Israel: Major Issues and U.S. Relations

Changes from September 10, 2019 to September 18, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Israel: Background and U.S. Relations in Brief

Contents

- Introduction: Major Issues for U.S.-Israel Relations

- How Israel Addresses Threats

- Military Superiority and Homeland Security Measures

- Undeclared Nuclear Weapons Capability

- U.S. Cooperation

- Iran and the Region

- Iranian Nuclear Agreement, U.S. Withdrawal and Sanctions, and 2019 Gulf Tensions

- Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon

- Hezbollah

- Syria and Iraq: Reported Israeli Airstrikes Against Iran-Backed Forces

- Golan Heights

- Israeli-Palestinian Issues Under the Trump Administration

- Domestic Issues

and: September2019 Elections17 Elections and Prospects for a New Government

Summary

The following matters are of particular significance to U.S.-Israel relations:

Israel's ability to address threats. Israel relies on a number of strengths—including regional conventional military superiority—to manage potential threats to its security, including evolving asymmetric threats such as rockets and missiles, cross-border tunneling, drones, and cyberattacks. Additionally, Israel has an undeclared but presumed nuclear weapons capability. Against a backdrop of strong bilateral cooperation, Israel's leaders and supporters routinely make the case that Israel's security and the broader stability of the region remain critically important for U.S. interests. A 10-year bilateral military aid memorandum of understanding (MOU)—signed in 2016—commits the United States to provide Israel $3.3 billion in Foreign Military Financing annually from FY2019 to FY2028, along with additional amounts from Defense Department accounts for missile defense. All of these amounts remain subject to congressional appropriations. Some Members of Congress criticize various Israeli actions and U.S. policies regarding Israel. In recent months, U.S. officials have expressed some security-related concerns about China-Israel commercial activity.

Iran and the region. Israeli officials seek to counter Iranian regional influence and prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons. In April 2018, Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu presented historical information about Iran's nuclear program that Israeli intelligence apparently seized from an Iranian archive. The presentation came days before President Trump announced the U.S. withdrawal from the 2015 international agreement that constrained Iran's nuclear activities. Israel has reportedly conducted a number of military operations in Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon against Iran and its allies due to concerns about Iran's efforts to establish a permanent presence in these areas and improve the accuracy and effectiveness of Hezbollah's missile arsenal. Israel-Iran tensions increased somewhat during summer 2019 amid international concerns over the security of Persian Gulf energy commerce and questions about possible U.S.-Iran conflict or negotiation. In the context of ongoing uncertainty in Syria, in March 2019 President Trump recognized Israel's claim to sovereignty over the Golan Heights, changing long-standing U.S. policy that held—in line with U.N. Security Council Resolution 497 from 1981—the Golan was occupied Syrian territory whose final status was subject to Israel-Syria negotiation.

Israeli-Palestinian issues. The prospects for an Israeli-Palestinian peace process are complicated by many factors. Palestinian leaders cut off high-level political contacts with the Trump Administration after it recognized Jerusalem as Israel's capital in December 2017. U.S.-Palestinian tensions have since worsened amid U.S. cutoffs of funding to the Palestinians and diplomatic moves—including the May 2018 opening of the U.S. embassy to Israel in Jerusalem. The Administration claims it has prepared a plan that proposes specific solutions on the core issues of the conflict, but has repeatedly postponed the release of the plan. Palestinian leaders are wary of possible U.S. attempts to pressure them by economic means into difficult political concessions. While Israel may count on warming ties with Arab Gulf states over Iran to carry over into Israeli-Palestinian diplomacy, these states' leaders maintain explicit support for a Palestinian state with a capital in Jerusalem. In August 2019, Israel and the Palestinian Authority (PA) took initial measures aimed at relieving a PA fiscal crisis surrounding the transfer of revenues that Israel collects on the PA's behalf. Netanyahu hasBefore the September 17, 2019, elections, Netanyahu pledged to annex parts of the West Bank if he iswas reelected as prime minister.

Domestic issues: government formation after elections. Following the September 17 elections, the outcome of what could be a weeks-long government formation process looks unclear. Israeli President Reuven Rivlin will probably assign either Prime Minister Netanyahu from the Likud party or Benny Gantz from the Kahol Lavan party to form a government. Some observers assert that a "unity government" might be more likely than other outcomes, perhaps reducing Netanyahu's ability to pursue initiatives mooted during the campaign. Avigdor Lieberman from the Yisrael Beitenu party could exercise significant influence on the process. Meanwhile, a pre-indictment hearing on corruption charges against Netanyahu is scheduled to take place on October 2 reelected as prime minister.

Domestic issues. Israel will hold another round of Knesset elections on September 17, 2019, after Netanyahu was unable to form a government following April 2019 elections and the Knesset dissolved itself. A new government (if it is so inclined) may face time constraints to passing legislation that could protect Netanyahu from indictment on three pending corruption charges. Netanyahu's pre-indictment hearing is scheduled to take place in early October. Observers speculate about who among Netanyahu and his rivals—such as Kahol Lavan (Blue and White) party leader Benny Gantz—might form and lead a government after the elections.

Introduction: Major Issues for U.S.-Israel Relations

Strong relations between the United States and Israel have led to bilateral cooperation in many areas. Matters of particular significance include the following:

- Israel's own capabilities for addressing threats, and its cooperation with the United States.

- Shared U.S.-Israel concerns about Iran's nuclear program and regional influence, including with Iran's Lebanon-based ally Hezbollah. Israel has reportedly engaged in airstrikes against Iranian or Iran-allied targets in Syria and Iraq.

- Israeli-Palestinian issues and U.S. policy, including the Trump Administration's actions on political and economic matters to date.

- Israeli domestic political issues, including

upcoming elections in September 2019, in the context of probable corruption-related indictments against Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu. Netanyahu was unable to form a government in May after elections held in April.

the uncertainty surrounding efforts to form a government following elections held on September 17, 2019. The process may extend into November, or another round of elections could occur if neither Kahol Lavan leader Benny Gantz nor Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu succeeds in attracting majority support from the Knesset (Israel's parliament). For background information and analysis on these and other topics, including aid, arms sales, and missile defense cooperation, see CRS Report RL33476, Israel: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti; and CRS Report RL33222, U.S. Foreign Aid to Israel, by Jeremy M. Sharp.

How Israel Addresses Threats

Israel relies on a number of strengths to manage potential threats to its security and existence. These strengths include robust military and homeland security capabilities, as well as close cooperation with the United States.

Military Superiority and Homeland Security Measures

Israel maintains conventional military superiority relative to its neighbors and the Palestinians. Shifts in regional order and evolving asymmetric threats during this decade have led Israel to update its efforts to project military strength, deter attack, and defend its population and borders. Israel appears to have reduced some unconventional threats via missile defense systems, reported cyber defense and warfare capabilities, and other heightened security measures.

