS/ISIL/ISIS);

- Trump Administration sanctions and

other actionstheir reversal, possibleadditionalsanctions from Congress, and other options after Turkey's October incursion into Syria; Issuesissues surrounding Turkey's purchase of a Russian S-400 surface-to-air defense system, its removal from the F-35 aircraft program, and possible sanctions under existing legislation.; and

Domesticdomestic Turkish developments, including politics under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's largely authoritarian and polarizing rule, and some economic concerns.

For additional information, see CRS Report R41368, Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas. See Figure A-1 for a map and key facts and figures about Turkey.

Turkey's Strategic Orientation

Overview

Numerous points of tension have raised questions within the United States and Turkey about the two countries' alliance, as well as Turkey's commitment to NATO and a Western orientation. For their part, Turkish leaders may bristle because they feel like Turkey is treated as a junior partner, and they arguably have sought greater foreign policy diversification through stronger relationships with more countries.1

A number of complicated dynamics drive Turkey's international relationships. Turkey's history as both a regional power and an object of great power aggression translates into wide popularity for nationalistic political actions and discourse.2 Moreover, Turkey's cooperative relationships with countries whose respective interests may conflict involve a balancing act. Threats from Syria and Iraq and the regional roles of the United States, Russia, and Iran further complicate Turkey's situation. Also, lacking significant rents from natural resources, Turkey's economic performance is largely dependent on maintaining diversified global trade and investment ties, including with the West.

Concerns among Turkish leaders that U.S. policy might hinder Turkey's security date back at least to the 1991 Gulf War,3 but the following developments have fueled them since 2010:

- Close U.S. military cooperation against the Islamic State with Syrian Kurdish forces linked to the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), a U.S.-designated terrorist organization that has waged an on-and-off insurgency against the Turkish government since the 1980s while using refuges in both Syria and Iraq.

- Turkey's view that the United States supported or acquiesced to events during post-2011 turmoil in Egypt and Syria that undermined Sunni Islamist figures tied to Turkey.

- Many Western leaders' criticism of President Erdogan for ruling in an increasingly authoritarian manner. Erdogan's sensitivity to Western concerns was exacerbated by a 2016 coup attempt that Erdogan blames on Fethullah Gulen, a former Turkish imam who leads a worldwide socioreligious movement and lives in the United States.

Turkey has thus arguably sought a more independent course than at any time since joining NATO in 1952, perhaps partly in response to Turkey's concerns that some U.S. policies might not serve its interests. Despite having a long history of discord with Russia, including some ongoing disagreements about Syria and Libya, Turkey may be disposed to cooperate more with Russia in hopes of reducing threats that Turkey faces, influencing regional political outcomes, and decreasing Turkey's military and economic reliance on the West. After reaching a low point in Turkey-Russiaa low point was reached in Turkish-Russian relations in 2015-2016 (brought about by the Turkish downing of a Russian plane near the Turkey-Syria border and Russia's temporary imposition of sanctions), Erdogan and Russian President Vladimir Putin have cultivated closer ties. Putin showed support for Erdogan during the 2016 coup attempt, and subsequently allowed Turkey to carry out military operations in northern Syria over the next two years that helped roll back Kurdish territorial control and reduce refugee flows near Turkey's border.4

Effect of Tensions on U.S./NATO Cooperation

Turkey's location near several global hotspots has made the continuing availability of its territory for the stationing and transport of arms, cargo, and personnel valuable for the United States and NATO. From Turkey's perspective, NATO's traditional value has been to mitigate its concerns about encroachment by neighbors. Turkey initially turned to the West largely as a reaction to aggressive post-World War II posturing by the Soviet Union. In addition to Incirlik Air Base near the southern Turkish city of Adana, other key U.S./NATO sites include an early warning missile defense radar in eastern Turkey and a NATO ground forces command in Izmir (see Figure A-2). Turkey also controls access to and from the Black Sea through its straits pursuant to the Montreux Convention of 1936.

Current U.S.-Turkey tensions have fueled discussion from the U.S. perspective about the advisability of continued U.S./NATO use of Turkish bases. As a result of the tensions and questions about the safety and utility of Turkish territory for U.S. and NATO assets, some observers have advocated exploring alternative basing arrangements in the region.5 The Trump Administration reportedly reduced the U.S. military presence at Incirlik in 2018 while contemplating broader reductions in Turkey.6 While an August 2018 report cited a Department of Defense (DOD) spokesperson as saying that the United States was not leaving Incirlik,7 some reports suggest that expanded or potentially expanded U.S. military presences in Greece and Jordan might be connected with concerns about Turkey.8

There are historical precedents for such changes. On a number of occasions, the United States has withdrawn military assets from Turkey or Turkey has restricted U.S. use of its territory or airspace. Most prominently, Turkey closed most U.S. defense and intelligence installations in Turkey during the 1975-1978 U.S. arms embargo that Congress imposed in response to Turkey's military intervention in Cyprus.

Assessing costs and benefits to the United States of a U.S./NATO presence in Turkey, and of potential changes in U.S./NATO posture, largely revolves around two questions:

- How important is U.S./NATO support to Turkey's external defense and internal stability, and to what extent does that support serve U.S. interests?

- To what extent does the United States rely on direct use of Turkish territory or airspace to secure and protect U.S. interests?

Syria and October 2019 Incursion

The overall conflict in Syria presents both challenges and opportunities for Turkey (see Appendix B for a timeline of Turkey's involvement). Turkish-led forces have occupied and administered some parts of northern Syria since 2016,. Turkey's chief objective has been to thwart the PKK-linked Syrian Kurdish People's Protection Units (YPG) from establishing an autonomous area along Syria's northern border with Turkey. Turkish-led military operations to that end have included the U.S.-supported Operation Euphrates Shield (August 2016-March 2017) against an IS-controlled area in northern Syria, and Operation Olive Branch in early 2018 directly against the Kurdish enclave of Afrin. Turkey has considered the YPG and its political counterpart, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), to be the top threat to Turkish security because of Turkish concerns that YPG/PYD gains have emboldened the PKK in Turkey.9 Shortly after the YPG/PYD began achieving military and political success with its leading role in what became the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)—an umbrella group including Arabs and other non-Kurdish elements that became the main U.S. ground force partner against the Islamic State in 2015—Turkey-PKK peace talks broke down, tensions increased, and occasional violence resumed within Turkey.

