Iraq: Background and U.S. Policy

The 115th Congress and the Trump Administration are considering options for U.S. engagement with Iraq as Iraqis look beyond the immediate security challenges posed by their intense three-year battle with the insurgent terrorists of the Islamic State organization (IS, aka ISIL/ISIS). While Iraq’s military victory over Islamic State forces is now virtually complete, Iraq’s underlying political and economic challenges are daunting and cooperation among the forces arrayed to defeat IS extremists has already begun to fray. The future of volunteer Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) and the terms of their integration with Iraq’s security sector are being determined, with some PMF groups maintaining ties to Iran and anti-U.S. Shia Islamist leaders. In September 2017, Iraq’s constitutionally recognized Kurdistan Regional Government held an advisory referendum on independence, in spite of opposition from Iraq’s national government and amid its own internal challenges. More than 90% of participants favored independence.

With preparations for national elections in May 2018 underway, Iraqi leaders face the task of governing a politically divided and militarily mobilized country, prosecuting a likely protracted counterterrorism campaign against IS remnants, and tackling a daunting resettlement, reconstruction, and reform agenda. More than 3 million Iraqis have been internally displaced since 2014, and billions of dollars for stabilization and reconstruction efforts have been identified. Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al Abadi is linking his administration’s decisions with gains made to date against the Islamic State, but his broader reform platform has not been enacted by Iraq parliament. Oil exports, the lifeblood of Iraq’s public finances and economy, are bringing diminished revenues relative to 2014 levels, leaving Iraq’s government more dependent on international lenders and donors to meet domestic obligations.

The United States has strengthened its ties to Iraq’s security forces and provided needed economic and humanitarian assistance since 2014, but Iraqis continue to disagree over how U.S.-Iraqi relations should evolve. President Trump and Prime Minister Abadi met in Washington, DC, in March 2017 and, according to the White House, “agreed to promote a broad-based political and economic partnership based in the [2008] Strategic Framework Agreement,” including continued security cooperation. Some Iraqis have welcomed U.S. engagement with and assistance to Iraq, whereas other Iraqis view the United States with hostility and suspicion for various reasons. Prime Minister Abadi has expressed the desire for the United States to provide continued support and training for Iraq’s security forces, but some Iraqis—particularly those with close ties to Iran—are deeply critical of proposals for a continued U.S. military presence in the country. U.S. decisions on issues such as policy toward Iran, the conflict in Syria, the Israel-Palestinian conflict, and U.S. relations with Iraqi Kurds and other subnational groups may influence future bilateral negotiations and prospects for cooperation.

Congress has authorized a Defense Department train and equip program for Iraqi security forces through December 31, 2019, and has appropriated more than $3.6 billion requested for the program from FY2015 through FY2017, including funds specifically for the equipping and sustainment of Kurdish peshmerga. U.S. military operations against the Islamic State continue with the consent of Iraq’s elected government. Congress has authorized the use of FY2017 funds for sovereign loan guarantees to Iraq and for continued lending for Iraqi arms purchases from the United States. President Trump has requested $1.269 billion to train Iraqis for FY2018 and seeks $347.86 million for foreign aid to Iraq, including $300 million for further U.S. contributions to United Nations-coordinated post-IS stabilization efforts. Appropriations and authorization legislation enacted and under consideration in the 115th Congress generally would provide for the continuation of U.S. assistance and engagement with Iraq on current terms (H.R. 2810, H.R. 3354, S. 1780 and S. 1519).

