Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards: Frequently Asked Questions

Changes from August 26, 2019 to June 1, 2021

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards: Frequently Asked Questions

Contents

- What Is NHTSA's Authority to Regulate the Fuel Economy of Motor Vehicles?

- What Is EPA's Authority to Regulate GHG Emissions from Motor Vehicles?

- What Is California's Authority to Regulate GHG Emissions from Motor Vehicles?

- What Are the Current CAFE and GHG Standards?

- How Do Manufacturers Comply with the Standards?

- What Is the Midterm Evaluation?

- What Is the Status of CAFE and GHG Standards Under the Trump Administration?

- The Revised Final Determination

- The Proposed SAFE Rule

- California's Actions

- What Is Meant by "Harmonizing" or "Aligning" the Standards?

- What Are Some of the Issues That Are Informing the Discussion on the Standards?

- (1) The Availability and Effectiveness of Technology

- (2) The Cost on the Producers or Purchasers of New Motor Vehicles

- (3) The Feasibility and Practicability of the Standards

- (4) The Impact of the Standards on Reduction of Emissions, Oil Conservation, Energy Security, and Fuel Savings by Consumers

- (5) The Impact of the Standards on the Automobile Industry

- (6) The Impacts of the Standards on Automobile Safety

- (7) The Impact of the GHG Emission Standards on the CAFE Standards and a National Harmonized Program

Figures

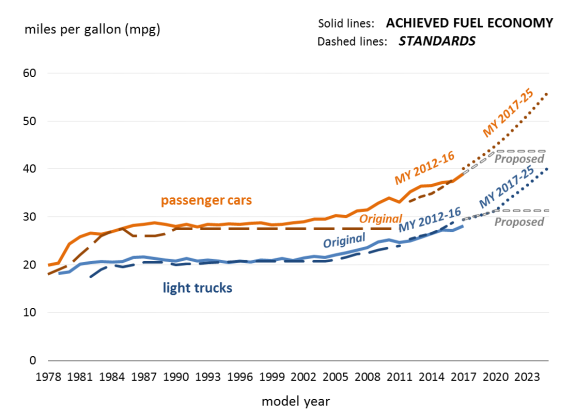

- Figure 1. CAFE Standards and Achieved Fuel Economy, MYs 1978-2026

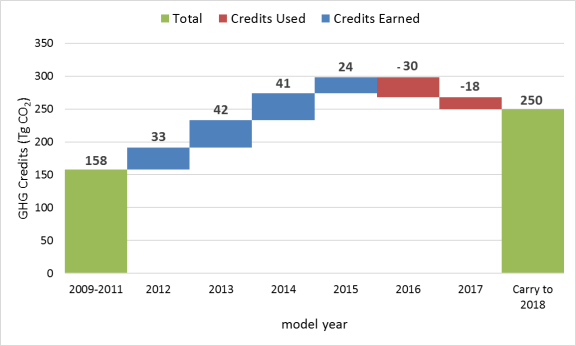

- Figure 2. Industry GHG Credit Generation and Use after MY 2017

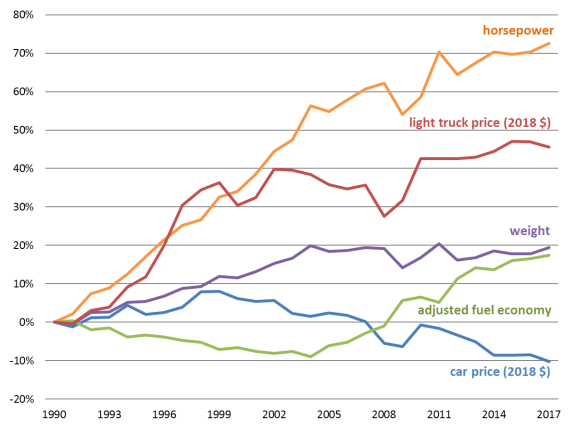

- Figure 3. Percentage Change in Selected Vehicle Attributes, MYs 1990-2017

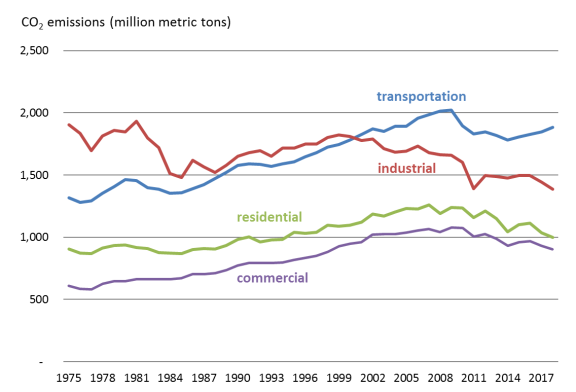

- Figure 4. Energy-Related CO2 Emissions by End-Use Sectors (1975-2018)

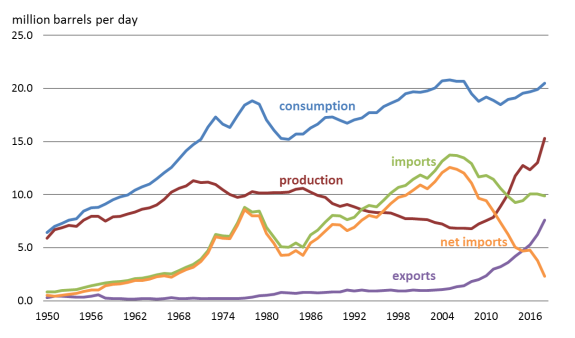

- Figure 5. U.S. Petroleum Statistics (1950-2018)

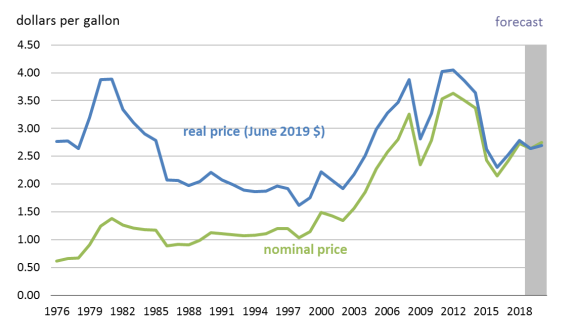

- Figure 6. Annual Motor Gasoline Regular Grade Retail Price (1975-2018)

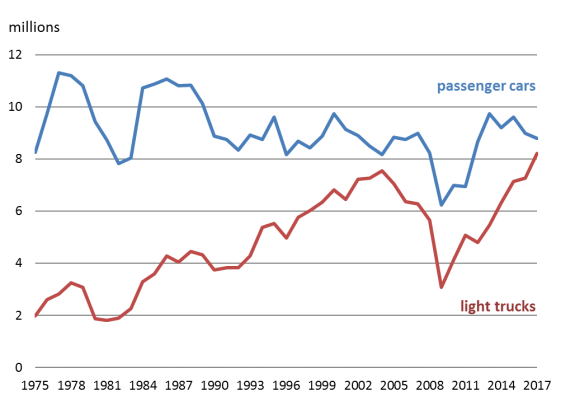

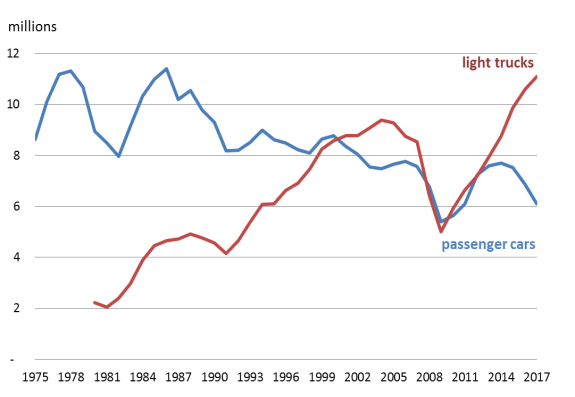

- Figure 7. U.S. Vehicles Sold, as Defined by Industry Categories (1975-2017)

- Figure 8. U.S. Vehicles Regulated Under the Standards, as Defined by Agency Compliance Categories (1975-2017)

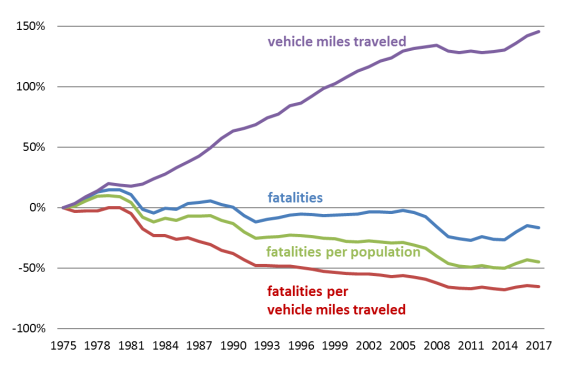

- Figure 9. Percentage Change in Selected Traffic Statistics (1975-2017)