In October 2019, Turkey's military attacked some SDF-controlled areas in northeastern Syria after President Trump ordered a pullback of U.S. Special Forces shortly afterfollowing a call with President Erdogan. In the previous months, joint U.S.-Turkey ground patrols had monitored the border area and some YPG fortifications were dismantled, but Turkish leaders repeatedly criticized the United States for not doing enough to secure the removal of the YPG from the border area.10 The declared aims of what Turkey callscalled Operation Peace Spring (OPS) arewere to target "terrorists"—both the YPG and the Islamic State—and create a "safe zone" for the possible resettlementreturn of some of the approximately 3.6 million Syrian refugees in Turkey.11 The ground component of the Turkish operation—as during previous Turkish operations in Syria—is beingwas carried out to a significantmajor extent by militia forces comprised largely of Sunni Arab opponents of the Syrian government.12 See Appendix C for a timeline of key events surrounding OPS.

|

Syrian Refugees in Turkey In addition to its ongoing military activities in Syria, Turkey hosts about 3.6 million registered Syrian refugees—more than any other country. Turkey has managed the refugees' presence in Turkish society by addressing their legal status, basic needs, employment, education, and impact on local communities.15 However, according to one human rights advocacy group, Turkey has "gradually limited operational space for [international] NGOs in Gaziantep and other Turkish cities that have been serving as hubs for aid delivery," with less experienced local NGOs attempting to "fill the resulting gap."16 Turkey has closed several refugee camps in 2019 and encouraged Syrians in those camps to integrate into Turkish society while resolution of their long-term status is pending. Problems in the Turkish economy over the past year may be fueling some tensions between refugees and Turkish citizens. Reports claim that, in light of domestic pressure, |

Initial operations have resulted in Turkish-led control over On October 17, Vice President Pence negotiated a conditional pause to OPS with Turkey that President Trump said on October 23 had become a permanent cease-fire.23 Pursuant to a joint U.S.-Turkey statement from October 17,24 the YPG had generally withdrawn from a key area inside the Syrian border—a largely Arab-populated section between the Syrian towns of Tell Abiad and Ras Al Ain—effectively cutting. This ceded control to Turkish-led forces whose forward progress had effectively cut off YPG communications between the largely Kurdish-populated enclaves of Kobane and Qamishli (see Figure A-3 below). Reports indicate that since OPS began, civilians on both sides of the border have been killed—with some areas in Turkey hit by cross-border fire—and that more than 200,000 people on the Syrian side have been displaced. The SDF's mid-October arrangement with the Syrian government—occurring shortly after U.S. officials announced that U.S. forces would leave northern Syria—may allow for greater Syrian and Russian control in SDF-controlled areas. Questions remain regarding the status of camps previously controlled by the SDF that hold thousands of IS prisoners and their families, and whether either the Syrian government or Turkish-led forces might assume custody over them.22

On October 17, Vice President Pence negotiated a conditional pause to OPS with Turkey that could become a permanent halt. If it does, the halt would apparently allow for a largely Turkish-patrolled safe zone in areas already occupied during the incursion and broader areas 30 kilometers (~19 miles) south of the Turkish border. A joint U.S.-Turkey statement contemplated a withdrawal of YPG forces from the safe zone by October 22, protections for Kurdish and other civilians living in the safe zone, and a possible reversal of the U.S. sanctions designations described below.23

U.S. Sanctions and Other Actions in Light of OPS

The Trump Administration has imposed sanctions on Turkey in response to OPS. The Administration's actions come amid concerns voiced by many—including Members of Congress—about the operation's potential security, political, and humanitarian effects on Syrian Kurds who have helped the United States counter the Islamic State, and on Syrian civilians.24 The Administration's sanctions may be intended to satisfy Members of Congress calling for stronger sanctions and to create room for diplomacy to reduce or end hostilities.25

The potential effect of sanctions remains unclear. One media article stated that U.S. sanctions are unlikely to deter Turkish military operations because the operations involve "one of Erdogan's core convictions" that the group is equivalent to the PKK.26 President Trump has referred to August 2018 U.S. actions vis-à-vis Turkey—when U.S. officials were seeking the release of an American pastor from a Turkish prison—as a successful example of using economic measures as leverage.27 Other sources assert that sanctions could negatively affect Turkey's fragile economy (see "Economic Status" below) and U.S.-Turkey bilateral relations.28

Executive Order 13894 and Other Administration Measures

On October 14, President Trump signed an executive order (EO 13894) to declare that Turkey's military offensive into northeastern Syria constituted a U.S. national emergency, and authorizing sanctions against current and former Turkish officials, government agencies, and sectors of the Turkish economy—as determined by the Secretary of the Treasury.29 The order also authorizes sanctions against any person found to be responsible for or engaged in the ongoing military operations in northeastern Syria, intimidation of displaced persons in the region, or interference in democratic processes, along with financial institutions or other parties deemed to be assisting any designated individuals.30

According to the President, the order authorizes "a broad range of consequences, including financial sanctions, the blocking of property, and barring entry into the United States."31 The Treasury Department issued two general licenses alongside the executive order that exempt transactions involving official U.S. business and Turkish dealings with major international organizations. A third general license allows U.S. persons to engage in transactions in a 30-day wind-down period to complete contracts with Turkey's defense and energy ministries.32 One media report suggests that the Administration may be crafting waivers to explicitly permit continued U.S. arms sales to Turkey.33

Halkbank: U.S. Indictment Related to Iran Sanctions On October 15, the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York announced a six-count indictment against Halkbank (a Turkish bank that is majority-owned by the government) for "fraud, money laundering, and sanctions offenses related to the bank's participation in a multibillion-dollar scheme to evade U.S. sanctions on Iran."34 In explaining the indictment, the U.S. Attorney stated, "The bank's audacious conduct was supported and protected by high-ranking Turkish government officials, some of whom received millions of dollars in bribes to promote and protect the scheme."35 On October 22, Turkey and Russia agreed to a memorandum of understanding (MOU) that Russia asserted on October 29 that YPG forces had withdrawn pursuant to the MOU. One U.S.-based analyst explained Turkey's deal with Russia by saying that "the U.S. was offering more or less the same deal ... with accommodation to the SDF. Russia's deal offered accommodation with the [Syrian] regime and Turkey chose that because their priority was to break the SDF structure."29 Ultimate Turkish and YPG objectives regarding the areas in question remain unclear. After October 29, Turkish-led fighters have periodically skirmished against YPG or Syrian government forces in places outside the areas under nominal Turkish control.30 U.S. officials apparently intend to continue partnering with SDF forces in some areas of Syria south of the zones from which YPG personnel were cleared,31 while the SDF has made some arrangements for its protection by Syrian government forces. According to one media account, Kurdish-led forces may have left car bombs and land mines before vacating areas now controlled by Turkish-led forces, and some of those explosives have reportedly caused civilian casualties.32 It also remains unclear how the Turkish-led administration of areas occupied during OPS might resemble Turkish-led administration in areas of northern Syria west of the Euphrates, including on the question of refugee return.33 Reportedly, some 300,000-400,000 of the 3.6 million Syrian refugees in Turkey hail from northeastern Syria.34 The Trump Administration imposed sanctions on some Turkish cabinet ministries and ministers in response to OPS, but has since lifted them.35 These sanctions may have been intended partly to mollify Members of Congress calling for stronger sanctions because of OPS's negative impact on America's Syrian Kurdish partners and other Syrian civilians, and partly to encourage diplomacy to end hostilities.36 The sanctions came pursuant to Executive Order (EO) 13984, which President Trump signed on October 14 and which remains in effect.37 According to the President, EO 13984 authorizes "a broad range of consequences, including financial sanctions, the blocking of property, and barring entry into the United States."38 Congress has taken some action in response to Turkey's October incursion into Syria. On October 16, the House passed H.J.Res. 77, criticizing both the Trump Administration's decision to pull troops back from the Turkey-Syria border area and Turkey's military operations. Then, on October 29, the House passed the Protect Against Conflict by Turkey Act (H.R. 4695) by a vote of 403-16. Among other things, H.R. 4695 would do the following: Halkbank: U.S. Indictment Related to Iran Sanctions On October 15, the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York announced a six-count indictment against Halkbank for "fraud, money laundering, and sanctions offenses related to the bank's participation in a multibillion-dollar scheme to evade U.S. sanctions on Iran."40 In explaining the indictment, the U.S. Attorney stated, "The bank's audacious conduct was supported and protected by high-ranking Turkish government officials, some of whom received millions of dollars in bribes to promote and protect the scheme."41 President Erdogan regularly criticized the proceedings in the Atilla-Zarrab case. For the case, U.S. investigators used findings from 2013 documents previously possessed by Turkish prosecutors whom Erdogan accused of seeking to undermine his government in connection with the Gulen movement. Atilla was convicted in January 2018, sentenced to 32 months in prison, released early in July 2019, and returned to Turkey. |

