U.S.-Iran Conflict and Implications for U.S. Policy

Changes from September 23, 2019 to December 13, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

U.S.-Iran Tensions and Implications for U.S. Policy

Contents

- Context for Heightened U.S.-Iran Tensions

- Iranian Responses and Actions

- Attacks on Tankers

- Actions by Iran's Regional Allies

- Iran and U.S.

DowningsDowning of Drones - UK-Iran Tensions and Iran Tanker Seizures

- Attack on Saudi Energy Infrastructure on September 14

- JCPOA-Related Iranian Responses

- International Responses to the Current Dynamic

- U.S. Responses

- Additional Sanctions

- Military Deployments

- Coalition to Secure the Gulf

- Gulf Maritime Security Operation

- Scenarios and Possible Outcomes

- Further Escalation

- Status Quo

- De-Escalation

- U.S. Military Action:

Considerations, Additional Options, and RisksOptions and Considerations

- Resource Implications of Military Operations

- Congressional Responses

- Legislation and AUMF Considerations

Possible Issues for Congress

Figures

Summary

Since May 2019, U.S.-Iran tensions have escalated significantly, but have stopped short of eruptingnot erupted into armed conflict. The Trump Administration, following its 2018 withdrawal from the 2015 multilateral nuclear agreement with Iran (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, JCPOA), has taken several steps in its campaign of applying "maximum pressure" on Iran. Iran and Iran-linked forces have attacked and seized commercial ships, caused destruction of some critical infrastructure in the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, and posed threats to U.S. forces and interests, including downing a U.S. unmanned aerial vehicle. Iran has exceeded some nuclear limitations stipulated inreduced its compliance with the provisions of the JCPOA. The Administration has sentbeen deploying additional military assets to the region to try to deter future Iranian actions and has continued to impose additional U.S. sanctions on Iran.

President Donald Trump has said he wants a diplomatic solution that would not only ease tensions but resolve broader disputes with Iran, centered on a revised JCPOA that encompasses not only nuclear issues but also Iran's ballistic missile program and Iran's support for regional armed factions. High-ranking officials from several countries, including Japan, Germany, France, Oman, Qatar, and Iraq, as well as some Members of Congress, have sought to mediate to try to de-escalate U.S.-Iran tensions, or otherwise encourage by encouraging direct talks between Iranian and U.S. leaders. President Trump has stated that he welcomes talks with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani without preconditions, but no direct talks have been known to take place to date or are scheduled, including during the upcoming U.N. General Assembly meetings in New York that both leaders are expected to attend.

The action-reaction dynamic between the.

The United States and- Iran hastensions have the potential to escalate into significant conflict. The United States military has the capability to undertake a large range of options against Iran, both against Iran directly and against its regional allies and proxies. However, Iran's alliances with and armedIran's materiel support for armed factions throughout the region, and its including its provision of short-range ballistic missiles to these factions, and Iran's network of agents in Europe, Latin America, and elsewhere, give Iran the potential to expand confrontation into areas where U.S. response options might be limited. A September 14, 2019, attack on critical energy infrastructure in Saudi Arabia demonstrated that Iran and/or its allies have the capability to cause significant damage to U.S. allies and to U.S. regional and global economic and strategic interests, and raised questions about the effectiveness of U.S. defense relations with the Gulf states in preventing future such Iranian attacks.

Members of Congress have received additional information from the Administration about the causes of the uptick in U.S.-Iran tensions and Administration planning for further U.S. responses. They have responded in a number of ways; some Members have sought to pass legislation requiring congressional approval for any decision by the President to take military action against Iran.

Additional detail on U.S. policy options on Iran, Iran's regional and defense policy, and Iran sanctions can be found in CRS Report RL32048, Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options, by Kenneth Katzman; CRS Report RS20871, Iran Sanctions, by Kenneth Katzman; CRS Report R44017, Iran's Foreign and Defense Policies, by Kenneth Katzman; and CRS Report R43983, 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force: Issues Concerning Its Continued Application, by Matthew C. Weed.

Context for Heightened U.S.-Iran Tensions

U.S.-Iran relations have been mostly adversarial—but with varying degrees of intensity— since the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran. Since then, U.S. officials consistently have identifiedand official reports consistently identify Iran's support for militant armed factions in the Middle East groups asregion a significant threat to U.S. interests and allies. Attempting to constrain Iran's nuclear program took precedence in U.S. policy after 2002 as that program advanced. The United States also has sought to block Iran's ability to purchase advancedthwart Iran's purchase of new conventional weaponry and to developdevelopment of ballistic missiles.

In May 2018, the Trump Administration withdrew the United States from the 2015 nuclear agreement (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, JCPOA), asserting that the accord did not address the broad range of U.S. concerns about Iranian behavior and would not permanently preclude Iran from developing a nuclear weapon.1 Senior Administration officials explain Administration policy as the application ofAdministration officials, such as Secretary of State Michael Pompeo and his senior adviser on Iran affairs, Ambassador Brian Hook, say that Administration policy is to apply "maximum pressure" on Iran's economy to (1) compel it to renegotiate the JCPOA to address the broad range of U.S. concerns and (2) deny Iran the revenue to continue to develop its strategic capabilities or intervene throughout the region.2 Administration statements also suggest that an element of the policy could be to create enough economic difficulties to stoke unrest in Iran, possibly to the point where the regime collapses.3

As the Administration has pursued its policy of maximum pressure, bilateral tensions have escalated significantly, with U.S. steps going beyond the reimposition of all U.S. sanctions that were in force before JCPOA went into effect in January 2016. Key developments since April 2019 include the following:

- officials deny that the policy is intended to stoke economic unrest in Iran.3

As the Administration has pursued its policy of maximum pressure, including imposing sanctions beyond those in force before JCPOA went into effect in January 2016, bilateral tensions have escalated significantly. Key developments that initially heightened tensions include the following.

On April 8, 2019, the Administration designated the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO),4 representing the first time that an official military force was designated as an FTO. The designation stated that "The IRGC continues to provide financial and other material support, training, technology transfer, advanced conventional weapons, guidance, or direction to a broad range of terrorist organizations, including Hizballah, Palestinian terrorist groups like Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, Kata'ib Hizballah in Iraq, al-Ashtar Brigades in Bahrain, and other terrorist groups in Syria and around the Gulf.... Iran continues to allow Al Qaeda (AQ) operatives to reside in Iran, where they have been able to move money and fighters to South Asia and Syria."5Iran's parliament subsequently enacted legislation declaring U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) and related forces in the Middle East to be terrorists. - As of May 2, 2019, the Administration ended a U.S. sanctions exception for any country to purchase Iranian oil, aiming to drive Iran's oil exports to "zero."6

- On May 3, 2019, the Administration ended two of the seven waivers under the Iran Freedom and Counter-Proliferation Act (IFCA, P.L. 112-239)—waivers that allow countries to help Iran remain within stockpile limits set by the JCPOA.7

Five waivers for nuclear work on Iran were extended and, at the next expiration on August 1, 2019, the Administration renewed those five waivers again. - On May 5, 2019, citing reports that Iran or its allies might be preparing

its alliesto attack U.S. personnel or installations, then-National Security Adviser John Bolton announced that the United States was accelerating the previously planned deployment of the USS Abraham Lincoln Carrier Strike Groupto the regionand sending a bomber task force to the Persian Gulf region.8 - On May 24, 2019, the Trump Administration

formallynotified Congress of immediate foreign military sales and proposed export licenses for direct commercial sales of defense articles—training, equipment, and weapons—with a possible value of more than $8 billion, including sales of precision guided munitions (PGMs) to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). In making the 22 emergency sale notifications, Secretary of State Pompeo invoked emergency authority codified in the Arms Export Control Act (AECA). The notification, and cited the need "to deter further Iranian adventurism in the Gulf and throughout the Middle East" as justification for the sales.9 The September 14, 2019, attack on Saudi critical energy infrastructure could prompt additional sales to Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states of missile defense, air defense, cyberattack defense equipment, and other gear.