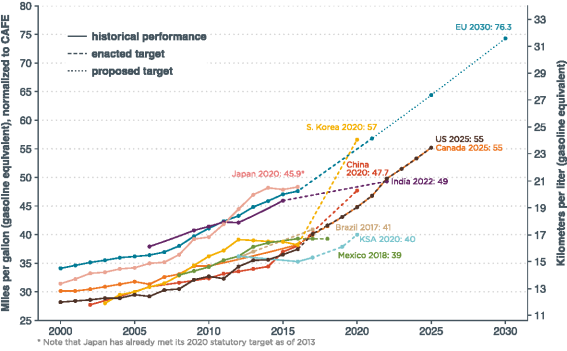

- Figure 10. Selection of International Vehicle Standards

Tables

- Table 1. MY 2017-2025 Combined Average Passenger Car and Light Truck CAFE and GHG Emission Standards

- Table 2. MY 2017 Manufacturer Fuel Economy and GHG Values

- Table 3. GHG Credit Balances after MY 2017

- Table 4. SAFE Vehicles Rule Regulatory Alternatives

- Table 5. Selected Differences between NHTSA's CAFE and EPA's GHG Programs

- Table 6. Selected Technology Penetrations to Meet the MY 2025 Standards

Summary

The Trump Administration announced on April 2, 2018, its intent to revise through rulemaking the federal standards that regulate fuel economy and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from new passenger cars and light trucks. These standardsVehicle Fuel Economy and

June 1, 2021

Greenhouse Gas Standards:

Richard K. Lattanzio

Frequently Asked Questions

Specialist in Environmental Policy

On January 20, 2021, President Joe Biden issued Executive Order 13990, “Protecting Public

Health and the Environment and Restoring Science to Tackle the Climate Crisis,” which directs

Linda Tsang

federal agencies to review regulations and other agency actions from the Trump Administration,

Legislative Attorney

including the rules that revised the Obama Administration’s vehicle fuel economy and

greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions standards.

Bill Canis Specialist in Industrial

Currently, the federal standards that regulate fuel economy and GHG emissions from new

Organization and Business

passenger cars and light trucks include the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards promulgated by the U.S. Department of Transportation'’s National Highway Traffic Safety

Administration (NHTSA) and the Light-Duty Vehicle GHG emissions standards promulgated by

the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). They are known collectively—along with California's Advanced Clean Car program— as the National Program. NHTSA derives its authorities for the standards from the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975, as amended (49 U.S.C. §§32901-32919). EPA derives its authorities for the standards from the Clean Air Act, as amended (42 U.S.C. §§7401-7626).

Under the Obama Administration, EPA and NHTSA promulgated joint rulemakings affecting model year (MY) 2012-2016 passenger cars and light trucks on May 7, 2010 (Phase 1). The agencies promulgated a second phase of standards affecting MYs 2017-2025 on October 15, 2012. The Phase 1 and the Phase 2 standards were preceded by multiparty agreements under which auto manufacturers pledgedProgram.

NHTSA and EPA promulgated the second (current) phase of CAFE and GHG emissions standards affecting model year (MY) 2017-2025 light-duty vehicles on October 15, 2012. Like the initial phase of standards for MYs 2012-2016, the Phase 2 rulemaking was preceded by a multiparty agreement, brokered by the Obama White House. The agreement included the State of California, 13 auto manufacturers, and the United Auto Workers union. The manufacturers agreed to reduce GHG emissions from most new passenger cars, sport utility vehicles, vans, and pickup trucks by about 50% by 2025, compared to 2010, with fleet-wide fuel economy rising to nearly 50 miles per gallon.

.

As part of the Phase 2 rulemaking, EPA and NHTSA made a commitment to conduct a midterm evaluation for the latter half of the standards (i.e., MYs 2022-2025, for which EPA had finalized requirements and NHTSA, due to statutory limits, had proposed "augural"“augural” requirements). On November 30, 2016, the Obama Administration'’s EPA released a proposed determination stating that the MY 2022-2025 standards remained appropriate and that a rulemaking to change them was not warranted. On January 12, 2017, EPA finalized the determination.

After President Trump took office, however, EPA and NHTSA announced their joint intention to reconsider the Obama Administration's final determination and reopenreopened the midterm evaluation process. EPA released a revised final determination on April 2, 2018. It stated, stating that the MY 2022-2025 standards were "“not appropriate and, therefore, should be revised,"” and that key assumptions in the January 2017 final determination—including gasoline prices, technology costs, and consumer acceptance—"“were optimistic or have significantly changed."” With this revision, EPA and NHTSA announced that they would initiate a new rulemaking. Until that rulemaking is complete, the current standards would remain in force.

On August 24, 2018, EPA and NHTSA proposed amendments to the existing CAFE and GHG emission standards. The Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient (SAFE) Vehicles Rule for MY 2021-2026 Passenger Cars and Light Trucks offers eight alternatives. The agencies' preferred alternative, if finalized, is to retain the existing standards through MY 2020 and then to freeze the standards at this level for both programs through MY 2026. A final rule has not yet been released.

In response to the proposals from the Trump Administration, California has restated its "continued support for the current National Program and California's standards." On December 12, 2018, California approved a regulatory amendment to clarify that automakers must still comply with the state's existing light-duty vehicle GHG standards through MY 2025—which includes standards in line with EPA's 2017 final determination and the 2012 rulemaking—even if EPA and NHTSA approve a rollback of the national rules. EPA granted California a Clean Air Act preemption waiver for its GHG standards on July 8, 2009.

A number of issues remain forefront regarding the CAFE and GHG emission standards, their design, purpose, and potential revision. These include (1) whether EPA has adequately justified its decision to revise the MY 2022-2025 standards and (2) whether California can continue to implement state standards that would be more stringent than the revised federal ones. These issues are informed by analyses regarding (1) whether the standards are technically and economically feasible; (2) the impact of the standards on GHG emissions and energy conservation; and (3) whether the standards adequately address consumer choice, safety, and other vehicle policies, both domestic and international.

This report addresses frequently asked questions about the federal and state standards that regulate fuel economy and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from new passenger cars and light trucks.

The agencies promulgated revisions to the CAFE and vehicle GHG emissions standards in two parts. On September 27, 2019, the agencies finalized the Safer, Affordable, Fuel-Efficient (SAFE) Vehicles Rule, Part One: One National Program, wherein NHTSA asserted its statutory authority to set nationally applicable fuel economy standards and EPA withdrew its Clean Air Act (CAA) preemption waiver it granted California’s GHG and Zero Emission Vehicle programs in January 2013. The agencies finalized the second part of the SAFE Vehicles Rule on March 31, 2020. The new rule targets a 1.5% increase in fuel economy each year from MY 2021 to MY 2026, compared to an approximate 5% increase each year under the withdrawn Phase 2 standards.

Debate continues over the stringency, design, and purpose of the CAFE and vehicle GHG emissions standards. The debate is informed by analyses regarding (1) whether the Obama-era standards are technically and economically feasible; (2) the impact of the standards on GHG emissions targets and energy conservation; (3) whether the standards adequately address consumer choice, safety, and other vehicle policies, both domestic and international; and (4) whether the EPA and NHTSA reopening and rule revision actions were lawful.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 10 link to page 13 link to page 15 link to page 17 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 19 link to page 21 link to page 28 link to page 29 link to page 31 link to page 37 link to page 41 link to page 5 link to page 9 link to page 12 link to page 18 link to page 31 link to page 37 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 20 link to page 28 link to page 28 link to page 34 link to page 36 link to page 38 link to page 42 Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards: Frequently Asked Questions

Contents

What Is the Biden Administration’s Proposal Regarding Vehicle Fuel Economy and GHG

Emissions Standards? ................................................................................................................... 1

What Is NHTSA’s Authority to Regulate the Fuel Economy of Motor Vehicles? .......................... 2 What Is EPA’s Authority to Regulate GHG Emissions from Motor Vehicles? ............................... 3 What Is California’s Authority to Regulate GHG Emissions from Motor Vehicles? ...................... 6 What Were the Standards Under the Obama Administration? ........................................................ 9 What Was the Midterm Evaluation? ............................................................................................... 11 Has the U.S. Motor Vehicle Market Changed Since 2010? ........................................................... 13 What Were the Standards Under the Trump Administration? ....................................................... 14

The Revised Final Determination ........................................................................................... 14 The Proposed SAFE Vehicles Rule ......................................................................................... 15 The Final SAFE Vehicles Rule, Part One................................................................................ 17 The Final SAFE Vehicles Rule, Part Two ............................................................................... 24 California’s Regulatory Activities ........................................................................................... 25

How Do Manufacturers Comply with the Standards? ................................................................... 27 What Is Meant by “Harmonizing” or “Aligning” the Standards? ................................................. 33 What Is Meant by “Decoupling” the Standards? ........................................................................... 37

Figures Figure 1. Transportation Sector Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Source, 2018 ............................... 1 Figure 2. U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Sector, 2018 ............................................................ 5 Figure 3. State Adoption of California’s GHG Standards ............................................................... 8 Figure 4. U.S. Light Vehicles Sales ............................................................................................... 14 Figure 5. CAFE Standards and Achieved Fuel Economy, MYs 1978-2026 ................................. 27 Figure 6. Industry GHG Credit Generation and Use ..................................................................... 33

Tables Table 1. Phase 2 MY 2017-2025 Combined Average Passenger Car and Light Truck

CAFE and GHG Emission Standards ......................................................................................... 10

Table 2. SAFE Vehicles Rule Regulatory Alternatives ................................................................. 16 Table 3. SAFE Vehicles Rule MY 2017-2026 Combined Average Passenger Car and

Light Truck CAFE and GHG Emissions Standards ................................................................... 24

Table 4. MY 2019 Manufacturer Fuel Economy and GHG Values ............................................... 30 Table 5. GHG Credit Balances After MY 2019 ............................................................................. 32 Table 6. Selected Differences Between NHTSA’s CAFE and EPA’s GHG Programs ................. 34

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 38

Congressional Research Service

Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards: Frequently Asked Questions

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5

Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards: Frequently Asked Questions

his report addresses frequently asked questions about federal and state regulation of fuel economy and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from new light-duty vehicles. Light-duty

T vehicles—a category that includes passenger cars and most sports utility vehicles (SUVs),

vans, and pickup trucks—accounted for nearly 60% of the transportation sector’s GHG emissions in 2018 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Transportation Sector Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Source, 2018

Source: EPA, Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2018, April 13, 2020. Note: Transportation emissions do not include emissions from nontransportation mobile sources such as agricultural and construction equipment.