Pursuant to EO 13894,Also on October 14 the Treasury Department designated for sanctions Turkey's defense and energy ministries and their ministers, as well as Turkey's interior minister.38 That same day, the President announced that he will raise steel tariffs on Turkey back to 50% and will immediately stop bilateral negotiations aimed at increasing the volume of U.S.-Turkey trade.39

Congressional Action and Possible Additional Sanctions

Congress is actively considering responses to Turkey's incursion into Syria. On October 14, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi said that she had spoken with Senator Lindsey Graham, and called for "a bipartisan, bicameral joint resolution to overturn the President's dangerous decision in Syria immediately."40 On October 16, the House passed H.J.Res. 77 by a vote of 354-60 (with four voting present).

Speaker Pelosi also called for "a stronger sanctions package than what the White House is suggesting."41 As of October 18, two sanctions bills have been introduced in the House, and one in the Senate, with another Senate bill apparently forthcoming.

The Protect Against Conflict by Turkey Act (PACT Act, H.R. 4695, or "Engel-McCaul"), introduced by the Chair and Ranking Member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee,42 would apparently, among other things:

Require the President to block the U.S. property, interests in property, and related transactions of, and/or deny entry into the United States to (1) senior Turkish government and military officials deemed responsible for specific aspects of the Turkish incursion; (2) foreign persons deemed to have knowingly provided defense articles, services, or technology to Turkey that are usable in northern Syria; and (3) Halkbank (a Turkish bank that is majority-owned by the government), plus any financial institutions deemed to have "knowingly facilitated transactions for the Turkish Armed Forces or defense industry relating to Turkey's invasion of northern Syria."

Prohibit U.S. defense articles or services from transfer to Turkey that are usable in northern Syria.

Require the President to impose sanctions on Turkey for its acquisition of a Russian S-400 air defense system (see "CAATSA Sanctions?" below).43

Require the Administration to report on the estimated net worth and sources of income of President Erdogan and specified family members.

Require the Administration to provide plans or reports relating to IS prisoners, counter-IS operations, and U.S. assistance for Syrian Kurds and other communities affected by Turkish operations.

Some of the Engel-McCaul sanctions would terminate if the President notifies Congress that Turkey has taken certain actions to halt attacks, withdraw its forces, and avoid obstructing counter-IS operations.

The Chair and Ranking Member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (Risch-Menendez) announced their intention on October 17 to introduce a bill. Based on their announcement, the bill may require the imposition of sanctions similar to some in H.R. 4695, direct the President to oppose loans to Turkey from international finance institutions, and call for a number of reports relating to Turkey and Syria and Turkish participation in NATO.44

Some 16 Senators and more than 110 Representatives are sponsoring two different versions of a bill called the Countering Turkish Aggression Act of 2019 (CTAA; Senate version: S. 2644, or "Graham-Van Hollen"; House version: H.R. 4692, or "Cheney").45 Among other things, both the Graham-Van Hollen and Cheney versions would impose some sanctions similar to those in H.R. 4695. Additionally, their provisions prohibiting U.S. arms sales to Turkey and imposing secondary sanctions on foreign persons who knowingly support or transact with the Turkish military would apply broadly even to items or services beyond those usable by Turkey's military in northern Syria.

Prospects in the Senate for H.R. 4695 or other sanctions against Turkey are unclear. On October 31, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said the following on the Senate floor: We should think carefully about what specific effect we want sanctions to have, how Turkey will respond to them, and how Russia or others may exploit growing tensions between Washington and Ankara. Before targeting an economy that is highly integrated with Europe's economy, we should seek a better understanding of the specific economic impact that broad sanctions will have on the global economy.... Before using these kinds of policy tools—the kinds we use against Iran and North Korea—against a democracy of 80 million people, we should consider the political impact that blunt sanctions will have on the Turkish people. Will sanctions rally them to our cause or to Erdogan's? Would more targeted sanctions perhaps avoid some of these unintended consequences? These are just some of the critical questions I hope our committees of jurisdiction and the administration are able to examine before we act.46 Some Senators have introduced bills to impose sanctions on Turkey and/or require the Administration to report on specific Turkish actions and aspects of U.S./NATO relations with Turkey (S. 2624, S. 2641, and S. 2644).47 On November 6, Senators Bob Menendez and Chris Murphy introduced S.Res. 409, a resolution entitled to expedited consideration in the Senate (under Section 502B(c) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961; 22 USC 2304(c)) that could require a State Department report within 30 days on possible Turkish human rights abuses in Syria and other matters, and lead to additional expedited action on U.S. arms sales and assistance to Turkey. It is unclear whether President Trump would sign sanctions legislation on Turkey, or whether such legislation could attract veto-proof support in both houses of Congress. Regarding other possible congressional action affecting Turkey, a provision in the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (S. 1790), if enacted, could—under certain conditions—lift a 32-year-old arms embargo on U.S. arms sales to the Republic of Cyprus.48 The potential effect of sanctions on Turkish behavior remains unclear. One media article stated that U.S. sanctions are unlikely to deter Turkish military operations because the operations involve "one of Erdogan's core convictions" that the YPG is equivalent to the PKK.49 Some sources have asserted that sanctions could negatively affect market confidence and commerce in Turkey,50 but others have suggested that the economic contraction in Turkey that followed its currency shock of 2018 could cushion the impact of sanctions (see "Economic Status" below).51 One financial strategist said that measures constraining Turkish banks from transacting in dollars could particularly affect Turkey's financial system.52 At various points in Turkey's history, economic crises have contributed to political instability.53 Sanctions' effect on Turkish public sentiment may be difficult to gauge. While negative effects on Turkey's economy could lead to domestic pressure to change Turkish policies,54 they also could increase popular support for the government. Some sources suggest that Turkish citizens broadly support action in Syria to counter the YPG and to increase the likelihood of Syrian refugees returning home.55 Provisions in the pending bills requiring the imposition of sanctions against Turkey in connection with domestically popular policies could potentially boost support for President Erdogan given substantial existing anti-U.S. sentiment.56 While Turkey has long-standing, deeply rooted ties with the West, some sanctions could potentially create incentives for Turkey to increase trade, investment, and arms dealings with non-Western actors.57 Additionally, some 10 Representatives are sponsoring the U.S.-Turkey Relations Review Act of 2019 (H.R. 4694), which would require a detailed Administration report to congressional committees on various aspects of bilateral relations and implications for U.S./NATO strategic and military posture in the region.46 Two Senators are sponsoring S. 2624, a bill to prohibit U.S. arms sales to Turkey29, the House (by a vote of 405-11, with three voting present) passed H.Res. 296, a nonbinding resolution characterizing as genocide "the killing of 1.5 million Armenians by the Ottoman Empire [Turkey's predecessor state] from 1915 to 1923," the first time in 35 years that a house of Congress has voted to characterize the events in question as genocide.44 Turkish officials roundly criticized the House's action.45