Iraq: Background and U.S. Policy

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Overview

- Developments in 2017

- Progress in the Fight against the Islamic State

- Confrontation over Kurdish Referendum and Disputed Territories

- Iran and Iraq's Popular Mobilization Forces

- U.S. Foreign Aid and Security Assistance

- Political and Economic Profile

- Identity, Governance, and Politics

- The Rise and Retreat of the Islamic State

- The 2014 Election, the Abadi Government, and Reform Debates

- Dynamics in 2017 and Preparations for 2018 Elections

- Politics and Potential Coalitions

- The Kurdistan Region of Iraq

- Kurdish Politics

- Uncertainty and Confrontation in Iraq's Disputed Territories

- Energy Resources

- Fiscal Challenges and Economic Conditions

- IMF Stand-by Arrangement

- Fiscal Issues in the Kurdistan Region

- Humanitarian Conditions

- Conditions in the Kurdistan Region

- Conditions for Minority Groups

- After the Islamic State: Security and Stabilization

- Issues for the 115th Congress

- U.S. Strategy and Engagement

- Defeating the Islamic State and Defining Future Security Partnership

- Relations with the Kurdistan Region and other Subnational Entities

- Iran's Relationship with Iraq

- Military Operations

- U.S. Assistance and Related Legislation

- Train and Equip Efforts

- Lending Support for Iraq's Security Sector

- Stabilization Programs

- Governance and Fiscal Support

- Humanitarian Assistance

- De-mining and Unexploded Ordnance Removal

- Arms Sales and the Office of Security Cooperation

- Select Areas of U.S. Concern

- Governance and Corruption

- Human Rights

- Religious and Ethnic Minorities

- Child Soldiers

- Outlook

Figures

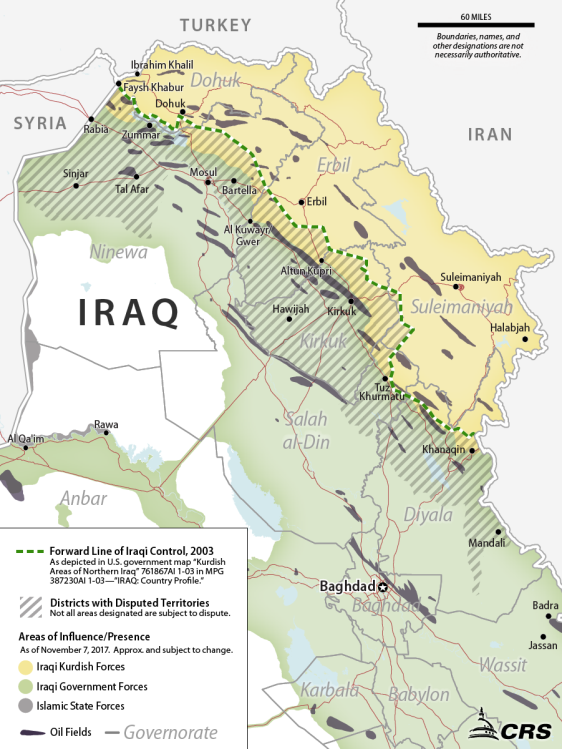

- Figure 1. Relative Areas of Islamic State Influence and Operation, 2015-2017

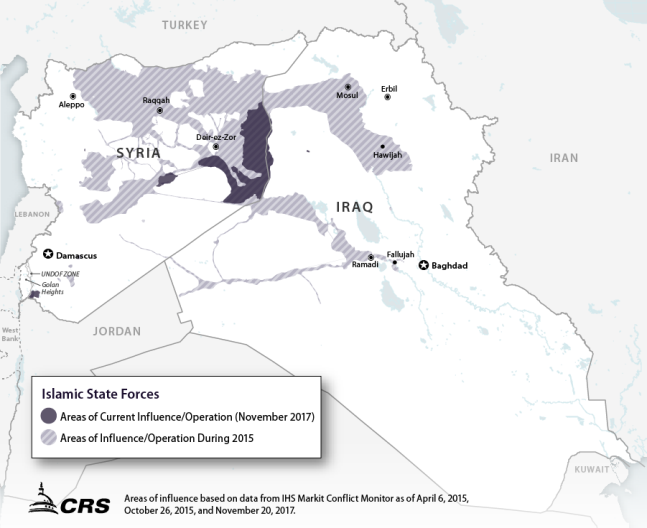

- Figure 2. Iraq: Areas of Influence and Presence

- Figure 3. Iraq: Select Political and Religious Figures

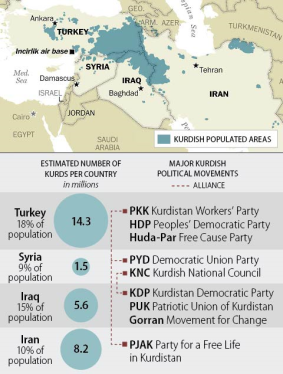

- Figure 4. Kurds in Iraq and Neighboring Countries

- Figure 5. Iraq: Disputed Territories

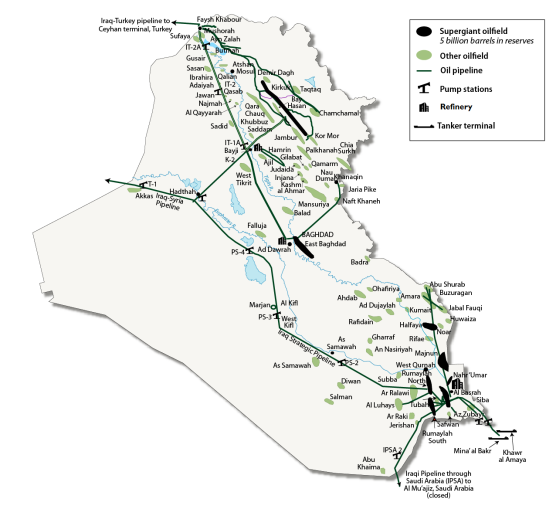

- Figure 6. Location of Iraq's Oil Reserves and Infrastructure

Tables

Summary

The 115th Congress and the Trump Administration are considering options for U.S. engagement with Iraq as Iraqis look beyond the immediate security challenges posed by their intense three-year battle with the insurgent terrorists of the Islamic State organization (IS, aka ISIL/ISIS). While Iraq's military victory over Islamic State forces is now virtually complete, Iraq's underlying political and economic challenges are daunting and cooperation among the forces arrayed to defeat IS extremists has already begun to fray. The future of volunteer Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) and the terms of their integration with Iraq's security sector are being determined, with some PMF groups maintaining ties to Iran and anti-U.S. Shia Islamist leaders. In September 2017, Iraq's constitutionally recognized Kurdistan Regional Government held an advisory referendum on independence, in spite of opposition from Iraq's national government and amid its own internal challenges. More than 90% of participants favored independence.

With preparations for national elections in May 2018 underway, Iraqi leaders face the task of governing a politically divided and militarily mobilized country, prosecuting a likely protracted counterterrorism campaign against IS remnants, and tackling a daunting resettlement, reconstruction, and reform agenda. More than 3 million Iraqis have been internally displaced since 2014, and billions of dollars for stabilization and reconstruction efforts have been identified. Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al Abadi is linking his administration's decisions with gains made to date against the Islamic State, but his broader reform platform has not been enacted by Iraq parliament. Oil exports, the lifeblood of Iraq's public finances and economy, are bringing diminished revenues relative to 2014 levels, leaving Iraq's government more dependent on international lenders and donors to meet domestic obligations.

The United States has strengthened its ties to Iraq's security forces and provided needed economic and humanitarian assistance since 2014, but Iraqis continue to disagree over how U.S.-Iraqi relations should evolve. President Trump and Prime Minister Abadi met in Washington, DC, in March 2017 and, according to the White House, "agreed to promote a broad-based political and economic partnership based in the [2008] Strategic Framework Agreement," including continued security cooperation. Some Iraqis have welcomed U.S. engagement with and assistance to Iraq, whereas other Iraqis view the United States with hostility and suspicion for various reasons. Prime Minister Abadi has expressed the desire for the United States to provide continued support and training for Iraq's security forces, but some Iraqis—particularly those with close ties to Iran—are deeply critical of proposals for a continued U.S. military presence in the country. U.S. decisions on issues such as policy toward Iran, the conflict in Syria, the Israel-Palestinian conflict, and U.S. relations with Iraqi Kurds and other subnational groups may influence future bilateral negotiations and prospects for cooperation.

Congress has authorized a Defense Department train and equip program for Iraqi security forces through December 31, 2019, and has appropriated more than $3.6 billion requested for the program from FY2015 through FY2017, including funds specifically for the equipping and sustainment of Kurdish peshmerga. U.S. military operations against the Islamic State continue with the consent of Iraq's elected government. Congress has authorized the use of FY2017 funds for sovereign loan guarantees to Iraq and for continued lending for Iraqi arms purchases from the United States. President Trump has requested $1.269 billion to train Iraqis for FY2018 and seeks $347.86 million for foreign aid to Iraq, including $300 million for further U.S. contributions to United Nations-coordinated post-IS stabilization efforts. Appropriations and authorization legislation enacted and under consideration in the 115th Congress generally would provide for the continuation of U.S. assistance and engagement with Iraq on current terms (H.R. 2810, H.R. 3354, S. 1780 and S. 1519).

Overview

Iraqis have persevered through intermittent wars, internal conflicts, sanctions, displacements, unrest, and terrorism for decades. A 2003 U.S.-led invasion ousted the dictatorial government of Saddam Hussein and ended the decades-long rule of the Baath Party. This created an opportunity for Iraq to establish new democratic, federal political institutions and reconstitute its security forces, but it also ushered in a period of chaos, violence, and political transition from which the country is still emerging. Latent tensions among Iraqis that were suppressed and manipulated under the Baath regime became amplified in the wake of its collapse. Political parties, ethnic groups, and religious communities competed with rivals and amongst themselves for influence in the post-2003 order, amid sectarian violence, insurgency, and terrorism. Misrule, foreign interference, and corruption also took a heavy toll on Iraqi society during this period, and continue to undermine public trust and social cohesion.

In 2011, when the United States completed an agreed military withdrawal, Iraq's gains proved fragile. Security conditions deteriorated from 2012 through 2014, as the insurgent terrorists of the Islamic State organization (IS, aka ISIS/ISIL)—the successor to Al Qaeda-linked groups active during the post-2003 transition—drew strength from conflict in neighboring Syria and seized large areas of northern and western Iraq. Since 2014, war against the Islamic State has dominated events in Iraq, and many pressing social, economic, and governance challenges remain to be addressed. (See Table 1 below for basic data.)

Iraqis are now celebrating the considerable successes their security forces and foreign partners have achieved in the fight against the Islamic State (see Figure 1), while warily eyeing a potentially fraught political path ahead. National legislative and governorate elections are planned for May 2018. Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al Abadi appears well positioned to campaign for reelection, although rivals from other Shia political factions may contest his leadership. Such potential challengers include former prime minister Nouri al Maliki and some figures associated with Iran-backed militia forces that are part of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) mobilized to fight the Islamic State. Some Iraqi parties and individuals oppose a continued U.S military presence in Iraq and may scrutinize U.S.-Iraqi security cooperation during the election period.

The Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) maintains considerable administrative autonomy under Iraq's constitution, and held a controversial advisory referendum on independence from Iraq on September 25, 2017. From mid-2014 through October 2017, Kurdish forces controlled many areas that had been subject to territorial disputes with national authorities prior to the Islamic State's 2014 advance, including much of the oil-rich governorate of Kirkuk. However, in October 2017, Iraqi government forces moved to reassert security control in many of these areas, leading to some armed confrontations and casualties on both sides and setting back Kurdish aspirations for independence.

Across Iraq, including in the KRI, long-standing popular demands for improved service delivery, security, and effective, honest governance remain widespread. Stabilization and reconstruction needs in areas liberated from the Islamic State are extensive. Paramilitary forces mobilized to fight IS terrorists have grown stronger and more numerous since the Islamic State's rapid advance in 2014, but have yet to be fully integrated into national security institutions. Iraqis are grappling with these political and security issues in an environment shaped by ethnic, religious, regional, and tribal identities, partisan and ideological differences, personal rivalries, economic disparities, and natural resource imbalances. Iraq's neighbors and other international powers are actively pursuing their diplomatic, economic, and security interests in the country.

|

|

|

Area:438,317 sq km (slightly more than three times the size of New York State) Population:38.146 million (July 2016 estimate), ~60% under the age of 24 Internally Displaced Persons: 3.316 million (July 15, 2017) Religions:Muslim 99% (55-60% Shia, 40% Sunni), Christian <0.1%, Yazidi <0.1% Ethnic Groups: Arab 75-80%; Kurdish 15-20%; Turkmen, Assyrian, Shabak, Yazidi, other ~5%. Gross Domestic Product (GDP; growth rate): $173 billion; 10.3% (2016 est.) Budget (revenues; expenditure; balance): $67.8 billion, $86.34 billion, -$18.54 billion (2017 est.) Percentage of Revenue from Oil Exports: 87% (June 2017 est.) Current Account Balance: -$12.2 billion (2016 est.) Oil and natural gas reserves: 143 billion barrels (2016 est., fifth largest); 3.158 trillion cubic meters (2016 est.) External Debt: $68.01 billion (2016 est.) Foreign Reserves: ~$44.15 billion (December 2016 est.) |

Source: Graphic created by CRS using data from U.S. State Department and Esri. Country data from CIA World Factbook, July 2017, Iraq Ministry of Finance, and International Organization for Migration.

|

Figure 1. Relative Areas of Islamic State Influence and Operation, 2015-2017 |

|

|

Source: CRS, using data from ESRI, IHS Markit, U.S. government, and United Nations. |

|

Figure 2. Iraq: Areas of Influence and Presence As of November 20, 2017 |

|

|

Source: CRS, using data from ESRI, IHS Markit, U.S. government, and United Nations. |

Iraq's strategic location, its potential, and its diverse population with ties to neighboring countries underlie its importance as an area of influence to U.S. policymakers. In general, U.S. engagement with Iraqis since 2011 has sought to reinforce Iraq's unifying tendencies and avoid divisive outcomes. At the same time, successive Administrations have sought to keep U.S. involvement and investment minimal relative to the 2003-2011 era, pursuing U.S. interests through partnership with various entities in Iraq and the development of those partners' capabilities—rather than through extensive deployment of U.S. military forces.