Israel has a robust homeland security system featuring sophisticated early warning practices and thoroughthorough border and airport security controls; most of the country's buildings have reinforced rooms or shelters engineered to withstand explosions. Israel also has proposed and partially constructed a national border fence network of steel barricades (accompanied at various points by watchtowers, patrol roads, intelligence centers, and military brigades) designed to minimize militant infiltration, illegal immigration, and smuggling from Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and the Gaza Strip.1 Additionally, Israeli authorities have built a separation barrier in and around parts of the West Bank.2

|

|

Sources: Graphic created by CRS. Map boundaries and information generated by Hannah Fischer using Department of State Boundaries (2011); Esri (2013); the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency GeoNames Database (2015); DeLorme (2014). Fact information from CIA, The World Factbook; Economist Intelligence Unit; IMF World Outlook Database; Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. All numbers are estimates as of 2018 unless specified. Notes: According to the U.S. executive branch: (1) The West Bank is Israeli occupied with current status subject to the 1995 Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement; permanent status to be determined through further negotiation. (2) The status of the Gaza Strip is a final status issue to be resolved through negotiations. (3) The United States recognized Jerusalem as Israel's capital in 2017 without taking a position on the specific boundaries of Israeli sovereignty. (4) Boundary representation is not necessarily authoritative. Additionally, the United States recognized the Golan Heights as part of Israel in 2019; however, U.N. Security Council Resolution 497, adopted on December 17, 1981, held that the area of the Golan Heights controlled by Israel's military is occupied territory belonging to Syria. The current U.S. executive branch map of Israel is available at https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/attachments/maps/IS-map.gif. |

Undeclared Nuclear Weapons Capability

Israel is not a party to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) and maintains a policy of "nuclear opacity" or amimut. A 2017 report estimated that Israel possesses a nuclear arsenal of around 80-85 warheads.3 The United States has countenanced Israel's nuclear ambiguity since

|

China-Israel Commercial Activity and Its Impact on U.S.-Israel Relations U.S. officials have raised some concerns with Israel over Chinese investments in Israeli high-tech companies and civilian infrastructure that could increase China's ability to gather intelligence and acquire security-related technologies.4 These concerns apparently focus on potential threats from China to U.S. national security in various fields, such as cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, and robotics.5 Some Israeli officials reportedly have voiced worries about Chinese investment in Israel as well.6 Previously, China-Israel defense industry cooperation in the 1990s and 2000s contributed to tension in the U.S.-Israel defense relationship and to an apparent de facto U.S. veto over Israeli arms sales to China.7 In passing the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (S. 1790), the Senate expressed its sense (in Section 1289) that the U.S. government should "urge the Government of Israel to consider the security implications of foreign investment in Israel." President Trump reportedly warned Prime Minister Netanyahu in March 2019 that U.S. security assistance for and cooperation with Israel could be limited if Chinese companies Huawei and ZTE establish a 5G communications network in Israel, in line with similar warnings that the Administration has communicated to other U.S. allies and partners.8 Additionally, the U.S. Navy is reportedly reconsidering its practice of periodically docking at the Israeli naval base in Haifa, because a state-owned Chinese company (the Shanghai International Port Group) has secured the contract to operate a new terminal at Haifa's seaport for 25 years (beginning in 2021).9 Other state-owned Chinese companies are developing a new port in Ashdod (which also hosts an Israeli naval base),10 and bidding to take part in construction for Tel Aviv's light rail system.11 |

1969, when Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir and U.S. President Richard Nixon reportedly reached an accord whereby both sides agreed never to acknowledge Israel's nuclear arsenal in public.12 Israel might have nuclear weapons deployable via aircraft, submarine, and ground-based missiles.13 No other Middle Eastern country is generally thought to possess nuclear weapons.

U.S. Cooperation

Israeli officials closely consult with U.S. counterparts in an effort to influence U.S. decision-making on key regional issues, and U.S. law requires the executive branch to take certain actions to preserve Israel's "qualitative military edge," or QME.14 Additionally, a 10-year bilateral military aid memorandum of understanding (MOU)—signed in 2016—commits the United States to provide Israel $3.3 billion in Foreign Military Financing and to spend $500 million annually on joint missile defense programs from FY2019 to FY2028, subject to congressional appropriations.

Israel's leaders and supporters routinely make the case that Israel's security and the broader stability of the region remain critically important for U.S. interests. They also argue that Israel is a valuable U.S. ally.15 The United States and Israel do not have a mutual defense treaty or agreement that provides formal U.S. security guarantees.16

Although domestic U.S. support for Israel and its security has been strong for decades, and remains robust, some Members of Congress have criticized various Israeli actions and U.S. policies regarding Israel. In August 2019, Israel denied entry to Representatives Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar, citing an Israeli law that permits authorities to bar supporters of the boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) movement from visiting Israel.1718 This action, among other things, has contributed to speculation that U.S. policy on Israel could become a more contentious domestic issue.1819

Iran and the Region

Israeli officials cite Iran as a primary concern to Israeli officials, largely because of (1) antipathy toward Israel expressed by Iran's revolutionary regime, (2) Iran's broad regional influence (especially in Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon),1920 and (3) the recent and possible future loosening of some constraints on Iran's nuclear program. Israel and Arab Gulf states have discreetly cultivated closer relations with one another during this decade in efforts to counter Iran.

Iranian Nuclear Agreement, U.S. Withdrawal and Sanctions, and 2019 Gulf Tensions

Prime Minister Netanyahu has sought to influence U.S. decisions on the international agreement on Iran's nuclear program (known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA). He argued against the JCPOA when it was negotiated in 2015—including in a speech to a joint session of Congress. He also welcomed President Trump's May 2018 withdrawal of the United States from the JCPOA and accompanying reimposition of U.S. sanctions on Iran's core economic sectors. A few days before President Trump's May announcement, Netanyahu presented information that Israeli intelligence operatives apparently seized in early 2018 from an Iranian archive. He used the information to question Iran's credibility and highlight its potential to parlay existing know-how into nuclear-weapons breakthroughs after the JCPOA expires.2021 In his September 2018 speech before the U.N. General Assembly, Netanyahu claimed that Iran maintains a secret "atomic warehouse for storing massive amounts of equipment and materiel."2122 An unnamed U.S. intelligence official was quoted as saying in response, "so far as anyone knows, there is nothing in [the facility Netanyahu identified] that would allow Iran to break out of the JCPOA any faster than it otherwise could."2223 In September 2019, Netanyahu presented satellite photos in an effort to support claims that Iran had built a facility for secret nuclear weapons-related work before destroying the facility in June 2019.23

U.S.-Iran tensions since the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA have led to greater regional uncertainty, with implications for Israel. During 2019, Iran has retaliated against U.S. sanctions by targeting U.S. military drones and seizing other countries' commercial vessels in the Persian Gulf. In July, Iran announced that it would gradually enrich uranium beyond JCPOA-imposed limits absent an easing of sanctions or their effects.