Other Possible U.S. Options and NATO Implications

U.S. policymakers and lawmakers also could consider other options aimed at influencing Turkish behavior or securing U.S. interests. The United States and other NATO allies have no direct way to remove Turkey from NATO; the only explicit mechanism for leaving NATO in the North Atlantic Treaty is Article 13, which allows parties to leave one year after giving a notice of denunciation to the United States.4758 However, the United States and other NATO members could change their contributions of personnel and equipment and their participation in specific activities or locations in ways that affect cooperation with Turkey. On October 14, Secretary of Defense Mark Esper stated that he would "press our other NATO allies to take collective and individual diplomatic and economic measures in response to these egregious Turkish actions" during a planned visit to NATO headquarters later in October.48 Since 2013, NATO allies have been providing Turkey with air defense support around its border with Syria.4959 On October 14, all 28 member states of the European Union (22 of whom are also NATO members) agreed to "commit to strong national positions regarding their arms export policy to Turkey."5060 Several EU member states, including Italy (Europe's top arms exporter to Turkey), France, and Germany have suspended arms exports to Turkey, but the EU did not implement a formal EU-wide arms embargo.5161

Several open source media outlets have speculated about whether U.S. tactical nuclear weapons may be based at Incirlik Air Base, and if so, whether U.S. officials might consider taking them out of Turkey.5262 On October 16, President Trump expressed confidence in the safety of U.S. military assets that may be based at Incirlik because it is "a large powerful air base."5363

Turkey's S-400 Acquisition from Russia

U.S.-Turkey tensions over Turkey's acquisition of a Russian S-400 air defense system and the resulting U.S. removal of Turkey from the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program, along with possible sanctions on Turkey, could have broad implications for bilateral relations and defense cooperation. It also could affect Turkey's role in NATO.

In July 2019, Turkey reportedly began taking delivery of Russian S-400 components.54 The64 President Erdogan said then that the system will be fully deployed by April 2020.65 In November, the head of Turkey's defense procurement agency has said that Turkey expects the system to be operational sometime this year.55 President Erdogan has said that the system will be fully deployed by April 2020.56

Removal from F-35 Aircraft Program

In response to the beginning of S-400 deliveries to Turkey, the Trump Administration announced on July 17 that it was removing Turkey from participation in the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program.5767 Turkey had planned to purchase 100 U.S.-origin F-35s and was one of eight original consortium partners in the development and industrial production of the aircraft.5868 If Turkey does not receive the F-35, it might turn to other sources—possibly including Russia—to fill its capability need for next-generation aircraft and other major defense purchases.5969

|

End of Turkish Involvement: Impact on the F-35 Program Because the F-35 program features multinational industrial inputs, unwinding Turkey's involvement could present financial and logistical challenges. Turkish companies have been involved in about 6-7% of the supply chain—building displays, wiring, fuselage structures, and other parts—for F-35s provided to all countries. With some lead time to anticipate Turkey's possible removal from the program, the F-35 joint program office within DOD has identified alternative suppliers for the Turkish subsystems. Additionally, the depot to service engines for European countries' F-35s was initially slated to be in Turkey. However, according to Under Secretary Lord, "There are two other European MRO&Us [maintenance, repair, overhaul and upgrade facilities] that can absorb the volume with no issue whatsoever." The CEO of Lockheed Martin, the primary contractor for the F-35, said in May 2019 that if Turkey did not purchase the 100 aircraft, the consortium would not have difficulty finding willing buyers for them. Two possible buyers include Japan and Poland. |

In explaining the U.S. decision to remove Turkey from the F-35 program, Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment Ellen Lord said, "Turkey cannot field a Russian intelligence collection platform [within the S-400 system] in proximity to where the F-35 program makes, repairs and houses the F-35. Much of the F-35's strength lies in its stealth capabilities, so the ability to detect those capabilities would jeopardize the long-term security of the F-35 program."6777 A security concern regarding the F-35 could compromise its global marketability and effectiveness.6878 While some Russian radars in Syria may have already monitored Israeli-operated F-35s,6979 intermittent passes at long ranges reportedly might not yield data on the aircraft as conclusive as the more voluminous data available if an S-400 in Turkey could routinely monitor F-35s.7080 However, one U.S.-based analyst has said that U.S. concerns are "overblown" and that Russian tracking of F-35s in Turkey would not significantly differ from monitoring elsewhere.7181

CAATSA Sanctions?

The Turkey-Russia S-400 transaction could trigger the imposition of U.S. sanctions under Section 231 of the Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 (Title II of the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA; CAATSA (P.L. 115-44; 22 U.S.C. 9525). In late July 2019, President Trump reportedly asked a group of Republican Senators for flexibility on sanctions implementation regarding Turkey as he considered pursuing a deal potentially allowing Turkey to remain in the F-35 program if it (1) agreed not to use the S-400 and (2) acquired a U.S. Patriot air defense system.72 Turkish officials have maintained that the S-400 is a "done deal" and any purchase of Patriot would be in addition to the S-400.7382 In early November, President Erdogan said "We bought the S-400, that job is done, but if the U.S. will give us the Patriots, then we can buy them as long as the conditions are suitable."83 However, some analysts and former U.S. officials have said that Turkey's S-400 acquisition may not be final, or that a verifiable arrangement that prevents S-400 data gathering on the F-35 could allow the two systems to coexist in Turkey.7484 According to one media report, in July Erdogan threatened to retaliate against any sanctions under CAATSA, including by withdrawing Turkey from NATO and ejecting the United States from Incirlik Air Base.7585

Turkey's Rationale and Implications for NATO76

86

A number of analysts have sought to explain possible political motivation for Turkey's actions on the S-400 deal by citing Turkey's willingness to act more independently in the context of U.S.-Turkey tensions and other regional trends (see "Turkey's Strategic Orientation" above). Some have raised the possibility that Turkey may seek to defend against U.S.-origin aircraft of the type used by elements within the Turkish military during the 2016 coup attempt.7787 Other contributing factors to the S-400 decision may include nationalistic strains within Turkish domestic politics,7888 as well as Turkey's desires for more diversified sources of arms procurement due partly to its experience from the 1970s U.S. arms embargo over Cyprus.79