The Trump Administration has sustained a cooperative relationship with the Iraqi government and has requested funding to continue security training for Iraqi forces beyond the completion of major military operations against the Islamic State. With those operations coming to a conclusion, the mission and nature of the U.S. military presence in Iraq is expected to evolve. U.S. officials and military personnel have discussed general plans to remain in Iraq at the invitation of the Iraqi government in order to assist Iraqis in consolidating gains made to date and to train security forces.1 The 115th Congress has appropriated funds for ongoing U.S. military operations, in addition to security assistance, humanitarian relief, and foreign aid for Iraq. Congress is considering appropriations and authorization bills for FY2018 that would largely continue U.S. policies and programs on current terms. The goals, scope, and terms of some assistance are subject to debate and may evolve in relation to conditions in Iraq.

Developments in 2017

Progress in the Fight against the Islamic State

In July 2017, Prime Minister Haider al Abadi visited Mosul to mark the completion of major combat operations there against Islamic State forces, which had taken the city in June 2014. Iraqi forces launched operations to retake Mosul in October 2016 and seized the eastern half of the city in January 2017. They then began operations in the city's more densely populated western half in February. Fighting in west Mosul resulted in greater displacement, casualties, and destruction of buildings and infrastructure than in the east, with some estimates of the city's overall reconstruction needs exceeding $1 billion.2 Estimates suggest thousands of civilians were killed or wounded during the battle, which displaced more than 1 million people.3

The defeat of IS forces in Mosul left the group with isolated areas of control in Tal Afar in Ninewa governorate, near Hawijah in Kirkuk and adjacent governorates, and in far western Anbar governorate (see Figure 2, above). Iraqi forces have since retaken Tal Afar and Hawijah, and launched new Anbar operations in late October amid tensions elsewhere in the disputed territories between the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and national authorities. Prime Minister Abadi visited the western border town of Al Qaim in November and raised the Iraqi flag, and in mid-November Iraqi officials announced they had retaken Rawa, the last large populated area held by IS fighters in Iraq. With IS control over distinct territories of Iraq now virtually ended, analysts expect IS leaders and fighters to shift toward insurgency tactics and avoid major confrontations in coming weeks and months. Experts warn that the group's resiliency and its ability to use such tactics effectively should not be underestimated.

Confrontation over Kurdish Referendum and Disputed Territories

On June 7, 2017, Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) President Masoud Barzani announced that the KRG would hold an official advisory referendum on independence from Iraq on September 25.4 Iraqi Prime Minister Abadi called the proposed referendum unconstitutional and requested that it be delayed or cancelled in favor of resolving KRG-Baghdad differences through dialogue. The United States government, other countries and international observers, and some of Iraq's neighbors adopted that same position.5 KRG President Barzani and other leading Kurds described the proposed referendum as an inherent right of the Kurdish people in pursuit of self-determination. Enthusiasm among some Kurds for the referendum reflected long-stated desires in an environment in which security and economic circumstances were more favorable than in the past because of post-2014 developments. However, KRG leaders said they intended to pursue separation negotiations with Baghdad after the referendum, raising the potential stakes of preexisting territorial and resource disputes and contributing to concern among Iraqi critics.

In spite of U.S. and Iraqi opposition, Kurdish leaders held the referendum on time and as planned. According to Kurdish authorities, more than 72% of eligible voters participated and, of those votes deemed valid, roughly 92% were "Yes" votes and about 7% were "No" votes.6 In the wake of the referendum, Prime Minister Abadi has reiterated the national government's view that the referendum was "unconstitutional," and he and Iraq's national legislature and courts have called for its results to be "cancelled."7 Iraqi authorities also moved to begin reasserting national government control over all border crossings and the airspace of the KRI. Kurdish officials decried the measures, describing them as collective punishment and an attempt to institute a blockade.

The September 25 referendum was held across the KRI and in other areas that were then under the control of Kurdish forces, including some areas subject to territorial disputes between the KRG and the national government, such as the multiethnic city of Kirkuk, adjacent oil-rich areas, and parts of Ninewa governorate populated by religious and ethnic minorities. Kurdish forces had secured many of these areas following the retreat of national government forces in the face of the Islamic State's rapid advance across northern Iraq in 2014. In October 2017, Prime Minister Abadi ordered Iraqi forces to return to the disputed territories that had been under the control of national forces prior to the Islamic State's advance, including Kirkuk. A handful of clashes resulted in some casualties on both sides, but Kurdish forces—to some extent divided among themselves over the wisdom of the referendum and relations with Baghdad—mostly withdrew without incident. The involvement of some Iran-backed Popular Mobilization Force militia units in Iraqi national forces' operations has fueled concerns about Iranian influence in Iraq, as have reports about attempts by Iranian officials to pressure Kurdish leaders over the disputed territories.

Changes in territorial control in the disputed territories since October have upended the Kurds' financial and political prospects, and related disputes have fueled further division among Kurdish leaders and parties. Some oil fields and infrastructure that had been under Kurdish control has been retaken by national government forces, and Kurdish leaders have traded recriminations and accusations of malpractice and betrayal. KRG President Barzani—who, along with his Kurdistan Democratic Party faction, was considered the driving force behind the referendum—announced that he will not seek reelection and directed that the authority of his office be exercised by other KRG entities until elections are held. In late October, the Kurdistan National Assembly voted to delay elections that had been planned for November for at least eight months.

U.S. officials continue to encourage Kurds and other Iraqis to engage on outstanding issues of dispute and to avoid unilateral military actions that could further destabilize the situation. U.S. assistance to the KRG since 2014 has been provided with the national government's consent, and the Trump Administration has not publicly signaled any planned changes in U.S. assistance programs for either the national government or the Kurdistan region.

For background, see "The Kurdistan Region of Iraq" and "Uncertainty and Confrontation in Iraq's Disputed Territories" below.

Iran and Iraq's Popular Mobilization Forces

Since its founding in 2014, Iraq's Popular Mobilization Commission (PMC) and its associated militias—the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF)—have contributed to Iraq's fight against the Islamic State, even as some of its leaders and units have raised concerns among Iraqis and outsiders about the PMF's future. In early July 2017, the U.N. Secretary-General reported to the Security Council that "no tangible progress" had been made in the implementation of the PMF law that Iraqis adopted in late 2016 to provide for a permanent role for the PMF as an element of Iraq's national security sector. The law calls for the PMF to be placed under the command authority of the commander-in-chief and to be subject to military discipline and organization.

Some PMF units have since been integrated, but many remain outside the law's directive structure, including some units associated with groups identified by the State Department's 2016 Country Reports on Terrorism as receiving Iranian support.8 The report mentions Asa'ib Ahl al Haq and the Badr forces in this regard and warns specifically that the permanent inclusion of the U.S.-designated foreign terrorist organization (FTO) Kata'ib Hezbollah militia in Iraq's legalized PMF "could represent an obstacle that could undermine shared counterterrorism objectives."

Some Iran-aligned PMF forces participated in Iraqi operations in disputed territories following the September 2017 Kurdish referendum, and certain PMF figures such as Badr Organization leader Hadi al Amiri and Asa'ib Ahl al Haq leader Qais Khazali may intend to participate as political candidates in future elections. On October 31, Prime Minister Abadi emphasized that that the PMF law precludes registered PMF members from formally participating in politics, adding, "Anyone in the PMF should not exercise any political activity and if he wants to do so, he should leave the PMF."9 Observers continue to speculate about whether and how PMF figures may seek to leverage their profile and accomplishments for political gain in upcoming elections.