The United States and other international actors are still evaluating Iran's possible role in a September attack on oil facilities in Saudi Arabia.As U.S. officials have taken various political and military actions that appear focused on protecting U.S. military installations and Gulf shipping without triggering a major escalation, Israel's approach has attracted attention. Foreign Minister Yisrael Katz announced in August that Israel is providing intelligence to a U.S.-led coalition seeking to secure shipping routes in the Strait of Hormuz, and asserted—in the wake of a July visit to the United Arab Emirates—that Israel is strengthening ties with Arab Gulf states.2425 Iran has declared that Israeli involvement in the Gulf could provoke conflict.2526 The specter of escalation could possibly work against efforts to build international support for the coalition.26

Some sources suggest that the United States and Gulf states may consider addressing tensions with Iran through negotiation or accommodation,27 perhaps leaving Israel more directly responsible to manage its regional rivalry with Iran and its allies.27 In an August 2019 interview, Secretary of State Michael Pompeo expressed confidence that, in the event of conflict between Israel and Iran, President Trump would do "all that is necessary" to ensure Israel's protection and support its right to defend itself.28

Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon

Hezbollah

Lebanese Hezbollah is Iran's closest and most powerful non-state ally in the region. Hezbollah's forces and Israel's military have sporadically clashed near the Lebanese border for decades—with the antagonism at times contained in the border area, and at times escalating into broader conflict.29 Speculation persists about the potential for wider conflict and its regional implications.30 Israeli officials have sought to draw attention to Hezbollah's buildup of mostly Iran-supplied weapons—including reported upgrades to the range, precision, and power of its projectiles—and its alleged use of Lebanese civilian areas as strongholds.31

Ongoing tension between Israel and Iran raises questions about the potential for Israel-Hezbollah conflict. Various sources have referenced possible Iran-backed Hezbollah initiatives to build precision-weapons factories in Lebanon.32 In late 2018 and early 2019, Israel's military undertook an effort—dubbed "Operation Northern Shield"—to seal six Hezbollah attack tunnels to prevent them from crossing into Israel.33

Israeli measures aimed at constraining and deterring Hezbollah include consultations with the U.N. Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL).34 After reports in August 2019 that Israel may have targeted Hezbollah personnel and advanced drone and missile technology in Syria and Lebanon, Israeli officials and Hezbollah leaders each made public statements blaming the other side for increased tensions.35 Hezbollah appeared to respond to Israel in early September with cross-border fire from Lebanon targeting an Israeli military unit,36 amid reports that Hezbollah sought to retaliate but avoid escalation toward war.37

Syria and Iraq: Reported Israeli Airstrikes Against Iran-Backed Forces

Israel has reportedly undertaken airstrikes in conflict-plagued Syria and Iraq based on concerns that Iran and its allies could pose threats to Israeli security from there. Iran's westward expansion of influence into Iraq and Syria over the past two decades has provided it with more ways to supply and support Hezbollah, apparently leading Israel to increasingly broaden its regional theater of military action.38 While Israeli actions have been episodic, one media report has said that "the accelerating pace of violent strikes … has raised the possibility that even a minor attack could spiral into a larger conflict."39

Since 2018, Israeli and Iranian forces have repeatedly targeted one another in Syria or around the Syria-Israel border. After Iran helped Syria's government regain control of much of the country, Israeli leaders began pledging to prevent Iran from constructing and operating bases or advanced weapons manufacturing facilities in Syria.40 In January 2019, Prime Minister Netanyahu said that Israel had targeted Iranian and Hezbollah targets in Syria "hundreds of times."41 U.S. involvement in Syria could affect future Israeli calculations there. The U.S. base at At Tanf in southern Syria has reportedly "served as a bulwark against Iran's efforts to create a land route for weapons from Iran to Lebanon."42 Russia, its airspace deconfliction mechanism with Israel, and some advanced air defense systems that it has deployed or transferred to Syria also influence the various actors involved.43

In Iraq, reports suggest that beginning in summer 2019, Israel began conducting airstrikes against weapons depots or convoys that are connected with Iran-allied Shiite militias. Some of these militias are active members of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) that Iraqi leaders are attempting to bring under government control.44 One strike in July supposedly targeted a cargo of guided missiles that Iran allegedly intended to transfer to Syria.45 A senior U.S. official was cited as saying that Israel was "pushing the limits" because the airstrikes could result in Iraqi leaders demanding that the U.S. military leave Iraq.46 In August, the chief Pentagon spokesperson issued a statement criticizing "any potential actions by external actors inciting violence in Iraq," adding that Iraq's government has the right "to control their own internal security and protect their democracy."47 Iraqi National Security Advisor and Popular Mobilization Commission head Falih al Fayadh said that Iraq wants to avoid taking sides and being "pushed into a war."48 Israeli officials have not directly commented on the strikes in Iraq. During the August timeframe when the international media was following the strikes closely, Prime Minister Netanyahu said, "Any country that allows its territory to be used for aggression against Israel will face the consequences,"49 and Finance Minister Moshe Kahlon said that there are "things being attributed to us that aren't ours."50

Golan Heights51

On March 25, 2019, President Trump signed a proclamation stating that the United States recognizes the Golan Heights (hereinafter, the Golan) to be part of the State of Israel.52 The proclamation stated that "any possible future peace agreement in the region must account for Israel's need to protect itself from Syria and other regional threats"53—presumably including threats from Iran and the Iran-backed Lebanese group Hezbollah. Israel gained control of the Golan from Syria during the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, and effectively annexed it unilaterally by applying Israeli law to the region in 1981 (see Figure 1).54

President Trump's proclamation changed long-standing U.S. policy on the Golan. Since 1967, successive U.S. Administrations supported the general international stance that the Golan is Syrian territory occupied by Israel, with its final status subject to negotiation. In reaction to the U.S. proclamation, others in the international community have insisted that the Golan's status has not changed.55 In Congress, Senate and House bills introduced in February 2019 (S. 567 and H.R. 1372) support Israeli sovereignty claims to the Golan, and would treat the Golan as part of Israel in any existing or future law "relating to appropriations or foreign commerce." Additionally, 10 Senators wrote a letter to the President in April urging him to take additional steps that would have the effect of treating the Golan Heights no differently than Israel for various U.S. government purposes.56

For decades after 1967, various Israeli leaders, reportedly including Prime Minister Netanyahu as late as 2011,57 had entered into talks with Syria aimed at returning some portion of the Golan as part of a lasting peace agreement. However, in the context of Syria's civil war and other changing factors, Netanyahu shifted focus from negotiating with Syria on a "land for peace" basis to obtaining international support for Israel's claims of sovereignty. As part of the periodic conflict in Syria between Israel and Iran, some Iranian missiles have targeted Israeli positions in the Golan.58