The regulations include the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards promulgated by the U.S. Department of Transportation's’s (DOT’s) National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), the Light-Duty Vehicle GHG emissionsEmissions standards promulgated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and California'’s Advanced Clean Car program. The report chronicles the origins of the standards and reviews the past and present regulations. It also examines the relationship between the California and the federal vehicle programs.

What Is the Biden Administration’s Proposal Regarding Vehicle Fuel Economy and GHG Emissions Standards? On January 20, 2021, President Joe Biden issued Executive Order 13990, “Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science To Tackle the Climate Crisis,” announcing a national policy

to listen to the science; to improve public health and protect our environment; to ensure access to clean air and water; to limit exposure to dangerous chemicals and pesticides; to hold polluters accountable, including those who disproportionately harm communities of color and low-income communities; to reduce greenhouse gas emissions; to bolster resilience to the impacts of climate change; to restore and expand our national treasures

Congressional Research Service

1

Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards: Frequently Asked Questions

and monuments; and to prioritize both environmental justice and the creation of the well-paying union jobs necessary to deliver on these goals.1

To implement this policy, the executive order directs federal agencies to review regulations and other agency actions from the Trump Administration.2 Section 2 of the order directs an “Immediate Review of Agency Actions Taken Between January 20, 2017, and January 20, 2021” within the time frame specified, including “The Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient (SAFE) Vehicles Rule Part One: One National Program,” 84 Federal Register 51310 (September 27, 2019), by April 2021; and “The Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient (SAFE) Vehicles Rule for Model Years 2021–2026 Passenger Cars and Light Trucks,” 85 Federal Register 24174 (April 30, 2020), by July 2021.3

Pursuant to the executive order, NHTSA and EPA are scheduled to propose whether to suspend, revise, or rescind the Trump Administration’s vehicle standards by July 2021. In preview, President Biden’s presidential campaign platform had outlined a plan to address vehicle fuel economy and GHG emissions in “The Biden Plan to Build a Modern, Sustainable Infrastructure and an Equitable Clean Energy Future.” It stated that his Administration would

establish ambitious fuel economy standards that save consumers money and cut air pollution. Biden will negotiate fuel economy standards with workers and their unions, environmentalists, industry, and states that achieve new ambition by integrating the most recent advances in technology. This will accelerate the adoption of zero-emissions light- and medium duty vehicles, provide long-term certainty for workers and the industry, and save consumers money through avoided fuel costs. Paired with historic public investments and direct consumer rebates for American-made, American-sourced clean vehicles, these ambitious standards will position America to achieve a net-zero emissions future, and position American auto workers, manufacturers, and consumers to benefit from a clean energy revolution in transport.4

What Is NHTSA’s Authority to Regulate the Fuel The agencies refer to the standards collectively as the National Program. The report looks at the origins of the standards, reviews the current and proposed future regulations, and discusses recent actions and relevant vehicle industry trends. It also examines the relationship between the California and the federal vehicle emissions programs.

What Is NHTSA's Authority to Regulate the Fuel Economy of Motor Vehicles?

Economy of Motor Vehicles? NHTSA derives its authority to regulate the fuel economy of motor vehicles from the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975 (EPCA; P.L. 94-163) as amended by the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 (EISA; P.L. 110-140).1

).5

The origin of federal fuel economy standards dates to the mid-1970s. The oil embargo of 1973-1974 imposed by Arab members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the subsequent tripling in the price of crude oil brought the fuel economy of U.S. automobiles into sharp focus. The fleet-wide fuel economy of new passenger cars had declined

1 §1, Executive Order 13990 of January 20, 2021, “Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science To Tackle the Climate Crisis,” 86 Federal Register 7037-7043, January 25, 2021. 2 Executive Order 13990 of January 20, 2021, “Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science To Tackle the Climate Crisis,” 86 Federal Register 7037-7043, January 25, 2021. 3 §2, Executive Order 13990 of January 20, 2021, “Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science To Tackle the Climate Crisis,” 86 Federal Register 7037-7043, January 25, 2021. 4 Joe Biden, “The Biden Plan to Build a Modern, Sustainable Infrastructure and an Equitable Clean Energy Future,” https://joebiden.com/clean-energy/.

5 49 U.S.C. §§32901-32919.

Congressional Research Service

2

Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards: Frequently Asked Questions

automobiles into sharp focus. The fleet-wide fuel economy of new passenger cars had declined from 15.9 miles per gallon (mpg) in model year (MY) 1965 to 13.0 mpg in MY 1973.26 In an effort to reduce dependence on imported oil, EPCA established CAFE standards for passenger cars beginning in MY 1978 and for light trucks3trucks7 beginning in MY 1979. The standards required each auto manufacturer to meet a target for the sales-weighted fuel economy of its entire fleet of vehicles sold in the United States in each model year. Fuel economy—expressed in miles per gallongallon (mpg)—was defined as the average mileage traveled by a vehicle per gallon of gasoline or equivalent amount of other fuel.

EPCA required NHTSA to establish and amend the CAFE standards; promulgate regulations concerning procedures, definitions, and reports; and enforce the regulations. CAFE standards, and new-vehicle fuel economy, rose steadily through the late 1970s and early 1980s. After 1985, Congress did not revise the legislated standards for passenger cars, and they remained at 27.5 mpg until 2011. The light truck standards were increased to 20.7 mpg in 1996, where they remained until 2005.4

8

New-vehicle fuel economy began to rise again in the mid-2000s, due, in part, to a steady increase in gasoline prices that led many consumers to purchase smaller, more fuel-efficient vehicles. During the George W. Bush Administration, NHTSA promulgated two sets of standards in the mid-2000s affecting the MY 2005-2007 and MY 2008-2011 light truck fleets, increasing their average fuel economy to 24.0 mpg. Further, Congress enacted EISA in 2007, which, among other provisions, revisited the CAFE standards. EISA required NHTSA to increase combined passenger car and light truck fuel economy standards to at least 35 mpg by 2020,59 up from the combined actual passenger car and light truck average of 26.6 mpg in 2007. Along with requiring higher vehicle standards, EISA changed the structure of the program (in part due to concerns about safety and consumer choice).6

10

What Is EPA'’s Authority to Regulate GHG GHG Emissions from Motor Vehicles?

EPA derives its authority to regulate GHG emissions from motor vehicles from the Clean Air Act, as amended (CAA).7

; P.L. 91-604, as amended).11

In 1998, during the Clinton Administration, EPA General Counsel Jonathan Cannon concluded in a memorandum to the agency'’s Administrator that GHGs were air pollutants within the CAA's ’s definition of the term, and therefore could be regulated under the CAA.8 Relying on the Cannon 12 Relying on the Cannon

6 NHTSA, “Historical Passenger Car Fleet Average Characteristics,” https://one.nhtsa.gov/cars/rules/CAFE/HistoricalCarFleet.htm.

7 Light trucks include most passenger sport utility vehicles (SUVs), vans, and pickup trucks. 8 Provisions in the Department of Transportation’s annual appropriations bills between FY1996 and FY2002 prohibited the agency from changing or studying CAFE standards. As reported by National Research Council, Effectiveness and Impact of Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) Standards, Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2002, p. 1.

9 Thirty-five miles per gallon is a lower bound: the Administration is required to set standards at the “maximum feasible” fuel economy level for any model year. 10 See discussion of vehicle “footprint” in the report section entitled “What Were the Standards Under the Obama Administration?” 11 42 U.S.C. §§7401-7626. For a history of the CAA, see CRS Report RL30853, Clean Air Act: A Summary of the Act and Its Major Requirements, by Kate C. Shouse and Richard K. Lattanzio.