."9 Iranian Responses and Actions

Iran has been responding to the additional responded to the U.S. pressure in part by demonstrating its ability to harm global commerce and other U.S. interests and to raise new concerns about Iran's nuclear activities. Iran also could be tryingmight have sought to cause international actors, such as Russia, European countries, and countries in Asiaincluding those that depend on stable oil supplies, to put pressure on the Trump Administration to reduce its sanctions pressure on Iran.

Attacks on Tankers

- On May 12-13, four oil tankers—two Saudi, one Emirati, and one Norwegian ship—were damaged. Iran denied involvement

in the incidents, but a Defense Department (DOD) official on May 24, 2019, attributed the tanker attacks to the IRGC.10 A report to the United Nations based on Saudi, UAE, and Norwegian information found that a "state actor" was likely responsible, but did not name a specific perpetrator.11 - On June 13, 2019, two Saudi tankers in the Gulf of Oman were attacked.

One was carrying petrochemicals and the other, crude oil, to buyers in Asia. The same day,Secretary of State Michael Pompeo stated, "It is the assessment of the U.S. government that Iran is responsible for the attacks that occurred in the Gulf of Oman today….. The assessment isbased on the intelligence, the weapons used, the level of expertise needed to execute the operation, recent similar Iranian attacks on shipping, and the fact that no proxy group in the area has the resources and proficiency to act with such a high degree of sophistication.... "12

Actions by Iran's Regional Allies

In addition to direct Iranian action, Iran's allies in the region have been conducting attacks that might be linked to U.S.-Iran tensions, although it is not known definitively whether Iran directed or encouraged such attacks. Still, Trump Administration policy, as articulated by Secretary of State Pompeo, has been to hold Tehran responsible for the actions of its regional allies.13

- On May 19, 2019, a rocket was fired into the secure "Green Zone" in Baghdad but it caused no injuries or damage.14 Iran-backed Iraqi militias were widely suspected of the firing and U.S. Defense Department officials attributed it to Iran.15 The incident came four days after the State Department ordered "nonemergency U.S. government employees" to leave U.S. diplomatic facilities in Iraq, claiming a heightened threat that Iranian allies may act against the United States there. In mid-June, there were several other rocket attacks in Iraq, including one that landed near a housing compound for employees of an Exxon-Mobil energy project in the southern Iraqi province of Basra, wounding several persons.16 A May 2019 attack on Saudi pipeline infrastructure in Saudi Arabia with an unmanned aerial aircraft, first

attributed to beingconsidered to have been launched from Yemen, was later determined to have been initiated from Iraq.17 - In June 2019 and subsequently, the Houthis, who have been fighting against a Saudi-led Arab coalition that intervened in Yemen against the Houthis in March 2015, claimed responsibility for

threeattacks on an airport in Abha, in southern Saudi Arabia.18The Houthis have since conducted similar attacks against Saudi airports,,18 and on Saudi energy installations,andothertargets. The Houthis claimed responsibility for the large-scale attack on Saudi energy infrastructure on September 14, 2019, but, as discussed below, U.S.officials question Houthi origin for the attackand Saudi officials have concluded that the attack did not originate from Yemen. - In a June 13, 2019, statement, Secretary of State Pompeo asserted Iranian responsibility for a May 31, 2019, car bombing in Afghanistan that wounded four U.S. military personnel.

Recent State DepartmentAdministration reports have asserted that Iran is providing materiel support to some Taliban militants, butthe Taliban claimed responsibility for the May 31 attack andoutside experts asserted that the Iranian role in that attack isunclear or evenunlikely.19

Iran and U.S. DowningsDowning of Drones

On June 20, 2019, Iran shot down an unmanned aerial surveillance aircraft (RQ-4A Global Hawk Unmanned Aerial Vehicle) near the Strait of Hormuz, claiming it had entered Iranian airspace over the Gulf of Oman. U.S. Central Command officials stated that the drone was over international waters.20 IRGC commander-in-chief Major General Hossein Salami stated "The downing of the American drone is an open, clear and categorical message, which is: the defenders of the borders of Iran will decisively deal with any foreign aggression.... This is the way the Iranian nation deals with its enemies."

On June 20, 2019, according to his posts on the Twitter social media site, President Trump ordered a strike on three Iranian sites related to the Global Hawk downing, but called off the strike on the grounds that it would have caused Iranian casualties and therefore been "disproportionate" to the Iranian shootdown.21 The United States did reportedly launch a cyberattack against Iranian equipment used to track commercial ships.22

On July 18, 2019, President Trump announced that U.S. forces in the Gulf had downed an Iranian drone via electronic jamming in "defensive action" over the Strait of Hormuz. Iran denied that any of its drones were shot down.

UK-Iran Tensions and Iran Tanker Seizures

An effort by the United Kingdom (UK) to enforce EU sanctions against Syria opened up a dispute between Iran and the UK.23 On July 4, authorities from the British Overseas Territory Gibraltar, backed by British marines, impounded an Iranian tanker, the Grace I, off the coast of Gibraltar on the grounds that it was allegedly violating an EU embargo on the provision of oil to Syria. Iranian officials termed the seizure an illegitimate act of "piracy," and in subsequent days, the IRGC Navy sought to intercept a UK-owned tanker in the Gulf, the British Heritage, but the force was reportedly driven off by a British warship escorting the tanker. On July 19, the IRGC Navy seized a British-flagged tanker near the Strait of Hormuz, the Stena Impero, claiming variously that it violated Iranian waters, was polluting the Gulf, collided with an Iranian vessel, or that the seizure was retribution for the seizure of the Grace I.

On July 22, the UK's then-Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt explained the government's reaction to the Stena Impero seizure as pursuing diplomacy with Iran to peacefully resolve the dispute, while at the same time sending additional naval vessels to the Gulf to help secure UK commercial shipping there. Secretary Hunt stated that the UK had "made clear in public that [it] would be content with the release of Grace I if there were sufficient guarantees the oil would not go to any entities sanctioned by the EU."23 24 President Donald Trump and other senior U.S. officials publicly supported the UK position. Secretary of State Pompeo said that "the responsibility ... falls to the United Kingdom to take care of their ships."25 At the same time, UK officials stated that they remained committed to the JCPOA and would not join the Trump Administration campaign of maximum pressure on Iran.

On August 15, following a reported pledge by Iran not to deliver the oil cargo to Syria, a Gibraltar court ordered the ship – which had been (renamed the Adrian Darya 1 -) released. Gibraltar courts turned down a U.S. Justice Department request to impound the ship as a violator of U.S. sanctions on Syria and on the IRGC, which the U.S. filing said was financially involved in the tanker and its cargo.2426 The ship apparently, despite the pledge, delivered its oil to Syria,25 despite the pledge27 and, as a consequence, the United States imposed new sanctions on individuals and entities linked to the ship and to the IRGC-linked network that the Department of the Treasury identified as assisting that and other Iranian oil shipments. On September 22, 2019, Iran saidreleased the Stena Impero the Stena Impero was now free to depart Iranian waters.

President Donald Trump and other senior U.S. officials publicly supported the UK position. Secretary of State Pompeo said that "the responsibility ... falls to the United Kingdom to take care of their ships."26 At the same time, UK officials stated that they remained committed to the JCPOA and would not join the Trump Administration campaign of maximum pressure on Iran.