The Syrian government denounced the U.S. policy change as an illegal violation of Syrian sovereignty and territorial integrity, and insisted that Syria is determined to recover the Golan.59 Additionally, observers have argued that the policy change could unintentionally bolster Syrian President Bashar al Asad within Syria by rallying Syrian nationalistic sentiment in opposition to Israel's claims to the Golan and deflecting attention from Iran's activities inside Syria.60

Since 1974, the U.N. Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) has patrolled an area of the Golan Heights between the regions controlled by Israel and Syria, stationing more than 800 troops from five countries there as of July 2019.61 During that time, Israel's forces in the Golan have not faced serious military resistance to their continued deployment, despite some security threats and diplomatic challenges. Periodic resolutions by the U.N. General Assembly have criticized Israel's occupation as hindering regional peace and Israel's settlement and de facto annexation of the Golan as illegal.62

Israeli-Palestinian Issues Under the Trump Administration63

President Trump has expressed interest in helping resolve the decades-old Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but many observers voice doubts about his Administration's ability to get the two sides to negotiate, let alone achieve a conflict-ending agreement.64 Past Administrations also have struggled to make progress on this issue, but developments during this Administration have raised some unique challenges. After the President's recognition of Jerusalem as Israel's capital in December 2017, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and Palestinian Authority (PA), led by PLO Chairman and PA President Mahmoud Abbas, cut off diplomatic ties with the United States. The Palestinians have insisted that U.S. statements and actions are biased toward Israel and that the Administration therefore cannot be trusted as an honest broker.65

The Administration claims that it has prepared a plan that proposes specific solutions on the core issues of the conflict, and anticipates releasing it sometime after Israel's September 2019 elections, but the release of the plan has been repeatedly postponed and some question whether it will ever happen.66 In a May 2019 closed-door meeting with some American Jewish leaders, Secretary of State Pompeo reportedly acknowledged that the U.S. plan might not gain traction.67 In an apparent effort to provide economic ballast to the plan, the Administration released a $50 billion investment and infrastructure proposal in June for the West Bank and Gaza and Palestinians in Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon, accompanied by a workshop in Bahrain.68 No official Israeli or Palestinian representatives attended the workshop—only a few from the private sector—and the Arab state representatives that attended did not make specific monetary commitments.

The Administration has taken several measures that PLO/PA leaders have interpreted as attempts to pressure them into a political process that would favor Israel on core issues of Israeli-Palestinian dispute—security, borders, settlements, Palestinian refugees, and Jerusalem's status—and prevent statehood for Palestinians.69 The measures include:

- The opening of the U.S. embassy to Israel in Jerusalem in May 2018, and the subsuming of the U.S. consulate general—previously an independent diplomatic mission to the Palestinians—under the embassy's authority in March 2019.

- An end to all U.S. bilateral aid for Palestinians—including economic and security assistance—and to U.S. contributions from global humanitarian accounts (managed by the State Department) to the U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA).70

- The U.S.-mandated closure of the PLO representative office in Washington, DC.

- President Trump's March 2019 proclamation that the Golan Heights—a territory that Israel captured from Syria in the 1967 Arab-Israeli war (as mentioned above)—is part of Israel. Israel captured the West Bank and Gaza in that same war, from Jordan and Egypt respectively.

After President Trump's Golan Heights proclamation in March 2019, Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu pledged—as part of his election campaign in April—to begin annexing Israeli settlements in the West Bank.71 Secretary of State Pompeo, in a subsequent interview, said that Netanyahu's statement did not cause him concern.72 In June 2019, U.S. Ambassador to Israel David Friedman said that under certain circumstances, Israel "has the right to retain some, but unlikely all, of the West Bank,"73 though an unnamed U.S. official then said that the United States has not discussed any Israeli plan for annexation of any portion of the West Bank.74 Some Members of Congress have publicly expressed concerns about Israel taking unilateral steps to annex parts of the West Bank.75 During his September 2019 campaign, Netanyahu announced his specific intention if reelected to annex the Jordan Valley—the lightly populated area along Jordan's western border that Israel has largely used as a defensive buffer area since 1967.

PLO/PA officials object to the United States using economic carrots and sticks to entice or pressure the Palestinians into conceding on the fundamental political demands of their national cause—particularly statehood in the West Bank and Gaza and a capital in Jerusalem.76 Major Arab Gulf states (Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar) have signaled openness to proposals for assisting Palestinians economically, without necessarily softening their support for the Palestinians on core political issues.77 Jordan and Egypt—the two Arab states that have peace treaties with Israel—reportedly harbor concerns about efforts by the United States to use them or other countries to legitimize political outcomes that may favor Israel at the Palestinians' expense.78

|

PA Revenue Standoff with Israel and Budgetary Crisis A standoff between the PA and Israel during 2019 regarding tax revenues has threatened the PA's fiscal stability and the broader political and security situation. In February, Israel announced that it would withhold a portion of the tax revenue it collects for the PA because—pursuant to a law passed by the Knesset in 2018—Israel had determined that this amount represented PLO/PA payments made on behalf of individuals allegedly involved in terrorist acts.79 In response, PA President Abbas announced that the PA would completely reject monthly revenue transfers from Israel if it withheld any amount, even though the transfers comprise approximately 65% of the PA budget.80 The PA reportedly has received temporary financial support from the private sector, local banks, and other Arab countries to make up for some of the $150-200 million in estimated monthly transfers on which the PA relies.81 The Palestinians could face a major financial and security crisis if they continue to reject transfer revenue payments from Israel.82 Cuts to the salaries of public sector employees in the West Bank and Gaza—including security officials—risk destabilizing both territories.83 In August, Israel and the PA relieved the crisis somewhat by retroactively changing the terms on fuel taxes and their collection, thus allowing a transfer from Israel of nearly $570 million to the PA, and the prospect of an additional $60 million in revenue per month going forward.84 Israeli officials reportedly also promised the PA that "creative solutions" would be found after September elections in Israel to transfer the rest of the revenues.85 |

Domestic Issues and: September 201917 Elections and Prospects for a New Government

Following elections held on September 17, 2019, the outcome of the government formation process looks unclear. It could have significant implications for the country's leadership and future policies. After Israeli President Reuven Rivlin identifies the person that he deems to have the best chance to form a government—probably either Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu of the Likud party or former Israel Defense Forces chief of staff Benny Gantz of the Kahol Lavan party—that person will have four weeks to assemble a coalition that can attract majority support (at least 61 out of 120 seats) in Israel's Knesset. Rivlin can grant an additional two-week extension at his discretion—potentially taking the process into November. If no government is formed at that point, Rivlin can give another person the chance to form one within the same timeframe, or the Knesset can vote to hold another round of elections—as it did in May 2019 after Netanyahu failed to form a government following April elections. Netanyahu will continue to lead a caretaker government until someone forms a new government. See Appendix A for descriptions of Knesset parties and their leaders, as well as the number of seats each is unofficially projected to receive.