For background, see "Iran's Relationship with Iraq" below.

U.S. Foreign Aid and Security Assistance

Legislation under consideration in the first session of the 115th Congress would provide for the continuation of U.S. military operations, foreign assistance, training, and lending support to Iraq on current terms (H.R. 3354, H.R. 3362, and S. 1780). The conference report on the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA, H.R. 2810) would extend the authorization for the U.S. train and equip program in Iraq through December 2019 and would modify the mandate of the Office of Security Cooperation at the U.S. Embassy in Iraq (OSC-I) to widen the range of forces the office may engage to include all "military and other security forces of or associated with the Government of Iraq." The legislation would authorize the appropriation of $1.3 billion in FY2018 defense funding for continued train and equip efforts in Iraq, and the conference report would require a comprehensive report on conditions in Iraq and U.S. strategy.

In July 2017, the Trump Administration notified Congress of its intent to obligate up to $250 million in FY2017 Foreign Military Financing (FMF) funding for Iraq in part to support the costs of continued loan-funded purchases of U.S. defense equipment and to fund Iraqi defense institution building efforts. The Administration has requested $1.269 billion in defense funding to train Iraqis for FY2018. The Administration also has requested $347.86 million for foreign aid to Iraq in FY2018; including $300 million for post-IS stabilization. Since 2014, the United States has contributed more than $1.7 billion to humanitarian relief efforts in Iraq10 and more than $265 million to the United Nations Funding Facility for Stabilization (FFS)—the main conduit for post-IS stabilization assistance in liberated areas. The cost of military operations against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria as of June 30, 2017 was $14.3 billion, and, through FY2017, Congress had appropriated more than $3.6 billion for train and equip assistance in Iraq.

Political and Economic Profile

Iraq is a parliamentary republic, governed pursuant to a constitution adopted in a November 2005 referendum.11 Executive authority is exercised by the prime minister, while an indirectly elected president and three vice presidents carry out ceremonial and representative functions. Legislation originates with the prime minister or presidency. National legislative elections for Iraq's Council of Representatives (COR) were held in December 2005, March 2010, and April 2014. The 328-seat legislature is directly elected by proportional representation in multi-seat districts, with eight seats reserved for minority communities. Legislators vote to confirm nominees for the prime ministership, cabinet, and presidency. Elections for the next Council of Representatives are planned for May 2018.

Iraq's constitution provides for a sharing of some powers between the national government and recognized subnational entities known as regions. The Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) is the sole constitutionally recognized region at present, and is home to most of Iraq's ethnic Kurdish minority. Laws adopted since 2008 also have nominally provided for the decentralization of many administrative and judicial authorities to governorates that are not part of recognized regions.

Iraq's economy benefits from the country's considerable energy resources, its location at the center of the Middle East region, and its young, resilient population. Since the downfall of the Baathist regime and removal of international sanctions on Iraq, the country's GDP per capita has increased between six- and seven-fold.12 Nevertheless, during this period, conflict, instability, and corruption have taken a significant toll on Iraqis, and these factors continue to hinder otherwise promising development and investment trends. Because Iraq's government depends on oil proceeds for nearly 90% of its revenue, lower global oil prices and the fiscal demands of war with the Islamic State have greatly strained public finances since 2014. Iraq has sought and obtained international aid and lending to meet its fiscal needs, while also accumulating arrears.

Identity, Governance, and Politics

Iraq's society is diverse and includes a Shia Arab majority, large Sunni Arab and Kurdish communities, and several other ethnic and religious minority groups. Iraqis have struggled to achieve an inclusive political order since gaining independence in 1932.13 Different groups' attitudes toward the state have evolved over time, reflecting changes in power relationships, shifting security developments, and evolving priorities and identities. Today, rivalries between and within religious and ethnic communities, socioeconomic groups, geographic areas, and political movements abound.

Political change and conflict have swept the country since 2003, fueling anxieties about the future and contributing to sectarian political behavior and, at times, violence. In post-2003 Iraq, different groups have sought guarantees of autonomy, protection, or material benefits from the state, with confrontations being particularly pronounced at times between Sunnis and Shia and between Kurds and non-Kurds. Rivals have alternately accused each other of seeking to divide the country with foreign support or warned that the concentration of power may invite a return to centralized tyranny.

An elaborate, informal system has developed since 2003 to ensure the representation in government of various groups and political trends, but this has made divisive, identity-based politics durable. Leadership of key ministries has been determined according to identity and political orientation, with nominal communal representation in official positions serving as a weak guarantee of actual communal policy influence or benefits from the state. Extensive negotiations following national elections in 2005, 2010, and 2014 resulted in prime ministers drawn from Iraq's Shia Arab majority. By agreement, Iraq's presidency has been held by a member of the Kurdish minority, the speaker of the Council of Representatives has been a Sunni, and three vice presidencies have been held by representatives of the Shia Arab, Sunni Arab, and Kurdish communities.

Tensions and violence since 2003 have generated some calls for a nonsectarian political order, particularly since the collapse brought on by the Islamic State's advance in 2014. Proponents of merit-based rather than identity-based cabinet selections continue to face opposition from parties concerned about being left without representation in government or otherwise excluded. National reconciliation and reform proposals have been advanced by different factions, but Iraqis have struggled to overcome the gravity of zero sum competition. Observers of Iraqi politics are now monitoring debates over 2018 electoral legislation and the makeup of electoral authorities for indications of whether established patterns may prevail or a new chapter may be set to begin.

The Rise and Retreat of the Islamic State14

U.S. military forces completed their agreed withdrawal from Iraq in late 2011, after negotiations failed to produce a framework for authorizing a residual U.S. military presence.15 The Islamic State of Iraq (ISI, the precursor to the Islamic State organization—IS, aka ISIL/ISIS) and other insurgent groups had by then suffered considerable losses at the hands of U.S.-backed Iraqi forces. U.S. government assessments at the time judged that Iraqi forces were capable of independent internal security operations, but warned of some military capability gaps and the potential for a reversal in security gains.16 Prime Minister Nouri al Maliki, then in his second term in office, adopted a confrontational posture toward Sunni political rivals immediately following the completion of the U.S. withdrawal in December 2011, levelling terrorism and corruption allegations against prominent Sunni figures.

The remnants of the Islamic State of Iraq grew stronger throughout 2012 in an atmosphere of increasing political discontent among Iraq's Sunni Arabs and confrontation between them and the Maliki government. The prime minister's use of heavy-handed tactics against Sunni protestors contributed to a growing chasm of distrust, while in the background, long established patterns of mismanagement, graft, and exploitation of government institutions continued, undermining the improvement of government services and hollowing out security forces.

Capitalizing on Sunni disaffection and drawing resources and recruits from the escalating civil conflict in neighboring Syria, the Islamic State of Iraq rebranded itself as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria in April 2013 and stepped up its campaigns of violence in both countries. Governorate council elections were held amid escalating violence in mid-2013, as the U.N. Secretary-General reported "rising inter-sectarian tensions" were "posing a major threat to stability and security."17 Attacks against civilians increased rapidly, placing growing pressure on Iraqi leaders.

In late 2013, Prime Minister Maliki visited Washington to request additional military and intelligence support and pledged to take some conciliatory steps toward Iraqi Sunnis and implement security sector reforms. As Iraqis reached agreement on an election law, U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Iraq and Iran Brett McGurk warned in November 2013 testimony to Congress that the Islamic State was "trying to establish camps and staging areas in Iraq's western border regions" and that Iraq lacked the capabilities to effectively monitor and interdict IS activities. In January 2014, Islamic State forces swept into the Anbar governorate cities of Ramadi and Fallujah, remaining in the latter until their defeat there in mid-2016.

The 2014 Election, the Abadi Government, and Reform Debates

|

Results of 2014 Council of Representatives Election

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

National legislative elections were held on April 30, 2014, for 328 COR seats (expanded from 325). In provisional results announced in May 2014, Prime Minister Nouri al Maliki's State of Law coalition claimed the most seats, with coalitions associated with Shia cleric Muqtada al Sadr, other leading Sunni and Shia parties, and Kurdish parties also winning significant percentages of the seats. As the Islamic State seized Mosul and threatened Baghdad in June 2014, Shia Grand Ayatollah Ali al Sistani issued a fatwa calling for Iraqis to volunteer to defend the country, providing the basis for the creation of the Popular Mobilization Commission and its associated volunteer militia forces. U.S. and Iranian officials joined Sistani and other leading Iraqi Shia clerics in demanding the prompt formation of a government and helped convince Iraqi leaders to support the nomination of another State of Law coalition figure, the Dawa Party's Haider al Abadi, as an alternative candidate to Maliki (also of the Dawa Party).18 Some Iraqis criticize what they view as an overly conditional U.S. approach to Iraq during this period, especially perceived U.S. decisions to link offers of security support with calls for Prime Minister Maliki's replacement.