For some observers, the S-400 issue raises the possibility that Russia could take advantage of U.S.-Turkey friction to undermine the NATO alliance.8090 In 2013, Turkey reached a preliminary agreement to purchase a Chinese air defense system, but later (in 2015) withdrew from the deal, perhaps partly due to concerns voiced within NATO, as well as China's reported reluctance to share technology.81

Relevant U.S. Legislation

Congress has mandated that no U.S. funds can be used to transfer F-35s to Turkish territory until DOD submits a report—required no later thanA report was due from DOD on November 1, 2019—updating, to update a November 2018 report on a number of issues affecting U.S.-Turkey defense cooperation, including the S-400 and F-35.8292 Pursuant to Section 7046(d)(2) of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6), the update is to include a "detailed description of plans for the imposition of sanctions, if appropriate," for an S-400 purchase. In June 2019, the House passed H.Res. 372, a nonbinding resolution calling for consequences if Turkey does not cancel the S-400 deal.

In 2019, five separate provisions have either passed a house of Congress or been reported by a committee (H.R. 2500, S. 1790, S. 1102, two inS. 2474, H.R. 17402968) that would each prevent the use of funds to transfer F-35s to Turkey. MostSome of the provisions (other than the defense appropriations provision in H.R. 1740) are subject to waiver if the executive branch can certify in some manner that Turkey does not plan to take delivery of or keep the S-400.

Domestic Turkish Developments

Political Developments Under Erdogan's Rule

President Erdogan has ruled Turkey since becoming prime minister in 2003. After Erdogan became president in August 2014 via Turkey's first-ever popular presidential election, he claimed a mandate for increasing his power and pursuing a "presidential system" of governance, which he achieved in a 2017 referendum and 2018 presidential and parliamentary elections. Some allegations of voter fraud and manipulation surfaced in both elections.8393 Erdogan is a polarizing figure, with about half the country supporting his rule, and half the country against it. U.S. and European Union officials have expressed a number of concerns about rule of law and civil liberties in Turkey,8494 including the government's influence on media and Turkey's reported status as the country with the most journalists in prison.85

Erdogan's consolidation of power has continued amid domestic and international concerns about growing authoritarianism in Turkey. He outlasted the July 2016 coup attempt, after which Turkey's government detained tens of thousands and took over or closed various businesses, schools, and media outlets.8696 As part of the post-coup crackdown, the government has detained some Turks employed at U.S. diplomatic facilities in Turkey.8797

Erdogan's Islamist-leaning Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi, or AKP) maintained the largest share of votes in 2019 local elections, but lost some key municipalities to opposition candidates, including Istanbul. It remains unclear to what extent, if at all, these losses pose a threat to Erdogan's rule.8898

Economic Status

The Turkish economy slowed considerably during 2018, entering a recession in the second half of the year with negative consequences both for consumer demand and for companies seeking or repaying loans in global markets.8999 During 2018, the Turkish lira depreciated close to 30% against the dollar in an environment featuring a globally stronger dollar, rule of law concerns and political uncertainty, and significant corporate debt.

According to a September 2019 International Monetary Fund (IMF) analysis of the Turkish economy, "Growth has rebounded, aided by policy stimulus and favorable market conditions, following the sharp lira depreciation and associated recession in late-2018…. The current calm appears fragile. Reserves remain low, and private sector [foreign exchange] debt and external financing needs high."90100

Appendix A. Maps, Facts, and Figures

|

|

Geography |

Area: 783,562 sq km (302,535 sq. miles), slightly larger than Texas |

|

People |

Population: 81,257,239 (2018) Most populous cities: Istanbul 14.8 mil, Ankara 5.3 mil, Izmir 4.2 mil, Bursa 2.9 mil, Antalya 2.3 mil (2016) % of Population 14 or Younger: 24.3% Ethnic Groups: Turks 70%-75%; Kurds 19%; Other minorities 7%-12% (2016) Religion: Muslim 99.8% (mostly Sunni), Others (mainly Christian and Jewish) 0.2% Literacy: 96.2% (male 98.8%, female 93.6%) (2016) |

|

Economy |

GDP Per Capita (at purchasing power parity): $28,264 Real GDP Growth: 0.2% Inflation: 13.5% Unemployment: 13.8% Budget Deficit as % of GDP: 2.9% Public Debt as % of GDP: 30.4% Current Account Deficit as % of GDP: 0.7% International reserves: $101 billion |

Sources: Graphic created by CRS. Map boundaries and information generated by Hannah Fischer using Department of State boundaries (2011); Esri (2014); ArcWorld (2014); DeLorme (2014). Fact information (2019 estimates unless otherwise specified) from International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database; Turkish Statistical Institute; Economist Intelligence Unit; and Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook.

|

|

Source: CRS, using area of influence data from IHS Conflict Monitor

|

Appendix B. Timeline of Turkey's Involvement in Syria (2011-2019)

|

2011 |

Though the two leaders once closely corresponded, then-Turkish Prime Minister Erdogan calls for Syrian President Bashar al Asad to step down as protests and violence escalate; Turkey begins support for Sunni Arab-led opposition groups in cooperation with the United States and some Arab Gulf states |

|

2012-2014 |

As conflict escalates in Syria and involves more external actors, Turkey begins facing cross-border fire and jihadist terrorist attacks in border areas and urban centers; as well as allegations of Turkish government permissiveness with jihadist groups that oppose the Asad government |

|

Turkey unsuccessfully calls for U.S. and NATO assistance to establish safe zones in northern Syria as places to train opposition forces and gather refugees and IDPs |

|

|

At Turkey's request, a few NATO countries (including the United States) station air defense batteries in Turkey near Syrian border |

|

|

2014 |

The Islamic State obtains control of large swath of northern Syria |

|

IS attack on Kurdish-majority Syrian border town of Kobane unchallenged by Turkish military but repulsed by YPG-led Syrian Kurds (and some non-YPG Kurds from Iraq permitted to transit Turkish territory) with air support from U.S.-led coalition, marking the beginning of joint anti-IS efforts between the United States and YPG-led forces (including non-Kurdish elements) that (in 2015) become the SDF through U.S. train-and-equip initiatives |

|

|

Turkey, with Erdogan now president, begins allowing anti-IS coalition aircraft to use its territory for reconnaissance purposes |

|

|

2015 |

Turkey begins permitting anti-IS coalition aircraft to conduct airstrikes from its territory |

|

As YPG-led forces find success in taking over IS-controlled areas with U.S.-led coalition support, a Turkey-PKK peace process (ongoing since 2013) breaks down and violence resumes in Turkey; Turkish officials' protests intensify in opposition to U.S. partnership with SDF in Syria |

|

|

U.S. military withdraws Patriot air defense battery from Turkey; some other NATO countries continue operating air defense batteries on Turkey's behalf |

|

|

In September, Russia expands its military involvement in Syria and begins helping Asad regain control over much of the country In November, a Turkish aircraft shoots down a Russian aircraft based in Syria under disputed circumstances; Russia responds with punitive economic measures against Turkey |