Some observers assert that a "unity government" involving both Likud and Kahol Lavan, which could include a rotating prime ministerial arrangement, might be more likely than other outcomes.86 Gantz has said that he will not join a unity government that includes Netanyahu given corruption charges that are pending against him (see Appendix B). Thus, for a unity government to come together, either Gantz would need to change his mind, or Likud would need to replace Netanyahu with a new party leader.87 Before the election, all Likud Knesset candidates signed a pledge stating that Netanyahu would be the party's only candidate for prime minister.88

A key advocate for a unity government is Avigdor Lieberman of the Yisrael Beitenu party. Based on the election results, it appears that Lieberman's support could be decisive both in influencing President Rivlin's choice of the person to form the government, and in determining the government's eventual composition. In May, Lieberman had refused to join a Netanyahu-led government that included Jewish ultra-Orthodox parties, thus triggering the September redo election. Immediately following the redo, Lieberman called for a unity government that includes Yisrael Beitenu and commits to greater secularization of Israeli life in the military, education, public transportation and commerce, and other sectors.89 He also voiced his opposition to another round of elections, and said he would refuse to serve in a government with the Arab Joint List.90

Netanyahu's apparent failure to gain voter support for a right-wing and ultra-Orthodox majority to partner with him could decrease the likelihood that Israel's Knesset and government will pursue initiatives mooted during the campaign, such as the following: an immunity law seeking to protect Netanyahu from prosecution,91 annexation of the Jordan Valley or other West Bank areas,92 and measures weakening judicial review of legislation.93 A pre-indictment hearing on the charges against Netanyahu is scheduled for October 2.

Appendix A.

Israeli Political Parties in the Knesset and Their Leaders

RIGHT

Likud (Consolidation) – 32 Knesset seats projected Elections

RIGHT

At the end of May 2019, Prime Minister Netanyahu was unable to form a government within the timeframe prescribed under Israeli law after Knesset elections held in April. It was the first time in Israel's history that an election did not result in the formation of a government. Instead, the new Knesset dissolved itself and called for new elections.86 In the meantime, Netanyahu is leading Israel under continuity-of-government laws.

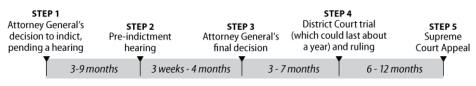

Reports suggest that had Netanyahu formed a government in May, the Knesset could have passed legislation granting its members immunity from prosecution during their Knesset service, thus shielding Netanyahu from pending corruption charges (see Appendix A).87 With new elections scheduled for September 17, 2019, and the government formation process taking up to four to six weeks, it is unclear whether Netanyahu—if selected by Israeli President Reuven Rivlin to form a government after the elections—could assemble a coalition that can act in time to protect Netanyahu from indictment.88 Netanyahu's pre-indictment hearing is scheduled for early October.

The September elections and the subsequent government formation process could have significant implications for the country's leadership and future policies. A victory for Netanyahu could bolster the argument that a popular mandate should reduce his culpability for the pending corruption charges. Also, some leading figures on the right side of the political spectrum (from which Netanyahu has generally drawn most of his support when forming coalitions) have proposed bills that could reduce judicial checks on Knesset majorities, while parties in the center and on the left have positioned themselves as defenders of the Supreme Court's institutional role in Israel's democracy.89 See Appendix B for descriptions of the major parties and their leaders.

Netanyahu's Likud party and the centrist Kahol Lavan party tied for the most Knesset seats in the April elections, with 35 each, and appear to be heading for another close contest in the September elections. Because polls suggest that each party could struggle to assemble a majority coalition, various scenarios are possible, such as a "unity government" including both parties or another stalemate leading to a third round of elections.90 All Likud Knesset candidates signed a pledge in August stating that Netanyahu would be the party's only candidate for prime minister, but Kahol Lavan leader Benny Gantz has called for a unity government without Netanyahu.91

Appendix A.

Suggested Indictments Against Netanyahu and Additional Steps of the Legal Process

|

Suggested Indictments |

|

Case 1000: Netanyahu received gifts from Hollywood mogul Arnon Milchan, in return for political favors The charge: Fraud and breach of trust From the draft indictment: "There is enough evidence to prove that the gifts, given in large scale and in unusual ways, had been received in exchange for actions by Netanyahu." Netanyahu's defense: It is acceptable to receive some gifts from friends; some decisions were against Milchan's interests |

|

Case 2000: Netanyahu and Yedioth Ahronoth publisher Arnon Mozes struck a deal: Favorable coverage in return for legislation to damage Sheldon Adelson-owned newspaper Israel Hayom The charge: Fraud and breach of trust From the draft indictment: "Evidence allegedly shows that Netanyahu, in his conversations with Mozes, violated the trust he owes to the public, and severely hurt the image of public service and public faith in it." Netanyahu's defense: Mozes and I [Netanyahu] fooled each other; there was never any intention to follow through |

|

Case 4000: As communication minister, Netanyahu took steps that benefited Shaul Elovitch who controlled Bezeq—in return for favorable coverage in Bezeq's Walla News site The charge: Bribery, fraud and breach of trust From the draft indictment: "Based on ... actions and circumstantial evidence, the attorney general has reached a clear conclusion, by which corrupt, improper motives were at the core of Netanyahu's actions." Netanyahu's defense: Favorable coverage isn't bribery |

|

|

Sources: For "Suggested Indictments," the content comes verbatim from Ha'aretz, and CRS adapted the graphic, with one bracketed addition merely for purposes of clarification. For "Steps in the Legal Process, and the Estimated Time Between Them," CRS prepared the graphic and made some slight content adjustments to underlying source material from Britain Israel Communications and Research Centre.

Appendix B.

Major Israeli Political Parties and Their Leaders

|

RIGHT |

|

|

Leader: Binyamin Netanyahu |

|

|

Yisrael Beitenu (Israel Our Home) Leader: Avigdor Lieberman |

|

|

Yamina (Right) Leader: Ayelet Shaked |

| Otzma Yehudit (Jewish Power) Jewish nationalist party characterized as extreme by many mainstream Israeli observers. Ideologically related to Kach, a far-right party that was led in the 1980s by the late Meir Kahane—an American-born rabbi and activist who helped found the Jewish Defense League and was assassinated in 1990—and eventually outlawed.

|

|

LEFT |

|

|

|

Labor (Avoda) Leader: Amir Peretz |

|

|

Democratic Union Leader: Nitzan Horowitz |

|

CENTER |

|

|

|

Kahol Lavan (Blue and White) – 33 seats projectedMerger between two centrist parties, Hosen L'Yisrael (Resilience) and Yesh Atid (There Is a Future). Gantz and Lapid have agreed to take turns as prime minister if elected, with Gantz serving as prime minister and Lapid as foreign minister for the first two years and eight months before switching. Leaders: Benny Gantz and Yair Lapid Born in 1963, Lapid came to politics after a career as a journalist, television presenter, and author. He founded the Yesh Atid party in 2012, and from 2013 to 2014 he served as finance minister. |

|

ULTRA-ORTHODOX |

|

|

|

Shas (Sephardic Torah Guardians) Leader: Aryeh Deri |

|

|

United Torah Judaism Leader: Yaakov Litzman |

|

|

|

|

|

Joint List – 12 seats projectedElectoral slate featuring four Arab parties that combine socialist, Islamist, and Arab nationalist political strains: Hadash (Democratic Front for Peace and Equality), Ta'al (Arab Movement for Renewal), Ra'am (United Arab List), Balad (National Democratic Assembly) Leader: Ayman Odeh |

Sources: Various open sources.