Separate from the UK-Iran dispute over the Grace I and the Stena Impero, on August 5, Iran seized an Iraqi tanker on August 5, 2019, for allegedly smuggling Iranian diesel fuel to "Persian Gulf Arab states."2728

|

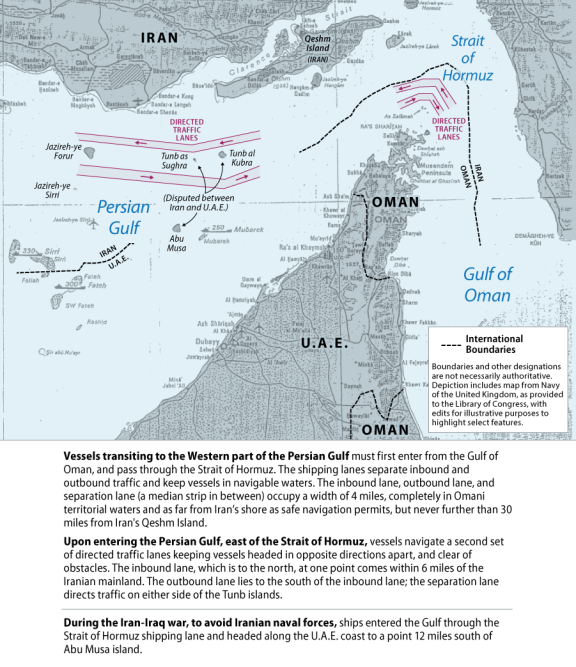

Parallels to Past Incidents in the Gulf Iran's apparent attacks on tankers in May and June share some characteristics with events in the mid-to-late 1980s during the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq war. 1987-1988 represented the height of the |

Attack on Saudi Energy Infrastructure on September 1429

30

On September 14, an attack was conducted on multiple locations within critical Saudi energy infrastructure sites at Khurais and Abqaiq. The Houthi movement in Yemen, which receives arms and other support from Iran, claimed responsibility but Secretary of State Pompeo stated: "Amid all the calls for de-escalation, Iran has now launched an unprecedented attack on the world's energy supply. There is no evidence the attacks came from Yemen."30"31 Saudi officials said on September 16, 2019, , that the attacks did not originate in Yemen and that the weapons used in the attack were of Iranian origin, but they did not name Iran as the perpetrator, instead inviting "U.N. and international experts ... to participate in the investigations."31."32 Press reports stated that U.S. intelligence indicates that Iran itself was the staging ground for the attacks, in which cruise missiles, possibly assisted by unmanned aerial vehicles, struck 17-19nearly 20 targets at those Saudi sites.33 targets at those Saudi sites.32 The Iraqi government denied that its territory was used for the strikes and said that Secretary Pompeo agreed in a call with Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abd al Mahdi. Iranian officials have denied responsibility for the attack.

The attack shut down a significant portion of Saudi oil production and, whether conducted by Iran itself or by one of its regional allies, escalated U.S.-Iran and Iran-Saudi tensions and demonstrated a significant capability to threaten U.S. allies and interests. Whether, or how, the United States and/or Saudi Arabia or other countries might respond to the attack was not announced. President Trump wrote on Twitter: "There is reason to believe that we know the culprit, are locked and loaded depending on verification. But we are waiting to hear from the Kingdom as to who they believe was the cause of this attack, and under what terms we would proceed." Some critics, including some in Congress, expressed the view that President Trump was appearing to defer to Saudi Arabia too much decisionmaking input about the U.S. response to the attack.33 He also stated in a White House meetingPresident Trump stated on September 16 that he would "like to avoid" conflict with Iran, and it is possible that President Trump might be using apparent deference to Saudi Arabia to defray calls for a U.S. military response to the attack and the Administration did not retaliate militarily. U.S. officials did announce modest increases in U.S. forces in the region and some new U.S. sanctions on Iran. Secretary of State Pompeo visited Saudi Arabia and the UAE during September 18-19 to discuss responses to the attack, and in his press conferences in the region he stated an intent to use diplomacy to try to resolve the crisis. U.S. officials also announced a modest increase in U.S. forces in the region and new U.S. sanctions. The issue is likely to form a major component of U.S. diplomacy during the U.N. General Assembly meetings the week of September 23.

The attacks on the Saudi infrastructure might raiseraised broader questions about how to deal with Iran and the region, including:

- , includingWhat is the extent and durability of the long-standing implicit and explicit U.S. security guarantees to the Gulf states?

- Have Iran's military technology capabilities advanced further than has been estimated by U.S. officials and the U.S. intelligence community?

- What additional

defense equipment, if any, might be provided to the Gulf states toU.S. deployments of forces or equipment, if any, might prevent or deter a similar attack in the future? - What additional U.S. steps might be required to deter Iran from future

such attacks? - How, if at all, will the strikes affect the stated U.S. commitment to diplomacy with Iran?

attacks?JCPOA-Related Iranian Responses34

Since the Trump Administration's May 2018 announcement that the United States would no longer participate in the JCPOA, Iranian officials repeatedly have rejected renegotiating the agreement or discussing a new agreement. Tehran also has conditioned its ongoing adherence to the JCPOA on receiving the agreement's benefits from the remaining JCPOA parties, collectively known as the "P4+1." On May 10, 2018, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif wrote that, in order for the agreement to survive, "the remaining JCPOA Participants and the international community need to fully ensure that Iran is compensated unconditionally through appropriate national, regional and global measures." He added that

Iran has decided to resort to the JCPOA mechanism [the Joint Commission established by the agreement] in good faith to find solutions in order to rectify the United States' multiple cases of significant non-performance and its unlawful withdrawal, and to determine whether and how the remaining JCPOA Participants and other economic partners can ensure the full benefits that the Iranian people are entitled to derive from this global diplomatic achievement.35

Tehran also threatened to reconstitute and resume the country's pre-JCPOA nuclear activities. According to Iranian officials, the country can rapidly reconstitute its fissile material production capability and has begun preparations for expanding its uranium enrichment program since the May 2018 U.S. announcement described above.36

Several meetings of the JCPOA-established Joint Commission since the U.S. withdrawal have not produced a firm Iranian commitment to the agreement.3736 Tehran has argued that the remaining JCPOA participants' efforts have been inadequate to sustain the agreement's benefits for Iran. In May 8 letters to the other JCPOA participant governments, Iran announced that, as of that day, Tehran had stopped "some of its measures under the JCPOA," though the government emphasized that it was not withdrawing from the agreement. Specifically, Iranian officials said that the government will not transfer low enriched uranium (LEU) or heavy water out of the country in order to maintain those stockpiles below the JCPOA-mandated limits. A May 8 statement from Iran's Supreme National Security Council explained that Iran "does not anymore see itself committed to respecting" the JCPOA-mandated limits on LEU and heavy water stockpiles.38

Beginning in July 2019, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) verified that some of Iran's nuclear activities were exceeding JCPOA-mandated limits; the Iranian government has since increased the number of such activities.38 Specifically, according to IAEA reports, Iran has exceeded JCPOA-mandated limits on its heavy water stockpile, the number of installed centrifuges, its LEU stockpile, and the LEU's concentration of the relevant fissile isotope uranium-235. Tehran is also reportedly conducting JCPOA-prohibited research and development activities, as well as centrifuge manufacturing, and has also begun to enrich uranium at its Fordow enrichment facility.39 40 Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, in a November 5 speech, explained that Tehran still supports negotiations with the P4+1: In the next two months, we still have a chance for negotiations. We will negotiate and talk with each other, and if we find the right solution, and the solution is in lifting of the sanctions, and that we will be able to sell our oil easily, we will be able to use our money in banks easily, and other issues that they have imposed sanctions on, such as metals and insurance, and if they lift sanctions fully, we will also return to the previous conditions fully.41 U.S. partner countries have generally backed U.S. charges of Iranian responsibility for the Iranian attacks discussed above. However, U.S. partner countries have consistently called for the de-escalation of tensions and the avoidance of war. The EU countries have said they will not join the U.S. maximum pressure campaign as a consequence of Iran's provocative acts, although the UK, France, and Germany have urged Iran to negotiate a new JCPOA that includes limits on Iran's missile development.42 Some U.S. allies have joined a U.S. effort to deter Iran from further attacks on shipping in the Gulf, discussed further below. As tensions have increased with Iran, the Trump Administration has undertaken a number of steps to try to deter further attacks, weaken Iran strategically, and compel Iran to negotiate a broader resolution of U.S.-Iran differences.Behrouz Kamalvandi, spokesperson for the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI), warned on June 17, 2019, that Iran would exceed on June 27 the JCPOA-mandated quantitative limit on Iran's LEU stockpile if the agreement's other participants did not meet Tehran's demands. The Iranian government stated that it would resume full compliance with the JCPOA if the remaining participants agree during a 60-day period following the May 8, 2019, announcement to meet Tehran's demands (by July 7). However, Kamalvandi and other Iranian officials warned that, absent such an agreement, Iran would cease to accept any constraints on the concentration of Iranian-produced LEU. According to two July reports from then-IAEA Director General Yukiya Amano, both the quantity of Iran's LEU stockpile, as well as the that 37

LEU's concentration of the relevant fissile isotope uranium-235, currently exceed JCPOA-mandated limits.39 A report from IAEA Acting Director General Cornel Feruță explains that Iran has continued this activity.40

Iranian officials have conditioned Tehran's continued implementation of its JCPOA commitments on fulfillment by France, Germany, and the United Kingdom (collectively known as the "E3") of Iran's demands described above. On August 27, Foreign Minister Zarif reportedly stated that Tehran will scale back still more of its JCPOA commitments, should the E3 fail to meet these demands.41 Deputy Foreign Minister Abbas Araqchi stated on August 28 that Iran's continued JCPOA participation depends on the government's ability to export oil or receive compensation for lost oil export revenue. Specifically, Araqchi explained, the E3 should persuade the United States to reinstate sanctions waivers that permitted such exports pursuant to the JCPOA. Should Washington refuse to do so, he argued, the E3 should "provide lines of credit" to Iran "equivalent to the amount of oil Iran would export."42 Some of these proposals are discussed further below.