12 Memorandum from Jonathan Z. Cannon, EPA General Counsel, to Carol M. Browner, EPA Administrator, “EPA’s Authority to Regulate Pollutants Emitted by Electric Power Generation Sources,” April 10, 1998, at

Congressional Research Service

3

Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards: Frequently Asked Questions

memorandum as well as the statute itself, a group of 19 organizations petitioned EPA on October 20, 1999, to regulate GHG emissions from new motor vehicles under CAA Section 202.913 That section directs the EPA Administrator to develop emissionemissions standards for "“any air pollutant"” from new motor vehicles "“which, in his judgment cause[s], or contribute[s] to air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare."10”14 On August 28, 2003, EPA denied the petition11 because the agencythe George W. Bush Administration’s EPA denied the petition15 because it determined that the CAA does not grant EPA authority to regulate carbon dioxide (CO2CO2) and other GHG emissions based on their climate change impacts.1216 Massachusetts, 11 other states, and various other petitioners challenged EPA'’s denial of the petition in a case that ultimately reached the Supreme Court.13

17

In April 2007, the Supreme Court held that EPA has the authority to regulate GHGs as "air pollutants"“air pollutants” under the CAA.1418 In the 5-4 decision, the Court determined that GHGs fit within the CAA's "unambiguous" and "CAA’s “unambiguous” and “sweeping definition"” of "“air pollutant."15”19 The Court'’s majority concluded that EPA must, therefore, decide whether GHG emissions from new motor vehicles contribute to air pollution that may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare, or provide a reasonable explanation why it cannot or will not make that decision.1620 If EPA madewere to make a finding of endangerment, according to the ruling, the CAA required the agency to establish standards for emissions of the pollutants.17

21

Following the Supreme Court’s decision, Court's decision, the George W. Bush Administration's EPA did not respond in 2008 to the original petition or make a finding regarding endangerment. Its only formal action following the Court decision was to issue a detailed information request, called an Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPR), on July 30, 2008.1822 The Obama Administration'’s EPA, however, made review of the

http://www.law.umaryland.edu/environment/casebook/documents/epaco2memo1.pdf.

13 42 U.S.C. §7521. The lead petitioner was the International Center for Technology Assessment (ICTA). The petition may be found at http://www.ciel.org/Publications/greenhouse_petition_EPA.pdf.

14 42 U.S.C. §7521. 15 EPA, “Control of Emissions from New Highway Vehicles and Engines,” 68 Federal Register 52922, September 8, 2003. The agency argued that it lacked statutory authority to regulate GHGs: Congress “was well aware of the global climate change issue” when it last comprehensively amended the CAA in 1990, according to the agency, but “it declined to adopt a proposed amendment establishing binding emissions limitations.” Massachusetts v. EPA, 549 U.S. 497 (2007).

16 Memorandum from Robert E. Fabricant, Gen. Counsel, EPA, on EPA’s Authority to Impose Mandatory Controls to Address Global Climate Change Under the Clean Air Act, to Marianne L. Horinko, Acting Admin., EPA, August 28, 2003, https://go.usa.gov/xQ4mU.

17 The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (D.C. Circuit), in a split decision, rejected the suit. See Massachusetts v. EPA, 415 F.3d 50, 56, 59-60 (D.C.C. 2005) (Randolph, J., dissenting) (holding that EPA reasonably denied the petition based on scientific uncertainty and policy considerations).

18 Massachusetts v. EPA, 549 U.S. 497, 528-29 (2007). 19 Massachusetts v. EPA, 549 U.S. 497, 528-29 (2007). The majority held that “[t]he Clean Air Act’s sweeping definition of ‘air pollutant’ includes ‘any air pollution agent or combination of such agents, including any physical, chemical ... substance or matter which is emitted into or otherwise enters the ambient air.... ’ ... Carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and hydrofluorocarbons are without a doubt ‘physical [and] chemical ... substances[s] which [are] emitted into ... the ambient air.’ The statute is unambiguous.” Ibid., pp. 528-29.

20 Massachusetts v. EPA, 549 U.S. 497, 528-29, 533 (2007). 21 For further discussion of the Court’s decision, see CRS Report R44807, U.S. Climate Change Regulation and Litigation: Selected Legal Issues, by Linda Tsang.

22 EPA, “Regulating Greenhouse Gas Emissions under the Clean Air Act; Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking,” 73 Federal Register 44354, July 30, 2008. The ANPR occupied 167 pages of the Federal Register. Besides requesting information, it took the unusual approach of presenting statements from the Office of Management and Budget, four Cabinet Departments (Agriculture, Commerce, Transportation, and Energy), the Chairman of the Council on Environmental Quality, the Director of the President’s Office of Science and Technology Policy, the Chairman of the

Congressional Research Service

4

link to page 9

Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards: Frequently Asked Questions

s EPA, however, made review of the endangerment issue a high priority. On December 15, 2009, it promulgated findings that GHGs endanger both public health and welfare, and that GHG emissions from new motor vehicles contribute to that endangerment.19

23

With these findings, the Obama Administration initiated discussions with major stakeholders in the automotive and truck industries and with states and other interested parties to develop and implement vehicle GHG standards. Because CO2 from mobile source fuel combustion is a major source of GHG emissionsCO2 from fuel combustion in the transportation sector is the largest source of GHG emissions (Figure 2), the White House directed EPA to work with NHTSA to align the GHG standards with the CAFE standards.

Figure 2. U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Sector, 2018

Source: EPA, Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2018, April 13, 2020. Note: Total GHG emissions in 2018 equaled 6,677 mil ion metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent.

In addition, the CAA grants the state of California unique status to receive a waiver to issue motor vehicle emissionemissions standards, provided that they are at least as stringent as federal ones and are necessary to meet "“compelling and extraordinary conditions."” California had already promulgated GHG emissions standards prior to 2009, for which it had requested an EPA waiver under provisions in the CAA. EPA granted California a waiver in July 2009, and President Obama Council of Economic Advisers, and the Chief Counsel for Advocacy at the Small Business Administration, each of whom expressed their objections to regulating GHG emissions under the CAA. The 2008 OMB statement began by noting, “The issues raised during interagency review are so significant that we have been unable to reach interagency consensus in a timely way, and as a result, this staff draft cannot be considered Administration policy or representative of the views of the Administration.” 73 Federal Register 44356. It went on to state that “the Clean Air Act is a deeply flawed and unsuitable vehicle for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.” Other letters submitted to the regulatory docket concurred.

23 EPA, “Endangerment and Cause or Contribute Findings for Greenhouse Gases under Section 202(a) of the Clean Air Act; Final Rule,” 74 Federal Register 66496, December 15, 2009. Although generally referred to as simply “the endangerment finding,” the EPA Administrator actually finalized two separate findings: a finding that six greenhouse gases endanger public health and welfare, and a separate “cause or contribute” finding that the combined emissions of greenhouse gases from new motor vehicles and new motor vehicle engines contribute to the greenhouse gas pollution that endangers public health and welfare. Throughout the report, GHGs are quantified using a unit measurement called CO2 equivalent (CO2e), wherein each different GHG is indexed and aggregated against one unit of CO2 based on their Global Warming Potential (GWP).

Congressional Research Service

5

Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards: Frequently Asked Questions

directed EPA and NHTSA to align the federal fuel economy and GHG emissions standards with those developed by California. The Administration referred to the coordinated effort as the National Program.24

What Is California’s Authority to Regulate GHG Emissions from Motor Vehicles?25 The California Air Resources Board (CARB) derives its authority to regulate GHG emissions from motor vehicles from California Assembly Bill (AB) 1493.26

provisions in the CAA. EPA granted California a waiver in July 2009, and President Obama directed EPA and NHTSA to align the federal fuel economy and GHG emission standards with those developed by California. The Administration referred to the coordinated effort as the National Program.

EPA and NHTSA promulgated joint rulemakings affecting MY 2012-2016 light-duty motor vehicles on May 7, 2010. These are known as the Phase 1 standards.20

What Is California's Authority to Regulate GHG Emissions from Motor Vehicles?21

The California Air Resources Board (CARB) derives its authority to regulate GHG emissions from motor vehicles from California Assembly Bill (AB) 1493.22

Questions of federal preemption of state regulations can arise when state law operates in an area that may also be of concern to the federal government. Under the Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution,23 state law that conflicts with federal law must yield to the exercise of Congress's powers.24 When it acts, Congress can preempt state laws or regulations within a field entirely, preempt only state laws or regulations that conflict with federal law, or allow states to act freely.25

or seek a waiver from preemption.27 Title II of the CAA generally preempts states from adopting their own emission emissions standards for new motor vehicles or engines.2628 However, CAA Section 209(b) provides an exception to federal preemption of state vehicle emissionemissions standards:

The [EPA] Administrator shall, after notice and opportunity for public hearing, standards:

The [EPA] Administrator shall, after notice and opportunity for public hearing, waive application of this section [the preemption of State emission standards] to any State which has adopted standards (other than crankcase emission standards) for the control of has adopted standards (other than crankcase emission standards) for the control of emissions from new motor vehicles or new motor vehicle engines prior to March 30, 1966, if the State determines that the State standards will be, in the aggregate, at least as protective of public health and welfare as applicable Federal standards.27

29

Only California can qualify for such a preemption waiver because it is the only state that adopted motor vehicle emissionemissions standards "“prior to March 30, 1966."28”30 According to EPA records, since 1967, CARB has submitted over 100 waiver requests for new or amended standards or "“within the scope"” determinations (i.e., a request that EPA rule on whether a new state regulation is within the scope of a waiver that EPA has already issued).29

31

On July 22, 2002, California became the first state to enact legislation requiring reductions of GHG emissions from motor vehicles. The legislation, AB 1493, required CARB to adopt

24 Since 2009, the agencies and stakeholder groups have referred to the coordinated program as both the One National Program and the National Program. This report uses the latter term throughout.