Knesset seat projections reported by Ha'aretz as of September 18, 2019. Appendix B. Suggested Indictments Against Netanyahu and Additional Steps of the Legal ProcessSuggested Indictments

Case 1000: Netanyahu received gifts from Hollywood mogul Arnon Milchan, in return for political favors

The charge: Fraud and breach of trust

From the draft indictment: "There is enough evidence to prove that the gifts, given in large scale and in unusual ways, had been received in exchange for actions by Netanyahu."

Netanyahu's defense: It is acceptable to receive some gifts from friends; some decisions were against Milchan's interests

Case 2000: Netanyahu and Yedioth Ahronoth publisher Arnon Mozes struck a deal: Favorable coverage in return for legislation to damage Sheldon Adelson-owned newspaper Israel Hayom

The charge: Fraud and breach of trust

From the draft indictment: "Evidence allegedly shows that Netanyahu, in his conversations with Mozes, violated the trust he owes to the public, and severely hurt the image of public service and public faith in it."

Netanyahu's defense: Mozes and I [Netanyahu] fooled each other; there was never any intention to follow through

Case 4000: As communication minister, Netanyahu took steps that benefited Shaul Elovitch who controlled Bezeq—in return for favorable coverage in Bezeq's Walla News site

The charge: Bribery, fraud and breach of trust

From the draft indictment: "Based on ... actions and circumstantial evidence, the attorney general has reached a clear conclusion, by which corrupt, improper motives were at the core of Netanyahu's actions."

Netanyahu's defense: Favorable coverage isn't bribery

Sources: For "Suggested Indictments," the content comes verbatim from Ha'aretz, and CRS adapted the graphic, with one bracketed addition merely for purposes of clarification. For "Steps in the Legal Process, and the Estimated Time Between Them," CRS prepared the graphic and made some slight content adjustments to underlying source material from Britain Israel Communications and Research Centre.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Gad Lior, "Cost of border fences, underground barrier, reaches NIS 6bn," Ynetnews, January 30, 2018. |

|||||||||||||

| 2. |

Ibid.; CRS Report RL33476, Israel: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti. |

|||||||||||||

| 3. |

Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris, "Worldwide deployment of nuclear weapons, 2017," Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 73(5), 2017, pp. 289-297. |

|||||||||||||

| 4. |

Felicia Schwartz and Dov Lieber, "China Tech Push in Israel Stirs Security Fears," Wall Street Journal, February 12, 2019; Yaakov Lappin, "Chinese company set to manage Haifa's port, testing the US-Israeli alliance," Jewish News Syndicate, January 29, 2019; Shira Efron, et al., The Evolving Israel-China Relationship, RAND Corporation, 2019; Yasmin Yablonko, "Chinese take growing slice of Israeli tech investment," Globes, October 30, 2018. |

|||||||||||||

| 5. |

Schwartz and Lieber, op. cit. footnote 4. |

|||||||||||||

| 6. |

Yossi Melman, "China Is Spying on Israel to Steal U.S. Secrets," foreignpolicy.com, March 24, 2019; Ben Caspit, "Does China endanger Israel's security?" Al-Monitor Israel Pulse, January 11, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 7. |

Efron, et al., op. cit. footnote 4, pp. 15-20. |

|||||||||||||

| 8. |

Hiddai Segev, Doron Ella, and Assaf Orion, "My Way or the Huawei? The United States-China Race for 5G Dominance," Institute for National Security Studies Insight No. 1193, July 15, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 9. |

Roie Yellinek, "The Israel-China-U.S. Triangle and the Haifa Port Project," Middle East Institute, November 27, 2018. Section 1289 of S. 1790 also contains a provision stating that the United States has an interest in continuing to use the naval base in Haifa, but has "serious security concerns" with respect to the leasing arrangements at the Haifa port. Reportedly, the Israeli government plans to limit sensitive roles at the port to Israelis with security clearances. Jack Detsch, "Pentagon repeats warning to Israel on Chinese port deal," Al-Monitor Israel Pulse, August 7, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 10. |

Efron, et al., op. cit. footnote 4, pp. 107, 109; "China Harbour Engineering subsidiary to build new port at Ashdod in Israel," Reuters, June 23, 2014. |

|||||||||||||

| 11. |

Daniel Schmil, "5 Chinese cos to bid for TA light rail tunnels," Globes, May 20, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 12. |

Eli Lake, "Secret U.S.-Israel Nuclear Accord in Jeopardy," Washington Times, May 6, 2009. |

|||||||||||||

| 13. |

Kristensen and Norris, op. cit. footnote 3; "Strategic Weapon Systems," Jane's Sentinel Security Assessment—Eastern Mediterranean, June 26, 2018; "Operation Samson: Israel's Deployment of Nuclear Missiles on Subs from Germany," Der Spiegel, June 4, 2012. |

|||||||||||||

| 14. |

CRS Report RL33476, Israel: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti; CRS Report RL33222, U.S. Foreign Aid to Israel, by Jeremy M. Sharp. |

|||||||||||||

| 15. |

Joshua S. Block, "An ally reminds us of its value," jpost.com, May 8, 2018; Marty Oliner, "US-Israel relationship: More critical than ever," The Hill, May 3, 2017. |

|||||||||||||

| 16. |

The United States and Israel do, however, have a Mutual Defense Assistance Agreement (TIAS 2675, dated July 23, 1952) in effect regarding the provision of U.S. military equipment to Israel, and have entered into a range of stand-alone agreements, memoranda of understanding, and other arrangements varying in their formality. |

|||||||||||||

| 17. |

"Trump says he talked Mutual Defense Pact with Netanyahu, will pick up after vote," Times of Israel, September 14, 2019.