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani Rouhani stated on September 5 that the AEOI

is required to start whatever technical needs of the country are in the field of research and development immediately, and put aside all [JCPOA-mandated] commitments in the field of research and development in all kinds of new centrifuges and everything we need for enrichment.43

Iran has begun installing advanced centrifuges at its pilot uranium enrichment facility, according to a September 8 report from Feruță.44 If Tehran and the P4+1 reach an agreement within 60 days, Iran will resume implementing its JCPOA commitments, Rouhani added in his September 5 statement.45 The remaining JCPOA participants apparently judge Tehran in compliance with the agreement.46

International Responses to the Current Dynamic

Responses by U.S. partners and others to the U.S.-Iran tensions have been consistent with the positions of major international players on the JCPOA. In general, U.S. partners and other countries have accepted U.S. charges of Iranian responsibility for the attacks on tankers and the September 14 strike on Saudi infrastructure. At the same time, however, U.S. partner countries have called for steps to de-escalate tensions and to avoid war in the region. For example, after the initial escalation of tensions in early May, Secretary of State Pompeo attended meetings with EU officials on May 13 to brief them on U.S. intelligence about the heightened Iranian threat. At the conclusion of the meetings, UK Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt stated "We [EU] are very worried about the risk of a conflict happening by accident, with an escalation unintended really on either side."47 The EU countries have said they will not, as a consequence of Iran's provocative acts, join the U.S. maximum pressure campaign. At the same time, some U.S. allies have joined a U.S. effort to deter Iran from further attacks on shipping in the Gulf. The U.S. efforts to construct a Gulf shipping protection operation are discussed further below.

Saudi Arabia, while avoiding directly blaming Tehran for the September 14 attacks, has called for an international response to them.

U.S. Responses

As tensions have increased with Iran, the Trump Administration has undertaken a number of steps to try to deter further attacks, weaken Iran strategically, and perhaps compel Iran to negotiate a broader resolution of U.S.-Iran differences.

Sanctions48

- On May 8, the President issued Executive Order 13871, blocking the U.S.-based property of persons and entities determined by the Administration to have conducted significant transactions with Iran's iron, steel, aluminum, or copper sectors.49

On June 24, 2019, President Trump issued Executive Order 13876, blocking the U.S.-based property of Supreme Leader Ali Khamene'i and his top associates. Sanctions on Iran's Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif were imposed on July 31, 2019,under that Order.- On September 4, 2019, the State Department Special Representative for Iran and Senior Advisor to the Secretary of State Brian Hook said the United States would offer up to $15 million to any person who helps the United States disrupt the financial operations of the IRGC and its Qods Force

, which is—the IRGC unit that assists Iran-linked forces and factions in the region. The fundswillare to be drawn from the long-standing "Rewards for Justice Program" that provides incentives for persons to help prevent acts of terrorism. - On September 20,

after a statement by the President that he would increase sanctions on Iran as part of the U.S. response to the September 14 attack on Saudi Arabia2019, the Trump Administration imposed additional sanctions on Iran's Central Bank bydesignateddesignating it a terrorism supporting entity under Executive Order 13224. The Central Bank is already subject to a number of U.S. sanctions, rendering unclear whether any new effect on the Bank's ability to operate would result. Also sanctioned was an Iranian sovereign wealth fund, the National Development Fund of Iran.

Military Deployments

In response to the escalating tensions with Iran in recent monthsU.S. Military Deployments and Possible new Threats

To try to deter further Iranian attacks, the United States has added forces and military capabilities in the region, beyond the accelerated deployment of the USS Abraham Lincoln and associated forces, discussed above. The deployments have added severaladditional deployments as of October 2019 had added 14,000 thousand U.S. military personnel to a baseline of more than 60,000 U.S. forces in and around the Persian Gulf, which include those stationed at military facilities in the Arab states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, UAE, Qatar, Oman, and Bahrain), and those in Iraq and Afghanistan.5045 Defense Department officials have indicated that the additional deployments since early May restorehave mostly restored forces who were redeployed from the region a few years ago, and that the new deployments do not represent preparation for any U.S. offensive against Iran.5146

- On May 24, 2019, the Defense Department

said that the President approved a plan to augment U.S. defense and deterrence against Iran by deploying to the Gulf regionannounced deployment of an additional 900 military personnel,extendingextension of the deployment of another 600 that were sent earlier to operate Patriot missile defense equipment, andsendingthe sending of additional combat and reconnaissance aircraft.5247

- On June 17, 2019, then-Acting Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan announced that the United States was sending an additional 1,000 military personnel to the Gulf "for defensive purposes."

5348 - On July 18, 2019, U.S. defense officials said that an additional 500 U.S. troops

would deploy to Saudi Arabia. The deployment, to Prince Sultan Air Base south of Riyadh, reportedly will include fighter aircraft and air defense equipment.54, fighter aircraft and air defense equipment, would deploy to Prince Sultan Air Base in Saudi Arabia, which is south of Riyadh. 49 U.S. forces used the base to enforce a no-fly zone over southern Iraq during the 1990s, but left there after Saddam Hussein was ousted by Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003.- On September 26, 2019, DOD announced deployment to Saudi Arabia of 200 U.S. personnel supporting an additional Patriot missile defense battery and four An/MPQ-64 Sentinel Radars.50

- On October 11, 2019, DOD announced deployment to Saudi Arabia of additional forces (reportedly about 1,800) that, together with other announced deployments, brought to 3,000 the number of U.S, military personnel "extended or authorized" to deploy there in the prior few months. Also deployed were two Patriot systems and one Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system that were ordered in September to "prepare to deploy," as well as two fighter squadrons and one air expeditionary wing.51

After several months in which tensions seemed stable or even declining, in late November 2019, the commander of U.S. Central Command, General Kenneth McKenzie, stated that the U.S. deployments during May—October might have deterred Iran from attacking U.S. targets, but that "I wouldn't rule [another Iranian attack like the September 14 attack on Saudi oil infrastructure] out going forward."52 Referring to recent rioting in Iran in response to a reduction in fuel subsidies, General McKenzie added that "Iran is under extreme pressure" and is trying to "crack the [maximum pressure] campaign" with attacks to provoke an American military response. In early December, press reports and U.S. officials provided details on the signs of Iranian activity of concern, including an Iranian shipment of sophisticated components for cruise and other short-range missiles bound for the Houthis but intercepted by U.S. naval forces on November 2553, and the reported Iranian supply of short range missiles to allied forces inside Iraq.54 A series of indirect fire attacks in December 2019 have targeted Iraqi military facilities where U.S. forces are present, amid ongoing protests and unrest in Iraq. The U.S. government has designated Iran-linked Iraqi groups and individuals in 2019 for involvement in human rights abuses and attacks on Iraqi protesters.55U.S. officials have said publicly that the attacks in Iraq were occurring with increased frequency and becoming more sophisticated.56

The identification of new Iranian threats—coupled with the CENTCOM assessment that the additional U.S. deployments were not sufficient to deter Iran—seems to have prompted consideration of deploying additional U.S. forces to the region. One report, denied by the Administration, said the Administration might send dozens more warships and as many as 14,000 more U.S. military personnel to the region57 At a Senate Armed Services Committee hearing on December 5, 2019, Undersecretary of Defense for Policy John Rood said that "as necessary, the secretary of Defense has told me he intends to make changes to our force posture there." But Rood did not say how large a potentially additional force the Pentagon may be considering. Cable News Network reported on December 5, 2019, citing conversations with unnamed DOD officials, that a more likely additional figure ranges from 4,000 to 7,000 personnel focused on air and missile defense.