|

|

2016 |

After failed coup attempt in Turkey in July, Turkey partners in August with Syrian opposition forces on its first military operation in Syria (Operation Euphrates Shield), |

|

2017 |

Turkey begins Astana peace process on Syria with Russia and Iran |

|

In preparation for the campaign against the final major IS-held urban center in Raqqah, U.S. officials decide in May to arm YPG personnel directly, insisting to protesting Turkish officials that the arms will be taken back after the defeat of the Islamic State |

|

|

2018 |

Turkey and its Syrian opposition partners militarily occupy the Kurdish enclave of Afrin (Operation Olive Branch); significant Kurdish displacements prompt humanitarian and human rights concerns |

|

2019 |

Erdogan insists on a safe zone in Syria to prevent opportunities for YPG attacks in Turkey or collaboration with Turkey-based PKK forces, and to resettle Syrian refugees; U.S. officials try to prevent conflict and to get coalition assistance to patrol border areas in northeastern Syria |

|

In October, President Trump announces highly controversial pullback of U.S. Special Forces from SDF-controlled border areas; to date, the United States had not recovered U.S.-origin arms from YPG personnel Turkey launches Operation Peace Spring (OPS), with Turkish-led forces obtaining control of various border areas between Tell Abiad and Ras Al Ain, along with key transport corridors; reports of civilian casualties and displacement take place amid general humanitarian and human rights concerns Secretary of Defense Esper announces pending withdrawal of U.S. forces from northern Syria; SDF reaches arrangement with Syrian government permitting its forces a greater presence in previously SDF-controlled areas Vice President Pence and other high-ranking U.S. officials arrange with Turkey for a pause to OPS conditioned on future Turkish and Turkey and Russia reach MOU on areas of northeastern Syria President Trump announces a permanent cease-fire after YPG troops withdraw from specified areas Pentagon announces that some U.S. forces will remain in eastern Syria Sources: Various open sources. |

Sources: Various open sources

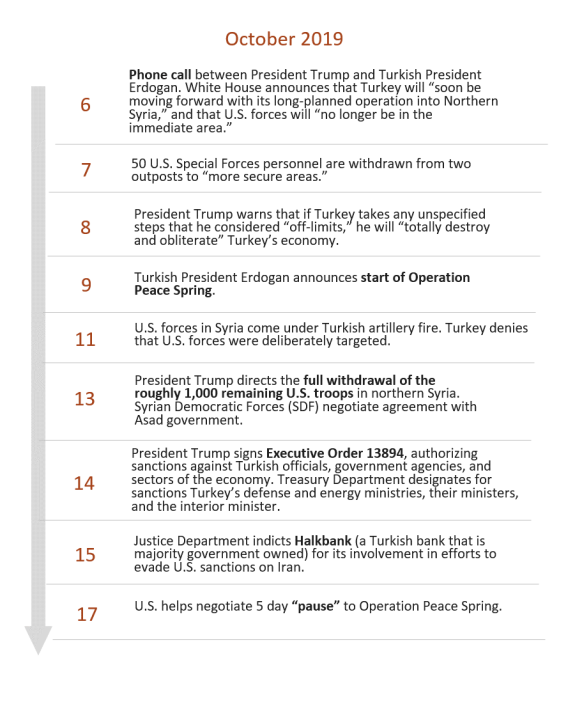

Appendix C.

Timeline of Key Events: October 6-17

|

|

Source: CRS, with information culled from various open sources. |

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Selcuk Colakoglu, "The Rise of Eurasianism in Turkish Foreign Policy: Can Turkey Change its pro-Western Orientation?" Middle East Institute, April 16, 2019; Asli Aydintasbas and Jeremy Shapiro, "The U.S. and Turkey have bigger problems than their erratic leaders," Washington Post, January 15, 2019; Recep Tayyip Erdogan, "Erdogan: How Turkey Sees the Crisis with the U.S.," New York Times, August 10, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. |

See, e.g., Max Hoffman, Michael Werz, and John Halpin, "Turkey's 'New Nationalism' Amid Shifting Politics," Center for American Progress, February 11, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. |

See, e.g., Keith Johnson and Robbie Gramer, "Who Lost Turkey?" foreignpolicy.com, July 19, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. |

See, e.g., Aaron Stein, "Why Turkey Turned Its Back on the United States and Embraced Russia," foreignaffairs.com, July 9, 2019. Additionally, for information on Turkey-Russia energy ties, see CRS In Focus IF11177, TurkStream: Another Russian Gas Pipeline to Europe, by Sarah E. Garding et al.; and CRS Report R41368, Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. |

Aaron Stein, "Bilateral Basing Squabbles: Incirlik and America's Out of Area Wars," Atlantic Council, August 29, 2018; Testimony of Steven Cook of the Council on Foreign Relations, Senate Foreign Relations Committee Hearing, September 6, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. |

Gordon Lubold, Felicia Schwartz, and Nancy A. Youssef, "U.S. Pares Back Use of Turkish Base amid Strains with Ankara," Wall Street Journal, March 11, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. |

Nimet Kirac, "US-Turkey cooperation against Islamic State ongoing, Pentagon says," Al-Monitor Turkey Pulse, August 27, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8. |

Aaron Stein, "The Day After S-400: The Turkish-American Relationship Will Get Worse," War on the Rocks, May 23, 2019; Kyle Rempfer, "US Air Force ties to Greece may grow as relations with Turkey sour," Air Force Times, April 30, 2019; Joseph Trevithick, "Docs Show US To Massively Expand Footprint At Jordanian Air Base Amid Spats With Turkey, Iraq," The Drive, January 14, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9. |

See, e.g., Soner Cagaptay, "U.S. Safe Zone Deal Can Help Turkey Come to Terms with the PKK and YPG," Washington Institute for Near East Policy, August 7, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10. |

Ryan Browne |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11. |

Ibrahim Kalin, Twitter post, 4:32 AM, October 7, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14. |

Semih Idiz, "Debate over Syrian refugees gathers steam in Turkey," Al-Monitor Turkey Pulse, January 11, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15. |

See, e.g., Laura Batalla and Juliette Tolay, Toward Long-Term Solidarity with Syrian Refugees? Turkey's Policy Response and Challenges, Atlantic Council, September 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16. |

Refugees International, Losing Their Last Refuge: Inside Idlib's Humanitarian Nightmare, September 2019.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pinar Tremblay, "Are Syrians in Turkey no longer Erdogan's 'brothers'?" Al-Monitor Turkey Pulse, July 30, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Fahrettin Altun, "Turkey Is Helping, Not Deporting, Syrian Refugees," foreignpolicy.com, August 23, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dorian Jones, "Erdogan Plays Refugee Card as Criticism Mounts Over Turkey's Kurdish Offensive," Voice of America, October 10, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

CRS Report R41368, Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

White House, "The United States and Turkey Agree to Ceasefire in Northeast Syria," October 17, 2019; Department of State, "Special Representative for Syria Engagement James F. Jeffrey Remarks to the Traveling Press," October 17, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25. |