25 EPCA preempts states from adopting or enforcing laws “related to” fuel economy standards for automobiles covered by federal standards. 49 U.S.C. §32919. The issue of whether EPCA could preempt state motor vehicle GHG emissions standards is beyond the scope of this report.

26 2002 CAL. STAT. ch. 200 (codified at CAL. HEALTH & SAFETY CODE § 43018.5). 27 Gade v. Nat’l Solid Wastes Mgmt. Assn., 505 U.S. 88, 98 (1992). Congress can disavow an intent to preempt certain categories of state law by including a “savings clause” to that effect in federal statutes, see, e.g., 29 U.S.C. §1144(b), or by allowing federal administrative agencies to grant “preemption waivers” to states in certain circumstances, see 42 U.S.C. §7543(b).

28 CAA §209(a), 42 U.S.C. §7543(a). See also S.Rept. 91-1196, at 32 (1970). 29 The CAA places three conditions on the grant of such waivers: The Administrator is to deny a waiver if he finds (1) that the state’s determination is arbitrary and capricious; (2) that the state does not need separate standards to meet compelling and extraordinary conditions; or (3) that the state’s standards and accompanying enforcement procedures are not consistent with §202(a) of the act. 42 U.S.C. §7543(b)(1)(A)-(C).

30 S.Rept. 90-403, at 33 (1990). 31 See EPA, Vehicle Emissions California Waivers and Authorizations, https://www.epa.gov/state-and-local-transportation/vehicle-emissions-california-waivers-and-authorizations#state (listing Federal Register notices of waiver requests and decisions); Letter from Kevin de Leon, President pro Tempore, Cal. Senate, et. al., to Xavier Becerra, Att’y Gen., Cal. Dep’t of Justice, March 16, 2017.

Congressional Research Service

6

Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards: Frequently Asked Questions

GHG emissions from motor vehicles. The legislation, AB 1493, required CARB to adopt regulations requiring the "“maximum feasible and cost-effective reduction"” of GHG emissions from any vehicle whose primary use is noncommercial personal transportation.3032 The reductions applied to motor vehicles manufactured in MY 2009 and thereafter. Under this authority, CARB adopted regulations on September 24, 2004, and submitted a request to EPA on December 21, 2005, for a preemption waiver.

In 2008, EPA denied California'’s request for a waiver.3133 As explained in its decision, EPA concluded that "“California does not need its GHG standards for new motor vehicles to meet compelling and extraordinary conditions"” because "“the atmospheric concentrations of these greenhouse gases is [sic] basically uniform across the globe"” and are not uniquely connected to California's "California’s “peculiar local conditions."32”34 However, under the Obama Administration, EPA reconsidered and reversed the denial, and granted the waiver in 2009.3335 In reversing its denial, EPA determined that it is the "“better approach"” for the agency to evaluate whether California "needs"“needs” state standards "“to meet compelling and extraordinary conditions"” based on California's ’s need for its motor vehicle program as a whole, and not solely based on GHG standards addressed in the waiver request.3436 Under this approach, EPA concluded that it cannot deny the waiver request because California has "repeatedly"“repeatedly” demonstrated the need for its motor vehicle problem program to address "serious"“serious” local and regional air pollution problems.35

37

Upon receiving the waiver, CARB joined EPA and NHTSA to develop the National Program under the Obama Administration. Three key provisions of the 2009 agreement between the Administration, the auto manufacturers, and the State of California were (1) that EPA would grant California the waiver for MYs 2017-2025 (the agency did so on January 9, 2013),3638 (2) that California would accept vehicles complying with the federal greenhouse standards as meeting the California standards,37 and39 and (3) that the auto manufacturers would drop their suit against the California standards.

Additionally, the CAA allows other states to adopt California's motor vehicle emission standards

32 The legislation required that CARB standards achieve “the maximum feasible and cost-effective reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from motor vehicles” while accounting for “environmental, economic, social, and technological factors.” 33 EPA, “California State Motor Vehicle Pollution Control Standards; Notice of Decision Denying a Waiver of Clean Air Act Preemption for California’s 2009 and Subsequent Model Year Greenhouse Gas Emissions,” 73 Federal Register 12156, March 6, 2008.

34 Ibid., pp. 12159-69. 35 EPA, “California State Motor Vehicle Pollution Control Standards; Notice of Decision Granting a Waiver of Clean Air Act Preemption for California’s 2009 and Subsequent Model Year Greenhouse Gas Emission Standards for New Motor Vehicles,” 74 Federal Register 32744, July 8, 2009. 36 Ibid., pp. 32761-63. 37 Ibid., pp. 32762-63. 38 EPA, “California State Motor Vehicle Pollution Control Standards; Notice of Decision Granting a Waiver of Clean Air Act Preemption for California’s Advanced Clean Car Program and a Within the Scope Confirmation for California’s Zero Emission Vehicle Amendments for 2017 and Earlier Model Years,” 78 Federal Register 2112, January 9, 2013.

39 Mary D. Nichols, Chairman, CARB, “Letter to Ray LaHood, Secretary, U.S. Department of Transportation, and Lisa Jackson, Administrator, Environmental Protection Agency,” July 28, 2011, https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-10/documents/carb-commitment-ltr.pdf. The condition set forth by CARB was that the “deemed to comply” provision was contingent upon the U.S. EPA adopting “a final rule that at a minimum preserves the greenhouse reduction benefits set forth in U.S. EPA’s December 1, 2011 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking for 2017 through 2025 model year passenger vehicles.” CARB Resolution 12-11, January 26, 2012, p. 20.

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 12 link to page 26

Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards: Frequently Asked Questions

Additionally, the CAA allows other states to adopt California’s motor vehicle emissions standards under certain conditions.40under certain conditions.38 Section 177 requires, among other things, that such standards be identical to the California standards for which a waiver has been granted. States are not required to seek EPA approval under the terms of Section 177. ThirteenFourteen other states and the District of Columbia have adopted California'’s GHG standards under these provisions, bringing approximately 35provisions (Figure 3), and three states are considering them,41 which would bring nearly 40% of domestic automotive sales registrations under the California program.39

What Are the Current CAFE and GHG Standards?

NHTSA and EPA promulgated the second (current)42

Figure 3. State Adoption of California’s GHG Standards

States Using or Considering the Use of Clean Air Act Section 177

Source: CRS. Note: Map is based on state legislative action through June 1, 2021.

40 42 U.S.C. §7507. 41 See Proposed Permanent Rules Relating to Clean Cars; Notice of Intent to Adopt Rules with a Hearing, 45 Minn. Reg. 663 (Dec. 21, 2020); Clean Cars Nevada, NEV. DIV. OF ENV’T. PROT., https://ndep.nv.gov/air/clean-cars-nevada (last visited Jan. 27, 2021); Exec. Order 2019-003, Executive Order on Addressing Climate Change and Energy Waste Prevention, New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham (Jan. 29, 2020), https://www.governor.state.nm.us/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/EO_2019-003.pdf.

42 New York, Massachusetts, Vermont, Maine, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Washington, Maryland, Oregon, New Jersey, Delaware, Colorado, Virginia, and the District of Columbia. Footnote 112 below lists the state laws or other actions that have adopted California’s GHG standards. Total light vehicle registrations in these states and the District of Columbia—passenger cars, vans, SUVs, and pickup trucks—comprise 36% of all U.S. light vehicle registrations in 2019. Wards Intelligence Data Center, “U.S Total Vehicle Registrations by State by Vehicle Type, 2019,” viewed April 22, 2021. Minnesota, Nevada, and New Mexico are considering adopting California’s vehicle GHG standards; if they do so, 39.9% of all U.S. vehicles will be registered in §177 states. According to the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Economic Analysis and the U.S. Census Bureau, respectively, these 17 states and the District of Columbia represented 49% of U.S. gross domestic product and an estimated 42% of U.S. population in 2020.

Congressional Research Service

8

link to page 21 link to page 14 Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards: Frequently Asked Questions

EPA revoked California’s waiver to regulate vehicle GHG emissions in 2020. In April 2021, EPA announced that it is reconsidering the withdrawal of the waiver. For more detail, see the report section entitled “The Final SAFE Vehicles Rule, Part One.”

What Were the Standards Under the Obama Administration? EPA and NHTSA promulgated joint rulemakings affecting MY 2012-2016 light-duty motor vehicles on May 7, 2010. These are known as the Phase 1 standards.43 The agencies promulgated a second phase of CAFE and GHG emissions standards affecting MY 2017-2025 light-duty vehicles on October 15, 2012.40 Like the44 The Phase 1 standards,and the Phase 2 standards were preceded by a multiparty agreementagreements, brokered by the Obama White House. The Phase 2 agreement involved, involving the State of California, 13 auto manufacturers, and the United Auto Workers union. The For the Phase 2 standards, the auto manufacturers agreed to reduce GHG emissions from new passenger cars and light trucks by about 50% by 2025, compared to 2010, with fleet-wide average fuel economy rising to nearly 50 miles per gallon. GHG emissions wouldwere projected to be reduced to about 160 grams per mile by 2025 under the agreementPhase 2 standards (see Table 1).41

45

The standards are applicable to the fleet of new passenger cars and light trucks with gross vehicle weight rating less than or equal to 10,000 pounds sold within the United States in each model year. Fuel economy and carbon-related emissions are tested over EPA'’s two test cycles (the Federal Test Procedure ([FTP-75)], weighted at 55%; and the Highway Fuel Economy Test (HWFET)[HWFET], weighted at 45%).4246 In addition to the standards for fleet-average fuel economy and GHG emissions (measured and referred to as "CO2“CO2-equivalent emissions"” under the regulations),4347 the rule also includes emissionemissions caps for tailpipe nitrous oxide emissions (0.010 grams/mile) and methane emissions (0.030 grams/mile).