|

|||||||||||||

|

See, e.g., Dennis Ross and Stuart Eizenstat, "Israel should resist Trump's efforts to politicize support," The Hill, August 22, 2019. |

||||||||||||||

|

For information on this topic, see CRS Report R44017, Iran's Foreign and Defense Policies, by Kenneth Katzman. |

||||||||||||||

|

Israeli Prime Minister's Office, PM Netanyahu reveals the Iranian secret nuclear program, April 30, 2018. |

||||||||||||||

|

Israeli Prime Minister's Office, PM Netanyahu's Speech at the United Nations General Assembly, September 27, 2018. |

||||||||||||||

|

John Irish and Arshad Mohammed, "Netanyahu, in U.N. speech, claims secret Iranian nuclear site," Reuters, September 27, 2018. |

||||||||||||||

|

David M. Halbfinger and David E. Sanger, "Israel's Leader Says Iran Hid a Nuclear Weapons Site," New York Times, September 10, 2019. |

||||||||||||||

|

Alexander Griffing, "On Trump and Iran, the UAE Shifts Strategy — and Israel Should Take Heed," haaretz.com, August 21, 2019. |

||||||||||||||

|

Arie Egozi, "Israel Meets with UAE, Declares It's Joining Persian Gulf Coalition," Breaking Defense, August 16, 2019. |

||||||||||||||

| 26. |

Ibid. |

|||||||||||||

| 27. |

|

|||||||||||||

| 28. |

Department of State, Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo with Hugh Hewitt of The Hugh Hewitt Show, August 29, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 29. |

CRS Report R44759, Lebanon, by Carla E. Humud; CRS In Focus IF10703, Lebanese Hezbollah, by Carla E. Humud. |

|||||||||||||

| 30. |

For possible conflict scenarios, see Hanin Ghaddar, "How Will Hezbollah Respond to Israel's Drone Attack?" Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Policywatch 3171, August 28, 2019; Seth G. Jones and Maxwell B. Markusen, "The Escalating Conflict with Hezbollah in Syria," Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 2018; Israel's Next Northern War: Operational and Legal Challenges, Jewish Institute for National Security of America, October 2018. |

|||||||||||||

| 31. |

See, e.g., Jonathan Spyer and Nicholas Blanford, "UPDATE: Israel raises alarm over advances by Hizbullah and Iran," Jane's Intelligence Review, January 11, 2018. |

|||||||||||||

| 32. |

Ben Caspit, "Hezbollah, Israel losing red lines," Al-Monitor Israel Pulse, September 4, 2019; Katherine Bauer et al., "Iran's Precision Missile Project Moves to Lebanon," Washington Institute for Near East Policy, December 2018. |

|||||||||||||

| 33. |

Israeli Prime Minister's Office, PM Netanyahu in the North—Israel Attacked a Warehouse with Iranian Weapons at Damascus International Airport, January 13, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 34. |

For more on UNIFIL, see CRS Report R44759, Lebanon, by Carla E. Humud. |

|||||||||||||

| 35. |

"As Hezbollah Leader Blasts Israel, Iran-backed Militias Struck on Iraq-Syria Border," haaretz.com, August 26, 2019; Israeli Prime Minister's Office, PM and DM Netanyahu Holds Security Tour in the North and Assessment of the Situation with IDF Chief-of-Staff, GOC Northern Command and Other Senior Officers, August 25, 2019; Amos Harel, "Beirut Strike Target: Vital Iranian Device for Hezbollah's Mass Missile Production," haaretz.com, August 28, 2019; "Israel is making the case for war, in public, against Lebanon," CNN, August 30, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 36. |

David M. Halbfinger, "Hezbollah, Citing Israeli Attacks in Syria and Lebanon, Counters With Raid on Military Post," New York Times, September 2, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 37. |

Ghaddar, op. cit. footnote |

|||||||||||||

| 38. |

David Halbfinger, et al., "Israel Counters Iran in Flare-Up of Shadow War," New York Times, August 29, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 39. |

Ibid. |

|||||||||||||

| 40. |

See, e.g., Israeli Prime Minister's Office, PM Netanyahu's Speech at the United Nations General Assembly, September 27, 2018. |

|||||||||||||

| 41. |

Israeli Prime Minister's Office, PM Netanyahu's Remarks at the Start of the Weekly Cabinet Meeting, January 13, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 42. |

Dion Nissenbaum, et al., "Trump Orders Troops out of Syria," Wall Street Journal, December 20, 2018. See also Lara Seligman, "U.S. Considering Plan to Stay in Remote Syrian Base to Counter Iran," foreignpolicy.com, January 25, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 43. |

CRS In Focus IF10858, Iran and Israel: Tension Over Syria, by Carla E. Humud, Kenneth Katzman, and Jim Zanotti. |

|||||||||||||

| 44. |

For information on the PMF, see CRS In Focus IF10404, Iraq and U.S. Policy, by Christopher M. Blanchard. |

|||||||||||||

| 45. |

Alissa J. Rubin and Ronen Bergman, "Israel Is Believed to Be Behind a July Airstrike on a Weapons Depot in Iraq," New York Times, August 23, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 46. |

Ibid. |

|||||||||||||

| 47. |

Department of Defense, Statement on Recent Attacks in Iraq, August 26, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 48. |

Rubin and Bergman, op. cit. footnote |

|||||||||||||

| 49. |

Israeli Prime Minister's Office, PM and DM Netanyahu Holds Security Tour in the North and Assessment of the Situation with IDF Chief-of-Staff, GOC Northern Command and Other Senior Officers, op. cit. footnote |

|||||||||||||

| 50. |

"Netanyahu warns Israel will defend itself 'by any means necessary,'" Times of Israel, August 26, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 51. |

For background on the Golan Heights, see CRS Insight IN11081, Israel and Syria in the Golan Heights: U.S. Recognition of Israel's Sovereignty Claim, by Jim Zanotti and Carla E. Humud. |

|||||||||||||

| 52. |

White House, Proclamation on Recognizing the Golan Heights as Part of the State of Israel, March 25, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 53. |

Ibid. |

|||||||||||||

| 54. |

The area under Israel's control known as the Golan Heights is actually the western two-thirds of the geological Golan Heights—a plateau overlooking northern Israel. The eastern third remains under Syria's control, other than the zone monitored by the U.N. Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF). For background information on the Golan Heights, see Central Intelligence Agency, Syria-Israel: The Golan Heights in Perspective, January 1982, available at https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP83B00851R000400150002-5.pdf. |

|||||||||||||

| 55. |

U.N. Security Council statement, Security Council Members Regret Decision by United States to Recognize Israel's Sovereignty over Occupied Syrian Golan, March 27, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 56. |

Text of letter available at https://www.cotton.senate.gov/files/documents/Golan_Letter.pdf. |

|||||||||||||

| 57. |

"Israeli paper: Netanyahu talked peace with Syria," Associated Press, October 12, 2012. |

|||||||||||||

| 58. |

CRS In Focus IF10858, Iran and Israel: Tension Over Syria, by Carla E. Humud, Kenneth Katzman, and Jim Zanotti. |

|||||||||||||

| 59. |

"Syria: Trump's recognition of annexing the occupied Syrian Golan to Zionist entity represents highest degrees of contempt for international legitimacy," Syrian Arab News Agency, March 25, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 60. |

Tamara Qiblawi, "Trump's Golan Heights announcement met with a shrug in the Arab world," CNN, March 22, 2019; Bassam Barabandi, "Recognizing Golan Heights as Israeli is a gift for Assad, Iran," Al Arabiya, March 22, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 61. |