After being confirmed in mid-August 2014, Prime Minister Abadi moved quickly to nominate an inclusive cabinet and formally requested international military intervention to help halt and reverse the Islamic State's advance.19 President Obama had directed the deployment of additional U.S. military personnel to Iraq in June for personnel protection purposes, and U.S. air strikes against the Islamic State in Iraq began on August 8, as IS forces threatened the KRG capital at Erbil and besieged and overran Yezidi communities at Sinjar in northwestern Iraq.20

In late 2014 and early 2015, Prime Minister Abadi and other Iraqi leaders made progress on a number of reconciliation and security issues, but their achievements slowed in mid-2015 as blackouts fueled a wave of mass protests demanding improved electrical services and an end to corruption swept the capital and southern governorates. The prime minister, heeding a call from Grand Ayatollah Al Sistani, proposed a package of sweeping reforms in August 2015, ordering the elimination of several official posts, consolidation of ministries, reductions in spending and salaries, and inquiries into allegations of corruption. Prime Minister Abadi's proposal to eliminate Iraq's three vice presidencies generated controversy, since these positions were occupied by former prime ministers Nouri al Maliki and Ayad Allawi, along with former COR speaker Osama Nujaifi. Iraqi courts overturned the proposal, and the three figures remain in office.

The Obama Administration and the United Nations Secretary-General welcomed Abadi's 2015 moves, but the proposals and reform initiatives provoked backlash from vested political interests. Iraq's government was politically paralyzed from late 2015 through mid-2016 (see Timeline, below), as Abadi called for parties to put forward new cabinet nominees and non-affiliated reform activists demanded action in confrontational and disruptive mass protests. Alliances among Abadi's rivals, including former prime minister Maliki, failed to force Abadi and his parliamentary allies from power, but a wider, durable pro-reform coalition spanning identity-group boundaries failed to coalesce behind Abadi's most ambitious proposals.

|

Timeline: Crises, Confrontation, and Cooperation in Iraq, 2015-2017 August 2015 – Amid popular protests, Prime Minister Haider al Abadi proposes eliminating redundant officials, abolishing Iraq's three vice presidencies, and enacting other reforms. November 2015 – After opponents blunt Abadi's reform push, the Council of Representatives (COR) votes to require parliamentary approval for any government reorganization. February 2016 – Abadi relaunches his reform initiative. March 2016 – Abadi calls on political groups to nominate candidates for a new technocratic cabinet, announcing his own proposed slate on March 31. Some blocs reject Abadi's proposed candidates, and some nominees withdraw. April 2016 – In a series of tumultuous sessions, COR members clash over a revised cabinet list submitted by Abadi, trading recriminations and physical blows. COR members split into factions, with one claiming a quorum (164 members) and voting to unseat COR Speaker Salim Jabouri and another later voting to endorse five of Abadi's cabinet nominees. COR sessions are suspended for a lack of quorum, and protestors backed by Muqtada al Sadr force their way into the Green Zone on April 30. Several COR blocs announce they will boycott COR sessions until security is guaranteed, regular order reestablished, and Iraq's judiciary rules on the validity of the COR speaker's tenure and the April cabinet vote. May 2016 – Sadrist protestors return to the Green Zone, and clash with security forces. The Federal Supreme Court delays a hearing on the validity of the contested April COR sessions. Boycotts prevent the COR from reaching a quorum. June/July 2016 – The Federal Supreme Court rejects the COR claims, returning the parliament to a political status quo ante. Iraqi forces claim victory in Fallujah, but a deadly IS bombing in Karrada and other attacks kill hundreds in Baghdad and intensify demands for security improvements. Prime Minister Abadi accepts the Interior Minister's resignation. August 2016 - Muqtada al Sadr suspends protests for 30 days after reiterating his group's hostility to the United States. Defense Minister Khalid Al Obeidi levels corruption and extortion charges against several COR members, including Speaker Al Jabouri, during a COR questioning session that was itself focused on allegations of corruption in the defense ministry during Obeidi's tenure. The COR approves five of Prime Minister Abadi's cabinet nominees, rejecting a sixth. The COR votes to oust Defense Minister Obeidi. September 2016 – The COR votes to oust Finance Minister Hoshyar Zebari, as Prime Minister Abadi consults with U.S. and other officials regarding planned operations against the Islamic State in Mosul and Iraq's IMF agreement. October 2016 – The Federal Supreme Court rules against Prime Minister Abadi's August 2015 decision to abolish Iraq's three vice presidencies. Iraqi forces launch military operations to retake Mosul. November/December 2016 – The COR approves a law providing for the incorporation of the Popular Mobilization Forces as a permanent part of Iraq's national security establishment under the command of the prime minister. The law includes restrictions on the engagement of PMF personnel in politics. The COR adopts the 2017 budget, placing conditions on the sharing of revenue with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). January 2017 –The COR confirms the prime minister's nominees for Defense Minister and Interior Minister, ending months-long vacancies during critical security operations. |

Dynamics in 2017 and Preparations for 2018 Elections

Events in Iraq continue to be dominated by the effects of the war with the Islamic State, with establishment politicians advocating for their communities and regions while seeking to burnish their credentials as nationalists who support intercommunal reconciliation. Prime Minister Abadi has branded himself as a reformer and the commander in chief of the largely successful campaign against the Islamic State, even as entrenched interests continue to resist his reform initiatives and powerful rivals subtly challenge his authority. The future of the Popular Mobilization Forces and the Kurdistan Region of Iraq are perhaps the most important and politically sensitive issues at present, but discussion of post-IS stabilization, aid for the internally displaced, unemployment, services and utilities, and corruption also are prominent. Iraq's COR voted in August 2017 to again delay governorate elections, originally scheduled for May 2017, to be held at the same time as the May 2018 national elections. Debate has now shifted to consideration of the 2018 national elections law, which may limit action on other priorities. Iraq's Council of Representatives also is debating an electoral law for governorate/provincial council elections, including proposals for a seat-allocation formula that some smaller Iraqi parties and political reform advocates oppose.

Former prime minister and current Vice President Maliki remains politically active, and he continues to associate himself closely with Iran-backed PMF units, criticize Kurdish leaders in the wake of the advisory referendum on independence, and express anti-U.S. sentiment. Prime Minister Abadi and Vice President Maliki are both Dawa Party members, but Abadi appears to have greater appeal among non-Shia Arab Iraqis. Many Sunni and Shia Arab politicians, along with some minority community leaders, have expressed general opposition to the Kurdish referendum and express shared preferences for dialogue and the preservation of Iraqi sovereignty and territorial integrity. Some Iraqi Sunni and Shia leaders have expressed their support for the preservation of the Kurdistan Regional Government, presumably as a potential check on national authority and as a precedent for other potential federal regions. (See Figure 3 below.)

During the fight against the Islamic State, some PMF leaders have sought Prime Minister Abadi's permission to join the fight against the Islamic State in Syria and/or to participate more directly in raids against IS-held strongholds. Prime Minister Abadi's resistance to and deflection of these requests has been consistent with his oft-stated desire to see Iraq's traditional security forces lead disciplined anti-IS operations and his concerns about limiting human rights abuses and sectarian political behavior. A prominent PMF role in anti-IS operations also could bolster the popularity of certain PMF factions and contribute to the political appeal and influence of their leaders. Many leading figures in Iraq speak with respect and gratitude for PMF volunteers' contributions and sacrifices in the war against the Islamic State, reflecting the movement's generally positive image among Iraqis, amid concerns about some units' human rights violations and foreign ties.

|

Politics and Potential Coalitions

Iraqi political leaders and parties have begun consulting and repositioning in advance of the national elections. In July 2017, Ammar al Hakim, a prominent Shia Arab politician and cleric whose family had long led the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI), announced the establishment of a new political movement—known as the Hikmah (Wisdom) National Trend. In doing so, Hakim broke with other ISCI members over reported generational and personal differences. Also in July, some Sunni leaders announced plans to coordinate under a National Forces Alliance, but the election plans and preferences of leading Sunni parties remain in flux.