The Phase 1 and Phase 2 standards use the concept of a vehicle’s “footprint” to set differing targets for different size vehicles.48 These “size-based,” or “attribute-based,” standards were

43 EPA, “Light-Duty Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emission Standards and Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards; Final Rule,” 75 Federal Register 25324, May 7, 2010.

44 EPA and NHTSA, “2017 and Later Model Year Light-Duty Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards; Final Rule,” 77 Federal Register 62624, October 15, 2012. 45 EPA and NHTSA, “2017-2025 Model Year Light-Duty Vehicle GHG Emissions and CAFE Standards: Supplemental Notice of Intent,” 76 Federal Register 48758, August 9, 2011. The auto manufacturers’ and CARB’s letters of support can be found at https://www.epa.gov/regulations-emissions-vehicles-and-engines/2011-commitment-letters-2017-2025-light-duty-national.

46 The Federal Test Procedure (FTP-75) and Highway Fuel Economy Test (HWFET) are chassis dynamometer driving schedules developed by EPA for the determination of fuel economy of light-duty vehicles during city driving and highway driving conditions, respectively (40 C.F.R. pt. 600, subpt. B). EPA also requires the US06 (high acceleration), SC03 (with air conditioning), and cold temperature FTP driving schedules for GHG emissions testing.

47 Although CO2 is the primary GHG, other gases, such as methane (CH4) and fluorinated gases (e.g., air conditioner refrigerants), also act as GHGs. The calculations of the weighted fuel economy and carbon-related exhaust emissions values are provided for in 40 C.F.R. §600.113-12, and require input of the weighted grams/mile values for CO2, total hydrocarbons (HC), carbon monoxide (CO), and, where applicable methanol (CH3OH), formaldehyde (HCHO), ethanol (C2H5OH), acetaldehyde (C2H4O), nitrous oxide (N2O), and methane (CH4). Reductions in other (i.e., nontailpipe) GHG emissions are captured in adjustments made to the compliance standards based on the manufacturer’s use of flex-fuel vehicle, air-conditioning, “off-cycle,” and CH4 and N2O deficit credits. 48 Footprint is defined as the product of a vehicle’s wheelbase and average track width, in square feet. 40 C.F.R. §86.1803-01. The “attribute-based” standards were first introduced in the reformed CAFE program for MY 2008-2011

Congressional Research Service

9

Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards: Frequently Asked Questions

structurally different from the original CAFE program, which grouped domestic passenger cars, imported passenger cars, and light trucks into three broad categories.49 Generally, the larger the vehicle footprint (in square feet), the lower the corresponding vehicle fuel economy target and the higher the CO2-equivalent emissions target. This allowed auto manufacturers to produce a full range of vehicle sizes as opposed to focusing on light-weighting and downsizing50 the entire fleet in order to meet the categorical targets. Nevertheless, the fuel economy and GHG emissions targets grew more stringent each year across all vehicle footprints.

Upon the rulemaking, the agencies expected that the technologies available for auto manufacturers to meet the MY 2017-2025 standards would include advanced gasoline engines and transmissions, vehicle weight reduction, lower tire rolling resistance, improvements in aerodynamics, diesel engines, more efficient accessories, and improvements in air conditioning systems. Some increased electrification of the fleet was also expected through the expanded use of stop/start systems, hybrid vehicles, plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, and electric vehicles.

Table 1. Phase 2 MY 2017-2025 Combined Average Passenger Car and Light Truck

CAFE and GHG Emission Standards

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

2023

2024

2025

GHG Standard (grams per mile)

243

232

222

213

199

190

180

171

163

grams/mile) and methane emissions (0.030 grams/mile).

|

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

GHG Standard (grams per mile) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

GHG-Equivalent Fuel Economy (miles per gallon

36.6

38.3

40.0

41.7

44.7

46.8

49.4

52.0

54.5

equivalent)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Fuel Economy (CAFE) Standard

35.4

36.5

37.7

38.9

41.0

43.0

45.1

47.4

49.7

(miles per gallon)

Source: CRS, from EPA and NHTSA, “ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: CRS, from EPA and NHTSA, "2017 and Later Model Year Light-Duty Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards,"” 77 Federal Register 62624, October 15, 2012.

Notes: The values are based on projected sales of vehicles in different size classes. The standards are size-based, and the vehicle fleet encompasses large, medium, and small cars and light trucks. Thus if the sales mix is different from projections, the achieved CAFE and GHG levels would rise or fall. For example, CAFE numbers are based on NHTSA'’s projection using the MY 2008 fleet as the baseline. A different projection, based on the MY 2010 fleet, leads to somewhat lower numbers (roughly 0.3—-0.6 mpg lower for MYs 2017-2020 and roughly 0.7-1.0 mpg lower for MY 2021 onward). As discussed later, types of vehicles sold domestically has changed during the past decade.

GHG-Equivalent Fuel Economy (miles per gallon equivalent) is the value returned if all of the GHG reductions were made through fuel economy improvements. However, in practice, other strategies are used to reduce GHG emissions to the actual GHG standard (for example, improved vehicle air conditioners).

CAFE standards for MYs 2022-2025 are italicized because they are non-final (or "augural"were nonfinal (or “augural”). NHTSA has authority to set CAFE standards only in five-year increments. Thus, only rules through MY 2021 have been finalizedunder Phase 2, NHTSA finalized standards through MY 2021. To set standards for MY 2022 onward, NHTSA haswas required to issue a new rule.

light trucks. NHTSA, “Average Fuel Economy Standards for Light Trucks; Model Years 2008-2011: Proposed Rule,” 70 Federal Register 51413, August 30, 2005.

49 The definitions of passenger car, light truck, and import can be found at 49 C.F.R. Part 523. 50 Light-weighting refers to using lighter weight structural materials to reduce the mass of the vehicle in order to increase fuel efficiency, and downsizing refers to designing smaller engines that run at higher loads in order to increase fuel efficiency.

Congressional Research Service

10

link to page 31 link to page 31 Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards: Frequently Asked Questions

What Does a “Standard of 54.5 MPG in MY 2025” Mean?

The 54.5 number was not a requirement for every—or for any specific—vehicle or manufacturer; it was an estimate of what the agencies acting in 2012 to issue a new rule.

As with the Phase 1 standards, the agencies used the concept of a vehicle's "footprint" to set differing targets for different size vehicles.44 These "size-based," or "attribute-based," standards were structurally different than the original CAFE program, which grouped domestic passenger cars, imported passenger cars, and light trucks into three broad categories.45 Generally, the larger the vehicle footprint (in square feet), the lower the corresponding vehicle fuel economy target and the higher the CO2-equivalent emissions target. This allowed auto manufacturers to produce a full range of vehicle sizes as opposed to focusing on light-weighting and downsizing46 the entire fleet in order to meet the categorical targets.

Upon the rulemaking, the agencies expected that the technologies available for auto manufacturers to meet the MY 2017-2025 standards would include advanced gasoline engines and transmissions, vehicle weight reduction, lower tire rolling resistance, improvements in aerodynamics, diesel engines, more efficient accessories, and improvements in air conditioning systems. Some increased electrification of the fleet was also expected through the expanded use of stop/start systems, hybrid vehicles, plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, and electric vehicles.

What Does a "Standard of 54.5 MPG in MY 2025" Mean?

|

How Do Manufacturers Comply with the Standards?

Manufacturers comply with the standards by reporting to EPA and NHTSA annually with information regarding their MY fleet production and sales numbers, their MY fleet characteristics, and the fuel economy and emissions results from the EPA-approved test cycles. This information allows the agencies to calculate each manufacturer's specific CAFE and GHG emissions standards given its fleet-wide sales numbers. The agencies compare the calculated standard against the manufacturer's fleet-wide adjusted test results to determine compliance. Accordingly, compliance is based on the vehicles sold, not the vehicles produced. Figure 1 compares CAFE standards, as promulgated for both passenger cars and light trucks over MYs 1978-2025, against the U.S. fleets' adjusted performance data as reported by NHTSA for the given MYs. Table 2 lists the most recent adjusted performance data reported by the agencies—MY 2017—for each manufacturer and its fleets.