See text of October 9 letter from President Trump to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, from the Twitter account of a New York Times White House correspondent. Katie Rogers, Twitter post, 4:29 PM, October 16, 2019, https://twitter.com/katierogers/status/1184567108853751809?s=20. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26. |

Keith Johnson and Elias Groll, "Trump's Weak Sanctions May Only Help Erdogan," foreignpolicy.com, October 14, 2019. See also Mevlut Cavusoglu, "Why Turkey Took the Fight to Syria," New York Times, October 11, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 27. |

For information on the U.S. actions and their possible effect, see CRS Report R41368, Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28. |

"Turkey's incursion in Syria may leave its own economy wounded," Reuters, October 10, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 29. | Spokesperson for the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Press briefing note on Syria, October 15, 2019. White House, "The United States and Turkey Agree to Ceasefire in Northeast Syria," October 17, 2019. President of Russia, Memorandum of Understanding Between Turkey and the Russian Federation, October 22, 2019. Aaron Stein, quoted in Diego Cupolo, "Weakened US sanctions threat lingers in wake of Turkish deal with Russia," Al-Monitor Turkey Pulse, October 23, 2019. "Fighting persists near Turkish border in Syria safe zone, Kurdish officials say," NBC News, October 31, 2019. "US to deploy more troops to eastern Syria to secure oilfields," Al Jazeera, October 25, 2019. Carlotta Gall, "Syrian Refugees Doubt That 'Safe Zone' Turkey Plans Will Be Safe," New York Times, November 2, 2019. Ibid.; "Read the Memo by a U.S. Diplomat Criticizing Trump Policy on Syria and Turkey," nytimes.com, November 7, 2019. Diego Cupolo, "Ankara grapples with security, repatriation in Syria as cease-fire deadline expires," Al-Monitor Turkey Pulse, October 29, 2019. Department of the Treasury, Executive Order on Syria-related Sanctions; Syria-related Designations; Issuance of Syria-related General Licenses, October 14, 2019; Department of the Treasury, Syria-related Designations Removals, October 23, 2019. Uri Friedman, "The Trump Administration Has Only One Move," theatlantic.com, October 16, 2019. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

White House, "Statement from President Donald J. Trump Regarding Turkey's Actions in Northeast Syria," October 14, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

40Section 8 of H.R. 4695, as engrossed in the House on October 29, 2019, invokes pertinent provisions of the Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 (title II of the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, or CAATSA; P.L. 115-44; 22 U.S.C. 9525). |

Department of the Treasury, Executive Order on Syria-related Sanctions; Syria-related Designations; Issuance of Syria-related General Licenses, October 14, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 33. |

Tony Bertuca, "U.S. crafting waivers to continue arms sales to Turkey," Inside Defense, October 15, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Department of Justice, U.S. Attorney's Office, Southern District of New York, "Turkish Bank Charged In Manhattan Federal Court For Its Participation In A Multibillion-Dollar Iranian Sanctions Evasion Scheme," October 15, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ibid. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ibid. Senator Ron Wyden, Ranking Member of the Senate Finance Committee, sent an October 24 letter to Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin posing specific questions about his involvement with the Administration's treatment of Halkbank on this matter. Text of letter available at https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/102319%20Halkbank—Mnuchin.pdf. | Ibid. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Benjamin Weiser, "At Iran Sanctions Trial: A Star Witness Revealed, and a Sleepy Juror," New York Times, December 2, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 43. |

Pursuant to Section 231 of the Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 (title II of the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA; P.L. 115-44; 22 U.S.C. 9525). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 44. |

Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Foreign Relations Committee Leaders Announce New Comprehensive Syria-Turkey Legislation, October 17, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 45. |

Office of Senator Chris Van Hollen, Van Hollen, Graham Announce Framework for Sanctions Against Turkey, October 9, 2019; Office of Representative Liz Cheney, Cheney and Colleagues Release Text of Turkey Sanctions Legislation, October 16, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 46. |

Office of Representative Adam Kinzinger, Kinzinger & Cicilline Question Turkey as a NATO Partner, October 16, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 47. |

Article 2 of the treaty states that its parties "will seek to eliminate conflict in their international economic policies and will encourage economic collaboration between any or all of them." |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 48. |

Department of Defense, "Statement by Secretary of Defense Dr. Mark T. Esper Regarding Turkey, Syria Border Actions," October 14, 2019. https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Releases/Release/Article/1988372/statement-by-secretary-of-defense-dr-mark-t-esper-regarding-turkey-syria-border/. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 49. |

NATO, "NATO Patriot Mission in Turkey," https://shape.nato.int/ongoingoperations/nato-patriot-mission-in-turkey-. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 50. |

"EU governments limit arms sales to Turkey but avoid embargo," Reuters, October 14, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 51. |

Ibid. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 52. |

David E. Sanger, "Trump Followed His Gut on Syria. Calamity Came Fast," New York Times, October 14, 2019; Ankit Panda, "Why Are U.S. Nuclear Bombs Still in Turkey?" newrepublic.com, October 15, 2019; Stephen Losey, "With Turkey's invasion of Syria, concerns mount over nukes at Incirlik," Air Force Times, October 15, 2019; David Brennan, "U.S.-Turkey tensions raise fears over future of nuclear weapons near Syria," Newsweek, October 15, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 53. |

White House, Remarks by President Trump and President Mattarella of the Italian Republic Before Bilateral Meeting, October 16, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 49.

|

|

Keith Johnson and Elias Groll, "Trump's Weak Sanctions May Only Help Erdogan," foreignpolicy.com, October 14, 2019. See also Mevlut Cavusoglu, "Why Turkey Took the Fight to Syria," New York Times, October 11, 2019. 50.

|

|

"Turkey's incursion in Syria may leave its own economy wounded," Reuters, October 10, 2019. 51.

|

|

Mustafa Sonmez, "Why Trump's sanctions failed to shock Turkey's economy," Al-Monitor Turkey Pulse, October 22, 2019. 52.

|

|

Sebastian Galy, cited in Jack Ewing, "Tariffs Won't Stop Turkey's Invasion of Syria, Analysts Warn," New York Times, October 15, 2019. 53.

|

|

See, e.g., "Turkey's real crisis," Economist, May 15, 2001. 54.

|

|

Jack Ewing, "Tariffs Won't Stop Turkey's Invasion of Syria, Analysts Warn," New York Times, October 15, 2019. 55.

|

|

Bethan McKernan, "Turkey hails Erdoğan a hero as death toll mounts in border war," theguardian.com, October 19, 2019. 56.

|

|

See, e.g., Transcript of interview between Ari Shapiro and Soner Cagaptay, "What Impacts U.S. Sanctions May Have on Turkey's Economy," NPR, October 16, 2019. 57.

|

|

Paul McLeary, "Tough Sanctions May Drive Turkey into Russia's Arms," Breaking Defense, October 10, 2019; Burak Ege Bekdil and Matthew Bodner, "No obliteration: Western arms embargo has little impact on Turkey as it looks east," Defense News, October 24, 2019. 58.