Some analysts of Iraqi politics have examined the potential for cooperation in the run-up to 2018 elections between Hakim, Prime Minister Abadi, the Wataniya (National) Coalition of Vice President Ayad Allawi, and the movement of Shia cleric Muqtada al Sadr. Sadr has publicly supported anti-corruption and service improvement initiatives in keeping with his populist political strategy.21 He also continues to speak in favor of full state control of all armed forces in the country and has called for changes to electoral legislation and management that could undermine the influence of larger parties. Vice President and former prime minister Nouri al Maliki could lead a potential rival coalition, to include PMF-associated figures. The participation and orientation of Kurdish parties in the election may become more consequential, particularly if one or more of the large parties boycotts or aligns with an emergent coalition.

The Kurdistan Region of Iraq

Northern Iraq is home to an estimated population of 5.6 million Kurds, the fourth largest ethno-linguistic group in the Middle East whose nearly 30 million members span the borders of Iraq, Syria, Turkey, and Iran (Figure 4). The settlement of World War I and subsequent Treaty of Sevres (1920) raised hopes of Kurdish independence, but under a later treaty (Treaty of Lausanne, 1923) Kurds were left with minority status in several countries. Kurds in Iraq fought as insurgents intermittently over decades to secure their communities and exercise self-determination, facing resistance from successive Iraqi governments and interference from Turkey and Iran. An autonomy arrangement between the Kurds and the Baathist government in the 1970s failed, and the 1980s were marked by the pressures of the Iran-Iraq war and Saddam Hussein's brutal campaign against Kurdish communities, which resulted in thousands of deaths and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of Iraqi Kurds.22

Kurdish self-government developed after the 1991 Gulf War under the protection of the no-fly zone that the United States and United Kingdom imposed over parts of northern Iraq. In 1992, Iraqi Kurds established a joint administration between Iraqi Kurdistan's two main political movements—the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK)—in areas under their control. The Kurds then held elections for a parliament, which in turn called for "the creation of a Federated State of Kurdistan in the liberated part of the country." A subsequent breakdown in KDP-PUK power-sharing arrangements led to discord and armed conflict between 1994 and 1998. Kurdish factions resumed cooperation in the run up to the 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, and the post-Saddam Transitional Administrative Law and 2005 Constitution formally recognized the authority of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in areas that were under Kurdish control as of March 19, 2003.

|

|

Source: Gene Thorp/Washington Post, citing the Central Intelligence Agency; Council on Foreign Relations; adapted by CRS. |

Kurdish leaders participated in the post-2003 Iraqi Governing Council, the Interim Iraqi Government, and the Transitional National Assembly, working to ensure that emerging constitutional arrangements would allow Kurds to retain autonomy and formally recognize Kurdish political and security institutions. Elections for the Kurdistan National Assembly (KNA) were held in January 2005, July 2009, and September 2013. The KNA approved a draft constitution for the KRI in 2009, but the draft has not been put forward for approval by popular referendum because of the objections of national authorities and political disputes among Kurdish parties.

The KNA indirectly selected KDP leader Masoud Barzani as KRG President in June 2005. He was directly elected in July 2009, and the KNA approved a law extending his term for two years in August 2013. Barzani refused Kurdish opposition demands that he step down following the expiration of his extended term, and the KNA did not meet from October 2015 until September 2017. Overdue parliamentary and presidential elections for the Kurdistan region were proposed for November 2017, but were delayed for eight months in the wake of the September 2017 referendum on independence and subsequent Kurdish losses in Iraq's disputed territories. Elections in the KRG could be further derailed if relationships between and within leading Kurdish political movements breaks down further or if developments in the confrontation with Baghdad create new obstacles.

Kurdish Politics

Kurdish political movements in Iraq have alternated between collaboration and competition, at times presenting a unified front in the face of outside pressure and at times partnering with non-Kurds and non-Iraqis in pursuit of discrete agendas. The KDP is led by members of the Barzani family and has historically drawn its support from Erbil and Dohuk governorates.23 KRG Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani is the son of the late brother of KRG President Masoud Barzani. Masoud Barzani's son Masrour serves as Chancellor of the KRG National Security Council and director of the KRG intelligence services. The PUK has long been associated with the Talabani family and has historically drawn its support from Suleimaniyah governorate.24 The death of former Iraqi President and PUK founder Jalal Talabani has opened the question of leadership in the PUK, with Talabani's widow Hero Ibrahim Ahmed, sons, and nephews occupying important roles, and other PUK figures influencing the movement's direction.

KDP-PUK rivalries over time have been based on personal leadership, control over resources and revenue, and whether or how the Kurds should accommodate non-Kurds in Baghdad. Over time, the two factions have developed and maintained party-aligned militia forces (the KDP's 80s force of ~60,000 and the PUK's 70s force of ~ 48,000), which supplement forces under the KRG's Ministry of Peshmerga (~42,000 personnel).25 The KDP and PUK also exercise influence over police and intelligence forces in their respective strongholds.

The Gorran (Change) movement emerged from the PUK in 2009 and has challenged both parties with its vocal anti-corruption and political reform advocacy. Gorran selected new leaders following the May 2017 death of its founder, Nawshirwan Mustafa. Gorran advocated for reopening the region's parliament prior to holding the advisory referendum on Kurdish independence. Also in 2017, former KRG Prime Minister Barham Salih left the PUK to form his own political movement, known as the Coalition for Democracy and Justice (CDJ). The CDJ has called for a transitional administration for the KRG amid escalating post-referendum tensions with Baghdad. In addition, smaller Kurdish Islamist movements hold seats in the KNA and in the national COR. In the 2013 KNA elections, the KDP won 38 seats, the Gorran Movement won 24 seats, the PUK won 18 seats, the Kurdistan Islamic Union won 10 seats, and the Kurdistan Islamic Group won 6 seats. The KNA reserves 11 seats for religious and ethnic minorities.

Since 2013, the KDP's insistence on its priorities and an on-again-off-again PUK-Gorran alliance have complicated Kurdish efforts to speak with a single voice in negotiations with Baghdad on a range of outstanding issues. As noted above, the KNA did not meet from October 2015 to September 2017 because of interparty disputes over the expiration of President Barzani's extended term in office, alleged mismanagement of public finances, and differences over the proper approach to take toward relations with Baghdad. KRG-Baghdad relations benefitted from positive coordination on security operations against the Islamic State, especially in Mosul. Nevertheless, they have been strained and uncertain in the aftermath of the referendum and October 2017 clashes in disputed territories.

Uncertainty and Confrontation in Iraq's Disputed Territories

Kurds and non-Kurds in Iraq have long disputed territory and resources located along a northwest-to-southeast zone that spans the country diagonally from the borders with Syria and Turkey to the border with Iran (Figure 5). Areas south of this zone are predominantly populated by ethnic Arabs, and areas to the north are predominantly populated by ethnic Kurds, with populations intermixed in some areas, including populations of religious and ethnic minorities such as Christians and Turkmen. Prior to 2003, recurrent periods of insurgency by Kurds in northern Iraq resulted in inconclusive agreements on partial autonomy for Kurdish areas with no durable agreement over or demarcation of respective areas of administrative control. The pre-2003 Baathist government rearranged administrative boundaries and used violence to reengineer the population of some disputed territories, at great cost to Iraq's Kurds.

Today, the city of Kirkuk and the wider, oil-rich Kirkuk Governorate are the most prominent and strategically significant of Iraq's 'disputed territories,' which also include large areas of Ninewa Governorate and areas in Erbil and Diyala Governorates. The history of struggle over these territories, the location in some disputed areas of oil and other natural resources, and the presence and demands of resident ethnic minorities such as Turkmen and religious minorities, including Shia Muslims, Yazidis, and Christians, have produced complex webs of competing claims. In many areas, these claims remain unresolved and volatile.

Under post-2003 Iraqi law, the de jure boundaries of the constitutionally recognized Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) have not been finalized. As of June 2004, Article 53(A) of Iraq's Transitional Administrative Law (TAL) recognized the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) "as the official government of the territories that were administered by that government on 19 March 2003 in the governorates of Dohuk, Arbil, Sulaimaniya, Kirkuk, Diyala and Neneveh." These territories were defined in part by the de facto "forward line of control" that Saddam Hussein's security forces had maintained along a northwest-southeast line across northern Iraq as of March 2003. This line, though not precisely defined in law, is often referred to as 'the Green Line.' Article 117 of the 2005 Iraqi constitution recognized "the region of Kurdistan, along with its existing authorities, as a federal region." Article 143 preserved the TAL definition of the KRG.