Because of the "attribute-based" standards, compliance targets are different for each manufacturer depending on the vehicles it produces. As stated by NHTSA: "Manufacturers are not compelled to build light-duty vehicles of any particular size or type, and each manufacturer will have its own standard which reflects the vehicles it chooses to produce."48 The agencies contend: "Under the National Program automobile manufacturers will be able to continue building a single light-duty national fleet that satisfies all requirements under both programs while ensuring that consumers still have a full range of vehicle choices that are available today."49

To facilitate compliance, the agencies provide manufacturers various flexibilities under the standards. A manufacturer's fleet-wide performance (as measured on EPA's test cycles) can be adjusted through the use of flex-fuel vehicles, air-conditioning efficiency improvements, and other "off-cycle" technologies (e.g., active aerodynamics, thermal controls, and idle reduction).50 Further, manufacturers can generate credits for overcompliance with the standards in a given year. They can bank, borrow, trade, and transfer these credits, both within their own fleets and among other manufacturers, to facilitate current compliance. They can also offset current deficits using future credits (either generated or acquired within three years) to determine final compliance.51 A CAFE credit is earned for each 0.1 mpg in excess of the fleet's standard mpg. A GHG credit is earned for each megagram (Mg, or metric ton) of CO2-equivalent saved relative to the standard as calculated for the projected lifetime of the vehicle. Table 3 summarizes GHG credits that are available to each manufacturer after MY 2017, reflecting all completed trades and transfers, as reported by EPA. (NHTSA's CAFE credit balances for MY 2017 have not been reported.)

The auto manufactures completed MY 2017 compliance with approximately 250 million metric tons of GHG credits under EPA's program. Many manufacturers chose to use credits for MY 2017 compliance. It was the second consecutive model year that the manufacturers depleted total industry credits after four years of the industry accumulating credits (see Figure 2). In addition to the industry-wide credit balance, factors that may affect future compliance include credit expiration and distribution. Credits earned by manufacturers in MY 2017 or beyond have a five-year lifespan, while all prior credits (92% of the total) are to expire at the end of MY 2021. Additionally, three manufacturers hold more than half of the current balance.52

Under the CAFE program, manufacturers can comply with the standards by paying a civil penalty. The CAFE penalty is currently $5.50 per 0.1 mpg over the standard, per vehicle.53 Historically, some manufacturers have opted to comply with the standards in this way, especially low volume, luxury imported vehicles.54 Beginning with MY 2019, NHTSA was scheduled to assess a civil penalty of $14 per 0.1 mpg over the standard as provided by the Federal Civil Penalties Inflation Adjustment Act Improvements Act of 2015 within the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-74) and subsequent rulemaking.55 On August 26, 2019, NHTSA finalized a rule to retain the existing penalty rate of $5.50 applicable to automobile manufacturers that fail to meet CAFE standards, having proposed that increasing the CAFE civil penalty rate would have a negative economic impact. The rule is to be effective as of September 24, 2019.56

Under the CAA, manufacturers that fail to comply with the GHG emissions standards are also subject to civil enforcement. The EPA Administer and the U.S. Attorney General determine the amount of the civil penalty based on numerous factors, but it could be as high as $37,500 per vehicle per violation.57 As of MY 2015, EPA has not determined any manufacturer to be out of compliance with the light-duty vehicle GHG emissions standards.

Table 2. MY 2017 Manufacturer Fuel Economy and GHG Values

(Data are projected. Italicized values show performance data that do not meet the standards after the two-cycle test and adjustments but before the manufacturer's use of compliance flexibilities.)

|

Manufacturer |

Fleet |

CAFE Standard (mpg) |

CAFE Performance (mpg) |

GHG Standard (g/m) |

GHG Performance (g/m) |

|

BMW |

IPC |

38.5 |

35.1 |

221 |

223 |

|

LT |

30.6 |

28.9 |

284 |

278 |

|

|

Daimler/Mercedes |

DPC |

38.1 |

36.9 |

229 |

255 |

|

IPC |

36.8 |

32.4 |

|||

|

LT |

29.9 |

26.4 |

290 |

326 |

|

|

Fiat Chrysler * |

DPC |

37.3 |

32.0 |

225 |

267 |

|

IPC |

40.0 |

33.5 |

|||

|

LT |

29.1 |

27.6 |

297 |

315 |

|

|

Ford |

DPC |

38.5 |

36.2 |

222 |

237 |

|

IPC |

40.8 |

75.8 |

|||

|

LT |

28.2 |

27.1 |

308 |

322 |

|

|

GM |

DPC |

38.1 |

37.8 |

221 |

213 |

|

IPC |

41.9 |

43.7 |

|||

|

LT |

27.5 |

25.8 |

315 |

333 |

|

|

Honda |

DPC |

39.1 |

43.1 |

217 |

196 |

|

IPC |

41.2 |

46.4 |

|||

|

LT |

30.9 |

32.8 |

279 |

253 |

|

|

Hyundai |

IPC |

38.9 |

38.8 |

219 |

230 |

|

LT |

31.2 |

27.1 |

278 |

327 |

|

|

Jaguar Land Rover |

IPC |

37.0 |

31.7 |

244 |

267 |

|

LT |

30.4 |

27.5 |

287 |

310 |

|

|

Kia |

DPC |

39.5 |

44.7 |

218 |

219 |

|

IPC |

38.9 |

37.6 |

|||

|

LT |

31.0 |

28.5 |

281 |

308 |

|

|

Mazda |

DPC |

39.8 |

42.7 |

216 |

222 |

|

IPC |

39.1 |

39.0 |

|||

|

LT |

32.3 |

33.9 |

268 |

263 |

|

|

Mitsubishi |

IPC |

42.4 |

44.4 |

217 |

214 |

|

LT |

34.2 |

34.6 |

286 |

294 |

|

|

Nissan |

DPC |

39.2 |

40.8 |

217 |

214 |

|

IPC |

39.0 |

36.3 |

|||

|

LT |

30.1 |

29.1 |

286 |

294 |

|

|

Subaru |

IPC |

39.7 |

38.2 |

213 |

236 |

|

LT |

33.6 |

36.8 |

258 |

230 |

|

|

Tesla |

DPC |

33.4 |

370.5 |

252 |

-266 |

|

Toyota |

DPC |

38.6 |

38.3 |

216 |

208 |

|

IPC |

40.0 |

42.5 |

|||

|

LT |

29.9 |

28.8 |

290 |

305 |

|

|

Volkswagen * |

DPC |

38.5 |

36.7 |

213 |

234 |

|

IPC |

38.2 |

36.8 |

|||

|

LT |

27.3 |

27.6 |

282 |

301 |

|

|

Volvo |

IPC |

37.4 |

35.9 |

241 |

236 |

|

LT |

30.2 |

30.9 |

288 |

265 |

Source: CRS, from NHTSA, "Manufacturer Projected Fuel Economy Performance Report," April 30, 2018, Table 1; EPA, "The 2018 EPA Automotive Trends Report: Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Fuel Economy, and Technology Since 1975," March 2019, Tables 5.1, 5.7, and 5.9.

Notes: CAFE values in miles per gallon (mpg); GHG values in grams per mile (g/m). CAFE compliance is divided into three fleets: domestic passenger cars (DPC), import passenger cars (IPC), and light trucks (LT); GHG compliance is divided into two fleets: passenger cars and light trucks. CAFE and GHG performance values are after fleet adjustments but before credit banking, borrowing, trading, or transferring by manufacturer. A higher CAFE performance value than CAFE standard value is in compliance; a lower GHG performance value than GHG standard value is in compliance. Values listed in italics show performance data that do not meet the standards after the 2-cycle test and adjustments, but before the manufacturer's use of compliance flexibilities. Manufacturers may be in compliance for one program but out of compliance for the other due to the classification of fleets and the differences in the programs' adjustments.

Nissan and Mitsubishi are listed as separate companies in NHTSA's report and a single company in EPA's report.

* Fiat Chrysler and Volkswagen are under ongoing investigations and/or corrective actions. Investigations and corrective actions may yield different final data.

|

Manufacturer |

Total Credits Carried Forward to MY 2018 (Metric Tons) |

||

|

Toyota |

71,407,230 |

||

|

Honda |

37,813,391 |

||

|

Nissan/Mitsubishi |

28,069,044 |

||

|

Fiat Chrysler * |

20,307,365 |

||

|

Hyundai |

18,086,030 |

||

|

Subaru |

16,865,474 |

||

|

Ford |

16,263,750 |

||

|

GM |

15,082,239 |

||

|

Mazda |

9,294,662 |

||

|

BMW |

5,276,410 |

||

|

Kia |

4,942,038 |

||

|

Volkswagen * |

2,776,936 |

||

|

Tesla |

2,385,617 |

||

|

Daimler/Mercedes |

573,455 |

||

|

Suzuki |

428,242 |

||

|

Volvo |

264,235 |

||

|

Karma Automotive |

58,852 |

||

|

BYD Motors |

5,401 |

||

|

Jaguar Land Rover |

-575,167 |

||

Source: CRS, from EPA, "The 2018 EPA Automotive Trends Report: Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Fuel Economy, and Technology Since 1975," March 2019, Table 5.17.

Notes: A GHG credit is earned for each megagram (Mg, or metric ton) of CO2-equivalent saved relative to the standard as calculated for the projected lifetime of the vehicle. EPA estimates the lifetime of a passenger car to be 14 years and the lifetime of a light truck to be 16 years. Accordingly, outstanding credits for all manufacturers carried forward to MY2018 are equivalent to 249 million metric tons CO2-equivalent saved. For comparison, CO2-equivalent emissions from all on-road passenger cars and light trucks in the United States in 2017 were 1,054 million metric tons (EPA, "Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks 1990-2017," April 11, 2019, Table 3-13).