See https://undof.unmissions.org/ for general information on UNDOF, and https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/undof for information on troop numbers and contributing countries. |

|||||||||||||

| 62. |

See, e.g., The Syrian Golan—GA Resolution (A/RES/73/23), November 30, 2018, which the United States opposed. |

|||||||||||||

| 63. |

For additional background, see CRS In Focus IF11237, Israel and the Palestinians: Chronology of a Two-State Solution, by Jim Zanotti. |

|||||||||||||

| 64. |

See, e.g., Ami Ayalon, et al., "Trump's Peace Plan Is Immoral, Impractical—and Could Blow Up the Middle East," Politico Magazine, June 24, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 65. |

See, e.g., Khaled Abu Toameh, "Palestinians: No role for U.S. in peace after closure of J'lem consulate," jpost.com, March 3, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 66. |

Daniel C. Kurtzer, "The Illusion of Trump's Mideast Peace Plan," The American Prospect, April 16, 2019; Remarks by Robert Satloff, 2019 Soref Symposium Panel, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, May 2, 2019, video footage available at https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/inside-the-trump-administrations-middle-east-peace-effort-a-conversation-wi. |

|||||||||||||

| 67. |

"Exclusive: Pompeo delivers unfiltered view of Trump's Middle East peace plan in off-the-record meeting," Washington Post, June 2, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 68. |

For details of the plan, entitled Peace to Prosperity, see https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/MEP-narrative-document_FINAL.pdf and https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/MEP_programsandprojects.pdf. |

|||||||||||||

| 69. |

David M. Halbfinger, "'Very Hot' in the West Bank as Crisis Looms," New York Times, June 5, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 70. |

See CRS In Focus IF10644, The Palestinians: Overview and Key Issues for U.S. Policy, by Jim Zanotti; and CRS Report RS22967, U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians, by Jim Zanotti. |

|||||||||||||

| 71. |

"Netanyahu vows to annex West Bank settlements if re-elected," Associated Press, April 7, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 72. |

Transcript of remarks by Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo, Interview with Jake Tapper of CNN, Santiago, Chile, April 12, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 73. |

David M. Halbfinger, "Israel Has Right to Annex at Least Parts of West Bank, U.S. Envoy Says," New York Times, June 9, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 74. |

"U.S. envoy, in interview, does not rule out Israeli annexation in West Bank," Reuters, June 8, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 75. |

Congresswoman Nita Lowey, "Lowey, Engel, Deutch, Schneider Statement on a Two-State Solution," April 12, 2019; Chris Van Hollen and Gerald Connolly, "Congress cannot afford to ignore Netanyahu's embrace of the far right," Washington Post, April 10, 2019. For more information on settlements and U.S. policy, see CRS Report RL33476, Israel: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti. |

|||||||||||||

| 76. |

Saeb Erekat, "Trump Doesn't Want Mideast Peace," New York Times, May 23, 2019; Nabil Sha'ath, "We Palestinians Say to Trump: No to Bahrain, Bribes and Never-ending Occupation," haaretz.com, May 23, 2019; David M. Halbfinger, "Palestinian Business Leaders Reject Trump's Economic Overture," New York Times, May 21, 2019. For background information on U.S. policy regarding a Palestinian state, see CRS In Focus IF11237, Israel and the Palestinians: Chronology of a Two-State Solution, by Jim Zanotti. |

|||||||||||||

| 77. |

King Salman of Saudi Arabia said in February 2019 that his country "permanently stands by Palestine and its people's right to an independent state with the occupied East Jerusalem as its capital." "Saudi king reaffirms support for Palestinian state," Al Jazeera, February 12, 2019. Bahrain, as host of the event, reiterated its support in May for Palestinians on these same points. "Bahrain Stresses Commitment to Palestinian State After Backlash Over U.S.-led Peace Conference," haaretz.com, May 21, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 78. |

"Jordan king tells Trump team a Palestinian state the only way to peace," Times of Israel, May 29, 2019; "The Real Reason Egypt Is Unlikely to Join Kushner's Peace Plan - Despite Needing Help in Sinai," Reuters, June 27, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 79. |

Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Security Cabinet Communique, February 17, 2019; Ruth Levush, "Israel: Law on Freezing Revenues Designated for the Palestinian Authority Implemented," Law Library of Congress Global Legal Monitor, March 27, 2019. Israel is required to transfer these revenues to the PA according to the 1994 Paris Protocol between Israel and the PLO, and Palestinian leaders criticize any Israeli withholding as a violation of this agreement. |

|||||||||||||

| 80. |

U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), Humanitarian Bulletin: occupied Palestinian territory, February 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 81. |

Amira Hass, "The Palestinians' Not-so-secret Weapon Against Austerity," haaretz.com, August 9, 2019; Ahmad Melham, "How long can PA keep borrowing money from Palestinian banks?" Al-Monitor Palestine Pulse, May 7, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 82. |

Halbfinger, "'Very Hot' in the West Bank as Crisis Looms," op. cit. footnote |

|||||||||||||

| 83. |

Hass, op. cit. footnote |

|||||||||||||

| 84. |

"Palestinians to get half-billion dollars from Israel in new tax deal," Ynetnews, August 22, 2019; Danny Zaken, "Palestinian, Israeli economies intertwined," Al-Monitor Israel Pulse, August 30, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 85. |

Shlomi Eldar, "Israel, PA find creative ways to save West Bank from economic collapse," Al-Monitor Israel Pulse, August 29, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 86. |

| |||||||||||||

| 87. |

Raoul Wootliff, "Report: 'Override' law to save PM from trial will be part of coalition deal," Times of Israel, May 22, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 88. |

Shlomi Eldar, "Netanyahu's deal of the century: Immunity in exchange for annexation," Al-Monitor Israel Pulse, September 4, 2019; Ronen Bergman, "Netanyahu the 'Magician' May Be Out of Tricks, Pundits Say," New York Times, June 2, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 89. |

Wootliff, op. cit. footnote 87. |

|||||||||||||

| 90. |

Ruth Eglash, "Israel's do-over election this month may yield another deadlock. Then what happens?" Washington Post, September 6, 2019. |

|||||||||||||

| 91. | Israeli scholar Reuven Hazan, quoted in David M. Halbfinger and Isabel Kershner, "Narrow Election Imperils Future of Israeli Leader," New York Times, September 18, 2019. "Gantz says he'll consider joining Netanyahu government if he gets to be PM first," Times of Israel, August 11, 2019. "Liberman adamant 'unity government' is only option, sets out secular demands," Times of Israel, September 18, 2019. Ibid. Historically, no Arab party has joined an Israeli government coalition. Barak Ravid, "Israel election: Netanyahu fights for immunity as indictment looms," Axios, September 16, 2019. Ben Sales, "Netanyahu's push to annex the Jordan Valley, explained," Jewish Telegraphic Agency, September 10, 2019. |