From the perspective of most Kurds, the interim de jure demarcation at the 2003 Green Line failed to properly return to Kurdish administrative control some territories that historically had been populated by Kurds, including areas south of the Green Line that were subject to the pre-2003 government's forced displacement campaigns and 'Arabization' policies. The de facto presence after 2003 of Kurdish forces in areas south of the Green Line became a source of friction among Iraqis, with some Iraqi Arabs and Turkmen questioning the legitimacy of the Kurdish presence and all sides fearing their counterparts might impose a unilateral solution.

The constitution defined a framework for the resolution of claims and questions regarding disputed territories, calling in Article 140 for "normalization," a census, and a referendum in Kirkuk and other territories on or before December 31, 2007. This deadline was not met, subsequent attempts to implement Article 140 failed, and negotiations failed to identify a viable alternative. Kurdish leaders planned, but then deferred, a constitutional referendum in July 2009 that would have asserted that several disputed territories, including Kirkuk, were part of the Kurdistan region. The United Nations Assistance Mission in Iraq (UNAMI) made significant efforts to prepare for and advance dialogue on the disputed territories, but Iraqi discussions remained open-ended. U.S. and coalition military initiatives created de-confliction mechanisms to prevent security incidents in disputed areas but these were phased out with the U.S. withdrawal.

In 2013, Kurdish authorities announced plans to move forward with the construction of new oil pipeline infrastructure that would allow the KRG to export larger quantities of oil from some fields within the KRI and disputed territories without the use of Baghdad-controlled infrastructure. By January 2014, this infrastructure was complete, and Kurdish oil exports via pipeline to Turkey grew in volume. In response, authorities in Baghdad announced they would withhold funds allocated for the KRG in the national budget, precipitating a deepening standoff.

The rapid advance of the Islamic State's forces across northwest Iraq in early 2014 soon overshadowed this dispute. Iraqi security forces withdrew southward from many of the disputed territories, and Kurdish peshmerga forces advanced, citing the need to establish a defensive perimeter for the rest of the KRI. This dynamic significantly altered prevailing de facto patterns of territorial control, placing several long-disputed territories and oil-rich areas under Kurdish control. This shift had the effect of altering expectations among some Kurds and foreign expectations about how eventual negotiations between Baghdad and the KRG regarding a de jure settlement of claims might proceed.

From 2014 through mid-2017, Kurdish and Iraqi officials continued to treat the final status of disputed territories as formally undecided, and most leaders expressed preferences for a negotiated settlement of territorial claims. Some Kurdish figures made statements implying that KRG forces would not relinquish areas gained after 2014, while some non-Kurdish Iraqis demanded that the national government take action to reverse post-2014 changes. The June 2017 announcement by Kurdish leaders of their decision to hold a referendum on independence including in disputed territories concentrated the attention of Iraqis and outsiders on related questions. Kurdish leaders explained their decision to pursue the referendum in part as a response to what they described as the failure to implement Article 140 and other elements of the constitution they view as granting the KRG authority it has been denied.

U.S. and U.N. officials engaged with Kurdish officials to emphasize their opposition to the timing of the referendum and the idea of holding it in disputed territories, and ultimately called for the referendum to be cancelled. As noted above, the referendum was held on September 25, and, in its wake, Iraqi national government officials moved to reassert national government authority over the border crossings and air space of the KRI.

In October 2017, the Iraqi government moved to reassert security control in areas of the disputed territories that had been held by national forces prior to the Islamic State's advance. Rapid changes in territorial control followed, and important oil fields and infrastructure that had been under Kurdish control from 2014 through September 2017 have been retaken by national government forces. The area near the Syria-Iraq-Turkey tri-border at Faysh Khabour has emerged as an area of particular attention and concern, especially because Kurdish oil export pipeline infrastructure transits the area.

U.S. officials continue to encourage Kurds and other Iraqis to engage on outstanding issues of dispute and to avoid unilateral military actions that could further destabilize the situation. U.S. official statements on the disputed territories and recent developments have emphasized that recent changes in territorial control do not alter the U.S. position on the underlying status of the disputed territories: namely, that they remain disputed as a de jure matter and that their status and security and administrative arrangements within them should be determined through consultation pursuant to the Iraqi constitution. Past U.N., Iraqi, and Kurdish efforts to document and investigate territorial claims provide a detailed factual basis for such consultation and dialogue.

Energy Resources

Iraq's ample reserves of oil and natural gas have produced significant wealth for the country but remain subject to ongoing political competition and dispute. According to the Oil and Gas Journal, Iraq has 143 billion barrels of proven oil reserves, the world's fifth-largest and 9% of overall global proved reserves.26 The uneven geographic distribution of Iraq's energy resources increases their political sensitivity. Proven oil reserves are concentrated largely (65% or more) in southern Iraq, particularly in the southernmost governorate of Basra, with other large fields located in northeastern Iraq near the disputed city of Kirkuk (Figure 6). Since 2003, KRG-Baghdad oil disputes have remained closely tied to questions about the political future of KRG-administered areas and control of disputed territories, including oil-rich areas of Kirkuk province that were occupied by KRG forces since 2014 and that have now been largely retaken by national forces. Kurdish efforts to independently develop and export oil resources in areas under KRG control have been pursued in accordance with the KRG's reading of the Iraqi constitution, but have been rejected by successive administrations in Baghdad. Meanwhile, predominantly Arab-populated provinces in Iraq's oil-rich south have sought guarantees that the export of locally produced oil will result in dedicated local funding, and oil-poor areas elsewhere have sought assurances that their needs will be met by shared revenues.

|

Figure 6. Location of Iraq's Oil Reserves and Infrastructure |

|

|

Source: Adapted by CRS from U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), Iraq Energy Situation Analysis Report, June 26, 2003. |

Fiscal Challenges and Economic Conditions

The fiscal crises that are straining the public finances of the national government and the KRG amplify the pressure on leaders working to address the country's security and political challenges. On a national basis, the combined effects of lower global oil prices, expansive public sector liabilities, and the costs of the military campaign against the Islamic State have created budget deficits—estimated at 12% of GDP in 2015 and 14% of GDP in 2016. 27 The IMF estimates Iraq's 2017-2018 financing needs at 19% of GDP. Oil exports continue to provide nearly 90% of public sector revenue in Iraq, while non-oil sector growth has been hindered over time by insecurity, weak service delivery, and corruption. Iraq's oil production and exports increased in 2016, but fluctuations in oil prices undermined revenue gains, and Iraq has since agreed to manage its overall oil production in line with mutually agreed OPEC output limits. In July 2017, Iraq exported an average of 3.2 million barrels per day (mbd, excluding Kurdish exports) at an average price of $43.80 per barrel, below the amended July 2017 budget's assumed oil export price of $45.3 per barrel and 3.75 mbd export assumption.28 The IMF projects modest GDP growth over the next five years and expects growth to be stronger in the non-oil sector if Iraq's implementation of agreed measures continues as oil output and exports plateau.