Some companies on the list produced no vehicles for the U.S. market in the most recent model year, but the credits generated in previous model years continue to be available. Manufacturers can offset current deficits using future credits (either generated or acquired within three years) to determine final compliance.

* Fiat Chrysler and Volkswagen are under ongoing investigations and/or corrective actions. Investigations and corrective actions may yield different final data.

What Is the Midterm Evaluation?

As part of the Phase 2 rulemaking, EPA and NHTSA made a commitment to conduct a midterm evaluation (MTE) for the latter half of the standards, MYs 2022-2025.58 The agencies deemed an MTE appropriate given the long time frame during which the standards were to apply and the uncertainty about how motor vehicle technologies would evolve. EPA, NHTSA, and California also have differing statutory obligations. That is, EPA, California, and some other states—through their authorities under the CAA, California AB 1493, and other state statutes—have finalized GHG emissions standards through MY 2025. Under the MTE, EPA and CARB were to decide whether to revise their standards. NHTSA, through its authorities under EPCA, has finalized standards only through MY 2021, and would require new rulemaking for the period MYs 2022-2025.

Through the MTE, the EPA Administrator was to determine whether EPA's standards for MYs 2022-2025 were still appropriate given the latest available data and information.59 A final determination could result in strengthening, weakening, or retaining the current standards. If EPA determined that the standards were appropriate, the agency would "announce that final decision and the basis for that decision." If EPA determined that the standards should be changed, EPA and NHTSA would be required to "initiate a rulemaking to adopt standards that are appropriate." Throughout the process, the MY 2022-2025 standards were to "remain in effect unless and until EPA changes them by rulemaking."

The Phase 2 rulemaking laid out several formal steps in the MTE process, including

- a Draft Technical Assessment Report issued jointly by EPA, NHTSA, and CARB with opportunity for public comment no later than November 15, 2017;

- a Proposed Determination on the MTE, with opportunity for public comment; and

- a Final Determination, no later than April 1, 2018.

EPA, NHTSA, and CARB jointly issued the Draft Technical Assessment Report for public comment on July 27, 2016.60 This was a technical report, not a decision document, and examined a wide range of technology, marketplace, and economic issues relevant to the MY 2022-2025 standards. It found

- auto manufacturers are innovating in a time of record sales and fuel economy levels;

- the MY 2022-2025 standards could be met largely with more efficient gasoline-powered cars and with only modest penetration of hybrids and electric vehicles; and

- the "attribute-based" standards preserve consumer choice, even as they protect the environment and reduce fuel consumption.

On November 30, 2016, the Obama Administration's EPA released a proposed determination stating that the MY 2022-2025 standards remained appropriate and that a rulemaking to change them was not warranted.61 The agency based its findings on a Technical Support Document,62 the previously released Draft Technical Assessment Report, and input from the auto industry and other stakeholders. On January 12, 2017, then-EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy finalized the determination, stating that "the standards adopted in 2012 by the EPA remain feasible, practical and appropriate."63

The final action arguably accelerated the timeline for the MTE, and EPA announced it separately from any NHTSA or CARB announcement. EPA noted its "discretion" in issuing a final determination, saying that the agency "recognizes that long-term regulatory certainty and stability are important for the automotive industry and will contribute to the continued success of the national program."64

Some auto manufacturer associations and other industry groups criticized the results of EPA's review and reportedly vowed to work with the Trump Administration to revisit EPA's determination. These groups sought actions such as easing the MY 2022-2025 requirements and/or better aligning NHTSA's and EPA's standards.

What Is the Status of CAFE and GHG Standards Under the Trump Administration?

The Revised Final Determination

The Revised Final Determination On March 15, 2017, after President Trump took office, EPA and NHTSA announced their joint intention to reconsider the Obama Administration'’s final determination and reopen the midterm evaluation process. EPA announced a 45-day public comment period on August 21, 2017, and held a public hearing on September 6, 2017, receiving more than 290,000 comments.65

63

On April 2, 2018, EPA released a revised final determination, stating that the MY 2022-2025 standards are "were “not appropriate and, therefore, should be revised."66”64 The notice statesstated that the January 2017 final determination iswas based on "“outdated information, and that more recent information suggestssuggested that the current standards may bewere too stringent."” In making the revised determination, then-EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt cited and provided comment on several factors from the Phase 2 rulemaking that governed analysis for the midterm evaluation process. These factors include67

- included65 the availability and effectiveness of technology, and the appropriate lead time for introduction of technology;

-

63 EPA, “News Release: EPA to Reexamine Emission Standards for Cars and Light-Duty Trucks—Model Years 2022-2025,” March 15, 2017, https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/epa-reexamine-emission-standards-cars-and-light-duty-trucks-model-years-2022-2025.

64 EPA, “Mid-Term Evaluation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions Standards for Model Year 2022-2025 Light-Duty Vehicles: Notice; Withdrawal,” 83 Federal Register 16077, April 13, 2018. 65 These factors are listed at 40 C.F.R. §86.1818-12(h)(1).

Congressional Research Service

14

link to page 20 Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards: Frequently Asked Questions

the cost to the producers or purchasers of new motor vehicles or new motor

the cost to the producers or purchasers of new motor vehicles or new motor vehicle engines; - vehicle engines; the feasibility and practicability of the standards;

- the impact of the standards on emissions reduction, oil conservation, energy security, and fuel savings by consumers;

-

the impact of the standards on the automobile industry;

- the impact of the standards on automobile safety;

- the impact of the GHG emissions standards on the CAFE standards and a national harmonized program; and

- the impact of the standards on other relevant factors.

The revised final determination statesstated that EPA and NHTSA would initiate a new rulemaking to consider revised standards for MY 2022-2025 vehicles.6866 Until that new rulemaking is was completed, the currentPhase 2 standards remainremained in effect.

The Proposed SAFE Rule

Vehicles Rule On August 24, 2018, EPA and NHTSA proposed amendments to the existing CAFE and GHG emissionemissions standards. The Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient Vehicles Rule for MY 2021-2026 Passenger Cars and Light Trucks (SAFE Vehicles Rule) offersoffered eight alternatives (seesee Table 42).69 67 The agencies'’ preferred alternative, if finalized, is was to retain the existing standards through MY 2020 and then to freeze them at the MY 2020 levelto freeze the standards at this level for both programs through MY 2026. The preferred alternative also removes CO2 removed the nontailpipe, GHG-exclusive requirements for CO2-equivalent air conditioning refrigerant leakage, nitrous oxide, and methane requirements after MY 2020.

Further, EPA proposesproposed to withdraw California'’s CAA preemption waiver for its vehicle GHG standards applicable to MYs 2021-2025. Separately, NHTSA contendscontended that EPCA preempts California'California’s standards because the statute preempts state laws related to federal fuel economy standards.

66 EPA has declared that the MTE determination “is not a final agency action,” explaining that “a determination that the standards are not appropriate would lead to the initiation of a rulemaking to adopt new standards, and it is the conclusion of that rulemaking that would constitute a final agency action and be judicially reviewable as such.” EPA, “Mid-Term Evaluation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions Standards for Model Year 2022-2025 Light-Duty Vehicles: Notice; Withdrawal,” 83 Federal Register 16078, April 13, 2018. However, several states and stakeholders have filed petitions in the D.C. Circuit seeking judicial review of the revised MTE determination. See, e.g., Petition for Review, California v. EPA, No. 18-1114 (D.C. Cir. May 1, 2018); Petition for Review, Nat’l Coalition for Advanced Transp. v. EPA, No. 18-1118 (D.C. Cir. May 3, 2018); Petition for Review, Center for Biological Diversity v. EPA, No. 18-1139 (D.C. Cir. May 15, 2018).

67 EPA and NHTSA, “The Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient (SAFE) Vehicles Rule for Model Years 2021-2026 Passenger Cars and Light Trucks; Proposed Rule,” 83 Federal Register 42986, August 24, 2018 [hereinafter SAFE Rule Proposal].

Congressional Research Service

15

link to page 9 link to page 31 link to page 31 Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards: Frequently Asked Questions

Table 2standards. NHTSA argues that state laws regulating or prohibiting tailpipe CO2 emissions are related to fuel economy and can therefore be preempted regardless of California's CAA preemption waiver.

Observers have had difficulty comparing the costs and benefits reported under the proposed SAFE Vehicles Rule to those reported under the existing standards because each set of standards employs different compliance timelines, modeling, inputs, and underlying assumptions. For example, the primary focus of the analysis changed (i.e., from GHG emission impacts under the existing standards to fuel use, vehicle miles traveled, and highway accidents under the proposal), and the primary computer model and the modeling agency have changed (i.e., from the ALPHA and OMEGA models at EPA to the VOLPE model at NHTSA).70 Further, certain modeling assumptions have been amended (e.g., the social cost of carbon, new technology costs) and others have been added (e.g., a dynamic stock model to estimate the effects of new vehicle sales and existing vehicle scrappage). These changes and their impacts may likely shape the debate during the proposal's comment period and beyond.

|

Alternative |

Change in Stringency |

Air Conditioning and Other Off-Cycle Adjustments |

Retention of Provisions for Other GHGs |

|