Gulf Maritime Security OperationIn addition to deploying more U.S. forces, the Trump Administration has sought to assemble a coalition that would use military assets to try to protect commercial shipping in the Gulf. In June, Secretary Pompeo visited Saudi Arabia, UAE, and several Asian states to recruit allies to contribute funds and military resources to a new maritime security and monitoring initiative (termed "Operation Sentinel") for the Gulf, the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, and the Suez Canal. Defense Secretary Mark Esper told reporters on August 28, 2019, "I am pleased to report that Operation Sentinel is up and running," but the coalition, termed the International Maritime Security Construct (IMSC), was formally inaugurated in Bahrain in November 2019. It consists of seven nations (United States, UK, UAE, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Albania and Australia) operating four sentry ships at crucial points in the Gulf. 58Qatar and Kuwait have pledged to join the mission in the near future, and Canada and "some European countries" are described as having "expressed interest in the effort."59 The IMSC appears to supplement longstanding multilateral Gulf naval operations that have targeted smuggling, piracy, the movement of terrorists and weaponry, and other potential threats in the Gulf.

U.S. forces used the base to enforce a no-fly zone over southern Iraq during the 1990s, but left there after Saddam Hussein was ousted by Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003. - On September 20, U.S. officials announced a "moderate" (widely interpreted as a few hundred) deployment of additional U.S. forces to Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The forces reportedly would accompany additional missile defense equipment and combat aircraft sent to facilities in those countries, and be "defensive in nature."55

Coalition to Secure the Gulf

The Trump Administration has sought to assemble a coalition that would use military assets to try to protect commercial shipping in the Gulf. In June, Secretary Pompeo visited Saudi Arabia, UAE, and several Asian states to recruit allies to contribute funds and military resources to a new maritime security and monitoring initiative (termed "Operation Sentinel") for the Gulf.56 The U.S. plan reportedly involves U.S. surveillance of Iranian naval movements and coordination of multilateral naval vessels escorting or protecting commercial ships under their respective flags. The U.S. plan appears to represent a version of the 1987-1988 "Operation Earnest Will," discussed in the textbox above.57At an August 28 press briefing, Defense Secretary Mark Esper told reporters "I am pleased to report that Operation Sentinel is up and running." The countries recruited to the mission are as follows:

- In concert with the dispute with Iran over the Grace I (see above), Britain sent two warships to the Gulf to protect British shipping. On August 5, the UK announced it would join the U.S. protection mission.58 On August 25, it was reported that the UK had sent a third warship to the Gulf to join the effort. In the August 5 announcement and subsequent statements, UK officials stated explicitly that the UK remains committed to the JCPOA and that its deployments are not to be taken as support for the U.S. maximum pressure campaign against Iran.

- On August 19, Bahrain, which hosts the headquarters for all U.S. naval forces in the Gulf, announced it would join the U.S.-led Gulf shipping protection mission. Its role was not specified.

- On August 22, the Australian government announced it would join the mission by sending A P-8A Poseidon maritime surveillance plane by the end of 2019 and a Royal Australian Navy frigate, which will deploy with the security flotilla in January for six months.59

- On September 19, 2019, in the wake of the attack on Saudi energy infrastructure, Saudi Arabia and the UAE announced they would join the mission.

Other nations, such as India, have sent some naval vessels to the Gulf to protect their commercial ships, and China's ambassador to the UAE said in early August that China is considering joining the mission, although no announcement of China's participation has since been made. Additionally, Israeli Foreign Minister Yisrael Katz said Israel would join the coalition, although it is likely that Israel would remain in a supporting role in light of the stated opposition of Iran, Iraq, and other regional governments to a direct Israeli military role in the Gulf.60 Defense Secretary Esper did not list Israel as a participant in his August 28 press briefing mentioned above. A question is whether additional countries might join the mission in the aftermath of the September 14 attack on Saudi critical infrastructure.

France reportedly intends to lead a separate maritime security mission (headquartered in Abu Dhabi) in the Gulf starting in early 2020; the Netherlands and several other European countries have expressed interest. India has sent some naval vessels to the Gulf to protect Indian commercial ships.

Scenarios and Possible Outcomes

Events could take any of several directions that might affect congressional oversight and authorization or limitations on the U.S. use of military force, Administration and congressional steps to support regional partners potentially affected by conflict, or new sanctions measures.

Further Escalation

U.S. and Iranian officials have said they do not want armed conflict. However, leaders on each side have said they will respond with force if the other attacks.

The Iranian leadership insists that U.S. sanctions be eased, and, in order to pressure on the United States to do so, Iran could undertake or provide material support for further actions such as the September 14 strike against Saudi critical energy infrastructure. Iran could potentially try to attack U.S. military, civilian, diplomatic, or other personnel. Iran could attack or seize additional commercial ships in the Gulf, possibly causing loss of life.

The IRGC's Qods Force (IRGC-QF) could encourage its allies in Syria, Lebanon,61 Iraq, Yemen, Bahrain, and Afghanistan to attack a wide range of targets, potentially including U.S. military personnel and installations.62 The IRGC-QF has supplied these regional allies with rockets, short-range ballistic missiles, and other weaponry to undertake such assaults.63 The annual State Department report on international terrorism has consistently asserted that Iran and its key ally, Lebanese Hezbollah, have a vast network of agents in Europe, Latin America, and elsewhere that could act against U.S. personnel and interests outside the Middle East.64 The U.S. intelligence community assess that Iran has "the largest inventory of ballistic missiles in the region," and press reports indicateAs one example, U.S. officials said in December 2019 that attacks on facilities in Iraq used by U.S. forces are increasing in frequency and sophistication, possibly to the point where U.S. forces would respond militarily, potentially causing escalation to U.S.-Iran conflict.64

For the past several years, the U.S. intelligence community, in its annual worldwide threat assessment briefings for Congress, has assessed that Iran has "the largest inventory of ballistic missiles in the region,"65 and the 2019 version of the annual, congressionally mandated report on Iran's military power by the Defense Intelligence Agency indicates that Iran is advancing its drone technology and the precision targeting of the missiles it provides to its regional allies.66 Israel asserts that these advances pose a sufficient threat to justify Israeli attacks against Hezbollah, additional targets in Syria, and apparently also against Iran-backed forces in Iraq during August 2019.65 The September 14 attack on Saudi critical energy infrastructure could represent an Iranian intent to escalate tensions, perhaps to increase pressure on the United States and its allies to ease sanctions.

The annual State Department report on international terrorism has consistently asserted that Iran and its key ally, Lebanese Hezbollah, have a vast network of agents in Europe, Latin America, and elsewhere that could act against U.S. personnel and interests outside the Middle East.68

Status Quo

It is possible that the U.S.-Iran tensions might not evolve to military conflict, but also might not result in talks that lead to a potential resolution of the U.S.-Iran differences. At the August 28, 2019, DOD press briefing discussed above, Defense Secretary Esper asserted that the U.S.-led Gulf protection mission, Operation Sentinel, had "been successful" in deterring further Iranian attacks and thatsaid: "I'm not sure I'm ready to call the crisis over yet, but so far so good. And we hope the trend lines continue that way." TheHowever, the September 14 attack appears to represent a break in that trendand ongoing indirect fire attacks on facilities in Iraq indicate that the apparent stability could be upset suddenly.