IMF Stand-by Arrangement

To date, the national government has financed budget gaps through a mix of spending cuts, other austerity measures, currency reserve drawdowns, accumulation of arrears, and domestic and international borrowing. In July 2016, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) approved a $5.34 billion Standby Arrangement for Iraq, following $1.24 billion in Rapid Financing Instrument assistance provided in 2015 to meet pressing government needs.29 The IMF arrangement reflects Iraqi commitments to maintain support for internally displaced persons and other public support recipients and includes policy commitments to further reduce public sector outlays, even after substantial salary cuts and price hikes drew protests from Iraqis in 2015. The IMF arrangement was intended in part to boost the confidence of donor governments and private lenders who had remained relatively reluctant to extend financing to Iraq on affordable terms. It has helped Iraq attract additional foreign financing as planned, supplemented by U.S. loan guarantees and technical assistance. In January 2017, Iraq offered a $1 billion, U.S.-guaranteed five-year sovereign bond and raised an additional $1 billion in a July 2017 independent bond offering.30

In August 2017, the IMF described Iraqi performance under the arrangement as "weak in some key areas" but noted that "understandings have been reached on sufficient corrective actions to keep the program on track" and argued that "resolute implementation of the authorities' program, together with strong international support, will be key."31 The COR adopted an amendment to the 2017 budget in July, lowering spending further and making other changes requested by the IMF. The most recent IMF review emphasized the need for further fiscal belt tightening, growth in non-oil revenues, reform of the electricity sector, and improvements in public sector financial management. According to the review, Iraqi authorities

agreed that the oil price outlook left no other choice but to contain spending to maintain fiscal and external sustainability. The adjustment process will need to be designed and implemented in a way that considers the spending pressures flowing from the war against ISIS, the internally displaced population, the vast investment needs of the country, and the parliamentary elections in 2018.32

Fiscal Issues in the Kurdistan Region

The Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) has faced economic and fiscal pressure in recent years, in spite of its reputation as a relatively attractive market and destination for investment in Iraq. In early 2014, then-Prime Minister Maliki responded to the KRG's decision to produce and export ~500,000 barrels per day of oil without Baghdad's approval by withholding the Kurdistan Regional Government's (KRG) share of the Iraqi national budget. Officials from the KRG and national government reached revenue sharing and production agreements in 2015 and 2016, but disputes over exports, the September 2017 referendum, and security have stalled their implementation. Oil produced in areas under Kurdish control, including in disputed territories, transits pipelines northwestward through Turkey and eastward via truck to Iran. Iraqi government efforts to assert control over border crossing points between the Kurdistan region in the wake of the referendum directly affect the KRI's potential for economic independence, particularly in far northwestern Iraq, where important road and pipeline infrastructure crosses into Turkey.

Budget withholdings by Baghdad since 2014 have contributed to a fiscal and economic crisis in the KRI. Public sector salaries essential to a majority of the working-age Kurdish population have been delayed for months at a time; the KRG has been unable to meet higher salary and supply costs associated with the war against the Islamic State. Billions in unpaid salaries and other public sector obligations have accrued as arrears. The fiscal crisis has contributed to intra-Kurdish political tensions, with factions splitting over the national parliament's adoption of the 2017 budget law.33 The confrontation between Baghdad and the KRG over disputed territories and border control in October and November 2017 has widened the gap between the parties on fiscal issues. Prime Minister Abadi has offered to pay the salaries of KRG public sector employees while questioning the validity of the civil service lists submitted by KRG authorities. As in the rest of Iraq, the presence of so-called "ghost employees" on KRG civil service lists has long been reported.

U.S. assistance to the Kurds has helped bridge the region's fiscal gap, but prospects for further U.S. budget support may be shaped by the status of Baghdad-KRG consultations and confrontations. In July 2016, the United States and the KRG signed an agreement (with Baghdad's approval) governing the provision of more than $480 million in U.S. financial and material assistance specifically to support the peshmerga. A follow-on agreement for the renewal of the stipend arrangement has been delayed in light of Baghdad-KRG differences over the September 2017 referendum and the control of disputed territories.

Humanitarian Conditions

Since August 2014, the United Nations has designated the situation in Iraq as a Level Three emergency, its designation for "the most severe, large-scale humanitarian crises." Conflict and terrorist violence in Iraq have created long-running displacement crises, with the International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimating that 11 million Iraqis were in need of some form of humanitarian assistance as of October 2017.34 More than 5.4 million Iraqis have been displaced since 2014, and 2.1 million have returned to their home districts.35 Displacement in Iraq was concentrated in northern areas for most of 2017, amid Iraqi and coalition military operations against the Islamic State in and around the city of Mosul and elsewhere in Ninewa, Salah al-Din, and Kirkuk Governorates. Of the more than 1 million people estimated to have been displaced after the start of operations in Mosul in October 2016, approximately 72% remained displaced in mid-October 2017.36

During his March 2017 visit to Washington, DC, Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al Abadi reviewed progress in Iraq's campaign against the Islamic State and appealed for U.S. and international aid to help meet Iraq's short term humanitarian needs and longer term stabilization and reconstruction costs. The multilateral 2017 Humanitarian Response Plan appeal for Iraq sought $984.6 million, of which $717 million or 72.8% had been received as of November 16, 2017.37 According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), the "full cost of the aggregate humanitarian needs of 11 million Iraqis is estimated at well over U.S. $3 billion."38

Iraqi authorities and international organizations are working to assist civilians across the country, including non-Iraqi refugees and the families and communities that host and have hosted IDPs and refugees during years of conflict. This includes more than 244,000 registered Syrian refugees in Iraq, more than 95% of whom are located in the KRI. The appeal for the Iraq component of the 2017-2018 Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan (3RP) in response to the Syria crisis requested $228.1 million, of which $122.3 million (53.6%) had been received as of November 16, 2017.39

Interrelated security, political, economic, social, and health challenges complicate assistance efforts and the viability of civilians' attempts to return home. In northern Iraq, several persistent obstacles to the return and reintegration of Iraqi IDPs include ongoing conflict, a lack of security and services in cleared areas, endemic levels of unexploded ordnance, fear of reprisal, and destruction of private property and public infrastructure. Among returning individuals and their neighbors, localized tensions may flare regarding property disputes and damage, politics, economic opportunities, and accountability for alleged crimes. National politics also may intrude, with some local communities finding themselves on the front lines of broader national and international disputes over territory, resources, and security.

Families of confirmed or suspected Islamic State members also face unique challenges, as Iraqi authorities seek to isolate potential security threats and family members face scrutiny, hostility, extrajudicial violence, and/or expulsion from their homes. Human rights organizations have expressed concern about the isolation of confirmed or suspected IS family members in "rehabilitation camps," and United Nations officials have warned that individuals indirectly associated or accused of affiliation with the Islamic State may be targeted in revenge attacks.

Conditions in the Kurdistan Region

According to the IOM, as of October 31, 2017, more than 925,000 IDPs were present in Dohuk, Erbil, and Suleimaniyah Governorates, the principal territories of the KRI. 40 This includes more than 184,000 persons displaced after disputed territories changed hands between KRG and national forces in October 2017. More than 263,000 additional IDPs are present in Kirkuk Governorate, which is jointly administered by Kurdish and national forces. KRG officials estimate that the annual cost of hosting IDPs and refugees is approximately $1.4 billion per year, inclusive of costs to KRG infrastructure. IOM reporting in 2017 has suggested that IDPs present in the KRI are generally positive about security and social conditions but face economic strains, limited services, unemployment, and language barriers in some areas. The United States provides humanitarian assistance for programs in the KRI, with approximately $175 million in FY2016 funding having been directed for KRI-based humanitarian responses and comparable FY2017 funding planned.

Conditions for Minority Groups

Members of religious and ethnic minority groups, including various Iraqi Christian communities and Yezidis, face added difficulties because their communities have been violently targeted by the Islamic State since 2014 and because they lack the resources and capacity for protection that have allowed some other groups to return home. In March 2017, the IOM reported that "while Arab Sunni and Arab Shia Muslims, Kurdish Sunni and Turkmen Sunni Muslims have significantly returned home, Shabak Shia Muslims, Kurdish Yazidis, Chaldean Christians and other minorities remain displaced across Iraq."41

Minorities who previously had fled from violence elsewhere in the country to northern Iraq, including to Ninewa Governorate and the Ninewa Plain region, in some cases have suffered multiple displacements as a result of the Islamic State conflict.42 While Iraq's national leaders have insisted that security forces prioritize civilian protection and adopt a non-sectarian approach, reports suggest that some civilians, including some minority group members, have suffered at times from instances of sectarian intimidation and/or violence at the hands of local or extra-local forces, including militias.43 The concentration of many minority communities in areas subject to territorial and security disputes adds to their vulnerability to violence and political intimidation. The relative movements of national and KRG forces in disputed territories since October 2017 have heightened the concerns of some communities, and renewed clashes between national and KRG forces could lead to deteriorating security for minority communities in some areas.

After the Islamic State: Security and Stabilization

With major combat operations against the Islamic State reaching their conclusion in Iraq, officials and observers are directing greater attention toward questions of security and stability in areas retaken from the group. Concerns for the immediate future focus on defending against an expected terrorism and low level insurgent campaign by the Islamic State's surviving supporters to demonstrate their persistence. In the context of these concerns, Iraqi officials and foreign donors are supporting a range of stabilization programs designed to help communities reestablish damaged infrastructure, protect public health, provide economic opportunities, and overcome disputes that emerged or were exacerbated by the rise of the Islamic State. More broadly, the State Department continues to warn of significant terrorism and crime risks throughout Iraq and identifies Iran-backed militias as a threat to U.S. personnel and interests.