|

|

Article 2 of the treaty states that its parties "will seek to eliminate conflict in their international economic policies and will encourage economic collaboration between any or all of them." 59.

|

|

NATO, NATO Patriot Mission in Turkey, https://shape.nato.int/ongoingoperations/nato-patriot-mission-in-turkey-. 60.

|

|

"EU governments limit arms sales to Turkey but avoid embargo," Reuters, October 14, 2019. 61.

|

|

Ibid. 62.

|

|

Miles A. Pomper, "Why the US has nuclear weapons in Turkey—and may try to put the bombs away," The Conversation, October 23, 2019; David E. Sanger, "Trump Followed His Gut on Syria. Calamity Came Fast," New York Times, October 14, 2019. 63.

|

|

White House, "Remarks by President Trump and President Mattarella of the Italian Republic Before Bilateral Meeting," October 16, 2019. |

Metin Gurcan, "How Turkey is planning to handle US blowback over S-400s," Al-Monitor Turkey Pulse, July 16, 2019. Media reports indicate that the S-400 deal, if finalized, would be worth approximately $2.5 billion. Tuvan Gumrukcu and Ece Toksabay, "Turkey, Russia sign deal on supply of S-400 missiles," Reuters, December 29, 2017. According to this article, the portion of the purchase price not paid for up front (55%) would be financed by a Russian loan. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Turkey |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Department of Defense transcript, Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment Ellen M. Lord and Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Policy David J. Trachtenberg Press Briefing on DOD's Response to Turkey Accepting Delivery of the Russian S-400 Air And Missile Defense System, July 17, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A 2007 memorandum of understanding among the consortium participants is available at https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/102378.pdf, and an earlier 2002 U.S.-Turkey agreement is available at https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/196467.pdf. For information on the consortium and its members, see CRS Report RL30563, F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Program, by Jeremiah Gertler. For details on Turkish companies' participation in the F-35 program, see https://www.f35.com/global/participation/turkey-industrial-participation. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

https://www.f35.com/global/participation/turkey-industrial-participation; Paul McLeary, "F-35 Production Hurt If Turkey Kicked Out of Program: Vice Adm. Winter," Breaking Defense, April 4, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Valerie Insinna, "Turkish suppliers to be eliminated from F-35 program in 2020," Defense News, June 7, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Department of Defense transcript, op. cit. footnote |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

McLeary, op. cit. footnote |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Michael R. Gordon, et al., "U.S. to Withhold Order of F-35s from Turkey," Wall Street Journal, July 17, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Insinna, op. cit. footnote |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Marcus Weisgerber, "Lockheed: We Could Easily Sell Turkey's F-35s to Other Customers," Defense One, May 29, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Department of Defense transcript, op. cit. footnote |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

See, e.g., Sebastien Roblin, "Congress Temporarily Banned Sale of F-35 Jets to Turkey (But Turkish Pilots Are Still Training to Fly Them)," nationalinterest.org, September 2, 2018. One analysis explained the process by which infiltration could happen, writing that for an F-35 to fly within lethal range of the S-400 in Turkey, certain deconfliction equipment would need to be integrated into the S-400 system, potentially allowing for compromise of this equipment and the information it shares. Kyle Rempfer, "Here's how F-35 technology would be compromised if Turkey also had the S-400 anti-aircraft system," Air Force Times, April 5, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Jonathan Marcus, "What Turkey's S-400 missile deal with Russia means for Nato," BBC News, June 13, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Rempfer, op. cit., footnote |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Michael Kofman of CNA, cited in "How Missile System Irks the U.S. and Threatens to Drive a Wedge into NATO," New York Times, July 12, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Trump asks GOP senators for 'flexibility' on Turkey sanctions," NBC News, July 24, 2019. In a July 23 letter to President Trump, 10 Democratic Senators from the Senate Foreign Relations Committee expressed disappointment that the Administration was only engaging with Republican Senators on the issue and communicated an expectation that Trump would impose sanctions on Turkey without delay. Text of letter available at https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/07-23-19%20SFRC%20Dems%20letter%20to%20Trump%20re%20Turkey%20S400.pdf. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Aboulafia, op. cit. footnote |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Trump asks GOP senators for 'flexibility' on Turkey sanctions," op. cit. footnote |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

For more information on this subject, see CRS Report R41368, Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Johnson and Gramer, op. cit. footnote 3; Nicholas Danforth, "Frustration, Fear, and the Fate of U.S.-Turkish Relations," German Marshall Fund of the United States, July 19, 2019; Ali Demirdas, "S-400 and More: Why Does Turkey Want Russian Military Technology |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Aaron Stein, "Why Turkey Turned Its Back on the United States and Embraced Russia," foreignaffairs.com, July 9, 2019; Bulent Aras, "Why Does Turkey Want S-400 Missiles?" LobeLog, July 3, 2019; Asli Aydintasbas, "Unhappy anniversary: Turkey's failed coup and the S-400," European Council on Foreign Relations, July 17, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Interview with Bulent Aliriza of Center for Strategic and International Studies, "4 questions on the risks facing Turkey's defense industry," Defense News, April 22, 2019; Aras, op. cit. footnote |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

See, e.g., Vladimir Frolov, "Our Man in NATO: Why Putin Lucked Out with Recep Erdogan," Moscow Times, April 15, 2019; Sinan Ulgen, "It's Not Too Late to Stop Turkey from Realigning with Russia," foreignpolicy.com, April 11, 2019 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Turkey confirms cancellation of $3.4 billion missile defence project awarded to China," Reuters, November 18, 2015. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Pentagon report on Turkey's F-35 program delivered to Congress," Reuters, November 15, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), Limited Referendum Observation Mission Final Report, Turkey, April 16, 2017 (published June 22, 2017); OSCE, International Election Observation Mission, Statement of Preliminary Findings and Conclusions, Turkey, Early Presidential and Parliamentary Elections, June 24, 2018 (published June 25, 2018). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

See, e.g., State Department, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2018, |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

See, e.g., "Turkish Media Group Bought by Pro-Government Conglomerate," New York Times, March 22, 2018; "Turkey leads the world in jailed journalists," Economist, January 16, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Human Rights Watch, "Turkey: Events of 2018," World Report 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Carlotta Gall, "Turkish Trial of U.S. Consular Employee Highlights Rift in Relations," New York Times, March 28, 2019; Aykan Erdemir and Merve Tahiroglu, "Turkey Doubles Down on Persecution of U.S. Consular Employees," Foundation for Defense of Democracies, February 1, 2019. U.S. citizens Andrew Brunson (a Christian pastor) and Serkan Golge (a NASA scientist), whose cases attracted significant attention, were released from prison in October 2018 and May 2019, respectively. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Laura Pitel, "Turkey: old friends threaten Recep Tayyip Erdogan's reign," Financial Times, September 25, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

See, e.g., Nevzat Devranoglu, "Turkey's economy to contract in 2019, longer recession ahead," Reuters, April 12, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

IMF, Turkey: Staff Concluding Statement of the 2019 Article IV Mission, September 23, 2019. |