De-Escalation

U.S., U.S. partner, and Iranian officials have explored ways to de-escalate the tensions. Most experts assert that a compromise will require U.S. and/or EU efforts to easeIt can be argued that a long-lasting compromise would require an easing pressure on Iran's economy, as well as and Iran's acceptance of some additional limits beyond those stipulated in the JCPOA. President Trump and other senior officials have stated repeatedly since May 2019 that the United States is willing to talk directly with Iranian leaders, without preconditions, to de-escalate tensions and negotiate a revised JCPOA.66 For Iran's part, Foreign Minister Zarif visited the United Nations in July 2019 and offered, in return for the United States' lifting of U.S. JCPOA-related sanctions, to accelerate Iran's ratification of the Additional Protocol to its IAEA safeguards agreement ahead of the JCPOA-mandated schedule.6769

Still, theThe United States and Iran do not have diplomatic relations and there have been no known high-level talks between Iran and the United StatesAdministration officials since the Trump Administration withdrew from the JCPOA. The absence of direct channels has led various third country leaders, as well as some Members of Congresssuch as Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, either with or separate from specific U.S. imprimatur, to try to move Tehran and Washington toward direct talks. Shortly after tensions began escalating, Secretary Pompeo had at least one direct contact with Sultan Qaboos of Oman, who in the past has mediated U.S.-Iran talks,68 and Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe sought to mediate a de-escalation during his visit to Iran on June 12-13, 2019, the first visit to Iran by a Japanese leader since the Islamic revolution. That visit followed one by Germany's foreign minister to Tehran in early June. President Trump also President Trump confirmed on July 19, 2019, that he authorized Senator Rand Paul to engage in diplomatic discussions with Foreign Minister Zarif; Senator Paul reportedly met with Zarif in New York in July.69

Several Gulf countries, including Qatar and the UAE, have sent delegations to Iran to try to ease U.S.-Iran tensions that the Gulf leaders say could lead to severe destruction in the Gulf states themselves in the event of conflict.7071 Whereas Qatar has consistently maintained relations with Iran, thea UAE delegation that visited Tehran in late July undertook the first UAE security talks with Iran since 2013 and their visit appeared to soften the country's position on engagement with Iran.

Prior to the September 14 attack on Saudi energy infrastructure, French President Macron appeared to produce someproduced apparent movement toward U.S.-Iran talks. In early July, he sent a top aide, Emmanuel Bonne, to Tehran for mediation talks. While hosting the G-7 summit in Biarritz, Macron invited Foreign Minister Zarif to meet with him and to speak with British and German diplomats. No Trump-Zarif meeting took place in Biarritz, and President Trump told reporters "I think it's too soon to meet, I didn't want to meet." However but, at a press conference at the close of the summit, President Trump reiterated his willingness, in principle, to meet with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, while at the same time reiterating his criticism of the JCPOA. President Macron expressed hope for a Trump-Rouhani meeting in the near future, presumably during the U.N. General Assembly meetings in New York in September. President Trump stated that he welcomes talks with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani without preconditions. Some press reports indicated that President Trump considered - possibly as an incentive for Iran to meet -presumably during the U.N. General Assembly meetings in New York in September.

Some press reports indicated that President Trump considered supporting a French credit line proposal discussed below by approving sanctions waivers and exceptions to facilitate the credit line, possibly as an incentive for Iran to meet with him.72.71 However, in the wake of the September 14 attacks in Saudi Arabia and since, the Supreme Leader has stated that there would be no U.S.-Iran talks and Rouhani and Zarif have restated the view that U.S. sanctions be lifted before any such talks. Yet, as the U.N. meetings got under way on September 23, President Trump still apparently did not rule out talks with Rouhani if the Iranian president were willing to undertake discussions.

Even if the United States and Iran do not talk directly

Absent U.S.-Iran talks, the EU or other actors could also produce a de-escalation by formulating policies that provide Iran with the economic benefits of the JCPOA. One new European proposal was revealed at the G-7 meeting: according to French officials, the proposal involves—a proposal under which multiple countries providingwould provide a $15 billion credit line, secured by future deliveries of oil, in exchange for Iran's return to full JCPOA compliance. The credit line would be used to facilitate thefacilitate operations of a newan EU trading mechanismvehicle (Instrument in Support of Trading Exchanges, INSTEX) that has yet to complete any transactions but that attracted several new European partners in November 2019.73.72

U.S. Military Action: Considerations, Additional Options, and Risks

Options and Considerations

The military is a tool of national power that the United States can use to advance its objectives, and the design of a military campaign and effective military options depend on the policy goals that U.S. leaders seek to accomplish. The Trump Administration has stated that its "core objective ... is the systemic change in the Islamic Republic's hostile and destabilizing actions, including blocking all paths to a nuclear weapon and exporting terrorism."7374 As such, the military could be used in a variety of ways to try and contain and dissuade Iran from prosecuting its "hostile and destabilizing actions." These ways range from increasing presence and posture in the region to use of force to change Iran's regime. As with any use of the military instrument of national power, any employment of U.S. forces in this scenario could result in retaliatory Iranian action and/or the escalation of a crisis.

U.S. military action may not be the appropriate tool to achieve systemic change within the Iranian regime, and may in fact worsen the situation forset back the political prospects of Iranians sympathetic to a change of regime. Employing overt military force is likely to strengthen anti-American elements within the Iranian government. Some observers question the utility of military power against Iran due to global strategic considerations. The 2017 National Security Strategy and 2018 National Defense Strategy both note that China and Russia represent the key strategic challenges to the United States today and into the future. As such, shifting military assets into the United States Central Command (CENTCOM) area of responsibility requires diverting them from use in other theaters such as Europe and the Pacific, thereby sacrificing other long-term U.S. strategic priorities.

Secretary of Defense Mark Esper and other U.S. officials have stated that the additional U.S. deployments since May are intended to "deter"deter Iran from taking any further provocative actions. Yet, the downing of the RQ-4A Global Hawk Unmanned Aerial Vehicle on June 20, 2019, demonstrates and position the United States to defend U.S. forces and interests in the region.75 Iranian attacks after previous U.S. deployments could be viewed to suggest that deploying additional assets and capabilities hasmight not necessarily succeededsucceed in deterring Iran from using military force.

Still others contend that the risks ofOn the other hand, there are risks to military inaction are greater thanthat might potentially outweigh those associated with the employment of force. For example, should Iran acquire a nuclear weapons capability, U.S. options to contain and dissuade it from prosecuting hostile activities could be significantly more constrained than they are at present.7476

For illustrative purposes only, below are some potential additional policy options related to the possible use of military capabilities against Iran, beyond the Gulf shipping protection mission the United States is establishingIMSC discussed above. Not all of these options are mutually exclusive, nor do they represent a complete list of possible options, implications, and risks. And, the escalation of U.S.-Iran tensions has prompted Congress to assessCongress has assessed its role in any decisions regarding whether to undertake military action against Iran, an issue that isas discussed later in this report. The following discussion is based entirely on open-source materials.

- Operations against Iranian allies or proxies. The Administration might decide to take action against Iran's allies or proxies, such as Iran-backed militias in Iraq, Lebanese Hezbollah, or the Houthi movement in Yemen. Such action could take the form of air operations, ground operations, special operations, or cyber and electronic warfare. Attacks on Iranian allies could be limited or expansive—intended to seriously degrade the military ability of the Iranian ally in question

. Options to combat Iran's allies could be—and undertaken by U.S. forces, partner government forces, or both.On the other handAt the same time, military action against Iran's allies couldIran's allies has the potential to further inflame orharm the prospects for resolution of U.S.-Iran tensions or the regional conflicts in which Iranian allies operate. - Retaliatory Action against Iranian Key Targets and Facilities. The United States retains the option to undertake air and missile strikes, as well as special operations and cyber and electronic warfare against Iranian targets, such as IRGC Navy vessels in the Gulf, nuclear facilities, military bases, ports

(seeFigure 1), oil installations, and any number of other targets within Iran itself.7577 - Blockade. Another option could be to establish a naval and/or air quarantine of Iran. Iran has periodically, including in the latest round of tensions, threatened to block the vital Strait of Hormuz. Some observers have in past confrontations raised the prospect of a U.S. closure of the Strait or other waterways to Iranian commerce.

7678 Under international law, blockades are acts of war. - Invasion. Although apparently far from current consideration because of the potential risks and costs, a U.S. invasion of Iran to oust its regime is among the options. Press reports in May 2019 indicated that the Administration was considering adding more than 100,000 military forces to the Gulf to deter Iran from any attacks.

7779 Such an option, if exercised, might be interpreted as potentially enhancing the U.S. ability to conduct ground attacks inside Iran, althoughmostmilitary expertsindicatehave indicated that a U.S. invasion and/or occupation of Iran would require many more U.S. forces than those cited.7880 Iran's population is about 80 million, and its armed forces collectively number about 525,000, including 350,000 regular military and 125,000 IRGC forces.7981 There has been significant antigovernment unrest in Iran over the past 10 years, including in November 2019, but there is no indication that there is substantial support inside Iran for a U.S. invasion to change Iran's regime.

Resource Implications of Military Operations

Without a more detailed articulation of how the military might be employed to accomplish U.S. objectives vis-a-vis Iran, and a reasonable level of confidence about how any conflict might proceed, it is difficult to assess with any precision the likely fiscal costs of a military campaign, or even just heightened presence. Still, any course of action listed in this report is likely to incur significant additional costs. Factors that might influence the level of expenditure required to conduct operations include, but are not limited to, the following:

- The number of additional forces, and associated equipment, deployed to the Persian Gulf or the CENTCOM theater more broadly. In particular, deploying forces and equipment from the continental United States (if required) would likely add to the costs of such an operation due to the logistical requirements of moving troops and materiel.

- The mission set that U.S. forces are required to prosecute and its associated intensity. For example, some options leading to an increase of the U.S. posture in the Persian Gulf for deterrence or containment purposes might require upgrading existing facilities or new construction of facilities and installations. By contrast, options that require the prosecution of combat operations would likely result in significant supplemental and/or overseas contingency operations requests, particularly if U.S. forces are involved in ground combat or

postconflictpost-conflict stabilization operations. - The time required to accomplish U.S. objectives. As demonstrated by operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, the period of anticipated involvement in a contingency is a critical basis for any cost analysis. On one hand, a large stabilizing or occupying ground force to perform stabilization and reconstruction operations, for example, would likely require the expenditure of significant U.S. resources. On the other hand, a limited strike that does not result in conflict escalation would likely be relatively less expensive to the United States.

At the same time, there is potential for some U.S. costs to be offset by contributions. The Persian Gulf states and other countries have a track record of offsetting U.S. costs for Gulf security. In the current context, President Trump stated in October 2019 that Saudi Arabia would pay for the deployment of additional U.S. troops and capabilities to assist with the territorial defense of Saudi Arabia and the deterrence of Iranian aggression in the region overall, and subsequent reports indicate that U.S. and Saudi officials are negotiating a cost-sharing arrangement for the new deployments.82

Congressional Responses

Members of Congress have responded in various ways to increased tensions with Iran and to related questions of authorization for the use of military force.

President Trump said in a June 24 interview that he believes he has the authority to direct strikes against Iran, and said, "I do like keeping them [Congress] abreast, but I don't have to do it, legally."86 On June 25, he tweeted that "any attack by Iran on anything American will be met with great and overwhelming force. In some areas, overwhelming will mean obliteration."87 The prospect of U.S. military action against Iran in the wake of the September attacks on Saudi oil facilities at Abqaiq and Khurais prompted additional responses from several Members of Congress. President Trump's statement that the United States was "locked and loaded" but "waiting to hear from the Kingdom as to who they believe was the cause of this attack, and under what terms we would proceed" drew particular congressional attention, with several Members emphasizing, as Representative Cicilline wrote, that "If the President wants to use military force, he needs Congress—not the Saudi royal family—to authorize it."88 Other Members, while generally backing the Administration's assessment that Iran was behind the attacks, argued that time should be given to verify intelligence conclusions.89 Senator Graham described the attack on Abqaiq and Khurais as "literally an act of war" that Iran committed because it interpreted the President's decision to call off airstrikes in response to the June drone shootdown as a "sign of weakness"; President Trump rejected that characterization, describing his approach as "a sign of strength that some people just don't understand!"90 The buildup of U.S. forces in the region in response to Iranian activities has also attracted congressional attention. At a December 5, 2019, hearing with Under Secretary of Defense for Policy John Rood, Senator Josh Hawley said the Pentagon had "made multiple contradictory public statements" with regard to reports of additional U.S. force deployments. Senator Hawley also pressed Under Secretary Rood on "what it is exactly that we're aiming to deter," arguing that "regional stability and the absence of an attack on American forces are…very different" and that "if our aim is to prevent all conflict in the region, we're going to be sending a lot more than 14 or 28 or 100,000 ground troops."91 Section 1227 of the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (S. 1790), which has been reported out by the conference committee on the legislation and passed by the House, would require an Administration report to Congress on diplomatic and military channels of deconfliction with Iran to "prevent miscalculation" that could "lead to unintended consequences, including unnecessary or harmful military activity."Some Members have In June 2019, amidst attacks against tankers in the Gulf of Oman and Iran's shootdown of a U.S. military drone, some Members expressed concern about the legal justification for military operations in or against Iran. On June 22, Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) cast doubt on the notion of a "limited strike," saying that "[attacking] another country with bombs ... that's an act of warfare" and said that an attack on Iran would be, in his view, "unconstitutional."80 83 Other Members positioned themselves as more generally supportive of broad discretion for the Administration to act. Senator Tom Cotton said on June 16 that "these unprovoked attacks on commercial shipping warrant a retaliatory military strike" and argued that the President had the authority to order such an attack.84 The day before, Senator Lindsey Graham made a similar argument, stating that "enough is enough" and called on President Trump to "be prepared to make Iran pay a heavy price by targeting their naval vessels and, if necessary, their oil refineries."85

8192 For instance, Section 9026 of Division C of H.R. 2740 (the Department of Defense Appropriations Act, 2020), as engrossed in the House on June 19, 2019, stateswould state that "Nothing in this Act may be construed as authorizing the use of force against Iran." H.R. 2500, the National Defense Authorization Act for FY2020, as reported in the House on June 19, 2019, contains a similar provision (Section 1225). On July 12, 2019, the House also passed, by a vote of 251-170, an amendment to H.R. 2500 that would prohibit funding for the use of force against Iran, with provisions clarifying that such a prohibition would not prevent the President from using necessary and appropriate force to defend U.S. allies and partners, consistent with the War Powers Resolution.

Other Members have positioned themselves as more generally supportive of broad discretion for the Administration to act. Senator Tom Cotton (R-AR) said on June 16 that "these unprovoked attacks on commercial shipping warrant a retaliatory military strike" and argued that the President had the authority to order such an attack.82 The day before, Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC) made a similar argument, stating that "enough is enough" and called on President Trump to "be prepared to make Iran pay a heavy price by targeting their naval vessels and, if necessary, their oil refineries."83 On June 28, 2019, the Senate rejected by a 50-40 vote an amendment (S.Amdt. 883) to the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act that would have prohibited the use of any funds to "conduct hostilities against the Government of Iran, against the Armed Forces of Iran, or in the territory of Iran, except pursuant to an Act or joint resolution of Congress specifically authorizing such hostilities."84

President Trump said in a June 24 interview that he believes he has the authority to direct strikes against Iran, and said that "I do like keeping them [Congress] abreast, but I don't have to do it, legally."85 On June 25, he tweeted that "any attack by Iran on anything American will be met with great and overwhelming force. In some areas, overwhelming will mean obliteration."86Neither provision was included in the conference report, as passed by the House in December 2019.

On June 28, 2019, the Senate rejected by a 50-40 vote an amendment (S.Amdt. 883) to the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act that would have prohibited the use of any funds to "conduct hostilities against the Government of Iran, against the Armed Forces of Iran, or in the territory of Iran, except pursuant to an Act or joint resolution of Congress specifically authorizing such hostilities."93

At a Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing on April 10, 2019, Secretary of State Pompeo, when asked if the Administration considers the use of force against Iran as authorized, answered that he would defer to Administration legal experts on that question. However, he suggested that the 2001 authorization for use of military force (AUMF, P.L. 107-40) against those responsible for the September 11 terrorist attacks could potentially apply to Iran, asserting that "[Iran has] hosted Al Qaida. They have permitted Al Qaida to transit their country. [There's] no doubt there is a connection between the Islamic Republic of Iran and Al Qaida. Period. Full stop." Other analyses have characterized the relationship between Iran and Al Qaeda as "an on-again, off-again marriage of convenience pockmarked by bouts of bitter acrimony."8794 As passed by the House, Section 9025 of H.R. 2740 would repeal the 2001 AUMF within 240 days of enactment.8895

In a June 28, 2019, letter to House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Eliot Engel, Assistant Secretary of State for Legislative Affairs Mary Elizabeth Taylor stated that "the Administration has not, to date, interpreted either [the 2001 or 2002] AUMF as authorizing military force against Iran, except as may be necessary to defend U.S. or partner forces engaged in counterterrorism operations or operations to establish a stable, democratic Iraq." In response, Chairmen Engel and Middle East Subcommittee Chairman Ted Deutch welcomed the Administration's apparent acknowledgment that "the 2001 and 2002 war authorizations do not apply to military action against Iran," but cautioned that "the Administration claims that the President could use these authorizations to attack Iran in defense of any third party he designates a partner."8996 In reviewing the letter, two analysts have suggested additional related topics for potential congressional oversight, including which groups are carrying out such counterterrorism operations, where they are doing so, and what nations or groups threaten them.9097

Additionally, some Members seeking to prevent the Administration from pursuing military action against Iran have introduced several standalone measures prohibiting the use of funds for such operations, such as the Prevention of Unconstitutional War with Iran Act of 2019 (H.R. 2354/S. 1039) which would prevent the use of any funds for "kinetic military operations in or against Iran" except in case of an imminent threat.

Possible Issues for Congress

Given ongoing tensions with Iran, Members are likely to continue to assess and perhaps try to shape the congressional role in any decisions regarding whether to commit U.S. forces to potential hostilities. In assessing its authorities in this context, Congress might consider, among other things, the following:

- Does the President require prior authorization from Congress before initiating hostilities with Iran? If so, what actions, under what circumstances, ought to be covered by such an authorization? If not, what existing authorities provide for the President to initiate hostilities?

- If the executive branch were to initiate and then sustain hostilities against Iran without congressional authorization, what are the implications for the preservation of Congress's role, relative to that of the executive branch, in the war powers function? How, in turn, might the disposition of the war powers issue in connection with the situation with Iran affect the broader question of Congress's status as an equal branch of government, including the preservation and use of other congressional powers and prerogatives?

- The Iranian government may continue to take aggressive action short of directly threatening the United States and its territories while it continues policies opposed by the United States. What might be the international legal ramifications for undertaking a retaliatory, preventive, or preemptive strikes against Iran in response to such actions without a U.N. Security Council mandate?

Conflict with, or increased military activity in or around, Iran could generate significant financial costscosts, financial and otherwise. With that in mind, Congress could consider the following:

- The potential costs of heightened U.S. operations in the CENTCOM area of operations, particularly if they lead to full-scale war and significant postconflict operations.

- The need for the United States to reconstitute its forces and capabilities, particularly in the aftermath of a major conflict.

- The impact of the costs of war and post conflict reconstruction on U.S. deficits and government spending.

- The costs of persistent military confrontation and/or a conflict in the Gulf region to the global economy.

- The extent to which regional allies, and the international community more broadly, might contribute forces or resources to a military campaign or its aftermath.

|

|

|

Sources: Created by CRS using data from the U.S. Department of State, ESRI, and GADM. |

Appendix A.

Selected Statements by U.S. and Iranian Leaders on Recent Tensions91

|

Date in 2019 |

U.S. Statements |

Iranian Statements |

|

April 22 |

Pompeo: "We have watched Iran have diminished power as a result of our campaign. Their capacity to wreak harm around the world is absolutely clearly diminished." |

|

|

April 24 |

FM Zarif: "It is not a crisis yet, but it is a dangerous situation. Accidents, plotted accidents are possible.... The plot is to push Iran into taking action. And then use that." |

|

|

April 30 |

Rouhani: "America's decision that Iran's oil exports must reach zero is a wrong and mistaken decision, and we won't let this decision be executed and operational.... In future months, the Americans themselves will see that we will continue our oil exports." |

|

|

May 5 |

National Security Advisor John Bolton statement: "In response to a number of troubling and escalatory indications and warnings, the United States is deploying the USS Abraham Lincoln Carrier Strike Group and a bomber task force to the U.S. Central Command region to send a clear and unmistakable message to the Iranian regime that any attack on United States interests or on those of our allies will be met with unrelenting force. The United States is not seeking war with the Iranian regime, but we are fully prepared to respond to any attack, whether by proxy, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, or regular Iranian forces." |

|

|

May 8 |

President Rouhani (via Twitter): "Starting today, Iran does not keep its enriched uranium and produced heavy water limited. The EU/E3+2 will face Iran's further actions if they can not fulfill their obligations within the next 60 days and secure Iran's interests. Win-Win conditions will be accepted." |

|

|

May 9 |

President Trump: "I'd like to see [Iran] call me" to "make a deal, a fair deal" |

|

|

May 12 |

Rouhani: "The pressures by enemies is a war unprecedented in the history of our Islamic revolution ... but I do not despair and have great hope for the future and believe that we can move past these difficult conditions provided that we are united." |

|

|

May 14 |

Supreme Leader Khamenei: "There won't be any war. The Iranian nation has chosen the path of resistance" |

|

|

May 19 |

President Trump (via Twitter): "If Iran wants to fight, that will be the official end of Iran. Never threaten the United States again!" |

|

|

May 20 |

President Trump (via Twitter): "Iran will call us if and when they are ever ready. In the meantime their economy continues to collapse—very sad for the Iranian people!" |

Rouhani: "Today's situation is not suitable for talks and our choice is resistance only." |

|

May 27 |

President Trump: "I really believe that Iran would like to make a deal, and I think that's very smart of them, and I think that's a possibility to happen.... It has a chance to be a great country with the same leadership.... We aren't looking for regime change—I just want to make that clear. We are looking for no nuclear weapons." |

|

|

May 29 |

NSA Bolton: "I think it is clear these [tanker attacks] were naval mines almost certainly from Iran.... There is no doubt in anybody's mind in Washington who was responsible for this." |

Supreme Leader Khamenei (via Twitter): "We won't negotiate with Americans. Because there's no use negotiating and it's even harmful. Otherwise we have no problems negotiating with others & with Europeans." |

|

June 2 |

Pompeo: "We are prepared to engage in conversation with no preconditions, we are ready to sit down" with Iran. |

|

|

June 13 |

President Trump (via Twitter): "While I very much appreciate [Japanese Prime Minister] Abe going to Iran to meet with Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, I personally feel it is too soon to even think about making a deal. They are not ready, and neither are we!" Pompeo: "Iran is lashing out because the regime wants our successful maximum pressure campaign lifted.... Our policy remains an economic and diplomatic effort to bring Iran back to the negotiating table at the right time, to encourage a comprehensive deal that addresses the broad range of threats—threats today apparent for all the world to see—to peace and security." |

Supreme Leader Khamenei (via Twitter): "We have no doubt in [PM Abe's] goodwill and seriousness; but regarding what you mentioned from U.S. president, I don't consider Trump as a person deserving to exchange messages with; I have no response for him & will not answer him." |

|

June 17 |

President Trump, on alleged Iranian attacks in the Gulf: "So far, it's been very minor" |

|

|

June 20 |

President Trump: "I find it hard to believe [Iran shooting down a U.S. drone] was intentional.... I have a feeling that it was a mistake made by somebody that shouldn't have been doing what they did." |

|

|

June 21 |

President Trump: "I'm not looking for war, and if there is, it'll be obliteration like you've never seen before." |

|

|

June 22 |

President Trump: "We're not going to have Iran have a nuclear weapon. And when they agree to that, they are going to have a wealthy country, they're going to be so happy and I'm going to be their best friend." |

|

|

June 25 |